Abstract

The study of classroom processes that shape students’ motivational beliefs, although fruitful, has suffered from a lack of conceptual clarity in terminology, definitions, distinctions, and roles of these important processes. Synthesizing extant research and major theoretical perspectives on achievement motivation, I propose Motivational Climate Theory as a guide for future research efforts toward more accurate, systematic understanding of classroom motivational processes. As an initial organizing framework, three broad categories of classroom motivational processes are defined: motivational supports, consisting of speech, actions, and structures in a setting that are controllable by the people in that setting; motivational climate, defined as students’ shared perceptions of the motivational qualities of their classroom; and motivational microclimates, or students’ individual perceptions that differ from shared perceptions. Motivational support and climate’s key characteristics and mechanisms are described, followed by recommendations, future directions, and implications for research, practice, and policy.

Recent advances in achievement motivation theory and educational interventions have underscored the importance of school contexts in shaping students’ motivation and success (Kaplan et al., Citation2020; Walton & Yeager, Citation2020; Wigfield & Koenka, Citation2020). Motivation researchers have long studied features of schools and classrooms that can influence students’ motivation (Ames, Citation1992b; Lazowski & Hulleman, Citation2016; Reeve & Cheon, Citation2021). Motivation theorists also largely agree on the general principles involved in supporting students (e.g., Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., Citation2016; Pintrich, Citation2003; Turner et al., Citation2014), such as attributing success to effort and strategy use, providing opportunities for students to feel autonomous, and helping students recognize the value of course material.

However, the study of classroom motivational processes suffers from a lack of conceptual clarity (Bringmann et al., Citation2022) about the definitions, roles, and nature of classroom influences on motivation. Achievement motivation theories provide strong guidance on student-level processes, including clear definitions that guide methodological decisions and synthesis of conclusions about individual beliefs (e.g., achievement goals, task values) across multiple studies. How group-level and contextual processes should be conceptualized and studied is less clear. Conceptual clarity about how contexts support motivation, including clear definitions, distinctions, and explanations of mechanisms in alignment with extant research findings, is a necessary step toward increasing the ecological validity and social impact of motivation research. Such clarity will inform best practices for research, will enhance understanding of situated motivational processes, and will improve practical recommendations for how to support students’ motivational needs.

Accordingly, in this article, I synthesize diverse perspectives on classroom motivational processes to propose Motivational Climate Theory, a theoretically cross-cutting conceptual framework. Social cognitive and situated perspectives (Nolen, Citation2020; Schunk & DiBenedetto, Citation2020), with their premises, that personal, social, and behavioral factors are not only interrelated but inextricable, form a broad initial framework for my investigation. I draw heavily on achievement goal theory (Ames, Citation1992b; Urdan & Kaplan, Citation2020) and self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020) due to their strong base of evidence, overlap with recommendations from other theoretical frameworks (e.g., attribution theory, Graham, Citation2020; interest theory, Renninger & Hidi, Citation2020), and rich theorizing about the roles of educational contexts. I also highlight contributions from situated expectancy-value theorists (SEVT; Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020) and psychological intervention researchers, who are increasingly acknowledging the importance of contextual processes for students’ optimal psychological functioning (Walton & Yeager, Citation2020), along with classroom quality frameworks that motivation researchers have leveraged in their work. Lastly, I incorporate sociocultural and antiracist perspectives (APA, Citation2021; Buchanan et al., Citation2021) to address the need for motivation research to re-center “the social purpose of schooling” (López, Citation2022, p. 114), in particular the need to understand and reduce inequities in students’ access to motivating instruction (Cardichon et al., Citation2020; Eccles et al., Citation2006; McKown & Weinstein, Citation2008). By acknowledging the inherently cultural nature of motivational classroom experiences (Kumar et al., Citation2018), an improved framework for considering motivational classroom processes can more effectively address racism, discrimination, and opportunity gaps in education.

Motivational climate theory: Key propositions

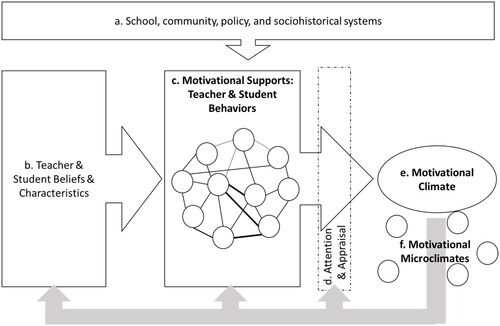

First, I propose that motivational classroom processes can be organized into three broad categories: motivational support, motivational climate, and motivational microclimates (defined in ). In subsequent sections of this article, I provide rationales for these categories and their definitions. I argue that motivational climate is not equivalent to the observable motivational supports in a given situation, but consists of the meanings and qualities that students attach to those motivational supports—the “feel” of the classroom. Some of these meanings and qualities are shared, and these comprise the motivational climate, whereas other meanings and qualities are unique to individuals or subgroups, and these are termed motivational microclimates.

Table 1. Defining motivational support, climate, and microclimate.

Next, I propose a few tenets regarding the nature and roles of support and climate processes, represented in a simplified form in ; detailed rationales and origins of these propositions are provided in subsequent sections. Specifically, supports () are assumed to give rise to the motivational climate (; see also Bardach, Oczlon, et al., Citation2020) and microclimates () via students’ attention to and appraisals of those supports (). As indicated by the network-style representation of motivational supports in based on Hilpert and Marchand’s (Citation2018) representation of complex systems, support, and climate are perhaps best described as a dynamic system wherein the “feel” of the class emerges based on numerous factors, including relational qualities among students and teachers, and in which the factors that are most important and salient vary across individuals and groups, over time, and across situations. In this case, system components are the diverse student and teacher behaviors that are relevant for shaping students’ motivation. Teachers’ and students’ characteristics (; e.g., motivational beliefs, knowledge, and cultural backgrounds) are assumed to be the most important factors contributing to their behaviors (i.e., motivational supports). Motivational supports and the resulting motivational climate and microclimates are assumed to be multidimensional, malleable, and to have differing meanings and benefits to students within the same context. Motivational climate and microclimates also play unique roles in shaping students’ outcomes.

Terminology and definitions: Making sense of classroom motivational processes

Researchers use a wide variety of terms to refer to classroom and teacher processes that shape students’ motivation. Theoretical traditions vary widely in the specificity or grain size of focal processes, and in the extent to which contextual processes are clearly defined, operationalized, and tested (see ). Diverse terminology is not necessarily problematic, but a lack of consensus as to the definitions and conceptual connections among the many terms hampers scientific progress (Bringmann et al., Citation2022). In this vacuum of theoretical guidance, motivation researchers often adopt terms on their own judgment or borrow from other frameworks (e.g. classroom quality, Pianta & Hamre, Citation2009) to inform definitions, measurement, and analysis of classroom processes, often without describing these origins or providing rationale for their decisions. It appears to be relatively rare that researchers explicitly define the terms they adopt or distinguish their chosen processes from similar, related processes (Johnson et al., Citation2022). For these reasons, it is difficult to form a unified picture of definitions, let alone current knowledge about how contexts shape motivation. In this section, I highlight prominent terms that are particularly relevant for making sense of motivational classroom processes, along with terms that serve as illustrative examples of the proposed organizational framework (). also indicates which terms, according to the definitions provided in , can be considered support or climate (including microclimate) processes.

Table 2. Definitions and classifications of classroom motivational process terms.

