ABSTRACT

This article surveys ideological developments in Indonesia over the past two decades, tracing a shift in the ideological centre of gravity from the embrace of democratic norms in the immediate post Suharto period towards a conservative and inward-looking religious nationalism. Several reasons are identified for this shift, including the failure of reformers to adequately deal with the legacy of Suharto’s Pancasila indoctrination project and the success of conservative New Order elites in regaining control of the democratic process after 2001. Attention is given to the concessions made to Islamist interests under President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, which gave conservative Islam an unprecedented level of power and legitimacy. Of special importance here was the Constitutional Court’s validation of the blasphemy law, helping transform Indonesia into an overtly religious state and pave the way for greater state involvement in enforcing moral norms based both on Islamic values and a conservative reading of indigenous culture. The article also highlights the success of Prabowo Subianto’s populist authoritarian movement in linking with sectarian groups, prompting President Joko Widodo to adopt an increasingly authoritarian and xenophobic agenda, leaving little space for the public defence of secular law, pluralism, democracy and human rights.

One of the striking images of the late 2016 rallies against Jakarta governor Basuki “Ahok” Purnama was an Indonesian flag the length of a football pitch being carried over the heads of a massive demonstration by hard-line Muslim leaders and their followers in central Jakarta. It was remarkable because the “Red and White” of the flag has long been the symbol of the secular or anti-Islamist nationalists in Indonesia. Its embrace by Islamists illustrates an important development in the ideological landscape in Indonesia over the past two decades, namely the convergence of religious and nationalist conservatisms to produce a new brand of religious nationalism. This stream of political thinking is at once nativist, religious and nationalist. It views the Indonesian nation as having been born in opposition to secular-liberalism and regards the state as having a unique historical obligation to protect and enforce religious values. While far from hegemonic, religious nationalism has come increasingly to occupy the centre ground in Indonesian politics.

To examine how this happened, this article focuses on ideology in the years since the fall of President Suharto. If we equate ideology with legitimating propaganda promoted by state agencies – as studies of ideology in Indonesia have tended to do – we can certainly say that it has become less pronounced than it was during the Suharto era of 1966–1998 (see, for instance, Morfit Citation1981; Hadiz Citation2004; McGregor Citation2007; Bourchier Citation2015). One of the first acts of the Habibie government following the fall of Suharto in 1998 was to dismantle the indoctrination programme that had been such a pervasive feature of Suharto’s “New Order.” While post-Suharto cabinets have all had their slogans and programmes, they have not given priority to enforcing ideological conformity. The study of ideology in non-authoritarian systems requires a wider lens, one that analyses competition over “the control of political language and policy” (Freeden Citation2010, 480) and “battles over the articulation of rival decontestations of central political concepts” (Maynard Citation2013, 302).Footnote1 If we define ideology in this broader sense as a battleground of ideas about democracy, culture, law and religion then it is clear that ideology remains a crucial part of political contestation.

The most frequent and hotly contested disputes, especially in the past decade, have been over the question of the proper relationship between the state and Islam, namely the extent to which the state should be responsible for upholding Islamic values.Footnote2 But it is important to recognise other ideological fault lines that intersect with this debate. One is the argument between those seeking to preserve the democratic gains of reformasi and those who favour a return to New Order style rule, or, put differently, democracy versus authoritarianism. Another is cosmopolitanism versus nativism, the argument between those who appeal to putative universal principles such as human rights versus those who argue that law and politics should rather be informed by “traditional cultural values” such as harmony, mutual assistance (gotong royong) and communal deliberation (musyawarah). Debate over these issues was especially visible during the 2014 presidential election between supporters of Joko Widodo (known as Jokowi) and Suharto’s former son-in-law Prabowo Subianto.

This article uses these concepts to sketch the major ideological developments in the post-Suharto era. Because the production and consumption of ideology was such a feature of the Suharto period this article begins with a brief examination of how the New Order regime deployed the state ideology of Pancasila or the “Five Principles.”Footnote3 Pancasila should be understood as the frame within which debates over ideology take place in Indonesia; all ideological battles are in a sense battles over the interpretation of Pancasila (see Gellert Citation2015, 374). Using a mainly historical structure, the article then examines the reaction to aspects of New Order ideology before going on to map ideological continuities and innovations against the changing political circumstances of the democratic period. While ideology is never an easy thing to pin down, it will be argued that political battles of the past two decades have shifted the ideological centre of gravity from the democratic cosmopolitanism of the Habibie and Abdurrahman Wahid period – defined here as an orientation to liberal democratic norms and universal principles of human rights – towards a more intolerant, conservative brand of religious nationalism. While religious nationalism took shape during the presidency of Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, it has gathered momentum in recent years thanks to the alliance between Prabowo’s populist authoritarian movement and the resurgent sectarianism led by Islamist groups.

Suharto’s “Pancasila Democracy”

While Suharto claimed to disavow politics in favour of developmentalism, he devoted enormous resources to promoting and enforcing ideological conformity. His regime represented itself from the start as the champion of Pancasila, the state ideology articulated by Sukarno during the constitutional debates of June 1945. This was no easy task because it involved prising Pancasila from its author and convincing the public that Sukarno had betrayed Pancasila. The ideologues of the early New Order period did this by archaising Pancasila, by redefining it as the original cultural essence of the Indonesian people, innocent of the Western ideologies, including communism, that Sukarno had allowed to “pollute” Indonesian politics. Suharto (Citation2003, 104–109), like Sukarno, claimed that Pancasila had been “excavated” from indigenous tradition but while Sukarno’s image of traditional culture was dynamic and egalitarian, Suharto’s was hierarchical, harmonious and orderly.

As argued elsewhere, the New Order regime’s depiction of traditional culture as static and harmonious had been favoured since the 1930s by a conservative aristocratic stream of nationalism with an interest in maintaining social stability (Bourchier Citation2015). It took root in Indonesia thanks to the influence of lawyers educated at the Leiden School of Law who embraced not only a romanticised view of Indonesian village life but also the assumption, which goes back to the ideas of the jurist von Savigny, that a nation’s legal order is legitimate only to the extent that it reflects that nation’s indigenous spirit, its Volksgeist.

By successfully linking Pancasila with this conservative vision of Indonesia’s culture and at the same time elevating Pancasila to semi-sacred status in both the ideological and legal realms, the New Order forged a powerful weapon with which to authenticate its rule and silence its critics. Representing itself as the saviour and guardian of Pancasila enabled the regime, with the assistance of its substantial security and intelligence apparatus, to accuse its leftist and liberal critics of being anti-Pancasila and thereby un-Indonesian. Demands for human rights and democracy could be dismissed on the grounds that while these notions may be appropriate for individualistic cultures they had no place in Indonesia’s “Pancasila Democracy” because Indonesian society was, in its essence, communalistic, harmonious and consensus seeking.

Suharto’s regime invested heavily in Pancasila education, especially after 1978, eventually extending it to all sectors of society through the so-called P4 programme (Guide to the Realisation and Implementation of Pancasila). In the early 1980s Suharto introduced a law requiring all social and political organisations to adopt Pancasila as their sole ideology. The implementation of this law, aimed largely at Islamic organisations whose loyalty the president doubted, helped generate significant animus on the part of politically interested Muslims towards Suharto and the Pancasila itself (see Bourchier and Hadiz Citation2003, 139–157). The fact that Suharto regarded the displacement of “foreign” ideologies by Pancasila to be one of the crowning achievements of his presidency (Suharto Citation1988, 382–383, 408–409; Elson Citation2001, 239–240) tells us a great deal about his mind-set and the central place that ideology played in the politics of New Order Indonesia.

To shore up the regime’s defences against increasing criticism by advocates of human rights, New Order ideologues in the 1980s declared Indonesia to be an “integralist state” (Simanjuntak Citation1994, 63). Already well-known in conservative Catholic social thought, the term “integralism” was introduced to Indonesia by the customary law expert Supomo. In the 1945 constitutional debates, Supomo had outlined his vision of Indonesia as a traditional village writ large, in which all members contributed to the wellbeing of the whole and in which there was held to be no inherent conflict between rulers and ruled and therefore no need for political rights.Footnote4 New Order officials, especially those associated with the powerful State Secretariat, made the case that integralism was the underlying principle of the 1945 Constitution and that consequently there could be no legitimate place in Indonesia for the separation of powers, political opposition or other divisive practices such as voting in parliament.

