ABSTRACT

Although a considerable amount of literature shows how entrepreneurs develop and utilize social capital to create and grow their ventures, there is scant learning on how nascent entrepreneurs with few ties actually create and utilize social capital to help turn their early ideas into ventures. This paper reveals the role of relational leadership in social capital development and shows how it enhances persistence among very early-stage nascent entrepreneurs, even when they have no employees or partners to lead. Learning from our 18-month in-depth case studies of early-stage nascent entrepreneurs in one European country is used to propose a theory of social capital development in nascent entrepreneurship. Implications for future research and for nascent entrepreneurial practice are discussed.

Video Abstract

© 2022 The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Introduction

Nascent entrepreneurs are often resource poor and lacking social ties relevant to new venture creation, especially if they are starting a business in an unfamiliar environment (Jones et al., Citation2014). Yet successfully establishing social ties (social capital sources) can lead to developing productive (social capital) resources (Coleman, Citation1990; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998) that can help entrepreneurs along their new venture creation journey. Considerable literature highlights the importance of social capital and shows that an entrepreneur’s social relationships can create productive resources (for example, Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003; De Carolis et al., Citation2009; García-Villaverde et al., Citation2018; Hughes et al., Citation2014).

Yet, scant literature provides insights into how nascent entrepreneurs who are resource poor and lacking relevant social ties go about creating social capital sources; how they then access resources from these sources; and what impact this activity has on their new venture creation journey (Gedajlovic et al., Citation2013). Gaining such insight is particularly relevant for nascent entrepreneurs who have few social relationships, such as immigrant entrepreneurs creating a new venture in their host country (Bird & Wennberg, Citation2016; Bizri, Citation2017).

This research is at the intersection of two related yet jointly under-explored topics: social capital and relational leadership. We postulate that applying relational leadership, a process of social influence in which emergent coordination and change are produced (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006), in developing social capital sources can lead to garnering relevant social capital resources which can then enhance persistence with nascent entrepreneurial efforts. Persistence, when applied contextually (Honig & Samuelsson, Citation2012), is critical to success in creating a venture (for example, Cardon & Kirk, Citation2015; Freeland & Keister, Citation2016; Stenholm & Renko, Citation2016). Examination of the leadership and entrepreneurial leadership literature shows that little if any prior research has identified such leadership behavior, and further, that few entrepreneurial leadership studies examine nascent stage entrepreneurial activity. Revealing how persistence can be created and maintained through relational leadership practices can also inform entrepreneurship scholarship and practice more broadly.

We examine this under-developed area of the social capital and entrepreneurship literature using an induction-driven approach (Patton, Citation2015), via 18-month in-depth case studies with a purposive sample of immigrant nascent entrepreneurs in a Western European country. This sample is ideal for our study, as lack of an established network in their host country makes development of social capital sources (social connections with those who may provide needed resources for start-up) among this group highly dynamic. Thus, we are able to uncover and track the dynamics of social capital development and how these interactions impact nascent entrepreneurship and new venture creation. That relational leadership was important at this very early stage in entrepreneurship – when there were no partners or employees to lead – was unexpected, yet the behaviors we observed are best explained and represented by the relational leadership concept.

Building on our observation of immigrant nascent entrepreneurs enacting relational leadership in the early stages of new venture creation we induce the outline of a theory of social capital development in nascent entrepreneurship, which proposes that relational leadership impacts social capital resource acquisition and persistence in entrepreneurial efforts. Our qualitative, longitudinal study of early-stage nascent entrepreneurs makes three contributions. First, we contribute to the social capital literature by revealing how those with poor initial ties, and thus few if any social capital sources, actually go about developing them, thus addressing a gap in our understanding of the nascent entrepreneurship process of resource acquisition and resource deployment. Second, we contribute to the entrepreneurial leadership literature by showing that relational leadership is important to nascent entrepreneurs even at the earliest stages of nascent venture creation activity, because it can help to acquire resources and motivate persistence in entrepreneurial efforts. Third, we contribute to entrepreneurship practice by informing entrepreneurship education and training in the importance of developing relational leadership among nascent entrepreneurs.

Social capital theory and entrepreneurship

This conceptual and empirical research provides insight into the role of social capital in the nascent entrepreneurial process. Our understanding of social capital sources, social capital resources and the intervening processes between social relationships and outcomes is still lacking (Anderson, Citation2008; Smith et al., Citation2019). Some have emphasized structural variations in the network as the key constituent parts of social capital (Baker, Citation1990; Kreiser et al., Citation2013). Others, such as Nahapiet and Ghoshal (Citation1998, p. 243), emphasize the need to examine “both the network and the assets that may be mobilized through that network”. Thus, a complete understanding of social capital requires examination of the creation and maintenance of social capital sources – the network, and the acquisition of social capital resources – the assets, in Nahapiet and Goshal’s terms. This highlights the need to examine social capital development over time, in order to understand how and when social capital sources provide social capital resources, and the potential value of sustained interaction with social capital sources (Snihur et al., Citation2017).

Much of the literature is currently hindered by an inappropriate view of social capital sources as being “static, unchanging and without costs” (Gedajlovic et al., Citation2013, p. 459). Thus, the social capital literature needs to better address nascent entrepreneurial phenomena through longitudinal studies that can uncover the dynamic interplay of two under-researched dimensions – social capital sources and social capital resources – and observe them as they happen.

A considerable amount of literature emphasizes the importance of social capital resources to entrepreneurs (Gedajlovic et al., Citation2013) and intrapreneurs (Simsek & Heavey, Citation2011), with Lin (Citation1999) highlighting knowledge and information, influence among potential stakeholders, social credentials in the community at large, and reinforcement of identity and recognition of the nascent entrepreneur. Hoang and Antoncic (Citation2003) add that social capital offers entrepreneurs access to information and advice that would otherwise be unavailable or difficult to obtain, and reputational or signaling content that reflects positively on the potential for success of a new venture. The importance of social capital to aspiring and nascent entrepreneurs specifically is supported by Davidsson and Honig’s (Citation2003) findings, showing social capital to be a strong predictor of nascency status, speed, and quantity of nascent gestation behaviors, and achieving start-up.

Recent quantitative studies have examined social capital sources and resources separately in longitudinal research (Kreiser et al., Citation2013; Newbert et al., Citation2013), and so provide some initial understanding for examination of these dimensions of social capital. Building on Hallen’s (Citation2008) work showing that many executives build new ties using existing ties, Hallen and Eisenhard (Citation2012) begin to provide more fine-grained insight into how entrepreneurs and entrepreneurial executives build new ties more efficiently through what they call “casual dating.” They also found that those with low quality ties or no ties at all have great difficulty establishing social capital sources. In sum, we have some initial understanding about how established firms develop social capital, primarily building on extant social ties; we have some initial insights into how those with established ties can efficiently create new social capital sources, primarily through “casual dating,” and we know that those who have few and no extant social ties have great difficulty establishing new social capital sources. Hence, the literature provides little insight into how nascent entrepreneurs, who are often resource poor and lacking relevant social ties, go about creating social capital sources; how they then access resources from these sources; and what impact this activity has on their entrepreneurship journey.

Relational leadership

Entrepreneurs who create a venture that employs people need to demonstrate leadership skills and competencies in order to succeed long-term. This much can be drawn with some certainty from extant literature on leadership in entrepreneurship. Beyond this, the literature is under-developed in clarifying what entrepreneurial leadership is and how it should be studied (Leitch & Volery, Citation2017), to the point that recent literature includes definitions and models of entrepreneurial leadership that exclude mention or apparent consideration of whether anyone is following or being led by the entrepreneur (for example, Simba & Thai, Citation2019). Hence, this literature may not be well suited to explaining leadership behaviors in the context of a nascent venture, one that may involve nothing more than the entrepreneur and an idea.

Unlike more traditional, top-down leadership approaches, relational leadership works through a combination of reciprocal processes, including exchange processes, influence processes, and development of shared values and interests (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). This approach is ideally suited to examining nascent entrepreneurs’ unique follower-less, unaligned context, as it represents a process of social influence in which emergent coordination, interactional influence and change are socially constructed and produced (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). To our knowledge relational leadership theory has not been used to explain social capital development during new venture creation but its focus on organizing and generating social order enacted by social interaction can be seen as akin to the process of new venture creation.

Relational leadership needs to be understood and examined in the context of two main elements – the individual’s relational self-concept and the dynamics of the socially constructed process (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). The self can be understood and examined as an “individuated and autonomous” entity and as socially constructed with and through interactions with others (Endres & Weibler, Citation2017, p. 218). Studies that investigate the entity element of self-concept of entrepreneurs include investigations of perceptions of personal attributes such as self-efficacy and its role in achieving entrepreneurial goals (for example, Ardichvili et al., Citation2003; McGee et al., Citation2009). Although the entity perspective is valuable, it can be limited to providing snapshots of self-concept perceptions without the relational context (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). A newcomer’s self-concept may be positively or negatively impacted and adjusted through interactions and communication with others in new sociocultural contexts (Kim, Citation2017) and can impact individual cross-cultural and economic adaptation. Gender, family roles and other socially and culturally constructed concepts were also found to impact the entrepreneur’s self-concept (EstradaCruz et al., Citation2019; Fauchart & Gruber, Citation2011) and new venture creation (Light & Dana, Citation2013; Neumeyer et al., Citation2019). Theoretical insights into relational self-concept demonstrate the importance of specific social and cultural influences relevant to new venture creation.

The second element of relational leadership focuses on the dynamic practice and behaviors related to exchanging, influencing and organizing (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). Researchers have examined relational leadership behavior in a variety of organizational settings and found positive associations with outcomes ranging from employee motivation and job satisfaction, creative output and financial performance (Amabile et al., Citation2004; Atwater & Carmeli, Citation2009; Banks et al., Citation2014; Gerstner & Day, Citation1997; Nembhard & Edmondson, Citation2006) to development of social capital inside established organizations (for example, Carmeli et al., Citation2009; Uhl-Bien et al., Citation2000). Researchers in entrepreneurship domain have not applied relational leadership to understanding social capital development in new venture creation but some insights into relational practices aimed at resource acquisition can be gained from studies on impression management and legitimacy building. For example, Honig and Samuelsson (Citation2012) did not find a positive link between business plans and gaining legitimacy. Fisher et al. (Citation2016) identified institutional pluralism, venture-identity embeddedness and legitimacy buffering as key enablers/disablers of legitimacy thresholds at different venture stages and Nagy et al. (Citation2012) showed how entrepreneurs’ purposeful actions can impact stakeholder’s perceptions of venture legitimacy.

Recent literature has begun to theorize on the relationality of entrepreneurial leadership, highlighting that both creative and directional entrepreneurial work happens via co-action among participants (Sklaveniti, Citation2017). Yet we find no investigation of relational leadership in settings where there is a need to undertake work and obtain resources with other people who are not obligated or financially incentivized to help. One of the strengths of relational leadership is the focus it places on relationships themselves. At its core, leadership is about fostering relations with others that enable action or achievement of common purpose (Cunliffe & Eriksen, Citation2011; Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). Relational leadership is founded on the principle that relationships create the social order, which in management terms is the organization. When an organization exists only as an idea – as in the case of a nascent entrepreneur beginning to form or exploit a potential opportunity – self-perceptions of the would-be enterprise leader become salient in actualizing the organization. In relational leadership terms this highlights the critical role of the leader’s self-perception relative to intended followers and the intended followers’ perception of the would-be leader (Hollander, Citation1995). Hence, overall, the relational approach to leadership appears well suited to examining the contexts we encounter with nascent entrepreneurs, where development of relationships might be the only obtainable asset in the early stages, and will thus shape the entrepreneur and organization that emerges.

Persistence in new venture creation

Entrepreneurship is a challenging, uncertain and risky endeavor (Honig, Citation2004; Sarasvathy, Citation2001) yet many are motivated to persist in new venture creation for a variety of reasons (Hansemark, Citation2003; Koellinger & Minniti, Citation2009; Shane et al., Citation2003). Persistence in entrepreneurship is indicated by continuing to pursue an opportunity to create value through new venture creation regardless of barriers and setbacks encountered and the attractiveness of alternative pursuits (Byrne & Shepherd, Citation2015; Davidsson & Gordon, Citation2012; Holland & Shepherd, Citation2013). It is often identified as a critical factor in determining the success or failure of an entrepreneurial endeavor (Carter et al., Citation1996; Lichtenstein et al., Citation2007). Persisting through adversity and significant change is particularly important in entrepreneurship as it involves an emergent process in which the final outcome may bear little resemblance to the initial idea (Sarasvathy, Citation2001). For these reasons persistence in itself is considered an important part of nascent entrepreneurial activity (Cardon & Kirk, Citation2015: Holland & Shepherd, Citation2013; Shane et al., Citation2003).

Those who persist often have some combination of motivation and external reinforcement (Deci, Citation1972), which may make it possible to continue to pursue their new venture goal even though it is highly uncertain, and often largely undefined (Shane et al., Citation2003). For those who have few personal financial resources, as is the case with many nascent entrepreneurs (Fredric & Zolin, Citation2005), the external support comes in large part from social capital sources; people who are not tied to the venture (at least initially) deciding that they want to support the entrepreneur’s vision of a new venture because they are inspired to do so. In this study we extend our understanding of how persistence might be enhanced or reduced in the early stages of venture creation.

Methods

This study was part of a larger investigation into the experiences of immigrant entrepreneurs which covered two aspects – new venture creation and cross-cultural adaptation. The focus of this paper is primarily on the first aspect – new venture creation – showing how early stage nascent entrepreneurs establish and develop relationships that are relevant for new venture formation and how they access social capital resources from them.

To observe these phenomena as they unfolded “live” (Patton, Citation2015; Yin, Citation2014), we chose a qualitative, longitudinal method, involving real time observations and interactions (Hoang & Antoncic, Citation2003) to avoid post-hoc study bias (Chandler & Lyon, Citation2001) with early stage nascent entrepreneurs over 18 months. Adler and Kwon (Citation2002) argue that social capital is best examined qualitatively, as, unlike financial capital for instance, it is not possible to objectively measure the effort involved in creating social capital. Similarly, development of relational leadership is also best observed as it happens (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006). Observing nascent entrepreneurs from the very earliest stages also allowed us to address Davidsson’s (Citation2006) call for better understanding those who begin the nascent entrepreneurship process but do not succeed in achieving start-up. The 18-month observation period provided sufficient time to examine a wide range and diversity of interactions during what could be expected to represent the full nascent stage for at least some of those who ultimately succeeded in creating their own businesses, and abandonment by at least some others (Lichtenstein et al., Citation2007). Thus, our overall study design addresses many of the methodological issues and opportunities identified in the literature.

Research setting and sample

Our research was set in a small Western European country with immigration being a relatively recent phenomenon. The country culture can be characterized as egalitarian, with low power distance, more individualistic than collectivist approach and low uncertainty avoidance (Hofstede et al., Citation2010). The country scores high in terms of early stage entrepreneurial activity in comparison to other European countries and has a supportive environment for entrepreneurs, with informal social connections prevalent in employment and entrepreneurship (Global Entrepreneurship Monitor, GEM, Citation2020).

We chose to focus on a small number of individual immigrant nascent entrepreneurs for three reasons. First, a sample of immigrants was seen as ideal for a study focused on examining the formation and development of social capital sources and early attempts to access resources over time, as their lack of tenure in the location was anticipated to make these interactions more dynamic than established locals, and thereby help to uncover important changes in social capital sources and resources over time, if they occurred. Second, from a theory-building perspective, studying a small number of individuals over an extended period allowed us to achieve the sort of deep immersion that has been shown to aid theory building (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Yin, Citation2014). It also allowed us to examine the dynamic nature of social capital sources and resources over the journey from inception to start-up or indeed abandonment (Davidsson, Citation2006). Third, our sample selection supports Light and Dana’s (Citation2013) encouragement to study less conventional entrepreneurial groups and settings, as such variations further our knowledge and push existing boundaries of the social capital domain.

Cases were selected based on enrollment in a pre-enterprise training course (enterprise course), intended for and tailored to the needs of immigrant nascent entrepreneurs, and funded by regional government. In addition to covering the essential elements of new venture creation, the enterprise course content also included context-specific particularities of life and business in the host country (for example, one topic was called “What they don’t tell you about doing business in [country name]).”

In line with Yin (Citation2014), participants were purposefully chosen to best access the range and diversity of the phenomena we expected to examine. outlines the key sample characteristics which shows diversity and richness. The study participants were diverse in their economic and sociocultural backgrounds ranging from a developed Western country (France), postcommunist countries (Albania and Hungary), a caste-system country (India), and a developing country (Nigeria). Most of these cultures were much more collectivistic, with a more formal power structure than the host country (Hofstede et al., Citation2010), which made the social capital development more pronounced. Our sample was split evenly between males and females and they had diverse family and home roles. All participants were in their thirties, which aligns with learning that most early entrepreneurial activity happens when people reach their early thirties (GEM, Citation2020). Even though older entrepreneurs can draw from a larger base of social networks (Seibert et al., Citation2001; Zhao et al., Citation2021), entrepreneur’s age is not a significant success factor in new venture creation (GEM, Citation2020). When engaging with the data, the sociocultural and human capital attributes (such as age, education, family status, previous entrepreneurial experiences) were considered as part of data sensemaking (Klyver & Shenkel, Citation2013).

Table 1. Sample description.

We anonymized all aspects of our sample and eliminated all identifiers that may allow deductive identification. This anonymization was done in line with ethical guidelines (Saunders et al., Citation2016) to the extent possible without masking aspects that are important to understanding and interpreting the data and our findings. Research was approved by university ethical committee in line with relevant research integrity codes of conduct (ALL European Academies, ALLLEA, Citation2017).

Data generation

We carried out field research over a period of 18 months, including four months of ethnographic observation, two rounds of interviews, and ongoing informal communication, which spanned the full 18-month data collection period. Data generation was conducted by the first author, also a non-native to the host country, who participated in the enterprise course alongside study participants. This use of the participant-observer form (Hammersley & Atkinson, Citation2006; Saunders et al., Citation2016) provided a common ground for conversations, course tasks and building of trust: allowing the first author to interact freely and regularly with study participants throughout the 18-month data collection period. It also created a sense of shared journey with study participants. For example, the division between “them” (the native locals) and “us” (the participants and the participating first author; all immigrants exploring new venture creation) was often implied during conversations by the participants. The researcher’s background, values, biases, judgments, professional background and familiarity with the topic all shape the interpretation of the research (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008; Creswell & Creswell, Citation2018). The researcher took measures and precautions to minimize subjectivity and research bias stemming from being a research instrument including maintaining researcher’s reflections, looking at negative cases, always questioning one’s assumptions (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2008), member checking, peer debriefing, and ensuring transparency and traceability of data coding process using NVivo software tools. shows the timeline of data generation.

In addition to four months of ethnographic observation, which included ongoing, informal communication inside and outside of the enterprise course sessions, longitudinal data was collected for another 14 months. This included two rounds of qualitative interviews (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2011); regular informal communication and interactions with study participants, via group and individual meetings; informal phone conversations, digital video conversations (for example, Skype), e-mails, and social media interactions. Formal interviews were semi-structured, with predefined themes, while allowing flexibility for the emergence of new insights (Gioia et al., Citation2013), and lasted between 50 and 165 minutes in length. All interviews were recorded and transcribed, and all data collected was pseudonymized (Saunders et al., Citation2016), per our research ethics protocol, which called for participant anonymity in all study communications. outlines data sources and how they were used in the analysis.

Table 2. Data sources.

Data analysis

We began sorting and categorizing our emerging data while still in the field, during the initial period of participant observation, and continued alternating between cycles of inductive and deductive reasoning (Gioia et al., Citation2013). NVivo was used to ensure analytical efficiency, clarity and traceability of the analysis process. depicts the coding framework.

During the first round of coding, data was analyzed through an inductive, “bottom up” approach to arrive at a set of first order codes. Although we were familiar with the social capital literature, we strove to allow the codes to be informant-centric. For instance, during the enterprise program observations, we noticed that some participants were more outgoing and engaged than others. Pamela often sat with her arms crossed and appeared less confident when she spoke. One of the first-round interviews built on these observations when participants were asked about how they perceived themselves as entrepreneurs and what challenges they faced. In the first round of interviews when speaking about challenges, Pamela said: “I am the minority. The minority voice will never get heard.” We used this as an in vivo code for other instances when the participants expressed that they felt powerless in comparison to entrepreneurs locally.

After the initial first round of coding, we revised the codes and streamlined some of them due to conceptual similarity. Next, we engaged in abductive logic (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2011; Gioia et al., Citation2013) and explored data along with relevant extant literature. We looked more closely at the relational social capital concepts (Davidsson & Honig, Citation2003; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998) which partially explained what was going on in our data and aided with distilling of codes into second-order concepts. During this stage we also realized that relational leadership theory (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006) explained some of the codes that were created in the first round of coding. We went back to the data to ensure that codes related to relational leadership were saturated and then distilled them into the “relational self-concept” and “relational leadership behaviors” concepts. When exploring the relationship between second-order concepts (Gioia et al., Citation2013), we examined the interaction between “social capital source types,” “social capital source status conditions” and “social capital resources” to understand with whom, how, and why relationships were attempted, established, nourished or abandoned and what resources were promised, delivered or withdrawn, and why. From this we identified 108 instances of relational interaction, either observed or mentioned by participants in interviews or in informal communications. An example of these relational interactions is found in Monika’s case, where she tried to establish a relationship with a local architect who originated from her own country, building on their common cultural and professional background. Even though the other architect provided some encouragement to Monika, she did not develop the relationship further or attempt to draw potentially useful resources from him.

We then progressed our analysis to formulating the dynamic relationships between our second order concepts by linking relational leadership with relational social capital dynamics. To do this we created a conceptual model based on the 108 relational interactions, linking them with relational leadership concepts to see how they impacted new venture creation persistence, which was captured in a “persistence in new venture creation” aggregate dimension. For instance, when we went back to Monika and her attempt to develop a relationship with her fellow architect, we saw that she displayed weak relational leadership behaviors, failed to pursue a potentially useful social capital source, and in turn did not persist with her venture idea in that field.

To ensure confidence in terms of credibility, validity, dependability, confirmability and transferability, we followed and documented procedures (Denzin & Lincoln, Citation2011; Lincoln & Guba, Citation1985; Silverman, Citation2020). These included triangulation of different research tools (observations, interviews and informal communications), verification of emerging concepts with the participants, evidence of transparency of the analytical process in NVivo, regular peer reviews of emerging concepts, and use of a reflective diary. We ensured cross-coder reliability by double-coding a sample of data followed by discussing and resolving any discrepancies, and also by regular data analysis sessions where we analyzed and conceptualized data together (Silverman, Citation2020). For example, second-order concepts that led to the development of the “Relational Social Capital dynamics” theme were abstracted in collaborative analysis sessions.

Findings

All six nascent entrepreneurs explored more than one venture opportunity during the study period, as outlined in . This was often done in parallel, rather than a serial manner, with each participant pursuing at least two venture ideas over the 18-month study period. Although relatively new to the local environment, 16 of the 17 opportunities identified by our six participants targeted host country or international markets, rather than focusing on co-immigrant markets.

Table 3. Entrepreneurial opportunities exploited by participants.

The level of engagement in developing their new venture ideas varied considerably. Lietus, for instance, undertook very little beyond identifying and initial exploration of an opportunity, attempting to organize a team to work on the idea and saving money to invest in his venture. Others, such as Sebastien undertook a wide array of activities, demonstrating considerable effort and persistence in new venture creation.

Social capital sources/resources dynamics

Social capital sources

We identified five broad types of social capital sources based on levels of relationship closeness, cultural similarity and geographic proximity among our entrepreneurs, each having a different “mix” available to them, including: (1) close family and friends nearby, consisting mostly of immediate family living with the participant; (2) close family and friends abroad, representing those who often have similar cultural background living in the participant’s home country transnationally; (3) co-immigrant acquaintances nearby and abroad, involving those with whom a relationship was not close and who were living nearby or abroad with some being of similar cultural origin; and (4) host country community, consisting of members of the common local culture such as enterprise course trainers, colleagues in work, potential suppliers and clients. Each entrepreneur had a different mix of social capital sources developed at the beginning of the study. Although these social capital sources have been previously discussed in the literature, understanding the subtleties of these relationships enhanced our understanding of social capital dynamics in this particular context.

Social capital resources

Examining social capital resources separately and in relation to their sources, we identified that resources sought and acquired by our nascent entrepreneurs included a range of both intangible and tangible resource types. In fact, we found a considerable number of tangible resources being accessed via relationships, contrary to expectations from the main social capital literature, which focuses on intangible resources (for example, Lin, Citation1999; Nahapiet & Ghoshal, Citation1998), although financial resources are not uncommon (Hallen & Eisenhard, Citation2012).

Examples of tangible resources included Pamela planning to access favorable contracts for her specialty bag business via personal connections in India: “I have a few friends [in India], so initially I will be working through them and after that I’ll try and expand my network … They have their own factories.” Sebastien was able to access many services by partnering with others. In his Nintendo accessories online business, he partnered with Fabio, a work friend who “works in an area that is complementary. He works … at the fraud [detection] area. So, he knows how to avoid having problems,” which online businesses commonly face.

Intangible social capital resources, such as moral support, encouragement, and advice were also often sought and acquired by our nascent entrepreneurs. Examples include Monika receiving free advice on her business plan from her enterprise course trainer after the course was finished; Lisa receiving offers of free childcare support from friends in order to allow her to spend time developing her new venture; and Obusi getting free advice on the potential of his health-care recruitment venture from a friend who is a health-care professional: “a friend of mine has been getting serious calls. Even when he doesn’t want to work they call him. That means that there is a shortage of staff, you know. That’s what we said.”

Dynamic interactions of social capital sources and resources

Over the course of 18 months, we were able to observe how social capital resources were developed through relationships. summarizes these findings with illustrative examples for each variation in social capital source and resource.

Table 4. Typology of social capital source and resource dynamics.

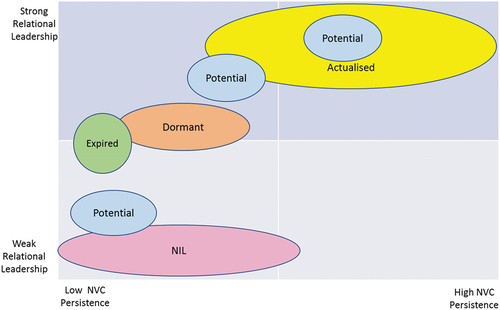

Overall, we observed 14 types of variations or dynamics in social capital sources and resources. These 14 dynamic types were aligned with the five categories of social capital sources status condition, such that one type aligned with the “Nil Source” category, where no social capital source existed, yet there appeared to be need for a social capital source; four types aligned with the “Potential Source” category, where a social capital source had been developed but had not yet provided a resource; six types aligned with the “Actualized Source” category, where a social capital source was providing a resource; two types aligned with the “Dormant Source” category, where a past social capital source no longer provided a resource, but may yet provide new resources; and one type aligned with the “Expired Source” category, where a past social capital source no longer provided a resource, and was not considered a potential provider of resources in the future.

The 14 relational social capital dynamics we identified represent the extent of variation we found in our data. We looked at separate instances over the observational period as experienced by each individual, rather than over a period of time, and in connection with separate venture ideas. There may be other dynamics beyond those experienced by our nascent entrepreneurship cases. Hence, this is not intended to represent the complete set of dynamic types that might be obtained, but rather a depiction of the range and types of dynamics that nascent entrepreneurs who have few established social relationships when commencing their entrepreneurial journey may encounter.

Relational leadership

Relational leadership self-concept

Our observations and data analysis revealed that the participants’ self-concept perceptions were constructed from interactions with others which then impacted future interactions (Kim, Citation2017). These perceptions of self, embedded in wider experiences of cross-cultural adaptation, were mostly consistent over time and either enhanced the process of initiating and enacting relationships with others or acted as a barrier.

Even though Obusi experienced some difficult times as a newcomer of a different race, he mostly appeared to be proactive, resilient and positive. He encountered difficulties when he looked for work experience as part of his business course: “I’m reading through so many papers or if I see any van … I write down the number, I go to the website, email them, phone them … I just want to get trained … take me as an apprentice, don’t pay me … don’t bother how I get there. I’ll make myself available, just to acquire the knowledge … But they just don’t want to give me a chance?.” He persisted, eventually found a placement, and completed his course, which he took to help meet his self-employment goals: “ … you may decide that you are not going to be poor your parent’s way. And how do you do that, through your hard work [and] determination to succeed.” As our observational notes show, Sebastien had a consistent positive attitude when interacting with others during the enterprise course and when he recounted his interactions with others in his interviews. Even when his proposed business relationship with an artist did not work out, his motivation to interact with others remained positive: “I have great ideas … it’s a new challenge. I like it. I am enjoying this … because I was getting bored at work.” Lietus, who previously experienced business failure and bankruptcy, was determined to start again: “I want my own business here. And when I taste it [being an entrepreneur], I can’t forget, so it’s very difficult to me to work for somebody else.”

Some of the other entrepreneurs had mostly negative relational self-concept perceptions, influenced by cultural, gender and family factors, remaining largely negative over the study period. Pamela perceived herself as disadvantaged due to her family commitments; having two small children and a husband with a full-time occupation: “ … organizing time would be very difficult [to pursue venture creation further]. My husband works full-time. He’s never home before eight in the evening … I don’t have childcare and I can’t afford childcare until I make some money. I couldn’t put 1,000 euros every month to put my child in a crèche while I go looking for business.” Both Pamela and Lisa’s choice of entrepreneurial path was connected to fitting self-employment around family responsibilities and having enough employees in business to accommodate for future family responsibilities was also consideration for Monika (who did not have children at the time). As Lisa simply put it: “I need to be there for them [children]. I want actually!.” These gender and family role related self-concept perceptions and motivations are commonly recognized in literature in relation to female entrepreneurs (De Pater et al., Citation2009).

Pamela consistently felt that her status as a newcomer was a disadvantage to her: “Who am I? I am the minority, you know. The minority voice will never get heard. That’s the way the world goes.” Similarly, Monika was aware of her own negative relational self-concept perceptions stemming from her cross-cultural adaptation, negative employment experiences, and temporary mental health difficulties. It prevented her from initiating, establishing and nurturing relationships useful for business ventures. Contemplating this issue, she noted: “I am not the only foreigner here. So … there are foreigners who make business with the locals. I should be more confident I think I am not at home blah, blah, blah. These are excuses.” When her personal situation worsened as a result of perceived constructive dismissal with the prospects of unemployment, in an informal conversation she mentioned that she felt “disabled” by her foreign status. Similarly, Lisa openly declared that “I’m not very confident. It’s my personality” and she initiated few relationships over the study period. It seems that despite all of the participants in our sample experiencing challenges in cross-cultural adaptation and interactions with others, the female participants encountered additional barriers which led to more consistently negative self-concept perceptions. These gender differences in relation to the participants’ display of self-concept perceptions is interesting. One explanation is that the female entrepreneurs were usually more vocal about their perceived difficulties and recounting stories of interactions leading to more negative relational self-concept than the male entrepreneurs.

Relational leadership behaviors

Our data analysis uncovered new insights into what specifically our nascent entrepreneurs were doing when engaging with various social capital sources. We found that the nascent entrepreneurs were employing, or attempting to employ, a range of relational leadership behaviors to establish and develop relationships that might provide resources. We compared our individual participants’ relational leadership behaviors across their own, multiple venture ideas and time and found that they were broadly consistent and linked to their individual relational self-concept perceptions.

In addition to positive relational self-concept perceptions, Sebastien consistently demonstrated strong relational leadership behaviors and persisted with efforts to create five new ventures over the 18-month study period, with three being successfully launched in that time. He was able to identify people’s strengths and interests and influence them to partner with him on various ventures for mutual benefit. He was also effective at accessing other skills and services through these social capital sources, such as his former classmate Stéphane from a postgraduate program that they completed together almost four years earlier: “I contacted him and told him I have an idea […] he told me that he knew somebody to do some work to build the website. So, I thought okay, that’s fine … It’s 50/50: 50 for me and 50 for them … It’s not equal because I brought the idea.” Sebastien also started another business partnership to work on an entertainment website with a colleague from work and her partner: “it’s a couple … she is very good at websites and all the graphics … she works with me.” Sebastien further demonstrated his strong relational leadership behavior that helped him to attract a range of resources from a variety of different sources, as this example for his online gaming accessories website shows: “We are three people working on it. There is one dealing with the website, programmer. He has done all the website. The other one is dealing with the promotion, AdWords … I am dealing with the contents … and my parents, they are shipping.”

We also observed similar patterns in weak relational leadership behaviors among some participants. Monika rarely demonstrated relational leadership behaviors, often exhibiting weak relational leadership or no leadership at all throughout the 18-month study period. As described earlier, her self-concept perceptions were also consistently low. For example, her enterprise course trainer, Kevin, proposed to pay a certification for her in exchange for her providing an energy-rating survey. This would give Monika additional qualifications in her field, and a future consultancy opportunity, while Kevin obtained a legally required survey at low cost. “I have been talking with Kevin … he phoned me, you know about that course … he promised me to get back, but he hasn’t gotten back. But he sent me a letter in January and we spoke about these things in December. So, a couple of months … he promised me to get back to me.” Monika did not follow up with Kevin to enact this exchange. Hence the opportunity was lost.

Monika did, however, successfully achieve a start-up with a jewelry business that included jewelry-making, selling of jewelry patterns and teaching others how to make jewelry. As a hobby, Monika had been making her own jewelry and selling it informally at weekend markets for some time. Given her informal background in jewelry-making, she required few social capital resources to formalize and expand this into a business. Also, while this was a more formal business, Monika viewed it as transitionary as she shared the news in an e-mail: “tomorrow I will have a student in beadworking:-) So it is evolving. I may give up architecture … at least for a while until the economy gets better.”

Pamela also had difficulty initiating relationships that would provide useful social capital resources. When asked about drawing on relationships that might prove useful for the development of her business idea, she replied: “there’s zero. I don’t have a network … The people I meet would be people I don’t expect to get anything out of apart from friendship.” She explained this reluctance to engage with those she knew already: “as a friend I have nothing to gain from the person but I have no expectation from the person. But if I am doing business with them I’d expect that he would keep his word. If it says Tuesday morning at five it will be ready, I want it ready. Because that’s the way I operate. So suddenly you find that there are a lot of differences in the way you operate and the friendship is gone. I don’t want that to happen.” We saw that Pamela’s relational self-concept perceptions were negative due to her perceived newcomer status, family obligations, cultural differences and some negative encounters with the locals. In combination with weak relational leadership behaviors demonstrated by anticipated lack of reciprocity and trust, she was unable to benefit from actualized social capital dynamics, obtaining resources that might have helped progress her venture ideas.

Persistence

As part of our iterative analytical approach, we examined our data in the context of the 14 relational social capital dynamics that our nascent entrepreneurs experienced over 18 months (see ). We did this by looking at each social capital dynamic for each individual and venture idea separately, noting details on how the entrepreneurs engaged, in terms of their relational leadership (relational self-concept perceptions and relational leadership behaviors) and how a particular interaction affected their views about entrepreneurship, and their interest or persistence to continue to pursue a new venture. maps out these interactions.

Figure 3. Interactions between relational social capital dynamics, relational leadership and persistence with new venture creation.

We found that weak relational leadership behaviors were followed by low persistence, which resulted in nil interactions. Lietus recognized that local connections would be beneficial for starting of his family restaurant business, but he did not initiate those relationships. Low relational self-concept perceptions (related to cross-cultural, family and other experiences) prevented some of our nascent entrepreneurs, such as Lisa, from reaching out to potentially useful social capital sources. This was followed by decreasing persistence in her new venture creation. Lisa explained her reluctance to make contact in the context of trust and confidence: “you would trust more somebody from your country than from outside it’s more difficult to trust on them.” Monika also struggled with low relational self-concept, avoiding making contact or following up with people who were potentially useful sources. For instance, she avoided contacting the head of an architect organization recommended to her by her mentor, so she could engage with the members and promote her breeze block business – instead of reaching out to them after not hearing back for some time, she took no action. The lack of progress in establishing useful relationships led to gradual disengagement and lack of progress in developing the nascent entrepreneurial idea.

Potential social capital sources were relationships developed or maintained without accessing resources at that time (see ). When a potential social capital source provided a resource, they were then recorded as an actualized source. Potential sources were observed in smaller clusters with varying relational leadership and persistence levels attributed to them. Entrepreneurs who demonstrated weak relational leadership behaviors and low persistence in these instances included potential sources that were already known to the entrepreneurs but from whom resources were not yet accessed. For instance, Lietus understood that his wife would provide book-keeping for their new family restaurant venture, but as he did not pursue the idea further, she remained a potential source.

We also observed cases where the entrepreneurs engaged with potential sources (relationships developed without accessing resources at that time) and exhibited strong relational leadership behaviors. This was followed by positive feedback for our nascent entrepreneurs, such as having a desirable contact agree to meet and discuss a new venture idea. This in turn was followed by a strengthening of their resolve to pursue the venture. Obusi initiated and put effort into maintaining relationships with other participants from the enterprise course as he believed that they could be useful not only for moral support but to provide other resources when the time was right. This moral support propelled him on as he felt that his health-care recruitment venture was worth pursuing further.

Finally, as seen in the upper right quadrant of , there were also cases of participants who demonstrated strong relational leadership and anticipated with confidence that their potential sources would convert to actualized oneswhen the timing was right. Sebastien actively nurtured relationships with work colleagues and transnationally located acquaintances, as he knew from past experiences that they could provide useful resources: “I prefer to work with someone that would bring something, like skills or something complementary, […] it’s networking you know. You can use the skills of others because you’re not good at everything.”

Actualized sources represented those interactions that provided resources and, therefore, increased persistence. We observed consistent patterns where strong relational leadership behaviors were followed by persistence and eventual business launch. For instance, Sebastien’s consistently strong relational leadership behaviors garnered him considerable input and agreement to partner from a number of acquaintances, new and old. When discussing how he found his latest idea for an online business, Sebastien attributed it to his business partner, Jeremy: “a friend from Belgium, who is very, very good at computing and all these kind[s] of things. So, I partner with him. The idea comes from him. He is the brother of a friend I knew in Belgium … I saw him sometimes but not all the time. And because I went to Belgium two times, two weeks ago and we talked about this and he told me, ‘I’m looking for this product, [a] Wi-Fi booster. I cannot find it. Do you know a provider in China?’ So, I asked my provider and she said ‘Yeah, I have this.’ He knows how to build a shop – online shopping – and from my part I know very well the provider, so we can do this.”

We observed some instances of dormant sources where former sources no longer provided resources but could be revived again when needed. Obusi received mentorship, emotional support and referrals from enterprise course trainers. When he had to put his venture idea of a recruitment agency on hold, he intended to come back to the mentors for more advice: “those guys … are good and they are friendly … but I just don’t want to go there when I have nothing to talk about … They believe in action. They believe in you having something to do and know what you are talking about.” Dormant relationships were still maintained by the entrepreneurs showing some relational leadership behaviors, either because these were with close family members who would provide resources when required again or because the relationships were strongly established and nurtured based on past interactions.

Expired relational dynamics represented those that could no longer provide resources in the future, as the relationship itself had ended. Such relationships were deemed no longer viable for a variety of reasons. Obusi originally planned to partner with a friend in the medical profession from his home country for his health-care recruitment agency. However, they lost touch, which led to Obusi exploring the idea somewhat further on his own with moral support from his classmates, but eventually abandoning it.

What happened to our six nascent entrepreneurs at the end of the study? After 18-months of data generation, two participants had achieved start-up, here defined as achieving first sale (Reynolds & Miller, Citation1992), one was still pursuing start-up, and three had either abandoned or put on hold their nascent entrepreneurial efforts. Lisa was still pursuing the creation of a book-keeping venture, having put on hold two other opportunities that she explored during the 18-month study period. Obusi, Pamela, and Lietus each explored several opportunities, but at the end of the study period had either abandoned or put their venture creation activities on hold. Sebastien started three online ventures selling different technology-related products to international markets, each with a different transnational partner. Monika created a jewelry business, having put on hold her breeze block professional venture.

Proposition development

Our findings are summarized in . We illuminate how relationships with social capital sources were initiated and developed, and how entrepreneurs engaged with them through social capital dynamics to draw needed resources for new venture creation. We also uncovered the role of relational leadership in these interactions, wherein those who demonstrated relational leadership behaviors were often successful in accessing needed resources via relationships. These experiences then reinforced the relational leadership self-concept perceptions, encouraging more relational interactions, and hence further persistence in new venture creation.

Relational social capital dynamics typology

Extant research shows that social capital sources and resources vary heterogeneously, and yet little is understood about this variance. Hence, developing a greater understanding of these two dimensions of social capital and their independent and interrelated variance was warranted. Our longitudinal in-depth case-study method provided sufficient data and insight to induce a typology of relational social capital dynamics, explicating the dynamics of social capital sources and resources as individual, interactive dimensions (see ). Hite’s (Citation2005, Citation2003) multidimensional representation of relationally embedded ties in nascent entrepreneurship identified seven types of embeddedness across three main social relationships: personal, dyadic and social capital, with the latter further split into network and dyadic levels. Our work focuses on the dyadic level of social capital – where the individual nascent entrepreneur interacts, or not, with other actors in order to obtain resources for use in the creation of a new venture. We show that there is further relevant dimensionality here, with the 14 different dynamic types we have identified. This stems in part from looking not just at the relationships and resources that our participants obtain, but also at what is missing; what resources the nascent entrepreneur needs but is unable to obtain through social capital sources at a particular point in time, and over time.

Analysis of the typology in the context of our data suggests that while the interaction with social capital sources is dynamic and temporal, it is also highly contextual. New resources were accessed from sources that remained constant over time, and existing resources were no longer offered by sources that remained over time; those who were social capital sources at one stage, and were still social relations at a later stage, but no longer provided social capital resources. Similarly, new sources were developed but provided resources that were previously accessed from other sources, and new sources were developed that provided new resources. Building on this learning, we begin to hypothesize how nascent entrepreneurs engage with social capital, and how source and resource changes impact the venture creation process. We do this by combining our specific learning in this study with that from extant research, in order to develop propositions that we suggest can form the foundation for a theory of social capital development in the nascent entrepreneurial process.

Social capital and relational leadership

Unlike organizational settings (for example, Simsek & Heavey, Citation2011), developing social capital among our nascent entrepreneurs involved obtaining resources from another person who was not associated with the nascent entrepreneur previously, not obligated to help, or not financially incentivized to provide such a resource. Previous entrepreneurship research has noted the importance of leadership (for example, Gupta et al., Citation2004; Stam & Elfring, Citation2008), but to our knowledge, has not identified the importance of relational leadership in the very early nascent entrepreneurship stages, when there is essentially no one to lead formally.

One of the major challenges for nascent entrepreneurs is often garnering resources needed to create the venture, given that they tend to be idea rich and resource poor (Fredric & Zolin, Citation2005; McCarthy & Gordon, Citation2011). Our nascent entrepreneurs were mostly well-educated individuals who, at the beginning of our study period, had considerable work experience and thus an understanding of how to interact with others in the world of work. Yet, as with many entrepreneurs, they displayed considerable uncertainty for their new venture ideas, looking for signs of support in order to affirm that they should be investing time and energy, and possibly their own funds, in their ideas.

We found that our nascent entrepreneurs were displaying varying levels of relational leadership behaviors when initiating interaction with social capital sources for new venture creation. We observed instances in which entrepreneurs demonstrated relational leadership behaviors, undertaking the main activities outlined by Uhl-Bien (Citation2006): establishing business relations, influencing others to adopt shared goals, asking for specific resources to help achieve goals, and identifying and supporting the needs and goals of others. We also observed instances where our entrepreneurs were struggling to initiate, establish or maintain relationships with potentially useful social capital sources; were unable to influence relations to adopt shared goals; unwilling to draw much needed resources from their relations; or failed to consider or support the needs and goals of relations.

Studying a small number of nascent entrepreneurs in-depth allowed us to explain some of the reasons for differences in relational leadership. Relational self-concept of individuals played a role in propensity or willingness to lead, as well as leadership behaviors displayed. Those whose relational self-concept perceptions included feeling less important than other business stakeholders, less confident in approaching others, or feeling less motivated to engage, had negative social capital development experiences and hence remained “non-leaders” consistently over time. Those whose relational self-concept perceptions included confidence when engaging with others and confidence in their own abilities, demonstrated higher relational leadership skills and often experienced positive social capital interactions.

Persistence

Entrepreneurship is a challenging, uncertain, and risky endeavor (Honig, Citation2004; Sarasvathy, Citation2001) yet many are motivated to pursue and persist in new venture creation for a variety of reasons (Hansemark, Citation2003; Koellinger & Minniti, Citation2009; Shane et al., Citation2003). We observed patterns that suggest our nascent entrepreneurs’ early interaction with social capital influenced their persistence in pursuing a particular new venture creation. In line with motivation theory (Deci, Citation1972) and theory of legitimacy (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994; Fisher et al., Citation2016), these social capital interactions may be acting as a positive extrinsic reinforcement for our nascent entrepreneurs varied intrinsic motivations.

Examining relational social capital dynamics and relational leadership, we also noted patterns in the data linking use of relational leadership behaviors not just with receipt of social capital resources, which might be expected, but also with increased persistence with new venture projects and resilience in pursuing entrepreneurship as a career path over time. The persistence pattern appeared to be separate to, or over and above resource receipt, suggesting that simply enacting good leadership practices was by itself increasing our nascent entrepreneurs’ persistence. Merely making contact – the first step in the relational leadership process – may appear a weak indicator of leadership behavior. Yet we observed a number of cases where our nascent entrepreneurs experienced increased persistence simply from taking this first relational leadership step. In other cases, abandonment occurred from avoidance or reluctance to make initial contact with potential social capital sources.

Thus, our findings suggest that strong relational leadership is valuable to entrepreneurs well before they have an organization or employees to lead, and that relational leadership practices are associated with acquisition of what might be seen as traditional social capital resources, such as knowledge and information, influence among potential stakeholders, as well as a social capital resource which may have been overlooked in past social capital research: persistence. Entrepreneurship research has highlighted the importance of persistence (Cardon & Kirk, Citation2015; Carter et al., Citation1996; Davidsson & Gordon, Citation2012; Lichtenstein et al., Citation2007), but to our knowledge has not found links between enacting relational leadership and persistence. We were particularly surprised by the fact that, even when there are no social capital resources received or on the horizon, enacting relational leadership was linked to persistence among our nascent entrepreneurs. This suggests that enacting relational leadership might be signaling to the nascent entrepreneur that they have the basic skills necessary to proceed to develop a new venture, or at least to continue to pursue the idea until some other potential barrier or adversity becomes salient, such as those shown in Holland and Shepherd (Citation2013).

Reviewing the entrepreneurship literature, we find no prior evidence or theoretical work that would support, contextualize or refute these relational leadership findings. We were also unable to find other literature that identifies or examines the importance of relational leadership to nascent entrepreneurs specifically; those who have few to no other people to lead within their nascent ventures. The entrepreneurship literature that does address leadership development uses contexts of established firms, for the most part (for example, Dover & Dierk, Citation2010; Leitch et al., Citation2013; Schenkel et al., Citation2009; Yrle et al., Citation2002), which is not directly relevant to our findings. Thus, we proceed to develop propositions based on our learning from this study.

As shown in , we observed that demonstration of relational leadership behaviors had a positive effect on our nascent entrepreneurs’ social capital interactions as well as helping them to obtain needed resources. We also found patterns suggesting those who were engaging in strong relational leadership behaviors were also persisting in their new venture creation projects, and those who were reluctant to engage, or were engaging in social capital development without using relational leadership were abandoning their ventures. Given that, based on our observations and reasoning from the literature, positive interactions with social capital sources occurred when our nascent entrepreneurs’ actions followed relational leadership behaviors, and that relational leadership has been shown in the literature to have association with creation of social capital inside organizations, we propose:

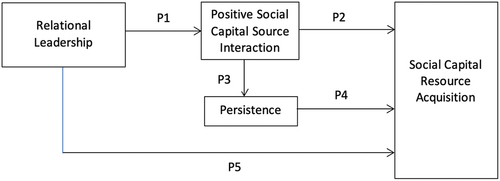

P1. Nascent entrepreneurs whose social capital interactions demonstrate relational leadership will be more likely to experience positive initial interactions with social capital sources.

P2. Nascent entrepreneurs who experience positive initial interactions with social capital sources will be more likely to acquire social capital resources.

P3. Nascent entrepreneurs who experience positive initial interactions with social capital sources will be more likely to persist in their new venture creation projects.

P4. Nascent entrepreneurs who persist in their new venture creation projects will be more likely to acquire needed social capital resources.

P5. Nascent entrepreneurs who exhibit relational leadership will be more likely to acquire needed social capital resources.

Taken together, the five propositions presented here represent the outline of a theory of social capital development in the nascent entrepreneurial process; we propose that relational leadership practices lead to positive initial social capital interactions, which increases social capital resource acquisition and persistence in entrepreneurial efforts. Persistence in entrepreneurial efforts, in turn leads to acquisition of social capital resources. Engaging in social capital interactions using relational leadership behaviors also directly leads to acquisition of social capital resources. provides a depiction of the relationships proposed.

Discussion

Our insights into the lived experience of entrepreneurs at the earliest stages of new venture development contribute to theory development and practice in entrepreneurship. The purpose of this article was to explore and address gaps in the literature at the intersection of social capital development, nascent entrepreneurship success in achieving start-up, and entrepreneurial leadership by providing insights into how nascent entrepreneurs develop and interact with social capital sources to access resources needed for new venture creation.

Our study makes three main contributions. First, we contribute to the social capital literature by revealing how those with poor initial ties, and thus few if any social capital sources, actually go about developing them, thus addressing a gap in our understanding of the nascent entrepreneurship process of resource acquisition and resource deployment. Our work addresses Gedajlovic et al.’s (Citation2013) call for longitudinal studies that examine social capital development over time in entrepreneurship settings, because the social capital literature generally and in entrepreneurship specifically was lacking understanding of the dynamics of social capital development. In addition to providing insight into the process of social capital development in early-stage entrepreneurial activity the typology of relational social capital dynamics that we induced from our data, provides entrepreneurship social capital scholars with a tool to assist future study of other micro-level questions about social capital development in entrepreneurial ventures. It was through construction and examination of this typology that we first glimpsed the role of relational leadership in the social capital development process for our initially follower-less nascent entrepreneurs. We expect similar valuable insights can be gleaned by applying the typology to other nascent entrepreneurial contexts, and possibly further afield.

Second, we contribute to the entrepreneurial leadership literature by showing that relational leadership behavior is important to nascent entrepreneurs even at the earliest stages of nascent venture creation activity, because it can motivate persistence and thus increase potential for achieving start-up. In the context of Tsai and Ghoshal (Citation1998) we show that the value nascent entrepreneurs place on social capital sources, and their response to barriers encountered in attempting to establish social capital sources and obtain social capital resources, impacts their belief in the viability of their new venture project, the venture creation process itself, and, ultimately, the likelihood of persisting with new venture development. The propositions we develop will allow for further study, development and extension of our initial theory of social capital development in entrepreneurship. Specifically, we call for deductive research to test our propositions for their validity and reliability in predicting nascent entrepreneurial behavior and outcomes, and thus establish the boundary conditions under which they areobtained. Our propositions and theoretical outline can also be developed further through future qualitative studies that examine similar phenomena among other groups of entrepreneurs.

Third, we contribute to entrepreneurship practice by showing how those who are attempting to create a new venture of their own can benefit from developing and employing relational leadership even when they appear to have no one to lead. Our work suggests that using relational leadership practices – which can be learned – when engaging with the many varied stakeholders that nascent entrepreneurs meet on their entrepreneurial journey will help them to garner the social capital resources they require and help motivate them to persist in building their ventures in the face of adversity. Our learning suggests that entrepreneurship education and training should include building awareness and understanding of the importance of social capital development through relational leadership behaviors. Further, we suggest that experiential education activities should be included in the curriculum whereby students engage in actual social capital source development and attempt to garner resources for their nascent venture ideas from these sources. We expect that this experiential activity will be especially helpful in generating the necessary relational leadership behaviors and overcoming the reluctance to engage in social capital building that we observed some of our study participants experience. Our experience as university instructors teaching entrepreneurship reinforces the value of experiential activities in helping students to overcome reluctance to engage in social capital building generally, although we have not yet incorporated relational leadership-specific teaching and experiential activities.

Limitations and future direction

Our longitudinal, in-depth observation of six nascent entrepreneurs entails limitations on the use of our findings. Although a sample of this type yields important benefits to studying social capital dynamics, such as providing cases that will likely involve less well-established social capital sources in the host country, and thus greater variance in social capital development, the unique nature of this group limits the generalizability of our findings. We also note that our immigrant entrepreneurship sample had some social relations in their host country and also engaged with social relations from their home country and/or other countries. Although this was expected, we acknowledge that it reduced the opportunity to observe purely new tie formation contexts. We hope that this work will motivate further longitudinal observation studies among a wide range of groups and in various contexts to bring greater generalizability to our findings. This will help to achieve our overall goal, shared by many entrepreneurship researchers, to develop a robust theory of social capital development in entrepreneurship.

We acknowledge that there may be alternative explanations for some of our findings which presents opportunities to build on this research. Previous research showed the role of individual and socially constructed variables on building networks and accessing social capital resources during the new venture creation process, including social skills and competencies (Lans et al., Citation2015), empathy, founder’s identity, and imprinting (Fauchart & Gruber, Citation2011; Micelotta et al., Citation2018). The impact of the composition and structure of entrepreneur’s first partnerships (Milanov & Shepherd, Citation2013) and the effect of absorptive capacity in enabling venture performance from the relationships into valuable learning outcomes (Hughes et al., Citation2014) were also found to positively impact on venture success. Studying practices that lead to the development of relational leadership with a focus on relational leadership skills (Uhl-Bien, Citation2006) would provide further insights into when and why individuals succeed or fail. Although we did not find evidence of these concepts in our data, future research that focuses attention on internal entrepreneurial characteristics and the relational and cognitive dimension of social capital could provide valuable insight on the role on this broader area of socially constructed identity and self-perception in developing social capital sources and resources.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Adler, P. S., & Kwon, S. W. (2002). Social capital: Prospects for a new concept. Academy of Management Review, 27(1), 17–40. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134367

- Aldrich, H. E., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). ‘Fools Rush in – The institutional context of industry creation. Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1994.9412190214

- ALL European Academies. (2017). The European code of conduct for research integrity.

- Amabile, T. M., Schatzel, E. A., Moneta, G. B., & Kramer, S. J. (2004). Leader behaviors and work environment for creativity: Perceived leader support. The Leadership Quarterly, 15(1), 5–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2003.12.003

- Anderson, M. H. (2008). Social networks and the cognitive motivation to realize network opportunities: A study of managers’ information gathering behaviours. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 29(1), 51–78. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.459

- Ardichvili, A., Cardozo, R., & Ray, S. (2003). A theory of entrepreneurial opportunity identification and development. Journal of Business Venturing, 18(1), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(01)00068-4

- Atwater, L., & Carmeli, A. (2009). Leader-member exchange, feelings of energy and involvement in creative work. Leadership Quarterly, 20(3), 264–275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2007.07.009

- Baker, W. (1990). Market networks and corporate behavior. American Journal of Sociology, 96(3), 589–625. https://doi.org/10.1086/229573

- Banks, G. C., Batchelor, J. H., Seers, A., O’Boyle, E. H., Pollack, J. M., & Gower, K. (2014). What does team–member exchange bring to the party? A meta‐analytic review of team and leader social exchange. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 35(2), 273–295. https://doi.org/10.1002/job.1885

- Bird, M., & Wennberg, K. (2016). Why family matters: The impact of family resources on immigrant entrepreneurs’ exit from entrepreneurship. Journal of Business Venturing, 31(6), 687–704. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2016.09.002

- Bizri, R. M. (2017). Refugee-entrepreneurship: A social capital perspective. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 29(9–10), 847–868. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1364787

- Byrne, O., & Shepherd, D. (2015). Different strokes for different folks: Entrepreneurial narratives of emotion, cognition, and making sense of business failure. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(2), 375–405. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12046

- Cardon, M. S., & Kirk, C. P. (2015). Entrepreneurial passion as mediator of the self‐efficacy to persistence relationship. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 39(5), 1027–1050. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12089

- Carmeli, A., Ben-Hador, B., Waldman, D. A., & Rupp, D. E. (2009). How leaders cultivate social capital and nurture employee vigor: Implications for job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(6), 1553–1561. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016429

- Carter, N., Gartner, W., & Reynolds, P. (1996). Exploring start-up event sequences. Journal of Business Venturing, 11(3), 151–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-9026(95)00129-8