ABSTRACT

In the last decade, we have witnessed a second methodological revolution in research into the Trypillia megasites of Ukraine – the largest sites in fourth-millennium BC Europe and possibly the world. However, these methodological advances have not been accompanied by parallel advances in the understanding of the nature and development of the megasites. New data have led to a ‘tipping point’ which leads us to reject the traditional interpretation of megasites as long-term centres permanently occupied by tens of thousands of people.

The contention of the alternative approach is the temporary, short-term dwelling of much smaller populations at megasites such as Nebelivka. In this article, the authors present two alternative models for the gradual emergence of the highly structured plan of the Trypillia megasite.

Introduction

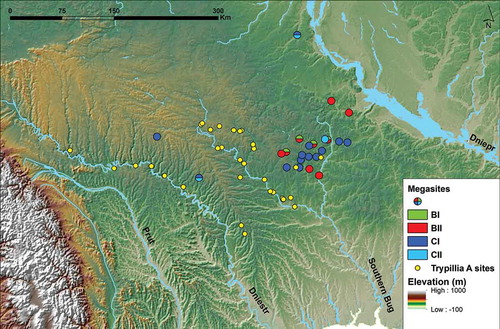

There is a paradox at the heart of the ‘megasite’ phenomenon of the Cucuteni-Trypillia group, which covers 200,000 km2 in Eastern Romania, Moldova and Ukraine () over almost two millennia (4800–2800 BC). On the one hand, the megasites constituted the largest, planned settlements in fourth-millennium BC Europe, with site sizes up to 320 ha and estimated house numbers of almost 3000 on one site (Majdanetske: Müller et al. Citation2016). Their size, distinctive concentric settlement planning and signs of social complexity have reinforced the maximalists’ view of massive, permanent, long-term dwelling, leading some specialists to recognize them as the earliest cities in Eurasia. On the other hand, there is little evidence for the material or social differentiation expected from early cities. The houses fall within a similar size range and there is a paucity of prestige goods of copper, Spondylus or stone. Even more unexpected were the results of recent Anglo-Ukrainian research at Nebelivka, which produced no evidence of settlement hierarchy or the strong human impact on the local forest-steppe environment expected to result from intensive dwelling. In short, there is a mismatch between the interpretation of a permanent, massive, long-term settlement, and the settlement, environmental and material evidence pointing to something smaller and less permanent.

In this article, we confront this paradox of the Trypillia megasites through models of the foundation, development and abandonment of a very different form of megasite – one more in common with assembly places. We should not underestimate the difficulties in such a task; after all, it seems counter-factual to suggest that (a) the largest sites in fourth-millennium BC Europe could be anything but settled on a permanent and long-term basis; (b) the highly developed planning principles found on all of the >200-ha megasites and most of the >100-ha sites betoken anything but a formally created settlement space underpinned by occupation of the whole site; and (c) the complex architecture and finds assemblages of the houses were built for the long-term comfort of families rather than short-term seasonal visits. But the evidential base has shifted, triggering a reinterpretation of the megasites (Chapman Citation2017).

Summary of Trypillia settlement investigations

There are now several accessible accounts of the discovery and investigation of Trypillia megasites (chapters in Menotti and Korvin-Piotrovskiy Citation2012; Chapman et al. Citation2014b: Chapman, Gaydarska, and Hale Citation2016; Kruts Citation2012; chapters in Müller, Rassmann, and Videiko Citation2016a) to complement accounts in Russian or Ukrainian (Videiko Citation2013). Thomas Kuhn (Citation1970) divided the history of science into periods of ‘normal science’ interspersed by conceptual changes which reset the whole field. Following Kuhn, the history of megasite investigations may be divided into three stages of innovation, separated by long periods of ‘normal’ excavation ().

Table 1. The main stages of investigation of Trypillia megasites.

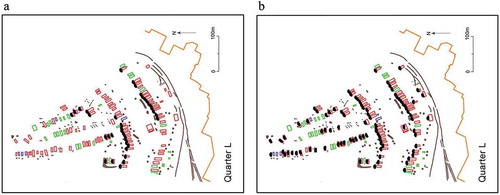

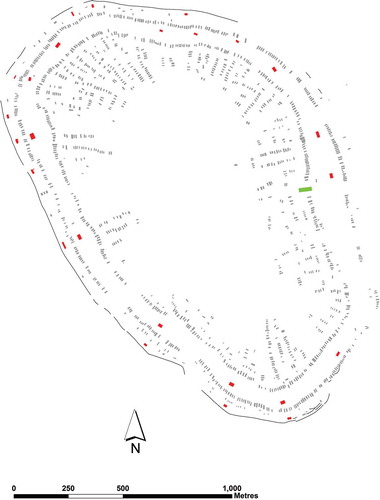

In the first stage, the key discovery was the association of burnt houses with Trypillia pottery. In the first methodological revolution, the discovery of massive sites on aerial photographs led to fieldwork necessary to confirm their Trypillian date. The new style of geophysical investigations was a key element of the second methodological revolution, enabling the only complete plan of a megasite so far (). The complete plan of Nebelivka, and the largely complete plans of Majdanetske and Taljanky, permit the detailed analysis of the constituent parts of the plan, whether groups of houses (‘neighbourhoods’) or groups of neighbourhoods (‘quarters’), in terms of the accordances with, or divergences from, planning principles. It is this advance which has enabled a clearer picture of the growth of a megasite which was simply not possible with the older geophysical plans. The critical re-assessment of the Trypillia settlement pattern also provides the wider regional context for the megasite phenomenon (Nebbia Citation2017).

Figure 2. Digitized plan of the Nebelivka geophysical survey. The main architectural features are displayed: ‘regular houses’ (grey), ‘mega houses’ (red), ‘mega-structure’ (green) and external ditch (black) M. Nebbia.

It should be noted that, as early as the 1990s, a division among Trypillia specialists emerged on the fundamental nature of megasites – urban and comparable to the first cities in the Near East (Videiko Citation1997) or ‘large villages’ that fell far short of urban status (Kruts Citation2003; Korvin-Piotrovskiy Citation2003). This article does not intend to review the huge diversity of views of what megasites constitute but, rather, intends to examine alternatives to the widely held maximalist position. As many as nine different lines of evidence have led us to new understandings of the megasites (Chapman Citation2017; Gaydarska and Chapman Citation2016) ().

Table 2. The tipping point: arguments against the maximalist hypothesis for Trypillia megasites.

Considered individually, these arguments are relatively damaging to the maximalist hypothesis; taken together, they provide a cogent case for considering alternatives to this model (Chapman Citation2017). Before we consider those alternatives, we look at ways in which Nebelivka developed as an assembly place.

Nebelivka as an assembly place

The minimalist view identifies megasites as seasonal agglomeration centres – congregation sites hosting the central summer gatherings of the Trypillia annual calendar, with visitors from many smaller sites. Megasites differ from many of the assembly places presented in this issue insofar as they become massive meeting places with a self-structuring plan, whose quarters and neighbourhoods provided intimate, local identities. What we expect from a superficial study of a megasite plan turns out to be hyperbolic in scale and size: we need to look at the constituent elements more closely. Even though megasites have the appearance of permanence, their core temporality is seasonal, underpinned more by motives of assembly than practices of dwelling, though both were present.