The beginning of the end for New Order ideology came during the brief democratic thaw of 1989–1990 known as keterbukaan or openness/glasnost (Bourchier and Hadiz Citation2003, 185–211). State ideologues came under fire from civil society activists who argued that Supomo had not only been defeated in the 1945 debates but that the claim that integralism was indigenous was belied by Supomo’s own admission that it was derived from European legal philosophy and was in tune with German and Japanese totalitarianism (Simanjuntak Citation1994). Keterbukaan also saw military and civilian critics take on other key aspects of the authoritarian Pancasila Democracy system which had changed little since the 1970s. They called for sweeping democratic reforms while intellectuals criticised sacred cows of New Order ideology including the emphasis placed on decision making via communal deliberation and consensus (musyawarah and mufakat) as not only unworkable in a modern industrialising nation but as the source of injustice on the grounds that they were frequently used to suppress dissent and to benefit the strong over the weak (Jakarta Post, July 25, 1989). Meanwhile frustration with Pancasila education came to the fore, with even veteran ideologues admitting that people were fed up with the courses. The chasm between the ideals promoted by Pancasila courses and the corruption and nepotism of the New Order administration had become too obvious to ignore.

Faced with eroding support from within the military and his one-time allies in the professional and business classes, Suharto attempted to reach out to Muslim groups marginalised by his longstanding policy of keeping religion separate from politics. The key initiative here was Suharto’s creation of the Association of Indonesian Muslim Intellectuals in 1990 which, to the consternation of many of his generals, served as a conduit for pious Muslims into the upper reaches of the bureaucracy. The influx of Muslims into senior government and military positions improved relations between the president and political Islam, but was not enough to prevent the collapse of the regime’s legitimacy in the wake of the Asian Financial Crisis which devastated the Indonesian economy in 1997 and 1998.

Reformasi: Brief Ascendency of Democratic Cosmopolitanism

When the reformasi movement forced Suharto to resign in May 1998 it looked like every aspect of the New Order system was open to question: its centralism, its authoritarianism, its military underpinnings, its exceptionalism. In a giddy few weeks the old platitudes were cast off, as new parties formed, newspapers sprouted and new unions were established. After decades of propaganda about the lack of fit between Indonesian culture and “Western-style” democracy, some version of multiparty democracy now appeared to be the obvious choice. Under the tenuous leadership of President Habibie, Indonesia underwent a period of rapid democratisation and by the end of 1998 had lifted restrictions on the press, curtailed the privileges of the former ruling party Golkar, limited the tenure of the president and put in place preparations for Indonesia’s first democratic elections since 1955. Habibie’s energetic administration also reversed decades of centralisation with its 1999 laws devolving powers to the sub-provincial level. Further reforms over the next two years saw the military, discredited by their years of abuses under the New Order, withdraw from formal politics.

The sharp swing towards democratic cosmopolitan values saw the open repudiation of the New Order’s Pancasila discourse. As As’ad Said Ali (2009, 49) put it, after having “distorted it, sacralised it, monopolised it and used violence to defend it” Suharto’s “hollowed out Pancasila … fell flat on its face along with the New Order.” Habibie’s government quickly dispensed with Pancasila indoctrination courses and initiated planning for a new Citizenship Education subject for the national curriculum emphasising democratic rights, pluralism and political participation. Legislation requiring all political parties and social organisations to base themselves on Pancasila was abolished and family–state metaphors all but disappeared from official discourse as legislators from the political mainstream espoused liberal democratic ideals of governance. In his state of the nation address in August 1998, for instance, Habibie (2003, 298–299) promised thoroughgoing reforms aimed at “reinforcing democracy based on popular participation,” the right to organisation and free speech, independence of the judiciary and human rights, stating,

we have left behind us once and for all the notion that human rights are a product of Western culture. We state clearly that human rights imply a commitment by all of us to respect the honour and dignity of humankind irrespective of race, ethnicity, skin colour, sex or social status.

By 2002, the Constitution, which had for decades been regarded as immutable, had undergone far-reaching amendments resulting in a stronger parliament, a popularly elected president, the separation of powers, an independent Constitutional Court and the adoption of a comprehensive set of rights guarantees based on the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

The ground-breaking democratic reforms instituted under presidents Habibie and Wahid were to see Indonesia welcomed into the global community of “free” nations and feted as a model Muslim-majority democracy. And yet, as Hadiz (Citation2003) and Aspinall (Citation2015) have persuasively argued, the peaceful democratic transition came at a price. The price was that the oligarchic interests that had dominated the New Order government were not held to account. No member of the Suharto clan was prosecuted either for abuses of human rights or corruption. The billionaire cronies who had benefitted from Suharto’s patronage were left untouched. And while the military lost some of their formal power and privileges, no generals were court martialled for their complicity in the abuses during the Suharto years. As a result, the network of business, bureaucratic and military groups that had prevailed during the New Order could adapt to the new democratic dispensation, channelling their energies and very substantial funds into political parties, the new vehicles of power and influence.

The failure to reckon with the legacies of the New Order was also apparent in the ideological realm. While P4 had been abandoned, some key aspects of New Order ideology had become deeply engrained after three decades of reinforcement through schooling, the media and public discourse. Political patronage, and the hierarchical and patriarchal norms that underpin it, continued to flourish. The narrative that the military had proved themselves historically to be the ultimate guardians of Pancasila and national unity went largely unexamined, as did the notion that communism represented an ongoing threat to Indonesia. And despite the exuberance surrounding the 1999 elections, there was still a considerable reservoir of public sympathy for the idea that competition among parties espousing different ideologies was not in tune with Indonesia’s national character (Tan Citation2002, 490–491).

The Tide Turns

Less than two years after Suharto’s resignation, democratic cosmopolitanism was already faltering. While the editors of this special issue date the illiberal turn in Indonesian politics to around 2009 (Diprose, McRae, and Hadiz Citation2019), it was clearly foreshadowed in the immediate aftermath of President Wahid’s March 2000 speech in which he apologised to the victims and survivors of the anti-communist massacres of 1965/1966 and went on to signal his support for rescinding the ban on Marxism-Leninism that had been in place since 1966 (Kompas, March 26, 2000). Given that communism in Indonesia had been violently obliterated in the mid-1960s and that the Cold War was over, Wahid’s initiative may appear to have been a relatively uncontroversial step towards democratic liberalisation – only a handful of countries worldwide ban communism. But such was the success of the New Order in publicly associating communism with barbarism, atheism and disloyalty – and such was the frustration with Wahid’s chaotic presidency – that the leaders of virtually all political parties denounced the move. Amien Rais, one of the leaders of the protests against Suharto in 1998, warned that if the ban on communism were to be rescinded the Indonesian Communist Party would return and there would be “hammers and sickles everywhere” (Kompas, April 3, 2000). A few months later parliamentarians from across the political spectrum made a point of attending the annual “Sacred Pancasila Day” ritual commemorating the New Order’s defeat of communism in 1965, signifying not only their eagerness to publicise their anti-communist credentials but also their acceptance of the New Order’s historical narrative (Jakarta Post, September 30, 2000). In retrospect, these episodes are important because they gave illiberal political leaders from the nationalist and Islamic parties common cause with the military, laying the foundations for future co-operation.

Another important cause for doubts about the benefits of reformasi was the rise of violence in the regions, usually sparked by local political competition between ethnic or religious communities. Communal violence in Kalimantan, Ambon and Poso, coupled with the resurgence of secessionist movements in Papua and Aceh, gave rise to fears that democratic freedoms were not only damaging Indonesia’s social fabric but could lead to the disintegration of the country as a unitary state. Military leaders, who had kept a low profile in the reformasi period, began calling for a more assertive response to safeguard national unity. Their rallying cry, “NKRI” (Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia) was adopted by parties across the spectrum, galvanising nationalist sentiment and signalling a revival in the prestige of the military (Mietzner Citation2009, 228–229).

