Abstract

Despite growing recognition of diverse forms of parental involvement, scarce research exists on the critical influence of sociocultural contexts on parental involvement in their children’s education. Building on and modifying Hoover-Dempsey’s parental involvement model, this article proposes a new sociocultural model to explain Chinese immigrant parents’ motivations for school-based and home-based involvement. Within the discussion of the model, each component is detailed but the emphasis is directed to three general components: the Chinese cultural model of learning, parental role construction, and school-family relations, including teachers’ parental involvement practices that differ from the U.S. mainstream culture’s model. This review demonstrates that Chinese immigrant parents tend to be more involved in some types of school-based activities (e.g., attending parent-teacher conferences and school events) than others (e.g., volunteering in classrooms and attending PTO meetings/school council). Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement processes also interact with family socioeconomic status and immigrant contexts. The article concludes with implications for research and educational practice.

Tim immigrated with his parents to the U.S. from China when he was 9 years old. His family lived in a middle-class Massachusetts town where he attended 7th grade at the local public middle school. Tim was studious and did well. One day, he brought home his report card with all A’s except one A-. On each subject line was a space for parent comments. Tim’s mother, Mei, dutifully wrote for each subject “So far so good, but Tim should work harder on improving his geometry, on his English vocabulary, his reading comprehension.” Tim handed the card back to his teacher as required. The same day, his mother got a call from the principal: “What more do you want from your child?!” Shocked by the tone of the question, Tim’s mother tried to respond but couldn’t. When the mother shared the call with one of the authors, she sobbed, asking, “Do American schools think we are bad parents?” Mei felt discouraged from further communicating with the school.

Mei’s story of rebuke at the hands of her son’s principal may not be surprising to scholars who study parent involvement in Chinese immigrant families. Researchers are familiar with the negative stereotypes that abound regarding these parents’ educational socialization practices and how they choose to be involved in their children’s school lives (Chao, Citation1994; Cheah et al., Citation2013; Qin & Han, Citation2014; Sy, Citation2006). Frequently, researchers and schools interpret the relative lack of school-based involvement among Chinese immigrant families from a deficit-oriented perspective, highlighting qualities these parents lack (e.g., inadequate English language skills, little knowledge about the U.S. school system). Further, parents such as Mei are often negatively stereotyped for their home-based involvement, being characterized as “tiger mothers”: overly demanding of their children’s school achievement (Cheah et al., Citation2013; Qin & Han, Citation2014), controlling (Lin & Fu, Citation1990), authoritarian (Camras et al., Citation2008; Steinberg et al., Citation1992), and lacking warmth (Cheah et al., Citation2015). Unfortunately, Mei’s experience is but one example of how Chinese immigrant parents are marginalized and made to feel that their culturally situated approach to educational socialization is misguided.

One misinterpretation of Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement arises from the fact that little attention has been paid to the nuanced ways in which these parents are involved in their children’s education, especially at school. While much has been written about barriers to school-based involvement faced by Chinese immigrant parents (Constantino et al., Citation1995; Pearce, Citation2006; Pearce & Lin, Citation2007), focus on sociocultural contexts that reveal these parents’ intentions and the indigenous meanings behind their school-based involvement has been scant. We maintain that the issue of Chinese immigrant parents’ “under-involvement” in their children’s schools is understudied, under-conceptualized, and in need of both theoretical and empirical attention. Specifically, we problematize the American standard of school-based involvement, one that promotes engagement in school governance, volunteerism in classrooms, and participation in school meetings and events, as a Eurocentric, school-centric framework that, (a) does not work well for Chinese immigrant parents, and (b) limits our understanding of diverse ways immigrant parents relate to teachers and support schools and their children’s education.

Chinese are the largest ethnic group among Asians, the fastest growing and the largest racial group entering the U.S. since 2009 (Pew Research Center, Citation2021b). In 2019, Chinese comprised 24% of Asian Americans (4.9 million) (Pew Research Center, Citation2021b). Most Chinese American children grow up in an immigrant household. As the bulk of research on Chinese immigrant families has focused on middle-class families who are better positioned to support their children’s learning through wider resources (Chao, Citation1994; Cheah et al., Citation2015; Jung et al., Citation2012), our article also examines families of lower-socioeconomic status (SES). SES brings a complex picture to Chinese immigrant parental involvement. Despite increasing numbers of highly educated, self-selected immigrants in this group (M. Zhou & Lee, Citation2017), as a whole, their poverty rate is higher than that of the entire population, including all ethnic/racial groups (15% vs. 13%, Pew Research Center, Citation2021a). An examination of low-SES parents’ involvement would bring important insights into studies of parental involvement, considering the academic gap associated with SES within this group (J. Li et al., Citation2010; Qin & Han, Citation2014).

Insufficient research on school-based involvement by Chinese immigrant families, and more broadly Asian immigrants, can perpetuate the model minority myth: Asian Americans are doing well academically, with involved parents at home, and do not need support from school (Kao, Citation1995; S. J. Lee, Citation2009). The myth risks underestimating students’ needs and expectations and marginalizing the students and their parents in U.S. schools. It also limits opportunities for schools to build culturally responsive and sustainable relationships with Asian immigrant families, including Chinese immigrants, to better support their children (S. J. Lee, Citation2009; Qin & Han, Citation2014). An examination of sociocultural contexts provides a window to understand school-based involvement among Chinese immigrant families. Such an examination will lead to insights into the need to prepare future teachers to recognize, appreciate, and learn from the strengths inherent in culturally and linguistically diverse families regarding school-related involvement.

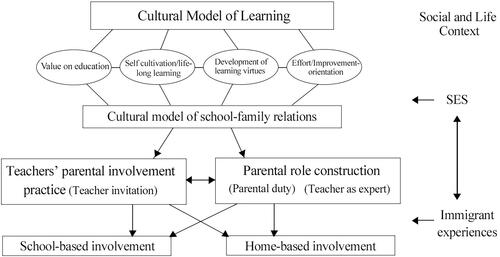

Below we present a new sociocultural model that guides Chinese immigrant parents’ motivation for involvement. After demonstrating Chinese immigrant parents’ school-based and home-based involvement patterns, we delineate the explanations, intentions, and meanings behind them. We pay special attention to cultural models (described in the next section) and social and life contexts (SES and immigrant experiences) shaping these parents’ school-based and home-based involvement.

A sociocultural model of parental involvement

We use the term “parental involvement” throughout this article to denote school- or learning-related support, engagement, or participation by parents or other significant family members (Hill et al., Citation2004; Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005; Pomerantz et al., Citation2007). In this article, we use a sociocultural approach to advance our arguments. In this framework, members in the same cultural community share their cultural model, a belief system that has been collectively constructed over their native culture's historical development (Chirkov, Citation2020; Harkness & Super, Citation2002; J. Li & Yamamoto, Citation2020). Such a cultural model influences what parents do, how they do it, and why they do what they do to raise their children and support their education. Parents are considered intentional actors who develop goals and strategies to help children attain skills and characteristics valued in society. This sociocultural approach is instrumental in understanding immigrant parents’ involvement in children’s education because their cultural model, which does not match their new context, is likely to be challenged and negotiated over time (Bornstein et al., Citation2020; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2008). Delving into the complex sociocultural contexts where their cultural model interacts with immigrant contexts helps us understand both strengths intrinsic to, and challenges faced by, Chinese immigrant parents in their efforts to support their children’s education in the U.S.

