ABSTRACT

After May 2, 2022, heritage conservation briefly became a hot topic in the world of celebrity gossip. That evening, Kim Kardashian, a reality TV star and entrepreneur, wore a 60-year-old dress that had belonged to Marilyn Monroe to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual Costume Institute Gala. In wearing Monroe’s dress, Kardashian sought to channel the glamor and celebrity of the mid-century star. She also summoned the ire of museum professionals, who considered her choice to wear a fragile historical garment a flagrant violation of conservation ethics. Yet increasingly, the discipline of conservation has come to recognize that an object’s ‘integrity’ does not rest solely in its physical materials – and the emerging discourse of performance conservation, informed by research into the conservation of contemporary art as well as intangible cultural heritage, emphasizes the active lives of what I call ‘performative objects’ over their physical form and static appearance. Here, I posit that Kardashian’s wearing of Monroe’s dress may be understood as a form of conservation – perhaps not of the dress itself, but of the performance of which that dress was an integral part, and without which, I argue, the dress has little significance. To make this argument, I will also draw on innovative approaches to the conservation of Indigenous heritage that recognize the preservation value of reanimating objects from the past. Establishing Monroe’s dress as a ‘performative object,’ an item inextricably linked to the body in motion, I endeavor to show how performance itself preserves the past.

Introduction

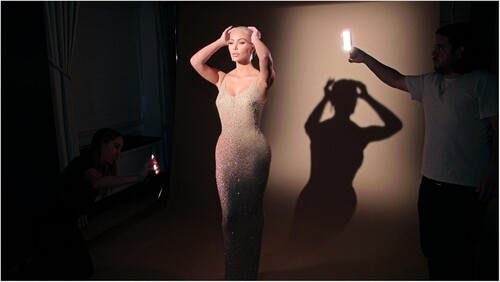

After May 2, 2022, heritage conservation briefly became a hot topic in the world of celebrity gossip. That evening, Kim Kardashian, a reality TV star and entrepreneur, wore a 60-year-old dress that had belonged to Marilyn Monroe to the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s annual Costume Institute Gala (). The Met Gala is known as the most spectacular event in fashion’s calendar, and its red carpet reliably delivers a parade of provocative looks. Yet while the big-name personalities who attend the gala often seek to impress or shock with cutting-edge designs, that year, the oldest garment got the most attention. In wearing Monroe’s dress, Kardashian sought to channel the glamor and celebrity of the mid-century star. Yet she also summoned the ire of museum professionals and fashion historians, who considered her choice to wear a fragile historical garment a flagrant violation of conservation ethics. Within hours of the gala, publications like People Magazine and the New York Post featured damning quotations from conservators and historians, and the costume committee of the International Council of Museums (ICOM) issued a stern objection: ‘As museum professionals, we strongly recommend all museums to avoid lending historic garments to be worn,’ as ‘they must be kept preserved for future generations’ (Holmes Citation2022; Ibrahim Citation2022; ICOM Costume Citation2022; Patterson and Farin Citation2022).

Figure 1. Kim Kardashian poses in Marilyn Monroe’s ‘Happy Birthday’ dress prior to the 2022 Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute Gala. Image courtesy of Hulu.

There can be no question that wearing historical garments physically damages them.Footnote1 This is why many conservators responded with horror to Kardashian wearing Monroe’s dress, and why most museums prohibit clothing in their collections to be worn by anyone. Conservators, charged with maintaining the integrity of the objects under their care, are directed to strictly limit the handling of textiles, and to protect them from physical stress, bright lights, and the oils and soils that rub off skin. Kardashian exposed Monroe’s dress to all these dangers. Yet increasingly, the discipline of conservation acknowledges that an object’s ‘integrity’ does not rest solely in its physical materials – and the emerging discourse of performance conservation, informed by research into the conservation of contemporary art as well as intangible cultural heritage, emphasizes the active lives of what I call ‘performative objects’ over their physical form and static appearance. At the same time, historical and critical studies of dress recognize that ‘fashion’ does not refer to inert garments, but rather demands the embodied performance of those garments – whether on a catwalk, stage, red carpet, or city street (Kollnitz and Pecorari Citation2022).Footnote2

In what follows, I posit that Kardashian’s wearing of Monroe’s dress may be understood as a form of conservation – perhaps not of the dress as a material garment, but of its performativity – and without which, I argue, the dress has relatively little significance. After introducing Monroe’s so-called ‘Happy Birthday’ dress and the objections to Kardashian’s having worn it, I argue that all garments, but this one especially, are ‘performative objects,’ both necessary for and inextricable from live, embodied performance. This means that, in a sense, a garment complicates and confuses subject- and objecthood: Once on a body, a dress may be performed by that body, but it can also be said to perform in tandem with that body, exercising its own material agency (for example, by sparkling under a spotlight, representing a certain cultural identity, or altering the body’s appearance or movement). In conserving a dress, then, it is necessary to consider that dress’s relationship to embodiment and performance, understanding that the garment may play various roles in that relationship.

It may be difficult for some readers to accept that the value of ‘reperforming’ this dress could outweigh the damage to its material existence. But more than one dress is at stake. In insisting that Kardashian’s performance of Monroe’s dress has conservation value, I mean to undermine the still-common assumption that material values should always be paramount in conservation, and to argue that garments in particular are rich in body-based and immaterial aspects that are essential to their meaning yet often overlooked – even destroyed – in museum contexts. Accordingly, if surprisingly, Kardashian’s Met Gala appearance provides an ideal case for asserting and testing the claims of performance conservation, a nascent subdiscipline within the colorful and complex field of contemporary art conservation. To make this argument, I will also draw on dress history, performance studies, and innovative approaches to the conservation of Indigenous heritage that recognize the preservation value of reanimating objects from the past. Establishing Monroe’s dress as a ‘performative object,’ an item inextricably linked to the body in motion, I endeavor to show how performance itself is capable of preserving the past.

The ‘Happy Birthday’ dress – object and event

In 2022, the Costume Institute’s gala celebrated the opening of the exhibition In America: An Anthology of Fashion. Kardashian, a faithful attendee since 2013, set her sights on the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress as the ultimate reflection of that theme: ‘What’s the most American thing you can think of?’ she asked Vogue, providing the answer: ‘Marilyn Monroe’ (Nnadi Citation2022). The dress at the center of this scandal has a unique materiality and a sensational history, and understanding its performativity requires us to consider these in detail. The dress was made for Monroe by Jean Louis Berthault (called simply ‘Jean Louis’), a French-born Hollywood designer who provided costumes for several of Monroe’s films. It is a skin-tight, floor-length sheath suspended from widely spaced shoulder straps that taper up from a neckline shaped in a gently rounded V that exposes a whisper of cleavage (). This form repeats at the low-cut back, where the straps descend almost, but not quite, to the inward indentations of the waist. There, an almost invisible zipper and a series of metal hooks allow the wearer to step into the dress, while an unusually high slit at the back permits her to perambulate – at least from the knee down. (Accounts vary as to whether the zipper was original to the dress and added later, as it has also been claimed that Monroe was sewn into the dress.)

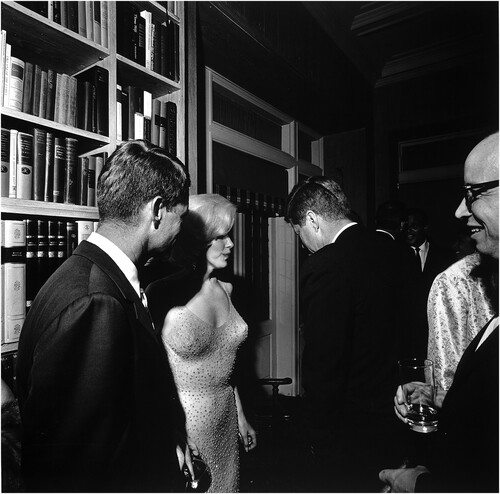

Figure 2. Monroe with Robert F. Kennedy and John F. Kennedy after the gala at Madison Square Garden. Photo by Cecil W. Stoughton, from Wikimedia Commons.

