Introduction

Archaeologists work with a wealth of mortuary evidence — site-based, artefactual, bioarchaeological and monumental — reflecting the spatial agency of the dead both above and below ground. Necrogeography or the study of ‘deathscapes’, however, relates to a broader spectrum of research that draws on geography, sociology, anthropology, architecture and psychology (Francaviglia Citation1971, 501) and facilitates exploration of the role of place in human mortality (Muzaini Citation2017). Places can be changed by the rituals associated with death and burial, but places in turn can influence human experiences of death. As Michel Serres, Edward Casey, Martin Heidegger, and others who have meditated on this topic suggest, the burial of the dead is an essential human institution, instrumental to both the making of places and the imagining of futures (Serres Citation1987; Casey Citation1997; Heidegger Citation1962). The planning and design of cemeteries, graves and grave monuments, thus offers insight into the socio-cultural and political contexts in which they were generated. Such locales, as archaeologists have prominently argued, are invested with meaning literally by those that have come before, and these meanings can be ‘co-opted’ for identity building, territorial and ideological signalling (Tilley Citation1994; Citation2004). Deathscapes offer a reflection of the living world and its divisions in terms of gender, equality and exclusion — cemeteries and places of burial ‘are susceptible to cultural politics, and they reveal as much about the living as they do about the dead’ (Muzaini Citation2017).

The ‘spatial turn’ within social sciences and humanities has enabled a growing engagement with research on death, memorialization, commemoration and mourning (Maddrell and Sidaway Citation2010). ‘Mourning is an inherently spatial as well as temporal phenomenon’ (Maddrell Citation2010, 123). Within a modern world, we can map the intersections of dying, death, burial and mourning, across public and personal spaces, for example, from the hospital ward to the undertakers, crematoria, cemetery, and even in terms of the domestic space and home (Maddrell and Sidaway Citation2010, 2). The intentional and structured disposal of the dead by humans in places both within living communities and distinct from them (cemeteries) largely sets us apart from other species, and it is these ‘landscapes of disposal’ that can help archaeologists understand the changing notions of connection to place in scalar terms (Wilkinson Citation2003, 65; Bradbury and Philip Citation2017, 87–102).

As archaeologists, our ‘deathscapes’ are, at once, more partial and more confined. We are at the mercy of the frail archaeological record: rarely certain if an excavated cemetery is complete or to what degree the taphonomic and decomposition processes have distorted the evidence. Our retrospective gaze also creates distance between us and mourners at the graveside in the past. Yet archaeological evidence still offers rich opportunities to read mortuary data and necroscapes in terms of social context, identity, power and emotion. Human beings are ‘makers of worlds’, deliberately selecting and choosing places, resources and tools in processes of co-option and construction, resulting not just in physical and built architectures, but enfolding the natural world within tangible and intangible narratives of place and dwelling. The formal disposal of the deceased is claimed by some as an almost ‘a universal practice’ with cemeteries and places of burial deliberately created, serving functional and emotional purposes and simultaneously sacred and profane (Kniffen Citation1967, 426–7). The citation (re-use) of older places of burial and ancient monuments in processes of claiming and mythmaking can enable people to inscribe new geographies of identity. Separate spatial disposal can indicate the alienation of individuals from communities at death, while conversely the dead can also become a potent focus for the living in terms of pilgrimage and veneration. Bodies can be dispersed, fragmented and circulated across countries and continents, or play agent roles in funerary theatre designed to unify people, families and communities. The treatment of the dead is thus intensely culture-specific, but past and present provide ample evidence of the agency of the dead in constructing living notions of space and place. This Special Issue on Necrogeographies was conceived of as a way of broadening archaeological discussion of burial and place at a global level.Footnote1 The articles in this issue demonstrate and collectively explore how, across time and place the funeral, burial and cemetery seem to have provided a discursive terrain for humans in narrating stories of place, connection, identity and belonging as well as otherness. Together, these papers highlight the vital nature of the funeral and the role that the dead and dying played across a wide range of times and contexts.

The living and the dead

Even now, as in the past, human populations are distinctive in the richness of their engagement with the dead. At face value, modern notions of disposal for the dead, centred on large civic cemeteries and crematoria, appear to mark a separation between the activities of the living and places of burial. In many parts of the world, the commoditisation of the funeral has marched alongside the diminution of community and family involvement in the processes of disposal (Shimane Citation2018). Similarly, the popularity of cremation is linked by some to urbanization, the medicalization of death, and broad tendencies towards efficiency, scientific technology and consumer choice (Davies Citation1990; Citation1997), as well as, in parts of the world, a growing human abhorrence of organic decay (Elias Citation1994). Despite these modern tendencies, cemeteries, in many parts of the world, remain active places in the landscape, whether as green spaces for leisure, places for research on family ancestry, or sites of memorials and commemoration. The popularity of ‘Green’ burial practices reflect an interest in making connections between the dead and the natural world (Davies and Rumble Citation2012). Cemeteries such as Forest Lawn (Los Angeles), Père-Lachaise (Paris), Okunoin cemetery (Japan), Panteón Antiquo de Xoxocotlán (Oaxaca, Mexico) or the Old Jewish Cemetery (Prague) are major international tourist sites. The popularization of commemorative shrines at places of national or personal trauma also demonstrate a need for communities to respond collectively to death (Margry and Sánchez-Carretero Citation2011).

Are these modern preoccupations so different from how people behaved in the past? In the archaic hominin landscape of Europe, persistent patterns in burials or places of disposal connected to broader patterning and organization may indicate attempts to use the dead to mark out key nodes in ‘local operational areas’ (Pettitt Citation2015). Paul Pettitt links these behaviours with a cognitive stage in which the dead continued to ‘linger in the [Neanderthal] imagination, fixed at certain points in the landscape and brought to mind when the groups returned to these locales.’ For Pettitt, such acts are equivalent in cognitive terms to the creation of complex art, and demonstrate the ways in which symbolic behaviours can be linked to ‘simple, socially-mediated belief systems’ (Citation2015).

Even the most cursory survey of the literature suggests that necrogeography — the use of the dead to punctuate and mark-out and reinforce taskscapes of the living — has held an integral place in pre-human and human action for thousands of years. This recognition has led many authors to examine the siting and the presence of funerary monuments relative to the world of the living as a way of making inferences about past societies’ attitudes to the dead. Several of the authors contributing to one of the earliest books to explicitly model the archaeology of mortuary behaviour (Brown Citation1971), highlighted location and form of funeral monuments as important proxies for reconstructing past societies. Binford (Citation1971, 21), for example, used the differential placement of burial sites relative to the life spaces of communities as an indicator of the degrees of social ranking in society, while Saxe (Citation1971, 51), in the same volume, explicitly drew a link between the use of funerary monuments to symbolize ancestral rights, and the control of restricted resources.

Saxe’s ideas find expression in a number of the papers contained in this volume, in which the proximity to, visibility over, or connection with, land or other resources, is interpreted within the context of power relations. O’Gorman, Bengtson, and Michael refer to Saxe (Citation1970) and Goldstein (Citation1976; Citation1980; Citation1981), in claiming that ‘interment within a permanent bounded area … reaffirms lineal descent group’s rights to and control over resources’ (O’Gorman, Bengtson, and Michael Citation2020). Such power claims can also be manipulated, as Michel de Certeau suggests, through the deployment of strategies aimed at creating distinctions between places and an exterior ‘Other’, and mastering those places through vision and architecture (Citation1984). Jaffre in this volume argues that single burials were used by mobile communities to demarcate new lands in the steppe (Citation2020), while O’Gorman, Bengtson, and Michael (Citation2020) highlight the significance of burial in the construction of new deathscapes by migrant groups in the North American mid-continent c. 1300–1400 CE. Within the northern British early medieval record, increased burial visibility may relate to particular scenarios or periods of social or environmental precarity (Semple et al. Citationforthcoming). In other cases, the production of power was much more subtle. In the Palaeolithic, a burial event seems to have been used to reaffirm a connection to particularly important locations and features in a taskscape (Pettitt Citation2015) — transforming as de Certeau might suggest, the ‘uncertainties of history into readable spaces’ (Citation1984, 36). Establishing a burial place and repeated visits to it, are also strong modes of reaffirming a group connection to a broader landscape especially within the context of seasonal cycles of mobility (Gonzalez-Ruibal and de Torres Citation2018). All examples show how the disposal of the dead in multiple and various forms can be particularly potent modes of memory making.

While the articles in this volume, by the nature of the topic, focus heavily on burial as a visible act in denoting place and space, it is also worth remembering there were many times in the human past when disposal methods for the dead are not so readily visible to the archaeological eye. In certain times and regions, the dead cannot be traced at all in the archaeological record, despite clear evidence for the presence of living populations (Bradbury and Scarre Citation2017). Adult burials are also hard to identify across much of Iraq and Syria during the 4th millennium BC, the period that saw the initial growth of the first urban settlements (Bradbury and Philip Citation2017, 89–90), although the situation changes in the early 3rd millennium, when well-equipped burials begin to appear. In Iron-Age Britain, for example, formal cemeteries and burials are a relatively rare feature, suggesting that such rites were accessible to just a small section of the population (Armit Citation2017). There is ample evidence as well across time and space for modes of disposal other than the interment of burned or unburned remains (Ibid.). Prehistoric discoveries in Britain suggest the mummification of remains was used as a way of preserving the dead and circulating human remains among the living (Parker-Pearson Citation2017; Brück Citation2017). Exposure may also have been a common practice, with defleshed remains, rather like charnel, collected, commingled and stored in special tombs and monuments (Fowler Citation2004).

In all of these ways the dead can play an active part in geographies of ritual action. On the one hand humans might choose specific places for burning or exposing the dead, but the remains and cremains can then be collected and dispersed, carried with people and redeposited in different places (see for example Thomas Citation2000 on Neolithic Britain). In this context, Eriksen’s paper in this volume reveals the powerful agency of body parts in Viking-Age Scandinavia and how body fragments, in this case heads, might be displayed and circulated, crafted into objects and trophies and ultimately deposited, sometimes in domestic contexts (Citation2020). In western Christian medieval society just a few centuries later, the power of the dead and the grave as intercessors with the divine resulted in religious taskscapes predicated on the placement and display of whole and fragmented dead, from pilgrimage to and ritual performances at shrines, to votive and commemorative acts at shrines and tombs. Human bodies were transformed into venerated objects, fragmented, circulated, concealed and displayed as powerful relics (Klaniczay Citation2014, 217–37).

Citation and mythmaking

Burials and cemeteries are also locations that can provide connections between the real and supernatural worlds and carry ancestral resonance. Cemeteries and individual burials are themselves a form of physical citation in the landscape. Individual funerals might be rendered memorable as a performance, but their role in cumulative commemoration came by the fact that the same place was selected and new graves were placed in relation to still-visible existing monuments (Williams Citation2006: 55–65, 158–62; Semple and Williams Citation2015, 4–6). The buried dead became participants in each new funeral and the cumulative assemblage of graves became an attestation of community, lineage and linkage to place. In this volume, the role of individual acts of burial for place-making is powerfully attested in Bronze-Age north-eastern China in connection with the expansion of mobile pastoralism (Jaffe Citation2020). Jaffe argues that the revisitation of ancestral landscapes and burials can transform a cemetery into an important location for the living. In this way the dead of the Upper Xiajiadian culture were operationalized — by placing them in the pasture lands, the living became active participants in ancestral claims to the steppe (Ibid.). In Viking-Age Norway, Moen also re-envisages the cemetery as a place of collective effort and shared experience. As active places — locales for funerary performances, but also perhaps locations for feasting and assemblies — cemeteries were places that maintained and reinforced social memory. They were visible and accessible, and their layouts strongly support the idea that they developed a ‘cumulative architecture’ indicative of the relationships of distinct families or groups within the burying community (Moen Citation2020). To take an example beyond this volume, in Somaliland, it is argued that burials and cemeteries acted as locational anchors for seasonal and mobile populations with repeat visits serving to reinforce memory and social connection (Gonzalez-Ruibal and de Torres Citation2018). These three geographically and temporally distant examples demonstrate the potency of burial as citational tool that could be used to physically describe narratives of belonging and connection.

While many studies have sought to examine the locational preferences of funerary monuments, from the perspective both of their regional landscape and micro-topographical settings, few have questioned the underlying propositions of Binford and Saxe that necrogeographies are essentially about claims to resource and competition. These articles and others in this volume more strongly underline the notion of burial activity as a form of extended ritual performance in the landscape, in which acts of burial inscribed or reinscribed a connection to place. We might, therefore, see these acts, as some scholars have argued for the grave-side funerary performance, as a kind of myth-making process. The deliberately created and highly organized landscape of a cemetery may have a ‘spatial logic’ that echoes the idealized notions of connection in a locality or region, while the use of burials and cemeteries to punctuate the broader landscape, and repeated visits to those places, serve to reinscribe notions of, or even aspirations to, belonging and group relationships (see Francaviglia Citation1971, 501; Moen Citation2020).

In architectural terms, such associations might be enhanced through the citation (re-use) or the quotation (copying) of older places of burial and ancient monuments. Monuments to the dead in this way serve in part to enhance the image of places, drawing on a mental template of memory so as to trigger sets of interpretations and understandings for those encountering places: about continuity, memory, descent or possession (Rowlands Citation1993, 141; Williams Citation1998). In some cases, the transmission of these ideas may preserve long-held associations. In other cases, such as the re-use of older places of burial and ancient monuments, they can enable people to inscribe new geographies of identity. Keith Basso has argued that place making — connecting events and stories to places — is a way of ‘doing human history’ (Citation1996, 7). Both the cumulative creation of cemetery sites and their establishment within the broader natural and human altered landscape should therefore perhaps be envisaged as activities with story-making and narrative qualities that represent ways of creating connections to place and real and imagined histories.

Memory and monumentality

Among the more physically tangible aspects of necrogeographies recoverable archaeologically are the architectures of commemoration — whether as earthen mounds, stone edifices, monuments, tombs, or other structures. Such architecture can be understood to simultaneously mediate relationships between the past and contemporary societies, while also creating spaces saturated with historical meanings. In attempting to recover these meanings archaeologists often draw on the techniques of architectural analysis to identify the language and conventions of commemorative structures. Elements of design, planning, style, association and the materiality of monuments are commonly described as a means of identifying the relationships the living had with their dead. All these dimensions cannot always be recovered, but some essential aspects — among them, prominence, siting, alignment, scale — offer ways to explore how these monuments were encountered and the likely reactions they aroused from viewers.

The prominence or visibility of certain types of burial has long been interpreted in the context of social organization. Shepherd’s much cited work from the 1970s has long been influential in arguments for large burial mounds being representative of elite status and emerging competition between ruling families (Shephard Citation1979; van der Noort Citation1993; Carver Citation2001). The proximity of burials to boundaries has been argued as well as a way in which communities signalled their distinctiveness and structured their locality and territories. In all these works, where and how people buried their dead reflects in some ways the cosmology, social practices and sense of belonging central to people’s understandings of the world. Such ideas have been promoted via phenomenological theories and methods (e.g. Bradley Citation1998; Tilley Citation1994), others have made use of spatial statistical techniques, enabled by Geographical Information Systems (GIS), to quantify these kinds of monumental spatial relationships (e.g. Wheatley Citation1995; Wheatley and Gillings Citation2002; van Leusen Citation2004). Such studies often draw attention to other aspects of basic architectural design — notably the alignment of sites relative to routes of movement or settlement, or the locational preferences of burial sites on elevations or slopes so as to be sky-lit (Cummings and Whittle Citation2003, 256; Brookes Citation2007). Effort is given to understanding how monuments were encountered and formed part of people’s social perception of space.

However, moving beyond merely measuring size and prominence has proved as difficult as advancing on notions of competition and identity. In this volume authors have worked hard to capture a more nuanced sense of the sensory engagement with the geographies of the dead. Along the Murray River in Australia in the 19th century, Littleton and Allen, vividly reconstruct the variety of aboriginal mortuary practices for disposing of and commemorating the dead. They powerfully record how, in this case, the western gaze can misinterpret mortuary evidence, fitting it into preconceived notions of barbarity and warfare (Littleton and Allen Citation2020). Here the diversity of signalling may well have represented the importance of junctions and intersections in the landscape as places of cultural and social interactions, rather than contestation. Sensory and physical engagement with the place of burial is shown as an immediate and longer-term activity, necessary to re-establishing the social order and, presumably, a beneficial and safe relationship between the living and the dead. Monumental variety is also matched by Littleton and Allen against linguistic groupings — grave monuments are conceived of as an equivalent kind of grammar, marking distinctions and intermingling’s in language and socio-cultural practice. In a very different context, Femke Lippok in relation to bi-ritual cemeteries in early medieval mainland Europe, demonstrates how the archaeological evidence for the use of cremations tells a very different story from more traditional readings which frame the practice as a reaction to and incompatible with Christianity (Lippok Citation2020). Lippok demonstrates instead that cremation represented an alternative but contemporary choice which existed in congruence with, rather than in opposition to, inhumation practices and row-grave cemeteries.

