Introduction

Interest in marginal lives has increased steadily in archaeology since the 1980s. Post-processual archaeology brought attention to the diversity of social experiences that were often invisibilised or at least disregarded in processual accounts and, more specifically, to subaltern communities. A concern with the marginalised became even more important in two paradigms related to post-processualism: critical theory (Leone, Potter, and Shackel Citation1987) and postcolonialism (Given Citation2004; Marín-Aguilera Citation2021; Montón-Subías and Dixon Citation2021, this issue). Marginal lives have been the focus of particular concern in historical archaeology (Orser Citation1996, 159–182; Hall Citation1999), probably because they have proliferated since 1500 and become archaeologically conspicuous – slaves, prostitutes, indentured labourers, the colonised, the poor (Singleton Citation1995: Yamin Citation2005; Spencer-Wood and Matthews Citation2011, Hansson et al. Citation2020). The archaeology of the contemporary past is equally committed to the subaltern, and some of the most important research in this subfield deals with hypermarginalised communities, including homeless people (Zimmerman, Singleton, and Welch Citation2010; Kiddey Citation2017), ethnic minorities (Nordin, Fernstål, and Hyltén-Cavallius Citation2021) and refugees (Hamilakis Citation2017, Citation2021), among others. Indeed, it could be argued that the history of modernity is as much a process of emancipation as one of increased production of marginalisation (Bauman Citation2004). It is thus not a coincidence that in the present issue the last five centuries account for the largest number of contributions.

Yet modernity is surely not the only producer of subaltern lives and spaces. This can be traced at least to the emergence of stratified societies, which in the case of Egypt and the Middle East go back to the fourth millennium BC – see Greenberg (Citation2021); Lemos and Budka (Citation2021), in this issue, for examples. The study of marginal identities as such in prehistoric and early historic contexts, however, has elicited less interest than in modern contexts. Exceptions are the archaeology of colonization in the Mediterranean, where there is a plethora of studies on silenced and peripheral groups (Given Citation2004; Delgado Hervás Citation2010; Van Dommelen Citation2019; Marín-Aguilera Citation2021), and of the Roman provinces, where scholars have paid attention to subaltern identities and cultural expressions (Webster Citation2001; Hingley Citation2005). It is expected that the articles included in this issue will attract greater interest in similar situations in other periods and regions.

At this point, it is important to reflect on who or what is considered marginal in a given society. Marginal peoples cannot be immediately equated with the lower classes, as not all lower classes are conceptualized as marginal by hegemonic social discourse (peasants or workers, for instance). As the adjective implies, marginal peoples are those who exist or are forced to exist on the edges of a certain social system from which they are excluded (or self-excluded) in different ways. They can be regarded as not fully pertaining to the social body (as happens with Roma, undocumented migrants or homeless people today) or even to humanity (like slaves in ancient Greece). Marginality as a social phenomenon is better seen as a spectrum. On one side, we have groups that are actively marginalised by dominant society – their freedom curtailed, their identities stigmatised, their labour exploited or their economic and social opportunities denied. Slaves and Indian Dalit (‘untouchables’) are typical examples. On the other side, we have groups that voluntarily choose the margins (spatial as much as social), seeking political freedom, economic opportunities or spiritual plenitude. Here we have rebels, pirates and hermits. There are still others who would not consider themselves as marginal, even if they are perceived as such by mainstream society: in this situation we have those called ‘peripatetic peoples’ (Berland and Rao Citation2004), nomads and foragers living in state or agricultural peripheries.

The study of marginal groups is necessarily linked to the study of the marginal places they inhabit or are forced to inhabit, such as slave quarters, maroon settlements, slums, brothels, ruins and vacant lots. There has been, however, relatively little reflection on marginal places per se and how they produce and resist social marginality. More emphasis has been put on consumption and other everyday practices (Mullins Citation1999; Silliman Citation2010). This introductory article intends to redress the imbalance by exploring the nature of marginal places along their various dimensions: spatial, material, economic and political, all of which, as we will see, is permeated by the symbolic.

Marginal space: peripheries, edgelands, terrain vague

Much of the space occupied by marginal peoples is what could be described as ‘leftover places’ (Bauman Citation2004, 98–104): the debris resulting from the spatial operations of hegemonic orders – everything that is considered dirty, hostile or undesirable. This is also the case when such space is crucial from an economic or political view, such as pastoral lands or zones of extraction under capitalism. To understand marginal places, we have to take into account two dimensions: location and production. Regarding location, when we think of margins, we think immediately of sites that are in the periphery or the edge of something, and this is surely the definition of ‘margin’. Yet not all margins are physically peripheral. The location of marginality is, in fact, quite complex and comprises spaces of exteriority and interiority as well as those that are ontologically indeterminate.

Marginal spaces of exteriority include all those that exist outside dominant space, both close at hand and far away. They can be places of exile and confinement, such as prisons, ghettos and refugee camps located in outskirts or peripheries, out of sight, but not out of reach. Marginal spaces of exteriority can also be places of shelter, out of sight and out of reach, often located in borderlands – like camps of brigands and guerrillas, maroon sites or refuges of indigenous groups. Internal margins, instead, coexist with dominant space, often at its heart: indigenous labourers and slaves, for instance, often shared space with their masters in ranches and plantations in North America (Silliman Citation2010). Internal margins include the camps and dwellings of homeless people (Kiddey Citation2017; Zimmerman, Singleton, and Welch Citation2010), clandestine places for illicit activities – such as prostitution or drug dealing and consumption – and even detention and classification centres. The latter can be official, such as the Australian immigration depots studied by Connor (Citation2021) in this issue; the control stations set up by the American government for Japanese American citizens explored here by Lau-Ozawa (Citation2021), and the immigrants’ internment centres in Europe (Tejerizo García et al. Citation2017). They can also be clandestine, such as the detention centres of the Argentinian dictatorship (Zarankin and Niro Citation2009). Both configure dark geographies of alienation that are juxtaposed to the hegemonic city.