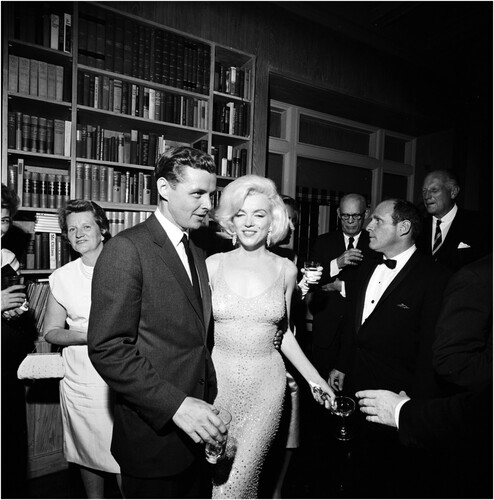

The pale gold material is called soufflé, a sheer, gossamer-thin blend of silk and synthetic fibers by the French brand Bianchini that was ultimately banned in the United States due to its flammability (Agins Citation2005; ‘Irene Draped Black Evening Gown Citation1950s’ Citation2001; ‘What Is Souffle Silk Fabric?’ Citation2023). Soufflé would come to be favored by Bob Mackie, then an assistant to Jean Louis, who drew the initial sketch on which Monroe’s dress was based. The simplicity of the dress’s form serves as a blank canvas for its decoration: the entire gown is covered in silver-white glass rhinestones of multiple sizes, which appear closely scattered across its surface like raindrops or bubbles in a glass of the champagne that its color also conjures. They are sewn to the dress with beige thread through a central hole in each crystal. The faceted crystals are more closely clustered on the narrow column of the skirt towards the dress’s hem, emphasizing the voluminous expanses of the wearer’s body above, which seem almost to stretch out the material as they fill it.

In the preceding lines, I have carefully described the dress itself, its material and form. Yet this description tells us next to nothing of its significance. The dress is dazzling in its array of rhinestones, but it is less spectacular than many other gowns designed by either Jean Louis or, later on, by Mackie, who created some of the most outrageous looks worn by Cher in the 1970s and 80s. Its significance lies not in its design, appearance, or materials as such, but rather in the way it appeared – the way it performed – when worn on stage by Monroe. As I will argue, it is a skin made both to cover and reveal the body of a star during a crucial moment of public exposure; it is as much a performance as an object. What, then, are we conserving, when we conserve only the garment’s materiality, and not its performativity?

Marilyn Monroe herself commissioned and wore this dress at a pivotal moment in her career and life. In 1962, she was invited to appear in a star-studded fundraiser for the Democratic Party at Madison Square Garden on May 19 and sing ‘Happy Birthday’ to President John F. Kennedy, whose 45th birthday was 10 days later. Though she was to play a relatively minor role, Monroe understood this as a significant opportunity to appear before an enormous crowd – more than 15,000 people attended the event – and to assert her independence from Twentieth Century Fox, which used a restrictive and exploitive contract to keep Monroe on a short leash, and with which she frequently feuded. Monroe was at that time filming the ultimately unfinished Something’s Got to Give, and Fox forbid her from traveling to New York for the event. That she did so anyway was therefore both a deliberate act of self-assertion and a sign of how much importance Monroe accorded the event. She understood it not as a mere public appearance but as a ‘command performance,’ as Fred Lawrence Guiles, Monroe’s first serious biographer, later stated (Rollyson Citation2014, 226).

For this performance, Monroe had requested a special gown from Jean Louis, who was well-known for his lavish designs for many film stars, including Lucille Ball, Joan Crawford, Kim Novak, Doris Day, and Ginger Rogers (Nickens and Zeno Citation2012, 68). According to Mackie, Monroe ‘wanted something that would be more outrageous and sexy than anything she’d ever worn in a film’ (Ricchio Citation2022).Footnote3 Monroe’s biographers report that the star asked Jean Louis for a ‘truly historic dress’ (Vitacco-Robles Citation2014, 427), one ‘that only Marilyn Monroe could wear’ (Taraborrelli Citation2009, 433). As the designer later recalled, ‘Marilyn had a totally charming way of boldly displaying her body and remaining elegant at the same time.’ To match this beguiling combination, he created ‘an apparently nude dress – the nudest dress – relieved only by sequins and beading’ (Taraborrelli Citation2009, 433).Footnote4 Jean Louis had previously created gowns for Marlene Dietrich that combined sheer, figure-hugging fabric with extravagant beadwork. Once struck by stage or studio lights, the fabric melts away; Dietrich seems to be wearing nothing but glittering jewels. Louis achieved this effect by dying the sheer, delicate material to precisely match Dietrich’s skin tone, a technique he repeated here for Monroe. The unlined dress was too tight and transparent for undergarments, which Monroe famously scorned; this certainly augmented its capacity to titillate. Mackie called this effect ‘the illusion of being naked,’ adding that viewers believe ‘you can see something but you really can’t’ (Julien’s Auctions Citation2016).

In fact, great pains were taken to maintain the illusion of glittering nudity while actually preserving the star’s modesty. Special panels were sewn into certain sections; according to one source, twenty layers of gauzy soufflé covered Monroe’s breasts (Vitacco-Robles Citation2014, 428). Viewers were to feel breathtakingly close to Monroe’s body, an impression heightened not only by the stage lighting for which the garment was expressly designed but also by Monroe’s performance in and of the dress (). As an actor, Monroe was, of course, a performer. But this was a rare live performance by and of Monroe herself, captured on film but primarily intended for the thousands of people who occupied the same space with her that night.

Figure 3. Under the camera’s flash, the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress blends perfectly with Monroe’s skin tone. Photo by Cecil W. Stoughton, from Wikimedia Commons.

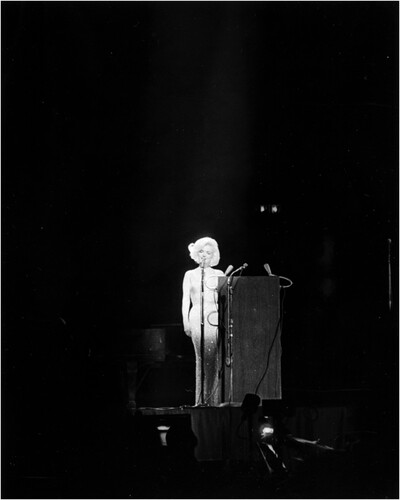

In teasing acknowledgement of her reputation for arriving late to rehearsals, Monroe was given several gag introductions throughout the evening: A spotlight shone on an empty corner of the stage, leaving the audience to wonder if she would truly be there at all. As a result, the crowd went wild when, towards the end of the evening, host Peter Lawford finally introduced the ‘late’ Marilyn Monroe – a chilling quip in retrospect, given Monroe’s impending death – and the spotlight illuminated a glowing figure with a swoop of shining hair (). In the fuzzy, high-contrast film footage that survives, Monroe comes mincing forward, her footsteps hindered by the tight-fitting dress.Footnote5 She clutches a short but voluminous white fur coat around her body. When she reaches the podium, Lawson pulls the coat from her shoulders, revealing a form seemingly clad in nothing but glitter. The crowd gasps – and then responds with such wild enthusiasm that Monroe is obliged to wait nearly 30 seconds before she speaks.

Figure 4. Marilyn Monroe sings ‘Happy Birthday’ to President John F. Kennedy. Photo by Cecil W. Stoughton, from Wikimedia Commons.

The drama and mischief of this revelation were heightened by the fact that the gala’s organizer, Jean Dalrymple, had issued Monroe’s invitation with the qualification that she agree to dress modestly (Nickens and Zeno Citation2012, 77). Monroe claimed that she planned to wear a black, high-necked dress by Norman Norell, who was known for the elegant simplicity of his designs (Vitacco-Robles Citation2014, 427). She had made the same promise to the event’s producer, Richard Adler, who grew nervous after hearing Monroe practice her outrageously sexy version of ‘Happy Birthday.’ Whether or not Monroe intentionally misled Dalrymple and Adler, or simply changed her mind, their shock cannot have been less than that expressed by the hollering and murmuring crowd.

Waiting for the hubbub to subside, Monroe shields her eyes from the stage lights with her hands, seeking to look out into the crowd. Finally, her fingers gently wrapped around the microphone stand, she begins to sing: ‘Happy birthday to you … ’ She smiles, seems to relax; her arms and shoulders release their tension. Towards the end, Monroe seems to gain confidence. She spreads her arms and, just before the band kicks in for the second round, shouts ‘Everybody!’ With wide, joyful gestures, she pretends to conduct the musicians and guests. An enormous cake is brought out, and her performance is concluded. All the while, the dress sparkles unceasingly. On film, the border between its fabric and Monroe’s skin is invisible. She appears as a ghostly white figure made of shimmering starbursts.

Conserving garments

Because of Monroe’s death just months after this event – and Kennedy’s the following year – the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress has come to crystallize this moment in American history and pop culture as well as the peak, equally triumphant and tragic, of Monroe’s stardom. As a material trace of a life that flickered in the ghostly glow of film projectors, the dress endures though Monroe did not. Yet while it survives, the dress is as fragile as Monroe is often supposed to have been. In the words of two conservators, textiles are ‘some of the most vulnerable objects in our cultural heritage’ (Lennard and Ewer Citation2010, ix).

