Abstract

The present contribution provides a conceptualization of teacher emotions rooted in appraisal theory and draws on several complementary theoretical perspectives to create a conceptual framework for understanding the teacher emotion–student outcome link based on three psychological mechanisms: (1) direct transmission effects between teacher and student emotions, (2) mediated effects via teachers’ instructional and relational teaching behaviors, and (3) recursive effects back from student outcomes on teacher emotions, both directly and indirectly via teachers’ appraisals of student outcomes and their correspondingly adapted teaching behaviors. We then present a tour d’horizon of empirical evidence from this field of research, highlighting valence-congruent links in which positive emotions relate to desirable outcomes and negative emotions to undesirable outcomes, but also valence-incongruent links. Last, we identify two key challenges for teacher emotion impact research and suggest three directions for future research that focus on measurement, research design, and an extended scope considering emotion regulation.

We all remember “those” teachers. The one teacher who was cheerful most of the time—sometimes painfully so, when our adolescent lethargy made it hard to keep up with their vigor in the early morning hours—but mostly luckily so. As students, we came to look forward to their highly engaging lessons, the topics they presented seemed interesting to us, and we came to see the subject matter they taught as meaningful. But we also remember that other teacher, who tended to react overly angrily to student disruptions, sometimes provided quite cynical answers to student questions, and was otherwise emotionally distant. As students, we loathed that teacher’s lessons, felt intimidated by them, and came to dislike the subject. The present contribution applies an educational-psychological perspective to capture the phenomena that were just described narratively: Teacher emotions in the classroom and their implications for students.

Evidence on teacher emotions and their implications is rapidly growing. However, perhaps because the field is still in its infancy, the questions driving teacher emotion research have been fairly simplistic and overwhelmingly unidirectional. Specifically, the unspoken assumption that teachers are the starting point of the links between teacher emotions and student outcomes seems to require reflection. In this article we intentionally consider, articulate, and conceptualize teacher emotions as part of a system that influences and is influenced by student outcomes, including students’ own emotions, cognitions, and behaviors, because teachers and students are jointly embedded in the school environments. To depict this system, we offer a conceptual framework on teacher emotion—student outcome links that can catalyze future research questions and methodologies. This conceptual framework goes beyond earlier work on teacher emotions which so far predominantly focused on appraisal antecedents of teacher emotions (Chang, Citation2013; Frenzel, Citation2014), the social, cultural, and political factors relevant to teacher emotions (Fried et al., Citation2015), or isolated emotional phenomena such as teacher enthusiasm and their effects in the classroom (Keller et al., Citation2016). In contrast, the presented conceptual framework digs deep into links between teacher emotions and student outcomes, and integrates across several psychological processes underlying these links. We also identify specific challenges facing the field and suggest ways to tackle them. In particular, we propose that the field may be advanced by integrating the topic of emotion regulation. The main objective of this article is to broaden the unidirectional thinking that has dominated the field thus far and encourage researchers to consider teacher emotion—student outcome links from multiple angles.

Conceptualization of (teacher) emotions

Definition

Emotions are highly elusive constructs that are both challenging to define scientifically and to capture empirically. In line with a majority of emotion researchers, we view emotions as the interface between an individual and their environment, continually mediating between events and social contexts and the individual’s responses and experiences. We adopt a multi-componential definition, proposing that emotions can be understood as synchronized, coherent patterns of central nervous and peripheral-physiological reactions that are reflected in action tendencies and facial, vocal, and gestural expressions that are integrated into subjective experiences (Mulligan & Scherer, Citation2012; Scherer & Moors, Citation2019). For example, in a moment of anger, a person will feel highly negatively aroused and the urge to “fight” the aversive stimulus that arouses their anger, while frowning and making menacing gestures. Emotions thus have important motivational implications because they can instigate and sustain goal-directed activities (Frijda, Citation2013).

We conceptualize teacher emotions as fitting this general definition of evaluative reactions, encompassing various psychological and physical subsystems that are uniquely embedded in the specific events and social contexts teachers encounter in their profession. Teachers interact, among others, with students, parents, colleagues, and superiors to undertake a wide range of task demands such as getting classrooms to function smoothly, students to engage and achieve, parents to be content and supportive, and superiors and colleagues to be satisfied and collaborative. From this perspective, we consent with Schutz et al. who proposed to define teacher emotions as “socially constructed, and personally enacted ways of being that emerge from conscious and/or unconscious judgments regarding perceived successes at attaining goals or maintaining standards or beliefs during transactions as part of social-historical contexts” (Schutz et al., Citation2006, p. 344). The highly contextualized nature of teacher emotions also implies that it is essential to consider important defining context variables. Specifically, mirroring compelling empirical evidence on the domain-specificity of students’ emotions (Goetz et al., Citation2006, Citation2010), teacher emotions have also been shown to be organized domain-specifically. Accordingly, teaching specific subjects or topics arouses specific emotions in teachers that result in them feeling differently across different subjects, or even topics, they teach. For example, Frenzel et al. (Citation2015) have shown that German elementary school teachers reported systematically varying teaching enjoyment and anger when teaching math versus science versus German (i.e., reading and writing). Büssing et al. (Citation2020) explored biology preservice teachers’ anticipated enjoyment for teaching and showed that it was meaningful to differentially assess the enjoyment of teaching about socioscientific issues (i.e., the return of wild wolves) versus health socioscientific issues (i.e., preimplantation genetic diagnosis) versus climate change. Additionally, various other proximal and distal context factors are relevant for teachers’ emotional experiences. For example, secondary school teachers who teach multiple classes during one schoolyear reported systematically varying teaching enjoyment and anger when teaching each group of students (Frenzel et al., Citation2015, Citation2020). Further, teachers’ enjoyment of teaching and emotional exhaustion have been shown to vary depending on teacher team support and schools’ organizational cultures (e.g., Banerjee et al., Citation2017; Keller-Schneider, Citation2018). In sum, we view teacher emotions as subjective experiences involving action tendencies and physiological as well as expressive responses; thus, belonging to the nomological net of basic human phenomena while also being highly contextualized by the unique work of teachers.

State versus trait emotions

A conceptual aspect worth considering in the context of emotions is that they can be understood along a state—trait continuum. Emotional states are very short-lived, momentary experiences. In contrast, when considering emotions as traits, the emphasis is on the fact that some people have the disposition (or “proneness”) to habitually experience certain emotional states more readily and frequently than others. This may apply to them as persons most generally (strict trait), or occur in specific contexts (e.g., high anger proneness in interacting with a specific class). In the existing quantitative literature, teacher emotions are often conceptualized as more trait-like constructs assessed through self-report questionnaires such as the Teacher Emotions Scales (TES; Frenzel et al., Citation2016) or the Teacher Emotion Questionnaire (TEQ; Burić et al., Citation2018). When teacher emotions are approached as more state-like constructs, researchers typically use experience sampling measures (e.g., Becker et al., Citation2015; Carson et al., Citation2010; Chang & Taxer, Citation2020), administer short post-lesson or daily diary questionnaires (de Ruiter et al., Citation2020; Frenzel et al., Citation2015; Keller et al., Citation2018), or conduct interviews in which teachers describe particular episodes of positive or negative emotions with students, colleagues, administrators, and parents (Hargreaves, Citation2000).