To understand Chinese immigrant parents’ school-based and home-based involvement, we first underscore the importance of the Chinese cultural model of learning, which is the largest and predominant value system regarding learning and education (see ). Cultural models of learning refer to collectively developed belief systems specific to learning that influence cultural members’ attitudes toward and processes of learning and education (J. Li, Citation2012; J. Li & Yamamoto, Citation2020). This cultural model reflects widely shared dominant beliefs and views, but does not represent diverse and varied views that exist within the culture. Although the Chinese cultural model of learning has other important manifestations (e.g., teacher-student relationships), we focus on four concepts that are central to the theme of parental involvement in this article (see ). The parental involvement model developed by Hoover-Dempsey et al. (Citation2005) presents family culture, which is the traditions and values brought by families, as a critical element influencing parents’ motivation for involvement. However, in our sociocultural approach, cultural models are pillars of parental involvement that shape parents’ beliefs and involvement practices. The cultural model of learning guides Chinese immigrant parents’ expectations of their children’s education, construction of their role as parents, perceptions of teachers and their roles, and a model of school-family relations, as we will elaborate in the later sections.

In this model, we highlight two key constructs shaping parents’ motivations for involvement identified by Hoover-Dempsey and Sandler (Citation1997) and Hoover-Dempsey et al. (Citation2005): parental role construction and teachers’ parental involvement practices—especially teacher invitation. Parental role construction, defined as “parents’ beliefs about what they are supposed to do in relation to their children’s education” (Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005, p. 107), plays a crucial role in Chinese immigrant parents’ decisions for involvement. According to the model by Hoover-Dempsey et al. (2005), parents with active role construction tend to believe that schools and parents are both responsible for children’s education and thus become involved in their children’s schooling. On the other hand, parents with passive role construction tend to rely on the school for their children’s education and become involved only when invited by schools (Walker et al., Citation2005). While this distinction is helpful to understand the two types of role construction, it does not consider cultural variation in the expectations and roles played by parents and teachers. As we will delineate later, Chinese immigrant parents’ role construction is closely intertwined with their beliefs, in which respect for teachers and their perceptions of the boundary between home and school figure prominently. Thus, Chinese immigrant parents’ active role construction regarding school-based involvement may be contingent on teachers’ parental involvement practices, especially teacher invitation; demonstrates connections between these parent and teacher practices. We will delineate the significant roles of teacher invitation in Chinese immigrant parents' school-based involvement.

A significant contribution of our model to parental involvement research is our proposal of a new construct, a cultural model of school-family relations: people’s culturally situated beliefs about and expectations of teacher-parent interactions and communications. A cultural model of school-family relations is usually constructed and shared based on arrangements and practices made by school institutions in that community. As presented in , it is also closely related to the cultural model of learning shared in the community since the expectations and norms of educational institutions usually align with those shared in the mainstream culture (Lareau & Calarco, Citation2012). For example, communications between parents and teachers in Chinese culture are often centered around improving children’s learning and academic progress by focusing on areas for improvement, as learning is traditionally regarded as a process of self-cultivation. This is a core of Confucian teaching which we will elaborate upon later in this article.

This concept is particularly useful to explain Chinese immigrant parents’ motivations and varied ways of school-based involvement. Although scholars have pointed out that the U.S. model is based on middle-class European-American norms (Comer, Citation2005; Epstein & Sanders, Citation2002; Lareau & Calarco, Citation2012), there has been little conceptualization and empirical research on diverse cultural models of school-family relations. Immigrant parents are likely to shape their expectations of school-family relations based on their own school experiences and arrangements in their countries of origin (García Coll & Marks, Citation2009; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2008). Because such expectations tend to be different from the U.S. model, it is crucial to examine the differences and how such differences impact immigrant parents’ involvement, especially at school.

We also address how social and life contexts, such as SES and immigrant experiences, interact or moderate the cultural model of learning, parent role construction, and school-family relations. While both low-SES and middle-SES Chinese immigrant parents may share the beliefs inherent in the Chinese cultural model of learning (Yamamoto et al., Citation2016), life contexts, resources associated with SES, and immigrant experiences are likely to moderate the pathways from the cultural model to parental involvement.

Chinese immigrant parents’ school-based and home-based involvement

The conventional definition of school-based parental involvement in the U.S. focuses on parents’ interactions with teachers and school personnel (Comer, Citation2005; Epstein & Sanders, Citation2002; Jackson, Citation2005). Teachers seek to develop strong connections and partnerships between home and school and expect parents’ cooperation and support in classrooms and the school as a way of community building and enhancing children’s education (Comer, Citation2005; Mapp, Citation2003; Smith & Sheridan, Citation2019). The model of U.S. school-family relations is school-centric and emphasizes a parent-to-school approach (Bempechat et al., Citationin press; Mapp, Citation2003; Warren et al., Citation2009). Ample evidence demonstrates that Chinese immigrant parents tend to provide multiple forms of educational support for their children (Chao, Citation1996; Huntsinger & Jose, Citation2009; Schneider & Lee, Citation1990). However, how Chinese immigrant parents support their children’s education may not always fit the widespread U.S. definition of parental involvement. Below, we delineate how Chinese immigrant parents tend to be involved at school and at home.

Evidence on school-based involvement

School-based involvement in the U.S. generally “represents practices on the part of parents that require their making actual contact with schools” (Pomerantz, Citation2007, p. 374). These practices include parent participation in events, attendance at parent-teacher meetings, taking initiative to communicate with teachers, volunteering at school, and engaging in parent-teacher organizations (PTOs) and school decision-making processes (Comer, Citation2005; Epstein & Sanders, Citation2002; Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005). Research has also captured processes of parental advocacy directed at teachers and schools, through which they advocate and intervene in their children’s educational processes (Hoover-Dempsey & Sandler, Citation1997; Lareau & Calarco, Citation2012).

Several analyses demonstrate that school-based involvement is less common among Chinese immigrant or Chinese American parents than European American parents (Chao, Citation2000; Huntsinger & Jose, Citation2009; Pearce, Citation2006; Pearce & Lin, Citation2007). However, in-depth, within-group research reveals that Chinese immigrant parents do engage in several domains of school-based involvement, suggesting the importance of examining more nuanced dimensions of their school-based involvement. For instance, Chinese immigrant parents, particularly middle-class parents, tend to participate in school-initiated activities and meetings, especially when invited by teachers (Constantino et al., Citation1995; Jiang et al., Citation2012; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Middle-class Chinese immigrant parents also willingly attend teacher-parent meetings and often use these opportunities to inquire about their children’s academic performance, address their concerns, and seek advice from teachers (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Moreover, these parents may attend open houses and school events, such as fairs, concerts, student performances, or exhibitions, especially those showcasing or celebrating students’ learning (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Several studies have identified variations in school-based involvement depending on the SES of Chinese immigrant parents (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Qin & Han, Citation2014; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). School participation tends to be more challenging for low-income parents who work long hours. However, in-depth qualitative studies reveal low-income parents’ willingness to attend a parent-teacher meeting with a Chinese-speaking teacher or an interpreter at the meetings (Constantino et al., Citation1995; Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Jiang et al., Citation2012). While initiating contacts with teachers may not be common, middle-class Chinese immigrant parents often read reports, newsletters, and written notices from schools (Dyson, Citation2001; Wang, Citation2008). Parents who feel comfortable speaking English may contact teachers and make a request when they see problems in their children’s schooling experiences (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). A qualitative study conducted by Wang (Citation2008) describes upper-middle-class parents who initiate contact with teachers to request help in improving their children’s English or solving peer-related issues at school. Parents may also feel more comfortable communicating with teachers using written formats rather than oral communication. It is common for middle-class Chinese immigrant parents to use a combination of oral and written formats, such as communicating in person, writing notes, or emails (Dyson, Citation2001; Wang, Citation2008).