‘All of us have a fantasy to wear something from a museum,’ commented dress historian Karen Ben-Horin about the scandal caused by Kardashian’s Met Gala appearance. ‘That’s what makes fashion exhibitions so successful. But you can’t’ (Holmes Citation2022). Ben-Horin’s position aligns with those of most commentators quoted in the press, and also reflects what journalists apparently expected to hear: it was wrong for Kardashian to wear the dress. As conservator Philip Sykas detailed in 1987, even when garments are worn with the greatest care – and even when the naked eye is unable to detect any subsequent damage – aging fabric is still subject to microscopic tears and accrues debris from human skin, which is nearly impossible to remove (Sykas Citation1987). Kardashian was permitted to wear the dress by its owner, the Orlando, Florida location of Ripley’s Believe it or Not! (the exclamation mark is part of the trademarked name), an international chain of museums or ‘odditoriums.’ Ripley’s is not accredited by the American Alliance of Museums, which means that it is not bound to observe its guidelines; an accredited institution might not have approved Kardashian’s request.Footnote6 Usually, conserving a garment means treating it like any other precious museum object: protecting it from physical, chemical, and environmental stressors in a bid to make its fragile materials last as long as possible.

After Kardashian wore the dress to the Met Gala, Sarah Scaturro, once a conservator at the Costume Institute and now chief conservator at the Cleveland Museum of Art, expressed her frustration to the Los Angeles Times, referring to a 1987 resolution of the Costume Society of America that encouraged ‘the prohibition of wearing objects intended for preservation’ (Costume Society of America Citation1987; Saad and Vankin Citation2022). While conservation within and beyond the subfield of textiles has evolved greatly since the 1980s, this prohibition is still supported by most museums and by other professional organizations such as ICOM (ICOM Costume Citation2022).

As Scaturro emphasizes, fashion conservators’ outcry against Kardashian’s wearing of Monroe’s dress must be understood in the context of the history of the discipline.Footnote7 Sykas and Scaturro both noted, decades apart, that stewards of dress collections often face pressure to lend their collections in just this way, and Kardashian’s stunt undermines their ability to resist such requests (Holmes Citation2022; Mida Citation2015, 44). Conservators, curators, and scholars of fashion and costume have long fought for their objects of study to be taken seriously. That the field has always been dominated by women, and fashion itself dismissed as female frivolity, has surely contributed to its marginalization, as pioneering dress historian Lou Taylor observed two decades ago (L. Taylor Citation2002, 1–2; Citation2004, 2). Even today, and even at the Met, other sorts of objects are often prioritized for care by museums. Accordingly, the application of professional conservation standards to items of dress has only in recent years become a matter of course, and thus represents hard-won recognition and respect for the field. To allow a garment of historical importance to be worn may threaten that success – and it is particularly ironic at a function intended to raise funds for the care of the Costume Institute’s collection.

Yet to focus exclusively on the preservation of fabric, seams, zippers, and buttons is to risk misunderstanding what fashion is and means. As Robyn Healy points out, ‘[F]ashion itself is an immaterial object’ – a cluster of things, gestures, ideas, people, (market)places, and more (Healy Citation2020, 325).Footnote8 Scaturro distinguishes ‘fashion-as-object’ and ‘fashion-as-system,’ emphasizing the contribution of values-based approaches to textile conservation (Scaturro Citation2017a). While garments serve as a synecdoche of fashion, they do not exhaust it. Therefore, conserving a garment is not the same thing as conserving fashion. Many aspects play a role here, but most significantly, clothing is designed to be worn by a body in movement – which is the very essence of performance.

Performative objects

Indeed, the care and study of fashion is intimately entwined with some of the problems that belong to the realm of performance conservation. With the increasing presence of performance art, both new and historical, in visual arts spaces, this is only just beginning to be recognized as a legitimate subfield of conservation. As art museums increasingly collect works of live performance (and not merely the documents and ‘relics’ that they leave behind), the question of what it means to conserve performance in a visual arts context grows increasingly urgent. Some conservators and scholars have begun to address this challenge, pioneering techniques for performance works to be maintained within museum collections and establishing theoretical frameworks for considering performance’s longevity (Borggreen and Gade Citation2013; Büscher and Cramer Citation2017; Giannachi and Westerman Citation2018; Hölling Citation2022; Hölling, Pelta Feldman, and Magnin Citation2023 (forthcoming); Laurenson and van Saaze Citation2014; Lawson, Finbow, and Marçal Citation2019; Rieß, Bohlmann, and Hausmann Citation2019; Casagrande Citation2017). The nascent field of performance conservation draws from innovative work in contemporary art conservation, notably the conservation of electronic or time-based media, as well as the discipline of performance studies. As pioneering scholars such as Richard Schechner and Victor Turner argued, performance itself is as old as human culture; dance, theater, rituals, games, and other forms of performance have been ‘conserved’ through traditional techniques of body-to-body transmission for centuries or even millennia. Performance conservation thus acknowledges the necessity of the body not only in creating performance but also in keeping it alive.

Among Kardashian’s critics was Bob Mackie, who called wearing Monroe’s dress a ‘big mistake.’ Mackie expressed the typical concerns about damage, but also added that the dress ‘was designed for’ Monroe: ‘Nobody else should be seen in that dress’ (Lenker Citation2022). Mackie’s view corresponds to the still-influential performance ontology defined by Peggy Phelan in the early 1990s, which insists on performance art as a vanishing, unrepeatable act: after Monroe’s death – perhaps, as soon as she finished singing ‘Happy Birthday’ and left the stage – the dress transformed back into a mere garment, an object, no longer part of the performance of fashion (Phelan Citation1993). Yet in the intervening decades, many scholars, critics, and performance artists have troubled the understanding of performance that underlies Mackie’s statement (Auslander Citation2008; Bedford Citation2012; Jones Citation1997; Lepecki Citation2010; Moten Citation2003; Schneider Citation2011; Taylor Citation2003). As Rebecca Schneider has insisted, ‘performance remains’ (Schneider Citation2001). The very structural and material realities of fashion support the multiplicity of performance: zippers and buttons tell us that garments are meant to be taken off and worn again, their performance repeated indefinitely by one or multiple wearers.

The recurring nature of performance is embedded in objects that are inherent to it, what I call ‘performative objects.’ A performative object, in my definition, is not merely any item that is used in performance, say as a costume or prop, but is rather an object that is fundamentally incomplete without that performance – and which, at the same time, is indispensable for the performance to occur in the first place. The performance – understood in this case as some form of movement, transformation, or activation – can be intrinsic in the object itself; by ‘activation’ I mean the opposite of dormancy (Lawson, Finbow, and Marçal Citation2021). Within art, kinetic sculpture such as that of Naum Gabo or Jean Tinguely fulfills the criterion of the performative object. Some objects or materials betoken performativity through their inherent volatility; one might also think of Allan Kaprow’s Fluids, a 1967 happening in which large structures made of ice were left to melt in the Los Angeles sun.

Conservator Miriam Clavir provides the example of a machine exhibited in a museum that, for its identity as a machine to remain intact, must be conserved in such a way that its workings remain operational, at least to a certain degree (Clavir Citation2002, 63). Most often, however, the performativity of the object is activated by a human being in performance, whether the performance is theatrical (e.g. a costume), musical (musical instrument), ritual (often involving sacred or symbolic objects, which may be displayed, worn, eaten, etc.), or something else entirely.

For Hanna Hölling, a ‘performative object’ in the context of post-conceptual art is akin to what is often called a performance ‘relic,’ that is, an object that has been used in a performance that is ‘valued for its unique status, rather than a repeatable or replaceable prop or leftover of little value’ (Hölling Citation2017, 46). Irene Müller refers to performance relics as materials ‘in which the traces of performative actions are stored and enclosed, and which are attributed with the function of transmitting aura and encapsulating emotions’ (Müller Citation2013, 26). For Hölling, what is performative about the relic is that, while its identity may be determined by the performance of which it was a part, it does not lose that identity after the performance is over. I see a performative object not as a relic signaling the performance’s pastness, but rather as a performer awaiting activation (regardless of whether or not it has previously been activated). Like Hölling, I emphasize that a relationship maintains between the object and the performance even in the absence of the latter.

The weighty term ‘performative’ has different meanings in different disciplines (Loxley Citation2007). I use it here in reference both to its general usage within performance studies, where it describes a wide range of relationships to deliberately enacted performance (such as in theater, rituals, games, etc.), and to the theoretical lineage that has accrued to J. L. Austin’s influential notion of ‘speech acts’ (Austin Citation1962; Butler Citation1988; Searle Citation1969).Footnote9 For Austin, an illocutionary act is one in which words are not ‘mere’ words, but actually constitute an action – they activate some real change in the world (as in sentences that begin with ‘I dare you’ or ‘I forgive you’). Since this is generally not the case in theater, the difference between performance and performativity is sometimes, if reductively, explained as the difference between reality (performativity) and fiction (performance).Footnote10 In speaking of performative objects, I do not mean only that the object is part of or adjacent to performance. Rather, I mean to argue that what is activated through performance – what is made real in the world, or in Austin’s phrasing, the perlocution – is the object itself. Only through performance does a performative object truly come into being. It is otherwise as effective, as enacted, as an unuttered word.

