ABSTRACT

Video research methods provide a powerful yet accessible way for researchers to observe and theorize entrepreneurial phenomena by analyzing entrepreneurship “in motion.” Despite the growing uptake of video data in entrepreneurship research, there is no available overview or analysis of current uses of video research methods, which makes it difficult for interested researchers to grasp its value and possibilities. Our systematic review of 142 entrepreneurship research articles published in leading journals reveals three dominant video research methods: (a) videography of entrepreneurship “in the wild” (such as pitching and other naturally occurring practices); (b) video content analysis using entrepreneur-generated videos (such as crowdfunding and archival videos); and (c) video elicitation in “manufactured” contexts (such as interviews and focus groups, experiments and interventions). Building on these studies, we put forward a research agenda for video-based entrepreneurship research that capitalizes on the unique affordances of video to understand the interactional, embodied, material, and emotional nature of entrepreneurial practice.

Introduction

For the field of entrepreneurship research to stay relevant, there is a need to move toward more transformational research and novelty in theorizing and methods (Shepherd, Citation2015). Entrepreneurial action is now widely viewed as a future oriented, interactive, material, emotional, nonlinear, and contextual process under conditions of uncertainty (Hindle, Citation2004; Karatas-Ozkan et al., Citation2014; Neergaard & Ulhøi, Citation2007; Suddaby et al., Citation2015). However, a number of scholars have pointed out that dominant methods, such as surveys, interviews, experiments, and secondary data provide only limited insight into entrepreneurial action as it happens (Dana & Dana, Citation2007; Zahra & Wright, Citation2011). There have been growing calls to further entrepreneurship research by observing (and participating with) entrepreneurial practitioners “in action” within their social, economic, and environmental contexts (Chalmers & Shaw, Citation2017; Hjorth et al., Citation2015; Sklaveniti & Steyaert, Citation2020; Thompson et al., Citation2020). This demands an expansion of the methodological tools used to observe and examine overlooked aspects of entrepreneurial action (Berglund, Citation2007; Hindle, Citation2004; Shepherd & Suddaby, Citation2017). In this article, we argue that video-based methods provide a powerful yet accessible way for researchers to observe and theorize the contextual, interactional, material, and emotional aspects of entrepreneurial action (Christianson, Citation2018).

Over the past few years, a growing number of entrepreneurship scholars have adopted various video research methods in their research designs. Broadly speaking, video research methods incorporate the collection, creation, or curation of video clips, drawing on positivist or interpretivist methodologies. Clarke (Citation2011) and Thompson and Illes (Citation2020), for example, demonstrate that video-based methods enable researchers to observe and abductively theorize the embodied (such as use of nonverbal communication) and relational (such as conversational turn-taking) aspects of entrepreneurial learning and persuasion. On the other hand, video-based methods also provide researchers novel sources of archival and crowdfunding data to understand entrepreneurial outcomes and have even been used in deductive experimental studies. For example, Shane et al. (Citation2019) examine the effect of founder passion on the decision-making of informal investors by using videos to elicit responses by treatment and control groups of informal investors, which are subsequently measured by both surveys and fMRI technology. Given these important recent developments, it is clear that many new opportunities have emerged for using video-based methods in entrepreneurship research.

Although video research methods have gained a foothold in entrepreneurship studies, there are currently no articles that provide an overview or clearly delineate the value of video research methods for addressing novel entrepreneurship research topics. This has led to little dialogue among entrepreneurship researchers about the value and procedures of video research methods, which is particularly important given the unique challenges of entrepreneurship as a research context. Indeed, designing and implementing video methods in research designs is far from trivial because of the uncertainty, heterogeneity, and disequilibrium in entrepreneurial phenomena, as well as the practical research skills necessary to shoot, handle, and analyze video data. Many entrepreneurship researchers, editors, and reviewers alike may be unfamiliar with the use of video methods in research designs, and conventional journal formats often create challenges for displaying video data (Christianson, Citation2018; LeBaron et al., Citation2018). A lack of reflexive examination means the methodological differences underpinning the use of video data remain unclear, which limits awareness of the full possibilities of video research methods in the field. Consequently, we ask “What are the current ways in which video is being used in entrepreneurship research, to what extent is video data utilized in research designs, and what are the potentials of video methods to further our understanding of entrepreneurial action?”

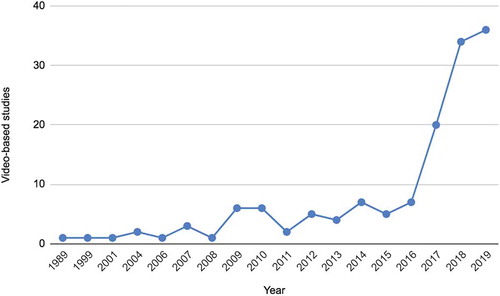

We address this question by taking stock of video research methods in entrepreneurship articles published in leading journals. We systematically reviewed 142 empirical entrepreneurship research articles in 41 prominent management, organization, and entrepreneurship journals that use video methods in their research design. A thematic analysis revealed three main video research methods in empirical entrepreneurship articles: (a) videography of entrepreneurship “in the wild” (such as pitching and other naturally occurring practices); (b) video content analysis of entrepreneur-generated videos (such as crowdfunding and archival videos); and (c) video elicitation in “manufactured” contexts (such as interviews and focus groups, experiments and interventions). We found a steady rise in entrepreneurship research using video research methods (24 articles from 2010–2014 to 102 from 2015 to the present), driven by the increasing use of video content analysis of crowdfunding and archival videos. Delving deeper into each method, we unpack the different methodologies (inductive/deductive), key exemplars (extensive use of video data), benefits, and limitations. Building on this review, we then develop a research agenda for video-based research to further entrepreneurship scholarship by providing a novel insight into the interactional, embodied, emotional, and material aspects of entrepreneurial action.

This article contributes to entrepreneurship research in two main ways. First, we bring coherence to and appraise existing entrepreneurship research that uses video research methods in empirical studies for the first time. Our literature analysis reveals that researchers have leaned heavily on video elicitation and video content analysis in experimental and case study research, but in many of these studies, video data take a secondary role in analyses. Moreover, we establish that few scholars venture into the enormous possibilities of using videography to observe naturally occurring practices of entrepreneurship as they happen in context. Second, we develop a research agenda that explains how the unique audio, visual, and timing affordances of video can be further utilized to systematically analyze the interactional, embodied, emotional, and material aspects of entrepreneurial action (Christianson, Citation2018). We thus specifically address growing calls for new qualitative research methods that can further entrepreneurship research by discussing the ways in which video uniquely renders visible the practices of entrepreneurship for further analysis, while taking into account their embeddedness in various social, economic, and environmental contexts (Karatas-Ozkan et al., Citation2014).

Setting the scene—The value of video for entrepreneurship research

Entrepreneurship research has traditionally been founded upon aims to develop explanatory theories based on the measurement, isolation, and relation among variables and constructs (Hjorth et al., Citation2015). The field of entrepreneurship has therefore been dominated by methodological approaches, such as surveys, experiments, and secondary data, that search for and measure stable relationships between concepts in attempts to discover the generic and distinct features of entrepreneurial action (Dana & Dana, Citation2007; Moroz & Hindle, Citation2012; Zahra & Wright, Citation2011). A growing number of scholars alternatively argue that entrepreneurial action is fundamentally future oriented, relational, emotional, embodied, nonlinear and contextual, and conducted under conditions of uncertainty (Hindle, Citation2004; Karatas-Ozkan et al., Citation2014; Neergaard & Ulhøi, Citation2007; Suddaby et al., Citation2015). This perspective encourages an empirical focus on the interactive, embodied, emotional, and material aspects of entrepreneurial action (Barinaga, Citation2017; Johannisson, Citation2011; Tatli et al., Citation2014).

To understand these aspects, scholars have increasingly turned their attention to “episodes of situated social interaction” (Campbell, Citation2019; Chalmers & Shaw, Citation2017) to address questions of how and why entrepreneurial practitioners accomplish mundane—though significant—practices, such as pitching, networking, and resourcing (Drakopoulou Dodd et al., Citation2018; Keating et al., Citation2013; McKeever et al., Citation2014; Thompson et al., Citation2020). This has led researchers to focus on the ways in which entrepreneurs use their bodies in interaction (Clarke & Cornelissen, Citation2011) and how emotions arise and may influence interactional outcomes (Cardon et al., Citation2017). Moreover, recent studies argue that entrepreneurs pursue their aims using objects, artifacts, and technologies (Holt, Citation2008; Korsgaard, Citation2011); thus materiality is not a background element but the very means through which entrepreneurs collaborate and conduct their practical activities. As a consequence, more researchers are turning toward novel qualitative methods that can observe the lived experience of entrepreneurial action and, more specifically, their interactional, embodied, emotional, and material properties as they occur in real time (Hindle, Citation2004; Karatas-Ozkan et al., Citation2014; Neergaard & Ulhøi, Citation2007; Suddaby et al., Citation2015).

There are a number of methodological challenges to this form of entrepreneurship research. One main challenge is that entrepreneurs themselves are often not fully aware of the interactional, affective, embodied, and material aspects of unfolding entrepreneurial action as they happen; thus surveys and interviews have natural limits in producing new insights. Similarly, entrepreneurship occurring in real time often happens too quickly to capture using ethnographic note taking, which limits later analysis. Finally, research on entrepreneurial practices in situ often depends on the researcher’s memory from field experiences, which may reduce the reliability of findings by limiting the sharing of observations and at worst, enabling post hoc interpretations that are not faithful to the situation. To advance research on entrepreneurial action, new methods are needed that enable researchers to carefully reveal and examine the variety of entrepreneurial practices, their constitutive properties, and how they are enacted to organize new ventures under conditions of uncertainty.

To address these challenges, video research methods have a number of distinct advantages for entrepreneurship research. First, video recordings provide a permanent record of events and interactions (LeBaron et al., Citation2018) while rendering the fast pace of entrepreneurship amenable for repeat analysis by researchers (Gylfe et al., Citation2016). This improves trustworthiness of findings by reducing reliance on the memory and post hoc interpretations by both entrepreneurs and researchers (Smets et al., Citation2014). When combined with other qualitative methods such as observation, interviews, or archival data, video-based methods provide a powerful alternative view of entrepreneurial activity that can confirm, complement, or contrast with what entrepreneurs say they do or what the researchers themselves can see (Gylfe et al., Citation2016). Second, shooting, collecting, storing, and analyzing video has never been more accessible, affordable, reliable, and rigorous, which empowers users to produce more frequent and encompassing videos from different vantage points than possible in previous decades (Christianson, Citation2018). Spurred on by significant cost reductions, advances in video recording technology, and video analytical software (LeBaron et al., Citation2018), a growing number of scholars have leveraged videos to render visible entrepreneurial activity in ways not possible using other methods. Finally, numerous software packages such as V-Note, Transana, and Dedoose have been developed to assist researchers in the careful analysis of videos. This software enables researchers to edit raw video footage, share video fragments via cloud storage platforms, slow down video play, transcribe interactions and talk in situ, and analyze video fragments using multicoder features (Brugman & Kita, Citation1995; Christianson, Citation2018; Koch & Zumbach, Citation2002; LeBaron et al., Citation2018). Accordingly, these unique features allow scholars an ability to study the dynamics of entrepreneurial action that is sensitive to interaction, embodiment, emotion, and materiality—theoretical concepts that remain fundamental to the future of entrepreneurship studies (Chalmers & Shaw, Citation2017; Christianson, Citation2018; Zundel et al., Citation2016).

Despite these benefits, video research methods are varied, which can make it difficult for interested researchers to grasp its value and possibilities. For example, scholars have increasingly acquired video data produced by entrepreneurs for crowdfunding campaigns. At its most reductive, this can be reflected in simple binary coding of whether a video is present or not, which is then used as a predictive factor for campaign success. Contrastingly, videography has been used by ethnographers to observe the minutiae of naturally occurring practices among entrepreneurs and stakeholders, using multimodal analyses (verbal and nonverbal forms of communication) to inductively find “thick description” explanations (Clarke, Citation2011; Thompson & Illes, Citation2020). Scholars have also used video elicitation using paid actors to implement treatment effects in experimental studies with the aim of testing hypotheses (Shane et al., Citation2019). These examples point to different methodological underpinnings that guide researchers (positivism and interpretivism), which adds a layer of complexity to understanding the uses of video research methods. What is more, entrepreneurial phenomena can be difficult to capture using video methods as entrepreneurship is an uncertain enterprise, is empirically very diverse, and often takes place in private spaces. The challenges and varieties of uses of video research methods, hence, are diverse in their assumptions, limitations, and benefits. In the remainder of this study, we aim to bring coherence to the uses of video research methods for entrepreneurship scholars and to highlight further possibilities.

Methods: Reviewing research using video methods in entrepreneurship

Our review focuses on research in leading international journals that publish entrepreneurship studies and use video methods in their research designs. The methodology for our review is guided by Christianson’s (Citation2018) review of video-based research in the organization and management literature. To begin, we identified the top-tier journals using the Academic Journal Guide maintained by the Chartered Association of Business School (ABS), which is recognized by entrepreneurship scholars as a quality list of rankings (Fayolle & Wright, Citation2014). We focused on the leading journals (ranked 3, 4, and 4*) in the fields of “Entrepreneurship and Small Business Management,” “Innovation,” “General Management,” and “Organization Studies.” This resulted in a group of 41 journals that represented entrepreneurship specific journals as well as broader management and organization studies journals. We excluded five journals as they do not publish empirical studies (for example, Academy of Management Annals, International Journal of Management Reviews).

To discover relevant video-based entrepreneurship studies, we searched for the word video* in entrepreneurship specific journals and video* AND entrepreneur* in general management and organization journals that appear anywhere in the full text. This led to an initial list of 1,598 articles identified. To narrow our focus, we manually reviewed the articles and only included articles that were empirical and that used video recordings as part of their methodology. We included studies where video was used to generate other data (for example, using video as stimulus for an experiment), as well as where videos are themselves subject to analysis. These criteria resulted in 142 articles being included in our review. provides an overview of the articles included from each journal. It shows the number of hits in the initial video* (AND *entrepreneur) search and the number of articles that met the inclusion criteria for review, both as an absolute number and classified by analysis type (for example, qualitative, mixed methods, quantitative).

Table 1. Articles by journal and analysis type

We utilized thematic analysis (Boyatzis, Citation1998; Braun & Clarke, Citation2006) to examine the current video methods used in entrepreneurship research. In the first round of analysis we read each article and coded the articles for basic information about the research question, phenomena of interest, theoretical lens, overarching research methodology (for example, grounded theory, ethnography, case study, comparative statistical analysis), and sources of data other than video (for example, interviews, ethnographic field notes, surveys, documents, archival data). We also coded how researchers were using videos in their methodology: description of videos; nature of video; videographer (for example, researcher-, participant-, or third-party-generated); form of data (for example, verbatim transcript, conversation analysis [CA] transcript, direct from video, multimodal); data analysis (for example, gestalt, coding, count); and focus of video analysis (for example, verbal, nonverbal, emotional, interactional, sociomaterial).

In the second round of analysis, we compared the use of video methods in the research designs of these articles and clustered them into six broader themes (naturally occurring pitching practice, naturally occurring other practices, crowdfunding, archival data, video interviews, and experiments and interventions), which we then organized into three main categories (videography of entrepreneurship “in the wild,” video content analysis of entrepreneur-generated videos, and video elicitation in manufactured contexts). shows the spread of articles across the six subcategories over time.

Table 2. Articles by video research method and year range

In the final round of analysis, we reread the articles within each of the six subcategories and identified the common themes in terms of phenomena, types of data, and focus of analysis. As part of this round, we coded articles on whether video data was a necessary element that drove the interpretation of entrepreneurial phenomena. We examined whether video data was a necessary element in the development of the findings. Specifically, we coded each study to understand how the unique timing and visual and audio affordances of video brought decisive information that would not have been possible with any other method. For example, some studies use video-recorded interviews but subsequently converted them into verbal transcripts, thereby losing the timing and visual affordances of video. Similarly, many video content analysis studies included videos as archival documents, yet there is little evidence that video data informed the analysis. Through this process we identified exemplar studies for each form of video method and highlighted the potential of video research to shed new light on entrepreneurship phenomena in the findings section.

Findings: Three video research methods in entrepreneurship research

Our review reveals three main video research methods currently used in entrepreneurship research: (a) videography of entrepreneurship “in the wild” (such as live pitching and other naturally occurring practices), (b) video content analysis of entrepreneur-generated videos (such as crowdfunding and archival videos), and (c) video elicitation in manufactured contexts (such as interviews, focus groups, and experiments and interventions). provides an overview of these three types of video studies categorized into six subtypes.

Table 3. Overview of types of video research methods

As highlighted in , there has been a rapid rise in entrepreneurship research utilizing video methods in recent years. Prior to 2010, only 16 studies of entrepreneurship had involved videos in their methodology. These early studies mainly relied on reviewing archival company produced videos in case analysis (for example, Bradbury & Clair, Citation1999) or creating videotaped interviews or focus groups with entrepreneurs (for example, Hienerth, Citation2006; Buttner, Citation2001). In terms of analysis, most of this early video-based research focused on either on converting video to verbatim transcripts (thus losing visual elements) (for example, Hienerth, Citation2006; Buttner, Citation2001) or reviewing videos as part of a broader interpretive analysis of case (for example, Berger et al., Citation2004).

The first half of the last decade saw a steady rise in entrepreneurship research using video research methods (24 articles from 2010–2014), driven mainly by the increasing use of videos as a form of archival data in single or multiple case study analysis. This time period also saw the first use of videography in entrepreneurship research, with efforts to observe entrepreneurial practice “in the wild” to study everyday practices enacted by entrepreneurs and various stakeholders (for example, Clarke, Citation2011; Cornelissen et al., Citation2012). It has only been in the past five years, however, that video research methods have really expanded in entrepreneurship studies, driven by the accessibility and affordability of quality video recording equipment. We found that 102 articles in leading entrepreneurship, management, and organization journals were published in this time frame, with 90 of these (63 percent of total video articles) published in just the past three years (2017–2019). One explanation of this dramatic rise can be explained by the surge in crowdfunding research, following the publication of the seminal paper by Mollick in 2014. The accessibility of crowdfunding data and its clear performance outcomes has been a boon for positivist video content analysis in entrepreneurship research. Nevertheless, we find that the majority of these studies use a simple binary measure if a video exists or not to predict crowdfunding outcomes, which utilizes very little information from the video data itself.

The majority of entrepreneurship studies using video methods utilized qualitative analysis, with less than a third of studies using solely quantitative analysis. The growing research on crowdfunding was the only domain in which qualitative analysis has not been used, as all 28 studies published to date relied on quantitative analysis. The most common form of video research method was the use of video content analysis of archival videos (44 percent). These predominantly qualitative studies utilized company-generated videos as part of the secondary documents in conducting case study research. However, a closer look at articles using videos as archival data raises doubts about the extent to which these videos were truly part of the research design. Although some studies show clear linkages to how the archival videos were core to the findings and analysis (for example, Yu et al., Citation2013), many studies only make passing reference to the archival videos in the methodology, which leaves the reader uncertain to what degree the videos formed part of the overall understanding of the case. We now delve into each of the three main video research methods.

Videography of entrepreneurship “in the wild”

A small number of researchers are pioneering the use of videography for viewing real-time, naturally occurring entrepreneurial phenomena. By “real-time” and “natural” we mean that researchers shoot or collect video recordings of entrepreneurs and stakeholders as they go about their daily work with limited researcher intervention. The majority of these videos have focused on entrepreneurial pitching, with only a few studies venturing into more everyday entrepreneurial action and interaction (which we return to in the research agenda).

Videography of entrepreneurial pitching

Videography on pitching emphasizes the benefits of focusing in real time on the subtle actions and interactions enacted by entrepreneurs and investors throughout the pitching process (Pollack et al., Citation2012). Early videography on pitching relied heavily on (sometimes edited) footage from popular entrepreneurship reality television programs Shark Tank and Dragons’ Den (for example, Maxwell et al., Citation2011; Maxwell & Lévesque, Citation2014; Pollack et al., Citation2012). Although most of these studies focus on the televised pitch and interactions with judges, some studies utilized novel elements of the program to better understand the practices of pitching, such as the backstories of the participants and interviews with investors (Wheadon & Duval-Couetil, Citation2019). More recent studies have accessed insights from the expanding world of entrepreneurship pitching competitions at the global and local levels, and other studies made use of videos of interactions with investors in Q&A sessions (Cardon et al., Citation2017; Chalmers & Shaw, Citation2017; Kanze et al., Citation2018) and feedback sessions with mentors prior to the pitch (Van Werven et al., Citation2019).

Most videographic studies of pitching focus on coding direct from video to capture the textual, audio, and visual elements. Mixed-methods coding was the most common analysis approach either through: (a) fine-grained qualitative coding frame used to produce quantitative insights, the most common form of analysis (Maxwell et al., Citation2011; Maxwell & Lévesque, Citation2014; Wheadon & Duval-Couetil, Citation2019); or (b) inductive coding of pitching, followed by experiment to understand causality (Chan et al., Citation2019; Clarke et al., Citation2018). Other studies utilized computer-aided analysis through the use of basket of words techniques on transcripts (Kanze et al., Citation2018) or the use of machine learning algorithms to detect emotional displays in facial expressions in videos (Stroe et al., Citation2019). More interpretive-oriented studies engaged in qualitative analytic traditions such as narrative analysis to understand rhetoric (Van Werven et al., Citation2019), ethnographic field notes to capture material and affective experiences (Katila et al., Citation2019), or conversation analysis (Chalmers & Shaw, Citation2017).

Exemplary studies

One influential stream of videographic pitching research focuses on rhetoric, narratives, and emotional displays used by entrepreneurs to legitimize their ventures. Katila et al. (Citation2019) exemplify a fine-grained videographic approach by engaging in a more gestalt analysis of the verbal, nonverbal, material, temporal, spatial, relational, and bodily elements of pitching. The authors’ analysis reveals the cues utilized by the eventual winner to convey openness, trustworthiness, and confidence to the judges. Katila et al. (Citation2019) thus show the value of combining video with ethnographic field notes, as the video recordings of pitches allowed the authors to revisit and reexamine the embodied performances of the entrepreneurial pitching in greater detail than was captured through initial observations. Similarly, Wheadon and Duval-Couetil (Citation2019) tap into the rich emotional, interactional, and sociomaterial elements of videography to reveal how the content and social interactions displayed in the Shark Tank programs create, reinforce, or challenge gender inequalities. Finally, Chalmers and Shaw (Citation2017) illustrate the potential of fine-grained conversation analysis of videos, focusing upon the verbal, nonverbal (for example, facial expressions, nodding), sociomaterial, temporal, and emotional dimensions of entrepreneur-investor interactions.

Limitations

It is common for pitching research to view the relationship between entrepreneurs and investor(s) based upon little more than a financial exchange—a relationship that is easily quantified for purposes of objective study. However, Teague et al. (Citation2020) point out that there may be a variety of forms of pitching practices that are useful in different circumstances, such as gaining feedback or practicing nonverbal communication techniques. Another limitation of current videographic research on pitching is the use of heavily produced and edited videos that moves more toward the realm of video content analysis (which we discuss next). As noted by Wheadon and Duval-Couetil (Citation2019) and Maxwell et al. (Citation2011), reality television shows such as Shark Tank selectively emphasize or downplay certain features to portray entrepreneurs and investors in ways that align with their narrative and stories. Some researchers have taken steps to limit this issue by analyzing unedited pitching footage (for example, Maxwell et al., Citation2011; Maxwell & Lévesque, Citation2014) or contacting the producers of the show and the entrepreneur to verify the “authenticity” of the pitches and interaction portrayed on the show (Pollack et al., Citation2012). Nevertheless, these videos are primarily for entertainment purposes, which results in potentially artificial interactions between entrepreneurs and investors in front of an audience, as investors may be emphasizing certain behaviors in the knowledge that they are being assessed by a televised public.

Videography of other entrepreneurship practices

Just as video-based research on pitching emphasizes real-time behavior, scholars have begun to use videography to understand a broader scope of entrepreneurship practices while keeping focus on the subtle actions and interactions enacted by entrepreneurs and (possible) stakeholders. Many of these studies default toward adopting a positivist methodology of qualitative inquiry, which aims to theorize stable explanations across cases amenable to further quantitative inquiry. For example, Preller et al. (Citation2018) videotaped naturally occurring team strategy meetings to investigate how entrepreneurial visions held by members of founding teams impact the future development of entrepreneurial opportunities. Others adopt interpretivist methodologies that remain contextually rich (Clarke, Citation2011; Cornelissen et al., Citation2012; Thompson & Illes, Citation2020). A main strength of these studies is often a combination of verbal, nonverbal (tone, gestures, facial expressions), relational (interactions among employees, customers, and financiers), and material objects (visual symbols, artifacts). By combining these elements, the authors aim to connect the bodily, material, and discursive components of entrepreneurial practices. These studies often supplement video with other forms of qualitative data, such as observation notes, interviews, and archival data.

Exemplar studies

The work by Clarke (Citation2011) and Cornelissen et al. (Citation2012) exemplifies the potential of videography for understanding the real-time unfolding of practices of entrepreneurship. In Clarke’s (Citation2011) study, the author asks how entrepreneurs justify and legitimize their new ventures to acquire necessary resources for venture growth. Rather than interview or survey entrepreneurs and stakeholders separately, the author made videos of three entrepreneurs as they interacted with various stakeholders in real time. The study has vastly deepened our understanding of resourcing practice and impression management by offering recorded material that includes real-time entrepreneurial language, gestures and visual tools, and symbols used to develop, discuss, and establish legitimacy. In particular, a close analysis of the videos reveals the ways in which entrepreneurs “set the scene,” embody their professional identify, and regulate their emotions when engaging in resourcing practice. Similar to Clarke (Citation2011), Cornelissen et al. (Citation2012) explored how entrepreneurs gain support and traction for novel venture ideas by shadowing and shooting video of the interactions of two entrepreneurs over the course of one month. An analysis of the video corpus shows how gestures and metaphors are utilized alongside speech to emphasize the agency of the entrepreneurs and their control of the venture and to argue for the predictability of an uncertain future. The authors also utilized unstructured interviews with the entrepreneurs to gain the entrepreneurs’ reflection on specific recorded incidents.

Limitations

Despite the gains being made with using videography to understand real-time entrepreneurial action, there are a number of limitations of current research. Often studies emphasize verbal language (verbal transcripts) and subsequently code and combine coding patterns of verbal talk across data of multiple cases to generate theory. However, developing codes and organizing them across cases may remove much of the contextual richness available in natural conversation, while downplaying the temporal, embodied, emotional, and material nature of the interactions. Studies that remain contextually rich also nevertheless remain entrepreneur-centered. In these studies, the authors observe naturally occurring practices, but the analytical focus remains on theorizing entrepreneurial behavior (talk, gestures, use of visuals). Hence, although data captures interactions among entrepreneurial practitioners (entrepreneurs, investors, suppliers, employees), theorizing reflects the researchers’ a priori assumptions and interests of the entrepreneur’s behavior. Although observable interactions in real time are evidence of the importance and connectedness of the body, materials, and discursive elements, aiming to create generalizable theories may downplay the variability of these interactions in the real world. A final limitation is that current research using videography of naturally occurring practices often presumes that the resulting videos represent objective data upon which new theory can be constructed. This fails to appreciate that the nuances and varieties of practices, as well as the researchers’ presence and decisions about what and how to film, are vital to the production of the data in the first place.

Video content analysis of entrepreneur-generated videos

Our review shows that the most common method is to conduct video content analysis that collects and analyzes videos generated by entrepreneurs themselves. Crowdfunding videos are publicly available and have provided a novel source for the growth of quantitative video content analysis, and qualitative studies have included videos generated by enterprises for promotional and informational purposes as part of their case study archives.

Crowdfunding videos

To date, researchers have utilized video content analysis of crowdfunding videos to gain insight into campaign success using exclusively quantitative methods. Hence, video content analysis on crowdfunding draws on a positivist methodology in an attempt to create objectivity and predict the outcomes of crowdfunding campaigns. Crowdfunding research is thus exclusively quantitative, with a heavily reliance on count data (for example, video/no video, number of videos, video length). Even those studies that engage with videos in more depth still attempt to reduce the video to a score out of 5 based on certain characteristics, such as “video quality” or “passion displayed” that can be linked to success. The focus on quantitative research can be explained by the allure of large-Ns (for example, Thies et al.’s Citation2019 study of 56,000 Kickstarter campaigns) and the accessibility of dependent variables of success such as “funds raised,” “goals reached,” and “numbers of contributors.” This quantitative treatment is compounded by the seminal study on crowdfunding by Mollick (Citation2014), which found that the mere presence of a video can influence campaign success. Building on this study, the majority of crowdfunding studies (13/25) incorporate the binary variable of whether video was present as part of the crowdfunding campaign as a control or independent variable to analyze determinants of success. As a result, over half of the video content analysis-based studies on crowdfunding reduce the complexity of crowdfunding campaign videos to a “yes” or “no.”

Only nine of the studies made use of meaningful elements of crowdfunding videos, such as: (a) coding direct from video to understand quality through questions such as “This video was well done” and “This video is high quality” assessed in a Likert scale (Chan et al., Citation2019; Scheaf et al., Citation2018; Younkin & Kuppuswamy, Citation2019); (b) converting videos to verbatim transcripts and using word counts and basket of words approaches to understand persuasion and rhetoric (Anglin et al., Citation2018; Kaminski & Hopp, Citation2020; Parhankangas & Renko, Citation2017); (c) coding directly from videos to understand displays of entrepreneurial passion using Chen et al.’s (Citation2009) passion scale (Chan et al., Citation2019; Oo et al., Citation2019); and (d) utilizing machine learning algorithms to identify specific elements in video such as objects (Kaminski & Hopp, Citation2020) or facial expressions (Jiang et al., Citation2019). Although the focus of video-based crowdfunding research has been on quantitatively examining determinants of success, these studies provide a grounding for more interpretative inquiry.

Exemplary studies

Exemplary studies using video content analysis of crowdfunding videos have explored how displays of positive emotions such as passion and joy are linked to campaign success (Chan et al., Citation2019; Oo et al., Citation2019). Jiang et al.’s (Citation2019) recent study makes use of automated facial expression analysis technology, FaceReader, to understand the role of joy displayed by entrepreneurs at the beginning and ending of crowdfunding pitches. Kaminski and Hopp (Citation2020) explore how language and visual cues (for example, objects, images, artifacts) influence campaign outcomes by using the Google Cloud Video Intelligence API. Analysis of over 900,000 objects from just over 20,000 campaigns reveals that illustrations or sketches of products have a negative impact on campaign success as investors may be more interested in finished products or prototypes than depictions and plans. Finally, Parhankangas and Renko (Citation2017) use basket of word analysis on verbatim transcripts to argue that social campaigns are more successful when they use language that is more understandable and relatable to the crowd. Throughout these exemplary studies, the authors support insights from the audio and visual elements from crowdfunding videos with text from campaign descriptions.

Limitations

Video content analysis on crowdfunding has some clear limitations. First, most studies reduce videos to count data, which, while gaining in generalizability, lose the potential richness of videos and fail to elaborate the role of video in legitimizing the venture or persuading the investor. As such, video data play a relatively subordinate role in analyses and findings. This research may also underappreciate the role of the “crowd” in crowdfunding by ignoring the relational and interactional nature of crowdfunding (videos), such as their sharing/commenting on social media. Finally, although studies of crowdfunding videos using machine learning show promise for analyzing the wealth of data available, they tend to strip videos of their context through analytical procedures, which may create contextual voids and reduce practical applicability in the pursuit of quantitative predictions.

Archival videos

The second use of video content analysis is collecting and analyzing archival videos. Researchers who draw on archival videos overwhelmingly use positivist methodologies to view this source of data as an objective historical account of events, decisions, or actions over the course of the research time frame. For example, Yu et al. (Citation2013) argue that China Central Television provides accurate and unbiased stories of Chinese rural entrepreneurs, which can be used to qualitatively build new theory. Archival videos are predominantly used in qualitative case studies and remain the most common form of method using videos in entrepreneurship research overall. The content of archival videos ranges broadly from promotional and informational videos to secondhand interviews, television news stories, documentaries, presentations by managers and entrepreneurs, and recorded histories of product development. All of these archival videos are produced either by the focal organizations or a third party and may vary in their manufactured/natural dimensions (for example, television story versus a recorded conversation). Archival videos are mostly used in combination with other qualitative information (for example, observations and interviews, archival documents and images) to generate insights into single or multiple case studies. Overall, content analysis of archival videos is seen as a way to gain insight into the development trajectory of a case and develop theoretical concepts.

Exemplary studies

One exemplary case using content analysis of archival videos in a single case design is that of Dodd (Citation2014). In this study, the author explores entrepreneurial notions of place, power, and practice in creative entrepreneurship through a longitudinal single case analysis of the punk rock band Rancid. The author combines 64 archival videos (including secondhand video interviews, “webisodes,” and music videos) with a wide range of other data sources, including albums, reviews, commentaries, and web sources. Investigating the qualitative data through content coding, the author distills Rancid’s entrepreneurial story as a cyclical, nonlinear journey from periphery to center and back again. Another exemplary study is that of Yu et al. (Citation2013), who use a multiple case study design. The authors use 91 television news stories, each about one case, produced by China Central Television to understand how Chinese rural entrepreneurs navigate their institutional environment. Using qualitative content coding, the authors investigate the links between institutional elements (that is, regulative, normative, and cognitive components) and the strategic behaviors of the entrepreneurs as they are represented in the news stories.

Limitations

Studies using content analysis of archival videos have a number of limitations. First and foremost, a closer investigation into the precise role an archival video played in analyses reveals that many studies remain unclear about how the video informed findings. Findings sections of these studies sometimes indicate a quote of a practitioner taken from an archival video, but many studies do not. As such, archival video often plays a subordinate role to other qualitative data, such as primary interviews. Second, by co-opting archival videos for research purposes and arguing that they provide objective insight into complex processes by which entrepreneurs generally achieve their aims, researchers might be downplaying the impact of decontextualization. For example, many archival videos are created for situational and practical reasons by entrepreneurs: The videos are themselves products of situationally relevant practitioner meanings, interests, and goals. Thus, using them as objective data for cross-case content analysis may remove the reasons for which the videos were created in the first place. Alternatively, Abdelnour and Branzei (Citation2010) adopt an interpretivist methodology and explore the development of fuel-efficient stoves in Darfur to theorize how subsistence markets are socially constructed in postconflict settings. In this study, videos are conceived of not as objective data but as a core element of discursive strategies by development organizations operating in postconflict settings.

Video elicitation in manufactured contexts

Our review found that a number of researchers use video elicitation methods in manufactured contexts to generate other qualitative or quantitative data that can be used for further analysis. By “manufactured contexts” we mean that the researchers (and sometimes third parties) have taken a number of steps to control and construct the context in which videos are created.

Interviews and focus groups

The simplest form of video elicitation involves video-recorded interviews and focus groups. Entrepreneurship studies using video interviews and focus groups are exclusively qualitative, with the videos generally accompanied with observations and document analysis. Despite the explicit mention of video recording in the methods section of these articles, the authors tend to reduce these video interviews to verbatim transcripts in their analysis, rendering them equivalent to audio-recorded interviews. The methodological stance underpinning verbatim transcripts is often positivism, which views the statements by entrepreneurs in video-recorded interviews or focus groups as objective data, which can be used in cross-case analysis for generating theory. However, a few studies have adopted interpretivism and have taken advantage of audiovisual and interactional elements to illustrate the potential of individual and group video interviews in explaining entrepreneurial phenomena.

Exemplary studies

Poldner et al.’s (Citation2019) study of sustainable entrepreneurship in the fashion industry exposes the potential of using video interviews to examine sociomateriality and the bodily nature of entrepreneurial endeavor. The authors use video interviews with designer entrepreneurs in their own studios to analyze the combination of verbal talk, gestures, visual materials, and objects, which reveals how the body and material come together in the performance of sustainable entrepreneurship. The authors make use of multiple sources of qualitative data to support insights from the video interviews, including participant observation, photos, attended catwalk shows, collected brochures, and purchased artifacts. Additionally, Haberman and Danes (Citation2007) illustrate how video-recorded group interviews can reveal power structures in entrepreneurial teams. They record video interviews with father-son and father-daughter dyads in family businesses who are in the process of transferring management control. The analysis of the videos focuses on the ways in which power structures, hierarchy, and gender roles are enacted through verbal and nonverbal actions in intergenerational relationships. Finally, Henry et al.’s (Citation2018) study of Māori entrepreneurship in the mainstream screen industry demonstrates how video interviews can assist in the cocreation of knowledge with the community. The authors cocreate a video documentary and investigate the tone of voice and facial expressions while empowering and advancing Māori entrepreneurship. This exemplar reflects how the production of video interviews can be a tool to conduct research alongside and for communities, aligning with calls for participatory and emancipatory inquiry in entrepreneurship (Gough et al., Citation2014).

Limitations

Current research using video-recorded interviews is often limited by the reduction of videos to verbatim transcripts. While reducing interviews to verbatim transcripts is necessary from a positivist standpoint, it may lose the potential richness of video interviews by failing to exploit the insights offered by tone and facial expression, body language and gestures, and other material elements that influence entrepreneurial lived experience. Rendering video-recorded interviews and focus groups to text may obscure the insights that could be garnered from analyzing interactions and group dynamics between those in the videos. As highlighted by Poldner et al. (Citation2019), the overreliance on talk and text and the prioritization of verbal accounts dismisses how “video and other visual methods offer an aesthetic avenue to knowledge creation beyond the textual, rational evidence” (p. 222). In this current treatment, the use of video-recorded interviews often does not take full advantage of multimodal elements that uncover the everyday practices of entrepreneurship, relying instead on how entrepreneurs describe their world.

Experiments and interventions

The second way in which scholars use video elicitation methods is through experimental and interventionist research designs. The purpose of videos in these studies is to elicit various responses from research participants (entrepreneurs, investors, students, or “the crowd”) to generate other qualitative or quantitative data. Hence, video is commonly seen as a “stimulus” to generate survey or qualitative data rather than being the subject of analysis itself. Scholars that use video elicitation to generate quantitative data begin from a positivist methodology and thus strive to eliminate contextual aspects of a phenomenon to focus subjects’ impressions on a single behavior. For example, Shane et al. (Citation2019) commissioned the production of videos that include only one person in the frame, the paid actor, who pitches a short-scripted idea. The use of manufactured-context videos has recently gained traction in experimental studies, which includes scholars using entrepreneur-generated video or videotaping hired professional actors to enact various forms of behavior. These videos are then used to stimulate the participant to generate another data set, such as completion of a survey, which is analyzed quantitatively.

Exemplary studies

One exemplary study of using video to elicit responses combines manufactured context videos, surveys, and fMRI technology. Shane et al. (Citation2019) examine the effect of founder passion on the decision-making of informal investors by testing hypotheses formulated from entrepreneurial passion and neural engagement theories. To do so, the authors recruited 10 actors and had them deliver two scripted pitches each in front of a camera: once with high passion and once with low passion. Next, the authors asked 19 randomly assigned informal investors to view the entrepreneur pitch videos while undergoing fMRI scanning. Subsequently, the participants were asked to complete a short survey that reported interest in investing in the ventures.

Only one study using videos to elicit responses begins with an interpretative methodology to generate qualitative data. In their innovative study, Ashman et al. (Citation2018) engaged with young YouTubers striving to become “autopreneurs” (a portmanteau of the terms “autobiographical” and “entrepreneur”) by participating in “vlogging”—the practices of creating, uploading, and commenting upon YouTube videos. Their analyses of participatory observation notes, combined with interviews, reveal the ways in which neoliberal ideologies shape and govern how these young entrepreneurs think and act. Ashman et al. (Citation2018) hence aim to produce knowledge through technology-enabled interaction with participants on their own terms.

Limitations

In Shane et al.’s (Citation2019) article, the brain images of informal investors that result from watching the manufactured videos are assumed to be driven from only the actors’ behavior in the video and not confounded by the manipulated and decontextualized nature of the videos, the reliability of fMRI technology, nor the research participants’ unusual immediate environment (that is, being in an fMRI machine watching entrepreneurship videos). Hence, studies that adopt a positivist methodology and use elicitation videos to generate quantitative data are possibly limited in their applicability to real-world settings, where contextual information, preexisting relations, norms, situational cues, and differing interpretations of information also shape entrepreneurial outcomes. On the other hand, using videos to participate in entrepreneurship communities may have the limitation of shaping entrepreneurial behavior that the researchers wish to study, which, at an extreme, may lead to self-fulfilling research findings.

A research agenda for video-based entrepreneurship research

Our literature review demonstrates that researchers have utilized three video research methods—videography, video content analysis, and video elicitation—to yield a greater understanding of entrepreneurial phenomena. Nevertheless, video data often take a subordinate role to other forms of qualitative and quantitative data, and only a limited number of studies fully utilize video’s unique affordances. In particular, the field has scarcely used videography of real-time, naturally occurring entrepreneurship practices, despite its unique ability to render them visible for analysis.

In this section, we develop a research agenda for video-based entrepreneurship studies that capitalizes on the unique audio, visual, and timing affordances of video by building upon the exemplary studies from the systematic review. We draw inspiration from traditions of video-based research in management, organization, and strategy research (Christianson, Citation2018; Gylfe et al., Citation2016; LeBaron et al., Citation2018) and the broader fields of research on anthropology, sociology, and psychology (Erickson, Citation2011; Knoblauch et al., Citation2008; Reavey, Citation2012). The research agenda overall highlights how video-based entrepreneurship research provides unparalleled insight into the interactional, embodied, emotional, and material aspects of entrepreneurial action—theoretical concepts that remain fundamental to future of entrepreneurship studies.

provides a summary of the possible research directions to understand the relational, embodied, material, and emotional aspects of entrepreneurial action. Although we have separated these elements in this review, one of the main benefits of video-based research is the ability to observe the combination of verbal, nonverbal (tone, gestures, facial expressions), interactional (founders, employees, customers, and financiers), and material objects (visual symbols, artifacts). Future research can therefore use video data to explore the combinations of interactional, bodily, emotional, and material components that shape entrepreneurial action.

Table 4. A research agenda for video in entrepreneurship research

Viewing the interactional aspects of entrepreneurial action

A growing number of entrepreneurship scholars argue that most, if not all, aspects of entrepreneurship happens in and through interaction with others (Chalmers & Shaw, Citation2017). In particular, these scholars aim to unpack interaction sequences related to entrepreneurship by revealing the underlying, and often tacit, ways in which entrepreneurial actors (entrepreneurs, investors, clients, etc.) orient to and respond to immediately prior actions in situ (Campbell, Citation2019).

One of video’s key strengths is observational access to the fast-paced interactional sequences practitioners actually undertake (Hindmarsh & Llewellyn, Citation2018; Jarrett & Liu, Citation2018). Researchers analyzing video data can carefully reveal the variety of forms of particular interactional sequences and practitioner methods that give an orderliness to social situations and accomplish tasks and aims (Vesa & Vaara, Citation2014). Hence, rather than turn to individual introspection, video data draw analytical attention to interactions that underscore entrepreneurial phenomena, such as decision-making, creativity, and design (Campbell, Citation2019). For example, videography enables researchers to understand the (variety of) interaction sequences among entrepreneurs, audiences, judges, and investors that occur before, after, and during pitches in certain contexts. This would help answer questions as to how entrepreneurs build support and legitimate ideas in interaction. Research could also explore a broader range of venture-making practices than currently considered. For example, researchers can use videography to reveal and explain the common venture-making practice of “selling” (Matthews et al., Citation2018), which incorporates customer agency into interactional processes of opportunity identification, refinement, and exploitation.

Possibilities also exist to explore entrepreneurial interaction through video content analysis and video elicitation. Within crowdfunding research, video content analysis can augment positivist research on the predictors of campaign success by qualitatively appreciating the varieties of interactions and practices enacted and conveyed through crowdfunding videos. These may include unpacking identity work, sensemaking, and gender stereotypes produced through interactions between the entrepreneur and the crowd using real-time video updates and social media comments. Furthermore, following Haberman and Danes (Citation2007), video elicitation can be used to combine group and individual interviews to explore how power structures, gender roles, and group dynamics matter in different contexts such as investor-entrepreneur relationships or entrepreneurial teams.

Viewing the embodied aspects of entrepreneurial action

In recent years, interest in embodiment (and embodied cognition) has grown given findings that bodies (gestures, facial expressions, and positions) and bodily experience influence entrepreneurial action (Clarke et al., Citation2021). As such, new gains will be made by understanding of the ways in which entrepreneurial practitioners (consciously and unconsciously) use and respond with their bodies when pursuing their aims (Clarke et al., Citation2018; Cornelissen et al., Citation2012).

Video provides a powerful means through which researchers can explore embodied lived experience of entrepreneurship. Videography of naturally occurring practices have a natural strength in revealing the importance of bodily gestures, gaze, and position for interactional outcomes, such as acquiring resources and legitimacy or establishing partnership (Clarke, Citation2011; Cornelissen et al., Citation2012). In the realm of pitching, researchers could pay greater attention to the embodied performances of entrepreneurs to answer questions of how various gestures and body language matter in their conversations with investors and audiences. Video content analysis of crowdfunding videos could pay greater attention to the bodily performances used to secure funding, and building on Poldner et al. (Citation2019), future video elicitation research could use on-site video interviewing to understand the embodied aspects of everyday entrepreneurial work. Following Slutskaya et al.’s (Citation2018) future research could also collaborate with entrepreneurs to create participatory video ethnographic documentaries. These videos could subsequently be shown to the same practitioners for them to generate qualitative insights into the culturally embedded, inarticulate, and embodied aspects of entrepreneurial action.

Viewing the emotional aspects of entrepreneurial action

Entrepreneurship scholarship has acknowledged that entrepreneurship is an emotional journey (Baron, Citation2008; Cardon et al., Citation2012; Shepherd, Citation2015), yet scholars have traditionally drawn on survey, interview, and experimental data to shed light on entrepreneurial emotions. Recently, a number of researchers have called for further understanding of the situational and contextual occurrences of emotional displays to better theorize how they come to matter for interactional outcomes.

Video-based methods render episodic expressions of emotions as they happen in context and interaction (Liu & Maitlis, Citation2014). Hence, they provide an opportunity for scholars to understand the situations and contexts in which emotions arise, how they influence interactional outcomes, and to challenge the notion of decontextualized emotional displays, emotions as separate processes or as private events (Cardon et al., Citation2017). Future research could build on recent work that utilizes videography to explore how emotional displays involved in tone, gestures, and facial expressions influence interactions with various stakeholders (Clarke et al., Citation2018; Jiang et al., Citation2019; Stroe et al., Citation2019). On the other hand, future video content analysis studies could explore how various enactments of emotions in crowdfunding campaigns shape emotional contagion between entrepreneurs and their crowd. Finally, video elicitation studies using video interviews also have the potential to gain insights into emotional experiences of passion or failure by analyzing audiovisual elements that better appreciate tone, expression, and gestures.

Viewing the material aspects of entrepreneurial action

Future video-based entrepreneurship research is uniquely positioned to enhance our understanding of the ways “matter matters” for entrepreneurial practice (Hindmarsh & Llewellyn, Citation2018). As entrepreneurs pursue their aims, they interact with, manipulate, and deploy objects, artifacts, and technologies (Holt, Citation2008; Korsgaard, Citation2011). Livestock, tractors, phones, desks, computers, software, etc., are not background elements or abstract resources of entrepreneurship; they are the very means of conducting entrepreneurship (Jones & Holt, Citation2008; Morgan-Thomas, Citation2016; Thompson & Byrne, Citation2019). Current research mostly overlooks or downplays when, where, how, and why material objects, settings, and technologies are used in real time to accomplish entrepreneurship practices.

Video methods enable researchers to observe and study the role of material objects, settings, and technologies by focusing analytical attention on the conduct of practitioners toward some (but not all) material features of the settings they inhabit. Videography can assist in focusing analytical attention on “matter as a members’ concern,” unlocking insight into how and why practitioners manipulate and deploy objects, artifacts, and technologies during the performance of a particular entrepreneurship practice (Hindmarsh & Llewellyn, Citation2018; Holt, Citation2008; Korsgaard, Citation2011). As such, video-based methods are critical as they allow researchers to establish the “procedural consequentiality” of when, where, how, and why some object, artifact, or technology can be seen to have determinate consequences for the way in which a practice unfolds (Schegloff, Citation2007).

Future research could utilize videography of the naturally occurring practices related to “idea generation” to focus on how objects and artifacts, such as Post-It notes, canvases, and whiteboards, become relevant within moments of entrepreneurial actions. In the context of pitching, research could also use videography to explore the role of material elements in conveying meaning, such as pitch decks, demos, and sets, as well as the practices that were used to create them. By attending to materiality in real-time observations of pitching and other practices, researchers have the opportunity to explore the development and varied role of artifacts throughout the entrepreneurial journey.

Studies utilizing video content analysis could also provide access to the material nature of entrepreneurial action. For example, focusing on the material elements of crowdfunding videos provides a fruitful research avenue. Building on the work of Kaminski and Hopp (Citation2020), future qualitative research using crowdfunding videos could also explore the ways in which entrepreneurs engage with objects, artifacts, images, and prototypes in their pitches to legitimize their ideas and persuade funders. Future video elicitation studies using interviews could also pay greater attention to the material contexts in which the interviews take place. Following Poldner et al. (Citation2019), video-recorded interviews of entrepreneurs at their workplace can shift attention to the role of artifacts and place in understanding entrepreneurial action.

Illustrative example

We provide a brief illustrative example to visualize and ground the research agenda. The illustrative example video excerpt in is taken from a larger corpus of videographic data collected by the authors. The context of the excerpt is a start-up weekend event in which a team made up of two entrepreneurs and two student participants are codeveloping initial ideas for a business model. provides an analysis of this short excerpt (1 minute, 12 seconds) to illustrate the potential of video data to deepen insights into each section of the research agenda.

Table 5. Excerpt of videographic data from a start-up weekend event (Student participants 1 & 2; Entrepreneurs 1 & 2)

Table 6. Analysis of illustrative example

Discussion and conclusion

Although the use of video methods has seen rapid growth in the past few years, we have lacked an overview of their various types, the extent of their integration into research designs, and their future potential for understanding entrepreneurial action. This study contributes to calls for more creative qualitative research methods by conducting a systematic review that identifies three main ways of using video-based methods, each with benefits, limitations, and future opportunities. Building on these findings, we further contribute by developing a research agenda by arguing that the unique affordances of video allow researchers (and practitioners) unparalleled access to the interactive, embodied, emotional, and material aspects of entrepreneurship action.

Our research agenda shows that video-based research enables us to view entrepreneurship from a new angle, which can drive novel theoretical contributions. Video-based research on interaction can extend insights on power relations (Goss et al., Citation2011), social capital (Anderson et al., Citation2007), and the interactional nature of resource mobilization (Tatli et al., Citation2014). Video-based research on embodiment can add depth to the bodily nature of entrepreneurial practice (Thompson et al., Citation2020) and highlight the entanglement of body and mind in entrepreneurial practice (Merleau-Ponty, Citation2004). Using video to understand entrepreneurial emotion can help theorize their collective nature as enacted in entrepreneurs (Zietsma et al., Citation2019) and the diversity of cues (for example, verbal, vocal, facial, bodily) that entrepreneurs use in emotional work (Planalp, Citation1996). Finally, using video can help expand conversations on how materiality shapes entrepreneurial action, bringing entrepreneurship research into closer contact with discussions on sociomateriality in studies of management and organizations (Katila et al., Citation2019; Symon & Whiting, Citation2019).

Our findings also highlight the complementarity between video data and other qualitative data such as observation, interviews, and archival documents. Video methods can be utilized to deepen the insights garnered through observation and ethnographic field notes by allowing researchers to revisit particular insights or observe incidents from different perspectives. Similar to traditional ethnographic data, video can complement interview-based studies by giving insights into real-time entrepreneurial practice. Other forms of qualitative data can enhance the insights from video-based studies. Interviews with entrepreneurs about specific video-recorded incidents can assist in the process of interpretation. Similarly, archival data such as documents or artifacts can confirm or contradict interpretations of video-recorded action. To take advantage of this complementarity, video methods should be added to the suite of qualitative researchers’ methods.

Despite the potential offered by video-based research, entrepreneurship research should also consider the practical constraints and limitations of video-based methods. Video-based research creates numerous practical challenges in terms of privacy, access, timing, and the investment of time and resources in developing a mastery of video storage and analysis tools. Similar to other forms of observational research, video-based studies also face limitations related to volume of data generated, whether practitioners act “naturally” when being filmed, and the positioning of the observer (and their equipment) (Heath & Hindmarsh, Citation2002; Heath et al., Citation2010). As Zundel et al. (Citation2018) emphasizes, “epistemologically, video research not only documents but intervenes” (p. 388). Few entrepreneurship scholars take a critical perspective on why videos are produced in the first place; thus there is room for more reflexivity of appreciating the context and performative nature of videos themselves. Finally, entrepreneurship scholars will need to clarify why video data made a difference to a theoretical understanding of a phenomenon. Following LeBaron et al. (Citation2018), “simply showing that nonverbal communication is also part of group interactions, without furthering understanding about how groups interact, is not sufficient for a (theoretical) contribution” (p. 255). Researchers hoping to enter the world of video-based research should weigh these practical constraints and limitations against the potential benefits of accessing the interactive, embodied, emotional, and material nature of entrepreneurial action.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Ella Hafermalz for her detailed and insightful comments on this manuscript. We would also like to thank our coauthors on our own ongoing practice-based entrepreneurship studies for thinking through the value and possibilities of video-based research with us. Finally, we thank the special issue editors and two anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments in shaping this paper.

References

- Abdelnour, S., & Branzei, O. (2010). Fuel-efficient stoves for Darfur: The social construction of subsistence marketplaces in post-conflict settings. Journal of Business Research, 63(6), 617–629. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.04.027

- Anderson, A., Park, J., & Jack, S. (2007). Entrepreneurial social capital: Conceptualizing social capital in new high-tech firms. International Small Business Journal, 25(3), 245–272. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242607076526

- Anglin, A. H., Wolfe, M. T., Short, J. C., McKenny, A. F., & Pidduck, R. J. (2018). Narcissistic rhetoric and crowdfunding performance: A social role theory perspective. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(6), 780–812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2018.04.004

- Ashman, R., Patterson, A., & Brown, S. (2018). ‘Don’t forget to like, share and subscribe’: Digital autopreneurs in a neoliberal world. Journal of Business Research, 92, 474–483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.07.055

- Barinaga, E. (2017). Tinkering with space: The organizational practices of a nascent social venture. Organization Studies, 38(7), 937–958. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840616670434

- Baron, R. A. (2008). The role of affect in the entrepreneurial process. Academy of Management Review, 33(2), 328–340. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2008.31193166

- Berger, I. E., Cunningham, P. H., & Drumwright, M. E. (2004). Social alliances: Company/nonprofit collaboration. California Management Review, 47(1), 58–90. https://doi.org/10.2307/41166287

- Berglund, H. (2007). Researching entrepreneurship as lived experience. In J. Ulhoi & H. Neergaard (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research methods in entrepreneurship (pp. 75–93). Edward Elgar.

- Boyatzis, R. E. (1998). Transforming qualitative information: Thematic analysis and code development. Sage.

- Bradbury, H., & Clair, J. A. (1999). Promoting sustainable organizations with Sweden’s natural step. Academy of Management Perspectives, 13(4), 63–74. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1999.2570555

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Brugman, H., & Kita, S. (1995). Impact of digital video technology on transcription: A case of spontaneous gesture transcription. Kodikas, 18(1–3), 95–112.

- Buttner, E. H. (2001). Examining female entrepreneurs’ management style: An application of a relational frame. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(3), 253–269. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1026460615436

- Campbell, B. (2019). Practice theory in action: Empirical studies of interaction in innovation and entrepreneurship. Taylor & Francis.

- Cardon, M. S., Foo, M.-D., Shepherd, D., & Wiklund, J. (2012). Exploring the heart: Entrepreneurial emotion is a hot topic. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 36(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2011.00501.x

- Cardon, M. S., Mitteness, C., & Sudek, R. (2017). Motivational cues and angel investing: Interactions among enthusiasm, preparedness, and commitment. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 1057–1085. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12255

- Chalmers, D. M., & Shaw, E. (2017). The endogenous construction of entrepreneurial contexts: A practice-based perspective. International Small Business Journal, 35(1), 19–39. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242615589768

- Chan, C. S. R., Parhankangas, A., Sahaym, A., & Oo, P. (2019). Bellwether and the herd? Unpacking the u-shaped relationship between prior funding and subsequent contributions in reward-based crowdfunding. Journal of Business Venturing, 34(Online First), 646–663. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2019.04.002

- Chen, X.-P., Yao, X., & Kotha, S. (2009). Entrepreneur passion and preparedness in business plan presentations: A persuasion analysis of venture capitalists’ funding decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 52(1), 199–214. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.36462018

- Christianson, M. K. (2018). Mapping the terrain: The use of video-based research in top-tier organizational journals. Organizational Research Methods, 21(2), 261–287. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428116663636

- Clarke, J. (2011). Revitalizing entrepreneurship: How visual symbols are used in entrepreneurial performances. Journal of Management Studies, 48(6), 1365–1391. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.01002.x

- Clarke, J., & Cornelissen, J. (2011). Language, communication, and socially situated cognition in entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 36(4), 776–778. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2011.0192

- Clarke, J. S., Cornelissen, J. P., & Healey, M. P. (2018). Actions speak louder than words: How figurative language and gesturing in entrepreneurial pitches influences investment judgments. Academy of Management Journal, 62(2), 335–360. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2016.1008

- Clarke, J. S., Llewellyn, N., Cornelissen, J., & Viney, R. (2021). Gesture analysis and organizational research: The development and application of a protocol for naturalistic settings. Organizational Research Methods, 24(1), 140–171. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428119877450

- Cornelissen, J. P., Clarke, J. S., & Cienki, A. (2012). Sensegiving in entrepreneurial contexts: The use of metaphors in speech and gesture to gain and sustain support for novel business ventures. International Small Business Journal, 30(3), 213–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610364427

- Dana, L. P., & Dana, T. E. (2007). Collective entrepreneurship in a mennonite community in Paraguay. Latin American Business Review, 8(4), 82–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/10978520802114730

- Dodd, S. L. D. (2014). Roots radical – Place, power and practice in punk entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 26(1–2), 165–205. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2013.877986

- Drakopoulou Dodd, S., Wilson, J., Bhaird, C. M. A., & Bisignano, A. P. (2018). Habitus emerging: The development of hybrid logics and collaborative business models in the Irish craft beer sector. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 36(6), 637–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242617751597

- Erickson, F. (2011). Uses of video in social research: A brief history. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 14(3), 179–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2011.563615

- Fayolle, A., & Wright, M. (2014). How to get published in the best entrepreneurship journals: A guide to steer your academic career. Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Goss, D., Jones, R., Betta, M., & Latham, J. (2011). Power as practice: A micro-sociological analysis of the dynamics of emancipatory entrepreneurship. Organization Studies, 32(2), 211–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840610397471

- Gough, K. V., Langevang, T., & Namatovu, R. (2014). Researching entrepreneurship in low-income settlements: The strengths and challenges of participatory methods. Environment and Urbanization, 26(1), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956247813512250

- Gylfe, P., Franck, H., Lebaron, C., & Mantere, S. (2016). Video methods in strategy research: Focusing on embodied cognition. Strategic Management Journal, 37(1), 133–148. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2456

- Haberman, H., & Danes, S. M. (2007). Father-Daughter and Father-Son family business management transfer comparison: family FIRO model application. Family Business Review, 20(2), 163–184. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2007.00088.x

- Heath, C., & Hindmarsh, J. (2002). Analysing interaction: Video, ethnography and situated conduct. In T. May (Ed.), Qualitative research in practice (pp. 99–121). Sage.

- Heath, C., Hindmarsh, J., & Luff, P. (2010). Video in qualitative research: Analysing social interaction in everyday life. Sage.