Regarding ontologically ambiguous spaces, we can include here what have been described as interstitial places (Harrison and Schofield Citation2010, 228–247) and edgelands, among others (Farley and Roberts Citation2012). Edgelands, as defined by Farley and Roberts (Citation2012), are particularly expressive of this ambiguity: they are unremarkable and invisible, neither urban not rural, often nondescript spaces of transit, but they do not perfectly overlap with non-places (Augé Citation1995). Within this category, in England, the authors include power stations, canals, woodlands, landfills, paths, bridges, hotels and piers, which have in common their being marginal in mainstream spatial imagination (as opposed, to, say the main square of a town, a museum or a school). Not all are used by the marginalised, but many, indeed, are. An even stronger sense of indeterminacy is captured by the concept of ‘terrain vague’ coined by architect Ignasi de Solà-morales (Citation2013) and that serves to describe many empty spaces within cities. The term ‘vague’ refers to such ambiguity, but also to empty (vacuum), free, unoccupied. It is precisely this indeterminacy that holds immense political and aesthetic possibilities. The ruins and empty lots occupied by Kura-Araxes people in semi-abandoned urban environment, as described by Greenberg (Citation2021) in this issue, are good examples of this ‘terrain vague’ and its potential to foster counter-hegemonic social orders in prehistory. Many dominant places, however, also have a measure of ontological ambiguity: spaces that are hegemonic or associated with power during the day (such as a financial district) may become marginal at night, as they are occupied by homeless people or become the stage for illegal or illicit activities. The dimension of temporality, thus, has to be added to our understanding of marginal space. Likewise, many marginal places exist at the heart of hegemonic environments – these are what are best defined as interstitial places – and include alleyways or even secluded areas in parks and campuses (González-Ruibal Citation2019, 158–160).

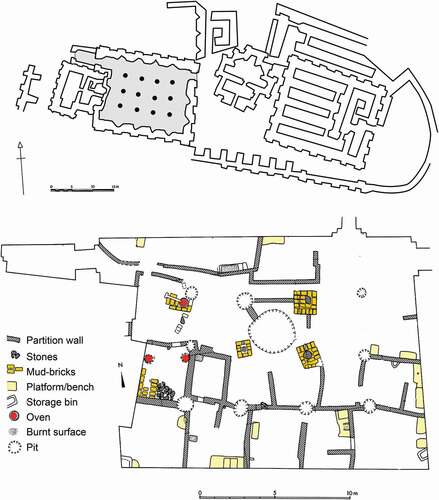

The production of marginal space refers to two different but related things: on the one hand, to the creation of places – both physical and symbolic – to which subaltern groups are confined, which could be called heterotopias of deviation and marginalisation (Foucault Citation1986), from slums to prisons. However, it also to all the operations undertaken by marginal communities to reshape and recreate place in those same environments where they have been confined. This often implies creating social space out of ruins or inhospitable, even uninhabitable places. Such operations include the construction of unregulated, improvised neighbourhoods and shanty towns. They are definitely not something contemporary, although they have grown enormously from the mid-twentieth century onwards fuelled by rural exodus and the growth of cities. Yet improvised neighbourhoods are known in ancient cities as well, and they can be documented archaeologically through their distinctive layouts. Michael E. Smith (Citation2010: 235–236, 242–243) suggests that such neighbourhoods can be identified in Mesoamerican and Andean towns of the first and early second millennium AD, such as Cuexcomate, Teotihuacan or Chan Chan, as agglomerations of informally laid-out houses and compounds, with divergent orientations, poor materials and apparent lack of order. They are suggestive of bottom-up processes of settlement and often contrast with adjacent or contemporary urban spaces with highly planned, orthogonal layouts. A good case in point, in this case in Sub-Saharan Africa, is the low-class neighbourhood of the third-sixth century AD town of Matara (Eritrea), whose architecture and apparently chaotic organization of space contrasts starkly with that of elite quarters (Anfray Citation2012) (). In places where planned layouts are not valued (as in Medieval Europe), the production of marginal spaces resorts to other mechanisms, including distinct materialities, architectures and locations.

Figure 1. Map of the town of Matara (Eritrea) showing elite compounds and a low-class neighbourhood (shaded). The latter shows a different orientation, no orthogonal layouts and lack of modules. After Anfray (Citation2012) with modifications.

In many cases, the production of marginal spaces does not take the form of construction, but of appropriation. By appropriation I understand all those practices that allow marginal communities to turn a hegemonic or alien space into a familiar environment: a tactic of place-making (Soto Citation2016). Appropriation is at times a form of resistance against the displacement and confinement to hostile places or non-places. It can take many shapes. At its simplest, it is mere presence: a form of occupation that does not modify in any material way a certain environment. Thus, non-places, such as bridges, are often used by undocumented migrants or homeless people without the addition or subtraction of matter. Their presence, however, can be detected through the material traces they leave behind, from mattresses to discarded food items (Zimmerman, Singleton, and Welch Citation2010; Kiddey Citation2017; Lekakis Citation2019; Santacreu Citation2021). Appropriation of space by marginalised people today usually takes the form of inscription: graffiti (Soto Citation2016; Bryning et al. Citation2021. this issue). Their importance should not be underestimated: for people that have no voice, who are invisible to all effects, whose lives will go unrecorded even if they have a violent and sudden end, writing or painting on a wall is a way of asserting their existence as human beings. This is particularly the case in margins of confinement, such as prisons or concentration camps – see Schofield et al. (2021), this issue, and below – where they are at the same time testimony of a life in danger and a form of (spiritual) liberation: they subvert the walls by transforming them into an ‘apparatus of exit’ (Stoner 2018 [Citation2011], 124).

