Abstract

Research investigating British Sign Language (BSL) – and sign languages more generally – from systemic functional perspectives is gradually increasing but remains nascent overall. The current paper offers a step towards a steadily growing set of functional descriptions of BSL, focusing on the nominal group and potential nominal functions. The findings of a small-scale analysis of publicly accessible BSL data are presented. Videos of BSL users were analyzed to identify patterns regarding nominal functions, wherein Thing, Epithet, Classifier, Numerative and Deictic were observed. These five functions are exemplified and examined in order to dissect how nominal elements may be realized. The summary section of this paper offers a reference table comprising the observations made in this paper for each of the five functions noted above, as well as areas for further investigation. The observations and conclusions drawn in this work can be used as a stable base from which future functional studies and descriptions of sign languages may grow.

1. Introduction

The domain of systemic functional analyses and descriptions of languages is an area of sustained growth, both in terms of the languages covered (evidenced by the range of languages found in this special issue series) and the theoretical developments accompanying them (e.g., Martin, Doran, and Figueredo Citation2020). In terms of sign languages, such as British Sign Language (BSL), this analytical and descriptive work is still very much at an emerging stage of development, although gradual steps are being made wherever possible. The current paper proposes one such step towards this growing set of descriptions of BSL, with a focus on the nominal group. Nominal groups primarily realizes entities, such as people, places, and objects, and organize resources to present and track these entities. Much research on nominal aspects of sign languages occurs through the lens of their formal syntactic organization (see, inter alia, Cecchetto Citation2017; Sandler and Lillo-Martin Citation2006; Sutton-Spence and Woll Citation1999), but functional perspectives are yet to be addressed in detail.

This work offers a preliminary exploration of the nominal group in BSL through the analysis of authentic BSL data. Following this introduction, Section 2 provides the theoretical context to the work in terms of the frameworks and assumptions employed, drawing together information from both sign linguistics and systemic functional theory. As BSL operates in the visual-spatial modality, Section 3 discusses certain considerations to bear in mind when attempting to identify lexicogrammatical units and elements within signed productions that are associated with nominal functions. Section 4 presents a methodology for this study that is taken up in the analysis in Section 5, wherein nominal group resources similar to those seen in other languages, such as resources used to identify, describe, quantify and track entities, are exemplified and discussed. This is performed with a particular focus on the functions of Thing, Epithet, Classifier, Numerative and Deictic. Finally, Section 6 draws together the main observations from this investigation, alongside various pathways for future study.

The purpose of this paper, perhaps differing slightly to that of the other papers available in this special issue, is not to present system networks or full realization statements for the paradigmatic choices regarding the nominal group of BSL. Before being able to reliably present such systems and statements, there needs to be greater access to, and much further analysis of, BSL data. Rather, this paper focuses on an essential basis of description, delivering insight into how nominal groups and functions in BSL may be identified, and considerations of how these functions may be realized lexicogrammatically.

Throughout this work, examples of BSL will be glossed using adapted conventions found in sign language linguistics. These conventions are as follows:

UPPERCASE text represents English glosses of BSL signs.Footnote1 Hyphens between uppercase words represent a sign needing more than one English word to accurately gloss the meaning.

‘+’ symbols after uppercase text indicates a marked repetition of a manual sign. The number of ‘+’ used indicates the number of observable repetitions. These repetitions may be phonologically reduced (e.g., repeated with faster or incomplete articulation).

‘DC:’ indicates a Depicting Construction, in which a signer uses combinations of articulators to refer to specific entities, manners of handling and interaction, and so on (see Cormier et al. Citation2012).Footnote2

‘PT:’ indicates a pointing sign, which can be used:

o pronominally (PRO) or possessively (POSS), with combinations of:

▪ person (‘1’ – signer, ‘2’ – addressee, ‘3’ – other); and

▪ number (‘SG’ – singular, ‘PL’ – plural);

o to identify a physical location (LOC); or

o as a determiner (DET).

2. Theoretical context

This current work uses a combination of theoretical tenets from both sign linguistics and systemic functional linguistics. From sign linguistics literature, a broad system of classification found in sign languages based on lexical status is employed (Hodge and Johnston Citation2014). From systemic functional literature, cryptogrammatical reasoning and trinocularity are employed. The combination of these three domains have been used in similar works describing BSL from systemic functional viewpoints (e.g., Rudge Citation2021, Citationforthcoming). Explanations of foundational concepts in systemic functional linguistics such as metafunction, stratification, system, and so on, can be found in Martin, Doran, and Zhang (Citation2021).

Hodge and Johnston (Citation2014) present corpus-based insights into defining lexicogrammatical units in Auslan (Australian Sign Language, a dialectal relative of BSL; see Johnston Citation2002). Within this work, they offer a categorization framework for signs based on a sliding scale of lexicalization, namely: fully lexical, partly lexical, and non-lexical. Fully lexical signs “have most meaningful characteristics specified in their form and are heavily entrenched in use [and] constitute the listable lexicon” (Hodge and Johnston Citation2014, 267). Partly lexical signs contain a level of conventionalized meaning, but often require co-text and the signing space (i.e., where a signer’s hands move and interact during production) for clear comprehension (e.g., depicting constructions; see the glossary in Section 7 for more information on these constructions). Non-lexical signs, however, “have very little conventionalization or specification of form and meaning” (ibid.). While attempts could be made to categorize signs in terms of the linguistic categories often employed in descriptions of spoken and written languages (e.g., typical ‘parts of speech’ such as nouns, verbs, and adjectives), this approach soon encounters problems. This is not least because of the multiple embodied articulators used in sign languages (i.e., the hands, face, direction of eye gaze, use of signing space, and so on) that concurrently produce aspects of meaning. Of course, meanings that are ‘more nominal’ or ‘more verbal’ can still be interpreted, but it is through Hodge and Johnston’s (Citation2014) categorisations based on lexical status – specifically the categories of fully lexical and partly lexical signs – that the analysis and description of sign languages can be made easier. This will be elaborated on below.

Cryptogrammatical reasoning concerns the patterns of structure and function found within a language, allowing for covert categories and relations to be uncovered. This entails a broad distinction between the notions of enation – instances of language that have identical underlying structures – and agnation – grouped instances of language that “reveal a recurrent contrastive relation” (Quiroz Citation2020, 107; see also Gleason Citation1965). In tandem with cryptogrammatical reasoning is the idea of approaching the analysis and description of a language from a trinocular perspective: from above, from roundabout, and from below (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014). In brief, any description of language from an SFL perspective should be performed from three viewpoints. In the context of this study, the ‘from above’ viewpoint concerns the stratum of discourse semantics and its systems, namely ideation (when viewed ideationally) and identification (when viewed textually). ‘From roundabout’ concerns the lexicogrammatical stratum and the status of the nominal group, including its relation to and interaction with other groups (e.g., verbal). From below concerns the domain of expression and its link to the composition of nominal groups (i.e., signs overall and, in many cases, the manual, non-manual, and visual-spatial components found within them). The remainder of this section will expand on this trinocularity from above, and then move on to further discussions of perspectives from roundabout and from below.