The ‘Happy Birthday’ dress is indelibly tied to Monroe’s ‘command performance,’ but most any garment is a performative object. As Lou Taylor has elucidated, clothes are explicitly designed to respond to ambient lighting conditions and to the movements of the bodies within them: ‘Fashion and fashion textile designers have built their reputations on the fusion of malleable textures and colors as their garments move on the wearer’ (L. Taylor Citation2002, 24). She cites the example of eighteenth century silk designers in Lyon who incorporated glittering yarns into one element of their brocade patterns, which would sparkle as the wearer moved through a ballroom lit by oil lamps. Jean Louis exaggerated this principle in the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress, anticipating that Monroe’s movements would set off cascades of sparkle as the stage lighting bathed her form. What this means is that conservation measures designed to preserve a garment’s fabric and form – namely, the absence of a moving body, or any kind of movement – may threaten its identity as a performative object. Performance cannot be excised from clothing without some damage done to its meaning, even when that damage takes the form of the most careful and respectful preservation.

Conserving performance

Many material things possess immaterial meanings, but the Western discipline of art conservation has traditionally focused on maintaining or restoring the appearance and physical integrity of the objects it cares for. This has frequently meant retiring from function objects, such as garments, that were originally intended to be used in some way. André Desvallées and François Mairesse define musealization as ‘the operation of trying to extract, physically or conceptually, something from its natural or cultural environment’ and transforming it into a ‘museum object.’ Separated from its environment of origin, ‘[a] museum object is no longer an object to be used or exchanged’ (Desvallées and Mairesse Citation2010, 50–51). Yet over the past few decades, conservators have increasingly come to question the validity of excising an object from its home context, and to recognize that objects encompass a variety of meanings that may require other, even contradictory types of intervention if they are also to be preserved. As Salvador Muñoz-Viñas points out, conservation often makes ‘one of all the possible meanings prevail, at the expense of the other possible ones’ (Muñoz-Viñas Citation2005, 170). Similarly, Jane Henderson posits the possibility of conceptual damage done in pursuit of material preservation (Henderson Citation2020, 203). In demanding that the dress be conserved as a static object and protected from human skin, approaches like ICOM’s deny the performative and body-dependent aspects of the dress that wearing it brings to the fore.

Conservation clashes occur when the impulse to preserve material integrity contradicts ‘conceptual integrity,’ which may demand that a museum object be used or activated in some way. In the case of a machine, for example, Miriam Clavir, a pioneer of conservation work on First Nations items in Canada, notes the importance of allowing for motion: ‘the conceptual integrity of the artifact is not complete when the object is static’ (Clavir Citation2002, 63). Henderson has questioned the very assumption that a conservator’s job is to maintain an object for as long as possible, and urges her colleagues to ‘ensur[e] concepts of loss include both tangible and intangible aspects’ (Henderson Citation2020, 211). As both Clavir and Henderson emphasize, a focus on material integrity may overshadow significant aspects of performative objects.

These developments within the discipline of conservation find their parallel in the related field of heritage studies. To the broad term ‘cultural heritage’ has been added the new sub-category of ‘intangible cultural heritage (ICH),’ which UNESCO formally adopted in 2003 (UNESCO Citation2020). It allows those who work to promote and protect cultural heritage to address the myriad forms of culture – music, dance, oral history, craftsmanship techniques, ritual, and much more – that relate to performance. William S. Logan has described ICH as ‘heritage that is embodied in people rather than in inanimate objects’ (Logan Citation2007, 33). Accordingly, ICH approaches prioritize the living transmission of culture within its origin communities, rather than the post-facto attempt by outsiders to preserve its products. Performative objects, such as costumes or special items used in rituals, may be important and meaningful primarily through their use in performance, rather than through their sheer materiality. In recognition of this, Clavir, the former Senior Conservator of the Museum of Anthropology (MOA), University of British Columbia, influentially argued that Western-trained conservators’ typical focus on maintaining the physical integrity of objects might eclipse attention to crucial aspects of their conceptual integrity. She and like-minded conservators such as Marian Kaminitz, Nancy Odegaard, Renata F. Peters, and Glenn Wharton pioneered collaborative forms of conservation practice in which individuals whose cultures made such objects advise museums on how best to care for them. Conservators who themselves belong to Indigenous communities, among them Tharron Bloomfield, Rose Evans, and Kararaina Te Ira, have also transformed the field by folding their cultural practices and knowledge into it.

Sometimes, the best way to preserve performative objects is to perform them. While object-focused conservation tends to oppose wearing historical garments, museums whose collections are still closely connected to living communities may approach the problem differently. Indeed, it is not unprecedented for collection objects to leave the safety of the museum to be used and worn by people outside it, even when such objects are old and fragile. Clavir calls on conservators to ‘preserve the cultural significance of material heritage under their care,’ since ‘it is due to this significance that the material is being preserved’ (Clavir Citation2009, 145). In short, performance is a form of conservation, even if it sometimes clashes with the established practices of objects conservation.

Conservator Nyssa Mildwaters discusses the display of Māori kākahu (cloaks) that was part of the 2015 exhibition Hākui: Women of Kāi Tahu, which took place at Dunedin’s Otago Museum. Though the kākahu – made of feathers, hair, plant fibers, and natural dyes – are often quite fragile, Mildwaters argues that their meaning cannot be separated from ‘their relationship to the body, movement and sound when worn’ (Mildwaters Citation2017, 3). The museum’s conservators donned several of the precious and unstable kākahu in its collection in order to create films that were shown in the galleries. Mildwaters emphasizes that taonga – often translated as ‘treasure,’ this Māori term describes both tangible and intangible Indigenous heritage in New Zealand – ‘is defined by its relationship to living people.’ Thus, New Zealand museums ‘act as guardians of kākahu, which leave the museum for use and wear at important events such as graduation ceremonies, weddings and funerals’ (Mildwaters Citation2017, 3).

Indeed, for several decades, conservators have collaborated with communities to determine the proper care, installation, and use of items originating in their cultures. This work is sometimes called ‘peoples-based conservation.’ Recognizing that proper care sometimes involves use, some museums run loan programs, facilitating the travel of items to people whose culture created them. These items include performative objects such as masks, jewelry, headdresses, or other elements worn during rituals, dances, or other ceremonies. In 1996, the National Museum of the American Indian (NMAI) in Washington, D. C. honored such a loan request from the Confederated Tribes of Siletz Oregon. On behalf of his community, Robert Kentta, then Siletz Cultural Resources Protection Specialist, asked that dance regalia – including dance wands, hair plumes, a head band, a collar, a necklace, and a dress – be loaned to be worn for the Nay Dosh or Feather Dance (Kaminitz and Kentta Citation2005). The museum’s conservators understood that these items might be changed by their use in performance but felt that such changes would contribute to keeping the meaning of an ‘archived’ item alive.

This is described well by Dena Klashinsky, a cultural worker of the Musqueam and Mamalilikulla communities: ‘I think that such change and the accompanying history enrich an object,’ she told Clavir. ‘It’s not as if objects need to be static or stagnant to be of value! I especially don’t believe that change, just because it’s recent, diminishes an object. Tradition and continuity exist in the context, in how those objects are used and what stories they tell. That’s what’s important to maintain’ (Clavir Citation2002, 170–171). Focused on new media and installation art, Renée van de Vall, Hölling, Tatja Scholte, and Sanneke Stigter also conclude that ‘a work does not necessarily stop changing when it enters a museum collection’ (van de Vall et al. Citation2011, 4). Going even further, they propose that conservators might ‘reverse our perspective regarding the work’s continuous existence as the standard, and threats or interruptions of this continuity as the exception’ (van de Vall et al. Citation2011, 5). Like complex installations, performances may lie dormant for years. Once it is musealized, a performative object might easily crumble to dust before it has the chance to be activated.

Collaborations like the one initiated by Kentta are predicated not only on the recognition that Indigenous people have the right to help determine the proper care of the items created by their culture, but also on the notion that the objects themselves benefit from this use: Performing them may potentially threaten their materiality, but it preserves their meaning. As Muñoz-Viñas argues, ‘The ultimate goal of conservation as a whole is not to conserve’ the physical substrate of an object, ‘but to retain or improve the meaning it has for people’ (Muñoz-Viñas Citation2005, 213). Since the 1996 loan discussed above, conservation programs at leading museums such as NMAI, MOA, and Te Papa in New Zealand have embraced the performativity of their collections by collaborating regularly with individuals and communities who recognize them as both tangible and intangible expressions of their own cultures. Yet performance is universal, and decades later, Western conservation has been slow to recognize the performative demands of objects from Western cultures. How might fashion conservation transform if it were to accept fashion’s performativity as a criterion of responsible preservation?

