ABSTRACT

This article aims to explore how a company’s board guides learning by connecting active owners, the board, and the management. We suggest that board-guided learning practices connecting the owners, the board, and the management can be vital for growth-oriented companies facing the challenges of success with limited resources. We draw on a qualitative study of 11 Finnish SMEs and employ learning theory taken further by opening the microfoundations of learning between the company’s board and individual owners, board members, and management. We created a framework showing how the board acts by guiding the learning practices, participation in them, and the temporality of the practices at board meetings. Learning not only happens when people meet, but the company’s board can create practices to enhance learning. The study advances learning theory by giving a more granulated picture of the microfoundations of learning between owners, the board, and management.

© 2024 The Author(s). Published with license by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC.

Introduction

Research on management and corporate governance has been abundant, but the conversations have, to a large extent, evolved on parallel tracks. Management research has developed to cover a broad area of topics, like learning and strategizing (Easterby-Smith et al., Citation2012), while the research on corporate governance has focused on aspects of owner interests and board work (Monks & Minow, Citation2011; Tricker, Citation2019). One reason for the separateness of the conversations can be traced to the hierarchical structure of an hourglass, depicting a structure where the CEO is the only connection between the company’s board and its management. However, the hourglass as a model does not accurately reflect the mode of operation for many companies today. These are not only family companies but companies with active owners ranging from entrepreneurial teams (Birley & Stockley, Citation2017) and business angel groups (Bonnet et al., Citation2022) to private equity investors (Harris et al., Citation2023) who position themselves as central stakeholders (Hall et al., Citation2015) and take an active role in board work and key management positions. These companies often have above-average growth ambitions in their industry, but they may also have limited knowledge resources compared to their established competitors.

The literature recognizes that the company’s growth is affected by the knowledge and insights of active owners (Croce et al., Citation2021; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018), diverse board members (Barroso-Castro et al., Citation2022; Lippi et al., Citation2023), and board activities (Ramaswamy et al., Citation2008; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018). Nonetheless, there is a gap in the literature regarding the learning practices that channel and transform the individual knowledge of owners, board members, and managers (OBM) into shared knowledge for the OBM. Further, literature has so far not focused on how the board, as a central actor in the company, guides these practices. Because the achievement of growth by using all available knowledge can be crucial for an SME’s survival, a better understanding of the learning practices that support growth is an important topic of research.

The purpose of this study is to explore how companies’ boards (Alvesson & Kärreman, Citation2001) guide learning by connecting with their owners and managers. As a starting point, we use organizational knowledge creation theory (Nonaka, Citation1994; Nonaka & Toyama, Citation2003) and the organizational learning framework (Crossan et al., Citation1999). These theories show that learning takes place as an interaction between individual (micro) and group-level (macro) activities but do not elaborate on how the interaction takes place. The microfoundations approach (Barney & Felin, Citation2013; Coleman, Citation1990; Foss et al., Citation2010) studies how team-level outcomes are affected by individual-level action and provides us with a beneficial approach (Felin et al., Citation2015) to deepen our understanding of how boards guide learning by connecting the OBM.

Our study has several practical and theoretical contributions. We show that learning does not just “happen” but can be consciously developed by preplanned practices. For this to materialize, the role of the company’s board should be extended (von Krogh et al., Citation2012) from board meetings to applying and guiding learning practices before, during, after, and between board meetings (Felin & Foss, Citation2009), inviting varying still-planned participation from the OBM. Active owners are shown ways to channel their knowledge to the company (Foss et al., Citation2021). From the point of view of a company’s management, implementation of practices to utilize the knowledge of the OBM can be of vital interest to achieve growth with limited resources. We contribute to learning theory and the microfoundations approach by giving a more granulated picture of how learning takes place between the OBM as individuals and teams (Felin et al., Citation2012) by dividing learning into a sequence of several learning practices that build upon each other.

We begin with a literature review on learning theories and microfoundations literature. We then continue with a detailed description of our qualitative research using the established Gioia (Gehman et al., Citation2018; Gioia et al., Citation2013) method. We discuss the findings and conclude by opening the microfoundations of how the board of a company enhances OBM learning by guiding learning practices, participation, and their temporality to the board meetings.

Theoretical framework and literature review

In order to understand how learning takes place between individuals and teams, we used theory on learning and literature on how learning is structured at the individual level and the team level. Since our research context is SMEs with active owners striving for fast growth, we start by reviewing the literature on how active ownership affects company growth.

It is recognized that active ownership is linked to fast growth (Croce et al., Citation2021). Active ownership in SMEs can be done both through managerial roles in the company (Kindström et al., Citation2022; Rasmussen et al., Citation2018) and through a close relationship between the owners and the company’s board (Ramaswamy et al., Citation2008). This relationship does not only include cooperation. It is also aimed at spotting gaps in the board’s knowledge (Barroso-Castro et al., Citation2022) and filling the gaps with suitable individuals. The literature does not explicitly show that the context of fast-growing companies and active owners condition how boards guide learning. However, the fact that boards guide learning can be seen as an implicit assumption since channeling the knowledge of the active owners to benefit the company is a central part of the board’s work. In addition to the advice given in board meetings, knowledge can be used together with the organization, for example, by participating in sales meetings with important potential clients.

We approach learning based on organizational knowledge creation theory (Nonaka, Citation1994; Nonaka & Toyama, Citation2003) and the organizational learning framework (Crossan et al., Citation1999) to describe how learning is structured as processes connecting individuals, groups, and the organization. Nonaka (Citation1994) proposes a theory for managing organizational knowledge creation through a continuous dialogue between tacit, individual knowledge and explicit organizational knowledge. Tacit knowledge is defined as highly personal and context-specific, like a mental model of the situation at hand, whereas explicit knowledge can be articulated, communicated, and shared. The basic assumption is that insights occur to individuals but do not transfer to the organization automatically. The interplay between the tacit, often nonverbal knowledge of individuals and its articulation creates explicit organizational knowledge and is the core process of organizational knowledge creation. The interplay between individual and organizational learning is further developed by Crossan et al. (Citation1999). They present the organizational learning framework as a multilevel structure between individuals, teams, and an organization connected by feedforward processes based on cognition and feedback processes based on experience. Organizational learning takes place as a dynamic sequence of feedforward and feedback processes, creating a tension between assimilating new learning and using what has been learned. The four central steps for learning are intuiting on an individual level, interpreting on a group level, integrating into the organizational level, and finally institutionalizing to close the loop back to the individual level. The framework has proven to be a robust tool for fostering understanding of the process of organizational learning and strategic renewal (Crossan & Berdrow, Citation2003; Jones & Macpherson, Citation2006; Zietsma et al., Citation2002).

The learning of boards is researched under different governance (Aguilera & Jackson, Citation2010; Leuz et al., Citation2009), both company-specific (Felin et al., Citation2023) and ownership (Corbetta & Salvato, Citation2014; De Massis & Foss, Citation2018) contexts. In this article, we aim to understand how boards guide learning by connecting with the owners and management. That makes the group learning context highly relevant for our purposes. Fiol and Lyles (Citation1985) describe group learning as improving actions through better knowledge and understanding. In contrast, Edmondson et al. (Citation2001) define it as improving the performance of a team, reflecting, and acting to obtain and process information to find, understand, and adapt to changes in the environment. London et al. (Citation2005) see group learning taking place in work that requires considerable skill and knowledge when members strive to look for opportunities to develop new skills and knowledge, invite challenging assignments, and are willing to take risks with new ideas. Increased flow of information and experimentation are shown to correlate with learning (Gibb, Citation1997) and higher growth (Sadler-Smith et al., Citation2003). The company´s board may have a significant role in group learning (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2020; Huse, Citation2018; Kaufman & Englander, Citation2005).

The learning theories state that learning happens in an interplay between individual and organizational learning but do not provide a closer examination of this interplay. To understand the interplay between individual (microlevel) and organizational (macrolevel) learning, the microfoundations approach (Contractor et al., Citation2019; Felin et al., Citation2015; Palmié et al., Citation2023) opens how causality unfolds between and within the micro- and the macrolevel. Since our study focuses on this interplay, the microfoundations approach is the most natural for our study. We study the microfoundations of board-guided learning by applying the Coleman “bathtub” (Coleman, Citation1990; Distel, Citation2019) framework. In this framework, the focus is to understand how social facts and conditions of individual action cause individual action that causes social outcomes. A general figure of the Coleman “bathtub” is presented in .

Figure 1. The Coleman (Citation1990) “bathtub.”

The research approach of microfoundations identifies some collective phenomena and seeks out an explanation of them by researching what happens one analytical level lower (Felin et al., Citation2012). The lower analytical level is not necessarily the individual level. However, Felin and Foss (Citation2009) underline that macrolevel explanations are deficient without origins on the individual level, like individual interaction, aggregation, and how these microdynamics lead to collective outcomes. Felin et al. (Citation2015) continue by stating that the microfoundations approach seems to be particularly influential in areas of macro management that stress “knowledge-based” assets, by giving attention to the transformation that occurs between the lower and the macrolevel. The microfoundations approach is thus instrumental for us to understand how the macrolevel of companies’ boards guide learning by connecting with the microlevel of the OBM. We find further support for using the microfoundations approach to research the microlevel of OBM by Linder and Foss (Citation2018), who point out the importance of regard for how the ownership structure affects interactions with managers. Our setting of active owners underlines this importance and is further emphasized by Foss et al (Citation2021, Citation2023), who highlight that owners vary in competence, but ownership competences appear to be learnable.

Aspects of interaction for learning have been studied in the context of strategic change. Ingley and Wu (Citation2007) examined the relationships between the board, organizational learning, and strategic change. They focused on feedforward and feedback learning and found that:

(1) supporting strategic change through organizational learning requires that boards balance both control and service roles, exercising appropriate power in relation to top management and having adequate access to essential company information; (2) boards with relatively higher diversity in their composition are more likely to enhance strategic change by facilitating organizational learning than those that are relatively homogenous; and (3) boards that pursue maximization of stakeholder value are more likely to influence strategic change by facilitating organizational learning than those that pursue maximization of shareholder value. (p. 141)

However, they did not focus on the microfoundations (Jarzabkowski, Citation2003) of the actual activities (Macpherson, Citation2005; Rigg et al., Citation2021) used for learning.

For our study, it is of particular interest to understand the board’s role in guiding learning. Boards represent a form of collective leadership (Raelin, Citation2018) and can use varying practices (Penrose, Citation1959) to steer the organization they serve. In the empirical part of this article, we study how the board uses different practices to guide learning in the OBM.

Methodology

Research design and process

Seeking answers to our research question, “How do boards guide learning by connecting the OBM?” requires an understanding of how a company’s board connects with managers and the organization (Pratt, Citation2009). By connecting, we refer to practices where the OBM can communicate together and have access to the same information. We aimed to search for an answer to our research question by examining the behavior of individual actors and groups and the interaction between them. In addition, we sought information about various organizational practices used to support interaction and learning. Existing knowledge in this area is limited, and we estimated that obtaining a rich and deep understanding of companies’ internal processes would be challenging with quantitative methods. With this in mind, we chose an approach based on qualitative methods (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Yin, Citation2003) that, as Denzin and Lincoln (Citation2003) express, enables the researcher to study the phenomena in their natural setting to make sense of, or to interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. This choice was also supported by our need to obtain data about the microfoundations (De Massis & Foss, Citation2018; Distel, Citation2019; Felin et al., Citation2015) of learning practices.

Suitable companies were sought out by following the idea of purposefully looking for information-rich cases (Eisenhardt, Citation2021; Patton, Citation1990). To achieve this target, we set up six criteria that regarded the governance model, company size, phase of the company, and willingness of key persons to participate:

For the upper end of the hourglass to be in place, we limited our study to companies with active owners, defined as an overlap of ownership roles, a board position, and an overlap of ownership and a management position.

We looked for companies with active board work in the sense that the board actively participated in strategy work, and board members showed commitment toward the company by also dedicating their time on company matters outside of board meetings. The latter was ensured during the interviews.

For the lower end of the hourglass to be in place, we limited our study to companies bigger than micro as defined by the European Commission (Citation2003) but under the maximum size of SMEs by the same definition. We set a maximum size to increase the probability of active ownership. In practice, these limitations implied companies with a personnel count between 10 and 250 people.

Companies should have a stated and active ambition to grow significantly, as growth-oriented companies can be assumed to use more learning practices than companies in a more stable phase.

Publicly listed companies were excluded because the governance code limits open communication with selected (central) owners.

We required the willingness of key informants to participate in the study by allocating enough time for interviews and the willingness to provide information openly.

To recruit interviewees, we approached the recognized Finnish network association of growth companies, “Boardman Grow” (boardmangrow.fi), with a request to participate in the study. Finnish companies have outperformed the European average in growth investments over the last 5 years. This makes Finland an ideal setting for research (Pratt, Citation2009). Finnish company law promotes a one-tier board structure and does not limit the share of executive or nonexecutive directors. Because of the liberty for companies to use the board composition they prefer, the legal setting does not have restrictions that would affect the results, so we believe our study is applicable to other companies with active owners (Foss et al., Citation2023).

We described the criteria set for the informants from the start in our contact request. A total of 12 companies contacted us, 11 of them fulfilled our criteria. In the company we excluded, an advisory board discussed all important matters, and the board of directors of the company acted only nominally. Selected companies all had clear growth targets, and most of them also showed remarkable growth in prior years (including a 40% average growth rate from 2018 to 2019 when the interviewees were recruited). All companies were privately owned with concentrated ownership, implying that although there may be many owners of the company, its actual voting power was limited to just a few individuals.

For informants, we selected persons who most likely would be central in their companies’ learning activities: principal owners, board chairs, board members, and CEOs. All but two informants were male. We did not collect detailed information about the individual career paths of interviewees, but all informants had extensive experience in business, either as entrepreneurs, managers, or board members. The informants were notified of the confidentiality of the interviews before they began. Since we aimed to learn what practices were used, we felt that interviews would give us the data we needed, especially keeping in mind that secondary data on practices of connecting the OBM would be unlikely to exist.

Data collection

Data was collected by carrying out semi-structured interviews (Bansal & Corley, Citation2011) to advance our understanding of what practices were employed for learning to take place both at the board level and the individual level. To get a more diverse view of the practices used and to make sure that practices were recalled equally (Eisenhardt, Citation1989), we aimed to conduct interviews with two persons from each company wherever possible. This goal was achieved in eight companies, giving us a total number of 20 interviews. The interviews were conducted in the informants’ native language (Finnish) to eliminate misunderstandings due to language.

The interviews were divided into three thematic areas. We started by asking the informants to go through basic information about the company, its operations and growth targets, plans, and challenges – the next theme related to the organization itself and the ways the company’s governance was arranged. The themes in the first two sections provided context for later questions – the third theme related to the owners, the board, and the management and their interaction. We did not ask direct questions related to learning but tried to figure out what actually happens when influential organizational actors interact to achieve the company’s objectives. When we analyzed the data, we observed that much of the interaction was aimed at learning.

A replication of a learning pattern (Yin, Citation2015) emerged. Four learning practices were found, and all 11 companies’ boards used at least one practice to guide learning. This provided us with enough data for conclusions (Pratt, Citation2008) and affirmed that the number of informants was adequate for our study.

The data collection was done for three months, from March to June of 2020. As this was the time when the COVID-19 pandemic broke out, it provided a research setting with an exceptionally uncertain environment that most probably caused the actors to intensify the practices of the OBM to secure the future of their respective companies. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed. As a result, 20 interviews from 11 companies were obtained and included in this study ().

Table 1. Summary of the companies and interviews.

Since we wanted to understand the lived experiences of the informants (Gehman et al., Citation2018), the Gioia method (Gioia et al., Citation2013) seemed most suitable to analyze the data (Gephardt, Citation2004), that is, to extract concepts, aggregate them and find relationships between them for the basis of our theoretical contribution. To ensure a solid data structure, we used NVivo’s qualitative data analysis software. For a broader perspective, one of the writers conducted the interviews, and another handled the data analysis. The authors did not know the interviewees beforehand (Anteby, Citation2008). All the authors have several decades of personal experience regarding active ownership and board work. We believe our experience helped to keep the interviews focused (Bansal et al., Citation2018), but we wanted to avoid leading the interview process based on our own experience (Arino et al., Citation2016; Tracy, Citation2010). As an example, if the interviewee said, “You know how it is with board work,” we did not simply nod and continue but instead pressed on with, “Could you tell me more specifically what you are referring to?.”

We started with markedly open questions like “Can you tell me about your experience as a board chair?.” The answers primarily focused on the company’s challenges and development during their tenure. The company story was the first thing that came to mind for every informant, so we continued with open but directed questions regarding individual work, like “Can you talk about the board work in the company?.” The answers began with descriptions of general work tasks, and we continued by asking if these had any connections to other parts of the OBM. At this stage, we emphasized giving a voice to the interviewees’ narratives of events (Gioia & Chittipeddi, Citation1991). We began to get a flow of comments, from which we extracted 86 first-order informant-centered expressions that formed the basis of our analysis. We continued by eliminating overlapping comments both within and between companies. The cohesion in the comments made it possible to condense them further into 28 first-order concepts. In tandem with this analysis, we examined whether these first-order concepts could be articulated through the lens of learning theories (Klag & Langley, Citation2013) to help us describe and explain how the board guides learning by connecting the OBM (Gioia et al., Citation2013). Altogether, we found seven second-order themes explaining learning. Four second-order themes showed practices in accordance with the steps in learning theory (Crossan et al., Citation1999) and the Coleman (Citation1990) “bathtub,” and three second-order themes described how the board guided learning practices, participation, and temporality of board meetings. This structure enabled us to group the data in the two aggregate dimensions of learning practices and guiding of learning practices. This data provided a solid data structure (Gehman et al., Citation2018). The data structure is illustrated in .

With this data structure, we could process the data with existing theory (Alvesson & Kärreman, Citation2007) to give us an understanding of the concepts and their interrelationships (Corley & Gioia, Citation2011; Gioia & Pitre, Citation1990) on how boards guide learning by connecting the OBM.

Findings

The models of Nonaka (Citation1994) and Crossan et al. (Citation1999) both describe a learning spiral in four steps. Our findings support this by identifying the microfoundations of the four steps connecting the OBM. Furthermore, our findings reveal that the board guides learning practices and the participants in these practices. Finally, we found that the board made sure that the practices were in a temporal connection with the board meetings. In the following passage, we discuss these findings one by one. For clarity, we talk nearly exclusively about the managers, with the exception of this being when the discussion turns to involve other individuals from the organization.

The four steps of learning in the learning spiral

Next, we discuss how the board guides learning step by step according to the learning theories by connecting the OBM. We do this by reflecting on the learning activities and microfoundations described by our informants on the learning and knowledge creation models of Nonaka (Citation1994) and Crossan et al. (Citation1999).

Learning between the OBM as groups, respectively, and the OBM individuals

Four companies used the practice of communicating board decisions to their personnel after board meetings. All the OBM were also invited to do so. Digital communication tools used by the company (Teams, Zoom, or Slack) were used to make it easy for all to join the presentation:

After the board meeting, the board chair uses Slack to write the whole organization an account of what we talked about and learned in the board meeting. Everyone in the company can follow it, and often, it leads to interesting comments from the organization. By this, we want to make sure that communications work between the board and the whole organization. The CEO of Company C.

The hourglass model would have the CEO communicating the board’s decisions to managers without direct contact between the board and the managers. We got the impression that the CEOs saw this form of connecting as beneficial for themselves by helping them form a shared vision (Jansen et al., Citation2023) for the company. By inviting comments from individuals in the organization, the OBM wanted (and were humble enough) to learn what reactions the board decisions caused. The individuals in the organization learned about the reasoning behind the board’s decisions by asking clarifying questions. The direct information flow from the board meetings to company personnel prevented information gaps from being created. It gave the personnel the opportunity to add their insights to topics under discussion. This, in turn, enabled the board to learn from individuals in the organization.

Our findings suggest that boards learn by employing practices following the steps of learning suggested by both organizational knowledge theory (Nonaka, Citation1994) and the organizational learning framework (Crossan et al., Citation1999). Although the companies used all the steps in the learning theories, surprisingly, none of the companies explicitly cited learning as the reason they used the practices. Anyway, the interviews included several references regarding the value of other participants’ knowledge and insights, irrespective of their position in the OBM. Instead of talking about learning as such, it was often articulated as a desire to maximize the use of scarce resources by absorbing all available knowledge and keeping up the pace of activities.

Learning between the OBM individuals

Sharing tacit knowledge between individuals has limited possibilities for creating organizational knowledge. Even so, it is a centerpiece of learning as new knowledge creation begins with tapping into the individual’s experiences and often highly subjective insights (Nonaka, Citation1994). Based on our findings, the owners and board members were expected to provide their expertise directly to managers both proactively and when the management expressed a need for it. Providing advice and expertise to the managers from the owners and the board was only one side of the coin. From a learning perspective, it is essential to recognize that these discussions provided owners and managers the chance to gain deeper knowledge about the business situations, challenges, and needs it had for further development: “I have experienced that it is essential to ask questions that might be bypassed in daily work,” noted a board member of company L.

The hourglass approach would limit the owners’ activity to the company’s annual general meetings and the board members’ activity to board meetings. In contrast, we found that the owners and board members learned about the company’s activities by talking to managers during their daily work, often by coming to the company’s premises. This happened both by prescheduled arrangements and by stopping by spontaneously. In every company, the managers appreciated the possibility of learning from the experience of the owners and board according to their expertise. The interaction between the OBM was considered necessary for learning, which was seen in active dyadic interaction. It was common for companies to encourage borderless individual communication between the OBM:

We have to arrange a time to be together, to keep the guys involved in development, to listen, and to take care of the sense of belonging together. The growth in headcount makes it imperative to share information and ensure that we work in the same direction. Co-owner of Company A.

Owners, board members, and managers showed respect for one another’s knowledge and insights. They expressed a desire to learn from each other to create value for their respective companies. In light of the interviews, it was typical for all the companies to encourage day-to-day dyadic communication (Sievinen et al., Citation2022) between the OBM. By encouraging the sharing of (tacit) knowledge, the companies also wanted to ensure that individuals shared the same ideas regarding the direction in which the company should go (Bundy et al., Citation2018). At the same time, the discussions enabled and promoted learning between individual owners, board members, and managers.

Learning between the OBM as individuals and the OBM as groups, respectively

Learning between OBM individuals and respective groups was common in all companies. Individuals with knowledge and potentially valuable input were encouraged to participate in group meetings:

We do not meet around a specific theme; talking together is a part of our daily way of working. When we meet with the top management team, we are in an open office, and the sales leaders can overhear us and often interrupt us to make comments. Actually, we took down a wall that was between us so the discussions could be heard. Co-owner of Company A.

The narrow passage in the hourglass is the CEO as the connection between the board and the managers. This was eliminated in two ways: The owners and the board joined management meetings where they were able to contribute to the managers’ learning through their experience, and the managers were invited to board meetings where they were able to contribute to board learning through their expertise and insights. The CEOs of all the companies were interviewed, and, perhaps surprisingly, none of them seemed jealous about being a gatekeeper between the board and the managers:

From the start, I have had the thought that I am not jealous of board members interacting with the organization. Another idea we have employed is the concept that anyone from the organization can take part in a board meeting. It is important to communicate what happens in board meetings, and we also believe that many people have good views about the themes to be discussed. The CEO of Company C.

Five companies used the practice of inviting individual managers to board meetings for the board to learn about specific areas of expertise from the managers. Six companies (of which three were in the previous group) used the practice of inviting the owners and the board members to top management meetings so that the managers could learn from the experience of the owners and the board. One company gave the owners the opportunity to learn by sending them monthly reports directly from the managers. The board meetings were almost always monthly, with occasional additional meetings as needed. Management meetings were held weekly or every second week. What surprised us was that the freedom to take part in the board meetings for anyone in the organization was used only marginally. It seems that offering the possibility to partake in the board meetings communicated respect for the individual and eliminated thoughts of secrecy in the board meetings. All the same, the actual issues on the board agenda did not spark any interest in participating.

Learning between the OBM as groups, respectively

The board members regularly communicated with managers between board meetings (Kindström et al., Citation2022) regarding important issues. The board continually kept the owners informed on the company’s development: “In a smaller company, the board is so much closer to the business and more deeply and dynamically involved: it is a completely different world compared to those bigger companies,” a board member of company F pointed out.

Preparations for important decisions were typically made through discussions, including the board and managers, and were often initiated by the managers. Depending on the issue, the formal decision was made either by the board or by the managers.

One or two of the owners were board members in all but two companies. In the two differing companies, the central owner worked as the CEO. This created a setting where the owners could learn in board meetings. In some companies, learning between the owners and the board was taken even further: “In growth-oriented companies, the board’s time should primarily be used to develop and advance the company – we are agile; when something comes up, we always reach out to the owners, always,” emphasized the board chair of company E.

In company E, interaction between the owners and the board was seen as crucial for the company’s development and for ensuring that both the board and the owners acknowledged all aspects of important issues at hand. The owners learned about the business possibilities presented by the board, and the board learned about the owner preferences that the owners articulated. In a similar manner, the board of company B scheduled meetings for the owners and the managers to discuss the company’s next steps together. Combining learning about owner preferences with learning about business possibilities helped direct the actions of the company.

The board guides the learning practices, participation, and temporality to board meetings

In addition to identifying various practices for learning by connecting the OBM, we found that the practices had not emerged spontaneously, nor were they temporal. From the outset, the owners wanted to contribute and learn, the board strived for value creation, and managers appreciated learning from owners and the board. The combination of these desires resulted in a role for the board where it arranged and guided practices for learning between the OBM and increased learning by guiding participation in those practices.

Guiding participation in practices

The hourglass model separates the work and learning opportunities of the board and the managers into their respective groups and does not provide a role for the owners in the day-to-day activities of the company. What we found was that the board in all companies guided the participation of additional participants in their meetings, and so did the managers regarding their meetings:

You have to have the courage to look in the mirror and confess that you know only a fraction of what those in the organization know, and be humble in recognizing that you work with an organization that has much know-how that accumulates so fast that the board is not keeping up and cannot keep up with the pace. The board chair of Company H.

As we are this kind of small group, we need the input of all [organization members] to achieve our common goal. The CEO of Company D.

The choice of being a participant in the board and management’s meetings was guided by the principle that individuals who had some knowledge or insight that others could learn from would participate (Kaufman & Englander, Citation2011) in respective meetings, regardless of whether they were owners, board members, or managers. As Kaufman and Englander (Citation2005) put it: “Rather than restrict insiders to one or two, boards should include a group of employees (managers and workers) who bring the firm’s know-how to the table” (p. 9). The companies in our study took this thought a step further:

We have to take this new mindset to board work so that the employees can contribute a lot to it. One question is the old hierarchical versus the new trust-based approach to board meetings. The old way was that board meetings were held in secret, with only the CEO and the presenting persons during the time of their presentation. We have wanted to swim in the other direction, so we always have the persons responsible for the meeting’s themes attending the entirety of the meetings. Not being a listed company gives us the freedom to speak openly. The CEO of Company C.

The board did not only regard learning as necessary by having knowledgeable individuals as board members, they took a larger perspective by recognizing that learning was advanced by having other knowledgeable persons present, as well as outside their own presentations.

Guiding practices for learning

At the time of the interviews in the spring of 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic had caused most individuals to telework. This was not entirely new since the geographical dispersion of the OBM had previously created the need to arrange remote meetings rather often:

We work in different geographical locations. It becomes difficult to form a tribe since we do not sit around the same campfire. We must arrange a time to be together, to keep the guys involved in development, to listen, and to take care of the sense of belonging together. The growth in headcount makes it imperative to share information and work in the same direction. Owner of Company A.

We have a WhatsApp group among board members where we can send instant messages about issues like where we are going and if there is a need to react and that kind of stuff. Maybe we have increased the frequency of actions there. The CEO of Company I.

I have started to have this gut feeling that the work of the board should involve some activities between board meetings, such that there would be some sort of discussion going on all the time. The board chair of Company D.

One way of learning was to have practices without a specific agenda. The learning of the OBM was focused on reacting to new information and insights from individuals. Another practice for learning was clearly theme-focused:

For a long time, we have informally had these task forces, like the one we now have because of COVID-19. They do not make the decisions for the TMT, but we [in task forces] really guide and direct the business and prepare issues that we see will occur so that they will be discussed in the TMT. The board chair of Company H.

In these theme-focused learning practices, the reasoning was to get individuals together who could best contribute to the theme so that the board or managers could learn and make decisions by being better informed. The starting point for the practices was to maximize learning wherever there was a possibility to learn:

I do not at all like the traditional governance code; that seems to be praxis for listed companies, where you have the pyramids of board and organization meetings only at the tips, with all communication going through the CEO. If you have looked at the governance code, much emphasis is put on the separation of operative matters and board matters. Moreover, I think, frankly speaking, this is a very old-fashioned way to look at things … we work in a way that all the board members have disembarked into the organization. It eliminates the CEO-filter threshold and supports a self-guided way to work as well as transparency … I appreciate that our board members can directly connect with our key personnel. I have thought that the more we can activate the board members this way, the better it is for the company. The board chair of Company C.

Then we have this forum for partners [implying owners]; we always meet around lunch between board meetings. The forum aims to share information, but it is also a nice setting to hear about and discuss important issues. The CEO of Company A.

The owners of all the companies had an interest in contributing their knowledge and insights to the company. In all the companies, there was some overlap between owners and the board. This made it natural to create practices to learn from the owners. In the traditional hourglass model, there would have been no role for the owners to contribute with their learning if they happened to be outside the board.

Guiding the temporality of the practices to the board meetings

All the companies in this study had a stated desire to grow, and it was evident that the benefit of learning was seen to be the creation of a shared understanding about the direction of the company and the clarification of roles:

From the start, we have had growth-oriented organizational roles, and keeping the focus is not easy. Planned, controlled growth demands a very systematic and explicit model … when the roles are clear, the board handles matters that come from the organization; the board is clearly more active in fast-growing companies. The board chair of Company G.

The learning practices implied increasing and broadening communication in different ways. The increased communication caused a need to clarify where the board should be prepared to be active (Rasmussen et al., Citation2018), for example, with additional board meetings to decide on urgent issues.

The learning practices were also used to shorten the time between board decisions and implementation of the decisions:

And we implemented the strategy work in a way that we implemented it [the strategy] simultaneously when we were creating it. That is exceptional. Usually, implementation takes place only after [the strategy work], still we involved the entire staff in the strategy process. In that way, we had the opportunity to highlight three to four themes that we now go through in every [board] meeting, and in practice, those are sort of strategic tasks, and we follow their development and implementation. Moreover, we do it in every board meeting. The board chair of Company I.

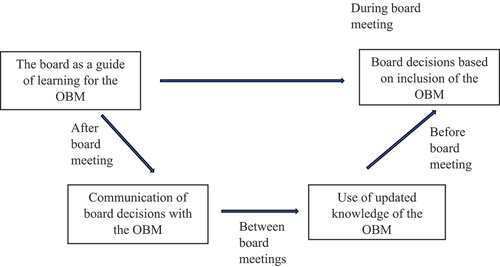

According to Crossan et al. (Citation1999), learning takes place between feedforward decisions, and feedback on results is achieved by these decisions. This was done through a temporal connection of the learning practices to the board meetings. The learning practices, participation, and temporality of the board meetings are summarized in .

Table 2. The learning practices, participation, and temporality to board meetings.

The focus of the board regarding learning was on advancing the company by both making use of the knowledge (Felin et al., Citation2012, Citation2015) the OBM had and by enriching it with new insights about development in the company’s area and advancement. A broad input of insights was used by engaging the OBM in considering the direction (Felin et al., Citation2023; Foss et al., Citation2023) of the company. All the companies that used at least two practices for learning had employees as owners, which probably reflects an interest in tying employees to the company through both ownership and interaction with the OBM. Only in companies with over 20 employees did the board communicate its decision after the board meeting, probably because the CEO could communicate board decisions directly in smaller companies. Companies with both executive and nonexecutive board members all used their nonexecutives to prepare for board meetings, which can be presumed to be due to the close cooperation they have in board meetings. When the choice of direction was set, the board’s focus was on the guidance (Kroll et al., Citation2008) of action. A desire to combine diversity of thought and knowledge with unity and clarity of goals (Linder & Foss, Citation2018) seemed to be the common purpose of OBM learning.

Discussion and conclusion

Research concerning the operations of the OBM has largely concentrated on applying governance theories such as agency theory (Jensen & Meckling, Citation1976), stewardship theory (Donaldson & Davis, Citation1991) and resource dependence theory (Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978) to understand why the managerial groups perform their tasks. In this present study, we suggest that learning theories and the microfoundations approach help us understand those processes through which the OBM develops its cooperative relationships. Our key findings are that the board in an SME is in a central position to guide learning between the OBM through planned practices, participation in them and their temporality to board meetings. Learning between the OBM is recognized in earlier literature on growing companies. Croce et al. (Citation2021) recognized that fast growing companies are in a good position to take advantage of external investors' knowledge. In contrast, external board members bring the necessary knowledge needed for growth into the company (Barroso-Castro et al., Citation2022), and they help to broaden the leadership platform (Kindström et al., Citation2022). We add to this discussion on learning between the OBM by empirically showing the microfoundations underlying the practices the OBM use to learn from each other. From a theoretical standpoint, we show that learning between the OBM is an intentional activity, and does not just “happen” as learning theory has so far assumed.

Theoretical contributions

Our study aimed to understand the microfoundations of learning practices for the OBM. As expected, we found learning practices that correspond to the four steps of learning posited by learning theories (Crossan et al., Citation1999; Nonaka, Citation1994). Learning theory, however, assumes that learning just “happens.” Our first contribution to learning theory is to show that board-guided learning practices can purposefully advance learning. Regarding learning, Croce et al. (Citation2021) say that fast-growing SMEs are better positioned to take advantage of external knowledge inflows. Barroso-Castro et al. (Citation2022) continue that small business managers and owners should be prepared to facilitate successful growth. We continue this conversation by elaborating on the practices to take advantage of knowledge and showing what “facilitating” practices can include.

Our second theoretical contribution is to extend our knowledge of learning theories considering the microfoundations approach. Learning theories only describe the steps of learning but do not impart what practices constitute the steps. Understanding higher-level organizational outcomes by researching lower-level individual actions is the core of the microfoundations approach. For this reason, the microfoundations approach is insightful in explaining board-guided learning practices. Nonaka (Citation1994) describes organizational learning as a continuous dialogue between tacit, individual knowledge and explicit organizational knowledge. Crossan et al. (Citation1999) say that organizational learning takes place as a dynamic sequence of feedforward and feedback processes. The microfoundations approach provides us with insights into what practices are used for the continuous dialogue and dynamic processes mentioned in the learning theories. Since the interplay between higher and lower levels is central in both learning theories and the microfoundations approach, we suggest that the use of the microfoundations approach would be beneficial for further development of the learning theories.

We also show that the learning spiral of feedforward and feedback is not a continuous advancement of learning. Instead, it involves broadening up to sense what should be learned by inviting OBM participation in learning and narrowing down by way of goal-focused board decisions. The shared learning practices connecting the OBM contrast with the hourglass model that emphasizes the separate roles of owners, the board, and the managers. Literature supports the notion that a board does not strive to create value separately but rather in cooperation with its organization (Barroso-Castro et al., Citation2022; Huse, Citation2018) and stakeholders (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2020).

The way that boards guide OBM learning can be described using the Coleman “bathtub” (Coleman, Citation1990) of microfoundations as a model of connecting the company’s board as a group with the OBM individuals using practices according to the four steps in the learning spiral of Crossan et al. (Citation1999). This adaption of the Coleman “bathtub” is illustrated in .

Based on our findings, we propose that boards guide the learning of the OBM by guiding the learning practices connecting the OBM, participation in these practices to maximize learning, and the temporality of the practices to board meetings. We further propose that practices include a variation between a broadening search for what should be learned and a narrowing to go deeper into learning the selected themes better. Felin et al. (Citation2015) say that: “the lower level need not necessarily be reduced to some kind of actor, but could feasibly be the result of social interaction as well” (p. 587). We open this social interaction by showing that it is constructed of planned, consecutive practices. These practices have a cascading participation: Small teams prepare items for the larger board meeting, and after the board meetings, the whole organization is invited to comment on the board’s decisions. Felin et al. (Citation2015) continue by positing that microfoundations “[focus] on a ‘larger’ micro to macro leap in seeking to move from individuals to firms” (p.607). We show that the larger micro-to-macro leap is constructed of several practices that build upon each other. The microfoundations approach emphasizes the interplay between individuals and groups. Our study also shows the importance of practices that connect the OBM both as groups and as individuals. We suggest that continuing the conversation on OBM learning is essential. Without guiding learning practices that both absorb existing knowledge and serve to create new knowledge and insights, growing companies with a scarcity of resources can face vital “resource leaks.”

Practical implications

Our study has practical implications for the OBM respectively. These are summarized in below. First, it is beneficial if owners articulate what they see as the best way to channel their knowledge and insights to the company to avoid unnecessary broad involvement (Kindström et al., Citation2022). Second, the board should establish practices both to prepare issues before board meetings and to discuss board decisions with the organization afterward. The board should also plan which individuals to include in board meetings according to the agenda and agree upon practices for the interaction of the OBM between board meetings. Third, the managers must recognize the most knowledgeable individuals depending on the board issues and suggest their involvement in the preparation for and participation in the board meetings. Further, the managers should engage everyone in the organization to share insights and ideas with the OBM after and between board meetings. Finally, we believe that participating individuals from the organization not only contribute with their expertise but also find it rewarding to interact more closely with the OBM.

Limitations and future research directions

Our work has significant limitations. First, the results are applicable only to nonlisted companies. The corporate governance codes for listed companies have strict rules regarding the sharing of insider information. This severely restricts the board’s possibility of including those who are not directors in board work. Second, the size of the company poses limitations. An SME can use practices that would be difficult to use in large organizations. Third, the results of the study are applicable only to companies operating under a Fennoscandian governance context that promotes a one-tier board structure, whereby the board can consist of both executive and nonexecutive directors. It would be of interest to study if and how the cooperation between the OBM differs in companies that have a two-tier board structure. The two-tier structure has an independent supervisory board and a management board. These boards have separate roles and meetings, implying that the practices for cooperation of the OBM would most likely differ. Growth-oriented SMEs with limited resources would have to modify their practices in this legal setting to leverage the resources available to them.

An interesting avenue for further research would be an examination of how board composition and size affect the extent to which the board is involved in providing guidance and direct learning to managers. The number of owners on the board, gender aspects, and cultural diversity among board members could be expected to affect both practices and contents regarding how the board guides learning. One potentially interesting area for research could be to study if the board focus on learning for the OBM varies depending of the growth stage of the company (Croce et al., Citation2021).

The focus of our study has been the practices of learning, not learning content. We suggest it would be of interest to connect studies of learning practices with studies on learning content, such as handling perception gaps (Junge et al., Citation2023), absorptive capacity (Schønning et al., Citation2019), and dynamic capabilities (Kurtmollaiev, Citation2020), both for innovation (Sheehan et al., Citation2023) and scaling high-growth companies (Jansen et al., Citation2023).

In some of the companies, learning practices seemed to take place before, during, after, and between board meetings. Studying this temporal aspect and interconnectedness between board meetings and learning practices could provide new insights into how boards guide learning. This would also be in line with earlier studies (Bezemer et al., Citation2018) that highlight the potential and need for further unpacking of the temporal dimensions of boards’ decision-making processes.

The boards in our study were reasonably small. A company with a minimum board size might have difficulties allocating resources for guiding learning practices for the OBM. In contrast, a very large and diverse board might be composed with the thought to be somewhat self-sufficient. A future avenue for research would be to study whether there is a curvilinearity between diversity, board size, and how the board guides learning by connecting the OBM.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Aguilera, R. V., & Jackson, G. (2010). Comparative and international corporate governance. Academy of Management Annals, 4(1), 485–556. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2010.495525

- Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2001). Odd couple: Making sense of the curious concept of knowledge management. Journal of Management Studies, 38(7), 995–1018. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00269

- Alvesson, M., & Kärreman, D. (2007). Constructing mystery: Empirical matters in theory development. Academy of Management Review, 32(4), 1265–1281. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.26586822

- Anteby, M. (2008). Moral grey zones. Princeton University Press.

- Arino, A., LeBaron, C., & Milliken, F. J. (2016). Publishing qualitative research in academy of management discoveries. Academy of Management Discoveries, 2(2), 109–113. https://doi.org/10.5465/amd.2016.0034

- Bansal, P., & Corley, K. (2011). The coming of age for qualitative research: Embracing the diversity of qualitative methods. Academy of Management Journal, 54(2), 233–237. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2011.60262792

- Bansal, P., Smith, W. K., & Vaara, E. (2018). New ways of seeing through qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 61(4), 1189–1195. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2018.4004

- Barney, J., & Felin, T. (2013). What are microfoundations? Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(2), 138–155. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0107

- Barroso-Castro, C., Domínguez-CC, M., & Rodríguez-Serrano, M. Á. (2022). SME growth speed: The relationship with board capital. Journal of Small Business Management, 60(2), 480–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1717293

- Bezemer, P., Nicholson, G., & Pugliese, A. (2018). The influence of board chairs on director engagement: A case-based exploration of boardroom decision-making. Corporate Governance an International Review, 26(3), 219–234. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12234

- Birley, S., & Stockley, S. (2017). Entrepreneurial teams and venture growth. In D. L. Sexton & H. Landström (Eds.), The Blackwell handbook of entrepreneurship (pp. 287–307). Blackwell Publishers Ltd.

- Bonnet, C., Capizzi, V., Cohen, L., Petit, A., & Wirtz, P. (2022). What drives the active involvement in business angel groups? The role of angels’ decision-making style, investment-specific human capital and motivations. Journal of Corporate Finance, 77, 101944. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101944

- Bundy, J., Vogel, R. M., & Zachary, M. A. (2018). Organization-stakeholder fit: A dynamic theory of cooperation, compromise, and conflict between an organization and its stakeholders. Strategic Management Journal, 39(2), 476–501. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2736

- Coleman, J. S. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press.

- Contractor, F., Foss, N. J., Kundu, S., & Lahiri, S. (2019). Viewing global strategy through a microfoundations lens. Global Strategy Journal, 9(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1002/gsj.1329

- Corbetta, G., & Salvato, C. A. (2014). The board of directors in family firms: One size fits all? Family Business Review, 17(2), 119–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-6248.2004.00008.x

- Corley, K. G., & Gioia, D. A. (2011). Building theory about theory building: What constitutes a theoretical contribution? Academy of Management Review, 36(1), 12–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2009.0486

- Croce, A., Ughetto, E., Bonini, S., & Capizzi, V. (2021). Gazelles, ponies, and the impact of business angels´ characteristics on firm growth. Journal of Small Business Management, 59(2), 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1844489

- Crossan, M., & Berdrow, I. (2003). Organizational learning and strategic renewal. Strategic Management Journal, 24(11), 1087–1105. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.342

- Crossan, M. M., Lane, H. W., & White, R. E. (1999). An organizational learning framework: From intuition to institution. The Academy of Management Review, 24(3), 522–537. https://doi.org/10.2307/259140

- De Massis, A., & Foss, N. J. (2018). Advancing family business research: The promise of microfoundations. Family Business Review, 31(4), 386–396. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486518803422

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2003). Strategies for qualitative inquiry (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Distel, A. P. (2019). Unveiling the microfoundations of absorptive capacity: A study of Coleman’s bathtub model. Journal of Management, 45(5), 2014–2044. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206317741963

- Donaldson, L., & Davis, J. H. (1991). Stewardship theory or agency theory: CEO governance and shareholder returns. Australian Journal of Management, 16(1), 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/031289629101600103

- Easterby-Smith, M., Thorpe, R., & Jackson, P. (2012). Management research (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Edmondson, A., Bohmer, R., & Pisano, G. (2001). Speeding up team learning. Harvard Business Review, 79(9), 125–132.

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (2021). What is the Eisenhardt method, really? Strategic Organization, 19(1), 147–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127020982866

- European Commission. (2003, May 20). Official journal, L 124, 0036–0041.

- Felin, T., & Foss, N. J. (2009). Organizational routines and capabilities: Historical drift and a course-correction toward microfoundations. Scandinavian Journal of Management, 25(2), 157–167. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scaman.2009.02.003

- Felin, T., Foss, N. J., Heimeriks, K. H., & Madsen, T. L. (2012). Microfoundations of routines and capabilities: Individuals, processes, and structure. Journal of Management Studies, 49(8), 1351–1374. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01052.x

- Felin, T., Foss, N. J., & Ployhart, R. (2015). The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 575–632. https://doi.org/10.5465/19416520.2015.1007651

- Felin, T., Kauffman, S., & Zenger, T. (2023). Resource origins and search. Strategic Management Journal, 44(6), 1514–1533. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3350

- Fiol, C. M., & Lyles, M. A. (1985). Organizational learning. The Academy of Management Review, 10(4), 803–813. https://doi.org/10.2307/258048

- Foss, N. J., Husted, K., & Michailova, S. (2010). Governing knowledge sharing in organizations: Levels of analysis, governance mechanisms, and research directions. Journal of Management Studies, 47(3), 455–482. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2009.00870.x

- Foss, N. J., Klein, P. G., Lien, L. B., Zellweger, T., & Zenger, T. (2021). Ownership competence. Strategic Management Journal, 42(2), 302–328. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3222

- Foss, N. J., Klein, P. G., Lien, L. B., Zellweger, T., & Zenger, T. (2023). Ownership competence: The enabling and constraining role of institutions. Strategic Management Journal, 44(8), 1955–1964. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.3494

- Gabrielsson, J., Huse, M., & Åberg, C. (2020). Corporate governance in small and medium enterprises. In H. K. Anheier & T. Baums (Eds.), Advances in corporate governance: Comparative perspectives (pp. 82–110). Oxford University Press.

- Gehman, J., Glaser, V. L., Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D., Langley, A., & Corley, K. G. (2018). Finding theory-method fit: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of Management Inquiry, 27(3), 284–300. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617706029

- Gephardt, R. (2004). What is qualitative research and why is it important? Academy of Management Journal, 47(4), 454–462. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2004.14438580

- Gibb, A. A. (1997). Small firms´ training and competitiveness, building upon the small business as a learning organisation. International Small Business Journal, 15(3), 13–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242697153001

- Gioia, D. A., & Chittipeddi, K. (1991). Sensemaking and sensegiving in strategic change initiation. Strategic Management Journal, 12(6), 433–448. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250120604

- Gioia, D. A., Corley, K. G., & Hamilton, A. L. (2013). Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational Research Methods, 16(1), 15–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428112452151

- Gioia, D. A., & Pitre, E. (1990). Multi-paradigm perspectives on theory building. Academy of Management Review, 15(4), 584–602. https://doi.org/10.2307/258683

- Hall, M., Millo, Y., & Barman, E. (2015). Who and what really counts? Stakeholder prioritization and accounting for social value. Journal of Management Studies, 52(7), 907–934. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12146

- Harris, R. S., Jenkinson, T., Kaplan, S. N., & Stucke, R. (2023). Has persistence persisted in private equity? Evidence from buyout and venture capital funds. Journal of Corporate Finance, 81, 102361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2023.102361

- Huse, M. (2018). Value-creating boards: Challenges for future research and practice. Cambridge University Press.

- Ingley, C., & Wu, M. (2007). The board and strategic change: A learning organization perspective. International Review of Business Research Papers, 3(1), 125–146.

- Jansen, J. J. P., Heavey, C., Mom, T. J. M., Simsek, Z., & Zahra, S. A. (2023). Scaling-up: Building, leading and sustaining rapid growth over time. Journal of Management Studies, 60(3), 581–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12910

- Jarzabkowski, P. (2003). Strategic practices: An activity theory perspective on continuity and change. Journal of Management Studies, 40(1), 23–55. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.t01-1-00003

- Jensen, M. C., & Meckling, W. H. (1976). Theory of the firm: Managerial behavior, agency costs, and ownership structure. Journal of Financial Economics, 3(4), 305–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(76)90026-X

- Jones, O., & Macpherson, A. (2006). Inter-organizational learning and strategic renewal in SMEs, extending the 4I framework. Long Range Planning, 39(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2005.02.012

- Junge, S., Luger, J., & Mammen, J. (2023). The role of organizational structure in senior managers´ selective information processing. Journal of Management Studies, 60(5), 1178–1204. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12918

- Kaufman, A., & Englander, E. (2005). A team production model of corporate governance. Academy of Management Executive, 19(3), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.2005.18733212

- Kaufman, A., & Englander, E. (2011). Behavioral economics, federalism and the triumph of stakeholder theory. Journal of Business Ethics, 102(3), 421–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0822-0

- Kindström, D., Carlborg, P., & Nord, T. (2022). Challenges for growing SMEs: A managerial perspective. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2082456

- Klag, M., & Langley, A. (2013). Approaching the conceptual leap in qualitative research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 15(2), 149–16. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2012.00349.x

- Kroll, M., Walters, B. A., & Wright, P. (2008). Board vigilance, director experience, and corporate outcomes. Strategic Management Journal, 29(4), 363–382. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.649

- Kurtmollaiev, S. (2020). Dynamic capabilities and where to find them. Journal of Management Inquiry, 29(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1177/1056492617730126

- Leuz, C., Lins, K. V., & Warnock, F. E. (2009). Do foreigners invest less in poorly governed firms? Review of Financial Studies, 23(3), 3245–3285. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhn089.ra

- Linder, S., & Foss, N. J. (2018). Microfoundations of organizational goals: A review and new directions for future research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(S1), S39–S62. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12154

- Lippi, A., Torelli, R., & Caccialanza, A. (2023). Relationship between governance diversity and company growth: Evidence from the FT 1000 Europe’s fastest growing companies. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 31(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.2591

- London, M., Polzer, J. T., & Omoregie, H. (2005). Group learning: A multi-level model integrating interpersonal congruence, transactive memory and feedback processes. Human Resource Development Review, 4(2), 114–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1534484305275767

- Macpherson, A. (2005). Learning how to grow: Resolving the crisis of knowing. Technovation, 25(10), 1129–1140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2004.04.002

- Monks, R. A. G., & Minow, N. (2011). Corporate governance (5th ed.). John Wiley & Sons.

- Nonaka, I. (1994). A dynamic theory of organizational knowledge creation. Organization Science, 5(1), 14–37. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.5.1.14

- Nonaka, I., & Toyama, R. (2003). The knowledge-creating theory revisited: Knowledge creation as a synthesizing process. Knowledge Management Research & Practice, 1(1), 2–10. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.kmrp.8500001

- Palmié, M., Rüegger, S., & Parida, V. (2023). Microfoundations in the strategic management of technology and innovation: Definitions, systematic literature review, integrative framework, and research agenda. Journal of Business Research, 154, 113351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2022.113351

- Patton, M. Q. (1990). Qualitative evaluation and research methods. SAGE Publications.

- Penrose, E. T. (1959). The theory of the growth of the firm (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Pfeffer, J., & Salancik, G. R. (1978). The external control of organizations: A resource dependence perspective. Harper and Row.

- Pratt, M. G. (2008). Fitting oval pegs into round holes: Tensions in evaluating and publishing qualitative research in top-tier North American journals. Organizational Research Methods, 11(3), 481–509. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428107303349

- Pratt, M. G. (2009). From the editors: For the lack of a boilerplate: Tips on writing up (and reviewing) qualitative research. Academy of Management Journal, 52(5), 856–862. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.44632557

- Raelin, J. A. (2018). What are you afraid of: Collective leadership and its learning implications. Management Learning, 49(1), 59–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507617729974

- Ramaswamy, V., Ueng, C. J., & Carl, L. (2008). Corporate governance characteristics of growth companies: An empirical study. Academy of Strategic Management Journal, 7(1), 21–33.

- Rasmussen, C. C., Ladegård, G., & Korhonen-Sande, S. (2018). Growth intentions and board composition in high-growth firms. Journal of Small Business Management, 56(4), 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1111/jsbm.12307

- Rigg, C., Coughlan, P., O´leary, D., & Coghlan, D. (2021). A practice perspective on knowledge, learning and innovation – insights from an EU network of small food producers. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 33(7–8), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2021.1877832

- Sadler-Smith, E., Hampson, Y., Chaston, I., & Badger, B. (2003). Managerial behavior, entrepreneurial style, and small firm performance. Journal of Small Business Management, 41(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-627X.00066

- Schønning, A., Walther, A., Machold, S., & Huse, M. (2019). The effects of directors exploratory, transformative and exploitative learning on boards´ strategic involvement: An absorptive capacity perspective. European Management Review, 16(3), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1111/emre.12186

- Sheehan, M., Garavan, T. N., & Morley, M. J. (2023). The microfoundations of dynamic capabilities for incremental and radical innovation in knowledge-intensive businesses. British Journal of Management, 34(1), 220–240. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12582

- Sievinen, H. M., Ikäheimonen, T., & Pihkala, T. (2022). The role of dyadic interactions between CEOs, chairs and owners in family firm governance. Journal of Management & Governance, 26(1), 223–253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-020-09561-7

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Tricker, B. (2019). Corporate governance: Principles, policies, and practices. Oxford University Press.

- von Krogh, G., Nonaka, I., & Rechsteiner, L. (2012). Leadership in organizational knowledge creation: A review and framework. Journal of Management Studies, 49(1), 240–276. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2010.00978.x

- Yin, R. K. (2003). Case study research. SAGE Publications.

- Yin, R. K. (2015). Qualitative research from start to finish. Guilford Publication.

- Zietsma, C., Winn, M., Branzei, O., & Vertinsky, I. (2002). The war of the woods: Facilitators and impediments of organizational learning processes. British Journal of Management, 13(S2), 61–74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.13.s2.6