ABSTRACT

The article proposes a new interpretation of Chalcolithic and early Bronze Age warrior graves grounded in the ‘Rinaldone’ burial tradition of central Italy, 4th and 3rd millennia BC. In European archaeology, warrior graves are frequently thought to signal the rise of sociopolitical inequality rooted in metal wealth. The work questions the empirical and conceptual foundations of this reading, arguing that, in early Europe, copper was not as rare and valuable as it is often presumed to be; that metalworking did not demand uniquely complex skills; and that metal-rich burials cannot be interpreted in light of modernising ideas of identity. It is argued instead that the key to decoding prehistoric warrior graves lies in context-specific notions of gender, age, and the life course. In particular, life and death circumstances including violence (both inflicted and suffered) would determine why certain individuals were laid to rest with lavish weapon assemblages.

Introduction

To the archaeological imagination, the Chalcolithic (or Copper Age) and early Bronze Age are the times when social inequality first arose in Europe. Central to this narrative are two techno-cultural innovations dating to this period: metalworking and weapon-rich individual male burials, or ‘warrior graves’. The link between the two is not merely conceptual, for metals – copper-alloy daggers being conspicuous among them – are often found in early warrior burials, for instance in 4th millennium BC Maikop culture and 3rd millennium BC Bell Beaker funerary tradition (Hansen Citation2013; Vander Linden Citation2006a). Both innovations testify to a profound transformation in the way prehistoric society conceptualised the relationship between technology and the human body, creating a material language that articulated new forms of identity and, for many, new power relations.

It is frequently suggested that the metal and non-metal weapons furnishing warrior graves indicate that the deceased was invested in life with political authority. Drawing on an analogy with historic Polynesian chiefs and Papua New Guinea Big Men, some authors posited that these dead were prehistoric chieftains who had achieved power by controlling the exchange and consumption of metals and other prestige goods (Clarke, Cowie, and Foxon Citation1985; Shennan Citation1982; Thorpe and Richards Citation1984). Others maintained that they were the forerunners of a Bronze Age social archetype: the ‘warrior-hero’ (Hansen Citation2013; Jeunesse Citation2014; Treherne Citation1995). According to this interpretation, successful warriors would be interred with the trappings of their martial personas, creating a potent blueprint for peer emulation which led to the rise of Bronze Age elite identities (Horn and Kristiansen Citation2018; Kristiansen Citation1999; Vandkilde Citation2006, Citation2018). Yet other authors forcefully contested both readings, noting that interpretations of this kind are predicated upon unspoken modernist assumptions regarding gender, value, and personhood (Brück Citation2004; Brück and Fontijn Citation2013; Fowler Citation2004, Citation2013). For all, however, the entangled material and bodily technologies displayed in these burials are informative about epoch-defining changes in sociopolitical structures and/or belief systems ushering in the Bronze Age world.

In the last two decades, the debate over Chalcolithic and early Bronze Age warrior graves has somewhat shifted from an early focus on metals and prestige goods as sources of chiefly power towards the examination of funerary practices and ideas of the person. This has created fresh – and partly yet unexplored – opportunities to re-examine the relationship between metallurgy, power, and identity. Furthermore, research has historically focused on continental Europe and the British Isles (but see Jeunesse Citation2014; Vander Linden Citation2006b for notable exceptions). This is unfortunate considering that Mediterranean Europe has no shortage of weapon burials, and its prehistoric societies exhibit distinctive funerary dynamics worth exploring. In Copper Age Italy (c.3650–2200 BC), for example, mortuary practices featured both individual and collective interment in non-monumentalised chambers, not a wholesale shift from monumental/collective to non-monumental/individual burial as in Europe’s north-western fringes (Dolfini Citation2015, Citation2020). Differences such as this provide opportunities to enrich the debate, adding important evidence that predates the appearance of warrior graves (and copper metallurgy) in most of western Europe.

In this paper, I shall reassess warrior graves from the standpoint of the so-called Rinaldone culture, a Copper Age funerary tradition from central Italy. I shall briefly review the history of research into European weapon-rich burials; present the Italian evidence relative to Rinaldone and Casetta Mistici, two well-studied funerary sites (Anzidei and Carboni Citation2020; Dolfini Citation2004); critique current interpretations; and propose a new reading of warrior graves that significantly contributes to the broader debate about metals, power, and identity in prehistoric Europe.

Metals, burial and power in prehistoric Europe: a brief review

For most of the 20th century, the emergence of warrior burials in 5th to 3rd millennia BC Europe was tied to diffusionist narratives arguing for the arrival of new peoples from the Eurasian steppes. Early prehistorians saw in the newcomers the bearers of superior metal weapons that enabled them to subjugate the peaceful agrarian communities of Neolithic Europe (Gimbutas Citation1977; Laviosa Zambotti Citation1943; Peet Citation1909; Puglisi Citation1959).

From the 1970s, migrationist narratives were progressively replaced by processual models claiming that the spread of warrior graves was due to competitive display and conspicuous consumption among emerging elites. The change in theoretical approach is best exemplified by Renfrew’s seminal study of early Bronze Age ‘Wessex culture’, southwest Britain (Renfrew Citation1973, Citation1974). Renfrew claimed that changes in burial behaviour were rooted in a new kind of social organisation in which power was increasingly concentrated in the hands of chiefs. In his view, metal-rich Wessex burials would signify that Neolithic group-oriented chiefdoms had been replaced by individualising rank societies, in which elite power had become institutionalised.

Building on Renfrew, Thorpe and Richards (Citation1984) maintained that late Neolithic Europe was swept by profound changes in the nature of social relations. These entailed the replacement of large-scale collective rituals centring on competitive consumption with individualising forms of prestige exemplified by weaponry and other prized personal possessions. Their views were echoed by several authors active through the 1980s (e.g. Bradley Citation1984; Bradley and Chapman Citation1986; Braithwaite Citation1984; Shennan Citation1982, Citation1986). Contesting these studies’ focus on elite interaction, Barrett (Citation1994) and Thomas (Citation1991, Citation1999) stressed that 3rd millennium changes in social relations were mediated by a new emphasis on individual inhumation, away from the notion of collective ancestry typical of Neolithic Britain. Vander Linden (Citation2006a, Citation2006b, Citation2007) proposed similar interpretations for continental Beaker burials. Overall, these works ushered in a new season of theoretically oriented research on body and identity that continues to this day.

Brück (Citation2004, Citation2006) and Fowler (Citation2004, Citation2005), among others, questioned the notion that individual burials would signify individualised persons, and burials with rich and exotic furnishings would equate with self-aggrandisers seeking social elevation. Both authors pointed out that such interpretations are predicated upon a concept of the individual as a monadic entity, who exists prior to the social relations in which he or she participates. Fowler (Citation2013, Citation2017), in particular, argued that prehistoric personhood may not ‘end at the skin’, but may subsume into itself multiple bodies, objects, and relations, as it does in many non-Western societies. In a similar vein, Jones (Citation2002) doubted that grave goods were personal possessions endowed with a purely material value. Goods, he reasoned, might instead have a biographical value evoking significant places, events and relations worth remembering. Brück and Fontijn (Citation2013) further discussed the relational nature of prehistoric identities and mortuary practices, and so recently did Brück (Citation2019). For these authors, warrior graves and other furnished individual burials are indeed rich, but the currency is social rather than material.

In a late interpretive twist, ancient DNA studies have brought back into fashion migrationist narratives that archaeologists had long consigned to the history of their discipline. Recent whole-genomic sequencing of Corded Ware and Bell Beaker warrior (and non-warrior) burials has highlighted previously unsuspected instances of population admixture and replacement in 3rd millennium BC Europe (Allentoft et al. Citation2015; Haak et al. Citation2015; Olalde et al. Citation2018, Citation2019). The ‘Yamnaya culture’ of the Pontic-Caspian steppes is seen as the prime mover of a major migratory event that is controversially tied to the rise of a male-centred kin structure and ideology, the spread of copper metallurgy, and the diffusion of Indo-European languages (Kristiansen et al. Citation2017). The proposal has generated a heated debate that cannot be reviewed here. Suffice it to note its problematic conflation of biological populations, material assemblages and languages, as well as its essentialising approach to identity that denies decades of theoretically oriented scholarship (Crellin and Harris Citation2020; Furholt Citation2018, Citation2019; see also World Archaeology 51(4), “Ancient DNA Research: Blessing or Curse for Archaeology?”). One should also note that warrior graves first appeared in eastern Europe in the 5th millennium BC, well before the ‘Yamnaya migration’ (Chapman Citation1999; Jeunesse Citation2014; Vandkilde Citation2006).

