ABSTRACT

Organizational ambidexterity evolves as an aggregated capability based on individuals’ behaviors within a venture. But what happens in founding teams when the founders collaborate? This study aims to decipher individual exploitations/explorations’ interpersonal connection to understand how the social interaction between founders translates into emergent team processes that either enable or hinder the team’s capacity to become ambidextrous. The empirical setting is an exploratory case study of 15 teams, using data from 39 interviews and 12 observations. Our findings indicate that certain behaviors linked to ambidexterity reinforce the co-founders’ behavior. The other founders often mimic the initial exploitation behavior. Nevertheless, individual behavior can also cause co-founders to exhibit switching responses, especially when responding to initial exploration behavior. These observed stimulation response patterns revealed opportunities and threats for the founding team. Our study contributes to the literature on ambidexterity, particularly to the connection of team and individual levels of analysis.

Introduction

In order to succeed in dynamic markets, organizations must exploit their current knowledge and explore new business opportunities (Gupta et al., Citation2006; March, Citation1991). Scholars argue that balancing exploitation and exploration is vital for fostering short-term competitive advantages and ensuring long-term business sustainability (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Junni et al., Citation2013). This balancing act is particularly crucial yet challenging for smaller organizations like start-ups (Mu et al., Citation2020).

Startups face unique challenges and work differently than larger organizations do (Burton et al., Citation2019; Gasda & Fueglistaller, Citation2016; Prajogo & McDermott, Citation2014). While both small and large organizations face pressures to balance exploration and exploitation, their capacities for achieving desired ambidextrous outcomes are markedly different (van Neerijnen et al., Citation2023). Larger firms can separate two opposing elements’ alignment structurally (Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996), or can allocate alignments to multiple individuals within a business unit (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004). Small organizations, however, usually comprise fewer individuals and therefore have a narrower range of knowledge, which makes achieving specialization within the organization more difficult (Fourné et al., Citation2019; Gupta et al., Citation2006). Start-ups are, moreover, usually comprised of small teams (Knight et al., Citation2020), which the founders’ judgment, rather than formal strategic planning, guides (Patzelt et al., Citation2021).

Literature on ambidexterity in start-ups has primarily concentrated on the individuals responsible for decision-making—the founders—and their behaviors (Klonek et al., Citation2021). Founders are the critical architects of the firm’s overarching strategies (Bamford et al., Citation2006; Gottschalck et al., Citation2021) and an extreme example of ambidexterity (Brem, Citation2017) in terms of the cognitive task of handling the paradox between exploration and exploitation (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). Since founders usually bear the full responsibility for both exploitative and explorative tasks, often without supportive resources, they repeatedly need to decide make decisions about their time allocation. Balancing these conflicting objectives, often under tight time and resource limits (Brem, Citation2017), makes handling the tensions between exploration and exploitation, both cognitively (Smith & Tushman, Citation2005) and emotionally (Miron-Spektor et al., Citation2018), more challenging. A growing literature stream has opened up perspectives on how individual founders could merge exploitation and exploration’s synergistic values (Klonek et al., Citation2021; Mu et al., Citation2020). However, there are still open questions about the ambidextrous dynamics between multiple founders and the cross-level effects within founding teams, since the complexities and interactions within these teams remain underexplored. From the ambidextrous leadership literature, we understand that the behavior of leaders can support their team members in adopting ambidextrous behaviors (Zhang et al., Citation2022). However, the mutual influence among founders at a horizontal level remains insufficiently explored. This knowledge gap is critical because the founding team shapes a firm’s strategies, structures, actions, and performance. This team is therefore the most essential collective of individuals for predicting start-up exploration and exploitation behaviors (Beckman, Citation2006). Consequently, the founding team’s shared leadership is an “important locus for resolving the tensions between exploratory and exploitative entrepreneurial processes” (Mihalache et al., Citation2014, p. 141).

Start-ups characterized by their need for flexibility, responsiveness, and, usually, a smaller size without formalized structures, coordinate primarily via their continuous daily interactions, rather than via top-down planning (Jones & Schou, Citation2023). Successful coordination in smaller organizations requires a reflexive climate. Through this sociocognitive integration mechanism, organizational members are encouraged to regularly reevaluate strategies, goals, and processes, thereby enhancing greater cooperation and coordination among team members, which ultimately helps the teams realize ambidextrous outcomes (van Neerijnen et al., Citation2023). Building on Junni et al.’s (Citation2015) assertion and social learning principles, we posit that social relationships play a pivotal role in shaping founding teams’ ambidexterity, as during social interaction founders guide and influence one another with their behavior. Consequently, our research delves into the complex web of social interactions among founders, aiming to understand not just the direct behavioral influences founders have on one another, but also how these individual actions ripple through the team, influencing its overall ability to generate ambidextrous outcomes. To address this puzzle, we ask: how does one founder’s individual exploitation/exploration behavior stimulate another founder’s behavior, and how does this affect team-level ambidexterity? By answering the research question, we aim to reveal how the interpersonal process between two founders becomes emerging team processes that either help or hinder the founding teams from becoming ambidextrous. Grounded in the understanding that emergent phenomena in a team manifest themselves from the bottom-up of the individuals’ processes and interactions (Kozlowski & Chao, Citation2018; Kozlowski et al., Citation2013), we examine ambidexterity as a multilevel social learning phenomenon emerging from the founding team members’ interactions and behaviors. We do so by conducting a comparative case study of the 39 founders of 15 founding teams from creative industries, relying on interviews, observations, and archival data to gain rich insights into their social interactions and collaboration. Our research design allowed us to observe individual behavior and its influence on others. We furthermore gathered narratives from diverse perspectives on whether the social interaction harmed or helped the team become ambidextrous.

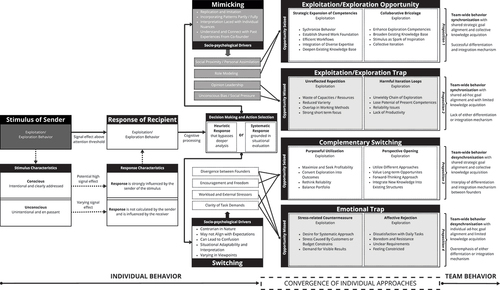

We found that a founder’s various exploration/exploitation activities trigger another founder to respond. Mimicking and switching were the key response mechanisms that we observed. We therefore conceptualize mimicking as a reciprocal process in which one founder replicates another’s behavior. When founders mimic each other, this could initiate team-wide processes, including the formation of a shared mental model or visions and goals’ alignment. These internal dynamics promote various inputs’ integration and coordination into synchronized collective efforts, thereby expanding the team’s exploitation competencies or enhancing exploration by broadening the existing knowledge base. Conversely, these processes could lead to inefficiencies through overlapping working methods and unwieldy exploration chains. Switching, however, is a contrarian response to the initial stimulus. Switching refers to an adaptive response where a founder dynamically alters observed strategies or behaviors in relation to the initial stimulus. For instance, when Founder 1 proposes to explore a new, experimental game engine with advanced features (exploration), a switching response is Founder 2’s alert of the steep learning curve and potential bugs, resulting in the use of the current, stable engine to avoid potential project delays (exploitation). Switching is characterized either by rejecting or by complementing the initial stimulus. Individual switching behaviors could enable complementary team-wide processes, such as cultivating diverse perspectives and approaches directed at unified objectives. These processes foster embracing various skills, effective communication, and robust decision making in order to align desynchronized actions with collective efforts. Accordingly, teams are better equipped to convert exploration into reliable outcomes or to integrate new knowledge into existing structures. However, individual switching triggered by work-related stress or internal resistance could fuel adverse processes leading to emotional traps. These response mechanisms and their consequences co-occurred with various sociopsychological drivers and team characteristics, which either helped teams leverage opportunities by mimicking or switching or impeded their collaborative efforts.

Our core contribution is developing a multilevel theoretical framework that depicts the evolution of the social interactions between founders as moving toward emerging ambidexterity—a team-level phenomenon. Our paper contributes to a deeper understanding of team ambidexterity in entrepreneurial settings (Klonek et al., Citation2021). Further, Mom, van Neerijnen et al. (Citation2015) highlighted goal alignment’s potential detrimental consequences for individual exploration in R&D teams, while our analysis of founding teams contributes a distinct perspective regarding goal alignment actually facilitating exploration activities, rather than prompting teams to undertake exploitation. Moreover, we add to the literature on cognitive processes that influence ambidexterity by uncovering how mimicking and switching help teams share successful integration and differentiation’s pressure between different individuals (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). In addition, we expand the literature on supportive or directive environments’ and leadership styles’ impact (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2022) on ambidexterity within founding teams. We do so by introducing a mixed participatory approach. Finally, we clarify exploitation’s self-reinforcing dynamics and switching resistance’s challenges (Bidmon & Boe-Lillegraven, Citation2020; March, Citation1991) by demonstrating how collaborative teamwork helps individuals escape repetitive exploitation cycles.

Conceptual background

Navigating dual paths: Individual ambidexterity

Individuals who behave ambidextrously contribute more to organizational success than those who do not (Bledow et al., Citation2009). Further, entrepreneurs’ ambidextrous behavior sustains their whole organization’s ambidexterity (Volery et al., Citation2015). This leads to the conclusion that ambidexterity arises from the aggregated capabilities of individuals’ ambidextrous behaviors, and that ambidextrous organizations therefore need ambidextrous individuals (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004; Raisch et al., Citation2009). To date numerous studies have indeed demonstrated that individual-level ambidexterity not only enhances personal performance (Mom, Fourné et al., Citation2015), but that exploration and exploitation’s successful blending also fosters ambidexterity, which in turn produces synergies for entire organizations (Schnellbächer et al., Citation2019; Zhang et al., Citation2022) or entrepreneurial teams (Gasda & Fueglistaller, Citation2016).

March (Citation1991) initially introduced exploration and exploitation as two forms of organizational learning. Exploration involves discovery, experimentation, and the pursuit of alternatives, while exploitation focuses on refining and executing existing knowledge and skills. Recent research has expanded the concept to include the individual level, defining individual ambidexterity as the degree to which individuals value and engage in both explorative and exploitative activities at their work (Mom et al., Citation2009; Zhang et al., Citation2022). As such, highly ambidextrous individuals merge their efficiency-oriented efforts with their pursuit of new skills (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004). For example, highly ambidextrous designers might utilize their existing skills to meet customer needs (exploitation), while simultaneously investigating AI-based methodologies to keep pace with emerging trends (exploration).

Nevertheless, the dual pursuit of exploration and exploitation inflicts distinct cognitive and emotional demands on individuals, leading to inherent tensions when they pursue both (Bidmon & Boe-Lillegraven, Citation2020; Good & Michel, Citation2013). The capacity to navigate tensions and competing demands differs noticeably among individuals. In order to understand this variation, the literature emphasizes the central role that cognition plays in managing tensions, in which processes, such as information acquisition, processing, and decision making, are critical. Moreover, on the individual level, studies have recognized that a paradoxical mindset—a cognitive framing in which tensions are acknowledged and accepted as “persistent and unsolvable puzzles” (Smith & Lewis, Citation2011, p. 385)—is crucial to manage tensions effectively (Miron-Spektor et al., Citation2018). Consequently, individuals can navigate contradictions successfully by embracing them, rather than avoiding them. They can do so by adopting a paradoxical frame, which involves differentiating between existing strategies cognitively and then integrating them, rather than choosing one over the other (Smith & Tushman, Citation2005; Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). Notably, managing these tensions is not an exclusively cognitive task; it also entails emotional management (Miron-Spektor et al., Citation2018). While tensions might trigger anxiety (Lewis, Citation2000), they could also stimulate curiosity and engagement, despite the potential stress that they induce (Bidmon & Boe-Lillegraven, Citation2020).

Mu et al. (Citation2020) summarized that individual predispositions and preferences, such as cognitive flexibility, passion for work, and time management, play a significant role in how individuals handle the tensions between exploration and exploitation. In addition, factors such as managing work stress (Zhang et al., Citation2019), personal coordination (Mom et al., Citation2009), and prior work experience (Bonesso et al., Citation2014) shape one’s capacity for ambidexterity. For instance, a founder with prior experience in 3D-mapping software could leverage that knowledge to identify opportunities and integrate them into new settings.

However, individual ambidexterity does not emerge in a vacuum, and is not solely dependent on individual predispositions and cognition. Instead, a complex interplay of individual predispositions and contextual factors shape it (Raisch et al., Citation2009). Some individuals can better balance exploration and exploitation independently, while others require guidance (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). Social dynamics, such as group cooperation (Jansen et al., Citation2016) and cross-functional coordination (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019), largely influence individual ambidextrous behavior’s collective alignment. The literature offers two contrasting perspectives on fostering ambidexterity within a social context. One perspective advocates a supportive environment in which individuals can express themselves freely, because they have the autonomy to decide when and how to allocate their time between the two activities (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). This approach values individual agency and flexibility. The other perspective is more directive, emphasizing leadership behaviors’ and top-down instructions’ role in the fine-tuned, divergent activities that support the ambidextrous process (Zhang et al., Citation2022). This approach presumes that structured guidance ensures alignment with the organizational goals, despite the risk of the control over their work behavior leaving individuals feeling overwhelmed and stressed (Tempelaar & Rosenkranz, Citation2019). Such studies share a key similarity regarding highlighting social context’s role in helping individuals manage exploration and exploitation’s conflicting needs. However, the stark contrast between these two perspectives, and the previous research’s primarily quantitative nature leaves a significant gap in our understanding of the dynamics of how these contrasting social environments influence ambidexterity’s emergence, particularly in specialized contexts, such as founding teams or nonhierarchical structures.

Making the path together: Team ambidexterity

In dynamic environments, teams play a pivotal role in enhancing a firm’s agility, flexibility, and adaptability; furthermore, teamwork transcends individual contributions’ mere combination (Kozlowski & Ilgen, Citation2006). Similarly, team ambidexterity is not just the sum of individual founders’ behaviors, but embodies a deeper collective synergy. Building on March’s (Citation1991) learning-based concept, studies have defined team ambidexterity as a team’s collective ability to simultaneously engage in exploration and exploitation learning (Jansen et al., Citation2016). The latter reflects how the entire team can effectively emphasize and engage in both exploration and exploitation over time (Zhang et al., Citation2022). For example, in an architectural founding team that excels at exploration and exploitation, both single individuals and the whole team integrate sustainable technologies innovatively into their work (exploration), while simultaneously capitalizing on their well-established and refined design process (exploitation), thereby developing knowledge of the progressive elements and of the lucrative market positioning. Despite research emphasizing the positive outcomes of team ambidexterity, such as improved performance, maintaining competitiveness, and adaptiveness (see Jansen et al., Citation2016; Liu & Leitner, Citation2012; Zhang et al., Citation2022), the nuances of the processes of achieving ambidexterity within a team still need to be fully understood (Jansen et al., Citation2016).

While exploration and exploitation require distinct knowledge, teams need to coordinate the challenging processes of differentiating in order to embrace various positions and to subsequently allow their team members to integrate multiple approaches in order to achieve ambidextrous outcomes (Li et al., Citation2018). We describe such team-level processes as multilevel phenomena emerging from the ongoing interactions between the team members, and adapting to their work environment’s evolving demands over time (Kozlowski & Chao, Citation2018). Understanding the multilevel phenomena, process evolution, and emergence requires an understanding of all the input—process—output elements (Simsek, Citation2009).

Inputs refer to antecedents that affect ambidexterity’s development and presence within a founding team. The founding team’s composition, particularly its diversity, is an important input factor (Beckman, Citation2006; Li et al., Citation2018). A diverse team whose members possess very distinct knowledge enhances the team’s capacity to differentiate between various knowledge items, which is essential for ambidexterity (Dean, Citation2021). However, diversity alone is not sufficient; integration processes are crucial for realizing the latent potential that the inputs provide (Lubatkin et al., Citation2006).

Interaction processes between team members are essential for forming team mental models, which guide and coordinate the team (Wang et al., Citation2014). Such interactions can foster dense social linkages, bolstering the coordination and the mutual goals (Morgeson et al., Citation2009), and thereby encouraging ambidextrous thinking and action (Andriopoulos & Lewis, Citation2009). Further analyses of interaction processes revealed that team cohesion and collective efficacy beliefs affect team members’ ability to pursue distinct exploration and exploitation learning activities (Jansen et al., Citation2016). Cohesion facilitates integrating individual capacities into ambidextrous behaviors by enhancing the information flow, social ties, adding resources, and creating identity (Kang & Snell, Citation2009; Li & Huang, Citation2013). A cohesive team provides a secure platform for expressing divergent opinions and promotes constructive conflict resolution (Wong, Citation2004). During teamwork, individuals can influence others indirectly by means of role-modeling, signaling, motivating, and encouraging observational learning (Gasda & Fueglistaller, Citation2016; Zhang et al., Citation2022). When interacting, individuals observe how others embrace their relevant opposing demands and learn from their patterns how to manage these tensions (Miron-Spektor et al., Citation2018). It might, for example, be inspiring and educational for a founder to watch a co-founder fulfilling multiple roles and switching between short-term and long-term orientations, while focusing on clearly set goals (exploitation) and using innovative ideas (exploration) to fulfill them. Social learning principles indicate that the behaviors that team leaders display could “trickle down” to their team members (Liu et al., Citation2018). But how does this happen in founding teams with no formal leader? The horizontal social learning process in respect of team ambidexterity’s emergence is as yet under-researched. To date, we know that, within a team, trust cultivates an environment in which individuals feel comfortable sharing information, experimenting, and contributing diverse learning experiences (Jansen et al., Citation2016). Contingent on the team’s trust and closeness (Mom, van Neerijnen et al., Citation2015), this knowledge is then shared and utilized within the team, thereby influencing the team knowledge’s flow and utilization (Birkinshaw & Gibson, Citation2004; Subramaniam & Youndt, Citation2005). The latter catalyzes new knowledge’s creation and diversifies the learning processes (Mom et al., Citation2007).

Social interactions within a team extend beyond mere exchanges; they are pivotal opportunities for the team to learn to explore novel ideas, exploit existing knowledge, and align individual goals with those of the collective. Integrative processes, such as the regulatory function and reflexivity, are central for the team to learn the mentioned actions. In turn, these sociocognitive mechanisms shape and recalibrate the team processes to deal with changing demands (Li et al., Citation2018). Reflexivity enables teams to critically examine and reassess their strategies, goals, and processes, which allows them to reconcile conflicting demands and integrate contradictory perspectives in order to achieve a shared mental model or a homogenous knowledge base (Li et al., Citation2018; Morgeson et al., Citation2009; van Neerijnen et al., Citation2022).

Team leadership behavior is conspicuous as another significant integration process influencing team learning and mediating team-level ambidexterity. Individuals could even guide others’ ambidextrous behavior directly by means of formal and informal communication or explicit task objectives, goal sharing, work division, semi-isolated subgroups, and task partitioning (Fang et al., Citation2010; Jansen et al., Citation2016; Kassotaki et al., Citation2019; Kauppila & Tempelaar, Citation2016). Effective team leadership behavior could also influence and encourage team members’ exploration and exploitation behaviors (Smith & Tushman, Citation2005; Zhang et al., Citation2022). Although studies indicate that individual behaviors could teach and guide others, there is a gap in understanding how exploration and exploitation behavior stimulate others’ behaviors and how these ripple effects also affect the team level. This knowledge gap is especially pronounced in founding teams comprising multiple equal founders without a designated leader. Consequently, the dynamics of leadership behavior’s influence on team ambidexterity remain under-explored.

Although it is known that team processes allow teams to use their intrinsic adaptive, dynamic, and integrative potential (Kozlowski & Ilgen, Citation2006), we lack an understanding of this potential’s evolution from lower-level dyadic interactions to collective team-level ambidexterity. Despite previous research, we lack a thorough understanding of how, and under what conditions, teams might achieve ambidexterity (Jansen et al., Citation2016). This has led to a recent call for a qualitative approach to untangle team and individual ambidexterity’s characteristics and processes (Zhang et al., Citation2022).

We stress the significance of observing individual influences and how these ripple effects influence team dynamics. While some ambidexterity mechanisms at the team level mirror those at the firm level, teams display unique dynamics not confined to these. Notably, characteristics like adaptability needs, deep-seated peer relationships, power distribution, and the lack of formal leadership and hierarchy as in small founding teams, are key to exploring the social processes, which are essential for team ambidexterity. We therefore endeavor to examine phenomena that emerge in teams and manifest themselves from the bottom-up as psychological characteristics, processes, and interactions between individuals (Kozlowski et al., Citation2013). We specifically focus on exploring team processes, the interrelations between teams’ interaction dynamics, behavior stimulation, leadership behaviors, and integrative dynamics (Dean, Citation2022). In addition, we aim to explore how, within a founding team, these processes influence exploration and exploitation behaviors’ collective alignment, balancing, and intensity.

Method

Research design

Since we focus on the “how” aspects, and due to the research question’s limited theories and evidence, we use a multicase theory-building approach (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). Qualitative methods are particularly valuable in respect of addressing entrepreneurial processes, as well as the complex and overlapping social dynamics in this context (Hlady-Rispal et al., Citation2021). Since entrepreneurial processes and social interactions are complex, we aim to construct a robust, parsimonious, and generalizable theory by using a multicase replication logic (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). We conducted iterative, inductive analyses after choosing and collecting theoretically relevant cases based on prescribed methods for a comparative case study (Eisenhardt, Citation1989). This method fostered a combination of depth and breadth, thereby enabling immersion within multiple teams.

As an essential part of qualitative research, purposeful sampling allows knowledge to be precisely extracted from information-rich cases related to the phenomenon of interest (Palinkas et al., Citation2015). We observed entrepreneurial teams in creative industries in Germany. The creative industries’ founding teams are well-suited to allow ambidexterity to be explored due to their inherent paradoxes, such as creative products’ commercialization and self-realization under market demands. Both these paradoxes require a combination of divergent and convergent thinking in order to exploit existing products and explore new solutions (Koch et al., Citation2023; Parmentier & Picq, Citation2016; Schulte-Holthaus & Kuckertz, Citation2020). For example, although musicians might wish to create innovative, genre-defying music, they also need to create music that appeals to a broad audience in order to achieve commercial success.

The first author scanned an internal database of more than 1,000 listed start-ups from the Rhineland-Palatinate’s creative industries to choose a initial sample. The Rhineland-Palatinate was chosen for its balanced creative submarkets and rich creative history. Strong ties to local incubators, universities, and cultural institutions enhanced our sample response and overview. During the sampling process, more German start-ups were added to represent potentially valuable cases. We subsequently chose the sample, using the following criteria: First, we excluded larger teams (>5 members) with only one founder. Since we endeavored to uncover reciprocal exploration and exploitation behavioral exchanges between founders, we had to identify their direct personal relationships to find distinct patterns of social interaction. Further, small teams with a flat hierarchy allowed us to directly observe behaviors’ influence between individuals. A strong hierarchy would have limited statements about behaviors’ influence since authoritarian power could have a strong influence. In extreme cases, we would no longer refer to ambidextrous influence but to an ambidextrous directive.

Subsequently, we used social media, homepages, or field visits to obtain an overview of the product/service offered. We selected them, in such a way that we not only paid attention to start-ups offering an actively marketed product/service, such as a rentable, augmented reality installation for corporate events, but also museums. This action helped counter the preconception that creative professionals are far more inclined to undertake exploration. Similar to Andriopoulos and Lewis (Citation2009), we only chose teams that had demonstrated that they were specialized in activities requiring both explorative and exploitative knowledge. For example, one case concerned a production company that had produced an award-winning documentary film. This highly artistic project, had garnered many film festival awards. The founders had invested considerable time and resources in this project, not primarily for monetary gain, but rather to gain prestige and recognition in their field. Simultaneously, in order to fund more such ambitious and creative projects, the company engaged in commercial endeavors, such as shooting advertisements. This dual approach allowed them to maintain their artistic integrity, while ensuring the financial sustainability required to continue producing pioneering work.

Our sampling resulted in 19 start-ups participating. Finally, we excluded four of these that were too immature and where we might not have had the opportunity to talk to all their founders. For our final sample of 15 start-ups, we selected teams with a similar structure, but sufficient variance in their other characteristics (main product/service, target audience/customer, time of operation, and subsector) to meet the replication and generalizability logic. summarizes our cases and data-collection activities.

Table 1. Overview of cases.

Data collection

First, we conducted a total of 39 semi-structured interviews obtained from 15 cases. The average interview duration was 44 min. In 14 cases, we talked to every person on the team. All the interviews were conducted and recorded via a video communication platform. The interview guideline was designed with individual exploration and exploitation behaviors in mind, but, as Andriopoulos and Lewis (Citation2009) recommended, did not include dilemmas and tensions terms. We avoided leading and speculative questions to ensure the accuracy. We structured the interviews to gather specific information by using nondirective questions focused on previous events. The interviews first included general questions about the person, the company, and the team, thereafter proceeding with questions about individual work behavior, typical work days, and descriptions of situational team moments. Other aspects that we included were about personal factors, such as the person’s passion and discipline, as well as contextual factors like the behavioral integration, team heterogeneity, team performance, team effectiveness, the overall performance, and future challenges. Specifically, we asked the informants to describe significant events that they had experienced. The aim was to encourage them to think freely in order to allow us to gain as detailed an insight as possible into the teams’ activities. Relying on interview questions that hark back to past situations could present a challenge, as these responses might be tinged with perceptual biases. Consequently, the tracking of reciprocal exchanges within personal relationships might not always yield reliable outcomes. A robust and relevant starting point is crucial to accurately illustrate cognitions, emotions, and behaviors emergence and evolution.

Consequently, we employed the Critical Incident Technique (CIT), which focuses on significant events within personal relationships that impact a situation’s outcome conspicuously (Chell, Citation1998). We stimulated the participants to describe situations as systematically as possible. The focus was on “critical incidents,” that is, those events during which the founders remembered their contact with their co-founders being particularly pivotal. In our in-depth interviews’ initial stage, we questioned the participants about specific critical incidents. The interviewees, for example, mentioned conflict resolution during critical times, productive customer communication, and achieving or missing key milestones during a project. Subsequent questions delved into the events’ details and the extent of the involved individuals’ reactions. Our interview guide highlighted core elements, such as the context, place, time, actors involved, actions taken, and the behaviors’ effectiveness. Our approach, centered on actual behaviors in real-life scenarios rather than on generalized perceptions, revealed significant insights into behavioral reactions and their ensuing implications. The CIT sharpened our focus on distinct events, the mitigating subjectivity and bias, and enabled a more precise understanding of relationship dynamics (Chell, Citation1998). In addition, interviewing all of the relevant founders captured their narratives from multiple perspectives. This multifaceted approach empowered us to craft a more authentic, comprehensive view of the founding teams’ the relationship dynamics and their evolution over time.

Second, to enhance our understanding of the interactions even more, we incorporated additional field observations. The first author visited the start-ups, resulting in 12 observations (over 31 hours) with sequential video data and rich field notes. The observations (mini-workshops, briefings, and group discussions) complemented the interview process and allowed us to witness how founders interact and solve problems on a daily basis, thereby helping us form an initial understanding of the cases and the map patterns of behavior influences and collaboration (Watson, Citation2011). For example, we directly observed the others’ reactions when one founder advocated creating a formal hiring and onboarding process for their start-up’s new employees. Despite the team’s immediate pushback due to these being perceived as unnecessary formalities for a small company, throughout the discussion, the founder kept emphasizing the importance of maintaining high-quality work with a standardized HR strategy. After a final debate, the other founders also agreed to allocate time and resources to developing this process.

Third, we used archival sources, such as social media posts, exposés, portfolio homepages, internal documents, work samples, and reports to complement our database.

Data analysis

We followed a four-stage process that Glaser and Strauss (Citation1967), Miles and Huberman (Citation1994), and Miles et al. (Citation2020) proposed. In keeping with Gioia et al. (Citation2013), we used a systematic approach to new concept development and grounded theory articulation.

In our initial within-case analysis (Eisenhardt, Citation2021), we began by synthesizing the interview transcripts and the field notes. We used the field notes and video data that we captured during the observations to retrieve fine-grained information on how each founding team interacted and coordinated its activities. The interview data gave us specific insights into detailed situational descriptions from all of the involved founders’ perspective. Having built an understanding of each case, we undertook a cross-case analysis (Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007). We developed tentative constructs from individual cases (for example, experiments, and focus), comparing them across the cases. By cycling between emergent theory and the data, we clarified the constructs and related measures, as well as strengthening our logical arguments. When our theoretical understandings crystallized, we compared them with those in prior research (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016). Our explanatory framework was finalized when the data, measures, constructs, and theory agreed strongly.

Stage 1 identifying initial, broad categories within each case

We first used our primary data to compile separate case studies of each team. On examining all the interview transcripts, we identified patterns and variance in individual ambidextrous behaviors’ descriptions by using language indicators such as routine, systematic processes, repetition, refinement, improvement, experience, experimentation, iteration, creative freedom, and variation. Our conceptual coding involved using vivo codes (that is, first-order concepts comprised of language that the informants used) when possible or a descriptive phrase (Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990). These first-order concepts offered general insights into the individual ambidextrous behaviors that the informants described. The results were compared for consistency with the observation data. We identified references to individual ambidextrous behavior across all the cases in the 39 interviews.

Stage 2a linking related concepts within each case

During stage two, we explored the links between the first-order concepts and among them, which allowed us to group them into second-order themes. As part of the inductive process, we allowed concepts and relationships to emerge from the data, instead of using prior hypotheses to guide them (Miles et al., Citation2020; Strauss & Corbin, Citation1990), which resulted in case descriptions for all 15 cases. The teams were allowed to participate in a follow-up session to discuss their case descriptions, after which we incorporated their feedback.

Stage 2b looking for behavioral stimulations of individual ambidextrous behavior within each case

In part B of the second stage, we examined the second-order themes that appeared in combination with the team members’ active or passive influences. In order to do so, we examined the second-order themes by means of language indicators in order to identify their influence (for example, copied, influenced, role model, adopted, and established) or to examine whether the context indicated changing behavior due to a specific team member’s stimulation. Here, the observation data was used, because the video data captured ad hoc stimulations especially well. Across all the cases, we identified references to individual ambidextrous behaviors that influenced other team members in 33 of the 39 interviews.

Stage 3 conducting cross-case comparisons

Using standard cross-case analysis techniques (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Miles & Huberman, Citation1994), we looked for similar concepts and relationships across the cases, comparing the categories produced in stage 2a when they appeared in combination with behavioral stimulation as captured in stage 2b. We gathered similar patterns into aggregated dimensions that served as the basis of our framework. For example, regarding the influence of an individual’s clear goal-setting and well-defined processes, most informants mentioned that their team members spend more time on handling customer concerns meticulously and professionally, which resulted in more reliable implementation. Consequently, one individual’s exploitation behavior reinforces the other team members’ exploitation behavior.

Stage 4 building a framework

In order to transition from the data structure’s static representation to a dynamic picture, we, following Gioia et al. (Citation2013) suggestion, constructed an inductive process model firmly rooted in the data and theory. Only robust findings were analyzed to allow a concise set of constructs to converge.

depicts the data structure of our identified individual ambidextrous behaviors and their respective response pattern.

Findings

Our research delved into the intricacies of how the social interaction between founders facilitates or impedes ambidextrous practices’ adoption. The aim was to decipher the connections between founders’ interpersonal exploitation/exploration behaviors and to understand how the bilateral interaction translates into emergent team behaviors—either enabling or hindering the team’s capacity to become ambidextrous. Our observations revealed differing team dynamics: some teams thrived on the social interaction, while others floundered due to the conflicting interrelations.

Central to our understanding of this dynamic is exploring how a founder’s behavior stimulates responses from their counterparts. We found that a founder’s various behaviors, such as active engagement, intervention, identifying growth opportunities, commitment to a shared vision, motivation, and assistance, served as a stimulus for other team members. Based on the situation descriptions, we assume that, for a behavior to be perceived as a stimulus and for the receiver to process it as a response, its signaling effect needs to be above a certain attention threshold in order to trigger a response. Moreover, such stimuli exhibited two major characteristics. Primarily, the founder (the sender) communicated something consciously with certain expectations in respect of the other founder (the recipient). Observation data revealed that consciously sent stimuli had a high signal effect, which the recipients rarely ignored. The sender’s strategic evaluation of the situation influenced the conscious stimuli, which were primarily anchored in the sender’s personal agenda. This, in turn, channeled the recipient’s response within a predictable spectrum, thereby highlighting the sender’s significant role in molding the response. Conversely, the sender conveyed some stimuli unconsciously. Such stimuli had no explicit expectations in respect of the recipient, which gave the recipient more scope to shape the response. Unconscious stimuli did not involve the recipient being directly petitioned, which is why their signaling effect varied, depending on the recipient’s perception. Consequently, unconscious stimuli remained unnoticed more often than conscious stimuli were. Moreover, like a stimulus, the receiver could be conscious or unconscious of a response; we describe this in more detail in the relevant subchapter on response patterns.

We next focus on the founders’ response when two key mechanisms, mimicking and switching, emerged within the bilateral relationships. elaborates on these mechanisms, illustrating the observed exploration/exploitation behaviors and associated response patterns. Different concomitants seemed to drive mimicking and switching, thereby shaping the social interaction’s dynamic and consequence for the founding team. We constructed a framework () to probe the conditions under which mimicking and switching occur and their potential consequences for the team, as well as to dissect the above interpersonal dynamics further.

Exploring the dynamics of behavioral mimicking

We define mimicking as a response wherein a founder reproduces the behaviors of the other, resulting in specific actions’ adoption and replication. While mimicking resulted in the recipient incorporating the sender’s patterns, either partially or fully, it did not imply exact duplication. Instead, it denoted an interpretation infused with individual nuances and variations that shape a founder’s approach. In the interplay between exploration and exploitation, mimicry could involve the receivers switching from their original action to synchronize their behaviors with the sender’s action, for example, switching a transaction from exploitation to mimicking exploration. Best described as learning by observing, mimicry appeared to foster mutual understanding and establish a bond between founders and co-founders, which enabled founders to learn from their co-founders’ past experiences, thereby leading to personal growth through observation and imitation. Mimicking dynamics were particularly evident in exploitation. The following is an example of mimicking exploitation:

This detailed planning and preparation down to the last detail. Yes, she’s a bit more definitive than I am, and that’s actually great, because sometimes I end up being a bit like: ‘oh come on, this fits now.’ But because of her, I invest more time because, in the end, it is so important. Yes, the devil is in the details. (F1-THETA)

Conscious mimicry usually happened when an individual decided to deliberately emulate someone else’s behavior for a specific purpose, like learning a new skill or building rapport with another person. In contrast, subconscious mimicry usually took place without the individual being aware of it. It is an automatic response deeply ingrained in social wiring, like fulfilling social expectations or handling group pressure.

In our analysis, we identified four primary sociopsychological drivers that stimulated mimicking within founding teams. The drivers originated from the sender, the receiver, or both. The first driver was social proximity. Despite the teams’ heterogeneous experience and skill, mimicry occurred when the stimuli were aligned with an individual’s vision, intention, or work style. This imitation process not only fostered a shared vision within the team, but also promoted various inputs’ integration processes with regard to collectively pursuing common goals. In team THETA, both the founders emphasized efficient work methods’ value, which resulted in their actions being synchronized. Similarly, in team IOTA, social proximity sparked mimicry during collaborative exploration.

When you brainstorm about what you can do together as a [united] team, this makes you innovative, which leads you to new ideas. (F1-IOTA)

The second driver was role modeling. Mimicking was also contingent on whether the initiator’s actions were perceived as worth emulating, especially when it involved effective work practices or the integration of specialized knowledge. The behaviors of co-founders with relevant experience or knowledge often inspired mimicry, because their credibility encouraged others to replicate their successful past behaviors. In Team ALPHA, for instance, F2 willingly adopted numerous work practices, recognizing the potential value that F1 had gleaned from her revious professional experience.

Opinion leadership was the third driver of mimicking. Opinion leaders often drive mimicry by means of directive instructions or by setting strict operational guidelines. We draw a line between role modeling and opinion leadership in terms of behavioral integration and participation. As seen in Team MY and Team KAPPA, opinion leadership was a form of top-down instruction resulting from a personal agenda and overruling others, rather than building on a mutual understanding and on different approaches’ behavioral integration. Here, the sender forced mimicry, whereas, as seen in Team ALPHA, role modeling made an offer to follow the good example without exerting coercion. Moreover, founders tended to mimic more when they lacked certain knowledge, therefore assuming that their counterpart had a superior understanding, which reduced their perceived uncertainty. As we will discuss later, this unconscious mimicry does not always serve the team best. The last driver of mimicking was spurred by subtle social pressure. In Team EPSILON, for example, F2 felt compelled to match F1’s high level of dedication, despite preferring other activities. Here, the subtle pressure to conform influenced F2’s actions.

Because F1 is really ultra-hardworking, this also inspires me to work harder in general. Sometimes I’m just a person who wants to get out and enjoy the sun […] but somehow you think: ‘Oh, we’re not here to chill, we’re here to work. (F2-EPSILON)

In a dialogue with F2, it emerged that F1 did not expect this level of commitment from F2 and even expressed concern about F1 being inclined to burn herself out.

Because I really do a lot, it’s kind of contagious […] I sometimes notice that F2 would like to read a book, but then she sits next to me and is very productive and hard-working. […] I imagine that this over-motivation is probably not so healthy for F2. (F1-EPSILON)

The four sociopsychological drivers of mimicking underscore the founder interactions’ complexity, as it is a delicate structure comprising power and power shift, and, depending on the situation, leading to helpful or harmful effects as shown in the analysis below.

Mimicking behaviors in founding teams: A double-edged sword

In order to assess mimicking’s beneficial outcomes within a team setting, we analyzed scenarios in which teams capitalized successfully on opportunities due to their mimicking behavior. Conversely, we also analyzed instances where teams overlooked opportunities to harmonize their behavior, thereby missing potential benefits. We evaluated the outcomes by focusing on whether the teams enhanced their social capital or managed their paradoxical tensions cognitively.

Leveraging mimicry: Enhancing exploitation and exploration competencies

This section elucidates mimicry’s potential positive impacts, which are systematically applied to exploit and deepen the team knowledge, to align its efforts and goals, or creatively foster its collaborative bricolage by broadening its collective knowledge. The effort to achieve social proximity and the wish to create cohesion were the main sociopsychological drivers. Another driver was role modeling combined with behavior integration, which transformed these teams into efficient problem-solving units with diverse expertise.

In teams ALPHA, DELTA, and THETA, mimicry led to synchronized work behavior to achieve a shared goal (for example, commercial success or professionalization). Mimicry therefore helped establish a shared work foundation for efficient workflows, which in turn helped the teams reach their goals.

We have noticed that there are simply areas in which one is better than in others. We subsequently always try to use this effect […] one [team member] can build a model faster, another can draw it faster. It’s like a factory: if you repeat activities several times, you become more efficient at them. (F2-DELTA).

Further, levering mimicking helped deliver reliable, professional products, even under challenging circumstances. F2-THETA’s statement about switching to an integrated 2D and 3D process, to enhanced workflow, and reduced resource usage is an example of this can.

We have switched to a program in which we have both a 2D and a 3D process. I think this makes our work easier, because we no longer have two programs, but work directly in one. F1 was responsible for this and I then basically re-learned the program. This was a relief. (F2-THETA)

Their synchronized teamwork processes ensured reliability, as everyone knew their responsibilities, which minimized information exchange, saving time and resources. The teams that utilized mimicry exhibited a balance of personal and professional expertise, collaboration, willingness to compromise, reflexivity, and an open culture of discourse, all of which enabled them to integrate their individual strengths effectively.

Sometimes you have very different approaches that lead to different results. But then you look again. What is better? Which approach is best? And how can we develop a common one from all of these? (F2-DELTA)

Team IOTA and XI used mimicry effectively for exploratory purposes. By broadening their existing knowledge base, they enhanced their exploration competencies. IOTA and XI did so by utilizing varied skills’ and diverse perspectives’ synergies via consensus-driven decision making mixed with trial-and-error learning. Inspired by individual experimentation, those founders indulged in collective iteration through creative methods like prototyping and design thinking. Consequently, these processes created a mutual inspiration culture through their willingness to integrate diverse ideas.

With regard to what you can do yourself, at some point you actually develop such a routine and it is difficult to change this routine, which has somehow become ordinary. […] It is precisely this, offering one another input, which leads to you realizing: ‘Okay, you can also combine things. Allowing the disciplines to interplay, enrich one another, and then […] above all […] starting to combine something that is not so compatible at first glance. (F1-IOTA)

IOTA and XI excelled at embracing the richness of differentiation, which allowed them to experiment with the following new business processes: they invested time and resources, took economic risks, and navigated iterative cycles. In more detail, we observed that individual exploration behavior initially stimulated others to challenge their assumptions and patterns during teamwork. In a process of critically examining the existing conditions, the stimuli-receivers discovered new opportunities, gaining a richer understanding of their situation, and a heightened readiness to break new ground. This receptivity reflected the exploration behaviors’ mimicking at the individual level that later evolved into team-wide behavior patterns. A pivotal moment arose when one founder of team XI suggested focusing on the new social media platform TikTok due to its growing popularity. This idea initially faced a degree of skepticism from the other team members, yet they remained open to exploration. We observed vibrant discussions about how to implement and utilize this new medium. After a differentiation phase, marked by individual experiments and dedicated development of various test cases, the team then transitioned into an integration phase, having recognized TikTok’s potential. However, the team was aware of the need to integrate the new offering seamlessly within their existing product portfolio and strategies. In iterative cycles, the founders encouraged each other to leverage TikTok’s strengths (unique selling point and progressive product offering for new customer segments) while maintaining the agency standards (serving existing customers and upholding traditional advertising channels). As a result, the team successfully launched new multiplatform campaigns that blended short and engaging videos with more extensive campaigns on other platforms. This synthesized approach balanced innovative advertisement with established methods, as it appeals to a broad range of clients, attracts new ones, and also ensures a unique and future-proof offering that positions the agency as forward-thinking and versatile. Our data revealed that their shared vision, team leadership behavior (role modeling), and collective tolerance of ambiguity in respect of the unknown enabled this transformation. The interplay between differentiation and integration set the stage for these teams’ development of innovative and competitive products/services.

In sum, mimicry is typically perceived as a unilateral reinforcement of either exploration or exploitation, but is also able to enhance a team’s ambidexterity when discerned systematically via prior evaluation and outcome prediction. We call this systematic mimicry, which refers to the deliberate process whereby founders intentionally replicate observed strategies or behaviors. The founders recognize the stimulus’s underlying principles and, after evaluating their own context and needs thoroughly, choose to adopt these practices to enhance their approaches. Systematic mimicry is able to channel the right resources at the right time to achieve a common goal. A crucial aspect of this mimicry is the effective temporal response and integration of the individual approaches in keeping with the evolving contextual demands of the internal group interaction’s temporal structuring, such as the planning, synchronization, coordination, and allocation of resources. However, the critical requirement is that founders need to recognize when to desynchronize their actions, since it is essential to maintain distinctiveness through cognitive differentiation in order to meet future demands effectively. We therefore propose the following:

Proposition 1:

A founder’s individual, systematic mimicking behaviors could lead to collaborative team wide processes that create the foundation for synchronized efforts, for shared work, efficient workflows, the existing knowledge base’s broadening, and for collective iteration. This progression creates synergistic “exploration” or “exploitation” opportunities, which temporarily enhance the founding team’s chance of becoming more ambidextrous. Social proximity, social assimilation, and role modeling are effective drivers of helpful mimicking behavior.

Pitfalls of mimicking behavior: Exploitation and exploration traps in founding teams

This section examines the harmful consequences of mimicry behaviors in founding teams that led to “exploitation” or “exploration” traps reflecting missed opportunities. Opinion leadership and social pressure are sociopsychological drivers of harmful cycles of unreflective task repetition.

MY and KAPPA exemplify how teams fell into an “exploitation trap,” because poorly contemplated mirrored actions led to wasted resources and hindered their development.

F1 says he has everything in view and then says: ‘The account balance is such and such. We have to sell, sell, sell.’ […] There were times […] when I also started trying to sell, somehow went to Düsseldorf and tried to sell our product there. That was totally nonsensical. But I did it, because I had the feeling that this is what the group expected, that my work wasn’t bringing in any money, and that the most important thing was that we had to sell, sell, sell. (F2-MY)

A poignant case in point is when F2 was pressured to push product sales during the development phase, an action she later deemed “nonsensical.” This short-term revenue focus diminished the team’s capacity to expand their knowledge base. Notably, the absence of clear work roles and responsibilities in both teams led to inefficient or duplicated work efforts. The work overlap increased the workload further, reducing the time for strategic reflection, since the founder simply avoided time-consuming reflection on their actions. Strategy meetings became a luxury and were often sidelined due to work stress. Consequently, personal and team development suffered in the whirlwind of daily business.

Data from team ALPHA serves as a valuable contrast, highlighting how systematic mimicking could benefit efficient exploitation. Nevertheless, the team also risked falling into the exploitation trap. An example was when they failed to utilize an available resource that could have broadened their knowledge base and sparked innovative thinking.

F1 and I have subscribed to a magazine, actually deciding to take a little time out of our workday to examine it. We pay the subscription for nothing. Educating ourselves somehow is actually mega supportive. However, we haven’t managed to read this magazine. I think it’s also a question of whether you allow yourself to do so. I don’t have the feeling that I’m working when I just sit here and read the magazine. You also need to feel as if you’re working, even if you don’t earn money per minute right now. (F2-ALPHA)

Social pressure due to the anticipated expectations was a subconscious driver for F2. It hindered her potential further development. When one considers the view of F1, who had very different expectations of F2’s behaviors than she projected, the following is clear:

I believe that, ultimately, bread and butter jobs also benefit if we take time out to do more research and be creative, as well as serve customers who interest us in other ways. This not only applies to us personally, but also to further creative development. (F1-ALPHA)

Teams EPSILON and LAMBDA illustrate how a founder’s mimicked exploration behaviors could cascade and manifest themselves as an “exploration trap” at the team level. In team LAMBDA, the team members emulated one founder’s excessive focus on exploration, specifically on designing new game elements. This obscured vital exploitation activities, such as implementing the existing level designs in the current game version. Observing a colleague joyfully creating new game elements aroused the LAMBDA team’s desire to do likewise, making the creative activity feel appealing. However, this activity’s appeal was stronger than the critical examination of its actual feasibility, indicating a lack of personal coordination. Moreover, no one wished to be the spoilsport who limited the colleagues’ delightful exploration activities. Consequently, these teams found themselves ensnared in a prolonged and problematic iteration process when exploration mimicry delayed the essential implementation phase. This delay exacerbated the exploration trap, amplifying individual actions to team-level complications. Team LAMBDA’s F1 expressed her frustration during a brainstorming session epitomizing the resulting stress and confusion:

We are all very, very, very creative and all have many ideas and complementary ideas. But to then actually: ‘Okay, never mind, we’re not going to continue now. We’re really going to start implementing it now, even if we have to continue designing it for another year’ (F1-LAMBDA)

Amidst this cascade of mimicked exploration, the teams failed to establish processes to utilize and integrate the existing capabilities and inputs, which culminated in persistent iteration loops, diminished productivity, and, eventually, financial distress.

We refer to unreflected repetition as heuristic mimicry, and refer to observed behaviors when founders—possibly due to time constraints, or constraints regarding resources or cognitive capabilities—choose to respond rapidly, foregoing thorough assessments. Heuristics essentially involved replicating previously observed strategies or behaviors without understanding the underlying principles or evaluating their own situation’s context fully. In light of these observations, we propose the following:

Proposition 2:

A founder’s individual heuristic-mimicking behavior causes harmful team wide processes resulting in overlaps and resource wastage, vision narrowing, and creative hindrance. These dynamics could lead to team wide “exploration” or “exploitation” traps, which hinder teams from becoming ambidextrous. In this respect, opinion leadership and social pressure are forceful drivers.

Exploring the contrarian nature of behavioral switching

Our research unveils a phenomenon that contradicts mimicking, referred to as behavioral switching. For example, one founder’s excessive ideation (exploration) resulted in the other founder demanding a more implementable approach (exploitation); conversely, an emphasis on practicality (exploitation) could result in a shift toward experimentation (exploration). Switching behavior served as an adaptive response that either complemented or rejected the initial stimulus, thereby manifesting itself as a nuanced interplay between the founders’ exploitation and exploration.

Switching could be a conscious strategic choice to promote a shared goal’s positive outcomes by engaging in complementary actions or maintaining group effectiveness through task partitioning. The latter therefore requires recognizing, maintaining, and embracing distinctiveness. Furthermore, switching could be a subconscious coping mechanism for managing one’s emotional state, such as stress, workload, or feelings of being overwhelmed. While offering strategic flexibility, switching has the potential to instigate social friction, since contrary behaviors could defy expectations, thereby causing potential misunderstandings.

Fundamentally, four key sociopsychological drivers stimulated behavioral switches. The first driver was the divergence between founders. Individual variations in problem-solving approaches, work styles, and skill sets often influence behavioral switches. For example, some founders rely more on their intuition when making decisions, while others employ a more analytical approach.

I think I’m a person who prefers to observe. Always,—eyes open and searching. Impulses somehow come from all over. And I would say that F1 is more systematic. (F2-ZETA)

In teams ETA and LAMBDA, one founder’s conservative approach contrasted with the other’s experimental style, prompting shifts in their roles and behaviors.

F2 has a more unusual view. I represent the analytical view. […] I am probably the conservative side of the two of us. F2 needs more innovations. (F3-LAMBDA)

ETA’s F2 captures the following humorously: ” F1 tends toward doing the conventional, and I always try to be more extravagant.” The second driver was encouragement and freedom. An environment promoting diverse perspectives and fostering experimentation could enhance switching behaviors. As observed in team KAPPA, F2’s encouragement motivated the team members to “just do it” and venture into unexplored areas. Further, F2 emphasized the importance of a collective effort, believing that “nothing can be done alone.” This approach nurtured an environment in which each team member’s approach had an essential role. By offering freedom and trust, F2 stimulated behavioral change, asking her team to think independently and broad the knowledge base, rather than following her established patterns. The third driver was workload and external stressors, such as the customers and stakeholders. In team BETA, F2’s tendency to explore occasionally overburdened F1, necessitating a shift toward exploitation. F1 felt overwhelmed by the workload, which prompted him to take up more structured, capacity-planning tasks. Nevertheless, his push toward exploitation was not anchored in strategic consideration, but driven by the desire to handle the open task backlog, which he stated was due to F2’s previously overly extended exploration behaviors. F1 noted:

Currently, our project management is very important to me. We need to evaluate how much time we have both planned. This is really essential, because there’s still a pattern of running behind. (F1-BETA)

A cycle of stimulus and response was apparent when we observed F1’s efforts to deal with stress, thereafter reflected on F2, because F1 indicated a shift from more complex, explorative tasks (using new programming language) to more streamlined exploitation tasks (such as creating sub-pages or entering content with an established programming language) after seeing his colleague struggle. Although F1 acknowledged being less efficient in exploitation tasks, this shift was a coping strategy to mitigate stress and maintain ad hoc productivity. In team NY, the extensive customer demands prompted F4 to transition from her experimental behaviors to focus on “getting things done.”

The last driver was ambiguous task demands. While challenging, different task demands in a project present an opportunity for founding teams to value and leverage their strengths and different approaches. Our observations emphasized that the effect depends on the task demands’ clarity. In team DELTA, F2 described the clear delineation of the task timings, remarking, “It is also very clearly timed in terms of when what is required.” Accordingly, he would react with a behavioral switch from exploration to exploitation or vice versa in response to F1’s actions and the situation’s demand. The degree of ambiguity in the task demands indicated the scope for interpreting and reconsidering the existing beliefs and decisions. The lack of clarity could lead to confusion and divergent interpretations.

Switching processes play a critical role in shaping the dynamics within founding teams and their capacity for exploration and exploitation, as demonstrated in the section below.

Switching behavior in founding teams: A balancing act

To evaluate the implications of behavioral switching in teams endeavoring to become ambidextrous, we examined situations in which teams utilized switching effectively to seize opportunities and influence their dynamics positively. Conversely, we also identified narratives of missed opportunities, in which teams failed to complement their behaviors adequately.

Unlocking switching’s potential: The positive impacts of complementary approaches

GAMMA and NY used switching strategies expertly to turn their exploration efforts into exploitable results, and to transform their co-founders’ pioneering ideas into tangible outputs, such as products or strategies. We refer to this as purposeful utilization, driven by encouragement and freedom, clear task demands, and the complementary use of divergent personalities and skills. Teams that excel at purposeful utilization share a collaborative, goal-oriented, and trust-based environment and an open discussion culture.

GAMMA and NY exemplified successful switching between exploring and exploiting, aided by organized workflows, efficient time management, customer-focused strategies, and insightful market analysis, while also fostering creative thinking. Those teams understood the balance between exploration and exploitation, utilizing each founder’s unique strengths for maximal efficiency and creativity. For instance, after a team member (NY) acquired new market insights and knowledge of upcoming trends at a conference, the team aimed to incorporate this knowledge into their routine processes to guide their development by deepening the overall team knowledge.

Our new employee was just on the panel that dealt with green producing. That means she is interested in the topic and will share it with our company, so that we can examine it together: does this make sense to us? Where could we perhaps develop more in that direction? (F5-NY)

Diverse personalities fuel switching behavior, as exemplified by Team ZETA. F2 described herself as constantly seeking, while F1 adopted a more systematic style. F1 respected this variance, affirming that “both approaches are somehow valid.” The underlying differentiation fostered an environment conducive to a strategic exploration-exploitation balance.

Teams BETA and ZETA demonstrated a strategy of complementary switching toward exploration. They infused exploration into their core processes through a trial-and-error process, thereby broadening the perspectives, and adopting different approaches. This dynamic not only improved their processes, but also incorporated new knowledge into the existing structures. Upholding their vision despite the operational challenges, those teams used long-term visions as guideposts. By fostering a supportive and collaborative environment with open communication and value for diverse perspectives, team BETA and ZETA emphasized innovation and strategic thinking, stimulating their core processes with creative energy. Team KAPPA was another notable example. As F3 pointed out, “I’m the one who determines whether it’s actually good … while F2, for example, now focuses more on innovations … I think that’s actually quite good, because then you can always weigh things up a bit and thereafter find the middle ground.” This embodied experimental learning during which the founders balanced conservative and innovative approaches to hone their strategy. Unrestricted by existing knowledge, the founders ventured into new areas of expertise, enhancing their collective skills and understanding. Their readiness to reevaluate existing beliefs led to a more diverse product offering and the establishment of new norms and structures. They recognized growth as a product of exploration, even when it involved leaving their comfort zones. F2 from Team KAPPA summarized, “It is essential to always continue together, even if it is not on the same footing … Tolerating this is important.”

In essence, switching can bolster a team’s ability to be ambidextrous—balancing effectively between exploration and exploitation—particularly when executed systematically after a collective strategic assessment and committing to shared objectives. We call this systematic switching. Systematic switching leverages different team members’ unique skills and approaches, fostering a complementary interplay that can maximize a team’s effectiveness. When teams employ complementary strategies to address situations optimally, it embodies a form of entrepreneurial structural ambidexterity, because the tasks of exploration and exploitation are spread across different team members. This is especially useful if the activity corresponds to the respective founder’s specialization. However, well-calibrated teams discern when to synchronize their actions, as it is essential to endorse coordinated actions by means of cognitive integration in order to adapt and respond effectively to future demands. This leads us to propose the following:

Proposition 3:

Through individual systematic switching, founding teams navigated between exploration and exploitation. Clear task demands, encouragement, and freedom are the key sociopsychological drivers that promote this helpful switching behavior.

Swichting’s potential perils: Handling emotions

OMIKRON and BETA exemplified how, due to individuals’ heuristic decision making, the workload, external stress, unclear task demands, and divergence in personal inclinations led to the team facing an emotional trap. A heuristic decision is based on mental shortcuts, emotions, rules of thumb, and not on rational, well-reasoned considerations. Team BETA experienced a situative example of a heuristic decision (an emotional, stress-related departure), which illustrated the team’s missed opportunities and a full-scale personal conflict. The conflict concerned F1’s experimental approach of “constantly searching for new visual creations and the next thing that might hit the ground running,” which clashed with F2’s feeling of stress due to the workload and the financial challenges.

F1 always says: ‘I can do it in 3 hours’ but afterwards it takes 5. I then complain about it and then we clash, because I have considerable and justified doubts. Without any requirement to do so, F1 sets a [low] price, I then say: ‘F1, I have no problem with it, as long as we make a little profit.’ But he obviously has a problem with that. Sometimes it stresses me out, because I’m the only one paying attention to profitability. F2-BETA

F2 intervened, demanded better time planning, and advocated an economically efficient approach. By doing so, F2 missed the chance to broaden the team’s knowledge when exploring different methods. A more open mindset could have allowed them to gain insights from F1’s approach. However, F2 maintained that if F1 wanted to continue his approach, he would need the time budget. In addition, he advised him that he should renegotiate his method with the customer. Rather than exploring new ways of balancing their creative processes with their financial constraints, F2 pressured F1 to conform to a more rigid and traditional working method. F2, however, knew that F1 would not do this, which made the situation “a bit of a dilemma,” led to a “period of trying to catch up,” and an immense backlog. The latter caused F1 to react in an exploitative way, while F2 exhibited an exploration stimulus. The BETA team was therefore engrossed in disagreements over the current inefficiency, with this principle conflict nearly leading to the collaboration’s termination.

Conversely, in teams like ETA with discrepancies in the personal and business perspectives and with the professional backgrounds differing, we have noted emotional traps due to affective rejection and a shift toward exploration. The co-founders subsequently responded defiantly with exploration behavior, since they perceived their counterparts’ exploitation as tedious, unsuitable, or dispensable. This counteraction was predominantly rooted in personal inclinations. It lacked complementary purposes, potentially impeding the team’s progress in the long run and was, therefore, indicative of the nascent stages of dysfunctional collaboration. Team ETA exhibited a prime example of such behavior when F2 realized “that it is quite a load to build this infrastructure, this basis for running such a venture.” He subsequently turned to his passion for experimenting with technology and physical devices. Dissatisfaction led to distancing oneself emotionally from the market’s and customers’ supposedly tiresome exploitation or restriction. Team BETA’s F1 commented on this as follows: “Because you’re not quite as happy with your day-to-day business, you then look for a freelance project in which you can again put your heart and soul. And perhaps also the 101% that you’re actually capable of, but which you’re never allowed to deliver to customers, because market constraints forbid it.”

In summary, stimuli might provoke a counter-reaction favoring a systematic or more experimental approach. If emotions such as fear, stress due to customer demands, budget constraints, time pressures, or dissatisfaction, rather than a strategic need, drive the switch, we refer to this as heuristic switching. Disparities in professional skills and personal values could create an emotional rift in a team, thereby impeding collaboration and leading to unclear decision making. Based on our analysis, we propose the following:

Proposition 4:

A founder’s individual heuristic switching behavior could lead to adverse teamwide processes. If guided by emotions, founders might exhibit heuristic behaviors misaligned with the contextual requirements, which in turn lead to “emotional traps” hindering the team’s ambidextrous ability. Factors such as a high workload, unclear task demands, and working style differences drive this process.

Discussion

Theoretical implications for entrepreneurship and ambidexterity research