ABSTRACT

Tehran’s Archaeology of Garbage project was conducted in 2017–2018 and with the initial aim of monitoring the impacts of currency devaluation on poor people. In Districts 7 and 17, the team investigated two of the most decayed urban fabrics of Tehran as well as the garbage bags of 1004 poor marginalized families. Among these, we managed to find evidence of a forgotten social group, the ‘impoverished middle class’ which consisted of people from the middle-class background who had to move to a neighborhood occupied by low-income classes. The garbage-making behaviors of these two communities were tracked and led to a better understanding of demographic changes and recent protests. In this article, I will present the evidence of poverty in District 17 and will open a new debate on the poor middle-class emerging community and its influence on the new identity of the people living in District 17.

Introduction

Ignorance of low-income and marginalized communities for a long time has made the analysis of social incidents like the 2019 Iran protests difficult. Most of the evidence and data gathered from Iran’s current situation and justifications based on them are related to the middle classes (see. Hashemi Citation2020, 50; Morady Citation2020; Gheissari Citation2009). Seemingly, the focus of sociologists and thinkers on the well-off and middle classes is not merely due to their research interests but rather the policies of Iran’s government that have been more effective by oppressing researchers who work on poverty (for example, the imprisonment of Saied Madani and dismissal of Saied Moiedfar, both sociologists).

Tehran’s Archaeology of Garbage project supported by Tehran municipality appears to be one of the exceptions. The initial aim of the project was to investigate the harsh impact of currency devaluation in 2017 on low-income and middle classes. Later, the project developed into a more analytical approach with the purpose of studying the voiceless communities that advocated for change. Through the mentioned project, my team and I had the opportunity to meet, study, and interview communities living in two districts of Tehran: Districts 17 and 7.

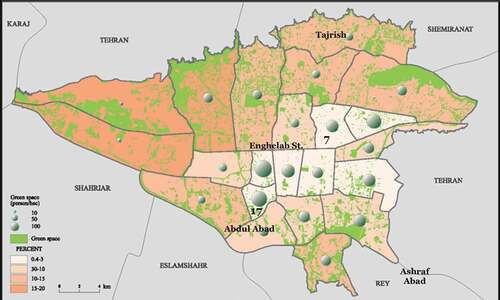

During two seasons, the garbage bags of 1004 families were studied and documented. Among these, the families inhabited in District 17 () are mostly from working and low-income classes. The district is located in the southwest of the city and is well-known for being the most impoverished and having the most decayed urban fabric () among 22 districts of Tehran (see. Dezhamkhooy and Papoli-Yazdi Citation2020a).

Figure 1. The map of Tehran with mentioned locations and population density. (Tehran Municipality, https://atlas.tehran.ir/Default.aspx?tabid=318).

Through investigating the garbage bags of the inhabitants of District 17, the material indicators of the changes in demographic patterns of poor classes (see Salehi-Isfahani Citation2009) appeared. These indicators are the main topic of this article. In this article, a new debate will be opened up arguing that the political and economic pressures of the last decade have made the poor much poorer, and the middle classes vulnerable and exhausted. Concealed from eyes but hidden in the garbage, new types of integration and symbiosis are being developed side by side with new identities and classes.

Methodology

Since the 1970s has modern garbage been studied by archaeologists and under a particular title, garbology, as developed by William Rathje (Rathje and Murphy Citation2001). His garbage project was conducted in Tucson, Arizona and the initial aim was to help build universal principles of human behaviors in addition to demonstrating usefulness of archaeological methods and theory (Rathje and Murphy Citation2001), waste degradation process and pollution that also was led to figure out the relation between consumption and social status (see Reckner and Brighton Citation1999; Schiffer Citation2015). Archaeology of garbage provides researchers with significant information about the daily life of ordinary people because there is less censorship or secrecy involved (Rathje and Murphy Citation2001). Rathje’s project showed that discarded objects can tell a story wildly different from the one reported by consumers (González‐Ruibal Citation2014, 1691). Strikingly, the studies led by Rathje were on both landfills and fresh garbage dumped by families (Rathje et al. Citation1992).

This method of garbology remained dominant in the topical research literature from the early 1970s till the 2000s. In the 2000s and after the emergence of debates on environmental change, garbology has been again applied by archaeologists and cultural anthropologists, but this time, in a novel way (Sosna and Brunclíková Citation2016; Brunclíková Citation2017). Our recent research on the garbage of lower and middle classes in Tehran is methodologically close to the recent archaeology of waste and garbage projects conducted on daily household garbage.

In 2017 and after the sharp devaluation of the Iranian Rial as well as the economic downfall, we witnessed that novel different faces of poverty appeared very suddenly in the cities. Considering that the diet of impoverished people had changed drastically after the downfall, we concluded that we could record the economic status of the people as well as what they ate daily from studying their waste disposal.

The Archaeology of Garbage with focus on daily household garbage in Tehran was conducted in two seasons in two different districts of the city, Districts 7 and 17 in winter of 2017 and spring of 2018 (Papoli-Yazdi Citation2018).

Each street has a container in which people dumped their garbage bags (). We managed to collect the household garbage daily from each neighborhood for 2 weeks to figure out the daily diet and waste disposal of the families living in the target streets. The benefit of this method was that we could spend long hours in the neighborhoods, meet and interview the people when disposing of their daily garbage and ask them for permission to visit their residence area.

Figure 4. Garbage containers and the dry garbage collected by garbage collectors (Photo: Tehran’s Archaeology of Garbage Project).

This procedure gave us the opportunity to observe the environment of each neighborhood and figure out how much people care about the hygiene of the area. The team was divided into two groups, each consisting of two archaeologists, a photographer, and a sociologist to interview the inhabitants. The team’s working hours were flexible and depended on the waste disposal attitudes of the inhabitants in each neighborhood and the time they were used to throw away their garbage, usually between 11 a.m. to 10 p.m. We used to open the bags, classify the discarded garbage, and list every item based on assumed codes in our databases (). According to Rathje (Rathje and Murphy Citation2001), we arranged 181 codes for dry and wet waste to record every piece of the garbage in our forms. Each family, garbage bag, and avenue also got their own codes to be recognized in the database. Later, another form was created to document the notable findings, such as blood and urine, that we went through without any previous knowledge in the garbage bags.

Figure 5. Opening and classifying the garbage bags, filling the forms, and coding the avenue and the discarded items (Photo: Tehran’s Archaeology of Garbage Project).

We managed to ask the informants semi-structured questions and listen to them as long as they would like to continue. Most of the informants were women. We conducted 65 interviews with families and shopkeepers, 8 with garbage collectors as well as 11 child workers from District 17 in the city center. The interviewer would explain the whole process of the research to the informants and assure them that the interviews would be published without addressing their real names.

The garbage containers are normally emptied twice per day in District 17, once by garbage collectors and the next time by Municipality garbage disposal vehicles. To find the intact containers, we used to ask the garbage collectors who are mostly Afghan teenagers.

Tehran’s plan has been divided into 22 districts from north to south. The wealthier people live in Districts 1 and 2. The center of the city (District 6–10) has been occupied by governmental offices, ministries, and residential areas of the middle classes and employees. Reportedly, Districts 12 and 17 are where poor people, refugees, and subaltern communities live.

Working in District 17 was suggested to us by sociologists and urban experts at the municipality. A year later, massive civil unrest against the government happened in Tehran. Comparing the slogans with the previous demonstrations in poor areas, the activists and some scholars concluded that the 2019 demonstrators’ demands represented drastic social changes (Madani et al. Citation2020; KWA, Citation2021).

Studying the daily household garbage showed two different patterns of garbage-making behaviors in the district. The presence of one of these communities, the impoverished middle class, remained hidden from the eyes of the scholars.

In this article, I argue that the increasing poverty and the replacement of the population have affected both the garbage-making behaviors and demographic patterns. Obviously, the social transformations are more complicated to be elucidated just by a small-scale garbology project. In these terms, the current article only attempts to propose one of the possible parameters of change observable through studying waste and garbage.

A brief history of district 17

Since 1785, Tehran has been the capital of Iran. Its development during the first two centuries of its life as the capital has been gradual. With the rise of modern power structures from 1925, the rate of change in the population of the city increased rapidly. Since the first four decades of the 20th century till the end of the Second World War, the population of the city doubled. By 1976, the four and a half million inhabitants of Tehran comprised 12% of the total population of the country and 32% of the total urban population (Grigor Citation2016, 364)

Before the Pahlavi dynasty (1925–1979), the country was not centralized but by discovering oil in southwestern Iran, the economic system changed to a more centralized one. Before, the traditional economy was very much based on taxes collected from farmers, governmental farms (Khaleseh), and trade (Abrahamian Citation2008). The harsh changes after the two world wars, including dearth, occupation of the country by the allied forces, and mass immigration to and from Iran, put their impact on the plan and social structure of the capital.

In 1963, the land reform law was issued and according to the law (Majd Citation1987), the ancient feudal system of farming was expired. The land reform was followed by waves of immigration of villagers to the cities. Tehran grew suddenly and more than 20 marginalized districts (Bayat Citation1997) were added to its plan. The southern regions of Tehran were gradually occupied by immigrants from Azerbaijan, Qazvin, Khorasan, and Zanjan provinces during the 1960s and 70s. According to interviews, a couple of years before the land reform and during the 1950s, some families immigrated from Azerbaijan to Tehran and bought some gardens around the city that were later transformed into the apartments and houses of District 17. According to municipality, the current population of the district is 348,589 individuals (75,872 families). Through the interviews, we learned that the people living in District 17 consist of different communities: Azeris, Qazvinis, Gilaks, and Afghans. The oldest residents of the district, as mentioned before, are Azeris (from Northwestern Iran) and the most recent inhabitants are Afghan refugees. Geographically, the first occupied areas of the district are eastern and northern ones while the southern parts where the Afghan refugees live, seem to have been occupied recently during the last decade.

Five zones of District 17 and the studied daily garbage

Usually, except for the plastic items that would be sold to the garbage collectors, the other dry and wet garbage are collected in the same garbage bags. In this article, I consider food waste that makes up for the major proportion of discarded garbage (more than 40% of daily garbage). The main reason for focusing on food waste is that, based on previous studies, the decline of the household economy of ordinary Iranians is observable in drastic changes to diet (Kimiagar and Bazhan Citation2003). For instance, anemia has been observed in 40% of the children under 2 years of age while 11% of children under 5 years of age in the country suffer from moderate and severe underweight (ibid; Khodadad-kashi and Heidari Citation2002). On the other hand, food is a significant parameter to investigate the effects of poverty on the everyday life of the working class. Based on the 2020 workers’ wage limit, 94.5% of the monthly family salary (with an average of four members) should be spent to support a very simple basic diet (Iribnews Citation2021). To figure out the socioeconomic condition of the district, we divided it into five different zones (). In this article, we will discuss three of these zones since Zone 4 and 5 have been shaped around a holy shrine and a shopping center and do not include residential areas. The first zone includes the southern areas of Ziaeeyan hospital, Behboudi street, and its parallel avenues. The communities living in this area are mostly Turkish-speaking (Azeri and Qazvini) and it seems that they have been the first citizens who have occupied the district. Their community is comprised of different colonies of patrilineal families who live in the same or neighboring apartments based on their relationships. According to the interviews, the inhabitants consider the families living in the northern avenues to be wealthier than the people living in the southern avenues. They reported that the reason for their being wealthier is that some of them have sold their farms in Azerbaijan or have worked as workers in Japan (there was a wave of temporary immigration of workers from Iran to Japan during 1990s) or have been involved in some criminal activities such as drug production.

Most of the houses in the first zone have been renovated. Except the avenues leading to Abouzar Street, the other avenues have a less decayed urban fabric. The shops are located along Behboudi street; the only confectionary shop of the district, restaurants, car clinics and paint shops, as well as small supermarkets were all observed in Behboudi and Abouzar streets that have divided the district into northern and southern parts. In this zone, men work during the day and women are less frequently observed outside their domestic spaces.

Classification of wet garbage showed that the people living in this zone usually do not eat lunch and instead, try to compensate their needed energy by eating dinner. They are mostly not rich enough to buy red meat. Interviews with two vendors and four housewives indicate that in March, people prefer to buy cheap fresh vegetables rather than other foods ().

People living in Behboudi street had eaten red and white meat in comparison with the people living in other streets. The only shops in the neighborhood selling white meat were located on this street. Interviews with the sellers show that people are less inclined to buy internal organs such as liver and prefer to purchase the whole chickens.

The amount of consumption and the average weight of garbage bags in Zone 1 decrease from north to south. The most consumption amount was observed in the north of Behboudi street with 1.3 kg and the least in southern avenues with 800 g.

Zone 2 is a neighborhood located between Sajjad and Zamzam streets and Baharan Cultural center. The inhabitants of Zone 2 have moved to this area during the last three decades. According to the interviews, employees of some governmental institutions such the municipality and Zeeayian hospital, teachers, and some people who are from the middle-class background and used to live in the middle-class neighborhoods live in this zone. From an ethnic viewpoint, Azeri, Gilaki (from northern Iran), and Qazvini communities live in the area. Unlike Zone 1, these people have occupied Zone 2 in two separate waves of immigration; the first one occurred in the 1960s, a short time after the land reform and the second one was reportedly a post 1979-revolution wave.

From the inhabitants of the zone who had immigrated to Tehran as a consequence of land reform, four families were interviewed. From these families, one had moved to Tehran from Neyshabour city located in the northeast of Iran. They had sold their farmlands for a small amount of money. With this money, they had been able to purchase a garden in District 17 which later, its function changed into residential area. Later, two of their sons had got married and moved to the new apartment built by their parents in the same district.

Two other families had immigrated to Tehran from Qazvin province due to drought and environmental changes that had decreased their earnings from agriculture. The parents of one of these families lived in the same apartment with their sons and daughters-in-law. From the second family, two sons had moved to Jannat Abad, a neighborhood located in the north of District 17.

The fourth family was from Gilan province, had moved to Tehran after the land reform, and had experienced substantial changes. Of the four families, the last one was the lowest-income family. The husband was a worker who had lost vision of his both eyes after a job accident. He was not able to work anymore, and this put lots of pressure on the wife’s shoulders. Two of these families indicated that parts of their daily food, such as rice, were provided from their hometowns.

From the second group of inhabitants, we interviewed two families. Both had immigrated from Gilan (Northern Iran) to Tehran in the first years after the 1979-revolution with the purpose of seeking a job. Three generations of these families lived as extended families in the same apartments. Like the mentioned families, the Gilani community provided some items needed traditionally for their daily consumption such as rice and fish from Gilan. Both families indicated that they had lost part of their income in the last couple of years and had gotten poorer in comparison with the 1980s.

We met three other families who mentioned the 1990s post-Iran-Iraq war environmental changes as the main reason for immigration to Tehran. By selling their properties in their hometowns, they had saved enough money to buy a small land in Tehran and build an apartment for themselves and their sons.

The environment of Zone 2 is the cleanest. Because of being close to the Cultural Center, there are more green spaces and a park nearby where children play. The shops along Sajjad street consist of small supermarkets that sell daily consumer products. In the northern corner of the Cultural Center, two high schools and two kiosks that offer newspapers and journals are located.

Compared to the other zones, more food has been dumped in Zone 2 (). Nevertheless, observing less amount of meat might be attributed to the daily jobs of the inhabitants who more often work outside the district and eat lunch at their offices. As mentioned above, the number of both male and female employees living in Zone 2 is more than the other zones of the district.

Zone 3 is from Zamzam Street to the southern avenues of the first zone. Turkish people and Afghan refugees have shaped the communities of Zone 3. Moreover, there are also very few people living in Zone 3 who have recently moved from other neighborhoods to District 17 due to the economic decline of the last couple of years, bankruptcy, and currency devaluation. Zone 3 is the filthiest zone of the district. The containers get filled before noon and even some garbage bags were seen to be dumped outside the containers on the surface of the street.

In this zone, inhabitants did not hesitate to show their houses to the team experts. Seemingly, part of the insalubrity issues of the district is related to the attitudes of the inhabitants towards hygiene and dirt. In three observed houses, there were no partitions between working, living, and playing spaces. Mice were observed in the basement of most of the decayed and old houses. The very unstable residences also have been occupied by the inhabitants who usually do not pay attention to the hygiene of their places. Regarding the interviews, these people feel that they should move again in only few couple of months and do not feel integrated and belonged to the neighborhood.

Observations and contents of garbage bags proved that drug addicts and people involved in some sort of criminal activities tend to live in Zone 3. We witnessed very violent fights and prostitution in the area every day of our presence in the neighborhood. The interview with shop keepers in grocery stores indicated that the average amount of purchasing is 100,000 Rials per purchase (0.4 US Dollars). They also admitted that most of the buyers prefer cheap snacks. The diversity of goods offered in the grocery stores in this zone was less than any other zones and were only limited to two brands of diaries and snacks.

The amount of medicines’ consumption was doubled in Zone 3 in comparison with Zones 1 and 2 (). However, the evidence of drug abuse was observable both in interviews and garbage (4 garbage bags contained remains of opium and grass). Our team working in the west of the zone observed sex workers working in streets while studying the garbage bags (Dezhamkhooy and Papoli-Yazdi Citation2020).

Figure 7. Medicines dumped in a garbage bag, Zone 3 (Photo: Tehran’s Archaeology of Garbage Project).

According to observations, most of the male inhabitants are jobless and spend all day in the zone. The neighborhood is very crowded in the daytime except for very warm hours between 2 and 4 p.m. Children play amongst dust and garbage. Evidently, there is a complete absence of physicians’ offices, governmental buildings, police, and other systems providing service to the citizens in this zone.

I interviewed eleven child workers in Enghelab Street (city center) from which nine were inhabitants of District 17,Zone 3. The average age of these children was ten and they worked as vendors or garbage collectors ().

Figure 8. Afghan children collecting garbage, District 17 (Photo: Tehran’s Archaeology of Garbage Project).

In the south of Zamzam street, car clinics and car paint shops are located. The workers working in these shops commute from other districts of the city to District 17 and complain about the condition of the neighborhood. It seems that the establishment of the metro-station has led the people to extend their geography of coming and going. Before the establishment of the metro-station, they barely went any further north than Enghelab Street but now it takes them only 30 min to reach Tajrish, in the north of Tehran.

Observation in District 17

In a general view, the number of governmental buildings in the district decreases from north to south. In the southern zones of District 17, no police stations, banks, municipality offices, or healthcare centers were observed which reinforces the assumption that parts of the district are self-regulating and out of the sight of the state. Interviewing two police officers, we learned that they prefer not to interfere in the southern streets, and their duty is mainly based on controlling the situation of northern streets. The only governmental buildings of the district are all located along Abouzar street including Ziaeeyan hospital, schools, and municipality offices. In the southwest of the district, Baharan Cultural Center and a few banks represent the difference between Zone 2 and Zone 3. These institutions appeared in the area after the establishment of a new bazaar of furniture (Yaft Abad) in the western part of the district. The new bazaar has broken apart the traditional order of the district. It is worth mentioning that none of the shareholders or shopkeepers chose the district as their residence.

After the increase of population in Tehran, car clinics were opened in many subordinated districts. This job does not require many professional skills and on the other hand, produces lots of waste and pollution. Due to all these, the people living in wealthier districts are not interested to in having these shops around. In Zones 2 and 4, there are several shops related to the car service industry. The garbage bins around the car clinics are full of harmful stew, a mixture of motor oil and other chemical substances used to repair car engines.

According to the observations and interviews, the chronology of moving to the district has a meaningful relationship with poverty, waste disposal behavior, and attitudes toward hygiene and dirt.

The communities that have a longer history of living in the district, as well as the families who own a residence in the area, are more well-off and care more about the hygiene of the neighborhood they live in. In contrast, immigrants and unstable population who have less sense of belonging to the neighborhood are under more economic pressure and live in filthier places. Regarding waste disposal and garbage-making attitudes, the newcomer community consisting of people with the middle-class background also behave the same as immigrants.

Drug abuse and prostitution remain obvious indicators in the garbage bags. No traces of alcohol consumption were found which, according to interviews, may be due to the drinking patterns. We were told that people of the district produce and drink alcohol in common bottles and glasses that are not separable from the other dishes. The material indicators of prostitution were also recorded in Zones 3 and 4 (Dezhamkhooy and Papoli-Yazdi Citation2020).

Besides the harsh poverty, it seems that one of the major dietary problems of the people of the district is due to their priorities. Even for the people who have a higher level of income, eating a sufficient amount of food is more important than its (dietary/nutritious) quality. As a result, comfort food such as snacks, chips and cheese puff are more consumed than other groups of food like diaries.

Anomaly

Documenting the garbage bags in the north of Abouzar Street (Zone 1), the experts found that consumption of paper increased in this zone and was doubled in comparison with the other neighborhoods. To investigate these differences, we interviewed the staff of three real estate agencies. We realized that the population combination of the neighborhood had changed in the last decade gradually. The new tenants, mostly jobless educated people, included teachers, unemployed workers, bankrupt businessmen had lost the possibility to rent a place in more expensive districts due to the economic crisis of the last decade.

The real estate agencies usually suggest that the newcomers rent a place in the western alleys of the district that are safer from their point of view. Evidently, the lifestyle of this community is not consistent with their neighbors and even with the other group of immigrants from northern districts who live in Zone 3.

Living in particular alleys, the mentioned community has established isolated Islands where the garbage-making attitudes are not identical with those of the lower class but are closer to the attitudes of the people living in northern districts of the city. In contrast, these people’s consumption behaviors are very similar to their lower-income neighbors and show consistency. Rice and meat consumption is very low in both groups (only 4% of the families have eaten meat in 2 weeks). However, the difference between the poor middle class and their neighbors is that they consume more diaries and fewer snacks (less than half of the average in other zones) and pay more attention to hygiene. Their neighborhood is the only one in the entire district that has a newspaper kiosk.

The female members of these families work more out of home or are university students (more than 14%,the average in Iran is 12.8%) while men do not hesitate to care for the children (for the statistics of women’s employment in Tehran, see. Habibi and Hourcade Citation2004). Regarding the geography of the city, they are more aware of how extended and stratified the city is. However, they have adopted some characteristics of the working class. They are as straightforward as their poorer neighbors are, have deep knowledge and consciousness about poverty and discrimination and it seems that they prefer not to censor or conceal the bitterness of their situation.

Putting all these observations together indicates that a new community is emerging in the district that combines the characteristics of both working and middle classes and is somehow responsible for a peculiarly local type of dialogue (observation, monitoring and learning from each other) between two communities. Regarding the interviews, this new community has its influence on the conservative and religious thoughts of working classes while on the other hand, the low-income class has its own impact on daily life and attitudes of the newcomers. For example, renting flats by university students in Abouzar street was followed by changes in the clothing of the women living in the district. The poor middle-class experiences mainly nostalgia about old (better) days, a concept that is now being circulated among the other inhabitants of the district regarding the possibility of a better life. Despite the growth of this community during the last decade, very few attempts have been made to investigate poor middle-class new lifestyle. Step by step, they have lost their voices and have been victimized by oblivion and ignorance- the same fate as their neighbors.

Towards developing new forms of resistance

D. has a degree in sociology and lives in District 17. He lost his job as a researcher in 2016 and moved to this neighborhood after he learned that he could not pay the rent of his apartment in District 6 anymore. In this district, he does daily jobs as a worker and frequently collects information about the social climate of the neighborhood. He suggests that District 17 is stratified based on different socioeconomic communities. Agreeing with D., an undergraduate student of history stated that the establishment of a newspaper kiosk is an indication of the needs of the new inhabitants of the district.

In our interviews, a senior man, one of the oldest inhabitants of Zone 3 who immigrated to Tehran in the 1970s, revealed that, at first, he did not have a favorable opinion about the attitudes of the newcomer girls but later he had found out that they respected social norms and principles in their own way. ‘Now, I see them the same way as I see my own daughters!’ he stated.

According to the interviews, it seems that the older generation of the district has been kept isolated from the other districts of the city in a long-term process. In proportion to population, the northern zones of the district have had the most martyrs in Tehran during the Iran–Iraq war (almost all the alleys are named after the martyrs whose families used to live in the district) and due to their constant contribution to war, they have been the target of propaganda for many years. On the other hand, the middle class has nothing to do with the district. NGOs define their field of duty in more marginalized districts and most of the workshops held in the Cultural Center are aimed at improving skills such as sewing and cooking and not cultural or educational ones. The long-term silence between these two groups, besides propaganda and isolation, has led to the development of the idea of ‘enemy’ and the repetition of the cycle of isolation.

An agent of a real estate agency admitted that his colleagues and he feel responsible to recommend some particular avenues to the people of middle-class background and university students when they are asked for advice on renting flats. These avenues are cleaner, and, from the viewpoint of the agent, fewer people involved in crime and drugs live in these areas. The interviews with some female inhabitants revealed that their feeling about the newcomers is a combination of fanaticizing their previous status and sympathy. Some regretted that these people had lost their ‘better life’ and had to move to District 17.

On the other hand, the lifestyle of the newcomers is changing very rapidly. A woman whose employee husband has lost his job after the currency devaluation stated that she has learned how to consume less from some women in the neighborhood.

In a nutshell, the newcomers are adjusting to their new situation by changing their assumed lifestyles while the district and its older inhabitants attempt to help them to adjust with their new status by providing their requested services such as newspapers, journals, and new brands of fruit.

Discussion: garbage, class, and identity

In his book, Street Politics: Poor People’s Movements in Iran (1997), Asef Bayat illustrates the condition of marginalized neighborhoods in a time span very close to the 1979 revolution. He states that most of these areas were developed after the 1963 land reform when mass immigration from villages to cities like Tehran happened. Bayat (Citation1997) and Rahnama (Citation1996) assume that the agency of middle-class leftists was more in changing the regime than the low-income marginalized communities. The paradoxes grew after the revolution and caused the brutal oppression of leftists and the rise of fundamental Islamists. To seize power, the Islamists propagated that they would eradicate poverty but later, despite the contribution of marginalized people in the Iran–Iraq war and cooperation of more traditional masses in the process of Islamists rise to power, soon the state forgot the destiny and situation of poor classes. Consequently, the unsatisfaction appeared very soon after the end of the war.

Mass unrest in the city of Arak caused hundreds of people to be arrested or detained. But the most dramatic civil unrest took place in the city of Mashhad in 1992, and Islamshahr (one of Tehran’s marginalized areas) in 1995 (Bayat Citation2000). The protests were brutally suppressed, and many were arrested, and some executed. But all these brutalities did not prevent the repetition of the demonstrations in the next decades. In 2009, the oppression of the middle classes did not spread to marginalized areas. Despite the fact that many of the students and intellectuals involved in the Green Movement were from working-class background, the relationship between poor and Middle classes happened barely in the 2009 post-election demonstrations (see. Karimi Citation2018).

Nine years later and after the currency tumbled, the inflation went up and the protests raised in several cities of Iran. This time, it was the middle class that did not pay a price to support the lower classes (see. Madani et al. Citation2020). But a year later, the flame of the demonstrations flared up after the government decided to increase the price of petrol in November 2019. This time the slogans pointed directly to the harsh situation of the poor people and invited the middle classes to participate in the protests. The protests extended in Tehran to the southern districts and across District 17. The demands of the protesters were reflected in their slogans: bread, employment, freedom (see Karami Citation2019).

The geography of 2019 unrests (Islami and Rahimi Citation2020), shows that this time both low-income and part of the middle classes were involved in the demonstrations. The protests continued in 2020 and 2021 while the slogans developed and solutions to the environmental crisis and shortage of water were demanded on a large scale for the first time (Falakhan 198 Citation2021).

Besides the development of social media, one very effective parameter to social change is that more people from the poor districts could continue their education in the universities during the last two decades. The increasing unemployment rate encourages young people to make themselves busy with studying. Having a degree does not guarantee their employment but changes the lifestyle of young people. Another factor is the establishment of the underground metro, which has facilitated the traffic in the previously isolated districts. Some inhabitants travel every day to the north of the city (Tajrish, ) to work as daily workers or peddlers. Metro has made the encounter of poor classes with the rich easier.

When discussing discrimination, the informants compare their own neighborhoods with what they observe in northern districts. However, poverty has changed the city’s plan as well. In the last two decades, the middle classes have been forced to adopt a new lifestyle in symbiosis with other communities. In this situation, we should consider that the women who have no choice to be employed in formal markets and businesses have started to use their skills, sell their homemade products, and travel in the city (see Papoli-Yazdi et al. Citation2021) in order to survive in the current harsh economic situation.

It is obvious that the long-term policies of isolation of classes and keeping them within the assumed borders of their districts have been defeated.

To predict the future unrests and transformations, we need a more thorough study of the poverty patterns. But what is clear today is that the symbioses between the classes resulted in new discourses and lifestyles. Studying the mechanism of oppression shows that the state seems to be aware that it has lost its place among those people who reinforced its empowerment during the 1980s. Now, it is the poor who are protesting isolation and propaganda and being oppressed even more brutally than the middle classes.

Archaeologically speaking, the different waste disposal attitudes of communities not only reveal the class stratification but also may contain the indicators of demographic changes (see. Hosseini-Chavoshi and Abbasi-Shavazi Citation2012). It is of note that investigating the garbage potentially highlights the ignored topics that researchers should consider in order to reach a better understating of social transformations. In the time of dictatorship and when people do not feel safe, they start to hide many aspects of their everyday life (habits such as drinking alcohol, sexual relationships, reading books banned by the government, etc.) particularly when they are from minority, different genders, and refugee communities. Revealing the reality of their lives may bring them serious consequences which ends up to punishment (see. Papoli-Yazdi Citation2010).

The people from the middle classes who have lost their privilege (e.g. Hashemi Citation2012) also hide their identities usually. Being different in their new neighborhood may raise questions about their background and political viewpoint. Based on this fact, it seems that one of the only possible ways to track them and configure their situation is to study their waste disposal.

According to interviews, both communities feel that they have been trapped in a situation that has been made by the government. They both acknowledge that ‘the better life’ is possible and are trying to transform their critical condition and achieve that idealized type of life even by taking the risk of losing their lives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Leila Papoli-Yazdi

Leila Papoli-Yazdi is a researcher at the department of Cultural Sciences, Linnaeus University. She is an archaeologist of recent past. Since 2003, she concentrated on disaster archaeology of Bam, a city destroyed dramatically by an earthquake. Afterwards, she directed several projects in Pakistan, Kuwait, and Iran. The main themes of her studies are oppression, gender, colonialism, and violence. Email: [email protected]

References

- Abrahamian, Ervand. 2008. A History of Modern Iran. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bayat, Asef. 1997. Street Politics: Poor People’s Movements in Iran. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bayat, Asef. 2000. Social Movements, Activism and Social Development in the Middle East. Geneva: United Nations Research Institute for Social Development.

- Brunclíková, Lenka. 2017. “Waste and Value in the Post-socialist Space.” Anthropologie 55 (3): 385–398.

- Dezhamkhooy, Maryam, and Leila Papoli-Yazdi. 2020. “Unfinished Narratives. Some Remarks on the Archaeology of the Contemporary past in Iran.” Archaeological Dialogues 27 (1): 95–109. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203820000112.

- Dezhamkhooy, Maryam, and Leila Papoli-Yazdi. 2020a. “Flowers in the Garbage: Transformations of Prostitution in the Late 19th-21st Centuries in Iran.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 24 (3): 728–750. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10761-020-00541-z.

- Falakhan 198. 2021. Water Crisis, Communes, and Isfahan’s Unrest (A Manifesto). Accessed 9 February 2022. http://manjanigh.de/ (in Persian)

- Gheissari, Ali. 2009. Democracy in Iran: History and the Quest for Liberty. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- González‐Ruibal, Alfredo. 2014. “Contemporary Past, Archaeology of The.” In Encyclopedia of Global Archaeology, edited by Claire Smith, 1683–1694. New York: Springer.

- Grigor, Talinn. 2016. “Tehran: A Revolution in Making.” In Political Landscapes of Capital Cities, edited by Jessica Joyce Christie, Jelena Bogdanović, and Eulogio Guzmán, 347–376. Colorado: University Press of Colorado.

- Habibi, Mohsen, and Bernard Hourcade. 2004. The Atlas of Tehran Megacity. Tehran: Tehran Municipality center for GIS. in Persian.

