ABSTRACT

The accredited secondary school enrolment system, which originated from the certificate enrolment system of American universities in the 1870s, was the main enrolment method of Christian universities in modern China. This study mainly uses methods of literature and comparison. It focuses on the design and implementation of the system, including the admission standards, the number of admissions, the changes and corresponding reasons, to examine the development of the accredited secondary school admissions system of Chinese Christian universities from 1879 to 1952. The research found that the accredited secondary school admissions system of Christian universities in modern China has roughly gone through five stages: rise, reform, shutdown, re-emergence and demise. As a foreign system, its development, change and final demise are affected by complex internal and external factors such as changes in the superstructure of modern China, traditional Chinese examination culture and improvement of the university’s own quality.

Introduction

As the well-known minister of the late Qing Dynasty, Li Hung-Chang, once put it, Chinese society in the second half of the nineteenth century was in a period of rapid transformation and confronted a major change unseen in thousands of years,Footnote1 facing unprecedented challenges in all respects. In 1844, China and the US signed the Treaty of Peace, Amity, and Commerce, between the United States of America and the Chinese Empire. The treaty stipulated that if US citizens sought permanent or temporary residence in the five ports for trade, they should be allowed to rent civil houses or rent a stretch of land where they could build their own houses, whilst hospitals, churches and funeral parlours should also be offered.Footnote2 Thereafter, missionaries were allowed to do missionary work. More and more countries followed suit. Under the impact of foreign culture, China’s traditional culture showed a trend towards decline. Many people with insight advocated learning from the West. The second wave of western learning thus formed a climax. An American missionary to China, Calvin Wilson Mateer, once said bluntly, “the trend of Western civilization and progress is coming towards it [referring to China]. This irresistible trend will spread all over China.” Footnote3 It was precisely under this trend that all kinds of missionaries worldwide, including Anglican, Methodist, Congregationalist, Presbyterian, Baptist, China Inland Mission, LutheranFootnote4 and other sects, came one after another and started their missionary journey.

Thanks to the early practice of missionaries in China, church education gradually played an increasingly important role in missionary work. Especially after the establishment of the China Education Association in 1890, the idea of vigorously developing church education was recognised by most missionaries. Francis Dunlap Gamewell once pointed out that the establishment of missionary schools was of great significance in that all kinds of schools in China, seeing the neat and perfect schools set up in the Methodist church, would be inspired to either observe each other for progress or strive to improve and revitalise themselves.Footnote5 Among all the missionaries in China, the missionaries from Britain and the United States were the most powerful, and the Christian organisations of the two countries, for the purpose of attracting young people from all parts of the Empire and putting them under the influence of Christianity and Christian civilisation,Footnote6 actively established various educational institutions including higher education in all parts of China. In the more than 70 years since the establishment of St John’s College in 1879 to the nationalisation of all colleges and universities receiving foreign subsidies by the Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China in 1952, church organisations established nearly 20 universities in mainland China.Footnote7 In China, Christianity in a broad sense is generally referred to as Christian religion, though the word Christianity refers specifically to Protestantism.Footnote8 Therefore, in this research, Protestant universities are also referred to as Christian universities, with a total of 13 universities named: Hangchow University, Cheeloo University, Yenching University, St John’s University, Huachung University, Soochow University, Nanking University, Lingnan University, University of Shanghai, Hwa Nan College, West China Union University, Ginling College, and Fukien Christian University.Footnote9

At the beginning of their establishment, these schools were self-contained, and the level of education was not clear. Jessie Gregory Lutz once said that although a few schools were founded as institutions of higher learning, most experienced a development path from primary school through secondary school to junior college; schools often called themselves universities, even though few or no students were enrolled in university courses. For students, mission schools, which promised to cover the full cost in school, attracted those families that could not afford to give their children a classical Chinese education.Footnote10 In fact, as church universities generally had secondary schools attached, most students in the early days of the university’s establishment depended on missionary secondary schools. At that time, China was still in transition from traditional education to a modern model. Especially after the abolition of the imperial examination system in 1905, new schools were in the ascendant, while the modern school system had not yet been established, leading to inconsistency of enrolment subjects at different types of schools, such that specific enrolment operations and practices at the time were quite rich and complicated. As foreign mission schools, Christian universities fully embodied the spirit of the school following the church.Footnote11 Most schools “followed the system and regulations of the Western mission,” Footnote12 and used the model of the comparatively mature American native denominational schools as the blueprint to establish the accredited secondary school admissions system, which was in line with the certificate admissions system of American universities in the 1870s.Footnote13 It was not until 1913, when, after the reorganisation of the China Christian Education Association (CCEA), the financing of universities’ school-running funds became organised, that the voices which repeatedly demanded the improvement of academic standards and school-running quality were also taken seriously, and thereafter the schools’ level and reputation began to rise. The establishment of the American-style Renxu school system in 1922, and the subsequent requirements of the Republic of China government for their registration, cemented the university status of the church universities after the registration was officially recognised, and the admissions system and courses also began to be in line with domestic universities. The sources of students were gradually enriched, and the identities of their parents included farmers and manual labourers, as well as businessmen, teachers, missionaries and other groups. Christian universities subsequently showed a clear trend of Sinicisation in the admissions system and other aspects. Their fate was closely related to the domestic political situation, and fluctuated with the changes in the political situation until they left mainland China.

China is an ancient country with a long educational history of examinations, and any topic related to exam admissions and talent selection has attracted much attention. As far as the college admissions test in the Republic of China is concerned, it has attracted many scholars to conduct research due to its rich and complicated admissions system and practices.Footnote14 However, it seems that these studies have two problems: on the one hand, they focus on national universities and private universities, while the research on church universities is still lacking; on the other hand, they focus on university admissions policies but lack the analysis and understanding of specific admissions practices. Not enough attention has been paid to church universities, which, along with national universities and private universities, constituted the three pillars of the then university education, or to the introduction, development and decline of the accredited secondary school admissions system, which is a crucial enrolment method of the church universities. It is considered that discussing these issues is helpful to understand better the role of church universities and their admissions system in the Republic of China. It is also useful to examine the delicate relationship between church universities and the government.

