ABSTRACT

This paper explores why and how some small firms rapidly redesign their business models, while others wait for environmental turbulence to subside. Using multiple case studies, we analyzed changes made to 28 business models by 26 Australian firms, two months after the first COVID lockdown. We discover effectual action patterns utilized as firms redesigned their business models. Three key findings shed light on how effectuation drive entrepreneurial action, first we uncover how framing and entrepreneurial reframing plays a critical role in the contingency effectuation principle. Second our findings show that resources at hand is a necessary, but not sufficient condition for business model redesign. Third partnering, experimentation and affordable loss in combination is most strongly related to small firm business model innovation. Our proposed effectual action framework contributes to the effectuation literature, addressing calls to examine the underlying mechanisms and dynamics that explain effectual action and business model redesign.

Introduction

Environmental instability has become an ever-present reality, ushering in heightened awareness of the precarity of clinging to existing business models, particularly for resource-constrained small firms (Christofi et al., Citation2023; Levallet et al., Citation2023). Small firms dominate the business landscape and account for 90% of firms globally, providing 70% of jobs (OECD, Citation2017) and contribute up to 50% of GDP in high-income (International Labour Organization [ILO], Citation2019). As such, the last five years have seen increased interest from scholars and practitioners to support small and medium-sized enterprises to recover, pivot and digitize as these firms redesign and innovate their business models (Mostaghel et al., Citation2022; Sharma et al., Citation2022; Trischler & Li-Ying, Citation2023). Business model innovation (BMI) refers to the design of new and reconfiguration of existing business models (BMs) (Amit & Zott, Citation2010) and is characterized by a fundamental shift in at least one of the three higher-order BM elements, namely value offering, value architecture (creation and delivery) and revenue model. A change in one of these higher order elements can change the basis of competition for a firm in its market (Gronum et al., Citation2016). Firms may change their BMs due to external changes such as changing customer needs or preferences, competitors’ moves, or due to internal factors like launching an innovation or developing new capabilities. However, radical BM redesign requires strategic decision-making and actions that may conflict with the established dominant BM design logic within a firm (Daood et al., Citation2020).

A growing body of literature explains radical BM adjustments through entrepreneurial actions such as bricolage, experimentation, and effectuation (Alsos et al., Citation2020; Haneberg, Citation2021). These modes of action are increasingly prevalent when considering the uncertainty involved in small firm decisions and actions where the market, technology or environmental conditions are unforeseen and “unknowable” (Grégoire & Cherchem, Citation2020). The absence of predictive information challenges strategic decision-makers when determining what value to deliver to whom, how best to organize resources and how to capture value. As such, studies on the role of effectuation in BMI under conditions of high uncertainty have increased in recent years (Cowden et al., Citation2024).

Media articles proclaimed that the “COVID-19 pandemic plunged the global economy into the worst slump since the Great Depression” (British Broadcasting Corporation [BBC], Citation2020; SBS News, Citation2020), fueling expectations that firms’ established BMs would be disrupted, but also creating opportunities for innovation (Sharma et al., Citation2022). Scholars have studied BMI under varying conditions of uncertainty as COVID restrictions represented radical shifts in operating and market environments, requiring firms to change the way they do business (Levallet et al., Citation2023). Many recent studies explained these BM reconfiguration responses by drawing on crisis management literature, which tend to have a predictive foundation (Chanyasak et al., Citation2022; Ritter & Pedersen, Citation2020). Another emerging stream recognizes the COVID-19 pandemic, as an unforeseeable event class of Knightian uncertainty, as opposed to a foreseeable risk (Mayberry et al., Citation2024) and focuses on effectuation studies, examining BMI in response to crises (Harms et al., Citation2021). However, current literature tends to focus on effectuation as a unidimensional concept (Cowden et al., Citation2024), or singular effectual heuristics such as experimentation with new BM variations (Björklund et al., Citation2020) related to BM redesign. Instead, we address the call of Grégoire and Cherchem (Citation2020) to examine how environmental dynamics function as antecedents to effectual action, using detailed methodological indicators of all the effectual actions and relate these to BM redesign by asking: When a crisis makes existing ways of doing business obsolete, why and how do some small firms rapidly reconfigure their BMs, while others wait out the storm? In doing so we examine how 26 small firm decision-makers dealt with Knightian uncertainty directly after the first COVID lockdown event in Australia, as their established BMs became inoperative, to determine (a) the degree of BM redesign; (b) firm responses to the perceived impact of the unforeseen event using effectual action, and (c) how effectual actions relate to the degree of BM redesign. Semantic analysis of the interviews revealed patterns of firms’ effectual actions, the speed of action and the extent of BM redesign.

By providing a nuanced perspective of small firm effectual action during conditions of high uncertainty, this paper contributes to the BM and effectuation literature in four ways. First, we propose an integrative framework outlining how patterns of effectual action relate to the degree of BM redesign under crisis uncertainty conditions. Second our findings highlight how entrepreneurs leverage contingencies and the role of framing and entrepreneurial reframing for effectual action. Faced with high uncertainty and unpredictability, entrepreneurs reflected on the changed environmental reality, to intrapersonally frame the threat, before reframing it for their team considering different actions to mitigate adverse effects. Third, we show that resources at hand is a necessary but not sufficient condition for business model redesign, however prior experiences of crises are related to higher levels of agility and BM redesign. Fourth, our findings show how patterns of partnering, experimentation and affordable loss is related to business model redesign.

Theoretical background

Effectual action in a crisis

Uncertainty is inextricably linked with entrepreneurial action (Prince et al., Citation2021; Townsend et al., Citation2018), influenced by personal experience and perceptions of small firm entrepreneurs (Cowden et al., Citation2024). As small firms grow faster, their business models need to change more rapidly than large firms (Coad, Citation2007), while facing liability of smallness, as well as environmental and technological uncertainties (Drnevich & West, Citation2023; Gimenez-Fernandez et al., Citation2020). Uncertainty can be categorized as ambiguity, risk, and complexity, where ambiguity involves unclear information, which make predictions challenging; risk relies on probabilistic predictions (Dequech, Citation2014), Complexity acknowledges unpredictable interactions of multiple factors, making it challenging to predict the outcomes of actions (Townsend et al., Citation2018). These types of uncertainties underlie entrepreneurial actions under normal operating conditions. Knightian uncertainty, however, deals with unknowable outcome probabilities (Knight, Citation1921; Welter & Kim, Citation2018), making it impossible to predict outcomes or calculate risks given the information available (Townsend et al., Citation2018) and is associated with radical innovation in frontier markets (Karami et al., Citation2022), pioneering ventures and technological commercialization. Conventional strategy theories fall short in explaining entrepreneurial action under Knightian uncertainty which lead to the development of alternate theories such as discovery-driven planning (McGrath & MacMillan, Citation1995) and effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2009).

Effectuation provides a valuable theoretical lens for understanding how small firms respond to extreme uncertainty (Nelson & Lima, Citation2020; Welter & Kim, Citation2018). Entrepreneurs employ effectual action to navigate Knightian uncertainty, where outcomes and risks are difficult to predict or quantify, like the early phases of the COVID pandemic (Bhowmick, Citation2011). Effectual action enables entrepreneurial actors to draw on their resources at hand to address problems or seize opportunities, allowing goals to emerge contingently from their imagination and diverse aspirations and to co-create the future with those they interact with (Sarasvathy, Citation2001). It facilitates BMI through an evolving process of actions (Karami et al., Citation2022). In radically uncertain situations, the consequences of actions and their antecedents remain unknowable in advance (Grégoire & Cherchem, Citation2020). Five interrelated dimensions characterize effectual actions which start from resources at hand, how unforeseeable events are addressed, partnering, a nonpredictive mindset using experimentation and risk minimization via affordable loss (see Brettel et al., Citation2012; Chandler et al., Citation2011; Reymen et al., Citation2015), are discussed next.

First, effectual action relies on readily available resources at hand found within an individual based on their identity, idiosyncratic knowledge, and networks, as the starting point for action, asking what can be done with what is at hand, rather than setting goals and then gathering resources. Entrepreneurs creatively recombine resources at hand to develop viable products and services (Nelson & Lima, Citation2020). For instance, microbreweries and distillers repurposed alcohol into hand sanitizer at the start of the pandemic. Second effectuation views unexpected events as sources of opportunity, rather than obstacles (Reymen et al., Citation2015), fostering adaptability and leveraging unforeseen events to still move forward (Chandler et al., Citation2011). Parris et al. (Citation2018) illustrate how effectual action was used in a hurricane emergency, to turn an unexpected event into a collaborative innovation opportunity by the CEO of Second Harvest Food Bank (SHFB). Contingencies can thus be addressed by embracing the third principle of partnering with pre-committed stakeholders that expand the resource base and contribute to goal emergence (Reymen et al., Citation2015). Fourth effectuation encourages a nonpredictive mindset for learning through experimentation by focusing on what works and iterative feedback, rather than elaborate analysis, enabling rapid improvements (Andries et al., Citation2013; Barnes & de Villiers Scheepers, Citation2018). Finally effectual action minimizes risk by embracing affordable loss, emphasizing the importance of minimizing downside losses by not risking more than one is prepared to lose (Sarasvathy, Citation2001). Therefore, effectual action allows for rapid learning, cost reduction and agile market entry (Chandler et al., Citation2011). Haneberg’s (Citation2021) study on 103 hospitality SME managers’ responses to the second wave of COVID, illustrates that learning is related to experimentation, while uncertainty is related to affordable loss.

Effectuation research has attracted an increasing interest from entrepreneurship researchers, as a response to different types of uncertainty. provides an overview of recent literature (2018–2022) exploring uncertainty and effectuation in relation to business model innovation and firm performance. Focusing on the last five years encompass firms’ responses to the first wave of the pandemic, providing relevant and comparable literature to theorize and extend prior research. The types of uncertainty investigated include environmental uncertainty (Futterer et al., Citation2018; Karami et al., Citation2022; Pacho & Mushi, Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2022), and different types of crises such as natural disasters (Nelson & Lima, Citation2020), economic crises (Laskovaia et al., Citation2019) and more recently different stages of the pandemic (Aggrey et al., Citation2021; Björklund et al., Citation2020; Haneberg, Citation2021; Harms et al., Citation2021). Most survey research designs rely on Chandler et al.'s (Citation2011) operationalization of causation and effectuation (Haneberg, Citation2021; Harms et al., Citation2021; Laskovaia et al., Citation2019; Pacho & Mushi, Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2022), treating effectuation as an independent variable from a variance-based theory perspective, which has been criticized by several scholars (Arend et al., Citation2015; Gupta et al., Citation2016; McKelvie et al., Citation2020), given that effectuation is a process theory. Qualitative research designs, using a process approach, which concentrate on temporal development, such as Karami et al. (Citation2022), is much closer to Sarasvathy’s (Citation2001) original conceptualization.

Table 1. Overview of recent effectuation studies (2018–2022).

Furthermore, as shown in , few studies examine all five effectuation dimensions, with many scholars only focusing on the four dimensions operationalized in Chandler et al’s (Citation2011) scale (Laskovaia et al., Citation2019), while others have focused on singular dimensions (Björklund et al., Citation2020; Haneberg, Citation2021; Xu et al., Citation2022), exploring how learning influences small firm decision-makers’ responses. Only Harms et al. (Citation2021) considered the configuration of effectuation and causation dimensions in examining how 128 gastronomy entrepreneurs responded to COVID lockdowns to innovate their business models. A dearth of scholarship exists concerning how entrepreneurs and small firm managers leverage contingencies, with most studying the outcome of such actions as flexibility. A notable exception is Nelson and Lima (Citation2020) who studied the experiences of residents of the Córrego d’Antas community, Brazil, after deadly mudslides in 2011, and explaining how contingency was leveraged through improvisation. Our study addresses this gap, by considering entrepreneurial framing as narratives (Snihur et al., Citation2022; Thompson & Byrne, Citation2022) to explore how entrepreneurs transform adversity into opportunity. In addition, we consider the role practical knowledge and entrepreneurial experience play in how uncertain events are framed when redesigning BMs, given that prior research has emphasized the role of these factors in enhancing or constraining an entrepreneur’s competence, thinking patterns, and creativity (Holzmann & Gregori, Citation2023).

To address Grégoire and Cherchem’s (Citation2020) call for more rigor in effectuation research, this study focuses on the effectual actions of small firm decision-makers in response to the uncertainty brought about by the severe restrictions of the first COVID lockdown in 2020, as they redesigned their BMs. The COVID crisis’ social isolation measures induced a sense of urgency among entrepreneurs to experiment with new BM solutions (Björklund et al., Citation2020; Clauss et al., Citation2022).

Business model redesign and business model innovation

BMI is the result of reconfiguration of existing firm’s BM due to purposeful, inventive, and nontrivial changes (Foss & Saebi, Citation2017). Alternatively, it can also be described as a process involving the design, implementation, and validation of an entirely new BM (Massa & Tucci, Citation2014). Recent research has seen definitional convergence on the BM construct, broadly described as the heuristic logic of how a firm does business (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Citation2002), describing the “design or architecture of the value creation, delivery and capture mechanisms” of the firm (Foss & Saebi, Citation2017; Teece, Citation2010, p. 172) in concert with its boundary-spanning relationship network (Zott & Amit, Citation2010). In line with this definition, we categorize the BM to include four broad elements: the value proposition (including the offering and target market/s), value creation, value delivery architectures (including key resources, networks and activity architectures required to produce and deliver the offering), and value capture (cost and revenue models).

The BM represents an innovation blueprint for entrepreneurs, with innovation classified as incremental or radical, depending on the cognitive distance from the current BM (Daood et al., Citation2020). The degree of BM change is used to distinguish between BM evolution, adaptation, and innovation, which can entail minor adjustments to align with external environmental changes (Saebi, Citation2015) such as changing customer behavior, competitor strategies or exogeneous shocks (Gronum et al., Citation2016). Firms’ BM adaptations are driven by the impetus to achieve competitive advantage and improve their performance (Heikkilä et al., Citation2018), however they can be constrained by dominant logic (that is, the mindset developed through previous success experience) (Daood et al., Citation2020). Dominant logic can function as “blinders on a horse, allowing organisations to perform well at their current task in the short term, […], but also limits our peripheral vision” (Prahalad, Citation2004, p. 178). Changing BM elements and potentially the dominant logic of how a firm does business, is referred to as either business model design (redesign), or BMI. Amit and Zott (Citation2020) eloquently describe the difference between BM design and BMI considering the recent COVID pandemic disruptions, which required firms to strategically rethink substantial structural changes to their business models, requiring BMI. In contrast BM design or redesign implies tweaking BM elements to build higher efficiencies, by aiming to find an efficient value architecture. Therefore, BMI implies holistic change to the underlying dominant logic of the BM through novel changes to core elements therein (Futterer et al., Citation2018).

BMI can be classified into four distinct types, based on its novelty and scope (Foss & Saebi, Citation2017). The degree of novelty refers to whether BM changes are only new for the firm, or an entirely new concept within an industry, which renders it incremental or radical respectively. The scope of BMI refers to modular or architectural changes. Modular BMI relates to specific BM sources and components of value, emphasizing changes in the single components of a BM, such as entering new industries, changing the revenue model and/or redefining organizational boundaries, and innovating technologies. Architectural changes examine new ways of linking activities or governing activities, as well as novel links between BM components (Clauss et al., Citation2022). Innovating one or more core elements necessitate alignment and changes of other BM elements (Johnson et al., Citation2008). Although a complete redesign of all BM elements is not a precondition for BMI, radical or substantial changes to a BM element represents a change to the underlying dominant logic of the BM and would normally require realignment of other BM elements (Futterer et al., Citation2018). Dominant logic is likely to steer firms toward incremental, modular BMI (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Citation2002) with several researchers demonstrating the need for experimentation to innovate BMs (Engwall et al., Citation2021; Futterer et al., Citation2018). Yet researchers have found that a severe crisis may trigger a reflection on the validity of BM logic, and under these uncertainty conditions, firms may have a stronger incentive for BMI (Clauss et al., Citation2022; Corbo et al., Citation2018; Sosna et al., Citation2010).