On the other hand, volunteering at school, attending PTO meetings, joining parent councils, or becoming involved in school decision-making tends to be uncommon, regardless of the families’ SES (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Jiang et al., Citation2012; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Studies reveal that Chinese immigrant parents often perceive PTO/PTA meetings and events as irrelevant to children’s educational experiences, unlike parent-teacher meetings which focus on children’s learning and school experiences (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Pearce & Lin, Citation2007).

In sum, Chinese immigrant parents, especially middle-class parents, are not “uninvolved” in their children’s schools. An array of research addresses the nuanced dimensions of school-based involvement among these parents.

Evidence on home-based involvement

A wealth of research has demonstrated various ways in which Chinese immigrant parents support their children’s education beyond school. Regardless of SES, Chinese immigrant parents tend to convey higher standards for their children’s performance, such as higher grades and greater educational attainment relative to parents in other racial groups (Chao, Citation2000; Hao & Bonstead-Bruns, 1998; Ng et al., Citation2017; Pearce & Lin, Citation2007). At home, parents tend to provide direct and indirect support for their children’s education. For example, both low-SES and middle-class Chinese immigrant parents tend to teach letters, numbers, and simple arithmetic skills to prepare their young children for the start of formal schooling (Huntsinger et al., Citation2000; Jung et al., Citation2012; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016). Several comparative studies demonstrate that Chinese immigrant parents tend to structure their children’s academic time, assign academic work, and use formal teaching methods more than European American parents (Chao, Citation2000; Huntsinger et al., Citation2000; Huntsinger & Jose, Citation2009). These practices are found to help children become familiar with academic and school tasks, adapt to a formal learning environment, and increase their academic performance (Huntsinger et al., Citation2000; Sy, Citation2006).

During the elementary years, parents, especially middle-class parents, often check their children’s homework and provide extra academic work, such as workbooks, to enhance their children’s academic skills (Chen & Stevenson, Citation1995; Schneider & Lee, Citation1990; Wang, Citation2008). In general, parents aim to develop children’s good learning habits and skills, such as working independently and completing homework (Chen & Stevenson, Citation1995; Sy, Citation2006). As children progress through their grades, parental involvement often shifts to a managerial role, such as monitoring children’s time (e.g., limiting screen time) and structuring their learning to optimize their academic work (Chao, Citation2000; Louie, Citation2001; Pearce & Lin, Citation2007). Sending their children to after-school academic programs or arranging tutoring is also a common practice used by middle-class parents and tends to begin in elementary school (Peng & Wright, Citation1994; Schneider & Lee, Citation1990; M. Zhou & Kim, Citation2006).

Although direct academic involvement such as helping with homework or monitoring children’s academics is less common among low-SES parents (Louie, Citation2001; Qin & Han, Citation2014), studies have identified creative ways that these parents support their children’s education, especially by using social capital (J. Li et al., Citation2008; M. Zhou & Kim, Citation2006). For example, low-income parents may identify a more knowledgeable, skilled helper (e.g., siblings, cousins) who can provide academic service or guidance for their children in their ethnic networks (J. Li et al., Citation2008). Parents may also acknowledge high-achieving students in their ethnic community as role models to motivate their children to work hard. Further, low-income parents may actively seek education-related information (e.g., curricula and qualities of neighborhood public schools) and use resources available in their ethnic community, such as extracurricular academic classes, language schools, or church schools to assist children’s learning (Kao, Citation1995; Louie, Citation2001; M. Zhou & Kim, Citation2006).

Overall, these studies demonstrate varied ways in which Chinese immigrant parents support their children’s education beyond school and the significant role they play in children’s educational experiences and academic development (Chen & Stevenson, Citation1995; Huntsinger et al., Citation2000; Schneider & Lee, Citation1990; Sy, Citation2006).

A sociocultural model explaining Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement

The critical question that needs to be addressed is why Chinese immigrant parents tend to be more involved in their children’s education at home than at school. In this section, we describe a sociocultural model that shapes Chinese immigrant parents’ beliefs and motivations for school-based and home-based involvement as presented in . In so doing, we illuminate indigenous meanings embedded in Chinese immigrant parental involvement.

The Chinese cultural model of learning

In Chinese culture, a predominant view places a high value on learning and education (first oval in ). There is a widely shared belief that education is a critical means for success and upward mobility (Ho, Citation1986; Ng & Wei, Citation2020). In addition to economic attainment, educational achievement also leads to social respect in Chinese communities. Learning is regarded as a lifelong process of self-cultivation (second oval in ). This process, as taught by Confucius and subsequent Confucians, rests on the belief that all humans possess the capacity to become the most sincere, genuine, and humane persons. Although intellectual development plays an important role, one’s social and moral/virtuous improvement assumes greater importance (T. H. C. Lee, Citation1999; J. Li, Citation2012).

The Chinese model emphasizes the development of learning virtues (third oval in ), such as diligence, persistence, and humility, rather than exploring or discovering objective knowledge (Bempechat et al., Citation2018; J. Li, Citation2012). Chinese teachers and parents tend to share the belief that effort, rather than innate ability, is the key to students’ academic outcomes (Fong, Citation2004; Ho, Citation1986; Ng et al., Citation2007). Therefore, they tend to focus on cultivating children’s learning virtues, especially hard work in the learning process (J. Li et al., Citation2010; Ng & Wei, Citation2020). Parents and teachers often seek to foster a self-discipline and humble self-view whereby children recognize their limitations and desire to learn from teachers and parents (J. Li, Citation2012; Ng et al., Citation2007; Yamamoto et al., Citation2022).

Stressed in learning are self-improvement and task mastery by exerting effort (fourth oval in ) (Chao, Citation1994; Ng & Wei, Citation2020). In this learning process, adults tend to focus on areas for improvement and point out mistakes instead of praising their children (Ng et al., Citation2007; Yamamoto et al., Citation2022). While both praise and criticism can be provided in a process- or person-oriented manner, Chinese parents’ criticisms tend to focus on children’s learning attitudes and engagement rather than ability (Ng et al., Citation2007; Yamamoto et al., Citation2022). Rather than highlighting success and fostering self-esteem or pride, they tend to believe that guidance or press for improvement is critical for continuous striving to self-improve, even for high achievers (J. Li et al., Citation2014; Miller & Cho, Citation2018; Yamamoto et al., Citation2021). While these approaches may look “authoritarian,” such process-oriented feedback is coherent with the process of fostering a mastery-orientation and growth mindset (Dweck, Citation2006; Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017; Ng & Wei, Citation2020). Since they rarely attribute children’s high or low performance to their innate ability, parents help children focus on their effort and learning process.

Parental role construction

Considering the above cultural model, Chinese immigrant parents’ motivation for supporting their children’s learning and education is sensible. Against this backdrop, the notion of “parental role construction” helps us understand why Chinese immigrant parents tend to focus on multiple forms of involvement at home instead of at school. Before discussing the cultural model of school-family relations, we delineate Chinese immigrant parents’ role construction by focusing on two constructs presented in , parental duty and teacher as experts.

Parental duty and guidance

Similar to many cultures, the critical role of loving and caring parents in children’s positive development is valued and emphasized in Chinese culture. However, parental duty is a central and critical notion explaining Chinese parents’ role construction. Chinese culture often emphasizes parents as rightful authority figures by highlighting their responsibilities and duties for intellectual, social, and moral teaching (Chao, Citation1994; Ho, Citation1986; C. Li, Citation2013; Yamamoto et al., Citation2021). Chinese and Chinese immigrant parents often believe that adults’ teaching, guidance, and correction are necessary for young children to learn and grow as learners (Chao, Citation1994; Ng & Wei, Citation2020). They tend to view that children require close guidance and training from adults (Chao, Citation1994; Cheah et al., Citation2015; Yamamoto et al., Citation2022). Parents are believed to be especially indispensable in children’s learning and education.

In general, children’s academic achievement brings high honor to their families, extended kin, and community (Ho, Citation1986; J. Li, Citation2012; Ng & Wei, Citation2020). Therefore, guiding children’s learning and training them, especially in the domain of academic development, is considered a parental duty and responsibility (Chao, Citation1994; Ng & Wei, Citation2020; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016). These beliefs charge parents to be involved in their children’s education and to dedicate themselves to the process, sometimes by sacrificing their own needs (Ng & Wei, Citation2020). Importantly, studies demonstrate that Chinese parents’ intensive home-based involvement is an expression of care and support. In Chinese culture, parents often express their affection and warmth through instrumental care (e.g., cooking the child’s favorite food) and dedication to teaching/guidance (e.g., daily reminders of paying attention to and respecting teachers) rather than physical or verbal affection (Cheah et al., Citation2015; Ng & Wei, Citation2020; Yamamoto et al., Citation2021).

Research shows that Chinese American children tend to recognize their parents’ nurturance and sacrifices, and report respecting them and their efforts (Bempechat et al., Citation2018; Fuligni, Citation2007; J. Li et al., Citation2010; Yamamoto et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). Such perceptions are found to be associated with Chinese American children’s motivation and engagement in learning, especially among low-SES students (Bempechat et al., Citation2018; Fuligni, Citation2007; Yamamoto et al., Citation2022). One study demonstrates a higher level of congruence in Chinese immigrant parents’ and adolescents’ academic expectations, indicating children’s receptivity to parents’ expectations (Hao & Bonstead-Bruns, 1998).

Teachers as experts

Chinese immigrant parents tend to exhibit a keen sense of responsibility to assist and guide their children’s education, regardless of SES (J. Li et al., Citation2008; Louie, Citation2001; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016, Citation2021). Their beliefs support the notion of active role construction. However, a predominant Chinese view also emphasizes teachers as educational experts. Chinese and Chinese immigrant parents tend to respect teachers for their wisdom, experiences, and moral guidance and believe that teachers should direct instruction at school (Kim, Citation2019; J. Li, Citation2012). They tend to consider that supporting and following teachers’ and schools’ decisions is a way of building trustful relationships with teachers.

Chinese and Chinese immigrant parents also tend to believe that schools and families hold distinct roles with a clear boundary between the two (J. Li, Citation2012; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Given the belief that schools are primarily responsible for children’s education while children are at school, parents tend to leave school-related decisions to teachers and schools (G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Studies reveal the common view shared by Chinese immigrant families, especially low-SES families: it is the school’s responsibility to make decisions on school-related issues (J. Li et al., Citation2008; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Thus, it is a misnomer to characterize Chinese immigrant parents as passive in their role. By respecting the boundary between home and school, parents may actively choose not to interfere with school operations unless teachers invite them. Instead, parents usually respond to institutional needs cooperatively by supporting their children’s education at home (Kim, Citation2019; Pang, Citation2004; Schneider & Lee, Citation1990).

A cultural model of school-family relations

Although the Chinese cultural model of learning and parental role construction explain why Chinese immigrant parents tend to be more involved in their children’s education at home than at school, it does not fully explain why they tend to be more involved in some types of school-based activities (e.g., attending parent-teacher conferences and school events) than others (e.g., volunteering in classrooms or attending PTO meetings/school council). In this section, we describe the Chinese cultural model of school-family relations, which is closely connected with the cultural model of learning, to understand Chinese immigrant parents’ varied dimensions of school-based involvement.

The Chinese cultural model of school-family relations

Evidence suggests that Chinese parents’ conceptualization of positive school-family relations is different from the school-centric “partnership model” addressed in U.S. schools (Epstein & Sanders, Citation2002; Pomerantz et al., Citation2007; Sy, Citation2006). As mentioned earlier, the U.S. model is designed to bring parents into school by providing opportunities for parents to volunteer in classrooms, participate in school governance, or attend school events, such as picnics or question and answer periods with the principal (Comer, Citation2005; Epstein & Sanders, Citation2002). In contrast, based on theories and data examining home-school relations, the Chinese cultural model of school-family relations reverses the emphasis to reflect school-to-family relations. This model addresses three core components: (a) a teacher-to-home approach, (b) improvement-oriented communication, and (c) strengthening personal relationships through socioemotional bonding.

First, Chinese school-family relations heavily emphasize and employ a teacher-to-home approach and, in this context, represents school-to-home relations. In China and other East Asian countries and regions, such as Taiwan and Hong Kong, schools usually do not expect parents’ substantial involvement or active role at school. As in the U.S., teachers organize teacher-parent meetings, where families are invited to visit the school to discuss children’s school lives and academic progress (Fong, Citation2004; Ho & Staub, Citation2018; Pang, Citation2004). However, schools rarely invite parents to volunteer in classrooms or ask parents to engage in school governance (Ho & Staub, Citation2018; Pang, Citation2004). Instead, teachers often reach out to families by visiting homes (Kim, Citation2019; J.-Y. Li, 2021; Liang, Citation2021; Wu & Zeng, Citation2011). Understanding family environments by visiting their homes and communities is considered a critical responsibility of teachers and an essential component in supporting students’ education (Ho & Staub, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2019; Pang, Citation2004; Wu & Zeng, Citation2011). The national education policy in China codifies “teacher home visits'' as a systematic practice (Central Government of the People's Republic of China [CGPRC], Citation2020). Although there are variations depending on provinces and regions, a recent survey demonstrates that home visits continue to be standard practice in elementary and middle schools in China (Liang, Citation2021). The aims of home visits are to learn about the student’s life beyond school, ranging from the home environment to the student’s daily routines, parent-child relationships, parental expectations, student’s aspirations, friendships, and emotional life (Liang, Citation2021; Pang, Citation2004). Teachers also often use these opportunities to inform parents about school expectations, student’s school lives, and academic progress (Kim, Citation2019; J.-Y. Li, Citation2021). Reflected in this practice are extended family-school interactions in non-school settings, in students’ homes and communities. Moreover, teachers, not families, are expected to actively reach out to families.

Secondly, the Chinese cultural model focuses on improvement-oriented communication. In regular newsletters and notes delivered or exchanged with families, schools often aim to keep families informed about school expectations, such as what parents should do, daily routines at school, homework, school events, and exam dates to bridge learning environments at home and school (Ho & Staub, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2019; Pang, Citation2004). In parent-teacher communications, both parents and teachers tend to focus on areas where the child can improve regardless of children’s achievement (Dyson, Citation2001; Kim, Citation2019; Wang, Citation2008). Teachers and parents usually exchange detailed information and assessments of the child’s strengths and weaknesses and these could involve criticism of children’s behaviors and attitudes (Fong, Citation2004; Kim, Citation2019). Teachers often focus on providing their observations of the student, including school life, peer relations, learning attitudes, and academic performance, and provide suggestions for improvement (Ho & Staub, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2019; Liang, Citation2021). Parents perceive these meetings as opportunities to bring their concerns about their child and request teachers’ advice. Teachers may also directly request that parents come to school when their children have issues or problems (Fong, Citation2004; Liang, Citation2021; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Fundamentally, teacher-parent communication is usually oriented toward improvement of children’s attitudes and behaviors through exertion of effort, especially in the domain of academics. As the Chinese cultural model of learning emphasizes the development of learning virtues, such as diligence and mastery-orientation, both teachers and parents tend to consider these improvement-oriented communications positive, necessary, and reflective of care (Dyson, Citation2001; Kim, Citation2019; J.-Y. Li, Citation2021).