Fashion, dead or alive

I do not mean to equate an Indigenous community’s right to access and use its own heritage with a collaboration between a wealthy celebrity and a for-profit museum. But the comparison is not as absurd as it may at first seem. Like the Siletz dance regalia, Monroe’s dress is a performance costume, an object never intended to sit inert behind glass, but to be spectacularly activated by a human body. But now that the dress has been taken out of the everyday world and installed in a museum context, standard museum practice dictates that it should never again be part of that world. Scaturro has noted that ‘as fashion ‘things’ become ‘objects,’ they cease being fashion’ – an ontological transformation has taken place (Scaturro Citation2017b, 33). As curator Claire Wilcox has argued, the museological approach ‘tends to privilege the materiality of objects rather than preserving or presenting enactive aspects of dress and fashion.’ Instead, Wilcox wishes to harness the power of the live body to inspire ‘connectivity between previous and present’ (Wilcox Citation2016, 190).

In fact, writers on fashion have frequently lamented the deathly stillness of garments in galleries. Roland Barthes, whose 1967 book Système de la mode (The Fashion System) provided a semiotic analysis of fashion writing, declares elsewhere that ‘it is not possible to conceive a garment without the body (without silhouette): the empty garment, without head and without limbs (a schizophrenic fantasy), is death, not the body’s neutral absence, but the body decapitated, mutilated’ (Barthes Citation1991, 107). In Barthes’s eyes, to deprive a dress of a wearer is not merely an unfortunate, but even a violent act. For Valerie Steele, pioneering historian and director of the Museum at the Fashion Institute of Technology, ‘If fashion is a ‘living’ phenomenon – contemporary, constantly changing, etc. – then a museum of fashion is ipso facto a cemetery for ‘dead’ clothes’ (Steele Citation1998, 334). Whatever its condition, a garment in a museum is seen to be at the end of its life, detached not only from the world of fashion, but also from the body without which it is necessarily incomplete. Denise Witzig refers to museums’ fashion displays as a ‘tableau morte’ (Witzig Citation2012, 91) and Elizabeth Wilson to ‘clothes suspended in a kind of rigor mortis’ (Wilson Citation2010, 15).

Fashion scholar Julia Petrov notes the contradiction of the ‘simultaneous materiality and ephemerality of historical dress,’ which leads to ‘the near-impossibility of satisfactorily conveying the embodied experience of fashion’ in standard museum displays (Petrov Citation2019, 10–11). Writing of theatrical costume, Aoife Monks summarizes many writers’ opinions on fashion as well: ‘The costume on display only reminds us that an exhibition comprises an essentially unsatisfactory attempt to reclaim the lost theatre experience through its material afterlives’ (Monks Citation2021, 63).

Surely every garment wants a body, but Monroe’s ‘Happy Birthday’ dress is an emphatic example of how dependent fashion can be on a living, breathing human form. Though the bejeweled dress is surely one of the most famous garments in modern history, accounts of Monroe’s appearance do not emphasize the dress itself, but rather the way that it emphasized and revealed Monroe’s body. As one biographer describes the scene, as the actress slipped off her fur coat, ‘The sheer silk material of the gown seems to have melted away under the lights, and Marilyn’s magnificent body appears to be nude, covered only by hundreds of sparkling crystals’ (Casillo Citation2018, 252). Contemporary media coverage was no less avid. ‘The figure was famous,’ Time reported. ‘And for one breathless moment, the 15,000 people in Madison Square Garden thought they were going to see all of it. … A slight gasp rose from the audience before it was realized that she was really wearing a skintight, flesh-toned gown’ (Time Citation1962). U. S. Ambassador to the U. N. Adlai Stevenson recalled that Monroe had been ‘dressed in what she called “skin and beads,”’ but ‘I didn’t see the beads!’ (Nickens and Zeno Citation2012, 79). Elisabeth Bronfen may well have had this dress in mind when she wrote that ‘Often, Monroe appears as a radiant body whose white face blends seamlessly with the platinum-blonde hair and whose fair skin blends with the tight-fitting garments in such a way that one seems to perceive not the boundaries of the body, but rather a single movement of the body’ (Bronfen and Straumann Citation2002, 59).Footnote11 Notably, for Bronfen, movement is an essential aspect of the Monroe-effect.

In short, the dress was less significant for its appearance than its seeming disappearance, the way it emphasized Monroe’s materiality over its own. Through the dress, it was not Monroe’s chicness or even beauty that was performed, but rather her corporeality. In performance, the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress lost its identity as a distinct object, manifesting as a glittering haze surrounding Monroe’s figure. It represents the very extremity of fashion’s dependence on a live body. The episode recalls travel writer Bruce Chatwin’s assessment of the great French couturier Madeleine Vionnet: ‘She wanted the body to show itself through the dress. The dress was to be a second or more seductive skin, which smiled when its wearers smiled’ (Chatwin Citation1989, 87). Lacking the color and complexity of other garments by Jean Louis or Bob Mackie, the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress epitomizes fashion as an addendum to or exaggeration of the body. Citing Chatwin, Taylor adds: ‘Pity the poor curator trying to re-create all that on a plaster or fibreglass dummy’ (L. Taylor Citation2002, 26).

Without Monroe’s body, the dress is a shed skin. Truly a performative object, it scarcely exists without her. And Monroe’s absence is profound; indeed, the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress is all the more famous for its important role in one of Monroe’s last public appearances before her death just a few months later at the age of 36. Yet if the dress is meant to look and act like Monroe’s skin, if it is designed to perform her body and be, in turn, performed by it, then in wearing that same dress, Kardashian is not merely wearing Monroe’s garment but performing Monroe herself. In theorizing images of bodies, Hans Belting distinguishes between representing bodies, which perform themselves, and represented bodies, which are independent images. As he notes, ‘Bodies perform images (of themselves or even against themselves) as much as they perceive outside images. In this double sense, they are living media that transcend the capacities of their prosthetic media’ (Belting Citation2005, 311). Wearing Monroe’s dress in the limelight, Kardashian performs both her own body and Monroe’s. The performance is at once a return to the past and the genesis of something new.

To be sure, conservators, curators, and exhibition designers have always been aware of clothing’s relationship to the performing body. Ingrid Mida has discussed the once-common phenomenon of museum runway shows populated by volunteers in historical dress. Yet while Mida acknowledges ‘the irrefutable fact that clothes are shown to best advantage on a living, breathing body,’ her history of the practice concludes with the professional consensus, in the 1980s, that it is irreconcilable with responsible conservation practices (Mida Citation2015, 50). Of course, museum professionals have devised many intelligent and effective methods to help viewers imagine their former liveliness, using, for example, dynamic lighting, digital modeling, and sometimes actual, if bodiless, movement (Mida Citation2015, 45–50). Ultimately, however, these are substitutes for the real thing; their role is to compensate for the loss of a body, not to restore it. Curator Claire Wilcox sent models through the Victoria and Albert Museum for her ‘Fashion in Motion’ series (1999-2001), which was possible due to fashion’s iterability: Contemporary garments in the V&A’s collection were also available in designers’ own archives or in collectors’ closets, and these could bear the wear and tear of live performance in place of the accessioned pieces. The inviolability of the museum object is here maintained.

Wilcox’s curatorial approach could also be adapted to historical clothing through the use of replicas – which immediately raises the question of whether a replica of Monroe’s dress would have sufficed for Kardashian’s performance (as I note below, Kardashian did actually wear a copy of the dress after walking the red carpet) (). Unlike many commentators, I am not interested in arguing about what should have happened at the Met Gala. Rather, I wish to confront the reality of what actually did happen, and to assess its threat or contribution to conservation. Let us consider, then, what wearing the original article accomplishes that a replica could not. As I argued above, the dress’s value – financial and otherwise – is largely determined by its particular relationship to Monroe’s performing body. For what, then, is the dress itself worth preserving, if that intimate, physical connection is not kept alive? Ultimately, whether one approves or disapproves of Kardashian’s choice to wear Monroe’s dress, I believe she demonstrated that wearing historical garments can constitute a form of conservation, by restoring to them the movement and life that museums work so hard to still.

