ABSTRACT

The legacies of Cold War authoritarianism in Thailand have continued to the present, including in the conduct and the outcome of the 2019 general elections. In this article it is argued that not only did Cold War precedents like the 1969 general election help shape this lineage, but the practices of Cold War authoritarian regimes in Thailand, including the promotion of “lazy” forms of capitalism based heavily on absolute value strategies, shaped development and the labour force in ways that have also contributed to enduring authoritarian tendencies. This argument is made by reviewing the underpinnings of the 1969 election as well as by reviewing how Thailand’s industrial and labour force structures evolved in this particular authoritarian context, contrasting the Thailand case with that of Cold War South Korea.

In May of 2019, the Electoral Commission of Thailand (ECT) finalised the distribution of parliamentary seats, and thus the likely results of the April election, doing so in the way the military dictatorship in power since 2014 had wanted: the military’s party, Palang Pracharath, could form a coalition with numerous smaller – and over-represented – parties to control the House (the lower chamber), meaning that the military coup regime could effectively remain in power, while purporting to have a “democratic” mandate. This result was produced in spite of the Thaksin Shinawatra-connected Peua Thai Party (PT) winning the most seats. The elections featured a number of procedural irregularities, and without various forms of electoral manipulation and the ECT’s invention of seat allocation rules after the voting, Palang Pracharath would possibly have lost to PT or a coalition of PT and the new – and popular – Future Forward Party (Anakhot Mai). Over its five years of unfettered rule, the military regime had engaged in manoeuvres to weaken PT before the elections and to ensure its dominance of the post-“election” political landscape, the junta brought charges of violating election laws against Future Forward and its leader, Thanathorn Juangroongruangkit, raising the possibility that the party would be disbanded by the politicised Constitutional Court.Footnote1 Finally, the fact that the coup regime selected the 250 members of the Senate (the upper chamber) ensured that the parliament would function as the military wanted; and, lest it did not, the threat of a military coup loomed ever present during the proceedings.Footnote2

Few Thais would remember, but the 2019 election was eerily reminiscent of an election 50 years earlier, the 1969 “demonstration election” organised to perpetuate the rule of the Thanom Kittikachorn military regime (see Thareerat Citation2019). As in 2019, in 1969 the military and royalist elites had conducted the election not out of respect for democratic principles but to try to convince the world that the leadership had a popular mandate; as in 2019, in 1969 the regime overseeing the run-up to the election put in place a Senate comprising unelected “representatives” whose role was to make sure that the parliament acted only in ways approved by the elites; and as in 2019, in 1969 the elites who ran the elections engaged in various manipulations of procedure – and attempted manipulation of public opinion – to try to ensure the voting results in advance, though in both cases they failed to achieve their maximal objectives (showing that the majority of the population did not in fact support them). In 1969, the demonstration elections called for by the elites and their US backers resulted in a minority government, and after two years of attempting to make that government do its bidding, the same military elites who had promoted the elections overthrew the parliamentary regime and re-installed a military dictatorship. In 2019, the elections occurred in the wake of two previous military coups (the 2006 coup against Thaksin’s Thai Rak Thai Party and the 2014 coup against PT), along with the 2008 removal of a Thaksin-linked government (led by the People’s Power Party, PPP) through a judicial manoeuvre backed by the military, making it clear to all voters in 2019 that the “wrong” electoral result would likely lead to another coup. The 1969 elections had taken place amid the Cold War and the US War in Vietnam, which were often used as excuses for authoritarianism, yet in 2019 Thailand still seemed stranded in its authoritarian past.

The ongoing and often tragic saga of political authoritarianism in Thailand has a variety of origins. While some of these lie within distinctively Thai social structures and practices, with their own very long histories, others manifest the gestation of specific forms of authoritarianism during the Cold War, under US tutelage. Hewison (Citation2020) reviews some of the interactions between US and Thai leaders that fuelled the growth of Thai authoritarianism during the 1950s, interactions that derailed the moves toward greater democratisation associated with the political projects of Pridi Banomyang and his followers. This article picks up the story of US-Thai interactions from the late 1950s into the early 1970s, explaining how this ongoing Cold War collaboration drove the development of full-blown military dictatorship.

In particular, this article reviews the manipulations involved in the 1969 demonstration election, designed to effectively legitimise a Cold War-era military dictatorship and present it as having democratic credentials that it, in reality, lacked. The effort both succeeded (the military’s party won a plurality of seats) and failed (military leaders felt they could not govern in the ways they wished through this plurality), thus setting in motion another coup. In this sense, the 1969 election both perpetuated patterns of authoritarian rule that continue to the present and served as a precedent for the 2019 demonstration election.

In this analysis, I also attempt to add a dimension, here, to the story of Thai authoritarianism and its reproduction into the post-Cold War present. The authoritarian state in Thailand not only perpetuated itself but also a form of “lazy capitalism,” based on the entrenched privileges of military, royalist, and capitalist elites, as well as the repression of labour and maintenance of a “low-wage” regime. Fundamentally a “low-road” strategy of capitalist development, lazy capitalism involves strategies of accumulation based more heavily on extraction of absolute surplus value than the strategies built more heavily on relative surplus value that were adopted in some neighbouring Cold War-era authoritarian states, such as South Korea. While labour issues are sometimes seen as peripheral to political structures, I argue that the suppression – and later fragmentation – of labour organisations by the 1960s and 1970s authoritarian regime has itself contributed directly to the power and endurance of political authoritarianism in Thailand through the effects it has had on forms of political push back against authoritarianism.

This argument is pursued through relational comparison. The military dictatorship in South Korea, spawned under Cold War circumstances not dissimilar to those in Thailand, was in part undermined, in the 1980s and 1990s, by its success in fomenting an industrial project that featured large, powerful industrial firms with large and eventually very militant workforces. The strength of Korean labour struggles, and of broad social solidarity with them, added a dimension to the struggles for democratisation in South Korea that was partially missing from struggles in Thailand. While workers in Thailand did in fact struggle, sometimes with considerable militancy, their organisations were weaker and more fragmented than in South Korea by the 1980s and 1990s, and the solidarity they received from more privileged middle classes was less significant than in South Korea, where the combination of labour militancy and struggle against dictatorship led by the 1990s to a process of democratisation that has proven more resilient so far than the democratisation achieved in Thailand during the same decade. Collaboration between US and Thai elites during the 1960s and 1970s contributed to this outcome by encouraging the growth of a more structurally static political economy, in which Thai capitalists prospered through sweatshop tactics more than through technological innovation and growth of industrial capacity, which in turn limited the growth of the kind of labour force that sparked democratisation struggles in South Korea by the 1980s and 1990s. In this sense, Thailand’s long run of political authoritarianism has been enabled by Cold War processes in a double sense: it has been fuelled both by transnational elite collaboration in maintaining a directly authoritarian political order and by the weaknesses in organised labour and social solidarity that resulted from the development projects these elites promoted.

This argument is presented in four parts. In the first, some developments in the Thai political regime under Sarit Thannarat (1957-1963) are noted briefly, including the political legacies this left for the successor regime of Thanom Kittakachorn (1963-1973). The second part traces one of the major Thai-US projects for maintaining political authoritarianism during the Thanom years, a covert operation code-named Lotus, which not only legitimised and enabled ongoing authoritarian rule but internalised and reflected various transnational elite biases that would shape politics for decades to come. In the third section, I briefly note some of the ways that this authoritarianism stunted the growth of Thai industry and industrial labour, stimulating growth that was satisfactory to capitalists, albeit with limited structural transformation—a very different “East Asian economic miracle” than the one occurring during the same period in South Korea. In the fourth part, it is demonstrated that this stunting of labour and industrial development in Thailand has influenced the forms of struggle against authoritarianism in Thailand—ultimately in ways that are detrimental by comparison to developments in South Korea. In the conclusion, I reflect on the implications of this analysis for ongoing democratisation struggles in Thailand.

