Abstract

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Biology Teaching Assistants (TAs) were tasked with transitioning and adapting their instruction to an online environment by quickly implementing Emergency Remote Teaching (ERT) practices. Effective online and in-person teaching requires student-centered approaches to support undergraduate student learning. Using interviews and the Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI), a case study was conducted to explore the impact on TAs approaches to teaching during the transition to an online emergency remote environment, and to identify areas where TAs need further support through Teaching Professional Development (TPD). The findings revealed themes regarding challenges in the ERT context, such as decreased active learning opportunities, decreased office hours attendance, decreased student engagement, and more time spent on teaching tasks. Our work provides educational researchers and practitioners with key aspects that can improve TPD for online teaching and learning.

Introduction

In March 2020, universities worldwide moved courses online in response to the COVID-19 pandemic. Instructors, teaching assistants (TAs), and staff scrambled to support undergraduate student learning in emergency remote teaching (ERT). This global event generated numerous educational questions when students moved online (Zimmerman, Citation2020).

Prior to the pandemic and ERT, a rich body of literature compared online and face-to-face learning formats and suggested improvements for online teaching. These included offering students tutorials, facilitating interactions among learners and between learners and teachers, and fostering metacognition (Biel & Brame, Citation2016). In their meta-analysis of online learning, Kebritchi et al. (Citation2017) suggest that best practices for online and face-to-face are similar and should be student-centered and include active learning practices like peer discussions. Teaching online may require a different approach than face-to-face, often requiring more instructor management and facilitation (Baran et al., Citation2011; Kebritchi et al., Citation2017). Further, it is challenging for instructors to see cues from students regarding their understanding in the online environment, and communication can be strained (Kebritchi et al., Citation2017). As summarized in their meta-analysis, Trespalacios et al. (Citation2021) identified numerous instructional strategies for supporting online classroom community such as live synchronous sessions, supporting students’ sense of identity, and strong communication.

Ideally, there would be consistent training on pedagogical approaches specific to the online context. This has been a persistent gap, as pre-pandemic literature called for more teacher training in online learning pedagogy (Kebritchi et al., Citation2017). An important note, however, is that ERT is different from online teaching because courses that made this abrupt change to online were not originally designed for an online format (Hodges et al., Citation2020). Early in the pandemic, suggestions for successful transition to ERT were reported. These included limiting lecture videos, inviting student engagement, and identifying students who might need extra support (Boudreau, Citation2020; Farah, Citation2020; Gewin, Citation2020). We speculate that experienced instructors and TAs would implement these practices in ERT, but without formalized professional development in online teaching, not all instructors may have implemented these recommendations.

At research intensive universities such as our study site, TAs teach the majority of laboratory courses (Sundberg et al., Citation2005). In these laboratory courses, the move to an online environment can be difficult, especially for novice TAs. Introductory Biology TAs who were teaching laboratory and recitation components during Spring 2020 were asked to rapidly adjust their teaching to a completely online format. These TAs varied in their prior teaching experience, and midway through that semester they needed to adjust quickly, learn necessary technology, and help their students adapt.

In the program for this study, TAs receive thorough teaching professional development (TPD) that trains TAs in student-centered, active learning teaching practices (Ridgway et al., Citation2017). The TPD at the R1 institution has four main components: preterm training, weekly TA meetings, classroom observations, and an independent TA professional development course. The TPD program requires TAs, with the support of a course instructor, to develop a professional development plan that aligns to their own teaching and career goals. Also, while the TA is employed in the Biology department, they are required to participate in TPD, making their PD an ongoing process. The TPD model goes beyond addressing the usual student-centered teaching approaches by including components that support the professional teaching identity in TAs (see Ridgway et al., Citation2017, for further information of the TPD model at the R1 institution). Despite this training, with the abrupt move online during ERT we may see shifts in TA teaching practices and the online environment may promote one teaching practice over another. The differences in the teaching environment could, for example, modify the type of interactions between instructor-students and student-student, or the radical change to an online setting might limit instructors from implementing inquiry-based approaches in their teaching. Priority shifts might emerge with a focus on delivering content to move the semester along, rather than considering the manner in which the content can be best delivered. Understanding these shifts can help us address any deficits in the use of active learning and student-centered pedagogy in the online environment.