Commonly used terms and perspectives

Achievement goal structures

Achievement goal researchers have focused on classroom qualities that support students’ adoption of mastery- or performance-related achievement goal orientations. These classroom qualities, or students’ perceptions of these qualities, are referred to somewhat interchangeably as achievement goal structures or achievement goal climate (Bardach, Oczlon, et al., Citation2020). Goal structures often include teachers’ actions related to task and evaluation characteristics, autonomy support, grouping practices, and the teacher’s use of time (TARGET; Epstein, Citation1988; Meece et al., Citation2006), or students’ perceptions of such processes, which in turn are assumed to promote higher amounts and quality of student motivation.

Need support

Need support or autonomy support (e.g., autonomy-supportive teaching/practices, Fong & Zientek, Citation2019; Reeve & Cheon, Citation2021) are the terms used commonly in self-determination theory literature on classroom motivational influences (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Need support refers to classroom or school features that support students’ basic needs: autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). When considering how to organize various terms and constructs, one particularly helpful aspect of self-determination theory is the distinction between need support and need satisfaction (Jang et al., Citation2016). This distinction draws a clear division between the actions or structures teachers are likely to be able to control (i.e., need support) and the student perceptions and reactions to those actions and structures (i.e., need satisfaction).

Psychological affordances

Intervention researchers have recently adopted the term “psychological affordances” to refer to “features of contexts that make an adaptive perspective possible” (Walton & Yeager, Citation2020, p. 219; see also Murphy et al., Citation2020; Reis, Citation2008). For example, a teacher’s endorsement of a growth mindset is a psychological affordance because presumably, a teacher with a growth mindset will behave in ways that nurture and reward students’ growth mindsets. Psychological affordance researchers examine how these affordances explain the success or failure of student-focused interventions, rather than on how such affordances act as interventions themselves. However, achievement goal climate or autonomy support could be two types of psychological affordances in that they signal to students that endorsement and enactment of certain motivational beliefs are valued and rewarded in class.

Socializers’ behaviors

Situated expectancy-value theory (SEVT; Eccles & Wigfield, Citation2020) and research tend to focus most on individual student processes, however, SEVT refers to socializers’ beliefs and behaviors as important upstream contextual processes that shape students’ motivational beliefs. Socializers’ beliefs and behaviors are a broad category encompassing several processes of various grain sizes (see ). In empirical SEVT research, perhaps the most prominent studies on external influences are those about interventions delivered directly to students by researchers (relevance interventions; Rosenzweig et al., Citation2022). However, SEVT researchers have also used observational methods to examine such processes as teachers’ enthusiasm (Parrisius et al. Citation2020) and relevance statements (Schmidt et al., Citation2019) as specific examples of how socializers’ behaviors can influence students’ motivation.

Classroom quality

Some of the terms used in motivation research (e.g., teaching quality, Göllner et al., Citation2018; teacher emotional support, Schenke et al., Citation2018), arise from classroom quality perspectives. Perhaps due to its well-developed concepts and measures, classroom quality literature is often leveraged to inform motivation researchers’ measurement and analytic practices (e.g., Göllner et al., Citation2018; Klusmann et al., Citation2022; Lüdtke et al., Citation2009; Schenke et al., Citation2018), and to a lesser extent theoretical development (e.g., Eccles & Roeser, Citation2009). highlights definitions of teaching/classroom quality, its dimensions, and sub-facets from prominent frameworks (Pianta & Hamre, Citation2009; Praetorius et al., Citation2018; Pressley et al., Citation2003), showing conceptual overlap with motivational processes. For example, Praetorius et al. (Citation2018) described teaching quality as consisting of three dimensions: classroom management, student support (i.e., need support), and cognitive activation. Motivation researchers Eccles and Roeser (Citation2009) organized teacher and classroom-level processes into three very similar dimensions. Similarly, Pianta and Hamre (Citation2009), in their widely used framework, proposed dimensions of emotional support, classroom organization, and instructional support. Each of Pianta and Hamre’s dimensions have sub-facets, such as emotional support’s subfacets of teacher sensitivity and regard for student perspectives (i.e., autonomy support).

Terms and definitions used in classroom quality frameworks (see ) certainly show overlap with processes that are of interest to motivation researchers; however, classroom quality processes are organized such that motivation researchers may struggle to adapt them into coherent theoretical and methodological approaches for their studies. For example, it may not be reasonable or feasible to separate motivational factors from other aspects of classroom quality as organized in classroom quality perspectives. In some cases, elements of most or all quality dimensions might reasonably be relevant for various student motivational beliefs. Instead, to situate motivational processes within the broader educational literature, it may be helpful to consider motivational climate and support as one framework or perspective for considering classroom quality.

Terminology takeaways

In addition to the terms mentioned thus far, researchers studying motivation in schools use a variety of other terms including motivational climate (Ames, Citation1992b), motivational support (Turner & Patrick, Citation2004), social climate (Lüdtke et al., Citation2009), teacher support (Filak & Sheldon, Citation2008), and teachers’ motivational approach (Collie et al., Citation2019), among many others. Examining constructs frequently used in research on classroom motivational processes reveals a jumble of terms that conflate observable classroom features with student perceptions of such features and the resulting “feel” of the classroom. In many cases, it is unclear whether terms refer to observable and manipulable features of the environment, teachers’ perceptions of their own behaviors, students’ perceptions of that environment, or some combination of these. Definitions are often vague and do not outline the nature or boundary conditions of the terms. As a first step in addressing these issues, I propose distinctions among motivational climate, microclimate, and support processes.

Grouping motivational processes: Motivational climate, microclimate, and support

Educational researchers using a social-cognitive lens have used the term “climate” to refer to “school, classroom, or teacher (group-level, L2) characteristics [that] contribute to the prediction of students’ (individual-level, L1) outcomes” (Marsh et al., Citation2012, p. 107; see also Bardach, Yanagida, et al., Citation2020). The term “motivational climate” appears often within achievement goal theory research (Ames, Citation1992b; Bardach, Yanagida, et al., Citation2020; Deemer & Smith, Citation2018; Patrick et al., Citation2011; Wolters, Citation2004), wherein climate is used synonymously with achievement goal structure (Bardach, Oczlon, et al., Citation2020). Self-determination theory researchers have also used the terms climate, classroom climate, and motivational climate (e.g., Ryan et al., Citation2019; Williams & Deci, Citation1996) to mean support for the basic needs. Thus, motivational climate has been used to refer broadly to characteristics of the educational setting that contribute to shaping motivational beliefs among students in that environment.

More specifically, achievement goal theorists have referred to motivational climate as a “psychological environment” (Maehr & Midgley, Citation1991; Roeser et al., Citation1996), reflecting the importance of the meanings students make of their environment as drivers of shifts or stability in individual goal orientations (Ames, Citation1992b). This view is corroborated by organizational behavior literature (James et al., Citation2008), wherein psychological climate is defined as “individuals’ cognitive representations of proximal environments, expressed in terms that represent the personal meaning of environments to individuals” (James & Sells, Citation1981, p. 275; emphasis added), or more simply, an individual’s descriptions of their environment (Parker et al., Citation2003). Similarly, Byrd (Citation2017) defined another type of climate—school racial climate—as “perceptions of interracial interactions and the socialization around race and culture in a school” (p. 700). Taking a self-determination theory perspective, Ryan and Grolnick (Citation1986) emphasized the importance of the “functional significance” (p. 550) students attribute to their experiences. In other words, it is the meanings of classroom experiences and characteristics that comprise the motivational climate and its potential to impact motivation (Bardach, Oczlon, et al., Citation2020; Lüdtke et al., Citation2007).