- Hashemi, Manata. 2012. Social Mobility among Poor Youth in Iran. A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Satisfaction of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology. Berkeley:, CA: UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations.

- Hashemi, Manata. 2020. Coming of Age in Iran: Poverty and the Struggle for Dignity. New York: University of New York press.

- Hosseini-Chavoshi, Meimanat, and Mohammad Abbasi-Shavazi. 2012. “Demographic Transition in Iran: Changes and Challenges.” In Population Dynamics in Muslim Countries, edited by Hans Groth and Alfonso Sousa-Poza A, 97–115. Berlin: Springer.

- Iribnews. 2021. What is the Cost of Food for a Family of 4 Per Month? Accessed 9 February 2022. https://tinyurl.com/ym7ejnej (in Persian).

- Islami, Ruhallah, and Ahmad Rahimi. 2020. “Policymaking and Water Crisis in Iran.” Siyasthay-e Kalan va rahbordi 7 (27): 410–435. in Persian.

- Karami, Naser. 2019. Iran’s Demonstrations: The Comparison between the Geographical Context of 2017 and 2019 Demonstrations. BBC Persian. https://www.bbc.com/persian/blog-viewpoints-50758203.

- Karimi, Maral. 2018. The Iranian Green Movement of 2009: Reverberating Echoes of Resistance. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Khodadad-kashi, Farhad, and Khalil Heidari. 2002. “Estimating the Level of Food Security of Iranian Households Based on the AHFSI Index.” Eghtesad, Keshavarzi and Tousee’ 12 (48): 155–166. in Persian.

- Kimiagar, Seyed Masoud, and Marjan Bazhan. 2003. “Poverty and Malnutrition in Iran.” Refah-e Ejtemaii 5: 91–111. in Persian.

- KWA (Khatoun-Abad Workers Association). 2021. “Here Is Chahardangeh Not Islamshahr!” Falakhan 188: 3–12. http://manjanigh.de/) (in Persian.

- Madani, Saied, Mohammad Amin Zandi, Asma Saremi, Amir Hossein Gholamzadeh Natanzi, Atiyeh Malek Zahedi, Zahra Movahedi Sajedi, Hamid Reza Nazari, and Sepideh Yadegar (2020) Unburning Fire: A Report on November 2019 Unrests. Tehran: Rahman Institute. (in Persian)

- Majd, Mohammad Gholi. 1987. “Land Reform Policies in Iran.” American Journal of Agricultural Economics 69 (4): 843–848. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1242196.

- Morady, Farhang. 2020. Contemporary Iran: Politics, Economy, Religion. Bristol: Bristol University Press.

- Papoli-Yazdi, Leila. 2010. “Public and Private Lives in Iran: An Introduction to the Archaeology of the 2003 Bam Earthquake.” Archaeologies 6 (1): 29–47. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11759-010-9127-7.

- Papoli-Yazdi, Leila. 2018. Garbology Project in Tehran, Districts 7 and 17 (Report). Tehran: Tehran Urban Research and Planning Centre (TUPRC). in Persian.

- Papoli-Yazdi, Leila, Maryam Dezhamkhooy, Omran Garazhian, Hassan Mousavi-Sharghi, and Gohar Soleimani Rezaabad. 2021. Homogenization, Gender and Everyday Life in Pre- and Trans-modern Iran an Archaeological Reading. Münster: Waxmann.

- Rahnama, Saied. 1996. The Revival of Social Democracy in Iran? Stockholm: Baran. (in Persian).

- Rathje, W L., W W. Hughes, D C. Wilson, M K. Tani, G H. Archer, R G. Hunt, and T W. Jones. 1992. “Reports, the Archaeology of Contemporary Landfills.” American Antiquity 57 (3): 437–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0002731600054330.

- Rathje, William L., and Cullen Murphy. 2001. Rubbish! the Archaeology of Garbage. Tucson: University of Arizona Press.

- Reckner, Paul E., and Stephan A. Brighton. 1999. “Free from All Vicious Habits:Archaeological Perspectives on Class Conflict and the Rhetoric of Temperance.” Historical Archaeology 33 (1): 63–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03374280.

- Salehi-Isfahani, Djavad. 2009. “Poverty, Inequality, and Populist Politics in Iran.” The Journal of Economic Inequality 7 (1): 5–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10888-007-9071-y.

- Schiffer, M.B. 2015. “William Laurens Rathje: The Garbage Project and Beyond.” Ethnoarchaeology 7 (2): 179–184. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/1944289015Z.00000000034.

- Sosna, Daniel, and Lenka Brunclíková, eds. 2016. Archaeologies of Waste: Encounters with the Unwanted. Barnsley: Oxbow Books.