Squatting is the most common and archaeologically visible form of appropriating space by marginal groups. Despite plentiful archaeological evidence of squatting, this phenomenon has been seldom examined as something worth of attention per se – but see Dawdy (Citation2010); Bernbeck (Citation2019); Bradfield and Lotter (Citation2021); Greenberg (Citation2021), this issue. Thus, although references to squatting in archaeological reports are ubiquitous, they are mostly described as a nuisance: a footnote on post-abandonment or a post-depositional problem – see a perceptive critique of its political implications in Worsham (Citation2021). Against this prevalent view, Bernbeck (Citation2019) suggests that we look at squatter occupations as both a third space, following Henri Lefebvre, a lived space that defies perceived and planned views of place, and as proof of a pre-existing social conflict, which was repressed. In this perspective, occupation by the marginalised of former sites of power, which subverts overregulated layouts and imposing monumentalities, would represent ‘a solution to previous antagonistic constellations’ (Bernbeck Citation2019: 13) (). Squatters deploy their own spatialities. A good example is provided by Soba, the capital of the medieval kingdom of Alodia in Sudan. By the thirteenth century, the buildings associated with power, such as churches and elite buildings, were abandoned or had been destroyed, and ephemeral huts and non-Christian burials were built on top (Welsby Citation1998, 44–49). If we consider that they were most probably made by invading Nilotes (who had been traditionally enslaved by people from northern Sudan), we can better appreciate the subversive potential of squatting.

Figure 2. Above: the elite complex of Nush-i Jan, Iran (750–650 BC). Below: detail of the post-650 BC squatter occupation of one of the rooms – the columned hall. The space was partitioned to accommodate to the needs of the villagers that settled in. Redrawn after Bernbeck (Citation2019).

Materiality: subaltern assemblages

Shannon Lee Dawdy (Citation2010: 773) distinguishes two opposing urban aesthetics: one of cleanliness and order and one that strives to escape its rigidities: the city of ruins, abandoned places, neglected neighbourhoods and squatter camps. The second aesthetic, however, is often more often than not the result of want rather than conscious choice. In fact, marginal places tend to be those to which subalterns have been expelled and in which they have been confined. They are derelict and polluted and associated with waste and garbage – see Papoli (Citation2021), this issue – an association that is extended to their inhabitants, who are depicted as squalid and miserable: morally, socially and materially (Bauman Citation2004).

Yet by looking only at the negative side of marginal places we may overlook their disruptive potential and their creativity. Subaltern creativity has often been associated with music and dance (Gilroy Citation1993; Sneed Citation2008), but there is a strong material element that should not be underestimated. This materiality of the marginal can be approached through the concept of subaltern assemblage (González-Ruibal Citation2022), with which I refer to the artefacts, infrastructures, technologies, substances and materials, modes of maintenance, forms of dwelling, institutions and relations that compound marginalised livelihoods.

From a strictly material point of view, there are some elements that are commonly shared transculturally and transhistorically in these subaltern assemblages: this includes the use of perishable, recycled and humble materials, which tend to leave little trace in the archaeological record, as opposed to the more solid constructions of hegemonic orders – see the case of the Roma camp studied by Nordin, Fernstål, and Hyltén-Cavallius (Citation2021), in this issue. In maroon settlements, researchers have pointed out the enormous difficulties posed by the precarious structures erected by fugitive slaves, which are barely visible, if at all (Goucher and Agorsah Citation2011; Weik, Citation2012), the more so in tropical environments. In the case of Roman villas reoccupied between the fifth and seventh centuries, negative features are commonplace, such as pits and hearths cut into pavements and mosaics, along with wooden and wattle-and-daub structures. While a revision of these ‘residual’ occupations has reinterpreted them as proof of cultural change among the elites, who cast aside the trappings of classical culture (Lewit Citation2003), some were the work of actual squatters (Dodd Citation2019). The nature of their materiality has led to disparaging remarks by researchers, who have described it as ‘messy’, ‘rude’ or ‘wretched’ and have often cleared it without proper recording (Dodd Citation2019, 31; see also Worsham Citation2021). The dismissal of squatter occupations by archaeologists (entailed in the very notion of ‘residual’) re-marginalises subaltern populations of the past (or marginalises them, when they were not considered so in the past) – and of the present. Seeing these occupations as inconsequential is equal to denying their historicity: yet they do contribute to history. In fact, periods of neglect and abandonment are at times the richest archaeologically (Dawdy Citation2010, 777). In the trenches of the Spanish Civil War that I had the opportunity to study at the University City of Madrid, homeless occupations account for over 80 years of history and over 1.5 meters of stratigraphic deposits in places and attest to a complex history that has been utterly forgotten (González-Ruibal Citation2019, 158–160).

Precarious materialities should not be seen exclusively as the outcome of economic scarcity. At times, there might be an egalitarian ethos behind, a refusal of anything that can endure, solidify distinctions or petrify claims to property or status (Strother Citation2004). In this context, infrastructures become counterinfrastructures (see Stewart, Gokee, and De León Citation2021), whose aim is to dodge the traps of power and to facilitate camouflage, movement and escape (Given Citation2004, 151–160). This has often been the case with nomadic pastoralists and Roma people.

Ephemerality, precarious materialities and counterinfrastructures can all be encompassed under the concept of minor architecture. The term, coined by Jill Stoner (Citation2018[2011]) refers to a spatial counterpractice based on improvisation, transience and recycling that subverts major architecture – that created by architects and sponsored by the state, religious institutions or elite individuals and corporations. Against the architectures of power, which in many cultures tend to emphasise individuality, exclusivity and the representational, minor architectures emphasise inclusivity, practical purposes and the collective. They often resort to the appropriation of preexisting buildings, which they reinterpret in a more egalitarian light. Stoner offers the example of the Corviale complex in Rome, a social housing development, and the Tower of David, an incomplete business centre in Caracas, both examples of dominant architectures that have been subverted in different ways by subaltern communities. The examples are, in fact, not very different from others known in prehistoric and early historic times, such as the third-millennium BC Kura-Araxes squatters described by Greenberg (Citation2021) in this issue; the elite complexes of the Medes reappropriated by peasants in the seventh century BC (Bernbeck Citation2019) or the Roman villas mentioned above. Indeed, the huts that arise amid monumental ruins constitute some of the best imaginable examples of minor architectures. They can also be built ex novo, such as the lanchos of Guam studied by Montón-Subías and Dixon (Citation2021) in this issue. Their work demonstrates the historicity of this minor architecture, which is, like squatter occupations, often seen as bereft of memory and incompatible with heritage.