Dimensional approach versus discrete emotions

Another conceptual aspect worth considering in the context of emotions is that they can be understood either along dimensions or as discrete entities. Dimensional approaches categorize emotions according to their valence, differentiating between unpleasant/negative and pleasant/positive emotions. Some researchers additionally consider the dimension of arousal (from calm to alert; see e.g. Posner et al., Citation2005). Discrete emotion approaches claim that emotions like joy, fear, anger, or sadness should be considered separately as they are unique experiential states that imply distinct physiological and expressive reactions and action tendencies. This body of literature also proposes the idea of a certain limited number of discrete emotions being “basic,” meaning that they are present from birth and highly universal across cultures (e.g. Keltner et al., Citation2019). Within the literature on teacher emotions, researchers employ both dimensional and discrete emotion approaches. Within the discrete approach, it is worth noting that teacher enjoyment received the most attention, and other discrete emotions, including anxiety, were much less considered. This disparity is surprising because anxiety is by far the most-researched emotion in students (e.g. Pekrun et al., Citation2017). The fact that anxiety received relatively little attention in teacher emotion research may be rooted in both substantive and methodological causes. Students are continually being evaluated at school, which could explain a high potential for achievement anxieties that stem from the constant possibility for failure. In contrast, teachers are not evaluated nearly as often. When teachers are evaluated, it is often in a less institutionalized way with less extreme consequences of failure (however, this is changing with stricter evaluations in some countries such as the US in relation to standardized test scores). As a result, experiences of anxiety may truly not be as salient among teachers as among students. Methodologically, teachers may be more reluctant than students to report their anxieties because of social desirability or self-deception.

Appraisals as key elicitors of emotions

In the present contribution, we take an appraisal-theoretical approach to understanding how emotions are elicited, while also borrowing from the emotion-relevant aspects of attribution theory. Appraisal theory and attribution theory postulate that emotions are primarily caused by individuals’ cognitive judgments about situations and events, rather than by the situations and events themselves (Ellsworth, Citation2013; Moors et al., Citation2013; Weiner, Citation1986, Citation2000). Appraisals are general cognitive judgments about situations and events, such as whether they are considered benign (or goal-conducive) or harmful (or inconsistent with one’s goals). Attributions, more specifically, pertain to judgments regarding the perceived causes of events (for example, can the cause be controlled by the actor). Several authors have deemed appraisal theory a meaningful lens through which teacher emotions can be understood (Chang & Davis, Citation2009; Fried et al., Citation2015; Tsouloupas et al., Citation2010). Frenzel et al. (Citation2020, Citation2009) make specific propositions as to which appraisals are particularly important for teacher emotions. They list appraisals of classroom events concerning the attainment, conduciveness, and importance of teachers’ goals, as well as coping potential and accountability in case of goal non-attainment. They further argue that teachers constantly appraise classroom events in light of four key goals, namely high student performance, motivation, discipline, and high quality of teacher-student relationships. Importantly, the process of emotion elicitation through appraisal describes a phenomenon that operates at specific moments and thus is intuitively linked to more state-like perspectives on emotion. However, appraisal reasoning also applies to links between more general beliefs and trait-like emotions, and it has been shown that appraisal-emotion links apply both within and across persons (e.g. among teachers, Frenzel et al., Citation2020; for a more general overview, see also Murayama et al., Citation2017).

Theoretical pathways from (teacher) emotions to (student) outcomes

Emotions have been shown to have both inter- and intrapersonal functions (e.g. Barrett et al., Citation2016). Interpersonal functions involve effects on the social interaction partners of those who experience emotions; intrapersonal functions involve effects on the individuals who experience the emotions themselves, specifically their cognition, memory, perception, and behavior. Again, emotional functions largely operate at the state level, but corresponding links can also be observed for teachers’ trait emotions and student outcomes such as their beliefs. In the following, we review how teacher emotions, implied by these functions, can be understood to exert direct and indirect effects on students.

Interpersonal functions of teacher emotions

Because of their outward expressions, emotions do not go unnoticed by interaction partners and can thus exert effects on them. Accordingly, once teachers experience and express emotions, those emotions can affect students in at least three ways. First, emotions can directly transmit from teachers to students. Second, teacher emotions are critical in shaping the quality of teacher-student relationships. Third, teacher emotions convey important social messages with potential implications for students’ beliefs.

Direct transmission effects

The idea of emotion transmission or emotional contagion entails that if someone experiences and expresses an emotion in a social context, the same emotion can be induced in their interaction partners. Hatfield, Cacioppo and Rapson argued that emotional contagion involves “the tendency to automatically mimic and synchronize facial expressions, vocalizations, postures, and movements with those of another person and, consequently, to converge emotionally” (Hatfield et al., Citation1994, p. 5). Additionally, interpersonal emotional convergence can be explained by cognitively mediated processes, referred to as social appraisals (Manstead & Fischer, Citation2001). Social appraisal “implies that people take other people’s emotions into account when appraising what is happening” (Parkinson & Manstead, Citation2015, p. 374). For example, one person can “catch” another person’s fear because they appraise a situation as threatening based on the expression on the other person’s face. Alternatively, a person can “catch” interest based on corresponding situation appraisals implied by another person’s curious face. For instance, students’ interest and enjoyment may be sparked by their teachers’ expressed enjoyment and enthusiasm. Conversely, teachers may also “catch” emotions from their students, such as their joy and excitement about a topic or event.

Effects on students via relationship quality

An evolution-theoretical perspective entails that emotions have evolved, in a large part, to successfully navigate the social world (e.g., Fischer & Manstead, Citation2008). Accordingly, human emotions are critically functional for social relationships. Specifically, positive emotions serve to begin, grow, and successfully maintain relationships, whereas negative emotions can have negative consequences for relationship quality (see Yee et al., Citation2014, for a review). By implication, the emotions teachers experience and express in class shape the relationships they build with their students. Joy of teaching and positive affectionate emotional experiences toward students can fuel positive relationships with them and promote supportive ways of instruction. Conversely, teachers who are emotionally exhausted, or overwhelmed by negative emotions, are likely to become less involved, less tolerant, less caring, and by extension the quality of their relationships with students will suffer. Assuming that student well-being and learning are promoted if students have a positive relationship with their teachers (e.g. Kim, Citation2020), the social functions of emotions represent an important theoretical pathway for the effects of teacher emotions on student outcomes.

Effects on students via nonverbal social messages

Attribution theory provides an important framework for understanding that emotions can convey important nonverbal social messages (Weiner, Citation2000). According to this framework, affective communications from others influence causal beliefs. For example, if someone expresses anger toward an interaction partner in the context of a negative event, the interaction partner is more likely to consider that they deliberately caused the event; if someone expresses sympathy, the interaction partner will more likely consider that external circumstances caused the negative event. For teacher-student interactions, such phenomena can manifest in the context of failure feedback (Butler, Citation1994): When the teacher expresses anger about a students’ failure (e.g., by saying, “You failed this. I’m angry with you”), it implies that the teacher believes that the student has sufficient competencies and that the student could have tried harder. In contrast, when the teacher expresses sympathy with a student’s failure (e.g., by saying, “You failed this. I’m sorry for you”), it conveys that the teacher believes that the student lacks the prerequisites to ever succeed. Because teachers are important socializers for students, such affectively communicated competence beliefs can be considered relevant for students’ own belief development.

It is worth noting, though, that these proposed beneficial effects of teacher anger versus sympathy on student outcomes due to underlying attributional processes contradict assumptions based on emotion transmission and relationship-building functions of emotions. While the latter imply valence-congruent effects (positive emotions having favorable effects, negative emotions having unfavorable effects), the effects of emotions as implied by the social messages they convey are valence-incongruent (specifically, the negative emotion of anger implying favorable competence beliefs, and the positive emotion of sympathy implying unfavorable competence beliefs). In sum, this implies that the context in which emotions are expressed matters: For example, anger may have positive effects in feedback contexts, but negative effects in classroom management contexts. As we explain subsequently (see section “A Tour d’Horizon of Existing Empirical Findings” below), the available evidence on the effects of emotionally toned failure feedback on student attributions is rather consistent, but extensions to students’ self-concepts tend to lack empirical support. In contrast, as detailed below, there is consistent empirical evidence on interpersonal functions of emotions via direct transmission and relationship quality.

Intrapersonal functions of teacher emotions: Effects on students via instructional strategies

Emotions affect performance, fueled by a complex array of processes, including self-regulation and attention (e.g. Beal et al., Citation2005). Similarly, according to Fredrickson’s broaden-and-build theory (Citation2001, 2013), positive emotions expand one’s attentional scope and thought-action repertoire. The instructional strategies teachers apply are at the heart of teacher job performance, so corresponding effects can be expected. For example, teachers who experience positive emotions during teaching have access to a wider array of instructional strategies and are more flexible and creative in adapting to different classroom situations, with corresponding conducive effects for student outcomes. In contrast, negative emotions impair performance on complex tasks as they are linked to a shallow and narrow information processing (for a recent meta-analysis on anger and information processing, see McKasy, Citation2020). Accordingly, teachers who experience negative emotions can be more rigid and less ready to implement different instructional strategies.

Then again, the “good and bad” classification of possible effects of teachers’ positive and negative emotions might be overly simplistic and incomplete. Across different domains of psychology, it has often been proposed that factor X increases factor Y to a certain point, after which the X decreases Y. The Yerkes–Dodson law (Yerkes & Dodson, Citation1908) and theories of optimal arousal (Eysenck, Citation1967; Smith, Citation1983) are classic examples of this proposition. Accordingly, it has been shown that there are curvilinear effects of anxiety on academic performance (e.g. Cassady & Finch, Citation2020) and similar curvilinear effects of negative emotions on job performance (e.g. Cheng & McCarthy, Citation2018). Moreover, even positive emotions may have nonmonotonic effects on workplace behavior and performance (e.g. Lam et al., Citation2014). This too-much-of-a-good-thing effect suggests that positive traits, states, and experiences enhance well-being and (organizational) performance to a certain inflection point at which their effects turn negative (Grant & Schwartz, Citation2011; Pierce & Aguinis, Citation2013). This effect is also conceivable for the influence of teachers’ emotions on their instructional strategies.

Recursive effects

The reasoning on inter- and intrapersonal functions of emotions elaborated above provides compelling theoretical underpinnings for the idea that teacher emotions are causally linked with student outcomes. Given that the typical role of teachers is to be the initiating figure for most classroom processes, it seems reasonable that they “cause” or bring into being many events, activities, and student outcomes in the classroom. And yet, we would like to emphasize it is also essential to consider the reverse direction of effects: Students’ individual or class-level characteristics, including their own emotional experiences, level of prior knowledge and performance, as well as motivational, disciplinary, and relational behavior toward the teacher likely exert effects back on teachers. Also claiming this, Nurmi and Kiuru (Citation2015, p. 445) speak of students’ “evocative effects” on their teachers. For teacher emotions in particular, reciprocal causal reasoning has also been detailed in Frenzel et al.’ model (Frenzel, Citation2014; Frenzel et al., Citation2020). In this model, it is proposed that teachers’ appraisals of classroom conditions, specifically with respect to student performance, motivation, discipline, and relational behavior toward the teacher, shape teachers’ emotions, which in turn can be linked with student outcomes. The present contribution also adopts such a reciprocal conceptual framework, arguing that teacher emotions are part of a system that influences and is influenced by student outcomes.

Importantly, recursive effects are highly conceivable for links between teacher emotions and their teaching behaviors too. Teachers’ instructional decisions as well as their relational behaviors likely feed back on how they feel in the classroom. In other words, providing high-quality instruction per se is likely emotionally satisfying, and seeking (and finding) closeness and warmth with students can promote positive experiences. Conversely, delivering dry instruction is likely non-rewarding and boredom-inducing for teachers themselves and may further deplete their emotions and create a sense of distance between students and their teachers.

A conceptual framework on the linking mechanisms between teacher emotions and student outcomes

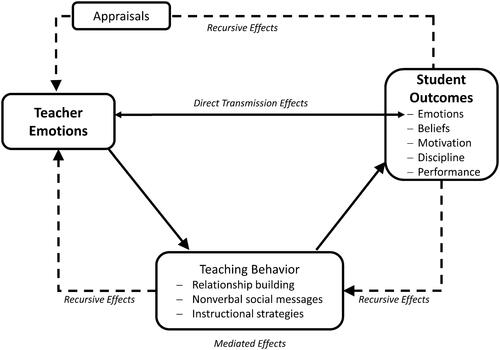

The present contribution rests on a reciprocal conceptual framework for understanding teacher emotion—student outcome links that proposes three key mechanisms (see ). As implied by the intra- and interpersonal functions of emotions described above, we propose that there are (1) direct transmission effects between teacher and student emotions specifically, and (2) mediated effects on student outcomes via relationship building mechanisms, nonverbal social messages, and effectiveness of instructional strategy use. Additionally, we argue that there are (3) recursive effects back from student outcomes on teacher emotions, both directly and indirectly, via teachers’ appraisals of student outcomes and their correspondingly adapted instructional behavior.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework on the links between teacher emotions and student outcomes. Figure available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.14494386.v1 under a Creative Commons Attribution License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

A tour d’horizon of existing empirical findings

As has become evident from the prior sections, there is compelling theoretical reasoning that teacher emotions and student outcomes are systematically linked. Next, we provide a tour d’horizon of existing empirical evidence to summarize typical findings from this field of research. We do not claim this as a conclusive literature review on teacher affective variables and their potential links with student outcomes. We only review studies that conceptualized teacher emotions as either discrete feelings or dimensionally-valenced affective states, in line with our definition of teacher emotions detailed above. With respect to unpleasant teacher experiences, we also report about studies that address the phenomenon of emotional exhaustion, the core subjective affective component of teacher burnout (Maslach et al., Citation2001), but we do not tap into the very rich literature of teacher burnout more generally (for reviews, see García-Carmona et al., Citation2019; Ghanizadeh & Jahedizadeh, Citation2015). With respect to pleasant teacher experiences, we consider studies that address teacher job satisfaction and teacher enthusiasm, but only as long as they operationalize those constructs as explicitly entailing teachers’ experiences of positive affect and/or enjoyment.Footnote1 Regarding student outcomes, these studies considered a range of common variables, including students’ own emotions, their motivational beliefs, classroom behaviors, and scholastic performance.

In keeping with our conceptual model, we first address findings on teacher-student emotion transmission. Second, we consider the evidence for links between teacher emotions and student outcomes, while differentiating between the evidence on valence-congruent and valence-incongruent findings. Third, we cover the evidence on links between teacher emotions and their instructional strategies and relationship building. As will become evident, an overwhelming majority of these existing studies used correlative designs which basically forbid any cause-effect implications. Nevertheless, the authors typically interpret their results according to unidirectional pathways with either teacher emotions or the student outcomes as the origin of the effects. Because the correlative results do not explicitly support any functional relationships between teacher emotions and student outcomes, we intentionally offer possible recursive interpretations of the effects as an important cognitive exercise for researchers to consider.

Evidence on teacher–student emotion transmission

Building on the idea of emotional contagion, researchers have explored potential convergence between teachers’ and learners’ emotional experiences in the classroom. Indeed, there is evidence for covariance between adult English as a Second Language learners’ perceptions of their teachers’ general happiness and cheerfulness during teaching, and the learners’ affective judgments of the teacher and class (Moskowitz & Dewaele, Citation2021). In this study, both learners and teachers were of highly heterogeneous cultural and national backgrounds. Furthermore, Becker et al. (Citation2014) used a series of post-lesson diaries and showed that Swiss secondary school students’ perceptions of their teachers’ enjoyment, anger, and anxiety were related to students’ own reported levels of the same emotions, above and beyond the effects of instructional practices. Replicating this methodology, Tam et al. (Citation2020) extended these findings to the emotion of boredom in teachers and students in Hong Kong mainstream secondary schools. Of note, these studies rest on correlative data from a single source, namely the students. As such, whether they reflect actual processes of direct mimicry or more cognitively mediated processes induced by the messages implied by the teachers’ emotions, or are in fact spurious due to shared third variables such as lesson content or learning climate remains unclear. In addition, it is worth noting that Tam et al. (Citation2020) also assessed teacher-reported boredom, to which both student-perceived teacher boredom and student boredom proved to be unrelated. This implies that the observed links may be more likely socially constructed rather than mimicry-induced. However, any such deliberations are speculative as Tam et al.’s sample size was N = 17 teachers.

Finally, there are two studies that linked teacher-reported and student-reported enjoyment in longitudinal repeated-measures designs in the secondary school context (Frenzel et al., Citation2009; Citation2018). Frenzel et al. (Citation2009) showed that students’ math class enjoyment developed more positively across years 7 and 8 of secondary school if their 8th-grade mathematics teacher reported higher levels of teaching enjoyment. They further showed that the effect of teacher enjoyment on student enjoyment was mediated by student perceptions of teaching enthusiasm, implying that this enjoyment transmission occurred because students could “see” their teacher’s enjoyment through enthusiastic teaching. Frenzel et al. (Citation2018) replicated this mediated effect from teacher enjoyment to student enjoyment via observed teaching enthusiasm in a more heterogeneous secondary school context (multiple subjects, grades 5–9). However, in this study, the positive mediated effect was compensated by a negative direct effect, so the total effect from teacher enjoyment on student enjoyment was zero. Importantly, this study also provided evidence that teachers’ enjoyment developed more positively during the schoolyear when the average class enjoyment was higher at the beginning of the schoolyear. This effect was mediated by teachers’ observations of the students’ engagement in class. These findings imply that emotion transmission between teachers and students is a two-way street: Enjoyment does not only transmit from teachers to students, but also from students to teachers. Notably, this is one of the rare studies explicitly assessing reciprocal links between teachers’ emotions and student outcomes using a repeated-measures cross-lagged design.

Given that these studies used trait-based approaches to teaching and learning enjoyment, they do not provide evidence of emotional mimicry in the classroom. Nevertheless, it seems plausible that moment-to-moment mimicry and week-to-week social interaction developments are the drivers of such observed trait enjoyment convergence across teachers and their students over time.

Evidence on valence-congruent links between teacher emotions and student outcomes

Studies with elementary and secondary school teachers from the Netherlands, Germany, Austria, and Australia have shown repeatedly that teacher-reported enjoyment during teaching is positively correlated with higher teacher ratings of student engagement and discipline and lower teacher ratings of student disruptions (de Ruiter et al., Citation2019, Citation2020; Frenzel et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Hagenauer et al., Citation2015; Martin, Citation2006). While these studies suffer from single-source bias with both teacher emotions and student outcomes being reported from the teacher’s perspective, there is also confirming evidence from large-scale studies that linked teacher emotion ratings with students’ self-reported behaviors. For example, German secondary school teachers’ self-reported enjoyment and class-aggregated student ratings of student misbehavior were shown to be negatively linked (Aldrup et al., Citation2018; Kunter et al., Citation2011). Finally, there is evidence of positive associations between teacher enjoyment/positive emotions and student performance as assessed both through teacher ratings in a German context (e.g. Frenzel et al., Citation2020) and through standardized tests in a US context (e.g. Banerjee et al., Citation2017). Banerjee et al. analyzed the impressively large Early Childhood Longitudinal Study–Kindergarten (ECLS-K) samples and showed that elementary students’ reading (but not math) standardized test achievement growth trajectories were more favorable the more emotionally positive their teachers reported to be. This effect was amplified in contexts characterized by a strong teacher professional community and teacher collaboration.

Paralleling the pattern reported above for pleasant teacher emotions, there are largely negative links between unpleasant emotions and desirable student outcomes and positive links with undesirable student outcomes, specifically student misbehavior. Elevated levels of anger and anxiety reported by German and Austrian teachers were associated with lower teacher-reported ratings of student engagement and performance, and positively linked with teacher-reported student misbehavior (Frenzel et al., Citation2020; Hagenauer et al., Citation2015). Using an idiographic approach, de Ruiter et al. (Citation2020, Citation2019) asked Dutch teachers in grades 3–6 to identify either positive or negative relevant classroom events that were specific to certain students. They found systematic relationships between teachers’ self-reported anger and anxiety and student disruptive behaviors, specifically for events of student hostility and aggression toward the teacher. Importantly, these authors also found that teachers reacted more emotionally negatively to those students whom they had perceived as more disruptive in the past compared to similarly appraised events with students perceived as less disruptive earlier (de Ruiter et al., Citation2020). Of note, the above studies conceptually treated student misbehavior as the independent variable in their analyses, thereby proposing that student misbehavior was a driver of teachers’ negative emotional experiences.

Several further studies explored the linkages between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and student outcomes. For example, Aldrup et al. (Citation2018) used a longitudinal design to show that German secondary school teachers’ perceptions of student misbehavior were positively linked with emotional exhaustion even after controlling for baseline levels of exhaustion measured a year prior. Making arguments in the opposite direction, several studies provide compelling evidence that teacher emotional exhaustion is negatively linked with student performance when separate sources of data (and not teacher reports only) are considered. Arens and Morin (Citation2016) used the PIRLS 2006 German data including elementary teachers and their 4th-grade students and reported negative links between teacher-reported emotional exhaustion and student performance (both teacher-assigned German grades and standardized reading test scores), student school satisfaction, and perceptions of teacher support. Similarly, using multilevel analyses and a large representative sample of German elementary school teachers and their students, Klusmann et al. (Citation2016) demonstrated that teachers’ emotional exhaustion was significantly negatively related to mathematics standardized test scores, even after controlling for teacher characteristics and classroom composition. There is also evidence of links between teacher expressed negative affect and student outcomes across longer periods. In the USA, Hamre and Pianta (Citation2001) showed that if kindergarten teachers reported that their relationship with a child was dominated by negative affect, this negatively predicted student social and academic outcomes through fourth grade.

Overall, there is rather consistent evidence of valence-congruent links between teacher emotions and student outcomes across various learner age groups, cultures, and subject domains, for both pleasant and unpleasant emotions. The reported effects are typically small in size.Footnote2 Of note, secondary school levels and mathematics seem to be addressed most commonly. Many studies also explored links across various subjects and school types. However, they typically do not report their results separately for those different contextsFootnote3 because the sample sizes are limited and most classroom contexts conform to a similar institutionalized norm. By implication, so far there is little evidence of any context-specificity for teacher emotion—student outcome links. Any possible variations of those links may become evident when more specific target groups, contexts, and outcomes are explicitly compared and contrasted.

Evidence on valence-incongruent links between teacher emotions and student outcomes

In line with theoretical reasoning pertaining to emotion-implied nonverbal social messages described above, there are a few experimental studies that systematically manipulated displayed teacher anger versus pity in constructed failure feedback situations (Graham, Citation1984; Rustemeyer, Citation1984; Taxer & Frenzel, Citation2020) and a few studies that used vignettes with participants rating the described student’s attributions and competence beliefs (Hansen & Mendzheritskaya, Citation2017; Taxer & Frenzel, Citation2020; Weiner et al., Citation1982). Although effects are not fully consistent across these studies and are generally small in size, overall, there is support for emotionally toned failure feedback affecting student attributions across age groups (grade 6 through university student age), racial groups (black and white students), and cultural contexts (USA, Germany, Russia). However, these effects did not extend to student competence beliefs in either Graham’s (Citation1984) or Rustemeyer’s (Citation1984) experiments. Moreover, these effects were only partially supported in Taxer and Frenzel’s experiment (Citation2020) where it has been shown that university students’ competence beliefs were negatively influenced by pity only when interpreted as the teacher attributing their failure to lack of ability. This inconsistent empirical pattern seems to reflect the ambiguous effects of emotions such as anger and pity implied by the different theoretical pathways of interpersonal functions of emotions. Overall, we conclude that teachers’ predominant view of anger as a “taboo” emotion (Burić & Frenzel, Citation2019; Liljestrom et al., Citation2007; McPherson et al., Citation2003) and insistence that teacher-student interactions should be invariably characterized by warmth, sympathy, and caring (Noddings, Citation2013) may be worth reconsidering because well-meant sympathetic messages may backfire, especially in interactions with potentially disadvantaged students such as members of minority racial groups.

Furthermore, while the expression of positive affect in the classroom, specifically in terms of radiating enthusiasm for a topic or joy of learning, clearly has positive effects for learners (see Keller et al., Citation2016, for a review), there are also scattered hints in the literature that experienced enjoyment and displayed enthusiasm have to be mutually balanced in order to be fully beneficial for students. For example, as mentioned above, Frenzel et al. (Citation2018) observed a significant negative path from teacher to student enjoyment, beyond the positive mediated link between teacher and student enjoyment of class via perceived teacher enthusiasm. The authors interpreted this in terms of some teachers in the sample overrating their enjoyment (i.e., these teachers reported high enjoyment, whereas their enthusiasm as perceived by their students was relatively low). This overrating of enjoyment was associated with unfavorable effects for students’ enjoyment over time. These effects highlight that the validity of self-reported teacher emotions can sometimes be compromised due to self-deception and that the authenticity of teacher-expressed positive affect in class may be essential to really have positive effects on students. Potentially, these findings could also be understood against the background of the too-much-of-a-good-thing effect (Grant & Schwartz, Citation2011). Accordingly, too much teacher enjoyment can come across as inauthentic, resulting in unfavorable effects (see also Keller et al., Citation2018, on evidence that students seem to sense when teacher enjoyment and enthusiasm is faked or inauthentic; see Taxer & Frenzel, Citation2018, on evidence that expressing inauthentic enthusiasm can come at a cost for teachers, too).

Evidence on links between teacher emotions and teaching behaviors

The intra- and interpersonal effects of emotions described above imply that teacher emotions have important effects on their teaching behaviors, specifically in terms of the quality of relationships they build with their students, and their instructional strategies. These teaching behaviors have been described as key dimensions of instructional quality according to contemporary models in educational science (e.g. Pianta & Hamre, Citation2009; Praetorius et al., Citation2018) and can thus be expected to be highly relevant for student outcomes.

Links with teacher–student relationships

There is consistent empirical support from cross-sectional studies using teachers as the single source of inquiry for the proposed importance of emotions in building and maintaining teacher-student relationships. Teacher enjoyment tends to be strongly positively associated and teacher anger and anxiety negatively associated with teacher–student relationship quality, as reported for German and Austrian secondary school teachers (Frenzel et al., Citation2020; Hagenauer et al., Citation2015). In Aldrup et al.’ longitudinal study (2018), German secondary school teachers’ emotional exhaustion was negatively related to perceptions of teacher-student relationship quality, while teacher enthusiasm showed positive links with teacher-reported teacher-student relationship quality.

These results are also reflected in studies using separate sources of inquiry, i.e., linking teacher-reported emotions and student-reported dimensions of teacher social support, which can be interpreted as a proxy of teacher-student relationship quality. In German secondary school mathematics class contexts, positive links for teacher enjoyment and teacher caring and support after failure were observed (Frenzel et al., Citation2016; Kunter et al., Citation2008), and teacher-reported anger was positively linked with student-rated teacher disrespect (Frenzel et al., Citation2016). Finally, Arens and Morin’s (Citation2016) study using the German PIRLS data provided evidence of negative links between elementary teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ perceptions of learning support provided by teachers.

Links with instructional strategies

Teacher positive emotions tend to be positively linked with student-focused approaches to teaching, such as focusing on students’ knowledge-construction process and supporting students’ conceptual change. Negative emotions tend to be positively related to teacher-focused approaches to teaching, such as focusing on the content to be taught and its structure, organization, and presentation. These relationships were found both for primary teachers from Hongkong (Chen, Citation2019b) and for Australian higher education teachers (Trigwell, Citation2012). In addition, Australian early primary-years teachers who reported higher enjoyment during teaching mathematics sustained their positive attitudes when students struggled and reported spending more time teaching (Russo et al., Citation2020). Greek elementary school teachers’ enjoyment was positively associated with self-reported amounts of time planning instruction and evaluating teaching goals and teaching strategies that support self-regulation, such as encouraging metacognition and reflecting (Chatzistamatiou et al., Citation2014).

The studies reported above used teachers as the single source of inquiry. However, their findings are also reflected in studies using students as the single source of inquiry and when researchers link teacher-reported emotions with teaching behaviors observed by students or external raters. Becker et al.’ (2014) lesson diary study involving Swiss secondary school students showed that students’ observations of their teachers’ enjoyment were positively related to ratings of clarity of instruction and provision of content relevance, while the opposite pattern of associations was found for students’ observations of their teachers’ anger. Furthermore, Frenzel et al. (Citation2016) showed that German secondary school mathematics teacher-reported enjoyment was positively related to student-reported clarity and variety of instruction and negatively related to student-reported fast-paced instruction. Conversely, teacher-reported anger was positively related to class-reported fast-paced instruction and negatively related to variety in instruction; teacher anxiety was negatively related to the acceptance of errors. Similarly, Kunter et al. (Citation2008) showed that German secondary school mathematics teachers’ experiences of enjoyment and enthusiasm during teaching were related to both self-reported and student-reported classroom monitoring and cognitive activation. Focusing specifically on an autonomy-oriented instructional style, Shen et al. (Citation2015) showed that American physics education teachers’ levels of emotional exhaustion were negatively linked with their high school students’ perceptions of provision of choice, which in turn also affected the development of students’ autonomous motivation in physical education across a semester. Finally, using mentor ratings for measuring Chinese preservice candidates’ teaching performance, Chen (Citation2019a) reported positive correlations for the pre-service teachers’ self-reported positive emotions (i.e., joy and love) and negative correlations for anger.

Overall, there is rather consistent evidence that teachers’ positive emotions during teaching tend to be positively linked with effective instructional strategies. In contrast, elevated levels of teachers’ negative emotions covary with more unfavorable instructional strategies. The reported effect sizes are small to medium in size and extend across learner age groups, school types, and cultural backgrounds. Notably, no study to date seems to have dug deeper into the underlying psychological mechanisms for these links, exploring, for example, if it is indeed some sort of broadened or narrowed attention or thought-action repertoire that underlies these effects. Neither has any study yet addressed potential curvilinear links between teacher emotions and teaching performance, as implied for example by the Yerkes-Dodson-Law (1908), theories of optimal arousal (Eysenck, Citation1967; Smith et al., Citation1983), or the too-much-of-a-good-thing effect (Grant & Schwartz, Citation2011). The overall consistent but often small linear correlations found in this area of research so far may well have masked such curvilinear effects, which seem to be worthwhile avenues for future research.