As small firms respond to environmental uncertainty, it is essential to recognize that innovating one or more core elements of the BM, necessitates alignment to other elements (Filser et al., Citation2021). We integrate prior conceptualizations of BM redesign (Chesbrough & Rosenbloom, Citation2002; Daood et al., Citation2020; Foss & Saebi, Citation2017; Saebi, Citation2015; Zott & Amit, Citation2010), given the fragmentation in the literature (Foss & Saebi, Citation2017) and theorize that small firms adjust their BMs based on the degree of novelty and scope of change in BM elements, related to their dominant logic and the required competencies. Minimal BM changes involve little novelty, as a single BM element changes (Amit & Zott, Citation2012), with no change in dominant logic or firm competencies. Incremental BM redesign entails substantial changes to one or more BM elements new to the firm (Bock et al., Citation2012), but not fundamentally changing how the firm does business and where the competencies required is learnt internally or can be outsourced. Radical BM redesign introduces extensive changes to multiple BM elements, representing a significant increase in novelty (Gronum et al., Citation2016) and transforming the firm’s dominant logic and core competencies. Finally novel BMs represents architecturally new BMs, as all BM elements are new and needs to be configured (Foss & Saebi, Citation2017), with minimal remaining connections to the prior dominant logic, requiring renewal of firms’ competencies (Zott & Amit, Citation2010). As small firms are resource constrained, agility likely plays a key role in the redesign of BMs.

BM redesign temporality and environmental uncertainty

Small entrepreneurial firms’ BMs are dynamic and fluid, as these firms need to adjust their BMs, as the environment changes (Saebi, Citation2015; Wirtz & Daiser, Citation2018). Entrepreneurs view BMI as the enactment of a new strategy (Magretta, Citation2002) in creating differential advantage, exploiting opportunity, or adjusting to change (Bock et al., Citation2012). Doganova and Eyquem-Renault (Citation2009) argue the temporality of BMs in an entrepreneurial context not to be of chronology but of kairos; a window of opportunity to be grasped. BMI resides in both chronological and kairos temporality.

Saebi (Citation2015) uses a contingency framework to explain BM dynamics involving evolution, adaptation, or innovation, depending on the level of environmental change and firms’ dynamic capabilities. Firms that operate in benign, predictable environments are likely to make incremental BM adjustments, allowing for natural evolution. However, when environmental change increases in frequency, unpredictability and velocity, more adaptive and innovative firm responses might be called for, as is the case in a crisis, technological breakthroughs or shifts in customer behavior (Cozzolino et al., Citation2018). Discontinuous environmental shifts prompt radical responses from firms. Crisis management and business resilience research commonly find that crises can trigger innovation and spark entrepreneurial activity (Bullough et al., Citation2014; Monllor & Murphy, Citation2017; Williams & Vorley, Citation2017). For example, Corbo et al.’s (Citation2018) study of the Portuguese footwear industry following an exogenous shock required firms to reconfigure their BMs to speed up manufacturing and respond flexibly and rapidly to customers. Similarly small service firms changed the BM value architecture during COVID lockdowns, such as hospitality venues adapting to provide takeaway meals instead of in-venue dining or making supply chain changes. Such firm responses require adaptive change capacity (Saebi, Citation2015). A recent meta-analysis confirmed a positive BMI-performance relationship, moderated by economic and political instability (White et al., Citation2022). BMI is therefore associated with dynamic environments and conditions of high uncertainty.

BM redesign processes are complex, and the nature of the BMI processes are fragmented and ambiguous (Wirtz & Daiser, Citation2018). Andreini et al. (Citation2022)’s systematic review categorized BMI processes from 114 papers published between 2001 and 2020 into evolutionary learning processes with four types of processes namely cognition processes, knowledge-shaping processes, strategizing processes and value creation processes. They call for future research to examine the patterns of these processes as experimentation and trial-and-error are fundamental to the knowledge-shaping BMI processes. Similarly, Filser et al. (Citation2021) bibliometric review and trend analysis confirm the importance of learning and experimentation for BMI and call for more empirical studies on small firm BMI. Trial-and-error learning through experimentation represents an effectuation principle and Futterer et al. (Citation2018) found that effectuation is an effective approach to BMI in high industry growth settings, where industry growth has been used as a proxy for uncertainty (Antoncic & Hisrich, Citation2001). Their findings align with Sarasvathy’s (Citation2001) arguments that effectuation seeks to capitalize on contingencies and uncertainty. Yet Futterer et al. (Citation2018) called for a more in-depth empirical examination of the effectiveness of entrepreneurial behaviors for realizing BMI. This paper addresses the gap these authors identified by investigating why some small firms rapidly reconfigure their BMs or develop new ones, while others wait out the storm, in times of extreme uncertainty.

Method

To address the research question, we employed a multiple case study design, appropriate for theory elaboration (Creswell & Poth, Citation2016; Ridder, Citation2017; Yin, Citation2018). Multiple cases help to reveal variances in processes and facilitates theoretical inference (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2016). We studied 28 business models deployed by 26 Australian small firms, collecting data two months after the first national COVID lockdown. Interview and secondary data allowed for interpretation of richly associated meaning in a natural setting permitting the emergence of novel insights (Makela & Turcan, Citation2007) from small firm decision-maker reflections. The research design accounts for the multiple socially constructed realities of decision-makers (Urquhart, Citation2012) acknowledging the complicated nature of their experiences, interpretations and actions given the lockdown restrictions’ impact on BM decisions (Patton, Citation2002).

Case selection and data collection

We used theoretical sampling to examine contextual conditions representing extreme uncertainty experienced by entrepreneurs in regional Queensland. Theoretical sampling seeks pertinent, selective data related to refining and filling the emergent constructs of interest in this study (Birks & Mills, Citation2011; Charmaz, Citation2006). During the first national six-week lockdown, March 23 to May 2, 2020, only businesses with no customer contact and those providing essential services were permitted to trade, followed by some easing of restrictions. It was unknowable at the time when all restrictions would be removed, and trade as usual would resume. The inability of decision-makers to predict how the pandemic would influence consumer spending, supplier decisions and future government announcements, made it impossible for them to adjust their responses in a way that they might gain advantage (Waldman, Citation2003). As such this period represents Knightian uncertainty, given the absence of information. As restrictions were geographically imposed, we selected firms in the same region, all facing the same restrictions. At the time Australia’s severity of response was rated at 73.15, compared to China’s 81.02, considered the most severe (Hale et al., Citation2020). While small firms account for 98% of Australian firms, employing 44% of the country’s workforce (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS], Citation2020), these firms also have little reserves and were substantially affected by the impacts of the pandemic. The stringent lockdown measures led to Australia’s first recession in 30 years, as the GDP shrank 7% in the April to June 2020 quarter, and unemployment rose to 6.9% (Australian Treasury, 2020–21). To mitigate the anticipated economic shock a series of government support measures were introduced, such as wage subsidies, tax relief, and instant asset write-offs (Higginson et al., Citation2020). Some industries were disproportionately affected by the restrictions as unpredictable fluctuations in consumer spending, travel restrictions, and border closures meant that arts and recreation, accommodation, food services and travel providers were most severely affected by restrictions (ABS, Citation2020). Comparatively, sectors such as building and construction and mining experienced less severe impacts. Our sample included firms of varying sizes, ages, and industries to analyze their responses through within- and cross case analysis.

Cases were purposively sampled to ensure information-rich data. We searched for cases that met the following criteria: (a) entrepreneurs needed to have the authority to initiate and implement BM changes; (b) established firms (older than two years) with proven BMs employing at least three staff members; and (c) with head offices within the same specified region. Collecting primary data two to three months after the first six-week lockdown provided an ideal temporal context to study how small firms responded when established BMs became maladjusted. Potential case firms were invited to participate in the study through newsletters of regional business networks, with members interested in growing their firms’ revenue and customer base. From the 45 firms that expressed interest, 26 met the criteria. Interviews provided rich data as decision-makers talked through their thought processes, responses and changes made to BMs, in vivid detail, given the recency of events. We informed all case study firms about the academic nature of the research, the research ethics protocol and that all responses would be de-identified and no commercial in confidence information shared.

We first collected secondary data from news and government websites regarding environmental conditions, firm webpages, and social media announcements. Second, we developed a seven-page interview protocol based on the literature review, to interview key informants of the selected case firms (see summary ). Interviewees were asked about the firm, their own experience and background and trajectory of the firm prior to the lockdown being announced; how the restrictions influenced their firm; and their responses, in reference to changes they made to products and services, business operations and financial activities. In addition, participants were asked about collaborations with other firms, outcomes from the changes made and their personal reflections and learnings. Interviews lasted between 45 and 110 min.

Table 2. Summarized interview protocol.

Interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed, and sent to participants to check for factual accuracy. The interview transcripts analyzed consisted of 740 pages. These were supplemented by secondary data and interviewers’ research notes, which represents an additional data source. To counterbalance the risk of recall bias and ascertain whether actions were implemented, two research team members were present, and responses were triangulated by secondary data sources, prior to the interview and three months later, addressing concept validity and confirmability in the research design (Riege, Citation2003). Using multiple data sources provided a richer understanding of how reflective interview accounts translated into changes to the firm’s value proposition and value architecture of the BMs.

The 26 case firms included 11 firms, employing less than 5 employees, 11 firms employing 5–20 employees and three firms, employing 21–199 employees, which resulted in the inclusion of two entrepreneurs launching start-ups during the study period, therefore 28 business models were analyzed. The majority (34%) of firms were established two to three years ago, while four firms had existed for longer than 15 years, as shown in . As with similar studies the rich case study data collected allows for in-depth qualitative analysis and theory elaboration (Ridder, Citation2017; Zahra, Citation2007).

Table 3. Case profile and characteristics.

Data coding

The data coding and initial analysis included techniques focused on (a) understanding common themes across all case study firms regarding actions taken, given the extreme uncertainty and (b) recognizing patterns of effectual action and BM redesign through within-case and cross-case analysis and finding theoretical interpretations of these patterns (Yin, Citation2018).

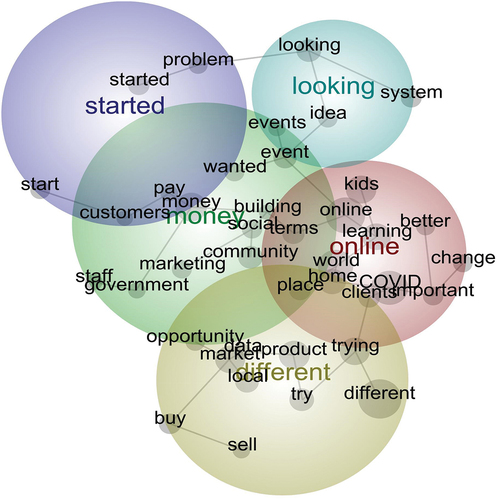

The first step was to conduct content analysis based on the 26 transcribed interviews by uploading these to Leximancer, a text analytical visualization software package, that content analyzed interview transcriptions and identified related concepts by generating a conceptual map, as shown in . The conceptual map is represented as a “heat map” indicating the connections among concepts, with the most prominent themes represented in red, followed by orange, while cooler colors (blue and green) denote the less common themes (Leximancer, Citation2021). These initial common themes provide a way of triangulating our interpretation. As Leximancer cannot replace human coding and interpretation (Indulska et al., Citation2012), manual thematic coding was also performed to ensure consistency and enhance the robustness of the coding (Sinkovics & Archie-Acheampong, Citation2020). Insights from the concept map were supported by within-case pattern coding and cross-case comparison.

The manual coding of cases first focused on within-case analysis using precoding, open coding, and categorization (Spiggle, Citation1994). The categorization of effectual actions and BMI was supported by a detailed coding scheme, as Grégoire and Cherchem (Citation2020) recommend specifying how BM reconfiguration and associated dominant logic relate to value offering, value architecture and value capture, while effectual actions were related to the five dimensions of using resources at hand, leveraging contingencies, cocreation through partnerships, experimentation, and affordable loss. Then cross-case analysis categories were compared, and aggregate theoretical themes identified (see ).

Finally, pattern coding was used to consolidate coherent themes during cross-case analysis and examine how effectual actions were related to BM redesign (Miles et al., Citation2020). The cross-case pattern analysis enhances the transferability of findings to other contexts and aid understanding and explanation (Miles et al., Citation2020; Yin, Citation2018). Two members of the research team undertook the within-case analysis, checking and confirming iteratively, where themes were further categorized and classified as shown in , using magnitude coding to code the intensity and presence of the concepts and themes of interest (Miles et al., Citation2020), namely perceived severity of the crisis, effectual actions (starting with resources at hand, partnering, experimentation, affordable loss), agility and the degree of change for the BM elements. A rating scale of high (5), medium (3) or low (1) was used for perceived severity, most of the effectual actions and agility. For contingencies and resources at hand the presence or absence was coded, with yes (5) or no (1) coded. The two research team members independently rated each case firm on the concepts, with high interrater agreement (90%). Differences were discussed, and categorization reconsidered until agreement was reached.

Table 4. Magnitude coding scheme to facilitate pattern coding.

This process was continued for the cross-case analysis with three research team members involved iteratively to discuss and refine the emergent patterns.

Analysis and findings

Leximancer thematic map

reveals the importance of reconfiguring and redesigning BMs related to effectual action. The most prominent theme is online, reflecting how COVID restrictions brought about changes to home and business life and how these spheres melded. While entrepreneurs were working online from home, they adjusted to restrictions, interacting with clients in the same space where their children were learning from home.

The second theme of money relates to the perceived risks and effectual contingencies. Participants saw cash flow and financial risk as an immediate concern, related to how to keep their staff and minimize financial losses, while international bookings and events were canceled, projects deferred, and potential revenue was lost. Their reflections demonstrate concern for customers and employees and attempting to keep in touch via social media. At the intersection of the first two themes the uncertainty as to how long these disruptions would last are linked to staff and operational business decisions.

The third theme of doing business differently and trying different things is directly linked to BM adjustments of value proposition, creation, and delivery architecture elements, via delivery of goods. These changes held implications for the cost and revenue BM elements of firms. Trying different things relates to experimentation, as firms found that their BMs did not fit the changed environment. This theme was also related to seeing opportunities by looking at the crisis differently in delivering value to customers. The colder themes of looking at ideas and starting to act or solve problems suggest that not all firms were able to move to action new ideas and increase revenue options, given the uncertainty of COVID restrictions and when things might return to normal.

Business model redesign

The profiles of the 26 cases are related to the breadth of changes in the BM elements of value proposition, value creation, value delivery and value capture and the perceived impact time horizon of the change/s (short vs longer-term) in , categorized as four business model (re)configurations. As two serial entrepreneurs started new firms six and eight weeks into the pandemic 28 business models are coded (refer cases 4b and 7b). Most decision-makers are older than 30 years, with the majority having owned at least one business previously. When asked if they had experienced other crisis events, 61% of decision-makers indicated that they managed their firms through contingencies such as natural disasters, or the Global Financial Crisis.

Table 5. Business model redesign categorization.

Four BM reconfiguration descriptors were used to include novel, radical, incremental, and minimal redesigns, as we theorized based on the dimensions of novelty and scope of change of the BM elements (see ). Five case firms redesigned their BMs in such ways that it can be categorized as novel BMs. To enact the new BM elements required these firms to develop new competencies, through learning and experimentation, to deliver new products and services and enter new market segments. Two-thirds of firms expanded their customer focus to include international customers, after their BMs were reconfigured. These changes suggest a more permanent change to resource configurations. In two of the cases, the serial entrepreneurs involved launched new ventures, with one related and one unrelated BM developed, compared to their existing firms. For Case 4, a franchised gym, which was mandated to shut down for 6 weeks (Case 4a), the entrepreneur launched a nutrition venture focused on supplying healthy, balanced meals to the fitness market, related to the gym (Case 4b). For Case 7, a niche agribusiness which needed to find new customers and change the shelf-life of their agriproduce (Case 7a), the entrepreneur developed a new unrelated BM to provide COVID-safe trolley handles (Case 7b) to retail grocery consumers. In 11 of the 26 cases, entrepreneurs radically redesigned their BMs. All firms changed the value delivery element, while the majority also changed their value creation and value propositions, and two-thirds changed the value capture element too. To comply with COVID restrictions many of these firms increasingly invested in digitizing BM elements, through outsourcing, suggesting that these BM changes are likely to be more long-term, especially if shifts in customer behavior are also more long-term. Novel and radical BM redesign was related to the new competencies these firms developed in the process, aligned to Zott and Amit’s (Citation2010) BM design elements of content, structure and governance. Firms who made incremental BM changes quickly complied with COVID restrictions, predominantly focusing on temporary value delivery changes, leveraging their existing competencies to adapt. In some cases, this resulted in value creation and value proposition changes. Incremental BM changes are largely temporary, as these firms intended to revert to their prepandemic BM that fit their cost structures. The main aim of firms who made minimal changes to their business models was to survive through the crisis and therefore the BM changes were directed at complying with regulations and minimizing losses generally. These changes were typically temporary, as firms intended to revert to the status quo after restrictions were lifted.

The BM redesign categorization in relation to entrepreneurs’ experiences with crises and BM redesign breath (see ) provides two interesting insights. First, most entrepreneurs in the sample are serial entrepreneurs, with 61% having had previous experiences with severe contingencies, such as crises. The data suggests that in some cases having experience with prior crises favors more adaptive and radical changes to multiple BM components, increasing then tendency to redesign the BM to a point, while other entrepreneurs’ previous experiences made them more cautious and less likely to implement changes. Second, BM reconfiguration breath refers to the degree and diversity of changes in the BM. Firms that have made novel and radical BM changes were likely to reconfigure most BM elements, in contrast to incremental or minimalists. The most common BM element most case firms changed was value delivery, given that COVID restrictions required changes in this area. Value creation was the second most prevalent element that was changed, as expected given employees and suppliers were impeded by COVID restrictions. Only half of cases changed the value capture elements, and this was predominant among those engaging in novel and radical BM changes. Novel BMs tended to be more opportunity-focused, suggesting these decision-makers reframed the crisis as an opportunity for creating new value, or adapting the value created, delivered, and captured.

Effectual actions in response to extreme uncertainty

Our findings are organized according to the coding structure in , which groups 24 second- order themes into eight aggregate dimensions representing the perceived severity of the crisis, five effectual actions namely contingency, starting with resources at hand, partnering, experimentation and affordable loss as well as the final dimension of the agility by which small firms reconfigure their BMs.

Perceived severity of the crisis

The perceived severity of the crisis, as the first aggregate dimension, reflects the extreme uncertainty that the restrictions created for firms related to customer disruptions, harmful impacts on staff and negative financial impacts. Case study firms perceived customer disruptions based on the loss of significant income in less than a week (C6, C7a, C8, C9, C20), as events were canceled (C1, C5, C6, C15, C22, C23), suppliers and case firms were forced to close (C3, C4a, C11, C12, C14) and export orders were canceled (C6, C7a, C8) placing cash flow under pressure. The severity of the crisis was also related to harmful impacts on staff for instance casual staff who did not qualify for wage support, international students left stranded (C1, C2, C12) and teams working on industrial sites needed to work with fewer staff and maintain physical distances (C12). Finally, negative financial impacts were connected to the forced closures of gyms and tourism firms whose income was reduced to zero overnight (C1, C2, C3, C4a), projects delayed (C14, C11, C17), while fixed costs still needed to be paid and some case firms that committed to infrastructure investments prior to the lockdown remained contractually bound (C6, C12, C25, C26).

Effectual actions

How firms leveraged contingencies to view unexpected events as opportunities, rather than roadblocks (Sarasvathy, Citation2009), emerged from our coding of the data to have two dimensions, namely decision-makers initial response to the event before framing and entrepreneurial reframing of the event (see ).

The initial response to the unforeseen event reflected the shock decision-makers experienced in comments such as “We lost pretty much … six to eight months of revenue … it was very, very dark days” (C19) and “It was brutal” (C20). This shock was accompanied by the paralysis most case firms experienced. Many decision-makers characterized this period of inaction as highly stressful and being unsure of what to do. One participant explained this as the startle factor (well-known in aviation) referring to an uncontrollable, automatic reflex elicited by exposure to a sudden, unexpected intense event, as most decision-makers initially tried to process what had happened and “trying to work out what to do next” (C20).

Thereafter followed decision-makers’ framing of the problem, with some reframing it, related to the action mechanism of contingencies. For this theme, firms can broadly be divided into two groups. On the one hand decision-makers who tended to be paralyzed, remained reactive and framed the problem as being “virtually impossible” to address and being unable to act (C2, C5, C20, C25, C26), while on the other hand others first engaged in silver lining self-talk by focusing on what could be done or changed. For example, C6 explains her thinking as: “It’s disappointing … it’s done … not putting energy into something that can’t change, focus on what can be changed,” while C19 describes his self-talk as: “Rather than sitting back, like our competitors, I said: Hang on. The need has gone up. We can service this market even better” and C4a “finally having the extra time to focus on new innovation.” This personal silver lining self-talk was then expanded by engaging employees in collective reframing by working as a team to address the problem of “what can we do differently” (C5, C17, C19, C24).

Starting with resources at hand, as the fourth effectual action dimension was related to the personal predisposition of decision-makers, starting new practices, and pooling the knowledge of a firm’s employees as a starting point. The personal predisposition of decision-makers theme refers to decision-makers finding starting points of actions based on their personal resources at hand by focusing on daily tasks (C4, C9), avoiding getting stuck by accomplishing small milestones (C1, C10), being open to serendipity (C7, C14, C17) by harnessing their own personal knowledge, or observations of what customers might need and reaching out and talk to others for ideas, feedback and recommendations (C18). The first-order codes denote a propensity toward action, which is related to the second theme of starting new practices such as ways of working differently (C3, C10, C17), exploring different ways of distributing and delivery of goods (C3, C6, C7, C22), delivering online classes in different ways such as starting a podcast (C21, C15, C19) and setting up online shops (C1, C5, C12, C15), similar to the Leximancer map. Further, the resources of entrepreneurs were augmented by pooling the knowledge of some employees to develop online resources for previously personalized services (C3, C4, C15), and rebranding and improving websites enabling customers to engage with case firms more easily online (C1, C13, C10, C24).

The partnering dimension revealed that small firm-decision makers differ in their degree of engagement with those “outside” the firm. Case firms that made minor BM changes tended to be more cautious in sharing information with outsiders, while firms that have made more profound BM changes tended to embrace partnering by working within relationally focused exchanges and jointly develop new initiatives with others. Cautious firms even reached out to competitors regarding expected external changes and how these changes might affect them (C2, C5, C20) and discussed eligibility for government support with trusted advisors such as accountants (C5, C13, C26) or business support agencies (C2, C6, C17). Sharing information with outsiders tended to relieve stress as advisors were able to provide different viewpoints (C9, C13, C19). Some firms collectively shared stories and solutions that they have tried (C4, C15). Those firms adjusting their BM by partnering, emphasized key customer relationships, which was prevalent among firms who adapted their services to suit the changed needs of their business customers (C14, C17) and developed new product lines (C3, C4b, C12). As the pandemic limited the geographical distance people could move, local initiatives flourished and reciprocal exchanges (buying and giving) within local communities prevailed, evident for agrifood (C6, C7, C8) and industrial firms (C10, C12). Collaborators emphasized the importance of complementary skills and value alignment (C22, C23, C25, C26). Finally, some firms indicated that they jointly developed new value-added products and services (C6, C7), worked with local producers (C22, C9) as mutual benefit were gained through partnering (C6, C7, C9, C22). Initiatives such as collaborative marketing and bundling products and services increased value to end-customers (C1, C4b, C6, C12, C15).

Experimentation, the sixth dimension, reflected a nonpredictive approach was utilized by firms making extensive BM changes, through modifying work practices, products and services, as well as iterating and pivoting based on feedback regarding changes. Work practice modifications depended on industry demands, for example the deployment of smaller onsite teams to adhere to restrictions (C12, C18). For firms that worked remotely, some entrepreneurs emphasized the importance of team social cohesion and aimed to build morale by engaging in fun activities (C17, C14), by adapting the work practices to show care for employees (C1, C16, C19). Several firms experimented with product/service modifications. Others developed new products and services, offering customers free trials in exchange for feedback (C3, C19) utilizing prosocial exchanges. These changes enabled further iterations (C22, C4b). Software firms were well-placed “to stay relevant” (C17) through modifications and using virtual reality technology for remote training (C14). Many changes were done using trial and error, iterations, and pivots to adapt to changing customer needs. Decision-makers who changed their BMs started by testing small changes, and then scaled up based on demand growth (C3, C17, C1) and differentiated their online offerings (C19, C4b). Their attitude to iterations was to develop an “MVP that is 3/10, so good enough, as it can be refined” (C3, C17).

Affordable loss was linked to themes of cash conservation, timing of asset investments and minimizing risk by learning new competencies. Cash conservation was realized through operating lean or using bootstrapping tactics such as bolstering financial reserves, renegotiating credit terms with customers and securing stock in advance (C12, C11, C10), with the owner-managers taking a salary reduction (C17, C19, C22) and self-funding lean new product development (C4b, C7b, C19). Some agrifood firms collaborated and created a central distribution point for customers to pick-up products, rather than delivery (C6, C7a, C8). These cash conservation strategies accompanied the transition to online BMs where the timing of asset investments was linked to restrictions. Several firms upgraded their digital infrastructure and websites (C1, C6, C15), while others used multiple trials for evidence of changed demand and adapted value delivery (C17, C19, C14). Firms who changed their BMs to include deliveries (change in value creation), invested in new delivery trucks (C10, C12), anticipating a longer-term BM change. Learning new competencies to minimize risk pointing to affordable loss, was strongly related to the digital shift in BMs as firms learnt to manage remote teams (C14, C17, C24), developed e-commerce sites (C1, C13), learnt digital skills for online sales (C8, C15), and developed downloadable guides to facilitate customer self-service (C10, C12). As recorded video assets became a more important asset, some firms improved their video production and editing skills (C3, C19), as well as data analytical skills to learn how to improve their future value offerings (C14, C17, C19).

Finally, the response speed and agility of case firms, was coded as three different speeds (see ). Firms that took longer to change tended to have large fixed-cost structures and characterized their actions as “just treading water” (C2), “looking into alternate possibilities” (C20) and long lead-time projects (C11, C26, C25). Firms that embraced a moderate rate of change adjusted BMs to match client needs (C10, C18), acknowledging that while in learning mode, some activities take longer (C9) and using slower times for research and development to their benefit (C16, C22). Firms that changed rapidly focused on getting “up and running quickly” (C7b), “launching within a month and getting to capacity by two months” (C4b), getting to minimum viable product quickly (C3, C17) and “executing a 12-month strategy within six weeks” (C19) accelerating the transformation of their BMs (C14).

Response patterns to extreme uncertainty

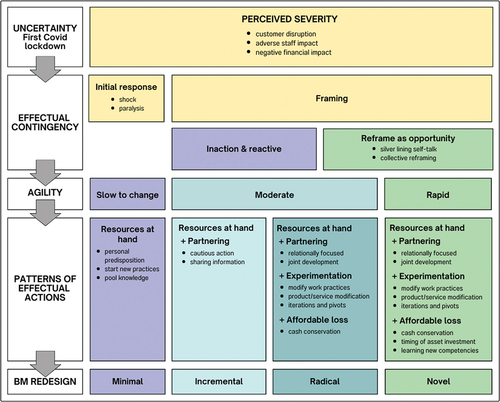

shows how effectual actions are related to BM redesign, demonstrating small firms’ adaptiveness and closeness to customers, when responding to uncertainty with effectual actions, after the cross-case analysis.

Table 6. Relating effectual action to business model redesign.

Our findings show that the effectual actions and speed of response are related to the breadth of BM reconfiguration. While most small firm decision-makers perceived the lockdown and subsequent restrictions as having a high and medium impact on their BMs due to customer and staff disruptions and negative financial impacts, shows that some effectual actions bring about a greater BM redesign than others. How firms leveraged contingencies was prevalent, particularly firms’ ability to frame and reframe the unforeseen event through silver lining self-talk and collective reframing. These actions enabled firms to initiate BM changes. While all firms acted by complying with the mandated restrictions and started with their resources at hand, differences in BM reconfigurations are related to the effectual actions of partnering, experimentation, and affordable loss.

Novel BM redesign is strongly associated with effectual actions of high degrees of partnering, experimentation, and affordable loss. Overall, these firms showed extensive evidence of iterative and continuous experimentation and BM element adaptation by changing the value proposition and value creation elements, modifying work practices, products and/or services and pivoting. Similarly affordable loss was employed through cash conservation tactics, asset investment timing and learning new competencies to enable value delivery and value capture BM changes. While firms in this group partnered through their relational embeddedness with their BM partners, industry stakeholders and communities, the joint developments they engaged in did not alter their growth trajectories. In other words, partnering and cocreation strengthened their newly embraced BM trajectory, rather than constraining it to support their partners.

Firms that radically redesigned their BMs used effectual actions to a moderate degree linked to partnering, experimentation and affordable loss. These firms experimented with modifying work practices and products and services, but in terms of iterative changes tended to seek BM stability after the lockdown and easing of restrictions. Affordable loss was dominated by cash conservation strategies and timing of asset investments, with some firms learning some competencies, but many outsourcing the online elements of their reconfigured BM architectures. A moderate degree of partnering actions were evident among this group with most firms being focused on reciprocal exchanges with partners and sharing information, while three firms partnered to jointly deliver value to their respective customers.

Examining the incremental BM reconfiguration group, the degree of effectual actions in terms of partnering, experimentation and affordable loss tended to decline. These firms only used moderate to low degrees of affordable loss and experimentation actions, while a third engaged in partnering by developing joint offerings, while the rest only engaged in some relational information sharing. These patterns suggest that effectual actions of partnering, experimentation and affordable loss are associated with the degree of BM reconfiguration, as a higher intensity of effectual actions are more strongly associated with more extensive, radical BM reconfigurations.

When examining the agility and speed of response, the findings show that rapid changes are associated with radical and adaptive BM reconfigurations, while moderate agility is linked with incremental BM changes, yet slower responses indicate a focus on survival and compliance.

Discussion

This paper sought to address why and how some small firms rapidly reconfigure their BM’s, while others wait out the storm, when crisis uncertainty radically alters existing ways of doing business. Given the analysis and findings we propose an integrative framework outlining how patterns of effectual actions relate to BM redesign during crisis uncertainty, as shown in . Taking a process perspective, our framework shows that entrepreneurs’ actions are triggered by a crisis uncertainty as they assess the severity of the uncertainty and then reflect on the contingency, moving from initial response to reframe contingencies as opportunities, where agility is related to patterns of effectual actions as they redesign their firms’ BMs.

Figure 3. Framework for patterns of effectual action and degree of business model redesign in crisis uncertainty.

The integrative framework, shown in , and findings elucidate how firms perceive the severity of an external triggering event, that mandate changes to how they conduct business, which influences how contingency is leveraged beyond prior conceptualizations that focused on flexibility as the outcome of effectual contingencies (Radziwon et al., Citation2022; Zhang & Van Burg, Citation2020). While Pacho and Mushi (Citation2021) found that the contingency principle plays a partial mediating role in the relationship between effectual resources at hand and new venture performance in Tanzania, and Nelson and Lima (Citation2020) characterized residents of Córrego d’Antas, Brazil’s actions as improvisation, their work does not explain how contingency functions under crisis conditions. Our findings show that while most firms initially experience a sudden, unpredictable change in the business environment, characterized by shock and ponder the severity of the impact of that event on their customers, staff and their firms’ financial positions, entrepreneurs with prior crisis experience tend to be able to reframe their initial responses. Entrepreneurial reframing in our study was enacted first as personal self-talk seeking out opportunities by exploring the silver lining of the contingency and second as collective reframing by persuading staff to share in and embrace the entrepreneur’s opportunity narrative. As such our study provides a more nuanced understanding of how entrepreneurs leverage effectual contingencies.

Furthermore, entrepreneurs who responded with agility to these environmental shifts through iterative actions were able to innovate their business models to a greater degree, than those who were slow to respond. Similarly, Stephan et al. (Citation2023) find that agility serves as a resilience mechanism, enabling positive adaptation to a crisis, and that entrepreneurs who combined opportunity agility with planning agility experienced higher well-being, than those who employed planning agility alone. The benefit of iterative agility enables entrepreneurs to cognitively shift their BM dominant logic. Our findings are supported by Karami et al. (Citation2022)’s study of BM innovation in frontier markets where entrepreneurs’ cognition and BM redesign actions are facilitated through proactively transforming BM elements. In this study most firms initiated changes to their value delivery architectures, due to mandated restrictions, however the degree of BM redesign was related to the pattern of effectual actions, with resources at hand shown to be a necessary, but not sufficient condition for business model redesign.

Our findings show that a higher degree of effectual actions is associated with broader BM redesign, specifically when considering patterns of partnering, experimentation, and affordable loss. Overall, firms who had an openness to outsiders, working with stakeholders in their networks and leveraging these relationships were able to jointly develop new products/services and tended to redesign the value architecture and value capture dimensions of their BMs in radical and novel ways. This is of particular interest given that Xu et al. (Citation2022) found that effectuation played a mediating role in the relationship between entrepreneurial networks and BMI in their empirical study of 408 new ventures in China, while Nelson and Lima (Citation2020) emphasize the importance of self-selected stakeholder participation to enable communities to recover from a major environmental disaster. The involvement of self-selected stakeholders and their resource contributions are well established, however studies that model effectuation dimensions as independent variables (Aggrey et al., Citation2021; Laskovaia et al., Citation2019) seem to overlook Sarasvathy’s (Citation2001) original theorization that self-selected stakeholders’ involvement also constrains future actions, especially when they become partners in codevelopment, which can constrain BM redesign to incremental or radical changes, limiting its novelty.

Our findings confirm that effectual actions of iterative experimentation and affordable loss were strongly associated with a higher degree of novel BM redesign. Consistent with findings from Björklund et al. (Citation2020) and Andries et al. (Citation2013) experimentation allows for iterative learning to occur and firms to pivot, continuously adjusting higher-order BM elements, leading to more novel BM redesign. Haneberg (Citation2021) in his empirical study of 119 Norwegian small firms find that learning and experimental behavior were closely related, while uncertainty primarily led to a focus on affordable loss, however their study did not examine BM outcomes. Our findings show that affordable loss actions such as cash conservation (bootstrapping), timing of new resource investments and learning new digital competencies support novel BM redesign, complemented with experimentation. Continuous, iterative BM adjustments enable small firms to grow their customer base.

Business model redesign is often conceptualized as changes in BM elements, as well as changes in a firm’s dominant logic (Amit & Zott, Citation2020; Foss & Saebi, Citation2017). In this study the degree of BM redesign was enabled or constrained by entrepreneurs’ dominant logic, in the way they conceptualized their firms and made resource allocation decisions to digitize BM elements, related to distribution, customer interactions, human resources and technologies, as well as the competencies developed or sourced in the process. While this study did not focus on digital business model redesign through effectuation, future research can explore agile effectuation, learning, experimentation and affordable loss for hybrid and digital BM development.

Contribution and future research

We contribute to the effectuation and BMI literature in four ways. First, we propose an integrative framework outlining how patterns of effectual action relate to BM redesign under crisis uncertainty conditions. This framework takes a process approach to effectual action and provide opportunities for future researchers to examine different types of uncertainty, how contingencies are leveraged, as well as how configurations of entrepreneurial action relate to novel outcomes and solutions. In doing so we address the call of Filser et al. (Citation2021) in building the empirical base of small firm BMI.

Second our findings extend effectuation as action, demonstrating how entrepreneurs leverage contingencies. During severe uncertainty, such as an extreme crisis, initial intrapersonal reactions reflect shock and disbelief, before framing and entrepreneurial reframing occurs, first as an intrapersonal process, and then for growing ventures, entrepreneurs tend to involve key team members. As such our study addresses the calls of Snihur et al. (Citation2022) and Thompson and Byrne (Citation2022) by linking persuasive entrepreneurial narratives as self-talk, and to influence employees. These initial responses pave the way for iterative experimentation with different BM elements, as well as affordable loss. Our findings point to these findings forming part of a small firm’s repertoire of new competencies and adaptive actions, enabling novel BM design. Small firms who partner with other firms and cocreate new products and services can draw in more resources but may also find future BM actions constrained through agreements with partners. Our findings also emphasize the critical importance of agility during extreme uncertainty for BM redesign.

Third this paper contributes to the BM process literature, showing the relevance of effectual actions for BM redesign. Specifically serial entrepreneurs, with prior crisis experience are likely to draw on these experiences and have higher levels of comfort to redesign their BMs. In addition, our findings confirm the interrelated nature of BM elements and the adjustment of dominant logic as a requirement to adapt to the dynamic, uncertain business environment. As the degree of BM redesign were explored through our multiple case study research design, we recommend future empirical research to operationalize the degree of BM redesign distinctions.

Fourth, this paper contributes to the growing body of literature on crises, confirming the relevance of effectual actions during periods of extreme uncertainty, given the analytical generalizability of case-study research design, as theory elaboration is tied to concept and theoretical generalization (Yin, Citation2018).

This study is not without its limitations. The reliance on cross-sectional data post lockdown in 2020 means the BM redesign focused on a particular time period and having longitudinal data might result in different insights related to BM redesign. However, as the focus of this study was on the emergence and dynamism of BM redesign during conditions of Knightian uncertainty, we believe a longitudinal analysis would involve differing conditions of uncertainty given how the pandemic evolved over three years. Future research would benefit from longitudinally documenting entrepreneurs’ actions and dynamics in real time. Such a research design could use a process perspective and examine the practices involved in iterative experimentation, affordable loss and partnering actions for business model redesign.

Our reliance on retrospective interview data with experienced entrepreneurs means different perspectives might have emerged if novice entrepreneurs had been included in the study. We took care to limit retrospective bias, by utilizing multiple sources of data like secondary data and online posts to ensure BM element decisions were supported by other data sources. Yet, as entrepreneurs had control over these decisions, their positions gave them unique insights and the ability to explain their actions. We invite future research to examine the performance outcomes of business model redesign under different types of uncertainty, as emerging literature points to a curvilinear relationship between uncertainty and effectuation (Cowden et al., Citation2024) and how this relationship can be moderated by firm-level variables such as entrepreneurial orientation. Furthermore, uncertainties driven by technological change, or climate shocks are likely to prove challenging for small firms in future, therefore future research should explore the value of agility compared to more gradual BM changes related to performance outcomes and how small firms use their knowledge of digital technologies, or sustainability practices to iterate and redesign BM to deliver value for future-making.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aggrey, O. K., Djan, A. K., Dei Antoh, N. A., & Tettey, L. N. (2021). “Dodging the bullet”: Are effectual managers better off in a crisis? A case of Ghanaian agricultural SMEs. Journal of Enterprising Communities: People and Places in the Global Economy, 15(5), 755–772. https://doi.org/10.1108/JEC-02-2021-0021

- Alsos, G. A., Clausen, T. H., Mauer, R., Read, S., & Sarasvathy, S. D. (2020). Effectual exchange: From entrepreneurship to the disciplines and beyond. Small Business Economics, 54(3), 605–619. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00146-9

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2010). Business model innovation: Creating value in times of change. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.1701660

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2012). Creating value through business model innovation. MIT Sloan Management Review, 53(3), 41–49.

- Amit, R., & Zott, C. (2020). Business model innovation strategy: Transformational concepts and tools for entrepreneurial leaders. John Wiley & Sons.

- Andreini, D., Bettinelli, C., Foss, N. J., & Mismetti, M. (2022). Business model innovation: A review of the process-based literature. Journal of Management & Governance, 26(4), 1089–1121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10997-021-09590-w

- Andries, P., Debackere, K., & Van Looy, B. (2013). Simultaneous experimentation as a learning strategy: Business model development under uncertainty. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 7(4), 288–310. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1170

- Antoncic, B., & Hisrich, R. D. (2001). Intrapreneurship: Construct refinement and cross-cultural validation. Journal of Business Venturing, 16(5), 495–527. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(99)00054-3

- Arend, R. J., Sarooghi, H., & Burkemper, A. C. (2015). Effectuation as ineffectual? Applying the 3E theory assessment framework to a proposed new theory of entrepreneurship. Academy of Management Review, 40(4), 630–651. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0455

- Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2020, October). Business indicators, business impacts of Covid -19. Retrieved November 14, 2020, from https://www.abs.gov.au/statistics/economy/business-indicators/business-indicators-business-impacts-covid-19/latest-release

- Barnes, R., & de Villiers Scheepers, M. J. (2018). Tackling uncertainty for journalism graduates: A model for teaching experiential entrepreneurship. Journalism Practice, 12(1), 94–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2016.1266277

- Bhowmick, S. (2011). Effectuation and the dialectic of control. Small Enterprise Research, 18(1), 51–62. https://doi.org/10.5172/ser.18.1.51

- Birks, L., & Mills, J. (2011). Grounded Theory: A practical guide. Sage.

- Björklund, T. A., Mikkonen, M., Mattila, P., & van der Marel, F. (2020). Expanding entrepreneurial solution spaces in times of crisis: Business model experimentation amongst packaged food and beverage ventures. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 14, 00197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbvi.2020.e00197

- Bock, A. J., Opsahl, T., George, G., & Gann, D. M. (2012). The effects of culture and structure on strategic flexibility during business model innovation. Journal of Management Studies, 49(2), 279–305. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2011.01030.x

- Brettel, M., Mauer, R., Engelen, A., & Küpper, D. (2012). Corporate effectuation: Entrepreneurial action and its impact on R&D project performance. Journal of Business Venturing, 27(2), 167–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2011.01.001

- British Broadcasting Corporation. (2020). Coronavirus: World faces worst recession since great depression. https://www.bbc.com/news/business-52273988

- Bullough, A., Renko, M., & Myatt, T. (2014). Danger zone entrepreneurs: The importance of resilience and self- efficacy for entrepreneurial intentions. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 38(3), 473–499. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12006

- Chandler, G. N., DeTienne, D. R., McKelvie, A., & Mumford, T. V. (2011). Causation and effectuation processes: A validation study. Journal of Business Venturing, 26(3), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2009.10.006

- Chanyasak, T., Koseoglu, M. A., King, B., & Aladag, O. F. (2022). Business model adaptation as a strategic response to crises: Navigating the Covid-19 pandemic. International Journal of Tourism Cities, 8(3), 616–635. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJTC-02-2021-0026

- Charmaz, K. (2006). Constructing grounded theory: A practical guide through qualitative analysis. Sage.

- Chesbrough, H., & Rosenbloom, R. S. (2002). The role of the business model in captur-ing value from innovation: Evidence from xerox corporation’s technology spin-off companies. Industrial and Corporate Change, 11(3), 529–555. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/11.3.529

- Christofi, M., Hadjielias, E., Mahto, R. V., Tarba, S., & Dhir, A. (2023). Owner-manager emotions and strategic responses of small family businesses to the Covid-19 pandemic. Journal of Small Business Management, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2023.2193230

- Clauss, T., Breier, M., Kraus, S., Durst, S., & Mahto, R. V. (2022). Temporary business model innovation–SMEs’ innovation response to the Covid‐19 crisis. R&D Management, 52(2), 294–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/radm.12498

- Coad, A. (2007). Testing the principle of ‘growth of the fitter’: The relationship between profits and firm growth. Structural Change and Economic Dynamics, 18(3), 370–386. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.strueco.2007.05.001

- Corbo, L., Pirolo, L., & Rodrigues, V. (2018). Business model adaptation in response to an exogenous shock: An empirical analysis of the Portuguese footwear industry. International Journal of Engineering Business Management, 10, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/1847979018772742

- Cowden, B., Karami, M., Tang, J., Ye, W., & Adomako, S. (2024). The spectrum of perceived uncertainty and entrepreneurial orientation: Impacts on effectuation. Journal of Small Business Management, 62(1), 381–414. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2022.2051179

- Cozzolino, A., Verona, G., & Rothaermel, F. T. (2018). Unpacking the disruption process: New technology, business models, and incumbent adaptation. Journal of Management Studies, 55(7), 1166–1202. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12352

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. Sage.

- Daood, A., Calluso, C., & Giustiniano, L. (2020). Unveiling the dark side of business models: A novel framework for managerial cognition and decision-making. In K. J. Sund, R. J. Galavan, & M. Bogers (Eds.), Business models and cognition: new horizons in managerial and organizational cognition (pp. 39–56). Emerald Publishing Limited, Bingley. https://doi.org/10.1108/S2397-521020200000004004

- Dequech, D. (2014). Uncertainty: A typology and refinements of existing concepts. Journal of Economic Issues, 45(3), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.2753/JEI0021-3624450306

- Doganova, L., & Eyquem-Renault, M. (2009). What do business models do? Innovation devices in technology entrepreneurship. Research Policy, 38(10), 1559–1570. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2009.08.002

- Drnevich, P. L., & West, J. (2023). Performance implications of technological uncertainty, age, and size for small businesses. Journal of Small Business Management, 61(4), 1806–1841. https://doi.org/10.1080/00472778.2020.1867733

- Eisenhardt, K. M., Gioia, D. A., & Langley, A. (2016). Theory-method packages: A comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. In Academy of Management Proceedings (pp. 12424). Academy of Management. Briarcliff Manor, NY 10510.

- Engwall, M., Kaulio, M., Karakaya, E., Miterev, M., & Berlin, D. (2021). Experimental networks for business model innovation: A way for incumbents to navigate sustainability transitions? Technovation, 108, 102330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.technovation.2021.102330

- Filser, M., Kraus, S., Breier, M., Nenova, I., & Puumalainen, K. (2021). Business model innovation: Identifying foundations and trajectories. Business Strategy and the Environment, 30(2), 891–907. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2660

- Foss, N. J., & Saebi, T. (2017). Fifteen years of research on business model innovation: How far have we come, and where should we go? Journal of Management, 43(1), 200–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206316675927

- Futterer, F., Schmidt, J., & Heidenreich, S. (2018). Effectuation or causation as the key to corporate venture success? Investigating effects of entrepreneurial behaviors on business model innovation and venture performance. Long Range Planning, 51(1), 64–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2017.06.008

- Gimenez-Fernandez, E. M., Sandulli, F. D., & Bogers, M. (2020). Unpacking liabilities of newness and smallness in innovative start-ups: Investigating the differences in innovation performance between new and older small firms. Research Policy, 49(10), 104049. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2020.104049

- Grégoire, D. A., & Cherchem, N. (2020). A structured literature review and suggestions for future effectuation research. Small Business Economics, 54(3), 621–639. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-019-00158-5