The dress after Marilyn

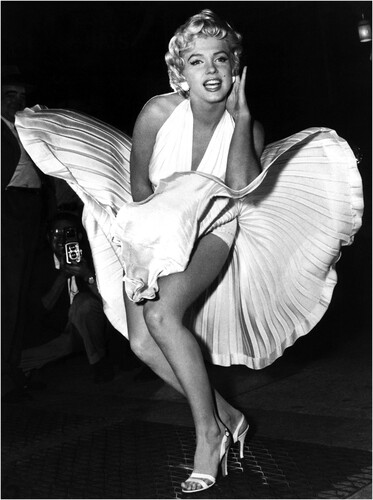

To argue this point, I will contrast the dress’s museal display with Kardashian’s wearing of it, establishing this act as a functional ‘reperformance’ and a new chapter in the dress’s biography, which is frequently restricted to one night in 1962. As far as is known, Monroe only wore the bejeweled dress on that one evening. After her death, it transformed into an item of celebrity memorabilia, reentering public consciousness and public space with a 1999 auction at Christie’s, when it was sold for $1.3 million, and again with the auction house Julien’s in 2016. It was purchased by Ripley’s Believe it or Not! for $4.8 million, thus regaining its status of most expensive dress – which had, in the meantime, been claimed by another dress that had been worn by Monroe. This other, equally famous dress is the pleated ivory halter, designed by William Travilla, that Monroe wore in Billy Wilder’s 1955 film The Seven Year Itch (). The well-known scene in which Monroe’s dress is animated by a gust of air from the subway as she stands over a metal grate on a New York City sidewalk was filmed on location and deliberately engineered as a publicity stunt by Wilder (the scene was later reshot on set) (). Here, too, the inherent performativity of the dress is essential to its meaning and value.

Figure 6. William Travilla’s pleated halter dress for Monroe displayed on a mannequin. Photo by Doug Kline, from Wikimedia Commons.

Figure 7. During a publicity shoot for the film The Seven Year Itch, Monroe wears a pleated dress designed to move dramatically. Photo from Wikimedia Commons, originally published by the Associated Press.

At Ripley’s, as it was at the 2016 sale, the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress is displayed on an off-white fabric dress form, a type of mannequin described by Taylor as ‘Headless, armless and characterless’ (L. Taylor Citation2002, 28). Unlike the mannequins popular in earlier eras, which sometimes attempted lifelike detail, such deliberately neutral forms focus attention on the garment itself as a discrete museum object and away from its performativity. This effect was even more extreme in 1999, when the dress was displayed on an all-but-invisible form that had been ‘reverse engineered’ from the dress’s measurements to precisely replicate Monroe’s body at the time she wore it (Brooks Citation2016, 19). The dress thus seems to hold itself miraculously erect, as if inhabited by Monroe’s ghost. While realistic wax mannequins with carefully-rendered facial features and hair were preferred in the earliest exhibitions of fashion, and smooth, featureless, often gray mannequins were used in more recent decades, such invisible forms are a popular contemporary solution to the uncanniness often inspired by artificial, human-like bodies made to wear human clothes (Brooks Citation2016; Cooks and Wagelie Citation2021; David Citation2018; L. Taylor Citation2002, 24–50). Invisible forms follow the contours of the body while abstracting it away. This abstraction allows a garment to be appreciated as an independent work of art and encourages viewers to use their imagination, but it also disembodies fashion. Made of supportive and stable materials, such forms help preserve the garment, but absent both body and movement – which, as I have endeavored to show, are especially crucial to this particular dress – they may hinder our understanding of the dress as a performative object. If we were to imagine the conservation of Monroe’s performance of and in the dress, it might not look so very different from Kardashian’s appearance at the Met Gala.

Kardashian, a kind of A-list influencer, is frequently the object of tongue-wagging headlines in gossip magazines for the ups and downs of her personal life (her parents, siblings, and ex-husband Kanye West are also frequented by paparazzi), for her sometimes dubious product endorsements, and perhaps above all, for her body. Like Monroe herself, Kardashian is an avatar of American glamor all over the world – and like Monroe, her skin, weight, and general appearance have been relentlessly scrutinized by the tabloid press as well as the public. Monroe was obsessed with her appearance; indeed, the ‘Happy Birthday’ dress was designed, in its revealing form and second-skin fit, to show off a figure newly chiseled by strenuous dieting. This means that, like Kardashian, who embarked on an extreme diet in advance of the Met Gala, Monroe, too, lost weight to fit into the dress – an echo backwards in time.

Allowing our gaze to blur Kardashian into Monroe can serve to recall how much derision and vitriol was aimed at Monroe, today considered an untouchable icon, during her all-too-brief career. Indeed, Kardashian’s reinhabitation of Monroe’s dress may be disturbing precisely because it reminds us that Monroe was not only an icon, but a real person of flesh and blood. Film scholar Racquel Gates argues that though Kardashian’s persona and performance differ from Monroe’s, ‘what Kardashian does offer – and what might actually be in service of Monroe’s legacy – is to make visible the labor of image creation, something that would have destroyed the mysterious allure of the Monroe persona in the star’s own time’ (Gates Citation2022). The stakes of Kardashian’s performance are broader than they may initially appear.

Kardashian asked Ripley’s if she might borrow the dress for the Met Gala, and they agreed – it was surely excellent publicity for them – provided that she could don it without altering or unduly stressing the fabric. (There was no fee, but Kardashian agreed to make charitable donations to two organizations in the Orlando area.) A replica sent by Ripley’s was a good fit, but it was made of contemporary, elastic materials, and Kardashian subsequently found that she was unable to wear the original (). She then took on an intense diet and exercise regimen, losing 16 pounds in three weeks. Though this was treated witheringly by the media, Kardashian herself compared the transformation to preparing for a film role, noting that weight loss or gain by actors like Christian Bale and Renée Zellweger is considered a sign of their commitment to the performance (Devine Citation2022; Konstantinovsky Citation2022).Footnote12 Kardashian approached her Met Gala performance – for what else can it be called? – with intense seriousness.

Episode eight of the second season of The Kardashians portrays her final visit to Ripley’s in Orlando. Two white-gloved assistants pull the dress from a clothes hanger and pool it onto the floor. Kardashian wears only a pair of shorts, a shapewear garment, as she steps into the center, and the assistants carefully lift the dress over her legs. They manage to pull the garment over Kardashian’s hips and shoulders, but the zipper running down the back cannot be zipped up. Twill tapes placed at its top keep the dress closed. A gap is left on Kardashian’s bottom in the shape of a vesica piscis – exposing the shapewear that matches not her own skin, but the color of the dress – but from the front, the dress appears to fit. Kardashian tried on the dress three other times, when she first attempted to wear it; for a photoshoot prior to the Met Gala (); and at the event itself. At the Met Gala, Kardashian wore Monroe’s dress for less than five minutes – only for her extravagantly photographed walk up the red-carpeted stairs of the Metropolitan Museum. When she reached the top, a team of assistants was waiting to help her change into a replica, so that the original would not be subject to further damage. The replica (), made to Kardashian’s measurements (and a great deal more elastic than the inflexible material of the 1960s confection), fit her much better.

On the red carpet, Kardashian wore a Monroe-style white fur coat draped low on her arms to hide the gap, and her ‘highest stripper shoes’ to balance the difference in height.Footnote13 She also ‘bedazzled’ the exposed strip of her shapewear, adding rhinestones to turn underwear into outerwear. Kardashian claims that she founded her successful clothing company Skims because she could not find shapewear that matched her own skin color, and the company has been lauded for its wide range of tones. Monroe was famously naked under the dress; Kardashian donned a second skin designed to mediate between her body’s shape, color, and ornamentation, and that of the dress. This garment crystallizes the act of mediation – between Kim and Marilyn, 1962 and 2022 – which is perhaps the primary content of Kardashian’s performance. Indeed, mediation is the means by which Monroe’s performance is conserved.

Reperformance as conservation

The conservation potential of Kardashian’s performance of Monroe’s dress unfolds through this dialogue across time. Reliant on embodiment and action, the intangible heritage that abides in fashion and other cultural practices does not represent opposition to object-based conservation methods or indifference to the longevity of cultural heritage. Rather, it insists that conservation sometimes demands performance. The practice of conservation in the West in has traditionally focused on maintaining the physical integrity of objects, their tangible materials, often disregarding their original contexts and uses. Though many conservators recognize the shortcomings of this approach, the paradigm remains influential. This is made plain by most attempts to conserve performance art, which have long been limited to the conservation of documentation (such as photographs, film footage, press clippings, and correspondence) and so-called performance ‘relics’ (such as props, sets, objects created during a performance, and, indeed, costumes). Kardashian’s wearing of Monroe’s dress may indeed have damaged the dress itself – but at the same time, it may also have helped conserve the performance to which that dress is indelibly linked, acknowledging and facilitating its identity as a performative object. In other words, in wearing Monroe’s dress, Kardashian may have frayed its material, but she also conserved the performance.