This research mainly adopts the literature method and the comparative method, using the school history materials of various church universities, books and newspapers from 1879 to 1952, and some research results of modern people as data sources, to investigate the accredited secondary school admissions system of 13 Christian universities in modern China. First, it analyses the development path of the accredited secondary school admissions system of Chinese Christian universities and discusses the measures and reasons for implementing the reform of the accredited secondary school admissions system at different stages of development. Second, to make up for the lack of previous studies on the specific admissions practices of universities in the Republic of China, the specific admissions practices of Christian universities will also be examined separately, including their criteria for selecting the accredited secondary schools and how to select students from the accredited secondary schools. Finally, through the statistics of the number of students admitted by individual universities at different stages from the accredited secondary schools and their proportion among the new students admitted, the role and rise and fall of the accredited secondary school admissions system in Christian university admissions is considered.

Development of the Accredited Secondary School Enrolment System of Christian Universities in Modern China

The accredited secondary school enrolment system in Chinese Christian universities roughly progressed from thriving to declining and can be divided into five stages ().

Table 1. List of main development stages of Christian universities in modern China

First Phase: Thriving Stage (1879–1920)

In the early days of the establishment of Christian universities in China, most schools directly transplanted the school running methods of local denominational universities in the United States. They also used the certificate admission system inherited from local universities in the United States as one of the enrolment methods and established affiliated secondary schools or established accredited secondary schools, where students could enter the school without examination upon recommendation. Huang Longxian, who worked in the higher education department of the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China, described Christian university enrolment during this period. He said that there were three main ways to enter universities in the United States. First, each university held an entrance examination individually. The second method involved universities forming an entrance examination committee whereby prospective students took the examination together. Finally, the third method involved a recommendation from accredited secondary schools. Most church universities adopted the third method.Footnote15

There were three main reasons Christian universities adopted the accredited secondary school enrolment system during the first phase. First, there was a severe shortage of secondary school students. According to the China Continuation Committee statistics, in 1918, there were 69,902 students in non-church schools in 19 provincesFootnote16 in China, while the total number of students in Christian church schools was only 15,213. However, by 1916, the number of higher normal schools, universities and junior colleges in China had reached 104, plus more than a dozen church universities.Footnote17 It was clear that the number of secondary school leavers could not meet the enrollment demand for higher education.

Regarding limited students, Christian universities were not attractive enough to recruit a large number of students, even after enrolling some students by promising to exempt them from tuition and accommodation fees, and other preferential enrolment policies. Schools still faced a problem: when students needed to contribute part of their family finances or get married, it was difficult for the school to keep them, and most of them left school before graduation.Footnote18 Therefore, Christian universities had to recruit students from church secondary schools. Second, the church school system was disconnected from the Chinese system at that time. In 1906, the Board of Education of the Qing Dynasty issued a document which stipulated that there was no need to file a case to establish schools for foreigners in mainland China, and foreigners who applied to open schools in the mainland did not need to file a case either.Footnote19 With the promulgation of this document, church schools developed their own systems and developed rapidly. In 1912, China implemented the Renzi-Guichou School System, establishing a vertical system of three stages and four levels for primary (including lower and higher primary schools), secondary and higher education. Furthermore, higher education was divided into specialised schools, higher normal schools and universities, but church universities were not taken into consideration. The Chinese government not only ignored church universities in the educational system but also ignored the existence of church schools in official documents, which led the church to promote its own institutions. As a result, the two educational systems were quite different and disconnected.Footnote20 Christian universities then had to develop affiliated schools and establish preparatory and accredited secondary schools as a source of students for the university. In addition, examination-free admission was a traditional method of early church schools, and most Christian universities were upgraded from church secondary schools. Therefore, the original system’s legacy was that Christian universities adopted an examination-free admission system to admit students from church secondary schools. Third, in the late Qing Dynasty and the early Republic of China, none of the universities formed a unified enrolment and examination system. Schools at all levels had their own admission offices or admission committees, and the school itself managed propositions, examinations, marking and admissions.Footnote21 Christian universities also had absolute control over enrolment and were not bound by Chinese policies and regulations. Therefore, they could freely formulate enrolment policies suitable for the survival and development of Christian university students.

Under the influence of these factors, some Christian universities, such as Yenching University, the University of Shanghai, St John’s University and Soochow University, established affiliated middle schools, and some established accredited secondary schools to select students. In 1915, the charter of the University of Shanghai stipulated that students from schools – except for Suzhou Yancheng Secondary School, Hangzhou Huilan Secondary School, Ningbo Baptist Secondary School, Shanghai Qingxin Secondary School (American Presbyterian Mission North) and the secondary school of the Methodist Episcopal Church – were required to pass an examination before being admitted.Footnote22 In 1914, the Charter of St John’s University stipulated that students with diplomas from Suzhou Taowu Secondary, Anqing Sao Paulo and Yangzhou Meihan Schools could undergo preparatory study at the university without examination.Footnote23 From 1915, secondary school graduates with good grades from church schools and other senior secondary schools – such as Yangzhou Meihan Secondary School, Anqing St Paul Secondary School, Ningbo Fei Di Secondary School, Quanzhou Peiyuan Secondary School, Shanghai Minli Secondary School and Shanghai St John’s Youth Association Secondary School – were allowed to enter the university without an examination.Footnote24 Soochow University also established a number of accredited secondary schools, such as Soochow University No. 3 Secondary School, and stipulated that students who graduated from the school could directly study at Soochow University.Footnote25 In the autumn of 1920, the Yenching University Handbook also stipulated that students from accredited secondary schools or preparatory programmes at Yenching University could be exempt from the entrance examination after submitting a verification document.Footnote26

Second Phase: Transformation Stage (1920–1937)

In the 1920s, new changes took place in the accredited secondary school enrolment system in Christian universities. In December 1927, the Quarterly Journal of Christian Education reported that students admitted to the College of Arts or Sciences of universities were required to submit a secondary school diploma and pass an entrance test. However, six universities remained that allowed students from affiliated secondary schools to enter university without examination. In addition, students in the affiliated secondary schools of the four other universities could be exempted from a portion of the exams and only take tests on the main subjects.Footnote27 Therefore, Christian universities adopted two admission methods during this period: admission with and without examination.

