ABSTRACT

During the nineteenth century, chemists became increasingly engaged in the conservation treatment of polychrome surfaces. While collaborations between chemists and museum workers in charge of easel painting collections were mostly oriented towards the improvement of conservation practices, the involvement of chemists in the nascent field of archaeology was oriented towards material characterization, such as pigment analysis of polychrome surfaces. Since this type of analysis is destructive and damages the artwork, it could, therefore, be assumed that chemists were in these cases less concerned with the conservation of objects with an archaeological and historical provenance. On the contrary, my new reading of nineteenth-century English primary sources reporting pigment analysis shows that chemists also had ethical concerns about the physical integrity of archaeological objects and their conservation. This is apparent in the process in which paint samples were taken from the artworks for their subsequent analysis.

Introduction

During the nineteenth century, chemists became increasingly engaged in the conservation treatment of polychrome surfaces. The collaborations between chemists and museum workers in charge of easel painting collections were mostly oriented towards the improvement of conservation practices, such as surface cleaning or further treatments aiming to reduce the deterioration of such artworks (Simon Citation2017). So-called Fine Art painting was considered to be ‘an essential feature of national prestige and was promoted accordingly’ (Nadolny Citation2012, 337), and England was a representative example of this. However, pigment analysis of easel paintings was not common practice. It was not until the twentieth century that publications about samples taken from such paintings can be found (Boothroyd Brooks Citation1999, 240). In the nineteenth century, chemists were also involved in the nascent field of archaeology. They were consulted for material characterizations of objects made of metal, ceramics, and glass, among other materials. Some of these samples were removed from wall paintings and artefacts with polychrome surfaces in order to identify past pigments and binding media. In these cases, it appears that chemists were less concerned with the preservation of such objects, since the procedures used relied on destructive methods. However, a new interpretation of primary sources in which pigment analyses are reported shows that chemists had ethical concerns about the physical integrity of archaeological objects and their preservation. Such concerns are demonstrated in the description of the processes used when paint samples were taken from the artworks for pigment analysis. These concerns were not only present among chemists, but were shared by antiquarians and connoisseurs. The present paper focuses on nineteenth-century England, as in this period the country held a leading position in the field of restoration practice (Simon Citation2017).

Chemists' concerns in the conservation of archaeological objects and wall paintings

Analysis of primary sources published in England during the nineteenth century reporting pigment analysis shows that chemists held a general ethical concern for the physical integrity and conservation of objects and wall paintings from an archaeological context.Footnote1 Two examples will be discussed here.

The first case study is a letter written by John Haslam (1764–1844). Haslam was an apothecary who had taken medical classes and worked as a doctor and private physician (Rees-Jones Citation1990, 93–95). He carried out analyses on samples extracted from Westminster Palace, London. In 1800, St. Stephen's Chapel, located in this palace, was renovated in order to provide more space for the new Irish Members of Parliament who were included after the union of Great Britain and Ireland. During the renovation, the wooden panels from the interior walls of the chapel were removed, and paintings – dating from the fourteenth century – were found underneath. Although most of this decoration was lost, John Thomas Smith (1766–1833), an English engraver and historian who was writing a catalogue about the Westminster buildings at the time of the St. Stephen's Chapel renovations (Smith Citation1807), took samples from the wall paintings and had them chemically analyzed by Haslam. The analysis of pigments and binding medium was performed around 1802 and Haslam sent a letter to Smith reporting his findings (Haslam Citation1802).

In his letter, Haslam not only reports the preservation of the pigments he analyzed, but he also shows a genuine concern about the physical condition of the wall paintings in St. Stephen's Chapel. Although for some colors Haslam only identifies the pigment, for other colors the chemist also mentions the condition in which they were found, whether they were well preserved, or showed signs of deterioration:

… red lead, which had wonderfully retained its lustre; white lead, but little altered; and a green, which is a preparation of copper, (in all probability verdigrise). This latter colour, however, had in some parts assumed a blueish appearance, and seems not to have kept so well as the rest. (Haslam Citation1802, 223)

… there can be no doubt that every method was employed to preserve these paintings, which must have been regarded as the perfection of the art at that period. It is to be lamented, that at the commencement of the nineteenth century, the coarse hand of the labourer should have violated this monument of regal splendour … (Haslam Citation1802, 225)

Admittedly, some sources show an exclusive interest in pigment and binding medium characterization by the chemists who performed the analyses (Davy Citation1817; Ure Citation1837; Faraday Citation1837a, Citation1837b; Rokewode Citation1885). However, a lack of interest in the preservation of antiquities cannot be concluded only by statements – or rather a lack of them – in these written reports, since the format in which the information was delivered also has to be considered. The fact that these texts are mostly letters from the chemists addressed to the antiquarians who requested the analysis, has an influence on the type of information included and the level of detail conveyed when reporting the analysis. Most of these chemists showed an interest in the conservation of archaeological findings, although not expressed in the pigment analysis reports, as discussed in the following section ().