Challenges and future directions

There is obvious merit in seeing teachers as human beings who, quite as much as learners, relish classroom successes and suffer through failures, who love and care for some but not all of their students all of the time, and who constantly adapt their classroom behaviors, often fueled by their feelings. However, bringing teacher emotions into the picture of classroom functioning also entails various challenges and increases complexity. Below, we outline two key challenges we identified regarding teacher emotion impact research, and propose complementary approaches in terms of measurement, research practice, and an extended scope through attention to emotion regulation. We hope that bringing new perspectives alongside the already important work underway will bring gains to the field in terms of both theory and application.

Challenge 1: Excessive reliance on self-report

Like the majority of existing research in educational psychology, research on teacher emotions is characterized by an undue reliance on self-report data. This applies to the outcomes considered (see Ferguson, Citation2012; Kunter & Baumert, Citation2006, on the debate about the validity of student-reported instructional quality) but specifically also to teachers’ emotions. There are clear advantages involved in using self-report inquiry methods for emotion research, but also several problems. Among the advantages of self-report techniques for research is that emotions are, by definition, highly subjective phenomena: Nobody but ourselves can judge best how we feel. Or, as Keltner et al. put it, “A science that disavows the connection between emotion and subjective experience would, in effect, abandon the goal of explaining the phenomena that people actually deem to be emotional in nature” (Keltner et al., Citation2019, p. 2). Additionally, presupposing that emotions are multi-componential phenomena comprising subjective experiences, action tendencies, physiological responses, and expressions, only self-report measures allow researchers to tap all components and their co-occurrence effectively.

The problems involved in self-report assessments of emotions possibly include compromised validity due to participants’ self-deception, social desirability, or lack of meta-emotional awareness. Self-deception and social desirability provide a particular obstacle in understanding the role of stereotypically taboo emotions in the lives of teachers. In other words, while self-reporting how they feel, teachers may also implicitly report how they believe they should feel. As such, when judging their emotional experiences, teachers often seem to consider emotional display rules, such as the inappropriateness of expressing anger or fear in class (e.g. Chang, Citation2020), a phenomenon that seems important to consider in the context of this research.

Challenge 2: Small and complex samples

To fully grasp the complexity of teacher-student interactions in classrooms, researchers need to embrace hierarchical data structures in which multiple students are nested within each teacher. Additionally, the reality of many (specifically secondary) school environments implies that teachers teach several different groups of students, often implying cross-classified data structures. Hierarchical linear modeling has become largely a standard practice in studies linking teacher variables with student outcomes, and methods for including student-level variables to model contextual and classroom climate effects have been elaborated (Marsh et al., Citation2012). However, it is less known that ignoring a crossed factor in analyzing cross-classified data also leads to biased estimation in the standard errors of regression coefficients (Luo & Kwok, Citation2009). Research designs that include both teachers and their students require enormous data collection efforts because for every teacher in the sample, multiple students have to be included (ideally full classes). As a result, the typical studies in this context involve quite impressive sample sizes on the student level, yet often borderline-sized samples on the teacher level. It is important to realize that any “teacher effect” will necessarily be estimated only with the power implied by the teacher-level sample size. As such, the field may need to find innovative ways to mobilize a large number of teachers.

Future directions 1: Complementary measurement approaches

In response to the overly heavy reliance on self-report methods in the context of classroom emotion research, a resounding call has come forth to explore alternative measurement approaches as documented by several symposia on the topic at international educational conferences (e.g. Loderer & Pekrun, Citation2019; Mainhard, Citation2019; Postareff, Citation2019). Such alternative measurement approaches typically involve focusing on single components of emotions which are largely beyond subjective control, such as heart rate or facial expressions. A fascinating further advantage of these measurement approaches is that they allow tracking emotional indicators in situ, modeling their moment-to-moment changes and thus mirroring the fluctuating nature of emotions.

Measuring human heart rate is methodologically challenging and has long been limited to lab-bound inquiry methods. However, recent technological advances made it possible to apply physiological measures in the field, in comparably unobtrusive ways, using so-called ambulatory assessment tools. Donker et al. (Donker et al., Citation2018, Citation2020) presented results involving teachers’ self-reported emotional experiences and their associated heart rate profiles during teaching. Donker et al. (Citation2018) showed that there is considerable interindividual variability in teachers’ physiological responses during teaching, both in terms of mean levels and in terms of time-series parameters (trends, autocorrelations). However, they also stated that interpreting any correlative links with the self-reported emotions is complex because the physiological data are rather unspecific: Increased heart rates basically indicate heightened emotional arousal, without being able to ascertain if the response was of positive valence (e.g., enjoyment) or negative valence (e.g., anxiety). In a next step, the authors (Donker et al., Citation2020) additionally included moment-to-moment teacher interpersonal behavior. They reported that the more agentic teachers behaved in class, the more positive emotions they reported post-lesson, no matter if their agentic behavior went together with a high or low heart rate. In contrast, teacher communal behavior frequency was unrelated to their post-lesson self-reported emotions, but if communal behavior went together with increased heart rates, teachers were more likely to report negative emotions after the lesson. By implication, “forcing” communal behavior seems to come with emotional costs for those teachers. We conclude that incorporating physiological responses in the context of teacher emotion research can bring about intriguing new insights, but it is not as simple as the physiological response being a direct indicator of teachers’ emotional experiences in class.

Another promising way to assess discrete emotions through means other than self-report is through facial expression analysis. There is rather compelling, long-standing theoretical and empirical support for the fact that certain discrete emotional experiences are linked with specific patterns of facial muscle activation (Ekman et al., Citation2002). Facial action coding used to be extremely resource-intensive as it required intensively trained coders who would typically take substantial time to code corresponding videotaped material. However, recent technological advances have revolutionized this field. Computer-based software packages using machine-learning algorithms have been developed to quite reliably detect emotion-typical facial expressions in real time (e.g. Stöckli et al., Citation2018). Such facial emotion recognition tools are particularly suitable for assessing learners’ emotions in computer-based learning environments (D’Mello, Citation2013; D’Mello et al., Citation2017), but automated facial action coding has not yet been employed in research on teacher emotions. One exception is Frenzel et al.’s study (Citation2019), which presented a methodological design involving multiple action cameras in the classroom to capture both the students’ and the teacher’s faces during regular classroom instruction. Their initial findings from a university teaching context mirror Donker et al.’s (Citation2020) physiological data in that there was considerable interindividual variability in teachers’ facial emotional expression, not only in terms of mean levels but also time series parameters. Furthermore, students’ emotional expressions were considerably less intense compared to teachers’ expressions. We suppose that such student and teacher facial expression data promise new avenues for exploring effects of teacher emotional expressivity and the complex reciprocal effects between teachers’ and learners’ emotional experiences in class, for example by modeling moment-to-moment teacher-student emotional expression synchrony (see also Bevilacqua et al., Citation2019, for first evidence on teacher-student EEG signal sychnrony).