Regarding the ideational metafunction, systems such as ideation are implicated here because entities that are either subject to, or are performers of, actions, occurrences, and states, are typically realized through nominal groups (Martin et al. Citationin press). Following Halliday and Matthiessen’s (Citation1999) foundational work that explores the realization of experience through language, experiential phenomena at (discourse) semantics may be separated into three configurations: sequences (complex phenomena), figures (individual ‘units’ of phenomena) and elements (components that can be configured into phenomena). For example, assuming the three elements of ‘a pigeon,’ ‘seed,’ and the action of ‘eating,’ these can combine to make a figure (e.g., a pigeon ate some seed), which in turn could be combined with another figure to create a sequence (e.g., a pigeon ate some seed and then she flew away). As may be derived from these examples, these discourse semantic components are typically realized in the lexicogrammatical stratum by clause complexes for sequences, clauses for figures, and groups/phrases for elements. Furthermore, when observing the lexicogrammatical stratum from an ideational perspective, it is nominal groups that tend to realize the experiential Participant function. This is summarized succinctly by Halliday and Matthiessen (Citation1999): “participants are realized by nominal groups, which are made up of both things and qualities” (p.184, emphasis added).

While the nominal group is a lexicogrammatical resource available for realizing meanings concerning ideational factors such as people, places, things, and their related attributes, the textual metafunction also plays a part. Martin et al. (Citationin press) explain that any text may have a greater or lesser reliance on the language employed to ‘do the work’ of successful communication. For example, where language is used to accompany and/or support actions within a physical context, such as directing someone to a local landmark, the work required of language is significant but not isolated (e.g., multimodal aspects such as gesture and other forms of non-verbal communication may assist communicative production and comprehension; see Ngo et al. Citation2021). Reading a novel, however, requires much more of the language in use to ensure that a reader can successfully understand and follow the plot and narrative (i.e., who does what, when, and how). The discourse semantic system of identification, which concerns how participants are presented and tracked and is typically realized through the nominal group, is particularly significant here in terms of resources for marshaling this relative context-dependency. In brief, the nominal group offers a way for the ‘who, what, and where’ of a text to be referenced and tracked to ensure continuity in comprehension.

3. Identifying the nominal group: initial considerations of ‘from roundabout’ and ‘from below’

Considerations of nominal aspects of sign languages from more formal perspectives are available across a range of sign linguistics literature (e.g., Baker and Pfau Citation2016; Sandler and Lillo-Martin Citation2006; Sutton-Spence and Woll Citation1999). Considerations from systemic functional points of view are, however, novel. In this section, I consider how BSL nominal groups look in comparison to other types of group (i.e., from roundabout) and how nominal groups are composed (i.e., from below).

British Sign Language, like other sign languages, is visual-spatial in its nature. The upper body and its multiple articulators (i.e., the head, different parts of the face, arms, hands, and torso) may be used to produce meaning at any given time within three-dimensional space. This poses a level of analytical complexity that requires further explanation.

Covered in further detail in Rudge (Citation2020), the lexicogrammar of BSL can be schematized into a rank scale similar to those seen in systemic functional descriptions of other languages (e.g., Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014). The ranks of clause, group, word and morpheme are discernible, with this latter rank being more appropriately presented as expanded into three co-occurring elements of manual, non-manual and spatio-kinetic components.Footnote3 This simultaneity cannot be easily seen when expressed in a linear gloss using written English, so splitting the morpheme rank into more discrete components assists with the understanding of how form and meaning intertwine in BSL.

An example is provided in to demonstrate how different lexicogrammatical ranks may be presented in the clause PHONE PT:DET DC:PHONE-VIBRATE-FACE-DOWN (translated as That phone vibrated while face down; see ). Although not exemplified in this lexicogrammatical rank scale, accurately delimiting a clause into groups is informed by visual prosody: marked changes in certain embodied features (e.g., the height of the signer’s eyebrows) as a signal for boundaries between lexicogrammatical units (see Dachkovsky, Healy, and Sandler Citation2013; and Rudge Citationforthcoming, for greater detail on this matter). It is therefore useful to specify at this point that all examples provided in this work have been subject to such analytical rigor when identifying clause and group boundaries.

Table 1. Exemplification of the lexicogrammatical rank scale of BSL.

shows a lexicogrammatical composition of one clause (a clause simplex) which is in turn formed by two groups, which at this stage will take the broad attributions of a nominal group (PHONE PT:DET) and a verbal group (DC:PHONE-VIBRATE-FACE-DOWN). The nominal group consists of two separate signs: PHONE,Footnote4 realized manually by fully lexical manual sign and the silent mouthing of the word phone on the signer’s lips, and PT:DET, realized manually by an index finger pointing towards a location in the signing space, arbitrarily labeled here as location ‘x.’ Using ‘from above’ reasoning, this lexicogrammatical group is nominal as it refers to a specific thing in a specific location, thereby delimiting the identification of this particular phone from the concept of ‘phones’ in general. This preliminary example begins to identify a core notion: a nominal group can be identified through the occurrence of fully lexical signs referring to entities and, if applicable, any accompanying partly lexical signs indicating some sort of referencing for the entity.

The remainder of the clause is labeled as a verbal group, given that it is providing information with regards to the action of the entity (i.e., vibration) and the manner of this action (i.e., with the face of the phone downwards).Footnote5 This verbal group is realized by a depicting construction (DC) wherein the action is presented through partly lexical means. In this case, the signer’s right hand is flat, representing a flat entity (i.e., the phone), oriented so that the palm is facing downwards, and shaking slightly to imitate the vibrations of a phone receiving a notification. The flat hand is situated in the signing space in location ‘x,’ indicated by the preceding pointing sign, and the signer employs facial articulators to express the extent to which the vibration is occurring.

DCs thus call upon multiple embodied articulators to create an efficient method of expressing more verbal meaning in BSL, therefore being more strongly associated with the verbal group. In relation to the current study, though, it can be observed that DCs can only do this if the entity in question forms a part of this production in some way. In the example given in , PHONE formed a part of the nominal group and was later represented in a different manner (i.e., as a flat handshape). This alternative manner of producing the ‘phone’ entity is not optional in this DC, but had this DC has been produced without the preceding nominal group, the ‘flat object’ entity would not be specific (i.e., it could represent a phone, a sheet of paper, a book, and so on). Meaning expressed in the preceding nominal group is therefore necessarily incorporated into the verbal group through alternative lexicogrammatical resources. In terms of the analyses offered within the scope of this preliminary investigation, it is proposed that nominal facets may be ‘echoed’ within some verbal groups.