Studies have also shown that parts of online teaching take more time than face-to face, such as grading and evaluating student work (Van de Vord & Pogue, Citation2012). Identifying areas where TAs are stressed for time can help us develop better support mechanisms for them so they can focus on student learning. Further, some benefits may be revealed through exploring ERT teaching approaches. Scagnoli et al. (Citation2009) found that faculty were more likely to transfer online teaching strategies to their face-to-face teaching practices. Therefore, some TAs may use strategies developed in the online environment in their own face-to-face practices.

Understanding the challenges, supports, and changes in approaches to teaching will help us develop specific training and support for TAs in the future. This study applied the framework developed by Reeves et al. (Citation2016) to explore the impact of the transition to ERT on TAs approaches to teaching. Through TA feedback we addressed the following research questions:

What effects did ERT have on TAs approaches to teaching?

What types of support did TAs receive for ERT?

What resources did TAs provide to students?

How did TAs spend time on teaching tasks?

Methods

This study took place in a large midwestern R1 university’s Biology department. TAs in this study are either a Biology lab or recitation instructor, which in our context are undergraduate students, graduate students, or contract lecturers. Generally, lab instructors conduct ∼45 minutes of recitation, followed by two hours of lab instruction. Labs are either inquiry-based or course based undergraduate research experiences (CUREs). Instructors of recitations without lab lead a 2-hour recitation session with student-centered planned activities. During the switch to ERT, lab/recitation met synchronously online. TAs first led a recitation, and then introduced the lab exercise. Students were then asked to work online with their lab groups and submit one report. In the ERT, students were given simulated data to analyze where applicable. In pre-ERT, lab reports were due at the end of class. In ERT, lab reports were due 48 hours after the class period. Many students left the zoom room after the lab was introduced to work offline; therefore, the overall online lab/recitation session was shorter than in-person classes.

Data Collection

Our approach was to capture narratives of individuals impacted by ERT in the laboratory or recitation environment. Biology TAs were recruited via email to participate in an online survey the last week of the Spring 2020 semester. Eight study participants completed the Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI, Trigwell et al., Citation2005) two times in the same survey. The first time prompted TAs to respond to the ATI items in a way that matched their reaction to the items before moving online. The second time prompted them to answer the items reflective after the move online, similar to a retrospective post-test. The ATI contains 22-items with 2 sub-scales: Information transfer or teacher-focused, and Conceptual change or student-focused (). Responses range on a frequency scale in which 1 = rarely true, and 5 = always true. TAs who participated in the survey were asked if they could be contacted for an interview. Five TAs agreed to participate in ∼1-hour semi-structured interviews after completing the ATI. The five TAs represented five different sections of three introductory Biology courses (both Biology majors and nonmajors) and were either graduate students or contract TAs. This study was determined exempt by the university’s Office of Responsible Research Practices (2020E0644, 2020E673).

Table 1. Example items from the Approaches to Teaching Inventory (ATI, Trigwell et al., Citation2005).

Analysis

The ATI was used to quantify changes in teaching practices pre- and post-ERT. Student-centered and teacher-centered scores were summarized and scaled per number of items for each participant. Five participants consented to the interviews and from those five, four consented to the use of their ATI responses. Therefore, we report 4 ATI responses and summarize 5 interviews. We applied a grounded theory approach (Glaser & Strauss, Citation1967) to determine emerging themes from the TA interviews related to the four research questions. Specifically, we wanted to gain a better understanding of the perceived changes in TA approaches to teaching, time spent on teaching activities, resources provided to students, and the support and training TAs received. Interview transcripts were first analyzed by one author who developed the initial codes and categories. Two other authors used this codebook for each transcript, and all three authors discussed the codes, revising and regrouping to consensus. Selected quotes represent emergent themes from all interviewees. Due to the small sample size, we do not attribute specific quotes to any one participant to protect identities.