Many studies have accordingly reflected this emphasis on students’ individual, often idiosyncratic perceptions of their environments (e.g., Becker et al., Citation2014; Lazarides et al., Citation2018), contributing important insights into the relations between student-perceived climate and student outcomes. Overall, it seems clear that compared to observer- or teacher-reported classroom processes, student perceptions are the stronger, more consistent, and proximal predictors of student motivation (Wagner et al., Citation2016). Although these stronger relations may in part reflect common method bias and/or parallel wording of items often used in both climate and student motivation measures, empirical evidence also provides some support for the subjective and individualized nature of motivational climate, as students report varying experiences within the same classroom setting (Schenke et al., Citation2018; Schweig, Citation2014; Schweig & Martínez, Citation2021; Wagner et al., Citation2016). Students’ varying reports are partially due to actual differences in classroom experiences, and partially due to differences in perceptions of the same teaching (Ames, Citation1992b; Seidel, Citation2007). Indeed, in some cases, students’ reports of their classroom appear to reflect more about the individual student than they do about the context (Lam et al., Citation2015; Miller & Murdock, Citation2007; Robinson et al., Citation2022), as variance explained by between-classroom differences varies widely (1–32% in the cited studies), but is typically much smaller than the amount of variance explained by between-student differences (Morin et al., Citation2014).

Clearly, then, attention and perception play key roles in linking environments to psychological processes, as students presumably cannot be motivated by classroom features they do not notice, remember, or interpret as being motivationally supportive. For example, a student focused on their teacher’s math problem explanation may not notice or remember the teacher’s enthusiastic attitude, whereas another student may focus more on the enthusiasm, perhaps because the student is confident they can solve the problem. Two students may also similarly focus their attention but may interpret the same teacher behavior differently due to differing past experiences, levels of readiness, or other personal and cultural characteristics (Kruglanski et al., Citation2014; Robinson & Lee, Citation2022; Schweig, Citation2014). If a teacher demonstrates the importance of course content using real-world examples that only reflect the values and norms of their own culture, students who share that cultural background will likely interpret those examples as being more relevant to their lives, and thus more motivational, compared to students who do not share the teacher’s cultural background (Kumar, Citation2006; Kumar & Maehr, Citation2007; Matthews, Citation2018).

Microclimates or shared climates: Why not both?

Considering the importance of attention, perception, and meaning-making, is there no such thing as an “objective,” observable, or shared motivational climate? As an important counterpoint to the idea that climate is totally unique to each individual, Bardach, Yanagida, et al. (Citation2020) asserted that students in the same classroom have a “shared mental image” (p. 349; see also Lüdtke et al., Citation2007) of the classroom. In other words, there must be some shared classroom experiences that students agree are motivating, and other classroom experiences that students can together describe as demotivating. This motivational climate is something like a classroom culture, wherein students can point to shared values, experiences, narratives, structures, and behaviors that characterize and differentiate one classroom from another (Kumar et al., Citation2018; Roeser et al., Citation1996). For example, a group of students may agree that their math teacher is generally more enthusiastic than their science teacher, whereas their science teacher provides more helpful feedback compared to their math teacher. Indeed, identifying shared classroom experiences that promote adaptive student beliefs is an important aim of achievement goal research (Ames, Citation1992b; Maehr & Midgley, Citation1991, Citation1996; Urdan & Kaplan, Citation2020) and other theoretical traditions (Reeve & Cheon, Citation2021; Rosenzweig et al., Citation2022).

Thus, although students differ in their experiences and perceptions within a given classroom, the conceptual and logical arguments presented above along with studies treating students as interchangeable raters of classroom experiences indicate motivation researchers also assume there are shared experiences and some degree of group-level agreement about the motivational qualities of these experiences (e.g., Murayama & Elliot, Citation2009; Wolters, Citation2004). Empirical research provides evidence that motivational classroom features can be reliably assessed using aggregated student perceptions (Marsh et al., Citation2012; Morin et al., Citation2014; Wentzel et al., Citation2017). Even with heterogeneity in student reports of the same classroom, whatever consensus can be achieved at the group level can be used to distinguish one classroom’s or teacher’s motivational qualities from another’s. Furthermore, high within-class consensus about classroom experiences may actually be an indicator of effective classroom environments, with high heterogeneity in student perceptions hinting at maladaptive processes (Bardach et al., Citation2019, Citation2021). Perhaps a “strong” classroom climate, consisting of clear and consistent messages about the beliefs and behaviors that are valued in that space, simultaneously facilitates higher consensus and more beneficial outcomes for students.

Importantly, quantitative research shows that both aggregated student perceptions (i.e., climates) and individual variation around those aggregated perceptions (i.e., microclimatesFootnote1) can play unique roles (Dicke et al., Citation2021; Morin et al., Citation2014; Parrisius et al., Citation2020). For example, Dicke et al. (Citation2021) found that students’ individual perceptions of their teacher’s cognitive support predicted their utility value for math, controlling for class-average perceptions of cognitive support predicting class-average utility value. In contrast, Morin et al. (Citation2014) found that classroom-level perceptions of the motivational climate (i.e., classroom mastery goal structure, challenge, and teacher caring) related more strongly to class-average self-efficacy than relations between the same constructs at the individual level. Although this evidence largely comes from quantitative research, qualitative consensus and variation may function similarly. Indeed, in their study using focus group responses to videos of autonomy-supportive teaching, Wallace and Sung (Citation2017) illustrated “the co-construction of meaning that occurs through ongoing social interaction in classrooms” (p. 9).

Distinctions between motivational climate and microclimates have been acknowledged for many years methodologically (Lüdtke et al., Citation2007, Citation2009; Morin et al., Citation2014), and to some extent conceptually (Bardach, Yanagida, et al., Citation2020; Marsh et al., Citation2012; Seidel, Citation2007). Robust statistical techniques, such as multilevel latent models that simultaneously represent individual- and group-level student perceptions, are increasingly visible in educational psychology studies over the past several years (e.g., Gilbert et al., Citation2022; Martin et al., Citation2021). However, uptake and accurate interpretations of the results of these methods will be hampered if conceptual confusion about the nature of these processes continues to persist (Marsh et al., Citation2012). Acknowledging that a student’s report of their classroom climate consists of their subjective perceptions—some shared with their classmates () and some unique to that student ()—can clear up some of that persistent confusion.

Distinguishing motivational climate and microclimates from motivational supports

It is important to acknowledge that shared student perceptions (i.e., motivational climate) and individual variation in perceptions (i.e., motivational microclimates) are both also conceptually distinct from what is actually happening in the classroom—motivational supports. Research demonstrating differences between student perceptions and reports from teachers or outside observers (Fauth et al., Citation2020; Wagner et al., Citation2016) provides evidence for this conceptual distinction between observable occurrences and the resulting climate and microclimates. For example, Parrisius et al. (Citation2020) modeled climates and microclimates alongside teacher-reported supports, showing each of these three processes contributed uniquely to predicting student motivation.

Each of these broad classifications of classroom processes—motivational supports, motivational climate, and microclimates—represents different observer perspectives and units of analysis. The unit of analysis for motivational climate is necessarily at the whole group level, centering the shared perspectives of the students. In contrast, microclimates require a focus on individual or small group perspectives that deviate from the larger group’s shared narrative. Motivational supports are conceptualized with the teacher or classroom as the unit of analysis, and center the observable behaviors, structures, and policies that together are assumed to give rise to the motivational climate and microclimates via students’ perceptions. Motivational supports can be directed toward the entire class, or to individuals or small groups of students rather than a whole class. Thus, pathways from motivational supports to climate and microclimates can be somewhat complex in terms of unit of analysis.

For example, a teacher’s provision of high-quality feedback to the entire class is a classroom-level support, but if the teacher provides high-quality feedback only to an individual student, this is a student-level support process. If the teacher’s quality of feedback varies across students, it is logical to expect that students will perceive the teacher’s feedback differently, so this student-level support process—quality of feedback—will likely be more relevant for microclimates than for climate. However, if students differ in their needs or preferences for feedback, consistent quality of feedback as a classroom-level support is unlikely to be perceived similarly, so will also be more relevant for microclimates than for climate. It is also possible students could arrive at a high level of consensus about the quality of the teacher’s feedback even if the actual feedback quality varies from the teacher’s or observer’s perspective; this would be an example of individual-level supports shaping shared climate. It is important to remember that a support does not “become” climate, but rather it is students’ perceptions of support that constitute the climate, so supports can only shape the climate indirectly.

Indeed, climate as students’ perceptions and interpretations of motivational support surely develops over time as a result of individual, collective, and historical experiences. For example, an observer in a mathematics lesson might note motivational supports, such as the teacher’s warm, enthusiastic teaching and their use of a cooking example to show the relevance of fractions and decimals. The observer would be well-justified in “counting” each of these supports as contributing to higher potential for a motivating climate. However, if the teacher has not previously delivered content in this enthusiastic manner, or the students do not like the teacher, then students may not benefit from the enthusiasm, perhaps believing the teacher is being insincere due to the observer’s presence. Or it may be that the teacher’s enactment of enthusiasm may be unique to the teacher’s culture, and thus for students from different cultures, the meaning and motivational impact of the teacher’s demeanor may not function as the teacher intended. On the other hand, if the teacher’s real-life cooking example was part of an ongoing theme selected by the students due to their interests, the outside observer would be rightly “counting” this feature of the teaching as having positively motivational potential, but would be missing the deeper meaning students attach to this example. Indeed, in their study on students’ explanations of autonomy supports in videos of instruction, Wallace and Sung (Citation2017) found that students explained the significance of their teacher’s actions—the climate that arose from teacher supports as narrated by the students—in terms of the broader forces (e.g., testing policies) and ongoing interpersonal connections that students saw as prompting and giving meaning to the teacher’s autonomy-supportive behaviors.

In addition to the support and climate classifications provided in , some concrete examples illustrate how measures used in extant research can be categorized as motivational support, climate, or microclimate assessments. Patall et al. (Citation2017) assessed students’ daily perceptions of autonomy-supportive and -thwarting practices, asking them to rate teacher practices, such as “My teacher worked my interests into his/her lesson(s) today.” According to the proposed definitions, these teacher actions are correctly described as supports, however, students’ responses to these questions are more accurately characterized as indicators of climate and microclimate. And indeed, the amount of variance in students’ ratings was almost equally attributable to individual differences between students (37–57%; microclimates) as it was to differences between days (33–55%; climates), and an even smaller amount of variance was attributable to between-classroom differences (3–17%). Similarly, Byrd and Chavous (Citation2011) measured school racial climate by asking students to rate the frequency of events that would best be described as supports for racial climate, such as peers of different races sitting together in the cafeteria or teachers showing equal respect to students of different races, along with less tangible processes, such as ambient respect among students of different races or racial tension between teachers and students. The reliability and factor structure of these measures provides evidence that students respond similarly to questions about specific supports as they do to questions about broader climate, or the “feel” of the context. Thus and importantly, students’ responses to perceived support questions are likely not accurate indicators of motivational support, but instead consist of students’ interpretations of the context which, by definition, is motivational climate (including microclimates).

Just as self-determination theory differentiates between need support and need satisfaction, the conceptual distinction between specific supportive actions and the resulting “feel” of the class—motivational climate—may indeed be important for understanding empirical disconnects among teacher behaviors, students’ perceptions of those behaviors, and their resulting motivational shifts or stability. Additional work is needed to determine whether and how it may be fruitful to apply conceptual distinctions between support and climate processes to intervention, measurement, and analysis approaches.

How motivational support and climate arise

School, community, policy, and sociohistorical systems

Although motivational climate and microclimates cannot be reduced to the sum of their parts, or a simple combination of the motivational supports present in the environment, a few important processes can be highlighted as key contributors to motivational supports and climate. First, although classrooms are assumed to be the most immediate, proximal contexts where students’ motivation for learning is shaped (Pianta & Hamre, Citation2009; Ryan et al., Citation2019), it is important to acknowledge that classrooms are inextricably linked with broader school, neighborhood, home, municipal, policy, and sociohistorical systems (), and thus classrooms often act as delivery mechanisms of or reactions to these broader systems (Bronfenbrenner, Citation1977; Kumar et al., Citation2018; Wallace & Sung, Citation2017). These broader forces are assumed to shape not only the amounts but also the meanings and links among the various processes in the model, including teachers’ and students’ beliefs and characteristics (), which are assumed to play central roles in support processes.

Teachers’ roles

Second, teachers’ own beliefs and characteristics are assumed to partially explain the nature and amount of motivational supports in their classrooms (Lauermann & Butler, Citation2021). Although longitudinal and experimental evidence is scant, the available literature documents relations among teachers’ motivational beliefs, emotions, and their use of motivational supports (Daumiller et al., Citation2022; Frenzel et al., Citation2021; Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017; Roth, Citation2014). For example, Daumiller et al. (Citation2022) summarized and added to evidence of cross-sectional links between teachers’ goals and practices: in classrooms where teachers held mastery goals for themselves and their students, students were more likely to report perceptions of mastery-oriented practices and a higher mastery goal structure. From a situated expectancy-value theory perspective, Parrisius et al. (Citation2020) showed that teachers’ self-reported enthusiasm for math and for teaching were correlated with student-perceived teacher enthusiasm, use of everyday life examples, and relevance support. Self-determination theory research has similarly supported links and mechanisms by which teachers’ autonomous motivation influences their autonomy-supportive teaching (Pelletier et al., Citation2002; Roth, Citation2014); Jang and Reeve (Citation2021) actually increased autonomy-supportive instruction via an experimental manipulation of teachers’ intrinsic instructional goals. Nevertheless, as Parissius et al. (2020) noted, “For values to be transmitted, it is probably necessary for teachers to enact their values and for students to perceive this behavior” (p. 3); teachers’ beliefs and behavior cannot be assumed to correspond perfectly.

Motivational beliefs are also not the only characteristics assumed to shape teachers’ use of motivational supports. Growth mindset researchers have speculated that teachers’ “theories of motivation,” or beliefs about how they can motivate students, play a role in the motivational supports they provide (Haimovitz & Dweck, Citation2017). Teachers’ theories of motivation are likely complex, relying not only on teachers’ broad beliefs about the nature, amount, and malleability of their students’ motivational beliefs, but also their knowledge of motivational strategies and their confidence those strategies will be successful. Thus, teachers’ beliefs about their students, such as their expectations for what students can achieve and their assessments of students’ needs, may be especially key for the motivational supports they provide. Importantly, teachers may not always be consciously aware of the beliefs they hold that impact their teaching, and that can ultimately impact the classroom climate and microclimates. Implicit beliefs, such as implicit bias toward white over Black students, are linked to motivationally supportive teaching behaviors (DeCuir-Gunby & Bindra, Citation2022; Kumar et al., Citation2022).