Thirdly, Chinese relations aim to strengthen socioemotional bonding through personal relationships between teachers and families. This socioemotional bonding is believed to be effective in building the trust that lies at the heart of the school-family relationship. Teachers usually organize the first home visit at the beginning of the academic year to connect and develop rapport with the families (J.-Y. Li, Citation2021; Liang, Citation2021). The home visit is believed to be a symbolic practice demonstrating teacher care to build respectful relationships with families in educating their children (J.-Y. Li, Citation2021; Wu & Zeng, Citation2011). Ideally, teachers allocate much time to listening to parents’ concerns, responding to their questions, and providing suggestions tailored to individual families and students during their home visits and parent-teacher meetings (J.-Y. Li, Citation2021; Liang, Citation2021). Pervading these processes is a thoughtful and deliberate effort to make school feel like a family: a supportive place that helps parents facilitate their children’s well-being and academic development (J.-Y. Li, Citation2021; Kim, Citation2019). Such relationships are often believed to build foundations of frequent and deeper parent-teacher communication (Liang, Citation2021; Wu & Zeng, Citation2011). Teachers and parents may also regularly exchange their reports about their children, especially about their academic progress, by using notes and technology, such as social media, texting, phone, and other tools (Ho & Staub, Citation2018; Kim, Citation2019; Liang, Citation2021).

Dimensions of school-based involvement

Clearly, then, the parent-to-school approach in the U.S. does not match the model Chinese immigrant parents are used to and presents an adjustment challenge. Further, the U.S. system emphasizes a professional work alliance between teachers and parents whereby socioemotional bonds may be less central (Bempechat et al., Citationin press; Gonzales & Gabel, Citation2017). For Chinese immigrant parents, who often conceptualize school-family relations as a process of building personal relationships and emotional connections with teachers, volunteering in classrooms may seem impersonal, task-oriented, and irrelevant to children’s well-being. Indeed, an interview-based study by Ji and Koblinsky (Citation2009) reveals a Chinese immigrant mother’s disappointment in not having had any personal conversations with the teacher when she volunteered in her child’s classroom.

As Chinese immigrant parents, especially middle-class parents, often try to read newsletters and notes from schools, they are likely to be motivated to learn about school expectations and routines to support their children’s learning at home (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). They also tend to perceive attendance at school events, especially those related to academics (e.g., science fairs) or showcasing students’ learning or performance, as an opportunity to learn about children’s school learning (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2008). However, they may not always be motivated to attend events because of limited opportunities to develop personal connections with teachers or other families (Wang, Citation2008).

Considering the Chinese model of school-family relations, Chinese immigrant parents' higher frequency of attendance at teacher-parent meetings as compared to nonacademic events is likely to reflect their desire to build personal relationships and exchange improvement-oriented communications with teachers. Studies show that many Chinese immigrant parents find attendance at parent-teacher meetings in U.S. schools as important (Constantino et al., Citation1995; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). They often perceive parent-teacher meetings as opportunities to hear evaluations of their children’s academic progress and performance, as well as specific guidance and advice from teachers (Dyson, Citation2001; Wang, Citation2008). Interview-based research reveals that Chinese immigrant parents generally find teacher-parent meetings useful because they can “listen to” teachers to understand school curricula and “hear” about their children’s educational development (Jiang et al., Citation2012; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). However, research demonstrates mixed assessment of parent-teacher meetings by Chinese immigrant parents. While some find these meetings helpful, others feel that the meetings usually do not provide enough information about instructions to support their children’s learning or comments about their children’s school behaviors and academic progress (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2008). Parents are also often disappointed that the meetings are short and do not provide enough time to feel connected with the teachers (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Several studies find that the parent council or PTO, especially its function, may not be clear to many Chinese immigrant parents (G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Because the national government administers the educational system in China, parents may not perceive that they have opportunities to customize or influence school curricula or instructions (Fong, Citation2004; J. Li, Citation2012). Further, Chinese immigrant parents who attend PTO meetings often feel that those events or meetings are not beneficial or relevant to children’s schooling or well-being, as they tend to focus on reporting administrative issues, fundraising, or budgets (G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Social and life contexts

Social and life contexts powerfully impact parents’ motivation and decisions of school-based and home-based involvement. In this section, we describe how socioeconomic status and immigrant experiences interact or moderate the Chinese cultural model of learning, parental role construction, and Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement, as presented on the right side of .

Socioeconomic status

Increasing research indicates that the Chinese cultural model of learning may function as a protective factor for low-SES families. Research consistently finds that low-SES Chinese immigrant parents generally hold high aspirations and expectations of their children’s education (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; J. Li et al., Citation2008; Louie, Citation2001; Ng et al., Citation2017). Cultural beliefs emphasizing the value of education may elevate low-income parents’ expectations despite their limited resources and financial hardship (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016). Studies also reveal that low-SES Chinese immigrant parents with economic and life challenges try to emphasize cultivating learning virtues, such as the importance of hard work to achieve better lives through academic success (Bempechat et al., Citation2018; Fuligni, Citation2007; J. Li et al., Citation2008).

The Chinese cultural model that emphasizes the critical importance of parental role and authority may help low-SES Chinese immigrant parents maintain active role construction in their children’s educational processes. In one study, relative to middle-SES Chinese immigrant parents, low-income Chinese immigrant parents demonstrate a higher sense of responsibility in guiding, disciplining, and teaching their preschool children (Yamamoto et al., Citation2016). The cultural notion of training through parental devotion and sacrifice may guide low-income parents in believing that they play a critical role in their children’s learning. Further, in this study, low-income parents report more family cohesion with less conflict than do middle-SES parents. Low-income parents tend to reside in ethnic enclaves such as Chinatowns, where cultural beliefs and practices tend to be shared. These residential arrangements may help low-income families maintain traditional cultural values that facilitate their support for children’s education while receiving support from co-ethnic networks (Louie, Citation2001; M. Zhou & Kim, Citation2006).

While emphasizing their parental role, low-SES parents tend to believe that school plays a more significant role in their children’s academic achievement than middle-class parents (Louie, Citation2001; Qin & Han, Citation2014; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). In one study, Chinese immigrant parents, regardless of SES, value teacher quality, especially qualified and responsible teachers, as the most critical component of high-quality preschools more than do middle-SES European-American parents (Yamamoto & Li, Citation2012). However, within the Chinese immigrant group, low-income parents mention children’s academic outcomes as an essential component of high-quality preschool more than do middle-SES parents. This finding demonstrates low-income Chinese immigrant parents’ desire to receive support from teachers and schools in children’s academic development.

Studies also suggest a significant moderating impact of economic conditions on Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement, especially school-based involvement. For example, low-SES Chinese immigrant families often have persistent financial concerns that increase stress (Louie, Citation2001; Qin & Han, Citation2014). Due to demanding work schedules and long work hours, low-SES parents tend to find it difficult to attend school events or parent-teacher meetings (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Jiang et al., Citation2012). They often perceive school-based involvement as demanding and not worthwhile, reflecting that their time and effort may not result in visible benefits to their children’s learning outcomes (Constantino et al., Citation1995; J. Li et al., Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Overall, studies suggest that while the Chinese model of learning may help low-SES parents maintain active parental role construction and high educational expectations, SES contexts speak to the important role of structural and school support in their involvement.

Immigrant experiences

As we noted previously, immigrant experiences are an important layer of context in understanding Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement. While Chinese immigrant parents maintain their cultural model originating from their native culture, they tend to experience cultural discordance and modify their beliefs in response to new environments (Bornstein et al., Citation2020; García Coll & Marks, Citation2009; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2008). For example, immigrant contexts may generate Chinese immigrant parents’ optimistic as well as pessimistic views regarding their children’s future success, resulting in high expectations and involvement in their children’s education, especially at home (Kao & Tienda, Citation1995; Fernández-Reino, Citation2016). Coming to a new land, immigrant parents, including Chinese immigrant parents, are generally found to hold a more optimistic view of U.S. public schools, seeing them as egalitarian and of high quality, relative to U.S.-born parents (Kao & Tienda, Citation1995; Wang, Citation2008). As Chinese immigrant parents often leave their country seeking a better life, they tend to believe in children’s upward mobility, primarily through educational attainment, regardless of parents’ SES (Kao & Tienda, Citation1995; J. Li et al., Citation2008). At the same time, immigrant parents tend to recognize disadvantages and discrimination associated with minority status in the U.S. Such recognition is likely to increase these parents’ emphasis on education as a means to compensate for obstacles and anticipated discrimination (Fernández-Reino, Citation2016; Sue & Okazaki, Citation1990). Research has revealed that Chinese American adolescents and their parents often emphasize educational attainment because of concerns about career prospects associated with their minority status (Chen & Stevenson, Citation1995; Schneider & Lee, Citation1990).

Several studies suggest that Chinese immigrant parents’ high expectations of their children’s achievement and intensive home-based involvement are adaptation strategies utilizing their cultural model as a resource (Xie & Goyette, Citation2003). That is, Chinese immigrant parents may choose to highlight their cultural beliefs and practices, such as the high value placed on education and emphasis on effort, to overcome perceived disadvantages. For example, research on minority parents in the U.S., including Chinese immigrant parents, demonstrates a significant positive association between parents’ concerns over discrimination and their expectations for their children’s grades (Ng et al., Citation2017). This research also reveals that in Hong Kong, immigrant parents perceive education as a means for upward mobility more than Hong Kong-born parents. Such perceptions are associated with parents’ higher expectations of their children’s grades.

Beyond cultural models, like immigrant families from other ethnic groups in the U.S., language barriers are one of the significant elements impacting Chinese immigrant families’ school-based involvement (García Coll & Marks, 2012; Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2008; Turney & Kao, Citation2009). Because English is usually not their first language, Chinese immigrant parents often face challenges in communicating with teachers (Ji & Koblinsky, Citation2009; Jiang et al., Citation2012; Qin & Han, Citation2014). Studies show that English proficiency and unfamiliarity with the school system significantly impact Chinese immigrant parents’ decisions regarding school-based involvement, including attendance at parent-teacher meetings (J. Li et al., Citation2008; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Although discrimination issues have not received much attention in research on Chinese immigrants’ parental involvement, research demonstrates that perceptions of discrimination and cultural alienation inhibit these parents’ involvement at school (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Chinese immigrant parents tend to recognize their cultural and physical differences, although there are large variations depending on degrees of acculturation and community (Qin & Han, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2008). A study by Qin and Han (Citation2014) demonstrates that working-class Chinese immigrant parents tend to view themselves as “outsiders” in U.S. schools. Perceptions and experiences of becoming racial, cultural, and linguistic minorities in the U.S. are likely to enhance Chinese immigrant parental involvement at home rather than at school.

Teacher invitation: Building personal relations

Considering that the Chinese model of school-family relations highly values personal relationships between teachers and parents, encouragement and personal invitations from teachers often play a critical role in Chinese immigrant parents’ motivations to participate in school-based activities (Jiang et al., Citation2012; Qin & Han, Citation2014; Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Interview-based studies demonstrate that Chinese immigrant parents tend to find school-based involvement beneficial, especially after attending parent-teacher meetings or volunteering in classrooms. These opportunities are likely to allow parents to understand school expectations and receive information to better support their children (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). However, it has also been reported that some parents would go to school only when teachers invite them (G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Research further suggests that teacher invitation could bring opportunities for the school and teachers to build closer relationships with families (Jiang et al., Citation2012; Qin & Han, Citation2014; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). One study reported a case of a mother who occasionally volunteered in her daughter’s classroom because she was invited by the teacher and encouraged to participate (Wang, Citation2008). In addition to having opportunities to see her child in her classroom and observe how children are taught in a U.S. classroom, this mother started to feel more comfortable communicating with teachers. Other studies reveal Chinese immigrant parents’ views that attending school events and volunteering in classrooms help them learn about “American school lives,” “teaching approaches,” and “school curricula,” although there are variations (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). These experiences could especially help to increase Chinese immigrant parents’ familiarity with the U.S. school system and sense of efficacy in supporting their children’s education (Wang, Citation2008; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018). Chinese immigrant parents often hope to receive more detailed information about curricula and instructions and comments about their children’s academic progress through parent-teacher meetings, but report that this rarely happens (Wang, Citation2008). Nevertheless, studies indicate that parents’ school-based involvement is likely to increase opportunities for Chinese immigrant families and teachers to understand each other’s expectations, regardless of families’ SES (Constantino et al., Citation1995; G. Zhou & Zhong, Citation2018).

Conclusion and implications

Growing research has demonstrated various ways that families support their children’s education and suggested ways to build effective family-school partnerships with families from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds (García Coll & Marks, 2012; Gonzales & Gabel, Citation2017; Jackson, Citation2005; Mapp, Citation2003; Souto-Manning & Swick, Citation2006). Research has increasingly described “funds of knowledge,” an array of cultural and intellectual resources, available in immigrant homes (Moll et al., Citation1992). Scholars have documented that the school-centric U.S. model does not always recognize or appreciate the ways immigrant and minority families support their children’s education outside of school. However, research delving into sociocultural contexts, including cultural models of learning and school-family relations, is still scarce.

As noted earlier, despite abundant research on Chinese immigrant parents’ home-based involvement, little attention has been paid to their school-based involvement. Our limited knowledge likely leads teachers and administrators to underestimate the cultural resources these families use to support their children’s education, as well as the meanings behind their educational socialization practices. As described in this article, Chinese immigrant parents tend to be involved in their children’s education at home while adapting to their new U.S. environments. The Chinese cultural model of learning emphasizing the development of learning virtues, self-cultivation, and lifelong learning, explains improvement-oriented ways through which these parents try to enhance their children's learning. Indeed, improvement-oriented parental involvement reflects parental care, love, and desire to help children become mastery-oriented and diligent learners. A greater understanding of the Chinese cultural model of learning that stresses developing children’s learning virtues could yield more nuanced indigenous meanings behind Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement.

Chinese immigrant parents’ role construction presents an interesting case in research on parental involvement. While Chinese immigrant parents tend to demonstrate active role construction, they may consider some types of school-based involvement and practices commonly found among middle-class U.S. parents, such as communicating with and negotiating with schools to advocate for their children, a negation of cultural values (Chao, Citation1994; J. Li, Citation2012; Louie, Citation2001; Yamamoto et al., Citation2016). Our review points to the critical role that teacher and school invitation may play in encouraging Chinese immigrant families’ school-based involvement. Teacher and school invitations usually signal that parents are “welcome, valuable, and expected by the school and its members” (Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005, p. 110). Given their native model of school-family relations, Chinese immigrant families are likely to perceive teacher invitation as reflecting teachers’ care and respect, a crucial first step to building personal relationships with them.

