ABSTRACT

Little research has been conducted regarding serial entrepreneurship compared to entrepreneurship research more broadly, despite research that suggests that as many as 50% of all entrepreneurs are serial entrepreneurs. Entrepreneurship research shows that most new ventures fail, yet serial entrepreneurs continually exit previous ventures and start new ones. Our study explores 118 scholarly articles indexed in Web of Science and Scopus databases on serial entrepreneurship through multiple correspondence analysis. Through our analysis, we identify key areas for future research, explore and consolidate the theoretical foundations used, and provide a review of academic literature for future researchers to utilize. Our perceptual map has identified four key research areas that researchers should focus upon: heuristics in entrepreneurship, entrepreneurial capabilities, the entrepreneurial ecosystem, and technological development and resources.

Introduction

Entrepreneurs face high rates of failure (Klimas et al., Citation2021). Research suggests that most of them fail (Lee et al., Citation2021). However, many entrepreneurs continuously start new ventures; either developing new ventures while operating in an existing firm (portfolio entrepreneurship) or starting a new venture after ending another (serial entrepreneurship). These types are considered habitual entrepreneurship (Plehn-Dujowich, Citation2010; Westhead et al., Citation2005; Westhead & Wright, Citation1998). Recent research suggests that a significant portion (as high as 50%) of new entrepreneurial ventures are made by those who have had entrepreneurial experience (Ucbasaran et al., Citation2010). As such, we explore the scholarly literature pertaining to serial entrepreneurship, as further research is needed (Kraus et al., Citation2020).

As research suggests, most new ventures fail. The ramifications of failure have traumatic effects upon the individual, leading to depression, feelings of worthlessness, a damaged reputation, depleted social capital, and loss of financial resources (Baù et al., Citation2017). Hence, the question remains: why do serial entrepreneurs continue? Research has begun to examine serial entrepreneurs, focusing on grief recovery, the ways in which they learn from failure, and entrepreneurs’ opportunity identification and implementation skills (Cope, Citation2011). Given that this research has only just begun (Lattacher & Wdowiak, Citation2020), and due to this contradiction of failure and continuance of new ventures, more theoretical and empirical research is required (Hsu et al., Citation2017; Klimas et al., Citation2021).

Our research focuses on a type of habitual entrepreneurs – serial entrepreneurs – who possess different characteristics to those who try for the first time (novice entrepreneurs) or those who run more than one operation at the same time (portfolio entrepreneurs) (Westhead & Wright, Citation1998). Serial entrepreneurs are very common and are considered habitual entrepreneurs, exiting one venture before entering into a subsequent one (Ucbasaran et al., Citation2009). The combination of serial entrepreneurs exiting one venture for several reasons, such as failure, personal reasons, or selling the venture, and the continuous reentering of the marketplace due to their previous venture, requires further research (DeTienne & Cardon, Citation2012). Essentially, experiences of failure or success form very different learning paths and alternate perspectives regarding restarting conditions (Eggers & Song, Citation2015) which, without specific consideration, could be deemed to clash (Sarasvathy et al., Citation2013).

Past research has explored entrepreneurs who have failed in their ventures and have exited the marketplace permanently due to their substantial personal, financial, and emotional loss. This diminishes their confidence in starting a new venture, impacts their motivation to try again, and affects the extent to which they will take risks (DeTienne, Citation2010; DeTienne & Chirico, Citation2013). However, this research also suggests that, of those who have failed, many do start new ventures and perform better in comparison to those who have started new ventures for the first time (Stam et al., Citation2008). As such, research now examines the learning effects of previous failed entrepreneurial experiences, such as lessons learned, whether the serial entrepreneur has learned more from failure than from past success, and the impact on human capital, business plan acumen, and efficiency of opportunity recognition in response to marketplace analysis (Cope, Citation2011). Following the call for continued empirical studies of business failures and serial entrepreneurship (Lee et al., Citation2021; Sarasvathy et al., Citation2013), researchers have focused on age and entrepreneurial reentry (Baù et al., Citation2017), previous failed versus successful ventures, and their differing learning effects (Eggers & Song, Citation2015), and how serial entrepreneurs learn from their past experiences (whether failure or success) and improve their performance over time (Vaillant & Lafuente, Citation2019).

Building upon the absence of research in academic journals, in which most studies focus on failures rather than successful ventures, as well as the constant calls noted above for more research into serial entrepreneurship, we formulate the following research questions:

RQ1: What do we know about serial entrepreneurs?

RQ2: What are the key characteristics of serial entrepreneurs that set them apart from other types of entrepreneurs?

RQ3: What key areas require further research with regards to serial entrepreneurs?

Our research expands the dynamic entrepreneurship research field through a systematic and bibliometric analysis of “serial entrepreneurs.” Accordingly, this is one of the first studies to review the serial entrepreneurship research domain systematically. Our work outlines theoretical underpinnings, research themes, and contexts through a multiple correspondence analysis (MCA) (Hoffman & De Leeuw, Citation1992). As presented in the following section, this methodological approach enabled us to examine certain inferences regarding the research domain’s underlying structure, enabling us to propose future research avenues.

Methodology

A literature review denotes the relevant synthesis and scientific reflection of a research domain (Mas-Tur et al., Citation2020; Patriotta, Citation2020), intending to stimulate the domain’s understanding and promote future research (Casprini et al., Citation2020; Ferreira et al., Citation2019; Kraus et al., Citation2020). As a literature review provides a reference point and represents the very essence of a research field, Bem (Citation1995, p. 172) has defined review papers as “critical evaluations of material that has already been published.” In order to produce a comprehensive review paper, authors should perform their studies in a systematic way (Hulland & Houston, Citation2020; Littell et al., Citation2008).

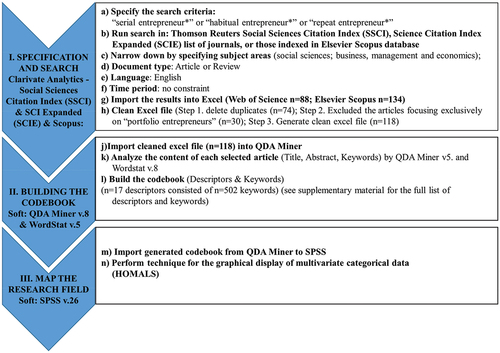

We operationalized the systematic review methodology approach as follows (see ). Firstly, we defined the search criteria and collected the articles. Next, we analyzed the identified publications and created the content-based codebook. Finally, we performed MCA analysis and outlined the serial entrepreneurship research domain, presented in the following section, by elaborating upon the underlying theoretical foundations, the major research themes, geographical contexts, and the methodologies employed.

The sample of articles and data collection

To address the serial entrepreneurship research domain, we searched for academic publications which, in their title, abstract or keywords, contained terms such as “serial entrepreneur(s),” “habitual entrepreneur(s),” or “repeat entrepreneur(s),” as outlined by Westhead and Wright (Citation1998) and Guerrero and Peña-Legazkue (Citation2019). Accordingly, “habitual entrepreneur” represents an umbrella term for “serial entrepreneurs” and “portfolio entrepreneurs.” Serial entrepreneurs are conceptualized as habitual entrepreneurs who exit one venture before entering into a subsequent one (Sarasvathy et al., Citation2013; Ucbasaran et al., Citation2006), while portfolio entrepreneurs continue to manage their original business and inherit, establish, and/or purchase another business (Westhead & Wright, Citation1998). Thus, to map the trajectory of the serial entrepreneurship research field, we included both the serial entrepreneur (repeated entrepreneur) and the habitual entrepreneur and performed the search in Thomson Reuters Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI), Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) list of journals, and Elsevier Scopus database (Kiessling et al., Citation2021). Next, to ensure the reliability of our research and present the progression of the research field, we focused on academic journals with a peer-review process, written in English. We excluded book chapters, book reviews, conference proceedings, and editorial notes without any time constraints (Gonzalez-Loureiro et al., Citation2015; Vlačić et al., Citation2021). This search criterion resulted in 118 articles. To ensure consistency, an international team of five members selected the articles that addressed the attributes of the serial entrepreneur, excluding the articles focusing exclusively on portfolio entrepreneurs.