Further, the extent to which teachers translate their beliefs into action is at least partially determined by their experience and skill levels, along with the affordances and constraints in their contexts (; Bardach & Klassen, Citation2021; Kunter et al., Citation2013). A teacher with a well-developed repertoire of successful motivational supports will be more likely to use a motivational strategy than a teacher with fewer strategies or past successes. Further, a teacher may believe in the importance of providing opportunities for choice to facilitate students’ autonomy, but outside pressure to cover material quickly or to use a more controlling style endorsed by school leadership could prevent the teacher’s enactment of that belief. Additional research is needed to elaborate the key teacher and contextual characteristics that shape teachers’ use of motivational supports, in particular the mechanisms by which beliefs translate into motivational supports.

In addition to acting on their own beliefs, relying on their skills, and responding to environmental demands, teachers enact motivational supports in response to students’ behaviors and characteristics, and this can happen in at least two ways. First, the teacher may consider the whole class and individual students when making broad instructional decisions (e.g., curriculum, course structures, procedures). Second, the teacher may adjust their motivational supports in the moment as a response to students’ immediate behaviors. In alignment with this view, Wallace and Sung (Citation2017) distinguished between autonomy-supportive actions, or proactive behaviors originating from the teacher, and teacher responses, or behaviors that are prompted by input from students. Again, it is important to acknowledge that teachers’ perceptions of students may implicitly or explicitly inform teaching practices, as illustrated by research showing differential treatment of students from different ethnic groups (İnan-Kaya & Rubie-Davies, Citation2022; Skiba et al., Citation2011) and genders (Myhill & Jones, Citation2006; Sadker & Zittleman, Citation2009).

Students’ roles

Third, and mirroring teacher processes, students’ beliefs and characteristics give rise to behaviors which can then in turn contribute to the classroom motivational climate. For example, a student with a strong growth mindset and the skills to enact that growth mindset will likely behave and speak accordingly, and this behavior can then act as a motivational support for their peers. Although peer motivational support or climate is often studied separately from teacher-initiated supports (cf. Wentzel et al., Citation2018), the two are likely quite intertwined. In addition, although teachers certainly exert more power than students over certain aspects of the classroom, students and teachers and their relationships likely work together simultaneously and dynamically, rather than causally and unidirectionally, to produce supports and climate. Evidence regarding the specific roles of peer motivational climate, particularly how it works in tandem with teacher-initiated motivational climate, is limited, and most work on peer motivational climate has been conducted in physical education and sports settings (cf. Madjar et al., Citation2019; Wentzel et al., Citation2018).

Students’ characteristics and beliefs are also assumed to shape the motivational climate via their perceptions of motivational supports. Growing evidence shows students’ characteristics and prior experiences, perhaps especially their motivational traits and states, color their perceptions of motivational supports and thus their reports of motivational climate (Fauth et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2022). As Ames (Citation1992a) emphasized, “the [individual] adoption of a particular achievement goal serves to trigger a ‘program’ of cognitive processes that are related to how individuals attend to, interpret, and respond to informational cues and situational demands” (p. 327). Just as someone might perceive a room as being very warm after entering from wintery weather, whereas another feels too cold due to their inactivity that day, students’ prior experiences, identities, beliefs, and states can “prime” how they perceive and respond to motivational supports, and thus their microclimates and climate (Robinson et al., Citation2022; Schenke et al., Citation2018; Schweig, Citation2014). The specific processes and key factors shaping students’ differential perceptions and reactions to motivational supports are largely uncharted in the motivation research landscape (cf. Göllner et al., Citation2018). Considering classroom features, including student and teacher behaviors, as causal determinants of students’ psychological states is surely an overly simplistic and deterministic explanation of processes that are perhaps best understood as complex, dynamic, and situated (Hilpert & Marchand, Citation2018; Nolen, Citation2020). Motivational supports and climate are likely emergent, more than the sum of their parts, and “stretched across” individuals in context (Hickey & Granade, Citation2004, as cited in Nolen et al., Citation2015, p. 237).

Nature of motivational support, climate, and microclimates

Extant research also provides some helpful insights into the nature and roles of motivational classroom processes. The triadic model from social-cognitive perspectives provides an excellent overarching framework (Bandura, Citation1986) because of its assumption that humans are active participants in their contexts, exerting influence over their contexts in addition to individually perceiving and interpreting their experiences in that context (Patrick et al., Citation2016). Using this overarching framework, Wang and Degol (Citation2016) noted two important characteristics of climate: multidimensionality and malleability. Because Wang and Degol’s (Citation2016) definition of climate includes supports in addition to climate processes, it is reasonable to assume that both climate, including microclimates, and supports are multidimensional and malleable. A third characteristic of motivational supports and climate—relativity—arises from achievement goal, stage-environment fit, and psychological affordance perspectives that emphasize the importance of students’ varying needs and readiness in determining the meanings and impacts of contextual processes (Eccles & Roeser, Citation2009; Murayama & Elliot, Citation2009; Walton & Yeager, Citation2020).

Dimensionality

Major theoretical frameworks provide guidance about the dimensions of teaching that contribute to supporting students’ motivation. Some frameworks focus explicitly on dimensions of motivational support. For example, important dimensions from an achievement goal theoretical perspective consist of practices aligning with TARGET’s six dimensions: task, authority, recognition, grouping, evaluation, and time (Epstein, Citation1988). Alternately, need-supportive teaching frameworks from a self-determination theory perspective organize teacher practices according to the three basic needs, including supports for autonomy, competence, and relatedness (Jang et al., Citation2016). Several theoretically integrative perspectives also exist (Kumar et al., Citation2018; Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., Citation2016; Patrick et al., Citation2016; Pintrich, Citation2003; Turner et al., Citation2014), although support and climate processes are less clearly distinguished in some of these perspectives.

Notably, Kumar et al. (Citation2018) highlighted how support principles from motivation theory (i.e., meaningfulness, competence, autonomy, and relatedness) overlap a great deal with principles from culturally responsive and relevant education perspectives. Indeed, findings, such as those from Byrd and Chavous (Citation2011; Byrd, Citation2017) on the role of racial climate in predicting belonging and intrinsic motivation highlight the importance of considering cultural processes as integral parts of motivational support and climate dimensions. Conceptualizing motivational support and climate dimensions in a way that directly acknowledges the cultural nature of teaching and learning has great promise for improving theoretical understanding and more equitable access to motivating instruction.

To organize motivational support dimensions, many perspectives include groupings of teacher practices according to which student-level motivational process is the target of the teaching practices (e.g., Linnenbrink-Garcia et al., Citation2016; Patall et al., Citation2022). And in some studies, dimensionality propositions are supported by factor analyses indicating that students or outside observers can indeed identify separable, discrete dimensions of support or climate features (Assor et al., Citation2002; Bardach et al., Citation2019). However, different theorized facets of motivational support and other types of teacher support are often very highly correlated (Mantzicopoulos, Patrick, et al., Citation2018; Morin et al., Citation2014), and in other cases, processes researchers think of as different dimensions (i.e., separate constructs) actually do not empirically separate when measured via student perceptions (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Additionally, as Patall et al. (Citation2022) noted, teacher practices that are conceptualized as supporting one motivational belief can often actually support other beliefs in addition to or instead of the one belief. These issues raise questions about whether teachers who enact one type of motivational support typically also enact others if students or observers are subject to rating tendencies like halo effects, and if different conceptualizations of dimensionality should be considered. Dimensionality of motivational support and motivational climate processes are certainly areas in need of future research. Student behaviors may be important to consider as dimensions of motivational support alongside teacher behaviors. Considering dimensionality of motivational supports separately from dimensionality of motivational climate may also be particularly fruitful.

Another important quality of motivational supports and climate is that the various dimensions do not occur in isolation. Rather, multiple motivational support and climate processes are assumed to co-occur and to have combined effects. This combinatory tenet of dimensionality arises from theoretical assumptions, such as self-determination theory’s propositions that supports for multiple basic needs are more powerful than support for only one (Ryan & Deci, Citation2020). Research on the interactive term (expectancy × value) within the expectancy-value literature (Trautwein et al., Citation2012) has also emphasized the importance of supporting both expectancy for success and task value to best equip students for success. Achievement goal theorists have also discussed coordinated patterns of teacher behavior, referring to the six TARGET dimensions of mastery goal structures as interrelated and overlapping: “if these dimensions are not coordinated, the positive impact on student motivation of one structure…may be undermined or negated by the lack of attention to another structure” (Ames, Citation1992a, p. 343). Combined effects should not be assumed to be only quantitative in nature (i.e., additive or multiplicative); the qualitative meanings of motivational support and climate processes may also change when combined with other processes (Wallace & Sung, Citation2017). For example, students may interpret a historical story about a chemistry discovery quite differently based on the teacher’s delivery (enthusiastic vs. flat tone), or if the teacher is using the story to highlight social comparisons vs. personal improvement and mastery.

Although findings are mixed (e.g., Olivier et al., Citation2021; Vazou et al., Citation2006) and much more research is needed, this assumption of additive and interactive effects is at least partially supported by extant literature (Jang et al., Citation2010; Linnenbrink, Citation2005; Sierens et al., Citation2009), as is the assumption that the meanings of motivational supports can differ based on the presence of other motivational supports (Wallace & Sung, Citation2017). Importantly, the motivational climate is likely complex and not easily reducible to the sum of its parts. Thus, although it may be fruitful for researchers to focus on separate and combined motivational supports, along with various facets of the motivational climate, a “true” and holistic depiction of the motivational climate in a course is unlikely to be captured only via the combined additive or multiplicative effects of the perceived motivational supports in that environment.

Malleability

Motivational supports, and thus the motivational climate that arises as students’ perceptions of those supports, are assumed to be malleable—they can change. Malleability is an important aspect of motivational support and climate as researchers and practitioners consider ways to make classrooms more motivationally supportive. As teachers change their practices to better align with their students’ needs and perceptions, this in turn should create a more positively motivational climate (Bardach, Oczlon, et al., Citation2020). Changes can be made to classroom supports purposefully, such as through interventions or professional development (Jang & Reeve, Citation2021; Turner et al., Citation2014). Teachers’ supports for motivation are also assumed to change naturally due to the accumulation of experience, varying resources and outside pressures, or varying student needs (Brophy, Citation2006; Mantzicopoulos, French, et al., Citation2018). Malleability can be difficult to account for in motivational support and climate studies, wherein researchers often observe a limited selection of indicators and use those to infer the classroom’s broader motivational patterns. Understanding to what extent prevalent research practices provide valid indicators of motivational support and motivational climate is an important area in need of future study.

Just as supports can change, their benefits (i.e., alignment with the needs and perceptions of the students) are also assumed to vary over time, and thus the resulting motivational climate that arises from motivational supports can change even if the supports themselves do not. As Eccles and her colleagues have asserted over the years (Eccles & Midgley, Citation1989; Eccles & Roeser, Citation2009), individuals’ needs change over time as a function of development, so school policies and practices should ideally differ across stages of education to best fit and respond to those changing needs. This aspect of malleability relates to another tenet of support and climate: relativity.

Relativity

In addition to dimensionality and malleability, a third important characteristic of motivational supports as psychological affordances, described by Walton and Yeager (Citation2020), is that their qualities and benefits are relative: “An all-male club may afford belonging to men but not to women” (p. 220). In other words, each specific support is assumed to have differing effects for different students. This aligns with achievement goal theorists’ conceptualizations of contextual processes as interacting with the varying characteristics of individuals within the context. For example, Murayama and Elliot (Citation2009) found that classroom achievement goal structures predicted students’ intrinsic motivation and academic self-concept not only directly and indirectly via individual achievement goals, but also showed evidence of interaction effects (i.e., goal match and mismatch effects; Murayama & Elliot, Citation2009). Evidence from a nationally-representative growth mindset intervention study indicated the intervention was only beneficial to students’ grades when their teachers endorsed a high growth mindset (psychological affordance; Yeager et al., Citation2022). And as a final example, my own work has shown that students rate the extent of the motivational qualities of their classrooms (e.g., autonomy supports, teacher mastery goals, and teacher warmth and enthusiasm) differently within the same large lecture course (Robinson et al., Citation2022). Motivational supports can take on different meanings to different groups and individuals, with implications for the motivational climate and microclimates that arise. The impacts of a motivational climate or microclimate are also assumed to vary for different individuals or groups (see also Thoman et al., Citation2017). Describing and explaining heterogeneity in students’ needs, perceptions, and responses to motivational support and climate processes as a function of development and individual differences is a promising area for future motivation research (Bryan et al., Citation2021).

Mechanisms of support and climate effects

Motivational climate and microclimates are assumed to shape student outcomes, and the most relevant, proximal outcomes are of course motivational in nature. For example, a classroom that shows a high number, consistency, and quality of supports for mastery goals, and subsequently shows a strong mastery goal climate (i.e., high consensus as well as high levels of student-reported mastery goal climate) due to students’ attention to and appraisals of those supports, should also have higher mean levels of mastery goal orientations among its students. Various theoretical perspectives, such as self-determination theory (Reeve & Cheon, Citation2021; Ryan & Deci, Citation2020), outline these processes in detail, and thus I will not replicate those explanations exhaustively here. The sequence of events, generally, is assumed to unfold as follows: (1) the teacher enacts a motivationally supportive practice, (2) students generally perceive and appraise that practice as contributing to a motivationally supportive climate, and (3) the group then reacts by raising their average level and/or quality of motivation, or maintaining a previously high level and/or quality of motivation.

However, as described in the previous section on relativity, motivational supports, and climate are also not assumed to affect every student in the same way; students have unique and varying responses to what is happening and how they perceive it (Bryan et al., Citation2021; Robinson et al., Citation2022). Over and above any changes in aggregate student outcomes, individual students are assumed to have some idiosyncratic perceptions, resulting in motivational microclimates and thus, unique motivational reactions. For example, a particular type of praise from the teacher may evoke increases, declines, or stability in self-efficacy for various students in the class due to students’ varying needs and perceptions of that praise. Nevertheless, the sequence of events unfolds in parallel to the general process for the classroom level outlined above: (1) the teacher provides motivational support, (2) students variously attend to and interpret the teacher’s actions as motivating, neutral, or demotivating (i.e., microclimates), and (3) individual students show corresponding increases, stability, or declines in their motivational levels and/or quality. Overall and as a result, the ultimate effects of motivational support on different individuals within that climate are necessarily heterogeneous. In addition, the effects of one teacher’s motivational supports can be assumed to differ from one group of students to another due to differing, shared meaning systems and interpretations of motivational supports among those who are members of each environment.

Aside from reactions to motivational supports via motivational climate appraisals, it is possible that class-level and individual responses (outcomes) might sometimes occur as direct effects of motivational support, bypassing student perception processes. For example, a classroom dominated by men’s voices may not consciously register as de-motivating to women in that setting, but may still result in lower motivation for women and higher motivation for men (Cheryan et al., Citation2009). Alternately, students may not consciously perceive their climate as motivating but may instead unconsciously model their beliefs and behavior after a teacher who portrays high enthusiasm and confidence about the course subject matter (Bardach & Klassen, Citation2021). Nevertheless, the main pathway from teachers’ actions to students’ motivation is likely via motivational climate and indeed, meta-analytic results from Bardach, Oczlon, et al. (Citation2020) indicated that students’ ratings of specific teacher practices were less predictive of students’ personal motivational orientations than were students’ ratings of the climate.

Lastly, the entire process is assumed to be cyclical over time, such that motivational climates and microclimates shape the student characteristics that inform motivational supports, attention, and appraisals in the future (, gray arrows), even just moments in the future. What is difficult to portray in a figure, but still important to consider, is that these cyclical processes are assumed to have cumulative effects over time, as both students’ and teachers’ prior experiences act as a lens through which they view their current experiences. Consider the previous comparison of a teacher who is typically not warm and enthusiastic, then suddenly acts warm and enthusiastic, to a teacher who was consistently warm and enthusiastic throughout the entire year. Considering how multiple dimensions of support are assumed to work together and accumulate over time to form the motivational climate, one dimension of motivational support over time can be assumed to “set the stage” for how students respond to other dimensions of motivational support. For example, introducing new, challenging, and anxiety-producing math problems may have a good chance of boosting students’ confidence if the teacher has already fostered caring relationships with students and has messaged the value of effort and strategy use. In the absence of previous experiences fostering such a supportive climate, anxiety-producing math problems may instead begin a downward spiral for students’ confidence, value for mathematics, and even their sense of belonging in mathematics.

Recommendations and future directions

To address a need for greater clarity about motivational support and motivational climate processes, I have proposed a framework and some key tenets about the nature and mechanisms by which motivational support and climate can shape—or fail to shape—students’ motivation. In particular, I proposed distinctions among motivational support, motivational climate, and motivational microclimates, along with definitions of these processes, their characteristics (multidimensionality, malleability, and relativity), and explanations of how these processes unfold in classrooms. Many of these propositions are in need of rigorous empirical testing to ultimately improve understanding of how classrooms can be designed to support student thriving. In particular, I highlight five key recommendations and future directions arising from the ideas outlined in this article, focused on resolving some important open questions.

Terminology

First and most importantly, considering the confusion of terms used in prior work, researchers’ attention to clearly defining, justifying, and explaining the origins of the motivational climate and support constructs they use in their research will contribute greatly toward building a cohesive body of work and understanding of motivational classroom processes. Researchers should clearly explain whether their interest is in support, climate, microclimates, or some combination of these, then frame their findings precisely in terms of the indicators they used, taking care to avoid the common practice in prior work of interpreting student perceptions as indicators of actual supports.

Like using the term “motivation” in studies examining student-level processes, the terms motivational support, climate, and microclimates alone may be too broad to be helpful for precisely describing processes under study. Construct names that refer to specific aspects of motivational support, such as autonomy-supportive teaching, or specific aspects of climate or microclimates, such as need satisfaction, are recommended as they are typically more descriptive and thus less susceptible to misinterpretation compared to broader terms, such as social climate or teachers’ motivational approach. However, including the umbrella terms motivational support, motivational climate, and motivational microclimates early in the conceptual framing will help orient readers to the focus of the study.

Methodological considerations

Second, in contrast to constructs at the student level, such as task values, self-efficacy, and achievement goals, motivational support, and climate research lacks well-developed, widely used procedures for measurement and modeling and suffers from “scant justification” (Wang & Degol, Citation2016, p. 339) for the methods used. Researchers often create their own measures or adopt measures from other literatures (e.g., classroom quality), and thus measures used in extant research vary widely in their characteristics. As a result, the cognitive processes involved in answering questions about support and climate, and the implications of various reference points (e.g., we vs. the teacher vs. this class), reporters (i.e., students, teachers, observers), and timeframes (i.e., in general vs. now vs. the past) remain largely unexplored (cf., Jaekel et al., Citation2022; Karabenick et al., Citation2007). Research uncovering the information students rely on when answering motivational climate questions would be an important step for informing both conceptual and methodological advances.

Relatedly, there is also an urgent need for better quantitative and qualitative methods for studying motivational support and climate. Considering the extensive overlap across theoretical perspectives in their recommendations for instructors, assessments of motivational support and climate would ideally be theoretically integrative, focusing on the most important classroom processes identified across theoretical traditions. In addition, assessments should be designed to clearly acknowledge distinctions among support, climate, and microclimates. High student motivation or positive shifts in student motivation alone cannot be used as indicators of effective motivational climates; rather, researchers might aim to implement Brophy’s (Citation1986) recommendations for process-product research to more systematically examine teachers’ motivational teaching behaviors. Educational psychologists, historically attentive to measurement and validity, can lend considerable skills to this challenge.

It is important to note that the logic of observable supports giving rise to climate via perception is in contrast with the logic of latent constructs, which assumes that unobservable latent constructs give rise to observable indicators. Instead, observable features are assumed to dynamically give rise to the emergent motivational climate. Motivational climate and microclimates, on the other hand, are indeed latent (i.e., unobservable), and thus students’ answers to climate questions are assumed to arise from their mental representations of the classroom. Different climate processes likely have different ratios of classroom-level variation (i.e., consensus about the climate) to between-student variation (i.e., idiosyncratic reports), perhaps depending on the degree of objectivity and subjectivity in measures of the constructs, the timeframes used in the measures (e.g., today vs. generally), and the consistency of actual supports in the environment. Research examining why measures differ in their sources of variance could prove fruitful for informing theoretical and methodological innovation. Further, when survey measures of student-perceived classroom-level (L2) processes are a focus, researchers should ensure the data reflects some consensus as to the shared L2 experience and apply appropriate modeling techniques, including careful attention to whether and how to center student perception data (see Lüdtke et al., Citation2009), to partition variance accordingly. Qualitative reports of motivational climate can similarly be achieved through identifying shared narratives among members of the class.

Lastly, considering the unique nature of climate and motivational support processes, it may be best to study these processes using longitudinal methods and, importantly, using multiple methods rather than direct observation, teacher reports, or student reports alone (Ruzek & Pianta, Citation2015). Researchers must consider how sociocultural, historical, and relational processes shape students' experiences in ways that cannot always be directly observed. Using multiple methods allows researchers to leverage the unique information provided by various raters and the meanings they make of classroom processes, while also allowing for triangulation of these multiple perspectives for a more accurate picture of what is happening in the classroom. Schmidt et al. (Citation2019) use of student perceptions, teacher interviews, and repeated classroom observations to illustrate the nature, amount, and correlates of teachers’ relevance statements in science classes is an excellent example of how multiple methods can not only address key methodological and theoretical questions (Ruzek & Pianta, Citation2015) but can also amplify applications of motivation research to real-world settings through a better understanding of the specific conditions under which theoretical principles “work”—or not. There is a particular need for qualitative work to strengthen an understanding of what motivational support, climate, and microclimates mean to students and teachers in real-world classrooms.

