ABSTRACT

The Francoist repressive strategy unleashed after the coup d’état of 17 July 1936 developed complex mechanisms of physical and psychological punishment. Within Franco’s repressive system there was a specific procedure applied to Republican women. In this article, I provide an analysis of the repression suffered by women during the Spanish Civil War and Franco’s dictatorship in southwest Spain. For that purpose, I draw on stories of female victims, who suffered physical and psychological humiliation, and on mass graves with bodies of women. The research is based on a holistic study of material, oral and written sources from a historical, archaeological and forensic anthropological perspective. It is argued that the different repressive strategies used against the female population by Spanish fascism was motivated by the perception of women as second-class citizens and therefore inferior to men. Their punishment followed criteria of exemplarity.

Introduction

On 17 July 1936 a military uprising against the legitimate government of the Second Republic took place in Spain. The fact that the uprising failed in part of the country prompted the military occupation of the areas that did not support the coup – which developed into a full-fledged civil war that would end on 1 April 1939, with the complete defeat of the Republic (Espinosa Citation2002) and the establishment of the dictatorship of General Francisco Franco, which lasted until his death in 1975. Two main periods have been defined in the study of Franco’s repression. From 17 July 1936 to February 1937, there was a phase in which supporters of the rebellion against the Republic operated through the application of the so-called War Declaration Decrees, which encouraged extrajudicial violence. From February 1937 onwards, emergency summary trials were established that functioned until 1945 (Espinosa Citation2011, Citation2013). Nevertheless, people were still killed by extrajudicial means during this period. This procedure was not limited to the period of the conflict. It also continues during the first years of the dictatorship until 1948 (Espinosa Citation2013). Together with these forms of extreme violence, Francoist repression also resorted to the concealment of the crimes, the destruction of evidence and propaganda (Espinosa Citation2013). The Francoist repressive apparatus not only contemplated the physical elimination of people: it also developed complex mechanisms of psychological punishment which included, from the beginning of the war, the segregation, persecution, harassment and imprisonment of suspects, as well as the seizure of their assets or the application of the Law of Political Responsibilities, among others (Espinosa Citation2002; Casanova Citation2002).

Within Franco´s repressive system there was a specific procedure applied to Republican women (Espinosa Citation2002; González-Ruibal Citation2014). They suffered a specific violence as consequence of their political activity during the Republic or because they were the wives, mothers, sisters or relatives of Republicans (Nash Citation2015; Sánchez Citation2009; Solé Citation2016). The different repressive strategies used against female groups by Spanish fascism were motivated by the perception of women as second-class citizens and therefore inferior to men. According to Francoist ideologues like Juan Antonio Vallejo-Nágera, women intellectually inferior and unreliable and used social revolutions to unleash their sexual appetite and cruelty (Vallejo-Nágera and Martínez Citation1939). The consideration of women as subaltern led to the application of different types of punishment that not always implied death (Solé Citation2016). On the one hand, it could be physical, through the execution, torture and rape of women (Richards Citation1999; Preston Citation2011) first during the war and later in Franco´s prisons (Rodrigo Citation2008). On the other, it could also be psychological, by eliminating aspects of their femininity through the shaving of their hair and their public exposure after having ingested castor oil, which caused them severe diarrhoea – the allegued purpose was to ‘throw communism out of their bodies’ (Richards Citation1999, 58–59). Republican women were caricatured as prostitutes (Gómez Citation2009), due to their efforts to achieve emancipation and equal rights during the Republic and their struggle against patriarchal culture and Catholic morality (Nash Citation2015). After the war, many women that had been left destitute and were marginalized due to their Republican credentials were driven to prostitution (Casanova Citation2002).

In this article, I present an analysis of the repression met by Republican women during the civil war and Franco´s dictatorship in southwest Spain. For that, I draw on the stories of women, who were victims of physical and psychological humiliation, some of whom were eventually killed or made disappear. In some cases, I provide data gathered from mass graves, which contained the bodies of women executed by Francoist supporters. My research is based on a holistic study of mass graves through an interdisciplinary approach, which draws from history, archaeology and forensic anthropology (Muñoz-Encinar Citation2016, Citation2019a; Crossland Citation2000, Citation2009, Citation2013). This combination of disciplines has allowed me to develop a comprehensive analysis of contemporary political violence, that opens new ways for the production of historical knowledge in relation to these contexts (Muñoz-Encinar Citation2016, Citation2019a).

Field of study, materials and methods

My research was conducted in Extremadura, a region located in the southwest of Spain. This region includes two provinces, Cáceres and Badajoz. In the province of Cáceres, the support given to the coup was almost immediate. The population in this area backed the uprising since July 18 (Chaves Citation1997). The province of Badajoz experienced the coup very differently, as it continued to support the Republican government. From the beginning of August, rebels carried out the conquest of government territories. With the advance of rebel troops, many of the central and western parts of the province were occupied. During the autumn of 1936, the lines delimiting the Extremadura Front were established – the Front was significantly reduced in a new offensive in 1938 but remained under Republican control until the end of the civil war in 1939.

According to recent publications, around 14.800 men and women died extrajudicially in the region of Extremadura (Chaves et al. Citation2013). Among these, around 1.600 people died as a consequence of Republican repression. Francoist repression caused over 13.200 victims, including more than 9.200 people executed without a trial. The victims of irregular repression were detained illegally for political reasons and eliminated under the War Declaration Decrees that were in force between July 1936 and 1948. Their track was lost in the repressive process: the bodies of these individuals were buried in mass graves, thrown into riverbeds or buried in mines. According to recent historical investigations the number of women victims of irregular repression was lower than that of men (Martín Citation2015; Chaves Citation1995). In the province of Badajoz, 9% of the victims of irregular repression were women (Martín Citation2015). In the province of Cáceres, the killing of women represents 7% of deaths as a result of the application of War Declaration Decrees (Chaves Citation2012). However, there is an undetermined number of executed women of whom no documentary information exists. The only evidence we have about these cases comes from oral sources. The number of women that were court-martialled was also lower than that of men: 10% of the total of the victims tried in the province of Cáceres were women (Chaves Citation2012), and 5% of the victims in Badajoz (Chaves Rodríguez Citation2015). Women were mostly given prison sentences, and the sentences to death penalty were significantly reduced.

A total number of 45 mass graves have been exhumed in Extremadura between 2003 and 2019 (Muñoz-Encinar Citation2019b). Of these, I have directed the exhumation of 35 graves and analysed the archaeological and anthropological evidence.Footnote1 In these mass graves, a minimum number of 299 individuals have been exhumed, of which 25 women. This number represents 3.2% of the total of victims, according to data published by historians (Martín Citation2015). All mass graves exhumed to date in Extremadura contained the bodies of victims of extrajudicial violence. I classified and analysed mass graves in relation to the context in which the evidence originally generated. For the analysis, I defined four categories of classification considering the context of violence: (a) military occupation of cities and territories by the rebels troops; (b) executions in the rearguard carried out in areas that supported the coup and in areas that were occupied in the wake of the rebel troops; (c) postwar repression associated with concentration camps and prisons; and (d) postwar counter-guerrilla warfare (Muñoz-Encinar Citation2019b, Citation2016). Two of the cases described in this article belong to category (a) and the other two to category (b). For my study, I excavated and analysed the contents of four mass burials, in which I found the remains of 20 women. For categories (c) and (d) I do not have data related to violence against women coming from the exhumation of mass graves. In context (c), I will provide information drawing on oral and documentary sources.

Research on mass graves has been carried out following the methodological and procedural guidelines provided by the protocols for the search for and identification of missing persons in Spain, which recognize the importance of working with different disciplines.Footnote2 I resorted to the methods of forensic anthropology to obtain the biological profile of individuals located in mass graves: the age, sex and size were estimated for all individuals exhumed. As well as outlining a biological profile, I performed an analysis of perimortem violence and studied the post-mortem treatment of the bodies.Footnote3 As for oral sources, I have considered testimonies published by other authors, compiled and provided by other researchers and compiled directly by me during fieldwork. For the interviews, I have used the specific guidelines providing by the ‘Minnesota Protocol’ (United Nations Citation2016) and the Spanish protocol elaborated by Francisco Ferrándiz (Citation2010). Factual distortion, absences and silences, which are sometimes part of the process of mnemonic recollection and remembrance, have been taken into consideration (Assmann Citation2011; Ricoeur Citation2004).

Archaeology allowed me to obtain contextual information on the mass graves and define the cultural profile of each individual and the relationship of the mass grave with other repressive spaces, from a chronological and behavioural perspective. Excavations were carried out following Harris’ stratigraphic method (Citation1991). All archaeological features and the spatial distribution of artefacts and human remains were documented. In the analysis of the mass graves, I considered the location of the deposit, the stratigraphic sequence, the orientation and disposal of the corpses in the grave and the position of their limbs. These data allowed me to explore aspects such as the planning, systematicity and recurrence in the use of mass graves and landscapes by the perpetrators. The bodies found inside mass graves had associated objects that victims carried with them before death, as well as items linked to the acts of violence that they suffered, such as ammunition and other objects associated with the perpetrators. The artefacts that appear next to the bodies are linked to individual identity, as evince by ways of dressing, personal habits and ideology. At the same time, objects symbolize collective identities as represented by social status, occupation and gender. There are elements exclusive to the female gender, including items associated with dress (high-heeled shoes, tie garters, etc.), body adornment (hairpins, earrings), social status and belief (rings, medals). Others, such as a sewing kit, thimbles or pins reflect typical feminine tasks. Their presence and absence allow me not only to describe aspects about their owners but also to provide plausible identifications.

Exhuming violence, revealing faces

Shortly after the coup of 17 July 1936, the rebels started the conquest of government-held territory in the southwest of Spain. The rebel column advanced from Seville towards Madrid through Extremadura. In this campaign, the role played by the colonial Army of Africa, which had been fighting in Morocco for years was very important. The colonial war waged by the occupation units was based on direct, fast and simple actions, and on blind obedience, contempt for life, and the most absolute cruelty (Espinosa Citation2002). According to historian Paul Preston (Citation2011), the use of terror was not spontaneous, as it was explicitly described in the military orders under the euphemism of ‘punishment’. Regular soldiers and legionaries mutilated their victims – cutting off their ears, nose, sexual organs – and also beheaded them. These practices, in combination with the killing of prisoners and the systematic rape of women, were allowed by rebel army officers (Preston Citation2011). The visibility of executions, the exposure of corpses, and the degrading treatment of victims, even after death, had a very strong psychological impact on civilian populations and a great effect on the establishment of a new order by force (Casanova Citation2002).

“Our brave legionaries and regulars have taught the reds what it is to be a man. Incidentally, they have also taught their wives who have finally met real men, and not castrated militiamen. Kicking and howling will not save them … ”Footnote4

When the rebel army arrived in the province of Badajoz it was divided into two columns. The first column was sent towards the town of Mérida and the second departed towards the southeastern village of Llerena. The rebel army encountered strong opposition in Llerena and its occupation on 5 August 1936 was especially violent (Espinosa Citation2003). Later, on August 31, Republican unit tried to recover the city. Although they failed to retake all of Llerena, they managed to temporarily occupy several neighbourhoods, thereby destabilizing the front lines (Espinosa Citation2003). In the following days, the rebels went on to arrest a large number of people in the town. Generally, the walls of the cemetery were chosen as the site for execution. In this case, however, due to the instability of the frontline and its proximity to the cemetery, executions were carried out next to a nearby stream known as the Romanzal (Muñoz and Chaves Citation2014). According to historical data, the number of victims between 5 August and 31 December 1936 was 174 (Martín Citation2015). Twenty-five men and ten women were executed on 2 and 8 September in this area (Muñoz and Chaves Citation2014).

On 2 September 1936 a group of civilians, including several women, were taken to the Romanzal stream at sunrise. After their execution, victims’ bodies were stacked and burned with gasoline, leaving them exposed and uncovered in an unmarked grave. In Mass Grave 1 we exhumed a minimum of nineteen individuals of different ages, including seven men and four women – in eight bodies sex could not be determined. The distribution and orientation of the bodies and limbs shows the random arrangement of the corpses. According to the available testimonies, a priest went to the site with the new authorities in order to give extreme unction to the detainees. For that purpose, he placed a crucifix in front of each of the victims to be kissed. When the priest asked Josefa Fernández Catena, known as ‘La Galla’, to kiss the crucifix, she refused to do so. In response, the priest hit her mouth with the cross and broke her teeth. In the group of civilians executed in the Romanzal stream at least two women were pregnant:

“La Galla” had her teeth broken (…) she was pregnant (…) she said when she was going to be executed: “you will not kill one, you will kill two”Footnote5

“We do not know if the child was born dead or not. They said the child was born dead, but we never found out” Footnote6

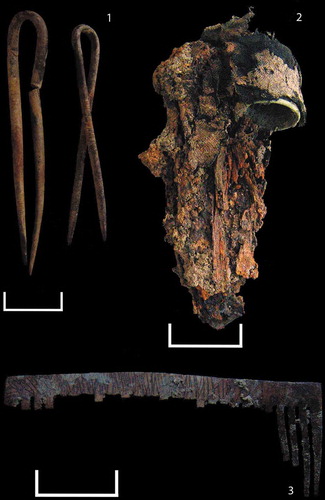

After a few days and with a better knowledge of the area, on 8 September, a second group of victims was buried in the same area. The bodies were laid inside the deposit with the same orientation, in a standardized manner and covered with soil. In this deposit, which we named Mass Grave 2, we documented sixteen individuals of different ages: ten men, five women and one individual whose sex could not be established. Women were buried in the southern part of the deposit and were the last to be placed into the grave. This differentiation of the group of detainees can be related to the degrading perimortem treatment to which female victims were subjected, and with sexual violence commonly exerted during the repressive processes (Richards Citation1999; Preston Citation2011). Among the objects found next to female bodies we documented numerous hairpins, a hair comb, three sewing kits, a thimble and a pin with a religious figure ().

Figure 1. Objects found next to the bodies of female victims buried in the mass graves of the Romanzal stream: 1: Hairpins; 2: Sewing kit; 3: Comb. Scales 2 cm

As happened in Llerena, the main cities of the central and western area of the province were violently occupied during the summer of 1936. During the occupation, mass arrests were immediately conducted. Within these groups of detainees, left-wing supporters were directly eliminated. Other detainees waited for endorsements to guarantee their release. Generally, those who held the most significant roles within the Republican government had fled before the occupation. Nevertheless, as a consequence their relatives were often captured: including many women, daughters, wives or sisters of the fugitives. In addition, their houses were looted by the rebels (Vega Citation2011). On some occasions, the repressive campaign began with a public and exemplary execution in the main square of the village, and after the first field mass (Espinosa Citation2002). This occurred, for instance, in the village of Fregenal de la Sierra, during the second half of September 1936.

Fregenal de la Sierra is located in the southwestern area of the province of Badajoz. During the morning of 18 September 1936, Fregenal was occupied by two military columns formed by 3.000 men (Espinosa Citation2003). According to my research, 82 people were executed between September 1936 and December 1939. At least nine of the victims were women and three of them were pregnant. In most of these cases, there is no documentary information about the executed women, and their deaths were never registered. In some cases, knowledge of surnames has faded in collective memory and only victims’ names or nicknames are remembered. Many women were physically and psychologically harassed, punished to perform tasks for the military forces, shaved and exposed publicly after having ingested castor oil. Oral testimonies tell about the sexual abuse and raping suffered by many women:

“My youngest sister, the girl, they raped her and me and my other sister … they … shaved us (…) they gave me castor oil (…) I suffered a lot (…) because my brother was a socialist (…) they punished the whole family (…) it was the worst punishment”Footnote7

Most of the executions were carried out in the town cemetery, where the gravedigger was responsible for burying the corpses. In this cemetery, we exhumed seven mass graves and documented the bodies of 43 victims, seven of them women. One of the women exhumed was in a state of advanced pregnancy at the moment of the execution. During the excavation, in her pelvis, we documented the skeletal remains of a foetus between 7 and 9 months old. All bodies had been buried following the same procedure, placed in supine position, with alternate orientations, with the lower extremities and upper limbs in parallel. According to oral accounts, there was at least one executed group formed only by women. Nevertheless, in the exhumation campaigns that I led, all mass graves excavated contained the bodies of both, men and women.

“They took up there five or six young women and abused them, after we saw the blood and everything, they transferred the women to the cemetery and buried them but before they abused them. Everybody knew”Footnote8

One of the women was Antonia Regalado Carballar known as ‘la Chata Carrera’. She was 22 years old when she was executed. The denigrating treatment that Antonia suffered before and after death has become part of the traumatic memory of the village, and has been told by multiple testimonies, due to the crude details provided by the gravedigger:

“He placed a man under her, then put [the body of] my aunt on top and [the body of] another man penetrating her above, one below and one above (…)“she is going to be satisfied” (…) he told her enjoying with laughter (…) they made her run around the cemetery and abused her. Then they killed her, and the gravedigger buried her body in this position and said: we have buried her as a whore”Footnote9

In Mass Grave 2 in Fregenal de la Sierra, we documented the bodies of two men and a woman buried overlapping in the supine position. The woman was located between the men´s corpses with the head oriented to the west, the men oriented to the east. She had some buttons related to her clothes and only one tie garter. This woman was between 35 and 40 years age at the moment of death and, as her data do not correspond with Antonia Regalado, this individual remains unidentified.

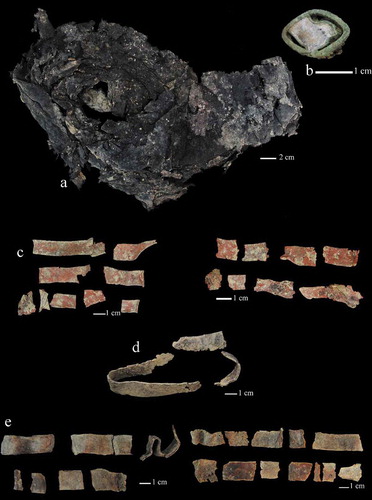

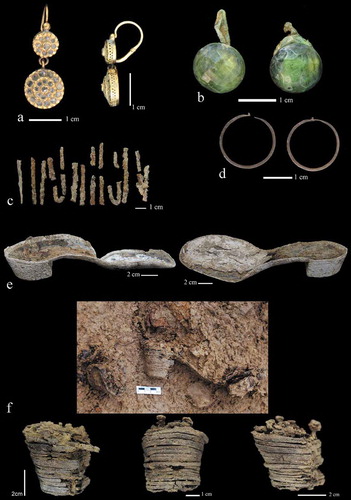

The case of La Chata Carrera or the unknown women described above show that the humiliation of the victims sometimes did not end with death. The dehumanization of the enemy continued in the grave (González-Ruibal Citation2020; Muñoz-Encinar Citation2019a). Women exhumed from the burials of Fregenal de la Sierra wore characteristic elements of clothing: high-heels shoes, garters, mother-of-pearl buttons and cufflinks, among others. One of them even preserved part of a dress. We also found several earrings including a gold earring made of two circles of different sizes with embedded stones forming a floral shape and a pair with carved green stones ( and ).

Figure 2. Objects found next to the bodies of female victims from the mass graves of the cemetery of Fregenal de la Sierra: (a) Sleeve of a dress; (b) Cufflink with the figure of a bird; (c) Tie garters; (d) Tie garter; (e) Tie garters

Figure 3. Objects found next to the bodies of female victims from the mass graves of the cemetery of Fregenal de la Sierra (a) Gold earring; (b) Earrings; (c) Hairpins (d) Earrings (e) high-heeled shoes (f) high-heeled shoes

According to historical and archaeological data, the executions carried out in Fregenal de la Sierra mostly targeted men. Most had been very active inside the political parties and trade unions of the region. Nevertheless, today we know that there were also women executed who had a clear political implication during the Second Republic and had fought for the emancipation of women in all areas of their lives: home, family, work, politics and society. Some of these women, like ‘La Chata Carrera’, were seen as mujeres de bandera (one-of-a-kind women). According to oral testimonies, ‘La Chata Carrera’ used to ride on a horse proclaiming the coming of social revolution and the liberation of women from oppression. Other young women organized themselves to demand improvement of their working conditions and personal situation. Some of them were faithful partners of relevant local political personalities. All these women had seen with their own eyes the changes that the Second Republic had brought to women. Nevertheless, all of them saw their struggle and personal expectations frustrated, along with the fruits of their efforts, buried together with the Second Republic in the mass graves of the cemetery of Fregenal de la Sierra.

While the rebels were occupying the centre and western parts of Extremadura, the northern part of the region expressed its support to the military uprising during the early days of the coup. After the dissolution of the town councils, paramilitary groups such as Falange (the main fascist party in Spain) and the Civil Guard controlled these localities (Chaves Citation1995). The repressive practices developed in these areas are known as paseos or sacas. These practices, which also existed in the rest of Spain, entailed the arrest and execution of a particular selection of individuals or group of civilians who had been involved in left-wing political activities or had showed sympathy for the Republic. In the paseo (literally ‘promenade’), victims were taken from their homes allegedly to declare before the authorities. After their arrest, victims would sometimes remain temporarily in makeshift prisons where they were interrogated, searched, tortured, humiliated, and eventually executed. Sometimes, however, victims were simply taken outside the town or village and executed (Preston Citation2011). The movement of victims from one locality to another to kill them, which sought to make people disappear and instil terror in the population, was also part of the repressive strategy unleashed by the rebels and later in Latin American dictatorships (Funari and Zarankin Citation2006; Preston Citation2011). In this way, families ignored the details of the disappearance of their beloved ones loved, including the execution and the final whereabouts of their corpses. The term sacas (literally ‘extraction’ or ‘withdrawal’) refers to the arrest of people, who were imprisoned and later taken out from jail in groups to be killed. In these repressive practice, women were included due to their political involvement, for having transgressed the traditional female patriarchal model, or for their family ties.

Villasbuenas de Gata is a small town located in the north of the province of Cáceres. This area, like others in Cáceres, manifested its support to the rebels in the early days of the military uprising. In Villasbuenas, four men from the village were executed together with other victims who came from neighbouring towns (Chaves Citation1995). Victims were killed in several places on the side of the roads that led to the town. In one of these areas, called ‘La Charca de la Gitana’, I documented two individual graves where one man and one woman were buried. The woman was Isabel known as ‘La Cubana’ and the man was Justo Roma Salvador, both originally from the near village of Gata. Isabel had been in Cuba, hence her nickname. When she came back to Spain, she had a very good economic position and opened a shop in the village of Gata. She also served as a lender in the area. According to what we know about Isabel, she was a woman with left-wing ideals, married to Marcelo Domínguez Solís. To this day, nobody remembers Isabel’s surname. Her husband was executed later and buried in the cemetery of the village of El Payo (Salamanca). During the excavation, I only found some metal pieces of clothing, a pin and some hairpins used to collect the hair in a bun associated to the body of Isabel. Some testimonies indicate that she was forced to have sex with the other victim before being executedFootnote10 as part of the degrading treatment of victims before death. She was murdered with a shot to the skull.

The repressive practice of paseos or sacas implemented by the rebels in areas that supported the coup d’etat and in the areas of the rearguard reached its height improvement in the so-called places of terror. The repressive procedure will go from being applied individually to constitute a model of mass execution of people. These places were usually located in the outskirts of villages and were used systematically to carry out executions during the civil war (Muñoz and Chaves Citation2014; González-Ruibal Citation2014). The graves exhumed in the place known as ‘Los Arenales’, between the towns of Miajadas and Escurial (Cáceres), correspond to this repressive strategy. According to published data, more than one hundred people were killed in the area (Chaves Citation1995), of which at least 24, including six women, in ‘Los Arenales’. Trucks containing civilians who had been arrested in the surrounding villages were driven to this place during the summer of 1936. They were then murdered and buried in mass graves in the same spot (Muñoz-Encinar and Rodríguez-Hidalgo Citation2010). Aurelia Juárez Gómez and her daughter María Fácila Juárez were among the victims. María was married to Macario Muñoz Gallego,Footnote11 a labourer and well-known leftist in the area. After the coup, Macario fled to the Republican zone fearing possible reprisals. When he escaped, both women were arrested and imprisoned in Miajadas. From there, they were taken to ‘Los Arenales’ in a truck and executed (Olmedo Citation2010b).

In Los Arenales, we located and exhumed two mass graves. They contained seven and nine bodies respectively. A minimum number of seven individuals were recovered in Mass Grave I. During the excavation, we documented a total of nine individuals – six male and three females, all of them adults – in Mass Grave II (Muñoz-Encinar and Rodríguez-Hidalgo Citation2010). In this mass grave, we observed a differential disposal of the bodies in relation to their gender. Males were deposited in the central and eastern sides of the grave and arranged longitudinally with their heads facing east. Instead, females were placed on the west side of the grave and arranged longitudinally and obliquely to the axis of the deposit, with their heads facing west (Muñoz-Encinar and Rodríguez-Hidalgo Citation2010) (). By analysing the sequence of the corpses, it could be observed that these three female individuals were the last to be placed into the grave. The differences in the general pattern of the corpses’ arrangement and ordering in relation to their gender can be interpreted as a way of differentiating the group of detainees by the firing squad. This differentiation can be associated with perimortem practices related to the humiliation of the victims. Two of the women had fractures in the upper limbs resulting from blunt-type trauma. Based on ballistic remains, we can infer that the execution of the victims was carried out in situ by a direct shot with Mausers – the standard rifle with the Spanish Army of the time. Immediately afterwards, they were given the coup de grace with a pistol. Most of the victims did not have many objects associated, maybe because of their low purchasing power or perhaps because they were taken from them during imprisonment. The body of one woman had two gold earrings associated and a silver ring with the initials AM.

Figure 4. Plan of Mass Grave II of ‘Los Arenales’. The grey colour corresponds with the bodies of women

From the last months of 1936 and until the summer of 1938, military activity in the Extremadura Front remained low (Chaves Citation1997). On July 1938, however, a rebel offensive was carried out that caused the loss of most of the territory that the Republicans were still holding in Extremadura. Castuera is a town located in the eastern part of the province of Badajoz. After the military uprising, it remained loyal to the Republic and became the Republican capital of Extremadura until it fell on 23 July 1938. After the military occupation a phase of terror and violence was inaugurated in Castuera similar to that experienced by other localities during the summer of 1936. The first violent actions are marked in the collective memory of the population by the rape and murder of five women. No documentary information exists about them and their names have been forgotten. The systematic detention of all those who had supported the Republic started immediately. Prisoners were confined in several jails based on gender and executions started in the local cemetery and surrounding areas (López Citation2009). We know that mass graves were dug in the cemetery to hide the corpses, but despite our efforts, we have been unable to retrieve them so far (Muñoz-Encinar, Ayán, and López-Rodríguez Citation2013).

One of the first executions carried out in Castuera was that of Carolina Haba García who was married to José Sayabera Miranda. José was a member of the Communist Party and he enrolled in the Republican Army with three of his sons. On 1938 he was advisor to the Provincial Republican Council, and he was also the author of several articles published in the journal Extremadura Roja. The Sayabera-Haba family had nine children and before the imminent occupation of Castuera most of the family fled in a mass evacuation of the civilian population to the Republican zone. Carolina did not have time to flee and remained in Castuera with one of her daughters. After the troops entered the town, Carolina was arrested. From the prison, she was transferred to the cemetery and executed with a group of civilians at the end of July (López Citation2009). After the end of the war, her husband and four other members of her family were also killed.

After the end of the war, another repressive phase started in Castuera. This new phase was characterized by the detention of thousands of Republican soldiers and the imminent return of hundreds of people who had fled to other areas during the armed conflict (Muñoz-Encinar, Ayán, and López-Rodríguez Citation2013). Numerous civilians were arrested when they arrived in town, at the train station. This was the case of Matilde Morillo Sánchez, who was married to Antonio Navas Lora, a member of the Socialist Party and an important political activist. Matilde was a teacher and she was actively involved in the pedagogical commissions that were part of the educational reform carried out during the Second Republic (). She believed in the need to emancipate women through culture and considered education one of the main pillars for the transformation of society:

“We came back in a train of cattle wagons (…) when we arrived to Castuera´s train station there were many Falangists (…) she was identified (…)

It is said that she was raped (…) It is also said that she was taken to the cemetery and the orgy continued in the autopsy room (…) the murderers returned to the village in a truck at dawn. They carried the toweling coat of my mother at the end of a rifle as if it were a flag, as a trophy”Footnote12

Figure 5. Photographs of Matilde Morillo Sánchez in the hands of her daughter Aurora Navas Morillo. Picture taken during the interview held in Castuera in 2011

In Matilde’s case, there is a clear intent to hide her violent fate in the official documentation. This is also the case with many other victims of ‘Franco’s Justice’. In Matilde’s files, there is no information about the moment in which she entered the prison of Castuera or when she left. In 1946, a military judge ordered her release, arguing that he did not find any grounds to prosecute her. However, Matilde had already been executed without a trial seven years before. The concealment of information is also apparent in the document used to register her death. The document shows that it was recorded three years after her execution, with a fake date and a fake cause of death: this was registered as the result of war actions, outside the walls of this town.Footnote13

Those areas of the province of Badajoz that remained under Republican control until the end of the war began to be occupied at the end of March 1939. It is at that time when the town of Puebla de Alcocer is occupied by Franco’s troops and when the detention of the most politically active neighbours began. Prisoners were separated according to their gender in different prisons as well as in a concentration camp, located on the outskirts of the town. According to the results of the exhumations, 42 men were executed and buried in five mass graves during the month of May 1939. The only woman who was killed in the village was María Quiteria. There is no documentary information that informs about the ordeal she went through, not even a record of her death. In Puebla de Alcocer, other thirteen women were arrested and prosecuted on court martials, condemned to different sentences and sent to different prisons around the country (Chaves Rodríguez Citation2015). In addition, a large number of women were shaved and paraded through the streets of the town after being forced to drink castor oil.Footnote14 María was a professional seamstress and embroider. She had been the girlfriend of Eugenio Muga Ruíz, the Republican mayor of the village and president of the local Committee for the Defence of the Republic. They had a daughter who died when she was two years old. After the occupation of the village, María was accused of embroidering the Republican flag, arrested and imprisoned. According to oral testimonies, during the time she was imprisoned, she suffered physical and psychological tortures and several local paramilitaries attempted to rape her.Footnote15 Members of the local paramilitary groups learnt about her possible release, and decided to take her to the local cemetery in order to kill her. When they arrived at the cemetery, military forces refused to shoot Maria Quiteria. It was a paramilitary squad that eventually conducted the execution. There is a persistent memory, now turned into a legend, of this traumatic event in the community. Two years after Maria Quiteria’s killing, her partner, Eugenio Muga Ruíz was court-martialled and accused of adherence to the rebellion (meaning loyalty to the Republic). He was sentenced to death penalty and executed on 9 May 1941.

Conclusions: gender violence in the Spanish Civil War

Women have been victims of all kinds of sexual violence in war at least since Antiquity (Nash and Tavera Citation2003; Lorentzen and Turpin Citation1998). Gendered violence has been studied in multiple scenarios of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries, such a Japan and Germany after the Second World War (Soh Citation2010; Gebhardt Citation2017), the former Yugoslavia (Niarchos Citation1995; Snyder et al. Citation2006), Rwanda (Jones Citation2002), El Salvador, Honduras, Nicaragua, Perú (Anaya Citation2007) and Guatemala (Sanford Citation2000) among others.

In the Spanish case, repression against the civilian population after the coup of July 1936 was not limited to men: numerous women were victims of physical and psychological violence (Nash Citation2015; Sánchez Citation2009; Joly Citation2008; González Citation2017). Documents, military speeches, radio broadcasts, testimonies, and the presence of women in mass graves are witness to the extremely brutal gendered violence in which military and paramilitary rebel forces engaged during the war and after (Espinosa Citation2002; Sánchez Citation2009; Vinyes Citation2002; Solé Citation2016). Oral and documentary data related to gendered violence are consistent with the results from research on the mass graves, which affords new opportunities to examine the specific forms of repression suffered by women during the Spanish Civil War. This multidisciplinary approach – combining oral history, documentary history, archaeology and forensic anthropology – can be relevant in the study of similar conflicts.

In relation to archaeology, material elements associated with the bodies have provided relevant information about the individual and cultural identity of the victims (Muñoz-Encinar Citation2019a). Personal belongings recorded in mass graves include items related to female-related professional activities and identities. Some objects represent the most intimate side of their owners and at the same time their deepest beliefs – as in the case of religious elements. And when we consider all of the objects present in a mass grave together, we can assess the level of homogeneity or difference within the group of victims and propose possible interpretations in relation to their social and political context. From archaeological data, it is also possible to make inferences regarding the way in which repression took place. Thus, in several mass graves, we documented expensive earrings that reveal, on the one hand, the socioeconomic status of their owners and, on the other, the fact that detainees were not thoroughly searched nor their corpses looted. In the case of Fregenal de la Sierra, the bodies of several women found in the mass graves appeared wearing high-heeled shoes, stocking garters, mother-of-pearl buttons, cufflinks and a dress with long sleeves. These elements identify the human remains as actually belonging to women, but they also inform us that the killings did not occur during the summer. Furthermore, the presence of certain objects sheds light on what happened in the past, but their absence can also reveal important information (Muñoz and Chaves Citation2014). For instance, some women in the mass graves of Fregenal had some elements of clothing and jewellery missing: one woman appeared wearing only one stocking garter; another seemed to have lost a gold earring. The absence of these personal belongings is most likely related to the repressive process: they were probably lost during the mistreatment to which women were subjected before being killed, in which sexual abuse was recurrent (Richards Citation1999; Preston Citation2011). As mentioned above, the execution of Republican women had an important symbolic meaning as part of the rebels’ repressive campaign. In this sense, some personal effects, as in the case of Matilde Morillo’s coat in Castuera, might have been removed from the victims and used as a trophy by the perpetrators.

The distribution and orientation of the bodies inside the graves have evinced differences based on gender, which can be related to the degrading perimortem treatment suffered by female victims, and in which sexual violence usually played a prominent role (Richards Citation1999; Preston Citation2011). Women often appear in a specific area of the mass grave and were the last to be buried. The humiliating treatment of the victims often continued after the killing and was part of the dehumanization of the enemy after death (González-Ruibal Citation2020; Muñoz-Encinar Citation2019a). Knowledge about the repressive process can be substantially increased by the analysis of the perimortem violence and the injury patterns observed in the victims.

The presence of several pregnant women murdered in Llerena and Fregenal de la Sierra is especially significant. Similar cases have been transmitted through oral testimonies elsewhere (Rodrigo Citation2008; Espinosa Citation2003; Ferrándiz Citation2014). The case of the pregnant woman exhumed in Fregenal de la Sierra is one of the very few cases documented archaeologically in Spain, as foetal remains are rarely preserved (González-Ruibal Citation2020, 24). The execution of pregnant women is, however, paradigmatic of the contradictions present in Francoist ideology, especially if we consider that it was allowed by the regime, whilst its Nationalist-Catholic ideology was strongly opposed to abortion (Nash Citation2015; Moreno Citation2013; Sánchez Citation2009). The repression of pregnant women did not only occur during the war but also materialized during the dictatorship in Franco’s prisons (Rodrigo Citation2008).

Anti-fascist women were homogenized and stigmatized as Red. They were seen by Franco to embody the moral decline and loss of Catholic values (Nash Citation2015). This specific violence exerted on women’s bodies had a purifying purpose for Franco’s regime and aimed to dehumanize anti-fascist women (Nash Citation2013). For Franco, Red women symbolically represented the Second Republic, together with all the values of what he and his supporters considered the anti-Spain. The concept of Red woman acquired the meaning of no-woman (Sánchez Citation2009), considered by the ideologues of the New Regime, like Vallejo-Nájera, as being inferior, convinced of their innate perversity and natural criminality (Vallejo-Nágera and Martínez Citation1939). The reasons for persecuting women were twofold: on the one hand, they were considered to have transgressed ideal gender values of domesticity and female submission. On the other, they were persecuted for their anti-fascist commitment (Nash Citation2015; Sánchez Sánchez Citation2009). The punishment applied to Republican women did not aim to annihilate them. Rather, it focused on exemplarity and hence its strong symbolic component, materialized in the extreme cruelty that was employed, in the selection of victims and in the treatment of the bodies, alive and dead (Sánchez Citation2009).

In conclusion, women were humiliated and used as a symbol with multiple meanings: ‘Women were considered as a body, a territory where men projected their desires for victory or domination. The materialization of this violent repression made simultaneously visible, in the same gesture, the victory of the winners and the submission of the defeated’ (Sánchez Citation2009, 219). In wars throughout history, as well as in the case of the Spanish Civil War and the Franco dictatorship, women have been used as a weapon and the mistreatment of their bodies has been deployed as a mechanism to terrorize and punish the enemy.

Acknowledgments

The author has benefitted from a postdoctoral fellowship of the General Secretariat of Science, Technology and Innovation from the Government of Extremadura funded by the European Social Fund Operational Program FSE-2014-2020. This article was written while enjoying this postdoctoral fellowship at the Amsterdam School for Heritage Memory and Material Culture of University of Amsterdam. I express my deepest gratitude to Rob van der Laarse and the members of the project Accesing Campscapes: Inclusive Strategies for Using European Conflicted Heritage (HERA 15.092 iC-ACCESS). I thank to Julián Chaves Palacios for his help and support. I also thank Alfredo González-Ruibal for his editorial advice and Zahira Aragüete Toribio for editing the English and for her valuable comments that have improved the original version of the manuscript.

Disclosure Statement

No conflict of interest exists.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Laura Muñoz-Encinar

Laura Muñoz-Encinar holds a PhD in History from the University of Extremadura (2011-2016). Her PhD thesis was awarded with a extraordinary doctoral prize in 2016. She also holds a Master Erasmus Mundus in Quaternary Archaeology and Human Evolution – specialization in Physical Anthropology and Paleopathology – from the University Rovira i Virgili (2006). She is currently a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Amsterdam-Amsterdam School for Heritage Memory and Material Culture and a member of the project Accessing Campscapes: Inclusive Strategies for Using European Conflicted Heritage (iC-ACCESS), funded by Humanities in the European Research Area (HERA) and Horizon 2020 (HERA 15.092 iC-ACCESS). She is a specialist in archaeology of contemporary conflict and forensic anthropology, with a special interest in repression processes conducted in 20th century wars in Spain and Europe. Her research focuses on a holistic study of mass graves through an interdisciplinary approach combining history, archeology and forensic anthropology.

Notes

1. Most of these exhumations have been funded by the regional institutions or the Government of Spain, for more information see Muñoz-Encinar (Citation2016, Citation2019b).

2. In the Presidential Order number PRE/2568/2011, passed on 26 September 2011, the Agreement of the Council of Ministers from 23 September 2011 was published. This agreement demanded that the Boletín Oficial del Estado publish a protocol regarding the carrying out of exhumations of mass graves containing victims of the Spanish Civil War and the dictatorship. BOE 232 of 27 September 2011.

3. For the methodology of estimation of age, sex, stature and perimortem traumas of the exhumed individuals, the interested readers can refer to Muñoz-Encinar (Citation2016).

4. Radio broadcast of the declarations of Lieutenant General Queipo de Llano, cited in Barrios (Citation1978, 205).

5. Testimony of Mary Castilla published in Olmedo (Olmedo Citation2010a, 150).

6. Testimony of Encarna Ruíz published in Olmedo (Olmedo Citation2010a, 148–49).

7. Testimony of Fregenal de la Sierra, anonymized in order to protect the victim. Courtesy of Zahira Aragüete Toribio.

8. Testimony of José Vázquez López, compiled and transcribed by the author.

9. Testimony of Fregenal de la Sierra, anonymized to protect the victim, compiled and transcribed by the author.

10. Testimony of Luis Mariano Martín, compiled by the author.

11. Macario was arrested at the end of the war while he was trying to cross the Pyrenees into France. He was imprisoned for nine years in Orduña and Don Benito.

12. Testimony of Aurora Navas Morillo daughter of Matilde Morillo and Antonio Navas, compiled and transcript by the author.

13. Testimony of Aurora Navas Morillo (compiled and transcript by the author) and Podual File of Matilde Morillo Sánchez: Archive of the Military Government of Madrid. Military Court of the First Military Region.

14. Testimony of Mariano Millán Donoso, courtesy of Zahira Aragüete-Toribio.

15. Testimony of José Sánchez-Paniagua Bayón courtesy of Zahira Aragüete-Toribio.

References

- Anaya, N. 2007. Monitoreo sobre violencia sexual en conflicto armado: Colombia, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua y Perú. Lima: Comité de América Latina y el Caribe para la defensa de los derechos de la mujer.

- Assmann, A., 2011. Cultural Memory and Western Civilization: Functions, Memory, Archives. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Barrios, M. 1978. El último rey. Queipo de Llano. Barcelona: Argos/Vergara.

- Casanova, J. 2002. “Una dictadura de cuarenta años.” In Matar, morir, sobrevivir. La violencia en la dictadura de Franco, edited by J. Casanova, F. Espinosa, C. Mir, and F. Moreno Gómez, 3–50. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Chaves Palacios, J. 1995. La represión en la provincia de Cáceres durante la Guerra Civil (1936–1939). Cáceres: Universidad de Extremadura.

- Chaves Palacios, J. 1997. La Guerra Civil en Extremadura. Operaciones militares (1936–1939). Mérida: Editora regional de Extremadura.

- Chaves Palacios, J. 2012. “Violencia de género y Primer Franquismo: Culturas carcelarias y medidas asistenciales.” In Memoria de Guerra y cultura de paz en el siglo XX. De España a América, debates para una historiografía, edited by F. Prieto and L. Nomes E Voces, 273–293. Gijón: Ediciones Trea.

- Chaves Palacios, J., C. Chaves Rodríguez, C. Ibarra Barroso, J. Martín Bastos, and L. Muñoz Encinar. 2013. Recuperación De La Memoria Histórica En Extremadura: Balance De Una Década (2003–2013). Investigación De La Guerra Civil Y El Franquismo. Zafra: Rayego.

- Chaves Rodríguez, C. 2015. Sentenciados. La represión franquista a través de la justicia militar y los consejos de guerra en la provincia de Badajoz. Badajoz: PREMHEX.

- Crossland, Z. 2000. “Buried Lives.” Archaeological Dialogues 7 (2): 146–159. doi:10.1017/S1380203800001707.

- Crossland, Z. 2009. “Of Clues and Signs: The Dead Body and Its Evidential Traces.” American Anthropologist 111 (1): 69–80. doi:10.1111/aman.2009.111.issue-1.

- Crossland, Z. 2013. “Evidential Regimes of Forensic Archaeology.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 121–137. doi:10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155513.

- Espinosa Maestre, F. 2002. “Julio de 1936. Golpe militar y plan de exterminio.” In Morir, matar, sobrevivir. La violencia en la dictadura de Franco, edited by J. Casanova, F. Espinosa, C. Mir, and F. Moreno Gómez, 51–119. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Espinosa Maestre, F. 2003. La columna de la muerte. El avance del ejército franquista de Sevilla a Badajoz. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Espinosa Maestre, F. 2011. “El contexto de la Memoria. Represión.” In Diccionario de memoria histórica. Conceptos contra el olvido, edited by R. Escudero Alday, 39–45. Madrid: Catarata.

- Espinosa Maestre, F. 2013. “Crímenes Que No Prescriben, 1936–1953.” In Desapariciones forzadas, represión política y crímenes del Franquismo, edited by R. Escudero Alday and C. Pérez González, 31–54. Madrid: Trota.

- Ferrándiz, F., 2010. “Protocolo de entrevistas en exhumaciones de fosas comunes.” http://www.politicasdelamemoria.org/2010/10/protocolo-de-entrevistas-en-exhumaciones-de-fosas-comunes-francisco-ferrandiz-csic-3/

- Ferrándiz, F. 2014. El pasado bajo tierra. Exhumaciones contemporáneas de la Guerra Civil. Madrid: Anthropos.

- Funari, P. P., and A. Zarankin, editors. 2006. Arqueología De La Represión Y La Resistencia En América Latina 1960–1980. Córdoba: Encuentro Grupo Editor.

- Gebhardt, M. 2017. Crimes Unspoken: The Rape of German Women at the End of the Second World War. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gómez Bravo, G. 2009. El exilio interior. Cárcel y represión en la España franquista (1939–1950). Madrid: Taurus.

- González Duro, E. 2017. Las rapadas: El franquismo contra la mujer (Vol. 170). Madrid: Siglo XXI de España Editores.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2014. “Absent Bodies. The Fate of the Vanquished in the Spanish Civil War.” In Bodies in Conflict. Corporeality, Materiality and Transformation, edited by P. Cornish and N. J. Sounders, 169–183. Oxon: Routledge.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2020. The Archaeology of the Spanish Civil War. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Harris, E. C. 1991. Principios De Estratigrafía Arqueológica. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Joly, M. 2008. “Las violencias sexuadas de la guerra civil española: Paradigma para una lectura cultural del conflicto.” Historia social 61: 89–107.

- Jones, A. 2002. “Gender and Genocide in Rwanda.” Journal of Genocide Research 4 (1): 65–94. doi:10.1080/14623520120113900.

- ópez Rodríguez, A. D. 2009. Cruz, Bandera y Caudillo. El campo de concentración de Castuera. Badajoz: CEDER-La Serena.

- Lorentzen, L. A., and J. E. Turpin, ed. 1998. The Women and War Reader. New York: New York University Press.

- Martín Bastos, J. 2015. Badajoz: Tierra quemada. Muertes a causa de la represión franquista 1936–1950. Badajoz: PREMHEX.

- Moreno, M. 2013. “La dictadura franquista y la represión de las mujeres.” In Represión, resistencias, memoria: Las mujeres bajo la dictadura franquista, edited by M. Nash, 1–21. Granada: Comares.

- Muñoz Encinar, L., and J. Chaves Palacios. 2014. “Extremadura: Behind the Material Traces of Franco’s Repression.” Culture & History Digital Journal 3 (2): 1–18. e020. doi:10.3989/chdj.2014.020.

- Muñoz-Encinar, L., and A. J. Rodríguez-Hidalgo. 2010. “Excavación arqueológica de las fosas comunes de Escurial.” In Guerra y Represión. Las Fosas de Escurial y Miajadas, edited by A. Olmedo, 263–294. Mérida: Asamblea de Extremadura.

- Muñoz-Encinar, L., 2016. “De la exhumación de cuerpos al conocimiento histórico. Análisis de la represión irregular franquista a partir de la excavación de fosas comunes en Extremadura (1936–1948)”. Doctoral dissertation, Cáceres: University of Extremadura.

- Muñoz-Encinar, L. 2019a. “De la exhumación de cuerpos al conocimiento histórico. Estudio de la represión franquista a partir del caso extremeño.” Historia Contemporánea 2 (60): 477–508. doi:10.1387/hc.20309.

- Muñoz-Encinar, L. 2019b. “La violencia durante el siglo XX. Búsqueda y exhumación de fosas de víctimas de ejecuciones extrajudiciales en Extremadura.” In Mecanismos De Control Social Y Político En El Primer Franquismo, edited by J. Chaves Palacios, 189–226. Barcelona: Anthropos.

- Muñoz-Encinar, L., X. M. Ayán Vila, and A. D. López-Rodríguez, editors. 2013. De la ocultación de las fosas a las exhumaciones. La represión en el entorno del Campo de Concentración de Castuera. Santiago de Compostela: Incipit-CSIC/AMECADEC.

- Nash, M., ed. 2013. Represión, resistencias, memoria: Las mujeres bajo la dictadura franquista. Granada: Comares.

- Nash, M. 2015. “Vencidas, represaliadas y resistentes: Las mujeres bajo el orden patriarcal franquista.” In 40 años con Franco, edited by J. Casanova, 191–228. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Nash, M., and S. Tavera. 2003. El papel de las mujeres en las guerras de la Edad Antigua a la Contemporánea. Barcelona: Icasa.

- Niarchos, C. N. 1995. “Women, War, and Rape: Challenges Facing the International Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia.” Human Rights Quarterly 17 (4): 649–690. doi:10.1353/hrq.1995.0041.

- Olmedo Alonso, A. 2010a. Llerena 1936. Fuentes Orales Para La Recuperación De La Memoria Histórica. Badajoz: Diputación Provincial.

- Olmedo Alonso, A. 2010b. “Una experiencia de “Historia Viva” en Miajadas y Escurial durante el verano del 2009. Voluntarios para la recuperación de la Memoria Histórica.” In Guerra y Represión. Las Fosas de Escurial y Miajadas. Mérida, edited by A. Olmedo, 155–261. Mérida: Asamblea de Extremadura.

- Preston, P. 2011. El holocausto español. Odio y exterminio en la Guerra Civil y después. Madrid: Debate.

- Richards, M. 1999. Un tiempo de silencio. La guerra civil y la cultura de la represión en la España de Franco, 1936–1945. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Ricoeur, J. 2004. Memory, History, Forgetting. London: The University of Chicago Press.

- Rodrigo, J. 2008. Hasta la raíz: Violencia durante la guerra civil y la dictadura franquista. Madrid: Alianza.

- Sánchez Sánchez, P. 2009. Individuas de dudosa moral. La represión de las mujeres en Andalucía (1936–1959). Barcelona: Crítica.

- Sanford, V. 2000. Informe de la Fundación de Antropología Forense de Guatemala: Cuatro Casos Paradigmáticos Solicitados por La Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico de Guatemala Realizadas en las Comunidades de Panzós, Acuì, Chel y Belén. Guatemala City: FAFG.

- Snyder, C. S., W. J. Gabbard, J. D. May, and N. Zulcic. 2006. “On the Battleground of Women’s Bodies: Mass Rape in Bosnia-Herzegovina.” Affilia 21 (2): 184–195. doi:10.1177/0886109905286017.

- Soh, C. S. 2010. The Comfort Women: Sexual Violence and Postcolonial Memory in Korea and Japan. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Solé, Q. 2016. “Executed Women, Assassinated Women: Gender Repression in the Spanish Civil War and the Violence of the Rebels.” In Legacies of Violence in Contemporary Spain edited by O. Ferrán and L. Hilbink., 87–110. London: Routledge.

- United Nations. 2016. Revision of the UN Manual on the Effective Prevention and Investigation of Extra-legal, Arbitrary and Summary Executions (The Minnesota Protocol). Geneva: United Nations.

- Vallejo-Nágera, A., and E. M. Martínez. 1939. “Psiquismo del fanatismo marxista. Investigaciones psicológicas en marxistas femeninos delincuentes.” Revista Española de Medicina y Cirugía de Guerra 9: 398–413.

- Vega Sombría, S. 2011. La política del miedo. El papel de la represión en el franquismo. Barcelona: Crítica.

- Vinyes, R. 2002. Irredentas. Las presas políticas y sus hijos en las cárceles de Franco. Madrid: Ediciones Temas de Hoy.