ABSTRACT

Educators have a critical stake in supporting the development of interest—as the presence of interest benefits sustained engagement and learning. Neuroscientific research has shown that interest is distinct from, but overlapping with, self-related information processing, the personally relevant connections that a learner makes to content (e.g., mathematics). We propose that consideration of self-related information processing is critical for encouraging interest development in at least two ways. First, support for learners to make self-related connections to content may provide a basis for the triggering of their interest. Triggered interest encourages individuals to search for more information, and to persevere in understanding material that otherwise might feel meaningless. Second, for learners who already have an initial interest in the content, self-related connections can further promote the deepening of interest through sustained engagement and information search. Background regarding both interest and self-related information processing is provided, and implications for practice are suggested.

Educators and psychologists have long acknowledged the power of interest (e.g., Dewey, Citation1913; James, Citation1890) and have pointed to its centrality in learning. They have recognized that what individuals attend to and understand is informed by their interest. Early on, psychologists such as Arnold (Citation1910) and Claparède (Citation1905) suggested that interest was a biological force that influenced learning. More recently, neuroscientists have been able to demonstrate that the power of interest is rooted in physiology providing an explanation of its beneficial outcomes: the way in which the brain processes self-related information (the links between individuals’ personal experience and content to be learned, e.g., Hidi et al., Citation2017, Citation2019), how it activates reward circuitry (e.g., Gottlieb et al., Citation2013), and makes interest rewarding.

Interest describes the ways in which individuals engage with content (e.g., mathematics, guitar, writing). It is both a psychological state and a motivational variable that leads to reengagemnt in a content-related activity (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2016). Research has shown that interest develops through 4 phases, starting with the initial triggering of interest that draws attention to that content, such as self-relatedness (relation to the self), novelty, intensity, and so forth (Hidi & Renninger, Citation2006; Renninger & Hidi, Citation2019).Footnote1 Moreover, regardless of age, race or ethnicity, socio-economic status, or prior experience, all individuals may be supported to develop, or renew, an interest in particular content (see Renninger & Hidi, Citation2019, Citation2020). This is critical information, as having an interest in what one is learning significantly benefits attention (e.g., Hidi, Citation1995; McDaniel et al., Citation2000), memory (e.g., Renninger & Wozniak, Citation1985), goal setting (e.g., Harackiewicz et al., Citation2008), sustained engagement (e.g., Azevedo, Citation2013), and performance (e.g., Crouch et al., Citation2018; Jansen et al., Citation2016). However, there remain unanswered questions for educators about how best to provide support for interest to develop: for example, why is it that some learners sustain engagement following the triggering of interest, and others do not? And why is it that for some learners, interest continues to develop and deepen almost effortlessly? Critical insight into questions such as these can be provided by considering the links that individuals are prepared to make between content and themselves through self-related information processing. For example, when under-represented minority students working with professors on biomedical research identified the benefits of their investigation for their own communities, they were more psychologically involved in their work over time than majority students who did not receive this support; they also had an increased interest in pursuing a scientific research career (Thoman et al., Citation2015).

Encouragement to engage in self-related information processing benefits educators as well as learners when it is coupled with support to develop interest. Self-representation has been described as an integration hub for information processing (Sui & Humphreys, Citation2015). In other words, when learners make self-related connections to information they need to process, their self-prioritization benefits the quality of these connections. Helping learners identify self-related connections to the content they are learning supports interest development in at least 2 ways. First, making connections to the self provides a basis for the triggering of interest. Triggered interest encourages individuals to search for more information, and to persevere in understanding material that otherwise might feel meaningless. Second, for those who already have an initial interest in the content, self-related information processing can promote deepening of interest through sustained engagement and information search. Self-related processing plays an increasing role in engagement as interest develops.

In this article, we explain the importance of educators’ supporting learners’ interest development (e.g., Conklin, Citation2018; Dyson, Citation2020; Xu et al., Citation2012), and the benefits of coupling these efforts with opportunities for learners to engage in self-related information processing. We provide background information about both interest development and self-related information processing. Following this, we describe specific implications for practice.

