ABSTRACT

Design, manufacture and supply of school furniture in the Australian state of New South Wales following the Second World War occurred in a context of population growth and new ideologies of teaching and learning. This article addresses the particular situation in New South Wales, where administration of schooling remained highly centralised. The influence of little known educator, Herbert Oxford, his support for centralised furniture production and supply and his interest in ergonomics was crucial. In the 1960s, he coordinated planning for a School Furniture Complex that eventually operated in the 1980s. The Complex’s demise meant the end of a state service to education. The article contributes to research concerned with materialities of schooling and the argument that objects are both valuable sources and legitimate subjects for the historian. Department of Education documents located at State Archives, Departmental publications and Oxford’s writings inform the research.

Introduction

The arrangement of chairs, tables and work areas can help to stimulate the work of the teacher and pupil and release them from the bonds of uniformity. But layouts must not overlook the importance of the human relationship which exists between the pupil and the chair, table or bench that he uses.

H. W. Oxford, “The Importance of Human Factors in the Design and Layout of Educational Furniture,” 1.

Furniture provision to schools in Australia in the decades following the Second World War took place in a context of unprecedented population growth, the associated growth in the numbers of children going to school, the building and outfitting of new schools to accommodate them, an increase in the years spent by children in schooling and new ideas of pedagogy and the facilities needed for their realisation. This article addresses furniture provision in the Australian state of New South Wales from 1945 to the 1980s. The history of furnishing schools in the Australian states remains a neglected field, inviting research. This article is a contribution to that history. In a jurisdiction where all aspects of administration of state schooling remained highly centralised, the design, production and distribution of furniture in New South Wales was no exception. The important role and significance of educator Herbert W. Oxford, who took charge of furniture provision from 1949, is argued. His decisive role has never been studied. Research utilises insights from what has been referred to as a “material turn” within educational history and contributes to the argument that objects not only provide important sources for research, but are legitimate subjects in their own right, enriching the understanding of classrooms and schooling and the contexts within which they operated.

Historians of education from many countries have contributed in recent decades to research about the materialities of schooling. Within the social sciences, studies of materiality do not simply focus on objects themselves, but with “the dialectic of people and things.”Footnote1 For educational historians, this prompts questions about how objects arrive in schools, how they are used by teachers and students, how they affect the teaching and learning that takes place in the classroom, how they subsequently influence memories of school and what happens to them when their tenure in classrooms is over.Footnote2

In their influential publication of 2005, Materialities of Schooling, Martin Lawn and Ian Grosvenor argued that studying “the ways that objects are given meaning, how they are used, and how they are linked into heterogeneous active networks, in which people, objects and routines are closely connected” allowed richer historical accounts of schools and schooling. They additionally observed that objects change over time. Not only do classroom objects age physically, but changes in human perception lead to a “shift from objects crucial to innovation, into objects misused or reused in new contexts and finally into a lost or dislocated existence.”Footnote3

Attention to the lifecycle of objects was stressed by Belgian historians in studies of the school desk.Footnote4 They promoted a biographical approach as an alternative to earlier approaches, such as those influenced by Foucault where the desk was viewed primarily as an instrument of discipline. With a biographical approach, the desk might be viewed as passing from intellectual property to device, to the subject of debate, to factory article, shop item, showpiece, classroom object, museum piece, furniture in other settings, perhaps ultimately firewood, discarded in one way or another.

School desks have featured in a number of articles and chapters adopting a materialities framework. In 2005, Spanish historian of education Pedro L. Moreno Martínez focused on desks, tables and chairs as the most representative items of school furniture. He argued that development of benches, “desk-units” and separate tables and chairs in Spanish schools over almost 100 years, in their various forms, were primarily influenced by changing ideas of hygiene and pedagogy.Footnote5 In Italy, Marta Brunelli and Juri Meda explored the evolution and use of the school desk over a similar timespan. They referenced the attention paid to the desk as a crucial element of school furnishings “first as a tool aimed to arrange spaces that were functional for classroom activities; second, as the outcome of hygienic discourses concerning both the health and the disciplining of young bodies; and, finally, as an object of dedicated industrial production.”Footnote6 Their paper argued the multifunctional use of the desk in Italian classrooms where it supported class activities, facilitated classroom management, maintained correct body posture and additionally functioned as “gymnastic equipment.”

The materialities of schooling encompasses a broad field of which studies of desks, tables and chairs represent only part. The topic has featured in conferences, special journal issues and edited books.Footnote7 Inés Dussel, in a recent discussion of the implications of the material turn for the historiography of education, points to historians looking at buildings, classrooms, desks, blackboards, notebooks, visual aids and uniforms.Footnote8 The field invites much further consideration. Anthony Di Mascio, for example, in 2012 pointed to an absence of consideration of material culture in Canadian educational historiography.Footnote9 The same absence may still be observed in Australian historiography.

Australian historian Julie McLeod introduced papers addressing “Space, Place and Purpose in Designing Australian Schools” in 2014. She argued that the spatial and material dimensions of schools and educational practices shaped the experiences and formation of teacher and student identities.Footnote10 The papers, however, were primarily concerned with architectural and spatial design rather than objects in classrooms. In carrying out research for this present article, the author found no recent address to desks, tables and chairs in Australian classrooms on the part of educational historians. An earlier publication, Sydney and the Bush by Jan Burnswoods and Jim Fletcher, made some reference to furniture and remains a valuable source of images that document furniture, classrooms and buildings.Footnote11

In addition to furniture itself, accessed through images, plans and surviving objects, sources that have informed this paper include New South Wales Department of Education documents held at State Archives, Departmental publications, reports written by Herbert Oxford for the Department and the Minister of Education, and the texts of conference addresses given by Oxford to various audiences. Material held at State Archives is invaluable but scattered as it is amongst various record series it is sometimes difficult to locate. Minutes of the Furniture Centre Planning Committee, 1964–1965 and those of the 1980s Furniture Committee of the School Building Research & Development Group, for example, are valuable document sets, but any surviving minutes of the Furniture Review Committee that operated in the 1950s and 1960s have not been located, despite diligent enquiry.Footnote12

Benches, forms, desks, tables and chairs became the most obvious objects within the classrooms of modern nation-states as those states began to provide education to increasing percentages of the population from the early nineteenth century and through the twentieth. Tables and chairs, work surfaces and seating remain of prime importance in the learning spaces of today’s schools. The paper begins with an overview of the earlier history of school furniture provision in New South Wales before turning to the post-war decades, from the late 1940s to the 1980s.