Table 1. Sources presenting pigment analysis in nineteenth-century England.

How can the removal of samples affect the artwork?

A concern for the physical preservation of artworks by antiquarians, connoisseurs, and chemists is apparent in the process of taking the samples used for the chemical analysis of pigments. As sampling irrevocably changes the object's material condition it creates a tension between the wish to cause minimum damage to the artwork while obtaining the maximum amount of information from samples. Studying sources with regard to the size of the samples taken, their points of removal from the artwork, and the quantity of material removed can help to understand to what extent antiquarians, chemists, or archaeologists were concerned about the conservation of artworks.

In most of the nineteenth-century English sources reporting chemical analysis of pigments, it was not the chemists who performed the sampling, but the antiquarians or archaeologists, as they were usually present at the archaeological sites or in charge of the expeditions (Haslam Citation1802; Smithson Citation1824; Wilkinson Citation1837; Faraday Citation1837b). Later, they would bring the samples to chemists and ask them to carry out pigment analysis on their behalf. While chemists often did not do the sampling themselves, some reports about scientific analyses of the samples they had received reveal shared ethical concerns. An example is the work performed by the chemist Michael Faraday (1791–1867) and the members of the committee in charge of the examination of the Elgin Marbles.

Faraday collaborated extensively with professionals from the art field. He was not only involved in easel painting restoration treatments (he performed experiments on the protection and deterioration of paintings (Brommelle Citation1956, 184–85), but he also provided advice for the preservation of archaeological objects. The Elgin Marbles – removed from Athens – arrived at the British Museum in 1817, and were moved to new galleries in 1832 (). The controversies about their status as artworks and their restoration treatments arose even before the marbles arrived at the museum and continued during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries (Jenkins Citation2001, 1–6). Between 1836 and 1837, a select committee in charge of the examination of the marbles displayed at the museum, worked on these objects. A report on its findings was read by committee member William Richard Hamilton (1777–1859) at the closing ordinary meeting of the session in 1837, and published in 1842 in Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects of London (Hamilton Citation1842). As a key member of the committee, Faraday seems to have been the main referent when the committee was examining the condition of the objects to find possible paint residues on their surface: ‘Dr. Farraday [sic] was of opinion that this circumstance was of itself sufficient to have removed every vestige of color, which might have existed originally on the surface of the marble.’ (Hamilton Citation1842, 104)

Figure 1. Idealized view of the Temporary Elgin Room at the Museum in 1819, with portraits of staff, a trustee and visitors, oil on canvas, 1819, by Archibald Archer. Photo credit: The Trustees of the British Museum.

Faraday was also asked to perform pigment analysis of samples extracted from the marbles (). The publication quotes two brief letters written by Faraday in 1837, in which he reports the results of his chemical analysis performed on the paint samples sent to him. The first one is addressed to one of the members of the committee, the architect Thomas L. Donaldson (1795–1885), from whom he received paint samples extracted from the Propylea (Acropolis in Athens) and the Theseum (Temple of Hephaestus in Athens). The second letter is addressed to committee member William Richard Hamilton (1777–1859), who had also sent samples to Faraday – extracted from the statues of the Fates – with the aim to identify possible pigments.

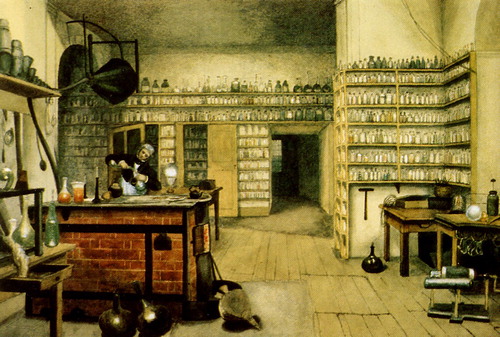

Figure 2. Michael Faraday in his laboratory at the Royal Institution, c.1850, by Harriet Jane Moore (1801–1884). Photo credit: Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons.

The way Faraday refers to the removed samples in his second letter provides information about their size. When reporting the results of the second group of samples, Faraday calls them particles. This may give the idea that he had pigment particles in a powder form. However, the chemist adds that the particles ‘seem to have come from a prepared surface’ (Faraday Citation1837b, 106) and he applies an acid to remove the adhering matter and obtain a cleaner sample. Furthermore, Hamilton states that the samples were ‘peeled off’ from the surface (Hamilton Citation1842, 106), suggesting that these were taken in the form of a film. Therefore, it is most likely that the samples were pieces – not powder – but their size was small enough to be called particles; so possibly, the person who removed them tried to minimize the damage to the artwork.

