ABSTRACT

In 1959, the politics of assimilation led to the creation of a set of municipally organised camps for Roma people in the Stockholm area. The camps were to function as controlled settlements of transition for Roma families awaiting proper homes. This paper focuses on one such camp – the Skarpnäck Camp – which existed longer than anticipated, to the point that its continued operation was criticised as being inconsistent with the government’s assimilation policy. This paper represents an analysis of historical archaeological fieldwork at the former Skarpnäck Camp in southern Stockholm and is based upon interviews conducted with former inhabitants of and visitors to the camp. It uncovers aspects of Roma history on the margins of Swedish society and how marginalisation of the Roma group was given physical form in the creation of sanctioned camps.

‘Here was the reserve and over there was the world.’ Allan Demeter points towards the north and the centre of the City of Stockholm, somewhere on the other side of the motorway, beyond the tree line. Together we are visiting the site of the camp where he lived with his immediate family and other relatives between 1959 and 1963. We are visiting a marginal corner of a nature reserve close to one of Stockholm’s suburbs, walking the gravel and climbing the debris in preparation for an excavation of the former Roma camp, and Allan Demeter’s home for several years. This is also the place where the travelling life of Allan Demeter’s family came to an end.

The local authorities had seen fit to close all other Roma camps and settlements, and in 1959 they had persuaded Allan Demeter’s family to move to one of the two camps prepared and controlled by the Municipality of Stockholm. Allan Demeter and his family were to be assimilated, but first they were allotted space in what the municipality defined as a transition camp. All of this happened over 50 years ago, but for Allan Demeter, the experience of living in Skarpnäck Camp has deeply served to mould his character. The cold and harshness of the early 1960s remains a living memory for him, an experience that was activated through archaeological fieldwork of the camp where he lived as a teenager.

Excavating the camp of his teens meant activating memories and emotions of the past. At public presentations of the archaeological site Allan and the rest of the team was met with appreciation and curiosity. But the fieldwork was also met with sceptics and pending sentiments from visitors who did not agree with importance of acknowledging Roma campscapes, Roma history, and the authorities’ role in secluding and marginalising Roma inhabitants in Stockholm. However, conducting archaeology at the former Skarpnäck Camp led to an opportunity for a dialogue between former inhabitants of the camp and members of the majority society, of which some initially expressed sceptics towards the project.

Background

In 2015 and 2016 Allan Demeter came back to the site of the Skarpnäck Camp. He was part of team of Roma people and Roma activists who had experienced life in camps and who were working with archaeologists and ethnologists to uncover the history of the Roma camps and municipally run camps, dedicated to the examination of Roma experiences in the twentieth century. More specifically the project aimed at finding material traces of the former camp. This paper examines the material finds of the Skarpnäck Camp in the light of a wider archaeological study of the Roma camp experience – Roma campscapes – in twentieth century Sweden. The term campscape is used here to emphasise the political and social context of the camp, suggesting that it was much more than a specific location, but part of a larger structure. The purpose of this paper is to present challenges and ways to go forward in uncovering the past of Roma camp life, through asking the question: how can we use archaeology to activate narratives of the Roma camp experience and include material traces of these camps into a general historical-archaeological- and cultural heritage discussion?

Roma studies is a vibrant field of research and considerable work has been done in anthropology and multi-ethnic studies, in cooperation with various Roma groups and discussing housing and neo-ghettofication (e.g. Clough Citation2017; Lancione Citation2019). Current debates concern inclusion of Roma experiences into academic studies (Marushiakova-Popova and Popov Citation2017). But little of this research has related to experiences in either type of camp life in twentieth-century Scandinavia (Tebbutt and Saul Citation2005; Holmberg and Persson Citation2016; Fernstål and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2018). There has been intense interest in the histories and nature of camps, but with a focus on concentration camps, and death camps, both of which include the Roma experience and on prison-of-war camps (cf. Burström Citation2009; Myers and Moshenska Citation2011; Seitsonen, Herva, and Nordqvist Citation2017; Vařeka and Vařeková Citation2017). Yet only limited interest in the broader Roma past has been generated within archaeology (see, however, Andersson ed. Citation2008; Arnberg Citation2017; van der Laarse Citation2017).

Archaeology of camps and the Roma experience

In a European context, historical archaeology encompassing the Roma experience – or rather the absence of a Roma experience – has unintentionally served to reify the marginal position of the Roma in Western society (cf. Bánffy Citation2013). Because the past is often considered as intimately tying together the nation and the state, there is rarely room for other histories outside of this grand narrative (Martins Citation1974; Giddens Citation1990; Chernilo Citation2011). As noted by Alfredo González-Ruibal, there has been a tendency in latter-day historical archaeology to serve as the archaeology of us, the archaeology of the Western World and the majority culture. Historical or contemporary archaeology runs the risk of being a willing servant of prevailing Eurocentric patriarchal politics (González-Ruibal Citation2016, 158). In short, there has been little room within this hegemonic perception for Roma past and for the past shared between the Roma people and the surrounding majority society and a goal for this study has been to broaden the ‘us’ within the field of historical archaeology.

The excavation of the Skarpnäck Camp was directed at and limited to ephemeral source material and the traces of a camp in an urban context; it focused on the more recent past of a group of Kelderash Roma. The camps can be understood in this context as practical biopolitical governance of selection and separation, manifest in its’ time of use, but evasive in terms of material remains (Minca Citation2015, 77). But the broadness of modernity also includes the camps: from the Roma’s own settlements to the majority society’s modes of dealing with homelessness and publicly organised camps to – at the far end of the continuum – the concentration camps. According to Minca (Citation2015), camps of the modern world constitute the essence of modernity, its’ extremely biopolitical governance.

Camps have been constructed as settlements for non-permanent housing. They have also functioned, and still function, for the separation of groups, with those in power determining who should be placed in camps: refugees, criminals, and other unwanted (Clough Citation2017). Moreover, the modern camps have distinct colonial roots, founded by Europeans in Cuba and South Africa in the late nineteenth century and brought to Europe as tools for totalitarian regimes. Modern and contemporary European history features currents of refugees in what can be characterised as an archipelago of camps (Minca Citation2015, 74–75; cf. Gilroy Citation2004).

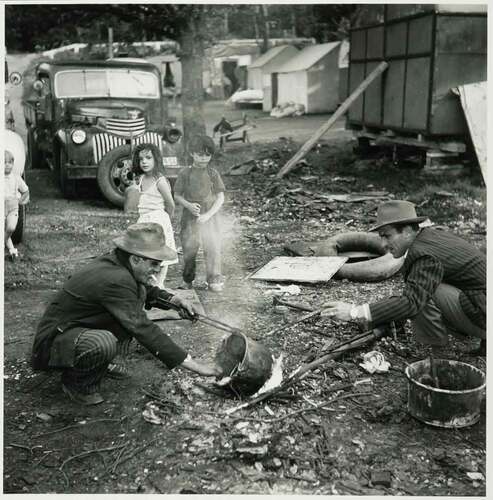

Understanding the camps and life in the camps is a way of understanding the Western World. There are great differences, of course, between the short-term camps established by the Roma communities (see ); the Roma camps prepared by the Municipality of Stockholm in its suburbs, which is focus of this paper; and the death camps of the Holocaust. Yet, as Minca has demonstrated, there are genealogical connections founded on biopolitical governance and rooted in the idea of the Homo Sacer, the clandestine, the outcast (Minca Citation2015, 79; see also Agamben Citation1998, Citation2005). The Stockholm Roma camps in all their forms and breadth of function were similar in the sense that they were non-permanent, tying together a set of experiences that included travel, non-sedentary life, and diaspora

.Nomadism, racism, and assimilation – a short background of Roma history in Sweden

Roma people live all over Europe and have been travelling the continent for the past thousand years, serving as a significant force in connecting various parts of the continent (cf. Tervonen Citation2010). The Roma past is an integral part of European cultural history, in its many contributions through art, craft, and music and there has been Roma living in Scandinavia since at least the late medieval period. The first record of Roma people in Sweden stems from 1512 and concerns a group of people called tatra, that travelled to Stockholm from, it was said, ‘Little Egypt’ (SST Citation1504–Citation1514).

Throughout history, biased legislation and prejudiced practices had grave repercussions for the Roma minority. Since 1637, anti-Gypsyism and general racism in Sweden has been paired with official legislation aimed at expelling the Roma population (Montesino Citation2010; Selling Citation2013). The situation for the Roma people in Europe also includes slavery that ended in Romania in 1856, however, with ethnic cleansing prevailing in many countries, and with Roma genocide that came to be called Porajmos.

During the nineteenth century, the borders of Europe were open in principle, and people could travel freely. One of the groups that included Sweden in their travelling routes was the Kelderash Roma. Kelderash means ‘coppersmith’ – denoting the groups’ main industry – and many of the Kelderash, like several other Roma groups, specialised in tinning copper kettles and cauldrons. The Kelderash came to build the core of the group that by the authorities was called Swedish Gypsies, and later Swedish Roma, during the twentieth century, and along with tinning and divination, they specialised in various forms of showbusiness, such as running amusement fairs and performing music. These types of work were well adapted to a non-sedentary life. Although tinning was a sought-after skill, households rarely required their pots and cauldrons to be re-tinned, but new audiences could be easily reached when on tour (Tervonen Citation2010; Fernstål and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2018).

In 1914 Sweden introduced a new Alien’s Act, which prohibited foreign Roma (zigenare) from entering the country (SFS ,:196), and Roma leaving Sweden would have found their return to be uncertain (Fernstål and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2018, 22–23). The same year, World War I broke out on the continent, and Kelderash families travelling in Sweden could not move abroad, for fear of not being allowed back into the country and a situation of permanent forced migration in a more threatening environment.

After World War II, attitudes and policies towards the Roma in Sweden changed, and the provision of permanent housing became a priority for governmental officials. The experience of the Porajmos on the continent seems not to have been decisive, however. Rather it was the rapid construction of a welfare state in Sweden that could no longer abide having people living nomadic lives and moving from camp to camp. The victory for democracy in the 1920s laid the foundation for vast societal reforms in the 1930s. World War II put these reforms on hold, but after the war, Sweden could rapidly resume the process, and as a result of the struggle for civil rights, Swedish Roma eventually gained citizenship in this phase of modernisation. Concurrently, a large state survey suggested that the Roma had to assimilate in order to solve housing and labour problems (SOU Citation1956). The authorities’ view of the Roma changed from the propagation of separation and segregation to the propagation of assimilation (Montesino Citation2010; Ohlsson al Fakir Citation2015: Hyltén-Cavallius and Fernstål Citation2020).

In Stockholm, this new policy resulted in the establishment of camps on municipal land during a time of far-reaching socio-economic change. There was a rapid decrease in the viability of such industries as horse sales, amusement fairs, and tinning, in which Roma had been successful. Copper kettles were replaced by aluminium and stainless-steel vessels. Such other significant economic activities as divination also declined, although at a slower pace, and new activities such as repairing and selling used cars were added (Takman Citation1966, 43–44).

Historical archaeology in Roma campscapes

In 1958, the social welfare authorities in Stockholm closed several Roma camps and separated their social groups. Some of the former dwellers moved to a new camp at a place called Flysta, north-west of Stockholm. One of those who relocated was Allan Demeter, who was 15 at the time. In the following year, 13-year-old future artist and activist Hans Caldaras moved to Flysta with his family (Caldaras Citation2002, 152–153). The camp was situated close to an inhabited area with people, shops, and even a cinema. For families without storage facilities, this access to grocery stores was of the utmost importance. Our interviews with Allan Demeter and Hans Caldaras tell of good relations with the nearby residents. Hans Caldaras could even go to a proper school for the first time in his life, as one of the first in his family to do so.

One day, upon returning from school, Hans Caldaras was met by police officers, vans, and salvage cars; camp residents were being evicted without previous notice, ostensibly to allow for the development of a nearby local power station (Caldaras Citation2002, 152–153). During our visit to Flysta 2013, Hans Caldaras notes that the power station seems to remain unchanged to this day, that the development probably never occurred – that just as the inhabitants of the camp had suspected, the development was a manufactured reason to evict the Roma families. The Stockholm City Archive contains no documentation stating the reason for the eviction – merely the decision to do so (SSA, vol. F3e:1).

The extended families and friendship groups that had lived together in Flysta were split up, but this time they were designated to move to two camps established by the municipality. These camps, Skarpnäck and Ekstubben, were on the other side of the city, in a more remote and marginalised area, separated from the services they had come to rely upon (see ). The forced move was implemented, despite the goal expressed by Stockholm officials of providing housing and integrating the Roma into society. The inhabitants of the Skarpnäck Camp had to travel several kilometres for groceries and other necessities. For Hans Caldaras, moving from Flysta to the Skarpnäck Camp meant that he had to leave school. And as Allan Demeter told us early on, ‘Here was the reserve and over there was the world’. The feeling of exclusion seems to have been pervasive.

Figure 4. Aerial photo from the Skarpnäck Camp area, 1960. The camp is clearly visible, built as a square around a courtyard, with an exit at the north-east, towards the road. Note the vast forested area surrounding the camp. Photo courtesy of Lantmäteriet.

The Skarpnäck Camp was founded by the authorities who prepared the ground for the caravans, provided water and electricity, and kept the camp under observation (Arnberg Citation2017). Inhabitants were occasionally but forcefully moved between the two camps by the authorities and moved back if they tried to locate their caravan elsewhere (Nygren Citation1963; Fernstål and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2018, 165–175). Living in the Skarpnäck Camp, then, was not an entirely voluntary experience; it included elements of coercion and even force.

Finding the location of the former camp proved complicated. The landscape surrounding the camp had changed drastically since the time of habitation, and the former inhabitants did, at first, not recognise the exact location. What had been open grassland and old meadows was now forested, at the same time as large forested areas had been turned into motorways, roads, and houses. Some photos from newspaper articles were helpful, however, along with a documentary film from 1963 about the situation in the Roma camps in Stockholm (Vagabond eller vanlig människa?/Vagrant or ordinary human being?). The film acknowledged the severe living conditions of the Roma and initialised a wider discussion on the housing situation in the country. As the title of the film suggests, the living conditions in the camps were neither humane nor fitting for permanent habitation.

Images from the documentary film of the camp and its inhabitants were typical of the time in showing the outsiders’ views of the camp yet atypical in allowing the inhabitants to speak for themselves. This documentary proved extremely valuable in identifying the camp’s location: the direction, size, and location of entrances; and the location of electrical poles and water faucets that could help us pinpoint the campsite.

The aerial photo that showed the camp in 1960, and another one after its closure in 1963/64, when it was transformed into a stone-breaking site, also proved most valuable, but they did not allow for any detailed study of the camp. During the time of habitation, the camp would have consisted of approximately 15 caravans and 50 inhabitants. The caravans were jacked up, and several of them had permanent verandas attached. After some years, a few families built cabins with better heating, to replace the cold caravans (Fernstål and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2018, 165–168).

Gravel as material culture

During the two field seasons, comprising two weeks each during the fall 2015 and spring 2016, an area covering roughly 30 square metres in the centre of the former camp were excavated. It was possible stratigraphically to identify seven activity phases at the site, from the period up until c. 1959, when the area was an agricultural field, followed by the authorities’ construction of the site, which required the application of a combination of clay, sand, and field stone topped by crushed gravel (Arnberg Citation2017). The third phase was the actual camp and habitation phase from 1959–1963. It was revealed as a greyish, compact layer of clay and sand. The fourth and the fifth phases constituted the transformation of the camp into a stone-breaking site, with the period for that purpose featured by a thick and heavy construction layer of gravel for stone-breaking.

At first, finds from the post-stone-breaker’s activities were incorrectly identified as remains of the camp. A mass of broken glass bottles, beer and soda cans, electric cables, broken car glass- and lanterns, covered the area underneath the topsoil. The members of the project who had lived there did not agree with the interpretation of this debris coming from the former camp. Here experiences from maintenance of cars by the project members proved important. Reconditioning of cars was the chief occupation in that camp, but it was also clear from the former inhabitants that they would not have left rubbish in front of the caravans and houses. Also objects that for the archaeologists looked old – possibly from the 1950s and 1960s – were dismissed as being too young, stemming from the 1970s and 1980s.

The project members with experience of living in, or visiting the camp, were troubled about the fact that the campsite was located higher than the adjacent road. This elevation, roughly 0,4–0,5 metres would have meant that coming cars would have had to pass up the slope and that the kids would have slope to play on in the north-east – a fact that none of the former inhabitants/visitors could remember. These findings led to a thought-provoking and fruitful discussion, and for a while it seemed as if science, in the form of archaeology would come to one conclusion and the former inhabitants would come to another.

