?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

There is a paucity of literature investigating the simultaneous relationships among R&D, innovation, and exports and assessing the separate roles of R&D and innovation from an empirical perspective. We address this research gap and contribute to the literature by examining the “learning to export” and “learning by exporting” hypotheses in SMEs and large firms. Using instrumental variable (IV) regressions and path analyses, the empirical assessment provides evidence that R&D and innovation should be regarded as two separate constructs. We also find significant mediating effects between R&D and Export via Innovation and between Export and R&D via Innovation only in the large company cohort. SMEs do not show evidence of simultaneity among R&D, innovation, and exporting nor do the results provide support for the “learning by doing” hypothesis in SMEs. Our findings assist in understanding how the variables interact across different firm sizes, which is important for targeted resource support and policies.

Introduction

Despite numerous firm-level studies examining the relationship between exporting, innovation and R&D activities, there is no consensus among scholars on the export–innovation–R&D nexus that would explain the unique drivers of firms’ competitive advantage. With respect to innovation, the literature reports firms that undertake innovation activities are more likely to export successfully and generate growth in firms (e.g., Chang & Webster, Citation2019; DiCintio et al., Citation2017; Gkypali & Tsekouras, Citation2015). The literature also examines linkages between R&D activities and export (Dai & Yu, Citation2013; Gashi et al., Citation2014; Máñez et al., Citation2015) as well as the use of R&D activities as an instrumental variable for innovation under the assumption that R&D does not directly affect export because it is solely an enabler of innovation (Ganotakis & Love, Citation2011; Lachenmaier & Wößmann, Citation2006). Further, some early studies use the concepts of “R&D” and “innovation” interchangeably and apply R&D as a proxy measure of innovation, making little distinction between R&D and innovation, considering both to be the same construct (Greenhalgh et al., Citation1994; Hirsch & Bijaoui, Citation1985; Smith et al., Citation2002).

On the other hand, endogenous innovation and growth framework argues that goal-directed, profit-seeking investments in knowledge play an important role in economic growth (Grossman & Helpman, Citation1994). This framework has enhanced understanding of trade-led innovations and R&D activities, resulting in the “learning by export” hypothesis (Aghion et al., Citation2022; Bustos, Citation2011; Verhoogen, Citation2008). So, while there is a plethora of literature that examines the relationship among exports, innovation, and R&D, there is no clear consensus on the export–innovation–R&D nexus, especially from the firm’s size perspective. The issue of contemporaneity among R&D, innovation, and exporting has received less attention and the literature remains unclear about the impact that R&D and innovation have, as separate constructs, on export performance and vice versa.

Accordingly, we address this research gap empirically by examining the export–innovation–R&D nexus within a single econometric framework. Hence, the primary objectives of the study are to test whether firms (1) “learn to export” and/or (2) “learn by exporting” (see Eliasson et al., Citation2012) across different firm sizes, thereby providing a better understanding of the drivers of competitive advantage. This assessment allows us to (1) gauge empirically the simultaneous relationships among R&D, innovation, and exporting in the two groups of firms and the direct and the mediating relationships (via innovation) between R&D and exporting as well as the possible feedback effects from exports to R&D and innovation and (2) to uniquely assess whether R&D is a separate input measure of innovation and exports rather than merely as a proxy measure of innovation. To test the research hypotheses built around the objectives, we use unique firm-level data obtained from the Australian Bureau of Statistics’ (ABS) Business Longitudinal Analysis Data Environment (BLADE). Both path analysis and instrumental variable (IV) regression modeling allow us to explore the contemporaneous links among all three variables under one econometric framework and to better understand the underlying processes that firms engage in. Regression results reveal evidence for “learning to export” in both the SME and large firm subgroups. However, the “learning by doing/exporting” hypothesis is only significant for large firms. Our empirical assessments also show evidence that R&D and innovation should be regarded as two separate constructs and that R&D is an important input variable for both innovation and for exporting. These findings have important theoretical and practical implications for the export–innovation–R&D literature. Findings from the study can serve as a reliable reference guide for firms that are focused on exports or are seeking to start their export activities. Exporting is regarded a common mode of foreign market entry at relatively low risk, as it commits fewer resources and offers greater flexibility of action (Leonidou & Katsikeas, Citation1996) as well as providing more opportunities to increase sales and profits (Knight et al., Citation2020). It is thus important to gauge which firms are benefiting from exporting and/or investing in R&D and innovation, especially from the resource-constrained SME’s perspective (Love & Roper, Citation2015).

The remainder of this paper is organized into five main sections. The “Theory and hypotheses development” section provides an explanation of the theories underpinning this research, a review of related literature for the hypotheses. The section on “Data and empirical models” presents the data and empirical strategy used in the study, followed by a separate “Empirical results” part. The “Discussion” provides a summary, contributions, and inferences of the results, followed by the “Conclusion.”

Theory and hypotheses development

Theory

The R&D–innovation–export nexus has been discussed in the extant literature under different theoretical frameworks such as “neotechnology” theories of trade (Keesing, Citation1967; Posner, Citation1961; Vernon, Citation1966), neo-endowment (e.g., Ruffin, Citation1988), the resource-based view (RBV) of the firm, and endogenous growth theory. Each of these theoretical frameworks provides a unique perspective on the relationship among R&D, innovation, and export performance.

The “neotechnology” theories of trade, which were initially derived from Leontief’s paradox and Vernon’s product life cycle model (Leontief, Citation1954; Vernon, Citation1966), emphasize the role of innovation, economies of scale, and product differentiation in trade patterns. In the context of the R&D–innovation–export nexus, “neotechnology” theories highlight that innovation is a crucial driver of competitiveness in international markets. R&D activities lead to the development of innovative products or processes that can give firms a comparative advantage (Franko, Citation1989). This advantage arises from the unique and differentiated products resulting from R&D efforts. Hence, firms with unique products can charge premium prices and still attract customers due to the differentiated nature of their offerings. Hence, R&D-driven innovation enhances a firm’s export performance by enabling it to compete effectively and capture a niche in foreign markets.

The “neo-endowment” theory recognizes that both technology and human capital are valuable resources in trade. R&D activities lead to the creation of advanced technologies and skilled human capital, which enhance a nation’s comparative advantage. Firms with higher technological capabilities (achieved through R&D and innovation) have a competitive edge in producing sophisticated and high-value goods. They are likely to specialize in these goods and export them to other countries. Thus, R&D-driven innovation contributes to higher export performance by enabling firms to exploit their comparative advantage in advanced technology and skills.

The RBV focuses on a firm’s unique resources and capabilities as sources of competitive advantage. In the context of the R&D–innovation–export nexus, RBV emphasizes that innovation is a strategic resource that can lead to sustained competitive advantage (Barney, Citation1991; Penrose, Citation1960; Wernerfelt, Citation1984). R&D activities result in the acquisition of knowledge, technologies, and capabilities that are rare, valuable, and difficult to imitate (Barney, Citation1991). Hence, firms that invest in R&D and innovation develop distinctive products, processes, or capabilities that set them apart in global markets. These unique attributes can drive export success by attracting customers seeking differentiated offerings (Amadieu et al., Citation2013; Delgado-Gómez et al., Citation2004). Additionally, the dynamic capabilities developed through innovation enable firms to adapt to changing export market conditions effectively (Zou et al., Citation2003).

Meanwhile, endogenous growth models highlight the role of internal factors, including innovation and human capital, in driving long-term economic growth (Grossman & Helpman, Citation1991). Unlike earlier growth theories that primarily focused on factors like labor and capital accumulation, endogenous growth theory emphasizes the role of technological progress, innovation, and knowledge creation as endogenous (internal) sources of growth. In the context of the R&D–innovation–export nexus, endogenous growth theory is relevant because it emphasizes that innovation is a primary driver of long-term economic growth. While investments in R&D lead to technological progress, enhanced productivity, and increased competitiveness, firms that engage in R&D and innovation are better equipped to succeed in export markets. As innovative firms expand their technological capabilities, they can offer high-quality products or services that meet international customer demands and contribute to improved export performance.