Warrior graves à la Rinaldone

In Italy, warrior graves are first documented in the mid-4th millennium BC as part of the ‘Rinaldone culture’, a Copper Age funerary custom that emerged out of late Neolithic transformations in burial behaviour. These entailed a clear-cut separation of the dead from the living; the establishment of extramural cemeteries to carry out funerals and ancestor veneration rituals; increasingly elaborate mortuary rites, which featured higher rates of manipulation and circulation of human remains than previously; and a new focus on gender and age as expressed by normative grave sets (Dolfini Citation2015, Citation2020; Robb Citation2007).

Rinaldone-style cemeteries are found on either side of the Apennines range in central Italy. They normally consist of clusters (or alignments) of small, low-vaulted underground chamber graves closed by stone or wooden slabs. Access to the graves was through entrance shafts or short corridors (the latter preferred for graves cut into hill slopes and river banks). Each grave habitually contained one to ten burials of all gender and age groups, either whole/articulated or incomplete/reorganised, and often both. Infants are underrepresented at most sites.

The burial programme comprised three principal steps: (1) interment of a fleshed (and often furnished) body, either crouched on one side or lying on its back, legs flexed sideways; (2) manipulation of the dry bones, which were removed, partly or totally, from the grave and seemingly circulated among the living; and (3) reburial of selected remains (often skulls and long bones), which were either added to pre-existing bone stacks or placed upon, or next to, other burials (including articulated ones; ). Heightened ritual activity marked the second and third step of the burial process. Ritual behaviour can be discerned in the food/drink and goods offerings frequently found in the burial chambers (especially alongside disarticulated burials) and entrance shafts or corridors (Carboni and Anzidei Citation2020; Dolfini Citation2015). While the tripartite schema outlined above applies to most cemeteries, different sites may display different burial behaviours, with some primarily hosting unfurnished reorganised burials and others well-furnished individual interments.

Table 1. Synopsis of the three-step funerary process deployed at Rinaldone-style burial sites. Not all steps of the process were always carried out. For instance, bodies may be left articulated in the grave with their furnishings beside them (after Dolfini Citation2015)

Normative object sets often accompanied individual burials. Adult males received copper-alloy, hardstone and flint weapons including daggers, axe-hammers and maceheads (bone spearheads are common in east-central Italy). Women and children were given beads and pendants made from silver, antimony, and steatite (or other soft stones), as well as flint blades/scrapers and small sets of arrowheads. Copper awls were placed with all gender and age groups, and so were burnished ceramic flasks containing an intoxicating drink akin to mead (Carboni et al. Citation2020).

Two sites stand out for their unusually high number of warrior graves and other individual burials: Rinaldone (the type-site of this burial tradition) and Casetta Mistici (). Rinaldone was discovered in the early 20th century near Lake Bolsena (Colini Citation1903; Pernier Citation1905; see Dolfini Citation2004 for a synthesis). It comprises 16 chamber graves split into two clusters (graves 1–13 and 14–16), which were accessed through short corridors facing south or southwest. Graves 1–5, 8 and 15 yielded one articulated burial each (plus reorganised remains in grave 8). The burials were furnished with weapon sets meaningfully placed next to specific body parts. Axe-hammers and daggers lay near the head of the deceased (graves 4, 8 and 15), maceheads near the chest (graves 4 and 5), and arrowheads near the forearms and legs (). These are some of the most lavishly equipped burials from Copper Age Italy. Grave 3, for example, contained six copper-alloy objects, two stone maceheads, 22 flint arrowheads and a ceramic flask (). Object typology dates all warrior burials to the early Copper Age, c.3650–3350 BCFootnote1 (Iaia and Dolfini Citationin press).

Table 2. Burials and grave goods from Rinaldone, Viterbo. The softstone axes and axe-hammers from graves 2, 4 and 5 are skeumorphs of functional hardstone objects (data after Dolfini Citation2004)

Figure 1. Map of central Italy showing the sites mentioned in the article. 1: Rinaldone; 2: Casetta Mistici; 3: Ponte San Pietro; 4: Fontenoce di Recanati; 5: Marcellina-Vasoli; 6: Lunghezzina. Hollow circles: modern cities (base map: Ancient World Mapping Center).

Figure 2. Rinaldone, grave 3: object assemblage (photograph reproduced by courtesy of the Museo delle Civiltà, Rome; © MuCiv-MPE ‘L. Pigorini’).

Not all burials from Rinaldone are equally impressive, however. Grave 14 (containing two organised individuals) yielded a paltry four arrowheads. Grave 11 returned disarticulated remains belonging to an indeterminate number of bodies, along with eight arrowheads and a few potsherds. Graves 6–7, 9–10 and 12 apparently contained no human remains. Interestingly, some of the empty graves did contain objects, namely four arrowheads in grave 7 and an axe-hammer in grave 9. While the site’s acidic soil had damaged the human remains (to the point that they were not kept; sex and age of the deceased are thus unknown), the excavators were normally able to identify burials when present. It is therefore likely that these objects had been placed as offerings in empty graves, or had been left in situ upon removing previously interred remains and, quite possibly, other goods (Dolfini Citation2004).

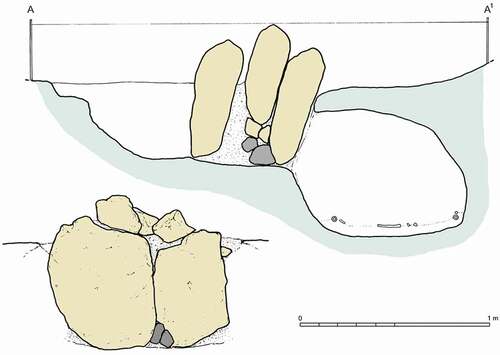

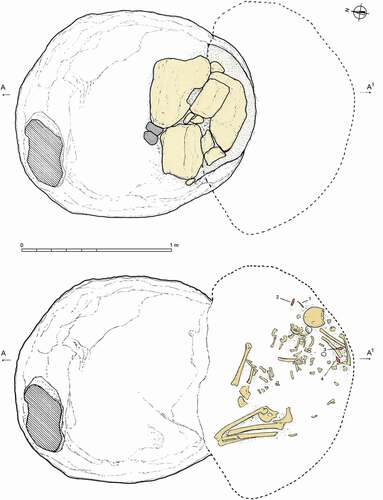

Casetta Mistici is a small cemetery recently discovered in the outskirts of Rome. It comprises seven underground chamber graves (1–3, 6–8 and 10) and two trench graves (5 and 9). The chamber graves are arranged in a tight cluster with entrances facing south, east or north. They are all accessed through round or elliptical shafts and are sealed by stone slabs (). Radiocarbon indicates that the chamber burials date to c.3650–3350 BC overall, except for a body that was added to grave 6 somewhat later. Trench grave 9 was dug above chamber grave 10 (probably intentionally) in 3540–3350 BC (LTL4805A; 4671 ± 50 BP), while trench grave 5 was sunk into the collapsed vault of grave 6 in the early 3rd millennium BC (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020).

Figure 3. Casetta Mistici, plan of the cemetery. Trench graves 5 and 9 intersect chamber graves 2, 6 and 10 (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020).

Both chamber and trench graves hosted an articulated burial each except for grave 6, which had two. Graves 1–5 contained children below the age of 12; they were given no objects apart from the grave 2 burial, which had a copper awl, two softstone beads and a pendant made from the fang of a large canid, possibly a wolf. Grave 7 hosted a woman aged 40–49 whose cultural materials encompassed a copper awl, a short flint blade, two arrowheads, and two pottery fragments. She shows a perimortem blunt-force trauma to her parietal bone, probably inflicted by a macehead. All other burials belong to adult males, defined in this context as anyone older than 11/12 years of age (Dolfini Citation2006). The two burials from grave 6 are aged 13–19 years, while the one from grave 10 is 20–29 and those from graves 8 and 9 are both 30–39. They are all furnished with rich weapon sets (). The grave 8 burial is the most impressive (and unusual) of all. It comprises five metal objects including a Levantine-type axe that is otherwise undocumented in Italy; a finely knapped bifacial dagger; a long, skilfully made flint knife; ten arrowheads; and a bone awl or punch (). Lead isotope analysis tentatively supports the non-local origin of the Levantine axe (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020; Aurisicchio and Medeghini Citation2020).

Table 3. Burials and grave goods from Casetta Mistici, Rome. Grave number 4 was not assigned; graves 5* and 9* are trench graves; grave 6 yielded two organised burials whose heads were later moved by the mourners to the north-west corner of the chamber; in grave 10, one of the copper-alloy axes was deposited at a later stage, when sediment had already covered the burial and goods (Data after Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020)

Figure 4. Casetta Mistici, grave 8 furnishings (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020).

Figure 5. Casetta Mistici, grave 7. (a) Plan of the burial chamber and entrance shaft, before and after excavation. (b) Cross-section of the burial chamber and shaft and view of the stone slabs sealing the chamber. The chamber contained an articulated woman who had died a violent death (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020).

Warrior graves are not unique to Rinaldone and Casetta Mistici; they are found in small numbers throughout west-central Italy, either isolated (e.g. Marcellina-Vasoli) or within wider cemeteries (e.g. Ponte San Pietro, graves 20–21; and Lunghezzina, grave 4; see Carboni Citation2020; Dolfini Citation2004 for review). In east-central Italy, Fontenoce di Recanati has yielded several such burials, though metals are rare (Silvestrini and Pignocchi Citation1997, Citation2000). Most warrior graves date to the mid/late 4th millennium BC (Carboni Citation2020, Figs. 5.1.3-5; Iaia and Dolfini Citationin press). This is a relatively short-lived horizon marking the birth of a new material language and of new notions of male identity and, for some, male power.

Metals and chiefly power in Italian warrior graves: the evidence and its limits

In Italy, the interpretation of Rinaldone-style warrior graves has followed the ebb and flow of dominant theoretical paradigms. In the heyday of culture history, Puglisi (Citation1959) saw these burials as evidence of invading warrior-shepherds from the Orient, while Peroni (Citation1971, Citation1989) retorted that they were instead the indigenous forerunners of Bronze Age warring aristocracies. Working within a processual framework, Barker (Citation1981) claimed that these burials would signal the rise of ranked societies, whereas Cazzella (Citation1992, Citation1998, Citation2003) argued that they were ‘Big Men’ who had achieved power through peer competition for metals and other exotica. As leaders could not transfer their elevated status to their offspring – he surmised – their funerals would be marked by acts of conspicuous consumption in which the symbols of their lifetime authority were decommissioned. For Guidi, however, the taboo against power inheritance could occasionally be breached, as demonstrated by lavish child burials indicating ascribed status (Guidi in Cazzella and Guidi Citation2011, 31).

Other authors placed greater emphasis on the politics of resource procurement and land use. Skeates (Citation1995), for example, noted that most cemeteries from east-central Italy lie in fertile alluvial plains and valley bottoms. This would suggest that Copper Age elites deployed burial as a corporate strategy to claim control over valuable farmland and pastures. From a social constructivist perspective, Robb (Citation1999, Citation2007) examined the role of material culture in naturalising disparate forms of power and prestige. He posited that, in Neolithic Italy, pre-eminence could only be achieved in specific realms of action. One could be a religious leader, a master potter, or a fearsome warrior, but not all of them at once, for these roles and identities were not commensurable. In the Copper Age, however, ambitious men could accumulate reputation and power by excelling in multiple social domains. This would be made possible by the new gender ideology gaining ground at this time.

Dolfini (Citation2004, Citation2006) examined the relationship between mortuary behaviour, material culture and rank. He noted that (a) a select few men (and some women and children) were given one-step funerals, while most deceased went through the multi-step burial process described above; (b) while multi-step funerals caused most deceased to lose their individual identities, a select few would have it preserved (and reinforced) through one-step funerals; and (c) one-step funerals often involved metals and other rare or exotic objects, while these are rare and inconspicuous in the disarticulated burials resulting from multi-step funerals. He concluded that high-ranking individuals restricted access to one-step funerals to signal status and power.

The common denominator of all these readings lies in assuming that warrior graves would belong to a new class of tribal chiefs who cunningly manipulated burial behaviour, metal technology, and the long-distance exchange of valuables to legitimise their authority. Upon close inspection, however, the data and conceptual frameworks underpinning these readings show notable flaws worth investigating.

A first set of problems concerns the interpretation of Copper Age funerals. It is normally presumed that lavish object assemblages were solely placed with articulated burials during one-step funerals. The presumption overlooks the fact that we do not know what was initially placed with the now-disarticulated burials, for we only see what was left in the grave at the end of multi-step funerals – normally, not much. There are, however, clues that objects may have been placed in most graves as the body was laid to rest, but were later removed when the mourners reopened the grave to extract and manipulate the dry bones ().

Ceramic flasks and bowls are a case in point. They are often whole with articulated burials and fragmented with reorganised burials, the fragments never making up a whole vessel. This suggests that the mourners placed the vessel in the grave at the time of burial (, ‘interment’). When the flesh had decayed, they would reopen the grave, smash the vessel, and circulate its fragments alongside body parts so as to forge enchained relations (sensu Chapman Citation2000) between the living, the newly dead, and the ancestors (, ‘manipulation’). Some fragments were later deposited in burial chambers and shafts/corridors, while others were presumably kept by the mourners (, ‘reburial’). I argue that entire grave sets may have been scattered in this way, with objects being partly kept by the living, partly reinterred, and partly left in the grave after the body’s removal, perhaps as a memento of its former occupant.

Weapons occasionally found, alone or in small scatters, with disarticulated bodies (and in graves with no burials) inform us of this cultural behaviour. The axe-hammer and arrowheads from Rinaldone, graves 7 and 9, offer notable examples (). Casetta Mistici did not yield any such evidence as all burials are articulated. However, commingled burials from other Rinaldone-style sites have returned isolated weapons. Commenting upon the latter, Carboni and Anzidei (Citation2020, 316) note that the objects are always scattered on the grave floors without discernible associations to specific burials. This suggests that the original weapon sets had been broken up and scattered as the body was dismembered.

A second set of problems lies in a tangle of unwarranted ethnographic analogies and modernist assumptions about prehistoric identity that have long plagued the subject, in Italy as much as elsewhere. Political interpretations of warrior graves often rely on Polynesian chiefs and Papua New Guinea Big Men as anthropological models of choice. The analogy is problematic in more ways than one. Some authors have observed that many kinds of societal structures historically coexisted in Highland Papua New Guinea; these comprised both Big Man and Great Man societies, as well as communities showing little appetite for political differentiation (Godelier Citation1986; Godelier and Strathern Citation1991). Others remarked that Polynesian chiefs acquired power and prestige by detaching themselves of their most prized possessions, not accumulating them (Fowler Citation2013, 93). Others still pointed out that, in achievement-based societies, leaders may enjoy a good deal of esteem but little political power; they could cajole, entice and persuade, but seldom could they force their will upon their people (Flannery and Marcus Citation2012, 120). This reminds us that leadership is a nuanced and context-specific notion; indeed, a chief can be many things (Fowler Citation2013, 94).

Furthermore, the equation between warrior graves and political authority rests on the unspoken assumption that prehistoric persons were past incarnations of the modern self. They would consist of neatly bounded bodies that could be discriminated from both other bodies and the material and natural world. It has long been acknowledged, however, that identity and personhood are understood as relational attributes in many non-Western societies (and perhaps in the West, if differently: Hernando Citation2017). In these contexts, people are not conceptualised as self-contained individuals, but as relational (and often partible) beings made up of all the salient social relations they had entered during their lives; such relations may include not only other persons, but also places, objects, animals, and spiritual entities (Brück Citation2019; Fowler Citation2004; Jones Citation2002; Thomas Citation2002, Citation2004). The implication is that, in traditional societies, burials may not contain individuals as such, but bundles of social relations deemed relevant for display in death.

A corollary to this reading is that the most important dead (i.e. those who built the most numerous and meaningful relations, for example respected leaders) might have undergone the most complex and long-lasting funerals, not the least extended. As their lifetime identity had been constituted through myriad social engagements, it would be restructured in death by the handling and exchanging of body parts and objects – a poignant re-enactment of the deceased’s rich social life. In this way, what relations death had severed were reconstituted at the grave side, securing at once society’s survival and the transformation of the newly dead into ancestors.

A third set of problems concerns the relationship between metal technology and power. It is often assumed that, in early Italy (and indeed Europe), metal would be a form of primitive wealth jealously controlled by elite individuals. As a product of limited ore resources, a complex transformative craft, and far-reaching exchange networks, metal would be rare, valuable, and exotic; hence its appropriation by tribal chiefs to naturalise their power. On all accounts, this reading can now be questioned.

Firstly, it is not clear how rare copper might have been in early Italy. While major differences surely existed between communities that dwelt near the mines and those further afield, the latest research suggests that much more copper was mined, traded, and used than we see archaeologically. Even the most conservative calculations of the outputs of prehistoric mines reveal glaring mismatches between what was extracted and what has survived to this day (Pearce Citation2009). The mismatch has a simple explanation: most metal was recycled at the end of its use life (Bray and Pollard Citation2012; Bray et al. Citation2015). Arguably, recycling is responsible for absconding all prehistoric metal artefacts but those intentionally committed to the ground or water. Such a major visibility bias is validated by the use-wear analysis of bone and steatite artefacts from Italian Copper Age domestic sites. The analysis shows that these materials were routinely worked with copper-alloy knives, chisels and drill-points seldom surviving in the record (Cristiani and Alhaique Citation2005; Gernone Citation1998). This proves that ordinary craftspeople must have enjoyed access to humble and relatively widespread metal tools.

Furthermore, claims that early copper extraction was a uniquely complex craft requiring superior skill to be accomplished (Childe Citation1942, 77; Wertime Citation1964, Citation1973) are grossly overstated. Chalcolithic copper smelting mostly involved the one-step reduction of copper oxides/carbonates and fahlores under poorly reducing conditions (Bourgarit Citation2007). As anyone who has reproduced the process experimentally can state, it is not a technically difficult undertaking. The real problem lies in its poor yield and the amount of labour required to process copper from mine to object (Doonan Citation1994; Ottaway Citation2001). As for skill, metalworking doubtless necessitates mastery of certain technical abilities, but these varied through the chaîne opératoire from relatively simple (e.g. ore dressing) to complex (e.g. casting intricate objects). Skilled practice, moreover, is hardly unique to metalworking. Suffice it to consider the remarkable abilities and experience required to make a symmetrically flaked flint dagger (Apel Citation2008; Frieman Citation2012, with references). Of course, outstanding skill can be observed in early metalworking, but so can mediocrity and downright failure (Kuijpers Citation2018a, Citation2018b). There is nothing here but our metal-centric bias to suggest that copper working would demand a fundamental step-change in labour, knowledge, or skill investment compared to other prehistoric technologies.

Finally, the role of trade as a source of elite power must be debated. In Italy, multiple overlapping markers such as the exchange of Lipari obsidian and Alpine greenstone suggest that long-distance communication peaked in the late Neolithic, c.4500–3800 BC. Networks broke down abruptly, and all at the same time, in the final Neolithic, c.3800–3650 BC. In a few generations, their reach receded from over 1000 km to less than 200 km (Dolfini Citation2020). Copper, red jasper, steatite, and certain ophiolitic and metamorphic rocks replaced obsidian and greenstone as objects of desire for Copper Age communities. The new materials, however, travelled on average much less than their Neolithic counterparts. The maceheads from Rinaldone, for instance, are made of ophiolitic rocks quarried in the central Apennines. While we do not know the quarry’s exact location, scientific analysis suggests that it is within a 200 km radius from the site (D’Amico Citation2004, 277). Copper itself did not stray too far from the Tuscan mines whence it was sourced, although exceptions do apply (Dolfini, Angelini, and Artioli Citation2020; see also Artioli et al. Citation2020; Perucchetti et al. Citation2015).

Under these circumstances, it is unclear how aspiring leaders could have leveraged the power of distance to justify unequal access to goods and resources. Jasper, steatite, ophiolites and most metal could travel through the network in a few days or weeks. Could control over them really attain political power? Even if metals were displaced by longer-lasting indirect procurement mechanisms, it is unclear what special status could ever arise from objects that may have been within the reach of most adults in most communities (Robb and Harris Citation2013, 71). Compared with the sprawling web of Neolithic obsidian and greenstone exchange, the Copper Age prestige goods economy, if it ever existed, has a decidedly local flavour. This is counterintuitive: if the power of distance naturalised emerging elites’ claim to power, why did it wane precisely when society leaped towards inequality?

Rethinking warrior graves

I argued above that the complex taphonomy of Rinaldone-style chamber graves has concealed the many burials that were originally laid articulated and furnished; that a longstanding preoccupation with politically savvy self-aggrandisers has created models of elite power grounded in anachronistic ideas of the person; and that early metalworking was not the superior technology that it is often alleged to be, nor were its products uniformly rare, valuable, and sought after by Copper Age communities. This brings us back to the questions underpinning this paper: who was buried at Rinaldone, Casetta Mistici, and other warrior-grave sites? Why were these burials not broken up and their weapons scattered, as happened to most? I maintain that any interpretations ought to be rooted in what the mourners themselves chose to display at funerals: gender, age, and other facets of identity (including identity-defining relations, places and events) that may be difficult for us to discern, but were arguably clear to them; these would doubtless include the circumstances of one’s life and death.

Gender has long been identified as the aspect of identity most clearly exhibited in individual burials, in Italy as much as elsewhere. Robb (Citation1994, Citation2007) and Robb and Harris (Citation2013, Citation2018) contend that new binary ideas of gender arose throughout Europe in the 4th and 3rd millennia BC. These were expressed through material symbols – weaponry for men and jewellery and clothing for women – that were deployed redundantly across multiple media including burial, rock art and statuary. Robb and Harris’ reading captures well the shift in social logic underpinning early warrior graves. I argue, however, that the Italian evidence permits us to highlight further facets of prehistoric social identity and how it was reconfigured in death.

A point that is often missed is that, in Rinaldone-style burials, gender and age are deeply entwined. This is apparent in the way grave furnishings vary depending on both gender and the age group to which the deceased belong (Dolfini Citation2006). The point was underscored by Sofaer Derevenski (Citation2000) in a seminal paper discussing how metalwork and other culturally salient objects were used to mediate the life course in the Copper Age of the Carpathian basin. Sofaer’s insightful analysis illustrates how age-gender constructs lie at the core of prehistoric ideas of identity; how these changed through the life course; and how they were redefined in the grave through material culture and burial behaviour. Building on her study, I shall apply the concepts of life course and age-gender relations to the interpretation of burial and society proposed below.

I propose that, in Copper Age Italy, people were graded based on the amount (or quality) of life force or ‘virtue’ that they were understood to have, as is the case in many non-Western societies (Flannery and Marcus Citation2012, passim; Goldman Citation1970; see also Fedele Citation2008). Birth and family circumstances (e.g. belonging to a certain lineage) might have determined a person’s ‘baseline’ life force, but people could also gain or lose force during their lives depending on personal qualities, skills, deeds, and their transitioning to new gender and age groups. Boys and girls were probably endowed with a similar ‘virtue’ at birth. They were not conceived of as either male or female until 11/12 year of age, when boys would go through a rite of passage that turned them into men and warriors (Dolfini Citation2006). The rite would define their gender and boost (or change the quality of) their life force. From then on, they could be buried with weapons.

Girls, too, would probably undergo a rite of passage at puberty, but this was not emphasised in death; if it was, e.g. through clothing, that is no longer visible to us. From then on, boys and girls were set on different pathways regarding not just their gender identities but the quality of their ‘virtue’, and how to acquire it. Men could increase it by raiding neighbouring villages, killing enemies, and rustling sheep and cattle. Undoubtedly, they could also boost it by less violent means, but these were not selected for funerary display. Women must have accessed an equally rich spectrum of strategies to increase their life force including knowledge, skill, and the transition to new life conditions, which, however, were not displayed in the grave.

Upon ageing, both men and women would move to a new stage in their life course, which once again changed the quality of their ‘virtue’ and the social strategies available for its acquisition. Men would no longer participate in raiding and other forms of sanctioned violence. They would divest themselves of weapons to take up new roles and identities, for instance as community elders.Footnote2 Glimpses of this belief can be caught in the burials of senior men from Fontenoce, east-central Italy. Here, adult men were often given bone-tipped spears (Silvestrini and Pignocchi Citation1997, Citation2000; Silvestrini, Cazzella, and Pignocchi Citation2005). Osteological stress markers on their right shoulders and arms suggest that they had hunted and fought with these weapons for most of their life. Spears, however, were not placed with elderly men bearing the exact same stress markers (Cencetti, Chilleri, and Pacciani Citation2005); this suggests that they had transitioned to a new life stage. Senior women might have gone through a similar change but, once again, their reconstituted identity was not displayed in the grave through durable material culture.

As is common in societies with ideologically clear-cut identities, Copper Age communities would likely leave the door open to inversions and projections of the prescribed age-gender categories. This is hinted at by rare biologically female burials that are culturally defined as male through weapons. While sexing errors may account for some of the evidence, the inversion seems undisputable for recently studied, well-preserved burials (Carboni and Anzidei Citation2020, 300; Miari, Bestretti, and Rasia Citation2017, 204). Occasional warrior graves of children may be interpreted similarly. Traditionally, these burials are seen as evidence of ascribed rank (Carboni and Anzidei Citation2020, 301; Cazzella and Guidi Citation2011, 31). I argue instead that they are instances of projected maleness/adulthood, perhaps dictated by special life or death circumstances. American Plains Indians offer a tight analogy for a society subsuming into itself normative ideas of male valour and multiple genders (Otterbein Citation1970; Robb and Harris Citation2018).

Much though it was a desirable attribute, life force was acknowledged to bear ambiguous qualities, especially if possessed in inordinate amounts or acquired in perilous or polluting circumstances. Cross-culturally, violence is a source of both renown and contamination, tainting those who exercise it as much as their victims. Shedding blood or dying a violent death may cause a person to become bewitched or befouled; as a result, their ‘virtue’ could acquire undesirable qualities. In many a traditional society, the warriors who killed several enemies, as well as the victims of raids and homicides, are afforded special funerals to appease their dangerous or vengeful spirits. The Shuar (formerly Jivaro) of the Amazon Rainforest, for example, believe that killed warriors produce an avenging soul that leaves the body through the mouth. To prevent this eventuality, they used to shrink the heads of their victims and sew their lips (Harner Citation1972, 142–143). In other societies, taboos surround the graves and possessions of those tainted by violence, preventing the living from approaching them. The ‘Are’Are of the Solomon Islands are a case in point; they devote long-lasting ceremonies to the most venerated ancestors but leave in the forest, untouched and away from the living, the bodies of those who die a bad death (de Coppet Citation1981; Fowler Citation2018, 89–90).

Violence, I argue, is the reason why Copper Age communities left certain burials articulated and furnished. These individuals were not tribal leaders or Big Men, but successful warriors whose blood-stained hands and unclean life force would stand in the way of an ordinary multi-step funeral. When they died, assemblages of objects reminiscent of their warring personas were gathered. These often comprised used, unused, and unusable objects including, at Rinaldone, weapon skeumorphs (D’Amico Citation2004; Lemorini Citation2004). Some may have been the deceased’s own weapons, too tainted by blood to be handled by anyone else. Others may have been offerings from fellow warriors or arms captured from the enemy. Other objects still may have been made for the funeral, perhaps to signify absent people or events worth remembering. The disparate nature of these sets indicate that they were not personal possessions, but a grave-side materialisation of events, places, and relations central to the deceased’s life course. Foremost among them were the battles they had fought, the companions who had stood beside them and the foes they had slain.

The victims of bloodshed were also given one-step funerals; they may be men, women, and children alike. The female burial from Casetta Mistici, grave 7, had a flint arrowhead stuck in the soil next to her humerus, as though it was once embedded in the flesh; her skull, moreover, had been smashed by a blunt-force weapon (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020, 409). Similarly, the male warrior burial from Marcellina-Vasoli had a flint arrowhead embedded in his tibia (Sciarretta Citation1969, 90). Victims of violence might be more common than we think in Rinaldone-style burials, for acidic volcanic bedrock (common in west-central Italy) has eroded human remains at most sites, and wounds that do not leave any marks on the skeleton tend to go unnoticed. Suffice it to mention the Alpine Iceman, killed by an arrowshot that did not touch the bone (Gostner and Egarter Vigl Citation2002).

Inflicted or suffered violence was not the sole reason behind a special funerary treatment. Other circumstances might have caused a person’s life force to increase inordinately or to acquire perilous qualities, e.g. ritual knowledge, social stigma, and the frequentation of strange and distant peoples. The male burial from Casetta Mistici, grave 8, may belong to the latter category. His Levantine axe hints at an eastern Mediterranean connection that is unusual in 4th millennium BC Italy. Interestingly, mtDNA analysis suggests that he had a maternal ancestor (perhaps a mother or grandmother) from Western Asia (De Angelis and Rickards Citation2020, 744). If so, he might have carried a special ‘virtue’ in the eyes of his community, demanding that his body and resting place be left undisturbed.

Regardless of the specific life or death circumstances behind one-step funerals, it is telling that warrior graves (and furnished child and female burials) were frequently grouped together at special sites (e.g. Rinaldone and Casetta Mistici) or set apart from ordinary burials at most cemeteries (e.g. Lunghezzina, grave 4; Anzidei et al. Citation2003). Lack of ritual activity and unusual practices may mark these graves. At Casetta Mistici, entrance shafts bear little evidence of the rich material repertoire found at most sites, suggesting that these graves were seldom revisited. Some graves, moreover, had been sealed with massive stone slabs (e.g. grave 7; ), as if to trap in a malignant or vengeful dead. On occasion, things went even further. In grave 10, some years after the body had been laid to rest, someone crept into the burial chamber to stick an axe in the soil that had gathered above the burial (Anzidei, Carboni, and Mieli Citation2020, 417). Evidently, certain dead had better die twice.

Conclusion

In this paper, I have questioned the long-held belief that the warrior burials of Copper Age central Italy should be interpreted as prehistoric political leaders or idealised ‘heroes’. I proposed instead that those being afforded this minority burial treatment had had their life force boosted to dangerously inordinate levels, or changed by violent deeds (or violent deaths) into a malicious ‘virtue’. I argued that the special circumstances of these individuals’ lives and deaths compelled the mourners to treat them unlike most deceased, whose transition to ancestorhood entailed long-lasting rituals of dismemberment, circulation, and reburial.

My proposal rests upon a broader argument claiming that equipped burials might have been more common than we see archaeologically, for most dead had their furnishings removed from the grave during multi-step funerals. This gives us the false impression that metals were rarer and more prestigious than they actually were. The argument is further supported by a reassessment of early metal technology, arguing that much more copper circulated in 4th and 3rd millennium Italy than we see today; that the complexity of Chalcolithic copper working is often overstated; and that copper trade may not be as central to prehistoric power dynamics as it is often alleged to be. These considerations severe the long-standing tie between metal technology and male rank underpinning traditional interpretations of warrior graves. The explanatory gains made in these pages need not stop at the Apennine watershed, or indeed at the Alps. The notion that warrior graves may not contain prehistoric elites could be tested, for example, on Corded Ware and Bell Beaker burials. How many of them display healed or perimortem traumata? And is it just a coincidence that the Amesbury Archer, buried with pomp near Stonehenge, was born in a faraway land (Fitzpatrick Citation2011)?

As a final point to make, the new reading presented above does not deny that structured forms of leadership would exist in Copper Age Italy. What has been questioned instead is the idea that political power was single-mindedly displayed in the grave through metals and other exotica. Indeed, metalwork may have played a role in prehistoric power struggles, and it probably did. But so did a binary gender ideology that might have banned women from certain political roles; an age-grading system that likely assigned different domains of action to different age groups; and perhaps a societal structure in which not all lineages were conceived of as equal. Tribal leaders doubtless existed in early Italy. When they died, they were placed in a grave with a rich set of goods. After some time, the mourners would open the grave and move both bones and goods to the village to revere them. Eventually, they would return selected relics to the grave – so blessed that several other bodies would be placed by them over time. These, I argue, are the graves we should focus on as we search for prehistoric leaders, for leaders are more likely to be found in anonymous bone stacks than in the flashy burials of once-mighty warriors.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to Chloe Duckworth and David Govantes-Edwards for their tireless editorial work. I also thank Richard Chacon, Cristiano Iaia, Catherine J. Frieman and the late Giovanni Carboni for sending relevant material and highlighting readings of interest. I am indebted to Alberto Cazzella, Chris Fowler, Eleanor Harrison, and the journal’s anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. All opinions and errors are mine.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea Dolfini

Andrea Dolfini is a Senior Lecturer in Later Prehistoric Archaeology at Newcastle University, UK. He researches the social dynamics of material culture in the 5th – 2nd millennia BC (Late Neolithic, Chalcolithic and Bronze Age), focusing on early metallurgy, metalwork wear analysis, experimental archaeology, prehistoric warfare and violence, and technological change through time. He also is a specialist in the later prehistory of Italy and the Central Mediterranean region. Current research projects include ‘What this awl means', a Marie Sklodowska-Curie Fellowship exploring the function of early European metal awls and the ‘Case Bastione Archaeological Project’ investigating a multi-period settlement site in central Sicily.

Notes

1. No radiocarbon dates are available for the site as the human remains were reburied at an undisclosed location shortly after the excavation. Dolfini (Citation2004) proposed dating the site to a long timespan in the late 4th and 3rd millennia BC based on the data available at the time. Several radiocarbon dates from comparable burial sites and a recent review of early Italian metalwork suggest that Rinaldone should instead be dated to c.3650–3350 BC (Iaia and Dolfini Citationin press).

2. I am indebted to Chris Fowler for suggesting this interpretation.

References

- Allentoft, M. E., M. Sikora, K. G. Sjögren, S. Rasmussen, M. Rasmussen, J. Stenderup, P. B. Damgaard, et al. 2015. “Population Genomics of Bronze Age Eurasia.” Nature 522(7555): 167–172. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14507.

- Anzidei, A.P., and G. Carboni, eds. 2020. Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 2 vols. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Anzidei, A.P., G. Carboni, and G. Mieli. 2020. “Casetta Mistici (Roma): necropoli.” In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 1 vols., edited by A.P. Anzidei and G. Carboni, 399–419. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Anzidei, A.P., G. Carboni, P. Catalano, A. Celant, C. Lemorini, and S. Musco. 2003. “La necropoli eneolitica di Lunghezzina (Roma).” In Atti della XXXV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, 379–391. Florence: IIPP.

- Apel, J. 2008. “Knowledge, Know-how and Raw Material: The Production of Late Neolithic Flint Daggers in Scandinavia.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory 15 (1): 91–111. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10816-007-9044-2.

- Artioli, G., C. Canovaro, P. Nimis, and I. Angelini. 2020. “LIA of Prehistoric Metals in the Central Mediterranean Area: A Review.” Archaeometry 62 (S1): 53–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/arcm.12542.

- Aurisicchio, C., and L. Medeghini. 2020. “Analisi dei manufatti metallici dell’età del Rame provenienti dal territorio di Roma e suggerimenti sulla loro provenienza.” In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 2 vols., edited by A.P. Anzidei and G. Carboni, 531–547. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Barker, G. 1981. Landscape and Society: Prehistoric Central Italy. London: Academic Press.

- Barrett, J.C. 1994. Fragments from Antiquity: An Archaeology of Social Life in Britain, 2900–1200 BC. London: Blackwell.

- Bourgarit, D. 2007. “Chalcolithic Copper Smelting.” In Metals and Mines: Studies in Archaeometallurgy, edited by S. La Niece, D. Hook, and P Craddock, 3–14. London: British Museum.

- Bradley, R., and R. Chapman. 1986. “The Nature and Development of Long-distance Relations in Later Neolithic Britain and Ireland.” In Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-political Change, edited by C. Renfrew and J. Cherry, 127–136. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bradley, R. 1984. The Social Foundations of Prehistoric Britain: Themes and Variations in the Archaeology of Power. London: Longman.

- Braithwaite, M. 1984. “Ritual and Prestige in the Prehistory of Wessex C. 2200–1400 BC: A New Dimension to the Archaeological Evidence.” In Ideology, Power and Prehistory, edited by D. Miller and C. Tilley, 93–110. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bray, P., A. Cuénod, C. Gosden, P. Hommel, R. Liu, and A.M. Pollard. 2015. “Form and Flow: The ‘Karmic Cycle’ of Copper.” Journal of Archaeological Science 56: 202–209. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jas.2014.12.013.

- Bray, P.J., and A.M. Pollard. 2012. “A New Interpretative Approach to the Chemistry of Copper-alloy Objects: Source, Recycling and Technology.” Antiquity 86 (333): 853–867. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003598X00047967.

- Brück, J., and D. Fontijn. 2013. “The Myth of the Chief: Prestige Goods, Power, and Personhood in the European Bronze Age.” In The Oxford Handbook of the European Bronze Age, edited by A. Harding and H. Fokkens, 197–215. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brück, J. 2004. “Material Metaphors: The Relational Construction of Identity in Early Bronze Age Burials in Ireland and Britain.” Journal of Social Archaeology 4 (3): 307–333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605304046417.

- Brück, J. 2006. “Death, Exchange and Reproduction in the British Bronze Age.” European Journal of Archaeology 9 (1): 73–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1461957107077707.

- Brück, J. 2019. Personifying Prehistory: Relational Ontologies in Bronze Age Britain and Ireland. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Carboni, G., A. Celant, V. Forte, D. Magri, S. Nunziante Cesaro, and A.P. Anzidei. 2020. “I residui anidri contenuti nei vasi delle necropoli della Romanina e di Torre della Chiesaccia-necropoli (Roma) e la più antica attestazione di una bevanda fermentata nell’Eneolitico italiano: l’idromele.” In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 2 vols., edited by A.P. Anzidei and G. Carboni, 711–721. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Carboni, G., and A.P. Anzidei. 2020. “La facies di Rinaldone nel territorio di Roma: aspetti funerari ed identità culturale della terza area nucleare (gruppo ‘Roma-Colli Albani’) (ca. 4070–1870 a.C.).” In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 2 vols., edited by A.P. Anzidei and G. Carboni, 253–347. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Carboni, G. 2020. “La metallurgia del rame, dell’argento e dell’antimonio delle facies di Rinaldone (gruppo “Roma-Colli Albani”), del Gaudo e delle fasi di abitato nel territorio di Roma.” In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 2 vols., edited by A.P. Anzidei and G. Carboni, 481–516. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Cazzella, A. 2003. “Rituali funerari eneolitici nell’Italia peninsulare: l’Italia centrale.” In Atti della XXXV Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, 275–282. Florence: IIPP.

- Cazzella, A., and A. Guidi. 2011. “Il concetto di Eneolitico in Italia.” In Atti della XLIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, 25–32. Florence: IIPP.

- Cazzella, A. 1992. “Sviluppi culturali eneolitici nella penisola italiana.” In Neolitico ed Eneolitico, edited by A. Cazzella and M Moscoloni, 349–643. Rome: Biblioteca di Storia Patria.

- Cazzella, A. 1998. “Modelli e variabilità negli usi funerari di alcuni contesti eneolitici italiani.” Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 49: 431–445.

- Cencetti, S., F. Chilleri, and E. Pacciani. 2005. “I reperti scheletrici umani della necropoli di Fontenoce di Recanati: indicatori fisiopatologici e di stress funzionale.” In Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, 469–479. Florence: IIPP.

- Chapman, J. 1999. “The Origins of Warfare in the Prehistory of Central and Eastern Europe.” In Ancient Warfare: Archaeological Perspectives, edited by J. Carman and A Harding, 101–142. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Chapman, J. 2000. Fragmentation in Archaeology: People, Places and Broken Objects in the Prehistory of the South-Eastern Europe. London: Routledge.

- Childe, V.G. 1942. What Happened in History. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books.

- Clarke, D.V., T.G. Cowie, and A. Foxon. 1985. Symbols of Power at the Time of Stonehenge. Edinburgh: National Museum of Antiquities of Scotland.

- Colini, G.A. 1903. “Tombe eneolitiche del Viterbese.” Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 29: 150–186.

- Crellin, R.J., and O.J. Harris. 2020. “Beyond Binaries. Interrogating Ancient DNA.” Archaeological Dialogues 27 (1): 37–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203820000082.

- Cristiani, E., and F. Alhaique. 2005. “Flint vs. Metal: The Manufacture of Bone Tools at the Eneolithic Site of Conelle Di Arcevia (Central Italy).” In From Hooves to Horns, from Mollusc to Mammoth (Proceedings of the 4th Meeting of the Worked Bone Research Group), edited by H. Luik, A.M. Choyke, C.E. Batey, and L. Lougas, 397–403. Tallinn: International Council for Archaeozoology.

- D’Amico, C. 2004. “Determinazioni petrografiche preliminari dei materiali in pietra levigata delle tombe 1-5 di Rinaldone.” Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 95: 273–277.

- De Angelis, F., and O. Rickards. 2020. “L’approccio bio-molecolare allo studio delle comunità eneolitiche del territorio di Roma.” In Roma Prima del Mito. Abitati e necropoli dal Neolitico alla prima età dei metalli nel territorio di Roma (VI-III millennio a.C.). 2 vols., edited by A.P. Anzidei and G. Carboni, 737–744. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- de Coppet, D. 1981. “The Life-giving Death.” In Mortality and Immortality: The Anthropology and Archaeology of Death, edited by S. Humphrey and H. King, 175–204. London: Academic Press.

- Dolfini, A., I. Angelini, and G. Artioli. 2020. “Copper to Tuscany–Coals to Newcastle? The Dynamics of Metalwork Exchange in Early Italy.” PlosOne 15 (1): e0227259. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227259.

- Dolfini, A. 2004. “La necropoli di Rinaldone (Montefiascone, Viterbo): rituale funerario e dinamiche sociali di una comunità eneolitica in Italia centrale.” Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 95: 127–263.

- Dolfini, A. 2006. “Embodied Inequalities: Burial and Social Differentiation in Copper Age Central Italy.” Archaeological Review from Cambridge 21 (2): 58–77.

- Dolfini, A. 2015. “Neolithic and Copper Age Mortuary Practices in the Italian Peninsula: Change of Meaning or Change of Medium?” In Death and Changing Rituals: Function and Meaning in Ancient Funerary Practices, edited by J. R. Brandt, H. Ingvaldsen, and M. Prusac, 17–44. Oxbow: Oxford.

- Dolfini, A. 2020. “From the Neolithic to the Bronze Age in Central Italy: Settlement, Burial, and Social Change at the Dawn of Metal Production.” Journal of Archaeological Research 28: 503–556.

- Doonan, R.C. 1994. “Sweat, Fire and Brimstone: Pre-treatment of Copper Ore and the Effects on Smelting Techniques.” Historical Metallurgy 28 (2): 84–97.

- Fedele, F. 2008. “Statue-menhirs, Human Remains and Mana at the Ossimo ‘Anvòia’ Ceremonial Site, Val Camonica.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 21 (1): 57–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/jmea.v21i1.57.

- Fitzpatrick, A.P. 2011. The Amesbury Archer and the Boscombe Bowmen: Bell Beaker Burials at Boscombe Down, Amesbury, Wiltshire. Salisbury: Wessex Archaeology.

- Flannery, K., and J. Marcus. 2012. The Creation of Inequality: How Our Prehistoric Ancestors Set the Stage for Monarchy, Slavery, and Empire. Harvard: Harvard University Press.

- Fowler, C. 2004. The Archaeology of Personhood: An Anthropological Approach. London: Routledge.

- Fowler, C. 2005. “Identity Politics: Personhood, Kinship, Gender and Power in Neolithic and Early Bronze Age Britain.” In The Archaeology of Plural and Changing Identities: Beyond Identification, edited by E. Casella and C Fowler, 109–134. New York: Kluwer Academic Press.

- Fowler, C. 2013. The Emergent Past: A Relational Realist Archaeology of Early Bronze Age Mortuary Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Fowler, C. 2017. “Relational Typologies, Assemblage Theory and Early Bronze Age Burials.” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 27 (1): 95–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774316000615.

- Fowler, C. 2018. “Personhood, the Life Course and Mortuary Practices in Mesolithic, Neolithic and Chalcolithic Europe.” In Antropologia e archeologia a confronto: Archeologia e antropologia della morte. 2 vols., edited by V Nizzo, 83–118. Rome: Fondazione Diá Cultura.

- Frieman, C.J. 2012. Innovation and Imitation: Stone Skeuomorphs of Metal from 4th-2nd Millennia BC Northwest Europe. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Furholt, M. 2019. “Re-integrating Archaeology: A Contribution to aDNA Studies and the Migration Discourse on the 3rd Millennium BC in Europe.” Proceedings of the Prehistoric Society 85: 115–129.

- Furholt, M. 2018. “Massive Migrations? The Impact of Recent aDNA Studies on Our View of Third Millennium Europe.” European Journal of Archaeology 21 (2): 159–191. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2017.43.

- Gernone, P. 1998. “Pianaccia di Suvero: atelier per la lavorazione della steatite.” In Dal Diaspro al Bronzo. L’età del Rame e del Bronzo in Liguria: 26 secoli di storia fra 3600 e 1000 anni avanti Cristo, edited by A. Del Lucchese and R. Maggi, 161–163. La Spezia: Luna Editore.

- Gimbutas, M. 1977. “The First Wave of Eurasian Pastoralists into Copper Age Europe.” Journal of Indo-European Studies 5 (4): 277–338.

- Godelier, M. 1986. The Making of Great Men: Male Domination and Power among the New Guinea Baruya. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Godelier, M., and M. Strathern, eds. 1991. Big Men and Great Men: Personifications of Power in Melanesia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Goldman, I. 1970. Ancient Polynesian Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Gostner, P., and E. Egarter Vigl. 2002. “INSIGHT: Report of Radiological-forensic Findings on the Iceman.” Journal of Archaeological Science 29 (3): 323–326. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jasc.2002.0824.

- Haak, W., I. Lazaridis, N. Patterson, N. Rohland, S. Mallick, B. Llamas, G. Brandt, et al. 2015. “Massive Migration from the Steppe Was a Source for Indo-European Languages in Europe.” Nature 522(7555): 207–211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14317.

- Hansen, S. 2013. “The Birth of the Hero: The Emergence of a Social Type in the 4th Millennium BC.” In Unconformist Archaeology: Papers in Honour of Paolo Biagi, edited by E. Starnini, 101–112. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Harner, M. 1972. The Jivaro: People of the Sacred Waterfalls. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Hernando, A. 2017. The Fantasy of Individuality: On the Sociohistorical Construction of the Modern Subject. New York: Springer.

- Horn, C., and K. Kristiansen. 2018. “Introducing Bronze Age Warfare.” In Warfare in Bronze Age Society, edited by C. Horn and K Kristiansen, 1–15. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Iaia, C., and A. Dolfini. In press. “A New Seriation and Chronology for Early Italian Metalwork, 4500–2100 BC.” Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche.

- Jeunesse, C. 2014. “Emergence of the Ideology of the Warrior in the Western Mediterranean during the Second Half of the Fourth Millennium BC.” Eurasia Antiqua 20: 171–184.

- Jones, A.M. 2002. “A Biography of Colour: Colour, Material Histories and Personhood in the Early Bronze Age of Britain and Ireland.” In Colouring the Past, edited by A. Jones and G MacGregor, 159–174. Oxford: Berg.

- Kristiansen, K., M.E. Allentoft, K.M. Frei, R. Iversen, N.N. Johannsen, G. Kroonen, Ł. Pospieszny, et al. 2017. “Re-theorising Mobility and the Formation of Culture and Language among the Corded Ware Culture in Europe.” Antiquity 91 (356): 334–347. doi:https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2017.17.

- Kristiansen, K. 1999. “The Emergence of Warrior Aristocracies in Later European Prehistory.” In Ancient Warfare: Archaeological Perspectives, edited by J. Carman and A Harding, 175–189. Stroud: Sutton Publishing.

- Kuijpers, M.H. 2018a. An Archaeology of Skill: Metalworking Skill and Material Specialization in Early Bronze Age Central Europe. London: Routledge.

- Kuijpers, M.H. 2018b. “The Bronze Age, a World of Specialists? Metalworking from the Perspective of Skill and Material Specialization.” European Journal of Archaeology 21 (4): 550–571. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/eaa.2017.59.

- Laviosa Zambotti, P. 1943. Le più antiche culture agricole europee. Milan: Principato.

- Lemorini, C. 2004. “Studio funzionale delle cuspidi di freccia delle tombe 1-5 di Rinaldone (Viterbo).” Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 95: 265–272.

- Miari, M., F. Bestretti, and P.A. Rasia. 2017. “La necropoli eneolitica di Celletta dei Passeri (Forlì): analisi delle sepolture e dei corredi funerari.” Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 67: 145–208.

- Olalde, I., S. Brace, M. E. Allentoft, I. Armit, K. Kristiansen, T. Booth, N. Rohland, et al. 2018. “The Beaker Phenomenon and the Genomic Transformation of Northwest Europe.” Nature 555(7695): 190–196. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nature25738.

- Olalde, I., S. Mallick, N. Patterson, N. Rohland, V. Villalba-Mouco, M. Silva, K. Dulias, et al. 2019. “The Genomic History of the Iberian Peninsula over the past 8000 Years.” Science 363(6432): 1230–1234. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aav4040.

- Ottaway, B.S. 2001. “Innovation, Production and Specialization in Early Prehistoric Copper Metallurgy.” European Journal of Archaeology 4 (1): 87–112. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/eja.2001.4.1.87.

- Otterbein, K.F. 1970. The Evolution of War: A Cross-cultural Study. New Haven: HRAF Press.

- Pearce, M. 2009. “How Much Metal Was There in Circulation in Copper Age Italy?” In Metals and Societies: Studies in Honour of Barbara S. Ottaway, edited by T.L. Kienlin and B.W. Roberts, 277–284. Bonn: Rudolf Habelt.

- Peet, T.E. 1909. The Stone and Bronze Ages in Italy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pernier, L. 1905. “Tombe eneolitiche nel Viterbese.” Bullettino di Paletnologia Italiana 31: 145–153.

- Peroni, R. 1971. L’Età del Bronzo nella Penisola Italiana I: L’Antica Età del Bronzo. Florence: Accademia Toscana di Scienze e Lettere ‘La Colombaria’.

- Peroni, R. 1989. Protostoria dell’Italia continentale: La penisola italiana nelle età del Bronzo e del Ferro. Rome: Biblioteca di storia patria.

- Perucchetti, L., P. Bray, A. Dolfini, and A.M. Pollard. 2015. “Physical Barriers, Cultural Connections: Prehistoric Metallurgy across the Alpine Region.” European Journal of Archaeology 18 (4): 599–632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/1461957115Y.0000000001.

- Puglisi, S.M. 1959. La civiltà appenninica: Origine delle comunità pastorali in Italia. Firenze: Sansoni.

- Renfrew, C. 1973. “Monuments, Mobilization and Social Organization in Neolithic Wessex.” In The Explanation of Culture Change, edited by C. Renfrew, 89–112. London: Duckworth.

- Renfrew, C. 1974. “Beyond a Subsistence Economy: The Evolution of Social Organisation in Prehistoric Europe.” In Reconstructing Complex Societies: An Archaeological Colloquium, edited by C. Moore, 69–95. Baltimore, MD: Supplement to the Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 20.

- Robb, J.E. 1994. “Gender Contradictions, Moral Coalitions, and Inequality in Prehistoric Italy.” Journal of European Archaeology 2 (1): 20–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/096576694800719256.

- Robb, J.E. 1999. “Great Persons and Big Men in the Italian Neolithic.” In Social Dynamics of the Prehistoric Central Mediterranean, edited by R. H. Tykot, J. Morter, and J.E. Robb, 111–121. London: Accordia Research Institute.

- Robb, J.E. 2007. The Early Mediterranean Village: Agency, Material Culture, and Social Change in Neolithic Italy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robb, J.E., and O.J. Harris, eds. 2013. The Body in History: Europe from the Palaeolithic to the Future. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Robb, J.E., and O.J. Harris. 2018. “Becoming Gendered in European Prehistory: Was Neolithic Gender Fundamentally Different?” American Antiquity 83 (1): 128–147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2017.54.

- Sciarretta, F. 1969. “Contributi alla conoscenza della preistoria e protostoria di Tivoli e del suo territorio.” Atti della Società Tiburtina di Storia e d’Arte 42: 7–113.

- Shennan, S. 1982. “Ideology, Change and the European Early Bronze Age.” In Symbolic and Structural Archaeology, edited by I. Hodder, 155–161. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shennan, S. 1986. “Interaction and Change in the Third Millennium BC Western and Central Europe.” In Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-Political Change, edited by C. Renfrew and J. Cherry, 137–148. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Silvestrini, M., A. Cazzella, and G. Pignocchi. 2005. “L’organizzazione interna della necropoli di Fontenoce – area Guzzini.” In Atti della XXXVIII Riunione Scientifica dell’Istituto Italiano di Preistoria e Protostoria, 457–467. Florence: IIPP.

- Silvestrini, M., and G. Pignocchi. 1997. “La necropoli eneolitica di Fontenoce di Recanati: lo scavo 1992.” Rivista di Scienze Preistoriche 48: 309–366.

- Silvestrini, M., and G. Pignocchi. 2000. “Recenti dati dalla necropoli eneolitica di Fontenoce di Recanati.” In Recenti acquisizioni, problemi e prospettive della ricerca sull’Eneolitico dell’Italia centrale, edited by M. Silvestrini, 39–50. Ancona: Regione Marche.

- Skeates, R. 1995. “Transformations in Mortuary Practice and Meaning in the Neolithic and Copper Age of Lowland East-Central Italy.” In Ritual, Rites and Religion in Prehistory, edited by W. H. Waldren, J. A. Ensenyat, and R. C Kennard, 211–237. Oxford: Archaeopress.

- Sofaer Derevenski, J. 2000. “Rings of Life: The Role of Early Metalwork in Mediating the Gendered Life Course.” World Archaeology 31 (3): 389–406. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240009696928.

- Thomas, J. 1991. “Reading the Body: Beaker Funerary Practice in Britain.” In Sacred and Profane: Archaeology, Ritual and Religion, edited by P. Garwood, D. Jennings, R. Skeates, and J Toms, 33–42. Oxford: Oxford University Committee for Archaeology.

- Thomas, J. 1999. Understanding the Neolithic. London: Routledge.

- Thomas, J. 2002. “Archaeology’s Humanism and the Materiality of the Body.” In Thinking through the Body: Archaeologies of Corporeality, edited by Y. Hamilakis, M. Pluciennik, and S Tarlow, 29–46. New York: Kluwer Academic Press.

- Thomas, J. 2004. Archaeology and Modernity. London: Routledge.

- Thorpe, N., and C. Richards. 1984. “The Decline of Ritual Authority and the Introduction of Beakers into Britain.” In Neolithic Studies: A Review of Some Recent Work, edited by R. Bradley and J Gardiner, 67–84. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Treherne, P. 1995. “The Warrior’s Beauty: The Masculine Body and Self-identity in Bronze-Age Europe.” Journal of European Archaeology 3 (1): 105–144. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/096576695800688269.

- Vander Linden, M. 2006a. Le phénomène campaniforme dans l’Europe du 3ème millénaire avant notre ère. Synthèse et nouvelles perspectives. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports.

- Vander Linden, M. 2006b. “For Whom the Bell Tolls: Social Hierarchy Vs Social Integration in the Bell Beaker Culture of Southern France (Third Millennium BC).” Cambridge Archaeological Journal 16 (3): 317–332. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0959774306000199.

- Vander Linden, M. 2007. “For Equalities are Plural: Re-assessing the Social in Europe during the Third Millennium BC.” World Archaeology 39 (2): 177–193. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438240701249678.

- Vandkilde, H. 2006. “Warriors and Warrior Institutions in Copper Age Europe.” In Warfare and Society: Archaeological and Social Anthropological Perspectives, edited by T. Otto, H Thrane, and H. Vandkilde, 393–431. Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

- Vandkilde, H. 2018. “Body Aesthetics, Fraternity and Warfare in the Long European Bronze Age: Postscriptum.” In Warfare in Bronze Age Society, edited by C. Horn and K Kristiansen, 229–243. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Wertime, T.W. 1964. “Man’s First Encounter with Metallurgy.” Science 146 (3649): 1257–1267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.146.3649.1257.

- Wertime, T.W. 1973. “The Beginnings of Metallurgy: A New Look.” Science 182 (4115): 875–887. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.182.4115.875.