The work of maintenance is crucial to counterinfrastructures and minor architectures alike and this has an important social dimension. Since a large part of infrastructural maintenance and domestic construction in marginal places has to be done collectively, networks of cooperation and solidarity emerge (Reilly Citation2019) – which are not incompatible with internal conflict and violence. Thus, talking about poor neighbourhoods in Djakarta, Abdoumaliq Simone (Citation2016: 45) notes that ‘residents remain attuned to each other through their very efforts to make, repair, and sustain the connections among these urban resources’. An ethos of maintenance, repair and do-it-yourself, in fact, permeates all the materiality of subaltern assemblages, in which systematic recycling is the norm (Reilly Citation2016) ().

Figure 3. From a subaltern assemblage: soles made with rubber tires documented in a forced labour camp of the 1940s established for building The Valley of the Fallen, a fascist monument near Madrid. Author’s figure.

Subaltern assemblages are essentially hybrid. This has to do both with the logic of making do, which does not reject anything a priori that can be used, and also with a lack of social constraints related to cultural and symbolic capital. Marginalised people have no fear of sanction due to what might be perceived as failed experimentation and appropriation. There are specific materialities of the subaltern, which are well known for historic times (such as colonowares and spongewares), but they also have access to goods used by other social groups, which give their assemblages a haphazard look. Their use can be allodoxic (with no political intent), but also heterodox and subversive – see Lemos and Budka (Citation2021), in this issue, for examples in ancient Nubia.

Marginal and illicit economies

Marginal places are usually economically marginal (or perceived as marginal) as well. Here, we should distinguish between marginal and illicit economies. The former are peripheral to the productive system, although complementary and often essential to mainstream economies – it can be hunters in an agricultural society or scrap dealers in an industrial economy. They are usually disparaged and socially constructed as dirty, polluting, demeaning or simply of inferior status. This is the case, for example, of castes associated with specific forms of labour in India and Africa, including tanning, blacksmithing and pottery-making, which are conducted in spatially marginalised neighbourhoods or villages. They are, however, accepted as bona fide forms of livelihood and some occupations perceived as socially marginal or even polluting (such as blacksmithing) are not necessarily associated with lower social status or economic standing. Illicit and illegal economies are also practiced by marginal groups, but they fall outside the law or the prevailing moral order (Hartnett and Dawdy Citation2013).

Marginal economies have elicited some attention among archaeologists: this is the case with different forms of pastoralism, hunting and foraging, which often develop in terrains – such as deserts, wetlands or mountainous areas – that are inappropriate for other subsistence practices. Thus, marginal landscapes have been studied in the ancient Mediterranean, characterised by thin soils, limited water resources, and brushwood (Badan, Brun, and Congès Citation1995; Varinlioğlu Citation2007; Perego and Scopacasa Citation2018). Here the economic dimension is, again, intertwined with the symbolic, as those who engage in marginal activities are constructed by those living in hegemonic centres as savages or (at best) strangers, whom they despise, fear and need simultaneously. This is further emphasised by their often peripatetic nature – think of the Roma in Europe, the Tuaregs in Africa or the Birhor in India (Berland and Rao Citation2004). Contemporary hunter-gatherers exemplify well this type of subaltern identity associated with marginal landscapes: they have usually been forced into inhospitable areas where other livelihoods are not viable. Similar situations may have occurred in the past: processes of imperial and state expansion drove populations from fertile lands and squeezed them into marginal territories, where they had to develop new subsistence practices, often successfully and for long periods of time (Perego and Scopacasa Citation2018).

Other forms of marginal economies and identities develop in terrain that is not naturally marginal, but whose soil has been deteriorated by poor management practices. What is often disregarded is that overexploitation is frequently driven by external forces: thus, limitations to nomadism in East Africa enforced by colonial and postcolonial regimes frequently led to overgrazing and soil depletion, which have been blamed on pastoralists alone, in turn resulting in further social stigmatization (Boles et al. Citation2019). Specific marginal identities exist directly associated with waste: entire communities have developed around urban garbage and periurban landfills in Africa, Asia and South America, whose members eke out a living in toxic environments sorting through the waste of others (Chalfin Citation2019; Papoli Citation2021, this issue). While the contemporary era has seen a proliferation of these groups associated with garbage, they were not unknown in the past, as shown by the Dalit in India, whose origins can be traced back centuries ago (if not millennia).

We could even consider as marginal economies those that are strongly associated with power, but are carried out in peripheral regions by subaltern groups. These include different practices developed in frontiers of extraction, such as mining, trapping or sealing, which have been historically associated with marginal (even disreputable) identities (Zarankin and Senatore Citation2005; Vilches and Morales Citation2017; Stewart, Gokee, and De León Citation2021, this issue). Here marginal and illicit economies – like prostitution, smuggling and brigandage – coalesce. Although part of state-based and capitalist economies, those who engage in those practices often develop identities and materialities, which are more typical of non-state and non-capitalist groups, such as foragers or nomads. Indeed, in some places, it is the same actors that take part in preindustrial and industrial economies in the periphery: it is the case with herders in the Atacama Desert, in Chile (Vilches and Morales Citation2017). Informal economies that develop in slums or slave quarters should also be considered here. More than just economic practices, they are social activities that involve the production and exchange of material culture and that have the potential to create ties and reinforce a sense of identity (Reilly Citation2019).

Peripheral spaces are also suited to illicit and illegal economic practices, including smuggling, moonshining, poaching, prostitution and piracy, which take place in sequestered landscapes and sites that facilitate evasion (Hartnett and Dawdy Citation2013, 43). As marginal and illegal economies share peripheral space, those who practice them are often conflated (e.g. foragers depicted as brigands). Some illicit practices, such as prostitution, may take place at the heart of the city, but often in areas that are considered marginal, socially and spatially. This is the case with harbours and port districts from antiquity to the present, which are typically seen as disreputable places (Falck Citation2003; Schofield and Morrissey Citation2005). Engaging in illicit economic practices may be a form of resistance and from this point of view they become part of a moral economy: this is what happened with illegal distilleries in the Scottish Highlands during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (Given Citation2004, 151–160). Distilling whiskey in secluded moors was highly profitable, but it was also a way of resisting excessive taxes, protesting massive clearance, reinforcing solidarity and cooperation within the community, and keeping alive a landscape that was full of meaning and memories.

The politics of marginal places: from confinement to liberation

Insofar as marginal places produce marginal identities and vice versa, they have political effects. How these marginal identities are produced depend to a large degree on whether the margin has been chosen or forced upon. From this point of view, we can define two broad categories of marginal places: margins of confinement, whose mission is to control subaltern communities, and margins of liberation, which act as refuges for communities and individuals that opt to evade the dominant order. The former, which coincide with Bauman’s ‘emic spaces’ (Bauman Citation2000, 101) and Foucault’s ‘heterotopias of deviation’ (Foucault Citation1986), comprise all those sites that enable the management of populations that are marginal or that a regime of power wants to marginalise. In them, people are simultaneously excluded, expelled and watched over. Here, we have an array of institutions that were deployed from the late eighteenth century and that, as Foucault (Citation1975) famously showed, include prisons, sanatoria, asylums and hospices (Casella Citation2007), and to which concentration and refugee camps are added from the late nineteenth century onwards (Myers and Moshenska Citation2011).

Several of the contributions to this themed issue deal with this type of margins of confinement (Hamilakis Citation2021; Connolly Citation2021; Lau-Ozawa Citation2021), which explain how these places produced specific subaltern identities. At times, the purpose is to defuse the socially subversive potential of certain groups: thus, immigrant depots in Australia were aimed at neutralizing the perceived dangers of single female migrants (Connolly Citation2021). In the case of the transit centres described by Lau-Ozawa (Citation2021), we have the first step of a chaine operatoire of marginalization, which intended to both control the Japanese American collective and alienate them from the rest of the nation. Yet the work of marginalization can be challenged through the creation of new forms of solidarity and resistance among the confined (Hooks Citation1989, 20), which often entail sensuous material practices. These include cooking, eating and sharing food in the case of the refugee camp of Moria in Lesvos (Hamilakis Citation2021) and gardening among Japanese Americans during the Second World War (Ozawa Citation2016).

Margins of confinement are not necessarily surrounded by fences and walls: limits are marked in many other ways, too. ‘To be in the margin’, wrote hooks (Citation1989, 20), is to be part of the whole but outside the main body. As black Americans living in a small Kentucky town, the railroad tracks were a daily reminder of our marginality. Across those tracks were paved streets, stores we could note enter, restaurants we could not eat in, and people we could not look directly in the face”. A similar distinction is drawn by Fanon (Citation2004, 4) between colonists’ neighbourhoods and those of the colonised: the latter is ‘a world with no space; people are piled on top of the other, the shacks squeezed tightly together. The colonized’s sector is a famished sector, hungry for bread, meat, shoes, coal, and light. The colonized’s sector is a sector that crouches and cowers’. One does not need high walls to know the limits of one’s world. Slums and poor quarters, as those studied by Papoli (Citation2021) or Matila, Hyttinen and Ylimaunu (Citation2021). in this issue, are as much margins of confinement as an internment camp, if we look at their role of social seclusion and stigmatization.

Margins of confinement can be interior – like ghettos, asylums or clandestine detention centres – or exterior – such as places of exile, internment and refugee camps or plantations and company towns in frontiers of extraction. It is not only the living who are confined in margins, though: it is often the case that marginalisation in life entails marginalisation in death. Semple and Brooks (Citation2020, 9) talk about ‘necrogeographies of exclusion’ in which burial rites are used to segregate or marginalise individuals and communities. This was the case with wetlands or bogs in the case of late prehistoric Europe and in more recent times with peripheral areas in cemeteries where the poor, criminals, people with disabilities or suicides were buried. Márcia Hattori (Citation2020), for instance, has shown for the case of contemporary Brazil how social marginalisation is enacted in death as much as in life, through a combination of bureaucratic violence and material and spatial practices (undressing of corpses that leads to anonymization, use of plastic bags for disposing of human remains, mass graves).

In stark opposition to margins of confinement are those of liberation. These are spaces to which oppressed groups and individuals flee to achieve a life in liberty that is impossible in the midst of mainstream society. Perhaps the best examples are maroon settlements (Goucher and Agorsah Citation2011; Weik Citation2012). They were located in peripheral, inaccessible regions (mountains, forests, swamps), although not necessarily very far from the main populated areas – in parts of South America, in fact, maroon settlement covered an important proportion of the territory nominally belonging to the colonial powers. They were hybrid worlds in which a diversity of people cohabited, including fugitive slaves, indigenous people and low-class members from mainstream society (Funari Citation1999). In the case of Jamaica, for instance, remote hideouts in the Blue Mountains became first the refuge for Taino people escaping the Spanish invasion and then received fugitive slaves, who might have coexisted with the Taino (Goucher and Agorsah Citation2011, 148).

Similar to maroon settlements are places of refuge used by people fleeing raids, war, or State depredations. They have been documented in Africa during the second millennium AD, where they grow in parallel to an increase in slave raids against small-scale indigenous societies living in state peripheries (Kusimba Citation2004; González-Ruibal Citation2021), but examples can be found in prehistoric contexts as well: Gary Webster (Citation2021), for instance, has recently suggested that the site of Biriai in Sardinia, a late third-millennium BC site, could be identified as a refugee settlement. He bases his hypothesis in the inaccessible location, artificial defences and the pottery found at the site. The latter includes traditions from a variety of regions in the Island (which would be consistent with different communities coming together under threat) and a new hybrid style, which would have emerged as a result of the new social situation.

At times, margins of liberation are not the result of forced displacement, but of a desire to improve oneself or society – what Foucault (Citation1986, 26) called ‘heterotopias of compensation’. Here, we have both hippie communes and hermits. While only the hippie commune can be strictly considered a political project, they coincide with hermits and ascetics in seeking remoteness, natural environments and release from a cumbersome material world (Fowles and Heupel Citation2013). As for hermits, the margins of (spiritual) liberation they choose usually coincide with those of other marginal communities, such as nomads and brigands, with whom they have not always cohabited peacefully (Fournet Citation2018). However, it is the mixture of collectives with different backgrounds that has the potential to produce new hybrid cultures and political imaginations.

Margins of liberation are often difficult places to live, in challenging environments and under constant threat from the nearby centres of power. Yet they are at the same time places of promise and experimentation, where new cultures and social orders can be created, often lastingly. This, however, can also happen in margins of confinement: Papoli (Citation2021, this issue) tells how in the impoverished District 14 in Tehran new alliances, solidarities and forms of political consciousness emerge. Slums, thus, can foster intense and radical cultural creativity, which in turn help produce positive forms of marginal identities and political resistance: margins, then, become ‘spaces of refusal’ from which to say ‘no to the coloniser, no to the downpressor’ (Hooks Citation1989, 21). Bell Hooks argued against seeing the margins only as deprivation, which leads to nihilism. She distinguished between imposed marginality and that marginality one chooses as site of resistance: a ‘location of radical openness and possibility’ (Hooks Citation1989, 23). While not many subalterns are in a position to choose, they may still transform their margins into spaces of political and cultural possibility.

They may even occupy the centre. Marginal lives are not necessarily condemned to peripheries or invisibility. The case of squatter occupations mentioned above is a good example of margins establishing a new political project in the centre, a resolution of antagonisms – using Bernbeck’s concept (Citation2019) – to the advantage of the subaltern. This is the case with the pastoralists that occupied elite buildings in seventh-century BC Iran (Bernbeck Citation2019) or the Kura-Araxes people described by Greenberg (Citation2021) in this issue, a ‘society against the state’, who settled in an urban context in the third-millennium BC Levant.

Conclusions

‘Living as we did – on the edge’, writes Hooks (Citation1989, 20), ‘we developed a particular way of seeing reality. We looked both from the outside in and from the inside out. We focused our attention on the centre as well as on the margin. We understood both’. Looking at margins, as bell hooks reminds us, is not just a matter of social justice or of paying attention to people and places that have been disregarded. It is surely all of this. But it is also a way of seeing both margins and centres under a different light. In this introduction to the issue on the archaeology of marginal places and identities, I have emphasised places, since their role in producing subaltern identities and subjectivities, while being of paramount importance, has been less frequently addressed per se in archaeology. Indeed, places are all too often dealt with as mere containers or scenarios and taken for granted. As I have tried to show here and as is evident in the contributions to the issue, their material and spatial qualities are fundamental as much in making marginal identities as in subverting them. Marginal places can be constructed by power to confine, exclude and control subaltern groups, such as immigrant centres and ghettos, but they can also be spaces where the same groups find freedom and where they can develop new political systems and economies – maroon settlements are the best example. Yet margins of confinement can also hold the potential for liberation, slums can be centres of political struggle and abandoned places occupied by squatters or nomads sites of cultural creativity. Marginal places, both margins of confinement and of liberation, can thus become foci of resistance, where hegemonic space is challenged, repressed antagonisms exposed, and new identities, political imaginations and networks of solidarity created. For this, people resort as much to social tactics as to material and spatial ones: they reshape places, adding and subtracting artefacts, substances and matter, and they make homes out of ruins and wastelands. The articles in this issue evince similarities in the use of space and in the configuration of subaltern assemblages in different periods and regions, from the squatters of third-millennium BC Levant to the slums of Tehran today. They encourage us to think margins and the marginalised as places and people with history and identity.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank to anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments that have helped improve this article. Any errors remain my own.

References

- Anfray, F. 2012. “Matara: The Archaeological Investigation of a City of Ancient Eritrea.” Palethnologie 4: 11–48.

- Augé, M. 1995. Non-places: Introduction to an Anthropology of Supermodernity. London: Verso.

- Badan, O., J. P. Brun, and G. Congès. 1995. “Les bergeries romaines de la Crau d’Arles: Les origines de la transhumance en Provence.” Gallia 52 (1): 263–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.3406/galia.1995.3152.

- Bauman, Z. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Bauman, Z. 2004. Wasted Lives: Modernity and Its Outcasts. Oxford: Polity.

- Berland, J. C., and A. Rao, Eds. 2004. Customary Strangers: New Perspectives on Peripatetic Peoples in the Middle East, Africa, and Asia. Westport, CN: Greenwood.

- Bernbeck, R. 2019. Squatting’in the Iron Age: an Example of Third Space in Archaeology. eTopoi. Journal for Ancient Studies 8: 1–20.

- Boles, O. J., A. Shoemaker, C. J. C. Mustaphi, N. Petek, A. Ekblom, and P. J. Lane. 2019. “Historical Ecologies of Pastoralist Overgrazing in Kenya: Long-term Perspectives on Cause and Effect.” Human Ecology 47 (3): 419–434. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-019-0072-9.

- Bradfield, J., and M. G. Lotter. 2021. “The Current Occupation of Kruger Cave, a Later Stone Age Site, South Africa.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 8 (1): 1–20. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.43377.

- Bryning, E., Kendall,C.,Leyland, M., Mitman, T. & Schofield, J. 2021. Fame and recognition in historic and contemporary graffiti: examples from New York City (US), Richmond Castle and Bristol (UK). World Archaeology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2022.2035802.

- Casella, E.C. 2007. The Archaeology of Institutional Confinement. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida.

- Chalfin, B. 2019. “Waste Work and the Dialectics of Precarity in Urban Ghana: Durable Bodies and Disposable Things.” Africa 89 (3): 499–520. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0001972019000494.

- Connolly, K. 2021.

- Connor, K. 2021. ‘‘to make the Emigrant a better Colonist’: Transforming Women in the Female Immigration Depot, Hyde Park Barracks’. World Archaeology.

- Dawdy, S. L. 2010. “Clockpunk Anthropology and the Ruins of Modernity.” Current Anthropology 51 (6): 761–793. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/657626.

- de Solà-morales, I. 2013. “Terrain Vague.” In Terrain Vague: Interstices at the Edge of the Pale, edited by M. Mariani and P. Barron, 24–30. London: Routledge.

- Delgado Hervás, A. 2010. “De las cocinas coloniales y otras historias silenciadas: Domesticidad, subalternidad e hibridación en las colonias fenicias occidentales.” Sagvntvm 9: 27–42.

- Dodd, J. 2019. “A Conceptual Framework to Approaching Late Antique Villa Transformational Trajectories.” Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology 6 (1): 30–44.

- Falck, T. 2003. “Polluted Places: Harbours and Hybridity in Archaeology.” Norwegian Archeological Review 36 (2): 105–118. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00293650310000641.

- Fanon, F. 2004. The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

- Farley, P., and M. S. Roberts. 2012. Edgelands: Journeys into England’s True Wilderness. London: Random House.

- Foucault, M. 1975. Surveiller et punir. Naissance de la prison. Paris: Gallimard.

- Foucault, M. 1986. “Of Other Spaces.” Diacritics 16 (1): 22–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/464648.

- Fournet, J. L. 2018. “The Eastern Desert in Late Antiquity.” The Eastern Desert of Egypt during the Greco-Roman Period: Archaeological Reports. edited by J.-P. Brun, T. Faucher, and B. Redon, 1–19. Paris: Collège de France.

- Fowles, S., and K. Heupel. 2013. “Absence.” In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Contemporary World, edited by P. Graves-Brown, R. Harrison, and A. Piccini, 178–191. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Funari, P. P. A. 1999. “Maroon, Race and Gender: Palrnares Material Culture and Social Relations in a Runaway Settlement.” In Historical Archaeology: Back from the Edge, edited by P.P.A. Funari, M. Hall, and S. Jones, 308–327. London: Routledge.

- Gilroy, P. 1993. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso.

- Given, M. 2004. The Archaeology of the Colonized. London: Routledge.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2019. An Archaeology of the Contemporary Era. Abingdon: Routledge.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2021. “The Cosmopolitan Borderland: Western Ethiopia C. AD 600–1800.” Antiquity 95 (380): 530–548. doi:https://doi.org/10.15184/aqy.2021.23.

- González-Ruibal, A. 2022. “Excavating Europe’s Last Fascist Monument: The Valley of the Fallen (Spain).” Journal of Social Archaeology 14696053211061486.

- Goucher, C., and K. Agorsah. 2011. “The Significance of Maroons in Jamaican Archaeology.” In Out of Many, One People: The Historical Archaeology of Colonial Jamaica, edited by J.A. Delle, M. Hauser, and D.V. Amstrong, 144–160. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Greenberg, R. 2021. “Fragments of an Anarchic Society: Kura-Araxes Territorialization in the Third Millennium BC Town at Tel Bet Yerah.” World Archaeology 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999855.

- Hall, M. 1999. “Subaltern Voices? Finding the Spaces between Things and Words.” In Historical Archaeology, edited by P.P.A. Funari, M. Hall, and S. Jones, 213–223. London: Routledge.

- Hamilakis, Y. 2017. “Archaeologies of Forced and Undocumented Migration.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3 (2): 121–139. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/jca.32409.

- Hamilakis, Y. 2021. “Food as Affirmative Biopolitics at the Border: Liminality, Eating Practices, and Migration in the Mediterranean.” World Archaeology 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.2021980.

- Hansson, M., Nilsson, P., & Avensson, E. 2020. Invisible and ignored: The archaeology of nineteenth-century subalterns in Sweden. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 24(1): 1–21.

- Harrison, R., and J. Schofield. 2010. After Modernity: Archaeological Approaches to the Contemporary Past. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hartnett, A., and S. L. Dawdy. 2013. “The Archaeology of Illegal and Illicit Economies.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 37–51. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-anthro-092412-155452.

- Hattori, M. L. 2020. “Undressing Corpses–An Archaeological Perspective on State Violence.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 7 (2): 151–168.

- Hingley, R. 2005. Globalizing Roman Culture: Unity, Diversity and Empire. London: Routledge.

- Hooks, b. 1989. “Choosing the Margin as a Space of Radical Openness.” Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media 36: 15–23.

- Kiddey, R. 2017. Homeless Heritage: Collaborative Social Archaeology as Therapeutic Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kusimba, C. M. 2004. “Archaeology of Slavery in East Africa.” African Archaeological Review 21 (2): 59–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/B:AARR.0000030785.72144.4a.

- Lau-Ozawa, K. 2021. Conglomerate infrastructures: ordinary sites used for extraordinary regimes of power. World Archaeology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2022.2035804.

- Lekakis, S. 2019. “The Archaeology of In-between Places: Finds under the Ilissos River Bridge in Athens.” Journal of Greek Media & Culture 5 (2): 151–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1386/jgmc.5.2.151_1.

- Lemos, R., and J. Budka. 2021. “Alternatives to Colonization and Marginal Identities in New Kingdom Colonial Nubia (1550–1070 BCE).” World Archaeology 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999853.

- Leone, M. P., P. B. Potter Jr, and P. A. Shackel. 1987. “Toward a Critical Archaeology.” Current Anthropology 28 (3): 283–302. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/203531.

- Lewit, T. 2003. “‘Vanishing Villas’: What Happened to Élite Rural Habitation in the West in the 5th-6th C?” Journal of Roman Archaeology 16: 260–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S104775940001309X.

- Marín-Aguilera, B. 2021. Subaltern Debris: Archaeology and Marginalized Communities. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 31(4): 565-580.

- Matila, T., Hyttinen, M. & Ylimaunu, T. 2021. Privileged or dispossessed? Intersectional marginality in a forgotten working-class neighborhood in Finland. World Archaeology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2022.2035803.

- Montón-Subías, S., and B. Dixon. 2021. “Margins are Central: Identity and Indigenous Resistance to Colonial Globalization in Guam.” World Archaeology 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999851.

- Mullins, P. R. 1999. “Race and the Genteel Consumer: Class and African-American Consumption, 1850–1930.” Historical Archaeology 33 (1): 22–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03374278.

- Myers, A., and G. Moshenska, Eds. 2011. Archaeologies of Internment. New York: Springer.

- Nordin, J. M., L. Fernstål, and C. Hyltén-Cavallius. 2021. “Living on the Margin: An Archaeology of a Swedish Roma Camp.” World Archaeology 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999852.