The reason for this change is closely related to the rapidly changing political and religious situation in China at that time. In the 1920s, with the further deepening of cultural exchange between China and the West, various contradictions also appeared initially. In 1922, the Anti-Christianity Movement arose in China, and the recovery of the right to education became a national consensus.Footnote28 Under the influence of the movement, Christian universities and other church schools received public criticism and had difficulty surviving. Meanwhile, the Chinese government was also constantly required to strengthen the management of church universities. It not only issued regulations to promote the registration of church schools many times but also required them to accept the constraints of China’s educational policies and regulations. In 1930, the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China stipulated that graduates of affiliated secondary schools of universities could not directly enter the university without examinations. If a university abolished the preparatory course, it was allowed to establish an affiliated secondary school to provide relief to students entering the university. However, students were not allowed to enter the university directly without examinations after graduating from the affiliated secondary school; to show fairness and prevent abuse, like other students, they needed to take an entrance examination upon which their admission would be based.Footnote29 Article 20 of the University Organisation Act, promulgated by the National Government in 1929 and amended in 1934, also stipulated that the admission qualifications for university students should be that they had graduated from secondary school or an accredited private secondary school or equivalent school and had passed the entrance test.Footnote30 The Anti-Christianity Movement outbreak and the Chinese government’s regulatory requirements had an incalculable impact on Christian universities. These were the most direct factors that prompted Christian universities to conduct enrolment reforms.

At the same time, the reform of the admissions system of Christian universities during this period was also deeply influenced by the Chinese examination culture. In China, both the government and the people formed a deep-rooted thought of using examinations to measure the level of candidates and to pursue fair competition. Even after the 1,300-year-old imperial examination system was abolished, the role and impact of examinations on Chinese society were still significant. In 1928, the Nanjing National Government even coordinated the examination power with the executive, legislative, supervisory and judicial power, making it an important element in the separation of five powers in the national governance system. Therefore, the Nanjing National Government believed that the university admissions system, which was responsible for selecting talent, should also have strict entrance examinations. This was also an important reason why the government of the Republic of China had always required all Christian universities not to directly enrol students without testing. Enrolling students through the university entrance examination system could demonstrate fairness and prevent the admission of many low-level students.

The reform of the accredited secondary school enrolment system is also inseparable from the development needs of Christian universities. In 1921, under the impetus of various forces such as the Chinese Christian University, Ernest DeWitt Burton led the China Educational Commission to China. After the China Educational Commission arrived, it investigated the contribution of Christian churches, what education should do and the status of Christian education in the Chinese education community.Footnote31 After more than four months of investigation, it issued a survey report on Christian education in China and released several slogans such as “More Efficient, More Christian, and More Sinicisation” to clarify the development direction of Christian universities. The slogan of Sinicisation became an important principle for the reform of Christian universities. Edwin C. Lobenstine, the executive director of the China Continuation Committee, also stated that Christian higher education should be tailored to Chinese conditions and needs.Footnote32 Therefore, under the guidance of the slogan of Sinicisation, the enrolment policies and methods of Christian universities moved gradually closer to Chinese policy requirements and national universities. In addition, in the 1920s, although the education system of Christian universities in China had been basically formed, China’s domestic national universities and private universities were constantly growing, and church, national and private universities faced tripartite confrontation. Given the fierce competition, church universities set higher development requirements to seek their own development, hoping to concentrate all their financial and human resources to run a handful of excellent rather than several low-level schools.Footnote33 In short, due to the need for competition and quality improvement, the enrolment system also became an important part of the reform of church universities.

Based on various motivations, Christian universities adjusted their enrolment systems accordingly. The University of Shanghai adopted an accredited system for graduates from 17 and four men’s and women’s secondary schools, respectively, which were contacted immediately regarding admission. Other secondary school graduates were required to pass the entrance examination.Footnote34 Nanking University officially instigated an entrance examination in September 1919.Footnote35 After Yenching University recognised Tianjin Nankai Middle School as an accredited secondary school, it also required students’ graduation scores to be a B on average (above 80 points). Students of Chinese, English, arithmetic, history, geography and natural sciences required an average grade of B (above 85 points); the school could sponsor students for further studies, and all students who were sponsored for further studies could only take the three exams in Chinese, English and general intelligence.Footnote36 Fukien Christian University stipulated that university entrance tests should be divided into two types: A and B. All public or registered private senior secondary schools listed as accredited secondary schools by the university had their graduates take the type A examination, while graduates from other schools took the type B examination.Footnote37 St John’s University also stipulated that graduates from accredited secondary schools of the university should be admitted upon the recommendation of the principal of the secondary schools and also needed to pass the entrance and English examinations of the admission procedures.Footnote38 The measures for recommendation and exemption from the examination of the University of Shanghai stipulated that for accredited secondary school graduates whose total average age score in the three academic years was listed as second class or above, the secondary school would issue a letter to recommend them, and they would also need to pass the examination of the admissions committee of the university. They could then be exempted from the entrance examination. Other graduates, except those recommended by the accredited secondary school, were required to pass the entrance examination but had to take only Chinese and English; those who wanted to study science needed to take physics and trigonometry and submit experimental notes.Footnote39 After that, the University of Shanghai raised its enrolment requirements again; performance requirements required students to be listed as the best in the general average of their senior high school and pass the senior secondary school certificate of education examination.Footnote40 The Admission Constitution of Cheeloo University also stipulated that secondary school graduates wishing to attend Cheeloo University needed to either pass the general admission examination or hold a certificate from a school accredited by Cheeloo University.Footnote41

Third Phase: Standstill Stage (1937–1945)

In 1937, the Japanese War of Aggression against China broke out in full force. During the war, except for West China Union University, the remaining 12 Christian universities successively joined the movement for school relocation. Although some church secondary schools were associated with Christian universities and moved with them, the connection between Christian universities and church secondary schools as a source of students was interrupted or seriously weakened.Footnote42 The accredited secondary school system, which was once an important method of enrolment for Christian universities, moved almost to a state of standstill. However, new and flexible enrolment methods continued to emerge during this period. In 1939, five universities – West China Union University, University of Nanking, Ginling College, Cheeloo University and Yenching University – held joint enrolment at universities in Hua Xiba, China. In addition, some universities continued to implement personalised enrolment plans. These universities adjusted their enrolment strategies according to wartime conditions and their own educational conditions to seek school development opportunities. Notably, although the autonomy of Christian university enrolment was strengthened to a certain extent during the war, the Government of the Republic of China continuously demanded that the supervision of enrolment be strengthened. In 1940, the Ministry of Education also banned private and church universities from continuing to recruit students at the same academic level and required these universities to supervise the entrance tests of incoming first-year students.Footnote43

Generally speaking, although the relocation of colleges and universities caused the disconnection of Christian universities and secondary schools and almost caused the suspension of the accredited secondary school system, some schools still retained and implemented the system. For example, in 1941, Yenching University held an accredited secondary school examination. Yenching University Biweekly recorded that admission examinations for the accredited secondary schools were completed on 9 and 10 May in Peking, Tianjin, Shanghai, Hong Kong and Changli.Footnote44

Fourth Phase: Rejuvenation Stage (1945–1949)

After victory in the War of Resistance against Japan in 1945, the Christian universities that moved to the western part of China began to discuss demobilisation and reinstatement. With the relocation of Christian universities, the original admission method with an accredited secondary school entrance test was revived. For example, in 1947, Yenching University admitted 173 students from accredited secondary schools, including 29 male and 35 female students in the Faculty of Arts, 61 male and 29 female students in the Faculty of Science, and 11 male and eight female students in the Faculty of Law.Footnote45 Based on the original nature of the accredited secondary school system, new changes took place in the enrolment method. The original method of combining entrance examination-free admission and entrance examinations evolved into a system of entering university without sitting entrance examinations. This approach was essentially the recommended exemption system for accredited secondary schools (or affiliated secondary schools), which church universities had widely adopted in the early twentieth century.Footnote46

The main reason for this change was the urgent need for school relocation to improve the quality of students and increase the proportion of Christians among students. Due to the destruction of the war, it was quite difficult for the schools to resume teaching. Yifang Wu, the president of Ginling College, said that many of the campuses in Nanjing were destroyed, and the equipment, books and furniture in the school were also damaged, meaning that it was difficult to restore the college to its original state.Footnote47 The school not only suffered heavy losses in terms of hardware, but the previously formed stable enrolment system was also significantly impacted. The quality of students declined to a certain extent, and the proportion of Christians in the school also fell sharply. To quickly restore contact with the church secondary schools and select high-quality students to enter the university, some teachers called for the implementation of the accredited secondary school enrolment system without examination. In October 1947, more than 20 people – including Professor Yukai Wang of Hangchow University – cited the method of the University of Michigan admission system on the grounds that the summer recruitment of universities in China had a particularly adverse impact on students’ health. Taking advantage of the National Conference on Christian Education to be held in Shanghai, it was proposed that a method should be formulated, and it was recommended at the conference that those who passed the secondary school students’ examination with an average score of 80 points or more could be admitted to the university without examination. The proposal of this scheme caused heated discussion, and Professor Wang also suggested that the adoption of this method should be implemented by Christian universities first and then spread to all universities in China, which could be regarded as a positive change in China’s university education policy.Footnote48 After the enrolment method was proposed, some schools adopted it. In 1948, Lingnan University decided to select 20 well-managed schools from all church secondary schools (except Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and Macau) and selected graduates with the highest scores, recommending that two students enter university without examination.Footnote49 However, some Christian universities believed that the original entrance examination method for graduates of accredited secondary schools had been successful since the trial implementation,Footnote50 so they did not adopt the proposed method. Therefore, the accredited secondary school enrolment system without examination was not widely promoted in Christian universities. Other universities, such as West China Union University, Yenching University, the University of Shanghai, Ginling College, Nanking University, Hangchow University, Hwa Nan College and Fukien Christian University, followed the previous admission system for accredited secondary schools when enrolling students in 1948.Footnote51

Fifth Phase: Dying-Out Stage (1949–1952)

In 1949, the People’s Republic of China was founded. The political environment and other aspects underwent qualitative changes, and the government’s attitude towards Christian universities also changed from the initial strengthening of management to ultimate acceptance. On 14 August 1950 the Interim Measures for the administration of private colleges and universities, requiring that private universities, including Christian universities, should be registered again, and the administrative power of the school, the right to financial certificates and the ownership of property needed to be controlled by the Chinese.Footnote52 In 1952, the Chinese government implemented a policy of adjusting and merging colleges and departments, and all church universities, including Christian universities, were dismantled and divided into different universities. The history of Christian universities in mainland China ended. Accordingly, the autonomy of enrolment of Christian universities was gradually reduced until it was entirely cancelled, and the accredited secondary school enrolment system also died. It was replaced by the nationwide unified examination for admissions to general universities and colleges (Gaokao).

Accreditation Rules and Enrolment Numbers of the Accredited Secondary School Enrolment System in Chinese Christian universities

Accreditation Rules

Before the 1920s, Chinese Christian universities were still developing and did not form a complete Christian university education system, consequently not forming an accredited secondary school enrolment system completely. They simply investigated the school curriculum, student performance and other matters, then appointed commissioners to inspect qualified secondary schools and decide whether a school should be accredited. In general, a secondary school was considered an accredited secondary school if it met the basic accreditation rules. For example, in 1920, the Instructions of Yenching University stipulated that a secondary school or preparatory school should be accredited only if its curriculum and the students’ entrance examinations were approved; then, the inspectors of the university were allowed to visit, and the conditions were qualified.Footnote53

From the 1920s, the Christian university education system was preliminarily formed, and a relatively mature accredited secondary school enrolment system was produced. During this period, there were detailed accreditation rules for accredited secondary schools. First, regarding accreditation rules for accredited secondary schools, there were four main aspects of the rules, the first of which was the registration requirements. In response to the Chinese government’s registration regulations, Christian universities considered the registration requirements of secondary schools as the primary criteria. For example, in 1933, the provisional rules for the accredited secondary schools of Yenching University required that an accredited secondary school be a public or private senior secondary school that had been registered.Footnote54 Huachung University also required that all registered senior secondary schools request recognition.Footnote55

The second aspect of the rules was the curriculum standards. It was generally required that the senior secondary school and undergraduate curriculums be able to connect, at least to a certain extent. For example, Yenching University required that the courses of accredited secondary schools should include Chinese, English, mathematics, history, geography and natural sciences.

The third aspect was school performance. The university could accredit only secondary schools with excellent performance. For example, the Tianjin Nankai Middle School was accredited by Yenching University in 1930 because of its outstanding performance in school administration. According to the Nankai Double Week, an official letter from Yenching University was obtained, stating that the school had excellent courses, and it was proposed that the school be an accredited secondary school.Footnote56

The fourth aspect of the rules was student performance. This mainly included students’ grades in secondary school and entrance exams. For example, as required by Lingnan University, senior secondary school students needed to have completed three years of senior high school in each subject with passing grades and good conduct; they also needed to have been in school for more than one year and to have failed exams at no more than two points in each year.Footnote57

In summary, schools become accredited secondary schools only when they and their students met the above requirements and were accredited by the university. For example, Cheeloo University accredited 10 secondary schools, including Luoxian Culture Secondary School, Huangxian Chongshi Secondary School and Beijing Chongshi Secondary School, as accredited middle schools from 1925 to 1927.Footnote58 However, the qualifications of accredited secondary schools were not permanent. They needed to be assessed by universities regularly, and the list of accredited schools was updated accordingly. For example, in the early 1920s, Yenching University had a total of 29 accredited high schools. By 1933, the number of accredited high schools had increased to 37, including a foreign secondary school: the Chinese Association Hall Middle School in Batavia, Java (present-day Jakarta, Indonesia).Footnote59 By 1937, the number of accredited secondary schools at Yenching University grew to 38. Compared with the list of accredited schools in 1933, one school – Shanxi Fenyang Mingyi Secondary School – was removed, and Fujian Gezhi and Guangdong Peidao Secondary Schools were added.Footnote60

Admission examination methods for accredited secondary schools were also important. Before forming relatively complete examination rules, the admission examinations for accredited secondary schools were generally organised by secondary schools and reviewed by the universities and later evolved into simultaneous holdings in different districts. For example, Yenching University stipulated that admission examinations for middle-school students were scheduled to start on 11 May 1935 and the examination area was divided into 14 districts across the country: Peking, Tianjin, Changli, Shanxi, Shanghai, Nanjing, Zhejiang, Wuchang, Nanchang, Changsha, Fuzhou, Hot Spring, Guangzhou and Balenvia Districts.Footnote61 During the war of resistance against Japan, Christian universities also adopted flexible ways of recruiting students, such as surrogate recruitment by other schools. When a Christian university moved back to its original site, the system of surrogate enrolment of other schools was retained to a certain extent, and the enrolment forms tended to be diversified. Some universities established examination areas in their localities, while others established examination areas in the whole country or entrusted other universities with recruitment. For example, in 1948, the West China Union University in Chengdu stipulated that it would not set up an examination area outside the province that year; however, if students in Xiamen wanted to enter that university, they could take the examination of Fukien Christian University.Footnote62

Finally, the examination time and subjects were important criteria. Admission examinations for accredited secondary schools were usually held in June or July of each year. Some universities that enrolled students twice a year would also set an enrolment date in May or September; re-examinations could also be flexibly arranged according to specific circumstances. Regarding examination subjects, there were great differences between schools and some differences in each period for the same school. For example, in 1934, the entrance examination of Fukien Christian University was divided into two types, A and B, where there were nine subjects for the type A exam, including citizenship, Chinese composition, Chinese knowledge, English composition, new English vocabulary, English reading, an intelligence test, military training (exempted for girls) and an oral examination. At Yenching University, the early exam subjects were only English and intelligence. Later, students who were recommended for admission were required to take three examinations in Chinese, English and intelligence.Footnote63 Mathematics was added to the exam in 1935.

Admission Numbers and Proportions

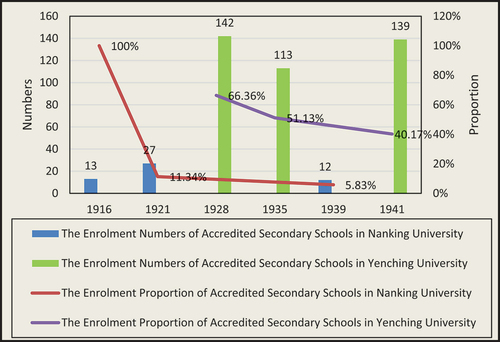

Investigating the number and proportion of students at Christian universities admitted from accredited secondary schools can reflect the importance of the accredited secondary school system in Christian universities in different periods and the rise and fall of the system. Before the 1920s, church secondary schools were better able to connect with Christian universities regarding teaching purposes and curriculum settings. Therefore, during this period, the secondary schools accredited by Christian universities were almost church secondary schools, and the sources of students also almost all depended on them. From the 1920s, Christian universities conducted a series of reforms, and the quality of teaching and the schools’ reputations improved greatly. In 1933, the American Laity Investigation Mission stated in China’s Christian University that Christian universities attracted most of the brightest Chinese youth.Footnote64 Correspondingly, the source of students in Christian universities during this period was more abundant than before, and the number and proportion of students admitted from accredited secondary schools also showed a downward trend. According to the statistics, Nanking University had a total of 120 and 124 students in 1915 and 1916, respectively,Footnote65 excluding nine graduates in 1916;Footnote66 it can be inferred that the enrolment of Nanking University in 1916 was 13. Nanking University did not admit non-church secondary school students before 1917. Therefore, all 13 students should be considered accredited secondary school students and affiliated middle-school students, accounting for 100% of all first-year students. By the autumn of 1921, 27 directly promoted students were in affiliated secondary schools, accounting for 11.34% of the 238 first-year students.Footnote67 At Yenching University, the same development trend as Nanking University was identified. Yenching University enrolled 142 studentsFootnote68 from accredited middle schools in 1928. In the same year, 214 new studentsFootnote69 were admitted. The number of accredited secondary schools admitted accounted for 66.36% of the total number of new students. In 1935, the number of accredited secondary schools fell slightly to 113;Footnote70 although the total number of new students admitted to the school that year has not been found, from the development trend of the total number of school registrations,Footnote71 the total number of new students admitted should also show an upward trend. Therefore, regarding the decline in the number of accredited secondary schools and increase in the total number of new students admitted, there should be a significant downward trend compared with the proportion in 1928.

Later, Christian universities were affected by Sinicisation and war, and the number of students enrolled in accredited secondary schools declined further. In the autumn of 1939, 206 first-year students were admitted to Nanking University, of whom only 12Footnote72 were recommended by the affiliated secondary schools, accounting for 5.83%. Yenching University also showed the same trend in student recruitment. In 1941, of 197 students recommended by accredited secondary schools, 139 students were admitted, including 33 from the Faculty of Arts, 86 from the Faculty of Science and 20 from the Faculty of Law.Footnote73 That year, the total number of new students at Yenching University was 346.Footnote74 It can be calculated that the number of admitted secondary schools accounted for 40.17% of the total number of admitted students, which was a further reduction compared with 1935.

After the war, all schools were moved back to their original sites, and some schools developed an examination-free admission system based on the accredited secondary school enrolment system, but the number of people admitted by this method was limited. In 1948, Lingnan University selected 20 well-managed schools from all church secondary schools (except from Guangdong Province, Hong Kong and Macau), and selected graduates with the highest scores, recommending two exemptions for admission.Footnote75 From this point of view, Lingnan University selected only students with the top grades in the secondary schools for the examination-free admission system; thus, it is speculated that only a tiny percentage of students could be admitted.

In summary, after investigating the implementation by Christian universities of the accredited secondary school enrolment system in different periods, it was found that the number and proportion of students admitted from accredited secondary schools showed a significant downward trend (), showing that the system experienced a move from prosperity to decline.

Figure 1. Enrolment numbers and proportions of accredited secondary schools in Nanking University and Yenching University.

Conclusion

The church secondary school was the main school that provided students with a source to a church university.Footnote76 Therefore, it is self-evident that the accredited secondary school enrolment system, which served as a bridge between the two, played an important role in developing Christian universities. By tracing the development of the system in Christian universities and examining specific enrolment details, this study found that the accredited secondary school enrolment system occupied a crucial position in the early development of Christian universities and made significant contributions to attracting new students to Christian universities.

As the development and reform of the university admissions system was affected by multiple factors from outside and within the university, the following conclusions can be drawn from the analysis of the rise and fall of the Christian universities and their accredited secondary school admissions system in modern China.

First, Christian universities and their accredited secondary school admissions system were foreign education systems closely related to religion and politics, and their operation was highly dependent on the specific national political and social environment. The accredited secondary school admissions system of Christian universities gradually changed from the certificate admission system of American universities in the 1870s to a more “Sinicised” admissions system, which was closely related to the Anti-Christianity Movement that arose in China in the 1920s. The changes in the national political system and society brought about huge changes in the operation and management of the schools. The war from 1937 to 1945 had a great impact on the enrolment of Christian universities. The change of state power in 1952 directly brought a devastating blow to Christian universities and their admissions system, causing them to disappear from China.

Second, the examination culture also had a profound impact on the university admissions system. The implementation of the 1,300-year-old imperial examination system caused the Chinese government and people to form a psychological dependence on the examination system, and the practice of admission without examination and recommended admissions to the accredited secondary school system of Christian universities was different from the long-standing examination concept in China, which led to the continuous change and decline of the admissions system. After the new government of the People’s Republic of China took over Christian universities in 1952, the nationwide unified examination for admissions to general universities and colleges (Gaokao) was quickly established.

Finally, the reform of the university admissions system was also closely related to the improvement of its own quality. As the endogenous system of a university, the admissions system should be able to hold the first pass of university quality control. In the 1920s, Christian universities faced the pressure of competition with national universities and private universities; reforming the admissions system and recruiting better students thus became the starting point for improving the quality of school education. There was essentially a fundamental need for Christian universities and their admissions system to adapt to the national conditions of modern China.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Qichao, Biography of Li hung-Chang, 63.

2. Tieya, Collection of Chinese, 54.

3. Xuexun, Teaching Reference, 10.

4. China Continuation Committee, Christian Occupation of China, 26.

5. Youhuan and Shiliang, Historical Materials, 47.

6. Yihua, Shanghai St John’s University, 7.

7. Zhengping, “Christian Colleges,” 127.

8. Chinese Academy, Basic Knowledge, 1.

9. Lutz, China and Christian Colleges, 506–9.

10. Ibid., 23, 66.

11. Licheng, American Cultural, 33.

12. Chucai, Historical Materials, 137.

13. Ningning, Research on Admission Examination, 183.

14. Yaoming, “College Enrollment System,” 69–74; Xianjun, “Review of Independent Enrollment,” 39–42; Xiangdong, Transformation and Reconstruction, 1–304; Tao, Study of Admission, 1–186; Hayhoe, China’s Universities, 29–70; Ningning, Research on the Admission Examination, 1–358.

15. Longxian, “Unified University,” 1–2.

16. Including Northeast, Zhili, Shandong, Shanxi, Shaanxi, Jiangsu, Zhejiang, Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Hubei, Hunan, Fujian, Guangdong, Guangxi, Gansu, Guizhou, Sichuan and Yunnan (19 provinces).

17. China Continuation Committee, Christian Occupation, 618, 612, 619.

18. Lutz, China and Christian Colleges, 67.

19. Xincheng, Historical Materials, 135.

20. Lutz, China and Christian Colleges, 100.

21. Xuewei, General History, 273.

22. Licheng, American Cultural, 49.

23. St John’s University, St John’s University Statutes, 76–7.

24. Hanmin, 20th Century Shanghai Literature, 3.

25. Soochow University, Soochow Years, 191.

26. Yenching University, Yenching University Brochure, 14.

27. Chucai, Historical Materials, 140.

28. Qinshi, Religious Thoughts, 342.

29. Ministry of Education, “Students of University.”

30. Research Office, Selections of Educational Regulations, 417.

31. Christian Education Survey of China, Christian Education, 6.

32. Lobenstine, “Recent Status and Current Problems,” 21–31.

33. Shih, “Difficulties in Church Education Today,” 7.

34. Shaochang, “Student Life in this School,” 34.

35. Li, “Choose Students,” 167.

36. Tianjin Nankai Middle School, “School News,” 83.

37. Fukien Christian University, View of Fukien Christian University, 36.

38. St John’s University, View of St John’s University, 44.

39. University of Shanghai, View of University of Shanghai, 1931, 33–4.

40. University of Shanghai, View of University of Shanghai, 1936, 35.

41. Cheeloo University, Articles of Association, 22.

42. Jiafeng and Tianlu, Christian University, 134.

43. Ministry of Education, “Admissions Procedures.”

44. Alumni History Compilation Commitee, History of Yenching University, 1310.

45. Yenching University, “Announcement of the Admission of New Students,” 1.

46. Ningning, Research on the Admission Examination, 91.

47. Nanjing Central, “Chengdu Ginling.”

48. Shenzhou Agency, “The Professor of Hangchow University.”

49. Shenzhou Agency, “Church University Summer Enrolment.”

50. Nanking University, “Recent News of the Academic Affairs,” 2.

51. Shenzhou Agency, “Church University Summer Enrolment.”

52. Dongchang, Important Educational Documents, 47–8.

53. Yenching University, Yenching University Brochure, 14.

54. Ningning, Research on the Admission Examination, 185.

55. Wenjuan, Christianity and Secondary Education, 98.

56. Tianjin Nankai Middle School, “School News,” 83.

57. Lingnan University, View of Private Lingnan Universities, 245.

58. Cheeloo University, Articles of Association of Shandong, 24.

59. Alumni History Compilation Committee, History of Yenching University, 1256–7.

60. Yenching News Agency, “The Accredited of Secondary Schools,” Yenching News, March 26, 1937.

61. Yenching University, “The Entrance Examination for Yenching.”

62. Shenzhou Agency, “Church University Summer Enrolment News.”

63. Tianjin Nankai Middle School, “School News,” 83.

64. Chucai, Historical Materials, 143.

65. Li, “Choose Students,” 163.

66. School History Compilation Group, Collection of Historical Materials, 210.

67. Li, “Choose Students,” 163–4.

68. Ningning, Research on the Admission Examination, 184.

69. Alumni History, History of Yenching University, 1177.

70. Yenching University, “The Entrance Examination for Yenching University.”

71. The numbers of students enrolled in the autumn at Yenching University from 1928 to 1935 (except 1932) were 700, 747, 809, 811, 815, 797 and 884. (Alumni History Compilation Committee, History of Yenching University, 1187, 1214, 1232, 1235, 1264, 1271, 1278.)

72. Nanking University, “Statistics of the Academic Affairs Office,” 3.

73. Yenching News Agency, “139 People were Admitted.”

74. Alumni History Compilation Committee, History of Yenching University, 1310.

75. Shenzhou Agency, “Church University Summer Enrolment News.”

76. Lutz, China and the Christian Colleges, 153.

Bibliography

- Alumni History Compilation Committee of Yenching University. History of Yenching University 1919–1952. Beijing: China People’s Publishing House, 1999.

- Cheeloo University. Articles of Association of Shandong Jinan Cheeloo University. Jinan: Cheeloo University, 1926.

- China Continuation Committee. The Christian Occupation of China. Beijing: China Social Sciences Press, 1988.

- Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and the Christian Studies Section of the World Religions Institute. Basic Knowledge of Christianity in China. Beijing: Religious Culture Press, 2008.

- Christian Education Survey of China. Christian Education in China. Shanghai: The Commercial Press, 1922.

- Chucai, L. Historical Materials on Education History of Imperialist Invasion of China Church Education. Beijing: Educational Science Press, 1987.

- Dongchang, H. Important Educational Documents of the People’s Republic of China. Haikou: Hainan Publishing House, 1998.

- Fukien Christian University. View of Fukien Christian University 1936. Fuzhou: Fukien Christian University, 1936.

- Hanmin, W. The 20th Century Shanghai Literature and History Database. Shanghai: Shanghai Bookstore Publishing House, 1999.

- Hayhoe, R. China’s Universities, 1895-1995: A Century of Cultural Conflict. New York: Garland Publishing Inc., 1996.

- Jiafeng, L., and Liu Tianlu. Christian University during the Japanese War of Aggression against China. Fuzhou: Fujian Education Press, 2003.

- Li, Y. “Choose Students and Student Choices: A Study on the Enrolment Policy and Student Groups of Nanking University in the Republic of China.” Historical Review 6 (2020): 162–177.

- Licheng, W. American Cultural Penetration and Modern Chinese Education, the History of Hujiang University. Shanghai: Fudan University Press, 2001.

- Lingnan University. View of Private Lingnan Universities. Guangzhou: Lingnan University, 1932.

- Lobenstine, Edwin C. “Recent Status and Current Problems of Christian Higher Education.” Chinese Christian Education Quarterly 3 (1926): 21–31.

- Longxian, H. “Review of the Unified University Enrolment Examination (Part 1).” Educational Communications Weekly 46 (1939): 1–2.

- Lutz, J. China and Christian Colleges, 1850–1950. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press, 1971.

- Ministry of Education of the Republic of China. “Students of University Affiliated Middle School are Not Allowed to Enter the University without Examination.” Shenbao, July 7, 1930.

- Ministry of Education of the Republic of China. “Admissions Procedures for Private Universities and Independent Colleges and Public and Private Junior Colleges in 1940.” Hankou Education Newsletter, May 25, 1940.

- Nanjing Central News Agency. “Chengdu Ginling College Returns to Nanjing during the Summer Vacation.” Shenbao, January 22, 1946.

- Nanking University. “Statistics of the Academic Affairs Office.” Journal of Nanking University, September 1939.

- Nanking University. “Recent News of the Academic Affairs Office of Nanking University.” Journal of Nanking University 371 (1948): 2.

- Ningning, Y. Research on the Admission Examination of Modern Church Universities in China. Wuhan: Central China Normal University Press, 2016.

- Qichao, L. Biography of Li hung-Chang. Beijing: Oriental Publishing House, 2009.

- Qinshi, Z. Religious Thoughts in the Past Ten Years in China. Beijing: Yenching Chinese Language School, 1927.

- Research Office of Educational History, Central Institute of Education. Selections of Educational Regulations of the Republic of China. Nanjing: Jiangsu Education Publishing, 1990.

- School History Compilation Group, Institute of Higher Education, Nanjing University. Collection of Historical Materials of Nan-king University. Nanjing: Nanjing University Press, 1989.

- Shaochang, L. “Student Life in This School.” Shanghai River Yearly 8 (1923): 34.

- Shenzhou Agency. “The Professor of Hangchow University Recommends that the University Adopt the Recommended System.” Shenbao, October 31, 1947.

- Shenzhou Agency. “Church University Summer Enrolment News.” Shenbao, May 29, 1948.

- Shih, H. “Difficulties in Church Education Today.” Chinese Christian Education Quarterly 1 (1925): 7.

- Soochow University. Soochow Years. Suzhou: Soochow University Yearbook Press, 1929.

- St John’s University. St John’s University Statutes (1912-1916). Shanghai: Shanghai Meihua Press, 1914.

- St John’s University. View of St John’s University (1930-1932). Shanghai: St John’s University, 1931.

- Tao, L. “A Study of Admission System of National University in Republic of China.” PhD diss., Southwest University, 2014.

- Tianjin Nankai Middle School. “School News: A Letter from Yenching University Accredited Our School as an Accredited Secondary School.” Nankai Biweekly 5 (1930): 83.

- Tieya, W. Collection of Chinese and Foreign Old Testament Chapters, Volume 1, 1689-1901. Beijing: SDX Joint Publishing Company, 1957.

- University of Shanghai. View of University of Shanghai 1931. Shanghai: University of Shanghai, 1931.

- University of Shanghai. View of University of Shanghai 1936. Shanghai: University of Shanghai, 1936.

- Wenjuan, Y. Christianity and Secondary Education in Modern China. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2007.

- Xiangdong, H. The Transformation and Reconstruction of the Examination System during the Period of the Republic of China. Wuhan: Hubei People’s Publishing House, 2008.

- Xianjun, X. “A Review of Independent Enrolment in Chinese Universities in the First Half of the 20th Century.” Educational Research and Experiment 4 (2001): 39–42.

- Xincheng, S. Historical Materials on Modern Chinese Education (Volume 2). Shanghai: Zhonghua Book Company, 1928.

- Xuewei, Y. General History of Chinese Examinations (Volume 4: Republic of China). Beijing: Capital Normal University Press, 2004.

- Xuexun, C. Teaching Reference Materials of Modern Chinese Educational History. Beijing: People’s Education Press, 1987.

- Yaoming, G. “On College Enrolment System in the Republic of China.” Teacher Education Research 4 (1997): 69–74.

- Yenching News Agency. “The Accredited of Secondary Schools of Yenching University are Actively Preparing for Examination.” Yenching News, March 26, 1937.

- Yenching News Agency. “A Total of 139 People Were Admitted from the Accredited Secondary School Examination.” Yenching News 7 (1941).

- Yenching University. Yenching University Brochure 1920. Beijing: Yenching University, 1920.

- Yenching University. “The Entrance Examination for Yenching University Accredited Secondary Schools Will Be Held in 14 Districts.” Yishibao (Tianjin), May 10, 1935.

- Yenching University. “Announcement of the Admission of New Students from Accredited Secondary Schools.” Yenching University Double Weekly 42 (1947): 1.

- Yihua, X. Shanghai St John’s University 1879-1952. Shanghai: Shanghai People’s Publishing House, 2009.

- Youhuan, Z., and Shiliang Gao. Historical Materials of Modern Chinese Educational System, Volume 4. Shanghai: East China Normal University Press, 1993.

- Zhengping, T. “Christian Colleges and Educational Modernization in China.” Journal of Literature, History and Philosophy 3 (2007): 127–134.