This example highlights two considerations to bear in mind while moving through to the main data-driven investigation in this paper. Firstly, the simultaneous nature of BSL production cannot be ignored at this level of investigation. The complexities afforded by multiple articulators require an approach to analysis that looks beyond singular ranks and considers meaning production as the total of an embodied ensemble at any given point in time. Secondly, there are potential ambiguities to be explored in the delimitations of specific groups or specific functions. The fact that a predominantly ‘verbal’ area of a clause may still require the realization of nominal aspects presents questions concerning linear segmentation and whether functions can be confidently attributed to such groups. This latter consideration would also be a worthwhile research endeavor across other sign languages and in comparison to languages operating in other modalities.

4. Methodology

Recent evolutions in the ability to both capture and access video media, facilitated in part by a near-ubiquity of internet access, has proved useful for linguistic study. This is perhaps even more vital for studies of sign languages like BSL, given that even as recently as a few decades ago such access would have only been possible with specialist hardware and skills. As it stands, obtaining instances of authentic language use is easier than ever before, and BSL is no longer an exception to this rule.Footnote6

Thanks to these advancements, charities and services offering support to the deaf community have been able to reach their target audience in an appropriate linguistic manner. One such example in this domain is the Royal Association for Deaf people (RAD) who have made BSL videos available via YouTube covering vital information concerning safety and government policy throughout the Covid-19 pandemic. This includes but is not limited to: explanations of public welfare initiatives; updates on scientific knowledge (e.g., how viruses are understood to be transmitted between hosts); and information on government guidelines, such as clarification on rules for different local lockdown levels. At the time of writing, there are just over 100 publicly accessible videos published by the RAD on these topics.Footnote7

As these videos are published on a publicly accessible platform to distribute critical information, they have the potential to be viewed by a broad population of BSL users. It therefore follows that the BSL produced in these videos would need to be as clear and as comprehensible as possible. Not only does this permit a greater level of accessibility within their primary communicative function, but from an academic perspective, it also functions as a useful corpus of authentic BSL usage and a rich open dataset from which to investigate language in action.

For this study, four videos from the RAD’s YouTube channel were randomly selected and then transcribed and analyzed using the EUDICO Linguistic Annotator (ELAN Citation2021). Within ELAN, multiple transcription tiers (i.e., levels of time-aligned annotations) were used to demarcate features such as individual sign boundaries, potential clause and group candidates, and free translations. This was performed with a specific focus on the more ‘nominal’ aspects of BSL production to ensure that the analysis could be performed efficiently, although this was not to the exclusion of more ‘verbal’ aspects (as was reasoned in the previous section).

Several hundred nominal group candidates were observed and analyzed for this study. For the sake of brevity, indicative examples of patterns observed via cryptogrammatical and axial reasoning will be used to demonstrate the configurations and composition of nominal groups in BSL.

5. First steps in exploring the nominal group of BSL

This section explores the nominal group of BSL through the gradual identification of different functions. Wherever possible, the functions presented here are comparable to the functions found in functional descriptions of other languages, so as not to add further terminological complexity into the field. This is not to say that all nominal group functions found in other languages will be present in BSL, and it must be stipulated that this work actively avoids what Quiroz (Citation2018) refers to as transfer comparison: “a [deliberate] search for structural categories similar to those proposed in English” (140). As such, in cases where established definitions of a function may not fully align with what is observed in BSL, further explanation will be provided.

Examples from the dataset noted in the methodology are presented in this section. These are offered in a glossed format to highlight groups and functions, accompanied by figures to show the BSL production in question.Footnote8 In some cases, these are elaborated further with observations from datasets from previous studies and descriptions of BSL (e.g., Rudge Citation2021) to further explore the points made.

5.1. Thing

Ideationally, the nominal group will tend to be where the realization of participants in the clause are found. Nominal groups may be realized by multiple functions, yet will most likely (although not exclusively) include the central function of the Thing: “the semantic core of the nominal group” (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014, 383).

A Thing may be realized as the sole sign within a nominal group, as presented in examples (1) and (2):

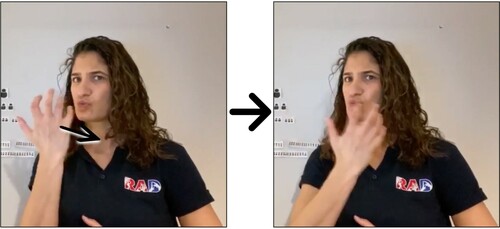

The signs in examples (1) and (2) are fully lexical and are accompanied by a silent mouthing of an associated English word during the manual production of the sign (i.e., ‘home’ and ‘gym,’ respectively). As shown in , these signs may be static in their production or have a degree of movement. Furthermore, the relationship to meaning of fully lexical signs may be placed on a scale between ‘iconic’ and ‘arbitrary,’ with both (1) and (2) falling somewhere between these poles as metonymic. The former could be argued to represent the roof of a house, and the latter as a series of actions associated with a fitness activity.

However, as suggested earlier in this paper, it is not just fully lexical signs that can realize a nominal function. As shown in example (3) and demonstrated in , partly lexical signs can also realize nominal functions. Prior to what is shown in example (3), the signer identified and gave introductory information about viruses to establish the main topic of interest (i.e., the topical Theme; see Rudge Citationforthcoming) in this preliminary stage of the discourse. Example (3) was then produced immediately after the signer’s indication that the virus can be transmitted and caught by people:

The primary function of example (3) is to highlight that if a virus is contracted by someone, then it is likely to become established within the body. Example (3) thus explains an occurrence (i.e., through a verbal group) concerning a previously mentioned entity and a new entity. Put briefly: the signer’s hands realize the Thing (a virus) carried forward from the immediately preceding discourse; the movement of the hands serves to indicate the occurrence of shifting, traveling, or spreading; and the location of the hands realizes an additional entity – the body. While BODY exists as a fully lexical sign in BSL, the realization of ‘body’ as a nominal entity in this example is instead incorporated into the verbal group.Footnote9 Consequently, while the DC carries a predominantly verbal function, thereby ascribing it as a verbal group, its components can nonetheless realize entities, similar to that which would be realized nominally as Thing.

Before moving into other functions, one further instance is useful to observe to demonstrate that there may not always be a ‘one sign one function’ correlation. This is presented in example (4) and :

At the start of the Covid 19 pandemic, various terms became commonplace in English-speaking discourse (Asif et al. Citation2021). This includes terms such as ‘social distancing’ (i.e., the act of being at a minimum physical distance from other people) and its variant forms like ‘social distance’ and ‘socially distanced.’ In the case of (4), this term is expressed in BSL through the fully lexical sign SOCIAL followed by the (potentially) fully lexical sign DISTANCE.Footnote10

The influence of languages used in the spoken and written modality on those in the visual-spatial modality is known, including the influence of English on BSL (Sutton-Spence Citation1999). It is argued here that this concatenation of signs is a borrowing from English instead of an inherently more visual manner of expressing the overall concept. To reinforce this, other BSL signs involving the notion of ‘social,’ such as ‘social work,’ are not expressed through the concatenation of the fully lexical signs SOCIAL and WORK, but instead have one fully lexical sign (SOCIAL-WORK).Footnote11 With that in mind, (4) is glossed as Thing with no other function. This is because it cannot be reliably confirmed that SOCIAL acts to classify DISTANCE in the same way that it has been found to do so in other languages, such as English (Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014).