- Orser, C. E. 1996. A Historical Archaeology of the Modern World. Boston, MA: Springer.

- Ozawa, K. H. 2016. The archaeology of gardens in Japanese American incarceration camps. Master’s Thesis, San Francisco State University.

- Papoli, L. 2021. The archaeology of a marginal neighborhood in Tehran, Iran: garbage, class, and identity. World Archaeology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2022.2036634.

- Perego, E., and R. Scopacasa. 2018. “The Agency of the Displaced? Roman Expansion, Environmental Forces, and the Occupation of Marginal Landscapes in Ancient Italy.” Humanities 7 (4): 116–137l. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/h7040116.

- Reilly, M. 2019. “Intimacies and Attachments: Households and Hucksters on a Barbadian Plantation.” In The Historical Archaeology of Shadow and Intimate, edited by J.A. Nyman, K.R. Fogle, and M.C. Beaudry, 138–157. Gainesville: University of Florida Press.

- Reilly, M. C. 2016. ““Poor White” Recollections and Artifact Reuse in Barbados: Considerations for Archaeologies of Poverty.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 20 (2): 318–340. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0339-4.

- Santacreu, D. A. 2021. “Under the Bridge: Estudio Autoarqueoetnográfico de Un Espacio Intersticial En la Mallorca Supermoderna.” Complutum 32 (1): 191–215. doi:https://doi.org/10.5209/cmpl.76454.

- Schofield, J., and E. Morrissey. 2005. “Changing Places–archaeology and Heritage in Strait Street (Valletta, Malta).” Journal of Mediterranean Studies 15 (2): 481–495.

- Semple, S., and S. Brookes. 2020. “Necrogeography and Necroscapes: Living with the Dead.” World Archaeology 52 (1): 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2020.1779434.

- Silliman, S. 2010. “Indigenous Traces in Colonial Spaces: Archaeologies of Ambiguity, Origin, and Practice.” Journal of Social Archaeology 10 (1): 28–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1469605309353127.

- Simone, A. 2016. “The Uninhabitable? in between Collapsed yet Still Rigid Distinctions.” Cultural Politics 12 (2): 135–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/17432197-3592052.

- Singleton, T. 1995. “The Archaeology of Slavery in North America.” Annual Review of Anthropology 24 (1): 119–140. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.001003.

- Smith, M. E. 2010. Sprawl, squatters and sustainable cities: Can archaeological data shed light on modern urban issues? Cambridge Archaeological Journal 20(2): 229–253.

- Sneed, P. 2008. “Favela Utopias: The” Bailes Funk” in Rio’s Crisis of Social Exclusion and Violence.” Latin American Research Review 43 (2): 57–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/lar.0.0031.

- Soto, G. 2016. “Place Making in Non-places: Migrant Graffiti in Rural Highway Box Culverts.” Journal of Contemporary Archaeology 3 (2): 121–294.

- Spencer-Wood, S. M., and C. N. Matthews. 2011. “Impoverishment, Criminalization, and the Culture of Poverty.” Historical Archaeology 45 (3): 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03376843.

- Stewart, H., C. Gokee, and J. De León. 2021. “Counter-infrastructure in the US–Mexico Borderlands: Some Archaeological Perspectives.” World Archaeology 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2021.1999854.

- Stoner, J. 2018 [2011]. Hacia una arquitectura menor. Trans. L. Jalón Oyarzún. Madrid: Bartlebooth.

- Strother, Z. S. 2004. “Architecture against the State: The Virtues of Impermanence in the Kibulu of Eastern Pende Chiefs in Central Africa.” The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians 63 (3): 272–295. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/4127972.

- Tejerizo García, C., P. Fermín Maguire, R. G. Coelho, and C. Marín Suárez. 2017. “¿Excepción o normalidad? Apuntes para una arqueología de los centros de internamiento extranjeros (CIE).” ArkeoGazte: Revista de arqueología-Arkelogia aldizkaria 7: 123–148.

- Van Dommelen, P. 2019. “Rural Works and Days–a Subaltern Perspective.” World Archaeology 51 (2): 183–190. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2019.1704570.

- Varinlioğlu, G. 2007. “Living in a Marginal Environment: Rural Habitat and Landscape in Southeastern Isauria.” Dumbarton Oaks Papers 61: 287–317.

- Vilches, F., and H. Morales. 2017. “From Herders to Wage Laborers and Back Again: Engaging with Capitalism in the Atacama Puna Region of Northern Chile.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 21 (2): 369–388. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-016-0386-x.

- Webster, G. 2021. “Biriai: A Possible Refugee Settlement in Late Third-Millennium Bc Sardinia.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 34 (1): 3–27. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/jma.43200.

- Webster, J. 2001. “Creolizing the Roman Provinces.” American Journal of Archaeology 105 (2): 209–225. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/507271.

- Weik, T. M. 2012. The archaeology of antislavery resistance. Gainesville, FL: The University of Florida Press.

- Welsby, D.A. 1998. Soba II: Renewed Excavations within the Metropolis of the Kingdom of Alwa in Central Sudan. London: British Museum Press.

- Worsham, R. 2021. “Squatters’ Rights: Questioning Narratives of Decline in Archaeological Writing.” Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 34 (2): 141–164. doi:https://doi.org/10.1558/jma.21978.

- Yamin, R. 2005. “Wealthy, Free, and Female: Prostitution in Nineteenth-century New York.” Historical Archaeology 39 (1): 4–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03376674.

- Zarankin, A., & Senatore, M. X. 2005. Archaeology in Antarctica: nineteenth-century capitalism expansion strategies. International Journal of Historical Archaeology 9(1): 43–56.

- Zarankin, A., and C. Niro. 2009. “The Materialization of Sadism; Archaeology of Architecture in Clandestine Detention Centers (Argentinean Military Dictatorship, 1976–1983).” In Memories from Darkness, edited by P.P.A. Funari and A. Zarankin, 57–77. New York: Springer.

- Zimmerman, L. J., C. Singleton, and J. Welch. 2010. “Activism and Creating a Translational Archaeology of Homelessness.” World Archaeology 42 (3): 443–454. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00438243.2010.497400.