Indeed, I assert that Kardashian was not simply wearing the dress but enacting a reperformance through – and of – it. Popularized by performance artist Marina Abramović, who has redone works of historical performance art by herself and other artists, ‘reperformance’ refers to the recreation and reinterpretation of performance works not inherently intended for multiple enactions, as was the case for much (though not all) pioneering performance art of the 1960s and 70s.Footnote14 The most effective reperformances are rarely painstaking reconstructions that attempt to mimic every detail of a past event. Rather, reperformance can be a method of reinventing and renewing the past, bringing some experiential aspects of a past performance alive for contemporary audiences. Thus, it may allow historical performances to return, recur, or resume without succumbing to the illusion that one can gain unmediated access to the past (Agnew Citation2007; Baldacci, Nicastro, and Sforzini Citation2022; Blackson Citation2007; Jones and Heathfield Citation2012). Reperformance does not replicate history, but rather measures the distance between now and then, allowing for comparison and renewal. Reperformance’s significance for conservation lies not only in its insistence on the intangible aspects of art and culture, but also in the way it frames performance itself as a form of conservation.

My understanding of reperformance is consonant with Robert Blackson’s expansive concept of reenactment, which ‘invites transformation through memory, theory, and history to generate unique and resonating results’ (Blackson Citation2007, 29).Footnote15 For André Lepecki, similarly, reenactments ‘invest in creative re-turns precisely in order to find, foreground, and produce (or invent, or ‘make,’ as Foucault proposed) difference.’ He argues that ‘This production of difference is not equivalent to the display of failures by re-enactors to be faithful to original works – but the actualization of the work’s always creative, (self-)differential, and virtual inventiveness’ (Lepecki Citation2010, 46). In this sense, a reperformance’s differences from the initial manifestation do not erode its meaning but rather mobilize meanings latent within it. Reperformance asks us to consider how a performance’s significance and effects change when their contexts – historical, cultural, bodily – are shifted. In its attempt to unite events of the past with liveness and contingency in the present, reperformance offers a method of conserving performances and performative objects without reducing them to musealized stillness.

Kardashian brought the dress – and by synecdoche, Monroe – back into the eyes of the paparazzi and the public, reigniting her memory.Footnote16 As she walked – carefully – up the red-carpeted stairs of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Kardashian’s body may have strained the threads holding those thousands of rhinestones in place, but she also set them alight in the manner originally intended by the dress’s designers. In addition to movement, glitter, and glamor, she restored other intangible qualities of the dress of which the museum context deprives it. ‘Nowadays everyone wears sheer dresses, but back then that was not the case,’ Kardashian noted. ‘That’s why it was so shocking’ (Nnadi Citation2022). A semi-transparent dress would hardly cause a scandal today. But on Kardashian’s body, this 60-year-old museum piece regained the power to shock. Inside the gala, where mobile phones, paparazzi, and the general public are forbidden, Kardashian wore a contemporary replica of the dress. This, too, constitutes a reperformance of the original dress. However, the dress’s direct connection to Monroe’s body – the characteristic upon which its fascination and value depend; the reason it has been preserved – is also the very feature that allows its public appearance to generate the kind of scandal for which both Kardashian and Monroe are both famed.

While Kardashian’s physical differences from Monroe mean that the dress fit neither her body nor her skin tone, these differences support the potential of reperformance to activate new possibilities latent in past acts. Kardashian’s appearance seems to reflect her awareness that transformation is more effective than mere copying: Though she bleached her naturally black hair to a platinum blonde tone, Kardashian wore it in a simple bun, unlike the curving wing that Monroe had debuted that night. Kardashian’s reperformance of Monroe’s dress thus confirms Rebecca Schneider’s insistence that ‘When we approach performance not as that which disappears (as the archive expects), but as both the act of remaining and a means of reappearance (though not a metaphysics of presence) we almost immediately are forced to admit that remains do not have to be isolated to the document, to the object, to bone versus flesh’ (Schneider Citation2001, 103). Here, Kardashian’s flesh reanimates Monroe’s celebrity skin.

Gates finds that ‘the dress fits Kardashian quite well – figuratively, if not literally – because of what it symbolizes about Monroe and what the subsequent whitewashing of Monroe’s image in subsequent eras has erased: a woman who constantly tried to reinvent and exert some type of agency over her public image, refusing to be shamed by scandal, and often using television as the means to do so’ (Gates Citation2022). The differences in body, identity, culture, and era between Kardashian and Monroe are enmeshed with their similarities. As a result, Kardashian’s reperformance conjures a complex set of questions about celebrity performance in the 2020s as well as the 1960s.

Conservation in motion

My aim in presenting this case is not to defend the wearing of a historical garment by a contemporary celebrity, but rather to point out that evidence of performance’s power to remain – and efforts, however unintentional, to exploit and augment that power – may be found in the unlikeliest of places, far from the conservation laboratories, museum galleries, theaters, and academic discussions where performance conservation is taking shape. In developing practical as well as theoretical strategies for engaging with the afterlives of performance, we do well to attend not only to the risks and vulnerabilities of performance, but also to its power.

Indeed, many conservators do. Scaturro, who was quoted so witheringly in the popular press, had discussed the nuances of peoples-based conservation in her statements to the media, but this was ignored in favor of a straightforward message of outrage.Footnote17 Even ICOM retracted its initial condemnation after criticism from Puawai Cairns, Director of Audience and Insight at Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa in Wellington. On Twitter, Cairns rejected ICOM’s strict prohibition against wearing textiles, noting that it no longer reflects current practices in progressive museums that hold garments, blankets, or other materials from Indigenous communities. ‘Some textiles in museums should be worn if they are of use in ritual ceremonies or continuing the connections between object and kin,’ Cairns explained, adding that ‘Conservation is increasingly about becoming the bridge to enable that to happen, not the block.’Footnote18

Henderson endorsed Cairns’s response to what she called ICOM’s ‘stark’ stance. While acknowledging that ‘Conservators attempt to preserve the fabric as well as we can,’ the purpose of doing so is ‘to maximise the possibilities of a relationship with it’ (Henderson Citation2022, 58). In her opinion, ‘Wearing garments can be part of a preservation strategy if this maintains and enhances significance. Unfortunately, conservation practice in the past has been associated with stifling an object.’ Instead of concentrating solely on materiality, Henderson urges, ‘We should invest our ethics in preserving the meaning of a thing’ (Henderson Citation2022, 58). The efforts of Indigenous cultural workers and their allies in museum practice has shown that to treat performative objects as only objects is to damage their immaterial values, as surely as improper handling damages their materiality.

Acknowledging Cairns’s criticism, ICOM clarified that ‘With the statement we wanted to address the Met Gala scenario and similar situations where a collection might be pressured to allow someone unconnected with the object to wear it.’Footnote19 Certainly no one has the right to reanimate Monroe’s dress the way Indigenous communities have a right (whether or not it is honored) to access museums’ collections of their heritage, and to ‘keep them warm,’ in Cairns’s phrase.Footnote20 But as I have endeavored to show, it may not be quite right to insist that Kardashian is entirely ‘unconnected’ to the dress. Monroe has no direct heirs, but as an American icon of feminine glamor, Kardashian is arguably her cultural descendant. Wearing the dress – which is significant less for its own materiality than for its collaboration in Monroe’s performance – activates it in a way that object-based conservation measures cannot. By returning the dress to the celebrity culture in which it originated, Kardashian, one might argue, is preserving the dress in a way that opposes yet also transcends traditional textile conservation.

Acknowledgements

This article resulted from research undertaken within the Swiss National Science Foundation project ‘Performance: Conservation, Materiality, Knowledge,’ which is based at the Institute of Materiality in Arts and Culture at Bern Academy of the Arts, Bern University of Applied Sciences. For their support, comments, and ideas I would like to thank my colleagues in that project, Hanna Hölling (project lead), Emilie Magnin, and Valerian Maly. I am additionally grateful to Sarah Scaturro, Puawai Cairns, and Hannes Bajohr for their generous assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The owner of Monroe’s dress, Ripley’s Believe it or Not!, claims that it incurred no damage. Apparently damning photographs of loose rhinestones and pulled seams taken by ChadMichael Morrisette and posted online by Scott Fortner caused a frenzy on social media, though Ripley’s asserts that the photographs only depict previously sustained stresses to the delicate fabric. Yet damage may well be invisible, and the practical realities of garment conservation make it extremely likely. My argument proceeds on the assumption that the dress’s physical integrity was indeed impaired.

2 ‘Costume,’ ‘fashion,’ and ‘dress’ are often used interchangeably when referring to the study or conservation of clothing and its history. I use ‘fashion’ and ‘dress’ in this manner, reserving ‘costume’ for those special instances of theatrical, cinematic, or similar costume. The ‘Happy Birthday’ dress at the center of this article is a special instance, representing both a performance costume and an instance of designer fashion.

3 The so-called ‘Hays Code’ limited how much skin actors could show onscreen.

4 Looking back, Jean Louis apparently recalled the use of sequins, but only rhinestones were used. Gary Vitacco-Robles reports this statement slightly differently; in his telling, Jean Louis called it ‘the nudist dress’ (Vitacco-Robles Citation2014, 427).