A critical contribution of this review is our detailed discussion of the cultural model of school-family relations that is inherently related to the cultural model of learning and schooling arrangements in Chinese immigrant parents’ countries of origin. Previous research has demonstrated that racial and ethnic minority parents’ involvement often does not match the expectations held by U.S. schools (Comer, Citation2005; Jackson, Citation2005; Mapp, Citation2003). Nevertheless, there has been little conceptualization of the cultural expectations of school-family relations among diverse ethnic groups. We were able to present the Chinese cultural model of school-family relations in which a school-to-home approach, improvement-oriented communication, and fostering personal relationships are granted. Differences between the Chinese and U.S. models may explain lesser degrees and varied dimensions of school-based involvement among Chinese immigrant families. Research shows that teachers tend to perceive parents’ absence from school involvement as reflecting a lack of caring (Comer, Citation2005; Souto-Manning & Swick, Citation2006). Our review compels us to argue that instead, it may be parents who perceive a lack of caring on the part of teachers. Based on cultural differences, this perception could be one of the reasons Chinese immigrant parents are less motivated to be involved in their children’s schools. As such, different cultural models of school-family relations are likely to be unrecognized by both parents and teachers. We call for more research on diverse models of school-family relations.

Our review also suggests the importance of examining variations within immigrant and ethnic minority groups. In studies examining the role of SES in parental involvement, disadvantages such as limited resources, social capital, and skills that hinder lower-SES parents’ involvement have been highlighted (Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005; Qin & Han, Citation2014). Given that family SES has been found to play a weaker role in the achievement of Asian American students (Liu & Xie, Citation2016), investigating low-SES families could yield further valuable insight into parental involvement. A principal finding identified in Chinese immigrant parents is that their cultural model of learning may serve a protective role in low-SES parents’ maintenance of cultural beliefs and practices that enhance their children’s learning. Yet, life contexts and resources associated with SES present challenges for low-SES parents to translate their role construction into their practices, especially when no support networks are available (J. Li et al., Citation2008; Louie, Citation2001). In general, research paying attention to SES differences in this group is still scarce. Available findings call for attention to the importance of examining more unique forms of parental involvement among low-SES immigrant families. The intersection between culture and SES appears to be a significant area for researchers to explore.

Previous studies on immigrant families’ school-based involvement have highlighted barriers and challenges facing these families, such as language issues (Constantino et al., Citation1995; Turney & Kao, Citation2009). We suggest that Chinese immigrant parents’ high expectations and emphasis on home-based involvement could be an adaptive response to their immigrant challenges. Little is known about how Chinese immigrant parents maintain, negotiate, or renew their cultural models and role constructions (e.g., their perceptions of parents’ and teachers’ roles) as they become acculturated. Longitudinal research that enables us to understand how family-school interactions influence immigrant parents’ cultural beliefs and practices in support of their children’s education would be particularly compelling.

In this review, we did not examine how different types of Chinese immigrant parents’ school-based involvement influence children’s school experiences or academic outcomes. We call for research that examines the associations between dimensions of school-based involvement and various student outcomes. Research on students’ socioemotional development related to their schooling experiences is important, given the high rate of socioemotional issues and parent-child conflicts reported by adolescents of Chinese immigrant families (Qin et al., Citation2008, Qin & Han, Citation2014). Evidence demonstrates that high home-school dissonance is associated with adolescents’ negative emotional states (Arunkumar et al., Citation1999; Qin et al., Citation2008). As positive school-family relations are found to bridge cultural gaps between home and school and increase effective socioemotional support provided by families at home (Comer, Citation2005; Hoover-Dempsey et al., Citation2005), these lines of research could be particularly beneficial for Chinese immigrant families.

Educational implications

Our review suggests several educational implications, including a need for schools to pay attention to multiple ways immigrant parents support their children’s education. When working with families from diverse cultural and linguistic backgrounds, we encourage teachers and schools to recognize their cultural assumptions, assess possible misconceptions, and aim to understand these families’ values and traditions. Schools should also view immigrant families’ unique forms of parental involvement as assets to students’ learning and reach out to engage them in meaningful ways (Moll et al., Citation1992). It is essential for teachers and schools to understand and respect families’ cultures, including beliefs and practices, yet pay attention to individual variations, especially within the same cultural group. As Chinese immigrant families are diverse in SES, their immigration experiences and histories are bound to vary.

Recognizing cultural models of school-family relations could help schools find creative ways to facilitate communication with immigrant families. As language is one of the significant challenges, teachers can use various strategies to promote their communication with immigrant parents. For example, they can help find an interpreter or a bilingual person in the community to facilitate their communication. Exchanging communication through written formats, such as emails or notes, may make Chinese middle-class immigrant parents feel more comfortable, as they tend to have more academic English proficiency with written than oral English. Using technology as a tool to facilitate family-school communication may also match with the modes of communication used in their countries of origin (J.-Y. Li, Citation2021; Pang, Citation2004). Schools can also identify, use, and inform parents of various translating software to facilitate communication.

Our review suggests that schools’ and teachers’ invitations are critical for Chinese immigrant parents’ involvement at school. Schools can create opportunities to help these parents understand the school system and expectations by providing information sessions or space for them to ask questions, creating translated newsletters/brochures or websites, including common Q&A. More importantly, creating a welcoming and culturally responsive environment that shows appreciation for cultural and language diversity allows parents to feel comfortable participating in school events and activities. Such processes would also allow school personnel and teachers to promote personal relationships and build mutual trust with parents and families.

Finally, the implications of our review compel us to examine how teacher education programs prepare preservice teachers to work with culturally and linguistically diverse parents. Importantly, much attention in preservice teacher education is given to culturally relevant pedagogy; yet little attention is paid to cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic diversity as it relates to building meaningful connections with diverse parents (Souto-Manning & Swick, Citation2006). National and state accreditation standards for licensure may require that teachers evince respect for families’ “beliefs, norms, and expectations” and work collaboratively with families to meet and set educational goals (Council of Chief State School Officers, Citation2013). Regrettably, however, teacher educators have noted a persistent lack of intentional preparation in knowledge, skills, and respectful understanding of parent involvement in culturally and linguistically diverse families (Oakes et al., Citation2017).

From a training perspective, teacher preparation primarily focuses on lesson planning. Few, if any, assignments are focused on how preservice teachers can engage with families in culturally respectful and meaningful ways, and preservice teachers are afforded few opportunities to interact with parents (Smith & Sheridan, Citation2019). In their placement sites, preservice teachers rarely, if ever, are offered the opportunity to plan activities that would invite parents to the school. At best, preservice teachers may be asked to sit in on parent-teacher conferences. Home visits are common in preschool and kindergarten, but beyond these years, preservice teachers have little opportunity to visit families in their homes or communities, a common occurrence in East Asia. Consequently, novice teachers do not feel prepared to engage with families and risk adopting deficit-oriented stereotypes as a way to understand the perceived lack of school-based involvement (Smith & Sheridan, Citation2019). In short, teacher preparation programs must make room for instruction and training that seeks to enhance preservice teachers’ understanding of culturally-based parental engagement strategies, embrace these with humility as a starting point, and move toward mutual respect.

Indeed, imagine if Tim’s teacher was open to cultural differences or had been familiar with the Chinese cultural model of learning and school-family relations, the outcome would be different. Tim’s teacher would have embraced Mei’s comments on the report card as an expression of care for her son and respect for his teacher. Such a culturally informed approach, oriented toward the goal of creating sincere communication, could serve as a model for demonstrating mutual respect and understanding. Tim’s parents and the caring teacher would move forward, committed together to his academic improvement, regardless of his performance.

Supplemental Material

Download JPEG Image (173.6 KB)Acknowledgments

We express our great appreciation to the editors of this special issue and reviewers. Their insightful comments and constructive suggestions helped us revise our model and significantly improve the article.