The selected articles were published in academic journals between 1997 and 2020, with the following distribution: 1997–2002, 3%; 2003–2008, 16%; 2009–2014, 39%; 2015–2020, 42%. This distribution, as well as the outlets in which the articles are published, such as the Entrepreneurship: Theory and Practice, Small Business Economics, and the Journal of Business Venturing, among others, indicate increasing interest level in serial entrepreneurship. outlines the journals most frequently publishing articles in the serial entrepreneurship research domain.

Table 1. Overview of most frequent journal sources by the number of articles.

The building of the codebook

The procedure for building the codebook (see ) involved, in the beginning, the identification of the main descriptors within the serial entrepreneurship domain, followed by MCA (Dabić et al., Citation2020). In line with the methodological procedures presented in López-Duarte et al. (Citation2016, p. 512), using QDA Miner v.5 and WordStat v.8 software, this step by step approach consisted of “(I) extracting the key content from the articles’ titles, abstracts and keywords; (II) classifying it in order to build a reduced list of the core descriptors; (III) revising the codebook by merging the similar categories in order to obtain a meaningful list of descriptors in terms of content and frequency.” The origin of the preliminary codebook was built upon published literature reviews (Klimas et al., Citation2021; Tipu, Citation2020). Next, in accordance with the initial categorization, the authors extracted the key content and created the final codebook, consisting of 502 keywords classified under 17 descriptors. Subsequently, these descriptors were grouped into four broad themes according to their characteristics: theoretical approaches/frameworks, major research themes, methodologies used, and geographical context (the comprehensive list of keywords and descriptors is available in the supplementary material).

The multiple correspondence analysis (MCA)

In order to depict the serial entrepreneurship intellectual structure, we used MCA. MCA represents a quantitative technique for investigating qualitative data (Hoffman & De Leeuw, Citation1992) and is widely used to detect the relationships between binary variables (the presence of the defined keywords in this study) (Gifi, Citation1990). Consequently, if the keyword were present, a value of “1” would be entered. The value would be “0” if absent. Consistent with the objectives of the study, the homogeneity analysis by means of alternating least squares (HOMALS) analysis was performed using SPSS v.26 software. Ultimately, this approach enabled a low-dimensional proximity illustration of the research domain, with the descriptors positioned along the two axes (see ). In cases where a large proportion of the articles involved similar descriptors (that is, corresponding to the common constituent), those descriptors were positioned closer together and vice versa (Bendixen, Citation1995; Kiessling et al., Citation2021). The descriptors with the highest number of articles within the field were positioned closer to the center of the map.

Illustration of the serial entrepreneurship research field

In order to reveal the intellectual structure of research on serial entrepreneurship, the initial phase necessitated an understanding of the dimension poles (see ) (Hoffman & De Leeuw, Citation1992). The results yielded the explained variance of 25.6%, which, in turn, tended to misrepresent the validity of the MCA approach. Accordingly, given that the map combines the information of the k variables in only two dimensions (that is, representing high-dimensional space in a low-dimensional proximity illustration), Dabić et al. (Citation2020) and López-Duarte et al. (Citation2016), following Hair et al. (Citation1998) recommendations, noted that the grand mean of keywords per article is more profound and should be larger than 1. In our case, it was 1.27.

Table 2. Descriptors that represent the poles of the axes.

Table 3. Mapping streams and avenues for the future research agenda of serial entrepreneurship.

The far-left pole of the horizontal line revealed the dimensions of an entrepreneurial ecosystem. The publications within this category focus on the role of institutions and serial entrepreneurs’ performance indicators (Ensign & Farlow, Citation2016; Pittz et al., Citation2021), using characteristic keywords such as institutions, ecosystem, efficiency, and economic growth, among others. The far-right end of the horizontal dimension displays studies focused on entrepreneurial capability, examined through the lenses of capital theory, diversity, gender, and disadvantage perspective (Barnir, Citation2014; Mosey & Wright, Citation2007; Simmons et al., Citation2019). Some of the representative keywords for the descriptors positioned at this pole are capital, human capital, gender, and disadvantage. The upper part of the vertical axis demonstrates researchers’ focus on the role of heuristics and behavioral underpinnings in serial entrepreneurship, with reference to serial entrepreneurs’ attributes, behavior, emotions, strategic orientation, and business development, among other qualities (Hayward et al., Citation2010; Hsu et al., Citation2017). Meanwhile, the lower part of the vertical axis focuses on serial entrepreneurs’ relationships with ongoing technological development and technopreneurship fields, including elements of innovation, innovativeness, and high tech, as well as access to resources and aspects of crowdfunding (Butticè et al., Citation2017; Gruber et al., Citation2008; Lahiri & Wadhwa, Citation2020).

In the remainder of the section, we provide further details on these aspects of the research field. Thus, the following sub-sections outline the theoretical foundations, major research themes, and methodological approaches and contexts of the serial entrepreneurship research domain.

Theoretical foundations

Entrepreneurship, broadly defined as the process of setting up a business or businesses, involves the recognition and seizing of opportunities in an environment highly characterized by uncertainty (Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). Serial entrepreneurs consistently engage in entrepreneurial behaviors via constant and sequential entrepreneurial activities (Amaral et al., Citation2011). Seriality in entrepreneurship has been mostly investigated as a matter of occupational choice (Carbonara et al., Citation2020), with studies ranging in their approaches, forming a dichotomy between those arguing for the importance of learning by doing (Rocha et al., Citation2015) and those countering with the study of the innate abilities of individual serial entrepreneurs (Westhead & Wright, Citation1998).

Serial entrepreneurship is not well explained through existing theories of industry evolution and labor market theories of occupation choice. Researchers have thus utilized other theoretical foundations. Several studies on serial entrepreneurship are built upon the behavioral theory of the firm (Cyert & March, Citation1963) and the concepts of bounded rationality (Simon, Citation1972), which offer three conditions that may affect seriality in entrepreneurship. Firstly, causal ambiguity surrounding the action-outcome relationship makes it difficult for entrepreneurs to evaluate courses of action (Levitt & March, Citation1988). Secondly, entrepreneurs are prone to cognitive bias, such as over-confidence, which may cause dysfunctional outcomes due to asymmetry between subjective evaluations and actual abilities (Gudmundsson & Lechner, Citation2013). Thirdly, entrepreneurs struggle to evaluate outcomes due to the subjectivity of the definitions of success and failure (Hogarth & Karelaia, Citation2012).

Studies based on the principles of cognitive psychology are also pervasive in entrepreneurship (Baron & Ward, Citation2004; Mitchell et al., Citation2002). The concept of entrepreneurial cognition has been widely studied to describe how entrepreneurs think and behave (Sassetti et al., Citation2018; Vlačić et al., Citation2020). Entrepreneurial cognition pertains to “the knowledge structures that people use to make assessments, judgments, or decisions involving opportunity evaluation, venture creation and growth” (Mitchell et al., Citation2002, p. 97). The focus here is on how entrepreneurs use heuristics and are subject to bias. For example, Ucbasaran et al. (Citation2010) explored how serial entrepreneurs who have experienced failure do not appear to adjust their comparative optimism.

The entrepreneurial intention – as explained by models such as Shapero and Sokol’s (Citation1982) entrepreneurial event model (SEE) and Ajzen’s (Citation1991) theory of planned behavior (TPB) – has also been applied to the study of serial entrepreneurs. For example, the higher the level of entrepreneurial intention, the faster the serial entrepreneur’s rate of new venture creation (Kautonen et al., Citation2015; Krueger et al., Citation2000). According to the SEE model, the entrepreneurial intention is influenced by an individual’s perceived desirability, perceived feasibility, and propensity to act upon opportunities. The TPB model, instead, posits that entrepreneurial intention rests on the individual’s attitude toward an act, the subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control.

Entrepreneurship research is often grounded in institutional theory (North, Citation1990; Scott, Citation2013; Veciana & Urbano, Citation2008). From an institutional theory perspective, institutions are clusters of constructed moral beliefs that govern political, economic, and social interaction. Every society possesses formal institutions (that is, the legal and regulatory framework) and informal institutions that are the unwritten socially shared rules concerning acceptable and unacceptable behavior. The organizations, in our case new ventures, that come into existence will reflect the opportunities provided by the institutional framework (Fu et al., Citation2018).

Entrepreneurship scholars have given the concept of an entrepreneurial ecosystem (Isenberg, Citation2010) a great deal of attention as it offers a framework within which to describe the fostering of entrepreneurial action. As defined by Spigel (Citation2017, p. 49), “ecosystems are the union of localized cultural outlooks, social networks, investment capital, universities, and active economic policies that create environments supportive of innovation-based ventures.” Far from being an exclusive concept for entrepreneurship research, the ecosystem view is cross-disciplinary and adopted in other research areas to explore financial, economic, sociodemographic, or political issues (Kabakova & Plaksenkov, Citation2018). While keeping the entrepreneur as the focal point, the ecosystem emphasizes the contextual and institutional dynamics that constrain serial entrepreneurship. As such, national and regional formal business regulations, or social norms and values, may stigmatize failure, hence preventing seriality or, conversely, offering an institutional environment in which failure is accepted, and support is in place, fostering seriality. Similarly, written and unwritten norms may make it more or less desirable for an entrepreneur to move from business to business. In this vein, Simmons et al. (Citation2014) investigated the degree to which bankruptcy regulations formalized social norms with the public stigma of failure, instilling a more general and informal sentiment of fear of failure that may prevent entrepreneurs from restarting businesses.

The resource-based view (RBV) of the firm (Wernerfelt, Citation1984) constitutes another theoretical framework for the study of serial entrepreneurship. The RBV posits that competitive advantage is created and sustained over time when firms simultaneously possess valuable, rare, nonsubstitutable, and inimitable resources. The underlying assumption of RBV is the conceptualization of firms as agglomerations of resources heterogeneously distributed across firms. Eisenhardt and Martin (Citation2000) revealed that capabilities are needed to integrate, reconfigure, gain, and release resources, consisting of identifiable and specific routines that put resources into use. The RBV is a sound framework that can be used to explain the activities of SMEs and entrepreneurs. It is also able to account for informality in SMEs (Kraus et al., Citation2011).

The scholarly literature on serial entrepreneurship also rests on the relationship between experience, learning, and performance, with an underlying theoretical foundation of the knowledge-based view (KBV) of the firm (Grant, Citation2002). The KBV served as a prominent theoretical framework to account for the knowledge and learning factors shaping serial entrepreneurship. The skills and knowledge required to run a firm are predominantly experiential (Starr & Bygrave, Citation1991), and the creation of new ventures enhances the accumulation of entrepreneurship-specific human capital (Ucbasaran et al., Citation2009).

Experiential learning (Kolb, Citation1984) plays a key role in serial entrepreneurship as it has a positive effect upon the development of different types of skills, such as resource acquisition and organization (Cope & Watts, Citation2000; Stam et al., Citation2008; Van Gelderen et al., Citation2005), which augment entrepreneurial abilities by allowing the serial entrepreneur to recreate ventures at a faster pace, enabling them to perform better than novices (Cope, Citation2011; Parker, Citation2013; Starr & Bygrave, Citation1991).

The role of knowledge is also pivotal in supporting entrepreneurial actions in terms of opportunity recognition, discovery, and employment (Shane, Citation2000). While the ability to apply specific knowledge to a commercial opportunity requires a set of skills, insights, circumstances, and social mechanisms, the entrepreneurial ecosystem and the regulatory framework underpin the production and accumulation of knowledge and are critical for its subsequent distribution and use (Bozeman & Mangematin, Citation2004).

Zhang (Citation2011) suggested that serial entrepreneurs are more skillful and socially connected than novice entrepreneurs. The human capital theory acknowledges that individuals with higher quality human capital achieve better performance levels (Becker, Citation1962), further reinforcing the importance of knowledge, skills, and social capital in determining the success of serial entrepreneurs. Human capital is exemplified in entrepreneurship as the knowledge and skills that assist in successfully engaging in new ventures (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003). General human capital provides entrepreneurs with knowledge, skills, and problem-solving abilities that are transferable across many different life situations. In contrast, specific human capital pertains to the education, training, and experiences that are valuable to entrepreneurial activities but have few applications outside of this domain.

Given the shortcomings and evident overlaps of the several theoretical foundations in serial entrepreneurship, a promising contribution may come from theoretical approaches that bridge behavioral, institutional, and resource-based theories. For example, researchers usually employ three related theories to explain the diversity in organizations: the similarity and attraction paradigm, social categorization theory, and social identity theory. The similarity attraction paradigm predicts that similarities in attributes increase interpersonal attraction and liking. Individuals with similar backgrounds may share common values and may find it easier to interact with each other. Turner et al. (Citation1987) describe the self-categorization theory, instead, as the process by which people define their self-concept in terms of their membership to various social groups. Social identity theory (SIT) (Hogg & Abrams, Citation1988) suggests that group members establish a positive social identity and are likely to cooperate with members of the group and compete against those outside of it.

Barnir (Citation2014) unveiled gender differences in the effects of entrepreneurial impetus (such as business opportunities, mentors, and the nature of work) and human capital (such as education, employment breadth, managerial experience, and entrepreneurial capabilities) on serial entrepreneurship. Baù et al. (Citation2017) examined the seriality of failed entrepreneurs. They showed that reentry increases during the early career stage, decreases during the mid-career stage, and then increases again during the late-career stage – a relationship moderated by gender and multiple-owner experiences. Lin and Wang (Citation2019) further analyze the impact of age on serial entrepreneurship following failure, unveiling the direct impact of age moderated by failure, loss, and family support.

Major research themes and topics

Topic 1: Entrepreneurial opportunity-recognition and opportunity creation

For entrepreneurs, the key to success is to identify a marketplace need unmet by other incumbent firms and to fulfill this value proposition more effectively than other participants (Gaglio & Katz, Citation2001; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). This opportunity identification is a key component of entrepreneurial success and is the first step in the process of new venture creation (Bygrave & Hofer, Citation1992; Lumpkin & Dess, Citation1996). Why and how some people are able to identify these marketplace needs and take the risk to fulfill these customers’ expectations is considered foundational to entrepreneurship research (Gielnik et al., Citation2017; Shane & Venkataraman, Citation2000). Researchers have focused on opportunity identification in terms of where this ability comes from – perhaps an individual’s education, work experience, entrepreneurial experience, or experiential capability (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003).

Serial entrepreneurs, in particular, are an important topic of study as they are extremely competent at identifying marketplace opportunities (Taplin, Citation2008). Therefore, examining these individuals could help to shed light on how/where they garner their insight, the analysis/interpretation of this new knowledge, and the appropriate method of developing a business plan (Lumpkin et al., Citation2004). Recent research suggests that serial entrepreneurs are very successful in the opportunity recognition process (Urban, Citation2009). Some of the key findings regarding opportunity identification have suggested that new business opportunities often arise in connection with solutions to a specific problem after listening to customers’ wants/needs and creatively identifying latent business opportunities. Opportunities rarely come immediately but rather present themselves throughout a series of events. The serial entrepreneur realizes that mistakes are part of the entrepreneurial process and will apply any failure or success to future ventures (Lumpkin et al., Citation2004).

Research into serial entrepreneurs and their ability to identify marketplace opportunities for successful implementation overwhelmingly suggests that serial entrepreneurs can identify marketplace opportunities more than other participants (Ucbasaran et al., Citation2009). Past research supports this ongoing assertion as business ownership delivers skills specific to entrepreneurship, focusing its efforts on identifying and exploiting successful ideas (Chandler & Hanks, Citation1998; Gimeno et al., Citation1997). As a serial entrepreneur repeatedly starts businesses, the experienced entrepreneur understands the nuances required to identify opportunities and what is required to implement to seize them and ultimately start a new venture (Shane & Khurana, Citation2003; Starr & Bygrave, Citation1991).

Topic 2: Technopreneurship and innovation

“The real question, then, … [is] not whether entrepreneurs innovate, but rather, when and where they do so.” (Autio et al., Citation2014, p. 1098). Recent research investigating innovation and serial entrepreneurs suggests that innovativeness is shaped by past entrepreneurial experiences, as serial entrepreneurs have developed superior opportunity recognition abilities (Politis, Citation2005; Vaillant & Lafluente, Citation2019). The generative learning ability of serial entrepreneurs (taking past knowledge and applying it to new situations) helps develop new innovative products/services (Cope, Citation2005). Serial entrepreneurs are adept in innovation as entrepreneurial learning is primarily experience-based, with past knowledge accumulation guiding future opportunities for innovation (Minniti & Bygrave, Citation2001; Politis, Citation2005). Cognitive schemas are developed by serial entrepreneurs, facilitating the selection and discernment of valuable marketplace knowledge, understanding the importance of key trends, and innovative business plan developments (Baron & Ensley, Citation2006; Cope, Citation2005; Sarasvathy et al., Citation2013).

Serial entrepreneurs have demonstrated their ability to create inventions and possess the acumen to develop a business plan to make an innovation a commercial success (Hoye & Pries, Citation2009). The development of these inventions can depend upon an open innovation strategy (based on the belief that knowledgeable and creative individuals outside of the company can also contribute to achieving strategic goals and that sharing intellectual property both ways is useful to different parties in different ways). In this way, the serial entrepreneur can deliver more high-quality innovation. An open innovation strategy and a culture of open innovation developed and promoted by top management motivates serial entrepreneurs to develop innovations (Yun et al., Citation2019).

Surprisingly, research has found an inverse relationship between innovativeness and new venture success (Boyer & Blazy, Citation2014; Hyytinen et al., Citation2015; Reid & Smith, Citation2000). Although serial entrepreneurs often change industries due to their innovativeness (McGrath & MacMillan, Citation2000), serial entrepreneurs who show the greatest innovativeness fail in one industry and attempt a new venture in a different industry (Eggers & Song, Citation2015). Successful serial entrepreneurs typically remain within their industry and obtain economic success through less innovative performance. The more familiar the serial entrepreneur is with their industry, the lesser their innovative performance (Lahiri & Wadhwa, Citation2020).

Topic 3: Entrepreneurial strategy

As noted, serial entrepreneurship is the ending of one venture in order to start a new venture. Research has examined the entrepreneurial strategy of entry and reentry decisions of serial entrepreneurs, with a significant portion of this literature focusing on the failure of serial entrepreneurs and their subsequent new venture (Amaral et al., Citation2011; Stam et al., Citation2008). Research into reentry following the failure of a new venture focuses on variables such as the experience of the entrepreneur and what they have learned from their experience, their career stage and age, and psychological constructs (such as resilience, motivation, and degree of mindfulness), with mixed and contradictory results (Tipu, Citation2020). For example, entrepreneurs who had failed were less likely to reenter the market, moderated by higher education and employment experience (Amaral et al., Citation2011). Conversely, other research results suggest that failed entrepreneurs are more likely to restart than successful entrepreneurs (Nielsen & Sarasvathy, Citation2016). Hence, there is much more work to be done in this research stream.

Other studies on entrepreneurial strategy have focused on the export tactic, utilizing the human capital theory, and the results of these experiments suggest that portfolio entrepreneurs possess greater exporting intensity than serial entrepreneurs (Robson et al., Citation2012). As an exit strategy, young corporations owned by serial entrepreneurs are more likely to be sold. This research is of interest as it suggests that entrepreneurs do not want to grow and rarely innovate beyond their first capability, implying that money was not their motivation when starting their new venture. Thus, the value of ventures sold by serial entrepreneurs’ is illustrated by intellectual property rights, high-quality innovation, and employment growth (Cotei & Farhat, Citation2017).

Research further examined serial entrepreneurs’ approaches to strategic decision-making in identifying new ventures. Beyond identifying an opportunity, both entrepreneurial and managerial talent is required to successfully implement strategy, especially in foreign markets (Corbett, Citation2005; Weber & Tarba, Citation2014). Exporting is the first stage in an international strategy. Firms with no prior international experience tend to have small export revenues with short-term losses, which have repercussions on the success of their domestic operations, leading to better performance prior to their strategy of exporting to international markets (Amiti & Weinstein, Citation2011; Bellone et al., Citation2010). However, this research suggests that serial entrepreneurs, due to their strategic- and generative-based cognitive agility, are more successful when entering foreign markets (Cope, Citation2005; Vaillant & Lafuente, Citation2019).

Topic 4: Performance

Although detailed studies are lacking regarding serial entrepreneurship and performance, the studies that have been conducted have often had mixed results (for example, Eggers & Song, Citation2015; Gruber et al., Citation2008; Lafontaine & Shaw, Citation2016; Paik, Citation2014; Toft-Kehler et al., Citation2014) or have demonstrated no performance differences between serial entrepreneurs and those with no history (Iacobucci et al., Citation2004). Past research based on the theories of cognition and generative learning suggests that serial entrepreneurs achieve better performance with each new venture (Cope, Citation2005). In contrast, some research has suggested that, due to hubris and selective learning, future ventures do not perform as well (Hayward et al., Citation2010). Other pieces of research focusing only on previous failed ventures by serial entrepreneurs suggests that entrepreneurs learn from their mistakes and go on to do better in the future (Parker, Citation2013; Shepherd, Citation2003).

Focusing on the serial entrepreneur’s experience and their ability to learn from these, some researchers find no relationship with performance (Alsos & Kolvereid, Citation1998), while other researchers suggest the existence of a nonlinear relationship (Toft-Kehler et al., Citation2014; Ucbasaran et al., Citation2009). However, recent research confirms that there is no overwhelming evidence to suggest a correlation between past entrepreneurial experience and subsequent entrepreneurial performance (Valliant & Lafluente, 2018). However, this may be due to a conflict or lack of certain explanatory variables, as suggested in research on failed versus successful new ventures (Sarasvathy et al., Citation2013). When the innovation variable is explored for serial entrepreneurs, research suggests an inverse relationship between innovation and economic performance (Hyytinen et al., Citation2015).

Other performance research has suggested that serial entrepreneurs have better sales and productivity figures (K. Shaw & Sørensen, Citation2019). These researchers focused on serial entrepreneurs in Denmark found that their second firm had 55% higher sales figures than their first firm. Still, they could not find a significant relationship between serial entrepreneurs’ traits (that is, education, age, or past success as wage earners) and performance. The key to high performance for serial entrepreneurs is the team they work with, which shows that entrepreneurs must have entrepreneurial and managerial capabilities (Weber & Tarba, Citation2014). The functional diversity of the team developed by the serial entrepreneur has been shown to advance a firm’s performance, as the team is stronger and better able to develop strategies and tactics when future issues arise (Barringer & Jones, Citation2004; Kirschenhofer & Lechner, Citation2012).

Geographical context

Most of the research on serial entrepreneurship has been conducted within Europe, Asia, and North America; however, some research articles explore serial entrepreneurship in other geographical settings. Supporting Eggers and Song (Citation2015), research in Finland suggests that serial entrepreneurs utilize their past knowledge when starting a new business in a different industry (Kuuluvainen, Citation2010). As these serial entrepreneurs are not ingrained in their new industry, they are able to think outside of the box and develop innovative practices.

International research has focused on serial entrepreneurs’ characteristics and has found that serial entrepreneurs in Australia were generally male, relatively well educated, aged between 30 and 49, born locally, and came from a family who was also entrepreneurs (Schaper et al., Citation2007). Research in India suggests that to be a successful serial entrepreneur, one should have entrepreneurial capabilities – specifically, the ability to develop strong entrepreneurial teams (Kumar, Citation2012). A study in China suggested that serial entrepreneurs were superior at developing networks, better at managing than new entrepreneurs, but did not demonstrate better levels of performance (Li et al., Citation2009).

The serial entrepreneurship literature stream concerning failure has been tested in international markets as well. Using a theoretical foundation of attribution theory, research in Uganda found serial entrepreneurs were less successful in future ventures if they thought their failure was due to their lack of ability (Sserwanga & Rooks, Citation2014). In Ghana, serial entrepreneurial failure caused stigmatization and fear of future failure, focusing on external factors such as national policy barriers (Amankwah-Amoah, Citation2018). Other research in Ghana explored why serial entrepreneurs failed and suggested that rivals’ active use of negative rumors and misinformation could affect serial entrepreneurs’ new ventures to such an extent that they would fail (Amankwah‐Amoah et al., Citation2018).

Existing research methodologies

The serial entrepreneurship research domain has been investigated using both quantitative and qualitative approaches. Accordingly, access to data through Global Entrepreneurship Monitor (Simmons et al., Citation2014) or country-level datasets, such as the panel study of income dynamics for the USA (Parker, Citation2013) or Quadros de Pessoal for Portugal (Amaral et al., Citation2011), in addition to offering researchers the opportunity to collect data from different sectors and industries (Hyytinen & Ilmakunnas, Citation2007), allow scholars to dig deeper when investigating serial entrepreneurs’ attitudes, learning processes, performance, and other factors. Essentially, quantitative methodological approaches, such as piece-wise constant hazard function (Amaral et al., Citation2011), Cox proportional-hazards model (De Jong & Marsili, Citation2015), and other regression and multivariate models, are used in order to assess the significance and importance of factors such as characteristics (Westhead & Wright, Citation1998), competence, and overall performance (Toft-Kehler et al., Citation2014). Qualitative methods, like interviews, case studies, comparative case studies, and grounded theory approaches, have been used to reveal the underpinnings motivations of serial entrepreneurs – their attitudes, perceptions, and strategic approaches, among others. For example, Engel et al. (Citation2020), using the think-aloud verbal protocol and semi-structured interviews, uncovered the differences in naming ventures between novice and experienced entrepreneurs. Kuuluvainen (Citation2010), based on the case of a young Finish serial entrepreneur, revealed the impact of thinking outside of the box on entrepreneurial experience.

Discussion and future research agenda

Through our research, we have identified several future avenues of research that could shape the field’s research agenda (see : the spatial map). We have highlighted the gaps in current academic literature and have structured the flowing section according to the main theoretical focus around which these gaps were established, starting with the diversity theory.

Future research avenues regarding diversity theory

While it is true that serial entrepreneurs are predisposed to starting over again (Baù et al., Citation2017), there is still a huge gap in our current understanding of how this attitude may be hindered or boosted by individual characteristics, contingencies, and diversities (Barnir, Citation2014; Simmons et al., Citation2019). This stream of research should address how formal and informal institutions may affect serial entrepreneurship regarding gender, household roles, race, nationality, sexual orientation, faith, (in)ability, diversity, and “otherness” in general.

Some evidence of the potential impact of this has already been revealed in relation to the existence of a gender gap in serial entrepreneurship. For example, Brush et al. (Citation2009) referred to more women-specific elements of the informal institutional environment, such as the concept of “motherhood,” while Cunningham (Citation2001) noted societal expectations about women, for example, household role expectations. Hence, possible future analyses could compare cross-country cultural differences in terms of national culture values, for example, masculine/feminine values, uncertainty avoidance, power distance, individualism/collectivism, short/long-term orientation, and indulgence.

Similarly, a large body of literature exists on how other formal institutions, tasks, and general environments may influence entrepreneurs’ decisions and behaviors, especially women entrepreneurs (Brush et al., Citation2009; Cetindamar et al., Citation2012). However, this consideration is completely focused on female serial entrepreneurs. To offer explicative references, more studies should address the role of the educational system (Mehtap et al., Citation2017); industry logics (Lahiri & Wadhwa, Citation2020); economic development, and legislative framework at a “macro level” and dedicated funding and support opportunities at a “meso level” (Brush et al., Citation2009), economic development (Carbonara et al., Citation2020), and financial system development (VCs, business angels, entrepreneurial finance instruments) (Zhang, Citation2019).

Diversity and disadvantaged entrepreneurship (De Clercq & Honig, Citation2011; Santoro et al., Citation2020) is a developing topic in the entrepreneurial debate and, for serial entrepreneurship, is in its nascent stage. According to Maalaoui et al. (Citation2020, pp. 1–2), entrepreneurial studies should pay more attention to “otherness” nuances that can be defined in terms of sociodemographic circumstances: gender, age (senior/gray entrepreneurship), nationality, and ethnic minority backgrounds or individual characteristics, attributes, and contingencies, such as refugees or immigrants, ex‐prisoners, (differently) able people, the unemployed, students, those of faith, and those of varying sexual orientations. Similar to the study of female serial entrepreneurship, future research questions should also consider how formal and informal institutional elements can impact those categories, thus opening up a new field of research on the disadvantaged and diverse serial entrepreneurship. Finally, other directions for future research that are still centered around diversity may constitute a link to the RBV theory, as serial entrepreneurs, thanks to their previous experience, resources, and learning abilities should be able to develop new and more innovative products/services (Cope, Citation2005), even though the relationship between innovation and serial entrepreneurship is not always clear (Hyytinen et al., Citation2015). However, less is known with regard to diverse entrepreneurship. For example, senior/gray entrepreneurs accumulate a tremendous amount of knowledge and contacts in the industry in which they have previously worked as employees/professionals (Harms et al., Citation2014). This can become a significant advantage when it comes to the creation of successive ventures. Similarly, immigrant entrepreneurs who mainly target their ethnic community may find advantages to increasing human capital, having their business contacts understand their target markets (Dabić et al., Citation2020). In a similar vein, disabled entrepreneurs may craft ventures to address customers’ specific needs in similar circumstances (De Clercq & Honig, Citation2011). Their ability to uniquely understand these contexts represents an advantage for their potential serial entrepreneurship.

Future research avenues regarding entrepreneurial strategy

The second stream of research focuses on obtaining a better understanding of serial entrepreneurs’ exit and reentry strategies, using more insights from RBV and KBV theories. Firstly, the resources, experiences, and skills of serial entrepreneurs impact their next venture and their performance (Carbonara et al., Citation2020; Ucbasaran et al., Citation2009; Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2008). However, the specific elements of this broad set are less defined. For example, Zhang (Citation2011) asserts that only specific entrepreneurial experience in VC-backed companies assures a better endowment – in terms of VC funds – to the current organization. Thus, simply being a serial entrepreneur with previous general experience is not crucial. This simple example calls for further studies on relevant factors that may affect reentry strategies and their outcomes.

Secondly, the prevalent approach adopted by serial entrepreneurship studies sees these strategies, pertinent resources, and knowledge bases employed mostly in terms of individual consequences (for example, Tipu, Citation2020; Ucbasaran et al., Citation2009). Using a comprehensive framework elaborated for entrepreneurial failure instead (Klimas et al., Citation2021), we argue that more attention should be paid to different outcomes, direct, indirect, long‐term ones, and time progression. The former is probably the most frequently investigated/experienced category, and it comprehends economic, psychological, and social consequences. However, more emphasis should be put on the other two categories to understand the role of resources, skills, and the knowledge of an entrepreneur in reentering the field (Wiklund & Shepherd, Citation2008). Indirect effects occur only when direct effects are fully “digested.” Specifically, they relate to grief, reflecting on learning, and proposing strategies for recovery (Shepherd, Citation2003). Much more should be done to facilitate an understanding of how serial entrepreneurs experience these three outcomes and phases, establishing the personal characteristics and contingencies, resources and knowledge, or institutional factors that may influence the process (Baù et al., Citation2017; Klimas et al., Citation2021). Finally, long-term outcomes can be analyzed at an individual, organizational (future venture), and environmental level. Particularly from a pure KBV perspective, the production and accumulation of knowledge are critical for its subsequent distribution and use (Bozeman & Mangematin, Citation2004). Yet, if accumulated stocks of knowledge are deemed to help deal with environmental contingencies internally, such as processing information and making decisions (Minniti & Bygrave, Citation2001; Sassetti et al., Citation2018), it would be interesting to verify whether or not this is also true when it comes to dealing with the environmental consequences of an exit strategy, thus managing external processes and relationships with network partners, competitors, and stakeholders.

In addition to these consequences, types of and reasons for an entrepreneurial exit may influence reentry modality and odds. DeTienne (Citation2010) identifies three main exit strategies: firm exit, founder exit, or both. Similarly, reasons for leaving may be due to alternative options or new business opportunities, calculative options arising from evaluating the quality and value of the current venture or, finally, the normative support of the surrounding environment (DeTienne, Citation2010). The entrepreneur’s characteristics may also influence these decisions (DeTienne & Cardon, Citation2012); for example, more educated serial entrepreneurs may exit by selling their business when they have a good chance of making a profit. This means that necessary resources, skills, and experiences play a role. So far, however, academic debates lag when it comes to studying these factors (Carbonara et al., Citation2020).

While RBV and KBV are more inwardly oriented, that is, more focused on the specific firm or entrepreneur and its/their resources and knowledge, a complementary approach could analyze entrepreneurial exit and reentry strategies in light of environmental contingencies, integrating the institutional theory that plays a role in entrepreneurial strategy (Carbonara et al., Citation2020; Cetindamar et al., Citation2012). For example, transaction economic logic may affect the decisions and outcomes of serial entrepreneurs differently. This would also open up an interesting debate regarding regional or industry development.

Future research avenues regarding technopreneurship and innovation

The third stream of research relates to innovation in serial entrepreneurship analyzed in two directions: one pertinent to the serial entrepreneur, thus internal, calling for better integration of the topic with the capital theory; and one external and related to environmental contingencies, thus calling for integration with the institutional theory.

Unlike portfolio entrepreneurs, who are innovators, serial entrepreneurs tend to be less innovative (Carbonara et al., Citation2020). For example, when serial entrepreneurs remain in the same industry, due to their accumulated human and social capital, they tend to exploit opportunities rather than explore new ones (Lahiri & Wadhwa, Citation2020). As a result of their accumulated capital in a certain industry, serial entrepreneurs dwell more on stable but profitable ventures at the expense of innovative performance. Nevertheless, it is also true that some of these seminal results do not consider, for example, the reasons behind an entrepreneurial exit.

Another research area is that of open innovation strategy. On the one hand, some studies have demonstrated an inverted U-shaped relationship between open innovation strategy adoption and innovation performance (Laursen & Salter, Citation2006). On the other hand, open innovation seems to stimulate serial entrepreneurship as, through either outside-in or inside-out strategies, entrepreneurs can become more aware of new opportunities and be more confident in their external environment, accumulating human and social capital (Yun et al., Citation2019).

The majority of studies on innovation in serial entrepreneurship merely consider innovative performance, thus only examining the outputs of the process (for example, patents, as in Lahiri & Wadhwa, Citation2020). However, being innovative involves many more strategic and organizational decisions, such as the business model and its changes (Corbo et al., Citation2020; Pizzi et al., Citation2020). We refer specifically to the business model as it is able to comprehensively capture an entire entrepreneurial action through its ties to the complex relationship between the creation and appropriation of value for a company (Zott et al., Citation2011). Some evidence suggests that serial entrepreneurs may have a different cognitive approach to the design of business models (Malmström et al., Citation2015). Thus, we consider it important to relate human capital and the ability of serial entrepreneurs to innovative business models, as scholarly literature is scant in this regard.

Our research suggests that further exploration is required when it comes to the impact of the environment on the innovative abilities of serial entrepreneurs. Business model innovation may occur not only for strategic and entrepreneurial marketplace changes (Zott et al., Citation2011) and when adapting to new and emergent contingencies (Foss & Saebi, Citation2018). In recent years, one of the most prominent phenomena is the digital revolution or 4.0 era, which has affected society and, consequently, organizations and their business models (Caputo et al., Citation2021; Fakhar-Manesh et al., Citation2021). The advent of new technologies, such as the Internet of Things and the heavy use of artificial intelligence, have substantially changed how knowledge is managed within organizations (Vlačić et al., Citation2021) and entrepreneurial activities (Obschonka & Audretsch, Citation2020). As serial entrepreneurs have higher levels of imaginativeness (McMullen & Kier, Citation2017), they should also be able to innovate rapidly and adapt to such futuristic paradigms.

However, the external environment analysis cannot be limited to only the societal movements of the digital transformation. The very definition of an ecosystem relates to an environment that conceives innovation-based ventures (Spigel, Citation2017). Thus, we call for more studies on how formal and informal institutions impact the innovativeness of serial entrepreneurs.

Moving from one industry to another is common for serial entrepreneurs (Eggers & Song, Citation2015; McGrath & MacMillan, Citation2000). This mitigates their tendency to prefer exploitation over exploration (Carbonara et al., Citation2020; Lahiri & Wadhwa, Citation2020). However, there is no evidence to suggest that such shifts are not also influenced by industry logic. For example, in bio-tech, open innovation strategies and serial entrepreneurship are the “genetic code” of the industry (Dutton, Citation2009). Does this embeddedness alter previous considerations regarding innovative performance?

Future research areas regarding serial entrepreneurship and sustainability

For the last two future research avenues, we focus on the research streams that did not emerge in the scientific map of the field (), as academic literature is rendered silent on these topics. The first aspect that we believe should be added to discussions of serial entrepreneurship is the concept of sustainability. Increasingly, technology is at the service of greener, more socially inclusive, economically viable solutions. Thus, we can link sustainability to the innovation topic and business model innovation (Caputo et al., Citation2021; Pizzi et al., Citation2020). In actuality, social, serial or habitual entrepreneurship are not rare in practice, as social entrepreneurs work using a trial-and-error process to deliver maximum value (E. Shaw & Carter, Citation2007). However, the motivation to create a new venture in social entrepreneurship is different, so the academic debate needs to investigate the specific logic behind this type of serial entrepreneurship, although there are cases in practice.

Future research avenues regarding serial entrepreneurship and the COVID-19 pandemic

As the entire marketplace has been affected – in some ways, permanently – by the SARS-COV-2 (COVID-19) pandemic, the need for entrepreneurial flexibility and adaptability is growing. Considering the fact that the true impact of the pandemic cannot be estimated at the moment, serial entrepreneurs’ aptitude for trying again (Baù et al., Citation2017) and their capacity to adapt may serve as a revitalization factor. In addition, recent research reveals that ecosystem quality has a much smaller impact on the venture survival of serial entrepreneurs (Vedula & Kim, Citation2019). Hence, serial entrepreneurs’ behavioral addiction toward entrepreneurship (Spivack et al., Citation2014) and their capacity to recognize business opportunities (Urban, Citation2009) may prove to be of assistance in times to come as society is facing multiple waves of lockdowns and is trying out new ways of doing business.

History shows that marketplace disruptions have recurrent tendencies (Donthu & Gustafsson, Citation2020) and that the revitalization process is often uneven across markets and categories.

Hence, as the global business environment changes, policymakers have the opportunity to enhance institutional support to entrepreneurial activities and provide a favorable setting for entrepreneurial nomads (aka digital nomads). Accordingly, further improvements in digital infrastructure and stronger innovation support, in line with stable institutions, provide an opportunity for entrepreneurs to overcome the limitations caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.

Building upon these notions, future research could investigate serial entrepreneurs’ opportunity recognition and performance compared with novice or portfolio entrepreneurs under the new-normal context and the changing nature of ecosystem quality. In addition, future research could shed light on how serial entrepreneurs navigate political and social changing strategies; the extent to which serial entrepreneurs influence institutional policies and their role in developing new institutions; how serial entrepreneurs overcome limitations caused by the pandemic; and the extent to which their experiences and cognitions play a role in their ability to overcome environmental stressors.

Implications for practice

Our research provides a significant number of implications for practitioners. Many individuals wish to begin their new venture and subsequently start their second venture. One of our key takeaways is our investigation as to how serial entrepreneurs discover their next venture opportunities through solutions to specific problems, listening to customers’ wants/needs, being creative in identifying latent business opportunities, and realizing that opportunities rarely come immediately, but rather emerge across a series of events.

Many individuals may not wish to be entrepreneurs due to the very high risk of failure. Our research does not contradict past research but rather suggests that failure may not be a bad thing, as those who then start a second new venture have a greater chance of better performance. Serial entrepreneurs learn from previous mistakes and implement better business plans. Our research suggests that successful serial entrepreneurs (a term also applicable to habitual and first-time entrepreneurs) have a business plan mental schematic and can value innovative marketplace options realistically. Over time, the serial entrepreneur develops a generative-based cognitive schema, allowing them to evaluate implementable opportunities.

VCs are interesting phenomena to serial entrepreneurs. They like to invest in serial entrepreneurs and only do so if the new venture has intellectual property rights, high-quality innovation, and opportunities for employment growth. Furthermore, VCs seek degrees of profit that encourage the serial entrepreneur to sell their new venture and begin another.

Two other key areas of research pertaining to practicing serial entrepreneurs are that of the entrepreneurial team and the age and career progression of the individual. Our research suggests that the entrepreneur is important but that the team and the venture’s management are critical. A diverse team will support the new venture and assist as the marketplace, customer preferences, and value propositions change. The diverse team will be able to manage all of the various nuances and develop tactics and strategies for success. Entrepreneurs can start a new venture early in their careers and then be more successful later. Entrepreneurs who may have failed early (or even those who were successful) can then start new ventures later in their careers and succeed.

Conclusion

The research into serial entrepreneurship is nascent, and much remains for researchers to explore. Even though the research stream on entrepreneurship has received deserved focus by academics, the serial entrepreneurs subfield was not explored enough, although many entrepreneurs are serial entrepreneurs (Lafontaine & Shaw, Citation2016). Thus, this article provides a timely and necessary review of the literature on serial entrepreneurship, intending to consolidate what we know about serial entrepreneurs and their key characteristics and inspire the domain’s future research. In line with the research questions that guided this review, we acknowledge that one key reason that many researchers avoid in this stream of literature is the degree of difficulty linked to the measurement and accumulation of data in this vein. To follow a serial entrepreneur can take many years. Making comparisons between a previous and current venture or comparing an entrepreneur to who they were previously may result in spurious correlations. The intent of an initial venture may be very different from the next venture, and so on.

The performance of differing ventures initiated by an entrepreneur over time would be difficult to ascertain unless they were considered failures (where the firm ceases operation). This could be one reason why academic literature focuses on serial entrepreneurs and their subsequent ventures after failure. Performance is also difficult to measure, as many entrepreneurs start a business, not for monetary gain but for personal satisfaction. They rarely grow and fail to innovate beyond their initial starting move.

The variables required for successful research on serial entrepreneurship are varied, and many units of analysis are required: the entrepreneur, the new venture, past new ventures, the new venture team, outside influences (VC), the owner’s immediate family pressures, age and career progression, education, and so on. The field is very difficult to research, and the individual characteristics of the serial entrepreneur have not shown consistent application. Although past research suggests that the next venture will be more successful if an entrepreneur can overcome the loss of a past failure, no research has been conducted on how one overcomes this overwhelming situation.

The serial entrepreneurship stream must continue to borrow from entrepreneurship literature regarding first-time entrepreneurs and habitual entrepreneurs, including portfolio entrepreneurs. Lessons for success can be learned from the differences between these types of individuals, strategies, and techniques. There are many overlaps in these research streams, and researchers can continue to apply comparisons when investigating and focusing on the serial entrepreneur. Other areas of focus include those that support and assist in new ventures. Current research is exploring new venture teams and eventual success. However, others in the network of external relationships (that is, financial consultants, lawyers, networks of other entrepreneurs and established businesses, banks, and VCs) can also provide support and guidance.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (56.2 KB)Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article is available online at https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2021.1969657.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ajzen, I. (1991). The theory of planned behavior. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 50(2), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T

- Alsos, G. A., & Kolvereid, L. (1998). The business gestation process of novice, serial, and parallel business founders. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 22(4), 101–114. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879802200405

- Amankwah-Amoah, J. (2018). Revitalising serial entrepreneurship in sub-Saharan Africa: insights from a newly emerging economy. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 30(5), 499–511.

- Amankwah‐Amoah, J., Antwi‐Agyei, I., & Zhang, H. (2018). Integrating the dark side of competition into explanations of business failures: Evidence from a developing economy. European Management Review, 15(1), 97–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12131

- Amaral, A. M., Baptista, R., & Lima, F. (2011). Serial entrepreneurship: Impact of human capital on time to re-entry. Small Business Economics, 37(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-009-9232-4

- Amiti, M., & Weinstein, D. E. (2011). Exports and financial shocks. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 126(4), 1841–1877. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjr033

- Autio, E., Kenney, M., Mustar, P., Siegel, D., & Wright, M. (2014). Entrepreneurial innovation: The importance of context. Research Policy, 43(7), 1097–1108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2014.01.015

- Baù, M., Sieger, P., Eddleston, K. A., & Chirico, F. (2017). Fail but try again? The effects of age, gender, and multiple–owner experience on failed entrepreneurs’ re-entry. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(6), 909–941. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12233

- Barnir, A. (2014). Gender differentials in antecedents of habitual entrepreneurship: Impetus factors and human capital. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 19(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1142/S1084946714500010

- Baron, R. A., & Ensley, M. D. (2006). Opportunity recognition as the detection of meaningful patterns: Evidence from comparisons of novice and experienced entrepreneurs. Management Science, 52(9), 1331–1344.

- Baron, R. A., & Ward, T. B. (2004). Expanding entrepreneurial cognition's toolbox: Potential contributions from the field of cognitive science. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 28(6), 553–573. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2004.00064.x

- Barringer, B. R., & Jones, F. F. (2004). Achieving rapid growth: Revisiting the managerial capacity problem. Journal of Developmental Entrepreneurship, 9(1), 73–87.

- Becker, G. S. (1962). Investment in human capital: A theoretical analysis. Journal of Political Economy, 70(5, Part 2), 9–49. https://doi.org/10.1086/258724

- Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Schiavo, S. (2010). Financial constraints and firm export behavior. World Economy, 33(3), 347–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01259.x

- Bem, D. J. (1995). Writing a review article for psychological bulletin. Psychological Bulletin, 118(2), 172–177. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.118.2.172

- Bendixen, M. T. (1995). Compositional perceptual mapping using chi‐squared trees analysis and correspondence analysis. Journal of Marketing Management, 11(6), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.1995.9964368

- Boyer, T., & Blazy, R. (2014). Born to be alive? The survival of innovative and non-innovative French micro-start-ups. Small Business Economics, 42(4), 669–683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9522-8

- Bozeman, B., & Mangematin, V. (2004). Editor’s introduction: Scientific and technical human capital. Research Policy, 33(4), 565–568. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2004.01.004

- Brush, C. G., De Bruin, A., & Welter, F. (2009). A gender-aware framework for women’s entrepreneurship. International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship, 1(1), 8–24. https://doi.org/10.1108/17566260910942318

- Butticè, V., Colombo, M. G., & Wright, M. (2017). Serial crowdfunding, social capital, and project success. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 41(2), 183–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12271

- Bygrave, W. D., & Hofer, C. W. (1992). Theorizing about entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 16(2), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225879201600203

- Caputo, A., Pizzi, S., Pellegrini, M. M., & Dabić, M. (2021). Digitalization and business models: Where are we going? A science map of the field. Journal of Business Research, 123, 489–501. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.09.053

- Carbonara, E., Tran, H. T., & Santarelli, E. (2020). Determinants of novice, portfolio, and serial entrepreneurship: An occupational choice approach. Small Business Economics, 55(1), 123–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00138-9

- Casprini, E., Dabić, M., Kotlar, J., & Pucci, T. (2020). A bibliometric analysis of family firm internationalization research: Current themes, theoretical roots, and ways forward. International Business Review, 29(5), 101715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101715

- Cetindamar, D., Gupta, V., Karadeniz, E., & Egrican, N. (2012). What the numbers tell: The impact of human, family and financial capital on women and men’s entry into entrepreneurship in Turkey. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 24(1–2), 29–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2012.637348

- Chandler, G. N., & Hanks, S. H. (1998). An examination of the substitutability of founders human and financial capital in emerging business ventures. Journal of Business Venturing, 13(5), 353–369. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00034-7

- Cope, J. (2005). Toward a dynamic learning perspective of entrepreneurship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 373–397. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00090.x

- Cope, J. (2011). Entrepreneurial learning from failure: An interpretative phenomenological analysis. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(6), 604–623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2010.06.002

- Cope, J., & Watts, G. (2000). Learning by doing–an exploration of experience, critical incidents and reflection in entrepreneurial learning. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behavior & Research, 6(3), 104–124. https://doi.org/10.1108/13552550010346208

- Corbett, A. C. (2005). Experiential learning within the process of opportunity identification and exploitation. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 29(4), 473–491. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2005.00094.x

- Corbo, L., Mahassel, S., & Ferraris, A. (2020). Translational mechanisms in business model design: Introducing the continuous validation framework. Management Decision, 58(9), 2011–2026. https://doi.org/10.1108/MD-10-2019-1488

- Cotei, C., & Farhat, J. (2017). The M&A exit outcomes of new, young businesses. Small Business Economics, 50(3), 545–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-017-9907-1

- Cunningham, W. (2001). Breadwinner or caregiver? How household role affects labor choices in Mexico. Policy Research Working Paper No. 2743. The World Bank, Washington, D.C

- Cyert, R. M., & March, J. G. (1963). A behavioral theory of the firm (Vol. 2 (4)). Armonk, NY: M.E. Sharpe.

- Dabić, M., Vlačić, B., Paul, J., Dana, L. P., Sahasranamam, S., & Glinka, B. (2020). Immigrant entrepreneurship: A review and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 113, 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.03.013

- Davidsson, P., & Honig, B. (2003). The role of social and human capital among nascent entrepreneurs. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(3), 301–331. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(02)00097-6

- De Clercq, D., & Honig, B. (2011). Entrepreneurship as an integrating mechanism for disadvantaged persons. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 23(5–6), 353–372. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.580164

- De Jong, J. P., & Marsili, O. (2015). Founding a business inspired by close entrepreneurial ties: Does it matter for survival? Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1005–1025. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12086

- DeTienne, D. R. (2010). Entrepreneurial exit as a critical component of the entrepreneurial process: Theoretical development. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(2), 203–215. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2008.05.004

- DeTienne, D. R., & Cardon, M. S. (2012). Impact of founder experience on exit intentions. Small Business Economics, 38(4), 351–374. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9284-5

- DeTienne, D. R., & Chirico, F. (2013). Exit strategies in family firms: How socioemotional wealth drives the threshold of performance. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 37(6), 1297–1318. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12067

- Donthu, N., & Gustafsson, A. (2020). Effects of COVID-19 on business and research. Journal of Business Research, 117, 284–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.06.008

- Dutton, G. (2009). Emerging biotechnology clusters: Experienced management and VCs and a serial entrepreneurial culture provide critical keys to success. Genetic Engineering and Biotechnology News, 29(9). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(97)00122-7

- Eggers, J. P., & Song, L. (2015). Dealing with failure: Serial entrepreneurs and the costs of changing industries between ventures. Academy of Management Journal, 58(6), 1785–1803. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2014.0050

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21(10‐11), 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-0266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

- Engel, Y., van Werven, R., & Keizer, A. (2020). How novice and experienced entrepreneurs name new ventures. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1738820

- Ensign, P. C., & Farlow, S. (2016). Serial entrepreneurs in the Waterloo ecosystem. Journal of Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 5(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13731-016-0051-y

- Fakhar-Manesh, M., Pellegrini, M. M., Marzi, G., & Dabić, M. (2021). Knowledge management in the fourth industrial revolution: Mapping the literature and scoping future avenues. IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management, 68(1), 289–300. https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2019.2963489

- Ferreira, J. J., Fernandes, C. I., & Kraus, S. (2019). Entrepreneurship research: Mapping intellectual structures and research trends. Review of Managerial Science, 13(1), 181–205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11846-017-0242-3

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2018). Business models and business model innovation: Between wicked and paradigmatic problems. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 9–21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.07.006

- Fu, K., Larsson, A. S., & Wennberg, K. (2018). Habitual entrepreneurs in the making: How labour market rigidity and employment affects entrepreneurial re-entry. Small Business Economics, 51(2), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0011-y

- Gaglio, C. M., & Katz, J. A. (2001). The psychological basis of opportunity identification: Entrepreneurial alertness. Small Business Economics, 16(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1011132102464

- Gielnik, M. M., Zacher, H., & Schmitt, A. (2017). How small business managers’ age and focus on opportunities affect business growth: A mediated moderation growth model. Journal of Small Business Management, 55(3), 460–483. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12253

- Gifi, A. (1990). Nonlinear multivariate analysis. Wiley.

- Gimeno, J., Folta, T. B., Cooper, A. C., & Woo, C. Y. (1997). Survival of the fittest? Entrepreneurial human capital and the persistence of underperforming firms. Administrative Science Quarterly, 42(4), 750–783. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393656

- Gonzalez-Loureiro, M., Kiessling, T., & Dabic, M. (2015). Acculturation and overseas assignments: A review and research agenda. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 239–250. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijintrel.2015.05.003

- Grant, R. M. (2002). The knowledge-based view of the firm. In C. W. Choo & N. Bontis (Eds.), The strategic management of intellectual capital and organizational knowledge (pp. 133–148). Oxford University Press.

- Gruber, M., Macmillan, I. C., & Thompson, J. D. (2008). Look before you leap: Market opportunity identification in emerging technology firms. Management Science, 54(9), 1652–1665. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1080.0877

- Gudmundsson, S. V., & Lechner, C. (2013). Cognitive biases, organization, and entrepreneurial firm survival. European Management Journal, 31(3), 278–294. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2013.01.001

- Guerrero, M., & Peña-Legazkue, I. (2019). Renascence after post-mortem: The choice of accelerated repeat entrepreneurship. Small Business Economics, 52(1), 47–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0015-7

- Hair, J. H., Jr., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black, W. C. (1998). Multivariate data analysis (5th ed.). Prentice-Hall.

- Harms, R., Luck, F., Kraus, S., & Walsh, S. (2014). On the motivational drivers of gray entrepreneurship: An exploratory study. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 89, 358–365. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.08.001

- Hayward, M. L. A., Forster, W. R., Sarasvathy, S. D., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). Beyond hubris: How highly confident entrepreneurs rebound to venture again. Journal of Business Venturing, 25(6), 569–578. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.03.002

- Hoffman, D. L., & De Leeuw, J. (1992). Interpreting multiple correspondence analysis as a multidimensional scaling method. Marketing Letters, 3(3), 259–272. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00994134

- Hogarth, R. M., & Karelaia, N. (2012). Entrepreneurial success and failure: Confidence and fallible judgment. Organization Science, 23(6), 1733–1747. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0702

- Hogg, M., & Abrams, D. (1988). Social identification. Routledge.

- Hoye, K., & Pries, F. (2009). ‘Repeat commercializes,’the ‘habitual entrepreneurs’ of university-industry technology transfer. Technovation, 29(10), 682–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2009.05.008