ABSTRACT

Material culture worked as an essential supporting pillar of the ancient Egyptian colonization of Nubia. During the New Kingdom colonial period (1550–1070 BCE), the material culture of various colonial sites in Nubia consisted of a majority of Egyptian-style objects (including both imported and locally produced objects). Egyptian-style objects materialized foreign presence in local contexts and allowed communities to negotiate identities and positions in a colonial situation. However, far from homogenizing local realities, foreign objects performed different roles in local contexts. This sheds light on the social dimensions of culture contacts in colonial situations and allows us to identify how the local adoption and uses of foreign objects in local contexts produces marginality in the colony.

Introduction

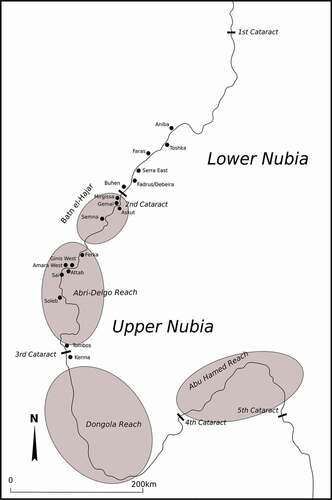

Ancient Nubia, one of the oldest African states, has traditionally occupied a marginal place in historical narratives of ancient Africa. Scholarship on ancient Nubia has been strongly marked by an Egyptological bias that resulted in interpretations of Nubia obscured by Egyptian history (Williams and Emberling Citation2020). This is especially the case for the period when Egypt invaded and colonized Nubia. First, in the Middle Kingdom (2025–1700 BCE), the ancient Egyptians invaded Nubia and colonized its northernmost area, known as Lower Nubia, which allowed the ancient Egyptians to expand their southern border further south, from Aswan to Semna (). In this period, the Egyptians erected a series of fortresses along the Nile, which allowed them to control both the region and the influx of commodities from Nubia into Egypt. With the fall of the Middle Kingdom, Egypt lost its control over Lower Nubia, and these fortresses became independent communities, which included expatriates and Indigenous populations (Smith Citation1995, 80).

Figure 1. Map of New Kingdom colonial Nubia showing the sites mentioned in the text. In the New Kingdom, there was limited Egyptian presence in peripheral areas such as the Batn el-Hajar, the northern portion of the Abri-Delgo Reach and the Abu Hammed Reach. Scattered remains of settlements (likely linked to the processing of gold ore) and burials are currently being explored in the Batn el-Hajar (Edwards Citation2020), as well as the 4th cataract area (Paner and Pudło Citation2010, 138–139). Map by R. Lemos.

With the advent of the Egyptian New Kingdom (1550–1070 BCE), Egyptian forces marched once again towards the south. Following the reconquest of older fortresses in Lower Nubia, which were later remodeled and reoccupied (Spencer Citation2019, 438), years of expansive warfare extended Egyptian presence to Upper Nubia, resulting in the establishment of a settlement at Sai Island, in the Third Cataract area (Budka and Doyen Citation2013).

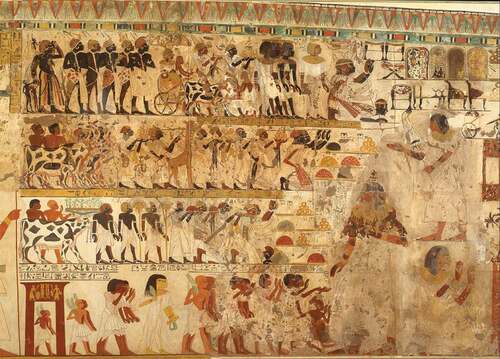

Nubia is a region rich in gold and other resources valued by the Egyptian empire (Klemm and Klemm Citation2013). These resources were portrayed in elite tombs at Thebes as tribute brought by colonized Nubians to Egyptian officials during the peak of colonization ().

Figure 2. Tribute scene from the Theban tomb of Huy (TT40), viceroy of Kush (Upper Nubia) under Tutankhamun (1336–1327 BCE). In this scene, Nubian elites, including Hekanefer, Prince of Miam/Aniba, were portrayed presenting tribute from Nubia (most importantly, gold) before the honored viceroy of Kush. Facsimile by the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nubian_Tribute_Presented_to_the_King,_Tomb_of_Huy_MET_DT221112.jpg.

In the New Kingdom colonial period, the Egyptians built various settlements along the Middle Nile Valley, known as temple-towns, which worked as centers of colonial power and administration. These walled settlements usually included a stone temple and other cultic areas, magazines and other functional buildings and houses. Large cemeteries comprising monumental Egyptian-style pyramid tombs and simpler burials developed in association with temple-towns. Tomb architecture and textual evidence reveal the elite status of these cemeteries, with many individuals working for the colonial administration and possessing numerous Egyptian-style grave goods. Recent isotopic analysis proved that individuals employed by the Egyptian colonial administration buried at elite cemeteries were both foreign settlers and local individuals (Buzon, Simonetti, and Creaser Citation2007; Retzmann et al. Citation2019). For instance, isotopic analysis of the remains of a male skeleton from Sai, identified by inscriptions as Khnummose, Overseer of Goldsmiths, demonstrated his local origin, despite his Egyptian name and Egyptian-style burial goods (Budka Citation2021).