Political Authoritarianism under the Sarit Regime (1957–1963)

As Hewison (Citation2020) notes, collaboration between US and Thai elites in the early Cold War period undermined the democratic projects of Pridi Banomyang and the People’s Party, leading to the empowerment of military figures under the formal leadership of Phibul Songkhram (1947–1957). Phibul’s two main underlings and competitors for power, Phao Sriyanon (connected most closely with the CIA) and Sarit Thanarat (connected most closely with the US military), jockeyed for position during the 1955–1957 period, at a time when the US leadership was increasingly committed to war in Vietnam and increasingly concerned that its allies not “do business” with the People’s Republic of China (PRC). While both Phao and Sarit were staunchly anti-communist, Phao betrayed certain liabilities in relation to the China containment agenda, having allegedly developed connections with Chinese communists.Footnote3 US leaders became concerned, in this context, that both Phao and Phibul might “go soft” on containment, the latter in part because he might still harbour some sympathy for his former ally Pridi, living in exile in the PRC. This strengthened Sarit’s hand, and when he launched a coup against Phibul in 1957, US leaders quickly endorsed his leadership.

Sarit subsequently launched an auto-coup in 1958, immediately upon his return from medical treatment in the USA, tearing up the existing constitution and establishing a draconian dictatorship in which labour unions and virtually any political opposition groups were banned, while the media were muzzled. US leaders were unambiguously happy about this outcome. Ambassador U. Alexis Johnson (Citation1959), reflecting on Sarit’s ascent and US support for it, argued for the benefit of his diplomatic colleagues that:

the problem of explaining to the American people and to friendly nations which are not sympathetic toward an authoritarian form of government why we support such governments becomes a matter of public relations, not of policy. We need not, for example, feel self-conscious about our support of an authoritarian government in Thailand based almost entirely on military strength … aside from the practical matter of Thailand’s not being ready for a truly democratic form of government, it can be pointed out that the United States derives political support from the Thai Government to an extent and degree which it would be hard to match elsewhere. Furthermore, the generally conservative nature of Thai military and governmental leaders and of long-established institutions (monarchy, Buddhism) furnish a strong barrier against the spread of Communist influence. Moreover, the Thai military rule does not weigh onerously on the people …

The notion that Sarit’s regime did not “weigh onerously on the people” was convenient rationalisation (Darling Citation1965, 187–188; Thak Citation2007). Yet it became standard fare not only for US diplomats and political operatives but for modernisation theorists – such as Walt Rostow and Samuel Huntington – who argued by the 1960s that military dictatorships (those supported by the US) could serve as appropriate forces for modernisation and development in societies of the Third World (see Tadem Citation2020; Törnquist Citation2020). Whatever one makes of these arguments today – and clearly Huntingtonian arguments about eventual democratisation of military-led development regimes is called into question precisely by Thailand’s experiences – Sarit did not really spend long enough in power to set Thailand fully on a clear-cut developmental trajectory, though he did launch not only a number of specific projects (for example, rural road-building campaigns) but a rhetoric of development (khwam pattana) that was to be consequential for decades after his death (see Chairat Citation1988; Mills Citation1999; Thak Citation2007).

In addition, the Sarit regime launched the politically consequential deployment of aggressively pro-royalist rhetoric, encouraging the young King Bhumibol Adulyadej to tour the country regularly and make himself known to the general population as a leader and benefactor of the people. This was not a simple matter of rolling stones downhill, since up to the late 1950s many people in rural Thailand knew little about the monarch and did not necessarily see him as a leading figurehead of the state. The campaigns undertaken from the Sarit era forward, especially throughout the 1960s, were to change this. As one US participant in these campaigns, US Information Service officer Paul Good (Citation2000) has stated:

We had a program [in Northeast Thailand] which had been instituted with the purpose of solidifying the ties behind their king … We were in effect a PR [public relations] unit for the Thai government. We would pass out pictures of the king. We would put up posters which had public health themes. We had comic books, which had anticommunist themes … The purpose was to show the people that the King was thinking of them and taking care of them and listening to what they had to say, on the theory that if the people were supportive of the King, that he would be the binding force, the focal point for all attention, and there wouldn’t be any susceptibility to the Communist influence which was coming in on the Laotian and Cambodian sides from Vietnam. That was the theory.

Through campaigns such as these, the monarchy and military came to be joined at the hip, working in co-ordinated fashion to promote the kind of political regime US counterinsurgents and Thai elites saw as conducive to their agendas. Thus, by the time the USA was manoeuvring Thanom into position for the 1969 demonstration elections, the king had himself emerged as a significant player within USA-Thai strategies. As a Johnson administration briefing book for the king’s 1967 visit to the USA put the matter: “ … the King is a serious and articulate spokesman for his people. We believe his visit will contribute to our mutual objectives by demonstrating that an independent country in Southeast Asia with an ancient tradition of preserving its independence sees things in that part of the world in much the same way as we do” (Johnson Administration Citation1967).

The deep collaboration between US counterinsurgency specialists, the Thai military, and the monarchy had been set in motion under Sarit’s rule, but with that rule cut short by Sarit’s 1963 death, it fell to Thanom, who took over leadership, to spearhead much of the 1960s anti-communist, pro-royalist development campaign.

The Thanom Regime (1963–1973): Entrenching Political Authoritarianism

Sarit left several complicated legacies for his successors, one of the most complex of which had to do with issues opened up by the inheritance struggles of his heirs and various wives. Because of their personal contest over his fortune, Sarit’s will became public, and in the process it was revealed that far from being a non-corruptible leader, Sarit had in fact stolen a fortune estimated (in 1963 figures) at around US$140 million dollars (Thak Citation2007, 223–225). This placed certain formal constraints upon Thanom, who felt compelled by these revelations to confiscate Sarit’s wealth and promise to clean up corruption in government.

Yet Sarit’s legacies included others that made Thanom’s promises to clean up corruption challenging to fulfil. When he tore up existing constitutions in 1957 and 1958, for example, Sarit had formally promised to have a new one promulgated by 1965 – a promise that neither his regime nor its US backers took too seriously, both sides being comfortable with rule by military decree under the 1959 martial law “constitution.” Nonetheless, when Thanom took power, the public environment of concern over corruption made it difficult for the regime to continue to stall on writing a new constitution, so Thanom pledged that his regime would produce one to meet the original target date of 1965, eventually doing so in 1966. Given the ability of the elites to control the constitution writing process, this need not have been a threat to authoritarian rule, but Thanom and his allies worried that the new constitution would likely allow for some form of elected lower chamber and thus for opposition political parties. This raised the spectre of how the military regime could support an electoral process while remaining firmly in control of the state.

Historically, in Thailand as elsewhere in the world, strong regimes that wished to stay in power through electoral processes could accumulate financial capital from various sources and use this to directly or indirectly buy the election outcome. In Thailand, previous rulers had sometimes accumulated capital – for elections or other purposes – through expedients such as raiding the resources of the state’s Lottery Bureau. But Sarit’s will, in revealing his corrupt practices, made this risky for Thanom, should he have to run for election, since much of the public would be alert to such tactics. Thanom saw another financial possibility, namely, to tap the powerful Sino-Thai business community for electoral support, but this had the drawback of leaving Thanom indebted to these supporters (for a variety of potential favours), a form of indebtedness Thanom wished to avoid (Glassman Citation2018, 424–425). Because of these constraints, Thanom and his backers approached their US allies with a proposal that they fund a party through which Thanom could run for office, one that would have enough financial power to guarantee success. US leaders, particularly Ambassador Graham Martin, found this proposal agreeable, and thus was born Operation Lotus, a secretly-funded project to form, on Thanom’s behalf, the Saha Pracha Thai (SPT) party (see Martin Citation1968; Weiner Citation2008, 297–298, 351–352).

Lotus was approved by the US National Security Council’s (NSC) 303 Committee, in late 1965, and it was renewed in various stages during 1967 and 1968 (National Security Council Citation1965, Citation1969; Bundy Citation1968). The various stages of renewal corresponded to phases in the covert negotiations over details of the project, including over what amounts to spend on SPT at what points in the run-up to the election, which was eventually held in 1969. Among the issues being discussed and negotiated by the US and Thai participants were how to ensure that the electoral results would prevent control over the lower chamber by parties opposing the US war in Vietnam or favouring egalitarian development measures. (An unelected upper chamber would be in place, regardless of the election outcomes.) Uncertainty about the ability of the Lotus project to ensure these outcomes led not only to opposition to elections in some ruling-class quarters but to hesitation and lack of enthusiasm even on the part of actors who were generally in favour of holding the elections. Thanom, for example, seemed to favour elections but was only willing to hold them in so far as the US would fund the SPT and try to ensure his continued rule; and Ambassador Martin himself was notably unenthusiastic about proceeding with the elections as they neared, stating in 1968 simply that “we now have the Constitution … [so] elections will have to be held.” Martin also saw, however, potential for an elected elite ruling bloc to emerge that would conform to US aspirations for not only Thailand and the US war effort but for the region more generally. As he put the matter, the ruling party envisioned:

is about the maximum of “unity” one could logically expect. The convolutions within that framework will be intricate, competitive, complex, and in all of Asia, would be exceeded in deviousness only by the Javanese. Despite this, there is also a remarkable consistency and cohesion, which we have seen demonstrated over the past decade. There is really nothing in Asia to match it.

Members of the Thanom entourage were not always confident in this kind of outcome. They could promise their own allegiance to the US war in Vietnam, something Martin saw as crucial “if American policy still includes among its goals a post-Viet-Nam Southeast Asia not under Chinese hegemony, either truly neutral or aligned with us in some way yet to be defined” (Martin Citation1968). Moreover, the banning of the Communist Party ensured there would be no Leftist opposition in the parliament. Yet Thai leaders nonetheless worried about communists expressing their own anti-war agenda through legal parties (NSC Citation1965); and they also feared that groups such as those they dubbed “extreme egalitarians” would try to “take from the rich and obstruct the kind of rapid economic development taking place in Bangkok and spread the money evenly over the entire population,” a project they claimed “would be exploited by the Communists” (NSC Citation1968).

CIA analysts chipped in with similar concerns. While they noted that the existing constitution and electoral process “virtually ensures that the present leaders will be in power for the foreseeable future,” they also worried that infighting within the SPT would weaken it and allow for forces allied with the exiled Pridi to re-emerge (CIA Citation1968). More generally, they feared, as did their allies in Thanom’s camp, that the elections would allow for too much open criticism of the way power was organised and distributed in Thai society:

A thin and often indistinguishable line separates criticism of the corrupt practice of government leaders from a more fundamental questioning of the way in which Thailand is ruled. Some potentially influential elements in the capital are beginning to ask whether the close relationship between government leaders and business interests is a good thing for the country.

CIA analysts also worried that such antagonism might be fuelled by a sense of economic and regional inequity:

Although Thailand has made considerable economic progress under the military regime, and its growth rate compares favorably with that of other nations, the fact remains that its per capita income is still extremely low. There are some people in Thailand, although they are few in number and exercise only marginal influence, who are asking whether the country’s economic gains are being made in the right areas and are reaching the right people … [and] the opposition will almost certainly argue the economic issue along the long-standing battle lines separating Bangkok and the central plain from the other major regions.

These concerns, along with worries that the election might become a referendum on the US war in Vietnam, led to a less than ringing endorsement of democratic elections and ensured that there would be a full-fledged effort to use covert funding as a means to secure a desired outcome.

In the event, that outcome was partly secured: the SPT officially won the 1969 elections, receiving a plurality of the seats in the lower chamber, 105 out of 219 seats, after which it formed a majority government through coalition with other parties (IPU Citation1969, 73–74). This outcome, however, did not satisfy the demands or aspirations of the ruling elite, the lack of a straight SPT majority preventing them from simply forcing through all the legislative measures they desired. By 1971, representatives of the Thanom regime such as Foreign Minister Pote Sarasin were asking US Embassy officials to endorse a repeat of Lotus, hoping to hold new elections that would yield a majority in the lower chamber (Unger Citation1971; Johnson Citation1971). Failing to get US support for a repeat covert performance, however, Thanom’s forces simply overthrew the elected government in another coup, reporting to US officials that they had tried but found that in Thailand “democracy doesn’t work” (NSC Citation1971; Weiner Citation2008, 351). Officials in the Nixon administration found nothing to object to in all this, agreeing to recognise and support the military coup government on the grounds that the regime would continue to support US foreign policy objectives (Kissinger Citation1971).

Two years after the 1971 Thanom coup, the popular uprising of October 1973 helped oust the military regime from power, though after three years in exile Thanom returned to the country, on the back of the 1976 coup and military violence (Flood Citation1977; Anderson Citation1977). Through all of these episodes, and more that were to come, US support for the Thai ruling elite never wavered, while that ruling elite’s commitment to maintaining itself in power by whatever means necessary also remained unwavering.

The longer-term result of this has been a deep political conservatism, especially in the outlooks of the elites themselves, who – since they have been generally successful in maintaining themselves in power and have engaged in violence against political opponents with impunity (Haberkorn Citation2018) – have incessantly repeated mantras about the virtues of “political stability” (read: their own rule), under a royalist version of authoritarian developmentalism. Thus, while Thailand has been heralded for its high rates of gross domestic product (GDP) growth since the early 1950s, the country’s politics has been marked by perpetual military coups and authoritarian rule. There was a coup against a civilian government in 1947 and dictatorship or authoritarian rule from 1947 to 1973, another coup against a civilian regime resulting in authoritarian rule from 1976 to 1988, a coup in 1991 against the civilian regime and military rule until 1992, a coup against the civilian regime in 2006, with military rule until 2007, a military-supported judicial ouster of the elected government in 2008 with rule by an unelected regime from 2008 to 2011, a coup against the elected civilian government in 2014 with a military dictatorship until 2019, and an ongoing attempt by the military leadership to ensure that the 2019 elections maintained them in power. Conservative analysts, ignoring various costs of perpetual military rule, have been fond of citing Thailand’s experience to show that successful capitalist development is possible under an authoritarian regime (see, for example, Muscat Citation1994). Thailand’s authoritarian developmentalism, however, has arguably stunted not only political but also economic and social growth in Thailand, as will be argued in the next section.

Thailand’s “Economic Miracle” in the Mirror of Regional Growth

Even before the 1969 election, Thailand’s previous decades of authoritarian rule had developmental costs. Among them was that a military, business, and royalist elite satisfied with the profits that could be extracted from high rents, high interest rates, and sweatshop labour, failed to push Thai capital into the kinds of industrial projects that were beginning to more deeply transform countries such as South Korea and Taiwan. This was never simply a matter of narrow individual policy choices and instead reflected basic features of the class structures of the different Cold War states.

To use the Korean case as an example in contrast, while the most powerful factions of capital in post-World War II South Korea included the burgeoning industrial capitalists (Cumings Citation2005, 308), in Thailand Sino-Thai bankers, merchants and agribusiness capitalists were the dominant grouping (Hewison Citation1989; Glassman Citation2018, 415–417). This difference would have consequences both for patterns of economic growth and state policies. Some of the consequences could already be witnessed in the 1960s, when the World Bank contracted with the South Korean firm, Hyundai, to the build a highway in southern Thailand, in a context where there were no local firms capable of doing adequate highway construction work (Glassman Citation2018, 433–435). Indeed, so weak was Thai industrial capacity as US Vietnam War spending began to pour into Asia that the vast majority of military procurement contracts in Thailand went to US companies – a very different reality than in South Korea, where most contracts went to Korean-owned firms (Glassman Citation2018, 495–497). Indicative in this regard, too, was the difference in the profile of exports to Vietnam during the war: in the case of South Korea, more than 50% (by value) were manufactured goods; in the case of Thailand, some 75% were composed of rice (Naya Citation1971, 42–45). This is a particularly striking phenomenon given that the Korean peninsula had suffered considerable war destruction during the 1950s and also had a more limited natural resource base than Thailand; so the differing 1960s export profiles speak to considerable economic stasis in Thailand, in contrast to the dynamism of South Korea.

Unlike Thailand, South Korea in the 1960s–1990s was to become, for many analysts, an exemplar of a “developmental state” – a state that disciplines capital, and particularly financial capital, to drive rapid growth of key industries (Amsden Citation1989; Kim Citation1997; Chang Citation2003). Certain aspects of the neo-Weberian analysis of developmental states can be called into question (see Chibber Citation2003; Hart-Landsberg, Jeong, and Westra Citation2007; Chang Citation2009); but there is no doubt that the South Korean state under the Park regime engaged in policies such as expropriating the private banks and forcing credit into key industries at very low – sometimes negative – real interest rates (Woo Citation1991, 159–169). There is also no doubt that the Thai state did not engage in any such disciplining of financial (or even industrial) capital during the 1960s–1990s, maintaining instead a regime that largely protected the major banks from competition, even collaborating with them on major financial policies, and maintaining high interest rates and interest rate spreads, even in contexts where the state was ostensibly placing ceilings on lending rates (Hewison Citation1989, 188; Glassman Citation2004, 119–121). Given the power of banking capital, it is in fact inconceivable that Thai state leaders would have had the desire, much less the ability, to engage in the kind of “financial repression” that characterised the South Korean developmental state. In this sense, the differential trajectories of financial policies in South Korea and Thailand from the 1960s forward were not merely the result of different choices by state leaders but reflected significant differences in the class and class-fractional structures of the two countries.

Similar points can be made about differences in the agrarian class structures of the two countries. Policies toward agriculture in Thailand during the Cold War, reflecting the power of landed elites and agribusiness, placed the large population of agrarian producers at a considerable disadvantage. A tax on rice exporters (the rice premium), which was passed down by the exporters and millers to rural producers, was implemented between 1955 and 1985, draining considerable surplus out of agriculture, to the advantage of urban-industrial employers, who could pay their workers lower wages because of rice prices that were subsidised by the premium (Medhi Citation1995, 46–47). By the 1970s, conditions for farmers who needed to rent land were extremely difficult because of low incomes, high interest rates for loans, and high rents. This generated a massive rural movement, the Peasant Federation of Thailand (PFT), developed in part to promote a land rent control act put in place by the civilian government in 1974. The response of rural landowners and the state security services that had gestated under Cold War authoritarianism was a campaign to destroy the PFT, including the assassination of a large number of its leaders (Turton Citation1978; Citation1987, 40–41). This campaign of rural violence was in many ways a prelude to the spectacular violence against students and urban workers in Bangkok during 1976 (Bowie Citation1997, 21–33).

While conditions for South Korean farmers in this period were by no means idyllic, a land reform undertaken in the 1950s, in part under the political pressure generated by land reform in North Korea, secured somewhat less onerous conditions for Korean farmers (Cumings Citation2005, 269–270, 439). Moreover, when the Park regime wished to strengthen its position vis-à-vis rural producers in the 1970s it did so primarily via the co-optive (if highly conservative) Saemaul Undong movement that – while underpinned by the authoritarian state’s potential for violence – did not rely so directly on military force to generate development and political allegiance.

A number of scholars have noted some of these crucial differences between South Korea and Thailand, particularly the differential power of financial capital and the differences in agricultural policies, and some thus suggest that Thailand had a weaker developmental state (Doner Citation2009). Others reject the notion that Thailand should be considered as having had a developmental state (Glassman Citation2004, Citation2018). However one sorts out this partly conceptual issue, it is clear that the kinds of industrial growth that occurred in Thailand and South Korea from the 1960s forward have been quite different, the South Korean trajectory being toward the sorts of heavy and nationally-owned industries encouraged by the South Korean developmental state – steel, construction, ship-building, automotive, and the like – while the trajectory in Thailand has been more mixed, with a variety of “lighter” industries (textiles, electronics assembly) maintaining a higher profile for a longer period of time, and investment in industries such as automobiles and higher-technology products being driven disproportionately by foreign investors and their global production networks (Pasuk and Baker 2008).

Again, the differences cannot likely be attributed to atomised individual choices by policymakers. Nonetheless, as the previous section has highlighted, choices were made by state leaders, and their international allies, regarding issues such as the political forms and processes of contestation that would be allowed – their decisions leading to outcomes such as electoral manipulation, perpetuation of military dictatorship, and violence against popular organisations struggling for reform. These were themselves to have non-trivial consequences for the general political economy of development as well as the specific structures of labour and political struggle.

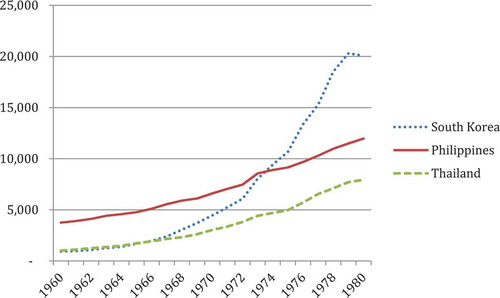

This can be explained by noting the different paths taken by South Korean and Thai capital in the 1960s, and the relationship of this to class structures and forms of state power. In South Korea, the authoritarian Park regime aggressively pursued industrial growth, and it did so with a special emphasis on projects such as attempting to build a national steel industry (Amsden Citation1989, 292–316). This general emphasis, and the specific opportunities for military contracting opened to Korean capital during the Vietnam War helped push very rapid rates of manufacturing growth in South Korea (see ). This outcome was one for which the Park regime had to struggle – both against certain propensities of Korean and Japanese capitalists and against certain preferences of US planners, who were not originally trying to promote the growth of an industrial behemoth in South Korea. Nonetheless, the general push to “modernise” industry by both Korean state planners and various social groups who had been forcibly displaced from older social structures by the Korean War, lent a certain amount of class dynamism to the process (Cumings Citation2005, 301–302; Glassman Citation2018, 259–378).

In Thailand, by contrast, the Cold War alliance between US and Thai elites generated a greater degree of class stasis, in which existing political, military and economic leaders attempted to maintain the status quo, while allowing the economy and specific industries to grow without aggressive developmentalist efforts like those undertaken by the Park regime. Because of this, even as Thailand’s economy began to boom in the Cold War era there was neither any attempt by the state to push financial capital into specific industrial sectors nor any attempt to undermine any of the polarising socio-spatial tendencies that marked the growth process (Glassman Citation2004, 119–124). To the contrary, the Thai state both harshly disciplined labour (as did the Korean state) and subsidised the accumulation of capital by the most powerful Thai class fractions, especially in the banking sector (Hewison Citation1989, 188). The result was a form of rapid economic growth without dramatic structural transformation of the sort that was occurring in South Korea, and with high rates of profit for both bankers and the sweatshop industries like textiles to which they lent (Glassman Citation2004, 106). In short, the Thai state fomented lazy capital – capitalists, whether or not they were connected directly or indirectly to the Crown and the military, who relied heavily on extracting absolute surplus value from labour through long work days and high rates of exploitation, rather than relying more heavily on technological innovation, upgrading, and greater extraction of relative surplus value (Glassman Citation2018, 510).

The results of this lazy capitalism can be illustrated by noting the inter-connections between maintenance of a large, poor agrarian labour force and the maintenance of a low-wage sweatshop regime. In particular, the relationship between labour productivity and wages was highly unfavourable for workers during the Cold War. The squeeze on agrarian surplus, affecting land-poor farmers the most, pushed many producers out of agriculture and into the urban labour force, where the growth of industrial employment opportunities was substantial but did not pull more agrarian workers in because it did not generate adequately rapid industrial (and industrial wage) growth.Footnote4

Indeed, during the entire Cold War period, wages in Thailand remained remarkably flat, despite tremendous growth in industrial productivity. During the period of the most intensive collaboration between Thai and US elites between 1947 and 1972, real daily wages either stagnated or fell, declining slightly over the entire course of the 1960s. Even after a period of modest wage growth in the late 1970s, the overall picture between 1960 and 1990 was that wages increased a mere 1.5 times while GDP increased nine times; and United Nations Industrial Development Organization (UNIDO) data indicate that even in the last half of that period, from 1975 to 1990, the share of manufacturing wages in value added (MVA) declined from 24.7% (already 10 percentage points lower than the average for 28 countries studied by UNIDO) to 22.7% (UNIDO Citation1992, 45). Among the results of all this were not only extraordinarily high profits for manufacturers but the enormous overall income and wealth disparities that have marked Thai development to the present (Glassman Citation2004, 161–168; Pasuk Citation2016; Credit Suisse Citation2018, 156).

This outcome in Thailand was neither accidental nor simply a matter of market forces, as the state and capital consciously and aggressively executing practices of repression toward organised labour, including its banning, indicates that a policy of weakening industrial labour and promoting social polarisation was actively pursued. This was also seen in the assassination of PFT leaders and the defeat of land rent control. Even policies designed to be somewhat compensatory and stabilising, such as the labour union project pursued by USAID and the government from 1967 to 1972, in the context of the constitutional reforms discussed above, served primarily to have the regime afford minimal recognition to conservative unions while fragmenting the labour movement in ways making effective, militant organisation difficult (Hewison and Brown Citation1994; Glassman Citation2004, 86–88).

South Korean Cold War-era policies toward organised labour were at least as repressive as those of the Thai state. Not only did leading South Korean industrialists like Chŏng Chu-yŏng of Hyundai and Yi Pyŏng-ch’ŏl of Samsung abhor labour unions but the highly authoritarian Yushin constitution and “Big Push” campaign of industrialisation launched by Park in the 1970s enabled very harsh treatment of Korean workers (Ogle Citation1990, 117–125; Koo Citation2001; Glassman and Choi Citation2014). But in part because of a successful industrial dynamic that the South Korean state and capitalist class could not entirely control, wages began to rise more in line with increases in productivity during the 1980s and 1990s, resulting in wages far higher than in Thailand. For example, by the early 1980s, UNIDO data indicate that the share of wages in MVA was 27% in South Korea, while it had dropped to under 21% in Thailand. By the second half of the 1990s, moreover, real annual wages for textile workers were US$11,084 in South Korea and US$2,910 in Thailand (Glassman Citation2018, 509). These differences do not merely reflect differences in organising efforts by Thai and Korean workers, though they do reflect differing levels of effectiveness in labour push back (see below).

Additionally, the development of middle-class technical strata was significantly different in the two countries, reflecting the differing forms of industrial development. In Thailand, the relative class stasis generated by lazy capital and elite satisfaction with the political structure contributed to limited investment in productivity enhancing technologies and education. Complaints about the limits of Thailand’s technological and engineering capacities, relative to its rates of economic growth, are standard fare in both media and scholarship. One figure from the end of the Cold War era can be taken here as indicative: in the mid-1990s, Thailand had only 0.2 research and development scientists per capita, while South Korea boasted 2.9 (Glassman Citation2004, 183). More broadly, South Korea had developed a much stronger intermediate goods sector than Thailand by 1990, an indication of a more industrially variegated and complex economy than in Thailand, where not only was the industrial structure less developed but about half of the population remained dependent on agricultural and related forms of labour, compared to less than 20% in South Korea (Glassman Citation2018, 506; OECD Citation1999).

This kind of difference in industrial/class structure manifests a subtler but hugely important difference between Thailand and South Korea. In Thailand, the social space that separates “middle classes” – primarily better paid professionals, bureaucrats, intellectuals, and small business owners – from poor agricultural producers and poorly paid workers has remained very large, even as the country’s economy has boomed. This is reflected not only in the greater income and wealth disparities but in the attitudes toward villagers and workers adopted by more privileged groups (especially in Bangkok) during the political upheavals of the last two decades (Walker Citation2012; Keyes Citation2014). These social differences do not have a precise parallel in contemporary South Korea (at least in their scale and virulence), in spite of there being no small amount of “middle class” conservatism (see, for example, Koo Citation2001, 126–136). As a result, when South Korean farmers and workers have struggled for better wages and working conditions (and/or more democracy) they have found substantial numbers of allies among various middle-class professional groups such as students, journalists, salaried company workers, and others. Indeed, in sharp contrast to Thailand, scholars like Roger Janelli (Janelli and Yim Citation1993, 81–88, 231) have found not only considerable pro-democracy sentiment among these employees but a surprising amount of critical distrust of the giant chaebol for whom many of them work – a phenomenon that links many of these white-collar and middle-class workers to the blue-collar industrial workers that led the 1987 Korean labour uprising.

This suggests that important differences in the political economy of South Korean and Thai development in turn shaped the forms and outcomes of struggles against political authoritarianism. What I have flagged here is that, to an extent, South Korean development in the 1960s–1990s was less burdened than was Thai development with lazy capitalists (and their cadres) who relied habitually on repression (at least in the final instance) to maintain a low-wage sweatshop regime. Certainly, South Korean capitalists and the state practiced considerable repression against labour and leftist political groups, but when their own success at capital accumulation had generated a large and militant organised labour movement, centred in locations such as Hyundai’s factories (Koo Citation2001, 153–187), Korean capital proved capable of responding to wage increases with technological upgrading that lifted productivity, thus maintaining the power of capital over labour through a relative surplus value strategy, more so than the comparatively absolute surplus value-oriented strategy prevalent in Thailand throughout the Cold War period.

Political Push Back and Post-Cold War Authoritarianism

The reason this kind of class-structural political economic consideration is important is that authoritarian political regimes cannot be considered capable of routinely reproducing themselves over time. The degree of push back from popular movements conditions the degree to which authoritarianism is either supplanted or refurbished. The fact that authoritarianism has been weakened considerably in South Korea while it has been more resilient in Thailand demands explanation, and the class-structural political economic differences cited here, stemming in part from the different decisions of the two Cold War authoritarian regimes, provide a first-cut explanation of the differing outcomes. Class-structural differences do not exist apart from political-ideological dimensions of class formation and struggle, however. Here a few elements of the important ideological differences between some middle-class advocates for democracy in South Korea and Thailand in the 1990s are flagged, with the differences also reflective of Cold War authoritarian legacies.

In South Korea, an ideological umbrella for the labour and democracy movements that developed in the 1980s and 1990s was the notion of minjung, broadly, “the people” (Shin Citation2006, 167–175; Koo Citation2001, 142–152). While this is a notion with strong ethno-nationalist underpinnings and even some conservative possibilities antagonistic to class politics, in the context of struggles against chaebol dominance, military dictatorship, and US imperialism, the notion came to express a certain unity between blue-collar workers, white-collar workers, students, farmers, and any others who could see themselves as struggling collectively to rid themselves of their han – their “long accumulated sorrow and regret over … misfortune” or “simmering resentment over injustice” (Koo Citation2001, 136). In a sense, this broad unifying construction of exploitation enabled, and was enabled by, a shared sense of misfortune across the different segments of the labour force whose development had brought them socially closer together by the 1980s.

In Thailand, during the 1970s, there was a similar sense of shared injustice among some groups of farmers, workers, and students, who were active in pushing for land rent control, a higher wage regime (with a record number of strikes during 1973–1976), and the strengthening of democracy. However, as Anderson (Citation1977) noted, important elements of the middle classes turned against the social movements in the mid-1970s, enabling the authoritarian state’s violent repression of these movements in 1974–1976, capped by the massacre at Thammasat University in 1976 (also see Ockey Citation2004, 160). The Thammasat massacre has parallels with the South Korean state’s violent repression of broad-based pro-democracy struggles in Kwangju during 1980 (Bell Citation1978; Cumings Citation2005, 382–386); but the longer-term outcomes of the two events illustrate the differing political trajectories of the two authoritarian regimes, with the Kwangju massacre serving as a catalyst for the spread of the minjung movement (Janelli and Yim Citation1993, 73; Koo Citation2001, 102–103; Shin Citation2006, 168–169).

In Thailand, as important elements of the middle classes peeled away from workers’ and farmers’ struggles in the mid-1970s, the form of nationalism that was especially important in structuring middle-class discourse was royalist, overtly hierarchical in its sensibilities and a nationalism which eventually gave birth to ideas like settakit por piang, or “sufficiency economy,” King Bhumibol’s conservative, anti-welfare state ideology that counsels satisfaction with what one already has (Glassman, Park, and Choi Citation2008; see also Hewison Citation1997). Social struggle was by no means quelled by the violence of 1976 and the ensuing collapse of the Communist Party of Thailand. But when a new cycle of social struggle emerged in the early 1990s, Thai labour groups were not as strongly favoured by broad social solidarity as were labour organisations in South Korea. The Thai labour movement itself was comparatively weak and fragmented and union density extremely low; its strongest base was in the state enterprises, and rightly or wrongly many professionals and wage workers were prone to see these state enterprise unions (and in fact most other unions) as corrupt and self-serving, rather than as representative of the broader interests of “the people” (Glassman Citation2004, 88–92). When popular protests broke out against the military’s attempt to remain at the head of the political system in 1991, many workers (especially from Bangkok suburbs) were involved in night-time actions to try to undermine the regime (Ockey Citation2004, 164–166). Yet middle-class activists involved in the mass protests that eventually turned back the military regime in May 1992 solipsistically referred to the protest group as the meu teu mop (mobile phone mob), elevating their own status in the protests while airbrushing blue-collar workers out of the picture, even when those workers had paid the largest price in lives lost during the May massacre by military and police (Ockey Citation2004, 165–166).

When the military coup regime was sent back to the barracks in 1992, many middle-class activists, along with royal publicists, credited King Bhumibol with the restoration of democracy, giving a boost to misguided notions of “royalist liberalism” and amplifying the voices of those middle-class activists promoting royalist nationalism (Connors Citation2008). Tellingly, the political process that was opened by these events was wilfully dominated by people from the professional classes, who arrogated to themselves the business of writing the new 1997 constitution: only those with college degrees could participate in the drafting process (Connors Citation2007, 162). And when the new constitution could not prevent the meltdown of the economy in 1997, many middle-class activists also turned to settakit por piang as a purported answer to the structural problems of the economy (Pasuk and Baker Citation2000).

In this sense, whereas South Korean political society had become both more industrially variegated and more open to class coalitions and class-relevant contestation (even granting here the enduring salience of different forms of class bias), Thai political society was more structurally polarised and dominated at the top by the class privileged – even in a context where there was significant conflict between military/royalist elites and the emerging middle-class forces favouring democratisation. This becomes especially clear when one contrasts developments in Thailand with the political developments in South Korea in the aftermath of the 1980 Kwangju massacre. In 1987, the Great Labour Uprising rocked South Korea. The uprising came on the heels of a pro-democracy rebellion by students (Koo Citation2001, 154–156), and rather than simply meeting with more state repression the labour uprising effectively helped kindle a broad social upheaval, involving students, salary workers, and social actors from around the country who had wearied of military dictatorship, at least some of whom sympathised with the struggles of workers for better working conditions and more workplace democracy (Cumings Citation2005, 372–382). The formal political result of these struggles was a civilian government under Kim Young-Sam in 1993, and eventually the election of two centre-left governments, those of Kim Dae-Jung in 1998 and Roh Moo-Hyun in 2003 (Cumings Citation2005, 396–402; Doucette Citation2010, Citation2013a, Citation2013b).

It is worth reflecting on differences between the kinds of opposition parties that came to power at the end of the 1990s in the two countries. In South Korea, reflecting the increased power of organised labour and the general solidarity of a popular (minjung nationalist) movement involving a variety of actors from society, the ultimate expression of the overcoming of Cold War dictatorship – even as the Cold War on the Korean peninsula continued – was the election of Kim Dae-Jung, the bete noir of the dictators and an ally of the labour movement, as well as the most famous proponent of peaceful resolution of conflict with North Korea through the “Sunshine Policy” (Cumings Citation2005, 500–504; Moon Citation2012). In Thailand, by contrast, the stunted development of capitalism led to a situation where a capitalist, Thaksin Shinawatra, who favoured changes that would turn Thailand into a more fully capitalist state with a more robust group of domestic consumers, emerged as an opposition figure and quickly came to be considered a mortal enemy of the ruling elite, particularly the military and monarchy. Thus, the Thai Rak Thai Party, elected in 2001 in the wake of the 1997 economic crisis, sponsored programmes that would increase consumption (through debt moratoriums for farmers and indirect subsidies such as the national health insurance system), and in doing so quickly ran afoul of military, royalist, and business elites. These elites were backed in no small degree by various professionals and non-governmental organisation activists who claimed to revile Thaksin’s corruption but also clearly reviled what they saw as “uneducated” Thai Rak Thai supporters (see Keyes Citation2014; Somchai Citation2016). The 2006 coup against Thaksin, which has opened more than a decade of ongoing political chaos and recurrent military repression, was the answer offered by authoritarians and royalist nationalists to what they see as an excess of democracy (Glassman Citation2010, Citation2011; Pavin Citation2014).Footnote5

In South Korea, while the political right-wing fought back aggressively against centre-left regimes, and finally regained the presidency in 2008, leading to two successive conservative (and even pro-Cold War) regimes, the strength of popular movements has at points hampered the efforts of the Right, and in 2017 these popular forces succeeded in impeaching the regime of Park Chung Hee’s daughter, Park Geun-Eye, returning a (weakly) centre-left government under Moon Jae-In to office (Kim Citation2017). This is not to say that the left and the labour movement in South Korea have failed to suffer serious blows during the last two decades – they surely have, whether in the form of offshoring and attacks on labour by the chaebol or in the form of state policies attempting to equate opposition to conservative parties with North Korean espionage (Doucette and Koo Citation2014). Moreover, they face the constant difficulty of overcoming the obstacles generated by US military policies, including US insistence on continuing to use South Korea as a base to threaten the PRC (Pilger Citation2016).

Yet all of this simply reinforces the argument that democratisation struggles have had somewhat deeper impacts in rolling back authoritarianism in South Korea than in Thailand, where the latest round of coup and military dictatorship (2014–2019) was capped by an election eerily reminiscent of the 1969 election, with massive advance efforts to stack the deck in favour of the military’s party and ongoing manipulation and threat of another coup in its aftermath. And once again, in the present, organised labour is too weak and disorganised to put its own alternatives forward with any political clout, while much of the population – particularly key elements of the middle classes – continues to debate development and democracy without substantial participation by workers (see Kriangsak Citation2018). Both South Korea and Thailand still bear the scars of Cold War authoritarianism, and in South Korea the Cold War has never ended. Yet in Thailand, the authoritarian state’s Cold War-repression of popular forces continues without the excuse of an ongoing Cold War; and its past “successes” in repressing opposition and strengthening the hand of lazy capitalists has ensured that authoritarianism continues to thrive even without the existence of a communist enemy.Footnote6

Conclusion: Push Back or Blowback?

The argument put forward here is not that “the past didn’t go anywhere” or that history is simply repeating itself. The fact that authoritarianism in South Korea has led in different directions than in Thailand, with differing forms of push back, is itself evidence of this. Instead, what I am signalling is that authoritarianism is not a simple phenomenon with unvarying consequences. The specific forms of authoritarian rule matter and need to be interrogated. This includes interrogation of their structural foundations and consequences.

In Thailand, moreover, the idea that the past can simply repeat itself may well be more an elite conceit than a serious social possibility. To be sure, the fascist environment sweeping much of the planet, combined with the seemingly limitless tolerance that Thai authoritarian elites have come to expect from an “international community” that largely remains mute about their human rights abuses, might suggest that the 2019 elections will result in the reinforcement of military rule the elites want. Yet other signs are not so promising for these elites. While the years of dictatorship helped vault Thailand to the ranks of the world’s most polarised economies, with the top 1% of the wealthy controlling an estimated 66% of national wealth (Credit Suisse 2018, 156; see also Hewison Citation2019), the economy as whole has not performed particularly well: the OECD estimates that Thailand’s GDP grew at an average annual rate of 3.4% between 2012 and 2016, 3.9% in 2017, and 4.1% in 2018. This has been a lower rate of growth than for any of the other ASEAN-10 (Association of Southeast Asian Nations) countries except Brunei, and far lower than either China or India (OECD Citation2019, 1). Failure in human rights terms is one thing, but failure in capitalist terms may well generate antagonism even on the part of some lazy capitalists. It has certainly generated a new wave of social antagonists among the younger groups of professionals and middle-class voters that now support Future Forward, augmenting the deep base of support for the Red Shirts and PT, whose own version of han is much in evidence (Elinoff Citation2012; Sopranzetti Citation2012). South Korea’s more robust industrial development under authoritarianism may have helped produce its own gravediggers, in the form of a large, militant industrial working class and a strong people’s movement. But Thailand’s successful maintenance of authoritarian rule on behalf of lazy capital may now be generating a heterogeneous group of undertakers, who will face the task of finally putting a zombie regime to rest. One must hope these actors are not bitten by the zombies.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1. For the recent history of the Constitutional Court and its political interventions see Dressel and Khemthong (Citation2019).

2. For detailed analyses of the 2019 elections, as well as for a discussion of other recent political events, see the websites New Mandala and Political Prisoners in Thailand, as well as the websites for major newspapers such as the Bangkok Post and Prachathai.

3. References to source documents for claims in the next two paragraphs can be found in Glassman (Citation2004, 50–52).

4. Unless otherwise noted, sources for data in this and the following paragraph are cited in Glassman (Citation2004, 106–119).

5. For extended discussions of these issues, see the special issues of Journal of Contemporary Asia on the Thai coups of 2006 and 2014, and especially Connors and Hewison (Citation2008); Thongchai (Citation2008); Chambers and Napisa (Citation2016); Mérieau (Citation2016); Prajak (Citation2016); and Veerayooth (Citation2016).

6. It is clear that in some ways Thai military leaders today yearn to have a communist enemy and spend considerable efforts rhetorically manufacturing one (see, for example, Bangkok Post, October 11, 2019).

References

- Amsden, A. 1989. Asia’s Next Giant: South Korea and Late Industrialization. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Anderson, B. 1977. “Withdrawal Symptoms: Social and Cultural Aspects of the October 6 Coup.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 9 (3): 13–30.

- Bell, P. 1978, “‘Cycles’ of Class Struggle in Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 8 (1): 51–79.

- Bowie, K. 1997. Rituals of National Loyalty: An Anthropology of the State and the Village Scout Movement in Thailand. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Bundy, W. 1968. “Memorandum From the Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs (Bundy) to Secretary of State Rusk, 20 August 1968.” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXVII, Mainland Southeast Asia; Regional Affairs, Document 404. Accessed October 22, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v27/d404.

- Chairat Charoensin-o-larn. 1988. Understanding Postwar Reformism in Thailand: A Reinterpretation of Rural Development. Bangkok: Editions Duang Kamol.

- Chambers, P., and Napisa Waitoolkiat. 2016. “The Resilience of Monarchised Military in Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (3): 425–444.

- Chang, D.-O. 2009. Capitalist Development in Korea: Labour, Capital, and the Myth of the Developmental State. London: Routledge.

- Chang, H.-J. 2003. Globalisation, Economic Development, and the Role of the State. London: Zed Books.

- Chibber, V. 2003. Locked in Place: State-Building and Late Industrialization in India. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- CIA. 1968. “Thailand: The Present Political Phase.” 8 October 1968, Central Intelligence Agency Intelligence Memorandum, National Security File, Thailand, Box 284, Memos, Vol. VIII, 7/68-12/68, Lyndon B. Johnson Presidential Library.

- Connors, M. 2007. Democracy and National Identity in Thailand. Copenhagen: Nordic Institute of Asian Studies.

- Connors, M. 2008. “Article of Faith: The Failure of Royal Liberalism in Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 38 (1): 143–165.

- Connors, M., and K. Hewison. 2008. “Introduction: Thailand and the ‘Good Coup’.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 38 (1): 1–10.

- Credit Suisse Research Institute. 2018. Global Wealth Databook. Credit Suisse Research Institute, October. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://www.credit-suisse.com/about-us/en/reports-research/annual-reports.html.

- Cumings, B. 2005. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. New York: Norton.

- Darling, F. 1965. Thailand and the United States. Washington, DC: Public Affairs Press.

- Doner, R. 2009. Politics of Uneven Development: Thailand’s Economic Growth in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Doucette, J. 2010. “The Terminal Crisis of ‘Participatory Government’ and the Election of Lee Myung Bak.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 40 (1): 22–43.

- Doucette, J. 2013a. “The Korean Thermidor: On Political Space and Conservative Reactions.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 38: 299–310.

- Doucette, J. 2013b. “Minjung Tactics in a Post-Minjung Era? The Survival of Self-Immolation and Traumatic Forms of Labour Protest in South Korea.” In New Forms and Expressions of Conflict in the Workplace, edited by G. Gall, 245–271. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Doucette, J., and S.-W. Koo. 2014. “Distorting Democracy: Politics by Public Security in Contemporary South Korea (Update).” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus 12,18, (1).

- Dressel, B., and Khemthong Tonsakulrungruang. 2019. “Coloured Judgements? The Work of the Thai Constitutional Court, 1998–2016.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 49 (1): 1–23.

- Elinoff, E. 2012. “Smouldering Aspirations: Burning Buildings and the Politics of Belonging in Contemporary Isan.” South East Asia Research 20 (3): 381–397.

- Flood, E. 1977. “The United States and the Military Coup in Thailand: A Background Study.” Berkeley: Indochina Resource Center.

- Glassman, J. 2004. Thailand at the Margins: Internationalization of the State and the Transformation of Labour. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Glassman, J. 2010. “‘The Provinces Elect Governments, Bangkok Overthrows Them’: Urbanity, Class, and Post-Democracy in Thailand.” Urban Studies 47 (6): 1301–1323.

- Glassman, J. 2011. “Cracking Hegemony in Thailand: Gramsci, Bourdieu, and the Dialectics of Rebellion.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 41 (1): 25–46.

- Glassman, J. 2018. Drums of War, Drums of Development: The Formation of a Pacific Ruling Class and Industrial Transformation in East and Southeast Asia, 1945–1980. Leiden: Brill.

- Glassman, J., and Y.-J. Choi. 2014. “The Chaebol and the US Military-Industrial Complex: Cold War Geo-Political Economy and South Korean Industrialization.” Environment and Planning A 46 (5): 1160–1180.

- Glassman, J., B.-G. Park, and Y.-J. Choi. 2008. “Failed Internationalism and Social Movement Decline: The Cases of South Korea and Thailand.” Critical Asian Studies 40 (3): 339–372.

- Good, P. 2000. “Paul Good.” The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Foreign Affairs Oral History Project, Interviews by Charles Stuart Kennedy, August 3. Accessed October 20, 2019. http://www.adst.org/OH%20TOCs/Good,%20Paul.toc.pdf.

- Haberkorn, T. 2018. In Plain Sight: Impunity and Human Rights in Thailand. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Hart-Landsberg, M., S. Jeong, and R. Westra. 2007. “Introduction: Marxist Perspectives on South Korea in the Global Economy.” In Marxist Perspectives on South Korea in the Global Economy, edited by M. Hart-Landsberg, S. Jeong, and R. Westra, 1–29. Aldershot: Ashgate.

- Hewison, K. 1989. Bankers and Bureaucrats: Capital and the Role of the State in Thailand. New Haven: Yale University Southeast Asia Studies.

- Hewison, K. 1997. “The Monarchy and Democratization.” In Political Change in Thailand: Democracy and Participation, edited by K. Hewison, 58–74. London: Routledge.

- Hewison, K. 2019. “Crazy Rich Thais: Thailand’s Capitalist Class, 1980–2019.” Journal of Contemporary Asia. DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1647942.

- Hewison, K. 2020. “Black Site: The Cold War and the Shape of Thailand’s Politics.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (4).

- Hewison, K., and Brown, A. 1994. “Labour and Unions in an Industrializing Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 24 (4): 483–513.

- Inter-Parliamentary Union (IPU). 1969. “Thailand.” Accessed October 30, 2019. http://archive.ipu.org/parline-e/reports/arc/THAILAND_1969_E.PDF.

- Janelli, R., with D. Yim. 1993. Making Capitalism: The Social and Cultural Construction of a South Korean Conglomerate. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Johnson Administration. 1967. “Scope Paper, Visit of the Their Majesties the King and Queen of Thailand, 20 June 1967.” National Security File, Thailand, Box 285, Visit of King Adulyadej & Queen Sirikit (I), 6/27-29/67, Lyndon Baines Johnson Presidential Library.

- Johnson, U. 1959. “Despatch From the Embassy in Thailand to the Department of State, 20 October 1959.” Foreign Relations of the United States 1958–1960, Volume XV, South and Southeast Asia, Document 534. Accessed October 22, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1958-60v15/d534.

- Johnson, U. 1971. “Letter from Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs (Johnson) to the Charge de Affaires in Thailand (Newman), 9 July 1971.” Foreign Relations of the United States 1969–1976, Volume XX, Southeast Asia, 1969–1972, Document 129. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v20/d129.

- Keyes, C. 2014. Finding their Voice: Northeastern Villagers and the Thai State. Chiang Mai: Silkworm.

- Kim, E. 1997. Big Business, Strong State: Collusion and Conflict in South Korean Development, 1960–1990. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Kim, H.-A. 2017. “President Roh Moo-Hyun’s Last Interview and the Roh Moo-Hyun Phenomenon in South Korea.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 47 (2): 273–298.

- Kissinger, H. 1971. “ Memorandum from the President’s Assistant for National Security Affairs (Kissinger) to President Nixon, 17 November 1971.” Foreign Relations of the United States 1969–1976, Volume XX, Southeast Asia, 1969–1972, Document 143. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v20/d143.

- Koo, H. 2001. Korean Workers: The Culture and Politics of Class Formation. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

- Kriangsak Teerakowitikajorn. 2018. “Thailand’s New Left-wing Political Parties: Rivals or Allies?” New Mandala, November 19. Accessed May 12, 2019. https://www.newmandala.org/thailands-new-left-wing-political-parties-rivals-or-allies/.

- Martin, G. 1968. “Memorandum from the Secretary of State’s Special Assistant for Refugee and Migration Affairs (Martin) to the Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for East Asian and Pacific Affairs (Brown), 30 July 1968.” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXVII, Mainland Southeast Asia; Regional Affairs, Document 398. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v27/d398.

- Medhi Krongkaew. 1995. “Contributions of Agriculture to Industrialization.” In Thailand’s Industrialization and Its Consequences, edited by Medhi Krongkaew, 33–65. London: Macmillan.

- Mérieau, E. 2016. “Thailand’s Deep State, Royal Power and the Constitutional Court (1997–2015).” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (3): 445–466.

- Mills, M. 1999. Thai Women in the Global Labor Force: Consuming Desires, Contested Selves. Rutgers: Rutgers University Press.

- Moon, C.-I. 2012. The Sunshine Policy: In Defense of Engagement as a Path to Peace in Korea. Seoul: Yonsei University Press.

- Muscat, R. 1994. The Fifth Tiger: A Study of Thai Development Policy. Armonk: M. E. Sharpe.

- National Security Council, US. 1965. “Memorandum Prepared for the 303 Committee, 28 September 1965.” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXVII, Mainland Southeast Asia; Regional Affairs, Document 305. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v27/d305.

- National Security Council, US 1968. “Memorandum of Conversation, 18 July 1968.” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1964–1968, Volume XXVII, Mainland Southeast Asia; Regional Affairs, Document 396. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1964-68v27/d396.

- National Security Council, US. 1969. “Memorandum Prepared for the 303 Committee, 7 February 1969.” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XX, Southeast Asia, 1969–1972, Document 3. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v20/d3.

- National Security Council, US. 1971. “Memorandum of Conversation, 18 November 1971, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976.” Volume XX, Southeast Asia, 1969–1972, Document 144. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v20/d144.

- Naya, S. 1971. “The Vietnam War and Some Aspects of Its Economic Impacts on Asian Countries.” The Developing Economies 9 (1): 31–57.

- Ockey, J. 2004. Making Democracy: Leadership, Class, Gender, and Political Participation in Thailand. Chiang Mai: Silkworm.

- OECD. 1999. Labour Force Statistics 1978–1998. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development. Accessed May 12, 2019. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/employment/labour-force-statistics-1999_lfs-1999-en-fr.

- OECD. 2019. Economic Outlook for Southeast Asia, China, and India 2019: Towards Smart Urban Transportation. Paris: Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development.

- Ogle, G. 1990. South Korea: Dissent within the Economic Miracle. London: Zed Books.

- Pasuk Phongpaichit. 2016. “Inequality, Wealth and Thailand’s Politics.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (3): 405–424.

- Pasuk Phongpaichit and C. Baker. 2000. Thailand’s Crisis. Chiang Mai: Silkworm.

- Pasuk Phongpaichit and C. Baker, eds. 2008. Thai Capital After the 1997 Crisis. Chiang Mai: Silkworm.

- Pavin Chachavalpongpun. 2014. ‘“Good Coup’ Gone Bad: Thailand’s Political Developments Since Thaksin’s Downfall.” In “Good Coup” Gone Bad: Thailand’s Political Developments Since Thaksin’s Downfall, edited by Pavin Chachavalpongpun, 3–16. Singapore: Institute for Southeast Asian Studies Press.

- Pilger, J. 2016. “The Coming War on China.” Dartmouth Films.

- Prajak Kongkirati. 2016. “Thailand’s Failed 2014 Election: The Anti-Election Movement, Violence, and Democratic Breakdown.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (3): 467–85.

- Shin, G.-W. 2006. Ethnic Nationalism in Korea: Genealogy, Politics, and Legacy. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Somchai Phatharathananunth. 2016. “Rural Transformations and Democracy in Northeast Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (3): 504–519.

- Sopranzetti, C. 2012. “Burning Red Desires: Isan Migrants and the Politics of Desire in Contemporary Thailand.” South East Asia Research 20 (3): 361–379.

- Tadem, T. 2020. “Technocrats/Philippines.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (4).

- Thak Chaloemtiarana. 2007. Thailand: The Politics of Despotic Paternalism. Ithaca: Cornell University Southeast Asia Program.

- Thareerat Laohabut. 2019. “2019 Thai General Election: A déjà vu of 1969 Thai General Election.” Prachathai English, April 28. Accessed October 30, 2019. https://prachatai.com/english/node/8031.

- Thongchai Winichakul. 2008. “Toppling Democracy.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 38 (1): 11–37.

- Törnquist, O. 2020. “The Legacies of the Indonesian Counter-Revolution: New Insights and Remaining Issues.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 50 (4). DOI: 10.1080/00472336.2019.1616105.

- Turton, A. 1978. “The Current Situation in the Thai Countryside.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 8 (1): 104–142.

- Turton, A. 1987. “Rural Social Movements: The Peasants’ Federation of Thailand.” In Production, Power, and Participation in Rural Thailand: Experiences of Poor Farmers’ Groups, edited by A. Turton, 35–43. Geneva: UN Research Institute for Social Development.

- Unger, L. 1971. “Letter from the Ambassador to Thailand (Unger) to the Under Secretary of State for Political Affairs (Johnson), 28 May 1971.” Foreign Relations of the United States, 1969–1976, Volume XX, Southeast Asia, 1969–1972, Document 120. Accessed October 30, 2019. http://history.state.gov/historicaldocuments/frus1969-76v20/d120.

- UNIDO. 1992. Thailand: Coping with the Strains of Success. Oxford: Blackwell and United Nations Industrial Development Organization.

- Veerayooth Kanchoochat. 2016. “Reign-Seeking and the Rise of the Unelected in Thailand.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (3): 486–503.

- Walker, A. 2012. Thailand’s Political Peasants: Power in the Modern Rural Economy. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Weiner, T. 2008. Legacy of Ashes: The History of the CIA. New York: Anchor Books.

- Woo, J. 1991. Race to the Swift: State and Finance in Korean Industrialization. New York: Columbia University Press.

- World Bank. n.d. Data Bank. https://databank.worldbank.org/home.aspx.