Abstract

This article explores the gendered dynamics of revolutionary movements through a focus on women’s bodies as tools of resistance and protest. In the Myanmar Spring Revolution, gendered relations of power articulate with military authority to engender both women’s activism and military responses. To maintain power, the Myanmar military have sought to regulate women’s behaviour – and quell the protest – through attention to women’s bodies, sexuality, and reproductive potential. In response, women activists have mobilised against both state control and the violation of women’s bodies in imaginative and transgressive ways, using their bodies as well as gendered artefacts to subvert patriarchal and military norms. This analysis shows how women’s bodies constitute both the material object of protest – in the virtual and physical spheres – and the subject of resistance, aiming to challenge gendered logics. It means that the gendered body must be taken seriously in studies on revolutions and protests. The integral yet historically overlooked role of women in Myanmar’s revolutionary movements necessitates a gender-conscious analytical lens to fully comprehend the transformative potential and the power dynamics of such upheavals.

Key Words:

In early 2021, the Myanmar military assumed power via a coup (see Chambers and Cheesman Citation2024). Within days, the streets of Yangon and other major cities swelled with protests. Civil servants from across the county, refusing to work for the new military regime, launched a civil disobedience movement. Female garment workers and activists from ethnic minority backgrounds spearheaded mass protests. Through creative street performances – that ranged from crossdressing and drag queens to dance performances and public displays of female underwear and sanitary products – a new movement emerged which in its opposition to the patriarchal politics of the military take-over also questioned conservative gender norms (see Jordt, Tharaphi Than, and Sue Ye Lin Citation2021; Khin Khin Mra Citation2021; Marlar, Chambers, and Elena Citation2023).Footnote1 The military response was slow at first, but within a few weeks it was brutal, with thousands of arrests, killings, and disappearances. Women protestors faced specific gendered threats when arrested, including rape and other forms of sexual assault (AAPPB Citation2023). While the violence diminished the street protests, they nevertheless continued. Within these, women’s leadership and participation persevered, infusing what would be known as the Myanmar Spring Revolution with feminist claims for gender equality and women’s rights.Footnote2

However, as Jayawardena (Citation2016, 24) succinctly observes, women’s involvement in revolutionary struggles across Asia has largely failed to subvert patriarchal structures, despite the important role played by women activists and women’s associations in furthering nationalistic movements. Instead, upon achieving independence, women have often been asked to relinquish potential public and political positions for gendered roles deemed more appropriate: as supportive mothers and wives, rather than as leaders in their own right. This applies also to the Myanmar case. While women have always been involved in protests in Myanmar, their participation has typically been circumscribed by gendered norms, resulting in female soldiers and activists being positioned primarily as followers, rather than as leaders (Harriden Citation2012; Tharaphi Than Citation2014). Ideas around ethnicity or nation have trumped feminist concerns or calls for gendered change. Mobilising for women’s rights has been positioned – by male leaders – as secondary to the “real” cause of the movements, whether armed or otherwise (see Women’s League of Burma Citation2011; Hedström Citation2016). There has also been widespread involvement of upper-class or elite women in nationalistic campaigns in the country who empowered themselves as moral guardians and mothers of the Burmese Buddhist nation (Tharaphi Than Citation2011, 540). Such narratives have yoked religion to race, gender, and nation (Saha Citation2022, 47). In these movements, women have been projected as cultural carriers protecting Myanmar culture from foreign influences and as reproducers of the boundaries of national groups by not marrying foreigners. Indeed, as writer Mi Mi Khaing (Citation1984, 26) infamously claimed, without evidence, Burmese women find traditional roles and responsibilities “reasonably comfortable” and would apparently only “act, organise, and associate” to further national or religious needs, having no wish to upset traditional concepts or hierarchies (Mi Mi Khaing Citation1984, 159).

These gendered narratives have been reinforced through decades of military rule and war that have shaped the dynamics of gender, bodies, and nation in Myanmar, and the possibilities for protest and resistance. What in this article is called patriarchal military logic, or the idea that the military state is “protecting” the country and its citizens through violent means and complete obedience and subordination on behalf of those “protected” – a point made by Young (Citation2003) – has dominated both political and private life. Control over households and individuals has been at the centre of state policies and counter-insurgency campaigns aimed at eradicating opposition. In Myanmar, the perseverance of patriarchal military logic can in some ways be linked to Bamar Buddhist beliefs of male physical or spiritual power, hpoun (Spiro Citation1993, 322). It is believed that only men can attain hpoun, and as a result they are intellectually, morally, and spiritually higher than women, making hpoun an intrinsically gendered concept (see Harriden Citation2012). Even though hpoun is linked to Buddhism, the position of Buddhism as state religion means that the concept has travelled across the country to also affect non-Buddhist communities (Belak Citation2002). Importantly for this analysis, hpoun legitimises and explains the dominance of men in the social as well as political realm, facilitating a gender order that sees men as the protectors of both home and nation, and women as its reproducers. Indeed, as Min Zin (Citation2001) argues, hpoun is frequently yoked together with military prowess and might, illustrating how hpoun empowers the relationship between gender, body, and nation. However, this perceived inherent spiritual superiority is not hegemonic, and is challenged by women’s involvement in public roles and in revolutionary struggles. Contrary to what Mi Mi Khaing alleges, women in the Spring Revolution are protesting both traditional concepts and military power, understanding these to be linked.

In this article the gendered dynamics of the Spring Revolution are explored for the period February to June 2021. By focusing on the relationship between gendered bodies, military power, and protests in the aftermath of the military coup, it will show how and why women have used the protests as an opportunity to mobilise and organise against state control and violation of women’s bodies in ways that are both imaginative and transgressive. Like other protests in Myanmar’s history and military responses to these – spanning the anti-colonial movement to the 1988 student uprising and the 2007 so-called Panty ProtestsFootnote3 – the 2021 Spring Revolution also draws on gendered narratives. However, the sheer scale and the digital composition of the Spring Revolution set it apart from previous revolutionary moments. The integral yet historically overlooked role of women in revolutionary movements such as the Myanmar Spring Revolution necessitates a gender-conscious analytical lens to fully comprehend the complex power dynamics and transformative potential of such upheavals.

This article is a collaborative effort, combining digital ethnography with in situ participant observation to explore the gendered dynamics of resistance, particularly in the initial months following the coup.Footnote4 Conducted in a conversational style, interviews with protestors were done amid ongoing protests, and in multiple settings, including public spaces, private locations, and online platforms – whichever was deemed to be most safe. In total, 15 interviews were conducted, representing diverse perspectives from individuals engaged in the protests across Yangon, Tanintharyi regions, and Karenni/Kayah state. While interview excerpts are not heavily featured in the analysis, the insights gathered from these discussions have significantly enriched the comprehension of the experiences and embodied knowledge of those actively involved in the movement. On-site observation took place during five protest events in Yangon. Supplementing this, numerous social media posts on platforms such as Facebook and Twitter, and printed and online news media were closely monitored throughout the protest period. Additionally, the authors have extensive experiential and accumulated knowledge of gender politics in Myanmar, amassed over many years of undertaking research on gender, conflict, and politics. These experiences and insights allowed us to put the background literature on bodies and gender in revolutions in conversation with the actual events and activities in Myanmar.

This article is organised in several sections. The next section expands on the analytical framework, putting feminist discussions of women’s bodies in social movements in conversation with the literature on gender and revolutions. This is followed by a brief overview of Myanmar and its militarised rules and regulations to argue that gendered relations of power articulate with military authority to engender both women’s activism and military responses. The analysis then follows, where the centrality of women’s bodies in the Spring Revolution is explored. It is demonstrated that ideas about women’s purported weakness and impurity, particularly associated with menstruation, have offered the anti-coup movement productive possibilities for contestation. Next, ideas about race and religion are traced for how they have shaped diverse women’s experiences of violence in the post-coup moment. Finally, the realm of digital activism is explored through online protests, wherein women have strategically deployed visual representations of their own bodies as a form of resistance to “speak back” to military attempts to discipline and terrorise the public through pictures of bruised and hurt women. This empirical analysis illustrates and allows learning from the many creative and defiant ways that women use gendered bodies and artefacts to subvert patriarchal and military norms. It also demonstrates the importance of the gendered body in protest: it is both the subject of resistance and the material object of protest.

Gender, Bodies, and Revolutionary Change

Bodies are key for understanding revolutions and resistance projects because revolutionary movements involve subjects that are embodied as well as gendered and racialised. These protesting bodies gain meaning and achieve change within, not outside of, specific political spaces and sites (see Sasson-Levy and Rapoport Citation2003). As Parkins (Citation2000, 73) argues “bodies inhabit specific social, historical and discursive contexts which shape our experience(s) and our capacities for political contestation.” These “contexts” include ideas about appropriate gender norms and behaviour in society, such as notions about sexuality, reproduction, and gender roles, ideas that often are at the core of revolutionary narratives. In other words, and as we will discuss further below, “flinging” female underwear into Burmese embassies around the world, as the 2007 “Panties for Peace” campaign encouraged women to do, or stringing female clothes across roads to prevent military trucks/security forces from entering, as the more recent htamein campaign did, only makes sense because these draw on gendered and cultural stereotypes in the Myanmar context. Such gendered and racialised contexts produce particular opportunities for resistance and disruption, positioning female bodies as both powerful objects for and subjects of protest. For example, feminist research on naked protests suggests that the act of stripping in public spaces, when done by women, upsets social norms and morals by women not acquiescing to demands that women’s bodies be sexy, available, and compliant. This is powerful as a form of protest partly because it enables the protesting female body to move from “commodified object” to “resisting subject” (Sutton Citation2007, 145), or as Gaikwad (Citation2009) argues, disturbs gendered norms of respectability. In this sense, nudity is effective as a form of protest because it upsets ideas about the use and purpose of women’s bodies – as potential or actual mothers, concerned with domestic affairs only (Tamale Citation2017, 68). Similarly, republican women imprisoned in the conflict in Northern Ireland used menstruation as a form of protest – both upsetting ideas about women’s appropriate roles as mothers and disrupting the stigma and shame associated with this (see Wahidin Citation2019). As O’Keefe (Citation2006, 546) explained: “The only weapon they had were their bodies”– and women who menstruated would smear their blood on the walls “to challenge the prison system” – transforming the female republican body into a site of resistance rather than an object of discipline. Here, female bodies become effective as a vehicle for protest when they transgress the gendered spaces and roles associated with women: in Gaikwad’s (Citation2009) terms, they step outside or, as Tamale (Citation2017) explains, reverse the social order by giving prominence to, indeed inhabiting, prevailing beliefs deeming female bodies – and their assumed functions – as sexual, shameful, and dirty (see Wahidin Citation2019). Because women’s bodies, and their bodily functions, belong in the reproductive sphere, the mere act of taking up public space challenges an overarching gender order positioning women in the domestic sphere (see Sasson-Levy and Rapoport Citation2003). These are gendered norms that bolster conservative and military gender orders, in which the “presumed rightful place” of men as head of households and nations is reaffirmed (see Young Citation2003; MacKenzie and Foster Citation2017). As symbols of the collective, women’s bodies and movements must therefore be controlled and protected (see Yuval-Davis Citation1995).

In Myanmar, women’s bodies have historically been situated as cultural bearers of the home and the country, responsible for protecting the culture from foreign influences and ensuring the reproduction of the nation by marrying within their amyo (their ethnic community). Indeed, during the independence struggle from the British, historian Ikeya (Citation2011, 162) records how women’s sexuality and bodies were monitored by political and religious leaders: women who were romantically linked to foreign men, or who were seen as “improperly” dressed faced physical and verbal attacks by religious and political leaders. This, writes Phyo Win Latt (Citation2020), represented a shift from earlier narratives when men had been positioned as subjects to uphold or represent amyo. Thus, it was during the early 20th century, and in the discussion for independence, that Buddhist teachings, which soon found their way into popular narratives, began to focus on the role of women in protecting the amyo from foreign blood and “impure origins” in order to foster a nation of blood-related people (Phyo Win Latt Citation2020, 79–81).

Perhaps not surprisingly, the first coup in 1962 was justified by the military as a necessary evil to protect against the disintegration of the nation. The dictatorship swiftly outlawed birth control to ward off Bamar demographic decline (Burma Socialist Programme Party Citation1966, 121). These notions have carried over to the present period, where Muslim men’s virility as well as Muslim women’s fertility are understood as threats to Burmese women and the nation (Frydenlund and Shunn Lei Citation2021). In the protests following the 2021 coup, sexual and racialised slurs directed by the military against female protestors accused women of betraying their race and their gender roles by associating with Muslim men in particular and foreign men in general, dressing “improperly”, and questioning military rule. These examples shed light on how gendered and racialised tropes have been used to mark the boundaries of the imagined nation and its ideal inhabitants; to monitor and regulate women’s behaviour; and to shore up support for patriarchal orders by calling out threats to the presumed “dilution” of the nation.

In other words, gender relations of power feature prominently in revolutionary discourses, which, as Moghadam (Citation1997, 139) points out, “always include notions of the ‘ideal’ society,” whether emancipatory or patriarchal. In this way, ideals about appropriate gender roles and the regulation of family law, labour participation and political opportunities inform both the ways in which revolutions are fought and experienced as well as what kind of society they result in. Because revolutions promise societal change, and because women’s behaviour and bodies become markers for the type of society the revolution envisions, women – and their bodies – become “objects of control by different actors in order to (signify) political and societal change” (El Said, Meari, and Pratt Citation2015, 5). This means that gender dynamics affect both revolutionary situations and revolutionary outcomes. Recent work shows that extensive female participation leads to more creative protests (as seen in Myanmar) but also, importantly, more successful and egalitarian outcomes, at least in the short to medium term (see Marks and Chenoweth Citation2020). This also means, as El Said, Meari, and Pratt (Citation2015, 5) argue, writing about revolutions in the Arab world, that “women’s bodies become especially powerful tools of resistance against dictatorship, colonialism and patriarchy.” Thus, the widespread involvement of women, especially when these women, as in Myanmar, employ unruly, disruptive bodily acts to further an egalitarian revolutionary agenda, have far-reaching material, social, and political effects. The next section will briefly trace how these gendered dynamics have historically been constituted in Myanmar, through practices of patriarchal military logic.

The Gendered Legacy of Military Rule

The military has dominated the political landscape through successive military regimes since Myanmar’s independence from the British in 1948. Throughout the country’s five decades of military rule, the state’s dominant gender ideology defined women as wives and mothers foremost (Khin Khin Mra Citation2021). The military was recognised for its harsh discipline and violent control of both its ranks and the people living in the country. This included the use of sexual violence as a way to quell resistance (UN Fact Finding Mission Citation2019). These violent practices helped sustain militarised patriarchal norms, and their associated “authoritarian, hierarchical and chauvinistic values” that underpinned the transition from military rule to a form of hybrid, semi-democratic state in 2011 (Harriden Citation2012, 307). The transition was facilitated by the 2008 Constitution, which guaranteed the military held 25% of parliamentary seats as well as key ministerial positions (see Turnell Citation2012). This constitution effectively maintained the concentration of power in the military, with male leadership, patriarchal rule, limited protection and provision of individual rights and the marginalisation of ethnic minorities’ demands for self-determination within a federal union (Williams Citation2014, 119). The constitution thus allowed for continued male dominance in legislative and public affairs and can be understood as set of gendered rules framing women as weak and in need of protection (Khin Khin Mra and Livingstone Citation2020, 247). It was also an attempt by the military to maintain power even after the transition had begun, effectively achieving “the rule of men” through constitutional law (Crouch and Lindsey Citation2014, 9; Williams Citation2014, 119–121).

Article 352 of the constitution states: “nothing in this section shall prevent the appointment of men to positions that are naturally suitable for men only … in appointing or assigning duties to civil service personnel.” Along with references to women principally as mothers (Article 32-a), the constitution emphasise gendered social norms that restrict women’s roles in public and political life (see Khin Khin Mra and Livingstone 2022). During Myanmar’s nationwide ceasefire process in 2015, although women were active as observers and facilitators, and in civil society organisations’ peace forums, only a limited number of women were invited to participate in a formal capacity in the official negotiation processes (AGIPP Citation2017). The military-founded Union Solidarity and Development Party passed a set of laws in 2015 which situated women’s reproductive potential as critical to national belonging and nation-building, emphasising women’s role as mothers and wives. Commonly known as the race and religion protection laws, and backed by an association of ultra-nationalist Buddhist monks, they outlawed polygamy, limited the number of children Muslim women could have, and restricted inter-faith marriages by requiring that non-Buddhist men first convert to Buddhism (Amnesty International Citation2015). The aim was to prevent Burmese women from marrying men from other religions and races, particularly Muslims.Footnote5 This suggests anxiety on the part of the military leadership and its political allies over the role and lasting impact of the military on society, and the military gender order writ large. Clearly, the patriarchal and nationalistic norms endorsed by the military are not as stable as they would like them to be, or they would not need to legislate it, or indeed, violently enforce it as they did with the coup in 2021, abruptly ending the decade of semi-democratic reforms (2011–2021). The next subsection explores the centrality of women’s bodies, sexuality, and reproductive potential in the protests, and the military’s responses.

Gendered Dynamics of Resistance and Political Violence

The coup returned an almost fully androcentric decision-making structure, with only one woman appointed to the State Administration Council (The Global New Light of Myanmar, February 4, 2021). Anxieties about the assumed disintegration of the nation, and a resulting loss of control were manifested in the first statement released by the military justifying the coup, citing threats to national security and solidarity (Reuters, February 1, 2021). The coup can in this way be read as a nostalgic yearning for an ordered and patriarchal past that only the military can reinstate (see MacKenzie and Foster Citation2017). Though, as noted by Khin Khin Mra and Livingstone (2023, 44), the previous decade of democratic reforms had done little to challenge patriarchal rule, with recent surveys on gender and political change showing that even many women prioritised male, rather than female leadership (Shwe Shwe Sein Latt et al. Citation2017). Yet, in the protest following the coup, women were at the forefront.

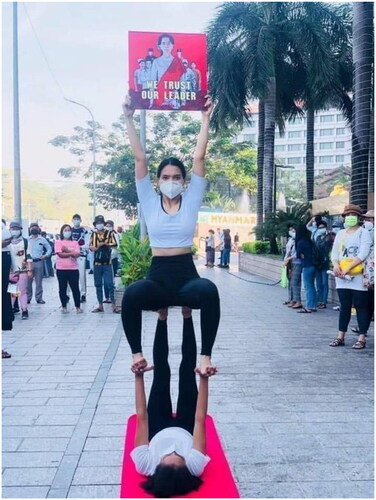

A general strike by factory workers, a majority of them women, was almost immediately organised following the coup. Across the country women of different ages and social backgrounds spearheaded creative and carnivalesque anti-coup protests (Loong Citation2022). Young women such as Esther Ze Naw and Ei Thinzar Maung, from the minority Kachin and Shanni communities, respectively, led thousands of people out on the streets in Yangon, just days after the coup. Other young women played with stereotypical gender roles by marching in “princess protests”, dressed in ballgowns while others held mocking English-language slogans such as “I don’t want dictatorship. I just want boyfriend,” “My ex is bad, but Myanmar military is worse” (Lau Citation2021). Significant public attention was generated by a young woman in a pink bikini holding a placard saying, “military coup power is under my bikini” (). Her photo went viral on social media from February 10, 2021. Famous actresses and models, such as Aye Myat Thu, also participated in the protest using their bodies to draw public attention to the coup (). This highly visible involvement of women from across Myanmar in the anti-coup movement effectively spoke back against the overarching expectation that women should be staying home and illustrates the critical use of gendered bodies as tools for resistance. Indeed, as Eileraas (Citation2014, 43) notes with regards to women’s protests in Egypt, the deployment of women’s naked or semi-clad bodies as a form of public resistance has the capacity to “reimagine vulnerability as a basis for solidarity and tool for social change.”

Figure 1. Protesting young woman in pink bikini.

Source: https://twitter.com/pyaeswanmgmg/status/1359447245465088002, Pyae Swan @pyaeswanmgmg.

Figure 2. Aye Myat Thu, a well-known model, using women’s bodies to draw public attention to the coup.

Source: https://twitter.com/pyaeswanmgmg/status/1359447245465088002, Pyae Swan @pyaeswanmgmg. This public website no longer exists.

However, women’s bodies were soon situated at the centre of state narratives and policies aiming to “protect” the nation from what the junta described as threats of foreign invasion and disintegration. The initial response by the military was focused on the impropriety of female protesters, supposedly wearing culturally inappropriate clothes. In a speech broadcast just a few weeks after the coup had been announced, General Min Aung Hlaing, the head of the junta, attempted to discipline and regulate female behaviour through calls to supposedly traditional values by critiquing “those wearing indecent clothes contrary to Myanmar culture … Such acts intend to harm the morality of people, so legal actions are necessary” (The Global New Light of Myanmar, March 2, 2021). In fact, participant observation confirmed that most women wore everyday clothes to the protests. The general’s language suggests that women’s bodies in public spaces represented a threat to the moral order in ways that men’s bodies did not. This language was matched by social media posts by pro-military as well as anti-military groups targeting both female protestors as well as women who were not actively renouncing the coup, depicting them as sexually promiscuous (cited in The Diplomat, August 9, 2021). For example, female teachers who did not take part in the civil disobedience movement were a focus of these campaigns, as shown in . In the cartoon, a soldier asks the teacher whether she is ready to begin teaching. The teacher confirms that she is, with a suggestive wiggle of her backside. The conversation between the teacher and solider can be read as being demeaning or belittling to the teacher. The cartoon objectifies the teacher by focusing on her physical appearance and reducing the teacher to her body, which is irrelevant to the context and undermines her dignity. Such examples highlight the centrality of women’s bodies to contestation over gender roles and norms within the broader revolutionary agenda, as well as within military responses.

Figure 3. A soldier and a teacher.

Source: Cartoon Wai Yan, Taunggyi, Reproduced on several public social media sites.

Thus, the use and deployment of gendered norms reflects not only the decades of military rule but also contestation of this rule, wherein protest has provided activists with generative opportunities to challenge that rule. The next three sections of the article consider how these gendered dynamics are implicated in experiences of, and responses to military violence. The effects of these gendered dynamics are traced from the htamein protests through to experiences of gender-based violence and online forms of activism to explore how, and why, women’s bodies have become such powerful sites of contestation to military rule.

Intimate protests

In Myanmar, menstruation is commonly described as “rotten” or “bad” blood (thway pote) and considered unclean. The taking of thway pote cha say, a kind of traditional medicine aimed at expelling this bad blood, is widespread. A woman interviewed in Skidmore’s (Citation2002, 86) ethnographic research in late 1990s Yangon recounts that “[w]omen think that it is very important to bleed. If you don’t, the blood becomes rotten and comes upward and anything can happen. So it needs to come out thoroughly and you need to get rid of the rotten things.” Menstruation is widely believed to be dirty (Ceyrac Citation2019). According to this belief, men’s perceived hpoun can be harmed and diminished by menstruation, particularly when men’s clothing comes into contact with women’s underclothes, or when men walk underneath a clothesline hung with women’s undergarments. Accordingly, many households wash women’s clothes separately from male clothes, and use separate clotheslines to dry them so as not to “pollute” male clothing. Young boys are taught not to go under the lines of women’s undergarments and men tend to avoid walking under women’s underclothing to protect their hpoun. This means that there is a tendency to associate women’s bodies, and their undergarments, with impurity. Women are therefore compelled to hang their underclothing, including htamein, lower than men’s clothing, or at the back of the house. Myths around women’s alleged impurity and their undergarments as contaminants reinforce women’s lower status (Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi Citation2012, 123–131).

During the early weeks of the Spring Revolution, women protestors effectively employed these gendered superstitions to both physically protect protestors and challenge ideas of female inferiority. In early 2021, in opposition to the military junta, protestors began flying htamein flags, erecting make-shift barricades out of htamein and menstrual pads and stringing up clotheslines hung with these. These htamein protests – led by young women – effectively united women from different ages and backgrounds who were already at the heart of the anti-coup protests in the early days. By painting sanitary pads red and displaying these in public, women collectively challenged the idea of menstruation – and bleeding female bodies – as shameful. At the same time, women contested military power by drawing on prevalent misogynistic beliefs holding menstrual blood as harmful to men’s hpoun. They smeared photos of General Min Aung Hlaing with red paint, attaching sanitary pads to pictures of his face (see ). Posters read: “This bra protects me better than the military”; “the military can no longer provide protection for us not even at the level of a pad”; “women are more than just bodies”; and “women’s affairs are the country’s affairs.” However, both wider society and the military considered these acts inappropriate to religious and social norms, with military leaders as well as foot soldiers being “notoriously superstitious” and wary of women’s underwear and menstrual blood (Marlar, Chambers and Elena 2023, 80).

Figure 4. General Min Aung Hlaing rejected.

Source: Public post at Facebook account, Women’s League of Burma (WLB).

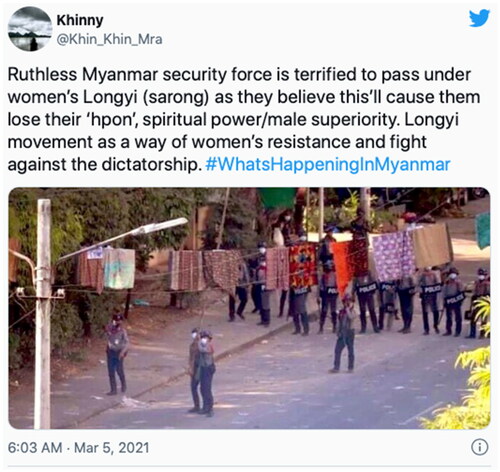

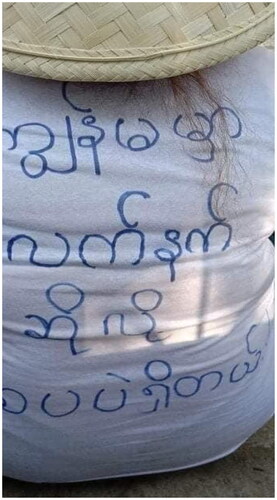

The 2021 Htamein movement highlighted not only the weakness, but also the inherent instability, of the patriarchal belief system underpinning the military regime. Male soldiers clearing the streets of these symbols were afraid to walk under them or touch them. In one often-shared photo on social media, a soldier is shown gingerly reaching out with a bamboo stick, trying to remove a htamein before the rest of the regiment can proceed down the street (). A woman quoted in a news article on the htamein protests explained that “[w]e have no weapons to harm them [police and soldiers], but anything that worries or delays them is our weapon” (Frontier Myanmar, February 16, 2021). As one woman succinctly wrote on her T-shirt: “I only have a vagina as a weapon” ().

Figure 5. The police force trying to take down htamein.

Source: Public post by Khinny @Khin_Khin_Mra. https://twitter.com/Khin_Khin_Mra/status/1367702244368338949/photo/1.

Figure 6. Woman protestor’s T-shirt: “I only have a vagina as a weapon.”

Source: Public post from Facebook account, now unavailable.

Seeing the success of this campaign, young anti-coup protestors proceeded to exploit this weakness by centring women’s bodies in the protest movement and into the public spaces. With the rise of the htamein as a symbol of resistance, a group of young women activists launched a nationwide htamein movement on March 8, 2021, International Women’s Day. Their slogans were, “fly the htamein flag, and end the dictatorship” and “our htamein, our flag, our victory” (Khin Khin Mra Citation2021). The night before the women’s national campaign was scheduled to take place, the State Administrative Council passed an emergency decree declaring illegal the hanging of htamein on the street. However, protesters ignored this, and htamein were hung out on streets across Myanmar. The day after the protests, the state-run newspaper The Global New Light of Myanmar (March 9, 2021) published a statement condemning the use of htamein and sanitary products:

Authorities has found people hanging women’s clothes and sanitary products on the road while they are protesting in Yangon Region especially in Sanchaung Township on 8 March 2021 and such doings are deliberate acts to disrespect monks and tarnish Sasana [religion]. Authorities will take actions against those who will attempt to tarnish Sasana, according to an announcement released by the police force.

As this quote illustrates, women’s underwear and sanitary products were perceived to disrespect the Buddhist religion, the teachings of the Buddha, as well as the monks who serve the teachings, through which the concept of hpoun has achieved central status in Myanmar state’s ideology.

In his 2021 International Women’s Day Speech, General Min Aung Hlaing urged women to co-operate in the state’s “efforts to protect and promote the rights of women” and reminded his audience of the value of families and community in ensuring equality, positioning women as subjects to be protected and conscientious of their patriotic duties to their amyo (The Global New Light of Myanmar, March 9, 2021).

In running the htamein campaign and mobilising the general population to adopt the htamein as symbol of resistance, protesters targeted the patriarchal nature of the military disrupting both the coup and prevalent beliefs about women’s bodies and status (Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi Citation2017, Citation2019). One of the organisers of the htamein campaign, Nant May – a pseudonym – explained (Interview, September 2022):

We would like to upset the normalised roles of women in our society and restrictions put on us. As we are young revolutionaries, fighting this revolutionary war to achieve a new inclusive state and future, we thought it is critical to emphasise women’s participation in this struggle and we need to promote women’s participation in this. We need a new paradigm shift towards gender ideology for this.

In other words, Nant May is emphasising that beliefs about menstruation, linked to ideas about women’s bodies being potentially polluting, transgressive, and inferior, as well as informing private, daily practices are central to military logic. The protestors leveraged this logic for powerful subversive action. Even some young men wrapped htamein around their bodies and/or heads to challenge the authority of the military.

In writing of Irish republican women, O’Keefe (Citation2006, 551) argues that the use of menstrual blood as a form of protest “transgressed gender norms in the most scrupulous of ways.” Yet, in Myanmar, not everyone was comfortable with this approach and critiqued it for bringing misfortune. Some parents worried that their sons participating in the protests may face bad luck as they went under the htamein. Even some male protestors, who themselves arranged htamein barricades, avoided passing under them, finding it hard to separate themselves from this belief system, internalised since childhood, about women’s polluting potential. In some cases, male protestors purposefully chose the new htamein to wear on their heads which demonstrated a tension between their symbolic support for htamein movement but also their belief in social norms. Thus, people’s participation in the protests revealed but did not necessarily resolve the patriarchal beliefs underpinning and facilitating decades of military power, and while the protest movement offered multiple subjectivities for contestation, it also generated tension, even amongst those supposedly wanting to oppose and change military rule and gendered norms.

Embodiment and Violence

Within a month of the coup, the military began a violent crackdown on the protests. A young woman, Mya Thwe Thwe Khaing, was the first protester to die after being shot in the head by military snipers (BBC, February 19, 2021). Thousands of women were arrested. Yet they would not be stopped. A poem by Aung Way dedicated to Zue Wint War, a 15-year-old student protestor shot in March 2021, highlights this determination:

Our history is

In the stream of blood

The love rose of our time

Must revitalise with new blood

Little beloved daughter Zue Wint War fought the battle

By hanging her last will

Around her neck

The Spring

Will never forget the Hero (AAPPB Citation2022, 15).

The intimidation, insecurity, abuse, and murder of women such as Zue Wint War, Mya Thwe Thwe Khaing, and other women can be understood in relation to widespread patriarchal norms, in which women’s behaviour and sexuality must be controlled. Once the crackdown began and the prisons filled with activists, these notions also shaped women’s experiences of imprisonment. Although protestors from a variety of backgrounds were subject to sexual and gender-based violence, transgender women were particularly targeted, abused, humiliated, and ridiculed by the security forces in specifically gendered ways: unable to reproduce “racially pure” subjects, they were perceived by their interrogators to upset hpoun. In the aftermath of the coup, reports emerged of incarcerated transwomen forced to wear male clothing and taunted with explicitly sexual slurs (Radio Free Asia, June 29, 2021). As National Unity Government Minister of Human Rights Aung Myo Min put it: “They hated to see a man dressed like a woman, and when they see people like this, they not only arrest them, but harass them sexually” (cited in Radio Free Asia, June 29, 2021). A transwoman detained remembered being told while being beaten: “You queers are so useless … aren’t you a man?” (cited in Radio Free Asia, June 29, 2021). Although transgender individuals were generally housed in prison cells according to their gender identity before the coup, there was a reversal after the coup, with transgender people placed in cells opposite to their gender identity (Conflict-Related Sexual Violence Citation2021). A gender specialist explained that the “[m]ilitary is masculine and it is toxic to LGBTIQA and they feel allergic to LGBTIQA. Transwomen were more targeted as they did not behave like men” (Interview, November 2022). This follows decades of similar practises enacted against members of the queer community, with security forces committing verbal, sexual, and physical abuses (Chua and Gilbert Citation2015; UN FFM 2019). After the coup, simply being trans triggered further abuse and violence, because in coupling the body and reproduction with ideas of national belonging and security, transwomen were produced as subjects that were both outside the gender order and threatening to it. In rejecting hpoun, they subverted ideas of male superiority (Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi Citation2012). Like women marrying or having relations outside the “national race,” (Cheesman Citation2017) transwomen posed a danger to the gender order, dependent as it was on the idea of women being put into the service of nation building through childbirth. Indeed, during the protests, female prisoners caught with intimate photos on their phones of foreign men (or men considered to look “Muslim”) received additional punishments for “diluting the blood.” In other words, explicitly gendered and racialised narratives of bodies, sexuality, and reproduction constituted key sites through which the military articulated its power and exerted, or attempted to exert, control over the resistance (see Frydenlund and Shunn Lei 2022). For instance, a young woman detained by the military recounted overhearing the interrogation of another young activist:

When they interrogated her, they asked her if she had a boyfriend. The policemen always asked irrelevant personal questions. The girl answered yes and said that her boyfriend was among the male detainees. They said that if she had a boyfriend at such a young age that her parents should be made aware of it. Then they asked about her boyfriend’s ethnicity. She answered that her boyfriend was a Muslim. Then, the interrogator became furious. They asked her if she wanted to be a kalar’s [derogatory term for Muslims] wife, then they asked two other police officers to blindfold her and take her to the room to be tortured (cited in Radio Free Asia, April 22, 2021).

For decades, the military have used rape and torture as a tactic of war, especially against ethnic minority women, including Rohingya and Muslim women. Through instances of rape and violence, their military logic of being the protectors of the Bamar Buddhist nation is paradoxically justified: in protecting the nation against foreign elements and invaders, including guarding against the “dilution of blood” through policing marriages and childbirths, military rule has been legitimised. In this context, gendered and racialised hierarchies are produced, in which women are expected to remain – along with their htamein – “lower than” men in political and public life.

While outside prison walls menstruation was effectively used as a protest tool for humiliating the military and challenging patriarchal control, within the prisons it became a means for humiliating and punishing female activists. There was a lack of adequate toilets (with running water and privacy), and insufficient menstrual hygiene supplies, including sanitary pads. Female prisoners had to menstruate in their clothing (Manny Maung Citation2021). Some female detainees were reportedly forced (or chose) to take contraceptive pills to stop menstruation, which led to further stigmatisation as unmarried women who take contraceptives may be branded as deviant or loose women.

The above examples shed light on the intricate nature of beliefs surrounding the htamein, as well as the multifaceted role of menstruation in challenging societal perceptions of women's bodies. An elderly woman explained that the upper part of a mother’s htamein, known as a htet sain, is also used as a lucky charm by many men and women. She stated, “if you use the small upper part of htamein it may also protect you.” She believed that a soldier who carries the upper part of his mother’s htamein when he goes to battle would not be injured (Interview, November 2022). However, just as the htamein is widely perceived as harmful to men’s hpoun and luck, people believe that if a soldier walks under a htamein, then bullets will hit him. Similarly, menstruation, far from being a private affair, has been used both to fortify and fragment the gendered social norms espoused by the military state: inside the prison, menstruation was used to discipline and control women’s actions and bodies, while on the outside, women (and men) deployed it to destabilise state control over gendered bodies, and by extension, the protests.

From Disciplined Bodies to Resistant Bodies

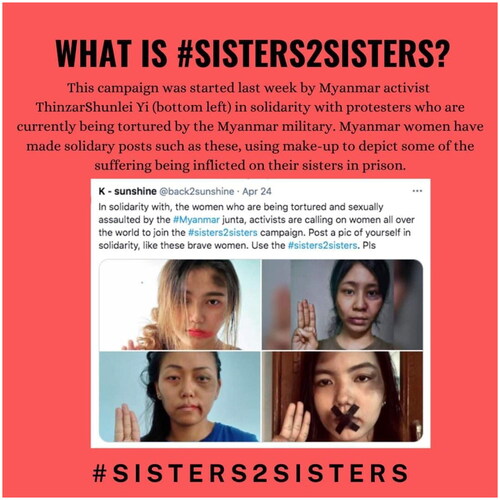

In response to widespread state repression and violence, the protests moved online, with young women developing a campaign called “Sisters2Sisters” as a form of digital activism, showing solidarity with protestors and prisoners experiencing violence (also see Prasse-Freeman Citation2023, 82). The campaign aimed to raise awareness about the military’s use of excessive force, including sexual violence, perpetrated against women. Female protestors were groped and harassed by security forces and many experienced sexual harassment and assaults by police and military personnel during interrogation and detention (Al Jazeera, April 25, 2021; Democratic Voice of Burma, May 7, 2021). In the online campaign, women painted their faces bloodied and bruised, and displayed their photos on social media. Women activists refused to accept the narrative of women’s bodies as sites of insecurity and violence; instead, their bodies became sites of refusal and change (see ).

Figure 7. Sisters2Sisters campaign.

Source: Public post by public organisation Sisters2Sisters @sis2sisMM Twitter page.

All these movements drew attention from the Ministry of Women, Youth, and Children Affairs of the National Unity Government. The Ministry of Women, Youth, and Children Affairs released its first statement on April 29, 2021, condemning the military for perpetrating sexual violence against female protestors and detainees and called for international actors to act on this issue after reports of young detained girls being subject to brutal violence and sexual assaults at interrogation centres. The campaign to “end sexual violence in conflict” was launched by the Ministry of Women, Youth, and Children Affairs to coincide with the International Day for the Elimination of Sexual Violence in Conflict on June 19, 2021, in order to raise awareness of conflict-related sexual violence committed by the military (Ministry of Women, Youth and Children Affairs Citation2021).

Sisters2Sisters capitalised on this by launching another initiative to join the June 19 campaign, called “red lips speak truth to power.” In one poster they campaign against the misogynist military (see ). On June 19, numerous women engaged in digital activism by taking part in an online campaign in which activists painted their lips red and raised three fingers in protest (). The decision to participate in the online campaign positioned women, who may have remained anonymous, solidly in the public sphere. Notably, social media was used both by the military’s supporters and its opponents to harass and threaten women. Both types of users deployed sexual slurs and explicit photos and cartoons in their efforts to silence women. A report by Myanmar Witness notes that online abuse against women was up to five times more prevalent in the initial weeks following the coup, with abuse especially targeted towards ethnic minority women, women seen as being supportive of Muslim groups, and women perceived to be queer (Myanmar Witness Citation2023). This targeting highlights how contestations over gender norms and roles figured prominently in the revolutionary struggle.

Figure 8. Lipstick Campaign.

Source: Public post by public organisation Sisters2Sisters @sis2sisMM Twitter page.

Figure 9. A woman participating in the Lipstick Campaign.

Source: Public post by public organisation Sisters2Sisters @sis2sisMM Twitter page.

However, this gendered logic worked the other way as well, with protestors targeting military supporters and the military itself with derogatory sexual slurs and harassment. depicts a soldier as a transwoman, rebuking the protestors for their “harsh behaviour” or “bold actions.” shows the military spokesman in drag, referring to a female sex worker from a famous film. Likewise, revenge pornography and intimate photos, both real and fake, have also been used by member of the resistance to shame women seen to sympathise with the military (The Diplomat, August 9, 2021).

Thus, although most abusive posts were directed towards women involved in the anti-coup movement, the resistance movement has also deployed ideas about traditional gender roles – based on ideas of women’s responsibilities towards their amyo – to further revolutionary goals. In this way, while the exclusion and violence of the dominant gender order were used in creative ways to upset hierarchies, at the same time they were accompanied by an attachment to gendered subjectivities that also produced exclusion and violence. In other words, gendered norms were both reinforced and upset by using gendered slurs and superstitions in campaigns and protests. This further highlights the complexity of the movement – both seeking to empower women, but also, at times, deploying gendered tactics of shame.Footnote6

Conclusion

Military rule in Myanmar – past and present – has reinforced male-dominated power structures, obstructed women’s political leadership and prevented feminist action in support of transformative change (see Khin Khin Mra and Livingstone, Citation2020). Now, in opposition to these ideas, norms, and structures that women from diverse areas of Myanmar have found common ground. For many women, the protest movement is not just a fight against the military coup but a revolution aiming to upset prevailing patriarchal gender norms. Despite threats to their lives, women from all walks of life have been opposing the military dictatorship and participating in different forms of protest, acting both as frontline protestors and as activists on social media, openly and importantly calling for a change in gendered norms, but also for the abolition of the 2008 Constitution and a recognition of ethnic nationalities’ demands, rights, and histories. As such, women have come together in the face of one adversary and in pursuit of one common goal: resisting the return to a deeply patriarchal military rule.

As Marks and Chenoweth (Citation2020) show, revolutions are implicated in broader gendered relations of power that not only dictate revolutionary movements but revolutionary outcomes. Women’s involvement in the protests, and the violent responses this has engendered, must therefore be understood in relation to the long legacy of military rule, and the specific gendered and racialised hierarchies it has enabled. In this context, women’s bodies constitute both the subject of resistance, aiming to challenge gendered logics, as well as the material object of protest – whether in the virtual or the physical sphere. Here, the use of hitherto “hidden” feminised objects such as htamein, bras, and sanitary pads has been particularly successful in ridiculing and upsetting patriarchal military logic, while online campaigns have succeeded in locating the female/intimate body as a site of resistance, rather than sites of control and discipline in the face of violent military crackdowns.

In light of Parkins’ (Citation2000, 73) argument that embodied protests gain meaning in specific gendered and cultural contexts, this article has shown how women’s protests strategies in the Myanmar Spring Revolution have been articulated in relation to a prevailing military gender order that understands female bodies – and their assumed functions – as both domestic and sexual, and fertile and dirty. This gender order has been experienced in everyday lives and through bodies, reaching into households demarcating between male and female clothing, and encouraging women to hide their menstrual objects from public view. It is then only fitting that resistance to this order is also articulated and experienced through activities that foreground bodies and their everyday intimate relations and reproductions, propelling these into the public sphere, in creative and disruptive ways. Women’s involvement in the Spring Revolution thus has consequences far beyond the immediacy of this particular revolution and the present moment in Myanmar. It has the potential to rewrite the hegemonic gendered norms through which the military realises and legitimises its power.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to Justice Chambers for generous feedback and support; Helene Maria Kyed and anonymous reviewers, who commented so helpfully on earlier versions of this article; Nick Cheesman (and Justine) for the invitation to and organisation of the Special Issue workshop; Kevin Hewison; and most importantly, the brave women actively resisting the Myanmar junta. This study has received ethics approval from the Swedish Ethical Review Agency (Dnr 2022-01410-02).

Disclosure Statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For an example of dance performance, see Latt Thone Chaung (Citation2021).

2 This article uses the term “Myanmar Spring Revolution” which is widely used by people of Myanmar who are continuously fighting for democracy, to refer to a loose collective of anti-coup protests right after the 2021 military coup. While different forms of protests continued to happen, this article focuses specifically on those in the aftermath of the coup from February to June 2021. Some women protestors have carried on their anti-coup movement by joining People’s Defense Forces (see Medail and Chit Thet Tun 2024), the National Unity Consultative Council, the National Unity Government or other forms of resistance. These are beyond the focus of this study. The National Unity Government is a Myanmar government-in-exile formed by the Committee Representing Pyidaungsu Hluttaw, a group of elected lawmakers and members of parliament ousted by the coup.

3 The Panty Protest, also known as the Panties for Peace campaign and Sarong Revolution asked women to send their underwear to the Myanmar generals via international embassies and fly their htamien (women’s skirts) ahead of the 2008 referendum. Women were also encouraged to send their underwear to the then head of the military junta, General Than Shwe, as a way of mocking the military and its gendered rules and superstitions. For some information on this campaign, in which Jenny Hedström participated, see Lanna Action for Burma (n.Citationd.).

4 Khin Khin Mra was a participant and observer in several of the protests reported in this article.

5 While this was certainly intended as a law to control women’s bodies, many women used the law to prosecute cheating husbands, illustrating how the very actors instituting these changes in policies and institutions are not able to necessarily “manage” their effects (see McKay and Khin Chit Win 2018).

6 Thanks to Justine Chambers for this phrase.

References

- AAPPB. 2022. “Power in Spring Revolution.” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners. Accessed July 10, 2022. https://aappb.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/02/English-Women-Fallen-5.pdf.

- AAPPB. 2023. “Daily Briefing in Relation to the Military Coup.” Assistance Association for Political Prisoners, February 7. Accessed February 7, 2023. https://aappb.org/?p=24147.

- Agatha Ma and K. Kusakabe. 2015. “Gender Analysis of Fear and Mobility in the Context of Ethnic Conflict in Kayah State, Myanmar.” Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 36 (3): 1–15.

- AGIPP. 2017. “Analysis of Myanmar’s Second Union Peace Conference – 21st Century Panglong from a Gender Perspective.” Alliance for Gender Inclusion in the Peace Process. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.agipp.org/sites/agipp.org/files/agipp_upc_analysis_paper.pdf.

- Amnesty International. 2015. “Myanmar: Scrap ‘Race and Religion Laws’ that Could Fuel Discrimination and Violence.” Accessed March 12, 2022. https://www.amnesty.org/en/latest/news/2015/03/myanmar-race-and-religion-laws/.

- Belak, B. 2002. Gathering Strength: Women from Burma on Their Rights. Chiang Mai: Images Asia.

- BSPP. 1966. “Party Seminar.” Rangoon: Burma Socialist Programme Party Headquarters.

- Ceyrac, H. 2019. “Ending the Stigma: How to Start a Menstrual Health Revolution in Myanmar.” Fair Planet. Accessed August 15, 2022. https://www.fairplanet.org/op-ed/ending-the-stigma-how-to-start-a-menstrual-health-revolution-in-myanmar/.

- Chambers, J., and N. Cheesman. 2024. “Introduction: Revolution and Solidarity in Myanmar.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 54 (5). doi: 10.1080/00472336.2024.2371976.

- Cheesman, N. 2017. “How in Myanmar “National Races” Came to Surpass Citizenship and Exclude Rohingya.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 47 (3): 461–483.

- Chua, L., and D. Gilbert. 2015. “Sexual Orientation and Gender Identity Minorities in Transition: LGBT Rights and Activism in Myanmar.” Human Rights Quarterly 37 (1): 1–28.

- Crouch, M., and T. Lindsey. 2014. “Introduction: Myanmar, Law Reform and Asian Legal Studies.” In Law, Society and Transition in Myanmar, edited by M. Crouch and T. Lindsey, 117–140, London: Hart Publishing.

- Conflict-Related Sexual Violence. 2021. “CRSV 2021 Trends.” Trends Analysis: Conflict-Related Sexual Violence in Myanmar, Biannual assessment, Edition 1/2021 (1 February to 30 June), disseminated: August 2021.

- Eileraas, K. 2014. “Sex(t)ing Revolution, Femen-izing the Public Square: Aliaa Magda Elmahdy, Nude Protest, and Transnational Feminist Body Politics.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 40 (1): 40–52.

- El Said, M., L. Meari, and N. Pratt. 2015. “Introduction: Rethinking Gender in Revolutions and Resistance in the Arab World.” In Rethinking Gender in Revolutions and Resistance: Lessons from the Arab World, edited by M. El Said, L. Meari, and N. Pratt, 1–32. London: Zed Books.

- Frydenlund, S., and Shunn Lei. 2021. “Hawkers and Hijabi Cyberspace: Muslim Women's Labor Subjectivities in Yangon.” Independent Journal of Burmese Scholarship 1: 282–318.

- Gaikwad, N. 2009. “Revolting Bodies, Hysterical State: Women Protesting the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (1958).” Contemporary South Asia 17 (3): 299–311.

- Harriden, J. 2012. The Authority of Influence: Women and Power in Burmese History. Copenhagen: NIAS Press.

- Hedström, J. 2016. “We Did Not Realize about the Gender Issues. So, We Thought It Was a Good Idea: Gender Roles in Burmese Oppositional Struggles.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 18 (1): 61–79.

- Ikeya, C. 2011. Refiguring Women, Colonialism, and Modernity in Burma. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- Jayawardena, J. 2016. Feminism and Nationalism in the Third World. London: Verso.

- Jordt, I, Tharaphi Than, and Sue Ye Lin. 2021. “How Generation Z Galvanized a Revolutionary Movement against Myanmar’s 2021 Military Coup.” Singapore: ISEAS – Yusof Ishak Institute, Trends in Southeast Asia.

- Khin Khin Mra. 2021. “Women Fight the Dual Evils of Dictatorship and Patriarchal Norms in Myanmar.” New Mandala. March 15. Accessed January 9, 2023. https://www.newmandala.org/women-in-the-fight-against-the-dual-evils-of-dictatorship-and-patriarchal-norms-in-myanmar/.

- Khin Khin Mra, and D. Livingstone. 2020. “The Winding Path to Gender Equality in Myanmar.” In Living with Myanmar, edited by J. Chambers., C. Galloway, and J. Liljeblad, 243–264. Singapore: ISEAS Publishing.

- Lanna Action for Burma. n.d. “Sarong Revolution.” Lanna Action for Burma website. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://lannaactionforburma.blogspot.com/search/label/Actions.

- Latt Thone Chaung. 2021. “They Don't Care About Us (Myanmar Dance Protest).” YouTube. Accessed February 29, 2024. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=9yjOq3eIloU.

- Lau, J. 2021. “Myanmar’s Women Are on the Front Lines Against the Junta.” Foreign Policy, March 12. Accessed March 12, 2021. https://foreignpolicy.com/2021/03/12/myanmar-women-protest-junta-patriarchy-feminism/.

- Loong, S. 2022. “Post-Coup Myanmar in Six Warscapes.” International Institute for Strategic Studies Myanmar Conflict Map. Accessed December 30, 2022. https://myanmar.iiss.org/analysis/introduction.

- Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi. 2012. “In Pursuit of Power: Political Power and Gender Relations in New Order Burma/Myanmar.” Unpublished PhD thesis, Australia National University, Canberra.

- Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi. 2017. “Gender.” In Routledge Handbook of Contemporary Myanmar, edited by A. Simpson, N. Farrelly, and I. Holliday, 381–392. London: Routledge.

- Ma Khin Mar Mar Kyi. 2019. “Book Review.” Anthropos 113: 743–744.

- MacKenzie, M., and A. Foster. 2017. “Masculinity Nostalgia: How War and Occupation Inspire a Yearning for Gender Order.” Security Dialogue 48 (3): 206–223.

- Marks, Z., and E. Chenoweth. 2020. “Women, Peace and Security: Women’s Participation for Peaceful Change.” Stockholm: Folke Bernadotte Academy, PRIO, and UN Women New Insights on Women, Peace and Security (WPS) for the Next Decade Research Brief.

- Marlar, J., and E. Chambers. 2023. “Our Htamein, Our Flag, Our Victory: The Role of Young Women in Myanmar’s Spring Revolution.” Journal of Burma Studies 27 (1): 65–99.

- Manny Maung. 2021. “Rights of Women Violated in Myanmar Prisons: Few Toilets, No Menstrual Hygiene Supplies.” Human Rights Watch Dispatch June 8. Accessed February 2, 2023. https://www.hrw.org/news/2021/06/08/rights-women-violated-myanmar-prisons.

- Mi Mi Khaing. 1984. The World of Burmese Women. London: Zed Books.

- Ministry of Women, Youth and Children Affairs. 2021. Facebook, June 13. Accessed April 6, 2024. https://www.facebook.com/mowyca.

- Min Zin 2001. “The Power of Hpoun.” The Irrawaddy 9: 1–4. Accessed October 10, 2022. https://www2.irrawaddy.com/article.php?art_id=2471&page=1.

- Moghadam, V. 1997. “Gender and Revolutions.” In Theorizing Revolutions, edited by J. Foran, 137–167. London: Routledge.

- Myanmar Witness. 2023. “Digital Battlegrounds.” Myanmar Witness Report. January 25. Accessed February 3, 2023. https://www.myanmarwitness.org/reports/digital-battlegrounds.

- O’Keefe, T. 2006. “Menstrual Blood as a Weapon of Resistance.” International Feminist Journal of Politics 8 (4): 535–556.

- Parkins, W. 2000. “Protesting like a Girl.” Feminist Theory 1 (1): 59–78.

- Pedersen, M. 2011. “The Politics of Burma's ‘Democratic’ Transition: Prospects for Change and Options for Democrats.” Critical Asian Studies 43 (1): 49–68.

- Phyo Win Latt. 2020. “Protecting Amyo: The Rise of Xenophobic Nationalism in Colonial Burma, 1906–1941.” Unpublished PhD thesis, National University of Singapore.

- Prasse-Freeman, E. 2023. Rights Refused: Grassroots Activism and State Violence in Myanmar. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Saha, J. 2022. “Racial Capitalism and Peasant Insurgency in Colonial Myanmar.” History Workshop Journal 94: 42–60.

- Sasson-Levy, O., and T. Rapoport. 2003. “Body, Gender and Knowledge in Protest Movements: The Israeli Case.” Gender & Society 17 (3): 379–403.

- Shwe Shwe Sein Latt, K. Ninh, Mi Ki Kyaw Myint, and S. Lee. 2017. Women’s Political Participation in Myanmar: Experiences of Women Parliamentarians. Yangon: The Asia Foundation.

- Skidmore, M. 2002. “Menstrual Madness: Women’s Health and Well-Being in Urban Burma.” Women and Health 35 (4): 81–99.

- Spiro, M. 1993. “Gender Hierarchy in Burma: Cultural, Social, and Psychological Dimensions.” In Sex and Gender Hierarchies, edited by B. Miller, 316–333. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Sutton, B. 2007. “Naked Protest: Memories of Bodies and Resistance at the World Social Forum.” Journal of International Women’s Studies 8 (3): 139–148.

- Tamale, S. 2017. “Nudity, Protest and the Law in Uganda.” Feminist Africa 22: 52–86.

- Tharaphi Than. 2011. “Understanding Prostitutes and Prostitution in Democratic Burma, 1942–62: State Jewels or Victims of Modernity?” South East Asia Research 19 (3): 537–566.

- Tharaphi Than. 2014. Women in Modern Burma. London: Routledge.

- Turnell, S. 2012. “Myanmar in 2011: Confounding Expectations.” Asian Survey 52 (1): 157–164.

- UN Fact Finding Mission. 2019. “Sexual and Gender-based Violence in Myanmar and the Gendered Impact of its Ethnic Conflicts.” Geneva: UN Human Rights Council Report A/HRC/42/CRP.4/. Accessed October 12, 2021. https://reliefweb.int/report/myanmar/sexual-and-gender-based-violence-myanmar-and-gendered-impact-its-ethnic-conflicts.

- Wahidin, A. 2019. “Menstruation as a Weapon of War: The Politics of the Bleeding Body for Women on Political Protest at Armagh Prison, Northern Ireland.” Prison Journal 99 (1): 112–131.

- Williams, D. 2014. “What’s So Bad about Burma’s 2008 Constitution? A Guide for the Perplexed.” In Law, Society and Transition in Myanmar, edited by M. Crouch and T. Lindsey, 117–140. London: Hart Publishing.

- Women’s League of Burma. 2011. The Founding and Development of the Women’s League of Burma: A Herstory. Chiang Mai: WLB.

- Women’s League of Burma. 2021. “Situation Update: May 2021.” Chiang Mai: WLB. Accessed February 10, 2023. http://www.womenofburma.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/May%20Situation%20Update%20%5BEng%5D.pdf.

- Yuval-Davis, N. 1995. Gender and Nation. London: Sage.

- Young, I. 2003. “The Logic of Masculinist Protection: Reflections on the Current Security State.” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 29 (1): 1–25.