It is still difficult to determine how small these samples were, as to date no samples have been found that survive from this period. Although not from England, certain French and German publications about pigment analysis may provide a reference to compare with Faraday's samples, as they are the few known examples that describe the size of the sample with an objective measuring method. Nadolny (Citation2003, 41) discusses a selection of textual sources from the nineteenth century in which samples were weighed, the smallest one being 0.27 milligrams and the biggest around 4 grams. The latter were reported in German articles about Egyptian and Roman archaeological sites, but in this case the sample did not contain pigment, but plaster instead. On the contrary, the 0.27 mg sample is mentioned in a text written by the French archaeologist Benjamin Fillon (1819–1881), in which the findings relating to a villa and tomb in Saint-Médard-Des-Prés are described (Fillon Citation1849). Fillon explains that he provided samples to the chemist Michel Eugène Chevreul (1786–1889) for materials characterization and quotes the report written by the chemist. In this report, Chevreul mentions the weight of the samples as being equivalent to ± 0.27 mg.Footnote2 It is important to consider that this is not the weight – and hence the size – of the original sample taken from the archaeological site, as Chevreul describes how he mechanically removed these particles from a larger sample:

With great care, but always by mechanical methods, I managed to isolate from this material the yellow grains (…). Although I had only a quantity that did not exceed 0gr005, I could confirm that they were formed of sulfur and arsenic; so they consisted of orpiment.Footnote3 (Fillon Citation1849, 50)

It is also reported that the pieces were taken using a penknife, which is a sharp precision tool that would allow the removal of fairly small samples.

The methods and places of removal are also mentioned in Hamilton's report, which states that pieces from the surface were taken ‘from the back of one of the figures’ (Hamilton Citation1842, 106). While the report offers no explanation on why this was carried out from the back side, such an action suggests that the person who performed it was trying to avoid damage at the front of the object, which is the main viewing side for Greek sculpture.

Although none of these decisions were made by Faraday himself, he was a member of the committee that examined the marbles. As discussed earlier, he was a main referent when the committee was examining the condition of the objects to find possible paint residues on their surface. Thus, he must have agreed to a certain extent with the methods used by the other committee members.

Another illustrative example is the report written in 1815 by the chemist Humphry Davy (1778–1829) (Davy Citation1815). Importantly, this is the only English source from the nineteenth century that has been found to the present date in which the chemist could decide on the sampling process; and it shows a general concern for artworks in the field of archaeology.

As part of a Grand Tour around Europe, Davy obtained paint samples from archaeological sites in Rome and Pompeii and performed analyses on them in 1814, while he was still in Rome (Rees-Jones Citation1990, 97). Davy explained the results of his findings in an article published by the Royal Society (Davy Citation1815). In another article published two years later, the chemist reported the results of analysis carried out on stucco samples from the wall paintings of a Roman house in Sussex (Davy Citation1817).

Both publications were authored by Davy himself and not quoted in someone else's text, as is the case in most of the other sources. While his later publication only reports the results of the analysis – as it is a letter conveying the results to the person who requested them – his first publication is an article driven by his own interest. In this text, he highlights how he has been able to take the samples himself: ‘I have been enabled to select, with my own hands, specimens of the different pigments’ (Davy Citation1815, 100). Furthermore, he proudly describes the sampling process: how he removed extremely small pieces of paint from places where the loss remained unnoticed:

When the preservation of a work of art was concerned, I made my researches upon mere atoms of the colour, taken from a place where the loss was imperceptible: and without having injured any of the precious remains of antiquity … . (Davy Citation1815, 100)

Conclusions

In the nineteenth century, chemists became increasingly engaged in the conservation treatment of polychrome surfaces, and also became involved in the archaeological field. According to nineteenth-century English publications, chemical analyses of pigments were carried out on samples taken from objects and wall paintings from archaeological or historical contexts.

This article documents the ethical concerns and interests of nineteenth–century chemists involved in the field of archaeology. While it could be assumed that the main interest of chemists engaged in the analysis of antiquities was the characterization of materials and not the conservation of objects, nineteenth-century English primary sources reporting on the chemical analysis of pigments show that there was an ethical concern for the physical preservation of artworks found in archaeological contexts. Whereas the main goal of the reports on chemical analysis was the identification of pigments, chemists also showed an interest in the conservation of the artworks from which the samples were taken. The process of taking paint samples used for the chemical examination of pigments and binding media also indicates that chemists, antiquarians, and connoisseurs held an attitude of respect towards the physical integrity of archaeological objects and wall paintings.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See , for a general view of the English publications extracted from Nadolny's article (Citation2003) that will be analyzed in the present study.

2 The weight mentioned by Chevreul is ‘0gr005’ (Fillon Citation1849, 50). Nadolny recalculates from ‘gran’ to milligrams as 1 gran = 53.1148 mg to obtain the result of the sample weight as 0.27 mg (Nadolny Citation2003, 41).