Endogenous growth theory emphasizes the importance of “learning by doing,” which means that knowledge and innovation can be generated through the production process itself (Golovko & Valentini, Citation2011; Grossman & Helpman, Citation1991; Wagner, Citation2007). In other words, firms can learn through experience by constantly experimenting, innovating, and improving their production processes. The more a firm produces a particular good, the more it learns about the production process, leading to improvements in efficiency and productivity. This increased productivity can, in turn, lead to higher levels of economic growth. The concept of learning by doing is also closely related to the idea of technological spillovers and knowledge diffusion. So, as innovation and exports are subject to an endogenous system, exporting firms have prospects of learning by doing as they potentially expose themselves to advanced foreign knowledge and technology that might potentially enable them to improve their productivity and export performance (Golovko & Valentini, Citation2011; Grossman & Helpman, Citation1991; Wagner, Citation2007).

In summary, each of these theoretical frameworks provides a unique perspective on the relationship among R&D, innovation, and export performance. We now turn to further explaining our research objectives in the hypothesis development section below. We derive the “learning to export” and “learning by exporting” hypotheses in the context of the R&D–innovation–export nexus.

Hypotheses development

Learning to export

While the abovementioned theories differ in their emphasis and approach, they collectively highlight the significance of R&D and innovation in enhancing a firm’s competitive advantage and export capabilities in the global marketplace. Following our “learning to export” objective, the extant literature views both R&D activities and innovation as valuable intangible resources that create a culture of innovation and learning that can drive firms to export (e.g., Becker & Egger, Citation2013; Gourlay et al., Citation2005; Roper & Love, Citation2002). By investing in R&D and continually learning and adapting to the evolving demands of both local competition and international trade, businesses can enhance their competitiveness in global markets. Hence, numerous studies find that innovation either increases the likelihood of exports and/or improves export performance (e.g., Dai et al., Citation2020; Dohse & Niebuhr, Citation2018; Hagsten & Kotnik, Citation2017; Lewandowska et al., Citation2016), while studies such as Carboni and Medda (Citation2018), Czarnitzki and Wastyn (Citation2010), Gourlay et al. (Citation2005), and Máñez et al. (Citation2015) find a significant and positive association between R&D and exporting.

According to the neotechnological theory of trade, innovation can lead to the development of unique and advanced products that are in demand globally. Firms that innovate and create such unique products can establish themselves as leaders in their respective industries and gain a competitive edge in international markets. This technological advantage enhances their export performance, as they can offer products that cater to the needs of foreign customers who value innovation and advanced features (Ayllón & Radicic, Citation2019; Tavassoli, Citation2018; Wakelin, Citation1998). Similarly, R&D activities can lead to the development of cutting-edge products, processes, and technologies; hence, firms that invest in R&D are more likely to generate unique innovations that give them a competitive advantage in international markets. These innovations can lead to the creation of high-value products that are in demand globally, enabling firms to excel in exporting and catering to markets that value technological advancements (e.g., Gourlay et al., Citation2005).

In the context of export performance and competitiveness, the RBV suggests that firms with strong innovation capabilities possess valuable resources that can be translated into unique products and services, while R&D investments that can translate into unique skills and capabilities contribute to a firm’s ability to develop new and innovative products or improve existing ones. Accordingly, firms with a strong innovation orientation and R&D investments possess unique and non-imitable resources and are more likely to be positively and significantly associated with export performance.

Meanwhile, endogenous growth theory supports the idea that innovation is a key driver of a firm’s expansion and success, while R&D contributes to a firm’s ability to innovate and develop advanced products. Firms that prioritize innovation and engage in R&D are likely to have a competitive advantage in terms of the quality, features, and technological advancements of their products. This advantage can translate into better export performance, as international customers are attracted to products that offer cutting-edge solutions and meet their evolving needs. Moreover, the knowledge generated through R&D efforts can lead to unique innovations that elevate the firm’s export performance. In this context, R&D is a mechanism through which firms actively shape their growth and export success.

In summary, these theories all contribute to the expectation that innovation and R&D activities will have a positive and significant impact on a firm’s export performance. These theories collectively highlight how innovation and R&D activities not only enhance a firm’s “learning to export” capabilities but also enable the development of innovative products and technologies, enhancing a firm’s competitive advantage and contributing to its ability to meet the demands of international markets that value technological advancements. As a result, firms that focus on innovation and R&D activities are more likely to experience success in exporting due to their unique skills and capabilities and ability to meet the demands of international customers seeking advanced and differentiated offerings. Given the above discussion of the extant literature which views both innovation and R&D activities as valuable intangible resources that create a “learning to export” culture, we derive the following two hypotheses for testing:

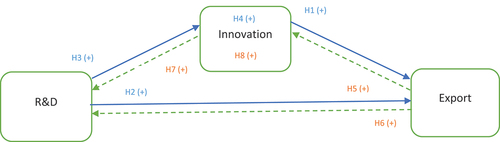

H1:

Innovation is positively and significantly associated with export performance.

H2:

R&D activities are positively and significantly associated with export performance.

Over the past two decades, the extant literature is limited in its consideration of construct validity issues between R&D activities as an input measure and innovation as an output measure (Lachenmaier & Wößmann, Citation2006). Despite theory and practice showing that R&D activities should be considered an input measure and innovation an output measure, initial studies of R&D/innovation and exports (e.g., Greenhalgh et al., Citation1994; Hirsch & Bijaoui, Citation1985; Smith et al., Citation2002) regarded R&D as a proxy measure of innovation, providing little distinction between R&D and innovation. More recent firm-level studies (e.g., Carboni & Medda, Citation2018; Czarnitzki & Wastyn, Citation2010; Máñez et al., Citation2015) that use R&D as a proxy measure of innovation have found a significant and positive association between R&D and exporting. In a firm-level study employing a direct measure of innovation (measured as firms’ producing at least one new service) among US businesses, Love and Mansury (Citation2009) find that innovation has a strong positive effect on exports. While Tavassoli’s (Citation2018) study of product innovation and export behavior among Swedish firms similarly finds a significant positive causal effect of innovation on both export propensity and export intensity, R&D activity which is treated as an “innovation input” variable does not significantly impact export performance. Consequently, Radicic and Djalilov (Citation2019) argue that the weak associations reported in research studies between innovation and exports are due to incorrect usage of the innovation variable. Hence, they claim that it is important to adequately identify the variables R&D and innovation, as this will provide a better understanding of the effects on exports (Radicic & Djalilov, Citation2019). So, while we consider R&D an important and a separate input variable that directly impacts innovation and exports in H4, we also postulate that R&D activities will have a positive indirect (or mediating) effect on exports via innovation. Accordingly, we derive the following two hypotheses for testing using path analysis:

H3:

R&D activities are positively and significantly associated with innovation.

H4:

The positive and significant association between R&D and export performance is indirectly and significantly influenced (mediated) by innovation outcomes.

Learning by exporting

Following Grossman and Helpman’s (Citation1994) endogenous growth framework, the firm heterogeneity literature has led to a better understanding of trade-led innovations (Aghion et al., Citation2022; Damijan et al., Citation2010; Van Beveren & Vandenbussche, Citation2010). For example, in a study of trade agreements and how exports affect the technology/innovation choices of Argentinian firms, Bustos (Citation2011) found that declining tariffs had increased Argentinian firm export revenues and made adoption of new technologies profitable for Argentinian exporters. In a more recent example, Aghion et al. (Citation2022) disentangle the direction of causality between innovation and demand conditions by using firm-level data on a sample of French exporters. They determine that exogenous export demand shocks have a positive effect on the market share and the innovation incentives of French manufacturing firms. A study by Aghion et al. (Citation2022) demonstrates that productive firms respond to these demand shocks by innovating more (as measured by number of patents), leading to these productive firms further increasing their market share and market concentration in their industry. Meanwhile, Smallbone et al. (Citation2022) find that international trade plays a positive role in influencing innovation. While examining the “learning by exporting” hypothesis among Sub-Saharan African, European, and Central Asian economies, Smallbone et al. (Citation2022) found that R&D not only enhanced international trade but also led efficiency improvements in the European and Central Asian economies. Therefore, given the existing literature and the theoretical background of trade-led growth, it is pertinent to analyze the effect of exports on innovation and R&D activities. We derive the following two hypotheses:

H5:

Export performance is positively and significantly associated with innovation.