Recent approaches to ancient Nubian material culture revealed complex cultural interactions in the New Kingdom colonial period (Spencer, Stevens, and Binder Citation2017a). Although such approaches have placed Nubian agency in culture contact equations in the Middle Nile valley, perspectives grounded in the concept of ‘cultural entanglement’ contribute to a certain degree of homogenization of Nubian colonial society (e.g. van Pelt Citation2013). The ancient Egyptian focus on colonial towns and cemeteries, together with Egyptological approaches to the material culture of cultural contact in ancient colonial Nubia, has left the vast majority of the population out of major historical narratives.

This paper offers some thoughts towards a more inclusive archaeology of New Kingdom colonial Nubia, which takes into consideration diverse material experiences of colonization and its local results. Moving beyond a focus on ‘Egyptian’ and ‘Nubian’ cultures in contact, the present paper outlines the distinctive material experiences of colonization in different social spaces towards a better understanding of social variability within colonial Nubia, including social and geographical areas traditionally left outside approaches to the ancient Nubian colonial past. We argue that the archaeology of New Kingdom colonial Nubia should move forward from ‘culture’ to ‘society’ to acknowledge a diverse array of experiences that only archaeology has the potential to unveil.

Shifting our focus from cultural contacts to social relationships allows us to explore the social impacts of imposed cultural contacts, which were established based on a wave of Egyptian-style material patterns that flooded Nubia in the New Kingdom (Lemos Citation2020; see Pitts Citation2019; Pitts and Versluys Citation2021). More than the product of cultural mixture or entanglements, material culture allows us to uncover alternative social logics that work as evidence for local creativity in a context of attempted colonial homogenization. Cultural entanglement approaches provided a necessary way out of previous acculturation-based interpretations by emphasizing Indigenous agency. However, focusing on the social impacts of cultural contacts reveals that creativity (e.g. alternative consumption patterns or local modification/reproduction of foreign objects) often resulted in marginalization.

This paper explores how colonial impositions (and cultural contacts resulting from these impositions) generated a form of marginalization, both between the colonizer and the colonized and within the colony. Archaeologically, object flows from Egypt to the colony become the norm. However, the same patterns reached different local contexts within Nubia. These contexts were characterized by different hierarchical forms, modes of differentiation and identities, which dictated how and to whom objects would become accessible. Therefore, instead of producing homogenization, colonial normativity produces cultural diversity, but also marginalization. This takes the shape of refusal to consume elements of the norm and allodoxic consumption patterns (Bourdieu Citation1984, 323 passim), especially in areas outside major colonial centers where consumption of restricted Egyptian-style objects was more extensive (Lemos Citation2020). Based on Dietler’s approach to cultural entanglement, Smith has moved beyond the simple acknowledgement of cultural mixture by addressing ‘individual choices in the adoption, adaptation, indifference, and rejection of intercultural borrowing’ (Smith Citation2020, 372; see Dietler Citation2010). The present paper aims to move discussion forward by exploring the nature of such borrowing and its social impacts, which segregated the colonized from the colonizer, in addition to segregating various groups inhabiting different areas of the colony through their ways of having access to and handling foreign objects in local contexts.

Imposition and homogenization

The Egyptian New Kingdom colonization brought to Nubia new hierarchies and power structures, known, for instance, from the titles and occupations of those linked with the administration of the colony (Müller Citation2013). Titles inscribed on mortuary objects from major cemeteries include mayors, overseers of works, various types of cultic roles, scribes etc. These are evidence of imposed Egyptian hierarchies into the Nubian colony, which substituted, to a high degree, previous Nubian forms of social organization (Edwards Citation2004, 79). The socio-economic system of colonial Nubia has been traditionally understood as mirroring the redistributive socio-economic system of Egypt itself, based on the institutions of the palace and the temple, although the later ‘organic’ development of previously planned walled settlements suggests local socioeconomic development (Kemp Citation1972, 651; Spencer, Stevens, and Binder Citation2017a, 37–40).

Alongside the imposition of a foreign socio-economic system to material realities extant in Nubia prior to colonization, the Egyptian presence in New Kingdom colonial Nubia was also marked by an extreme degree of substitution of Nubian-style objects for Egyptian-style material culture at urban sites and cemeteries – contexts that, until recently, have mainly been approached in isolation. Especially at cemeteries, this phenomenon was accompanied by the dominance of extended burials in Egyptian style over a small number of flexed burials, which were more common among previous Nubian communities (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy Citation1991; Smith Citation2003, 40). In this context, Egyptologists emphasized acculturation or Egyptianization, while failing to acknowledge variability. Variation within sites materialized, for instance, as the permanence of a somewhat standard frequency of Nubian pottery at colonial settlements (Smith Citation2003, 116).

For example, domestic architecture at previous Nubian sites has been interpreted as gradually evolving into shapes imitating Egyptian architecture (Säve-Söderbergh Citation1989, 10), and Egyptian-style objects from cemeteries have been used as evidence for standardization and described as mass-produced and ‘identical in form, material and technique’ to objects from Egypt (Reisner Citation1910, 61; Steindorff Citation1937, 75). Gradually, however, the material culture of settlements and cemeteries in New Kingdom colonial Nubia started to become evidence for complex interactions, experiences, and social forms (Budka and Doyen Citation2013, 182; Smith Citation2020, 372–373; Lemos Citation2020, 21).

A global Egyptian-style objectscape spread throughout Nubia in the New Kingdom and materialized colonization in local contexts (see Pitts Citation2019; Pitts and Versluys Citation2021). However, the distributions of the same types of Egyptian-style objects vary at different colonial sites, which implies that the adoption of the same patterns followed diverse expectations that characterized different communities and spaces (Lemos Citation2020, 17–19). Various ways of handling the same types of objects across and within sites further suggests that Nubia’s internal diversity played a major role in the shaping of local social realities. A varying set of social rules and structural limitations characterized these realities, for example, increased room for negotiations through consumption of restricted foreign objects at temple-towns or overall material scarcity in peripheral areas, such as the Batn el-Hajar.

The same global objectscape reached diverse social contexts within Nubia, which restrained homogenization (Lemos Citation2020). However, the social implications and effects of colonial impositions of material culture in New Kingdom Nubia remain to be fully understood beyond cultural contacts, for example, inequality in the access to objects that facilitated power negotiations or non-elite solutions to scarcity, which would further stress certain groups’ marginal position within colonial society and in relation to the colonizer.

Ideology, colonial hierarchies and marginalization

Egyptocentric interpretations of ancient Egyptian impositions and attempts to homogenize their Nubian colony in the New Kingdom reflect modern colonial ideologies. At the beginning of the 20th century, such colonial ideologies manifested as racist theories on the origins of ‘civilization’ in the Nile valley based on migration perspectives (Smith Citation2018). In this context, Nubia was widely seen as barbaric and inferior to the Egyptian ‘civilization’, which produced textual and iconographical sources documenting, in an ideological fashion, their encounters with other peoples (Smith Citation2003).

Tomb paintings at Thebes in Egypt () allow us to catch glimpses of social hierarchies imposed upon Nubia by Egyptian colonizers and how those hierarchies were ideologically displayed. These sources also work as evidence for the material colonization of Nubia, as the objects reflected in such scenes match objects excavated at various cemeteries (Smith Citation2003, 107; Lemos Citation2020, 12–13). The viceroy of Kush and his immediate subordinates would be at the top of the colonial social system, followed by intermediaries, such as local princes and middle-range officials working for the colonial administration, and lesser workers, servants and prisoners. The overseer of goldsmiths Khnummose was one of the middle-range officials who managed to display a considerable amount of power locally through his imported burial assemblage, which established cultural affinities with Egypt, despite him being local to Sai (Budka Citation2021). Regarding the majority of the population composed of lesser urban workers and agricultural laborers living around temple-towns (but mostly in the areas in-between such colonial centers) our knowledge is still very limited, which is partly due to the Egyptological focus on Egyptian centers of colonial administration (O’Connor Citation1993, 58–65).

Egyptian images and inscriptions, together with imposed material patterns, work as supporting pillars of colonization in Nubia. For instance, representations, such as , were interpreted as either depicting acculturated Nubians who did not quite manage to fully comprehend the Egyptian patterns they assimilated to (Davies and Gardiner Citation1926, 24), or as an example of cohesive integration to a superior culture by people aspiring to become like their colonizer (Kemp Citation2018, 37–38). We can extract from such interpretations a sense of marginalization of colonized Nubia both by the ancient Egyptians and modern Egyptology. However, the creation of social hierarchies and marginal identities between the colonizer and the colonized involved much more complex phenomena than Egyptocentric perspectives allow us to unveil.

From a local agency perspective, these scenes have been interpreted as representations of ‘people who had developed a culturally entangled identity, which combined their local identity with an identity linked to the colonial culture’ (van Pelt Citation2013, 535). Therefore, individuals living in the Nubian colony could borrow elements of both Egyptian and Nubian cultures to build an ambivalent sense of identity that would be contextually negotiated. This would be mostly expressed by the contextual displays of Hekanefer’s identity as a Nubian prince at TT40 and as an Egyptian at his own tomb in Lower Nubia (Simpson Citation1963, 9). In a context of colonial impositions, building cultural affinities with Egypt would allow individuals to reinforce their power within the colony. However, in various cases, Egyptian-style material culture ended up being used differently in local contexts (). This has been interpreted as cultural entanglements resulting from the ‘continual mediation of indigenous agency, local cultural practice, and colonial structure in an ever hybridizing culture’ (van Pelt Citation2013, 533).

Figure 3. Regular globular jars topped with clay lumps simulating human heads from tomb 26 on Sai island. Photo by C. Geiger. Courtesy of the AcrossBorders project. These objects illustrate local cultural practices in a colonial temple-town. The ordinary shape of pottery vessels finds parallels at other New Kingdom colonial cemeteries in Nubia (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy Citation1991, 25). However, those from tomb 26 were repurposed to (re)create Egyptian-style canopic jars. The new entangled shape is far removed from contemporary Egyptian shapes, although it was considered effective in local negotiations of power and identities, which would have remained marginal to ‘proper’ Egyptian ways, or social spaces within Nubia where usual canopic jars were deployed (e.g. Säve-Söderbergh and Troy Citation1991: plate 59).

However, the excessive cultural focus of entanglement perspectives resulted in a lack of acknowledgement of the internal diversity within Nubia and its social hierarchies and structures, which placed ambivalent, entangled colonial identities in scales of distinction and power, therefore producing marginalization. The various ways in which imposed homogenizing material culture were handled in local contexts would result in a variety of practices, which would have placed local groups in the colony in a marginal situation, both globally in comparison with the colonizer, and internally across the boundaries of social spaces. These were characterized by distinctive principles of differentiation and access to material culture, on the basis of which various groups distinguished themselves (Bourdieu Citation1985, 229).

Agency at the margins: the social impacts of cultural contacts

In colonial Nubia, cultural entanglements depended on one’s ability to interact, either in person or mediated by objects, with the patterns of the colonizer. In some areas characterized by material scarcity outside the reach of major colonial centers, Egyptian-style objects are rare. However, evidence from temple-towns and cemeteries allows us to unveil the social impact of cultural entanglements that permitted individuals possessing Egyptian-style objects to negotiate blurred identities and, most importantly, hierarchical positions of power.

Cultural entanglements represent only a small fraction of colonial society in New Kingdom Nubia. They allow us to understand the dynamics of culture contacts amid social spaces where people were able to consume restricted types of Egyptian-style objects. However, such an approach, based on two interacting entities (‘Egyptian’ and ‘Nubian’) risk minimizing variability within both entities (Lemos Citation2020, 20). Even within the social spaces inhabited by communities who managed to consume Egyptian-style objects (colonial elites at temple-towns and associated non-elites, such as urban workers), a high degree of variation can be detected, which accounts for broader dynamics than culture only; e.g. power structures (cf. Edwards Citation2020, 397). In other words, the problem with cultural entanglement approaches is that they do not allow us to see the whole of Nubia. As laid out by van Pelt (Citation2013), the concept of cultural entanglement was built on the grounds of elite contexts including those who interacted with Egyptian colonizers able to consume Egyptian-style material culture that would allow people to negotiate identities in a colonial situation characterized by imposed foreign Egyptian patterns (Lemos Citation2018, 28).

Elite contexts in New Kingdom colonial Nubia comprise both settlements and cemeteries located mostly at temple-towns, where inhabitants were more able to consume than in regions such as the Batn el-Hajar, which were characterized by archaeological invisibility of communities and an overall scarcity of objects. In the living sphere, there is a considerable gap regarding work at sites in the periphery of major settlements. At present, despite recent progress in the study of settlement patterns in New Kingdom colonial Nubia, our knowledge of the peripheries surrounding major administrative centers remains limited (Spencer, Stevens, and Binder Citation2017a, 42; cf. Edwards Citation2020; Budka Citation2020).

In the funerary sphere, Edwards pointed out that ‘the interest commonly placed on the (elite) tomb should not narrow our perspectives, to the exclusion from our narratives of the vast majority of the population who were buried otherwise’ (Edwards Citation2020, 396; Nördström Citation2014, 157). He is referring to the methodological abuse, common within the archaeology of the Nile valley, of sources originating in elite contexts to understand the whole society, despite mortuary variability (Richards Citation2005, 52; Smith Citation1992).

If a focus on ‘Nubian’ culture somehow masks various hierarchical inputs to cultural interactions within social spaces where people were able to consume Egyptian-style objects and therefore negotiate positions and identities, an elite bias further contributes to the exclusion of a diverse array of marginal experiences of colonization outside those contexts. Examples include isolated burials in areas outside Egyptian temple-towns, such as the today inhospitable Batn el-Hajar, where so far invisible communities lived and died probably working in the processing of gold extracted in the Nubian deserts (Edwards Citation2020, 398) or even connected to nomad polities surrounding the borders of the agricultural state, who possessed their own ways of establishing social relations (Sadr [Citation2017 [1991], 108; Cooper Citation2021, 18). These tombs pose a challenge to narratives focused on culture contacts at elite colonial centers, especially because they hold the potential to unveil alternative material realities and social logics that produce, at the same time, creative negotiations and marginality.

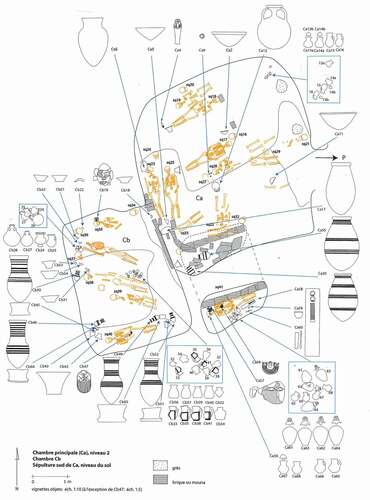

Cemeteries associated with colonial centers, such as Aniba, Sai and Soleb, are characterized by monumental tombs with pyramid superstructures and various underground chambers housing several individuals buried according to ‘Egyptian’ rules (). Those individuals were buried with a restricted set of standardizing Egyptian-style objects, which spread throughout Nubia in a discontinuous way, suggesting that the same patterns were adopted differently by different groups (Lemos Citation2020). If material culture was a crucial supporting pillar of the Egyptian colonization of Nubia, objects did more than just materialize the ‘Egyptian’ presence.

Figure 4. Plan and disposition of various Egyptian-style objects in the lower layers at Sai SAC5 tomb 14 (Minault-Gout and Thill Citation2012: plate 71, courtesy of A. Minault-Gout and F. Thill).

In Egypt, ideally, shabti figurines deposited in tombs were magically activated in the afterlife by means of inscriptions mentioning their owners’ names and titles. In Nubia, various imported, pre-inscribed stone shabtis were deposited in tombs with spaces for names and titles left blank (Steindorff Citation1937, 75), and many faience and clay shabtis were probably produced locally with no inscriptions (Minault-Gout and Thill Citation2012: plates 99–100). This suggests alternative conceptions and practices of those objects, especially in the light of local modifications on imported stone shabtis, which resulted in stylistic innovation (). Handling foreign objects in local contexts was not limited to adaptation, but could also result in completely local versions of objects (e.g. Spencer, Stevens, and Binder Citation2017b, 78). Objects such as shabtis shed light on cultural entanglements between foreign and local patterns. However, more than cultural mixture, Egyptian-style objects in Nubia unveil various social structures extant in the colony, which depended on one’s ability to consume Egyptian-style objects that would allow entanglements to take place.

Figure 5. Serpentinite shabti T8Cc79 from Sai (Minault-Gout and Thill Citation2012: plate 92, courtesy of A. Minault-Gout and F. Thill). Various additional decorative elements were carved on ‘unusual’ places (head, shoulders and feet) probably to make an earlier imported model fit later local expectations. Evidence for the local adaptation and (re)creation of decorative patterns also comes from Tombos (Smith and Buzon Citation2017, 624).

Beyond entanglements, one’s ability to consume objects produced distinction and power relations, as well as marginalization. Objects such as shabtis and canopic jars were restricted to local elites at temple-towns (Lemos Citation2020). People at those places were able to consume material culture to a greater extent and therefore create distinction. The active handling of Egyptian-style material culture allowed people to create local power and distinction within Nubia, but the local nature of adaptations and uses of such objects would further reinforce colonized communities’ place at the bottom of global hierarchies, therefore emphasizing their marginal social position in relation to colonizers.

In non-elite contexts characterized by scarcity and more extensive allodoxic consumption patterns, structural constraints would have largely prevented people from consuming, and therefore partake in cultural entanglements. However, evidence from non-elite cemeteries and places in the periphery of major colonial centers help us to unveil further social aspects of cultural interactions leading, on the one hand, to local power and alternative practices and, on the other hand, marginalization. Non-elite groups living in or in the vicinity of colonial centers, or groups inhabiting peripheral areas marked by material scarcity would have to find creative alternatives to participate in power negotiations through access to imposed Egyptian-style objects.

The cemetery of Fadrus in Lower Nubia was a large non-elite colonial cemetery mostly composed by poor graves. Almost 700 graves dating to the first half of the 18th dynasty (c. 1550–1295 BCE) were excavated at the site, which was probably associated with a significant settlement lost due to a changing river. The proximity of the cemetery to the tombs of two local rulers suggests its association with a settlement (Säve-Söderbergh and Troy Citation1991). Most of the graves excavated at Fadrus contained no burials goods or a few pottery vessels (Spence Citation2019, 548).

Heart scarabs were among the most restricted object types in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. At the cemetery of Fadrus, a single heart scarab was excavated. It comes from the cemetery’s largest collective tomb, where individuals seem to have shared the social and ritual efficacy of a restricted object out of range for most people buried at the cemetery (Lemos Citation2021). This reflects alternative social logics not fully suppressed by colonization in some contexts, namely communal engagement (DeMarrais and Earle Citation2017), which might be linked to social realities that characterized material experiences across Nubia before colonization, especially amid non-elite groups and contexts outside major sites (Manzo Citation2017, 137; Gatto Citation2019, 284; Spencer Citation2019, 448–449).

Similar to non-elite contexts, which have remained largely in the shadow of perceptions of material culture in elite contexts, evidence from colonial ‘peripheries’ – marginal areas within the already marginal colony – remains mostly unexplored, despite substantial surveys and excavations carried out along the Middle Nile, which produced large amounts of information (Edwards Citation2020). Recent fieldwork identified additional sites in the region from Attab to Ferka in north Sudan, and further excavations in the area are expected to contribute to expand our knowledge of so-called peripheries in the Nubian colony and potential alternative social logics operating in these areas (Budka Citation2020, 62).

Data sets produced by earlier surveys in peripheral areas such as the Batn el-Hajar allow us to catch glimpses of alternative social logics, possibly originating from previous local communal arrangements not drastically changed by colonization in geographical peripheries and social spaces. A comparison of contexts such as Fadrus tomb 511 and contexts located in peripheral areas would support such an interpretation.

Chamber tomb 5-T-32 was among the sites excavated by the West Bank Survey from Faras to Gemai in Lower Nubia (). It consisted of a shallow mudbrick tomb divided in three parts: 1) an entrance area leading via an unblocked arched doorway to (2) an outer chamber or chapel; (3) a sealed arched doorway leading to the burial chamber. The tomb was located in the periphery of Mirgissa, one of the earlier fortresses reoccupied in the New Kingdom colonial period and was plundered in ancient times. The tomb dates to the mid-18th dynasty according to pottery and other finds, although its chronology needs to be refined in the future based on comparative research. A few sherds and scattered bone pieces were found in the outer chamber as remains of plundering. The fact that no burials were placed in the outer chamber distinguishes tomb 5-T-32 from tombs at elite cemeteries associated with centers of colonial administration, such as nearby Aniba (Näser Citation2017). The remains of 38 individuals were recovered from the burial chamber, eleven of which were found in situ. The bodies were deposited in an extended position, and the remains of wood and rope suggest the existence of simpler mat coffins tied with ropes, which also appear in non-elite contexts at Tombos (Smith and Buzon Citation2017: ). Finds include five steatite scarabs bearing inscriptions/symbols with parallels found at various Nubian cemeteries, New Kingdom pottery including a pilgrim flask, and a bronze finger ring and wooden headrest, which were more restricted objects in the Nubian mortuary landscape in the New Kingdom (Lemos Citation2020, 15).

Figure 6. Plan and part of the burial assemblage of 5-T-32 (Nordström Citation2014, 135–137; plates 32–33, courtesy of H.-Å. Nordström).

Another noteworthy example, from the periphery of Amara West, was excavated at Ginis West (). The late New Kingdom tomb 3-P-50 comprises a descending passage leading to an outer chamber connected with three burial chambers. It was cut in the intersection of the alluvial plain and bedrock, with a few supporting slabs used to reinforce the tomb’s structure. Scattered bones were found in the descending passage and chamber 3, which attest for the plundering of the site. The tomb likely housed the burials of various contemporaneous individuals and later burials. Recent fieldwork in the area detected what might be traces of a tumulus superstructure (). Four examples of Egyptian-style underground chambers combined with Nubian-style tumulus superstructures have been excavated at Amara West and Tombos (Binder Citation2014, 44; Smith Citation2003, 200), with at least three other examples found at Serra East (Williams Citation1993, 151 passim).

Figure 7. Plan and part of burial assemblage of tomb 3-P-50 at Ginis West (drawing by S. Neumann after Vila Citation1977, 146, 151).

The burial assemblage of tomb 3-P-50 includes figurative scarabs, pendants representing deities and animals, including a rare crocodile pendant, an equally rare wooden headrest, and two late 19th dynasty (1295–1186 BCE) shabtis of Isis, lady of the house. Various types of beads were also excavated, including long beads and spacers, which are characteristic of elite cemeteries. Various earrings made of shell and carnelian were also found, which represent affinities with local styles (Lemos Citation2020, 12–13).

Both tombs 5-T-32 and 3-P-50 are located in peripheral areas (around Mirgissa and Amara West, respectively) and were used collectively. They cover a large chronological span, from the mid-18th dynasty (5-T-32) to the late New Kingdom (3-P-50), and their collective use suggests an important structuring aspect of the mortuary landscape in New Kingdom colonial Nubia. The tombs are not part of formal cemeteries as is the case with most of the studied burial evidence from New Kingdom colonial Nubia. In the areas where both tombs are located, several scattered burials with very few associated finds were detected, which represent a challenge to the interpretation of peripheral areas (Edwards Citation2020, 396–397).

In these areas, one would expect to find untouched or little affected local customs ignored by a colonial enterprise centered at temple-towns. However, similar to non-elite contexts, imposed colonial structures turned Egyptian-style material culture into effective negotiation tools in colonial contexts. Moreover, the peripheral areas where tombs 5-T-32 and 3-P-50 are located can be characterized by an overall material scarcity, as evidenced by the intact, though badly preserved cemetery 11-L-22 in the periphery of the reoccupied fortress of Askut. The small cemetery is thought to have comprised c. 12 graves, though the excavators suggested that it could be considerably larger. The graves were simple pits, similar to the majority of graves at Fadrus, and contained few or no grave goods (Edwards Citation2020, 60–66).

Following Lemos’ suggestion that collective engagement played an important role in the shaping of non-elite experiences of colonization in New Kingdom Nubia, based on evidence from Fadrus (Lemos Citation2021), collective tombs in peripheral zones allow us to identify communal social logics that would also work as alternatives to colonization. In contexts characterized by larger material limitations, where cultural entanglements play a considerably small role due to a lack of consumption, collective engagement theory helps us to unveil communities’ alternatives to participate in contextual negotiations of positions and identities dictated by Egyptian-style objects in a colonial situation. In this sense, peripheries should be understood in a fluid way to become centers of material experiences of colonization in ancient Nubia (see Bebemeier et al. Citation2016; Sulas and Pikirayi Citation2020). However, at the same time, these experiences exemplify what geographer Milton Santos named ‘experience of scarcity’; i.e. the incapacity of those ‘from below’ to partake in mainstream negotiations through consumption, which results in alternative social realities and experiences of scarcity (e.g. solidarity) from within and which become typical of those marginalized contexts (Santos Citation2001, 144–145).

Conclusion: marginal realities in colonized Nubia

A material culture perspective to the Egyptian colonization of Nubia in the New Kingdom allows us to unveil alternative social realities within the colony, therefore contributing to the acknowledgement of the fact that there was no single ‘Nubian’ cultural input to interactions, but rather various hierarchical local inputs determined by communities’ ability to consume or, in some areas, material scarcity, both of which could result in marginalization (Lemos Citation2020, 20).

An Egyptian-style objectscape flooded Nubia as material support of ancient Egyptian colonization in the region. Rather than reaching ‘Nubia’ in a context of increasing interactions with ‘Egypt’, flows of Egyptian-style objects reached different local communities inhabiting distinctive social and geographical spaces in Nubia. There is considerable overlap between these spaces, for example, the overall material scarcity of peripheral zones, such as the Batn el-Hajar, and non-elite cemeteries located in more populated areas, such as Fadrus. In a context where ‘standardizing mass-produced objects were especially prone to being used in distinctive combinations as part of objectscapes associated with enacting certain social tasks’ (Pitts Citation2019, 13), both geographical peripheries and non-elite social spaces in more populated areas yield innovation resulting from communities’ experiences of scarcity, which result in alternative practices to colonial norms that further reinforce these groups’ placement at the margins of colonial society.

The social impacts of cultural contacts affects at least three distinct levels of Nubian society. The first comprises temple-towns’ entanglements through consumption, which allow elite individuals to establish cultural affinities with Egypt by displaying local power through individual use of Egyptian-style burial assemblages; e.g. Khnummose. The second level comprises large non-elite cemeteries or non-elite graves associated with temple-towns, where consumption was possible, but in a more limited way. In these contexts, allodoxic consumption led to the creation or reinforcement of alternative social logics (i.e. communal ethos) that challenged colonization on a contextual basis (e.g. the collective use of a heart scarab at Fadrus). The third level consists of isolated geographical peripheries characterized by overall scarcity. Similarly to non-elite social spaces in general, these contexts were characterized by limited allodoxic consumption, which reinforced communal ethos based on communities’ experiences of scarcity.

In all three cases, colonialism, one the hand, triggers creativity; on the other hand, it produces marginalization. First, local elites’ adaptation of foreign objects did not always match original meanings, which created global marginalization of the colonized in relation to the colonizer, for example, later patterns added onto earlier imported shabtis or the transformations of ordinary vessels into ritually effective canopic jars in local contexts. Second, in a context of scarcity, people’s creative ways to attain access to restricted foreign objects would eventually subvert their original individual meaning, creating both global and local marginalization. For instance, the collective use of heart scarabs, which were originally associated with a specific individual whose name/title would be carved onto these objects. A better understanding of the nature of social relationships in non-elite social spaces and geographical peripheries depends on further research and fieldwork in Sudan.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rennan Lemos

Rennan Lemos is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at LMU Munich, where he works for the ERC DiverseNile Project.

Julia Budka

Julia Budka is Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Art History at LMU Munich, where she is the Principal Investigator of the ERC DiverseNile project.

References

- Bebemeier, W. et al. 2016. “Ancient Colonization of Marginal Habitats. A Comparative Analysis of Case Studies from the Old World.” eTopoi: Journal for Ancient Studies 6: 1–44.

- Binder, M. 2014. “Health and Diet in Upper Nubia through Climate and Political Change. A Bioarchaeological Investigation of Health and Living Conditions at Ancient Amara West between 1300 and 800 BC.” PhD thesis, Durham University.

- Bourdieu, P. 1984. Distinction. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. 1985. “The Social Space and the Genesis of Groups.” Theory and Society 14 (6): 723–744. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00174048.

- Budka, J., and F. Doyen. 2013. “Life in New Kingdom Towns in Upper Nubia – New Evidence from Recent Excavations on Sai Island.” Ägypten und Levante 22: 167–208.

- Budka, J. 2020. “Kerma Presence at Ginis East: The 2020 Season of the Munich University Attab to Ferka Survey Project.” Sudan & Nubia 24: 57–71.

- Budka, J. 2021. Tomb 26 on Sai Island: A New Kingdom Elite Tomb and Its Relevance for Sai and Beyond (with contributions by J. Auenmüller, C. Geiger, R. Lemos, A. Stadlmayr and M. Wohlschlager). Leiden: Sidestone Press.

- Buzon, M., A. Simonetti, and R. A. Creaser. 2007. “Migration in the Nile Valley during the New Kingdom Period: A Preliminary Strontium Isotope Study.” Journal of Archaeological Science 34 (9): 1391–1401. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.029.

- Cooper, J. 2021. “Between the Nile and the Red Sea: Medjay Desert Polities in the Third to First Millennium BCE.” Old World: Journal of Ancient Africa and Eurasia 1 (1): 1–22.

- Davies, N., and A. Gardiner. 1926. The Tomb of Huy: Viceroy of Nubia in the Reign of Tutankhamun. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- DeMarrais, E., and T. Earle. 2017. “Collective Action Theory and the Dynamics of Complex Societies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 46 (1): 183–201. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-102116-041409.

- Dietler, M. 2010. Archaeologies of Colonialism: Consumption, Entanglement, and Violence in Ancient Mediterranean France. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Edwards, D. 2004. The Nubian Past. London: Routledge.

- Edwards, D. 2020. The Archaeological Survey of Sudanese Nubia, 1963–69. The Pharaonic Sites, ed. D. Edwards. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Gatto, M. C. 2019. “The Later Prehistory of Nubia in Its Interregional Setting.” In Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by D. Raue, 259–292. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Kemp, B. J. 2018. Ancient Egypt: Anatomy of a Civilization. 3rd ed. London: Routledge.

- Kemp, B. J. 1972. “Fortified Towns in Nubia.” In Man, Settlement and Urbanism, edited by P. Ucko, 657–680. London: Duckworth.

- Klemm, D., and R. Klemm. 2013. Gold and Gold Mining in Ancient Egypt and Nubia. New York: Springer.

- Lemos, R. 2021. “Heart Scarabs and Other Heart-Related Objects in New Kingdom Nubia.” Sudan & Nubia 25. In press.

- Lemos, R. 2020. “Material Culture and Colonization in Ancient Nubia: Evidence from the New Kingdom Cemeteries.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by, C. Smith. Cham: Springer. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-51726-1_3307-2.

- Lemos, R. 2018. “Materiality and Cultural Reproduction in Non-Elite Cemeteries.” In Perspectives on Materiality in Ancient Egypt: Agency, Cultural Reproduction and Change, edited by É. Maynart, C. Velloza, and R. Lemos, 24–34. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Manzo, A. 2017. “Architecture, Power, and Communication: Case Studies from Ancient Nubia.” African Archaeological Review 34 (1): 121–143. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10437-016-9239-6.

- Minault-Gout, A., and F. Thill. 2012. Saï II. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale.

- Müller, I. 2013. Die Verwaltung Nubiens im Neuen Reich. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Näser, C. 2017. “Structures and Realities of the Egyptian Presence in Lower Nubia from the Middle Kingdom to the New Kingdom.” In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions, edited by N. Spencer, A. Stevens, and M. Binder, 557–574. Leuven: Peeters.

- Nördström, H.-Å. 2014. The West Bank Survey from Faras to Gemai. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- O’Connor, D. 1993. Ancient Nubia: Egypt’s Rival in Africa. Philadelphia: University Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- Paner, H., and A. Pudło. 2010. “Settlements in the Fourth Cataract GAME Concession in the Light of Radiocarbon Analysis.” Gdansk Archaeological Museum African Reports 7: 131–146.

- Pitts, M., and M. J. Versluys. 2021. “Objectscapes: A Manifesto for Investigating the Impacts of Object Flows on past Societies.” Antiquity 95 (380): 367–381. doi:https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2020.148.

- Pitts, M. 2019. The Roman Object Revolution: Objectscapes and Intra-Cultural Connectivity in Northwest Europe. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

- Reisner, G. 1910. The Archaeological Survey of Nubia. Report for 1907– 1908. Cairo: National Printing Department.

- Retzmann, A., J. Budka, H. Sattmann, J. Irrgeher, and T. Prohaska. 2019. “The New Kingdom Population on Sai Island: Application of Sr Isotopes to Investigate Cultural Entanglement in Ancient Nubia.” Ägypten und Levante 29: 355–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1553/AEundL29s355.

- Richards, J. 2005. Society and Death in Ancient Egypt: Mortuary Landscapes of the Middle Kingdom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sadr, K. 2017 [1991]. The Development of Nomadism in Ancient Northeast Africa. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Santos, M. 2001. Por uma outra globalização: do pensamento único à consciência universal. 6th ed. Rio de Janeiro: Record.

- Säve-Söderbergh, T., and L. Troy. 1991. New Kingdom Pharaonic Sites: The Finds and the Sites. Partille: Paul Åström.

- Säve-Söderbergh, T. 1989. Middle Nubian Sites. Partille: Paul Åström.

- Simpson, W. K. 1963. Heka-Nefer and the Dynastic Material from Toshka and Armina. New Haven: Peabody Museum of Natural History of Yale University.

- Smith, S. T., and M. Buzon. 2017. “Colonial Encounters at New Kingdom Tombos: Cultural Entanglement and Hybrid Identity.” In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions, edited by N. Spencer, A. Stevens, and M. Binder, 615–630. Leuven: Peeters.

- Smith, S. T. 1992. “Intact Theban Tombs and the New Kingdom Burial Assemblage.” Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts Abteilung Kairo 48: 193–231.

- Smith, S. T. 1995. Askut in Nubia: The Economics and Ideology of Egyptian Imperialism in the Second Millennium BC. London: Kegan Paul International.

- Smith, S. T. 2003. Wretched Kush: Ethnic Identities and Boundaries in Egypt’s Nubian Empire. London: Routledge.

- Smith, S. T. 2020. “The Nubian Experience of the Egyptian Domination during the New Kingdom.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by G. Emberling and B. Williams, 369–394. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, S. T. 2018. “Gift of the Nile? Climate Change, the Origins of Egyptian Civilization and Its Interactions within Northeast Africa.” In Across the Mediterranean – Along the Nile: Studies in Egyptology, Nubiology and Late Antiquity Dedicated to László Török, edited by T. A. Bács, Á. Bollók, and T. Vida, 325–346. Vol. 1. Budapest: Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

- Spence, K. 2019. “New Kingdom Tombs in Lower and Upper Nubia.” In Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by D. Raue, 541–566. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Spencer, N., A. Stevens, and M. Binder, eds. 2017b. Amara West: Living in Egyptian Nubia. London: British Museum.

- Spencer, N., A. Stevens, and M. Binder. 2017a. “Introduction: History and Historiography of a Colonial Entanglement, and the Shaping of New Archaeologies for Nubia in the New Kingdom.” In Nubia in the New Kingdom: Lived Experience, Pharaonic Control and Indigenous Traditions, edited by N. Spencer, A. Stevens, and M. Binder, 1–61. Leuven: Peeters.

- Spencer, N. 2019. “Settlements of the Second Intermediate Period and New Kingdom.” In Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by D. Raue, 433–464. Berlin: De Gruyter.

- Steindorff, G. 1937. Aniba II. Glückstadt: J.J. Agustin.

- Sulas, F., and I. Pikirayi. 2020. “From Centre-Periphery Models to Textured Urban Landscapes: Comparative Perspectives from Sub-Saharan Africa.” Journal of Urban Archaeology 1: 67–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1484/J.JUA.5.120910.

- van Pelt, W. P. 2013. “Revising Egypto-Nubian Relations in New Kingdom Lower Nubia: From Egyptianization to Cultural Entanglement.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 23 (3): 523–550. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774313000528.

- Vila, A. 1977. La Prospection Archéologique de la Vallée du Nil au Sud de la Cataracte de Dal (Nubie Sudanaise). Paris: CNRS.

- Williams, B., and G. Emberling. 2020. “Nubia: A Brief Introduction.” In The Oxford Handbook of Ancient Nubia, edited by G. Emberling and B. Williams, 1–4. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Williams, B. 1993. Excavations at Serra East, Parts 1-5: A-Group, C-Group, Pan Grave, New Kingdom, and X-Group Remains from Cemeteries A-G and Rock Shelters. Chicago: Oriental Institute.