References

- Arunkumar, R., Midgley, C., & Urdan, T. (1999). Perceiving high or low home–school dissonance: Longitudinal effects on adolescent emotional and academic well-being. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 9(4), 441–466. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327795jra0904_4

- Bempechat, J., Li, J., & Ronfard, S. (2018). Relations among cultural learning beliefs, self-regulated learning, and academic achievement for low-income Chinese American adolescents. Child Development, 89(3), 851–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12702

- Bempechat, J., Shernoff, D. J., Puttre, H., & Wolff, S. (in press). Parental influences on achievement motivation and student engagement. In A. L. Reschly, & S. L. Christenson (Eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (2nd ed.). Springer Science.

- Bornstein, M. H., Bohr, Y., & Hamel, K. (2020). Immigration, acculturation and parenting. In R. E. Tremblay, M. Boivin, & RDeV Peters (Eds.), Encyclopedia on early childhood development (pp. 1–10). Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development and Strategic Knowledge Cluster on Early Child Development.

- Camras, L., Kolmodin, K., & Chen, Y. (2008). Mothers' self-reported emotional expression in Mainland Chinese, Chinese American and European American families. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 32(5), 459–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025408093665

- Central Government of the People's Republic of China. (2020, October 13). Shenhua xinshidai jiaoyupingjia gaige zongtifangan [The overall plan for deepening the reform of education evaluation in the new era]. http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/2020-10/13/content_5551032.htm

- Chao, R. K. (1994). Beyond parental control and authoritarian parenting style: Understanding Chinese parenting through the cultural notion of training. Child Development, 65(4), 1111–1119. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.1994.tb00806.x

- Chao, R. K. (1996). Chinese and European American mothers’ beliefs about the role of parenting in children’s school success. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 27(4), 403–423. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022196274002

- Chao, R. K. (2000). The parenting of immigrant Chinese and European American mothers: Relations between parenting styles, socialization goals, and parental practices. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 21(2), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00037-4

- Cheah, C. S. L., Leung, C. Y. Y., & Zhou, N. (2013). Understanding “tiger parenting” through the perceptions of Chinese immigrant mothers: Can Chinese and U.S. parenting coexist? Asian American Journal of Psychology, 4(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031217

- Cheah, C. S. L., Li, J., Zhou, N., Yamamoto, Y., & Leung, C. (2015). Understanding Chinese immigrant and European American mothers’ expressions of warmth. Developmental Psychology, 51(12), 1802–1811. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0039855

- Chen, C., & Stevenson, H. W. (1995). Motivation and mathematics achievement: A comparative study of Asian-American, Caucasian-American, and East Asian high school students. Child Development, 66(4), 1215–1234. https://doi.org/10.2307/1131808

- Chirkov, V. (2020). An introduction to the theory of sociocultural models. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 23(2), 143–162. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajsp.12381

- Comer, J. (2005). The rewards of parent participation. Education Leadership, 62(6), 38–42.

- Constantino, R., Cui, L., & Faltis, C. (1995). Chinese parental involvement: Reaching new levels. Equity & Excellence in Education, 28(2), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/1066568950280207

- Council of Chief State School Officers. (2013). Interstate teacher assessment and support consortium in TASC model core teaching standards and learning progressions for teachers 1.0: A resource for ongoing teacher development. https://ccsso.org/resource-library/intasc-model-core-teaching-standards-and-learning-progressions-teachers-10

- Dweck, C. S. (2006). Mindset: The new psychology of success. Random House.

- Dyson, L. (2001). Home-school communication and expectations of recent Chinese immigrants. Canadian Journal of Education / Revue Canadienne de L'éducation, 26(4), 455–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/1602177

- Epstein, J. L., & Sanders, M. G. (2002). Family, school, and community partnerships. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting volume 5: Practical issues in parenting (pp. 407–437). Erlbaum Associates.

- Fernández-Reino, M. (2016). Immigrant optimism or anticipated discrimination? Explaining the first educational transition of ethnic minorities in England. Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 46, 141–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rssm.2016.08.007

- Fong, V. L. (2004). Only hope: Coming of age under China's one-child policy. Stanford University Press.

- Fuligni, A. J. (2007). Family obligation, college enrollment, and emerging adulthood in Asian and Latin American families. Child Development Perspectives, 1(2), 96–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2007.00022.x

- García Coll, C., & Marks, A. K. (2009). Immigrant stories: Ethnicity and academics in middle childhood. Oxford University Press.

- Gonzales, S. M., & Gabel, S. L. (2017). Exploring involvement expectations for culturally and linguistically diverse parents: What we need to know in teacher education. International Journal of Multicultural Education, 19(2), 61–81. https://doi.org/10.18251/ijme.v19i2.1376

- Haimovitz, K., & Dweck, C. S. (2017). The origins of children's growth and fixed mindsets: New research and a new proposal. Child Development, 88(6), 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12955

- Hao, L., & Bonstead-Bruns, M. (1998). Parent-child differences in educational expectations and the academic achievement of immigrant and native students. Sociology of Education, 71(3), 175–198. https://doi.org/10.2307/2673201

- Harkness, S., & Super, C. M. (2002). Culture and parenting. In M. H. Bornstein (Ed.), Handbook of parenting volume 2: Biology and ecology of parenting (pp. 253–280). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Hill, N. E., Castellino, D. R., Lansford, J. E., Nowlin, P., Dodge, K. A., Bates, J. E., & Pettit, G. S. (2004). Parental academic involvement as related to school behavior, achievement, and aspirations: Demographic variation across adolescence. Child Development, 75(5), 1491–1509. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00753.x

- Ho, D. Y. F. (1986). Chinese patterns of socialization: A critical review. In M. H. Bond (Ed.), The psychology of the Chinese people (pp. 1–37). Oxford University Press.

- Ho, E. S. C., & Staub, K. V. (2018). Home and school relationships in Switzerland and Hong Kong. In S. B. Sheldon & T. A. Turner-Vorbeck (Eds.), The Wiley handbook of family, school, and community relationships in education (pp. 289–314). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119083054.ch14

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., & Sandler, H. M. (1997). Why do parents become involved in their children’s education? Review of Educational Research, 67(1), 3–42. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543067001003

- Hoover-Dempsey, K. V., Walker, J. M. T., Sandler, H. M., Whetsel, D., Green, C. L., Wilkins, A. S., & Closson, K. (2005). Why do parents become involved? Research findings and implications. The Elementary School Journal, 106(2), 105–130. https://doi.org/10.1086/499194

- Huntsinger, C. S., & Jose, P. E. (2009). Parental involvement in children’s schooling: Different meanings in different cultures. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 24(4), 398–410. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2009.07.006

- Huntsinger, C. S., Jose, P. E., Larson, S. L., Balsink Krieg, D., & Shaligram, C. (2000). Mathematics, vocabulary, and reading development in Chinese American and European American children over the primary school years. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(4), 745–760. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.4.745

- Jackson, K. (2005). Rethinking parent involvement: African American mothers construct their roles in the mathematics education of their children. School Community Journal, 15(1), 51–73.

- Ji, C. S., & Koblinsky, S. A. (2009). Parent involvement in children’s education: An exploratory study of urban, Chinese immigrant families. Urban Education, 44(6), 687–709. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042085908322706

- Jiang, F., Zhou, G., Zhang, Z., Beckford, C., & Zhong, L. (2012). Chinese immigrant parents’ communication with school teachers. Canadian and International Education, 41(1), 59–80.

- Jung, S., Fuller, B., & Galindo, C. (2012). Family functioning and early learning practices in immigrant homes. Child Development, 83(5), 1510–1526. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2012.01788.x

- Kao, G. (1995). Asian Americans as model minorities? A look at their academic performance. American Journal of Education, 103(2), 121–159. https://doi.org/10.1086/444094

- Kao, G., & Tienda, M. (1995). Optimism and achievement: The educational performance of immigrant youth. Social Science Quarterly, 76(1), 1–19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44072586