H6:

Export performance is positively and significantly associated with R&D activities.

While a considerable literature examines the relationship between R&D/innovation and exports, the research literature is limited in its consideration of problems of reverse causality and endogeneity between R&D/innovation and exports (e.g., Veugelers & Cassiman, Citation1999). Indeed, a wide range of firm-level studies on export behavior considers implicitly that causality runs one way from innovation to exports, finding evidence that such a causal specification shows a positive relationship between innovation and exports (Bleaney & Wakelin, Citation2002; Harris & Li, Citation2008, Citation2011; Love et al., Citation2016). However, a small but growing literature is emerging, such as Esteve-Pérez and Rodríguez (Citation2013), who use Spanish manufacturing firm data to consider reverse causality between R&D and exports for SMEs, while Palangkaraya (Citation2012) investigates the direction of causality between innovation and exports using Australian firm-level data. Palangkaraya’s (Citation2012) results indicate that the direction of causality is dependent on the type of innovation taken in the firm, whether it is product or process innovation. In addition, Harris and Li (Citation2008) examine the effects of R&D on innovation and export performance using firm-level manufacturing data from the UK. They account for possible joint causality of exports and R&D by incorporating a two-stage Heckman approach combined with IV-regression estimation. Harris and Li (Citation2008) find that while the endogenous variable R&D assists firms in overcoming barriers to internationalization, it does not increase export intensity when joint causality of exports and R&D is considered.

In summary, while the extant literature has investigated the impact of exports on R&D, the issue of identifying innovation and R&D as separate output and input measures respectively still remains. Furthermore, as the literature is limited in its consideration of reverse causality and endogeneity, and only a few studies such as Harris and Moffat (Citation2011) focus on examining the contemporaneous relationship among exports, R&D, and innovation, we derive two hypotheses analogous to H3 and H4 to test both reverse causality and the mediating effect of innovation on R&D using path analysis:

H7:

Innovation is positively and significantly associated with R&D activities.

H8:

The positive and significant association between export performance and R&D is indirectly and significantly influenced (mediated) by innovation outcomes.

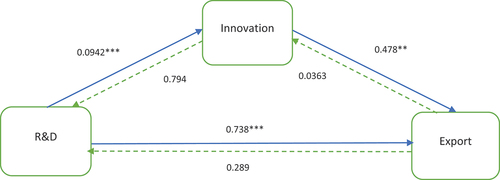

illustrates the path analysis examining the direct relationship between R&D activities and exporting and between innovation and exporting and the possible mediating effect of R&D through innovation as well as the feedback effect from exports.

Data and empirical models

Data and descriptive analysis

To test our hypotheses, we utilize several datasets made available to the researchers through the ABS’s BLADE. The BLADE datasets contain anonymized firm-level longitudinal data from tax filings, business registrations, customs and excise, intellectual property data on patents, trademarks and designs, and various ABS surveys between the financial years 2001–02 and 2018–19. Financial data are derived from the Australian Tax Office’s (ATO) Business Income Tax (BIT), and where BIT data are missing, we supplement these with data obtained from the ATO’s Business Activity Statement (BAS) and from the ABS’s Economic Activity Survey (EAS). Data on exports come from the Merchandise on Exports Dataset, whereas data on innovation and R&D come from the ABS’s survey of Business Expenditure on R&D (BERD) and is supplemented by additional BIT data and by the ABS’s Business Characteristics Survey (BCS) dataset. With respect to the key variables used in this study, namely, exports, R&D, and innovation, BLADE provides data on total sales of goods and/or services generated outside Australia (i.e., from exports); total R&D expenditures by firms; and whether a firm has introduced a significantly new or improved goods or service, operational process, organizational/managerial process, or marketing method.

As data in BLADE mainly represent businesses with a company legal structure, the sample is restricted to registered private companies. We further restrict the sample to fiscal years after 2005–06, as prior to that year it is not possible to separate “real” zero values from zero values that are assigned as missing data for some variables. In line with the ABS’s definitions of firm size, that is, micro-businesses as fewer than 5 employees, small businesses as 5–19 employees, medium-sized businesses as 20–199 employees, and large businesses as 200+ employees, we restrict our regression modeling to provide separate estimates for companies that are SMEs (i.e., have fewer than 200 employees) and large companies (i.e., have 200+ employees). Our final total sample comprises 17,335 firm-year observations, which correspond to 3,360 (19%) SME observations and 13,975 (81%) large private company observations over a period of 13 consecutive years. provides descriptive statistics for the two size groups that our regression model estimates are based upon, that is, SMEs (Panel A) and large private companies (Panel B). Focusing on the main variables of interest in this paper and in line with the ABS firm size definitions reported earlier, approximately 40.7% of SMEs in our sample export, 22.2% are R&D active, and 57.4% innovate. In contrast, approximately 61.1% of large private companies’ export, 29.5% are R&D active, and 67.5% innovate. A further examination of exports and firm size show that the annual export sales for SMEs (i.e., fewer than 200 employees) was on average $5.75 million between the fiscal years 2005–06 and 2018–19, while the annual export sales for large private companies (i.e., 200+ employees) was on average $79 million over the same period (see ). Meanwhile, annual R&D expenditures for SMEs was on average approximately $0.66 million and for large private companies around $4.3 million, whereas on average 55.3% of SMEs and 65% of large companies introduced an innovation annually between the fiscal years 2005–06 and 2018–19 (see ).

Figure 2. Average annual export sales by large firms and SMEs between 2005–06 and 2018–19.

Figure 3. Average annual R&D expenditure by large firms and SMEs between 2005–06 and 2018–19.

Figure 4. Average annual innovations introduced by large firms and SMEs between 2005–06 and 2018–19.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

In our sample of private companies, SMEs have on average 49.29 employees, annual turnover in sales of $56 million, annual asset value of $10.1 million, and foreign ownership of 25.06% and are approximately 26 years. In contrast, larger companies have on average 1,977 employees, annual turnover in sales of $1.71 billion, asset value of $2.5 billion, and foreign ownership of 45.47% and are more than 45 years old.

Model specifications and empirical model

Three separate dependent variables are modeled and given the potential endogenous nature of the relationships among these variables; simultaneity is considered. In addition, we emphasize the role of R&D as a separate input (determinant) of exports and innovation. Thus, as illustrated in , we employ path analysis, which examines the direct relationship between R&D activities and exporting and between innovation and exporting as well as the possible mediating effect of R&D through innovation and possible feedback effects from exports. We build on the path analysis of Crepon et al. (Citation1998) and Harris and Moffat’s (Citation2011) simultaneous equation modeling techniques. Hence, the structural equations are represented as follows:

where R&D is the total research and development expenditure in firm i at time t; Innovation is whether firm i at time t has introduced a product and/or process innovation represented by an indicator value 1 and 0 otherwise; and Exports is measured by the total export sales of firm i at time t. ,

and

are the control variables for each equation, respectively. For the simultaneous equation model, we assume that in each Equationequation 1

(1)

(1) , Equation2

(2)

(2) , and Equation3

(3)

(3) , respectively, there are some variables in

,

, and

that are exclusive to each other meaning

∉

∉

. So there exist variables:

,

, and

from

,

, and

that are mutually exclusive; thus, these variables can be used as instruments in a single equation approach. Instruments are valid if they are shown to strongly determine the proposed endogenous variable but show no direct effect on the outcome/dependent variable of the model.

While a common approach is to use lagged values of (potentially) endogenous variables and estimate these values via a generalized method of moments (GMM) estimator to overcome endogeneity problems such as nonlinear functional relationships and heteroskedasticity and autocorrelation within individual observations, we refrain from using a dynamic panel estimator. This is because our panel dataset comprises a large cross-section of firms, a considerable difference in the sample size of SME and large firms, and a relatively small number of years. Accordingly, as the GMM estimator has poor small sample properties, which is sensitive to model misspecification, and it is reliant on model parameters to be identified to obtain consistent estimates (see Roodman, Citation2009), we are unable to use GMM. More importantly, lagged variables do not necessarily overcome simultaneity problems, particularly when firms have prior knowledge of their exporting, R&D, and innovation prospects. That is, firms are likely to make current decisions based on their exporting, R&D, and innovation prospects with the potential of undertaking complementary activities (Harris & Moffat, Citation2011). Hence, our regression modeling strategy includes use of two-stage instrumental variable estimates treating exports, R&D, and innovation as endogenous. When treating the variables as exogenous, we use ordinary least square (OLS) for the exports and R&D equations and probit estimations for the innovation equation. The modeling specifications for the three models are as follows:

The dependent variables, is the natural logarithm of the firm’s total dollar value of R&D expenditures, Innovation follows the ABS’s definition of innovation, and ln_Exports is measured as the natural logarithm of the firm’s export sales. The ABS defines innovation as the introduction of a new or significantly improved good or service, operational process, organizational/managerial process, or marketing method by a firm. Accordingly, innovation (

) is a composite measure comprising four items gauging whether the firm introduced any new or significantly improved: (1) goods or services; (2) new operational processes; (3) new marketing methods, and (4) new organizational/managerial processes. The variable takes the value of 1 if the firm has introduced innovation in at least one of the areas and 0 otherwise. Although there is no uniform measure for export performance that is utilized in the literature, economic measures such as export sales level, export sales growth, export profits, export intensity, and export propensity have been used extensively as indicators (Cavusgil & Zou, Citation1994; Chen et al., Citation2016). Export propensity is widely used in the literature to measure export behaviors of a firm (e.g., Fernández & Nieto, Citation2006; Gao et al., Citation2010; Krammer et al., Citation2018), but we are more interested in examining the effect of export sales overall, rather than the SME firm’s probability of internationalization. Hence, we use the natural logarithm of export salesFootnote1 (ln_Export_sales) of a firm for the analysis.Footnote2

The R&D equation follows mostly that of Cornet and Vroomen (Citation2005) and Holt et al. (Citation2021). The controls are the natural logarithm of total dollar value of receipts of government subsidies for R&D (ln_R&D support), natural logarithm of company sales revenue (ln_Turnover), company profitability as measured by profits divided by total assets (roa), natural logarithm of the total dollar value of salaries paid by the business (ln_salary) and the natural logarithm of the total dollar value of assets in the company (ln_assets), natural logarithm of the number of staff employed by the business (ln_size), and age of the firm (ln_age) measured by the number of years the business has been in operation.

The Innovation equation is a function of the natural logarithm of R&D expenditures, the natural logarithm of export sales, human capital skills, physical assets, and generic size and age as controls. For human capital skills, we use two composite measures to represent the firm’s technical and business skills as defined by the ABS. The measure representing technical skills, Tech_skill, comprises skills in the following areas: engineering; scientific and research; information technology professionals; information technology support technicians; and transport, plant, and machinery operation. So, the variable is an indicator variable that takes the value of 1 if a firm comprises skills in at least one of the specified areas and 0 zero otherwise. The measure representing business skills, Buss_skill, is also constructed as an indicator variable that takes the value of 1 when a firm comprises skills in at least one of the following areas—trades, marketing, project management, business management, and financial.

In the export equation (EquationEquation (6)(6)

(6) ), we control for the firm’s productivity using the natural logarithm of turnover (ln_turnover) which can affect firms’ export behavior (Love et al., Citation2016). We also control for the surrounding business environment using competition (Competition). The degree of competition is regarded an important external driver of export performance. Increased competition for local resources encourages firms to differentiate (Henderson & Mitchell, Citation1997) and seek opportunities abroad to secure critical resources to ensure business survival and development (Westhead et al., Citation2001). For the competition measure, we calculate the Herfindahl—Hirschman index (HHI) and create a variable of market concentration by taking the sum of the square of market share of each firm in the same industry. The Australian and New Zealand Standard Industrial Classification (ANZSIC) system is used at the four-digit industry division–level to take account of market power and competition in private companies that conduct R&D, innovate, and export. Other controls include degree of foreign ownership (

and financial support. Foreign-owned firms can provide useful access to resources, such as financing and human capital required for export activities (Añón Higón & Driffield, Citation2011; Filatotchev et al., Citation2008) as well as possessing more superior knowledge and experience about foreign markets than their domestic counterparts (Hiep & Ohta, Citation2009). For example, Munkácsi (Citation2009), Okubo et al. (Citation2017), and Filatotchev et al. (Citation2008) report that foreign ownership plays an important role in the export orientation of firms compared to fully locally owned firms. The percentage of foreign ownership obtained from BLADE is used to complement our study, and hence our variable measuring large-block foreign investors is coded in ascending rank order as follows: 0 for 0% ownership; 1 for >0% to <10%; 2 for ≥10% to <50%, and 3 for >50% ownerships. Financial access is an important issue in the context of exports and is often discussed as a key factor in some strands of the export literature. Especially for SMEs, financial access constraints can act as a barrier for firms engaging in exports (Bellone et al., Citation2010). Hence, where there is a possibility of market failure, public support is crucial for potential SME exporters to overcome costs and expand their range of products, services, and markets. As we are unable to use a financial constraint measure fit-for-purpose using the BLADE dataset, we use financial support (financial_support) instead as a proxy measure for financial constraint. This proxy measure is the sum of six different types of financial assistance schemes that are provided by the Australian government: grants, ongoing funding, subsidies, tax concessions, rebates, and other. It is calculated as a count measure with a minimum value of 0 as no financial assistance received and 6 as the maximum number of financial assistances received by the SME firm from various government schemes.

Generic to all three equations, size and age are added as controls in the various specifications. Firm size, measured as the natural logarithm of the number of employees, is acknowledged to be an important contributing firm-specific variable to export performance (e.g., see Serra et al., Citation2012; Sousa et al., Citation2008). Firm age is measured as the number of years since the firm was formed. All estimations include year and industry fixed effects with clustered id. A list of variable definitions and source is provided in Appendix A in .

Empirical results

Results for SME cohort

Results for the regression equations are presented in , which report R&D, innovation, and exports as exogenous variables in columns (1), (3), and (5) and as endogenous variables in columns (2), (4), and (6). To identify whether simultaneity exists among the variables, there should be a substantial difference in the parameter estimates between the OLS or probit and the IV estimates. In addition, each instrument used in the regression model is associated with two sets of tests of the null hypothesis. For example, the potential endogenous variables Innovation and Ln_Export in the Ln_R&D equation in column (2) are associated with two sets of instruments, one for the export variable and the other for the innovation variable. The same applies to the IV estimations in Equationequations (4)(4)

(4) and (Equation6

(6)

(6) ). The results of the F tests associated with the instruments are reported in under each IV estimation.Footnote3 The first-stage F test assesses whether the instruments are correlated with the endogenous variable. It tests the null hypothesis that the instruments are uncorrelated with the endogenous variable against the alternative hypothesis that at least one of the instruments is correlated with the endogenous variable. The significant F statistics in columns (2), (4), and (6) indicate that the instruments used in our study are valid.

Table 2. Regression results—SME sample.

The parameter estimates in depict results for the SME (i.e., firms with fewer than 200 employees) cohort. The OLS and IV estimates in columns (1) and (2) show there are considerable differences in the b coefficients for innovation and exports in the Ln_R&D equation. The OLS estimates in column (1) show that Ln_Export has a significant and positive effect on Ln_R&D, measured by the total dollar value of the firm’s R&D expenditure. However, after accounting for endogeneity in column (2), the b coefficient for Ln_Export is nonsignificant in the IV estimation model, providing no empirical support to the “learning-by-exporting” hypothesis tested in H6. The IV estimates in column (2) also show that Innovation does not significantly affect Ln_R&D, providing no support to H7. The control variables in columns (1) and (2), Ln_R&D_Support, Ln_Turnover, and ROA, indicate that external R&D support and the firm’s performance indicators as measured by sales turnover and return on assets are important determinants of R&D activity in SME firms.

For the Innovation equation estimates in columns (3) and (4), Ln_R&D plays a significant and positive role in the SME firm’s innovation activities both in the Probit and IV models. But there is considerable difference in the magnitudes of the two coefficients, suggesting that there is some evidence of endogeneity. The IV estimates in column (4) indicate that firms with 1% increase in R&D activities above the sample mean can increase the likelihood of innovation by 9.56% based on the marginal effect,Footnote4 thus providing support for H3. The effect of Ln_Export on Innovation in column (4) is statistically nonsignificant, offering no support to H5 but providing additional evidence that the learning by exporting hypothesis does not apply to this sample of SMEs. The control variables business skills (Buss_skill) and technical skills (Tech-skill) significantly increase the likelihood of innovation by 45.4% and 39.6%, respectively, suggesting that SMEs with well-developed human capital can reap innovation advantages. Furthermore, Ln_Size has a significant and positive impact on Innovation, while Ln_Age and Ln_Fixed_Asset are not significantly associated with Innovation.

The Ln_Export equation estimates reported in columns (5) and (6) show that both Ln_R&D and Innovation have significant and positive effects on Ln_Export, providing further corroborating evidence of the importance of R&D activities (D’Angelo, Citation2012; Gashi et al., Citation2014; Smith et al., Citation2002; Wakelin, Citation2001) and innovation (Becker & Egger, Citation2013; Dai et al., Citation2020; Gkypali & Tsekouras, Citation2015; Love et al., Citation2016; Tavassoli, Citation2018) in SME export performance. More importantly, both R&D and innovation separately affect exports, providing support to H1 and H2, respectively. The significant and positive coefficient effect of Ln_R&D on Ln_Export in column (6) suggests that for a 1% increase in R&D expenditure, export sales increase by 0.74% over the sample mean. The path analysis, which assesses the relative influence of R&D and innovation on exports, reveals that a significant indirect relationship exists between Ln_R&D and Ln_Export via Innovation, providing support to H4. The significant indirect effect of Ln_R&D on Ln_Export via Innovation indicates that a 1% increase in R&D expenditure through innovation stimulates the SME’s level of export sales by 5% (9.56 × 0.478)Footnote5 above the sample mean. This significant indirect relationship suggests that for SMEs to enhance their export performance, they need to undertake R&D activities to further stimulate innovation (Añón Higón & Driffield, Citation2011; Filatotchev et al., Citation2008; Love & Roper, Citation2015). Although the literature empirically examines the importance of R&D for innovation (Carboni & Medda, Citation2018; Gourlay et al., Citation2005; Máñez et al., Citation2015), we provide a contribution to the SME literature by using path analysis to separately assess the important contribution of R&D activities on innovation and exports in SMEs, as well as the meditating effect of innovation on R&D activities and exports. illustrates the direct and indirect effects from our path analysis on SMEs.

Figure 5. Path analysis and contemporaneous relationships among R&D, innovation, and exports for SMEs.

With respect to the control variables in columns (5) and (6) (see ), a significant and positive effect of foreign ownership on Ln_Export suggests that SME firms that are exposed to higher degrees of foreign ownership are associated with higher export sales. This result provides additional supporting evidence reported in the literature that foreign ownership can provide useful access to resources, such as financing and human capital required for export activities (Añón Higón & Driffield, Citation2011; Filatotchev et al., Citation2008), as well as possessing more superior knowledge and experience about foreign markets compared to their domestic counterparts (Hiep & Ohta, Citation2009). Our measure of market concentration based on the HHI shows a significant and positive effect on Ln_Export, providing support to the extant literature (e.g., Jin & Cho, Citation2018; Sousa et al., Citation2008) that competition has an influence on SMEs’ export behavior and is an important external driver of export performance. Increased competition for local resources encourages firms to differentiate (Henderson & Mitchell, Citation1997) and seek opportunities abroad to secure critical resources to ensure business survival and development (Westhead et al., Citation2001). In addition, Financial_support is significantly and positively associated with Ln_Export, indicating that external financial support is important for encouraging export sales among resource-constrained SMEs.

Results for large firm cohort

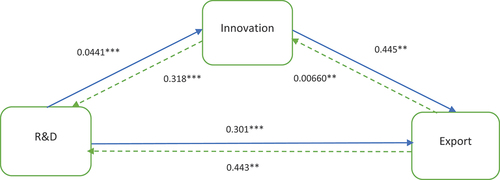

To provide a better understanding of the differences in R&D activities and innovation in relation to export performance between SME and large firms, we now turn to examining the simultaneous relationships among these three variables for large companies. Results for the regression equations on the large firm cohort are presented in . While the results reported for large firms are qualitatively similar to those presented for SMEs in , there are some notable exceptions. For example, the IV regression results in show that both Ln_Export and Innovation have significant and positive effects on Ln_R&D (see column 2). Conversely, Ln_R&D has a significant and positive effect on both Innovation (see column 4) and Ln_Export (see column 6). The b coefficient results in columns (2), (4), and (6) indicate that these variables are subject to significant reverse causality in the large firm cohort. In contrast, Ln_Export is not a determinant of R&D expenditure and Innovation in the SME cohort. The results reported in suggest that large firms—at least in our sample—exhibit the learning-by-exporting effect posited by H5 to H8 hypotheses. Our results also provide additional supporting evidence for Grossman and Helpman’s (Citation1994) endogenous trade-led growth theory and follows similar results reported in Damijan et al. (Citation2010), Bustos (Citation2011), and Aghion et al. (Citation2022).

Table 3. Regression results: large company sample.

The path analysis conducted on the large firm cohort displays two separate mediating effects via Innovation (see ). The first significant mediating or indirect effect is between Ln_R&D and Ln_Export through Innovation. A 1% increase in R&D expenditure in large firms increases the level of export sales through innovation by 2% (4.3 × 0.445)Footnote6 above the sample mean. The second significant mediating or indirect effect is between Ln_Export and Ln_R&D through Innovation. This reverse feedback effect in large firms running from exports to R&D via innovation suggests that a 1% increase in export sales stimulates the level of R&D expenditures in large firms via innovation by 0.2% (0.629 × 0.318)Footnote7 above the sample mean. illustrates the direct and indirect effects from our path analysis on the large company cohort. The results based on the estimations for both SMEs and large firms are summarized in .

Figure 6. Path analysis and contemporaneous relationships among R&D, innovation, and exports for large firms.

Table 4. Summary of hypotheses and results.

Robustness checks

To check the robustness of our results, we conduct additional analyses by rerunning the regression estimations on a differing SME size definition and on alternate measures of export. As the ATO uses aggregated sales turnover to differentiate between small and large companies claiming R&D tax incentives (R&DTI), a company whose aggregated turnover is less than AUD $20 million is defined a small business. Accordingly, we create an indicator variable size_large, where 1 designates companies that have aggregated turnover equal to or greater than AUD $20 million and 0 otherwise. After segregating our initial sample into small and large firms based on the aggregated turnover definition, the estimates for the small and large firms remain robust to the initial regressions, providing further internal validity to our initial results (see ).Footnote8

Table 5. Regression results of SMEs based on turnover.

Table 6. Regression results of large companies based on turnover.

Discussion

Summary and contributions

We examine the simultaneous relationship among R&D, innovation, and exports by assessing “learn to export” and “learning by exporting” hypotheses to provide new insights into the nexus. Using separate measures of R&D and innovation, we also provide evidence of mediating or indirect effects between Ln_R&D and Ln_Export via Innovation and between Ln_Export and Ln_R&D via Innovation. Despite the plethora of literature studying R&D, innovation, and exports, the literature is limited in uniquely defining R&D and innovation as separate determinants of exports, especially in the context of differing firm sizes. Empirical results in the literature suggest evidence of “learning to export” for SMEs (see Eliasson et al., Citation2012), where R&D and innovation are both important for exporting (e.g., DiCintio et al., Citation2017; Falk & de Lemos, Citation2019; Gashi et al., Citation2014). We similarly show that export performance is enhanced when SMEs undertake in-house R&D activities and innovation, but it appears that exports do not influence the SME’s R&D activities and innovation outcomes in our Australian sample.

While the literature emphasizes the importance of R&D for innovation and the direct effect of innovation on exporting (Paul et al., Citation2017; Saridakis et al., Citation2019), it rarely considers the mediating role of innovation and the indirect effect of R&D for exports. We provide a contribution to the literature by showing evidence of significant mediating (indirect) effects between Ln_R&D and Ln_Export via Innovation in both the SME and large firm cohorts, which is consistent with results reported in Damijan et al. (Citation2010) and Aghion et al. (Citation2022). However, evidence of significant mediating (indirect) effects between Ln_Export and Ln_R&D via Innovation is only observed in large firms, providing no support for simultaneity and the “learning by exporting” hypothesis in SMEs as reported in the literature (e.g., Esteve-Pérez & Rodríguez, Citation2013; Gkypali & Tsekouras, Citation2015; Golovko & Valentini, Citation2011; Smallbone et al., Citation2022). Accordingly, we provide an important theoretical contribution to the SME literature by linking export, innovation, and R&D activities in a unique path analysis.

Implications

This study also serves as a reliable reference guide to firms that are focused on exports or are seeking to start their export activities and, thus, our findings have important policy implications for Australian firms and firms in general. With R&D being an important determinant for exports, government assistance programs aimed at stimulating export performance of firms should be more discerning and provide more targeted financial and in-kind support to those firms that show an ability to conduct R&D and have a track record of innovation as such firms can improve their export performance. With respect to SMEs, as small businesses on average experience significant financial constraints, external support to assist small businesses to innovate is essential as investing in knowledge-creation assets can be costly. Policymakers, business practitioners, and SME owner-managers should therefore strive to develop mechanisms and/or provide external resources to potentially facilitate R&D expenditure and innovation. Such activities will not only enhance the firm’s export performance and productivity but also will increase the economic value of the firm.

Grossman and Helpman (Citation1991) argue that due to the prospect of learning by doing, exporting firms can potentially expose themselves to advanced foreign knowledge and technology that can enable firms to improve their productivity and innovation. In turn, this becomes a dynamic virtuous circle in which R&D, innovation, and export performance mutually reinforce each other (Golovko & Valentini, Citation2011; Muñoz et al., Citation2022). One possible explanation for observing these differences between SMEs and large firms in our study could be due to the prerequisites for the export-innovation and/or R&D pathways. The relative strengths of large firms are predominantly material such as economies of scale and scope, financial and technological resources, and absorptive capabilities, whereas SMEs experience greater resource constraints in these areas (Catanzaro et al., Citation2019; DiCintio et al., Citation2017; Lee et al., Citation2012; Pickernell et al., Citation2016; St-Pierre et al., Citation2018). As large firms have these resource advantages and capabilities, they are better able to harness greater benefits from export enhanced R&D and innovation. Further support for this argument can be found in the nonsignificant relationship between Financial_support and Ln_Export in large companies (see , column (6)) compared to the significant and positive relationship between Financial_support and Ln_Export for SMEs (see , column (6)), suggesting that external financial support is an important determinant of export sales in resource constrained SMEs but not in large firms.

Limitations and directions for future research

The study is subject to some limitations. First, the study’s data end in 2018. Due to the unavailability of updated datasets, it could not be extended to the most recent years. Second, we only use survey-based innovation measures. We could have included patent data, but this would have reduced our sample and statistical power of our tests considerably. Third, our empirical analyses lack data on managerial background. Previous studies have suggested the importance of managerial and entrepreneurial skills and how their experience and diversity influence firms’ export strategies and success. Proxy measure for managerial ability could have been derived using Demerjian et al. (Citation2012); however, it reduces the sample size by a considerable amount, especially for SMEs, which could have potentially affected the reliability of the results. Future research should consider focusing on managerial background; exploring why SMEs are unable to learn from internationalization, unlike their larger counterpart; and further analyzing the dynamic effects of the R&D–innovation–exports nexus.

Conclusion

This study empirically investigates the “learning to export” and “learning by exporting/doing” hypotheses and the simultaneity among R&D, innovation, and exporting in Australian SMEs and large firms. Using R&D as a separate input measure of innovation and exports rather than merely a proxy measure of innovation, we examine both the direct and the mediating (via innovation) relationships between R&D and exporting as well as the possible feedback effects from exports to R&D and innovation. By investigating this within a unique econometric framework with path analyses, this paper provides novel empirical insights into the contemporaneous relationships among R&D, innovation, and exports. Results show that R&D and innovation should not be regarded as identical constructs but rather be viewed as two separate variables. When accounting for endogeneity, R&D affects exports (via innovation) directly and indirectly in both SMEs and large firms, providing evidence for the “learning to export” hypothesis. However, the effect of export on innovation and on R&D is only statistically significant in large firms. Our study demonstrates that exports increase significantly when SME firms are incentivized to innovate through R&D expenditure. This calls for establishment of more targeted policies that specifically identify firms that undertake R&D and innovation activities to enhance exporting.

Acknowlegments

The authors appreciate the constructive comments and suggestions provided during the evaluation process. They thank the anonymous reviewers and the assistant editor for their helpful comments.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Notes

1 To avoid losing data on zero export sales, the variable is constructed as log (export_sales +1).

2 While export intensity is commonly used in literature to gauge export performance, we refrain from using such a measure as it requires including a Tobit estimation.

3 We also estimated the reduced-form models, which help to identify the instruments for each endogenous variable. Results are available upon request.

4 Marginal effects are calculated post estimation in the Probit models.

5 The marginal effect value 9.56 is calculated post estimation in the Probit models.

6 The marginal effect value 4.3 is calculated post estimation in the Probit models.

7 The marginal effect value 0.629 is calculated post estimation in the Probit models.

8 We also utilize other export measure such as likelihood of exporting (export propensity) to check the robustness of our baseline results.

References

- Aghion, P., Bergeaud, A., Lequien, M., & Melitz, M. J. (2022). The heterogeneous impact of market size on innovation: Evidence from French firm-level exports. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 1–56. https://doi.org/10.1162/rest_a_01199

- Amadieu, P., Maurel, C., & Viviani, J. L. (2013). Intangibles, export intensity, and company performance in the French wine industry. Journal of Wine Economics, 8(2), 198–224. https://doi.org/10.1017/jwe.2013.27

- Añón Higón, D., & Driffield, N. (2011). Exporting and innovation performance: Analysis of the annual small business survey in the UK. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 29(1), 4–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610369742

- Ayllón, S., & Radicic, D. (2019). Product innovation, process innovation and export propensity: Persistence, complementarities and feedback effects in Spanish firms. Applied Economics, 51(33), 3650–3664. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2019.1584376

- Barney, J. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

- Becker, S. O., & Egger, P. H. (2013). Endogenous product versus process innovation and a firm’s propensity to export. Empirical Economics, 44(1), 329–354. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00181-009-0322-6

- Bellone, F., Musso, P., Nesta, L., & Schiavo, S. (2010). Financial constraints and firm export behaviour. The World Economy, 33(3), 347–373. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01259.x

- Bleaney, M., & Wakelin, K. (2002). Efficiency, innovation and exports. Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics, 64(1), 3–15. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0084.00001

- Bustos, P. (2011). Trade liberalization, exports, and technology upgrading: Evidence on the impact of MERCOSUR on Argentinian firms. American Economic Review, 101(1), 304–340. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.1.304

- Carboni, O. A., & Medda, G. (2018). R&D, export and investment decision: Evidence from European firms. Applied Economics, 50(2), 187–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036846.2017.1332747

- Catanzaro, A., Messeghem, K., & Sammut, S. (2019). Effectiveness of export support programs: Impact on the relational capital and international performance of early internationalizing small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(sup2), 436–461. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12489

- Cavusgil, S. T., & Zou, S. (1994). Marketing strategy-performance relationship: An investigation of the empirical link in export market ventures. Journal of Marketing, 58(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224299405800101

- Chang, F. Y. M., & Webster, C. M. (2019). Influence of innovativeness, environmental competitiveness and government, industry and professional networks on SME export likelihood. Journal of Small Business Management, 57(4), 1304–1327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12446

- Chen, J., Sousa, C. M., & He, X. (2016). The determinants of export performance: A review of the literature 2006–2014. International Marketing Review, 33(5), 626–670. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMR-10-2015-0212

- Cornet, M., & Vroomen, B. (2005). Hoe effectief is extra fiscale stimulering van speur- en ontwikkelingswerk? Effectmeting op basis van de natuurlijk-experimentmethode. Centraal Planbureau.

- Crepon, B., Duguet, E., & Mairessec, J. (1998). Research, innovation and productivi[Ty: An econometric analysis at the firm level. Economics of Innovation & New Technology, 7(2), 115–158. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599800000031

- Czarnitzki, D., & Wastyn, A. (2010). Competing internationally: On the importance of R&D for export activity (ZEW Discussion Papers No. 10–071). ZEW - Leibniz Centre for European Economic Research. https://ideas.repec.org/p/zbw/zewdip/10071.html

- D’Angelo, A. (2012). Innovation and export performance: A study of Italian high-tech SMEs. Journal of Management & Governance, 16(3), 393–423. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-010-9157-y

- Dai, M., Liu, H., & Lin, L. (2020). How innovation impacts firms’ export survival: Does export mode matter? The World Economy, 43(1), 81–113. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12847

- Dai, M., & Yu, M. (2013). Firm R&D, absorptive capacity and learning by exporting: Firm‐level evidence from China. The World Economy, 36(9), 1131–1145. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12014

- Damijan, J. P., Kostevc, Č., & Polanec, S. (2010). From innovation to exporting or vice versa? The World Economy, 33(3), 374–398. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2010.01260.x

- Delgado-Gómez, J. M., Ramı́rez-Alesón, M., & Espitia-Escuer, M. A. (2004). Intangible resources as a key factor in the internationalisation of Spanish firms. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 53(4), 477–494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jebo.2002.11.001

- Demerjian, P., Lev, B., & McVay, S. (2012). Quantifying managerial ability: A new measure and validity tests. Management Science, 58(7), 1229–1248. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1110.1487

- DiCintio, M., Ghosh, S., & Grassi, E. (2017). Firm growth, R&D expenditures and exports: An empirical analysis of italian SMEs. Research Policy, 46(4), 836–852. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2017.02.006

- Dohse, D., & Niebuhr, A. (2018). How different kinds of innovation affect exporting. Economics Letters, 163, 182–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econlet.2017.12.017

- Eliasson, K., Hansson, P., & Lindvert, M. (2012). Do firms learn by exporting or learn to export? Evidence from small and medium-sized enterprises. Small Business Economics, 39(2), 453–472. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-010-9314-3

- Esteve-Pérez, S., & Rodríguez, D. (2013). The dynamics of exports and R&D in SMEs. Small Business Economics, 41(1), 219–240. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-012-9421-4

- Falk, M., & de Lemos, F. F. (2019). Complementarity of R&D and productivity in SME export behavior. Journal of Business Research, 96(C), 157–168. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.018

- Fernández, Z., & Nieto, M. J. (2006). Impact of ownership on the international involvement of SMEs. Journal of International Business Studies, 37(3), 340–351. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400196

- Filatotchev, I., Stephan, J., & Jindra, B. (2008). Ownership structure, strategic controls and export intensity of foreign-invested firms in transition economies. Journal of International Business Studies, 39(7), 1133–1148. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8400404

- Franko, L. G. (1989). Global corporate competition: Who’s winning, who’s losing, and the R&D factor as one reason why. Strategic Management Journal, 10(5), 449–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250100505

- Ganotakis, P., & Love, J. H. (2011). R&D, product innovation, and exporting: Evidence from UK new technology based firms. Oxford Economic Papers, 63(2), 279–306. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpq027

- Gao, G. Y., Murray, J. Y., Kotabe, M., & Lu, J. (2010). A “strategy tripod” perspective on export behaviors: Evidence from domestic and foreign firms based in an emerging economy. Journal of International Business Studies, 41(3), 377–396. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2009.27

- Gashi, P., Hashi, I., & Pugh, G. (2014). Export behaviour of SMEs in transition countries. Small Business Economics, 42(2), 407–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-013-9487-7

- Gkypali, A., & Tsekouras, K. (2015). Productive performance based on R&D activities of low-tech firms: An antecedent of the decision to export? Economics of Innovation & New Technology, 24(8), 801–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/10438599.2015.1006041

- Golovko, E., & Valentini, G. (2011). Exploring the complementarity between innovation and export for SMEs’ growth. Journal of International Business Studies, 42(3), 362–380. https://doi.org/10.1057/jibs.2011.2

- Gourlay, A., Seaton, J., & Suppakitjarak, J. (2005). The determinants of export behaviour in UK service firms. The Service Industries Journal, 25(7), 879–889. https://doi.org/10.1080/02642060500134154

- Greenhalgh, C., Taylor, P., & Wilson, R. (1994). Innovation and export volumes and prices—A disaggregated study. Oxford Economic Papers, 46(1), 102–135. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a042115

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1991). Trade, knowledge spillovers, and growth. European Economic Review, 35(2–3), 517–526. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-2921(91)90153-A

- Grossman, G. M., & Helpman, E. (1994). Endogenous innovation in the theory of growth. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 8(1), 23–44. https://doi.org/10.1257/jep.8.1.23

- Hagsten, E., & Kotnik, P. (2017). ICT as facilitator of internationalisation in small- and medium-sized firms. Small Business Economics, 48(2), 431–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-016-9781-2

- Harris, R., & Li, Q. C. (2008). Exporting, R&D, and absorptive capacity in UK establishments. Oxford Economic Papers, 61(1), 74–103. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpn011

- Harris, R., & Li, Q. C. (2011). Participation in export markets and the role of R&D: Establishment-level evidence from the UK community innovation survey 2005. Applied Economics, 43(23), 3007–3020. https://doi.org/10.1080/00036840903427190

- Harris, R., & Moffat, J. (2011). R&D, innovation and exporting (SERC Discussion Papers No. 0073). Centre for Economic Performance, LSE. https://ideas.repec.org/p/cep/sercdp/0073.html

- Henderson, R., & Mitchell, W. (1997). The interactions of organizational and competitive influences on strategy and performance: Organizational and competitive interactions. Strategic Management Journal, 18(S1), 5–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199707)18:1+<5:AID-SMJ930>3.0.CO;2-I

- Hiep, N., & Ohta, H. (2009). Superiority of exporters and the causality between exporting and firm characteristics in Vietnam (Discussion Paper Series No. 239). Research Institute for Economics & Business Administration, Kobe University. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:kob:dpaper:239

- Hirsch, S., & Bijaoui, I. (1985). R&D intensity and export performance: A micro view. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 121(2), 238–251. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02705822

- Holt, J., Skali, A., & Thomson, R. (2021). The additionality of R&D tax policy: Quasi-experimental evidence. Technovation, 107, 102293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102293

- Jin, B., & Cho, H. J. (2018). Examining the role of international entrepreneurial orientation, domestic market competition, anechnological and marketing capabilities on SME’s export performance. Journal of Business & Industrial Marketing, 33(5), 585–598. https://doi.org/10.1108/JBIM-02-2017-0043

- Keesing, D. B. (1967). Outward-looking policies and economic development. The Economic Journal, 77(306), 303–320. https://doi.org/10.2307/2229306

- Knight, G., Moen, Ø., & Madsen, T. K. (2020). Antecedents to differentiation strategy in the exporting SME. International Business Review, 29(6), 101740. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2020.101740

- Krammer, S. M., Strange, R., & Lashitew, A. (2018). The export performance of emerging economy firms: The influence of firm capabilities and institutional environments. International Business Review, 27(1), 218–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2017.07.003

- Lachenmaier, S., & Wößmann, L. (2006). Does innovation cause exports? Evidence from exogenous innovation impulses and obstacles using German micro data. Oxford Economic Papers, 58(2), 317–350. https://doi.org/10.1093/oep/gpi043

- Lee, H., Kelley, D., Lee, J., & Lee, S. (2012). SME survival: The impact of internationalization, technology resources, and alliances. Journal of Small Business Management, 50(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00341.x

- Leonidou, L. C., & Katsikeas, C. S. (1996). The export development process: An integrative review of empirical models. Journal of International Business Studies, 27(3), 517–551. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.jibs.8490846

- Leontief, W. (1954). Mathematics in economics. Bulletin of the American Mathematical Society, 60(3), 215–233. https://doi.org/10.1090/S0002-9904-1954-09791-4

- Lewandowska, M. S., Szymura-Tyc, M., & Gołębiowski, T. (2016). Innovation complementarity, cooperation partners, and new product export: Evidence from Poland. Journal of Business Research, 69(9), 3673–3681. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.03.028

- Love, J. H., & Mansury, M. A. (2009). Exporting and productivity in business services: Evidence from the United States. International Business Review, 18(6), 630–642. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2009.08.002

- Love, J. H., & Roper, S. (2015). SME innovation, exporting and growth: A review of existing evidence. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 33(1), 28–48. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242614550190

- Love, J. H., Roper, S., & Zhou, Y. (2016). Experience, age and exporting performance in UK SMEs. International Business Review, 25(4), 806–819. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2015.10.001

- Máñez, J. A., Rochina-Barrachina, M. E., & Sanchis-Llopis, J. A. (2015). The dynamic linkages among exports, R&D and productivity. The World Economy, 38(4), 583–612. https://doi.org/10.1111/twec.12160

- Munkácsi, Z. (2009). Who exports in Hungary? Export concentration by corporate size and foreign ownership, and the effect of foreign ownership on export orientation. MNB Bulletin (Discontinued), 4(2), 22–33.

- Muñoz, C., Galvez, D., Enjolras, M., Camargo, M., & Alfaro, M. (2022). Relationship between innovation and exports in enterprises: A support tool for synergistic improvement plans. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 177(C), 121489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2022.1

- Okubo, T., Wagner, A. F., & Yamada, K. (2017). Does foreign ownership explain company export and innovation decisions?: Evidence from Japan. RIETI.

- Palangkaraya, A. (2012). The link between innovation and export: Evidence from Australia ’s small and medium enterprises (Working Papers DP-2012-08). Economic Research Institute for ASEAN and East Asia (ERIA). https://ideas.repec.org/p/era/wpaper/dp-2012-08.html

- Paul, J., Parthasarathy, S., & Gupta, P. (2017). Exporting challenges of SMEs: A review and future research agenda. Journal of World Business, 52(3), 327–342. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2017.01.003

- Penrose, E. T. (1960). The growth of the firm—A case study: The hercules powder company. Business History Review, 34(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.2307/3111776

- Pickernell, D., Jones, P., Thompson, P., & Packham, G. (2016). Determinants of SME exporting: Insights and implications. The International Journal of Entrepreneurship and Innovation, 17(1), 31–42. https://doi.org/10.5367/ijei.2016.0208

- Posner, M. V. (1961). International trade and technical change. Oxford Economic Papers, 13(3), 323–341. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.oep.a040877

- Radicic, D., & Djalilov, K. (2019). The impact of technological and non-technological innovations on export intensity in SMEs. Journal of Small Business and Enterprise Development, 26(4), 612–638. https://doi.org/10.1108/JSBED-08-2018-0259

- Roodman, D. (2009). How to do Xtabond2: An introduction to difference and system GMM in stata. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata, 9(1), 86–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536867X0900900106

- Roper, S., & Love, J. H. (2002). Innovation and export performance: Evidence from the UK and German manufacturing plants. Research Policy, 31(7), 1087–1102. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(01)00175-5

- Ruffin, R. J. (1988). The missing link: The ricardian approach to the factor endowments theory of trade. The American Economic Review, 78(4), 759–772.

- Saridakis, G., Idris, B., Hansen, J. M., & Dana, L. P. (2019). SMEs’ internationalisation: When does innovation matter? Journal of Business Research, 96, 250–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2018.11.001

- Serra, F., Pointon, J., & Abdou, H. (2012). Factors influencing the propensity to export: A study of UK and Portuguese textile firms. International Business Review, 21(2), 210–224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2011.02.006

- Smallbone, D., Saridakis, G., & Abubakar, Y. A. (2022). Internationalisation as a stimulus for SME innovation in developing economies: Comparing SMEs in factor-driven and efficiency-driven economies. Journal of Business Research, 144, 1305–1319. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.01.045

- Smith, V., Madsen, E., & Dilling-Hansen, M. (2002). Do R&D investments affect export performance? (CIE Discussion Papers No. 2002–09). University of Copenhagen. Department of Economics. Centre for Industrial Economics. https://EconPapers.repec.org/RePEc:kud:kuieci:2002-09

- Sousa, C. M. P., Martínez-López, F. J., & Coelho, F. (2008). The determinants of export performance: A review of the research in the literature between 1998 and 2005. International Journal of Management Reviews, 10(4), 343–374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2008.00232.x

- St-Pierre, J., Sakka, O., & Bahri, M. (2018). External financing, export intensity and inter-organizational collaborations: Evidence from Canadian SMEs. Journal of Small Business Management, 56, 68–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12390

- Tavassoli, S. (2018). The role of product innovation on export behavior of firms: Is it innovation input or innovation output that matters? European Journal of Innovation Management, 21(2), 294–314. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-12-2016-0124

- Van Beveren, I., & Vandenbussche, H. (2010). Product and process innovation and firms’ decision to export. Journal of Economic Policy Reform, 13(1), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/17487870903546267

- Verhoogen, E. A. (2008). Trade, quality upgrading, and wage inequality in the Mexican manufacturing sector *. Quarterly Journal of Economics, 123(2), 489–530. https://doi.org/10.1162/qjec.2008.123.2.489

- Vernon, R. (1966). International Investment and International trade in the product cycle. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 80(2), 190. https://doi.org/10.2307/1880689

- Veugelers, R., & Cassiman, B. (1999). Make and buy in innovation strategies: Evidence from Belgian manufacturing firms. Research Policy, 28(1), 63–80. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(98)00106-1

- Wagner, J. (2007). Exports and productivity: A survey of the evidence from firm-level data. The World Economy, 30(1), 60–82. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9701.2007.00872.x

- Wakelin, K. (1998). Innovation and export behaviour at the firm level. Research Policy, 26(7–8), 829–841. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(97)00051-6

- Wakelin, K. (2001). Productivity growth and R&D expenditure in UK manufacturing firms. Research Policy, 30(7), 1079–1090. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00136-0

- Wernerfelt, B. (1984). A resource‐based view of the firm. Strategic Management Journal, 5(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250050207

- Westhead, P., Wright, M., & Ucbasaran, D. (2001). The internationalization of new and small firms. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(4), 333–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00063-4

- Zou, S., Fang, E., & Zhao, S. (2003). The effect of export marketing capabilities on export performance: An investigation of Chinese exporters. Journal of International Marketing, 11(4), 32–55. https://doi.org/10.1509/jimk.11.4.32.20145

Appendix Appendix A

Table A1. Variable definitions.