5 This footage can be found on YouTube.

6 The AAM specifies that ‘If a museum engages in the practice of loaning objects from the collection to organizations other than museums, such a practice should be considered for its appropriateness to the museum’s mission; be thoughtfully managed with the utmost care and in compliance with the most prudent practices in collections stewardship, ensuring that loaned objects receive the level of care, documentation and control at least equal to that given to the objects that remain on the premises; and be governed by clearly defined and approved institutional policies and procedures, including a collections management policy and code of ethics.’ Many – though not all – collection care specialists would consider Ripley’s loan to Kardashian to violate these standards. See ‘Loaning Collections to Non-Museum Entities,’ American Alliance of Museums, https://www.aam-us.org/programs/ethics-standards-and-professional-practices/loaning-collections-to-non-museum-entities/.

7 Conversation with Sarah Scaturro, 26 September 2022.

8 Healy’s discussion of ‘immateriality’ is limited almost entirely to notions of the virtual museum – i.e., how material objects may be studied and encountered in simulation through digital interfaces.

9 This lineage begins with John Searle, Austin’s primary interpreter, and continues with Jacques Derrida and Judith Butler, the last of whose approach has perhaps been most influential. Interestingly, as Loxley points out, Butler grounds her earliest writing on gender performance in the ideas of Victor Turner and other theorists who approach performance through anthropology, a lineage that is not evident in Gender Trouble (1990) and later works (Butler Citation1988; Loxley Citation2007, 141).

10 Mieke Bal calls attention to the ways in which ‘performance’ and ‘performativity’ are sometimes kept apart, though they are interdependent. Bal briefly describes performance most simply as ‘the execution of an action; something accomplished; a deed, feat,’ whereas a performative is an ‘expression that serves to effect a transaction or that constitutes the performance of the specified act by virtue of its utterance’ (Bal Citation2002, 174; Bal Citation2021; Kollnitz and Pecorari Citation2022; Parker and Sedgwick Citation1995).

11 Translation mine. ‘Oft wirkt die Monroe wie ein strahlender Körper, dessen weißes Gesicht nahtlos übergeht in die platinblonden Haare und dessen helle Haut mit den enganliegenden Kleidungsstücken derart verschmilzt, daß man keine Körpergrenzen, sondern vielmehr eine einzige Körperbewegung wahrzunehmen meint.’

12 Kardashian may not be an actor, but she is certainly a performer – and the constant public criticism of her own transformations of her body strike me as not dissimilar to criticism of performance artists like Marina Abramović or Orlan, whose bodies are their medium.

13 Kim Kardashian quoted in The Kardashians, season two, episode seven, 2022.

14 Abramović sees her reperformance practice as a preservation technique. Her major reperformance projects include Seven Easy Pieces (2005) at the Guggenheim Museum and the retrospective The Artist is Present (2010) at The Museum of Modern Art.

15 ‘Reenactment’ and ‘reperformance’ are often used interchangeably in performance writing. I prefer to distinguish the potential open-endedness of ‘reperformance’ from the precise reconstruction often demanded by ‘reenactment.’ See my forthcoming essay on simulation (Pelta Feldman forthcoming).

16 Kardashian was surprised to find that many of her young fans had not previously heard of Monroe (The Today Show, 21 June 2022).

17 Conversation with Sarah Scaturro, 26 September 2022.

18 Puawai Cairns, Twitter thread, 12 May 2022, https://twitter.com/PuawaiCairns/status/1524528643787354112.

19 ICOM Costume, Twitter thread, 17 May 2022, https://twitter.com/icomcostume/status/1526346263926558720.

20 Conversation with Puawai Cairns, 9 November 2022.

References

- Agins, T. 2005. “The Sultan of Sequins Opens His Vault.” Wall Street Journal, November 17, 2005.

- Agnew, V. 2007. “History’s Affective Turn: Historical Reenactment and Its Work in the Present.” Rethinking History 11 (3): 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/13642520701353108.

- Auslander, P. 2008. Liveness: Performance in a Mediatized Culture. London: Routledge.

- Austin, J. L. 1962. How to Do Things with Words. The William James Lectures Delivered at Harvard University in 1955. London: Oxford University Press.

- Bal, M. 2002. Travelling Concepts in the Humanities: A Rough Guide. Green College Lectures. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

- Bal, M. 2021. “How the Concept of Performativity Travels: Between People and Media.” Methis. Studia Humaniora Estonica 22 (27/28): 18–32.

- Baldacci, C., C. Nicastro, and A. Sforzini, eds. 2022. Over and Over and Over Again. Vol. 21. Cultural Inquiry. Berlin: ICI Berlin Press.

- Barthes, R. 1991. “Erté, or À la Lettre.” In The Responsibility of Forms: Critical Essays on Music, art, and Representation, translated by R. Howard, 103–128. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Bedford, C. 2012. “The Viral Ontology of Performance.” In Perform, Repeat, Record: Live Art in History, edited by A. Jones, and A. Heathfield, 78–87. Bristol: Intellect.

- Belting, H. 2005. “Image, Medium, Body: A New Approach to Iconology.” Critical Inquiry 31 (2): 302–319. https://doi.org/10.1086/430962.

- Blackson, R. 2007. “Once More … with Feeling: Reenactment in Contemporary Art and Culture.” Art Journal 66 (1): 28–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00043249.2007.10791237.

- Borggreen, G., and R. Gade, eds. 2013. Performing Archives - Archives of Performance. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.

- Bronfen, E., and B. Straumann. 2002. Die Diva: eine Geschichte der Bewunderung. Munich: Schirmer/Mosel.

- Brooks, M. M. 2016. “Reflecting Absence and Presence: Displaying Dress of Known Individuals.” In Refashioning and Redress: Conserving and Displaying Dress, edited by D. Eastop, and M. M. Brooks, 19–32. Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute.

- Butler, J. 1988. “Performative Acts and Gender Constitution: An Essay in Phenomenology and Feminist Theory.” Theatre Journal 40 (4): 519–531. https://doi.org/10.2307/3207893.

- Büscher, B., and F. A. Cramer, eds. 2017. Fluid Access: Archiving Performance-Based Arts. Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag.

- Casagrande, B. 2017. “A Report from the Audience: The Multi-Perspective Witness Report as a Method of Documenting Performance Art.” VCR Beiträge 2: 95–99.

- Casillo, C. 2018. Marilyn Monroe: The Private Life of a Public Icon. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

- Chatwin, B. 1989. What Am I Doing Here. London: Picador.

- Clavir, M. 2002. Preserving What Is Valued. Vancouver: UBC Press.

- Clavir, M. 2009. “Conservation and Cultural Significance.” In Conservation. Principles, Dilemmas and Uncomfortable Truth, edited by A. Richmond, and A. Bracker, 139–149. London: Victoria and Albert Museum.

- Cooks, B. R., and J. J. Wagelie, eds. 2021. Mannequins in Museums: Power and Resistance on Display. London: Routledge.

- Costume Society of America. 1987. Resolution Encouraging the Prohibition of Wearing Objects Intended for Preservation.

- David, A. M. 2018. “Body Doubles: The Origins of the Fashion Mannequin.” Fashion Studies 1 (1): 1–46. https://doi.org/10.38055/FS010107.

- Desvallées, A., and F. Mairesse, eds. 2010. Key Concepts of Museology. Paris: Armand Colin.

- Devine, K. 2022. “Kim Kardashian Finally Speaks out on Her Weight Loss for the Met Gala.” Mail Online, June 3, 2022, sec. TV&Showbiz. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/tvshowbiz/article-10881413/Kim-Kardashian-speaks-Met-Gala-weight-loss-comparing-Christian-Bales-transformation.html.

- Gates, R. 2022. “Kim Kardashian Gives Us a Glimpse of How Hard It Was to Be Marilyn Monroe, the Star.” CNN, May 10, 2022. https://www.cnn.com/2022/05/10/opinions/marilyn-monroe-kim-kardashian-met-gala-dress-gates/index.html.

- Giannachi, G., and J. Westerman, eds. 2018. Histories of Performance Documentation. New York: Routledge.

- Healy, R. 2020. “Immateriality.” In The Handbook of Fashion Studies, edited by S. Black, A. de la Haye, J. Entwistle, R. Root, A. Rocamora, and H. Thomas, 325–346. London: Bloomsbury.

- Henderson, J. 2020. “Beyond Lifetimes: Who Do We Exclude When We Keep Things for the Future?” Journal of the Institute of Conservation 43 (3): 195–212. https://doi.org/10.1080/19455224.2020.1810729.

- Henderson, J. 2022. “The Dress and the Power of Redress.” News in Conservation 90: 58–59.

- Hölling, H. B. 2017. Paik’s Virtual Archive: Time, Change, and Materiality in Media Art. Oakland: University of California Press.