The momentum of the reform movement ground to a virtual standstill during the presidency of Megawati Sukarnoputri (2001–2004). Fearful that the coalition of parties that had forced Wahid’s impeachment would turn against her, Sukarno’s first daughter threw in her lot with the resurgent military who were happy to support her in exchange for a high degree of institutional autonomy (Mietzner Citation2009, 224–228). Megawati also gave her generals great latitude in matters of national security, readily accepting the advice of hardliners to pursue a crackdown in Papua and to launch a full-scale military assault on the rebellious province of Aceh in 2003. Even though she had been a focal point for the resistance to Suharto in the mid-1990s, Megawati’s famous sensitivity to criticism and her frequent appeals to the values of musyawarah, mufakat and “Eastern culture” indicate her affinity with the nativist political culture of the New Order (Bourchier Citation2015, 249).

It was during Megawati’s tenure that Pancasila re-surfaced as a subject of serious debate. As the daughter of Pancasila’s creator, Megawati was keen to see Pancasila rehabilitated, but even she recognised that it raised traumatic memories (Kompas, September 16, 2004). The first attempt to breathe new life into Pancasila came not from Megawati or her generals but from pluralist civil society activists who had spent years criticising the New Order. Dismayed by the spread of violence, intolerance and sectarianism, the reformist Muslim scholar Azyumardi Azra wrote a series of newspaper articles arguing that given Pancasila was Indonesia’s only feasible ideological platform, the time had come to purge it of its New Order past and start work on rebuilding it as a symbol of tolerance and pluralism (see, for example, Kompas, June17, 2004). Azra’s call received strong support from a group of critical intellectuals including human rights lawyer Mulya Lubis, veteran journalist Aristides Katoppo and Jesuit commentator Franz Magnis-Suseno. They made clear their vehement opposition to Suharto’s interpretation of Pancasila which they said had distorted its original purpose as a historical compromise to guarantee pluralism. This pluralist and anti-sectarian reading of Pancasila was articulated clearly by Suseno:

Pancasila represents the agreement of the Indonesian people to build a state in which all citizens are equal, with the same obligations and rights, without discrimination, without concern for religion, without concern for majority and minority status (Kompas, October 3, 2005).

The project to remake Pancasila in a pluralist, democratic image gained some traction in the years after 2004 (see, for example, Latif Citation2011), but was compromised almost as soon as it started thanks to the vocal support the proposal to “revive Pancasila” received from conservative Suharto-era military figures including retired Lt Gen Sayidiman Suryohadiprodjo who expressed delight that the reformasi types had at last seen the truth of what the military had been saying all along (Sayidiman Citation2004).

Incoming President Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono, himself a product of the Indonesian military education system, albeit with a reputation as a reformer, was an unapologetic advocate of bringing Pancasila back into public discourse and into the education curriculum. Yudhoyono sponsored numerous congresses on Pancasila which resulted in another overhaul of the school curriculum geared towards prioritising “Pancasila as the basis of the state and the worldview of the nation” as well as moral education (Bourchier Citation2015, 253). Over the course of the Yudhoyono presidency the government’s framing of Pancasila came increasingly to resemble that of the New Order, with a return to the use of the term “Pancasila Democracy” to describe Indonesia’s system of government (see, for example, Abdulkarim Citation2006). There was also a revival of laws requiring adherence to the “soul and spirit” of Pancasila and an increasing preoccupation with differentiating Indonesian democracy, with its emphasis on musyawarah and mufakat, from liberal democracy.

Blurring the Boundaries Between State and Conservative Islam

In another respect, however, the ideological complexion of the Yudhoyono government was markedly different to the Suharto regime. While it is true that Suharto’s rhetoric and policies in his last few years in power became friendlier towards political Islam, it was under Yudhoyono’s presidency that Islam moved to centre stage and the conditions for the emergence of religious nationalism were put in place. Yudhoyono’s reliance on conservative Islamic political parties to support his ruling coalition led his government to make so many concessions to political Islam that Ricklefs (2012, 259) argues that “it became less a case of the political regime setting the religious agenda than the reverse: religious dynamics shaping the political regime.” The strength of parties including the Islamist Prosperous Justice Party (PKS) and United Development Party (PPP), both at the national and the local level, saw Yudhoyono and his ministers yield to their demands that the state play a more active role in enforcing Islamic morality. During Yudhoyono’s presidency local governments were permitted to introduce sharia-inspired regulations, especially governing personal conduct and dress. Over 150 of these regulations were enacted at the district and municipality level by 2011 even though they were not always enforced (US Department of State Citation2012). In a watershed moment on July 26, 2005 Yudhoyono told the ultra-conservative Indonesian Ulama Council (MUI):

We want to place MUI in a central role in matters regarding the Islamic faith, so that it becomes clear what the difference is between areas that are the preserve of the state and areas where the government or state should heed the fatwa from the MUI and ulama (International Crisis Group Citation2008, 8).

Yudhoyono’s promotion of MUI gave it a level of power and legitimacy it had never previously enjoyed. At the same time, he endorsed a reorganisation within MUI which gave pro-sharia groups including Islamic Defenders Front (FPI) equal standing with the much larger and more moderate Islamic organisations Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama (Scott Citation2016). MUI responded immediately with a muscular fatwa condemning liberalism, secularism and pluralism as “against Islamic teachings” and haram (forbidden) for all believers (Gillespie Citation2007, 223). Yudhoyono’s government did nothing to oppose this fatwa and indeed further validated MUI by appointing the Chair of MUI’s Fatwa Commission, Ma’ruf Amin, to the Presidential Advisory Council. Bush (Citation2015, 247) has argued that Yudhoyono’s reliance on Amin for advice on religious issues does much to explain why “religious politics took such a conservative turn” during his tenure.

The Yudhoyono administration’s accommodating stance towards MUI had direct consequences for Indonesia’s religious minorities. In 2005 MUI issued a fatwa declaring Ahmadiyah to be a deviant sect, leading the vigilante group FPI to attack Ahmadiyah mosques and worshippers in West Java. The Yudhoyono government did little to rein in the attacks, and in 2008 issued a joint ministerial decree forbidding Ahmadiyah members from worshipping publicly on the grounds that they were a deviant sect (Amnesty International Citation2014, 29). This sent a clear message that the state was aligning itself with religious conservatives and that minorities, including Indonesia’s Shia minority, could only expect more trouble if they did not conform to the brand of Sunni orthodoxy backed by MUI.

A further step in the direction of regulating morality was the passing of the 2008 Pornography Law. The original draft of this bill promoted by the PKS and PPP prescribed harsh penalties for a range of behaviours including “adults displaying sensual body parts” and “kissing in public places” but after considerable opposition from provincial legislatures in Eastern Indonesia, nationalist parties and cosmopolitan pluralists the bill was diluted and most penalties reduced (Pausacker Citation2008). The final version of the law, passed with the strong support of both Yudhoyono and conservative Islamist parties, nevertheless introduced significant new restrictions on individual freedoms and has encouraged vigilante groups such as the FPI to conduct their own raids of premises thought to be sponsoring immoral activities. Senior PKS politician Mahfudz Siddiq certainly saw it as a victory for his party’s constituency, calling it a “fasting month present” (Mietzner Citation2013, 188).

The most important marker in the shift towards greater state involvement in upholding religious norms however was the Constitutional Court’s endorsement of the Blasphemy Law in 2010. The law prohibiting blasphemy against the six officially recognised religions had been part of the criminal code since it was introduced by Sukarno in 1965, but it was rarely used over the next three decades. After 1998, however, as the level of political contestation increased dramatically, over 120 people were prosecuted for blasphemy. Some cases were brought by religious minorities but the great majority were used against them, especially the Ahmadiyah and Shia. Following the government’s use of the Blasphemy Law to support its 2008 ban on Ahmadiyah, a pluralist coalition including the Indonesian Legal Aid Foundation and former president Wahid challenged it in the Constitutional Court on the grounds that it contravened the freedom of religion guaranteed by the 1945 Constitution and exposed religious minorities to persecution (Abdi Citation2014, 62–64). Opposing the challenge were not only hard-line groups such as FPI and Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI) but also mainstream organisations Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama that had previously been regarded as supportive of maintaining a separation between state and religion. Central to the case of the defenders of the law was the argument that because Pancasila prescribes “Belief in the One and Only God,” it followed that Indonesia was a theistic state with an obligation to uphold belief in God and to regulate religious practice.