InterestFootnote2

Interest is a cognitive and affective motivational variable that develops; its components include knowledge, value, and feelings. Renninger and Hidi (Citation2016) provided a case illustration of the changing relation between knowledge and coordinated valuing, and the positive feelings which characterize interest development. They described an adolescent named Emma, and the development of her interest in photography. Briefly, Emma who received a camera for her birthday, and had no prior interest in photography, had her interest triggered by the camera. She enjoyed taking pictures, and did so frequently, and eventually began to catalog the photos she took. One day, she noticed the instructions that were in the bottom of the camera case and read them. This led her to learning about light, distance, focus, etc. and her increased effort to improve the quality of the pictures that she was taking. She enjoyed the related activities and her knowledge and the value for the activity continued to develop. Of note, the information search related to her developing interest was rewarding and self-related—she was cataloging her pictures and wanted to improve her technique. Indicators that Emma’s interest was developing were (1) the frequency of her picture taking, (2) the deepening of her knowledge about it, (3) that she was voluntarily engaged, and (4) that she would engage independently. These are measures that have previously been discussed as easily used by teachers in classrooms, as well as by researchers (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2016; Renninger & Wozniak, Citation1985).Footnote3

Interest has been repeatedly shown to benefit learning in all content areas in and out of school, and regardless of the demographic characteristics of the learner. For example, Jansen et al. (Citation2016) reported that once developed, interest predicted ninth-grade students’ (N = 39,192) achievement across 5 subject areas (biology, chemistry, German, math, and physics). Comparable findings have been reported in studies of young children’s literacy (McTigue et al., Citation2019) , middle school students’ work with writing (Lipstein & Renninger, Citation2007), undergraduate students’ interest in biology (Knekta et al., Citation2020), and adults’ computer literacy (Beh et al., Citation2015), as well as in out-of-school settings ranging from connected learning in massive online games (MOOCS; Ito et al., Citation2019), to involvement in Do-it-Yourself activity (Barron et al., Citation2014), computing science workshops (Lakanen & Isomöttönen, Citation2018), and museum exhibits (Lewalter et al., Citation2014).

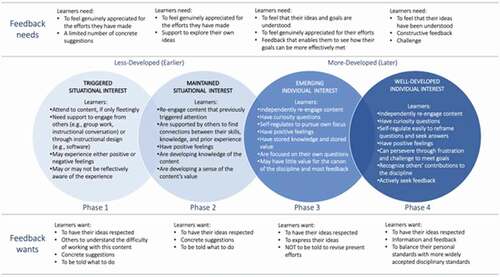

In the Four-Phase Model of Interest Development, Hidi and Renninger (Citation2006) described interest as a progression of deepening knowledge and value, beginning with the triggering of a person’s interest, which if sustained, may grow into a well-developed interest (see ) (Hidi & Renninger, Citation2006). They further explained that the process is not linear, and that it exists and develops through interactions of the person and the environment. As Alexander et al.’s (Citation2019) longitudinal study illustrates, from preschool through adulthood there may well be “off-ramps” as well as “on-ramps” in the development of an interest such as science, and other people (e.g., educators, including parents) can play a supporting role.

Figure 1. Learner Characteristics, feedback wants, and feedback needs in each of the four phases of interest development. Adapted from “Interest and Identity Development in Instruction,” by K. A. Renninger, Citation2009, Educational Psychologist, 44, p. 108. Copyright 2009 by Taylor & Francis, LLC.

Although existing interests of learners typically drive their engagements, learners may also be supported to develop a new interest in additional content—even if the content was of no interst to them previously. For example, the experience of an assignment to study and care for an Indonesian box turtle triggered an adolescent’s interest (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2002). As depicted in , learners in the earlier phases of interest development are likely to require the support of other people or the design of the environment to experience content that they want to return to (see Renninger & Hidi, Citation2019). By contrast, in the later phases, learners’ own search for information has activated the reward circuitry and information search becomes rewarding. In other words, neuroscientific evidence explains the many positive effects of interest—once interest is triggered and sustained, information search becomes rewarding. further illustrates that learners’ wants as well as their needs are aligned with the process of their interest development (see data and discussion reported in Lipstein & Renninger, Citation2007; Renninger & Hidi, Citation2019; Renninger & Lipstein, Citation2006; Renninger & Riley, Citation2013).

The development of interest is always initiated by the triggering of interest, a process that propels information search and may be:

serendipitous: e.g., when worms being used in an experiment died, students asked to reorganize the focus of their assignment to include a dissection (e.g., Renninger, Citation2010);

promoted by other people: e.g., using writing prompts to support student reflection on the utility of what they are learning (see discussion of utility value interventions such as this in Hulleman et al., Citation2017); lectures, labs, or in-class activities that include surprising or novel information, (e.g., Dohn, Citation2013; Nieswandt & Horowitz, Citation2015; Palmer et al., Citation2016); or

self-generated: e.g., students recognize the connections between the content covered in their chemistry and physics classes, and continue to think about how the information is related (Crouch et al., Citation2018; Renninger & Hidi, Citation2019).

When learners are led to continue to work with the content of a triggered interest, this may lead to self-generated information search, and continued development of interest (Renninger et al., Citation2019).

Renninger et al. (Citation2019) reported that in an out-of-school inquiry-based science workshop for inner-city, middle-school age learners, the triggering and maintaining of interest occurred in a wide variety of instructional contexts. This included whole-class discussions, presentations to others, work with challenging content, sustained individual activity, and spontaneous activity. They also described triggering as sometimes co-occurring—in other words, triggers for interest did not exist in isolation, and that some triggers such as working in groups “worked” for some of the youth, but not necessarily for others who were less social. Moreover, they found that when triggers for interest were self-related (e.g., they involved personal relevance, character identification, or ownership), they were more likely to result in sustained interest. Subsequently, Renninger et al. (Citation2014) examined the role of using open-ended ICAN prompts (e.g., ICAN write some examples about how an animal can use its sense to find things out about its environment)Footnote4 to promote a similar cohort’s recognition of the self-related links they were ready to make to the science content of the inquiry-based activities (For additional examples and classroom application, see discussion in Renninger & Riley, Citation2015). Findings from this work indicated that compared with matched controls who did not receive the intervention, those with less, as well as those with more, interest in science not only sustained interest, but their performance improved. They also found that the more ICAN probes to which participants responded, the greater their science understanding. The researchers explained that the intervention worked because the probes emphasize reflection—there is no limit on the number of connections that the participants make. Moreover, the connections that the participants do make to the inquiry activity are their own, and because the probes follow rich problem-based content, they have plenty to write about.

In their study of the middle school classrooms of eight exemplary African-American teachers, Xu et al. (Citation2012) provided details about ways to trigger and sustain the development of interest. For example, they described the teachers’ classrooms as caring, organized such that all students were encouraged to engage and/or to get back on track as this was needed (e.g., the teacher stood next to a student’s desk, awaiting continued effort). They reported that the teachers’ employed multiple instructional approaches to concepts (e.g., technology, hands-on activity, involvement of the local community), and recognized that including opportunities to engage with content in different ways is important. They also observed that the teachers were explicit about scaffolding their students’ interest in science. In fact, Xu et al. noted that the students were motivated to learn science because their teachers were themselves interested in the subject, and in cultivating their students’ interest in it.

Self-related information processing

Self-related information processing (also referred to as self-specific information processing) refers how individuals work with content that is personally relevant to them (e.g., Hidi et al., Citation2019; Sui & Humphreys, Citation2015). Hidi et al. (Citation2017, Citation2019) bridged the disciplinary silo between neuroscience and educational and social psychology by reviewing neuroscientific studies addressing self-related information processing. Neuroscientists have demonstrated that that self-related, or self-specific, information processing plays a critical and beneficial role in memory, perception, and decision-making; they have reported that people self-prioritize, and are biased toward the self (e.g., Sui & Humphreys, Citation2015). On the strength of these findings, Hidi and her colleagues argued that self-related processing could address the open question of researchers in educational and social psychology about why, for example, utility value interventions are positioned to close achievement gaps in learning (e.g., Priniski et al., Citation2018). Specifically, they (Hidi et al., Citation2017, Citation2019) suggested that utility interventions—such as having students identify the relation between their research and themselves–leads them to self-related information processing that triggers interest. Further, the experience of interest results in information search that is rewarding because of the activation of the reward circuitry.

In other words, educators can identify or frame the potential for interest and promote information processing that enables personal connections, and this is particularly beneficial for meaningful (as opposed to routine) learning. Before interest begins to develop, or when it does not exist at all, individuals may need support from other people and/or the design of the tasks that they are assigned, in order to make meaningful connections to the content that they are learning. As they begin to make these connections themselves, they are able to begin to generate their own questions, which leads to them to information search, and the activation of the reward circuitry. As interest develops and deepens, engagement with the content becomes inherently rewarding for the learner.

Making use of information about self-related processing in teaching and/or working with learners in any context can provide them with an essential boost. Although the development of interest and self-related information processing are distinct processes in the brain, they also overlap (Hidi et al., Citation2017, Citation2019). This overlap is the reason that interest development becomes self-generated as interest develops.

Findings from studies of the self have demonstrated that people encode information in the brain differently when it is related to their sense of self. In an early meta-analysis of 129 studies of memory, Symons and Johnson (Citation1997) reported that self-reference strategies that involved actively encoding information related to the self results in superior memory relative to other-referent and semantic encoding strategies. Sui and Humphreys’ (Citation2015) in their description of self-representation as an integration hub for information processing, pointed out that self-representation serves to bind together different types of information. They showed that (1) self-reference helps bind individuals’ memories to their source, (2) increases their perceptual integration, (3) and once a personal association of the self to content is made, this is not likely to change; (4) self-referencing of this type influences individuals’ decision-making, and (5) increases interactions between brain regions. They concluded that self-reference provides associative “glue” for perception, memory, and decision making, and thus is a central mechanism for information processing. Similarly, Kolvoort et al. (Citation2020) noted that neuroscientists have shown that the self and its related processing modulate behavioral responses related to reward, attention, perception, action, emotion, and decision-making, and thus have been operationalized in terms of self-relatedness.

To understand the benefits of self-related information processing, neuroscientists have also examined its association with the activation of the reward circuitry and concluded that reward-self neural overlap occurs in the brain’s subcortical-cortical reward circuitry (e.g., Ersner-Hershfield et al., Citation2009; De Greck et al., Citation2008; Zhan et al., Citation2016). Interest development has been linked to both self-related information processing and reward. These data indicate a unique role for educators in supporting learners by adapting their instruction to encourage self-related information processing. For example, they may encourage students to identify personal links, or connections to the content, and/or in designing activities and tasks, they may draw on and enable the learner to make such meaningful connections on their own. Thus, educators can enable learners with little existing interest to make self-related connections to content. This type of support is essential as it may be a first step toward ensuring that engagement with content is interesting and feels rewarding. Furthermore, the connection to content knowledge is critical for generating information search that can activate the reward circuitry; individuals who have more developed interest, already make such connections on their own.

Implications for practice

Although not discussed in terms of self-related processing, Hecht et al.’s (Citation2021) research addressing the efficacy of different formats of a utility value intervention in supporting undergraduate students’ interest in biology suggests that self-related information processing differs for those with little to no interest and those with more developed interest. Hecht and his colleagues studied two conditions, one in which learners were provided with information about the utility of learning biology, and another in which they were supported to make self-related connections to the biology content (for example, by writing). The researchers reported that only those with an already existing interest showed increases in their interest in biology when they received information about the utility value of biology. Those with no interest needed to receive the second condition, in which they were required to write about their own associations to the utility of the content. This condition also led to increased interest for all students. The authors concluded that the utility value intervention serves as a trigger for interest development. Their data offer evidence that although learners with an existing interest in biology are able to make use of information provided to them, uninterested learners may need encouragement to generate their own self-related connections to the content.

The Hecht et al. (Citation2021) findings are consistent with those of other utility value interventions that have shown increases in interest as well as achievement, especially for challenged learners (e.g., Hulleman et al., Citation2017). The results also echo those of Renninger et al.’s (Citation2014) study of middle school age youth’s work with open-ended ICAN prompts. Taken together, these investigations suggest that providing students with tasks that encourage them to reflect on what they have been doing in class can be helpful to them. Rather than telling students what connections they should see/conclusions they should draw, etc. and telling them why learning biology is useful, educators could instead ask their students to explain what they mean, or how they figured something out. Importantly, this type of adjustment to instruction does not require changes to the curriculum.

Other approaches to providing self-related content for students may involve revisions of the curriculum to include culturally relevant content and/or personalized text and problems. Like the changes to incorporate self-related content in instructional practices, changes to the curriculum have also been shown to benefit students’ learning. Studies of cultural relevance in which the context of school-based assignments are changed to explicitly include experiences of others who look like the students can be important (e.g., Clark, Citation2017; Ladson-Billings, Citation1995; Lee, Citation1992). Clark (Citation2017), for example, reported that incorporating culturally relevant texts in reading instruction for grade 1–5 students had a significant effect on their reading progress; importantly, she also reported that the amount of the reading instruction that was culturally relevant corresponded to the amount of progress the students made. Similarly, personalizing the context of problem solving (based on the students’ individual out-of-school interests, such as baseball) has been shown to benefit middle school, high school, and/or college students’ learning of mathematics (e.g., Bernacki & Walkington, Citation2018).

Studies such as these provide evidence of the power of educators’ adapting their instructional practices to promote their students’ self-related processing, and in turn providing a basis for their interest development. Although people like Emma may have their interest triggered, and serendipitously find and read the directions that enable her to improve her photography, the possibility of students in most classes similarly finding a key that leads them to make meaningful connections to content is not common. The importance of educators’ supporting their students to make self-related connections to the content that they teach cannot be emphasized enough—it could level the playing field (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2020). Not only does support of self-related information processing enable connections to the content to be learned, but it may serve to trigger and sustain students’ interest, that in turn offers opportunities for exploration, practice, and the development of conceptual understanding.

Concluding thoughts

In the classroom, teachers can look for indicators of the level of their students’ interest in the way that their students engage: whether they opt to return to working with content overtime, the increasing depth of their engagement, whether they voluntarily engage, and if they will do so independently (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2016; Renninger & Wozniak, Citation1985). When learners have an interest in what they are doing, they are able to self-generate rewarding information search (Renninger et al., Citation2019). However, when there is little to no interest, efforts to enable the learner to identify their own links to the content to be learned are critical. Support provided by encouraging self-related information processing is likely to promote the motivation to reengage, ongoing interest development, and learning.

There are 2 aspects of interest that explain its power. The first is its association with the activation of the reward circuitry. The second is the self. Once interest is triggered and maintained, related information search is rewarding, and external rewards, while appreciated, may not be needed (Hidi & Renninger, Citationin press). As a person’s interest develops, it is increasingly likely to become an aspect of a person’s identity (Renninger, Citation2009). For those who have yet to develop an interest, support to make self-related connections during the triggering of interest has the benefit and ensuing reward of enabling learning and promoting the development of interest.

Additional Resources

1. Humphreys, G.W. & Sui, J. (2015). Attentional control and the self: The Self Attention Network (SAN), Cognitive Neuroscience, 21(1-4). https://doi.org/10.1080/17588928.2015.1044427

In this article, the authors describe that although self-related information captures attention, the role of self-bias is modulated by social context.

2. Priniski, S. J., Rosenzweig, E. Q., Canning, E. A., Hecht, C. A., Tibbetts, Y., Hyde, J. S., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2019). The benefits of combining value for the self and others in utility-value interventions. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111, 1478–1497. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000343

This utility-value intervention study suggests ways in which educators may design interventions that can increase student interest and performance.

3. Scalabrini, A., Xu, J., & Northoff, G. (2020). What COVID-19 tells us about the self: The deep intersubjective and cultural layers of our brain. PCN Frontier Review. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13185

Based on considerations related to the pandemic, this article describes a 2‐stage model of self that includes both neuro‐social‐ecological and psychological levels.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge Meghan Bathgate’s assistance in designing , and J. Melissa Running’s editorial support. We are also most appreciative of research support provided by the Swarthmore College Faculty Research Fund.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The term “triggering interest” is a modification of Dewey’s (Citation1913) use of the word “catch” that is related to the initial phase of interest. As Hidi (Citation2000) explained, the problem with the word catch is that it implies the existence of an already experienced interest.

2. Interest is often used interchangeably with the term intrinsic motivation. Although interest is intrinsically motivating, they are not synonymous terms. First, intrinsic motivation is not necessarily associated with interest; for example, it can be triggered by beliefs. Second, whereas intrinsic motivation is not described as having an extrinsic component, interest by definition includes a person’s interactions with the environment and, as such, these include external forms of support and potential reward.

3. These indicators have been used in surveys, interviews, logfile analysis, and observational protocols (Renninger & Hidi, Citation2016).

4. The ICAN Intervention is an adaptation and extension of the use in some K-12 classrooms of I can statements to assess student learning, and specifically D. Chaconas’ (personal communication) use of these in his professional development support for mathematics and English Language Learning. Our use of “ICAN” is not an anacronym, but rather a positive affirmation that in responding to the prompt, individuals “can” respond to it, that is they can link the content to themselves.

References

- Alexander, J. M., Johnson, K. E., & Neitzel, C. (2019). Multiple points of access for supporting interest in science. In K. A. Renninger & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 312–352). Cambridge University Press.

- Arnold, F. (1910). Attention and interest: A study in psychology and education. Macmillan.

- Azevedo, F. S. (2013). Knowing the stability of model rockets: A study of learning in interest-based practices. Cognition and Instruction, 31(3), 345–374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07370008.2013.799168

- Barron, B. J., Gomez, K., Pinkard, N., & Martin, C. K. (2014). The digital youth network: Cultivating digital media citizenship in urban communities. MIT Press.

- Beh, J., Pedell, S., & Doube, W. (2015). Where is the “I” in iPad?: The role of interest in older adults’ learning of mobile touch screen technologies. In OzCHI ’15 Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest Groupf for Computer Human Interaction (pp. 437–445). Parkville, Australia. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1145/2838739.2838776

- Bernacki, M. L., & Walkington, C. (2018). The role of situational interest in personalized learning. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(6), 864–881. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000250

- Claparède, E. (1905). Psychologie de l’enfant et pétagogie expérimentale. Kundig.

- Clark, K. F. (2017). Investigating the effects of culturally relevant texts on African American struggling readers’ progress. Teachers College Record, 119(5), 1–30. https://www.tcrecord.orgIDNumber:21756

- Conklin, H. G. (2018). Caring and critical thinking in the teaching of young adolescents. Theory into Practice, 57(4), 289–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2018.1518643

- Crouch, C. H., Wisittanawat, P., Cai, M., & Renninger, K. A. (2018). Life science students’ attitudes, interest, and performance in introductory physics for life sciences (IPLS): An exploratory study. Physical Review Physics Education Research, 14(1). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1103/PhysRevPhysEducRes.14.010111

- De Greck, M., Rotte, M., Paus, R., Moritz, D., Thiemann, R., Proesch, U., Bruer, U., Moerth, S., Tempelmann, C., Bogerts, B., & Northoff, G. (2008). Is our self based on reward? Self-relatedness recruits neural activity in the reward system. Neuroimage, 39(4), 2066–2075. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.11.006

- Dewey, J. (1913). Interest and effort in education. Houghton Mifflin.

- Dohn, N. B. (2013). Situational interest in engineering design activities. International Journal of Science Education, 35(12), 2057–2078. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2012.757670

- Dyson, A. H. (2020). “This isn’t my real writing”: The fate of children’s agency in too-tight curricula. Theory into Practice, 59(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00405841.2019.1702390

- Ersner-Hershfield, H., Wimmer, G. E., & Knutson, B. (2009). Saving for the future self: Neural measures of future self-continuity predict temporal discounting. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 4(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsn042

- Gottlieb, J., Oudeyer, P.-Y., Lopes, M., & Baranes, A. (2013). Information seeking, curiosity and attention: Computational and neural mechanisms. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 17(11), 585–593. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2013.09.001

- Harackiewicz, J. M., Durik, A. M., Barron, K. E., Linnenbrink, L., & Tauer, J. M. (2008). The role of achievement goals in the development of interest: Reciprocal relations between achievement goals, interest, and performance. Journal of Educational Psychology, 100(1), 105–122. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.1.105

- Hecht, C. A., Grande, M. R., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2021). The role of utility value in promoting interest development. Motivation Science, 7(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/mot0000182

- Hidi, S. (1995). A re-examination of the role of attention in learning from text. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 323–350. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02212306

- Hidi, S. (2000). An interest researcher’s perspective: The effects of extrinsic and intrinsic factors on motivation. In C. Sansone & J. M. Harackiewicz (Eds.), Intrinsic and extrinsic motivation: The search for optimal motivation and performance (pp. 311–342). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012619070-0/50033-7

- Hidi, S., & Renninger, K. A. (2006). The four-phase model of interest development. Educational Psychologist, 41(2), 111–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2006.09.001

- Hidi, S. E., Renninger, K. A., & Northoff, G. (2017). The development of interest and self-related processing. In F. Guay, H. W. Marsh, D. M. McInerney, & R. G. Craven (Eds.), International advances in self research. Vol. 6: SELF – Driving positive psychology and well-being (pp. 51–70). Information Age Press.

- Hidi, S. E., Renninger, K. A., & Northoff, G. (2019). The educational benefits of self-related information processing. In K. A. Renninger & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 15–35). Cambridge University Press.

- Hidi, S. E., & Renninger, K. A. (in press). Reward, reward expectations/incentives, and interest. In M. Bong, S. Kim, & J. Reeve (Eds.), Motivation science: Controversies and insights. Oxford University Press.

- Hulleman, C. S., Kosovich, J. J., Barron, K. E., & Daniel, D. B. (2017). Making connections: Replicating and extending the utility value intervention in the classroom. Journal of Educational Psychology, 109(3), 387–404. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000146

- Ito, M., Martin, C., Rafalow, M., Tekinbas, K. S., Wortman, A., & Pfister, R. C. (2019). Online affinity networks as contexts for connected learning. In K. A. Renninger & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 291–311). Cambridge University Press.

- James, W. (1890). The principles of psychology. Macmillan.

- Jansen, M., Lüdtke, O., & Schroeders, U. (2016). Evidence for a positive relation between interest and achievement: Examining between-person and within-person variation in five domains. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 46, 116–127. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2016.05.004

- Knekta, E., Rowland, A. A., Corwin, L. A. & Eddy, S. (2020). Measuring university students’ interest in biology: Evaluation of an instrument targeting Hidi and Renninger’s individual interest. International Journal of STEM Education, 7(23). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/s40594-020-00217-4

- Kolvoort, I. R., Wainio-Theberge, S., Wolff, A., & Northoff, G. (2020). Temporal integration as “common currency” of brain and self-scale-free activity in resting-state EEG correlates with temporal delay effects on self-relatedness. Human Brain Mapping, 41(15), 4355–4374. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.25129

- Ladson-Billings, G. (1995). Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy. American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–491. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312032003465

- Lakanen, J. A., & Isomöttönen, V. (2018). Computer science outreach workshop and interest development: A longitudinal study. Informatics in Education, 17(2), 341–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15388/infedu.2018.18

- Lee, C. D. (1992). Literacy, cultural diversity, and instruction. Education and Urban Society, 24(2), 279–291. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0013124592024002008

- Lewalter, D., Geyer, C., & Geyer, C. (2014). Comparing the effectiveness of two communication formats on visitors’ understanding of nanotechnology. Visitor Studies, 17(2), 159–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10645578.2014.945345

- Lipstein, R., & Renninger, K. A. (2007). “Putting things into words”: The development of 12-15-year-old students’ interest for writing. In P. Boscolo & S. Hidi (Eds.), Motivation and writing: Research and school practice (pp. 113–140). Elsevier. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1163/9781849508216_008

- McDaniel, M. A., Waddill, P. J., Finstad, K., & Bourg, T. (2000). The effects of text-based interest on attention and recall. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(3), 302–492. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.3.492

- McTigue, E. M., Solheim, O. J., Walgermo, B., Frijters, J., & Foldnes, N. (2019). How can we determine students’ motivation for reading before formal instruction? Results from a self-beliefs and interest scale validation. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 48, 122–133. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2018.12.013

- Nieswandt, M., & Horowitz, G. (2015). Undergraduate students’ interest in chemistry: The roles of task and choice. In K. A. Renninger, M. Nieswandt, & S. Hidi (Eds.), Interest in mathematics and science learning (pp. 225–242). American Educational Research Association.