3 Translation carried out by the author of this paper. Original text: ‘Avec beaucoup de soin, mais toujours par des procédés mécaniques, je suis parvenu à isoler de cette matière les grains jaunes (13.3°). Quoique je n'en aie eu qu'une quantité qui n'excédait pas 0gr005, j'ai parfaitement constaté qu'ils étaient formés de soufre et d'arsenic; ils consistaient donc en orpiment.’

References

- Boothroyd Brooks, H. 1999. “Practical Developments in English Easel-Painting Conservation, c.1824–1968, From Written Sources.” PhD thesis, Courtauld Institute of Art, University of London, London.

- Brommelle, N. 1956. “Material for a History of Conservation. The 1850 and 1853 Reports on the National Gallery.” Studies in Conservation 2: 176–188.

- Capon, W. 1835. “Plate XLVII. Notes and Remarks, by the Late Mr. William Capon, to Accompany his Plan of the Ancient Palace of Westminster [Read 23d December, 1824].” Vetusta Monumenta 5: 1–7.

- Davy, H. 1815. “Some Experiments and Observations on the Colours Used in Painting by the Ancients.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London 105: 97–124. doi: 10.1098/rstl.1815.0009

- Davy, H. 1817. “Observations upon the Composition of the Colours Found on the Walls of the Roman House Discovered at Bignor in Sussex [15 June 1815].” Archaeologia: or Miscellaneous Tracts Relating to Antiquity 18: 222–222. doi: 10.1017/S0261340900026163

- Faraday, M. 1837a. “Letter to T.L. Donaldson, 21st April 1837, Quoted in the Report of the Committee Appointed to Examine the Elgin Marbles.” In Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects of London. 1842. Vol. I, Part II: 106–107. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Faraday, M. 1837b. “Letter to W.R. Hamilton, 8th June 1837, Quoted in the Report of the Committee Appointed to Examine the Elgin Marbles.” In Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects of London. 1842. Vol. I, Part II: 106–107. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Fillon, B. 1849. Description de la villa et du tombeau d’une femme artiste gallo-romaine, découverts à Saint-Médard-des-Prés (Vendée). Fontenay: Robuchon. http://data.bnf.fr/13197296/benjamin_fillon/#rdt70-13197296.

- Hamilton, W. R. 1842. “Report of the Committee Appointed to Examine the Elgin Marbles.” In Transactions of the Royal Institute of British Architects of London. Vol. I Part II: 102–108. London: Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans.

- Haslam, J. 1802. “Letter to J.T. Smith.” In Antiquities of Westminster, 223–226. London. https://archive.org/stream/antiquitiesofwes00smit.

- Jenkins, I. 2001. Cleaning and Controversy: The Parthenon Sculptures 1811–1939. The British Museum Occasional Paper, Number 146. London: The British Museum. https://www.britishmuseum.org/pdf/4.4.1.2%20The%20Parthenon%20Sculptures.pdf.

- Nadolny, Jilleen. 2003. “The First Century of Published Scientific Analyses of the Materials of Historical Painting and Polychromy, Circa 1780–1880.” Reviews in Conservation 4: 39–51.

- Nadolny, Jilleen. 2012. “A History of Early Scientific Examination and Analysis of Painting Materials ca.1780 to the mid-Twentieth Century.” In The Conservation of Easel Paintings, 336–340. London: Routledge.

- Rees-Jones, S. G. 1990. “Early Experiments in Pigment Analysis.” Studies in Conservation 35: 93–101.

- Rokewode, J. G. 1885. “Plates XXVI-XXXIX. A Memoir on the Painted Chamber in the Palace at Westminster, Addressed to the Earl of Aberdeen, President, by John Gage Rokewode, Esq. F.R.S. Director, Chiefly in Illustration of Mr. Charles Stothard's Series of Drawings from Paintings upon the Walls of the Chamber [Read 12th May 1842].” Vetusta Munumenta 6: 1–37.

- Simon, J. 2017. “Restoration Practice in Museums and Galleries in Britain in the Nineteenth Century.” In A Changing art: Nineteenth-Century Painting Practice and Conservation, edited by N. Costaras, K. Lowry, H. Glanville, P. Balch, V. Sutcliffe, and P. Saltmarsh, 5–13. London: Archetype Publications.

- Smith, J. T. 1807. Antiquities of Westminster. London. https://archive.org/stream/antiquitiesofwes00smit.

- Smithson, J. 1824. “An Examination of Some Egyptian Colours.” The Annals of Philosophy 7 New Series: 115–116.

- Ure, A. 1837. “Analytical Report.” In Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. vol. 3, 301–303. London: John Murray. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t2×351h56.

- Wilkinson, J. G. 1837. Manners and Customs of the Ancient Egyptians. Vol. 3. London: John Murray. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/gri.ark:/13960/t2×351h56.