Furniture Provision, Late Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries

Changing designs and provision of furniture to New South Wales schools from the late nineteenth century to the present day accompanied changing ideas of pedagogy and physical health. Towards the end of the nineteenth century, educational reformers advocating widespread changes to schooling were critical of the seating that characterised the larger state schools throughout the Australian colonies (after 1901, states of the new Commonwealth). They vehemently attacked the type of education such furniture accompanied and the effect that the seating had on the physical well-being of the child.Footnote13 As Burnswoods and Fletcher pointed out, that furniture reflected attitudes to pupil behaviour where children were required to sit still while being drilled in basic subjects. It was impossible for them to be active, and essential they be quiet and orderly.Footnote14

Yet, sources from both New South Wales and Victoria indicate that professionally designed galleries of long desks and forms were considered innovative in the 1850s and 1860s, and certainly a contrast to the many simply constructed huts, perhaps with no ceiling, dirt floors and simple bench seats, which served as schoolrooms throughout the rural settlements of the colonies. Large schoolrooms were designed to seat all children attending, unless numbers allowed separate rooms for boys, girls and infants. Inside the room, galleries consisted of parallel rows of long desks and forms, the front row on the floor and each successive row raised a few inches higher.Footnote15 Some designs included back supports, for example those in a gallery displayed at the Victorian State School Exhibit at the Melbourne International Exhibition in 1880.Footnote16 Others had no back support, as indicated by the criticism of the New South Wales commissioners in 1904.Footnote17

The movement for educational reform, referred to as “New Education,” grew in significance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries throughout the countries of Europe, the United Kingdom, North America, the colonies and former colonies of European empires and in developing countries. New ideas and practices were disseminated through published books and journals, national and international meetings and exhibitions and educators who travelled to observe the educational systems of other countries.Footnote18 In New South Wales the desire for change led to the appointment in 1902 of two commissioners, George Handley Knibbs and John William Turner, who travelled overseas to observe schools and schooling and subsequently recommended changes to the education system. Their brief included “Material Equipment,” which covered school buildings, furniture and teaching materials. Knibbs was very critical of the seating provided in New South Wales, arguing that it produced myopia, spinal curvature and, in combination with crowding, poor ventilation and temperature control, represented a serious threat to the “physique of the Australian people.” He called for desks and seats that supported the back of the growing child, that allowed a proper distance between eye and paper and were proportional to the height of the child. Pedagogical considerations indicated that desks should be arranged to allow each child to move in and out of the seat without disturbing others and, additionally, they needed to be movable. It was important that the desks be part of a separate classroom for each class group, unlike the existing situation of large schoolrooms containing several groups and designed for supervision of pupil teachers by a headmaster.Footnote19

At the educational conference in April 1904, Knibbs and Turner’s recommendation for dual desks (desks for two children) was discussed.Footnote20 James Wigram, government architect to the Department of Public Instruction, favoured Canadian designs as alternatives to the Swiss model approved by Knibbs and Turner but further advised that an Australian design be developed and locally produced by the Department’s existing workshops. That would reduce costs. Turner endorsed this proposal: “Let us make them ourselves from our own timber. Let us improve on the Swiss and on the Canadian patterns,” he exclaimed.Footnote21

With these words, and a subsequent motion, the Conference ushered in a long period in which the New South Wales Department of Education would not only design and produce its own furniture from Australasian timbers, but would remain explicitly proud of its Furniture Workshops and the functioning of its centralised procedures for provisioning the schools of the state.

In 1904, the long school desks and bench seats were being produced in a carpentry shop located on Cockatoo Island in Sydney Harbour. Boys from the industrial school ship, Sobraon, also under the authority of the Department of Public Instruction, were apprenticed to make furniture, one aim being to give the boys a useful trade. After 1904, the shop began production of the new dual desks, although, due to restrictions of the site, desks were also produced by outside firms, as were all of their cast iron supports, or “standards.”Footnote22

Gradually new schools were furnished with dual desks. When a new school was opened at Guildford in 1905, for example, an enthusiastic report noted that seating throughout consisted of dual desks and seats with backs, suiting the height of children.Footnote23 Rooms in older schools were remodelled and galleries replaced by separate classrooms containing desks. However, the new desks met only some of Knibbs’s recommendations. Although they were produced in several sizes, they were not designed to be portable. Instead, they were fixed to the floor in rows, produced with the seat of one attached to the table of the one behind. As such, they became a dominant feature of classrooms for decades and eventually the target of criticism due to their inflexibility.

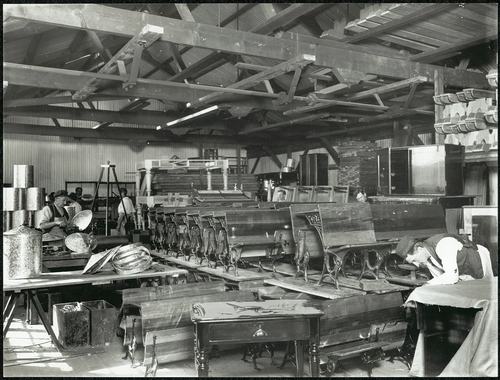

The Sobraon ceased to operate in 1911, and the Commonwealth Government took over Cockatoo Island for naval construction. The Department of Public Instruction purchased a factory at Drummoyne, located on the Parramatta River, west of the city, for the purpose of producing school furniture, staffed by employed workmen.Footnote24 The School Furniture Workshops operated at Drummoyne from 1913 to 1980. For some time, the factory continued to make old-style long desks and forms alongside new dual desks, indicating a lengthy transition period. The actual style of the dual desk is pictured in a photograph of furniture ready for dispatch in 1913 ().

Figure 1. Desks stacked at the Furniture Workshops, Drummoyne, 1913.

By 1919 the Workshops were also producing what were called “Montessori tables and chairs,” in several sizes. This followed enthusiastic promotion of Montessori education by Martha Margaret Simpson, Infants Mistress of Blackfriars Practice School, lecturer at Sydney Teachers College and the first female inspector in New South Wales. Simpson believed that furniture was crucial for new principles and methods of teaching. She insisted that children should be able to move about freely and classrooms contain small tables and chairs that children could lift and carry. The flexibility of this furniture allowed arrangement and rearrangement to cater for different kinds of activity.Footnote25 Her recommendation for the Department to produce tables and chairs made of light, cheap wood for infant schoolrooms was acted upon, attested by orders for this furniture.Footnote26

While tables and chairs were supplied to increasing numbers of infants’ classrooms (Kindergarten, 1st and 2nd classes) from 1920, it was not until the late 1940s that they were recommended and produced for all classrooms in primary and secondary schools. That prolonged transition represents a very gradual uptake of the ideas and practice of New Education and progressive education. In the 1920s, reform of education stalled in New South Wales and the Depression of the 1930s meant little money was available to refurbish the public schools.Footnote27 Reforming educators, however, remained interested in furniture and would have been aware of the American publication, School Posture and Seating by Henry Eastman Bennett (Citation1928). The term “ergonomics” was not used by Bennett but his aim was to make a “contribution to the science of sitting and seating.”Footnote28 Using statistical studies, he considered optimal seat heights, desk heights, spacing between seats and desks, and back support. He argued that school furniture had to be movable, in contrast to the tradition of screwing seats to the floor.

Educators from many countries increasingly favoured separate tables and chairs as necessary for modern schooling. Dual desks, once hailed as modern innovations, became the target of criticism. In Australia, a post-war booklet from the Australian Council for Educational Research, School Buildings and Equipment (1948) advocated the replacement of fixed desks. Classrooms designed for activity needed furniture that was light, strong and movable, allowing the floor to be quickly and easily cleared for varied activities. The desks in most schools, the authors continued, were a hindrance to any activity programme and their dark, varnished surfaces were unpleasant. Light coloured wood, such as Victorian ash, was pleasing in appearance and restful to the eyes while well designed chairs were important for physical comfort and skeletal development.Footnote29

Furniture Provision after the Second World War and the Role of Herbert Oxford

In New South Wales, the end of the war saw a rising demand for new school furniture amidst a serious shortage of building materials. In the event, it was the inability to obtain cast iron standards, the side supports for dual desks, that precipitated replacement of desks by timber tables and chairs in 1949.Footnote30 By this time, the huge challenge of accommodating an increasing population of children was unmistakable. Herbert Oxford, appointed to supervise the Furniture Workshops, was an educator up for a challenge.

Born in 1903, Oxford attended Kurri Kurri Public School and East Maitland Boys High School. After he qualified as a teacher in 1921, and obtained a Diploma of Economics in 1922, he taught manual arts in country schools before his appointment in 1928 as lecturer in manual training at the newly established Armidale Teachers College, located in the New England region of New South Wales. In Armidale, he organised sporting, literary and social activities at the College and was involved in the same pursuits in the wider community. He gained a reputation for his organisational ability, not least as President of the Armidale Branch of the Australian Labour Party.Footnote31

Educators who were frustrated by the State’s failure to implement progressive ideas and practices in the education it offered were often labelled as radical in the 1930s. Some watched the vast changes taking place in Soviet Russia with keen interest. Oxford was one such educator. In 1942, he gave a paper, “Freedom from Want,” to a popular society in Armidale. Discussing future development, he praised the Soviet Union and its attempts to replace capitalism with a planned socialist economy.Footnote32 When Oxford contested the Federal seat of Armidale in the 1943 elections, it is not surprising that he had to overtly refute claims that he was a communist. Yet, later, he was praised for an extraordinary campaign that just missed out on unseating the Country Party’s J. P. Abbott. In 1944, Oxford contested the State seat for Labour and again was narrowly defeated.Footnote33

Then, in that hopeful period of post-war Reconstruction, Oxford was seconded to Head Office of the Department of Education in Sydney.Footnote34 He assisted the Minister for Education, Robert Heffron, in the development of the Labour government’s post-war education policy, presented to the public as Tomorrow is Theirs: The Present and Future of Education in New South Wales.Footnote35 This book noted how important it was that buildings and facilities showed “progressive improvement” and kept pace with advances in school purpose and practice.Footnote36 As Heffron continued to preside over “an era of educational expansion and experiment,” in the words of his biographer,Footnote37 Oxford stepped into the position of supervisor of the design, production and distribution of furniture to the ever growing number of primary and secondary schools. In this role, Oxford grasped an opportunity that would transform the classroom and the furniture in it, slowly but surely altering the dialectic between children and teachers and the material objects of their learning spaces.

The Furniture Workshop at Drummoyne was struggling to obtain materials. With cast iron standards unavailable, Oxford began his role by organising an anthropometric survey with the aim of designing movable classroom chairs and tables for all infants, primary and secondary classrooms. The survey was carried out by the School Medical Service and involved taking five body measurements of 12,000 primary and secondary children. Oxford, over many years, claimed that “the most important fact revealed by the survey was the need for more than one size of furniture to be supplied to each class in order to provide for differences in the size of children.”Footnote38

Results of the survey went to the Department of Education’s Head Office where draughtsmen designed a new range of furniture. Preparation was made for large scale production at Drummoyne although it was realised that contracts with outside firms would also be needed. It was decided to manufacture eight sizes of chairs and matching tables. Most of the chosen designs in the early 1950s used only timber with the chair seats made of slats. Some chairs for infant classrooms used tubular aluminium and timber. Infants and primary rooms were supplied with dual tables and matching single chairs while secondary schools had single tables and chairs.Footnote39

As the 1950s proceeded, extensive changes occurred within the workshops in order to supply increasing numbers of children and new schools. Oxford travelled overseas in 1952, observing school buildings, equipment and maintenance in England, Scotland, Europe and the United States. Reporting to Heffron, he stressed the importance of the Department continuing to observe postural requirements and doing everything possible to provide appropriate sizes of furniture for each class. However, he recommended that the eight sizes of chairs and tables be reduced to six. Abandoning production of the dual desk had proved a wise decision, he confirmed, as movable tables and chairs were favoured throughout the countries visited. Oxford made recommendations in regard to machinery, timbers and lacquers, the use of metal in the production of chairs and tables, the possible use of plywood for chairs, and of sheet plastic such as Formica for table-tops.Footnote40

Oxford noted that no other education authority in the countries visited possessed their own furniture workshops. New South Wales was fortunate, he declared, in being able to design and construct furniture to its own specifications, ensuring the standard of workmanship. Oxford, and the Department more generally, remained proud of their centralised furniture establishment throughout the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. According to Oxford in 1952, many administrators envied the facilities he described, but in the United States he was told this situation would be considered too “socialistic,” and in England that unions would object.Footnote41

Oxford travelled to New Zealand in 1955 to observe school maintenance and provision of furniture. He noted that furniture was primarily made by private enterprise and concluded that New South Wales was considerably ahead in its attention to postural requirements. Like New South Wales, New Zealand was considering metal components for tables and chairs.Footnote42 It is probable that some of Oxford’s observations in New Zealand regarding procedures for ordering, dispatch, taking delivery of furniture in schools and maintenance informed the working of the Furniture Services Branch set up later that same year in New South Wales.

In 1949, land and large sheds were acquired at Sheas Creek, St Peters, and used for storage. This industrial site, 12 kilometres by road from the Drummoyne workshops, became known as the Furniture Centre. In 1953, the Public Service Board set up a Committee to enquire into the reorganisation of the Furniture Workshops and the Centre. While the Workshops at Drummoyne continued as the main production factory, the Centre would function as an assembly and finishing factory, a storage facility and the point from which furniture was dispatched. At both sites, buildings were enlarged, new machinery installed, and new processes introduced. A third body, the Furniture Services Branch, was established in 1955 in the grounds of Five Dock Public School, close to Drummoyne, to take responsibility for processing orders from schools, keeping records of furniture in all the schools of the State, and attending to maintenance and repair. The manager of the Workshops at Drummoyne had previously been in charge of production, distribution and maintenance but now each of the three sections had their own manager and their own areas of responsibility.Footnote43 Oxford claimed that the reorganisation resulted in “one of the largest furniture factories in the Southern Hemisphere, a re-vitalized establishment, a marked increase in output, a definite fall in the costs of production, and an obvious improvement in staff morale”Footnote44 ().

Figure 2. Rubbing down furniture after it has been sprayed and dried at the Furniture Centre.