5.2. Epithet

The first additional function to be recognized is the Epithet, which serves to realize “properties of the Thing represented by the nominal group along different qualitative dimensions such as age, size, [and] value” (Matthiessen, Teruya, and Lam Citation2010, 90). Like the Thing, the Epithet may be realized in various ways in BSL. Two manners of Epithet realization are presented in example (5) and in . In this instance, the signer explains some traits to look for when identifying whether an email could potentially be a misleading or a scam communication:

Figure 5. WRONG [1], EMAIL [2], OR [3] and LONG [4], and the start and end positions of DC:LONG-EMAIL-ADDRESS [5 and 6].Footnote12

![Figure 5. WRONG [1], EMAIL [2], OR [3] and LONG [4], and the start and end positions of DC:LONG-EMAIL-ADDRESS [5 and 6].Footnote12](/cms/asset/464b4380-18db-48b3-9208-6b3ccccfd873/rwrd_a_2024351_f0005_oc.jpg)

The first sign in (5) adds additional detail to the following Thing. The fully lexical sign WRONG provides the sense that the email address of the sender does not match the sender’s name, thereby associating an email address with a state or quality of being incorrect or inappropriate.

LONG is similarly produced as a separate, fully lexical sign that realizes an Epithet, but unlike the previous concatenation of WRONG (Epithet) and EMAIL (Thing), a DC is signed afterwards. The signer’s fingers wiggle as both hands move laterally across the signing space. During this time, the signer’s tongue protrudes slightly, and at the end of the production, the signer’s hands are in a position that is markedly outside of the typical signing space. This DC thus appears to realize qualities of excessive length (from spatio-kinetic information) and of something being unusual, incorrect, or jumbled (from non-manual and manual information). As such, this DC is argued to primarily realize an Epithet function that manually ‘echoes’ LONG while non-manually adding the notion that something is unusual or strange. However, there is also an ‘echo’ of sorts concerning EMAIL, not only because the co-text allows us to understand that this is what is being spoken about, but also because the location in the signing space from where the DC starts broadly matches the location that EMAIL was produced (see image [2] and [5] in ). A Thing is thereby argued to be realized within this DC, whether a direct echo of EMAIL or a more specific EMAIL-ADDRESS.

It is also worth noting the use of OR in example (5). Similar to English, OR is used as a conjunction to present alternatives. In systemic functional terms, it has an extending paratactic function which may be applied at different lexicogrammatical ranks. In the case of (5), it serves to link two nominal groups, but this could also function at higher and lower ranks. Similarly, other signs like BUT can offer comparable paratactic functionality, and other forms of parataxis and hypotaxis may be realized both in terms of manual signs and the use of signing space. This has yet to be explored in further depth, but Johnston (Citation1996) provides useful insight into how this might occur in Auslan.

Despite the centrality of Thing in the nominal group, Epithets may also be realized without an overt Thing in a nominal group. Example (6) provides one such example wherein the signer makes a judgement on the information presented in previous clauses (in this case, the ease with which a virus can spread):

As suggested by the parentheses in free translation in Example (6), the Thing to which the Epithet refers is ellipted. Rudge (Citationforthcoming) indicates that this is a textual effect wherein the topical Theme is not overtly expressed due to ease of recoverability from previous co-text. Although ellipsis is attributed to the clause rank, it is logical that the group rank will also be affected, namely via the omission of one or more nominal group functions. If example (6) were produced without previous co-text, the meaning would not be comprehensible.

Example (6) features a combination of manual and non-manual components. While WORRY provides the core meaning of this Epithet via the hands, the use of the head and face help to nuance this further (see ). In this case, the slight nod of the signer’s head and their pursed lips emphasize WORRY (i.e., the ease with which a virus can transmit from person to person is alarming and should be a cause for concern). Had the signer, for instance, nodded with greater force, employed a much wider eye aperture, and portrayed a grimace, then WORRY would be modified to a much more forceful meaning such as ‘terrifying’ or ‘very alarming.’

A final example of an Epithet is presented in (7) and , in which the signer reasserts that certain types of communications that ask for personal information are likely to be fake:

In example (7), the signer first points to a location in the signing space that was previously used to refer to the concept of scam communications (see ). By using PT:DET towards that location, followed by SCAM, there is the relationship of a Thing to an Epithet. At first glance, and based on examples seen so far, this may suggest that example (7) is a nominal group. However, the non-manual features expressed in example (7) are provided to show markers of visual prosody (see Dachkovsky, Healy, and Sandler Citation2013). Rather than one nominal group, example (7) is instead a major clause in lexicogrammatical terms, or a figure in terms of ideation.

In works such as Rudge (Citationforthcoming), instances of BSL like those in example (7) are understood to experientially realize an intensive relational process (i.e., associating an entity with an attribute) within the system of transitivity. Unlike most other transitivity process types, the realization of an experiential process function is not required in BSL – or, put another way, BSL is a zero-copula language. This experiential process type can be realized by the juxtaposition of two signs realizing two experiential Participants, with the accompaniment of appropriate visual prosodic markers.Footnote13 Consequently, example (7) has the composition of two nominal groups as proposed in (7a):

A nominal group can therefore occur in BSL with an Epithet as its head. In addition, unlike example (6), the omission of a Thing in this latter nominal group is not caused by textual effects such as topical Theme ellipsis. This is by no means unique to BSL, and many other languages have been observed to have similar structures in experientially relational clauses without an overt lexicogrammatical realization of a Process.Footnote14

5.3. Classifier

Another function proposed for the nominal group of BSL is the Classifier: that which serves to subcategorize, taxonomise, or otherwise further specify an associated Thing. In some languages, lexicogrammatical cues serve to identify when a unit of text realizes a Classifier function, such as the use of certain suffixes in Khorchin Mongolian (Zhang Citation2021). In other languages like English, the distinctions are cryptotypic, understood through both sequence and the possibility for grading.

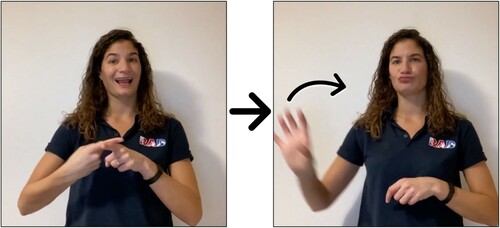

There is data to suggest that a Classifier function as separate from an Epithet function is present in the BSL nominal group. Three examples will be provided here, with example (8) (see also ) providing the first instance:

The context of (8) sees the signer explain how the UK government introduced different levels or ‘tiers’ of social restrictions in November 2020, based on infection rates in different locations. To ensure clarity in the communication, the use of ENGLAND prior to REGION helps to specify the intended information to that part of the UK, rather than to Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. ENGLAND therefore functions as a Classifier of REGIONS. Following observations seen in other languages, attempting to add some level of gradience to Classifier would result in an unusual or potentially ‘ungrammatical’ production. For instance, using a fully lexical sign beforehand such as REAL (really) or marked non-manual elements during the production of ENGLAND would impair the intended meaning.

A similar effect can be seen in example (9) (see ), wherein the signer indicates an increase in types of false or scam communications. Like example (8), FAKE serves to classify EMAIL into a certain subcategory (i.e., one that suggests they are not to be believed, and one that may be contrasted with a category of emails that are trustworthy or verifiable).Footnote15

Other group rank effects seen in previous examples can also be observed with Classifier functions, as presented in (10) (see ):

Whereas the use of OR in (5) served to paratactically extend two nominal groups, OR in (10) does so within the nominal group between words (i.e., creating a paratactic word complex rather than group complex). CORONAVIRUS thereby acts to further specify both SCAM and FRAUD as two specific ‘types’ of deceitful communication in the Covid-19 pandemic context, hence its attribution as Classifier.

A tentative observation is that the Classifier function of BSL seems to have two noticeable patterns in terms of realization. Firstly, from a syntagmatic perspective, the Classifier is produced before the Thing with which it is associated (i.e., Classifier^Thing). Secondly, a Classifier appears more likely to be realized in the form of a fully lexical manual sign rather than via partly lexical or otherwise non-manual or spatio-kinetic factors (cf. Epithet which can be realized by all of these, as seen in previous examples).

5.4. Numerative

Quantifying functions located primarily (although not exclusively) in the nominal group are seen across languages. The exact scope and precision of these quantifying functions may vary (e.g., distinctions between the functions of Quantity and Order in Korean; see Martin and Shin Citation2021), but the overall theme concerns the lexicogrammatical realization of ‘number’ in some manner, whether to identify quantity, or order, or something similar. For simplicity, the function here will be named Numerative.

In the domain of sign linguistics, expressions that have some kind of quantifying function have been explored in depth. For example, in BSL, access to individual fingers assists in representing small numbers in a highly iconic manner: the number of extended fingers from a signer’s dominant hand can represent the number being expressed (i.e., from one to five, although in some dialectal and demographic tranches of BSL, both hands can be used to express one to ten; see Stamp et al. Citation2015). Larger numbers employ more arbitrary signs in combination with these iconic signs: one hundred is expressed as a sole extended index finger (ONE) passed underneath the chin from dominant to non-dominant side (HUNDRED). The addition of certain movements to these signs can then modify the meaning further to represent temporal specificity (e.g., hours, minutes, days prior to or following the current day), and iterative or cumulative actions over time, to name a few (see Schermer Citation2016).

Three examples of BSL including a Numerative function are explored below, but it must be borne in mind that what is presented here is by no means exhaustive. There are many other ways in which a Numerative function can be realized and nuanced (see, e.g., Brentari, Horton, and Goldin-Meadow Citation2020; Stamp et al. Citation2014; Sutton-Spence and Woll Citation1999) and this could easily form the subject of entire book.

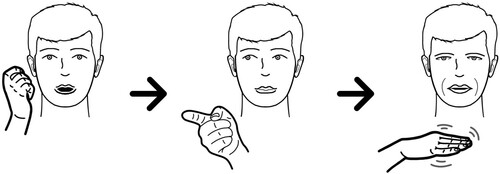

Example (11) presents the first of three examples to be discussed (see ):

As described above, the number signed in (11) is less than six, so the signer uses three extended fingers on one hand to realize this Numerative function. No additional movement is added to THREE, suggesting that it is quantifying the amount of the following Thing (i.e., ‘there are three of whatever comes next’). The signer then produces PERSON, but as identified via the use of ‘++’ in the gloss, PERSON is repeated two further times. This appears to echo the Numerative via an alternative visual manner, hence Numerative also appearing in parentheses in (11). THREE provides the specificity in this instance, and although the omission of the repetition of PERSON would not be deemed ‘ungrammatical,’ this repetition does appear to be preferred when small integers occur. If THREE were replaced with FIVE-HUNDRED, one or two repetitions may occur similar to (11), but it would not be expected that PERSON would need to be signed once and then with 499 individual repetitions.

In a similar vein to example (11), example (12) provides an example concerning the numeral ‘3:’

As shown in , there are further complexities to the use of THREE when compared to what is seen in example (11). While the same three fingers are extended, there is flexion in the joints of these extended fingers, adding a meaning of ‘quantity remaining’ (hence the gloss being given as THREE-MORE), rather than just quantity alone.

The THREE handshape then perseveres into the production of WEEK, which in turn realizes the Thing. Moving the dominant hand towards and away from the signer along the non-dominant arm forms one of many BSL ‘timelines:’ a metaphoric use of signing space to represent chronological notions (see Emmorey Citation2002). The timeline in (12) represents periods of weeks, with the dominant hand representing the number of weeks in question. Movement of the dominant hand away from the signer indicates forthcoming weeks, whereas movement towards the signer indicates weeks that have passed. The Numerative function is thus present primarily in the first sign and, similar to (11), observable as part of Thing.

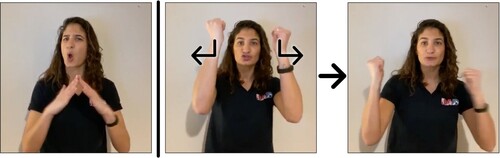

Example (13), detailed in , provides a more complex example of a potential Numerative function.Footnote16 In this context, the signer explains the UK government’s introduction of three different lockdown levels to be applied to different regions across England.

The signer begins (13) by signing LEVEL with a mouthing of ‘tier,’ with one repetition of LEVEL to suggest plurality. LEVEL is argued to realize the Thing of this nominal group as it carries the core element being communicated, although the use of repetition suggests a Numerative function, too. The signer then identifies that these levels are in a range, metaphorically indicating that there is a hierarchical relation between the levels. This second sign is therefore given a predominant Epithet function as it offers further information on the qualities of the Thing, although Thing is also realized in a partly lexical manner (i.e., through vertical space). Finally, LEVEL is signed again, this time with two distinct repetitions, each produced markedly higher than the previous one in the signing space. This third sign again appears to realize the Thing of the nominal group, but it is also a clear realization of the Numerative function via the repetition, echoing the ‘more than one’ nature suggested in the preceding signs.

When compared to examples (11) and (12), example (13) seems remarkably more complex in its production, despite all three having comparable meanings when it comes to Numerative aspects. This complexity may be understood from the perspective of the use of the English word tier. This was used frequently in UK government communications (in English) during the use of a tiered system of Covid-19 restrictions in 2020 and 2021, and although near synonymous with the word level, its usage is argued to be less frequent in everyday speech. To mitigate potential misunderstanding, then, the signer may have presented tier via the manual production of LEVEL and the silent mouthing of ‘tier,’ followed immediately by a visual representation of how tier may be understood by any viewers unfamiliar with the concept (i.e., a visual circumlocution). To maintain clear communication, these additional signs were required to offer guiding information, specifically concerning the quality and number of the functional Thing. The Epithet and Numerative functions were therefore realized to assist with this.

5.5. Deictic

The final function to be discussed is the Deictic. Unlike the other functions noted above, this is understood to be aligned with the textual metafunction as well as the ideational metafunction because it concerns aspects such as specificity and reference tracking within a text (see Halliday and Matthiessen Citation2014, for examples of this in English).

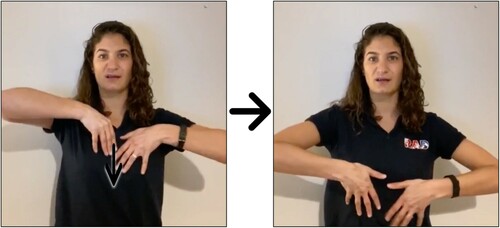

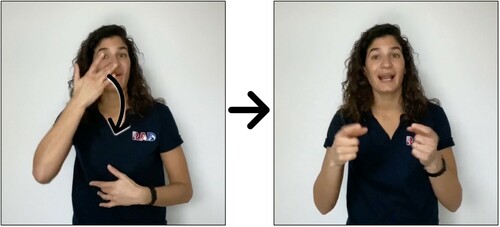

Although deixis is used across linguistic literature in the sense of referring or ‘pointing to’ aspects such as time and space (e.g., before and now, here and there, and so on), it is not as simple as looking for pointing signs in BSL to find realizations of the Deictic function. For instance, when a BSL user points directly to a participant in an interaction (i.e., PT:PRO2SG to represent the singular second-person pronoun you), this may be classed as person deixis in a traditional sense, but it is not a Deictic function in the systemic functional sense. Rather, it may act as the Thing if there are no further elements in that group that may realize the Thing function. Nonetheless, (14) provides an instance where a type of pointing sign is argued to realize a Deictic function:

The pointing sign in (14) provides specificity with regards to its associated Thing HOME. It is not the general concept of ‘home’ being referred to, but a more precise identification of a specific home that is possessed by an entity. Unlike the pointing signs seen so far, shows that PT:POSS3SG is not produced in the same form. Rather than an extended index finger, the signer instead uses a closed fist and directs the palm towards a location in the signing space. The difference in handshape configuration (i.e., pointed index vs. closed fist) gives a distinction in meaning and, in this case, function: the former often realizes a Thing, whereas the latter associates some level of ownership to the forthcoming Thing.

However, as noted throughout, it is not enough to look at the hands alone in an analysis of a sign language. Example (14) notes the location that PT:POSS3SG is directed towards the upper-right of the signing space. This location is not chosen at random. Prior to the production in (14), the signer explains that scam communications regularly target older people to gain their personal information. The signer used TARGET to indicate who is at risk, and the rightmost image of demonstrates that TARGET was signed towards a location in the signing space. It is this sign’s directional aspect that permits the entity being affected by this action (i.e., ‘those being targeted’, or in this context, ‘older people’) to be set up as a referent in the signing space. Therefore, when PT:POSS3SG is directed towards the same location, it anaphorically refers to the referent placed in that location through the abovementioned directionality of TARGET. In this example, and in many others, space therefore proves to be useful in terms of reference tracking and efficiency in communication (i.e., pointing to a referent rather than having to sign a full nominal group each time).

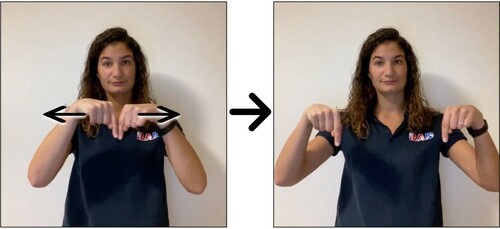

To reiterate an earlier argument, signs that ‘point’ are not always immediately attributable to a Deictic nominal function. In fact, there are instances where the precise nominal function of a pointing sign may not be clear at all. For instance, in example (15), the signer is letting the viewer know that more information on a particular topic can be found by clicking the hyperlink that is available underneath the video (when displayed on YouTube, this is usually the comment box directly beneath the media player):

Following the verbal group in example (15), the signer uses both hands with index fingers extended and pointing downwards (see ). Both hands begin in contact in a central location in front of the signer and then move apart from one another. A question mark for the nominal group function of PT:LOC as there are a few potential interpretations.

By using a pointing sign with a referent that is outside of the signing context (i.e., exophoric) but relevant in specificity – both a specific hyperlink and a specific place in which it can be found – there is the argument for it to realize a Deictic function. However, the path movement of the hands is meaningful, given that PT:LOC could have been produced with just one hand instead of two, and just pointing without any path movement. This lateral spreading movement may suggest that something with ‘length’ should be identified in the location being indicated. In the context of example (15), this could be the description box or the length of it hyperlink itself, in turn suggesting the realization of a Thing or an Epithet, respectively. There may even be a conflation of functions that can be nuanced further through the individual components of the manual production itself (e.g., handshape realizing Deictic and/or Thing; movement realizing Thing and/or Epithet, and so on).

Example (15) is provided as both a platform from which to continue work and also as a reminder that work in this area is fledgling. Understanding the many facets of a sign language from systemic functional viewpoints – whether at the nominal group or beyond – is very much a work in progress.

6. Summary and further study

The current paper has sought to offer an introduction to understanding how a nominal group and its functions may be identified and analyzed from systemic functional perspectives. Through exemplification of linguistic data, five nominal group functions found across other languages have been argued to occur in BSL. A summary of these is given in , including some of the main observations from what has been seen so far, and some of the immediate questions arising from these observations.

Table 2. Current observations and potential areas of future investigation for nominal group functions in BSL.

In addition to the areas of further study noted in , a supplementary observation from the research performed for this paper is outlined here. This work has identified functions that are most closely associated with the ideational and textual metafunctions, which seems to follow what is seen in descriptions of the nominal group in other languages. This is not to say, however, that the interpersonal metafunction should be side-lined. Some instances in the current dataset suggest that the nominal group of BSL may also realize meanings that are more appropriately associated with the interpersonal metafunction, namely areas of interpersonal hierarchy and power relations/deference. For example, one instance of the dataset shows the signer referring to a member of parliament. The signs associated with this referent are produced in a markedly higher location in the signing space than other signs. As suggested for BSL in Rudge (Citationforthcoming), and as observed in other sign languages (e.g., Llengua de signes catalana; Barberà Citation2014), the use of higher and lower ‘planes’ in the signing space may be used for realizing more interpersonal meaning, thus its association within the nominal group merits further investigation.

The observations made and the future pathways of study presented in this paper are done so with three caveats. Firstly, the above are offered based on preliminary data. As is the perennial issue in the field of linguistics, there is always more data that can be analyzed that may support or even refute what is offered here. In the case of this study, the data was monologic in its production and had the goal of presenting vital information in as accessible a manner as possible. The analysis of further contexts of use – such as interactive sequences between two or more signers, and different communicative goals – are needed to start schematizing appropriate systems for nominal groups to a reasonable delicacy.

Secondly, there are likely to be further nominal functions not described here. There is also the chance that some of the functions presented in will become unsuitable once further data is analyzed. While not presented step-by-step in this work, the data presented here were analyzed following methodologies seen across other systemic functional descriptions (i.e., combining cryptogrammatical reasoning and a trinocular perspective) to offer an idea of what might be occurring in nominal groups in BSL. However, reliance on similar work in other languages was necessary to both ground initial findings and offer some relatability to other findings in systemic functional literature.

Thirdly, and in relation to the previous point, it bears repeating that the simultaneous nature of sign language production expects a holistic perspective to linguistic analysis. Attempts have been made in this work to demonstrate and describe BSL as clearly as possible, up to the inclusion of annotated still images. However, the representation of a three-dimensional language using the two-dimensional modality of a different language understandably leads to questions of accuracy (e.g., are the glosses seen throughout this work the most efficient way of representing a sign language?). It is nonetheless hoped that these questions lead to investigations that, in turn, feed back into core systemic functional and sign linguistic theory (e.g., how might one ‘unit’ of language production be classifiable as a verbal group with nominal functions, as seen in example (3)?), so that their development and refinement may occur with new data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Uppercase words are used across sign linguistics as noted above, which is distinct from the use of small caps in systemic functional literature to identify systems.

2 Glosses of depicting constructions presented in this work do not strictly follow conventions provided by Cormier et al. (Citation2017). For ease of understanding, glosses of depicting constructions used here represent a contextualized translation rather than identifying specific primes or pro-forms of the BSL production. The author acknowledges that glosses in this format are not without issue but hopes that these can be accessed by a wider readership so that the core of the paper – nominal groups – can be understood without a requirement to know BSL to a higher degree.

3 ‘Word’ is used in the systemic functional sense (i.e., a rank in grammar; see Matthiessen, Teruya, and Lam Citation2010). Although representations of BSL are presented in this work with English glosses, attempting to fit a ‘sign’ into the same conceptual unit as a spoken or written ‘word’ is not appropriate, not least given the distinctions in productive modality.

4 PHONE in BSL: https://bslsignbank.ucl.ac.uk/dictionary/words/mobile%20phone-1.html (as can other BSL signs via the search functionality).

5 Not all verbal groups in BSL will be realized as DCs. Many fully lexical ‘verb signs’ such as SPEAK and KNOW also exist.

6 This is not to say that access to BSL is sufficient in public British contexts. Numerous issues continue to be severely under-addressed regarding access to information in BSL for the deaf community. This is despite BSL’s legal recognition as a minority language of the United Kingdom in 2003. For further background see, inter alia, work on the legal recognition of sign languages (e.g., Lawson et al. Citation2019) and recent movements from within the BSL community such as “Where is the interpreter?” (https://whereistheinterpreter.com/).

7 The YouTube playlist of these videos from the RAD can be found here: https://bit.ly/3DBCpwZ.

8 Permission to reproduce still images from the video dataset has been granted for this work from the copyright holder, the Royal Association for Deaf people (RAD). The author thanks both the RAD and the presenter from the videos in question for their consent.

9 BODY in BSL: https://bslsignbank.ucl.ac.uk/dictionary/words/body-1.html.

10 This is classed as a potential lexical sign for the following reasons. Although the realization of DISTANCE might be more akin to a DC – wherein both hands are classifiers for human participants and their moving apart signifies the distance between them – the signer mouths the word ‘distance’ during the manual production. This mouthing is a feature typically found in fully lexical signs. Furthermore, if DISTANCE were to be understood as a DC, then its intended meaning may focus more on the movement of two human participants facing one another and moving away, rather than the more abstract concept of ‘creating distance.’

11 SOCIAL-WORK in BSL: https://bslsignbank.ucl.ac.uk/dictionary/words/social%20work-1.html.

12 This form of EMAIL is not included in lexicons such as the BSL Signbank. This may be a dialectal form.

13 This interpretation also holds interpersonally (i.e., example (7) is a permissible move in discourse and permits the realization of a Predicator) and textually (i.e., the functions of Theme and Rheme can be identified successfully). See Rudge (Citationforthcoming) for further insight into the clause rank of BSL.

14 With thanks to Yaegan Doran for both identifying and elaborating on this in an earlier version of this paper.

15 This is not to say that every instance of FAKE is a Classifier. FAKE may be graded via other manual signs or non-manual aspects to express just how untrustworthy an email might be (e.g., CLEAR or OBVIOUS signed prior to FAKE to heighten the property of being overtly deceitful). In such cases, FAKE would realize an Epithet function rather than a Classifier function. This is reminiscent of Halliday and Matthiessen’s (Citation2014) fast train example, and it is the co-text of (9) that assists in reconfirming that it functions as a Classifier.

16 Note that example (13) is given with a level of caution in its presentation: what is referred to as a DC in the manual gloss may be interpreted by others as an elaborate form of a pointing sign. The choice of glossing, however, does not affect the functional analysis of the nominal group itself.

References

- Asif, Muhammad, Deng Zhiyong, Anila Iram, and Maria Nisar. 2021. “Linguistic Analysis of Neologism Related to Coronavirus (COVID-19).” Social Sciences & Humanities Open 4 (1): 1–6. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssaho.2021.100201.

- Baker, Anne, and Roland Pfau. 2016. “Constituents and Word Classes.” In The Linguistics of Sign Languages, edited by Anne Baker, Beppie van den Bogaerde, Roland Pfau, and Trude Schermer, 93–116. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Barberà, Gemma. 2014. “Use and Functions of Spatial Planes in Catalan Sign Language (LSC) Discourse.” Sign Language Studies 14 (2): 147–174.

- Brentari, Diane, Laura Horton, and Susan Goldin-Meadow. 2020. “Crosslinguistic Similarity and Variation in the Simultaneous Morphology of Sign Languages.” The Linguistic Review 37 (4): 571–608. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/tlr-2020-2055.

- Cecchetto, Carlo. 2017. “The Syntax of Sign Language and Universal Grammar.” In The Oxford Handbook of Universal Grammar, edited by Ian Roberts, 509–526. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cormier, Kearsy, Jordan Fenlon, Sannah Gulamani, and Sandra Smith. 2017. BSL Corpus Annotation Conventions (Version 3.0). London: Deafness Cognition and Language (DCAL) Research Centre, UCL.

- Cormier, Kearsy, David Quinto-Pozos, Zed Sevcikova, and Adam Schembri. 2012. “Lexicalisation and De-lexicalisation Processes in Sign Languages: Comparing Depicting Constructions and Viewpoint Gestures.” Language and Communication 32 (4): 329–348. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.langcom.2012.09.004.

- Dachkovsky, Svetlana, Christina Healy, and Wendy Sandler. 2013. “Visual Intonation in Two Sign Languages.” Phonology 30 (2): 211–252. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0952675713000122.

- ELAN (Version 6.2) [Computer software]. 2021. Nijmegen: Max Planck Institute for Psycholinguistics, The Language Archive. https://archive.mpi.nl/tla/elan.

- Emmorey, Karen. 2002. Language, Cognition, and the Brain: Insights from Sign Language Research. Mahwah: Lawrence Erlaub Associates.

- Gleason, Henry A. 1965. Linguistics and English Grammar. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston.

- Halliday, M. A. K., and Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 1999. Construing Experience through Meaning: A Language-Based Approach to Cognition. London: Cassell.

- Halliday, M. A. K., and Christian M. I. M. Matthiessen. 2014. Halliday’s Introduction to Functional Grammar. 4th ed. Oxford: Routledge.

- Hodge, Gabrielle, and Trevor Johnston. 2014. “Points, Depictions, Gestures and Enactment: Partly Lexical and Non-lexical Signs as Core Elements of Single Clause-like Units in Auslan (Australian Sign Language).” Australian Journal of Linguistics 34 (2): 262–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/07268602.2014.887408.

- Johnston, Trevor. 1996. “Function and Medium in the Forms of Linguistic Expression found in a Sign Language.” In International Review of Sign Linguistics (Vol. 1), edited by W. H. Edmondson and R. B. Wilbur, 57–94. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

- Johnston, Trevor. 2002. “BSL, Auslan and NZSL: Three Signed Languages or One?” In Cross-linguistic Perspectives in Sign Language Research: Selected Papers from TISLR 2000, edited by Anne Baker, Beppie van den Bogaerde, and Onno Crasborn, 47–69. Hamburg: Signum Verlag.

- Lawson, Lilian, Frankie McLean, Rachel O’Neill, and Rob Wilks. 2019. “Recognizing British Sign Language in Scotland.” In The Legal Recognition of Sign Languages, edited by Maartje De Meulder, Joseph J. Murray, and Rachel L. McKee, 67–82. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Martin, J. R., Y. J. Doran, and Giacomo Figueredo. 2020. Systemic Functional Language Description: Making Meaning Matter. London: Routledge.

- Martin, J. R., Y. J. Doran, and Dongbing Zhang. 2021. “Nominal Group Grammar: System and Structure.” WORD 67 (3): 248–280. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.2021.1957545.

- Martin, J. R., Beatriz Quiroz, Pin Wang, and Yongsheng Zhu. In press. Systemic Functional Grammar: Another Step into the Theory – Grammatical Description. Beijing: Higher Education Press.

- Martin, J. R., and Gi-Hyun Shin. 2021. “Korean Nominal Groups: System and Structure.” WORD 67 (3): 387–429. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.2021.1957549.

- Matthiessen, Christian M. I. M, Kazuhiro Teruya, and Marvin Lam. 2010. Key Terms in Systemic Functional Linguistics. London: Continuum.

- Ngo, Thu, Susan Hood, J. R. Martin, Clare Painter, Bradley Smith, and Michele Zappavigna. 2021. Modelling Paralanguage Using Systemic Functional Semiotics. London: Bloomsbury.

- Quiroz, Beatriz. 2018. “Negotiating Interpersonal Meanings: Reasoning about Mood.” Functions of Language 25 (1): 135–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1075/fol.17013.qui.

- Quiroz, Beatriz. 2020. “Experiential Cryptotypes: Reasoning About PROCESS TYPE.” In Systemic Functional Language Description: Making Meaning Matter, edited by J. R. Martin, Y. J. Doran, and Giacomo Figueredo, 102–128. London: Routledge.

- Rudge, Luke A. 2020. “Situating Simultaneity: An Initial Schematization of the Lexicogrammatical Rank Scale of British Sign Language.” WORD 66 (2): 98–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.2020.1751974.

- Rudge, Luke A. 2021. “Interpersonal Grammar of British Sign Language.” In Interpersonal Grammar: Systemic Functional Linguistic Theory and Description, edited by J. R. Martin, Beatriz Quiroz, and Giacomo Figueredo, 227–256. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rudge, Luke A. Forthcoming. Exploring British Sign Language via Systemic Functional Linguistics: A Metafunctional Approach. Bloomsbury Academic.

- Sandler, Wendy, and Diane Lillo-Martin. 2006. Sign Language and Linguistics Universals. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Schermer, Trude. 2016. “Lexicon.” In The Linguistics of Sign Languages, edited by Anne Baker, Beppie van den Bogaerde, Roland Pfau, and Trude Schermer, 173–196. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Stamp, Rose, Adam Schembri, Jordan Fenlon, and Ramas Rentelis. 2015. “Sociolinguistic Variation and Change in British Sign Language Number Signs: Evidence of Leveling?” Sign Language Studies 15 (2): 151–181. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/sls.2015.0001.

- Stamp, Rose, Adam Schembri, Jordan Fenlon, Ramas Rentelis, Bencie Woll, and Kearsy Cormier. 2014. “Lexical Variation and Change in British Sign Language.” PLoS One 9 (4): e94053. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0094053.

- Sutton-Spence, Rachel. 1999. “The Influence of English on British Sign Language.” International Journal of Bilingualism 3 (4): 363–394. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069990030040401.

- Sutton-Spence, Rachel, and Bencie Woll. 1999. The Linguistics of British Sign Language: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Zhang, Dongbing. 2021. “The Nominal Group in Khorchin Mongolian: A Systemic Functional Perspective.” WORD 67 (3): 350–386. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00437956.2021.1957548.

![Figure 12. THREE-MORE [left and middle images] THREE-WEEK [right image].](/cms/asset/6c14d98d-300d-4105-8ad3-b8474b375941/rwrd_a_2024351_f0012_oc.jpg)

![Figure 13. LEVEL+ [1 and 2], DC:RANGE-OF-LEVELS [3 and 4], and LEVEL++ [5 and 6].](/cms/asset/8e0a52c3-efd9-43d9-a39c-3279d0b988db/rwrd_a_2024351_f0013_oc.jpg)

![Figure 14. PT:POSS3SG HOME [left] and TARGET [right].](/cms/asset/2bd0c679-f293-479e-bd3d-dd800f8a03ae/rwrd_a_2024351_f0014_oc.jpg)