ABSTRACT

The history of education is, and can be, many things. In this article, I argue that the history of education in the Nordic countries is marked by three phases, based on its institutional setting. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the history of education was written by schoolmen for schoolmen. In the post-war era, the discipline of education took increasing responsibility for the field. Since the 1980s, it has been a multidisciplinary research field based on the disciplines of education and history where history of education was combined with research in history education, sociology of education, child studies and educational policy. While the development of the history of education varied across the Nordics, this setting proved to be fertile. In terms of active researchers, output and coordination, the Nordic history of education clearly stands stronger now than it did 20 years ago.

In 1980, the historian and educationalist Gunnar Richardson (1924–2016) published an article with the telling title: ‘Is the History of Pedagogy Forgotten?’Footnote1 Similar pessimistic views on the quality and quantity of the Nordic history of education were expressed in the 1990s and early 2000s. Had the history of education lost its place in educational research and teacher training departments in Sweden? Was it losing ground in Norwegian educational research, and on the verge of becoming extinct in Finland?Footnote2

While such gloomy accounts may have been debatable at the time, they certainly did not predict future developments. Research into the history of education in the Nordic countries has expanded in volume, scope and coordination since the 1980s and early 1990s, and is now well established at several universities as a multidisciplinary field. The aim of this article is to describe these advancements, starting from the context of the educational system in general, and higher education in particular, and changes within the humanities and the social sciences. What are the main institutional changes that shaped this field of research? What are the main research environments in the Nordic history of education, and the field’s current main topics of interest? Finally, what is the future of this field of inquiry?

In this article, I will argue that the history of education in the Nordic countries has been marked by three overlapping phases. From being a school history written by schoolmen in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, an academic history of education primarily based in the discipline of education emerged during the post-war era. From the 1980s onwards, a multidisciplinary, increasingly coordinated research field was established in the expanding higher education sector, with its main basis in the disciplines of education and history. In these institutions, the history of education was combined with research in history education, sociology of education, child studies and educational policy. I will thereafter argue that both the main strands of this research field, as well as its future, depend on this institutional context of massified higher education of the Nordic countries. Instead of international theoretical trends, it is this setting that has primarily shaped the field’s dominant topics, theories and methods.

Delimiting this article to the Nordic countries is not a self-evident choice.Footnote3 The historical experiences of education follows distinct historical trajectories – consider merely the development of primary schooling in Finland under Russian rule from 1809 to 1917. The current dominance of the Swedish research field, in terms of active researchers and externally funded projects, also affects how we define a Nordic field. Currently, the Nordic network, the Nordic conferences in the history of education, and the Nordic Journal of Educational History are all coordinated from universities in Sweden.Footnote4 In addition, the Nordic countries are themselves a historical construct, worthy of the researcher’s attention. The idea of the Nordics relies on nineteenth- and early twentieth-century nationalistic sentiments that resulted in, for example, the Congress of Nordic Historians and the Nordic Educational Research Association.Footnote5

However, there are good reasons to limit this article to a Nordic context. Apart from transnational structures and identity-formation processes that create an unusually extensive collaboration which goes beyond academia, the Nordic countries share common borders, and the majority of the population speaks closely related languages. The Nordic countries also have the common experience of a Lutheran heritage, extensive post-war economic expansion, and development of universalist welfare states, placing the Nordic countries high in rankings of economic performance, education, and quality of life. In education, the Nordics have invested heavily in early childhood care and education programmes for ages 1 to 6, comprehensive school systems, and higher education.Footnote6

Nevertheless, this Nordic setting of five countries implies that the history of education in the Nordic countries is marked by significant national and regional differences. There is certainly a gap between historians of education publishing in Nordic languages and those publishing in the Finnish language. The history of education in the Nordic countries is also shaped by the national conditions of higher education. In the absence of national associations with the power to define the field, the Nordic history of education has salient local features originating from the institutional settings of specific universities. Although communication and interaction in the Nordic field has strengthened during the last two decades, the research on the history of education remains largely dependent on the specific institutional context of universities from Trondheim, Umeå and Jyväskylä in the north, to Copenhagen and Aarhus in the south.

This analysis of Nordic history of education is based on a wide selection of existing historiographic publications on the history of education in the Nordic countries, as well as studies of higher education. These were complemented by analyses of research publications listed in the newsletter of the Network of the History of Education, presentations at the Nordic conferences of the history of education, and a compilation of dissertations on educational history at Swedish universities from 1980 to 2020. Although emphasis has been placed on the Swedish case, which is the most important in terms of active researchers and output, this is an attempt to balance the accounts of educational history in the respective countries with providing examples that cover both well- and lesser-known examples of research.

School history by schoolmen

The changing content and context of the history of education allows for a wide variety of time periods. Based on a broad social and cultural contextualisation, Alfred Oftedal Telhaug distinguished between a pre-war, a post-war and a social radical generation of educational historians in Norway.Footnote7 Focusing on theoretical frameworks, the development of history of education in Denmark has been summarised in terms of conservative, whig, revisionist and post-revisionist history. In Sweden, it is possible to discern a shift from an idealistic interpretation of history, to a post-war history of education marked by source criticism, to a field characterised by the theoretical frameworks of the humanities and social sciences from the 1980s onward.Footnote8 There are also good arguments for claiming that there was a major shift in Finland around 2000, when new trends within the discipline of history affected the history of education.Footnote9

In exploring the institutional foundations of educational history in all five Nordic countries, I find it useful to distinguish between three overlapping periods: the history produced by (1) schoolmen and teachers; (2) educational researchers, policymakers and politicians; and (3) a multidisciplinary research field, with a firm basis in the disciplines of education and history. These categories can be termed as a traditional school history (skolhistoria); a post-war history of pedagogy (pedagogikhistoria); and a multidisciplinary history of education (utbildningshistoria) from the 1980s onwards, based on the disciplines of education and history. Although these categories do not tell the entire story, they nevertheless highlight certain marked features of the history of education and its institutional conditions in the Nordic countries.

During the first phase, in the second half of the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, the history of education was closely tied to the expansion of mass schooling and the emerging teaching profession. During this period, when the few Nordic universities that existed catered to a social elite, schoolmen and teachers made important contributions to the field. As Telhaug remarked in the case of Norway, this was a school history written by schoolmen.Footnote10 Marked by this context, the publications during this period generally lacked the theoretical and methodological ambitions seen in the history of education in the latter decades of the twentieth century. As elsewhere, this kind of traditional school history produced narratives that celebrated the expansion of educational systems, expressed a belief in education as a true positive force in society, and provided the readership with historical overviews and with presentations of landmark events and important educationalists.Footnote11 Examples of the latter included publications on prominent pioneers, such as the so-called father of the primary school in Finland, Uno Cygneus (1810–1888), and the father of the folk high school (Folkehøjskole) in Denmark, N. F. S. Grundtvig (1783–1872).Footnote12 As such, these publications fulfilled educational history’s traditional function – to legitimise recent investments in nation-wide school systems and to promote the cause of education and the professional pride of teachers.Footnote13

Although traditional school history in the Nordic countries was generally written from above, stressing the role of politics, politicians and legislation, it also encompassed a broad range of themes that included the material culture and the experiences of schooling. Since these narratives were linked in various ways with efforts to preserve source materials, including efforts at establishing national school museums, they did not just feature the whig ambition to present analyses of progress. In line with Friedrich Nietzsche’s terminology, these narratives also featured an antiquarian historical attitude, marked by a love for all things old and a fascination for all aspects of the educational pasts, including the experiences and the materialities of schooling.Footnote14 In Denmark, the purpose of the national association included collecting and preserving archival materials, teaching aids, and student assignments.Footnote15 The long-standing editor of the Swedish National Association’s yearbook, Bror Rudolf Hall (1876–1950), similarly argued that educational history should not only consider politics, but also preserve the memory of textbooks, exam catalogues, and even the bricks of school buildings, since they were all part of the progress of schooling.Footnote16

The efforts of this period included some remarkable general works on the history of schooling. In Denmark, Joakim Larsen (teacher and chairman of the Danish Teacher Association) published three volumes on the history of popular education and mass schooling in Denmark from 1536 to 1898.Footnote17 In Norway, the educationalist Torstein Høverstad published two volumes on Norwegian school history from 1739 to 1842 (1918; 1930).Footnote18 In Sweden, five volumes on the history of primary schools were published from 1940 to 1950, supported by the main primary school teacher union. The purpose was to provide an overview of the development of primary schooling against the background of the general cultural progress of Sweden.Footnote19 These volumes clearly provide narratives of progress, but their richness and extensive use of primary sources make them still valuable today.

In the Nordic context, national associations remained important during the post-war period. The Association for Swedish History of Teaching (Föreningen för svensk undervisningshistoria) was founded in 1920. The Finnish Society for School History was founded in 1935 (Suomen Kouluhistoriallinen Seura). The Swedish Association for School History in Finland (Svenska skolhistoriska föreningen i Finland) was founded in 1949, and the Association for School and Educational History (Selskabet for Skole- og Uddannelseshistorie) was founded in Denmark in 1966.Footnote20 These associations made fundamental contributions to the field of educational history by the sheer volume of their output. The Finnish society published 59 yearbooks between 1935 and 2019, and the Danish association published 54 yearbooks between 1967 and 2020.

The Association for the Swedish History of Teaching stands out as the most productive society, publishing 224 volumes between 1921 and 2020. Under the leadership of Bror Rudolf Hall, the association published 60 volumes by 1940, including historical investigations, collections of written memories, bibliographies and excerpts from historical sources. The purpose of these yearbooks was indicative of this early period, when historical accounts of schooling were written by schoolmen for schoolmen. Hall argued that the history of education provided lessons from the past that supported arguments to raise teacher salaries, increase school spending, and honour educators who had lifted the Swedish population from a previous barbarous state.Footnote21

Post-war educational research and school reform

During the first half of the twentieth century, the volume of research at Nordic universities remained limited.Footnote22 At Uppsala University, for example, only four dissertations in education applied historical perspectives between 1913 and 1959, while 100 volumes were published by the Association for Swedish History of Teaching between 1921 and 1959.Footnote23 However, this changed during the post-war era, marked by an expanding higher education sector.

From the 1950s, the discipline of education took on increasing responsibility for the history of education. In 1957, the University of Copenhagen offered students the option of taking history of education as part of a master’s degree in educational theory. In 1965, the Institute for Danish School History (Institut for Dansk Skolehistorie) was established at the Danish Teacher Training Institute (Danmarks Lærerhøjskole), which became a higher education institution in 1963.Footnote24 In Norway, the educational research institute at University of Oslo, and the Norwegian teacher training institute of Trondheim, became centres for historically oriented research.Footnote25

While the size of the research in educational history necessarily remained limited in terms of publications, its impact on educational research in the 1960s should not be underestimated. In Finland, 32% of the 19 dissertations in education were on the history of education in the 1960s. In Norway, 31% of master’s and PhD theses in Oslo were historically oriented during this decade. In Sweden, 38% of the 16 dissertations on education from 1960 to 1969 at Uppsala University were on the history of education.Footnote26 In terms of relative importance in educational research, the 1960s stand out as a golden age for educational history in the Nordic countries.

In this context, some features of the research changed, while others remained the same. Publications providing general overviews of the development of educational systems and ideas were still prevalent, but historians of education tended to adhere more closely to the conceptual and methodological standards of the humanities and social sciences, as part of the discipline of educational research.Footnote27 In Denmark, prominent publications were authored by Knud Grue-Sørensen, professor of education at the University of Copenhagen. These included three volumes on the history of education (Opdragelsens historie). In Norway, this post-war period was known as the Dokka period of research in educational history, named after the educational researcher Hans-Jørgen Gram Dokka (University of Oslo) who, together with Reidar Myhre (professor of education at the University of Trondheim), made fundamental contributions to this field. Myhre published Pedagogisk idehistorie (A History of Educational Ideas) in 1964, and Dokka published Fra almueskole til folkskole (From Common School to Primary School) in 1967.Footnote28

In post-war Sweden, the main scholars of educational history included John Landquist, professor of education and psychology at Lund University, and Wilhelm Sjöstrand, professor of education and educational psychology at Uppsala University (1948 to 1976).Footnote29 Landquist’s Pedagogikens historia (History of Pedagogy) was published in nine editions from 1941 to 1973, and Sjöstrand published four volumes of Pedagogikens historia (History of Pedagogy) from 1954 to 1966. Indicative of an increasing alignment to research methods in the humanities and social sciences, he also published a handbook on source criticism, arguing that the challenges facing historians of education were similar to those of educational researchers in other fields.Footnote30

In this context of educational research, the antiquarian’s fascination for all aspects of the past faded, while the interest in educational politics and policy persisted. In Norway, the dominant perspective has been described as history from above, rather than from below. This historical perspective stressed national public debate, laws, administration and educational policies.Footnote31 One reason for this emphasis was certainly the interest that the radical and encompassing school reforms sparked, including the introduction of the nine-year comprehensive school in Sweden in 1962, the nine-year comprehensive school in Finland in 1968, and the creation of a nine-year statutory school in Denmark in 1972.Footnote32

In the post-war era, several historians of education doubled in research and politics. In Denmark, Roar Skovmand left his position as a director at the Ministry of Education for a position as professor of history at the Danish Teacher Training Institute, where he managed the Institute for Danish School History.Footnote33 In Finland, the Finnish Society for the History of Education was chaired by Urho Somerkivi, head of the department at the National School Board and chair of the Comprehensive School Curriculum Committee.Footnote34 In Sweden, researchers sometimes worked on the same topics that they explored in their historical research. Gunnar Richardson, Sixten Marklund, Åke Isling and Birgit Rodhe might be mentioned in this context.Footnote35 Sixten Marklund was an educationalist and researcher who, among other things, partook in the introduction of comprehensive schooling in the 1950s and 1960s, and wrote six volumes titled Skolsverige 1950–1975 (Schooling in Sweden 1950–1975). Åke Isling, with high positions within the National School Board (Skolöverstyrelsen) and the Swedish Confederation of Professional Employees (TCO), wrote two volumes on the Swedish compulsory school.Footnote36 This context also marked the research that was generally written from above, and sometimes approached a kind of history from the perspective of the National School Board.

A revitalised multidisciplinary research field

Starting in the 1980s, a third phase of Nordic history of education emerged. Nevertheless, it is not possible discern a clear shift. Traditional, celebratory school histories and academic educational histories continued to be published, and national associations remained important and influential, particularly in Denmark and Finland. The Association for School and Educational History in Denmark continued to publish ambitious annual yearbooks, and the Finnish School Historical Society added the journal Kasvatus & Aika (Education and Time) – first issue published in 2007 – to their yearbook Koulu ja menneisyys (School and Past).Footnote37

Nevertheless, the 1980s saw clear developments towards a history of education primarily based on higher education institutions. The field also became increasingly coordinated, especially during the 2000s. The basic condition for these developments was the massive expansion of higher education in Nordic countries starting in the 1960s. In line with the Nordic welfare state model, marked by policies intended to reduce inequalities and increase opportunities for all citizens, higher education institutions expanded so that between 40% and 50% of all 30-year-olds either participated in, or had attended higher education in the early 2000s.Footnote38 In Sweden, the number of students at universities and other higher education institutions rose from 14,000 in 1945 to 340,000 in 2004.Footnote39

In this context of massified higher education, the disciplines of education and history became the main hubs for educational history. At this point, the history of education became written by educational researchers (education, didactics, educational work, sociology of education) and historians (historians, economic historians, historians of ideas). The composition of this multidisciplinary research field of education and history was indicated by the Nordic conferences in the history of education. At the Nordic Conference in 2006, almost 70% of the participants represented the discipline of education, and 24% were from historical sciences such as history, the history of ideas and economic history. At the Nordic conference in 2009, 75% of the participants represented either education or history, with only slightly higher participation from educationalists. Other disciplines included aesthetics, religious studies, war studies, sociology and rhetoric.Footnote40

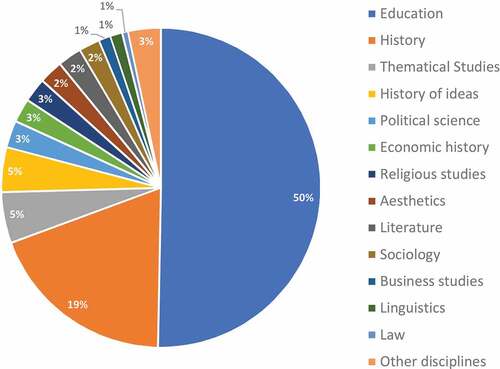

This interdisciplinary feature of the Nordic field was reflected in the research at Swedish universities. My survey of 330 dissertations addressing the history of education from 1980 to 2020 indicates that the disciplines of education (education, didactics, educational work, sociology of education) produced approximately half of the dissertations, followed by the historical disciplines (history, history of ideas, economic history) that together provided 26% of the dissertations (). Although education was the main discipline, producing about half the dissertations throughout the whole period, the role of other disciplines was subject to some fluctuation. For example, the discipline of history increased its share of dissertations from 11% in the 1990s, to 17% in the 2000s, to 28% in the 2010s. Other disciplines saw specific peaks in their production in the 1990s, when religious studies and history of ideas each produced 8% of the dissertations.Footnote41

Figure 1. Dissertations published in Sweden, 1980–2020.

This multidisciplinary research field, with an emphasis on the disciplines of education and history, was marked by two intertwined tendencies in the 2000s: increased coordination, and an expansion that was particularly strong at Swedish universities. Here, the history of education had remained marginal during the 1980s and 1990s. In 1980, only three of Sweden’s 10 departments of education featured research projects addressing the history of education.Footnote42 At Uppsala University, the share of dissertations in education dealing with historical phenomena remained small. Between 1980 and 1991, only one in 10 dissertations dealt with this topic. In 1991, there was certainly some truth to Donald Broady’s claim that the history of education was neglected.Footnote43

The situation was similar in the other Nordic countries. Only 9% of master’s theses and dissertations had historical content at the Department of Education in Oslo in the 1980s. In Finland, the share of dissertations that explored the history of education remained approximately 8% to 9% (on a decade-by-decade basis) from 1970 to 1999.Footnote44 In Norway, only a few of 66 registered PhD theses in education were historical projects in 1991.Footnote45 There were various causes for this precarious situation. In Denmark, the challenges that the paradigm of evidence-based research posed for historians of education was noted.Footnote46 In Norway, the marginalisation of the field has been linked to the stress placed on so-called ‘useful’ research and the growth of new subdisciplines, including special education and school development.Footnote47 In 1990, the Academy of Finland criticised the quality of educational history for being too descriptive.Footnote48

However, the field was revitalised during the 2000s. The most important developments took place in Sweden. The number of dissertations in the history of education almost doubled, from 115 in 1980–1999 to 215 in 2000–2019, and the number of active senior researchers increased. Apart from permanent positions as senior lecturers with an emphasis on educational history, full professors conducting research in educational history were appointed during the 2000s at the universities of Dalarna, Umeå, Mid-Sweden, Uppsala, Stockholm, Örebro, Karlstad and Linköping.Footnote49 These professorships currently form the basis of the main hubs of the history of education in Sweden.

The Nordic conferences in the history of education, with between 100 and 190 participants, provide an indication of the relative importance of the Swedish research field.Footnote50 When organised in Sweden, approximately 80% of the participants at the 2006, 2009 and 2015 conferences were employed at Swedish universities, with the remaining participants split evenly between Denmark, Finland and Norway. Although this distribution certainly depended on the location of the conference, it also reflected the state of the research field. While noting the few participants from Denmark in 2009, Ning de Coninck-Smith claimed that almost all Danish researchers attended the conference.Footnote51 In 2014, Harald Thuen argued that the number of educational historians from Norway could only be counted on one hand, not including PhD students.Footnote52

The relative size of the Swedish research field was further indicated at the Seventh Nordic Educational History Conference in Trondheim, Norway, in 2018. Although the site of the conference and an increasing Norwegian interest in the field meant that 47% of the participants were working in Norway, 38% of the participants were registered at a Swedish university. The remaining 15% were evenly split among Denmark, Finland, and other European countries. As in 2015, Iceland was represented by only one participant at the 2018 conference.Footnote53 At the ISCHE 42 conference, which was organised in Sweden 2021 but held online, the relative strength of the Swedish setting remained evident. Out of 78 Nordic participants, 62% worked in Sweden, 22% in Norway, 8% in Denmark, and 6% in Finland. Once again, there was only one participant from Iceland.Footnote54

Apart from the relative size of the higher education field in Sweden – with 431,100 students enrolled in tertiary education in 2018 compared to 310,900 in Denmark, around 290,000 students in Finland and Norway, and 17,800 in Iceland – the expansion of the Swedish research field was due to a set of comparatively favourable institutional conditions.Footnote55 Some of these were already in place in the 1970s. These included a qualitative turn in educational research, away from educational psychology and quantitative methods, and towards a new sociology of education, informed by the likes of Durkheim, Bourdieu, Bernstein and Althusser. As a result, the field of education remained open for historical methods. Higher education was also transformed by the 1977 reform, which placed teacher training at higher education institutions, providing educational history with a broad institutional setting.Footnote56

There were also more immediate causes for the growth of the Swedish educational history research field. In 2001, the Swedish Research Council (Vetenskapsrådet) established a Committee for Educational Sciences, which included the history of education as one of its sub-fields.Footnote57 In contrast to the Research Council of Norway (Norges forskningsråd), the Swedish Research Council was relatively supportive of educational history. In addition to funding projects, postdoctoral students, and (initially) assistant professorships, the Swedish Research Council funded three graduate schools that have made fundamental contributions: the national graduate school in the history of education (Uppsala University, 2005–2011), the graduate school in historical media (Umeå University, 2011–2015), and the graduate school in applied history of education (Örebro, 2020–2025). In a research overview published by the Swedish Research Council in 2015, the history of education was indeed recognised as a central field in the educational sciences (utbildningsvetenskap).Footnote58

In Sweden, the history of education also became a required part of teacher training, via the teacher training reform of 2011. The government report, in preparing this reform, noted that historical perspectives prepare teachers for the future, provide them with an ability to understand the importance of context, and create an open, critical reflective attitude. More specifically, the report stated that future teachers should know why compulsory and comprehensive schooling was introduced. Furthermore, all teachers should be familiar with the history of early childhood care and education, reading instruction, and the history of grading.Footnote59 As a result of the reform in 2011, university departments were able to employ lecturers with such a focus. In some instances, this was also indicated by the title. Two senior lectures in the history of education were employed at Uppsala University in 2012, and a total of five senior lecturers in education, with an emphasis on the history of education, were employed at Stockholm University from 2014 to 2017.Footnote60

This expansion enabled Swedish universities to take on a leading role in organising and coordinating the field. Nordic conferences in the history of education were organised in Sweden, starting in 1998. The seventh Nordic conference, held in Trondheim, Norway in 2018, was the first to be organised outside of Sweden. In 2005, the Nordic network of the history of education was created at Uppsala University. The Nordic network distributes monthly newsletters and has coordinated the Nordic conferences since 2009. In 2014, the first issue of the Nordic Journal of Educational History was published at Umeå University. In 2015, the first international PhD workshop of the Nordic network was organised at Uppsala University. As these efforts indicate, the multidisciplinary field of educational history in the Nordic countries has engaged with a process of solidification that features both increasing interaction between researchers in the field and long-lasting patterns of cooperation, including between research groups in Sweden.

The disciplinary range of the main Nordic research environments

In this multidisciplinary research field, marked by an expansion at Swedish universities and an increased coordination and interaction between research groups, no significant attempts were made to establish a discipline of the history of education.Footnote61 Instead, the Nordic journal, the conferences, and the network have emphasised, and even celebrated, the inclusiveness of the field. As the organisers of the Seventh Nordic Educational History Conference noted, the history of education in 2018 was ‘an interdisciplinary research field that includes researchers from various academic disciplines and has a broad thematic scope’.Footnote62

This disciplinary range of Nordic history of education and its institutional context is evident from its most significant research environments. These are cohesive research environments that have produced significant numbers of dissertations during the last 10 years and had a certain national or international impact. They provide good examples of how varying institutional contexts have affected the research in the history of education and how it is conceptualised. From a European perspective it is noticeable that the philosophy of education is not a prominent partner to the history of education in these settings. Instead, the history of education is combined with education, history education, sociology of education, child studies and educational policy.

The most influential research environment in the Nordic countries over the last two decades is located at Umeå University (Sweden). Umeå was the host of ISCHE 28 in 2006, and the Nordic conference on the history of education in 2012. Historians of education in Umeå organise the Nordic Journal of Educational History, and, in total, 11 dissertations on the history of education have been published there from 2010 to 2019. This research environment is an excellent illustration of the role of teacher training programmes, the Swedish Research Council, and the discipline of history in revitalising Nordic educational history. In 2004, Daniel Lindmark was appointed professor in history, with a focus on teacher training and professional educational work. Although the history of education has a rich background at Umeå University, including the ground-breaking research on literacy by Egil Johansson, Lindmark's appointment marked the start of an incredible expansion of research. Projects were funded by the Committee for Educational Sciences at the Swedish Research Council, and co-funded by the Umeå School of Education.Footnote63

A marked feature of this research group, named History and Education, is that it includes both the history of education and history education, which finds common ground in the history of history education. Recent project topics include the history of textbook production, the Swedish school yard, the educational history of the indigenous Sámi population, and the academic discipline of education. The research group is led by Daniel Lindmark (professor of history and education, and church history) and Anna Larsson (professor of history of science and ideas, with a focus on educational research).Footnote64 Their leadership illustrates the interdisciplinary interface of educational history at Umeå University.

The impact of teacher training programmes and the policies of the Swedish Research Council is also evident at Uppsala University, where the disciplines of history and sociology of education formed the main pillars for the history of education research. In the Department of History, research into social history, nationalism, and popular movements produced 11 dissertations addressing the history of education and childhood from 2000 to 2009. In the teacher training department, Donald Broady was appointed professor in 1997, where he established a research group named Sociology of Education and Culture (SEC). In addition to the above-mentioned graduate school in the history of education (2005 to 2011), SEC organised two Nordic conferences on the history of education (2009; 2015). In 2008, several historians, educationalists and PhD students formed a research group on the social and economic history of education, within the sociology of education group. This group was later renamed SHED (Uppsala Studies of History and Education). Between 2008 and 2018, this group produced eight dissertations.Footnote65

With one foot in the discipline of history, as well as PhD students in the discipline of sociology of education, SHED has promoted research that analyses education in the context of social and economic factors. In the 2010s, externally funded research projects addressed the history of social class and monitorial education; the funding of primary schooling and popular education; school mathematics reforms; and the marketisation of early childhood care and education.Footnote66 Being closely linked to sociology of education, the history of education has received a comparatively independent position, in which projects tend to be motivated by their relevance within the field of educational history, rather than to a wider field of educational history or present-day concerns. This independence is marked by the fact that four senior lecturer positions in the history of education were created in the period 2008–2021. Furthermore, the research group is presently led by Esbjörn Larsson, the only academic in the Nordic countries with the title of Professor in the History of Education.

At Stockholm University, the history of education has mainly been conducted in the Department of Education, where the research group in history and sociology of education created a seminar on the history of education in 2009. Residing within the framework of the discipline of education has set this research group further apart from history education and the French tradition of sociology of education, compared with the two research groups mentioned above. Instead, the choice of research topics and theoretical frameworks are more closely linked to educational research, with an emphasis on educational policy, international processes, and knowledge production. Recent research projects include the education of scientific elites during the Cold War, the student movement and school democracy, and the history of the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). A striking feature of this research environment is the appointment of several historians of ideas in response to the teacher training reform of 2011. This research group is led by Joakim Landahl, who is a professor in education with an emphasis on the history of education. His academic title is a fitting illustration of the disciplinary setting of this research environment.

A fourth base for history of education in the Nordics is located at Linköping University. Founded in 1975, Linköping University is, like the universities in Umeå and Stockholm, part of the post-war expansion of higher education in Sweden. The history of education found a home within the Department of Thematic Studies – Child Studies (tema Barn), created in 1988. This interdisciplinary research group focuses on theoretical and empirical studies of children, and the social and cultural discourses that surround them.Footnote67 From the start, this research group was led by Karin Aronsson, a social interactionist scholar, and Bengt Sandin, a trained historian. These leaders gave the department a certain emphasis on historical perspectives. Due to its specific thematic emphasis on children, the department did not specialise on the institutional settings of school, but a wide range of contexts, including institutions such as arbetsstugor (child workhouses, a precursor to after-school care), skollovskolonier (summer camps), and child guidance clinics (rådgivningsbyråer).Footnote68 The interdisciplinary setting of the Child Studies unit, of which the historical dimension is a vital part, is currently led by four professors from different disciplinary backgrounds, including the psychologist and child studies scholar Karin Zetterqvist Nelson and the economic historian Johanna Sköld.

In Denmark, Norway and Finland, research in educational history remained comparatively scattered across higher education institutions in the 2010s. In Finland, research into the history of education is conducted in the Department of History and Ethnology at the University of Jyväskylä, and the Department of Education at the University of Turku. In Norway, reliance on individual researchers (rather than research groups) has been a main feature of the field.Footnote69 However, important work has been carried out within the focused area of research into educational media and didactics, at the Institute for Education and Lifelong Learning at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Trondheim, the Department of Education at the University of Oslo, and at the University of South-Eastern Norway. The significant number of Norwegian participants at recent Nordic conferences and at ISCHE 42, together with the creation of a Norwegian network of historians of education in 2022, also bodes well for the future development of the field in Norway.

In Denmark, the history of education has seen a range of institutional changes during the last 30 years. In 1992, the Institute for Danish School History was closed. After a series of reorganisations, the history of education found a home at Aarhus University, which merged with the Danish School of Education in 2007.Footnote70 Here, courses were taught at the bachelor’s level and several major book projects were finalised. These include Ning de Coninck-Smith and Charlotte Appel’s five volumes on Danish school history, but also edited books on the history of educational ideas and the history of early childhood care and education.Footnote71

Currently, the major hub of educational research in Denmark is the Centre for Education Policy Research, at Aalborg University. Unlike many of the Swedish research environments, it is not directly linked to a department of education or to teacher training programmes. Instead, it approaches educational policy from interdisciplinary perspectives, under the leadership of Mette Buchardt. Although it often employs historical perspectives, the group addresses contemporary societal challenges, such as equality, social cohesion and citizenship. This orientation towards contemporary educational issues is, for example, illustrated by Christian Ydesen’s project The Global History of the OECD in Education.Footnote72 As a leading research environment in the Nordic countries, this group hosted the Eighth Nordic Educational History Conference in 2022. Consequently, Aalborg is not only an indication of the disciplinary range of the history of education in the Nordic countries, but also provides insights into how the Nordic field became increasingly coordinated during the 2000s.

Following international trends

As in other parts of the world, the thematic and theoretical scope of this expanding multidisciplinary field in the Nordic countries widened from the 1980s to include a wide range of perspectives and topics. In Denmark, the history of women, childhood, literacy and disability enriched the field. To capture this development, the traditional term school history (skolehistorie) was gradually replaced with the term history of education (utdannelseshistorie).Footnote73 Similar developments can be seen in the other Nordic countries. Responding to developments in sociology and history, the history of education in Finland featured an increasing diversity of topics based on women’s studies, psychohistory, everyday history and the history of mentalities. One result was an increased emphasis on studies from below, which took the perspective of those individuals participating in the education process.Footnote74 In Norway, the period starting in the 1980s was named after the educationalist and historian of education Alfred Oftedal Telhaug. This denotation stresses the widening of thematic and theoretical research interests to include not only educational institutions and systems, but also the history of school subjects and curriculum, teaching professions, special education, and children and childhood.Footnote75

Nevertheless, this diverse setting has been marked by certain trends. Some of these matched the increasing preference in Europe and the Anglo-Saxon world for the new cultural history of education, which addressed postmodern currents and the linguistic turn by exploring entanglements of discourses and realities.Footnote76 Drawing on the cultural turn in history – examining cultural artefacts, discourses, experiences and practices in all aspects of human culture – the history of education saw an increasing interest in everyday experiences, educational practices, and the sensory and visual history of education, in which discourses, cultural categories and theoretical frameworks are placed in the centre.Footnote77

In the Nordics, the impact of this cultural turn was indicated by significant efforts into studies of everyday life and the material culture and sensory history of education, addressing what has been called the black box of schooling.Footnote78 Ning de Coninck-Smith was an early promoter of such research, including her pioneering work on school detention. She has thereafter made several fundamental contributions to the field of research, including the five-volume study of Danish school history mentioned above. Instead of a from-above account of schooling over 500 years, this project placed the practices and experiences of schooling in focus, exploring everyday school life and what it meant to pupils, parents and teachers.Footnote79

Apart from this magnum opus, there are several other important studies in a similar research vein. These include a range of publications on school memories, everyday discipline, and the design and lived experiences of school buildings and yards. Specific topics include school prisons, hallways, preschool naps and preschool design.Footnote80 Esbjörn Larsson’s landmark dissertation on hazing and youth culture at the Swedish Royal War Academy was followed by several books addressing similar issues in the everyday life of educational institutions, including secondary schools, boarding schools and summer camps.Footnote81 An excellent example of this research strand is the special issue on education and violence in the Nordic Journal of Educational History. It includes articles on corporal punishment in secondary schools in Finland, reports of violence in Swedish scouting camps, and changing attitudes towards physical punishment in Norway during the latter half of the nineteenth century.Footnote82

The trend towards studies of international and transnational phenomena also made a significant impression on the Nordic countries. Despite an increased interest in the international field of the history of education from the 1990s onwards, such research remained scarce in the Nordic countries until the early 2000s.Footnote83 More recently, a wealth of studies has been published on this topic. Some studies have compared education in different countries, such as Susanne Wiborg’s research on comprehensive schooling in Europe.Footnote84 Others have focused on international events (world fairs and educational exhibitions), the transfer of educational ideas, and the use of international arguments in policy-making.Footnote85 Notable contributions include those on international organisations such as the OECD and UNESCO, and on the history of the PISA rankings.Footnote86 Vital contributions also include historical and economic history studies on cultural transfer, academic mobility, and the migration of Swedish engineers.Footnote87

As elsewhere, the Nordic countries have seen an increased research interest into the educational history of ethnic minorities.Footnote88 This research has addressed the Sámi people, historically located in the northern regions of Sweden, Norway, Finland, and Russia. Other research has focused on the Romani population, Swedish Finns, the Tornedalers and Meänkieli (Torne Valley Finnish), the Kven (a Finnish-speaking population in northern Norway), the Greenlanders, and various immigrant groups.Footnote89 Important pioneering work on the education of the Sámi people includes early publications in Finland, as part of the Saami movement in the 1970s. Einar Niemi’s and Knut Einar Eriksen’s landmark publication on minority policy in northern Norway is also fundamental for this research field.Footnote90 In Sweden, two traditions of research have remained important: studies addressing the early modern period and the so-called Lapp-schools of the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, and the research exploring the so-called nomad schools of the early twentieth century.Footnote91

In certain respects, research on Sámi educational history followed the general development of Nordic educational history, wherein the scope has widened to include not only educational policy and organisation, but also international comparisons, postcolonial perspectives, and the Sámi experiences of schooling.Footnote92 As such, this field encompasses both the six-volume series Sami School History: Articles and Memories, addressing the so-called Norwegianisation of the Sámi, and research that more explicitly attempts to place Sámi educational history within an international context.Footnote93

A specific Nordic flavor?

While certainly taking part in international trends, the history of education in the Nordic countries also has features stemming from the Nordic context. This Nordic context concerns certain topics mentioned above. These include the early modern literacy campaign and the Lutheran heritage; specific Nordic ethnic minorities; the results of post-war developments, including the expansion of early childhood care and education programmes; the launch of comprehensive school systems; and more recent marketisation reforms.

A particular Nordic flavour is also created by certain theoretical frameworks and approaches that draw upon the field’s reliance on the disciplines of education and history, and the varying links to studies in history education, the sociology of education and educational policy presented above. One striking feature of Nordic history of education is the significance of Swedish curriculum theory in Sweden, Norway and Finland.Footnote94 Closely related to the work of Basil Bernstein, Ulf P. Lundgren defined curriculum research as ‘an attempt to produce knowledge of how the goals, content, and methodology of educational processes are shaped in a certain society and a certain culture’.Footnote95 In influential publications, Lundgren and Tomas Englund used the concept of curriculum code to denote the basic principles of these processes, distinguishing between classical, realistic and moral curriculum codes.Footnote96

The impact of curriculum theory in the Nordics is difficult to overestimate. It has been applied to topics ranging from early modern rhetoric education and nineteenth-century school inspections, to early twentieth-century kindergarten and early twenty-first-century teacher-training reform.Footnote97 In particular, Swedish curriculum theory has guided research on textbooks and educational policy. In such studies, it was used both to analyse classroom practices and the content of educational media, and the negotiation, formulation, and implementation of educational policy.Footnote98 Here, the theory provides a flexible theoretical foundation for researchers to use Peter Berger and Thomas Luckman’s sociology of knowledge to analyse assessment, Mary Douglas’ concept of thought styles to explore teacher-training policies, and critical discourse analysis to explore the content of textbooks.Footnote99

Nordic research is also marked by an interest in the history of history education and the uses of history. This strand of research is strongest in Sweden, mainly due to the Swedish Research Council’s funding of four graduate schools exploring history education (historiedidaktik) from 2007 to 2014.Footnote100 Here, important concepts include historical consciousness (historiemedvetande), the uses of history (historiebruk), and historical culture.Footnote101 Several important works have dealt with the production and use of history textbooks. These include Cold War portrayals of the USA and the Soviet Union, changing expressions of historical consciousness during the twentieth century, national historical narratives produced by study associations, and history textbook revisions.Footnote102

Such studies addressing history education have led to a widened interest in our representations of the past and its social and political context. For example, Sirkka Ahonen has studied the post-conflict history of education in Finland, South Africa and Bosnia-Herzegovina, and Harry Haue researched the development of history education in the former Danish colony of Greenland.Footnote103 Pioneering work has also been accomplished at Umeå University, where the ties between research into the history of education and history education are particularly strong. Here, expertise in the history of the Sámi population and the uses of history resulted in The Church of Sweden and the Sami – A White Paper Project (2012 to 2017), led by Daniel Lindmark. In relation to this massive project, further examinations into the complex issues of historical justice and reconciliation have ensued.Footnote104

Apart from curriculum theory and history education, research on the social and economic history of education, stressing the social and economic context of education, remains an important feature of the Nordic history of education. Such research has made important contributions to our understanding of the teaching profession, including studies of the social and demographic characteristics of primary school teachers in Iceland; the socioeconomic background of teachers in northern Sweden; and career trajectories in Swedish higher education.Footnote105 Studies emphasising the social context of schooling also include those examining eighteenth-century rural schools in Norway; nineteenth-century rural lending libraries in Finland; and private teachers in Sweden. Indicating their distance from the new cultural history of education, these studies instead gather their theoretical inspiration from Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of capital; Robert Merton’s principle of cumulative advantage; Jan de Vries’ concept of industrious revolution; and Robert Darnton’s concept of the communication circuit.Footnote106

A striking example of research addressing the social and economic context of education is the increasing number of studies addressing the history of educational finance. As Marcelo Caruso has noted, educational research has a tendency to keep economic issues out of the analysis, since it either appears foreign to the ethos of education or because of a general trend to distance schooling from its external conditions.Footnote107 However, historians of education in Sweden have shown increasing interest in the finance of early modern popular education, nineteenth-century primary schooling, monitorial schools, private schools, adult education and academic exchange.Footnote108 Economic historians have also made strikingly original contributions by examining education against the background of economic development. In this respect, Lund University has a strong tradition of studies of literacy, human capital and vocational education.Footnote109 Recent contributions on literacy, inequality, and social mobility include those of Francisco J. Beltrán Tapia at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology in Trondheim; Sakari Saaritsa on health, education and inequality, at the University of Helsinki; and Nicholas Ford et al. on Danish students’ grades and the accumulation of human capital, at Lund University and the University of Southern Denmark.Footnote110 Such studies add flavour to the field, and creates further opportunities for future research, which I will discuss in more detail below.

Future

The main argument of this article is that the history of education in the Nordic countries has developed in accordance with its institutions. In the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, history of education was written by schoolmen for schoolmen. As a result, celebratory accounts of progress and landmark events flourished. In the post-war era, the discipline of education took increasing responsibility for the field. Although restricted in terms of the number of publications, the history of education had a golden age in terms of relative output. It is indicative that approximately one-third of the dissertations in the major departments of education were historical. During this period, marked by the introduction of comprehensive schooling and researchers’ involvement in school politics, the main perspective was from above, emphasising school politics and legislation.

From the 1980s onwards, a multidisciplinary research field emerged. Enabled by the massification of higher education, it gained foothold at young universities such as Stockholm University (1960), Umeå University (1965), the University of Jyväskylä (1966) and Linköping University (1975). The focus of research varied, depending upon the alignment of the history of education to history education (Umeå), sociology of education (Uppsala) or educational policy (Aalborg). As research was conducted mainly by educationalists and historians, this influenced the choice of topics and theoretical frameworks. Nordic history of education can therefore currently be best described as written by, and for, educational researchers and historians. As a result, the topics and theoretical perspectives of Nordic history of education are not only borrowed from the international field of educational history, but also from the disciplines of education and history in the Nordics. Examples of the latter are the importance of social history and Swedish curriculum theory in the Nordic history of education.

Due to favourable conditions – particularly in Sweden – the Nordic history of education currently stands stronger now than it did 20 or 30 years ago, in terms of active research environments, output and coordination. It is well represented by full professors and senior lecturers; has a strong organisation via conferences, PhD workshops, graduate schools, and the Nordic Journal of Educational History; and addresses a wide range of questions, using a generous selection of theoretical frameworks. Recent efforts to compile comprehensive, general overviews of the history of education in the Nordic countries indicate the field’s strength.Footnote111 Although it might have felt proper to ask if the history of education had been forgotten in the early 1980s, that question consequently no longer makes sense.

Based on this analysis of Nordic history of education, the field offers strengths to be applied, opportunities to be exploited, and weaknesses to be addressed. Provided that education continues to offer a disciplinary basis, historical studies of educational policy and textbooks will remain in demand. Here, many research questions have yet to be answered. Compared to the interest shown in the new cultural history of education, the paradoxes of educationalisation remain rather unexplored in the Nordic setting, and the progressive movement remains scarcely researched.Footnote112 As elsewhere, the role of religion has remained mostly neglected, not least in twentieth-century education policy.Footnote113 Here, further studies of both the subject of religion in schools, as well as the role of religious languages in educational policy could be particularly valuable.Footnote114

The important role of historians and economic historians in the Nordic history of education provides ample opportunities to explore the social and economic context of education, a direction also supported by researchers working in the sociology of education. Here, the economic history of education certainly offers great potential to bridge the gap between education and society, not the least by investigating local and regional heterogeneity in educational experiences, and its basis in inequality, democracy, religion and central government policies. The Nordic countries benefit from a strong tradition of research into literacy, and given the increasing importance of human capital studies in leading economic history journals, one should expect important work to be done in this field not the least at the universities of Lund, Helsinki and Trondheim.Footnote115

The history of education’s foothold in the discipline of history offers further potential in the growing Nordic research in the history of knowledge, which has its main hub in the Lund Centre for the History of Knowledge.Footnote116 Addressing ‘the social production and circulation of knowledge’, using the definition of Philipp Sarasin, the history of knowledge certainly has the scope to shed light on the history of education. This can be achieved by its emphasis on the broader social, cultural and political context of knowledge, which tends to be neglected in educational history focused on the narrower educational context of the content of education. Recent publications in the fields of the history of knowledge and the history of education indicate the promise of further cooperation.Footnote117

The field of the history of education also has major challenges to address. First: in the context of academia where digitisation and the creation of digital infrastructure and databases are important trends, it is noticeable that Nordic history of education still lacks extensive databases and digitisation projects that can help answer fundamental large-scale questions regarding the historical development of education.Footnote118 Although some source materials have been digitised in recent years, including those collected by the Danish School Museum and the parliamentary records of the Swedish parliament, the potential of such projects remains largely unexplored.Footnote119

Second, and perhaps most importantly, Nordic history of education faces a fundamental challenge to develop its relevance for, and contribution to, adjacent scientific and political fields. Although the history of education has value in and of itself, it cannot prosper if it is not relevant, meaningful or useful for others. In this respect, Nordic history of education has served political functions in the past. In relation to the political struggles of educators and teachers, celebratory accounts of the history of legislation, institutions, or individuals appeared important and meaningful in late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, while educational reforms of the post-war era sparked an interest in the historical background of these reforms among both educationalists and policymakers.

There are, nevertheless, strands of research in the Nordic countries that explore the potential of new rationales, making it relevant for public debate and policy. At Child Studies in Linköping University, Johanna Sköld has examined child abuse in institutional settings from a historical perspective, which is certainly relevant in the context of the government-funded inquiries into child abuse.Footnote120 At Umeå University, historians of education have explored the relationship between the state, the church and the Sámi people, which is a politically charged issue.Footnote121 Although the Centre for Education Policy Research at Aalborg University does apply historical perspectives, its focus nevertheless lies on contributing to current societal challenges, such as inequality, diversity and social cohesion. In this context, the graduate school in applied history of education, funding nine PhD positions in Örebro, Stockholm, Uppsala and Umeå, provides a final example of explorations into the rationales of the history of education.Footnote122 Here, the focus is on research that sheds new light on issues of immediate relevance to contemporary debate. Although these PhD projects will not provide a simple answer to the rationale of educational history in the Nordic countries, they will allow us to reflect further on the question of why the history of education still matters in the twenty-first century.

Acknowledgement

The author wishes to thank the anonymous reviewers and the following colleagues for generous comments, information, assistance, or helpful suggestions: Annika Ullman, Christian Ydesen, Daniel Lindmark, Donald Broady, Esbjörn Larsson, Jesper Eckhardt Larsen, Joakim Landahl, Johanna Sköld, Mette Buchardt, Nina Volckmar, Tomas Englund and Ulla Riis.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Johannes Westberg

Johannes Westberg is full professor of theory and history of education, University of Groningen, the Netherlands. He has organised the Nordic network on history of education since 2008, was the initiator of the Nordic PhD Workshops in the Histories of Education, has organised and co-organised two Nordic conferences on the history of education, and is member of the editorial team of the Nordic Journal of Educational History. He is the scientific leader of the graduate school in applied history of education, and his recent publications include the monograph Funding the Rise of Mass Schooling (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), and the edited book (with Lukas Boser and Ingrid Brühwiler) School Acts and the Rise of Mass Schooling (Palgrave Macmillan, 2019).

Notes

1 Gunnar Richardson, ‘Är pedagogikhistorien bortglömd?’, Tvärsnitt: Humanistisk och samhällsvetenskaplig forskning 2, no. 3 (1980): 34–48.

2 Donald Broady, ‘Presentation av Forum för pedagogisk historia’, Meddelanden från Forum för pedagogisk historia 1, no. 1 (1991): 5–6; Alfred Oftedal Telhaug, ‘Forty Years of Norwegian Research in the History of Education’, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 41, no. 3–4 (1997): 347–8; Jukka Rantala, ‘History of Education Threatened by Extinction in Finnish Educational Sciences’, in Knowledge, Politics and the History of Education, ed. Jesper Eckhardt Larsen (Berlin: LIT Verlag, 2012), 55.

3 The Nordic countries are Denmark, Finland, Iceland, Norway and Sweden, and their autonomous countries, regions and dependencies. The latter include the Faroe Islands, Greenland and the Åland Islands.

4 Daniel Lindmark, ‘Educational History in the Nordic Region: Reflections from a Swedish Perspective’, Espacio, Tiempo y Educación 2, no. 2 (2015): 19.

5 Ibid., 9; Björn Norlin and David Sjögren, ‘Enhancing the Infrastructure of Research on the Nordic Educational Past: The Nordic Journal of Educational History’, Nordic Journal of Educational History 1, no. 1 (2014): 1–5; Henrik Åström Elmersjö, ‘Between Nordism and Nationalism: The Methods of the Norden Associations’ Educational Efforts, 1919–1965’, Nordic Journal of Educational History 7, no. 2 (2020): 31–49.

6 See Ministerrådet Nordiska and sekretariat Nordisk Ministerråd, Nordic Statistical Yearbook 2014: Nordisk Statistisk Årsbok 2014 (Nordiska Ministerrådet, 2014).

7 Alfred Oftedal Telhaug, ‘Norsk skolehistorisk forskning – fire generasjoner’, in Både – og: 90-tallets utdanningsreformer i historisk perspektiv, eds. Alfred Oftedal Telhaug and Petter Assen (Oslo: Cappelen akademisk forlag, 1999), 177–99.

8 Christian Larsen and Jesper Eckhardt Larsen, ‘Between ”Freight-Shippers” and Nordists – the Political Implications of Educational Historiography in Denmark’, in Larsen, Knowledge, Politics and the History of Education, 226; Tomas Englund, ‘Pedagogisk historieforskning och utbildningshistoria – en introduktion’, in Politik och socialisation: Nyare strömningar i pedagogikhistorisk forskning, ed. Tomas Englund (Uppsala: Uppsala universitet, 1990), 1–2.

9 Rantala, ‘History of Education Threatened’, 65.

10 Petter Aasen, ‘Arven etter Alfred’, Norsk pedagogisk tidskrift 100, no. 4 (2017): 347.

11 For an account of traditional history of education, see, e.g. Matthew Gardner Kelly, ‘The Mythology of Schooling: The Historiography of American and European Education in Comparative Perspective’, Paedagogica Historica 50, no. 6 (2014): 3–5.

12 Regarding the so-called ‘person-historical-research paradigm’ in Finland, see Håkan Andersson, ‘History of Education in Post-War Educational Research in Finland: Some Trends and Problems’, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 41, no. 3–4 (1997): 334–35.

13 Marc Depaepe, ‘The Ten Commandments of Good Practices in History of Education Research’, Zeitschrift für pädagogische Historiographie 16 (2010): 31; Gary McCulloch, The Struggle for the History of Education (London: Routledge, 2011), 11–12.

14 Esbjörn Larsson, ‘On the Use and Abuse of History of Education: Different Uses of Educational History in Sweden’, in Eckhardt Larsen, Knowledge, Politics and the History of Education, 110.

15 Christian Larsen, ‘Institutter, selskaber, museer og foreninger: den institutionelle skolehistorie 1965–2016’, Uddannelseshistorie 50 (2016): 18.

16 Larsson, ‘On the Use and Abuse of History of Education’, 112. The national associations in Finland also emphasised the importance of preserving the past: see Gösta Cavonius, ‘De skolhistoriska föreningarnas verksamhet i Finland’, Årbog for Dansk Skolehistorie 2 (1968): 28.

17 Vagn Skovgaard-Petersen, ‘Forty Years of Research into the History of Education in Denmark’, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 41, no. 3–4 (1997): 321. Larsen’s three volumes were published 1893–1916.

18 Telhaug, ‘Norsk skolehistorisk forskning’, 180–1.

19 Viktor Fredriksson, ed., Svenska folkskolans historia: d. 1, inledande översikt (Stockholm: Albert Bonniers förlag, 1940), v.

20 Cavonius, ‘De skolhistoriska föreningarnas verksamhet i Finland’, 27–31; Esbjörn Larsson, ‘Nittio år i undervisningshistoriens tjänst: Föreningen för svensk undervisningshistoria 1920–2010’, Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige 15, no. 2/3 (2010): 232–34. For links to the websites of these associations, see www.utbildningshistoria.se (accessed May 7, 2021).

21 Larsson, ‘On the Use and Abuse of History of Education’, 111–12.

22 Regarding the case of Denmark and Sweden, see Roar Skovmand, ‘Skolehistorien – et forsømt område’, Årbog for Dansk Skolehistorie 2, no. 1 (1967): 7–14; and Richardson, ’Är pedagogikhistorien bortglömd?’ 34–48.

23 Ulla Riis, Avhandlingar i pedagogik från Uppsala universitet 1913/1949 t.o.m. okt. 2012. Doktorsavhandlingar, licentiatavhandlingar och licentiatuppsatser. Reviderad elektronisk upplaga 2020-11-19, pedagogisk forskning i Uppsala (Uppsala: Uppsala University, 2020).

24 Skovgaard-Petersen, ‘Forty Years of Research into the History of Education in Denmark’, 323; Lejf Degnbol, ‘Vagn Skovgaard-Petersen og Institut for dansk skolehistorie’, in Institut Selskab Museum: Skolehistorisk hilsen til Vagn Skovgaard-Petersen, eds. Inger Schultz Hansen and Erik Nørr (Copenhagen: Selskabet for Dansk Skolehistorie og Dansk Skolemuseum, 2001), 9–10.

25 Harald Thuen, ‘Ny dansk utdanningshistorie – hva med Norge? Historiografiske refleksjoner’, Årbok for norsk utdanningshistorie 29 (2014): 41.

26 Rantala, ‘History of Education Threatened’, 61; Aldred Oftedal Telhaug, ‘Fra beskrivende til teorioerientert forskning – norsk historisk-pedagogisk forskning/formidling i et historiskt perspektiv’, Årbok for norsk utdanningshistorie 27 (2010), 89; Riis, Avhandlingar i pedagogik från Uppsala universitet.

27 Riis, Avhandlingar i pedagogik från Uppsala universitet, 13–16; Nina Volckmar, Utdanningshistorie: Grunnskolen som samfunnsintegrerende institusjon (Oslo: Gyldendal Akademisk, 2016), 16.

28 Thuen, ‘Ny dansk utdanningshistorie – hva med Norge?’, 41–2; Volckmar, Utdanningshistorie, 15.

29 John Landquist, Pedagogikens historia (Lund: Gleerup, 1941); John Landquist and Torsten Husén, Pedagogikens historia (Lund: Gleerup, 1973).

30 Wilhelm Sjöstrand, Källkritiska problem inom pedagogisk och historisk forskning (Lund: Studentlitteratur, 1972).

31 Telhaug, ‘Forty Years of Norwegian Research in the History of Education’, 351. See also Telhaug, ‘Norsk skolehistorisk forskning’, 187.

32 Regarding the role of school reforms, see Skovgaard-Petersen, ‘Forty Years of Research into the History of Education in Denmark’, 326–7; and Andersson, ‘History of Education in Post-War Educational Research in Finland’, 336–7.

33 Roar Skovmand, https://biografiskleksikon.lex.dk/Roar_Skovmand (accessed May 13, 2021).

34 Urho Somerkivi, Kuka kukin on (Aikalaiskirja): Who’s who in Finland (Helsinki: Otava), 925.

35 Lars Petterson, ‘Pedagogik och historia: en komplicerad förbindelse’, in Kobran, Nallen och Majjen: Tradition och förnyelse i svensk skola och skolforskning, ed. Staffan Selander (Stockholm: Myndigheten för skolutveckling, 2003), 360.

36 Åke Isling, Kampen för och mot en demokratisk skola del 1. Samhällsstruktur och skolorganisation (Stockholm: Sober förlag, 1980); Åke Isling, Det Pedagogiska arvet: kampen för och mot en demokratisk skola del 2 (Stockholm: Sober förlag, 1988).

37 Suomen kasvatuksen ja koulutuksen historian seura, https://www.kasvhistseura.fi/etusivu (accessed May 7, 2021).

38 Jens-Peter Thomsen, et al., ‘Higher Education Participation in the Nordic Countries 1985–2010: A Comparative Perspective’, European Sociological Review 33, no. 1 (2016): 100.

39 Högskoleverket, Högre utbildning och forskning 1945–2005: En översikt (Stockholm: Högskoleverket, 2006), 16.

40 Donald Broady et al., ‘Utbildningens sociala och kulturella historia: en översikt’, in Utbildningens sociala och kulturella historia: meddelanden från den fjärde nordiska utbildningshistoriska konferensen, eds. Esbjörn Larsson and Johannes Westberg (Uppsala: Forskningsgruppen för utbildnings – och kultursociologi, 2010), 15–16.

42 Richardson, ’Är pedagogikhistorien bortglömd?’ 47.

43 Riis, Avhandlingar i pedagogik från Uppsala universitet; Broady, ‘Presentation av Forum för pedagogisk historia’, 5.

44 Telhaug, ‘Fra beskrivende til teorioerientert forskning’, 89; Rantala, ‘History of Education Threatened’, 60–61.

45 Telhaug, ‘Forty Years of Norwegian Research in the History of Education’, 347.

46 Jesper Eckhardt Larsen, ‘Introduction’, in Eckhardt Larsen, Knowledge, Politics and the History of Education, 11–12.

47 Telhaug, ‘Forty Years of Norwegian Research in the History of Education’, 348–9.

48 Rantala, ‘History of Education Threatened’, 64.

49 See sources for . These professors included: Lars Petterson (2003) Daniel Lindmark (2004), Christian Lundahl (2012), Anne-Li Lindgren (2014), Anna Larsson (2016), Johannes Westberg (2016), Annika Ullman (2017), Esbjörn Larsson (2018), Joakim Landahl (2018), Samuel Edquist (2019), Magnus Hultén (2020), and Johan Samuelsson (2022).

50 https://utbildningshistoria.se/nordiska-konferenser/ (accessed October 12, 2021).

51 Broady et al., ‘Utbildningens sociala och kulturella historia’, 16.

52 Thuen, ‘Ny dansk utdanningshistorie – hva med Norge?’, 37.

53 Broady et al., ‘Utbildningens sociala och kulturella historia: en översikt’, 15–16. Data from the 2015 and 2018 Nordic conferences provided by author.

54 Data in the ownership of the author. ISCHE is the International Standing Conference for the History of Education.

55 Enrollment in tertiary education, all programmes, both sexes (2018), http://data.uis.unesco.org/ (accessed April 9, 2021).

56 Regarding the qualitative turn, see Tomas Englund, ‘New Trends in Swedish Educational Research’, Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 50, no. 4 (2006): 383–96. The role of the Swedish frame factor theory in this turn is discussed in Donald Broady, ‘Det svenska hos ramfaktorteorin’, Pedagogisk forskning i Sverige 4, no. 1 (1999): 111–21.

57 Lindmark, ‘Educational History in the Nordic Region’, 8.

58 Vetenskapsrådet, Forskningens framtid! Ämnesöversikt 2014 Utbildningsvetenskap (Stockholm: Vetenskapsrådet, 2015), 5. Regarding the Norwegian research policy, see Telhaug, ‘Fra Beskrivende Til Teorioerientert Forskning’, 93; and Thuen, ‘Ny dansk utdanningshistorie – hva med Norge?’, 37.

59 SOU [Swedish Government Official Report] 2008: 109, 194.

60 Author’s knowledge and information from Joakim Landahl (Stockholm University) and Esbjörn Larsson (Uppsala University).

61 For a similar conclusion, see Lindmark, ‘Educational History in the Nordic Region’, 7.

62 ‘Welcome to the Seventh Nordic Educational History Conference in Trondheim’, https://www.ntnu.no/nordisk-utdanningshistorie-2018/home (accessed April 16, 2021).

63 Anställningar och uppdrag i korthet, https://www.umu.se/personal/daniel-lindmark/ (accessed May 7, 2021).

64 Historia med utbildningsvetenskaplig inriktning, https://www.umu.se/forskning/grupper/historia-med-utbildningsvetenskaplig-inriktning/ (accessed May 13, 2021).

65 Utbildnings- och kultursociologi (SEC), http://www.skeptron.uu.se/broady/sec/ (accessed May 7, 2021). The first coordinators of the working group were Esbjörn Larsson and Johannes Westberg.

66 Uppsala Studies of History and Education (SHED), https://www.edu.uu.se/forskning/utbildningshistoria/ (accessed May 7, 2021).

67 Bengt Sandin, ‘The Century of the Child’ on the Changed Meaning of Childhood in the Twentieth Century (Linköping: Linköping University, 1995), 22.

68 Ann-Charlotte Münger, Stadens barn på landet: Stockholms sommarlovskolonier och den moderna välfärden (Linköping: Tema, 2000); Ole Olsson, Från arbete till hobby: En studie av pedagogisk filantropi i de svenska arbetsstugorna (Linköping: Tema, 1999); Ulf Jönson, Bråkiga, lösaktiga och nagelbitande barn: om barn och barnproblem vid en rådgivningsbyrå i Stockholm 1933–1950 (Linköping: Tema, 1997).

69 Thuen, ‘Ny dansk utdanningshistorie – hva med Norge?’, 37.

70 Christian Larsen and Jesper Eckhardt Larsen, ‘Mellem nyhumanister, nordister, internationalister og emancipatorer – dansk uddannelseshistorie i små hundrede år’, Uddannelseshistorie 43 (2009), 107; Larsen and Larsen, ‘Between ”Freight-Shippers” and Nordists’, 231–32.

71 Ning de Coninck-Smith and Charlotte Appel, Dansk skolehistorie: dansk skolehistorie bd. 1–5 (Aarhus: Aarhus Universitetsforlag, 2013–15); Jens Erik Kristensen and Søs Bayer, Pædagogprofessionens historie og aktualitet, bind 1 og 2 (Köpenhamn: University Press, 2015); Hans Siggaard Jensen et al., Paedagogikkens idehistorie (Aarhus: Aarhus University Press, 2017).

72 Christian Ydesen, The OECD’s Historical Rise in Education: The Formation of a Global Governing Complex (Cham: Springer International Publishing AG, 2019).

73 Larsen and Eckhardt Larsen, ‘Mellem nyhumanister, nordister, internationalister og emancipatorer’, 103–5.

74 Rantala, ‘History of Education Threatened’, 64–5. Regarding the role of sociology and other disciplines in Finland, see Andersson, ‘History of Education in Post-War Educational Research in Finland’, 338–42. As a result of this process the Suomen Kouluhistoriallinen Seura (Finnish Society for School History) was renamed Suomen kasvatuksen ja koulutuksen historian seura (Finnish Society for the History of Education), https://www.kasvhistseura.fi/etusivu (accessed September 14, 2021).

75 Thuen, ‘Ny dansk utdanningshistorie – hva med Norge?, 42–5; Telhaug, ‘Forty Years of Norwegian Research in the History of Education’, 350–4.

76 McCulloch, The Struggle for the History of Education, 6–7.