The central component of the models discussed here concerns the relationship between the ‘locals’ and the ‘visitors’. The ‘locals’ consisted of a small permanent population who dwelt at, and maintained, the central site and who contributed their own subsistence labour for out-of-season dwelling. The ‘visitors’ mostly came from up to 100 km from many small settlements, bringing their own pottery, figurines, animals, food and salt, building their own houses and burning them after one or many visits. In time, the ‘visitors’ came to outnumber the ‘locals’ but the success of such an assembly place depended upon the readiness of visitors to merge their own community identities with the identity of the megasite, at least seasonally.

The co-habitation of people who knew each other well from dwelling together and relative ‘strangers’ who had participated in loose settlement networks meant a challenging and by no means frictionless initial social environment, in which commitment to a common identity was crucial to the success of the assembly. A major boost to integration came from the widely shared, pre-existing heritage materialized in three facets of the Trypillia social environment – houses, painted pottery and figurines – which together constitute the Trypillian ‘Big Other’. The Slovenian philosopher Slavoj Žižek has discussed Lacan’s idea of the ‘Big Other’ – something which is sufficiently general and significant to attract the support of most members of society but, at the same time, sufficiently ambiguous to allow the kinds of localized alternative interpretations that avoid constant schismatic behaviour (Žižek Citation2007). The notion is discussed by Sheila Kohring (Citation2012) as a link between the structuring of a group’s symbolic world and its creation of material traditions; it also maps onto Peter Jordan’s (Citation2003) ideas of the ways that community values are etched onto the landscapes by routines of movement, exploitation and consumption and Stephen Gudeman’s (Citation2001) emphasis on the formation of the ‘commons’ as a community value. Even if the objects and structures built at Nebelivka were somewhat different in detail from those in home communities, there would have been a general familiarity with the styles of material culture which could have helped to bridge social gaps between different groups (Chapman and Gaydarska Citation2018).

As important as shared material culture identity was the potential for the emergence of group identities from participation in common tasks performed specifically at the assembly place. The construction of the two principal parts of the megasite – the built-up area and the central empty space – showed the simultaneous construction of two different identities: while the built-up areas were an expression of different communities and social groups coming together, the construction of the empty space in the middle materialized the megasite supra-community identity in a project of unprecedented scale. We propose that the central open space became an important part of the Trypillia Big Other, functioning as a ‘social safety valve’ that facilitated the co-habitation of people occasionally suffering from tensions and discord, even for a limited amount of time (Smith Citation2008, 218). Likewise, Moore (Citation2017, 290) emphasizes the importance of large open spaces for meetings in large oppidum-type settlements in the European Late Iron Age.

Several other practices were identity-forming. Digging the perimeter ditch provided the spatial definition of the entire assemblage community, while the use of communal labour and skills from several families and perhaps different visiting groups formed more local identities through house-building, which included digging large pits for clay. These pits became the foci of shared ritual performances of deposition of quotidian and special objects. Another key Trypillia practice, well known to visitors from their own settlements, was the burning of the dwelling-house at the end of the house cycle ( Johnston Citation2018). The collection of resources for such an event created local bonds, while the performative effects of the burning could be shared more widely with everyone living at that time in the assembly place. Each new ditch segment, house-burning or pit-deposition prompted a re-alignment of social relationships and alliances (Souvatzi Citation2009).

A last ritual practice which gained increasing importance through the life-cycle of the megasite was its emergence as a place with an accumulation of ancestral traces. We estimate that, in 9% of the cases, house-burning left a low but visible mound of burnt debris, whose location became incorporated into mental maps of the megasite and which could be drawn upon in ancestral rituals or memories of past congregation because they were the most obvious visual links to previous dwelling practices (). As the number of house-mounds increased with time, these ceremonies became an increasingly important part of community identity. To what extent did the fame of megasites depend upon the elaboration of such ancestral identities?

Another significant development in megasite research concerns the absolute dating of the three largest megasites – Taljanki, Majdanetske and Nebelivka – which lie relatively close to one another at 25 km and 12 km as the crow flies. The relative chronological insights afforded by pottery typology have hitherto suggested that Nebelivka, with pottery of the early stage of the Nebelivska Phase BII only, was earlier than the other two sites, where only Phase CI pottery of the Tomashivka group was deposited (Müller et al. Citation2016; ). Moreover, the typological model proposed a gap of three stages between the end of Nebelivka and the start of Taljanki, with Majdanetske the latest of the three sites.

Figure 4. Start and end dates for occupation at Nebelivka, Majdenetske and Taljanki (A. R. Millard).

With significant numbers of radiocarbon dates from Nebelivka (n = 81; Millard Citation2018) and Majdanetske (n = 28; Müller et al. [Citation2016]), though fewer from Taljanki (n = 11; Rassamakin and Menotti [Citation2011]), it is now possible to test this pottery chronology using Bayesian modelling.Footnote1 The results show that occupation at Majdanetske started before the end of occupation at Nebelivka (). Occupation at Taljanki probably started before the end of occupation at Nebelivka, and certainly before the end of occupation at Majdanetske. The uncertainties in the radiocarbon dating do not allow us to determine which of the three sites was occupied first. This implies that, at times, two out of the three largest megasites were in coeval occupation, and it is likely that, for a short time, all three were coeval. The implication is that there may well have been a dynamic relationship of competition to attract visitors to three megasites, with groups eventually moving away from Nebelivka to the other sites.

The process of creating a megasite

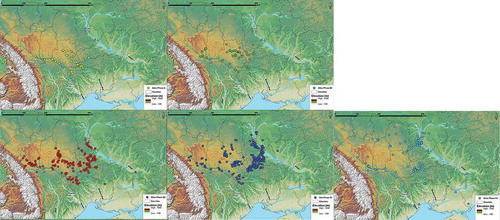

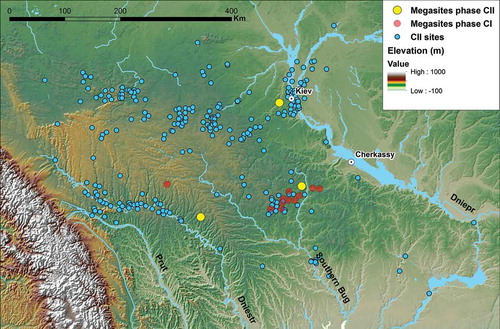

The centre of megasite developments was the Southern Bug-Dniepr (SBD) territory. Knowledge of this region was acquired and transmitted from the initial Phase A of the Trypillia group (). The occupation of the SBD interfluve represented the Eastern ‘frontier’ of the first Trypillian dwellers, whose settlement extended from the foothills of the Carpathian range into predominantly the major river basins (Dniester and Southern Bug). The place-value of that region (Bender Citation2002; Tilley Citation1994; Chapman Citation2012) influenced the creation of massive assembly-places showing a special bond to the SBD landscape. The continuous occupation of that territory for about 1000 years, and the development of the largest sites in Europe at that time, made the SBD interfluve a territory that people recognized and ‘marked’ in order to identify themselves too (Strathern Citation1988). These megasites represented the making of a new identity that was materialized in settlement construction.

The triggers for the origins of megasites remain a topic under consideration (Diachenko Citation2016; Videiko Citation2013; Kruts Citation1989). In a preliminary formulation, we can suggest that the increasing site numbers and sizes in the SBD zone in Phase BII over those of Phase BI created a new dynamic in their social networks because of the growing proportion of settlements reaching the nucleation limits set by relatively inefficient arable practices (set at 35-ha: Shukurov et al. [Citation2015]). This issue triggered two responses, both seeking to establish stronger buffering mechanisms to cope with bad harvests (Halstead and O’Shea Citation1989): a novel emphasis on clusters of sites ()), which enabled closer co-operation and exchange, and a more formal response involving the establishment of assembly places for the development of longer-term exchange relations and closer kinship ties. The increasing level of site clustering occurring across the entire Trypillia zone () began in phase BII, peaking in phase CI.

Figure 5. Hypothetical reconstruction of the first organization of Nebelivka, showing quarters (M. Nebbia).

Elsewhere, we have developed a way of measuring the centrality of Trypillia megasites among the Phase BII settlement system of smaller settlements (Nebbia Citation2017). Looking at different scales of site clustering and at how the size of megasites represented statistical outliers along the dimension of site size, we can argue that these can be construed as social aggregation outliers. People coming from afar assembled for the first time at an unprecedented scale. This distance can be set at ~100 km – the scale at which the megasites sizes were statistical outliers within the distribution of site sizes. For almost 1000 years, this scale represented the distance at which megasites constituted central, special assembly places (Nebbia Citation2017). This meant that they were able to contribute to improved subsistence buffering mechanisms on a broad spatial scale.

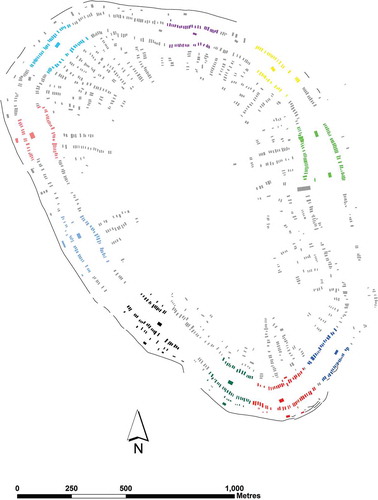

At first sight, the plan of Nebelivka reveals a significant degree of spatial organization (Chapman and Gaydarska Citation2016; Chapman, Gaydarska, and Hale Citation2016). This complex layout will have been predicated upon an initial order that would have embodied the germ of the complete site plan without necessarily predicting the ultimate size and layout of the site. Here we combine this starting assumption of relatively unconstrained growth potential with a model of the social development of the key elements of the plan – the neighbourhoods and quarters. In the past, these units have mostly been associated with the concept of urban settlement (Glass Citation1948; M.E. Smith Citation2010), but, more recently, scholars have started discussing the growth of neighbourhoods in complex but not necessarily urban settlements (M.E. Smith et al. Citation2015). In this sense, we can argue that the development of neighbourhoods is not only a sign of settlement complexity but is also related to the many small village components of the megasite. The reconstruction displayed in represents a possible initial occupation of the megasite of Nebelivka, with its hypothetical settlement plan consistent with the overall final layout of the site.

A dual identity lay at the basis of the social organization that developed on the megasites and which supported their growth and duration for almost a millennium: the pre-existing identities brought onto the megasite by visitors from their own communities and the emergent megasite identity. The differences between community identities and the new megasite identity were probably stronger in the initial phase of megasite formation. Both their negotiation and clarification were important influences on the main trajectories of megasite development.

The wide-ranging social catchment of megasites in the BII phase was probably characterized by a substantial diversity of site groups, which, in earlier times and given the considerable geographical distances separating them, rarely interacted on more than a short-term (daily or weekly) basis. Hence, the close face-to-face interaction occurring at megasites emphasizes those diversities to the point where the emergence of intra-megasite social groupings became highly probable. Whether these differences became problematic is a topic well worth investigating (see below). To a great degree, the house-building programme facilitated the self-organization of the entire site as people naturally interacted with acquaintances (Anthony Citation1997).Footnote2 In this way, community identity was reproduced in the megasite, reinforced or challenged by interactions between different groups. Each community or group of communities reproduced, within negotiated limits, their own settlement practices through the sharing of facilities and resources within neighbourhoods and quarters. In the later CI phase, the greater experience amongst Trypillia populations of visiting megasites coincided with an increasing level of site clustering; the latter stimulated a stronger group identity among villagers who were interacting more closely as well as potentially meeting on megasites such as Taljanki and Majdanetske. We expect this to lead to more differentiated quarters and perhaps neighbourhoods than at Nebelivka.

An initial minimum spacing between groups served as a deterrent for friction and disputes between different visiting groups ( and ). This can then be identified at the level of quarters, that may have represented groups of more closely related visitors within the megasite, as well as by the construction of larger buildings – the assembly houses – resulting in their regular distribution along the perimeter of the megasite. The assembly houses could have represented nodal references and landmarks for the nested development and clustering of neighbourhoods and quarters (). The largest assembly house – the so-called ‘mega-structure’ – was built on one of the main entrances of the megasite. Wust and Barreto (Citation1999, 15) remind us that location as well as monumentality can be an expression of social differentiation. It is proposed that the local group in charge of the organization and coordination of collective activities at Nebelivka built and controlled the mega-structure and lived in the quarter built around the mega-structure.

Overall, the megasite formation process shows a number of different, but interrelated, trajectories towards the development of new identities along with the reinforcement of old ones. The different processes carried both bottom-up and top-down connotations that can be seen at different spatial scales. Top-down processes included a level of social organization within the inter-regional domain, which co-ordinated visits to the mega-site and made general decisions on the planning of the site, including the allocation of specific locations where to build the site (inside the perimeter ditch) and the selection of different places for the establishment of neighbourhoods clustered in quarters. The large empty middle space was collectively incorporated into the design of the whole settlement. Its administration and management could have fostered both social cohesion and discord, especially in the absence of a robust social hierarchy not strong enough to enforce decisions.

Bottom-up processes were equally important and included the acknowledgement of the regional organization by the population, the creation of a new megasite identity by early visiting groups and the local development of neighbourhoods and quarters through self-organization and the sharing of resources for house-building. Typically for complex societies, food, goods and work remained, for the most part, within the local decision-making domain (M.L. Smith Citation2012). In this sense, the household domain or, in the case of megasites, even neighbourhoods, maintained a degree of productive autonomy within the agglomerated dwelling experience of the megasite.

The constant tension between local, bottom-up processes and higher-level, top-down decision-making was a major factor in the way that Nebelivka developed as a differentiated site with much local architectural variability within an overall plan recognizable from all of the other megasites. As the number of visitors grew, this tension would have increased through scalar stress and as a result of increasing differences between locals, small site units with long settlement histories at the megasite and later arrivals. Visiting groups who sought to define themselves as ‘different’ from other groups, although still within the canon of the Big Other, may have created tensions which led to disputes and the abandonment of some households or even neighbourhoods.

Elsewhere in time and space, the overall preference of clusters of small sites in the rest of the Trypillia area of influence (viz., outside the SBD Territory) suggests the development of stronger community group identities rather than a single megasite community one. Here, sites tended to self-organize into groups without massive assembly-places. During phase CII, the time of megasite abandonment was related to a noticeable Northerly shift away from the SBD interfluve (). Remarkably, though, sites still showed agglomeration up to a size of 100 ha, thus showing how community identity transcended the collapse of megasite identities. This can be construed as evidence for the general tendency of Trypillia populations towards a more egalitarian, site-based society rather than a stronger political structure (Diachenko Citation2016a).

Figure 7. Distribution of Trypillia CII sites. The map has been updated with data collected from Manzura (Citation2005) (M. Nebbia).

In summary, this approach proposes a seasonal, dual structure, where egalitarian communities developed a form of supra-community/inter-regional social organization and co-ordination producing, and produced by, collective gatherings in special assemblies at the megasites. The self-organizational nature of this model makes the Trypillia case a plausible example of Chalcolithic heterarchy (Crumley Citation1995; DeMarrais Citation2016; Gaydarska Citation2016). A good analogy would be the continued presence in large central sites (‘oppida’) of what Moore (Citation2017, 294–295) terms ‘rural’ settlement forms built by/for independent extended households whose social power was partly based on their organization of work parties. Additionally, the seasonal component made it a more sustainable organizational structure than a permanent social structure, since the tensions and frictions emerging from a ranked society declined at the end of the collective phase of the calendar. The lack of monumental architecture and the paucity of prestige goods, together with an undeveloped mortuary domain in which to display differences in social status, constitute the main arguments against a permanent, ranked socio-political organization for the Trypillia population. More likely, an inter-regional decision-making political body developed during collective gathering events for the seasonal megasite co-ordination of a generally egalitarian society.

Modelling the annual Nebelivka congregation

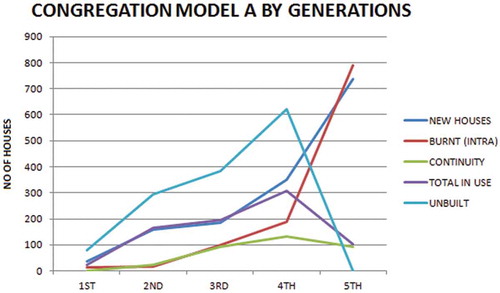

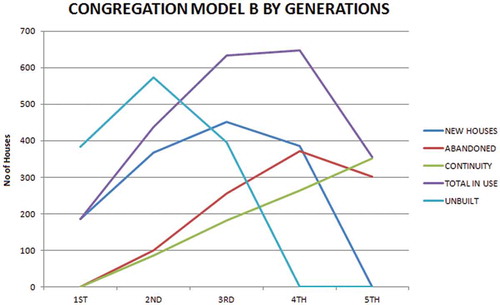

If we can propose a general process of dwelling at Nebelivka linking social practices to settlement plan, can this be operationalized in models of settlement duration and the number of houses built and burnt on the megasite? The parameters of such a model concern the most probable duration of occupation (150 years, here divided into five 30-year generations); the estimated number of quarters (14); the estimated number of neighbourhoods (153); the total number of houses built (1446); and the number of those houses burnt (1078). A key feature of any model was conformity with the results of the Nebelivka Core IB (Albert Citation2018), which showed that there were no massive peaks of deforestation and burning, as proxies for house-building or -burning. Two Models were developed using these parameters.

The variables in Model A consisted of the number of new houses built per generation, the number of houses abandoned in each generation (assuming no abandonments in the first generation), the number of houses which were occupied in the following generation (the continuity index: this was inapplicable in the first-generation settlement of a given Quarter), the total number of houses in use per generation and the number of houses yet to be built in that Quarter.

The rules of this model stipulated that the first occupation consisted of 100–150 people per quarter, living in houses constituting one-third of the total houses in the quarter. In the first generation, the number of houses built equalled the number of houses in use. The fraction of houses showing continuity from an earlier generation was not allowed to fall below c.15% of the total houses in the quarter. This recognized the likelihood of repeat visits of some groups to the congregation. The proportion of houses abandonedFootnote3 was allowed to vary between 10% and 20%. New quarters were settled each generation. For consistency, the trajectory of first-generation quarter K was replicated for second-generation quarter B and third-generation quarter C. Internal growth was limited to 2% per annum but the number of additional houses was usually equalled by the number of houses abandoned in any generation. Thus, increases in the size of the megasite were largely driven by higher visitor numbers. The number of houses occupied over more than one generation and the number of new houses built in any generation was allowed to fluctuate within the given limiting factors.

Running Model AFootnote4 showed a slow to moderate increase in the number of new houses, their abandonment index, the house continuity index and the total number of houses in use from the first to the fourth generation (Supplementary Table 1 and ). In these four generations, the proportion of new houses in each generation rarely rose above one-third of the total houses per quarter; likewise, the abandonment index remained at below 20%, with continuity rising above 20% on only one occasion (fourth-generation quarter K). However, the price for such modest growth, which fitted the human impact profile so well, came in the fifth generation. In these three decades, a high peak in houses built and abandoned is required to account for the total number of houses/burnt houses. In 10 of the 14 quarters, this Model could not account for sufficient new houses for the requisite abandonment index. This slow-growth multi-focal model was thus rejected.

Model B shared many of the parameters of Model A, except that five quarters were initiated in the first generation, five more in the second and four more in the third generation, producing a ‘full’ settlement plan with all areas occupied (Supplementary Table 2 & ). While new houses were built up to the fourth generation, there was no new building in the last generation.

Figure 9. Expansion of the settlement of Quarters, Model B, by 30-year generations: (a) 1st generation (yellow ovals); (b) 2nd generation (green ovals); and (c) 3rd generation (red ovals) (J. Chapman).

In comparison with Model A, the trajectory of Model B () began with a much larger number of houses in four quarters rather than one. With an estimated six people per house, the Nebelivka population grew to over a thousand in 30 years, with c.100 people in 15 houses as permanent ‘guardians’ and the remainder visiting for one month in July or August. The model suggests visitors came to Nebelivka from 30 to 60 small sites.

In the second generation, the building of new houses exceeded abandonment in already settled quarters, with a tenth to a fifth of houses still occupied. This led to a doubling of the number of active houses, implying a population of over 2600 people spread over 10 quarters ( and ). The popularity of the Nebelivka Congregation increased, attracting visitors from perhaps 100 small sites.

The foundation of the final four quarters stimulated a new high in house numbers in the third generation. The highest proportion of new build – over half the houses – was found in the newly settled quarters, with new build much lower in established quarters. However, house abandonment rates exceeded house continuity rates in six quarters.

Although growth rates declined in the fourth generation, this time showed a peak in house numbers at 648 houses, suggesting a total of over 300 permanent ‘guardians’ and almost 3600 visitors. As in the third generation, most of the new build was concentrated in the newly settled quarters. The highest proportions of active houses were also reached in the fourth generation, notably in those quarters founded in the previous generation. However, house abandonment exceeded house continuity in seven quarters, as against the four quarters with higher continuity measures.

In the last generation of the Nebelivka congregation, the absence of new building produced the first fall in the number of active houses. Abandonment rates fell within the range of houses in established quarters in previous generations, while all the houses in use represented continuity from the fourth generation.

Thus, the three major features of Model B comprise a major growth in house numbers from the first to the third generation, a levelling-off in the fourth generation and a steep decline in the last generation. The number of abandoned houses showed an increase from the first to the fourth generation, with a subsequent decline. By contrast, the only index with a continuous increase over all five generations was the continuity index, showing the importance of the built heritage at Nebelivka. This index may be taken as a proxy for the continuity of visitors from the same or related villages over the long term.

How does Model B compare with the key absence of major peaks in human impact? The highest total of newly built houses occurred in the third generation, with 452 houses constructed over 30 years. If the total of 256 abandoned houses, perhaps two-thirds of them burnt, is added to this sum, we reach a total of 708 houses – 452 built, 171 burnt and 85 abandoned and left standing. The annual requirement for timber for building can be estimated at c.190 m3, while c.600 m3 of firewood would have been required to burn the houses (Johnston Citation2018). Kruts (Citation1989) has estimated the timber yield of 1 ha of forest at 300 m3: this annual building and burning implies an estimated forest clearance of less than 3 ha of woodland (cf. Ohlrau et al. Citation2016). Given that these estimates represent the maximum annual build-and-burn timber requirements in Model B, it seems likely that this model would not have produced a major human impact on the Nebelivka environment, which was, however, periodically affected by minor deforestation episodes of the type shown in the pollen diagram (Albert Citation2018).

Thus, Model B shows that it is possible to model the five-generational life of the megasite in a manner fitting all of the Nebelivka parameters – primarily the number of houses built and burnt and the absence of human impact peaks in its 150-year forest history. The weakness of the rejected alternative Model A was the slow incremental growth of new houses, which would have led to an unsubstantiated massive human impact in the fifth generation.

Discussion

Recent reasons for the emergence of megasites have tended to emphasize military/strategic issues of nucleation for defence against other units (Videiko Citation2013; cf. critique: Chapman Citation2017). However, questioning the ‘maximalist’ model opens up the question of the origins of assemblies to new, non-military thinking. While each megasite appears to be a new foundation,Footnote5 they were certainly not based on a tabula rasa, with early settlers bringing both an attachment to and deep knowledge of the SBD region, achieved cumulatively by over a millennium of prior settlement, as well as the communalities of the Trypillia Big Other and a prior history of large settlements in Phases A and BI. The largest Phase BI sites – nucleated small sites of 60 – 120 ha in size and often 10 – 20 km apart – exceeded the subsistence limits of the low-intensity Trypillia agriculture (Shukurov et al. Citation2015), opening up the possibility of seasonal agglomerations enabling a more robust subsistence buffering as well as a variety of social advantages. An alternative to assembly sites in Phase BII was the formation of local settlement clusters, in which close kin relationships maintained an effective form of subsistence buffering (Halstead and O’Shea Citation1989). But the larger assembly places clearly offered social advantages of ever-wider contacts which would have been advantageous in long-distance exchange of salt, Prut-Dniester flint and manganese and graphite for pot-painting.

Two aspects of the emergence of megasites are reminiscent of Igor Kopytoff’s (Citation1987) internal African frontier model – first, the reproduction of assemblies from the bricolage of existing villages, including both mental models of what constitutes a ‘good’ society based upon previous experiences and the material traces of the Big Other; and, secondly, the relationship between first-comers and late-comers. The first residents of a megasite, and their descendants would have maintained their first-comer status throughout the later life of the megasite, with implied differences in status from late-comers. The Nebelivka Model B proposes a mix of 100 locals and 900 visitors over the first generation, with both key spatial forms – the neighbourhood and the quarter – in place. The founding of the five quarters proposed in the first generation would have given an indication of the shape and size of the eventual settlement, as well as an idea of the scope of the inner empty space for the principal communal practices of the assembly.

According to Model B, there was a gradual increase in the number of visitors in the second generation, when the traditional practice of house-burning appeared for the first time at Nebelivka. The communal tasks of house-building and -burning and the digging of the perimeter ditch and the many clay pits showed an expanding commitment to an overarching megasite identity. But this was just one aspect of the dual identity of megasites (the top-down aspect), with the bottom-up aspect of community identities just as important and manifested in the creation of more neighbourhoods, the formation of more quarters and the incorporation of site-based practices into seasonal assemblies. In Nebelivka Model B, minor inter-generational differences in status provided a dynamic for where to build and near which neighbours to build new houses – near first-comers or close to one’s own settlement group.

The peak of new building and house-burning in the third generation required timber and fuel from a relatively small area of 3 ha of mature woodland. These increased rates of house-building would have transformed the megasite, with the appearance of many new neighbourhoods and the expansion of old ones. The consistent continuous rise of the continuity index shows the importance of the building heritage to both locals and visitors. Another transformation of the megasite concerned the slow accretion of memory mounds across the site, marking the location of previous houses and therefore ancestors (). By the later decades of the megasite, perhaps as many as 75 mounds were a visible materialization of the ancestors. Both of these transformations provided a forum for the settling of disputes during the assembly; other ways of handling scalar stress included families moving to remote parts of the megasite and the defusing of tension through dispersal at the end of the festival. Those organizing the assembly still had relatively weak authority, perhaps insufficient to settle serious issues.

In maximalist models, megasites collapsed under the weight of invasions, critical logistical issues or the sustained deterioration to the local landscape. The assembly scenario looks rather different, with Model B proposing a reduction in visitors to 1800 people, no creation of a new quarter and a steep decline in house-building to zero. Three factors may be implicated. The internal factor relates to local challenges to the social order, with a gradually weaker authority losing the capacity to resolve problems. Another factor may have been the weakening of the Trypillia Big Other, clearly exemplified in the expansion of house-building to take over most of the central open space at Majdanetske (Rassmann et al. Citation2016, Fig. 25). The external factor concerns the modelling of the AMS dates from what could transpire to be coeval assemblies at Nebelivka, Majdanetske and Taljanki. The most likely outcome is a competitive domain, where communities abandoned Nebelivka in favour of an alternative assembly. This would rate as an example of a negative feedback loop, in which news of less favourable social relations at Nebelivka were widely transmitted by word of mouth and led to a widespread shift to the other two sites.

The narratives evolving out of the site biography of the Nebelivka assembly provide convergence between three different approaches to the question of megasites – the landscape, the place and the social relations. The social frameworks of those Trypillia communities which provided visitors to the assembly were carried with the visitors into the megasite, to be drawn upon (or not) in the creation of local neighbourhoods and quarters. The tensions between the visitors’ site-based identities and local megasite identities remain as a likely driver for long-term tensions and collapse.

Conclusions

The critique of the maximalist model of Trypillia megasites has prompted different approaches to these extraordinary sites, in which seasonal summer assemblies were the primary motivation for the construction of the megasite of Nebelivka. Although giving the appearance of permanence, megasites were far less totally occupied than in the previous hypothesis. Four principal conclusions may be offered:

(1) A dual-identity form of social organization was most likely at Nebelivka, with the visitors’ local community identities transposed onto neighbourhood identities and a gradual commitment to an independent megasite identity. These twin forms of identity were in tension with each other throughout the duration of the occupation and may well have contributed to its decline.

2. The earliest settlers and visitors brought important elements of their local cultural and natural history to Nebelivka, including a deep knowledge of the South Bug-Dniester landscape, the communal Trypillia Big Other consisting of houses, pottery and figurines, and specific local site traditions which were woven into Nebelivka’s neighbourhood identities.

3. Modelling of the basic parameters of the Nebelivka megasite (duration of occupation, number of houses built and burnt) showed that a scenario with a slow start and a major expansion in the fifth generation (Model A) could not satisfy the megasite parameters, while the second model (Model B) matched the parameters with a trajectory with far more initial visitors and a steep decline in building activity in the fifth generation.

4. The strong probability of coeval occupations at two or even three of the largest megasites (Nebelivka, Taljanki and Majdanetske) is based on the latest AMS Bayesian modelling, raising the likelihood of competition between these assembly places. In concert with internal tensions and potential changes to the Trypillia Big Other, this external competition may well have contributed to the collapse of the Nebelivka megasite.

Supplementary_Materials_Table_4_Model_B.docx

Download MS Word (20.8 KB)Supplementary_data_AMS_Dates.docx

Download MS Word (24.2 KB)Acknowledgements

This chapter could not have been written without the Kyiv-Durham research team of the AHRC-funded project ‘Early Urbanism in Europe?: the Case of the Trypillia Megasites’ (Grant No. AH/I025867/1), and in particular our partners, Drs Mikhail Videiko and Natalia Burdo. We thank the National Geographic Society for their financial support for the mega-structure excavation (Grant No. 2012/211). We are very grateful to the Institute of Archaeology, Kyiv and to Durham University for their support of our excavation and fieldwork at Nebelivka. Our thanks are also due to friends and colleagues who discuss ‘Eurasian urbanism’ with us – in particular, Roland Fletcher and the Hawaii/Tucson ‘Big Sites’ group. We should like to thank the villagers of Nebelivka, especially Mayor Bobko, who welcomed us to their village. Final thanks go to Stoilka Terziiska-Ignatova and the Durham and Kirovograd students who carried out the excavation and fieldwork.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Marco Nebbia

Marco Nebbia is an Postdoctoral Research Assistant at Durham University. His research interests lie in the applications of GIS and remote sensing to landscape archaeology, with a particular focus on the combination of quantitative spatial analyses and social theory for the investigation of early social aggregation processes in Prehistoric Europe. A strand of research that he is currently developing includes comparative approaches to the study of early urbanism origins. He has also been collaborating in capacity building programs in collaboration with the Department of Antiquity of Libya since 2014 designing and delivering GIS training courses.

Bisserka Gaydarska

Bisserka Gaydarska is a Honorary Research Fellow at Durham University. Her research interests are wide-ranging - GIS and Landscape Archaeology, Material culture studies, the Prehistory of Central and South Europe, Interdisciplinary studies, Identity and Early urbanism. Her most recent post-doc projects were ‘Early urbanism in prehistoric Europe?: the case of the Tripillia mega-sites’ and ‘The Times of Their Lives’. The research undertaken within these projects fuelled an interest in matters of scale in archaeology, both in terms of time and space.

Andrew Millard

Andrew Millard is Associate Professor of Archaeology at Durham University. His research focusses on the applications of isotope analysis and Bayesian statistics in archaeology and Quaternary science. He extended the Bayesian paradigm for chronological analysis to dating methods other than radiocarbon. His statistical work on chronological problems has ranged from the dating of a wide range of hominid fossils in Africa to the precise dating of the remains of 17th century Scottish prisoners found in Durham.

John Chapman

John Chapman is an Emeritus Professor of European Prehistory at Durham University. He is one of the leading world specialists on the South East and Eastern European Neolithic and Copper Age. He has co-directed three major projects – the Neothermal Dalmatia Project (Croatia), the Upper Tisza Project (Hungary) – and is currently working with Bisserka Gaydarska on the final publication of the Ukrainian Trypillia mega-sites project. He pioneered recent research into deliberate fragmentation of persons, things and landscapes. He is currently writing a synthesis of the Balkan Mesolithic, Neolithic and Copper Age for the Cambridge World Archaeology series.

Notes

1. For details of Bayesian modelling, see Supplementary Materials.

2. Although here we are discussing seasonal movements rather than migrations, Anthony (Citation1997) stresses the vital role of family or kinship ties during migrations.

3. There were several reasons for the abandonment of a house: (1) internal intra-neighbourhood disputes; (2) protests against freeloaders (viz., households not contributing to common subsistence or ritual requests); (3) a response to a significant death by burning their house; and (4) in the later generations, increased competition between coeval megasites, drawing some of the Nebelivka congregation to Majdanetske and possibly also Taljanki (see above).

4. For full details, see Supplementary Materials.

5. NB: the pollen evidence for pre-Nebelivka agriculture which currently lacks an artefactual signature.

References

- Albert, B. 2018. The Nebelivka 1B sediment core. Section 3.4.1 in J C Chapman, Bisserka Gaydarska, Marco Nebbia, Andrew Millard, Bruce Albert, Duncan Hale, Mark Woolston-Houshold, Stuart Johnston, Edward Caswell, Manuel Arroyo-Kalin, Tuuka Kaikkonen, Joe Roe, Adrian Boyce, Oliver Craig, Dan Miller, Sophia Arbeiter, Natalia Shevchenko, Vitalii Rud, Mikhail Videiko, Konstantin Krementski, GEOINFORM Ukrainii (2018) Trypillia mega-sites of the Ukraine [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597.

- Albert, B. 2018. The Nebelivka 1B sediment core. Trypillia mega-sites of the Ukraine[data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597.

- Anthony, D. W. 1997. “Prehistoric Migration as Social Process.” In Migrations and Invasions in Archaeological Explanation, edited by J. C. Chapman and H. Hamerow, 21–32. Oxford: BAR International Series.

- Bender, B. 2002. “Time and Landscape.” Current Anthropology 43 (S4): S103–12. doi:10.1086/339561.

- Chapman, J. C. 2012. “The Negotiation of Place Value in the Landscape.” In The Construction of Value in the Ancient World, edited by J. K. Papadopoulos and G. Urton, 66–89. Los Angeles: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

- Chapman, J. C. 2017. “The Standard Model, the Maximalists and the Minimalists: New Interpretations of Trypillia.” Journal of World Prehistory 30 (3): 221–237. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9106-7.

- Chapman, J. C., and B. Gaydarska. 2003. “The Provision of Salt to Tripolye Megasites.” In Tripolian Settlements-Giants, edited by O. G. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, V. O. Kruts, and S. M. Ryzhov, 203–210. Kiev: UAS Institute of Archaeology.

- Chapman, J. C., and B. Gaydarska. 2016. “Low-Density Urbanism: The Case of the Trypillia Group of Ukraine.” In Eurasia at the Dawn of History: Urbanization and Social Change, edited by M. Fernández-Götz and D. Krausse, 81–105. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Chapman, J. C., B. Gaydarska, and D. Hale. 2016. “Nebelivka: Assembly Houses, Ditches, and Social Structure.” In Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 117–132. New York & London: Routledge.

- Chapman, J., B. Gaydarska. 2018. “The Cucuteni - Trypillia ‘Big Other’ – Reflections on the Making of Millennial Cultural Traditions.” In Between History and Archaeology - Papers in Honour of Jacek Lech, edited by D. H. Werra and M. Woźny, 267–277. Oxford: Archaeopress Archaeology.

- Chapman, J. C., M. Y. Videiko, B. Gaydarska, N. Burdo, and D. Hale. 2014. “Architectural Differentiation on a Trypillia Megasite: Preliminary Report on the Excavation of a Mega-Structure at Nebelivka, Ukraine.” Journal of Neolithic Archaeology 16: 135–157. doi:10.12766/jna.2014.4.

- Chapman, J. C., M. Y. Videiko, D. Hale, B. Gaydarska, N. Burdo, K. Rassmann, C. Mischka, J. Müller, A. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, and V. Kruts. 2014b. “The Second Phase of the Trypillia Megasite Methodological Revolution: A New Research Agenda.” European Journal of Archaeology 17 (3): 369–406. doi:10.1179/1461957114Y.0000000062.

- Crumley, C. L. 1995. “Heterarchy and the Analysis of Complex Societies.” Archeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 6 (1): 1–5. doi:10.1525/ap3a.1995.6.1.1.

- DeMarrais, E. 2016. “Making Pacts and Cooperative Acts: The Archaeology of Coalition and Consensus.” World Archaeology 48 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1080/00438243.2016.1140591.

- Diachenko, A. 2016. “Demography Reloaded.” In Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 181–193. New York & London: Routledge.

- Diachenko, A. 2016a. “Small Is Beautiful: A Democratic Perspective?” In Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 269–280. New York & London: Routledge.

- Dudkin, V. P. 1978. “Geofizicheskaya Razvedka Krupnih Tripol’skih Poselenii.” In Ispol’zovanie Metodov Estestvennih Nauk V Arheologii, edited by V. F. Genning, 35–45. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

- Ellis, L. 1984. The Cucuteni-Tripolye Culture A Study in Technology and the Origins of Complex Society. Oxford: BAR International Series.

- Gaydarska, B. 2016. “The City Is Dead! Long Live the City!” Norwegian Archaeological Review 49: 40–57. doi:10.3109/17483107.2016.1167260.

- Gaydarska, B., and J. Chapman. 2016. “Nine Questions for Trypillia Megasite Research.” In Studia in Honorem Professoris Boris Borisov, edited by B. D. Borisov, 179–197. Veliko Trnovo: IBIS.

- Glass, R. 1948. The Social Background of A Plan: A Study of Middlesbrough. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Gudeman, S. 2001. The Anthropology of Economy. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Hale, D. 2018. Geophysical prospection. Section 4.2.1 in J C Chapman, Bisserka Gaydarska, Marco Nebbia, Andrew Millard, Bruce Albert, Duncan Hale, Mark Woolston-Houshold, Stuart Johnston, Edward Caswell, Manuel Arroyo-Kalin, Tuuka Kaikkonen, Joe Roe, Adrian Boyce, Oliver Craig, Dan Miller, Sophia Arbeiter, Natalia Shevchenko, Vitalii Rud, Mikhail Videiko, Konstantin Krementski, GEOINFORM Ukrainii (2018) Trypillia mega-sites of the Ukraine [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597.

- Hale, D. N., J. Chapman, M. Videiko, B. Gaydarska, N. Burdo, R. Villis, N. Swann, et al. 2017. “Nebelivka, Ukraine: Geophysical Survey of a Complete Trypillia Megasite”. In AP 2017: 12th International Conference of Archaeological Prospection (12th-16th September 2017, University of Bradford), edited by B. Jennings, C. Gaffney, T. Sparrow, and S. Gaffney, 100–102. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Halstead, P., and J. O’Shea, eds. 1989. Bad Year Economics: Cultural Responses to Risk and Uncertainty. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Johnson, G. A. 1982. “Organizational Structure and Scalar Stress.” In Theory and Explanation in Archaeology, edited by C. Renfrew, M. Rowlands, and B. A. Segraves, 389–421. New York: Academic Press.

- Johnston, S. 2018. Introduction to the experimental programme of house-building and –burning. Section 6.1.1 in J C Chapman, Bisserka Gaydarska, Marco Nebbia, Andrew Millard, Bruce Albert, Duncan Hale, Mark Woolston-Houshold, Stuart Johnston, Edward Caswell, Manuel Arroyo-Kalin, Tuuka Kaikkonen, Joe Roe, Adrian Boyce, Oliver Craig, Dan Miller, Sophia Arbeiter, Natalia Shevchenko, Vitalii Rud, Mikhail Videiko, Konstantin Krementski, GEOINFORM Ukrainii (2018) Trypillia mega-sites of the Ukraine [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597.

- Jordan, P. 2003. Material Culture and Sacred Landscape. The Anthropology of the Siberian Khanty. Walnut Creek, CA: AltaMira Press.

- Khvojka, V. 1901. “The Stone Age of the Middle Dnieper Region.” In Works of the XI Archaeological Convention in Kiev in 1899, edited by C. Uvarova and S. Slitskiy, 736–812. Vol. 1. Moscow: Moscow Archaeological Society Press (in Russian).

- Khvojka, V. 1904. Excavations in 1901 in the Area of the Tripolye Culture. Vol. 5. Russian Archaeological Society Proceedings, 1–20. (in Russian)

- Kohring, S. 2012. “A Scalar Perspective to Social Complexity: Complex Relations and Complex Questions.” In Beyond Elites. Alternatives to Hierarchical Systems in Modelling Social Formations, edited by T. Kienlin and A. Zimmermann, 327–338. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt.

- Kopytoff, I. 1987. “The Internal African Frontier: The Making of African Political Culture.” In The African Frontier: The Reproduction of Traditional African Societies, edited by I. Kopytoff, 10–23. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Korvin-Piotrovskiy, A., R. Hofmann, K. Rassmann, M. Y. Videiko, and L. Brandtstätter. 2016. “Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE.” In Pottery Kilns in Trypillian Settlements. Tracing the Division of Labour and the Social Organization of Copper Age Communities, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 221–252. New York & London: Routledge.

- Korvin-Piotrovskiy, O. G. 2003. “Theoretical Problems of Researches of Settlement-Giants.” In Tripolian Settlements-Giants, edited by O. G. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, V. O. Kruts, and S. M. Ryzhov, 5–7. Kiev: UAS Institute of Archaeology.

- Kruts, V. 1989. “K Istorii Naseleniya Tripolskoj Kultury V Mezhurechje Yuzhnogo Buga I Dnepra.” In Pervobytnaya Archeologiya: Materialy I Issledovaniya, edited by S. S. Berezanskaya, 117–132. Kiev: Naukova Dumka.

- Kruts, V. 1990. “Planirovka Poseleniya U S. Taljanki I Nekotorye Voprosy Tripolskogo Domostroitelstva.” In Ranne Zemledelcheskie Poseleniya-Giganty Tripolskoj Kultury Na Ukraine. Tezisy Dokladov Pervogo Polevogo Seminara, edited by V. G. Zbenovich, 43–47. Taljanki: Institute of Archaeology of the AS of the USSR.

- Kruts, V. 2012. “Giant-Settlements of Trypolye Culture.” In The Tripolye Culture Giant-Settlements in Ukraine: Formation, Development and Decline, edited by F. Menotti and A. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, 70–78. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Kruts, V. O. 2003. “Po Problemi Poselni-Gigantiv Tripilskoi Kulturi V Bugo-Dniprovskom Umezhurechje.” In Tripolian Settlements-Giants, edited by O. G. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, V. O. Kruts, and S. M. Ryzhov, 71–73. Kiev: UAS Institute of Archaeology.

- Kuhn, T. S. 1970. The Structure of Scientific Revolutions. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Manzura, I. 2005. “Steps to the Steppe: Or How the North Pontic Region Was Colonised.” Oxford Journal of Archaeology 24 (4): 313–338. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0092.2005.00239.x.

- Menotti, F., and A. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, eds. 2012. The Tripolye Culture Giant-Settlements in Ukraine: Formation, Development and Decline. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Millard, A. 2018. The AMS dates. Section 4.9.1 in J C Chapman, Bisserka Gaydarska, Marco Nebbia, Andrew Millard, Bruce Albert, Duncan Hale, Mark Woolston-Houshold, Stuart Johnston, Edward Caswell, Manuel Arroyo-Kalin, Tuuka Kaikkonen, Joe Roe, Adrian Boyce, Oliver Craig, Dan Miller, Sophia Arbeiter, Natalia Shevchenko, Vitalii Rud, Mikhail Videiko, Konstantin Krementski, GEOINFORM Ukrainii (2018) Trypillia mega-sites of the Ukraine [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597.

- Millard, A. The AMS dates. Trypillia mega-sites of the Ukraine [data-set]. York: Archaeology Data Service [distributor]. https://doi.org/10.5284/1047597.

- Moore, T. H. 2017. “Alternatives to Urbanism? Reconsidering Oppida and the Urban Question in Late Iron Age Europe.” Journal of World Prehistory 30 (3): 281–300. doi:10.1007/s10963-017-9109-4.

- Müller, J., K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, eds. 2016a. Trypillia-Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE. New York & London: Routledge.

- Müller, J., R. Hofmann, S. L. Brandstätter, R. Ohlrau, and M. Y. Videiko. 2016. “Chronology and Demography: How Many People Lived in a Megasite?” In Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 133–170. New York & London: Routledge.

- Nebbia, M. 2017. Early Cities or Large Villages?: Settlement Dynamics in the Trypillia group, Ukraine. Unpublished PhD Thesis. Durham University.

- Ohlrau, R., M. Dal Corso, W. Kirleis, and J. Müller. 2016. “Living on the Edge? Carrying Capacities of Trypillian Settlements in the Buh-Dnipro Interfluve.” In Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 207–220. New York & London: Routledge.

- Passek, T. S. 1949. “Tripolskoe Poselenie Vladimirovka.” Kratkie Soobshcheniya Instituta Istorii Materialnoj Kultury 26: 47–56.

- Rassamakin, Y., and F. Menotti. 2011. “Chronological Development of the Tripolye Culture Giant-Settlement of Talianki (Ukraine): 14C Dating Vs. Pottery Typology.” Radiocarbon 53: 645–657. doi:10.1017/S0033822200039102.

- Rassmann, K., A. Korvin-Piotrovskiy, M. Y. Videiko, and J. Müller. 2016. “The New Challenge for Site Plans and Geophysics: Revealing the Settlement Structure of Giant Settlements by Means of Geomagnetic Survey.” In Trypillia Megasites and European Prehistory 4100-3400 BCE, edited by J. Müller, K. Rassmann, and M. Y. Videiko, 29–54. New York & London: Routledge.

- Rassmann, K., R. Ohlrau, R. Hofmann, C. Mischka, N. Burdo, M. Y. Videiko, and J. Müller. 2014. “High Precision Tripolye Settlement Plans, Demographic Estimations and Settlement Organization.” Journal of Neolithic Archaeology 16: 96–134. doi:10.12766/jna.2014.3.

- Shmaglij, N. M., and M. Y. Videiko. 1990. “Mikrochornologiya Poseleniya Maidanetskoe.” In Ranne Zemledelcheskie Poseleniya-Giganty Tripolskoj Kultury Na Ukraine. Tezisy Dokladov Pervogo Polevogo Seminara, edited by V. G. Zbenovich, 91–94. Kiev: Institute of Archaeology of the AS of the USSR.

- Shukurov, A., G. Sarson, M. Videiko, K. Henderson, R. Shiel, P. Dolukhanov, and G. Pashkevich. 2015. “Productivity of Premodern Agriculture in the Cucuteni–Trypillia Area.” Human Biology 87 (3): 235–282. doi:10.13110/humanbiology.87.3.0235.

- Smith, M. E. 2010. “The Archaeological Study of Neighborhoods and Districts in Ancient Cities.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 29 (2): 137–154. doi:10.1016/j.jaa.2010.01.001.

- Smith, M. E., A. Engquist, C. Carvajal, K. Johnston-Zimmerman, M. Algara, B. Gilliland, Y. Kuznetsov, and A. Young. 2015. “Neighborhood Formation in Semi-Urban Settlements.” Journal of Urbanism 8 (2): 173–198. doi:10.1080/17549175.2014.896394.

- Smith, M. L. 2008. “Urban Empty Spaces. Contentious Places for Consensus-Building.” Archaeological Dialogues 15 (2): 216. doi:10.1017/S1380203808002687.

- Smith, M. L. 2012. “What It Takes to Get Complex: Food, Goods, and Work as Shared Cultural Ideals from the Beginning of Sedentism.” In The Comparative Archaeology of Complex Societies, edited by M. E. Smith, 44–61. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Souvatzi, S. 2009. “Kinship as Process in Archaeology. Examples from Neolithic Greece.” In Anthropological and archaeological imaginations: past, present and future, edited by T. Sayer. ASA Conference 2009, 4pp.

- Strathern, M. 1988. The Gender of the Gift. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tilley, C. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape. Places, Paths and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- Videiko, M. Y. 1997. “Rozkopky Poselennya Trypilskoi Kultury Bilya S. Vilkhvets.” In Archeologichni Doslidzhennya V Ukraini 1993 Roku, edited by M. Y. Videiko, 26–29. Kiev: Verlag.

- Videiko, M. Y. 2013. Kompleksnoe Izuchenie Krupnykh Poselenij Tripolskoj Kultury V – IV Tys Do N.E. Saarbrücken. Saarbrücken: Lambert Academic Publishing.

- Von Stern, E. 1900. “The Meaning of Ceramic Finds from the South of Russia for the Research of the Cultural History of Black Sea Colonisation.” ZOOID (Berlin) 22: 1–21.

- Wust, I., and C. Barreto. 1999. “The Ring Villages of Central Brazil: A Challenge for Amazonian Archaeology.” Latin American Antiquity 10 (1): 3–23. doi:10.2307/972208.

- Žižek, S. 2007. How to Read Lacan. New York: W. W. Norton.