Reorganisation meant that the Workshops could manufacture a much greater percentage of school furniture than they had in the early 1950s when it was necessary to make use of private contractors. This percentage grew each financial year, and by 1962/63 the Workshops were producing most of the furniture.Footnote45 After 1955, the design of all furniture items was reviewed and new designs developed.Footnote46 As Oxford had advised in 1952, the eight sizes of chairs and tables were reduced to six. Carefully preserved detailed plans and measurements for the newer tables and chairs, along with other items of furniture, survive in the archives.Footnote47 A Furniture Review Committee consisting of Oxford, the managers of each section, staff inspectors and the Schools’ Architect was set up in 1955 and continued to operate through the 1960s, to discuss, approve and then evaluate the trial of new items of furniture and modifications to existing designs. Discussion, design, manufacture, trial and subsequent introduction to classrooms of adjustable furniture for students with disabilities constituted one example of this Committee’s influence on changing classroom materiality.Footnote48

By 1959, comprehensive catalogues for the use of school administrators listed and illustrated the many items of furniture available for general and specialist classrooms. Oxford’s ideas on the importance of posture introduced the listings:

Considerable importance is attached to classroom seating because no child should sit on a chair which is too high. There are sound anatomical reasons for this apart from the advantages which accrue educationally from sitting in comfort … The various measurements of the six sizes of chairs in use in schools are based on the posture survey of some twelve thousand pupils in 1949.Footnote49

Precise numbers were provided for how many chairs of each size could be supplied to a classroom for 40 children. Second grade, for example, would be provided with 12 Size B, 22 size C and six size D chairs and matching tables. Sixth grade would receive six size C, 16 size D and 18 size E chairs. High schools were provided with sizes E and FFootnote50 ().

Figure 3. Six sizes of chairs supplied to NSW classrooms in 1959.

Figure 4. Tables supplied to NSW classrooms in 1959.

Throughout this period, while new schools were furnished with tables and chairs, many older schools still contained dual desks screwed to the floor. Replacement proceeded gradually, as witnessed by children who attended schools in the 1950s and 1960s. In 1964, the Officer in Charge of the Furniture Services Branch estimated that 40% of ordinary classrooms still had dual desks.Footnote51 Undoubtedly, an older classroom with fixed desks all the same size contrasted with a classroom of brand new tables and chairs that could be arranged for varied activities. Many children experienced both types of classroom as they proceeded through schooling and, therefore, in retrospect, recall experiences influenced by different furniture and different layouts. Teachers too were influenced by the furniture and how much agency they possessed in its utilisation.

In 1963, the Department celebrated 50 years of production by the Workshops. A booklet, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, almost certainly written by Oxford, was published to mark the occasion. The cover featured the newest furniture being supplied to secondary schools: single tables with metal frames and synthetic veneer surfaces (). Primary schools continued to receive dual tables made of wood and chairs of wood and plywood. The book gave an overview of the history of the Workshops and was accompanied by photographs to illustrate a story of achievement and progress. It foreshadowed new plans for the provision of furniture in the context of growing population, extension of the high school course to six years, and increasing percentages of students completing high school. The aim was to integrate all three furniture establishments, Workshops, Centre and Services Branch, into a single factory located at Smithfield, in western Sydney.Footnote52

Planning a New School Furniture Centre

Oxford travelled overseas again in 1963, this time in the company of the Secretary of the Department of Education and a senior representative of the Public Works Department. Tasked to observe the latest processes and techniques in school furniture production and supply, this undertaking was in preparation for planning the new, integrated Centre at Smithfield for which land had already been acquired.Footnote53

Between February 1964 and September 1965, Oxford chaired a Furniture Centre Planning Committee which attempted to define the furnishing requirements of schools 15 years in the future and draw up plans for the new factory. The members included the Secretary of the Department, the managers of the current Workshops and Centre, and representatives from the Public Service Board, the Government Architect’s Branch and the Public Works Department. All members of the Committee travelled to Smithfield to inspect the proposed site and were positive about its potential.Footnote54 Visits to the Workshops, Centre and Services Branch were made. Oxford noted how difficult it was to predict future furniture requirements and referenced factors likely to influence them: increased enrolments; extra classrooms for specialist and occasional use; changing patterns of population, new residential areas, home-units and density housing; an extra secondary year; a greater percentage of secondary students staying for the full course of high school; the continued replacement of dual desks; a growing number of chairs and tables needing repair or replacement. He concluded: “From 1975, there will be a marked increase in furniture requirements equivalent to twice the 1963 figure.”Footnote55

During 1965, architectural plans for the new centre were drawn up, and Oxford prepared a final report for the Minister of Education, the Public Service Board, Treasury, and Department of Public Works.Footnote56 It would, however, be a further 15 years before the new centre was operating at Wetherill Park on the land originally described as Smithfield.

Herbert Oxford remained active in his leadership of the three furniture establishments until his retirement in 1967 at age 63.Footnote57 His ideas and recommendations continued to underpin furniture provision for another two decades, while his writing on the importance of “posture furniture” was confirmed by the growing prominence of the new scientific field of ergonomics.

Ergonomics

Inspired by his overseas trip in 1963, Oxford initiated a new survey of children’s physical measurements. This survey aimed to provide data for the design of furniture for specialist subjects and for tertiary students in addition to modifying existing designs. Over 13,000 students from primary, secondary and tertiary institutions were measured. Eleven measurements per student were taken by trainee physical education teachers and their lecturers.Footnote58 These measurements, unlike those of 1949, were made widely available. They were compared to historical figures from 1908 and surveys in other states and countries.Footnote59

Oxford presented the survey data in three papers for audiences beyond the Department of Education. These papers validate Oxford as a leader in the field of ergonomics as it related to seating and posture and a leading Australian authority on providing suitable furniture for school children. “The Problem of Misfit Furniture” was presented to the Ergonomics Society of Australia and New Zealand in August 1966. Here, Oxford stressed the potential harm of unsuitable furniture, including mismatched chairs and tables. Immediate effects manifested themselves in excessive fatigue, undue wriggling, lack of concentration and requests to go to the toilet: “In short, the child’s ability to learn would be impaired.”Footnote60 Longer term effects included life-long postural damage. Chairs and tables could only be regarded as satisfactory if they played a maximum role in facilitating learning.Footnote61 After retirement, Oxford gave a paper in Zurich at an international symposium on sitting posture, subsequently published in 1969 as “Anthropometric Data for Educational Chairs” in Ergonomics, a journal with international coverage. The chair, Oxford argued, had to satisfy three requirements: postural, comfort and educational. He explained that a chair “satisfies comfort and educational requirements when the sitter can sit for long periods without becoming aware of the chair.”Footnote62 In 1971, he addressed the Educare International Exhibition Conference in Melbourne. To meet postural requirements, he stressed, the chair had to enable the child to sit correctly, against the backrest, with feet flat on the floor, no undue pressure on the lower thigh behind the knee and with space behind the calf. As for the table, the practice of including a storage shelf needed to be abandoned as it meant that the table was too high if adequate knee room was also provided. In New South Wales, secondary teachers had applauded the elimination of the shelf which had, in the main, only been used for rubbish. Elimination of the shelf allowed height to be reduced.Footnote63

“Do furnishings matter?” asked Oxford, his answer stressing “the importance of the human relationship which exists between the pupil and the chair, table or bench that he uses.”Footnote64 A child, he said, should never feel imprisoned by a chair or table. On the contrary, the child had to be able to take up different positions on a chair, without losing comfort. Teachers could make more use of the flexibility that movable chairs and tables represented. Oxford’s words indicate explicit awareness of the dialectic of people and things occurring in the classroom.