Dimensionality

Third, what are the key dimensions of motivational support and motivational climate? There is ample room for theory-building and empirical testing to clarify the number and nature of support and climate dimensions that contribute meaningfully to predicting students’ motivational outcomes. Identifying dimensions that (a) make sense to various observers (i.e., reflect real experiences of students, teachers, and observers in classrooms), (b) yield valid and meaningful results from these various observers, and (c) balance precision with parsimony should be prioritized. In addition to centering theoretical advancements, it is very important that dimensionality is examined with the explicit practical aim to “identify features of the school environment that can be altered to improve student outcomes” (Wang & Degol, Citation2016, p. 217) and with a particular eye to improving equitable access to motivating instruction. It is interesting to consider, also, that the number and nature of motivational support or climate dimensions may necessarily differ based on the aims of the research and how the dimensions will be assessed. For example, work by Schweig (Citation2014) indicated that the factor structure of student-perceived school environment measures cannot be assumed to be the same at the student and classroom levels. Thus, dimensionality may need to be conceptualized differently for different populations, or even across motivational support, climate, and microclimates.

Interventions

Fourth, what are the best ways to intervene and enhance classroom motivational climates? Intervention researchers have increasingly acknowledged the importance of contextual processes as facilitators of student success (Rosenzweig & Wigfield, Citation2016; Walton & Yeager, Citation2020). In particular, it is important that researchers improve methods for adequately assessing existing motivational processes in context as an initial, essential step before considering intervention designs. Longitudinal design-based research, research-practice partnerships, and improvement science approaches may be particularly well-suited for implementing motivational supports that account for the sociohistorical, situated meanings and needs of students in particular contexts (Gray et al., Citation2020; Lewis, Citation2015; Nolen et al., Citation2015). Such approaches may be especially effective at both maximizing motivational opportunities for students in those contexts and building a theoretical understanding of how motivational supports and climates function.

A specific consideration for interventions is the question of whether it is best to focus on teachers’ beliefs or behaviors, or something else altogether when aiming to enhance motivational climates. For example, focusing on teacher beliefs will not work if teachers’ beliefs and behaviors do not correspond with each other, if teachers do not need adaptive beliefs to successfully support motivation, or if teachers are unable to implement motivational supports due to external barriers. It may be that supporting both beliefs and behaviors, along with removing external barriers when possible, may be the most successful approach. This would require that motivation researchers become involved in educational policy or school administration (e.g., Maehr & Midgley, Citation1996; Nichols, Citation2019). It is also likely that the approach that works best to improve motivational climate differs according to which setting, behavior, or climate quality is being targeted.

Explaining differential perceptions and reactions

Lastly, what are the key factors explaining differences in students’ attention, appraisals, and responses to motivational supports? Previous research provides hints that students’ motivational beliefs, preferences, and their personal and academic backgrounds play roles in shaping their responses to motivational climate surveys (Bardach et al., Citation2021; Fauth et al., Citation2020; Karabenick et al., Citation2007; Robinson & Lee, Citation2022; Schweig, Citation2014). However, much more research is needed to outline the specific processes explaining students’ heterogeneous perceptions and reports of their classroom environments. Examining cultural processes, including the broader sociohistorical milieu, may be especially fruitful for understanding perceptual and appraisal differences, as students’ cultural backgrounds are “not just ‘out there’ in the macrosystem but an integral part of the microsystems of all youth” (Kumar et al., Citation2018, p. 79).

In particular, it is important to incorporate race-focused, race-reimaged, critical, and cultural processes into models of the motivational climate, following the examples of scholars, such as DeCuir-Gunby (Citation2020), Gray et al. (Citation2018), Matthews and López (Citation2020), and Kumar et al. (Citation2018). Current claims about the nature and functions of motivational support and climate processes are still overwhelmingly reflective of the whiteness of motivation research (Usher, Citation2018) and too often reinforce majority narratives rather than undermining systems of oppression that perpetuate inequitable access to motivating instruction.

Implications and conclusions

Despite decades of productive, impactful research examining the implications of classroom experiences for students’ motivational beliefs, clarity about contextual motivational processes has remained elusive in educational psychology and beyond (Parker et al., Citation2003; Woolfolk Hoy, Citation2021). Accordingly, I have proposed Motivational Climate Theory, which includes definitions and mechanisms of key processes based on empirical findings to date, as a path toward clearer and more unified understandings of classroom motivational processes in psychological research. The proposed theory can help researchers using a variety of specific theories, and can also help them more effectively consider theoretical integration, by organizing processes under the broad framework of motivational support, motivational climate, and motivational microclimates, thus supporting theoretically-driven approaches to data collection, analysis, and synthesis across multiple studies. The study of motivational support and climate may be criticized as a move away from the traditional focus on the individual in psychological research. However, the study of psychological climate and support in real classrooms may in fact be the best way to understand the true nature of motivational processes. Indeed, researchers embracing situated views of motivation critique the separation between person and context (Nolen, Citation2020).

Motivational Climate Theory’s definitions and mechanisms may be adaptable to other organizational contexts, such as work settings, which share key characteristics with classroom settings, as well as to a broader set of psychological processes (e.g., self-regulation, emotions, cognition, or well-being). For example, supports for well-being in the workplace would consist of supervisor and employee behaviors that are relevant to the employees’ well-being, and the corresponding psychological climate would consist of employees’ shared perceptions of how well the workplace supports their well-being. However, rich motivation theories and research in education provide an ideal context for illustrating support and climate processes, and the application of psychological climate principles to classroom motivational processes reflect current needs and trends in the field of motivation research. The need for and implications of a broader theory of “psychological climate” remains to be seen.

Motivational climate and support are also worthy of focus for practical reasons, as aside from the benefits of high quantity and quality of motivation for achievement and academic choices, motivational beliefs are important outcomes by themselves. Students who are highly motivated make their own work and their teachers’ jobs easier. Motivating students should not be an additional task teachers have to do, but rather something that can be infused into everything they are already doing, with the aim of facilitating rather than complicating teachers’ jobs and students’ path to success.

By proposing Motivational Climate Theory, I aim to move discourse in educational psychology toward more accurate descriptions of contexts, including boundary conditions of classroom motivational support and climate processes. In particular, I aim to improve researchers’ inferences and concrete recommendations about what, when, how, and for whom motivational supports should work. Further, understanding how motivational support and climate function is an essential step in advancing antiracism in educational psychology. Specifically, working to improve educational contexts is an important complement to student-focused intervention research (e.g., Murphy et al., Citation2020), which could be construed as a kind of inoculation against demotivating, unwelcoming, or unsupportive contexts. A more robust understanding of motivational support and climate can be used to inform broader classroom quality perspectives that have thus far largely lacked input from motivation researchers, and for empowering motivation researchers to shape education policies that make education more equitable and effective in smoothing students’ pathways to achieving their valued goals.

Notes

1 Microclimates are here used to refer to the unique experiences of individual students and subgroups within a classroom (Seidel, Citation2007); researchers studying small groups may consider an additional distinction, such as using “meso-climates” to refer to groups of students within a class. The current lack of evidence and theory about this potential distinction between micro- and meso-climates suggests a need for further investigation.

References

- American Psychological Association. (2021). Apology to people of color for APA’s role in promoting, perpetuating, and failing to challenge racism, racial discrimination, and human hierarchy in U.S. Resolution adopted by the APA Council of Representatives. Retrieved July 6, 2022, from https://www.apa.org/about/policy/racism-apology

- Ames, C. (1992a). Achievement goals and classroom motivational climate. In J. Meece & D. Schunk (Eds.), Students’ perceptions in the classroom (pp. 327–348). Erlbaum.

- Ames, C. (1992b). Classrooms: Goals, structures, and student motivation. Journal of Educational Psychology, 84(3), 261–271. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.84.3.261