- Palmer, D. A., Dixon, J., & Archer, J. (2016). Identifying underlying causes of situational interest in a science course for preservice elementary teachers. Science Education, 100(6), 1039–1061. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.21244

- Priniski, S. J., Hecht, C. A., & Harackiewicz, J. M. (2018). Making learning personally meaningful: A new framework for relevance research. The Journal of Experimental Education, 86(1), 11–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2017.1380589

- Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2002). Student interest and achievement: Developmental issues raised by a case study. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccles (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 173–195). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/b978012750053-9/50009-7

- Renninger, K. A. (2009). Interest and identity development in instruction: An inductive model. Educational Psychologist, 44(2), 1–14. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520902832392

- Renninger, K. A. (2010). Working with and cultivating interest, self-efficacy, and self-regulation. In D. Preiss & R. Sternberg (Eds.), Innovations in educational psychology: Perspectives on learning, teaching and human development (pp. 158–195). Springer.

- Renninger, K. A., & Riley, K. R. (2013). Interest, cognition, and the case of L__ in science. In S. Kreitler (Ed.), Cognition and motivation: Forging an interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 325–382). Cambridge University Press.

- Renninger, K. A., Austin, L., Bachrach, J. E., Chau, A., Emmerson, M., King, R. B., Riley, K. R., & Stevens, S. J. (2014). Going beyond “Whoa! That’s cool!” Achieving science interest and learning with the ICAN Intervention. In S. Karabenick & T. Urdan (Eds.), Motivation-based learning interventions, Vol. 18, Advances in motivation and achievement (pp. 107–140). Emerald Group Publishing. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/1507497423.2014.0000018017

- Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. E. (2019). Interest development and learning. In K. A. Renninger & S. E. Hidi (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of motivation and learning (pp. 265–296). Cambridge University Press.

- Renninger, K. A., Bachrach, J. E., & Hidi, S. E. (2019). Triggering and maintaining in early phases of interest development. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 23, 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2014.999920

- Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. (2016). The power of interest for motivation and engagement. Routledge.

- Renninger, K. A., & Hidi, S. E. (2020). To level the playing field, develop interest. Policy Insights from the Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 7(1–9). https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2372732219864705

- Renninger, K. A., & Lipstein, R. (2006). Come si sviluppa l’interesse per la scrittura; Cosa volgliono gli studenti e di cosa hannobisogno? [Developing interest for writing: What do students want and what do students need?]. Età Evolutiva, 84, 65–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/30047170

- Renninger, K. A., & Riley, R. R. (2015). The ICAN intervention: Supporting learners to make connections to science content during science inquiry. Science Scope, 39(4), 49–53. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2505/4/ss15_039_04_49

- Renninger, K. A., & Wozniak, R. (1985). Effect of interest on attentional shift, recognition, and recall in young children. Developmental Psychology, 21(4), 624–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.21.4.624

- Sui, J., & Humphreys, G. W. (2015). The integrative self: How self-reference integrates perception and meaning. Trends in Cognitive Science, 19(2), 719–728. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2015.08.015

- Symons, C. S., & Johnson, B. T. (1997). The self-reference effect in memory: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 121(3), 371–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.121.3.371

- Thoman, D. B., Brown, E. R., Mason, A. Z., Harmsen, A. G., & Smith, J. L. The role of altruistic values in motivating underrepresented minority students for biomedicine. (2015). BioScience, 65(2), 183–188. minority students for biomedicine. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/biosci/biu199

- Xu, J., Coats, L. T., & Davidson, M. L. (2012). Promoting student interest in science: The perspectives of exemplary African American teachers. American Educational Research Journal, 49(1), 124–154. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3102/0002831211426200

- Zhan, Y., Xiao, X., Li, F., Fan, W., & Zhong, Y. (2016). Reward promotes self-face processing: An event-related potential study. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 735. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00735