Flexible Learning Places: The 1970s

For decades, educators throughout the world had been stressing the advantages of movable tables and chairs as necessary for modern classrooms. The 1970s witnessed an increased emphasis on flexibility in classrooms, or “learning places” and “learning spaces” as they were often called. Flexibility was no longer just about moving chairs and tables around, but meant providing a range of seating and work surfaces and options for simultaneous but varied activities in the one space. In 1977, for example, the authors of Planning Flexible Learning Places wrote that the essence of a “modifiable environment” was that furniture could be easily moved and rearranged. In addition, seating could include a combination of chairs, cushions, carpeted floors, platforms, steps, benches, lounge furniture, bean-bag chairs and even inflatable chairs and rocking chairs. It might not even be necessary to provide conventional chair–desk arrangements for every child to occupy at the same time.Footnote65

English architect David Medd, in an influential study of design, production and provision of school furniture across several countries, also stressed changing ideas in education and their influence on the classroom:

[T]he formality of the set piece interior has given way to what, by comparison, must seem to some a pattern of ever changing confusion, when furniture is being constantly moved about, put to different purposes and frequently overloaded with work in progress and display.Footnote66

Medd concluded that a greater variety of furniture was needed in classrooms where children had frequent opportunities to move around and where all were not seated at the same time. In contrast to Herbert Oxford’s strong commitment to providing more than one size of chair and matching table to each classroom, Medd argued that three or four sizes of furniture in one room were hard to defend. Different sizes could become mis-matched and grouping tables of different heights was problematic. Medd favoured “a well-judged distribution of a carefully selected single size.”Footnote67

In New South Wales, the design, production and supply of furniture continued to be provided centrally by the three furniture establishments. Annual reports for the late 1960s and the 1970s demonstrate that the Department of Education was very aware of the transnational interest in increased “flexibility” and what this might mean for school building design and classroom furnishings. The 1968 report claimed that new schools were designed for “maximum freedom for the organization of classes and advanced methods of teaching” and 1972 was declared a year of “marked experimentation in design with the general aim of providing more flexibility in teaching methods.”Footnote68

The number of pupils in primary and secondary schools continued to grow and the need for new schools continued. In 1965 there were 653,431 pupils enrolled in state schools. By 1974, there were 777,860, an increase of 19 per cent. By this time, the numbers of children in primary schools had levelled out, but secondary school students were increasing, due to growing retention rates from first-year enrolments through to the fourth year and then to the sixth year of the high school course. In the early 1960s, the number of new classrooms to be furnished averaged 1,000 per year. In 1969, there were 1,309 new classrooms, in new schools and existing schools, that required furniture.Footnote69

A School Buildings Research and Development Group was established in 1965 as a unit of the Public Works Department with representation from the Department of Education. This body planned and designed new schools.Footnote70 In 1975, it was reported that: “Senior members of the staff of the School Furniture Complex” worked closely with the Schools Research and Development Group.Footnote71 Although work on the new factory at Wetherill Park did not begin until 1976, the three furniture establishments of the 1950s and 1960s were now evidently referred to as the “School Furniture Complex.” The Research and Development Group, including staff from School Furniture, probably replaced the former Furniture Review Committee.

School Furniture Complex, Davis Road, Wetherill Park

Building the new School Furniture Complex, Herbert Oxford’s vision for the future was realised very slowly. Construction began in 1976 and operations moved to 3–7 Davis Road, Wetherill Park, in 1980.Footnote72 The estimated cost in 1978 of this large factory, then under construction, was A$12,000,000.Footnote73 This was an expensive undertaking on the part of the State.

The complex manufactured an increasing range of furniture for the State schools and also supplied non-government schools and office furniture for government departments. Continuing a trend of the 1970s, a growing percentage of furniture was made externally to specifications, by companies such as Sebel, a business that remains proud of its history of replacing wooden chairs in schools with polypropylene.Footnote74 Furniture produced externally was stored at the complex before being supplied to schools. The School Servicing Division arranged repair of existing furniture, with a team of officers based throughout the State. The complex included a large showroom and additionally sold furniture no longer required in schools to the public. In this way, superseded models of chairs and tables found a place in family homes as children’s furniture.Footnote75

The Furniture Sub-Committee of the Schools Building Research and Development Group met regularly at the complex to discuss new designs of furniture, arrange trials of prototypes in schools and evaluate the results. In 1985, for example, it trialled a larger size of secondary school table and in 1988 developed new designs for tables and chairs for Kindergarten to Year 6. Computer tables and work-stations, and furniture requirements for the integration of students with physical disabilities into regular classrooms were two of the many issues addressed by this committee.Footnote76

A Furniture Complex brochure illustrates a range of seating being supplied to schools and government departments. For schools, there were five sizes of moulded plastic chair, in five different colours. They were graded A–E, as were their wooden predecessors, the range suiting small children through to adults. The brochure explained that “chair and table heights are co-ordinated for correct posture.”Footnote77 In addition, upholstered seats and lounge chairs were available in separate sizes for primary and secondary students, along with casual stools.

After 20 years in the planning and built at considerable expense, the School Furniture Complex would operate for little more than a decade. State elections in 1988 saw the incoming Liberal-National government, led by Nick Greiner, promise to cut state expenditure through privatisation and the sale of state property. This included centralised services provided by the Department of Education along with property occupied by the Department. The Furniture Complex was an early target. In the face of potential closure, morale at the complex deteriorated. An investigation into alleged misconduct on the part of senior management reported in 1989:

The Complex is a typical factory where factions and petty jealousies thrive, “foreign orders” are not uncommon and “factory floor gossip” is rife. This situation has been exacerbated recently with the spectre of privatisation hanging over the Complex. A common statement made by employees at the Complex to the auditors was that morale is presently at rock bottom.Footnote78

Over the next few years, many properties occupied by the Department of Education were sold. The sales formed part of a large scale re-organisation of education in which regional centres and individual schools took over functions that had previously been carried out centrally. The sale of property was seen as a means of financing reform which followed the Scott Report (1989) and the Carrick Report (1989).Footnote79

Despite opposition from trade unions, the Teachers Federation, the Public Service Association and parent associations, privatisation and subsequent sale of the School Furniture Complex proceeded. The business was taken over by a private firm in late 1993 and sold in October 1994. The site and buildings were sold on 21 August 1996.Footnote80

With this closure, the design, production, testing and supply of furniture to schools ceased to be a state service to education and became part of the market economy. School principals and their executive staff were given much more control over their respective school budgets, with auditors to monitor expenditure. As part of this responsibility, individual schools became responsible for the purchase of furniture from Department- endorsed private suppliers.

Conclusion

In appearance, classrooms in New South Wales schools in 1990 looked very different to those of 1949. Of course, even in the 1940s infant classrooms differed to primary classrooms which differed to secondary classrooms. In general, though, primary and secondary classrooms were dominated by two-seater wooden desks with cast iron supports, attached firmly to the floor and arranged in rows facing the front of the room. Whether the classroom was a pleasant, friendly place, where children enjoyed learning and felt safe might have depended more on the teacher or teachers than the furniture in the room. In any case, an acceptance of new and evolving ideas and practices of teaching and learning made the once innovative dual desks obsolete.

By 1990 a definite shift had occurred in educational ideas relating to the environment of the classroom. Primary classrooms, now referring to years Kindergarten through to Year 6, explicitly aimed to be friendly, bright and stimulating spaces that catered for a variety of activities. In some, the wooden tables for two children made in the 1950s and 1960s remained, arranged variously but often in groups providing for four or six children. Newer classrooms featured tables made from synthetic materials and coloured polypropylene chairs. In secondary schools, where classes and teachers moved from room to room during each day, there was likely to be less personalisation of the individual room. Many secondary schools retained the single wooden tables and chairs that had been supplied in the 1950s and 1960s, or the slightly later metal-framed tables and chairs. Sometimes these would be grouped in square or rectangle formations, or arranged in a U shape; in other rooms they might face the front, more traditionally, in pairs or other combinations.

The decades from the late 1940s to the 1980s witnessed the complete change-over from desks to chairs and tables. Designs, materials used, construction techniques, and production scale evolved throughout the period. One of the most interesting features of the design, production and supply of furniture for the state schools of New South Wales, was the centralisation of these functions within the Department of Education. Herbert Oxford maintained that this situation was exceptional as he did not observe anything similar in his travels. David Medd, in 1981, discussed other jurisdictions where central authorities had substantial responsibility for the design and supply of furniture but, even in comparison with these examples, New South Wales appears distinctive, particularly in the longevity of its total oversight through the twentieth century until the 1990s.Footnote81 Oxford was proud of the structure that he developed in the 1950s where three establishments – Workshops, Centre and Branch – constituted one of the largest furniture factories in the southern hemisphere.

Herbert Oxford contributed immensely to the organisation of the design, manufacture and supply of furniture to the schools of New South Wales from 1949 to 1967 and beyond. He consistently promoted the benefits of centralised design and manufacture by government owned workshops, a point of view destined to became obsolete under neo-liberal policies of the 1990s. His contribution to schooling more generally was considerable. His anthropometric surveys were and remain important sources of data. His interest in providing ergonomic furniture at a time when that field was in its infancy is significant. Oxford was concerned with more than the “nuts and bolts” of materials, techniques, and processes used to furnish the classrooms. For him it was also about the relationship between the child, the chair and the table. Oxford influenced the look, the feel, the smell and the layout of the classrooms that children inhabited from the 1950s and for decades after. As such, to study Oxford and the provision of school furniture in New South Wales in the period which he influenced provides insight into the dialectic of people and things operating and evolving in the classrooms of the State.

Interest in materialities on the part of educational historians has opened up new fields of inquiry. Understanding design, production and supply of furniture to schools and its utilisation in the classroom allows the historian to approach questions mentioned in introducing this paper: how objects are conceived and given cultural meaning through design, how they are produced in complex production facilities, how they arrive in schools, how they affect the teaching and learning that takes place and how they influence memories of school and what happens to them when no longer needed. This paper has focussed on classroom chairs and tables in New South Wales, particularly in the context of unprecedented population growth after the Second World War and changing philosophies of teaching and learning in the same period. It makes a contribution to an absent field of study in Australia and contributes to a wider materialities scholarship regarding school furniture across many countries. Further research is indicated for the history of school furniture in other Australian states in order to enrich the understanding of classrooms and schooling both in the past and the present day.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Dorothy Lynette Kass

Dorothy Lynette Kass is an honorary postdoctoral fellow with the Department of History and Archaeology at Macquarie University, Australia. She worked as a librarian in university and secondary school libraries before completing a PhD in history. She is an active member of the Australian and New Zealand History of Education Society (ANZHES) and editor of the online Dictionary of Educational History in Australia and New Zealand (DEHANZ). She is the author of Educational Reform and Environmental Concern: A History of School Nature Study in Australia (Routledge, 2018) and articles published in journals of history and educational history.

Notes

1. Stanford University, Department of Anthropology, “Materiality.”

2. Lawn and Grosvenor, “Introduction,” 7.

3. Ibid.

4. Herman et al., “The School Desk,” 97ff; Depaepe, Simon, and Verstraete, “Valorising the Cultural Heritage of the School Desk,” 13–30.

5. Moreno Martínez, “History of School Desk Development,” 71–95.

6. Brunelli and Meda, “Gymnastics between School Desks,” 178–9.

7. For example: Lawn and Grosvenor, Materialities of Schooling; Burke and Grosvenor, School; Burke, Cunningham, and Grosvenor, “Putting Education in its Place”; Smeyers and Depaepe, Educational Research.

8. Dussel, “What Might a Material Turn to Educational Histories Add to the History of Education?”

9. Di Mascio, “Material Culture and Schooling,” 82.

10. McLeod, “Space, Place and Purpose,” 133–7.

11. Burnswoods and Fletcher, Sydney and the Bush.

12. In 2022, New South Wales State Archives became part of a larger body, Museums of History New South Wales. Materials cited here use the abbreviation NSWSA.

13. For example, George Handley Knibbs and John William Turner, in their 1904 report: New South Wales, Legislative Assembly, Commission on Primary, Secondary, Technical, and Other Branches of Education, Interim Report of the Commissioners, Summary, 63–4, 96; Main Report, 427ff. Hereafter referred to as Interim Report.

14. Burnswoods and Fletcher, Sydney and the Bush, 84.

15. Blake, Vision and Realisation, 100–1; International Exhibition, Victorian State School Exhibit; Burnswoods and Fletcher, Sydney and the Bush, 58–9.

16. International Exhibition, Victorian State School Exhibit.

17. Interim Report, Summary, 63–4, 96; Main Report, 427ff.

18. The New Education movement of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries has been widely discussed by educational historians. Its influence in Australia was discussed by Kass, Educational Reform and Environmental Concern, 4–7, 71ff.

19. Interim Report, Summary, 63–4, 96; Main Report, 427ff. Quotation from 64.

20. New South Wales, Department of Public Instruction, Conference of Inspectors, Teachers, Departmental Officers, and Prominent Educationists, 204–16.

21. Ibid., 212.

22. New South Wales, Department of Public Instruction, Three Years of Education, 39–40; “Furnishing Our Schools,” 30; New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 1.

23. Cumberland Argus and Fruitgrowers Advocate, August 30, 1905, 2.

24. New South Wales, Department of Public Instruction, Three Years of Education, 39–43; “Furnishing Our Schools,” 30; New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 1.

25. Simpson, Report on Montessori Methods, 10, 35.

26. NSWSA: NRS 3829 [5/17670], Dispatch documents, May 19, 1919 and attached applications for furniture by A. Baldwin.

27. Turney, “Continuity and Change,” 50; Dunt, Speaking Worlds, 80; Hyams and Bessant, Schools for the People, 162.

28. Bennett, School Posture and Seating, iv.

29. Australian Council for Educational Research, School Buildings and Equipment, 43, 56–7.

30. New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 2.

31. NSWSA: NRS-15320-1-44, Oxford, Herbert William; NSWSA: NRS 12395-1-[8/2693], Oxford, Herbert William; Newspaper articles about Oxford located through the National Library of Australia’s TROVE database.

32. Oxford, Freedom from Want.

33. Armidale Express, July–September 1943; May–June 1944.

34. NSWSA: NRS-15320-1-44, Oxford, Herbert William; NSWSA: NRS 12395-1-[8/2693] Oxford, Herbert William.

35. Heffron, To-Morrow is Theirs.

36. Ibid., 124.

37. Carr, “Heffron, Robert James (1890–1978).”

38. Quotation from Oxford, “Problem of Misfit Furniture,” 3. Survey described by Oxford in “Problem of Misfit Furniture”; “Anthropometric Data for Educational Chairs”; and “Importance of Human Factors.” Also described in 1954 film, As the Twig is Bent.

39. As the Twig is Bent.

40. Oxford, Report on School Buildings.

41. Ibid., B30.

42. Oxford, Report on School Maintenance in New Zealand, 21.

43. “Furnishing Our Schools,” 30–1; New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 9–11.

44. New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 9.

45. Ibid., 10.

46. NSWSA: NRS-4352-28 [18/3083.2]-SB.31/193, H. W. Oxford to C. McKinnon, Secretary, Department of Public Works, September 9, 1954.

47. NSWSA: RNCG-1251-1-[A3348 1].

48. New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 13.

49. New South Wales, Department of Education, School Furniture, General section [1].

50. Ibid., General section [3].

51. NSWSA: RNCG-1267 [10/49609.2], H. W. Oxford, “Basis for Planning,” November 11, 1964.

52. New South Wales, Department of Education, Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 16.

53. NSWSA: RNCG-1267 [10/49609.2].

54. NSWSA: RNCG-1267 [10/49609.2], Minutes for February 6 and March 5, 1964.

55. NSWSA: RNCG-1267 [10/49609.2], H. W. Oxford, “Basis for Planning,” November 11, 1964.

56. NSWSA: RNCG-1267 [10/49609.2].

57. NSWSA: NRS-15320-1-44, Oxford, Herbert William; NSWSA: NRS 12395-1-[8/2693] Oxford, Herbert William; Spicer, “Our Chair Authority Receives International Recognition.”

58. Oxford, “Problem of Misfit Furniture,” 3ff.

59. Ibid., 3–7; Oxford, “Anthropometric Data for Educational Chairs,” 141–3; Oxford, “Importance of Human Factors,” 24–8. Results were used by other Australian states, for example Victoria in 1979: Victoria, Department of Education, Planning Services, Role of Anthropometric Data, 7ff.

60. Oxford, “Problem of Misfit Furniture,” 12.

61. Ibid., 13.

62. Oxford, “Anthropometric Data for Educational Chairs,” 153.

63. Oxford, “Importance of Human Factors,” 4, 12.

64. Ibid., 1.

65. Leggett, Planning Flexible Learning Places, 93ff, 100ff.

66. Medd, School Furniture, 69.

67. Ibid., 115–17.

68. New South Wales, Department of Education, Report of the Minister. 1968, 7; 1972, 6.

69. Ibid., 1974, 3; 1963, 19; 1969, 9.

70. Ibid., 1970, 9.

71. Ibid., 1975, 21.

72. New South Wales, Department of Public Works, Annual Report 1977–78, 18; New South Wales, Department of Education, Report of the Minister, 1976, 22; NSWSA: RNCG-1268 [10/49974.3].

73. New South Wales, Department of Public Works, Annual Report 1977–78, 18. A$12,000,000 translates into 2022 figures as A$70,000,000: Reserve Bank of Australia, “Inflation Calculator.”

74. Sebel, “Our Story.”

75. Public Service Notices, September 7, 1988. Located in: NSWSA: NRS-4352-13 [10/50401]-S.5000/1775 Pts. 2–3.

76. NSWSA: NRS-4352-18 [18/3115]-S.5000/1775 Pt. 1; NSWSA: NRS-4352-13 [10/50401]-S.5000/1775 Pts. 2–3.

77. NSWSA: NRS-4352-13 [10/50401]-S.5000/1775 Pt. 2, “SFC Seating/Chairs.”

78. SLNSW, T.A. (Terry Allan) Metherell Ministerial Papers, 1988–1990 MLMSS 7396/73 (106), School Furniture Complex.

79. Scott, Schools Renewal; Carrick, Report of the Committee of Review; Sydney Morning Herald, June 3, 1989, 8; Sun Herald, September 9, 1990, 24.

80. Sun Herald, September 9, 1990, 24; Sydney Morning Herald, December 14, 1993, 4; New South Wales, Department of School Education, Annual Report, 1997, 115, 118. The site and building sale price of A$17,971,991 translates to approximately A$34,000,000 in 2022: Reserve Bank of Australia, “Inflation Calculator.”

81. Medd, School Furniture, 75ff.

Bibliography

- As the Twig is Bent [ motion picture]. NSW, Australia: Department of Education, 1954.

- Australian Council for Educational Research. School Buildings and Equipment. Carlton: Melbourne University Press, 1948.

- Bennett, Henry Eastman. School Posture and Seating: A Manual for Teachers, Physical Directors and School Officials. Boston: Ginn and Company, 1928.

- Blake, L. J. ed. Vision and Realisation: A Centenary History of State Education in Victoria. Vol. 1. Melbourne: Education Department of Victoria, 1973.

- Brunelli, Marta, and Juri Meda. “Gymnastics between School Desks: An Educational Practice between Hygiene Requirements, Healthcare and Logistic Inadequacies in Italian Primary Schools (1870–1970).” History of Education Review, 46, no. 2 (2017): 178–93. doi:10.1108/HER-01-2016-0008

- Burke, Catherine, Peter Cunningham, and Ian Grosvenor. “Putting Education in its Place: Space, Place and Materialities in the History of Education.” History of Education, 39 no. 6, (2010): 677–80. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2010.514526

- Burke, Catherine, and Ian Grosvenor. School. London: Reaktion Books, 2008.

- Burnswoods, Jan, and Jim Fletcher. Sydney and the Bush: A Pictorial History of Education in New South Wales. Sydney: New South Wales Department of Education, 1980.

- Carr, Robert. “Heffron, Robert James (1890–1978).” In Australian Dictionary of Biography. National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/heffron-robert-james-10476/text18583, published first in hardcopy 1996, accessed online November 25, 2022.

- Carrick, J. L. Report of the Committee of Review of New South Wales Schools. Sydney: New South Wales Government, 1989.

- Depaepe, Marc, Frank Simon, and Pieter Verstraete. “Valorising the Cultural Heritage of the School Desk through Historical Research.” In Educational Research: Material Culture and Its Representation, edited by Paul Smeyers and Marc Depaepe, 13–30. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

- Di Mascio, Anthony. “Material Culture and Schooling: Possible New Explorations in the History of Canadian Education.” Material Culture Review, 76 (2012): 82–92.

- Dunt, Lesley. Speaking Worlds: The Australian Educators and John Dewey, 1890–1940. Parkville, Vic.: University of Melbourne, 1993.

- Dussel, Inés. “What Might a Material Turn to Educational Histories Add to the History of Education? Proof-Eating the Pudding.” In Folds of Past, Present and Future: Reconfiguring Contemporary Histories of Education, edited by Frederik Herman, 449–67. München: De Gruyter, 2021.

- “Furnishing Our Schools.” Progress: NSW Public Service Board Journal, 2, no. 4 (August 1963), 30–2.

- Heffron, R. J. To-Morrow is Theirs: The Present and Future of Education in New South Wales. Sydney: Government Printer, 1947.

- Herman, Frederik, Angelo Van Gorp, Frank Simon, and Marc Depaepe. “The School Desk: From Concept to Object.” History of Education, 40, no. 1 (2011), 97–117. doi:10.1080/0046760X.2010.508599

- Hyams, B. K., and B. Bessant. Schools for the People?: An Introduction to the History of State Education in Australia. Hawthorn, Vic.: Longman, 1972.

- International Exhibition. The Victorian State School Exhibit at the Melbourne International Exhibition, 1880. Melbourne, 1880. Accessed May 3, 2023. http://nla.gov.au/nla.obj-67645716

- Kass, Dorothy. Educational Reform and Environmental Concern: A History of School Nature Study in Australia. London: Routledge, 2018.

- Lawn, Martin, and Ian Grosvenor. “Introduction.” In Materialities of Schooling, edited by Martin Lawn and Ian Grosvenor, 7–17. Oxford: Symposium Books, 2005.

- Lawn, Martin, and Ian Grosvenor, eds. Materialities of Schooling: Design, Technology, Objects, Routines. Oxford: Symposium Books, 2005.

- Leggett, Stanton. Planning Flexible Learning Places. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1977.

- McLeod, Julie. “Space, Place and Purpose in Designing Australian Schools.” History of Education Review, 43, no. 2 (2014), 133–7. doi:10.1108/HER-03-2014-0020

- Medd, David. School Furniture. Paris: OECD, 1981.

- Moreno Martínez, Pedro L. “History of School Desk Development in Terms of Hygiene and Pedagogy in Spain (1838–1936).” In Materialities of Schooling, edited by Martin Lawn and Ian Grosvenor, 71–95. Oxford: Symposium Books, 2005.

- New South Wales, Department of Education. Jubilee of the Furniture Workshops, 1913–1963. Sydney: Government Printer, 1963.

- New South Wales, Department of Education. Report of the Minister for Education. 1961–1986.

- New South Wales, Department of Education. School Furniture. Sydney: The Department, 1959.

- New South Wales, Department of Public Instruction. Conference of Inspectors, Teachers, Departmental Officers, and Prominent Educationists, Held Tuesday, April 5, 1904, and following Days [Reports and Proceedings]. Sydney: Government Printer, 1904.

- New South Wales, Department of Public Instruction. Three Years of Education. Sydney: Government Printer, 1914.

- New South Wales, Department of Public Works. Annual Report 1977–78.

- New South Wales, Department of School Education. Annual Report 1996/1997.

- New South Wales, Legislative Assembly, Commission on Primary, Secondary, Technical, and Other Branches of Education. Interim Report of the Commissioners on Certain Parts of Primary Education Containing the Summarised Reports, Recommendations, Conclusions, and Extended Report of the Commissioners. Sydney: Government Printer, 1904.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS 3829, School Files, 1876–1979. [5/17670] Stanmore Public School, 1916–1919.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS-4352-13 [10/50401]-S.5000/1775 Pts. 2-3, Schools Generally, Schools Building Research & Development Group, Furniture Committee Minutes & Reports commencing, August 1987.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS-4352-18 [18/3115]-S.5000/1775 Pt. 1, School Building Research & Development Group, Furniture Committee Minutes and Reports Commencing January 1985.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS-4352-28 [18/3083.2]-SB.31/193, Schools Generally, Supply of Furniture and Equipment.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS15051, Department of Education. Photographic Collection.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS 12395-1-[8/2693], Public Service Board Employees’ History Cards.

- New South Wales State Archives: NRS-15320-1-44, Teacher Career Cards.

- New South Wales State Archives: RNCG-1251-1-[A3348 1], Plans of School Furniture.

- New South Wales State Archives: RNCG-1267 [10/49609.2], School Furniture Complex, Minutes of the Furniture Centre Planning Committee, 1964–1965.

- New South Wales State Archives: RNCG-1268 [10/49974.3], School Furniture Complex Photographs, c.1960–80.

- Oxford, H. W. “Anthropometric Data for Educational Chairs.” Ergonomics, 12, no. 2 (1969), 140–61.

- Oxford, H. W. Freedom from Want. Armidale, NSW: Armidale Express Print, 1942.

- Oxford, H. W. “The Importance of Human Factors in the Design and Layout of Educational Furniture.” Paper presented at the Educare International Exhibition Conference, Melbourne, Australia, 1971.

- Oxford, H. W. “The Problem of Misfit Furniture.” Paper presented at the Ergonomics Society of Australia and New Zealand, 3rd Annual Conference, Sydney, August 1966. Sydney: Department of Education, 1966.

- Oxford, H. W. Report on School Buildings, School Equipment and School Maintenance Overseas. Sydney, 1952.

- Oxford, H. W. Report on School Maintenance in New Zealand. Sydney, 1955.

- Reserve Bank of Australia. “Inflation Calculator.” Accessed May 9, 2023. https://www.rba.gov.au/calculator/annualDecimal.html

- Scott, Brian W. Schools Renewal: A Strategy to Revitalise Schools within the New South Wales State Education System. Milson’s Point, NSW: Management Review, 1989.

- Sebel. “Our Story.” Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.sebelfurniture.com/en-au/about-us/our-story

- Simpson, M. M. Report on the Montessori Methods of Education. Sydney: Government Printer, 1914.

- Smeyers, Paul, and Marc Depaepe, eds. Educational Research: Material Culture and its Representation. Heidelberg: Springer, 2014.

- Spicer, Alf. “Our Chair Authority Receives International Recognition,” Education, March 20, 1968, 38.

- Stanford University. Department of Anthropology. “Materiality.” Accessed May 1, 2023. https://anthropology.stanford.edu/research-projects/materiality

- State Library of New South Wales. T.A. (Terry Allan) Metherell Ministerial Papers, 1988–1990, MLMSS 7396/73 (106). School Furniture Complex, Being Report Compiled by John Hatton Together with Related Correspondence.

- Turney, Cliff. “Continuity and Change in the Public Primary Schools, 1914–32.” In Australian Education in the Twentieth Century, edited by J. Cleverley and J. Lawry, 32–76. Camberwell, Vic.: Longman, 1972.

- Victoria, Department of Education, Planning Services. The Role of Anthropometric Data in the Design of School Furniture. Victoria: Planning Services, Department of Education, 1979.