Results

We developed two models representing major themes emerging from the transcript analysis. These models center on the TAs in relationship to the tasks, challenges, and support during the ERT. These findings detail the impact of ERT on TAs teaching practices and how they navigated these unforeseen circumstances.

Shift to Instructor-Centered Practices in Online Environment

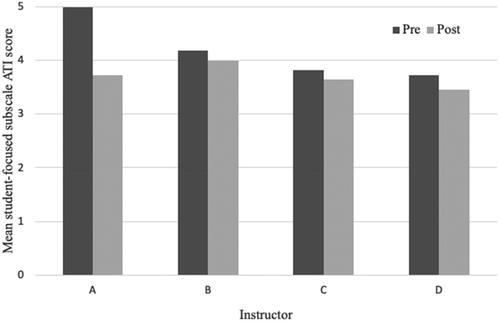

Four of the five TAs interviewed consented to use of their ATI survey responses. The ATI data revealed an overall decreasing trend of student-centered approaches to teaching after the switch to ERT (); however, three of the four TAs demonstrated a minor shift. Although the TAs are aware of the importance of active learning practices to support student learning, they viewed the transition to ERT as a limiting factor for their incorporation of inquiry-based pedagogical practices. TAs value the in-person interaction with their students that they have in their classroom setting and expressed how many students felt uncomfortable participating in synchronous online discussions. TAs also noticed the following changes after the move online: reduced student learning autonomy, reduced opportunities to engage students in meaningful discussions, and increased need to prevent students’ mistakes.

Figure 1. Mean student-focused subscale ATI scores (11 items) for 4 of 5 instructors (labeled A-D) interviewed in response to the pre and post switch to ERT. Higher scores indicate more use of student-centered practices.

One TA compared the online experience to the in-person recitation noticing how opportunities for hands-on experiences decreased: “…for recitation, generally, less hands-on activities than I would have done in person. It was just too hard to structure and to change things completely on the fly. So, there was a little bit more PowerPoint content than I would have done in person.” TAs reported that an online environment prevents inquiry-based learning leading to a teacher-centered approach. As one interviewee states, “since we’re not in the lab room there is not as much opportunity to let students mess up or fail and then have me there to correct it… so there’s less inquiry-based type learning where they’re figuring things out on their own [at home].”

Additionally, as a student-centered approach, TAs encouraged their students to provide explanations to questions. However, this practice became a challenge in an online environment: “[During in-person teaching, I’m] walking around having them explain the questions…and we have these discussions on how to go through the problem, step by step. And of course, that’s student centered because I don’t tell them anything. I just have them tell me… After the online transition, this happened only with a select group of students.”

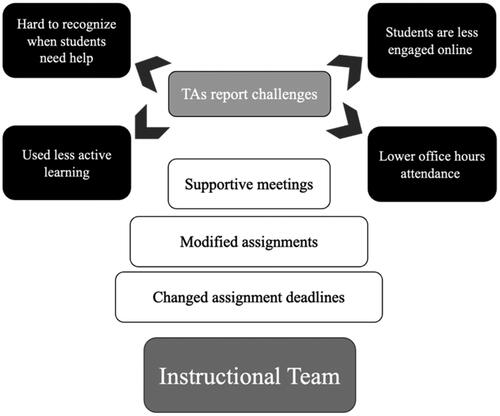

Support from Instructional Team

The unexpected transition to ERT led to four main challenges as expressed by the TAs: difficulty recognizing when students need help, decrease of active learning opportunities, decrease of office hours attendance, and decrease of student engagement (). The challenge to identify when students needed help is exemplified by this interviewee quote, “…just because I can’t walk around the room and get a sense of how everybody’s doing and hop in and hop out whenever I see someone needing help. So, it’s hard to reach all the students equally in zoom compared to in-person.” Secondly, the decrease of office hours attendance was expressed by an interviewee, “Had relatively like almost no office hours visit, very few office hours visits. Whereas usually later in the semester I would see more office hours visits since they were preparing for the third or fourth exams for a class.” Thirdly, in an online environment, TAs found it difficult to engage students, as noted by this interviewee, “… students were saying that they would sometimes just kind of space out because they’re just looking at a screen.” TAs were aware of the mental fatigue students might be experiencing in the online environment.

In our model, the instructional team served as the base of the support system during the ERT to overcome the above challenges. The instructional team supported TAs through meetings, modified assignments, and changed assignment deadlines. This is exemplified by one interviewee, “Big shout out to [Course Coordinator (CC)] and [CC] for getting the [Learning Management System] all set up; they did a great job on that… the two of them definitely alleviated any of that initial kind of stress and fear that I had.” Another form of support received was an increase in communication. A TA mentioned, “…definitely there was a lot of communication, mostly through email, some zoom chat, some phone calls about how to get things moving.”

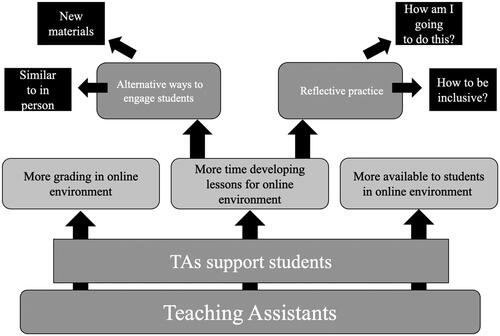

TAs Offering Support to Their Students

TAs supported their students by being available, giving feedback, and developing lessons (). TAs developed alternative ways to engage students, such as using pop culture references. TAs engaged in reflective practices to address all students in an inclusive manner, as the following TA mentioned, “…the sudden transition to online instruction made me really creative. And think about engaging with students, regardless of their diverse schedules/backgrounds.”

Figure 3. The model demonstrates teaching responsibilities and strategies implemented by TAs to support their students during ERT.

TAs expressed their intention of making the online learning environment similar to the in-person setting and developed/incorporated new materials to support student learning such as the use of videos and Google docs. An example of this is the following quote, “It was definitely harder to go through the recitation, because I do a lot of whiteboard stuff … in the lab. And I have a small whiteboard, and I would hold it up over here [to the video camera] and try to draw and adjust, so they could see…”

TAs’ Time on Teaching Responsibilities

The TAs highlighted three main tasks on which their time increased in an online environment: availability to students, grading responsibilities, and developing lessons. Our TAs described having additional work (grading, communications), without a significant reduction in class time (). When asked about the amount of grading done in an online environment in contrast to in-person, one TA responded, “Definitely more than because there were more assignments that TAs had to grade.” Another TA stated, “But the grading increased so much. And so that was just with the structure of the course, we were trying to be flexible and allow students to do things individually and asynchronously. When we would normally have them do it in groups and in person.”

Developing lessons in an online environment was more time consuming for TAs as expressed by one interviewee, “I feel like online courses take more time and certainly in this Bio course for spring semester, post spring break, I was definitely spending more time on developing recitation, providing extra resources.” Even with the decrease of student office hour attendance, TAs still made the effort to be more available to their students in the online environment. A TA mentioned, “Just feeling more available via email, to answer questions because more emails were coming in. So, it took a significant chunk of time to do that and more time than I probably would have taken had everything continued in person.”

Conclusions and Implications

Although a small sample limits generalization, these TA’s voices reveal common themes. Our TAs identified numerous challenges in the ERT context, such as decreased active learning opportunities, decreased office hours attendance, decreased student engagement, and more time spent on teaching tasks. Similarly, Henne et al. (Citation2023) found that lecturers mentioned issues with communication, an increased workload, and student engagement. Therefore, our findings are similar to others in the literature, but further research should explore this in other university contexts, as well as how prior online experiences might influence teaching practices.

Regardless of the thorough TPD the TAs receive at our institution, participants reported in both the survey and interview data a decrease in use of student-centered pedagogies in their online classrooms. Durham et al. (Citation2022) also found that scientific teaching practices, especially those related to active learning decreased in the online environment, but they reported that experience with these practices in the face-to-face environment made it more likely for instructors to use evidence-based practices in ERT. Although our TAs had significant training experiences in student-centered pedagogy, they expressed struggles to implement strategies in a new context. However, some studies showed innovative ways to adapt active learning and engage students during ERT (Durham et al., Citation2022; Morrison et al., Citation2021, Rossi et al., Citation2021). Therefore, offering TPD is crucial for successful incorporation of active learning during ERT.

Moreover, our TAs found it challenging to engage students, especially without visual cues from students. Literature from the student perspective supports these findings, with students reporting that distractions were prevalent in the ERT context, and communication with instructors and peers became difficult (Bahrami et al., Citation2023). Our TAs reported spending more time trying to engage their students, give students valuable feedback, and be available to students. This added work our TAs described is consistent with Van de Vord and Pogue (Citation2012). In contrast, Smith et al. (Citation2023) observed TAs reduced some of their duties due to the nature of online teaching, involving email and video calls.

This study highlights different TPD elements that can be incorporated in a post-pandemic world. Walsh et al. (Citation2022) make a firm call for the STEM community to proactively include TPD for online education. As instructors share their successful pedagogical strategies (Bahrami et al., Citation2023; Durham et al., Citation2022; Morrison et al., Citation2021), specific training can be developed. Based on this study’s findings, workshops on student-centered techniques in the online environment are needed. Additionally, we need to develop support mechanisms in areas where TAs are stressed for time (e.g., grading) so they can focus on supporting student learning, including the implementation of equitable practices.

Finally, TAs did their best in a situation that was extremely stressful for all. As reported in one study, pandemic related changes in teaching duties induced stress, and thus influenced TAs’ confidence in teaching (Smith et al., Citation2023). As we develop new TPD training for all instructors, it is important to keep these stressors in mind. In a training course for chemistry TAs, Dragisich (Citation2020) included components on wellness and community as a way of developing survival skills for instructors. Self-care and mental wellness should be a cornerstone for any new TPD developed, regardless of the mode of instruction.

Understanding teaching approaches utilized during ERT, the relative effectiveness of those approaches, and incorporating suggestions from ERT instructor reflections, may help prepare units and educators for any future events that require moving courses online. Combining earlier online best practices with lessons from ERT may best inform TA professional development around online instruction and in preparation for any future need to adopt ERT. We are only beginning to understand the impact this event may have had on college Biology instruction and more specifically on college Biology TAs and their approaches to teaching.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the TAs who gave their time to speak with us. No financial support was received for this study.

References

- Bahrami, P., Blanco, D., Thetford, H., Ye, L., & Chan, J. Y. K. (2023). Capturing student and instructor experiences, perceptions, and reflections on remote learning and teaching in introductory chemistry courses during COVID-19. Journal of College Science Teaching, 52(6), 6–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/0047231X.2023.12315861

- Baran, E., Correia, A.-P., & Thompson, A. (2011). Transforming online teaching practice: critical analysis of the literature on the roles and competencies of online teachers. Distance Education, 32(3), 421–439. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2011.610293

- Biel, R., & Brame, C. J. (2016). Traditional versus online biology courses: Connecting course design and student learning in an online setting. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 17(3), 417–422. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v17i3.1157

- Boudreau, E. (2020). The Shift to Online Teaching [Online]. Online: Harvard Graduate School of Education. Retrieved from https://www.gse.harvard.edu/news/uk/20/03/shift-online- teaching

- Dragisich, V. (2020). Wellness and community modules in a graduate teaching assistant training course in the time of pandemic. Journal of Chemical Education, 97(9), 3341–3345. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.jchemed.0c00652

- Durham, M., Colclasure, B., & Brooks, T. D. (2022). Experience with Scientific Teaching in face-to-face settings promoted usage of evidence-based practices during emergency remote teaching. CBE Life Sciences Education, 21(4), ar78. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.22-03-0049

- Farah, K. (2020). 4 Tips for Teachers Shifting to Teaching Online [Online]. Online: Edutopia. Retrieved from https://www.edutopia.org/article/4-tips-supporting-learning-home

- Gewin, V. (2020). Into the digital classroom: Five tips for moving teaching online as COVID-19 takes hold. Nature, 580(7802), 295–296. https://doi.org/10.1038/d41586-020-00896-7

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

- Henne, A., Möhrke, P., Huwer, J., & Thoms, L.-J. (2023). Learning Science at University in times of COVID-19 crises from the perspective of lecturers-an interview study. Education Sciences, 13(3), 319–337. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci13030319

- Hodges, C., Moore, S., Lockee, B., Trust, T., Bond, A. (2020, March 27). The difference between emergency remote teaching and online learning. EDUCAUSE Review. Retrieved from https://er.educause.edu/articles/2020/3/the-difference- between-emergency-remote-teaching-and-online-learning

- Kebritchi, M., Lipschuetz, A., & Santiague, L. (2017). Issues and challenges for teaching successful online courses in higher education: A literature review. Journal of Education Technology Systems, 46(1), 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0047239516661713

- Morrison, E. S., Naro-Maciel, E., & Bonney, K. M. (2021). Innovation in a time of crisis: Adapting active learning approaches for remote biology courses. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 22(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.v22i1.2341

- Reeves, T. D., Marbach-Ad, G., Miller, K. R., Ridgway, J. S., Gardner, G. E., Schussler, E. E., & Wischusen, E. W. (2016). A conceptual framework for graduate teaching assistant professional development evaluation and research. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 15(2), pii:es2. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.15-10-0225

- Ridgway, J. S., Ligocki, I. Y., Horn, J. D., Szeyller, E., & Breitenberger, C. A. (2017). Teaching assistant and faculty perceptions of ongoing, personalized TA professional development: Initial lessons and plans for the future. Journal of College Science Teaching, 046(05), 73–83. https://doi.org/10.2505/4/jcst17_046_05_73

- Rossi, I. V., de Lima, J. D., Sabatke, B., Nunes, M. A. F., Ramirez, G. E., & Ramirez, M. I. (2021). Active learning tools improve the learning outcomes, scientific attitude, and critical thinking in higher education: Experiences in an online course during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biochemistry and Molecular Biology Education: a Bimonthly Publication of the International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 49(6), 888–903. https://doi.org/10.1002/bmb.21574

- Scagnoli, N. I., Buki, L. P., & Johnson, S. D. (2009). The influence of online teaching on face-to face practices. Journal of Asynchronous Learning Network, 13(2), 117–128.

- Smith, C., Menon, D., Wierzbicki, A., & Dauer, J. (2023). Teaching assistant responses to COVID-19 investigating relationships between stress, self-efficacy, and approaches to teaching. Journal of College Science Teaching, 52(3), 3–5. https://doi.org/10.1080/0047231X.2023.12290695

- Sundberg, M. D., Armstrong, J. E., & Wischusen, E. W. (2005). A reappraisal of the status of introductory biology laboratory education in U.S. colleges and universities. The American Biology Teacher, 67(9), 525–529. https://doi.org/10.2307/4451904

- Trespalacios, J., Snelson, C., Lowenthal, P. R., Uribe-Flórez, L., & Perkins, R. (2021). Community and connectedness in online higher education: A scoping review of the literature. Distance Education, 42(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2020.1869524

- Trigwell, K., Prosser, M., & Ginns, P. (2005). Phenomographic pedagogy and a revised approaches to teaching inventory. Higher Education Research & Development, 24(4), 349–360. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360500284730

- Van de Vord, R., & Pogue, K. (2012). Teaching time investment: Does online really take more time than face-to-face? The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(3), 132–146. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i3.1190

- Walsh, L. L., Bills, R. J., Lo, S. M., Walter, E. M., Weintraub, B. E., & Withers, M. D. (2022). We can’t fail again: Arguments for professional development in the wake of COVID-19. Journal of Microbiology & Biology Education, 23:e00323-21. https://doi.org/10.1128/jmbe.00323-21

- Zimmerman, J. (2020). Coronavirus and the great online-learning experiment. Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved from https://www.chronicle.com/article/coronavirus-and-the-great-online- learning-experiment