The material agency of funerary monuments — the properties of these structures to affect people — emerges in the articles in this volume from close readings of the palimpsests of structure, style, decoration, and materiality. While many of the symbols and signs employed in these palimpsests are specific to given cultures at different times in the past, examining how they might have been used to evoke certain reactions is an important element in understanding necrogeographies. Among the essential considerations of all structural design are aspects like the interactions of solid and void, the proportions and shape of physical monuments, their colour and permeability to light and movement, the texture and materials from which edifices are made, and the sequencing of construction. As ‘makers of worlds’ the deliberate selection and choosing of places, resources and tools by communities, in processes of co-option and construction, resulted not only in the creation of physical and built architectures, but encoded the natural world within tangible and intangible narratives of place and belonging. In this context, Alaica, González La Rosa, and Knudson’s exploration of the use of human offerings at Huaca Colorada in the Jequetepeque Valley, Peru, demonstrates how the physical remains of the dead and the process of building were integral to empowering places. The pyramidal mound constructed in the Late Moche period provided a focus for seasonal activities and ceremonies that brought together culturally and regionally differentiated populations (Alaica, González La Rosa, and Knudson Citation2020). Human sacrificial burials were made at distinct junctures in time and place at Huaca Colorada. Bioarchaeological evidence reveals that sacrificed individuals represented different communities of practice — craftspeople, herders, etc. — allowing these communities to participate in the ritual creation and maintenance of the sacred space in the complex. These individuals were thus fixed both in time and place to points in the lifecycle of the pyramid, reinforcing notions, stories and memories of collective ownership: ‘readable spaces’ in de Certeau’s sense.

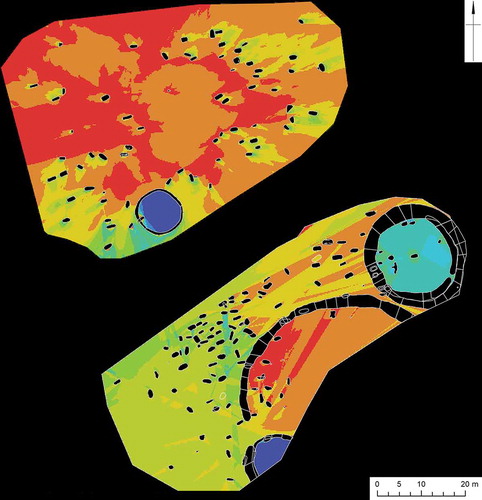

From this perspective then, space syntax methods, such as Isovist Analysis or Visibility Graph Analysis (VGA), are notable tools that enable exploration of the spatial environment and visibility within burial sites. Returning to northern Britain as an example, VGA analysis of the early medieval burial complex of West Heslerton, Yorkshire, reveals how prehistoric features were used to channel and control movement and visibility through the cemetery (). These monuments also seem to have structured the sequencing of burial events and how these were organized, structured and perhaps framed and encountered (Haughton, Powlesland, and Blades Citation1999; Brookes et al. Citationforthcoming; Semple et al. Citationforthcoming). Such spatial properties within the necroscape can in turn be compared with bioarchaeological information from the skeleton (e.g. sex, age, mortality) and cultural information in the form of grave goods. In this example, the citation of prehistoric monuments is argued to have been carefully orchestrated to reflect aspects of the deceased’s social persona (Brookes et al. Citationforthcoming; Semple et al. Citationforthcoming). Pairs of mostly female burials were arranged to the southwest of the hengiform enclosure to create an avenue leading to the northern portion of the cemetery. Several graves cluster around the entrance to the hengiform enclosure in ways that might be suggestive of guiding and ‘guarding’ movement into the burial site, while early medieval burial mounds, constructed to a similar scale as the pre-existing prehistoric barrows, represent the burials of high-status males and unaccompanied women. In these and other ways, the spatial ordering, diversity and complexity of the necrogeography can be suggested as an important aspect of memory and identity formation processes, with spaces and social structures forged in relationship to one another within this extended necropolis.

Figure 1. Visual entropy plot of the early medieval cemetery of West Heslerton, showing (in online colour version only) the most ‘open’ areas in red to most constrained in blue. A large open area in the north of the site is likely to represent the location of an early medieval barrow raised over the high-status male (grave 52) in potential imitation of the three Bronze Age barrows in the centre, far south and east of the cemetery. These also provide a focus for early medieval burial. Burials within the large hengiform enclosure are physically segregated from other graves, and it may be significant that several of the cremation burials from the cemetery are located here. Analysis and diagrammatic representation by Stuart Brookes and Brian Buchanan based on data published in Haughton, Powlesland, and Blades (Citation1999) (Brookes et al. Citationforthcoming).

Returning to this issue, in a number of cases the evidence suggests the use of a cemetery by successive generations of relatively small communities engaged in varied and flexible means of disposal in different areas. In the central cremation cemeteries of early medieval eastern England the place of disposal was regularly visited by the living: the varied spatial distribution of burials on the site perhaps reflecting the ordering of communities and families in surrounding settlements, with structured burial used to reaffirm the broader collective bonds of the territory (Perry Citation2020). These examples remind us that while the spatial dimensions and the materiality of burial sites can often be recovered from the archaeological record and explored as indicators of social, cultural and symbolic behaviour in their own right, movement into, in and around burial sites is also discoverable and significant. It offers insight into how access might be controlled, channelled, constrained or connected and linked to some of the ways people chose to express connections, divisions, and segregations between themselves and the dead. Approaches that emphasize the experience and encountering of spaces have great potential to explore such spatial and cultural relations and enhance our understanding of the emotional and sensory aspects of burial performance.

Bodily agency

A far more literal expression of necrogeography is the physical use of human remains to create spaces. In late medieval western Brittany, a mix of popular belief and Catholicism generated a mental world in which the community of the dead — the collective society of the souls of the departed — were contiguous with the world of the living (Jupp and Howard Citation1997). In an increasingly formalized use of religious space, churchyards were enclosed with monumental entrances and burial in the church and churchyard intensified which in turn resulted in elaborate ossuaries to house the dispersed bones of the dead in dignity — evidence of a continuing community responsibility to the assembled communal dead (Musgrave Citation1997, 70–1). The display of bones, the creation of structures from human remains, and the physical melding of dead bodies and buildings, are powerful ways in which dead can be consciously reused by the living, providing evidence of the agency of the dead human body in constructing living notions of space and place. In this issue, at the prehistoric Xagħra Circle hypogeum in Malta, excavations have revealed the disarticulated and commingled remains of nearly 800 individuals (Thompson et al. Citation2020). The funerary assemblage appears symptomatic of regular visits by the living to intervene with the remains of the dead and redistribute the skeletal remains to reshape the mortuary. Alaica et al. also underline the agency of human sacrificial acts and interments in the development and repair of a ritual complex at Huaca Colorada, Peru (Citation2020). In even more intimate structural settings, the mortuary cults of the neo-Assyrian period in Mesopotamia demanded the presence of the dead within the household space. Creamer reveals how burials were positioned within the footprint of the house to ensure the dead could be actively engaged with and cared for within the domus (Citation2020).

These articles confirm that bodies, whole and fragmented, are repeatedly used by humans in powerful commemorative ways and can have mnemonic architectural and landscape impacts. The circulation and veneration of human body fragments is evident in numerous and diverse ways in Africa in past and present. From the drying, dispersal and handling of body parts and bones, to the curation of heads and skulls, human remains were consistently used in ritual action to make material statements regarding relationships between the living and the ancestral dead involving memory, commemoration and veneration (see Insoll Citation2015, 78–114). In some instances, however, human remains might operate within rituals enacted at a much broader geographic scale. In Ancient India, stūpas, monuments commemorating the relics of the Buddha, but only sometimes associated with relic deposits and these perhaps of senior monks and saints, seem to have been used within local Buddhist geography to mark out a larger ‘world map’ signalling Buddhist custodianship and authority over natural and cultivated landscapes and resources (Shaw Citation2016, 382–403). Returning to a later time and to western Europe, the monks of Lindisfarne, a monastic community in north-east England, purportedly travelled with the remains of St. Cuthbert, moving from place to place for 12 years, before arriving at Chester-le-Street, and eventually, Durham. By the 11th century CE, the various stopping places served to structure a maximal spiritual landscape — a network of potent places of sanctity that structured ecclesiastical power in the north (Bonner, Rollason, and Stancliffe Citation1989; Stancliffe Citation1989, 44).

Bodies and body parts can also be used, conversely, to alienate and ‘other’ individuals from the communities of the living and the dead. Within early medieval England, the execution of the living and the disposal of their bodies, by the 10th and 11th centuries CE, was undertaken with a distinct geographic architecture. Places of judicial killing and burial were on administrative boundaries, often using older burial mounds and ‘heathen’ locations. Disposal was cursory and bodies and body parts were displayed (Reynolds Citation2009) and each act of execution and display reinforced a landscape of royal authority and control that drew its inspiration from locality, popular belief and biblical allegory and signalled elite power through the exclusion of individuals from normative burial rites (Semple 2019 [Citation2013], 193–223). Indeed, the archaeological record provides multiple instances of the ways in which burial rites can be used to segregate and marginalize individuals and groups. These necrogeographies of exclusion might include the use of liminal natural places for disposal of special categories of individuals, evident in the discoveries of late Iron-Age victims like Tollund Man in the wetlands and bogs of northern Europe (see Glob 1998 [Citation1969]), or the continued tradition of excluding suicides from burial in consecrated ground in medieval, early modern and even more recent times (Gittings Citation1984, 76–77; Korpiola and Lahtinen Citation2015, 1–31). Understanding the differential treatment of the dead is thus relevant to achieving insights into the inequalities of the past and present, in how the poor, physically impaired, enslaved, dissidents and criminals were treated and alienated by society (Hadley Citation2010; Renshaw and Powers Citation2016; Bradbury and Philip Citation2017). Exceptional and brutal treatments of the corpse, however, can sometimes become more spectacle than deterrent. ‘Hanging in chains’ or the use of the gibbet was a spectacular post-mortem punishment used in Britain under the Murder Act of 1752–1821 (Tarlow and Battell Lowman Citation2018). Only the dead were ‘hung in chains’ with the criminal body allowed to decay slowly in a metal cage with pieces falling bit by bit to the ground to be scavenged or carried off (Ibid.). The locations chosen for the display of the body were usually informed by the crime and provided a regular attraction for visitors over the months following display, attracting a mass of people, with the gibbet serving as a focus for public entertainment as well as serving to remind people of the power of the state (ibid.).

In these examples, the dead body is revealed as powerful and agent in both positive and negative ways and of value to communities and authorities. These are important paradigms in which to consider the evidence of the distant and recent undocumented pasts. The treatment of the dead is not always undertaken with positive intentions. In Huaca Colorada, the giving up of women and children by communities for sacrifice and burial underlines how people and powers may assert authority over the bodies of others — both the living and dead (Alaica, González La Rosa, and Knudson Citation2020).

Concluding thoughts

This Editorial has been written at the height of the Coronavirus pandemic. In this context, given the theme of this issue, it is hard not to reflect on scenes in media from around the world of the preparation of mass graves, of individuals dying alone, and funerals taking place with attendance restricted to just a few family mourners. We are all living through a significant disruption to our normal ways of dealing with death.

Yet, as both philosophical and archaeological discourses suggest, how and where we bury our dead, how we remember them, and what we pass on to future generations are essential qualities of being human. The forging of senses of belonging and place using the formalized deposition of the dead has been compared in terms of a step-change in cognitive advancement to the development of art and aesthetics in pre- and early hominins (Pettitt Citation2015). The articles in this volume reinforce the notion that necrogeographic action is present in many different times and places in the human past, and that necroscapes are essential components in how people and communities embed their everyday practices in the landscape. In this moment we should perhaps consider that the removal of the ability to invest in normative practices of individual burial and group mourning is representative of profound pressures and ruptures to everyday life and reflect on this as a lesson for reframing our interpretations of the necrogeographies of the past. There are long periods of time in different parts of the world where visible disposal methods are scant or absent (Bradbury and Scarre Citation2017). We also see significant step changes in mortuary visibility in many different geographic and temporal spheres. Rather than focusing on the old adages of status, competition, identity and display, we are able, as the articles in this issue reveal, to set out more emotionally intuitive frameworks for interpretation that recognize collective ways of dealing with and caring for the dead rather than competitive concerns. We need as well to reflect on inequalities of access to mortuary rites, along with the potential for others to exert control over the living and the dead in terms of funerary rites and disposal. The dead do not bury themselves, but the living do not always engage with funerary rites in positive ways alone: as we have seen there are necrographies of exclusion, equally as powerful as necroscapes created to forge communal senses of connection. It is worth remembering that the dead provide significant performative capital for those in authority, be it in the current counting of numbers of the dead, or in their use in past and present as a means of empowerment and legitimation for regimes.

Geographies of death and burial, whether empirically interrogated through GIS or explored in more phenomenological sensory methods, are thus central to understanding human behaviours past and present in relation to understanding the fabric of existence in social, political and religious terms. They reflect something intensely human about the moments in which setting down claims, roots and connections involved co-opting the dead in place- and story-making. Ultimately by ‘reading’ the necrogeographies of the past we will achieve a deeper understanding of the sense of self, place and being, carried by the generations that preceded us and something of the ways in which communal efforts in the disposal of the dead can create stronger bonds and connections in the living.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the two anonymous reviewers and Professor Graham Philip for their helpful comments on the draft version of this editorial.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Sarah Semple

Sarah Semple is Head of Archaeology at Durham University where she teaches and researches on the landscapes and material culture of early medieval Britain and Northern Europe. She is the author of Perceptions of the Prehistoric in Anglo-Saxon England (2019) and a co-author of Negotiating the North: Meeting-Places in the Middle Ages in the North Sea Zone (2020).

Stuart Brookes

Stuart Brookes is Senior Research Associate and Teaching Fellow at the UCL Institute of Archaeology. His research interests include comparative landscape studies and the archaeology of state formation in early medieval Europe. He has published various works on the archaeology of early medieval Europe, including Polity and Neighbourhood in Early Medieval Europe (ed. with J. Escalona and O. Vésteinsson, Brepols, 2019) and Landscapes of Defence in the Viking Age (ed. with J. Baker and A. Reynolds, Brepols, 2013).

Notes

1. The idea for the issue was prompted by work by the authors on the Leverhulme-funded project People and Place: the Making of the Kingdom of Northumbria which uses the extensive burial record for 300 to 800 CE in northern Britain to explore political processes, power and social identity. A project conference, Grave Concerns: Death, Landscape and Locality in Medieval Society, jointly organized with the Society for Medieval Archaeology in 2018, broadened the scope for this special issue.

References

- Alaica, A. K., M. González La Rosa, and K. J. Knudson. 2020. “Creating a Body-subject in the Late Moche Period (CE 650–850). Bioarchaeological and Biogeochemical Analyses of Human Offerings from Huaca Colorada, Jequetepeque Valley, Peru.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1743205.

- Armit, I. 2017. “The Visible Dead: Ethnographic Perspectives on the Curation, Display and Circulation of Human Remains in Iron Age Britain.” In Engaging with the Dead: Exploring Changing Human Beliefs about Death, Mortality and the Human Body, edited by J. Bradbury and C. Scarre, 163–173. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Basso, K. 1996. Wisdom Sits in Places. Landscape and Language among the Western Apache. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press.

- Binford, L. R. 1971. “Mortuary Practices: Their Study and Their Potential.” In Approaches to the Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices, edited by J. A. Brown, 6–29. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology. vol. 25. Washington D.C: Society for American Archaeology.

- Bonner, G., D. Rollason, and C. Stancliffe, eds. 1989. St Cuthbert, His Cult and His Community to AD 1200, Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Bradbury, J., and C. Scarre. 2017. “Introduction: Engaging with the Dead.” In Engaging with the Dead: Exploring Changing Human Beliefs about Death, Mortality and the Human Body, edited by J. Bradbury and C. Scarre, 1–6. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Bradbury, J., and G. Philip. 2017. “Shifting Identities: The Human Corpse and Treatment of the Dead in the Levantine Bronze Age.” In Engaging with the Dead: Exploring Changing Human Beliefs about Death, Mortality and the Human Body, edited by J. Bradbury and C. Scarre, 87–106. Oxford: Oxbow Books .

- Bradley, R. 1998. The Significance of Monuments: On the Shaping of Human Experience in Neolithic and Bronze Age Europe. London: Routledge

- Brookes, S., 2007. “Walking with Anglo-Saxons: Landscapes of the Living and Landscapes of the Dead in Early Anglo-Saxon Kent.” In Anglo-Saxon Studies in Archaeology and History, edited by S. Semple and H. Williams, Vol.14, 143–153. Oxford: Oxford Committee for Archaeology.

- Brookes, S., B. Buchanan, S. Harrington, and S. Semple. forthcoming. Placing the Dead: Necroscapes in Early Medieval Britain.

- Brown, J. A., eds.. 1971. Approaches to the Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology. vol. 25. Washington D.C: Society for American Archaeology.

- Brück, J. 2017. “Reanimating the Dead: The Circulation of Human Bone in the British Later Bronze Age.” In Engaging with the Dead: Exploring Changing Human Beliefs about Death, Mortality and the Human Body, edited by J. Bradbury and C. Scarre, 138–148. Oxford: Oxbow Books .

- Carver, M. O. H. 2001. “Why That? Why There? Why Then? The Politics of Early Medieval Monumentality.” In Image and Power in the Archaeology of Early Medieval Britain: Essays in Honour of Rosemary Cramp, edited by H. Hamerow, 1–22. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Casey, E. S. 1997. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical Enquiry. Berkley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Creamer, P. M. 2020. “As above so down Below: Location and Memory within the Neo-Assyrian Mortuary Cult.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1745091.

- Cummings, V., and A. Whittle, 2003. “Tombs with a View: Landscape, Monuments and Trees.” Antiquity 77: 255–266. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00092255.

- Davies, D., and H. Rumble, 2012. Natural Burial: Traditional-Secular Spiritualities and Funeral Innovation. London: Continuum.

- Davies, D. J. 1990. Cremation Today and Tomorrow. Nottingham, England: Alcuin/GROW Books.

- Davies, D. J. 1997. “Theologies of Disposal.” In Interpreting Death: Christian Theology and Pastoral Practice, edited by P. C. Jupp and T. Rogers, 67–84. London: Cassell.

- de Certaeu, M. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Berkley: University of California Press.

- Elias, N. 1994. The Civilizing Process. In Sociogenetic and Pyschogenetic Investigations edited by E. Dunning, J. Goudsblom and S. Mennell, translated by E. Jephcott. Oxford: Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Eriksen, M. H. 2020. “Body-objects’ and Personhood in the Iron and Viking Ages: Processing, Curating, and Depositing Skulls in Domestic Space.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1741439.

- Fowler, C. 2004. “In Touch with the Past? Bodies, Monuments and the Sacred in the Manx Neolithic.” In The Neolithic of the Irish Sea: Materiality and Traditions of Practice, edited by V. Cummings and C. Fowler, 91–102. Oxford, UK: Oxbow Books.

- Francaviglia, R. V. 1971. “The Cemetery as an Evolving Cultural Landscape.” Annals of the Association of American Geographers 61 (3): 501–509. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1971.tb00802.x.

- Gittings, C. 1984. Death, Burial and the Individual in Early Modern England, London/Sydney: Croom Helm.

- Glob, P. V. 1998 [1969]. The Bog People. London, Faber and Faber.

- Goldstein, L. G. 1976. “Spatial Structure and Social Organization: Regional Manifestations of Mississippian Society.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Department of Anthropology, Northwestern University, Evanston, Illinois.

- Goldstein, L. G. 1980. “Mississippian Mortuary Practices: A Case Study of Two Cemeteries in the Lower Illinois Valley.” Scientific Papers, 4. Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Archeological Program.

- Goldstein, L. G. 1981. “One Dimensional Archaeology and Multidimensional People: Spatial Organization and Mortuary Analysis.” In The Archaeology of Death, edited by R. Chapman, I. Kinnes, and K. Randsborg, 53–69. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gonzalez-Ruibal, A., and J. de Torres. 2018. “The Fair and the Sanctuary: Gathering Places in a Nomadic Landscape (Somaliland, 1000-1850 AD).” World Archaeology 50 (1): 23–40. doi:10.1080/00438243.2018.1489735.

- Hadley, D. M. 2010. “Burying the Socially and Physically Distinctive in Later Anglo-Saxon England.” In Burial in Later Anglo-Saxon England C. 650-1100 AD, edited by J. Buckberry and A. Cherryson, 103–115. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Haughton, C., D. Powlesland, and N. Blades. 1999. West Heslerton: The Anglian Cemetery. Yeddingham, North Yorkshire: Landscape Research Centre.

- Heidegger, M. 1962. Being and Time. Translated by John Macquarrie and Edward Robinson. New York: Harper & Row.

- Insoll, T. 2015. Material Explorations in African Archaeology. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jaffe, Y. Y. 2020. “A Grave Matter: Linking Pastoral Economies and Identities in the Upper Xiajiadian Culture (1200-600 BCE), China.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1741437.

- Jupp, P. C., and G. Howard, eds. 1997. The Changing Face of Death. Historical Accounts of Death and Disposal. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- Klaniczay, G. 2014. “Using Saints: Intercession, Healing, Sanctity.” In The Oxford Handbook of Medieval Christianity, edited by J. H. Arnold, 217–237. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kniffen, G. 1967. “North America. In ‘Geographical Record’.” Geographical Review 57 (3): 426–437.

- Korpiola, M., and A. Lahtinen. 2015. “Cultures of Death and Dying in Medieval and Early Modern Europe: An Introduction.” In Cultures of Death and Dying in Medieval and Early Modern Europe, edited by M. Korpiola and A. Lahtinen, 1–31. Helsinki: Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies.

- Lippok, F. E. 2020. “The Pyre and the Grave: Early Medieval Cremation Burials in the Netherlands, the German Rhineland and Belgium.” World Archaeology 52: 1.

- Littleton, J., and H. Allen 2020. “Monumental Landscapes and the Agency of the Dead along the Murray River, Australia.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1740106.

- Maddrell, A. and J. D. Sidaway. 2010. “Introduction: Bringing a Spatial Lens to Death, Dying, Mourning and Remembrance.” In Deathscapes. Spaces for Death, Dying, Mourning and Remembrance, edited by A. Maddrell and J. D. Sidaway, 1–16. Farnham: Ashgate.

- Maddrell, A. 2010. “Memory, Mourning and Landscape in the Scottish Mountains: Discourses of Wilderness, Gender and Entitlement in Online Debates on Mountainside Memorials.” In Memory Mourning and Landscape, edited by E. Anderson, A. Maddrell, K. McLoughlin, and A. M. Vincent, Vol. 71, 123–145. At the Interface/Probing the Boundaries. Leiden: Brill.

- Margry, P. J., and C. Sánchez-Carretero, eds. 2011. Grassroots Memorials: The Politics of Memorializing Traumatic Death. New York and Oxford: Berghahn.

- Moen, M. 2020. “Familiarity Breeds Remembrance: On the Reiterative Power of Cemeteries.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1736137.

- Musgrave, E. 1997. “Memento Mori: The Function and Meaning of Breton Ossuaries 1450-1750.” In The Changing Face of Death. Historical Accounts of Death and Disposal, edited by P. C. Jupp and G. Howarth, 62–75. Basingstoke: Macmillan Press.

- Muzaini, H. 2017. “Necrogeography.” In International Encyclopedia of Geography, edited by D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A Kobayashi, W Liu, and R. A. Marston. New York: John Wiley & Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0117.

- O’Gorman, J., J. D. Bengtson, and A. R. Michael. 2020. “Ancient History and New Beginnings: Necrogeography and Migration in the North American Midcontinent.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1736138.

- Parker-Pearson, M. 2017. “Dead and (Un)buried: Reconstructing Attitudes to Death in Long-term Perspective.” In Engaging with the Dead: Exploring Changing Human Beliefs about Death, Mortality and the Human Body, edited by J. Bradbury and C. Scarre, 129–137. Oxford: Oxbow Books .

- Perry, G. J. 2020. “Ceramic Hinterlands: Establishing the Catchment Areas of Early Anglo-Saxon Cremation Cemeteries.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1741438.

- Pettitt, P. 2015. “Landscapes of the Dead: The Evolution of Human Mortuary Activity from Body to Place in Palaeolithic Europe.” In Settlement, Society and Cognition in Human Evolution: Landscapes in Mind, edited by F. Coward, R. Hosfield, M. Pope, and E. Wenban-Smith, 258–274. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Renshaw, L. and N. Powers. 2016. “The Archaeology of Post-Medieval Death and Burial.” Post-Medieval Archaeology 50 (1): 159–177. doi:10.1080/00794236.2016.1169491.

- Reynolds, A. J. 2009. Anglo-Saxon Deviant Burial Customs. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rowlands, M. 1993. “The Role of Memory in the Transmission of Culture.” World Archaeology 25: 141–151. doi:10.1080/00438243.1993.9980234.

- Saxe, A. A. 1970. “Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices.” Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

- Saxe, A. A. 1971. “Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices in a Mesolithic Population from Wadi Halfa, Sudan.” In Approaches to the Social Dimensions of Mortuary Practices, edited by J. A. Brown, 39–57. Memoirs of the Society for American Archaeology. vol. 25. Washington D.C: Society for American Archaeology.

- Semple, S. J., and H. Williams. 2015. “Landmarks of the Dead: Exploring Anglo-Saxon Mortuary Geographies.” In The Material Culture of the Built Environment in the Anglo-Saxon World II, edited by M. Clegg Hyer and G. Owen Crocker, 137–161. Liverpool University Press.

- Semple, S. J. 2019 [2013]. Perceptions of the Prehistoric in Anglo-Saxon England. Ritual, Religion and Rulership. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Semple, S. J., S. Harrington, S. Brookes, R. Gowland, and L. Walters. Forthcoming. People and Place AD 300–800. The Making of the Kingdom of Northumbria.

- Serres, M. 1987. Statues: Le Livre des fondations. Paris: François Bourdin.

- Shaw, J. 2016. “Buddhist and Non-Buddhist Mortuary Traditions in Ancient India: Stūpas, Relics, and the Archaeological Landscape.” In Death Rituals, Social Order and the Archaeology of Immortality in the Ancient World, edited by C. Renfew, M. Boyd, and I. Morley, 382–403. Cambridge: Cambridge Books Online.

- Shephard, J., 1979. “The Social Identity of the Individual in Isolated Barrows and Barrow Cemeteries in Anglo-Saxon England.” In Space, Hierarchy and Society. Interdisciplinary Studies in Social Area Analysist, edited by B. C. Bamham and J. Kingsbury, 47–79. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Shimane, K. 2018. “Social Bonds with the Dead: How Funerals Transformed in the Twentieth and Twenty-first Centuries.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 373 (1474): 20170274. doi:10.1098/rstb.2017.0274.

- Stancliffe, C. 1989. “Cuthbert and the Polarity between Pastor and Solitary.” In St Cuthbert, His Cult and His Community to AD 1200, edited by G. Bonner, D. Rollason, and C. Stancliffe, 21–44. Woodbridge: Boydell Press.

- Tarlow, S. and E. Battell Lowman. 2018. “Harnessing the Power of the Criminal Corpse.” Palgrave Historical Studies in the Criminal Corpse and its Afterlife.

- Thomas, J. 2000. “Death, Identity and the Body in Neolithic Britain.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 6 (4): 653–668. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.00038.

- Thompson, J. E., E. W. Parkinson, T. Rowan McLaughlin, R. P. Barratt, R. K. Power, B. Mercieca-Spiteri, S. Stoddart, and C. Malone. 2020. “Placing and Remembering the Dead in Late Neolithic Malta: Bioarchaeological and Spatial Analysis of the Xagħra Circle Hypogeum, Gozo.” World Archaeology 52: 1. doi:10.1080/00438243.2019.1745680.

- Tilley, C. 1994. A Phenomenology of Landscape: Paths, Places and Monuments. Oxford: Berg.

- Tilley, C. 2004. The Materiality of Stone: Explorations in Landscape Phenomenology. Oxford: Berg.

- van der Noort, R. 1993. “The Context of Early Medieval Barrows in Western Europe.” Antiquity 67 (254): 66–73. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00045063.

- van Leusen, M. 2004. “Visibility and the Landscape: An Exploration of GIS Modelling Techniques.” In Enter the Past. The E-way into the Four Dimensions of Cultural Heritage, edited by K. Fischer Ausserer, W. Börner, M. Goriany, L. Karlhuber-Vöckl, and CD-Rom, BAR International Series, 1227. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Wheatley, D. 1995. “Cumulative Viewshed Analysis: A GIS-based Method for Investigating Intervisibility, and Its Archaeological Application.” In Archaeology and Geographical Information Systems, edited by G. Lock and Z. Stančič, 171–186. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Wheatley, D., and M. Gillings. 2002. Spatial Technology and Archaeology: The Archaeological Applications of GIS. London: Taylor & Francis

- Wilkinson, T. J. 2003. Landscapes of the near East. Tuscon: University of Arizona Press.

- Williams, H. M. 1998. “Monuments and the past in Early Anglo‐Saxon England.” World Archaeology 30 (1): 90–108. doi:10.1080/00438243.1998.9980399.

- Williams, H. M. 2006. Death and Memory in Early Medieval Britain. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.