In April 2010, the Constitutional Court issued a decision upholding the constitutionality of the law, accepting the reasoning that Pancasila, as embedded in the preamble of the Constitution, did indeed imply that Indonesia was a theistic state. With one dissenting opinion, the justices also found that the freedom of religion was not absolute. Rather, it should be tempered by what they called keindonesiaan, or Indonesia’s unique national character. Lastly, the justices justified the law because it helped to “preserve public order” (Crouch Citation2012, 39–44).

The Constitutional Court decision authoritatively affirmed the state’s right to determine which groups or individuals had deviated from the officially prescribed religions and therefore its right to rule on questions of religious orthodoxy. It also obliged the state for the first time to compel adherence to religion, paving the way for the legal persecution of atheists. One of the first victims of this was Alexander An, a 30-year-old civil servant who was sentenced to two and a half years in prison for blasphemy in June 2012 after being informed by a judge in a court of first instance in West Sumatra that atheist beliefs were “not allowed under the State ideology of Pancasila” and that the Indonesian Constitution obliged every citizen to believe in God (Amnesty International Citation2014, 21).

The blasphemy ruling and its celebration by most Muslim organisations and parties illustrate how positions that had once been considered marginal or even taboo were now becoming mainstream. As Mietzner (2013, 178) has pointed out, the ruling essentially achieved what the PKS (then known as PK) had wanted in 2000 when it pressed unsuccessfully for a revision of Article 29 of the Constitution to read “The state shall be based on the One and Only God, with the obligation for the followers of each religion to observe the teachings of that religion.” But the ideological shift was not all in one direction. The fact that the ruling was supported not only by Muslim parties but by parties that had always considered themselves nationalist, including Yudhoyono’s Democratic Party and Golkar, points to a significant narrowing of the ideological gap between Islamic and nationalist parties. This appears to have been made possible by a recognition on the part of Islamic forces that nationalist symbols including NKRI and Pancasila could be turned into allies in the struggle for a more Islamic Indonesia – an issue discussed in more detail below. Conservative nationalist party leaders meanwhile had come to view liberalism, atheism and communism as the main threats to the body politic. The product of this unexpected meeting of previously divergent ideological streams was a nascent strain of religious nationalism centred on the notion that the state should take an active role in upholding mainstream religious and cultural norms, and, by the same token, constrain the expression of ideas considered antithetical to these norms. While Menchik (Citation2014) is correct to point to a long history of mainstream support for the suppression of religious heterodoxy in Indonesia, the brand of religious nationalism that began to make itself apparent in the wake of the blasphemy decision was primarily a creature of the conservative politics of the Yudhoyono years. None but the most Islamist of the parties in the cosmopolitan reformasi period argued that the state should be the arbiter of religious orthodoxy with the authority to enforce religiosity on the broad population.

Reinforcing both the authoritarian drift of the Yudhoyono administration and its embrace of the notion of the state as a guardian of conservative values, in 2013 it promulgated a revised version of the New Order’s Mass Organisations Law. The law required all organisations to “maintain the value of religion and Belief in Almighty God” and forbade “blasphemous activities.” It also stipulated that all organisations were obliged to abide by the “spirit and soul of the Pancasila,” which meant that they were prohibited from espousing anti-Pancasila ideas which were explicitly defined as “atheism and communism/marxism-leninism” (Hukumonline Citation2013).

Authoritarian Nativism Resurgent

With Yudhoyono unable to stand again due to constitutional limits on presidential tenure, the 2014 presidential elections in Indonesia saw Suharto’s former son-in-law and special forces commander Prabowo go head to head with the popular Governor of Jakarta, Jokowi. Capitalising on popular discontent with the relatively liberal economic policies of Yudhoyono, both candidates advocated a return to economic nationalism and competed to represent themselves in unabashedly populist terms as the voice of the common people. What distinguished the campaign of Prabowo, apart from its almost bottomless resources, slick advertising and militaristic rallies, was Prabowo’s promise to take Indonesia back to its cultural and political roots. He was openly contemptuous of the “Western-style” political reforms introduced after 1998 and pledged to abandon the democratic amendments to the Constitution and return Indonesia to a system of rule similar to that of Suharto, based on strong centralised leadership and indigenous values. His Gerindra party manifesto was defiantly nativist, committing the party to uphold and implement village traditions of gotong royong and musyawarah claimed to be in line with Indonesia’s national personality. Prabowo was capable of charm and sophistication when speaking to educated elites, but on the campaign trail he engaged in racist and divisive rhetoric, blaming Indonesia’s economic problems on the wealthy Chinese minority. This, together with his alliance with Islamist parties in parliament and his anti-western and anti-communist rhetoric, helped win him the support of openly sectarian groups, including the FPI.

Prabowo lost the election but succeeded in attracting nearly half of voters to Gerindra’s nativist brand of authoritarian populism. He was also bolstered by the fact that the coalition of parties that backed his candidacy enjoyed a substantial majority in parliament, giving him considerable political influence even in opposition. Determined to avenge his election loss, Prabowo was to use his party, military and Islamist networks to pressure the inexperienced president relentlessly, often forcing Jokowi to react in ways that played into his hands.

Jokowi’s narrow election win was welcomed by most analysts, both inside and outside of Indonesia as a triumph for democratic pluralism. Successfully depicting himself as a fresh and pragmatic newcomer, Jokowi’s campaign attracted the backing of those who wanted to preserve the democratic gains since 1998 and who supported an ethnically and religiously inclusive political culture. His association with Megawati’s Indonesian Democratic Party (PDI-P) and his rejection of Islamic extremism also marked him as belonging to the secular nationalist end of the political spectrum. Jokowi’s main preoccupation was with the economy but he did make some early moves towards supporting a pluralist and tolerant Indonesia, promising for instance to address the human rights issues of the past, including the 1965/1966 killings.

Yet thanks to his weak position both within parliament and his own party, Jokowi devoted much of his time in the early years of his presidency firming his political base by cultivating alliances wherever he could. This included seeking the support of political parties that had backed Prabowo, powerful oligarchs and, as detailed in Diprose, McRae, and Hadiz (Citation2019), unreconstructed New Order-era military figures. To the consternation (and, later, dismay) of many of his liberal leaning supporters, Jokowi’s choice of political bedfellows saw his government abandon much of its reformist rhetoric and allow his ministers to indulge in a brand of xenophobic nationalism not far removed from that of his rival. In his first year in office, as McGregor and Setiawan (Citation2019) show, Jokowi not only abandoned his promise to apologise for past human rights abuses but also endorsed the announcement by his defence minister, retired general Ryamizard Ryacudu, of an ambitious training programme called Bela Negara (State Defence). This programme, founded on the notion that modern warfare is primarily ideological rather than physical, aims to instil patriotism, nationalism and Pancasila values into 100 million Indonesians from all walks of life over the next decade. The ideological adversaries stressed in Bela Negara training are the “extreme left,” the “extreme right” (normally meaning Islamic radicalism in the Indonesian context) and liberalism, reprising almost exactly the threat perceptions of Suharto’s security apparatus (Khoemaeni Citation2016).

In an apparent attempt to seize the nationalist high ground and win over Islamic parties and groups, senior government figures went on the offensive against foreign cultural infiltration, launching an unprecedented attack on “deviant” sexualities. In January 2016 Jokowi’s Research and Higher Education Minister Mohammad Natsir called for LGBT-identifying people to be banned from the country’s university campuses (Hegarty and Thajib Citation2016). Same-sex relationships are legal but in the newly polarised and xenophobic atmosphere “LGBT” quickly came to represent the sum of all fears. Ryamizard labelled the emergence of the LGBT “movement” a form of “proxy warfare” even “more dangerous than nuclear war” because it was aimed at undermining the sovereignty of the state (Tempo.com, February 23, 2016; Haripin Citation2016). The anti-LGBT campaign went some way towards neutralising Islamist criticism of Jokowi’s administration, but this did not stop MUI and PKS pressing the government to go further and introduce legislation banning LGBT activity. The fact that several senior government officials joined the chorus against the LGBT “movement,” including Jokowi’s Vice President Jusuf Kalla, suggests that Jokowi was either powerless to resist this fresh attack on values associated with secular liberalism and human rights or willingly acquiesced to it.

Another key issue in which Jokowi has been goaded into action by his enemies is the supposed communist threat facing Indonesia. Communism as an organised force in Indonesia was obliterated in the mid-1960s, with tens of thousands of suspected communists imprisoned without trail and hundreds of thousands of others killed in one of the largest massacres of the twentieth century (Roosa Citation2006, 4). During the Suharto period, accusations of communist sympathies or family connections were routinely used to crush dissent and the 1966 ban on communism remains in force. The current round of anti-communist panic was provoked by the Prabowo campaign in 2014 when it attempted to smear Jokowi by suggesting that he came from a communist family. The pressure continued after the election, with FPI and military elders urging a crackdown on signs that communists, working largely through unsuspecting civil society groups, were secretly planning a political comeback. This prompted police and soldiers, often acting in concert with Islamist vigilantes and Bela Negara cadres, to raid dozens of events they accused of being communist inspired (Belford Citation2016). While Jokowi made some initial attempts to restrain the military and police from zealous action against those suspected of communist sympathies – many of whom were simply holding film screenings or wearing hammer and sickle symbols on t-shirts as fashion statements – he soon decided that there was little to be gained politically by making himself vulnerable to charges that he was defending communism. By May 2016 he had begun actively condoning action against suspected communists and endorsing the statements of his hard-line generals that communism posed an existential threat to Indonesia (Tempo, May 22, 2016). What had started as an attack on Jokowi was in effect co-opted by the president in order to defuse criticism of his government. Jokowi’s apparent unwillingness to defend the principles he had once espoused alienated him from many of his pluralist supporters and demonstrated to his political adversaries how gormless and reactive he could be in the face of public criticism.

Ahok and the Mainstreaming of Sectarianism

The events surrounding the election campaign for the governorship of Jakarta provide perhaps the clearest example of how conservative nationalist politics have intersected with Islamism. In 2012 when Jokowi was running for the position of governor of Jakarta, he chose the pugnacious regional government leader Basuki Tjahaja Purnama – Ahok – as his running mate. Ahok’s background as a Chinese Christian made him something of an exotic creature in Indonesian politics – people of Chinese descent rarely pursue political careers – but, working closely with Jokowi, Ahok quickly established a reputation as an effective administrator in a city that had been plagued by corruption and inefficiency for years. When Jokowi ran for president in 2014, Ahok inherited the mantle of Jakarta governor and later declared his intention to contest the 2017 gubernatorial elections. Running against Ahok were Anies Bawedan, backed by PKS and Prabowo’s Gerindra party, and Agus Yudhoyono, the former president’s son. Early opinion polls gave Ahok the lead, but Baswedan’s campaign was boosted by a concerted effort to mobilise Islamist groups aggrieved by the idea of a “non-believer” ruling over Muslims. On September 4, groups including FPI and HTI organised a 50,000-strong demonstration in Jakarta opposing Ahok on the grounds that a Koranic verse (Almaidah 51) warned Muslims not to support Christians or Jews (Jones Citation2016). Later that month Ahok made the mistake of telling an audience on the campaign trail that his rivals had lied to them “about verse Almaidah 51 and the like” (Jones Citation2016) and asking them to follow their own consciences when deciding who to vote for. When a video of the talk that made it appear that Ahok had criticised the Koran directly was posted online, Islamist groups immediately demanded that Ahok be charged with blasphemy. Soon afterwards MUI issued a fatwa declaring that Ahok should be arrested and prosecuted for blasphemy.

Parties backing Baswedan and Agus took full advantage of this turn of events, joining the call for Ahok to be prosecuted and helping to sponsor a second Jakarta rally on November 4 that attracted a crowd of between 150,000 and 200,000 people (Fealy Citation2016; Jones Citation2016). The government was reportedly alarmed both by the enormity of the crowd and the fervour with which its leaders demanded Ahok’s arrest. They were also taken aback by the rising anti-Chinese tenor of the anti-Ahok campaign both on social media and by Muslim political leaders including Amien Rais, the leader of the National Mandate Party, who had referred to Ahok as “Si Cina Kafir” (The Chinese Infidel) (Fealy Citation2016). Fearful of the political consequences of not bowing to the protesters’ demands, Jokowi saw that he had no alternative but to sacrifice his former colleague and friend, allowing him to be charged under the blasphemy law on November 17.

Despite calls by Indonesia’s largest Islamic organisations for their members to stay away, an even bigger rally was held on December 2, with over half a million people packing the broad thoroughfares of central Jakarta. Even though the rally was peaceful, it was a dramatic show of force that guaranteed that Ahok would be found guilty, regardless of the merits of the case. It also put Jokowi in a corner. Rather than avoid the rally as he had done on previous occasions, Jokowi felt compelled to join the rally’s leaders in prayers, tacitly endorsing a group of Islamist leaders far more radical than the mainstream represented by Muhammadiyah and Nahdlatul Ulama. Once again, as Fealy (Citation2016) observes, “In seeking to defuse the situation, Jokowi … empowered his enemies.”

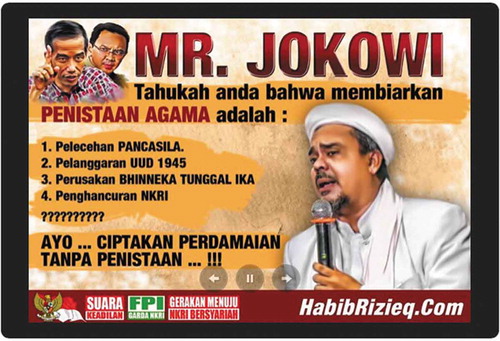

The success of the anti-Ahok protests and Ahok’s subsequent sentencing to two years in prison is widely recognised as an important inflection point in Indonesian politics, marking a sharp deterioration in the quality of democracy.Footnote5 For current purposes, the significance of the Ahok episode and the victory of Gerindra in the Jakarta elections was that it exemplified a successful collaboration between conservative nationalists and radical Islamist politicians. As noted at the start of this article, signs of this alignment of interests were on display during the protests, with much of the iconography and posters used by the protesters distinctly nationalist in flavour. Amid the sea of national flags, two common posters read, in English, “Ahok is the source of nation’s disintegration” and “The Jakarta Governor is National Threat.” Memes published at the time by firebrand FPI leader Habib Rizieq likewise directly linked the FPI’s struggle to have Ahok charged with blasphemy with the central symbols of the Indonesian state (see ).

Caption: MR. JOKOWI

Do you know that ignoring BLASPHEMY

Disrespects Pancasila

Violates the Constitution

Destroys Unity in Diversity [the national motto]

Demolishes NKRI.

?????????

COME ON .… LET’S HAVE PEACE WITHOUT INSULTS …!!

Source: Duile (Citation2017).

The patriotic symbolism surrounding the protests no doubt reflected the priorities of politicians such as Prabowo and Yudhoyono who are rumoured to have provided funding for the rallies in an attempt to leverage Islamic anger and anti-Chinese sentiment to boost public support for their parties (CNBC Asia-Pacific, December 6, 2016). But it also points to an emerging tendency for Islamists to depict their struggle in overtly nationalistic terms, embracing on their own terms the core symbols of Indonesian nationalism including the 1945 Constitution, Pancasila and NKRI.

Conclusion: Religious Nationalism and the Islamisation of Pancasila

There is much about Indonesian political discourse in the Jokowi era that a visitor from the late New Order era would find familiar. Government officials are again warning of the need to resist the dangers posed by the infiltration of foreign culture and ideologies. Anti-communist paranoia is back on the agenda, with daily warnings in the media about the need for vigilance to avert the danger of an imminent communist comeback. Jokowi’s (recently replaced) Armed Forces Commander Gatot Nurmantyo urged a revival of screenings of the 1984 anti-communist propaganda film Pengkhianatan G30S/PKI (Treachery of the G30S/PKI) to a new generation of soldiers and schoolchildren to teach them “what really happened” in 1965 (Saraswati Citation2017). Jokowi’s precipitous banning of HTI in July 2017 was remarkably Suharto-esque, as was the emergency Societies Law he used to do it, a much more draconian iteration of a law introduced by Yudhoyono, complete with sanctions for engaging in “anti-Pancasila activities” (Kompas.com, July 12, 2017).

Yet there are also significant differences. As described above, sweeping democratic reforms were introduced in the aftermath of Suharto’s fall, reflecting the primacy of secular democratic norms and universal human rights by key policymakers during the presidencies of Habibie and Wahid. These hard-won reforms governing elections, the makeup of parliament, freedom of speech and freedom to organise are woven into the fabric of politics and, while some have been eroded, they continue to enjoy legitimacy in most parts of the political spectrum. As well as being more democratic, Indonesia is also more Islamic, both in the private and public spheres. As documented by Fealy and White (Citation2008), Heryanto (Citation2014) and others, society as a whole has become more pious in its religious practice, with public expressions of Islamic identity, from headscarves to Islamic banks to popular films, more evident than ever before. Salafist groups have proliferated across the archipelago, successfully promoting, as Chaplin (Citation2017) has shown, an exclusively Islamic concept of citizenship. Islamic political parties, severely constrained during the Suharto era, are very active participants in public life and have been a part of every ruling coalition in the post-New Order period. As demonstrated, the tradition since independence of keeping Islam at arm’s length from the state, has gradually faded, with Yudhoyono going further than any previous president to empower conservative Muslim interests and integrate them into his administration. During Yudhoyono’s tenure sharia regulations proliferated across the archipelago, laws governing morality were tightened and the blasphemy law was not only increasingly used against minorities but also formally endorsed by the Constitutional Court. The mobilisation of Islamist groups during the 2017 Jakarta election raised the stakes dramatically, with radical groups, in league with conservative nationalist figures, effectively asserting veto power over democratic and legal processes.

There have also been significant developments regarding interpretations of Pancasila. Even though this topic often seems opaque to outsiders, it is of considerable importance in Indonesia because Pancasila remains the symbolic soul of the state. As described above, Pancasila, having been used for decades to proscribe all leftist, liberal and Islamic opposition to the Suharto regime, was, in the early reformasi period, relegated to the margins of political discourse. There was an attempt by reformers to redefine it as a symbol of tolerance, equality and pluralism, but this was overtaken when Yudhoyono’s administration revived a nativist, anti-liberal reading of Pancasila that highlighted the indigenous cultural roots of Indonesia’s democracy. Islamists also attempted to infuse Pancasila and other nationalist symbols with new meanings. There is a long history of Muslim suspicion and antagonism to Pancasila because of the way it came to stand, especially in the New Order years but also until the present, for a secular nationalist view of the state as opposed to an Islamic one. The Constitutional Court’s 2010 judgement that Indonesia was, by virtue of the fact that Pancasila stipulated “Belief in the One and Only God,” a religious state with an obligation to intervene to protect religious values stood this view on its head. Once considered one of the main impediments to the struggle for a more Islamic state, Pancasila came to be seen as a key catalyst, with Islamic figures from across the political spectrum making the case. FPI leader Habib Rizieq declared in 2012 that:

The first article of Pancasila has to be viewed as the most fundamental teaching of Islam, that is, the Tauhid (the oneness of Allah) …. Therefore, this article serves as the basis for the implementation of the commands and laws of Allah as the one and only God (cited in Munabari Citation2017, 249).

Translated into a meme, Rizieq’s message was blunter: “In a Pancasila state, Islamic law is not only possible and permissible but OBLIGATORY because the essence of Pancasila is Tauhid ….” (HabibRizieq.com). The normalisation of this new perspective on the Pancasila is reflected in the statement by M.N. Harisudin, a regional leader of the traditionally moderate Nahdlatul Ulama in East Java, who told his audience in 2016 “A state based on Pancasila fulfils all the conditions to be called an Islamic state” (Muslimmedianews, May 5, 2016).

Less successful but equally illuminating have been attempts to load other nationalist motifs with Islamic meanings. Rizieq has argued that the concept of musyawarah, which forms part of the fourth principle of the Pancasila and which is typically associated with indigenous village tradition, in fact derives from Islamic tradition reaching back to the time of the Prophet. As Wilson (Citation2015, 2) has observed, Rizieq’s agenda in making these arguments was to cast democracy as an infidel ideology and return Indonesia to its supposedly authentic Islamic constitutional foundations. In a similar vein are the efforts by the high-profile pro-sharia umbrella group Islamic Community Forum (Forum Umat Islam), to promote the concept of “NKRI Bersyariah” or the “Unitary State of the Republic of Indonesia in accordance with sharia.” This slogan was coined by Muhammad Al-Khaththath, secretary-general of Forum Umat Islam and a former leader of HTI, in response to criticisms from more moderate Islamic organisations that HTI’s advocacy of a caliphate in Indonesia was anti-nationalistic (Munabari Citation2017, 248).

On one level these developments might be seen as helping resolve the tension between Islam and the state ideology that has bubbled under the surface of Indonesian politics since 1945. But the Islamisation of Pancasila can also be viewed as brazen co-optation with little regard for the spirit of compromise between religions that it embodied when Sukarno formulated it in 1945. It is clear that some Muslim groups, including but not limited to the FPI, take the view that reframing Pancasila as an affirmation that Indonesia is a religious state enables and indeed necessitates a thoroughgoing transformation of Indonesia’s laws to bring them into line with religious values.

The ruling of the Constitutional Court in the blasphemy case has made this possible. It effectively opened the door for any law to be challenged on the grounds that it is not in tune with religious norms. A case before the Constitutional Court seeking to outlaw all sex outside of marriage is instructive here. In early 2016 a group of academics and preachers under the banner of the Family Love Alliance (Aliansa Cinta Keluarga Indonesia) petitioned the Constitutional Court to overhaul three articles of the Indonesian criminal code dealing with extra-marital sex (Jakarta Post, August 30, 2016). Calling on the testimony of many expert witnesses, they made the case that Indonesia’s relatively permissive laws relating to extra-marital sex inherited from the Dutch had no place in a religious state based on Pancasila. During the proceedings Constitutional Court Justice Patrialis Akbar is reported to have agreed with the petitioners that:

Our freedom is limited by moralistic values as well as religious values. This is what the declaration of human rights doesn’t have. It’s totally different [from our concept of human rights] because we’re not a secular country; this country acknowledges religion (Suryakusuma Citation2016).

Patrialis was backed by Professor Arief Hidayat, whose position as the chief justice of the Constitutional Court placed him at the pinnacle of the legal hierarchy. “International-universal values” he argued, had no standing in his court because they were derived from an understanding of the state as separate from religion (Kompasiana.com, October 6, 2016). After more than a year of hearings the nine-member bench voted to reject the petition in December 2017. While the ruling was welcomed in liberal circles, it was hardly decisive. Five judges rejected the petition on the grounds that the court could only review laws, not make them. The other four, including the chief justice, issued a dissenting opinion arguing that because Pancasila is the “source of all sources of law” and that the first and highest principle of Pancasila is Belief in the One and Only God, it followed that Indonesian laws “must not conflict with the values, norms and laws of God” (Mahkamah Konstitusi 2017, 454). The dissenting justices also based their decision on a novel interpretation of Article 28J of the Constitution which, they maintained, demonstrated that Indonesia had a “konstitusi yang berketuhanan” (Godly Constitution) requiring all laws to be in line with “religious values and teachings.” (Mahkamah Konstitusi Citation2017, 456).Footnote6

These statements by Constitutional Court justices provide a valuable and somewhat alarming insight into the thinking of Indonesia’s foremost interpreters of the Constitution. If the chief justice is of the view that human rights-based arguments are meaningless and that Indonesian law is based on divine law, then it follows that any law is open to challenge on the grounds that it does not reflect religious sensibilities. Carried through to its logical conclusion, this would challenge the positivist basis of the entire legal system and give much more power to those, such as MUI, purporting to define what is, was, and was not in accordance with religious teachings. The 2017 decision by the Constitutional Court constraining the central government’s authority to revoke regional regulations, hundreds of which are sharia-inspired, only adds to the sense that the historic 1945 consensus that the Indonesian state should be neutral in matters of religion no longer holds and that secular law and pluralism are on the retreat in Indonesia (Jakarta Post, September 9, 2017).

It would be wrong to conclude that Indonesia is on the road to becoming a theocratic autocracy. Numerous electoral contests and opinion polls over the years have shown conclusively that most Muslims in Indonesia do want to live in an Islamic state (Menchik Citation2017). Respect for democratic institutions remains high and as Warburton and Aspinall (Citation2017) have noted, nobody is seriously attacking elections, opposition parties or civic space as has happened, for instance, in Thailand. It must also be acknowledged that the upsurge of sectarianism has been met with resistance from a vocal pro-pluralist community who not only speak out regularly in the media but have held counter demonstrations and vigils (albeit much smaller) in favour of preserving religious freedoms and tolerance.

Yet it is clear that the ideological centre of gravity has shifted. Indonesia is now less democratic, less pluralist and less cosmopolitan than it has been since 1998. Both the government and the opposition increasingly define themselves in opposition to the secular and liberal values that are dismissed as being of the West. The pluralism and inclusivity that Jokowi once espoused are a thing of the past as he has repeatedly compromised with his enemies, leading him to adopt an increasingly narrow and xenophobic agenda. The success of Prabowo in marrying his nativist brand of authoritarian populism with Islamist sectarianism, helping to facilitate a new conservative religious nationalism, has created a new dynamic in Indonesian politics. Whether or not this coalition prevails in the 2019 presidential elections, it has changed the ideological landscape in Indonesia in ways that have made it increasingly difficult to defend publicly secular law, pluralism, democracy and human rights.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank New Mandala and Timo Duile for their permission to use an image and is grateful to Vedi Hadiz and the reviewers for their valuable comments on the manuscript. Any shortcomings are mine.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. Ideologies, according to Freeden (Citation2005, 119), attempt “the decontestation of the essentially contestable”; they attempt to impose authoritative definitions, “however fleeting,” of concepts and key words.

2. This is the longest running dispute in Indonesian politics. Islamic law advocates typically reference an episode on the eve of the proclamation of independence in August 1945 when a group of nationalist leaders quietly – and they say unfairly – removed wording in the preamble of the Constitution that would have obliged the state to uphold Islamic law for Muslims (Elson Citation2009).

3. The five principles, coined by Sukarno in 1945, are usually translated as belief in one supreme God; just and civilised humanity; national unity; democracy guided by the inner wisdom of unanimity arising out of deliberations among representatives; social justice for the whole of the Indonesian people.

4. The full text of Supomo’s speech appears in Kusuma (Citation2004, 124–131) with extracts translated in Feith and Castles (Citation1970, 188–192). An analysis of the speech, and of the concept of integralism (also called organicism) can be found in Bourchier (Citation2015).

5. The Economist Intelligence Unit’s Democracy Index 2017 (2018) downgraded Indonesia from 48th to 68th position largely as a result of Ahok’s blasphemy case (see also Jones Citation2017).

6. Article 28J (2) of the Constitution lists “morality” and “religious values” among factors limiting the enjoyment of individual rights and freedoms. The argument that Indonesia has a “Godly Constitution” (original in English) was novel in the context of the Constitutional Court but drew on a 2015 book by Indonesia’s pre-eminent constitutional lawyer (and first chief justice of the Constitutional Court) Professor Jimly Asshiddiqie (2015, 85).

References

- Abdi, S. 2014. “Islam, Religious Minorities, and the Challenge of the Blasphemy Laws: A Close Look at the Current Liberal Muslim Discourse.” In Religious Diversity in Muslim-majority States in Southeast Asia: Areas of Toleration and Conflict, edited by B. Platzdasch and J. Saravanamutu, 51–74. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Abdulkarim, A. 2006. Pendidikan Kewarganegaraan untuk Kelas XI Sekolah Menengah Atas [Citizenship Education for Year 11 Senior High School]. Bandung: PT Grafindo Media Pratama.

- Ali, As’ad Said. 2009. Negara Pancasila: Jalan kemaslahatan berbangsa [The Pancasila State: The Pathway to Beneficial National Life]. Jakarta: LP3ES.

- Amnesty International. 2014. Prosecuting Beliefs: Indonesia’s Blasphemy Laws. London: Amnesty International.

- Aspinall, E. 2015. “The Surprising Democratic Behemoth: Indonesia in Comparative Asian Perspective.” The Journal of Asian Studies 74 (4): 889–902.

- Asshiddiqie, J. 2015. Gagasan Konstitusi Sosial: Institusionalisasi dan Konstitusionalisasi Kehidupan Sosial Masyarakat Madani [The Social Constitution: The Institutionalisation and Constitutionalisation of Civil Society]. Jakarta: LP3ES.

- Belford, A. 2016. “Indonesia’s Gotta Catch All the Communists.” Foreign Policy, August 12. Accessed November 14, 2017. http://foreignpolicy.com/2016/08/12/indonesias-gotta-catch-all-the-communists/.

- Bourchier, D. 2015. Illiberal Democracy in Indonesia: The Idea of the Family State. London: Routledge.

- Bourchier, D., and V. Hadiz, eds. 2003. Indonesian Politics and Society: A Reader. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

- Bush, R. 2015. “Religious Politics and Minority Rights during the Yudhoyono Presidency.” In The Yudhoyono Presidency: Indonesia’s Decade of Stability and Stagnation, edited by E. Aspinall, M. Mietzner, and D. Tomsa, 239–257. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Chaplin, C. 2017. “Organisations like Wadah Islamiyah Envision an ‘Islamic’ Citizenship for Indonesia.” Inside Indonesia 129, July–September. Accessed November 14, 2017. https://www.insideindonesia.org/islam-and-citizenship-3/.

- Crouch, M. 2012. “Indonesia’s Blasphemy Law: Bleak Outlook for Minority Religions.” Asia Pacific Bulletin 146, January 26.

- Diprose, R., D. McRae, and V. Hadiz. 2019. “Two Decades of Reformasi: Indonesia and its Illiberal Turn.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (5).

- Duile, T. 2017. “Reactionary Islamism in Indonesia.” New Mandala, April 17. Accessed December 21, 2018. http://www.newmandala.org/reactionary-islamism-indonesia/.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. 2018. Democracy Index 2017: Free Speech under Attack. London: The Economist Intelligence Unit.

- Elson, R. 2001. Suharto: A Political Biography. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Elson, R. 2009. “Another Look at the Jakarta Charter Controversy of 1945.” Indonesia 88: 105–130.

- Fealy, G. 2016. “Bigger than Ahok: Explaining the 2 December Mass Rally.” Indonesia at Melbourne, December 7. Accessed February 4, 2017. http://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/bigger-than-ahok-explaining-jakartas-2-december-mass-rally/.

- Fealy, G., and S. White, eds. 2008. Expressing Islam: Religious Life and Politics in Indonesia. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Feith, H., and L. Castles, eds. 1970. Indonesian Political Thinking, 1945–1965. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Freeden, M. 2005. “What Should ‘Political’ in Political Theory Explore?” The Journal of Political Philosophy 13 (2): 113–134.

- Freeden, M. 2010. “Review of Social and Psychological Bases of Ideology and System Justification.” Political Psychology 31 (3): 479–482.

- Gellert, P. 2015. “Optimism and Education: The New Ideology of Development in Indonesia.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 45 (3): 371–393.

- Gillespie, P. 2007. “Current Issues in Indonesian Islam: Analyzing the 2005 Council of Indonesian Ulama Fatwa No.7 Opposing Pluralism, Liberalism, and Secularism.” Journal of Islamic Studies 2 (18): 202–240.

- Habibie, B. J. 2003. “President B.J. Habibie: A New Beginning.” In Indonesian Politics and Society: A Reader, edited by D. Bourchier and V. Hadiz, 295–301. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

- HabibRizieq.com. Homepage of FPI leader Habib Rizieq. Accessed August 10, 2017. [Since suspended, but much content reproduced at RedaksiIslam.com http://redaksiislam.com/category/berita-fpi/page/42/.]

- Hadiz, V. 2003. “Reorganizing Political Power in Indonesia: A Reconsideration of So-called ‘Democratic Transitions’.” The Pacific Review 16 (4): 591–611.

- Hadiz, V. 2004. “The Failure of State Ideology in Indonesia: The Rise and Demise of Pancasila.” In Communitarian Politics in Asia, edited by Chua Beng Huat, 148–161. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

- Haripin, M. 2016. “Ryamizard’s Proxy Wars.” New Mandala, March 8. Accessed November 20, 2017. http://www.newmandala.org/ryamizards-proxy-wars/.

- Hegarty, B., and F. Thajib. 2016. “A Dispensable Threat.” Inside Indonesia 124, April–June. Accessed 17 November 2017. http://www.insideindonesia.org/a-dispensable-threat/.

- Heryanto, A. 2014. Identity and Pleasure: The Politics of Indonesian Screen Culture. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Hukumonline. 2013. “Undang-undang Republik Indonesia Nomor 17 Tahun 2013 Tentang Organisasi Kemasyarakatan” [Indonesian Statute No.17 2013 on Social Organisations]. Hukumonline. Accessed August 21, 2017. http://www.dprd-diy.go.id/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/UU_NO_17_2013.pdf.

- International Crisis Group. 2008. “Indonesia: Implications of the Ahmadiyah Decree.” Asia Briefing 78, July 7.

- Jones, S. 2016. “Why Indonesian Extremists are Gaining Ground.” The Interpreter, November 1. Accessed November 17, 2017. https://www.lowyinstitute.org/the-interpreter/why-indonesian-extremists-are-gaining-ground.

- Jones, S. 2017. “Indonesia’s Illiberal Turn.” Foreign Affairs, May 26. Accessed November 17, 2017. https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/indonesia/2017-05-26/indonesias-illiberal-turn.

- Khoemaeni, S. 2016. “Gerakan Ekstrem Kanan dan Kiri Sasar Generasi Muda” [Movements of the Extreme Right and Extreme Left Target the Young Generation]. Okezone.com, August 25. Accessed October 3, 2016. https://news.okezone.com/read/2016/08/25/337/1472749/gerakan-ekstrem-kanan-dan-kiri-sasar-generasi-muda/.

- Kusuma, A. ed. 2004. Lahirnya Undang-Undang Dasar 1945: Memuat Salinan Dokumen Otentik Badan Oentoek Menyelidiki Oesaha-2 Persiapan Kemerdekaan [The Birth of the 1945 Constitution: Authentic Documents of the Investigative Committee for Independence Preparations]. Jakarta: Badan Penerbit Fakultas Hukum Universitas Indonesia.

- Latif, Y. 2011. Negara Paripurna: Historisitas, Rationalitas, dan Aktualitas Pancasila [The Comprehensive State: Historicity, Rationality and Actuality of Pancasila]. Jakarta: Kompas Gramedia.

- Mahkamah Konstitusi Republik Indonesia. 2017. Putusan Nomor 46/PUU-XIV/2016 [Supreme Court Decision No.46/PUU-XIV/2016]. http://www.mahkamahkonstitusi.go.id/public/content/persidangan/putusan/46_PUU-XIV_2016.pdf.

- Maynard, J. 2013. “A Map of the Field of Ideological Analysis.” Journal of Political Ideologies 18 (3): 299–327.

- McGregor, K. 2007. History in Uniform: Military Ideology and the Construction of Indonesia’s Past. Singapore: Singapore University Press.

- McGregor, K., and K. Setiawan. 2019. “Shifting from International to ‘Indonesian’ Justice Measures: Two Decades of Addressing Past Human Rights Violations.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (5). DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1584636.

- Menchik, J. 2014. “Productive Intolerance: Godly Nationalism in Indonesia.” Comparative Studies and Society and History 56 (3): 591–621.

- Menchik, J. 2017. “Is Indonesia’s ‘Pious Democracy’ Safe from Islamic Extremism?” The Conversation, July 5. Accessed November 7, 2017. https://theconversation.com/is-indonesias-pious-democracy-safe-from-islamic-extremism-79239/.

- Mietzner, M. 2009. Military Politics, Islam and the State in Indonesia: From Turbulent Transition to Democratic Consolidation. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.

- Mietzner, M. 2013. Money, Power and Ideology: Political Parties in Post Authoritarian Indonesia. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Morfit, M. 1981. “Pancasila: The Indonesian State Ideology According to the New Order government.” Asian Survey 21 (8): 838–851.

- Munabari, F. 2017. “Reconciling Sharia with ‘Negara Kesatuan Republik Indonesia’: The Ideology and Framing Strategies of the Indonesian Forum of Islamic Society (FUI).” International Area Studies Review 20 (3): 242–263.

- Pausacker, H. 2008. "Hot debates: A Law on Pornography Still Divides the Community". Inside Indonesia, October–December.

- Ricklefs, M. 2012. Islamisation and Its Opponents in Java: A Political, Social, Cultural and Religious History, c. 1930 to the Present. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Roosa, J. 2006. Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup D’état in Indonesia. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Saraswati, P. 2017. “Alasan Panglima TNI Gelar Nobar G-30S/PKI” [Why the Military Commander is Setting up Group Viewings of G-30S/PKI]. CNN Indonesia, September 18. Accessed January 30, 2019. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/nasional/20170918190450-20-242571/alasan-panglima-tni-gelar-nobar-g-30s-pki?

- Sayidiman. 2004. “Rejuvenasi Pancasila” [Rejuvenation of Pancasila]. Personal Website of Sayidiman Suryohadiprojo. June 23. Accessed November 12, 2017. http://sayidiman.suryohadiprojo.com/?p=255.

- Scott, M. 2016. “Indonesia: The Battle Over Islam.” The New York Review of Books, May 26.

- Simanjuntak, M. 1994. Pandangan Negara Integralistik: Sumber, Unsur, dan Riwayatnya dalam Persiapan UUD 1945 [State Integralism: Sources, Foundations and History in the Constitutional Debates of 1945]. Jakarta: Pustaka Utama Grafiti.

- Suharto. 1988. Suharto: Pikiran, Ucapan dan Tindakan Saya: Otobiografi seperti dipaparkan kepada G. Dwipayana and Ramadan K.H. [SuhartoSoeharto: My Thoughts, Words and Actions: An Autobiography as told to G. Dwipayana and Ramadan K.H.]. Jakarta: PT Citra Lantoro Gung Persada.

- Suharto. 2003. “Pancasila, The Legacy Of Our Ancestors.” In Indonesian Politics and Society: A Reader, edited by D. Bourchier and V. Hadiz, 103–109. London: RoutledgeCurzon.

- Suryakusuma, J. 2016. “‘Zinaphobia,’ Homophobia and the ‘Bukan-Bukan’ State.” Jakarta Post, September 7. Accessed November 17, 2017. http://www.thejakartapost.com/academia/2016/09/07/zinaphobia-homophobia-and-the-bukan-bukan-state.html.

- Tan, P. 2002. “The Anti-Party Reaction in Indonesia: Causes and Implications.” Contemporary Southeast Asia 24 (3): 484–508.

- US Department of State. 2012. International Religious Freedom Report for Indonesia 2012. Washington, DC: Department of State.

- Warburton, E., and E. Aspinall. 2017. “Indonesian Democracy: From Stagnation to Regression?” The Strategist, August 17. Accessed December 4, 2017. https://www.aspistrategist.org.au/indonesian-democracy-stagnation-regression/.

- Wilson, I. 2015. “Resisting Democracy: Front Pembela Islam and Indonesia’s 2014 Elections.” In Watching the Indonesian Elections 2014, edited by U. Fionna, 32–40. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies.