Abstract

Maintaining its hegemonic role in Singapore has been one of the defining features of the People’s Action Party (PAP) rule since the country gained independence in 1965. To quell rising frustrations resulting from its wide-reaching control, the party has overseen a series of limited liberalisations, including the 2008 introduction of legalised protests. However, in recent years the PAP has sought to reduce the influence of protests, suggesting it sees potential political challenges to its continued dominance over various aspects of Singaporean life. To examine these potential challenges, this article performs a protest event analysis and provides the first dataset of Singaporean protests since legalisation. The central argument of the article is that although protests have had limited impact on the institutional control the PAP has over the Singaporean political system, they have influenced public discourse and contributed to the expansion of politicised and contentious space in Singapore. This represents an important development in the emergence of Singaporean civil society. While this impact is currently limited, the article highlights the potential for more substantial challenges to emerge from protests in response to changing economic and political conditions.

A central issue facing the ruling People’s Action Party (PAP) has been the balance between opening limited civil society space while maintaining its wide-reaching control over various aspects of Singaporean society. Although the PAP has retained its dominant position in the country since independence, its rule has not been without challenge, with the party facing growing dissent and apathy to its leadership (see Barr Citation2014). Instead of liberalisation for the intention of democratisation, the PAP has sought to renew its dominant status through a series of “strategic liberalisations” aimed at managing societal tensions and reducing challenges to its rule (Ortmann Citation2012, 174). These liberalisations have focused on the limited opening, and acceptance, of growing civil society space and avenues for public participation. While ostensibly more open, the management of this space has been facilitated by the development of self-censorship discourses such as a “civic society” and the promotion of “Out-of-Bounds (OB) Markers.” Singaporeans are expected to know the boundaries of acceptable discourse and action, with the limits defined by the PAP (see Lee Citation2005; Lyons and Gomez Citation2005). This “managed liberalisation” has defined state–society relations in recent decades, as the PAP seeks to control the rules of participation in civil society and reduce any competitive challenges to its power emerging from within it (Abdullah Citation2020, 1127).

One such liberalisation was the introduction of legalised protest. Building on the introduction of a “Speakers’ Corner” in 2000, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong announced at the 2008 National Day celebration that Singaporeans would be able to stage protests for the first time without the need for a police permit. The right to protest was still limited, for example an online registration with the Park’s Authority was required, while there were restrictions on protests focused on race and religion. Foreign nationals were also not able to participate – though could observe – and all protests must take place in the Speakers’ Corner area of Hong Lim Park in the Downtown Core district of the city. While still heavily restricted, the introduction of protests brought a new civil society space, and in announcing the reforms, Lee Hsien Loong claimed they would “widen the space for expression and participation. We encourage citizens to engage in debate, to participate in building our shared future and we will progressively open our system even more … we will continue to feel our way forward” (Prime Minister’s Office Citation2008).

However, less than a year after the introduction of legal protests, the government installed CCTV in Speakers’ Corner (Today, July 25, 2009). And, in 2017 amendments to the Public Order Act – the law which governs public gatherings and demonstrations – saw the period of notice required for the National Park Board, the agency responsible for managing Hong Lim Park, extended to 28 days. Police would now need to be informed of the expected turnout, and foreign nationals were no longer able to observe during gatherings. Ministers were also given wide-reaching power to cancel or postpone events (Ministry of Home Affairs Citation2017).

This volte-face from encouraging protests as a form of expression and participation, to the amendment of legislation which makes carrying them out more difficult raises the question why, after opening space for protests, is the PAP now seeking to reduce it? If these actions reflect the PAP’s continued aims of controlling and reducing the emergence of competitive political actors, what potential competitive challenges has the introduction of protests brought into Singaporean civil society?

Existing research on Singaporean demonstrations has explored specific protest events (see Gwynne Citation2013; Tan Citation2015) or looked at protests as part of a wider analysis of civil society (Ortmann Citation2015; Citation2019). As a result, a dedicated overview of protests has been overlooked, and the dynamics and wider political challenges emerging from them are largely unknown. As such this article presents the first extensive study of protests in Singapore since their legalisation, offering an examination of the features of protests and the potential competitive challenges they have introduced into society.

To achieve this, the article employs a protest event analysis (PEA) to compile the first dataset of Singaporean protests. It examines the forms and frequency of protests – including those staged illegally outside of Hong Lim Park – such as protest issues, targets, and if they have achieved their policy aims. This approach allows for an overview of the features of protests, while also examining whether the managed liberalisation of their legalisation has introduced a competitive force into civil society; one capable of challenging the PAP as the only major political actor within Singapore.

The article’s central argument highlights how demonstrations have been utilised by Singaporeans to express themselves over a wide range of issues. More than anything however, they have used this right to seek engagement and interaction with the government. As a result, the use of protests represents a contentious and politicised space within Singapore, an important development in an increasingly assertive civil society. Although protests have had limited impact in either generating or challenging significant areas of policy, and with little evidence of attempts to normalise protests outside of Hong Lim Park, they have produced an agenda-setting power. This has allowed protesters to shape and influence public debate. How the PAP manages this politicised space and the challenges emerging from it will have important implications for the PAP’s continued attempts at managed liberalisation and state–society relations.

This article proceeds as follows. The next section examines scholarship on the PAP’s attempts to introduce limited reforms while maintaining hegemonic dominance, including the limited research which has explored protests as part of this wider discussion. Next the article discusses PEA as a methodological approach, before addressing data collection and coding. From here the article presents the central findings, split into five sub-sections highlighting various aspects of protests in Singapore, before moving to a discussion on the findings and the limited competitiveness emerging from this politicised space. The article concludes with a discussion on how protests could bring future challenges to the PAP and avenues for future research.

Calibrated Civil Society, Protests, and Challenging the PAP

The defining feature of Singaporean politics is the hegemonic position the ruling PAP has. Although ostensibly a multi-party democracy with free and regular elections, the PAP maintains control over the institutions of the state. This control has resulted in restricting the growth of political opposition, an independent media, and the emergence of an independent civil society (see Gomez Citation2006; Lee Citation2010; Weiss Citation2014).

Yet in contrast to more overtly authoritarian regimes, the PAP still seeks legitimacy through elections. To maintain its position as the primary political actor, it has had to respond to challenges to its position, reflected in growing support for opposition politicians and pressure from the middle-class for greater liberalisations (see Rodan Citation1993, 78; Mutalib Citation2000, 334). In response, the PAP initiated a series of institutional and societal reforms, such as the opening and tolerance of civil society space. As a result, in recent decades Singapore has seen the emergence of groups and activities associated with the concept of civil society, including tolerating the initial growth of online-based alternative and critical media (George Citation2012, 758–760), civil society organisations (CSOs) (Chua Citation1994, 663–664), and the introduction of a “Speakers’ Corner” where Singaporeans can express dissent (Thio Citation2003, 517–522).

However, this opening of civil society space is not liberalisation for the intention of democratisation, but rather to reduce any tensions emerging which challenge PAP dominance. Indeed, the PAP have explicitly sought to control the terms of participation within this space, reflected in the promotion of a “civic” society, one defined by being apolitical and centred on “responsibilities” rather than “rights” (Chua Citation2000, 76–77). An example is in the development of the self-censorship discourse known as “OB Markers.” Ostensibly these are meant to provide Singaporeans space for societal participation, though only within the boundaries of acceptable behaviour defined by the PAP (Lee Citation2002, 108).

As George (Citation2007, 133) notes, there have been no moves to repeal Singapore’s most repressive laws, but rather an approach he defines as “calibrated coercion,” with “ordinary” citizens offered more space for participation, but with authoritarian measures in place to target “producers and organizers of dissent” which may challenge its control.

It is this strategic or calibrated liberalisation – the opening of limited and controlled civil society space – which has defined Singaporean politics in recent decades. As Barr (Citation2010, 335) notes: “Singapore’s ruling elite runs a finely calibrated system of social and political control based on a mixture of monitoring and repression by the state, and self-monitoring and self-restraint by all elements of civil society.” Rather than being overtly authoritarian, the PAP’s approach is not always indiscriminate, instead often highly measured and sophisticated. As such, the management of this societal space is complex and multi-faceted, but the aim is consistent; to maintain the PAP’s continued primacy and ensuring a truly competitive independent civil society does not emerge. With this opening of civil society space defined by the PAP’s desire to reduce any challenges, the limited openings have been dismissed as “gesture” politics rather than anything substantial (Lee Citation2005, 135).

Despite the continued heavy restrictions, scholars have noted important shifts in state–society relations and a growing competitiveness within civil society. As two of the most prominent civil society spaces, much of this scholarship has focused on the actions of CSOs and online-based alternative and social media which have “stepped up the articulation of emergent and simmering demands … with an increasing range of critical perspectives in circulation” (Weiss Citation2014, 873). Still limited, CSOs have had success in low-level policy reform such as improving conditions for migrant workers (Ang and Neo Citation2017, 124–125). As Barr (Citation2016, 14) highlights, critical voices in civil society, alongside the PAP’s own political failures, has facilitated a shift in perceptions of the PAP from an “exceptional” party to an “ordinary” one. Although these are not fundamental challenges to the PAP, they reflect a shift in the “hegemonic discourse” capacity of the ruling party. It has had to respond to public demand rather than simply ignoring it, with civil society actors increasingly assertive in pushing their aims (see Ortmann Citation2019).

Importantly, this literature does not suggest these developments amount to imminent democratisation. Indeed, the increasing contestation may even slow any “further transformations” (Ortmann Citation2011, 154). The PAP continues to demonstrate its “calibrated” approach. For example, in 2019 the PAP introduced the Protection from Online Falsehoods and Manipulation Act (POFMA) to target online and alternative media (see Teo Citation2021). As well, it has continued the vilification of some civil society actors (Low Citation2020, 58). Rather, the literature highlights the emerging spaces of contention within civil society, and the shifting dynamics of state–society relations which the PAP must respond to.

As a further strategic liberalisation, the introduction of protests represents an important space within this emerging civil society, though research into the dynamics of this space is limited. While protests have been examined as part of a wider analysis of civil society, the focus is largely on individual high-profile events (see Kaur and Yeo Citation2017; Ortmann Citation2019). For example, both Gwynne (Citation2013) and Phillips (Citation2014) highlight the domestication of specific international protests into a Singaporean context defined by “OB Markers,” while Goh and Pang (Citation2016) examine the emotional framing organisers and supporters used to generate support online for a large-scale anti-immigration protest. One comparative analysis examines the PAP’s responses to different protests, which is argued to demonstrate its “spectrum of control” and reflective of the “calibrated liberalisation” which defines the management of public space in Singapore (Prakash and Abdullah Citation2022, 384). However, the analysis is limited to just three high-profile demonstrations.

This existing research does highlight important features of protests and how their introduction fits into the dynamics of state–society relations. Yet protests represent a unique space within civil society, not only in the physical sense where they are restricted to Hong Lim Park, but also as a space for societal interaction and expression. By focusing on high-profile events, the wider features of protests remain unknown. With the PAP seeking to reduce the influence of demonstrations through administrative changes, examining these dynamics provides understanding into the wider contentious and competitive challenges the PAP seek to contain. For an apolitical citizenry (see Lawson Citation2001), examining Singaporeans’ use of protest provides important insight into the issues which concern and motivate them, and the use of protests as a space of contention. Therefore, this article provides a contribution to understanding the use of a civil society space in the form of protests, but also into the wider dynamics of state–society relations and the control of spaces of contention in Singaporean civil society.

Protest Event Analysis

PEA has emerged in recent decades as one of the central methods in the study of protests and social movements (Oliver, Cadena-Roa, and Strawn Citation2003, 214). As a form of content analysis, PEA systematically collects a range of publicly reported protest event data, usually taken from newspaper reports, as is the case for this article, to “assess the amount and features of protest” (Hutter Citation2014, 336). As Tilly notes (1995, 70), the approach has the benefit of requiring “no a priori decisions as to which groups, places, issues, and forms of actions predominately feature.” The methodological advantage of this is that “PEA provides a solid ground in an area that is still often marked by more or less informed speculation” (Koopmans and Rucht Citation2002, 252). In the case of Singapore, where the wider dynamics of protest are unknown, this proves advantageous. As a result, researchers have utilised the approach to undertake large-scale, cross-national and longitudinal studies of various protest groups, movements, and actors (Hutter Citation2014, 336). However, the approach also allows for a focus on country-specific movements and issues, or in some cases the dynamics within singular protest events (see McPhail and Schweingruber Citation1999).

The broad utilisation of PEA as a method has inevitably introduced conceptual challenges in defining the scope and nature of analysis. This includes the definition of protest itself, which is often referred to in collective terms, with demonstrations highlighted as “a collective, public action by a non-governmental actor who expresses criticism or dissent and articulates a societal or political demand” (Rucht and Neidhardt Citation1999, 68). However, in the context of Singapore, the Public Order Act defines protests as any “cause-related activity” (SSO Citation2009). So, for example, an individual holding up a sign in public outside of the Hong Lim Park area can result in arrest and attract media attention. Protest acts that might be treated as trivial in other localities become significant in the Singaporean context. As a city-state where civil society activity is limited, even minor protests remain a newsworthy event. In comparison to larger countries where the focus is often limited to specific issues, compiling a complete dataset is more achievable. Rather than exploring specific protests or issues, the data covers all protests reported within the newspaper sources between 2008 and 2021, providing a greater scope in examining the dynamics of Singaporean protests.

To clarify the scope of the PEA, it is important to address a few points. The first being the distinction between protests as a physical event, and other types of activism that make up wider social movements. As Koopmans and Neidhart (Citation1999, 9) explain: “All social movements protest, but not all protests are social movements.” There are protests within the dataset which form part of wider campaign movements, for example LGBT activism, though these are beyond the scope of the research. Although the timeframe of the analysis begins with the 2008 legalisation of protests in Hong Lim Park, the dataset also includes any illegal demonstrations – those taking place outside of Hong Lim Park without a license. One exception to this is petitions, with only those being signed directly in Hong Lim Park included. With many petitions taking place online, it was deemed impracticable to include these in the dataset.

Further, only the main issues and targets of the protest events described within the news articles are recorded. The nature of protests means the issues and targets are often multi-faceted, featuring numerous actors with potentially different grievances, concerns, and targets. However, newspaper reports often focus on the “headline” issues, and so other potential issues and causes promoted within them are left out. Therefore, while the PEA collates the central aims expressed within the reports, this is not to suggest that protests did not articulate other aims or targets within them.

It should also be noted the PEA only includes events from non-political actors, and so excludes protests or demonstrations held by either the PAP, or opposition parties and politicians. While the PAP does not treat opposition parties as political equals, and the calibrated coercive tools used on civil society actors are also utilised on opposition politicians, political parties are allowed to hold political rallies during election periods, something not open to the public. As the PAP have explicitly sought to demarcate the political sphere from civil society through the promotion of a “civic” non-political space, it was decided to focus exclusively on non-political actors.

While the scope of this research has inherent limitations, developments within PEA approaches have seen a shift away from focusing on aggregates of protest events as the main unit of analysis (Hutter Citation2014, 339). There has been a widening of the analysis to include contentious discursive claims amongst a variety of institutional and civil society actors, alongside the protest events themselves (see Koopmans and Statham Citation1999). While not the aim of the present article, such an approach would be beneficial, helping to link protests with wider contentious acts and discourses amongst civil society actors, for example those carried out in online spaces. Similarly, while resource mobilisation is a crucial part of the development of social movements, as the focus here was specifically on physical protests, it was not included within the analysis. However, understanding how protests and social movements generate resources, and indeed how protests themselves help build wider social movements would undoubtedly provide greater context of how protests and social movements emerge in Singapore.

To reiterate, the methodological approach used for this research does not allow for an examination of physical protests and their link to wider political participation and contention. However, it does provide an important analysis on protests themselves, and offers avenues for future research to examine wider activism and contentious acts in Singapore.

The data for this study was sourced from two domestic news outlets, The Straits Times, and The Online Citizen. These were chosen as they reflect different ideological positions within Singaporean media to reduce potential selection bias, with The Straits Times being the most popular online and print newspaper (Similar Web Citation2022), while The Online Citizen was one of the longest running and most prominent alternative media sources in the country before its initial closure in September 2021.Footnote1 Within Singapore, alternative media is used to describe online-based independent media and blogs which are often more critical of the government than state-owned organisations, though they are still expected to report within the confines of “OB Markers” in the same manner as traditional media (see George Citation2015). As such, the sources used provide a balance between traditional and alternative media, and if both sources reported on the same event and there was a discrepancy in reported attendance, an average of the two numbers was used.

The data was collected using a keyword search with terms relevant to protests in Singapore, Protest, Speakers Corner, Hong Lim Park, Demonstration, and Public Order Act. Accessing articles for The Straits Times was achieved using archiving system Factiva and Google Advanced Search, while for The Online Citizen only the latter was available. The date range for the search was from August 1, 2008 when protests were legalised until September 1, 2021. While protests carried out after this date were excluded, any significant policy changes in relation to demonstrations within the dataset were included up until September 1, 2022.

As discussed, the PAP’s articulation of a civic society is fundamentally non-political, and so the variables focusing on protest issues, targets, and outcomes in the form of policy change were chosen to ascertain whether they represent a politicised use of civil society. lists the full variables used in the data collection process.

Table 1. Variables used for protest event analysis

Features of Singaporean Protests: PEA

This section presents the results of the PEA. The results are split into five sub-sections: the frequency and forms of protest; the issues protested over; who the protests target; policy changes resulting from legal protests; and illegal protests.

Frequency and Forms of Protests

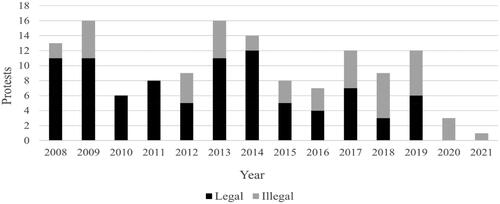

The PEA reveals the total number of protest events recorded within the dataset, split between legal and illegal protests. This can be seen in .

shows 134 recorded protest events between September 2008 and September 2021. Of these, 89 took place within Hong Lim Park, with a further 45 taking place in other areas of the city-state illegally. This means 66% of recorded protests took place legally. In 2008 there were high levels of protest, accounting for nearly 10% of the dataset despite demonstrations only being legalised from September that year. This prominent use of protests continued in 2009 with a total of 16 recorded events before dropping in 2010; however eight of the 11 demonstrations in 2009 took place before installation of CCTV in July 2009. It is important to note that Hong Lim Park was closed during the 2011 and 2015 election campaign periods, while the 2015 death of former Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew also saw the park closed for seven days as part of a period of national mourning (The Straits Times, March 31, 2015). Overall, 2009 and 2013 are the years with the highest levels of both legal and illegal protests, while 2014 saw the highest number of events within Hong Lim Park.

The years with the fewest recorded protests were 2020 and 2021, with a total of three and one event respectively, all of which were illegal. This period covers the introduction of restrictions due to the COVID-19 pandemic, with demonstrations halted as part of a wider policy restricting public gatherings. However, none of the illegal protests held in this period were related to pandemic issues, whether in relation to the implementation of restrictions themselves, or concerns over vaccines and vaccination.

As shows, legal protests have followed a standardised pattern. Rallies were the most used protest type, with 65 reported, while 60% of all protests were recorded as having fewer than 500 people in attendance. All protests were also reported as taking place over one day, while there were no recorded acts of violence from the protestors. To an extent this standardisation reflects the physical limitations of having to hold demonstrations in the relatively small space of Hong Lim Park, and so avenues for more novel or radical forms of protest – ones that might attract more public attention – are limited.

Table 2. Frequency and features of protests in Hong Lim Park

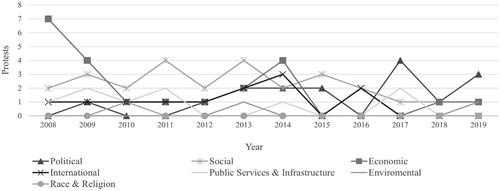

Singapore Protests by Issue

Outside of the frequency and forms of legal protests, displays the dominant issue categories of demonstrations. Singaporeans have used the right to protest to highlight and engage with a variety of issues, with demonstrations focusing on social issues being the most frequent, followed by economic, political, international issue protests, and demonstrations concerning public services and infrastructure. While environmental protests have become common occurrences in many countries around the world, it was only the sixth highest category for protests in Singapore, with two legal protests reported to have taken place. Although protests related to race and religion are banned, there was one recorded event in the dataset. This took place in 2010 over reports the government was set to reduce the importance given to “Mother Tongues” in education examinations. It saw a primarily ethnic Chinese community signing a petition in Hong Lim Park to challenge this potential change, one the government denied was ever intended (The Straits Times, May 10, 2010).

Table 3. Hong Lim Park protests by issue category

Despite the claim that Singaporeans are largely apolitical, the findings offer an important insight into the diversity of issues they have demonstrated over. These range from events aimed at reducing the consumption of shark fin soup (The Online Citizen, April 10, 2009) to demonstrating over the cost of public transport (The Online Citizen, January 26, 2014). There were also more overtly political demonstrations, such as 200 people calling for the resignation of Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (The Online Citizen, July 6, 2014).

The diversity of causes is not limited to Singapore-specific issues, and in a few cases drew influence from global campaigns. These include Singaporean incarnations of transnational movements, such as the domesticated version of the “SlutWalk” movement, which attracted around 650 people (The Straits Times, December 5, 2011; see also Gwynne Citation2013). Likewise, there was Pink Dot, a Singaporean version of an LGBT “pride” event. While similar events globally are often carried out as marches, the limitations of Singaporean law saw them confined to Hong Lim Park. In the case of Pink Dot, the more overt celebration of sexuality seen in other places is also largely removed, instead the demonstrations are promoted as family events centred on themes of love and acceptance (see Phillips Citation2014). This adoption of transnational campaigns has provided Singaporeans the opportunity to highlight issues within the country itself and places these domestic issues into a wider global conversation and movement.

Overall, the findings provide an important insight into the diversity of protest issues within the dataset, with highlighting how the prevalence of protest issue categories changed throughout the period under analysis. While social issue protests have remained relatively consistent throughout the period, economic and political issue protests peaked in 2008 and 2017 respectively. In the case of economic protests, 33% of events took place in 2008 and 2009 at the height of the Global Financial Crisis, while for political issue events the most prominent year was 2017, which as will be discussed in the next section, saw two highly contentious issues related to Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and President Halimah Yacob. While 2017 only saw four political issue protests, the most contentious issue category, the rise in reaction to political scandals, demonstrates how protests can emerge in response to specific events. Indeed, 50% of all political issue protests have occurred since 2017, which points to an increasing, though still limited, use of Hong Lim Park to stage explicitly political demonstrations. Overall, the number of protests remains low, though the findings show they rise in response to contextual conditions. This has important implications for the use of protests which will be discussed further in the final section.

Singaporean Protests by Targets

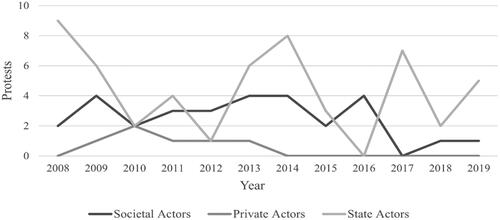

Away from the dominant issues categories expressed in Singaporean protests, displays the central targets of Singaporean demonstrations, with six protests aimed at private actors, 30 protests aimed at raising awareness amongst societal actors, and 53 protests targeting the government. As such, nearly 60% of legal protests seek some form of action or response from government.

Table 4. Hong Lim Park protests by targets

Protests targeting private actors

Protests targeting private actors, while limited in number, cover a range of issues from financial losses to animal rights. These include: a 2010 protest which saw 40 people in Hong Lim Park seek financial compensation following a failed private investment scheme (The Straits Times, June 13, 2010); and a protest in 2010 which saw 125 protestors challenge the decision to not screen the 2010 FIFA World Cup on public television (The Online Citizen, June 9, 2010). The largest demonstration aimed at a private actor attracted 200 protesters calling for the release of two dolphins held in a Singaporean aquarium (The Straits Times, August 29, 2011).

Protests targeting societal actors

Demonstrations aimed at societal actors – those which seek to express solidarity or raise public awareness on issues – mainly centre on social and international causes. The latter includes protests in response to international events such as a candlelight vigil held to express solidarity for the victims of the 2016 LGBT nightclub shooting in Orlando, Florida (The Online Citizen, June 14, 2016). They also include several protests related to regional events such as government oppression in Myanmar (The Online Citizen, June 1, 2009) and democratic movements in Malaysia and Hong Kong (The Online Citizen, July 9, 2011; September 30, 2014). The most attended internationally focused protest took place in 2014, when it was one of two demonstrations related to violent outbreaks in Gaza, Palestine. The larger of these attracted over 1,000 people (The Online Citizen, July 18, 2014; August 19, 2014). These protests differ from the Singaporean incarnations of international movements discussed previously as the intention behind them is to express solidarity in response to global events, rather than highlight Singaporean-specific issues. However, they both provide evidence of how protests have been used to engage in civil society not just in Singapore, but also globally.

For protests aimed at raising awareness over Singaporean issues, the first legal demonstration took place in September 2008 and focused on highlighting the treatment of domestic workers, with 20 people taking part (The Straits Times, September 2, 2008). This protest largely set the framework for demonstrations related to social issues. Rather than explicit demands aimed at specific actors, demonstrators seek to promote specific issues to the wider public. Similar protests include a rally highlighting discrimination against the disadvantaged and disabled (The Online Citizen, June 1, 2009). This non-confrontational approach has allowed contentious issues to be heard, with the most prominent being the LGBT Pink Dot demonstrations. As consensual sex between men remained illegal in the country at the time of the first event, organisers sought to downplay the political nature of the demonstration, explicitly denying the event should be seen as a protest (Pink Dot Citation2011). This more general approach allowed the event to grow into the most successful protest to have taken place in Singapore since their legalisation, growing from 1,000 people in 2009 to 28,000 in 2015 (The Straits Times, May 17, 2009; June 13, 2015). In comparison, the largest legal non-Pink Dot protest attracted 4,500 protestors.

Protests targeting government actors

This non-confrontational approach of using protests to raise awareness of social issues reflects the discussion earlier in the article of the PAP’s desire for a civic society, rather than a politicised civil society. Yet with 60% of all legal protests targeting the government, the findings demonstrate the use of protests for political engagement. Indeed, the 2019 Pink Dot protest became more overtly political, directly calling for the repeal of Section 377A of the Penal Code, the law which forbade same-sex relations between men (The Straits Times, June 30, 2019). This represents a significant finding as it demonstrates an explicitly political space within civil society, and for a country where such avenues are rare, a new channel for political participation. Singaporeans have used this avenue to engage with the government across a range of issues, from cost-of-living concerns related to water prices (The Straits Times, March 12, 2017), to repeated calls for the repeal of the death penalty (The Online Citizen, January 12, 2010; October 10, 2011). The wide range of protests targeting the government also includes a demonstration in response to the introduction of “fake news” legislation (The Online Citizen, April 29, 2019).

Three of the most prominent demonstrations targeting the government all had multiple iterations. The first protest to target the government was in relation to financial and saving losses at the state-backed DBS Bank Limited during the Global Financial Crisis (The Online Citizen, November 12, 2008). This protest attracted 750 people in Hong Lim Park seeking compensation. The protest was not only the first to call for government action, but also the first to have multiple events, though by the seventh “DBS” demonstration, attendance had dwindled to just 40 people (The Online Citizen, December 28, 2008). This is similar to a series of protests related to the Central Provident Fund (CPF), with activists calling for a reduction in the mandatory pension and savings scheme. The first event in June 2014 attracted 2,000 people, making it one of the largest legal protests to have taken place (The Online Citizen, June 8, 2014). However, like the demonstrations related to financial losses at DBS Bank Limited, subsequent events saw dwindling numbers, attracting 1,000, 900, and 500 participants respectively (The Straits Times, July 13, 2014; The Online Citizen, August 27, 2014).

The most successful of the multiple-iteration protests targeting the government emerged in response to the launch of the Population White Paper, which suggested the population could increase to 6.9 million by 2030 (Strategy Group Singapore Citation2013). The February 2013 anti-immigration protest saw 4,500 people in Hong Lim Park, the largest legal protest outside of a Pink Dot event (The Online Citizen, February 17, 2013). The protest’s success in generating a large turnout attracted widespread attention, with international media commenting on the rarity of an anti-government protest on this scale (BBC News, February 16, 2013; CNN, February 16, 2013). A subsequent event in May 2013 also attracted a significant crowd of 3,500 (The Straits Times, May 2, 2013) – the second largest non-Pink Dot protest – though the third anti-immigration protest of 2013 saw only 350 in attendance (The Online Citizen, October 5, 2013).

While these protests were calling for a response from the government, they focused on matters of day-to-day policy, rather than attacks on the nature of the government itself. One protest which straddles this distinction was the June 2013 “#FreeMyInternet” demonstration. The event was in response to an announcement from the Media Development Authority that news websites with a readership of 50,000 unique individual visitors would require a license and must comply with demands to remove content if found in breach of standards. While the focus of the protest was on the introduction of the regulation, it also served to highlight the more draconian aspects of PAP rule by framing the license as an attack on freedom of expression and media censorship. The event was organised by a collection of bloggers, including The Online Citizen, and attracted a crowd of 2,250, the third largest government-targeting protest in the dataset (The Straits Times, June 2, 2013).

Protests seeking to directly challenge various aspects of the authoritarian nature of the PAP are overall rare, with just 16 protests out of the 53 calling for government action consisting of more radical demands. These include demonstrations against the jailing of political activists (The Online Citizen, August 19, 2014; November 14, 2016), and calls for democratic reform and respect for human rights (The Online Citizen, January 6, 2011; December 11, 2017). The two most significant political issue protests aimed at the authoritarian nature of the PAP both occurred in 2017 and are the only overtly critical political protests to attract more than 500 people. The largest of these was in response to the appointment of Halimah Yacob as president, a position normally elected but this time chosen by the PAP (see Rodan Citation2017). The initial plan for a protest was refused on the grounds it touched on the topics of race and religion, with President Halimah Yacob being the first ethnically Malay individual to hold the position. However, activists instead staged a “silent sit-in” in Hong Lim Park, with 1,500 reported as attending (The Straits Times, September 16, 2017).

The second significant protest in 2017 emerged in response to the “Oxley Road scandal” which saw Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong accused of altering the will of his father and former Prime Minister, Lee Kuan Yew (Vadaketh Citation2017). It saw around 500 demonstrating in Hong Lim Park and calling for the resignation of Lee Hsien Loong (The Online Citizen, July 14, 2017). Although these demonstrations did not match the number of attendees seen in more policy-orientated protests calling for government action, they remain significant as the two largest gatherings in the history of modern Singapore directly attacking PAP politicians.

Protest Targets over Time

highlights how protest targets changed throughout the duration under analysis. With the majority of protests targeting state actors, this is reflected in protest targets over time. State actors were the most prominent target every year in the dataset except for 2016, when the prominence of international issue demonstrations saw protests aimed at raising awareness amongst societal actors. The highest years for state-targeted protests were in 2008 and 2014, though both were in relation to economic issues – the “DBS” and “CPF” series of protests – rather than explicitly political ones.

Protests and Policy Changes

Although it would be expected that protests calling for radical demands such as the resignation of senior PAP politicians or wider aspects of democratic reform would largely be ignored by the government, as highlights, so too have more policy-orientated protests.

Table 5. Government responses to protests in Hong Lim Park

Of the 53 protests in Hong Lim Park calling for government action, only two were recorded as resulting in a policy change. The first was the initial anti-immigration protest, the most attended event outside of Pink Dot protests. A week after the first protest, the government announced changes to its immigration policy, including a cut in the quota for workers in the service sector and an increase in the levies paid for foreign workers (Ministry of Manpower Citation2013). It is important to highlight however that the Population White Paper was ostensibly part of a consultative process, and so there was no change in legislation resulting from the anti-immigration demonstrations. Reducing migrant labour in certain sectors has also been linked to attempts by the PAP to increase productivity (Pang and Lim Citation2016, 152–154). Yet as one of two recorded protests with a notable, if limited, policy shift following a demonstration, it stands as a significant example of protests influencing the political process.

More significant was the repeal of Section 377A. The announcement of the repeal came with changes to the Constitution which meant only legislators, and not judges, could define legal marriage (Prime Minister’s Office Citation2022). This effectively made same-sex marriage harder to achieve. While this presents a challenge in obtaining equal rights for the LGBT community, Pink Dot is the only recorded protest in the dataset which has seen its key demand for a policy change achieved.

Outside of these limited policy changes, protests have largely been ignored or dismissed by the PAP outside a few exceptions. The SG Climate Rally or “Green Dot” protest was attended by PAP politicians who subsequently highlighted the importance of addressing climate change (The Straits Times, October 19, 2019). The “Mother Tongue” petition also saw the PAP deny any intentions of changing the weighting of language exams – Mandarin-Chinese, Malay, and Tamil – as part of the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) (The Straits Times, May 10, 2010). These represent institutional engagement, but little in the way of substantial policy change. It demonstrates the challenge for activists in using protests to push for policy concessions when the chance of extracting change remains limited, particularly on overtly political issues. Both the “DBS” and “CPF” protests effectively ran out of momentum, though the latter ended after organisers were questioned by police for leaving the designated space in Hong Lim Park (The Straits Times, October 10, 2014). However, the dwindling numbers on each iteration prior to this highlight the challenges at sustaining protest movements. There is often little evidence or encouragement they will result in a positive policy change from the perspective of activists.

Illegal Protests

While most protests since 2008 have taken place in Hong Lim Park, a substantial number have taken place outside of it, without a license, and therefore illegally. As highlights, there have been 45 illegal protests during this period, with international issues being the most dominant, while economic concerns were the fourth most protested issue outside of Hong Lim Park. Many protests in these categories were reported as being carried out by those excluded from the physical space of Hong Lim Park, particularly by migrant workers and foreign nationals.

Table 6. Illegal protests by issue category

These international issue protests tended to involve smaller groups, such as the five South Korean nationals detained for demonstrating outside the St Regis hotel in the Tanglin area of the city-state during the 2018 USA–North Korea Summit (The Online Citizen, June 12, 2018). Another example involved five Taiwanese nationals questioned following a similar protest outside of a hotel during the China–Taiwan summit in 2015 (The Straits Times, November 7, 2015). However, a few large-scale demonstrations emerged in response to political events in Malaysia, including a reported gathering of around 100 people in May 2013 in the Merlion Park area of the city following the Malaysian election. A subsequent protest in the same location a few days later saw 21 Malaysian nationals arrested (The Straits Times, May 11, 2013). While these demonstrations all ended in arrests, a similar unauthorised protest did not receive the same response. The protest saw Reuters journalists holding signs outside of their office building in response to the imprisonment of a colleague in Myanmar (The Online Citizen, September 7, 2018).

Protests that were reported as being carried out by migrant workers centred on issues around pay disputes and working conditions, often taking place at worksites or outside of the Ministry of Manpower, the government department which oversees their employment. These include the commandeering of a crane by two Chinese workers on a building site (The Straits Times, December 7, 2012), and a group of around 100 workers sitting on the road outside of the Ministry of Manpower following a pay dispute (The Online Citizen, February 27, 2009). Whilst many of these protests tend to be small, two events were particularly significant, with the first seeing a reported 170 migrant workers stage the first industrial action to take place in the city-state for 25 years (The Straits Times, November 28, 2012). The second was a riot in the Little India area of the city following a worker being hit by a bus, with 300 migrant workers reported as being involved (The Straits Times, December 9, 2013).

Despite these events reflecting frustrations on the part of migrant workers, there were no major protests, either legally or illegally, aimed at specifically highlighting these issues found in the dataset. It should be noted however, that while there were no major protests related to migrant rights, civil society organisations have been particularly active in this area. Indeed, both HOME and Transient Workers Count Too (TWC2) have been prominent in advocating for better conditions for workers’ rights, and while this work is broader than simply a response to the demonstrations carried out by migrant workers, they emerged during a similar time. Although there were no substantial reforms, these groups were successful in generating minor changes to the conditions of migrant workers (see Ang and Neo Citation2017).

That many illegal protests were carried out by foreign nationals highlights two important findings. The first demonstrates the use of protests by those excluded from the right to do so in Hong Lim Park. The second highlights the reluctance many Singaporeans have regarding protesting outside of the park in large numbers. However, a notable exception took place in 2014 in response to an announcement by the National Library Board that they would be withdrawing two children’s books which highlighted same-sex relations, deeming them “anti-family.” In response, around 400 Singaporeans staged a “read-in” of the withdrawn books at the National Library Building (The Straits Times, July 13, 2014). This novel form of protest resulted in the two books being returned to the library, though this time in the adult section (The Straits Times, July 18, 2014). The read-in was the largest single demonstration outside of Hong Lim Park in the dataset, with other illegal demonstrations being significantly smaller.

Although political and social protests were the second and third largest illegal demonstration categories, these largely involved small groups. These protests include a 2021 demonstration where five activists held signs outside of the Ministry of Education in response to a Reddit post claiming a transgender student had been denied hormone blocking treatment – something denied by the Ministry (The Straits Times, January 21, 2021). Protesters holding signs or other objects has been a recurring repertoire used by activists in illegal demonstrations, such as in 2020 when two individuals held up signs highlighting environmental issues (The Straits Times, April 1, 2020). Two high-profile incidents involve well-known activists Seelan Palay and Jolovan Wham. The former was arrested after holding a silent performance in a procession from Hong Lim Park to parliament (The Straits Times, May 18, 2018), and the latter arrested after holding up a smiley face sign (The Straits Times, November 23, 2020). While these two protests were inherently political and aimed to highlight the restrictive nature of protests and civil society, they did not explicitly mention the authoritarianism of the PAP, rather highlighting it through the reaction to them.

One demonstration which did take a more direct approach involved seven activists holding up signs on the MRT public transport system, aimed at drawing attention to historic government oppression (The Straits Times, June 6, 2017). However, this remains a rare example, with a clear reluctance from activists to stage large scale, or more politically direct, illegal demonstrations, particularly those that challenge the institutional arrangements in Singapore. This is evidenced by the failed attempt to launch a Singaporean incarnation of the international “Occupy” movement. The protest was heavily promoted on social media and set to take place in the Raffles City area, however only four individuals showed up and all were subsequently arrested (The Online Citizen, October 19, 2011).

While the protests discussed above emerged in response to specific events or were aimed at changing aspects of the status quo, by far the most prominent illegal demonstration to take place sought to maintain it. The “Wear White” campaign saw religious groups encourage their followers to wear white clothing on the weekend of Pink Dot to oppose the legalisation of same-sex relations. The events, which took place in 2014 and 2015, were reported to have around 6,400 people taking part in 2014, increasing to 15,000 the following year (The Straits Times, June 20, 2014; June 12, 2015). This makes the protest the second largest event outside of Pink Dot, and the largest illegal demonstration to take place. As participation simply involved wearing white clothing while attending religious services and other activities, the protest itself was decentralised and one of the more innocuous protest forms found within the dataset, yet it still met the legal definition of a “causal-related activity.” However, in this instance, the PAP were reluctant to act, with ministers instead highlighting the need for balance and respect for each other’s values (The Straits Times, June 21, 2014). This demonstrates the arbitrary nature of what is and what is not deemed a protest.

Competitive Challenges and Protests

The findings of the PEA have provided an important insight into the nature of protests, highlighting how Singaporeans have utilised the right to protest to express themselves over a range of issues. It demonstrates the diversity of interests within civil society. While the PEA has provided an important overview of the dynamics of protest, the following discussion highlights the emerging competitiveness which protests have helped facilitate.

From an institutional perspective, which is to say direct engagement and influence on the political process, the impact is largely limited, though there have been important developments. These are notably the two policy changes linked to legal high-profile demonstrations: the anti-immigration protests and Pink Dot. It should be said that policy and legislative changes can be a long process, and so the ability of protests to directly influence this may not be readily apparent. However, in these two examples it is seen that a legislative change followed a long and sustained campaign in the annual staging of the Pink Dot event, while the anti-immigration protests represent a small concession in the immediate response to the first demonstration. As such they highlight two different ways protests have influenced the policy and legislative process, both as an immediate response and through a sustained social movement campaign. As to why these were the only two legal events to generate policy changes, it should be noted that they are the most attended protest events within the dataset. This suggests a link between attendance and outcome, particularly on issues that do not pose a direct political challenge to the PAP.

Outside policy changes, protests have also generated other forms of institutional interaction, particularly in the reaction to the “Mother Tongue” and “Green Dot” protests. In 2022, a PAP member of parliament attended a Pink Dot event for the first time, highlighting the growing acceptance of the event in Singaporean society (Channel News Asia, June 18, 2022). While these do not represent policy changes or concessions, they do highlight the use of protests to engage with the PAP. In turn, the positive responses or acknowledgements received indicate the legitimatisation of protests as a form of civic engagement.

However, while these protests stand out as the more prominent forms of engagement, most protests aimed at the government were largely ignored. In terms of more radical challenges to the institutional power of the PAP, explicit anti-government protests are rare. As the dataset highlights, there have also been few protests outside of Hong Lim Park seeking to normalise the right to protest. Of course, as already highlighted, these protests carry greater risks, and the PAP retains a wide range of tools in which to target activists and others who try and push the boundaries of accepted protest. This is both in a physical sense, but also in relation to the “OB Markers” which regulate behaviour. As such, while there have been significant interactions because of protests, in terms of institutional challenges, protests are indicative of a consultative space, rather than an inherently competitive one.

More substantial however is the emergence of an agenda-setting competitiveness resulting from protests, one that has also driven the institutional interactions discussed above. Of the protests that saw institutional interaction or responses, all were within the top ten most attended events in the dataset. What these events achieved was to place the issues they sought to promote or solve into national prominence, and in doing so highlighted the ability of civil society actors to influence the national conversation using collective demonstrations.

As the most high-profile events within the dataset, this is most evident in relation to the anti-immigration protests and Pink Dot. In the case of the former, the first protest not only generated national discussions on immigration, but in doing so attracted the attention of international media. Indeed, even after the concession, immigration concerns continue to be an important issue for many Singaporeans (see Dirksmeier Citation2020). While this agenda-setting ability has not presented a fundamental challenge to the rule of the PAP, it does highlight a competitiveness. Civil society actors can use protests to shape national discourses, which as George (Citation2020, unpaginated) notes, is “anathema to a governing elite that fundamentally believes that nobody else should set the agenda.”

In the case of Pink Dot, the annual event brought LGBT issues into the national conversation, with support for LGBT rights also growing since the first event (see Matthews, Lim, and Sevarajan Citation2019).Footnote2 Crucially however, protests have allowed Singaporeans to engage directly in this national conversation. Attending Pink Dot would be an obvious example of this, but so too was the “Wear White” counter demonstration which took place during the same weekend. It meant that during the weekend of these events, Singaporeans were effectively taking part in a wider societal discussion on same-sex relations, using protests as a form of engagement within this conversation. The National Library reading “sit-in” is also reflective of this cross-societal discussion, as Singaporeans have sought to use demonstrations to express themselves in relation to LGBT issues.

As such, protests have provided civil society actors with an agenda-setting capacity, equipping them with a “voice” to highlight a range of issues which can pressure the PAP into a response. The PAP of course retains numerous avenues in which to limit this agenda-setting power, including overt authoritarian measures such as refusing or shutting down protests to the explicit targeting of activists. The adaptive nature of its authoritarian methods also includes more subtle measures through which to stifle potential dissent. Its increasing focus on “digital influence” and establishment of an “Internet Brigade” made up of “young, internet savvy party activists” provides it with a tool through which to challenge anti-government sentiment and promote PAP messaging (Tan Citation2020, 1082). With many protests reliant on online spaces to promote their activity and objectives, this offers an avenue in which to discredit contentious voices rather than simply silencing them. As such, this agenda-setting ability remains limited and fragile.

Yet, as seen by the willingness of Singaporeans to participate in contentious protests, it is a competitiveness to the PAP’s dominance as the major actor in shaping public opinion which will have to be carefully managed. Protests have been utilised as a form of societal and political participation, not only in engagement with the PAP, but amongst other Singaporeans. While limited, significant protests such as those focused on LGBT rights and immigration concerns demonstrate not only a desire to engage in societal discussions, but an ability to influence them.

Politicised Spaces and Calibrated Control

This limited competitiveness in many ways reflects the shifts in state–society relations discussed earlier. The limited influence on policy is similar to the small concessions achieved by civil society organisations (see Ortmann Citation2015; Ang and Neo Citation2017). While the agenda-setting capacity of protests is in keeping with the shift from the PAP’s hegemonic discourse to one constituted by a greater plurality of societal voices (Ortmann Citation2019).

Yet any substantive changes related to the political system and in turn civil society remain resisted (Ortmann Citation2019, 189). The limits of civil society space are still defined by the PAP as seen with the introduction of POFMA and the 2017 amendments to protest. In the context of the PAP’s strategic liberalisation and the opening of civil society, the introduction of protests reflects a competitiveness similar to other developments in Singaporean civil society, rather than a fundamental change within it. There are competitive elements within these spaces, but they take place within boundaries, or “OB Markers” still set and maintained by the PAP’s tight control over society.

However, while this competitiveness remains limited, the finding that protests have largely been used for political aims, where Singaporeans seek and demand interaction with the state, represents an important development. In contrast to the PAP’s articulation of a civic society, one defined by its apolitical nature and in which participation is meant to harness the state’s “developmentalist goal” (Lyons Citation2017, 45), protests instead have largely been utilised to affect the political process. Most of these protests do not target the authoritarian nature of the PAP or push for democratisation. Instead, they often focus on day-to-day issues around public services and infrastructure. Yet how the PAP manages this political space and the potential challenges emerging from within it have important implications for state–society relations.

One such challenge is in relation to the future of Pink Dot and LGBT activism more generally. While Section 377A has been repealed, changes to the Constitution to stop legal challenges to the definition of marriage raise the question of how activists will respond. As reflected in the prevalence of LGBT issues within the dataset, they remain important, and whether activists on either side accept the legalisation of same-sex relations and changes to the Constitution delivered by the PAP remains to be seen. As such, the future trajectory of this debate, and the utilisation of protests in which to carry it out, could raise important challenges which not only influence policy, but also affect how the PAP manages the cross-societal debate which protests have helped facilitate.

While LGBT issues and activism is one of the more prominent potential challenges, the nature of a politicised space expressed through protest is that various and diverse issues may emerge. As was highlighted, protests related to economic and political issues rose in the aftermath of the Global Financial Crisis and the 2017 political scandals. At a time of global economic and political insecurity, with anti-globalisation, protectionist, and populist sentiment taking hold across the world, and with the PAP transitioning to a new prime minister and leadership generation, Singapore and the PAP may face a period of uncertainty. This period of uncertainty is compounded by the existing structural and demographic divisions which are becoming evident issues within Singapore. Government ministers have highlighted concerns over income inequality (The Straits Times, October 11, 2022). A growing number of young Singaporeans see racism as an important issue (Matthews, Teo, and Nah Citation2022, 51).Footnote3 These represent challenges to the PAP’s core ideology of meritocracy and racial harmony, and although engagement with these issues is not limited to physical protests, the politicised space facilitated by demonstrations provides a potential avenue in which to highlight these and other causes.

The suggestion is not that all these potential challenges will emerge, nor if they do, they will result in further liberalisations or offer any significant threat to the PAP. Overall protest attendance is still relatively small-scale, with only a few significant issues attracting attendance over 1,000. Further to this, the PAP still retains multiple avenues in which to minimise and control this politicised space, and the legal changes in 2017 to make protesting more difficult suggest they intend to do so. Domestic broadcast and print media are still state-owned, giving the PAP the ability to influence the coverage of protests or activists promoting potentially contentious issues. It can also utilise the wider legal, political, and social system to target protesters. It is this calibrated coercion which has defined the enforcement of social space in Singapore (George Citation2007). Indeed, the PAP could seek to remove the more overtly political demands emerging from protests while keeping the space to demonstrate open for issues it deems suitable.

Yet such an approach also brings risks, with the PAP potentially underestimating public support for protest issues, or in seeking to reduce and stop protests, generating greater support for and public attention to them. As such, the significant point is that protests represent a contentious and political use of civil society space, one that the PAP knows it must manage as it continues to seek legitimacy and popular support for its dominance over the political system.

While the influence of protests has been limited, the findings of the PEA show they have had an impact. The emergence and existence of this political space provides avenues for other issues to become prominent, particularly at a time of economic and political uncertainties. How the PAP responds to these potential challenges could have important implications for its continued legitimacy. Whether or not they emerge, and how in turn the PAP does respond, is beyond the scope of this article. However, as a contentious political space in civil society, it represents an important site for examining and understanding the shifting dynamics of state–society relations.

Conclusion

The central aims of this article were to provide an overview of the dynamics of protest since their legalisation, and to examine the competitiveness their introduction has brought into Singaporean civil society. The PEA showed that contrary to claims of Singaporeans being apolitical, they have protested over a wide range of issues. From expressing solidarity in response to international events and promoting animal rights, to demonstrations over utility prices and calls for the prime minister to resign. Further to this, the findings highlighted the use of protests by those excluded from Hong Lim Park, in particular migrant workers and other foreign nationals. While there have been illegal protests carried out by Singaporeans, these are rarer and often involve just a handful of people. As such, the PEA has provided insight into the dynamics of protests both in and outside of Hong Lim Park.

As highlighted, the legalisation of protests represented a managed liberalisation by the PAP to open societal space while ensuring its continued role as the dominant actor. The findings demonstrate that overall, there have been limited, but still important competitive challenges to the PAP’s dominance, particularly the policy changes in relation to the anti-immigration and Pink Dot demonstrations. As the two most attended events, these policy changes were facilitated by the profile they achieved, and significantly they highlight both an agenda-setting ability and in the case of Pink Dot, the use of protests to engage in a cross-societal discussion. Although these indicate the continued growth of civil society as a competitive actor, it was argued the most significant finding was the majority of protests targeting the government. This demonstrates a politicised space in civil society, and one that challenges the PAP’s articulation of an apolitical “civic” interpretation. While its impact remains limited, the potential challenges which may emerge from this contentious space were discussed.

These findings provide important insights into the use of a civil society space, and how this use provides challenges to the PAP’s dominance over it. However, while these insights have value for understanding this space, it is also important to note the limitations of the research and avenues to address these in future. As the aim of the PEA was to provide a broad overview of demonstrations by analysing their issues, targets, and influence on the policy process, further aspects of protests are still to be explored. For example, who organises protests, the type of audience they attract, and their ability to generate resources would offer fruitful avenues of research and further insight into the features of protest.

Further to this, while the introduction of protests represents a contentious space, it is not a space in isolation, and is influenced, and in turn influences, other areas of civil society activism. Therefore, understanding the interaction between these spaces, for example the interplay between physical and online protests and contestation, as well as the influence of protest in resource mobilisation, would provide insight into the wider dynamics of activism.

As a contentious space in civil society, protests offer an important avenue for research examining changing dynamics within state–society relations. Not only will this provide further insights into the competitiveness emerging from this space and wider civil society, but also the future challenges which the PAP will have to manage in its pursuit of remaining the dominant political actor within Singapore.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr Oliver Turner and Dr Benjamin Martill for their encouragement in producing the article, alongside the Journal of Contemporary Asia editor Dr Kevin Hewison and the anonymous reviewers who provided critical but constructive feedback. For all this help, any remaining faults are my own.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflicts of interest were present in the research process.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the author upon reasonable request.

Notes

1 The Online Citizen initially closed after failing to provide funding information to the Infocomm Media Development Authority, resulting in the cancellation of its license. However, the website relaunched in September 2022 based in Taiwan, taking it outside of the remit of Singaporean media regulation (see Channel News Asia, September 16, 2022).

2 Although a majority of Singaporeans (63.6%) in 2019 still indicated they felt sexual relations between the same sex were always, or almost always, wrong, this had reduced from 80.4% in 2013 (Matthews, Lim, and Sevarajan Citation2019, 23).

3 In a survey carried out by Channel News Asia and the Institute of Policy Studies, 63.7% of respondents aged between 21 and 35 highlight racism as an important issue within society, rising from 49.5% in 2016 (see Channel News Asia, April 2, 2022).

References

- Abdullah, W. 2020. “‘New Normal’ No More: Democratic Backsliding in Singapore after 2015.” Democratization 27 (7): 1123–1141.

- Ang, E., and S. Neo. 2017. “Relations and Activism: Migrant Worker Rights.” In A History of Human Rights in Singapore: 1965–2015, edited by J. Song, 114–131. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Barr, M. 2010. “Marxists in Singapore? Lee Kuan Yew’s Campaign against Catholic Social Justice Activists in the 1980s.” Critical Asian Studies 42 (3): 335–362.

- Barr, M. 2014. “The Bonsai under the Banyan Tree: Democracy and Democratisation in Singapore.” Democratization 21 (1): 29–48.

- Barr, M. 2016. “Ordinary Singapore: The Decline of Singapore Exceptionalism.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 46 (1): 1–17.

- Chua, B. 1994. “Arrested Development: Democratisation in Singapore.” Third World Quarterly 15 (4): 655–668.

- Chua, B. 2000. “The Relative Autonomies of State and Civil Society in Singapore.” In State‐society Relations in Singapore, edited by G. Koh and O. Ling, 62–76. Singapore: Oxford University Press.

- Dirksmeier, P. 2020. “Resentments in the Cosmopolis: Anti-immigrant Attitudes in Postcolonial Singapore.” Cities 98: 102584. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2019.102584.

- George, C. 2007. “Consolidating Authoritarian Rule: Calibrated Coercion in Singapore.” The Pacific Review 20 (2): 127–145.

- George, C. 2012. Freedom from the Press: Journalism and State Power in Singapore. Singapore: NUS Press.

- George, C. 2015. “Legal Landmines and OB Markers: Survival Strategies of Alternative Media.” In Battle for Hearts and Minds: New Media and Elections in Singapore, edited by H. Tan, A. Mahizhnan, and P. Hwa Ang, 29–47. Singapore: World Scientific.

- George, C. 2020. “Passion Made Possible – Or Punishable?” In PAP v PAP, edited by C. George and D. Low, Ch. 15. No place: Self-published. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?pcampaignid=books_read_action&id=jukJEAAAQBAJ.

- Goh, D., and N. Pang. 2016. “Protesting the Singapore Government: The Role of Collective Action Frames in Social Media Mobilization.” Telematics and Informatics 33 (2): 525–533.

- Gomez, J. 2006. “Restricting Free Speech: The Impact on Opposition Parties in Singapore.” The Copenhagen Journal of Asian Studies 23 (1): 105–131.

- Gwynne, J. 2013. “Slutwalk, Feminist Activism and the Foreign Body in Singapore.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 43 (1): 173–185.

- Hutter, S. 2014. “Protest Event Analysis and Its Offsprings.” In Methodological Practices in Social Movement Research, edited by D. Della Porta, 335–367. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kaur, P., and S. Yeo. 2017. “Inhuman Punishment and Human Rights Activism in the Little Red Dot.” In A History of Human Rights in Singapore: 1965–2015, edited by J. Song, 36–53. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Koopmans, R., and F. Neidhart, 1999. “Protest as a Subject of Empirical Research.” In Age of Dissent: New Developments in the Study of Protest, edited by D. Rucht, R. Koopmans, and F. Neidhardt, 7–16. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Koopmans, R., and D. Rucht. 2002. “Protest Event Analysis.” In Methods of Social Movement Research, edited by B. Klandermans and S. Staggenborg, 231–259. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Koopmans, R., and P. Statham. 1999. “Political Claims Analysis: Integrating Protest Event and Political Discourses Approaches.” Mobilization 4 (2): 203–221.

- Lawson, S. 2001. “Sanitizing Ethnicity: The Creation of Singapore’s Apolitical Culture.” Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 7 (1): 63–84. .

- Lee, T. 2002. “The Politics of Civil Society in Singapore.” Asian Studies Review 26 (1): 97–117.

- Lee, T. 2005. “Gestural Politics: Civil Society in ‘New’ Singapore.” Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 20 (2): 132–154.

- Lee, T. 2010. The Media, Cultural Control and Government in Singapore. London: Routledge.

- Low, D. 2020. “Development with Limited Democracy.” In PAP v PAP, edited by C. George and D. Low, Ch.4. No place: Self-published. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?pcampaignid=books_read_action&id=jukJEAAAQBAJ.

- Lyons, L. 2017. “A Curious-Space ‘In-between’: The Public/Private Divide and Gender-based Activism in Singapore.” Gender, Technology and Development 11 (1): 27–51.

- Lyons, L., and J. Gomez. 2005. “Moving Beyond the OB Markers: Rethinking the Space of Civil Society in Singapore.” Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia 20 (2): 119–131.

- Matthews, M., L. Lim, and S. Sevarajan. 2019. Religion, Morality and Conservatism in Singapore. Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, IPS Working Paper 34.

- Matthews, M., K. Teo, and S. Nah. 2022. “Attitudes, Action and Aspirations: Key Findings from the CNA-IPS Survey on Race Relations 2021.” Singapore: Institute of Policy Studies, IPS Exchange Series 22.

- McPhail, C., and D. Schweingruber. 1999. “Unpacking Protest Events: A Description Bias analysis of Media Records with Systematic Observations of Collective Action – The 1995 March for Life in Washington, D.C.” In Acts of Dissent: New Developments in the Study of Protest, edited by D. Rucht, R. Koopmans, and F. Neidhart, 164–195. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Ministry of Home Affairs. 2017. “Public Order (Amendment) Bill 2017.” Ministry of Home Affairs, Government of Singapore. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://www.mha.gov.sg/mediaroom/press-releases/public-order-amendment-bill-2017/.

- Ministry of Manpower. 2013. “Enhancements to Foreign Manpower Policy for Quality Growth and Higher Wages.” Ministry of Manpower, Government of Singapore. Accessed September 27, 2021. https://www.nas.gov.sg/archivesonline/data/data/pdfdoc/20130305002/mom_press_release_budget_2013_(260213).pdf.

- Mutalib, H. 2000. “Illiberal Democracy and the Future of Opposition in Singapore.” Third World Quarterly 21 (2): 313–342.

- Oliver, P., J. Cadena-Roa, and K. Strawn. 2003. “Emerging Trends in the Study of Protest and Social Movements.” In Political Sociology for the 21st Century: Research in Political Sociology: Vol. 12, edited by B. Dobratz, L. Waldner, and T. Buzzell, 213–244. Stanford: JAI Press.

- Ortmann, S. 2011. “Singapore: Authoritarian but Newly Competitive.” Journal of Democracy 22 (4): 153–164.

- Ortmann, S. 2012. “Policy Advocacy in a Competitive Authoritarian Regime.” Administration & Society 44 (6): 13S–25S.

- Ortmann, S. 2015. “Political Change and Civil Society Coalitions in Singapore.” Government and Opposition 50 (1): 119–139.

- Ortmann, S. 2019. “The Growing Challenge of Pluralism and Political Activism: Shifts in the Hegemonic Discourse in Singapore.” In The Limits of Authoritarian Governance in Singapore’s Developmental State, edited by L. Rahim and M. Barr, 173–194. Singapore: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pang, E., and L. Lim. 2016. “Labor, Productivity and Singapore’s Development Model.” In Singapore’s Economic Development: Retrospection and Reflections, edited by L. Lim, 135–168. Singapore: World Scientific.

- Phillips, R. 2014. “‘And I Am Also Gay’: Illiberal Pragmatics, Neoliberal Homonormativity and LGBT Activism in Singapore.” Anthropologica 56 (1): 45–54.

- Pink Dot. 2011. “FAQ: Things to Know about Pink Dot. Pink Dot SG.” Accessed March 22, 2021. https://pinkdot.sg/2011/05/faq-things-to-know-about-pink-dot/.

- Prakash, P., and W. Abdullah. 2022. “The State Prunes the Banyan Tree: Calibrated Liberalisation in Singapore.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 76 (4): 1–19.

- Prime Minister’s Office. 2008. “National Day Rally 2008.” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore. Accessed April 4, 2022. https://www.pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/prime-minister-lee-hsien-loongs-national-day-rally-2008-speech-english.

- Prime Minister’s Office. 2022. “National Day Rally 2022.” Prime Minister’s Office Singapore. Accessed August 22, 2022. https://pmo.gov.sg/Newsroom/National-Day-Rally-2022-English.

- Rodan, G. 1993. “Preserving the One-Party State in Contemporary Singapore.” In Southeast Asia in the 1990’s: Authoritarianism, Democracy, and Capitalism, edited by K. Hewison, R. Robison, and G. Rodan, 75–108. Sydney: Allen and Unwin.

- Rodan, G. 2017. “Singapore’s Elected President: A Failed Institution.” Australian Journal of International Affairs 72 (1): 10–15. .

- Rucht, D., and F. Neidhardt. 1999. “Methodological Issues in Collecting Protest Event Data: Units of Analysis, Sources and Sampling, Coding Problems.” In Acts of Dissent: New Developments in the Study of Protest, edited by D. Rucht, R. Koopmans, and F. Neidhardt, 65–89. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield.