ABSTRACT

Just as for most of the world, the COVID-19 pandemic had detrimental impacts on the well-being, mental health, and productivity of entrepreneurs. To delineate these effects, the current study draws from social role theory to predict that women entrepreneurs exhibit a diminished sense of well-being compared with their male counterparts, due to the greater work–family conflict women experienced during the pandemic. The authors leverage gender egalitarianism theory to argue further that in gender-egalitarian contexts, in which women are socioeconomically, institutionally, and culturally more equal to men, this gender gap in psychological well-being, caused by work– family conflict, may be mitigated. A sample of 5,754 entrepreneurs from 27 European countries who completed Eurofound’s Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Survey confirms these predictions, with notable implications for research and practice.

Not only is COVID-19 the deadliest infectious disease in recent history, but it also has been among the most devastating in terms of its economic impacts (Sharma et al., Citation2022). During the pandemic, businesses closed, economic activity was severely curtailed, trade was disrupted, and jobs were destroyed (an estimated 114 million job losses in 2020 worldwide; International Labour Organization, Citation2020). Entrepreneurs were particularly affected, faced with threats of bankruptcies, massive declines in income and sales, liquidity problems, existential risks, and vast uncertainty (Block et al., Citation2022; Fairlie & Fossen, Citation2021; Manolova et al., Citation2020).

Moreover, anecdotal evidence suggests that entrepreneurs particularly struggled with work–family conflict, as arises due to incompatible professional and personal spheres.Footnote1 During the COVID-19 pandemic, women entrepreneurs in particular faced significant work and family challenges. Their businesses were hit especially hard in terms of trade volume, income losses, and closures, compared with male-owned businesses (Graeber et al., Citation2021; Stephan et al., Citation2020). They also were more likely to face greater demands in the private sphere, such as for homeschooling or extended care for children, the elderly, friends, and neighbors (Stephan et al., Citation2020). These likely contributors to experiences of work–family conflict in turn may have had negative consequences for perceived well-being. In support of such predictions, data from the British Household Longitudinal Study, which assessed people’s feelings during the pandemic, such as how they “[had] been feeling over the last few weeks,” showed that COVID-19 created significant work–family imbalances that threatened the well-being of entrepreneurs, and particularly women (Stephan et al., Citation2020; Yue & Cowling, Citation2021). Women entrepreneurs reported a stronger decline in their level of well-being than men entrepreneurs during the first lockdown (early 2020; see in the Appendix). They also were more likely to report above-average depression, concentration problems, lack of sleep, constant tension, and lack of self-confidence; they indicated an inability to enjoy their daily activities; and they reported being unhappier than usual. The gender differences in such reported feelings decreased when lockdown restrictions were eased, but they increased again during the second lockdown. This initial evidence implies that women entrepreneurs may have been more adversely affected by the COVID-19 pandemic than men entrepreneurs.

However, no systematic research into the impact of the pandemic on women and men entrepreneurs’ work–family balance or well-being has established the precise implications of the crisis for entrepreneurial well-being beyond a general sense that it was detrimental (Yue & Cowling, Citation2021). To address this research gap, we explore the tensions that women and men entrepreneurs experienced at the work–family interface and the implications for their psychological well-being, with a particular focus on potential gender-specific differences during the pandemic.

Social role theory literature (Eagly & Wood, Citation1999, Citation2012) highlights the importance of gender norms, stereotypes, and role expectations for explaining distinct behaviors. In line with this theory, we predict that women entrepreneurs faced more intense work–family conflict during the pandemic, which blurred the boundaries between work and family, due to their increased household and family responsibilities.Footnote2 Gender norms in many countries attribute domestic tasks such as child and elderly care and housework to women (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015; United Nations Development Programme [UNDP], Citation2020) and the pandemic increased work-at-home behaviors (Espitia et al., Citation2022; Nyberg et al., Citation2021), so we anticipate that women took on even more household tasks during the pandemic. In addition, we hypothesize that such work–family conflict led to gender-based differences in psychological well-being, with women entrepreneurs exhibiting less well-being than their male counterparts. Finally, we combine social role theory and gender egalitarianism literature to predict that in more gender-egalitarian contexts, in which women are socioeconomically, institutionally, and culturally more equal to men, gender differences in work–family conflict and psychological well-being should be lower. A country’s level of gender egalitarianism reflects the extent to which gender roles are equal for men and women, and women have more socioeconomic resources at their disposal, benefit from institutionalized rights, and experience cultural support (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015; Emrich et al., Citation2004; House et al., Citation2004). We test these hypotheses among a sample of 5,754 entrepreneurs from 27 European countries who participated in Eurofound’s Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Survey, as we detail in the following sections.

From a theoretical perspective, the results reveal significant gender differences in perceived work–family conflict, particularly for women entrepreneurs in times of crisis, with implications for their psychological well-being. As a complement to previous research that highlights the positive effects of entrepreneurship on women’s work–life balance (Joona, Citation2017; Lim, Citation2019; Noseleit, Citation2014), we acknowledge that crises can reinforce traditional gender norms and exacerbate women’s psychological distress, especially in less-gender-equal societies. The data analysis further reveals that both women and men faced significant work–family imbalances, so in certain conditions, gender equality may entail greater work–family conflict among men entrepreneurs too. Such outcomes cannot negate the importance of gender equality, but they suggest the need for further research into the conflicts men might confront in more-gender-egalitarian contexts. From a practical perspective, our findings underscore the need for flexible work arrangements, societal support, and government benefits, including childcare subsidies, especially when remote work is the norm. At the policy level, supportive infrastructures could help all entrepreneurs balance their work and family responsibilities, particularly in times of crisis. In addition, gender equality can assist not only women entrepreneurs but all women, especially mothers, who are particularly vulnerable in times of crisis. Improvements in business climate, career opportunities, maternity leave, and antiharassment policies can contribute significantly to women’s overall well-being.

Theoretical background

Gender differences in entrepreneurs’ work–family conflict

Different motivations likely drive men and women to become entrepreneurs (Marlow, Citation2002). Income growth, promising career prospects, and being one’s own boss are the main motivators for men. The decision to start and run a business also might result from a lack of alternative employment opportunities (so-called necessity entrepreneurship). Women mainly appear drawn into entrepreneurship for economic reasons (e.g., earning potential), the need for achievement and self-expression, or the availability of strong social-support networks. In particular, women without dependents tend to become entrepreneurs to pursue career goals (Patrick et al., Citation2016); whereas, women who are married or have children often become entrepreneurs to find a better balance between work and family (Joona, Citation2017; Lim, Citation2019; Noseleit, Citation2014). Women with care responsibilities appreciate the flexibility and autonomy promised by self-employment (Budig, Citation2006; Patrick et al., Citation2016; Zapalska, Citation1997). This preference also appears to be linked to dominant gender norms that typically allocate domestic roles, including unpaid care work, to women, who might leave traditional employment contexts to minimize role strain and conform to conceptions of a “proper” caretaker (Wall & Arnold, Citation2007). Entrepreneurship by women who also have care responsibilities may be influenced by motherhood penalties in labor markets too. That is, women’s relative wages begin to decline once they have children, which may motivate particularly skilled women to pursue the potentially higher financial rewards of entrepreneurship (Yang et al., Citation2023). Cultural and institutional barriers in labor markets thus can pull or push women into entrepreneurship. Notably, the prevalence of women entrepreneurship tends to be higher in less-gender-egalitarian countries (Brieger & Gielnik, Citation2021; Klyver et al., Citation2013).Footnote3

In turn, women entrepreneurs arguably should enjoy less work–family conflict than either women employees or men entrepreneurs. For example, U.S. women entrepreneurs report less work pressure and a greater level of mental health (Beutell, Citation2007), and as Lim (Citation2019) demonstrates empirically, women entrepreneurs enjoy more flexibility in their work locations, hours, and schedules than employed women, enabling women entrepreneurs to spend an additional 2 hours per day on average with their children. These trends are not limited to the United States; women entrepreneurs in Spain have more time flexibility than employed women (Gimenez-Nadal et al., Citation2012), and in Canada, self-employment is negatively related to work–family balance for men entrepreneurs but not women entrepreneurs (Duncan & Pettigrew, Citation2012). In their cross-country analysis, Hofäcker et al. (Citation2013) report more significant work–family conflict for men entrepreneurs than for women entrepreneurs. Yet a study of self-employed people in Sweden, which is relatively gender-egalitarian, shows a more gendered division of labor in their households, compared with households with employed workers, such that women spend more time on unpaid work at home and less time on paid work than any other group, while men serve as “breadwinners” and spend a lot of time on paid work (Hagqvist et al., Citation2015).

Gender roles and gender egalitarianism

Social role theory highlights how gender norms, stereotypes, and role expectations influence individual behaviors by affecting children’s development but also by defining personal and professional environments in adulthood (Eagly & Wood, Citation1999, Citation2012; Gabriel & Gardner, Citation1999; Wood & Eagly, Citation2002). Different role expectations for men and women emerge from a gendered division of labor, reflecting “the specialization of each sex in activities for which they are physically better suited under the circumstances presented by their society” (Eagly & Wood, Citation2012, p. 465). Agricultural and manufacturing economies, which are physically demanding and highly labor intensive, relied on male strength and size as a prerequisite for economically productive activity while also subordinating women’s roles. The transition to knowledge-based service economies shifted work demands though, from physically strong to intellectually skilled labor (Eagly & Wood, Citation2012; Morris, Citation2015), leading to a weaker gender-based division of labor. Communication, problem-solving, and interpersonal skills are critical in knowledge-based service economies, creating greater demand for female employment, which has prompted increases in women’s relative wages and human capital, as well as substantial declines in their household working hours, reflecting a form of socioeconomic gender egalitarianism (Inglehart & Norris, Citation2003; Stoet & Geary, Citation2020).

Greater socioeconomic gender egalitarianism in turn encourages cultural gender egalitarianism. Whereas agricultural and industrial civilizations have tended to embrace more-traditional gender norms and values, the norms and values in knowledge economies are more gender equal, including support for women’s participation in politics and the economy, self-expression in and outside the workplace, and autonomy in sexuality and reproduction (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015; Inglehart & Norris, Citation2003; Stoet & Geary, Citation2020). In culturally gender-egalitarian contexts, gender norms are fairer and more favorable to women, and there is less discrimination against women. Greater gender equality in the household suggests a more equal distribution of household responsibilities (Cheraghi et al., Citation2019). This form of cultural gender egalitarianism represents a powerful global trend and a source of increased civil liberties and political rights for women (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015), which various actors argue should be enshrined in law (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015; Alexander et al., Citation2016; Sundström et al., Citation2017). Societies with more pronounced such efforts create more gender-egalitarian laws and policies. Against this background, more equal gender roles result from a triad of socioeconomic, cultural, and institutional gender egalitarianism (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015; Alexander et al., Citation2016; Brieger et al., Citation2019).

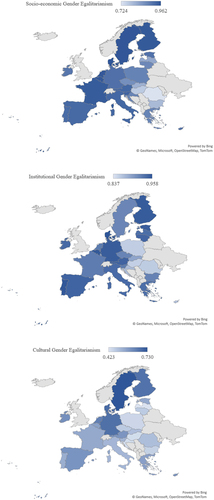

To illustrate these positive relationships, maps the gender-egalitarian conditions of the 27 European countries on which this study is based. Countries in Eastern Europe tend to be less gender egalitarian in all three domains than those in Western Europe. Previous research similarly indicates that traditional gender roles are more prevalent in Eastern Europe, which can limit women’s access to employment, education, and political participation (UNDP, Citation2020). In contrast, Western Europe tends to be more progressive, with gender norms and policies that support women’s empowerment (UNDP, Citation2020). In addition, women in Eastern Europe are underrepresented in politics and leadership compared with their counterparts in Western Europe. Eastern Europe tends to perform less well economically; its wider gender gap means that fewer women participate in the labor market or enter managerial positions. Overall, women in Western Europe encounter better socioeconomic outcomes, greater institutional protection, and more progressive cultural attitudes toward gender roles than women in Eastern Europe. Western Europe even ranks as the region with the highest level of gender equality in the world (World Economic Forum, Citation2021) and includes the four countries that ranked highest for gender equality in the 2020 Global Gender Gap Index: Iceland, Norway, Finland, and Sweden.

Conceptual framework and hypotheses

depicts our conceptual framework. Drawing on social role theory (Eagly & Wood, Citation1999, Citation2012), we start by establishing a negative relationship between female gender and well-being, mediated by experienced work–family conflict. Within this discussion and in line with previous research (Saridakis et al., Citation2014), we define gender as a binary category of socially constructed masculine and feminine characteristics, broadly mapped onto biological males and females with sex-specific features. This definition acknowledges that sex does not necessarily determine a person’s gender identity; for a small percentage (1%–2%) of people, their gender does not align with their biological sex (Murray, Citation2020). Approximately 0.5% of the U.S. adult population explicitly identifies as transgender (Herman et al., Citation2022).

By combining social role theory with gender egalitarianism literature, we postulate that gender-egalitarian country-level conditions mitigate women entrepreneurs’ greater work–family conflict and their diminished well-being during the COVID-19 pandemic. As mentioned, gender egalitarianism refers to the extent to which a society minimizes gender inequality (Emrich et al., Citation2004). We specify three types: socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural gender egalitarianism (Alexander et al., Citation2016; De Clercq & Brieger, Citation2022). The positive association between female gender and work–family conflict may be mitigated by gender-egalitarian, country-level conditions, which help women entrepreneurs reconcile work and family responsibilities, with beneficial consequences for their psychological well-being. Accordingly, we propose a moderated mediation dynamic, in which gender-egalitarian contexts buffer the negative effect of female gender on psychological well-being through work–family conflict.

Gender and work–family conflict

During the COVID-19 pandemic, stay and work-at-home mandates led to the closures of many schools and child and elderly care centers, such that the lines between work and family faded. For many entrepreneurs, these developments required them to take on additional roles and their households encompassed an intersection of work and home life. Whereas previous research mainly has identified less work–family conflict for women entrepreneurs than for their male counterparts (Duxbury & Higgins, Citation2001; Noor, Citation2004), we predict the opposite: During the pandemic, women entrepreneurs experienced more work–family conflict than their male counterparts. Women already tended to have more domestic responsibilities, but in response to shelter-at-home orders, they likely became even more involved in child and elderly care and housework; the pandemic substantially increased women’s household responsibilities (Del Boca et al., Citation2020). The resulting role conflicts, including work–family conflict, likely created substantial stress (De Clercq, Kaciak, et al., Citation2021).

Although there are manifold reasons women entrepreneurs might have been more affected by the COVID-19 pandemic, we expect gender norms and economic necessities to dominate. As noted, gender norms require women to bear the brunt of unpaid domestic and care work, and due to socialization processes, many people cling to traditional divisions of housework, even in times of crisis. According to Pleck’s (Citation1977) work–family role system model, family responsibilities are allowed to interfere more with women’s work than that of men. Societal gender norms thus anticipate that women entrepreneurs take care of their families first or at least balance work and family, while men entrepreneurs mainly fulfill a breadwinner role (DeMartino & Barbato, Citation2003; Georgellis & Wall, Citation2005; Marlow & Swail, Citation2014).Footnote4 The COVID-19 pandemic may have altered men entrepreneurs’ daily activities to a lesser extent; they could keep the focus on their business activities. They also are more likely to have partners who do not work outside the home, such that those partners could provide domestic support during the pandemic (Matzek et al., Citation2010).

In contrast, women entrepreneurs are less often the primary breadwinners; they tend to contribute to household income in a complementary way and adopt an adjusted workload that makes it possible to reconcile work and family (Craig et al., Citation2012; Joona, Citation2017; Lim, Citation2019). During the COVID-19 pandemic, widespread closures of schools and childcare facilities likely created additional burdens on women entrepreneurs, resulting in greater work–family conflict. But even if women entrepreneurs are not married and have no children, we predict their greater involvement in family support and care. Women’s greater prosociality is well documented; as a meta-analysis reveals, women exhibit stronger care orientations than men on average (Jaffee & Hyde, Citation2000), and they also appear more likely to express benevolence (“preservation and promotion of the welfare of individuals with whom one is close”) and universalism (“understanding, appreciation, tolerance, and protection for the welfare of all people and nature”) values (Schwartz & Rubel-Lifschitz, Citation2009). In line with social role theory, women’s greater care orientation may have been strongly activated during the pandemic, during which many people, such as family members, friends, neighbors, and colleagues, needed support. Greater involvement in care and support for others then may have been a factor in greater perceptions of work–family conflict.

Furthermore, a lack of financial resources or access can constrain women entrepreneurs’ efforts to limit work–family conflict. Stephan et al. (Citation2020) reveal that women-led businesses suffered more adverse consequences from the pandemic than men-led firms, such that 72 percent of women-led firms experienced reduced trading volume compared with 56 percent for men-led firms. Women entrepreneurs were 35 percent more likely to suffer income losses too (Graeber et al., Citation2021). In this sense, the pandemic may have exacerbated an initial difference, such that women tend to operate in care-oriented sectors, which already promise relatively lower growth and value (Marlow & McAdam, Citation2013). Such challenges evoke significant tension and stress, so concerns in the work domain likely spill over into personal lives and vice versa (De Clercq, Brieger, et al., Citation2021). Overall, we predict that women entrepreneurs, compared with men, are more likely to experience work–family conflict during the pandemic. This prediction is represented as Hypothesis 1 (H1):

H1: A positive relationship existsbetween being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and the experience of work–family conflict.

Work–family conflict and psychological well-being

The implications of work–family conflict on well-being in entrepreneurship settings are somewhat ambiguous. On the one hand, entrepreneurs tend to be more satisfied with their work and life than employees, due to their greater autonomy, flexibility, and job control (Annink & den Dulk, Citation2012; Brieger et al., Citation2020; König & Cesinger, Citation2015; Parasuraman & Simmers, Citation2001). Some research cites self-employment as a job resource, which entrepreneurs can leverage in their quest to find a better balance between work and family responsibilities and to overcome discriminatory barriers in unfavorable employment contexts (Beutell, Citation2007; Gimenez-Nadal et al., Citation2012; König & Cesinger, Citation2015). On the other hand, entrepreneurs often struggle to reconcile family and work commitments due to long working hours, increased workloads and job involvement, and significant time commitments (Annink et al., Citation2016; Bell & La Valle, Citation2003; König & Cesinger, Citation2015; Parasuraman et al., Citation1996). Thus, entrepreneurship might be more challenging than regular employment due to the additional work responsibilities it imposes (Nordenmark et al., Citation2012; Parasuraman & Simmers, Citation2001). The autonomy and flexibility associated with entrepreneurship then may hinder a good work–family balance (Annink & den Dulk, Citation2012; Parasuraman & Simmers, Citation2001; Parasuraman et al., Citation1996) because it effectively blurs the boundaries between work and private lives (Ashforth et al., Citation2000).

Notably, work–family conflict tends to prompt negative emotions or feelings about jobs or lives. Entrepreneurship research highlights the conflict between work and family as a significant stressor that adversely affects psychological well-being (De Vita et al., Citation2019; Jennings & McDougald, Citation2007). In particular, entrepreneurs’ experience of work–family conflicts may cause stress and depression, while also lowering the quality of their family life, job and life satisfaction, and energy levels (Grant-Vallone & Donaldson, Citation2001). We therefore predict that work–family conflict negatively affects the psychological well-being of entrepreneurs because when they confront this conflict, they feel less calm, relaxed, balanced, active, powerful, positively tuned, or energized. By diminishing positive emotional resources, work–family conflict may reduce well-being. In combination with our first hypothesis (H1), these arguments suggest a mediating role of work–family conflict role, which can explain why women entrepreneurs exhibit a state of lower psychological well-being than men entrepreneurs.

H2: A negative relationship exists between entrepreneurs’ experience of work–family conflict and their psychological well-being.

H3: The experience of work–family conflict mediates the negative indirect relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and psychological well-being.

Moderating role of gender-egalitarian contexts

Gender-egalitarian socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural conditions, measured at the country level, might influence gender gaps in work–family conflict and in turn psychological well-being.

Socioeconomic gender egalitarianism

When the macro environment is marked by smaller gender gaps in living standards, education, and life expectancies (Klasen & Schüler, Citation2011), women entrepreneurs should feel supported by the availability of valuable financial, skill-based, and physical resources that increase women’s ability to cope with difficult situations, including conflicting demands of work and family (Brieger et al., Citation2019). Such resources should diminish the chances that work and family demands conflict more intensely than is the case for men. Therefore, in countries with more-gender-egalitarian resource endowments, women’s capabilities for coping with the stressful interaction of their professional and private realms should be greater (Klasen & Schüler, Citation2011). In contrast, in countries marked by greater gender-based socioeconomic gaps, women entrepreneurs have fewer resources at their disposal to deal with challenges at the work–family interface, so they are more likely to experience work–family conflict, compared with their male counterparts.

Smaller gender-related gaps in living standards also should enable women entrepreneurs to deal better with conflicting work and family demands, because enhanced material resources make it easier to organize their lives in ways that prevent work-related stress from entering the family domain and vice versa (Agarwal & Lenka, Citation2015). Diminished gender gaps in education imply that women entrepreneurs can gather relevant competencies to run their companies efficiently and avoid a scenario in which they take work stresses home or family stresses to work (Eddleston & Powell, Citation2012; Michael & Pearce, Citation2009). With regard to physical health, women entrepreneurs who do not suffer diminished health status simply due to their gender will be better placed to handle physical challenges linked to running a company and household simultaneously (Parasuraman & Simmers, Citation2001). Two hypotheses arise from these arguments:

H4a: The positive relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and the experience of work–family conflict is moderated by a country’s socioeconomic gender egalitarianism, such that the relationship is weaker at higher levels of socioeconomic gender egalitarianism.

H4b: The negative indirect relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and psychological well-being, through the experience of work–family conflict, is moderated by a country’s socioeconomic gender egalitarianism, such that the indirect relationship is weaker at higher levels of socioeconomic gender egalitarianism.

Institutional gender egalitarianism

Institutional gender egalitarianism reflects the degree to which women enjoy valuable civil liberties, including the presence of a well-functioning justice system, access to private property, freedom of domestic mobility, and an absence of forced labor (Sundström et al., Citation2017). They have the right to complain about discriminatory treatment (Brieger et al., Citation2019) and formal laws confer fundamental rights and equal treatment (Alexander & Welzel, Citation2015; Alexander et al., Citation2016). Such gender egalitarianism then should mitigate some challenges for women entrepreneurs and reduce the chances that women would suffer more than men from the negative interference between work and family. Prior studies demonstrate how institutional arrangements can shape how women entrepreneurs experience both their professional and private functioning (Elam & Terjesen, Citation2010; Williams & Vorley, Citation2015). Formal rules granting women political rights and government expenditures on childcare services can influence women’s willingness to start their own companies (Goltz et al., Citation2015). The challenges linked to meeting work and family demands then might be lessened, because women function with explicit guarantees that they can and should leverage their skills toward being effective in both realms (Brieger et al., Citation2019). If women are protected by property rights and can rely on a well-functioning justice apparatus, women entrepreneurs also can shield their dedicated work efforts from appropriation, leaving them with more time to spend with their families. Ultimately, when institutional gender egalitarianism is high, the relationship between being a woman and experiencing work–family conflict should be weaker, compared with a scenario in which such protection mechanisms are unavailable. When women entrepreneurs cannot rely on regulatory policies to safeguard their business (Brieger et al., Citation2019; Sundström et al., Citation2017), they may experience greater difficulties balancing work and family demands. Integrating the predicted moderating role of institutional gender egalitarianism with the predicted mediating role of work–family conflict, we hypothesize the following:

H5a: The positive relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and the experience of work–family conflict is moderated by a country’s institutional gender egalitarianism, such that the relationship is weaker at higher levels of institutional gender egalitarianism.

H5b: The negative indirect relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and psychological well-being, through the experience of work–family conflict, is moderated by a country’s institutional gender egalitarianism, such that the indirect relationship is weaker at higher levels of institutional gender egalitarianism.

Cultural gender egalitarianism

Cultural gender egalitarianism indicates the presence of norms about the equal roles of men and women, including expectations that men have the same responsibilities as women in the family domain (Duflo, Citation2012). Culture, as reflected in gender roles, influences human behavior (Welter, Citation2011). When a country features cultural gender egalitarianism, women entrepreneurs are better positioned to share their duties, which should help them diminish the likelihood that they experience more work–family conflict than men, because men and women share the household burdens (Brieger et al., Citation2019). When gender norms support women’s equal rights, it becomes less likely that it will be entirely up to women entrepreneurs, and not others, to fulfill family duties (García & Welter, Citation2013). Furthermore, women may be more likely to speak up if they struggle to maintain a healthy balance between work and family (Agarwal & Lenka, Citation2015; Etheridge & Spantig, Citation2020) and voice their concerns to relevant stakeholders outside their family, who then may help the women to find pertinent solutions (Beutell, Citation2007; Eddleston & Powell, Citation2012). In contrast, in countries characterized by low levels of cultural gender egalitarianism, women entrepreneurs enjoy less normative support for sharing family duties and likely experience negative interference between work and family (Eddleston & Powell, Citation2012). That is, if cultural gender egalitarianism permeates society, it might generate pathways for women entrepreneurs to seek guidance on how to juggle the simultaneous demands of work and family (Agarwal & Lenka, Citation2015; Forson, Citation2013). Finally, normative support for women’s equal rights may lead women entrepreneurs to derive personal fulfillment from finding a healthy balance between work and family responsibilities (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). In the presence of cultural gender egalitarianism, women entrepreneurs may find it appealing to identify creative solutions for combining work and family responsibilities. Conversely, women entrepreneurs in countries with low cultural gender egalitarianism may feel less motivated to find novel solutions and thus experience more work–family conflict relative to men. Thus we propose the following hypotheses:

H6a: The positive relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and the experience of work–family conflict is moderated by a country’s cultural gender egalitarianism, such that the relationship is weaker at higher levels of cultural gender egalitarianism.

H6b: The negative indirect relationship between being a woman (versus man) entrepreneur and psychological well-being, through the experience of work–family conflict, is moderated by a country’s cultural gender egalitarianism, such that the indirect relationship is weaker at higher levels of cultural gender egalitarianism.

Method and data

Data

To test the hypotheses, we combine individual- and country-level data from the Eurofound’s Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Surveys (a Round 1 survey administered between April 9 and June 11, 2020, and a Round 2 survey administered between June 22 to July 27, 2020) and from the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Project, the Quality of Governance database, World Bank, the Oxford COVID-19 Government Response Tracker, and Eurobarometer Surveys. We selected respondents who reported being self-employed then combined their data with country-level data from the other sources. The final sample includes 5,754 entrepreneurs between 18 and 82 years of age of whom 61 percent are women, 44 percent have children in the household, and 68 percent are the sole proprietor of a business. The respondents come from 27 European countries, as listed in the Appendix ().

Measures

Female

Female is a dummy variable, such that being a woman is equal to 1 and being a man is equal to 0.

Work–family conflict

For the mediating variable work–family conflict, we relied on five items that capture the conflict that women entrepreneurs experience at the work–family interface, measured in Rounds 1 and 2 of the Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Surveys.Footnote5 The arguments that underpin the hypotheses apply to both work-to-family conflict and family-to-work conflict, so the measurement items entail both conflict types. In particular, respondents indicated how often they have (1) “kept worrying about work when you were not working,” (2) “felt too tired after work to do some of the household jobs which need to be done,” (3) “found that your job prevented you from giving the time you wanted to your family,” (4) “found it difficult to concentrate on your job because of your family responsibilities,” or (5) “found that your family responsibilities prevented you from giving the time you should to your job.” The 5-point, reverse-coded scale ranged from 1 = always to 5 = never. The work–family conflict score represents the mean of all items. The Cronbach’s alpha was .75.

Psychological well-being

This measure is the five-item WHO (World Health Organization) well-being index, which uses endpoints from 1 = at no time to 6 = all of the time for five items, captured in Rounds 1 and 2 of the Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Surveys.Footnote6 The items were (1) “I have felt cheerful and in good spirits,” (2) “I have felt calm and relaxed,” (3) “I have felt active and vigorous,” (4) “I woke up feeling fresh and rested,” and (5) “My daily life has been filled with things that interest me” (Janssen et al., Citation2013). The Cronbach’s alpha was .89.

Socioeconomic gender egalitarianism

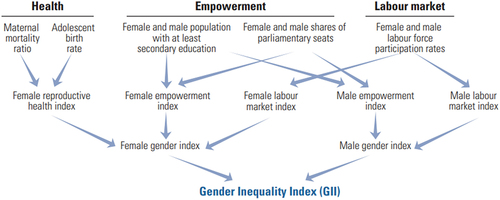

This measure is based on the UNDP’s gender inequality index for 2019, which captures gender gaps in three domains (Permanyer, Citation2013; UNDP, Citation2019): (1) health (maternal mortality ratio and adolescent fertility rate), (2) labor market (female and male labor force participation rates), and (3) empowerment (female and male population with at least secondary education and female and male shares of parliamentary seats). In , we display how the index, which features a 0–1 scale, is calculated; we reverse it so that higher values indicate more socioeconomic gender equality and empowerment.

Figure 3. Socioeconomic gender egalitarianism according to the UNDP’s (Citation2019) gender inequality index.

Institutional gender egalitarianism

We assess institutional gender egalitarianism with the women’s political empowerment index from the V-Dem database (Sundström et al., Citation2017). The V-Dem project defines women’s political empowerment as a process of increasing capacity for women, leading to greater choice, agency, and participation in societal decision-making. This index (0–1 scale) includes three equally weighted dimensions: (1) fundamental civil liberties, (2) women’s open discussion of political issues and participation in civil society organizations, and (3) descriptive representation of women in formal political positions. The data that we used to measure institutional gender egalitarianism refer to 2019.

Cultural gender egalitarianism

For cultural gender egalitarianism, we use six items from the Eurobarometer Surveys. Respondents indicate to what extent the European Union should prioritize (1) “tackling violence against women and girls,” (2) “supporting women’s economic empowerment,” (3) “strengthening women’s political participation,” (4) “supporting women’s sexual reproductive health and rights,” (5) “tackling discriminative attitudes against women,” and (6) “supporting access to education for women and girls.”Footnote7 The Cronbach’s alpha was .71. We calculated country scores as population averages (arithmetic mean) on a 0–1 index. The Eurobarometer data refer to 2018 (June–July, Eurobarometer 89.3).

Control variables

Following prior research, we control for several individual- and country-level characteristics. At the individual level, we control for an entrepreneur’s age (continuous), household size (five categories, from 1 = single to 5 = more than four members), tertiary education (1 = yes, 0 = no), savings (1 = yes, 0 = no), and general health (1 = very good, 5 = very bad). We also control for whether there are children in the household (1 = yes, 0 = no). Older and more-educated entrepreneurs tend to be happier and report lower work–life imbalances (De Clercq, Brieger, et al., Citation2021). Also, entrepreneurs with higher incomes are more satisfied with their jobs and lives (Brieger et al., Citation2020). De Clercq, Brieger, et al. (Citation2021) show that household size tends to be negatively related to well-being, and Shim et al. (Citation2012) find a positive relationship between saving and well-being. Berrill et al. (Citation2021) indicate that financial problems are strongly associated with poor well-being for self-employed workers. Research documents a strong effect of perceived health on well-being before and during the pandemic (O’Connor et al., Citation2021; Schröder, Citation2020). Notable differences in well-being and working conditions arise for entrepreneurs with employees versus without employees (van der Zwan et al., Citation2020), so we add a dummy variable, solo entrepreneur (1 = entrepreneur has no employees, 0 = entrepreneur has employees). At the country level, we control for gross domestic product per capita, which is an important predictor of well-being (Frey & Stutzer, Citation2010) and for a country’s policy stringency in response to the pandemic, using the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker project’s COVID-19 stringency index. This index combines nine policy responses during the pandemic, such as school and workplace closures, restrictions on public gatherings, mask wearing, and international travel controls (Mathieu et al., Citation2020); it takes the average score on the nine metrics, which can range from 0 to 100, and a higher score indicates a stricter response.

Data analysis

We use ordinary least squares with bootstrapping resampling (5,000 resamples) for the 27 countries in the sample to test our hypotheses. Replications were based on the 27 countries, accounting for data clustering. To test the significance of indirect effects formally, we applied bootstrapping (5,000 resamples) with Stata’s gsem command. Our data set is nested (individual respondents embedded in countries), so we check to see whether multilevel modeling is required by estimating the between-country variance of the mediating (work–family conflict) and dependent (psychological well-being) variables. With two intercept-only models for both variables, we calculate the intraclass correlation coefficients; only 4.0 percent of work–family conflict variations and 3.3 percent of psychological well-being variations lie between countries. Thus, there is not enough between-country variance to warrant multilevel modeling (Hox et al., Citation2017). As a robustness check though, we performed it and found consistent results, with similar significance (results available on request). For the moderated mediation analysis, we use bootstrapping with 5,000 resamples to test the significance of the conditional indirect relationships at low, middle, and high levels of the moderators (MacKinnon et al., Citation2004).

Results

Main results

contain the descriptive statistics and correlations. We find significant correlations of psychological well-being with work–family conflict (r = −0.386; p < .01), being a woman entrepreneur (r = −0.061; p < .01), and the three moderating variables of socioeconomic (r = 0.047; p < .01), institutional (r = 0.041; p < .01), and cultural (r = 0.059; p < .01) gender egalitarianism. Furthermore, work–family conflict is positively correlated with being a woman (r = 0.048; p < .01), with socioeconomic gender egalitarianism (r = 0.061; p < .01), and with institutional gender egalitarianism (r = 0.038; p < .01) but negatively (though not significantly) correlated with cultural gender egalitarianism (r = −0.019; p < .01).

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

Table 2. Correlations.

The results of the mediation and moderation analyses in offer support for H1, in that women entrepreneurs report more work–family conflict than men entrepreneurs (b = 0.100; p < .01, Model 1). Model 3 reveals that work–family conflict is significantly and negatively related to psychological well-being (b = −0.502; p < .01), in support of H2. Model 3 also indicates a partial mediating role of work–family conflict in the relationship between being a woman entrepreneur and psychological well-being: If we control for work–family conflict, this effect decreases by 30 percent (from b = −0.165; p < .01, to b = −0.114; p < .01). The bootstrapped indirect effect of being a female entrepreneur on psychological well-being through work–family conflict is significant too (b = −0.050; p < .01), and the confidence interval of the bootstrapped indirect effect does not contain 0 [−0.076; −0.024]. Accordingly, in support of H3, work–family conflict mediates the relationship between being a female entrepreneur and psychological well-being.

Table 3. Mediation and moderation analysis results.

Models 4–6 reveal the results of the moderation analyses. A country’s socioeconomic (b = −0.657; p < .05), institutional (b = −1.229; p < .05), and cultural (b = −0.852; p < .01) gender egalitarianism all mitigate the positive relationship between being a woman and work–family conflict. Gender differences in work–family conflict tend to be smaller in gender-egalitarian contexts (Baker & Welter, Citation2020), in which women are socioeconomically, institutionally, or culturally more equal to men. A comparison of the slopes in , Panels a–c, also indicates larger gender gaps in work–family conflict in macro-level contexts in which women’s socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural gender egalitarianism are low. Women and men entrepreneurs report more-similar levels of work–family conflict when they live in countries marked by women-friendly socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural conditions, as we predicted in H4a, H5a, and H6a. Notably, men and women entrepreneurs from more-socioeconomic-gender-egalitarian countries report higher levels of work–family conflict than men and women entrepreneurs in less egalitarian contexts (Panel a). Men entrepreneurs in particular seem to face higher work–family conflict in contexts that are more egalitarian in the socioeconomic domain, compared with their counterparts in less egalitarian countries. In contrast, women entrepreneurs experience particularly high work–family conflict when they live in countries with low levels of institutional and cultural gender egalitarianism (Panels b and c) compared with female entrepreneurs in countries with high such levels.

provides the results of the moderated mediation analysis we used to test the indirect effects of gender on psychological well-being at low, middle, and high levels of the three moderating variables (socioeconomic, institutional, and cultural gender egalitarianism). We find evidence of moderated mediation: The negative indirect effect of gender on psychological well-being, through work–family conflict, is weaker at higher versus lower levels of socioeconomic (b = −0.027 versus b = −0.073), institutional (b = −0.026 versus b = −0.074), and cultural (b = −0.020 versus b = −0.081) gender egalitarianism. This mitigating effect is particularly pronounced for cultural gender egalitarianism; the indirect effect becomes insignificant at high levels of this condition (p = .151; confidence interval includes 0 [−0.047; 0.007]). Thus, we find strong support for H4b and weak support for H5b and H6b.

Table 4. Moderated mediation analysis results.

Post hoc results

We run several post hoc analyses to test the robustness of our theorizing and findings, as well as to provide more nuanced insights into the relationship of gender, work–family conflict, and well-being. First, we ran the focal analysis separately for entrepreneurs with and without their own employees and for entrepreneurs with and without children. As we detail in in the Appendix, women entrepreneurs with employees reported more work–family conflict than men entrepreneurs with employees (b = 0.183; p < .01), suggesting they had more problems juggling demands of family and employees during the pandemic. Gender differences in work–family conflict were not significant in the sample that only included entrepreneurs who work alone (b = 0.056; ns), so the difficulties faced by men and women solo entrepreneurs, who typically have fewer resources and are more vulnerable, appear comparable. Moreover, the results in indicate that gender differences in work–family conflict were greater among entrepreneurs with children than those without children, and the effect was weakly significant in the sample without children (b = 0.146; p < .01 versus b = 0.042; p < .10). Women entrepreneurs with children were particularly stressed during the pandemic.

Second, we checked for any differences among entrepreneurs with or without the ability to save money and those with or without tertiary education. Women entrepreneurs who could save money experienced higher levels of work–family conflict than men entrepreneurs (b = 0.112; p < .01; ); it seems that particularly ambitious women entrepreneurs may have faced serious difficulties in balancing family and work responsibilities during the pandemic. Among entrepreneurs without savings, we find only weakly significant differences in work–family conflict between women and men (b = 0.071; p < .10; ). The patterns of results are very similar for samples of entrepreneurs with and without a tertiary education degree ( and ).

Third, we consider two alternative measures of well-being: life satisfaction (), measured on a 10-point scale (1 = “very unsatisfied,” 10 = “very satisfied”), and happiness (), measured with a single item on a 10-point scale (1 = “very unhappy,” 10 = “very happy”). The results remain similar to our findings based on a measure of psychological well-being (WHO-5 Well-Being Index). We find significant indirect effects of gender on both life satisfaction and happiness through work–family conflict, and the gender differences in work–family conflict are attenuated in gender-egalitarian contexts, resulting in significant, moderated, indirect effects.

Fourth, to address potential intersectional effects, we run a post hoc analysis with three-way interaction models. The interplay of gender and gender-egalitarian contexts for predicting work–family conflict depends on two control variables: age and being a solo entrepreneur.Footnote8 Specifically, we find positive (mitigating), significant, three-way interaction effects among gender, age, and institutional and cultural gender egalitarianism. In combination with the negative two-way interaction terms in , the positive sign of these three-way interaction terms indicates that age diminishes the beneficial effect of gender egalitarianism on the experience of diminished work–family conflict, possibly due to a general preference for more traditional gender roles and norms among older segments of society (Inglehart & Norris, Citation2003). In addition, we find a significant negative (reinforcing) three-way interaction effect among gender, being a solo entrepreneur, and cultural gender egalitarianism. Women entrepreneurs without employees appear to have benefited particularly from gender-egalitarian contexts during the pandemic, in terms of diminishing their work–family conflict.

Discussion

Contrary to previous research, which asserts that men entrepreneurs experience more work–family conflict than women entrepreneurs (Beutell, Citation2007; Duncan & Pettigrew, Citation2012; Gimenez-Nadal et al., Citation2012; Lim, Citation2019), we clarify that during the COVID-19 pandemic, women entrepreneurs encountered greater work–family conflict, which led to gender-specific differences in psychological well-being. The COVID-19 pandemic seemingly functioned as a resource strain for entrepreneurs, in that it blurred boundaries between work and family spheres. The resulting challenge was especially acute for women entrepreneurs, such that they suffered from conflicting work and family demands and diminished well-being to a greater extent than their male counterparts. Negative interference between work and family responsibilities induces significant hardships during a crisis and likely exacerbates the need for women to comply with predefined gender roles and expectations. Many women become entrepreneurs to enjoy the flexibility that entrepreneurship offers, but as we show, this choice can generate strong adverse outcomes and manifests in compromised work–family balance and well-being.

These findings match literature that highlights the effects of work–family balance on entrepreneurs’ well-being (Agarwal & Lenka, Citation2015; Beutell, Citation2007) but challenge assumptions that women entrepreneurs always experience fewer imbalances than men entrepreneurs (Duncan & Pettigrew, Citation2012; Gimenez-Nadal et al., Citation2012; Hofäcker et al., Citation2013). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, women entrepreneurs might have reported lower levels of work–family conflict, and in supplementary analyses, we tested the notion that men entrepreneurs experience greater work–family conflict than women entrepreneurs. These findings do not relate directly to our hypotheses, but they reveal that, in pre–COVID-19 data contained in the Global Entrepreneurship Monitor’s (GEM) Adult Population Survey 2013, women entrepreneurs reported fewer work–family conflicts on average than men entrepreneurs, across all 27 European countries we studied. Another supplemental analysis involving data from the Flash Eurobarometer 470 survey collected in 2018 reveals a negative relationship between being a woman entrepreneur and work–life conflict. These results (available on request) strongly suggest that in the past, women entrepreneurs experienced less work–family tension than their male counterparts. But as our novel findings show, greater work–family conflict and less well-being arose for them during the pandemic, likely due to changes in both work demands (e.g., working from home) and family demands (e.g., homeschooling), which were reinforced by persistent, gendered role expectations with respect to responsibilities for housework and care (Eagly & Wood, Citation2012).Footnote9

Gender-egalitarian conditions can significantly reduce gender differences in work–family conflict and psychological well-being. In gender-egalitarian contexts, women and men entrepreneurs exhibit more-similar work–family conflict levels and psychological well-being scores. A supportive environment thus appears critical to reducing differences in work–family conflict and well-being. When women are socioeconomically (education and financial means), institutionally (governmental support and important rights), and culturally (equality attitudes and norms) empowered, women entrepreneurs can gather the resources and support they need to overcome resource drainage and can better balance work and family responsibilities. Consistent with gender role theory (Eagly & Wood, Citation1999), contexts characterized by such gender egalitarianism reduce the gender gap that exists with respect to challenges at the work–family interface and subsequent threats to psychological well-being.

As mentioned previously, an intriguing finding is that in contexts marked by socioeconomic egalitarianism, men entrepreneurs reported higher levels of work–family conflict than men entrepreneurs living in less inegalitarian contexts. In socioeconomic gender-egalitarian contexts, where women’s labor force participation tends to be higher, the partners of men entrepreneurs may be more likely to join the labor force, which limits their availability and requires men entrepreneurs to take on household and childcare tasks. Del Boca et al. (Citation2020, p. 1001) find that childcare activities were equally shared by Italian working couples during the COVID-19 pandemic and that men’s involvement in household activities critically depended on their partner’s work, such that “men whose partners continue[d] to work at their usual workplace spen[t] more time on housework than before.” If men entrepreneurs gained flexibility by staying home during the pandemic, they might have experienced increased work–family conflict in gender-egalitarian contexts, unlike their female counterparts.

This finding may imply relevant changes in gender norms and expectations in societies with higher levels of gender egalitarianism. Although women may continue to spend more hours on domestic tasks and experience higher work–family conflict, men might be more involved in housework than in the past, due to the COVID-19 pandemic. King and Frederickson (Citation2021, p. 4) point out that “the proportion of parents who report sharing domestic chores equally has increased since before the pandemic. As a result, the fraction of families in which mothers are primarily responsible for household labor has decreased substantially.” Our findings mirror this assertion, at least for countries that are gender egalitarian in the socioeconomic domain, by identifying strong positive differences in work–family conflict between men in egalitarian versus inegalitarian countries (, Panel a). In contrast, for institutional and cultural domains (, Panels b and c), we find positive differences in work–family conflict between women in inegalitarian versus egalitarian countries. In other words, women entrepreneurs in inegalitarian contexts experience more work–family conflict than women entrepreneurs in egalitarian contexts, potentially due to unequal distributions of household tasks between women and men in inegalitarian macro-level contexts.

Implications

This study adds to prevailing notions about gender differences in the perceived imbalances between the work and private spheres. Previous research has highlighted the positive aspects of entrepreneurship for women in terms of work–life balance (Georgellis & Wall, Citation2005; Lim, Citation2019); we establish its adverse implications during a crisis. Our findings accordingly can help entrepreneurship scholars consider how a crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic might promote and perpetuate gendered behaviors, with notable disadvantages for women (Marlow & Swail, Citation2014). We specify that women entrepreneurs suffer substantial psychological strain during a pandemic, a challenge that is exacerbated in gender-inegalitarian contexts. As our findings reveal, a crisis can perpetuate traditional gender attitudes that entrench social norms, ascribe domesticity to women and economic value to men, and reinforce ideas about the “appropriate” division of labor, at work or at home (Schröder, Citation2020).

Although our study highlights gender inequality as a serious issue that deserves critical attention, the findings from our preliminary analysis of GEM and Flash Eurobarometer data (Section 2.2) should alert researchers that it is not only women but also men entrepreneurs who confront significant work–family imbalances. Additional research into why entrepreneurs appear willing to sacrifice family time to work extremely long hours could be an interesting endeavor. Many discourses emphasize the willingness of women, and especially mothers, to make sacrifices, but men might experience significant pressures too, due to conflicting expectations, namely, to conform to an archetype of a primary breadwinner who works long hours but also to take on increasingly modern roles in the family. Combining these expectations may lead to intense overload and stress (Pace & Sciotto, Citation2021). Our study thus introduces some possible adverse consequences of gender egalitarianism for the work–family conflict experienced by men entrepreneurs. That is, men score worse on work–family conflict in socio-economic gender-egalitarian societies than men in less egalitarian societies. This point is not to say, of course, that gender egalitarianism is bad for societies – quite the contrary. But the difficulties that men entrepreneurs experience in balancing work and family in gender-egalitarian societies deserve more research attention.

In terms of practical implications, this study outlines pertinent challenges that entrepreneurs may face, why gender differences in work–family conflict and well-being exist, and the conditions in which they can be reduced. We highlight the importance of gender-egalitarian, country-level conditions for reducing gender differences in work–family conflict and well-being. When working from home is the new normal, work–family conflicts increase, so flexible work arrangements, government support (e.g., leave), and benefits that include childcare subsidies (Vaziri et al., Citation2020) might prove effective in helping women (and men) entrepreneurs balance family and work better. Our study also sheds light on a rarely discussed outcome: Entrepreneurship may perpetuate traditional gender norms. Women who are married or have children are more likely to be self-employed, which helps them balance work and family demands. The impact of entrepreneurship on gender roles appears similar to that of part-time work, which women also may choose to achieve a better work–life balance. Both entrepreneurial activity and part-time work thus may reflect women’s decisions to reduce their working hours for family and personal reasons (Beham et al., Citation2019).

At the policy level, our study suggests that women entrepreneurs might be more sensitive to pandemic-related crises. Without proper attention to this issue or effective recovery strategies, existing gender-based well-being differences seem likely to intensify. work–family conflict offers a critical reason for this difference, such that it represents a root cause of the problem of diminished well-being (International Trade Centre, Citation2020). The root cause of women’s work–family conflict may stem from engrained perceptions of gendered roles and socialization processes, which lead to diminished well-being. As such, there may be a dual burden for women: They must adhere to societal norms around women’s roles but also enact and abide by conceptualizations of entrepreneurship that valorize masculinity (Marlow & Swail, Citation2014; Swail & Marlow, Citation2018). Policymakers might consider supportive infrastructures (e.g., egalitarian entrepreneurial ecosystems) that help women entrepreneurs, and also men entrepreneurs, balance work and family responsibilities during times of crisis.

An emphasis on gender-egalitarian environmental conditions in particular should help women, even outside entrepreneurship. Some gender barriers in employment cause women to shift toward self-employment, such as fewer corporate career opportunities, corporate wage differentials, unfriendly corporate environments, no (or unpaid) maternity leave, sexual/verbal harassment, and routine work with less leeway to meet family demands (Lim, Citation2019). Mothers, who are particularly vulnerable, reduced their work hours more than fathers during the pandemic and even quit their jobs to care for their families (The Economist, Citation2021; Seck et al., Citation2021). Improvements in such aspects thus could help women in many ways.

Limitations and further research directions

The limitations of this study create directions for further research. To describe these limitations, first, the cross-sectional design of our study does not allow us to establish causal mechanisms. We know that people’s psychological well-being declined with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic and that women were among the hardest hit (Zacher & Rudolph, Citation2020). According to Etheridge and Spantig (Citation2020), the pandemic prompted a significant drop in the mental well-being of women. Continued longitudinal research should investigate pandemic effects on entrepreneurs’ work–family conflicts and well-being over time, to establish how the relationships of gender, work–family conflicts, and well-being changed due to the crisis.

Second, we focus on entrepreneurs’ psychological well-being from a generic perspective without differentiating the patterns of self-employment that entrepreneurs adopt, such as online versus offline services, production versus service industries, necessary versus luxury providers, the scope of digital adaptability, size of the business (physical and virtual infrastructure, annual profit margin), or stage of entrepreneurship (early vs. established). Yet COVID-19 affected businesses disproportionately. A larger proportion of market share shifted to big or giant companies (e.g., Zoom, Amazon, Netflix), while small- and medium-sized enterprises struggled to survive. It also catalyzed some radical digital transformations (Korsgaard et al., Citation2020). Therefore, continued research could examine nuances of self-employment and how they influence the relationships we investigated.

Third, female and men entrepreneurs are diverse groups, and their work–family conflict and psychological well-being differ, according to the influences of various factors such as race, ethnicity, immigration status, social class, family support, and whether the entrepreneur’s spouse works or stays home (Leung et al., Citation2020; Shelton, Citation2006). These factors are not available from the Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Survey data set; we call for research that addresses such intersectionality in detail. We can account for the effects of a relatively limited set of control variables though.

Fourth, the relatively low R-squared values suggest that our analysis does not include all possible factors that might affect work–family conflict or psychological well-being. This empirical weakness relates to the specificity of the data set from which we drew; it also is in line with our overall goal to explain variation in work–family conflict and psychological well-being instead of predicting specific values of these outcome variables. Nonetheless, we acknowledge the need for ongoing research that introduces additional explanatory factors. For example, personality traits such as the need for autonomy, proactiveness, or risk-taking likely affect the interplay of gender, work–family conflict, and psychological well-being; research could address how such traits might be leveraged to help entrepreneurs cope with crises (Ketchen & Craighead, Citation2020). Relatedly, our study does not account for the motives that drove entrepreneurs to start their own companies. If they did so to create social value and benefit society, they might be affected differently by the COVID-19 crisis. For these entrepreneurs, well-being even might increase during a crisis, because they sense that their efforts are worthwhile, despite work–family conflicts. Brieger et al. (Citation2021) find that entrepreneurs who create social value report higher work-related well-being levels. Thus, entrepreneurs’ prosocial motives and activities might affect the associations of work–family conflicts, psychological well-being, and entrepreneurship during times of crisis. Continued research should test these links.

Fifth, we highlight the positive role of gender-egalitarian contexts for women entrepreneurs; gender egalitarianism positively affects the quality of entrepreneurship among women. This beneficial role contrasts with previous research that documents a beneficial effect of gender inegalitarianism on the quantity of entrepreneurship among women compared with men. Klyver et al. (Citation2013) and Thébaud (Citation2015) find that in gender-inegalitarian contexts, women are relatively more likely to start their own companies because they have fewer alternative, attractive options in the formal labor market; as entrepreneurs, they may face less discrimination and receive more support. Brieger and Gielnik (Citation2021) also show that entrepreneurship is a secondary strategy for female natives with more economic opportunities at hand but a primary employment strategy for female immigrants, who lack many alternatives. We call for more research at this nexus of gender, country-level gender egalitarianism, and the quantity and quality of entrepreneurship, which also might clarify the role of different characteristics, such as age, education, or immigration status.

Sixth, our data set spans 27 EU countries, with large, representative samples. But we can establish external validity only for each country’s context. Notably, entrepreneurship depends strongly on national cultures, so our study requires further replications in other regions (Henry et al., Citation2021). Gender equality in Europe is comparatively high by international standards (Inglehart & Norris, Citation2003), so our empirical tests are conservative; the moderating effects of gender egalitarianism might be even stronger among samples that include countries from around the world. However, the extent to which our results are universally valid remains to be established. A related, useful extension would be to assess how entrepreneurs, women and men alike, interpret gendered processes that permeate society and how these interpretations affect their experience of work–family conflict and psychological well-being.

Conclusion

A key reason women pursue entrepreneurial career paths involves flexibility, which helps them resolve conflicts between work and family. Yet the results of our study show that, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, women perceived more significant work–family conflicts than men, with negative consequences for their psychological well-being. This points to the negative implications of gendered role expectations during a crisis. Our study also highlights the importance of gender-egalitarian conditions for addressing gender disparities in work–family conflict and psychological well-being. It thus offers greater insight into how the challenges that women entrepreneurs encounter depend on societal-level differences.

Acknowledgments

We thank the editor, Dr. Sílvia Costa, and the two reviewers for their constructive comments and very helpful suggestions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 Greenhaus and Beutell (Citation1985) identify three sources of work–family conflict: (1) time-based, such that time devoted to one role cannot be used to fulfill other roles; (2) strain-based, in that tension in one role affects performance in the other; and (3) behavior-based, as occurs when behavioral styles at work, such as authority, are incompatible with behaviors needed at home. Long working hours, high work intensity, intense (physical, emotional, cognitive) efforts to accomplish work goals, and job uncertainties all can induce time-, strain-, or behavior-based conflicts, with adverse consequences for individual well-being (Dijkhuizen et al., Citation2016).

2 Consistent with prior studies (Brieger et al., Citation2020; Hsieh et al., Citation2017; Stephan, Citation2018), we use the terms “entrepreneurship” and “self-employment” interchangeably. Entrepreneurship is typically measured as self-employment, business ownership, or business creation (Hsieh et al., Citation2017); it is acknowledged as a risky activity. An entrepreneur is a person who starts, organizes, and manages the business in pursuit of profit. Self-employment is the most established measure of entrepreneurship. It refers to the occupational choice of people who decide to work on their own account and take on the risks for such endeavors (Stephan, Citation2018).

3 Thébaud (Citation2015) argues that entrepreneurship is a “plan B” employment strategy for women in the presence of gender-equal institutions that promote staying in paid employment. Klyver et al. (Citation2013) also find that gender gaps in entrepreneurship are greater in gender-egalitarian countries, where women have more opportunities in the formal labor market.

4 Other research argues that women’s greater focus on caring for family members and interest in social relationships might stem from innate differences in sex hormones, neurocognitive functions, or personality traits. Strong mother – infant bonding is a feature of virtually all mammals (Numan & Young, Citation2016), and infant girls already show signs of a stronger people orientation (more eye contact, responsiveness to maternal vocalization, attention to objects with human attributes) than infant boys (Alexander & Wilcox, Citation2012; Lutchmaya et al., Citation2002). Women’s educational and vocational choices similarly may reflect their social nature; on average, women tend to be attracted to vocations involving people, whereas men prefer vocations centered on things. The female – male ratio in “people jobs” is particularly high in more gender-egalitarian environments, where women can express themselves more readily, but women might not embrace such preferences to the same extent in gender-discriminatory environments (Murray, Citation2020). This well-known “equality paradox” is particularly pronounced in Scandinavian countries where gender equality is very high, but people tend to make sex-typical career choices (Stoet & Geary, Citation2020; Stoet et al., Citation2022). Each of these issues can contribute to different social role expectations within and across societies and thus to certain forms of gender inegalitarianism.

5 The Eurofound Living, Working and COVID-19 e-Survey used different time frames to capture work–family conflict. In Round 1, the question prompt read, “How often in the last two weeks have you…?” whereas in Round 2, it read, “How often in the last month have you…?” The different time frames are purposeful; Round 1 was designed to exclude pre – COVID-19 levels of work–family conflict.

6 The question prompt for this measure read, “Please indicate for each of the five statements which is closest to how you have been feeling over the last two weeks.” for both Rounds 1 and 2. The different time frames used in Round 2 to measure work–family conflict (“last month”) versus psychological well-being (“last two weeks”) aligns with our conceptual focus on explaining the effect of work–family conflict on psychological well-being. Yet the time frames for the two variables overlap in Round 2 (“last month” versus “last two weeks”) and are identical in Round 1 (“last two weeks”), which represents an empirical weakness of the design of the e-Surveys.

7 The use of the term “should” is critical, because this measure aims to capture expectations or norms about what is acceptable with respect to gender egalitarianism, consistent with the distinction between values (“should be”) and practices (“as is”) in the well-established GLOBE project (House et al., Citation2004). The cultural gender egalitarianism index we use strongly correlates with other cultural characteristics that capture gender-egalitarian values, such as (1) Welzel’s emancipative values index (r = .75, p = .00, N = 16), (2) Hofstede’s femininity dimension (r = .47, p = .04, N = 20), (3) the GLOBE’s gender egalitarianism values (r = .46, p = .08, N = 16), and (4) the single item, “When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women” (r = −.52, p = .01, N = 27), from the World Values Survey.

8 These results are available on request.

9 The World Economic Forum (Crotti et al., Citation2021) predicts that the impacts of COVID-19 extended the timeframe for closing the global gender gap from 99.5 to 135.6 years.

References

- Agarwal, S., & Lenka, U. (2015). Study on work–life balance of women entrepreneurs – review and research agenda. Industrial and Commercial Training, 47(7), 356–362. https://doi.org/10.1108/ICT-01-2015-0006

- Alexander, A. C., Inglehart, R., & Welzel, C. (2016). Emancipating sexuality: Breakthroughs into a bulwark of tradition. Social Indicators Research, 129(2), 909–935. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1137-9

- Alexander, A. C., & Welzel, C. (2015). Eroding patriarchy: The co-evolution of women’s rights and emancipative values. International Review of Sociology, 25(1), 144–165. https://doi.org/10.1080/03906701.2014.976949

- Alexander, G. M., & Wilcox, T. (2012). Sex differences in early infancy. Child Development Perspectives, 6(4), 400–406. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1750-8606.2012.00247.x

- Annink, A., & den Dulk, L. (2012). Autonomy: The panacea for self-employed women’s work-life balance? Community, Work & Family, 15(4), 383–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668803.2012.723901

- Annink, A., den Dulk, L., & Steijn, B. (2016). Work–family conflict among employees and the self-employed across Europe. Social Indicators Research, 126(2), 571–593. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-0899-4

- Ashforth, B. E., Kreiner, G. E., & Fugate, M. (2000). All in a day’s work: Boundaries and micro role transitions. Academy of Management Review, 25(3), 472–491. https://doi.org/10.2307/259305

- Baker, T., & Welter, F. (2020). Contextualizing entrepreneurship theory. Routledge.

- Beham, B., Drobnič, S., Präg, P., Baierl, A., & Eckner, J. (2019). Part-time work and gender inequality in Europe: A comparative analysis of satisfaction with work–life balance. European Societies, 21(3), 378–402. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616696.2018.1473627

- Bell, A., & La Valle, I. (2003). Combining self-employment and family life. Policy Press.

- Berrill, J., Cassells, D., O’Hagan-Luff, M., & van Stel, A. (2021). The relationship between financial distress and well-being: Exploring the role of self-employment. International Small Business Journal, 39(4), 330–349. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242620965384

- Beutell, N. J. (2007). Self-employment, work–family conflict and work–family synergy: Antecedents and consequences. Journal of Small Business & Entrepreneurship, 20(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2007.10593403

- Block, J. H., Fisch, C., & Hirschmann, M. (2022). The determinants of bootstrap financing in crises: Evidence from entrepreneurial ventures in the COVID-19 pandemic. Small Business Economics, 58(2), 867–885. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-020-00445-6

- Brieger, S. A., De Clercq, D., Hessels, J., & Pfeifer, C. (2020). Greater fit and a greater gap: How environmental support for entrepreneurship increases the life satisfaction gap between entrepreneurs and employees. International Journal of Entrepreneurial Behaviour & Research, 26(4), 561–594. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEBR-03-2019-0185

- Brieger, S. A., De Clercq, D., & Meynhardt, T. (2021). Doing good, feeling good? Entrepreneurs’ social value creation beliefs and work-related well-being. Journal of Business Ethics, 172(4), 707–725. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-020-04512-6

- Brieger, S. A., Francoeur, C., Welzel, C., & Ben-Amar, W. (2019). Empowering women: The role of emancipative forces in board gender diversity. Journal of Business Ethics, 155(2), 495–511. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-017-3489-3

- Brieger, S. A., & Gielnik, M. M. (2021). Understanding the gender gap in immigrant entrepreneurship: A multi-country study of immigrants’ embeddedness in economic, social, and institutional contexts. Small Business Economics, 56(3), 1007–1031. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00314-x

- Budig, M. J. (2006). Intersections on the road to self-employment: Gender, family and occupational class. Social Forces, 84(4), 2223–2239. https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2006.0082

- Cheraghi, M., Adsbøll Wickstrøm, K., & Klyver, K. (2019). Life-course and entry to entrepreneurship: Embedded in gender and gender-egalitarianism. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 31(3–4), 242–258. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1551791

- Craig, L., Powell, A., & Cortis, N. (2012). Self-employment, work–family time and the gender division of labour. Work, Employment & Society, 26(5), 716–734. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017012451642