Underneath the c. 0,35–0,4-metre thick, hard-packed layer of applied gravel, a thin compact cultural layer was identified. The area excavated to this depth was limited, given the heavy gravel layer on top of it that had to be shuffled by hand, and the number of finds was limited. It soon become clear, however, that the remains of the camp that was identified could be related to the secluded yard between the caravans and the cottages. The few finds that were recovered were trodden down into the surface of the former yard, and it was clear to all members of the project that the layer was the former activity area. Our finds consisted of a slit electric cable, a bottle top, and the right leg of a plastic doll. The cable provided little information about life in the camp, except for suggesting evidence of repair, confirming the former inhabitants’ stories of their parents’ constant work to provide the camp site with electricity for heating and light. It stood clear that the camp ground had been a clean prepared surface for common activities, and that the surface overlaying the layers form the camp period was heightened, just as suggested by the former inhabitants/visitors.

The doll’s leg indicates child activity, illustrating what Sabrina Taikon, who had lived in the camp as a child, had told us – that the yard of the camp was a secure area for children, surrounded by caravans and cottages inhabited by relatives and friends. This is where the children could play, where parents and relatives easily could keep an eye on them. The doll’s leg was slightly more than 3 centimetres in length, suggesting that the doll would not have been taller than 8 or 9 centimetres, and a relatively distinct junction from the casting of the plastic suggests that the doll was a cheap toy. This find could point to material poverty in the camp, but the interviews and recurrent discussions with the former inhabitants provided a different view. Some of the children in the camp had teddy bears, someone had a pedal car, and in a shed next to Sabrina’s family’s cabin there was a miniature electric railroad (Arnberg Citation2017). Life in the camp was harsh, and economic liberty was limited to say the least, but poverty is not the main feature in the narratives of the former camp dwellers. Much more prevalent are the stories of the cold during the winters and how far it was from everything else.

The main archaeological finding was the heavy layer of gravel that provided the camp’s foundation (see ). In the authorities’ correspondence found in the Stockholm City Archive, the camp is described as a temporary, even short-term solution – a transition before the inhabitants moved to proper apartments. Some years later, however, civil servants described how the camp had outlived its original purpose as a short-term camp (SSA vol. F3a:2)

Figure 6. Finds from the Skarpnäck Camp, 1959–1963. Photo Helena Rosengren, the Swedish History Museum.

The heavy, well-prepared construction layer established by the authorities probably contributed to the slow development of this project from a temporary camp to permanent housing. It was necessary to prepare the former agricultural field for the caravans, but it can also be understood as a material aspect of the unofficial desire to segregate the Roma from the rest of society. Was all this work done for a brief stay before moving the inhabitants into permanent housing? The gravel provided a firm foundation of the political technology of a highly modern society (cf. Minca Citation2015, 75–76).

These findings suggest that the layer of gravel that was spread up to 0.4 m over the field that was to become the camp site to provide a flat surface for the caravans clearly served another function. It not only made life easier for the camp’s inhabitants, but it also constrained them, since they were not allowed to move elsewhere. The thorough work conducted by the Municipality of Stockholm kept Allan Demeter and his family firmly tied to the site, thus creating marginality as a day-to-day experience. These bonds were so strong that it would require the force of one of Sweden’s principal civil rights activists to break it.

In autumn 1963, Roma activist Katarina Taikon, who had grown up in camps, published her book entitled Zigenerska (Gypsy Woman) – an autobiographical indictment concerning the situation of the Roma in Sweden (Taikon Citation1963; Mohtadi Citation2012). During the same year, the Roma received great media attention, as exemplified by the documentary film described previously. No doubt the close-up portrait of the life in the Skarpnäck and Ekstubben camps in the middle of snowy winter had a great importance in this growth in attention. A few months after Taikon’s publication, the inhabitants of the camps were offered lease contracts for apartments (Fernstål and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2018, 169, 173–174, 182).

Activating contested margins

As most archaeologists know, putting a spade into the ground creates public interest and public excitement. Hundreds of people came by the former camp sites to view the fieldwork, spontaneously or as part of organised guided tours. A clear majority of the reactions were positive. Other visitors were sceptical. One elderly man, who had lived in a nearby suburb his entire life, kept coming to the excavation, eager to talk. He was obviously vexed by the fact that archaeological fieldwork was being conducted on a Roma site, and he tried to direct the conversation to other possible targets for archaeological research and mentioned burials from the Viking Age as a specific example of higher relevance. Yet, he kept returning to the Roma past with an obvious urge to play down the role and importance of the Roma and continued make such comments as ‘They are not Swedish.’ and ‘Why are you not excavating a Swedish site instead?’ He also consistently used the derogatory term zigenare (Gypsy) rather than the now commonly agreed-upon word, ‘Roma’. Initially he even tried to convince us that there had never been a camp at the site.

The man also came on one of the organised tours on which Allan Demeter was discussing his experiences of the Skarpnäck Camp life. When Allan Demeter spoke about the day-to-day living conditions, about such concrete issues as fetching water during winter, and how the electricity worked, the visitor forcefully declared that there had never been a water pump at the camp. He insisted that the faucet was placed some hundred metres away. He also expressed sceptics that such a camp had ever existed. Allan Demeter insisted that he had a clear memory of fetching water, and the situation became awkward because the visitor was reluctant to respect Allan Demeter’s narrative. After the tour, the man lingered; he was not unfriendly, but he was not yet satisfied, and he kept talking to Allan Demeter and others. Allan Demeter and the man were roughly the same age and could perhaps have met 50 years ago. Eventually it seemed as if he accepted the fact that there had been a Roma camp not far from where he had grown up.

The visitor, his questions, his eventual at least partial acceptance, and the many other visitors to the site indicate the importance of locating Roma past and present to the shared landscape, in showing where and how Roma experiences had occurred and that it was of general interest to many people other than the former inhabitants. The archaeological excavation provided an arena for various people to meet. The prejudiced visitor was given an opportunity to meet a Roma person, and he was also able to see how history was constructed, how archaeology worked, and that archaeology differed from what he had anticipated. It seems, at the end, that this man was quite satisfied merely to be part of discussions about the past and that the time he spent at the excavation and in talking to Allan Demeter made him more open to experiences other than his own.

Conclusions

The making of modern society was forceful and dramatic. In the welfare state of Sweden, it meant security, democracy, and the right to self-determination for the majority. Minorities such as the Roma were, to a lesser degree, part of this development. The majority society regarded the Roma as strangers, both physically and culturally. The making of Sweden’s collective past, present, and future did not encompass the Roma; nor did Swedes in general see the Roma experience as part of the history of their country. Instead, the Swedish authorities found various ways of separating the Roma from the rest of society, also during a period of expressing intentions to assimilate Roma people.

This paper has presented the results from an excavation of a former, by the authorities founded camp for a group of Roma people, inhabited between 1959 and 1963. The fieldwork was conducted as a cooperation between former inhabitants of and visitors to the camp, archaeologists and ethnologists with the purpose of examining the material remains of the former Skarpnäck Camp. The fieldwork called for an intensified dialogue and co-interpretation of the former camp and its’ remains – a process that would prove fruitful for the deeper knowledge of the situation in the camp and the use of the location after its’ abandonment – including the public activities taking place as part of the field work.

The archaeology and history of post-World-War-II Roma camps on the outskirts of Stockholm are merely fragments of our recent past. Growing public opinion in Sweden and in the rest of Europe has led to attempts to establish a historical narrative that excludes the Roma experience – not unlike that of the sceptical visitor at the Skarpnäck excavation. Illiberal forces are trying to exclude voices, narratives, and experiences from a perceived shared history of the majority society. Studies such as the excavation of the Skarpnäck Camp have become increasingly valuable in demonstrating how archaeology can contribute to more nuanced and inclusive perspectives in a rapidly polarising world.

Figure 1. Excavation and field discussion at Skarpnäck Camp, August 2016. From left to right, Marianne Demeter, Allan Demeter, and Fred Taikon; in the foreground Jonas Monié Nordin. Photo: Lotta Fernstål.

Figure 3. Tinning in a Roma camp 1954. To the right Borta Friberg, member of the project group. Photo Anna Riwkin. Courtesy of Moderna Museet, Stockholm.

Figure 5. Still photo from 1963: the television documentary, Vagabond eller vanlig människa? [Vagrant or ordinary human?] The Skarpnäck Camp during winter from Southeast.

![Figure 5. Still photo from 1963: the television documentary, Vagabond eller vanlig människa? [Vagrant or ordinary human?] The Skarpnäck Camp during winter from Southeast.](/cms/asset/d3a49b18-bec8-49e9-9444-93d5e5a2e923/rwar_a_1999852_f0005_b.gif)

Figure 7. Photo from trench nr 2, showing the stratigraphic sequence. The lower surface corresponds to the layer of gravel laid by Stockholm municipality in 1959; the middle surface to the thin occupation layer of the camp (1959-1963); the upper surface in the foreground is the layer of gravel used as a foundation for the stone-breaker post in 1963. Photo Anna Arnberg.

Acknowledgments

This paper was written as part of the research project, The margins of the City, Roma life stories and camps in the twentieth century, funded by the Swedish National Heritage Board and the Swedish History Museum. The authors wish to thank Allan Demeter, Borta Friberg (†), Fred Taikon, Hans Caldaras, Marianne Demeter, Sabrina Taikon, Vedel Demetri, and Marco Ali for their collaboration throughout the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jonas Monié Nordin

Jonas Monié Nordin Associate Professor, Department of Archaeology and Classical Studies, Stockholm University, [email protected]

Lotta Fernstål

Lotta Fernstål, Researcher, Ph.D. The National Historical Museums, Sweden, 114 84 Stockholm, [email protected]

Charlotte Hyltén-Cavallius

Charlotte Hyltén-Cavallius, Researcher, Associate Professor, The Institute for Language and Folklore, Uppsala, Sweden Box135, 751 04 Uppsala, charlotte.hylten-[email protected]

References

- Agamben, G. 1998. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Agamben, G. 2005. State of Exception. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Allan Demeter (DFU 41006).

- Allan Demeter and Marianne Demeter (DFU41007).

- Andersson, B., ed. 2008. Snarsmon: Resandebyn där vägar möts. Uddevalla: Bohusläns Museum.

- Arnberg, A. (ed.). 2017. Skarpnäckslägret: Arkeologisk undersökning av en svensk-romsk lägerplats vid Flatenvägen i Skarpnäck. Statens Historiska Museer, Fou Rapport 17.

- Archive

- Bánffy, E. 2013. “The Nonexisting Roma Archaeology and the Nonexisting Roma Archaeologists.” In Heritage in the Context of Globalization: Europe and the Americas, edited by P. F. Biehl and C. Prescott, 77–83. SpringerBriefs in Archaeology 8. New York: Springer.

- Borta Friberg (DFU 41001).

- Burström, M. 2009. “Selective Remembrance: Memories of a Second World War Refugee Camp in Sweden.” Norwegian Archaeological Review 42 (2): 159–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00293650903351045.

- Caldaras, H. 2002. I betraktarens ögon. Stockholm: Norstedts.

- Chernilo, D. 2011. “The Critique of Methodological Nationalism: Theory and History.” Thesis Eleven 106 (1): 98–117. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0725513611415789.

- Clough, M. I. 2017. “The Informal Faces of the (Neo-)ghetto: State Confinement, Formalization and Multidimensional Informalities in Italy’s Roma Camps’.” International Sociology 32 (4): 545–562. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0268580917706629.

- Fernstål, L., and C. Hyltén-Cavallius, eds. 2018. Romska liv och platser. Berättelser om att leva och överleva i 1900-talets Sverige. Stockholm: Stockholmia förlag.

- Fred Taikon (DFU 41004:1, 2).

- Giddens, A. 1990. The Consequences of Modernity. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Gilroy, P. 2004. After Empire: Melancholia or Convivial Culture. London: Routledge.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2016. “Archaeology and the Time of Modernity.” Historical Archaeology 50 (3): 144–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03377339.

- Holmberg, I. M., and E. Persson. 2016. “Ephemeral Urban Topographies of Swedish Roma.” Cultural Studies 30 (3): 441–466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09502386.2015.1113634.

- Hyltén-Cavallius, C., and L. Fernstål. 2020. “ … of immediate use to society”. On Folklorists, Archives and the Definition of “Others”. Culture Unbound: Journal of Current Cultural Research 12: 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.3384/cu.2000.1525.2020v12a08.

- Lancione, M. 2019. “The Politics of Embodied Urban Precarity: Roma People and the Fight for Housing in Bucharest, Romania.” Geoforum 101: 182–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.09.008.

- Literature

- Martins, H. 1974. “Time and Theory in Sociology.” In Approaches to Sociology, edited by J. Rex, 246–294. London: Routledge.

- Marushiakova-Popova, E. A., and V. Popov. 2017. “Orientalism in Romani Studies: The Case of Eastern Europe.” In Languages of Resistance: Ian Hancock’s Contribution to Romani Studies, edited by H. Kyuchukov, and W. New, 1–48. München: Lincom Europa.

- Minca, C. 2015. “Geographies of the Camp.” Political Geography 49: 74–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2014.12.005.

- Mohtadi, L. 2012. Den dag blir jag fri: En bok om Katarina Taikon. Stockholm: Natur & Kultur.

- Montesino, N. 2010. Romer i svensk myndighetspolitik – ett historiskt perspektiv. Meddelanden från Socialhögskolan 2:2010. Lund: Socialhögskolan, Lunds Universitet.

- Myers, A., and G. Moshenska, eds. 2011. Archaeologies of Internment. New York: Springer.

- Nygren, O1963De har stått 400 år i bostadskö Stockholms-Tidningen 2 October 1963.

- Ohlsson al Fakir, I. 2015. Nya rum för socialt medborgarskap: Om vetenskap och politik i “zigenarundersökningen” – en socialmedicinsk studie av svenska romer 1962–1965. Växjö: Linnéuniversitetet.

- Other sources

- Personal communication and interviews 2015–2016. Interviews archived in The Institute for Language and Folklore, Uppsala, Sweden.

- Sabrina Taikon (DFU 41009:1, 2).

- Seitsonen, O., V-P. Herva, and K. Nordqvist. 2017. “A Military Camp in the Middle of Nowhere: Mobilities, Dislocation and the Archaeology of a Second World War German Military Base in Finnish Lapland.” Journal of Conflict Archaeology 12: 3–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15740773.2017.1389496.

- Selling, J. 2013. Svensk antiziganism: Fördomens kontinuitet och förändringens förutsättningar. Ormaryd: Östkultur.

- SFS 1914:196. Lag angående förbud för vissa utlänningar att här i riket vistas. Svensk författningssamling [Swedish Code of Statues]. Stockholm: Fakta Info Direkt AB.

- SOU 1956. 1956. Zigenarfrågan. Betänkande avgivet av 1954 års zigenarutredning, 43. Stockholm: Socialdepartementet, Statens offentliga utredningar.

- SST. 1931. Stockholms stads tänkeböcker 1504–1514. 9 vols, 169. Original in Stockholms stadsarkiv, SSA/0091, Borgmästare och råds arkiv före 1636.

- Stockholm City Archive (SSA), volume F3a:2, Handlingar rörande bostadsfrågor.

- Taikon, K. 1963. Zigenerska. Stockholm: Wahlström & Widstrand.

- Takman, J. 1966. Zigenarundersökningen 1962–1965. Slutrapport den 31 mars 1966. Stockholm, Uppsala: Arbetsmarknadsstyrelsen, Uppsala universitet.

- Tebbutt, S., and N. Saul, eds. 2005. The Role of the Romanies. Images and Counter Images of “Gypsies”/Romanies in European Cultures. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.

- Tervonen, M. 2010. ‘Gypsies’, ‘Travellers’ and ‘Peasants’: A Study on Ethnic Boundary Drawing in Finland and Sweden, c. 1860–1925. Firenze: European University Institute.

- Vagabond eller vanlig människa? Film by Roland Hjelte and Karl-Axel Sjöblom 1963, https://www.svtplay.se/video/13930344/vagabond-eller-vanlig-manniska

- van der Laarse, R. 2017. “Lety Roma Camp. Discovering the Dissonant Narratives of a Silenced Past.” Accessing Campscapes: Inclusive Strategies for Using European Conflicted Heritage (2). Published online https://pure.uva.nl/ws/files/24918675/e_journal_ACCESSING_CAMPSCAPES_no2_1.pdf

- Vařeka, P, and Z. Vařeková. 2017. “Archaeology of a Ziegeunerlager. Initial Results of the 2016-2017 Investigations of the Roma Camp in Lety.” Accessing Campscapes: Inclusive Strategies for Using European Conflicted Heritage 2: 20–29.