Future directions 2: Complementary research practices

As we look into the future of research on teacher emotions, we are hopeful that individual researchers will continue to make advances related to the breadth and depth of measurement approaches, model complexities, and theoretical frameworks considered. Additionally, the field would benefit from individual researchers establishing collaborations to tackle the nagging issue of small teacher-level sample sizes. Specifically, we raise the idea of a “Many Teachers” project that would parallel the collaborative approach taken, for example, by the “Many Labs” projects (Ebersole et al., Citation2016; Klein et al., Citation2014, 2018) that brought researchers from around the globe together in running replications of longstanding psychological principles. For these initiatives, multiple independent research laboratories from around the world sign up to conduct the same study and pool the data, thereby creating not only a large sample size but also a broader range of contextual, procedural, and population variables. Through a “Many Teachers” initiative, we would aim to connect teacher emotion researchers worldwide. In terms of conceptualizing initial studies, this project could begin from a replication perspective by testing the above-described correlative links between various self-report measures of teacher emotions and focal outcomes, including students’ own emotions, cognitions, scholastic performance, motivational behavior, and classroom discipline in a range of grade levels, content areas, and teaching contexts, across culturally different education systems. This process would allow important context effects and potential curvilinear effects to finally be substantiated. An immediate challenge of this endeavor involves the need for measures that demonstrate sufficient evidence of validity across contexts; corresponding self-report instrument translation and adaptation would require particular rigor. A focus on alternative measures such as heart rate or facial expression analysis could reduce the concerns about cultural norms in self-reporting emotions, yet here fidelity of implementation would need attention. Regardless of these challenges, a “Many Teachers” type of initiative would allow teachers to be the focus of recruitment, gaining a sufficiently large sample to explore their emotions in their own right, and with respect to the implications they have for their students.

Future directions 3: Considering emotion regulation

One promising step to move beyond descriptive research which merely links teacher emotions with outcomes seems to be to explore when and why teacher emotions are detrimental or functional for classrooms. To this end, digging deeper into the role of emotion regulation seems auspicious.

Emotion regulation pertains to the degree to which people generally engage in monitoring and managing their emotions, for example through suppression, attentional deployment, or cognitive reappraisal (see Burić et al., Citation2017; Taxer & Gross, Citation2018, for reviews and measurement of teacher emotion regulation). A special case of emotion regulation is emotional labor which pertains to the degree to which people show, fake, or hide certain emotions depending on their perceived appropriateness in a given situation (see Burić et al., Citation2017; Wang et al., Citation2019, for reviews and measurement of emotional labor in teachers). Emotional labor is highly prevalent among teachers, many of whom sense that implicit emotional display rules prescribe which feelings and emotional expressions are deemed as (in)appropriate in the classroom (Chang, Citation2020; Winograd, Citation2003). For example, teachers are expected to display positive emotions and suppress or hide negative ones, while also keeping the intensity of their emotions at generally moderate levels (Taxer & Frenzel, Citation2015). To date, teacher emotion research and teacher emotion regulation research have largely been addressed in isolation even though they are conceptually tightly linked. For example, there is first scant empirical evidence suggesting that teacher emotional labor, above and beyond teacher emotional experiences, could be relevant for teaching performance and student outcomes (Burić, Citation2019; Burić & Frenzel, Citation2020), but this area of research still seems largely underdeveloped.

We propose that emotion regulation can be considered both a mediator and a moderator of the links between teacher emotions and student outcomes. Its mediating effect implies that certain discrete emotions (e.g., anxiety) mobilize specific emotion regulation strategies (e.g., suppression) which, in turn, influence (e.g., impair) teaching performance. From this perspective, the self-monitoring and self-corrective actions involved in emotion regulation consume cognitive resources and lead to performance impairment (Gross, Citation2002). The moderating effects of emotion regulation imply that the size of teachers’ emotions impact on students depends on the degree to which teachers manage to regulate their emotional experience. For example, teachers have been found to use attentional deployment to divert attention from misbehaving to well-behaved students (Burić et al., Citation2017; Chang & Taxer, Citation2020). Consequently, if teachers successfully manage the anger that may be surging up inside them in the face of student misbehavior by use of attentional deployment, the negative effects of their anger on their instructional behavior will be mitigated, and they can successfully proceed with their lesson, despite short peak experiences of anger. From this perspective, the emotional experience per se has adverse effects, which can be mitigated if the emotion is successfully down-regulated.

We propose that attending to emotion regulation in the context of teacher emotion research bears multiple promises. It can advance our understanding of the effects of teacher emotions, which is intriguing and of basic scientific interest. Further, understanding when and how emotions can and should be regulated by teachers is an essential prerequisite for designing interventions targeting teacher emotion regulation for better classroom functioning.

Conclusion

We opened this article remembering “those” teachers—ones who, intentionally or not, passed their pleasant or unpleasant emotions on to us as students. In exploring the underlying psychological science that may explain those phenomena, we have articulated several ways in which teacher emotions may impact students through direct transmission effects and indirect effects via important teacher behaviors, including their instructional strategies and relationship building. However, throughout this article, we have also argued that teachers should not be seen as the origin of all corresponding student and classroom variables. We have thus highlighted the role of recursive relationships through which teacher emotions may be impacted by student outcomes. For example, it is possible that the cheerful teacher in the introduction reaped the benefits of an upward spiral as their students got really enthusiastic about the content and radiated their joy back at them. In contrast, perhaps the emotionally distant teacher was teaching a content area that she was never very passionate about and so her instructional quality and relationships with students suffered. Indeed, it is so hard to tease apart causes and effects with respect to teacher emotions and student outcomes that reciprocal links seem only logical.

Finally, although we have identified several plausible mechanisms, many important questions remain to be answered, chief among which is the role of emotion regulation. To advance insights into those complex questions, researchers will need to move beyond a reliance on correlative designs and self-report, build global partnerships between researchers and with diverse school boards to recruit and retain large samples of teachers (and their students), and embrace the potential of different theoretical frameworks to shed light on teacher emotions.

Notes

1 Of note, teacher enthusiasm has been viewed from different perspectives, with some researchers considering it as a behavioral variable describing a particularly energetic and motivating way of delivering instruction, while others consider it as an internal experience of enjoyment and passion about the topics taught, and/or the activity of teaching itself. The interested reader is referred to Keller et al. (Citation2016) for an integrated perspective across those views.

2 It is worth noting that reported effect sizes do vary by methodological approach, as could be expected: They are larger for single source studies and smaller for studies employing separate sources for teacher emotions and student outcomes. Clearly, though, the observed effects in single-source studies cannot be fully explained by methodological artifacts.

3 Martin (Citation2006) and Banerjee et al. (Citation2017) are two notable exceptions. Martin (Citation2006) reported small effects of gender on teacher-perceived student motivation/teacher enjoyment links, but no moderation by years of experience. Banerjee et al. (Citation2017) reported stronger links between teacher positive emotional experiences and young student mathematics performance trajectories in schools whose cultures were characterized by a strong teacher professional community and teacher collaboration.

References

- Aldrup, K., Klusmann, U., Lüdtke, O., Göllner, R., & Trautwein, U. (2018). Student misbehavior and teacher well-being: Testing the mediating role of the teacher-student relationship. Learning and Instruction, 58, 126–136. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.006

- Arens, A. K., & Morin, A. J. S. (2016). Relations between teachers’ emotional exhaustion and students’ educational outcomes. Journal of Educational Psychology, 108(6), 800–813. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000105

- Banerjee, N., Stearns, E., Moller, S., & Mickelson, R. A. (2017). Teacher job satisfaction and student achievement: The roles of teacher professional community and teacher collaboration in schools. American Journal of Education, 123(2), 203–241. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1086/689932

- Barrett, F. L., Lewis, M., & Haviland-Jones, J. M. (Eds.). (2016). Handbook of emotions (4th ed.). The Guilford Press.

- Beal, D. J., Weiss, H. M., Barros, E., & MacDermid, S. M. (2005). An episodic process model of affective influences on performance. The Journal of Applied Psychology, 90(6), 1054–1068. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1054

- Becker, E. S., Goetz, T., Morger, V., & Ranellucci, J. (2014). The importance of teachers‘emotions and instructional behavior for their students’ emotions – An experience sampling analysis. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 15–26. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2014.05.002

- Becker, E. S., Keller, M. M., Goetz, T., Frenzel, A. C., & Taxer, J. L. (2015). Antecedents of teachers' emotions in the classroom: An intraindividual approach. Frontiers in Psychology, 6, 635 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00635

- Bevilacqua, D., Davidesco, I., Wan, L., Chaloner, K., Rowland, J., Ding, M., Poeppel, D., & Dikker, S. (2019). Brain-to-brain synchrony and learning outcomes vary by student-teacher dynamics: Evidence from a real-world classroom electroencephalography study. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience, 31(3), 401–411. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1162/jocn_a_01274

- Burić, I. (2019). The role of emotional labor in explaining teachers’ enthusiasm and students’ outcomes: A multilevel mediational analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 70, 12–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2019.01.002

- Burić, I., & Frenzel, A. C. (2019). Teacher anger: New empirical insights using a multi-method approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102895. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102895

- Burić, I., & Frenzel, A. C. (2020). Teacher emotional labour, instructional strategies, and students’ academic engagement: A multilevel analysis. Teachers and Teaching, 2020, 1–18. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1740194

- Burić, I., Penezić, Z., & Sorić, I. (2017). Regulating emotions in the teacher’s workplace: Development and initial validation of the teacher emotion-regulation scale. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(3), 217–246. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/str0000035

- Burić, I., Slišković, A., & Macuka, I. (2018). A mixed-method approach to the assessment of teachers’ emotions: Development and validation of the Teacher Emotion Questionnaire. Educational Psychology, 38(3), 325–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2017.1382682

- Büssing, A. G., Dupont, J., & Menzel, S. (2020). Topic specificity and antecedents for preservice biology teachers’ anticipated enjoyment for teaching about socioscientific issues: Investigating universal values and psychological distance. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1536. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01536

- Butler, R. (1994). Teacher communications and student interpretations: Effects of teacher responses to failing students on attributional inferences in two age groups. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 64(2), 277–294. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1994.tb01102.x

- Carson, R. L., Weiss, H. M., & Templin, T. J. (2010). Ecological momentary assessment: A research method for studying the daily lives of teachers. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 33(2), 165–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2010.484548

- Cassady, J. C., & Finch, W. H. (2020). Revealing nuanced relationships among cognitive test anxiety, motivation, and self-regulation through curvilinear analyses. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1141 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01141

- Chang, M.-L. (2013). Toward a theoretical model to understand teacher emotions and teacher burnout in the context of student misbehavior: Appraisal, regulation and coping. Motivation and Emotion, 37(4), 799–817. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-012-9335-0

- Chang, M.-L. (2020). Emotion display rules, emotion regulation, and teacher burnout. Frontiers in Education, 5, 90. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2020.00090

- Chang, M.-L., & Davis, H. A. (2009). Understanding the role of teacher appraisals in shaping the dynamics of their relationships with students: Deconstructing teachers’ judgement of disruptive behavior/students. In P. A. Schutz & M. Zembylas (Eds.), Advantages in teacher emotion research: The impact on teachers lives (pp. 95–127). Springer.

- Chang, M.-L., & Taxer, J. (2020). Teacher emotion regulation strategies in response to classroom misbehavior. Teachers and Teaching, 63(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1740198

- Chatzistamatiou, M., Dermitzaki, I., & Bagiatis, V. (2014). Self-regulatory teaching in mathematics: Relations to teachers’ motivation, affect and professional commitment. European Journal of Psychology of Education, 29(2), 295–310. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-013-0199-9

- Chen, J. (2019a). Efficacious and positive teachers achieve more: Examining the relationship between teacher efficacy, emotions, and their practicum performance. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28(4), 327–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-018-0427-9

- Chen, J. (2019b). Exploring the impact of teacher emotions on their approaches to teaching: A structural equation modelling approach. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 89(1), 57–74. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12220

- Cheng, B. H., & McCarthy, J. M. (2018). Understanding the dark and bright sides of anxiety: A theory of workplace anxiety. Journal of Applied Psychology, 103(5), 1–24. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/apl0000266

- de Ruiter, J. A., Poorthuis, A. M. G., Aldrup, K., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2020). Teachers’ emotional experiences in response to daily events with individual students varying in perceived past disruptive behavior. Journal of School Psychology, 82, 85–102. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2020.08.005

- de Ruiter, J. A., Poorthuis, A. M. G., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2019). Relevant classroom events for teachers: A study of student characteristics, student behaviors, and associated teacher emotions. Teaching and Teacher Education, 86, 102899. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102899

- D’Mello, S. (2013). A selective meta-analysis on the relative incidence of discrete affective states during learning with technology. Journal of Educational Psychology, 105(4), 1082–1099. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0032674

- D’Mello, S., Dieterle, E., & Duckworth, A. (2017). Advanced, analytic, automated (AAA) measurement of engagement during learning. Educational Psychologist, 52(2), 104–123. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1281747

- Donker, M. H., van Gog, T., Goetz, T., Roos, A.-L., & Mainhard, T. (2020). Associations between teachers’ interpersonal behavior, physiological arousal, and lesson-focused emotions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 63, 101906. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2020.101906

- Donker, M. H., van Gog, T., & Mainhard, M. T. (2018). A quantitative exploration of two teachers with contrasting emotions: Intra-individual process analyses of physiology and interpersonal behavior. Frontline Learning Research, 6(3), 162–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.14786/flr.v6i3.372

- Ebersole, C. R., Atherton, O. E., Belanger, A. L., Skulborstad, H. M., Allen, J. M., Banks, J. B., Baranski, E., Bernstein, M. J., Bonfiglio, D. B. V., Boucher, L., Brown, E. R., Budiman, N. I., Cairo, A. H., Capaldi, C. A., Chartier, C. R., Chung, J. M., Cicero, D. C., Coleman, J. A., Conway, J. G., … Nosek, B. A. (2016). Many Labs 3: Evaluating participant pool quality across the academic semester via replication. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 67, 68–82. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2015.10.012

- Ekman, P., Friesen, W. V., & Hager, J. C. (2002). Facial action coding system [E-book]. Research Nexus.

- Ellsworth, P. C. (2013). Appraisal theory: Old and new questions. Emotion Review, 5(2), 125–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073912463617

- Eysenck, H. J. (1967). Intelligence assessment: A theoretical and experimental approach. The British Journal of Educational Psychology, 37(1), 81–98. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1967.tb01904.x

- Ferguson, R. F. (2012). Can student surveys measure Teaching quality? Phi Delta Kappan, 94(3), 24–28. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171209400306

- Fischer, A. H., & Manstead, A. S. R. (2008). Social functions of emotion. In M. Lewis, J. M. Haviland-Jones, & L. Feldman Barrett (Eds.), Handbook of emotions (3rd ed., pp. 456–468). The Guilford Press.

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2001). The role of positive emotions in positive psychology: The broaden-and-build theory of positive emotions. American Psychologist, 56(3), 218–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066X.56.3.218

- Fredrickson, B. L. (2013). Chapter one – Positive emotions broaden and build. In P. G. Devine & A. Plant (Eds.), Advances in experimental social psychology (Vol. 47, pp. 1–53). Academic Press. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-407236-7.00001-2

- Frenzel, A. C. (2014). Teacher emotions. In R. Pekrun & E. A. Linnenbrink-Garcia (Eds.), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 494–519). Taylor & Francis.

- Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., & Goetz, T. (2015). Teaching this class drives me nuts! – Examining the person and context specificity of teacher emotions. PLoS One, 10(6), 630. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0129630

- Frenzel, A. C., Becker-Kurz, B., Pekrun, R., Goetz, T., & Lüdtke, O. (2018). Emotion transmission in the classroom revisited: A reciprocal effects model of teacher and student enjoyment. Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(5), 628–639. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000228