ABSTRACT

This article explores the handling of HIV/AIDS in the student community of Warwick University between 1987–1994. It investigates the perception, management, and navigation of the crisis within the context of student sexual health. The article draws on an extensive body of high-quality original research, particularly archived student newspapers, supplemented with further student union and university records deposited in the Modern Records Centre at the University of Warwick. In the absence of substantial scholarship on the interaction between HIV/AIDS and university students, this original research is essential in reconstructing a picture of how students, presumed to be sexually liberated, responded to HIV/AIDS.

This article investigates how the student community at the University of Warwick responded to the epidemic of acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) in Britain. Its aim is to explore a profoundly neglected aspect of the AIDS epidemic by shedding light on the construction, communication, and perception of sexual health within a university setting. The article also examines the effectiveness of student-led sexual health promotion aimed at preventing the spread of the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) at Warwick between 1987 until 1994. By doing so, I intend to historicise a much-needed topic regarding sexual health awareness amongst young people, so that we might be able to look forward in effective strategies for sexual health promotion today. This is highly pertinent as sexually transmitted infections (STIs) continue to occur at high rates in populations of students and other young people, with ongoing sexual health promotion similarly continuing.

Universities have long been overlooked within the histories of HIV/AIDS. Typically informed by the work of Virginia Berridge, the early historiography followed a top-down approach and divided the epidemic into four periods: policy from below (1981–1985) where self-help groups made up of predominantly gay men attempted to raise awareness and push for government action; the wartime response (1986–1987) where HIV/AIDS became the highest priority for the government; normalisation (1987–1989) which saw the image of HIV/AIDS transition from epidemic to a chronic state, akin to other manageable diseases; and finally, the ‘Repoliticisation of AIDS’ (1990–1994), where the lack of response from both government and society was challenged by activist groups. The following covers the period that Berridge has deemed the wartime response; a phase in the epidemic when the British government established HIV/AIDS as a ‘high-level national emergency, [and] as a national crisis on par with the Falklands or the Second World War’.Footnote1

Recently, the historical landscape has begun to shift. Anne Hanley has comprehensively demonstrated the various avenues that the scholarship of HIV/AIDS has taken.Footnote2 These have included works on oral histories, activism, health workers, minority groups and, pertinent to this article, young people.Footnote3 Research on the relationship between HIV/AIDS and young people has predominantly centred around sex education in schools, as opposed to university settings.Footnote4 Indeed, this approach, taken up by scholars such as Hannah Elizabeth, is understandable. The historical study of sex education and schoolchildren is telling of the broader understandings of sex, and tells historians much of societal perspectives on sexuality and insights into governmental priorities for education. Moreover, given the ongoing debates over relationship and sexuality education (RSE) in schools today, the engagement with these historical discussions is very logical.Footnote5

I argue, however, that universities and their students have an important story to tell in the histories of HIV/AIDS and sexual health more broadly. Recent work conducted by historian George Severs has gone a long way in highlighting how little attention has been directed towards understanding how university students negotiated the epidemic.Footnote6 Severs has expertly attempted to bridge this gap through his studies of Birmingham and Cambridge University. He revealed how students were politically active during the epidemic and contributed to the ‘working historical image of HIV/AIDS activism in the 1980s and 1990s’.Footnote7 With the historiographical work of the relationship between HIV/AIDS and university students still in its infancy, this article will provide a contribution to a hopefully fruitful endeavour, one that in the future will illuminate the workings and involvement of British universities and their students during the HIV/AIDS epidemic. I therefore aim to put students on the historical map and embody historian Jodi Burkett’s call to give university students legitimate historical agency; to treat them as active participants in society who make informed choices and who are a ‘part of the world in which they inhabit, not just the institution where they study’.Footnote8 Universities and their students can provide us with a unique perspective on young people’s attitudes towards not only HIV/AIDS but sexual health and sexuality more generally. Jane O’Neil has already demonstrated how the historical study of university students can offer a distinctively different understanding of sex compared to the general youth population. Students, she has argued, possess greater sexual experiences due to having ‘more opportunities for unsupervised courting and sexual activity’ than young people who live at home.Footnote9

Through the use of previously untouched student-led newspapers, primarily The Warwick Boar (The Boar hereafter), I aim to reveal that the student community at Warwick were not at all receptive to the governmental campaigns of the late 1980s that aimed at reducing the spread of HIV/AIDS. Instead, individual student agency and various student-led campaigns were created on campus in attempts to raise awareness and encourage behavioural change. After the initial upsurge in campus campaigns in 1987, however, interest and attention to HIV/AIDS and sexual health more broadly began to wane. A combination of more pressing student concerns and confusing sexual advice aided in the reduction of interest and general apathy towards sexual health.

The Boar was and continues to act as the University of Warwick’s student newspaper. Its name and form has undergone different variations including Giblet, which ran between 1965–1967, and Campus, which ran between 1967–1973, before finally becoming The Warwick Boar.Footnote10 Operating out of the Students Union (SU), the paper’s objective was to provide journalistic opportunities for students, to keep students informed, and to act as a forum for discussion. The paper published a range of articles containing information on topics such as SU elections, weekly events, student queries (such as accommodation, courses, fees etc.) advertisements, and both national and international stories. The since forgotten pages of The Boar have the potential to construct a fascinating image of the campus. They can also provide historians with an insight into student perceptions of a variety of topics, including HIV/AIDS. The first mention of HIV/AIDS, for instance, occurred in a ‘Letter to the Editor’ in March 1984.Footnote11 The anonymous author wrote in after attending a talent contest that occurred on the campus the previous Saturday. They expected that The Boar would receive a flood of complaints after a pig’s head was brought out to accompany one of the acts, and the disgruntled audience booed the individual off stage. The confused author remarked how ‘Most of us eat pork, even if it does give us the shits or even AIDS’. While this was simply a brief joke to end the author’s rant over the sensitivity of the audience, it was indicative of the fact that HIV/AIDS – whilst only two years after the death of Terrence Higgins, the first person to die an AIDS-related death in the UK – had made its way to the vernacular of some students in an isolated university in the Midlands.Footnote12

The University of Warwick is used as an example not only because of my personal affiliation, but because of its particular geographical context. As a New University founded in 1965, the 400-acre campus was built in considerable distance to city life and had, to an extent, an autonomous community who navigated their own politics.Footnote13 This makes Warwick a very interesting case study not only for understanding student sexual behaviour, but for exploring the impact of geography in student perceptions of sexual health. Furthermore, student health at Warwick received national attention through the black-comedy drama series, A Very Peculiar Practice which aired on the BBC between 1986 and 1988.Footnote14 Directed by a previous English professor who worked at Warwick, Andrew Davies, the show was set in the fictional health centre of a New University and was a satire on the political workings of universities and perceptions of health.Footnote15

This article does not aim to give an overview of the British public’s reactions to governmental campaigns, but instead will demonstrate how HIV/AIDS was interpreted by a small community of students in the Midlands. Understanding how young people received and reacted to the campaign’s messages can give us an insight into how students, presumed to be sexually liberated, managed their sexual health. This historical research is necessary for addressing current sexual health challenges. Since at least the 1960s, young people, especially those aged between 18 and 25, have been disproportionately affected by STIs. Despite various attempts to combat the increase since the 1980s, rates of STIs across the country continue to increase. In 2022, the number of gonorrhoea cases reached its highest annual figure since records began, while the number of syphilis diagnoses recorded in the same year was the largest annual number since 1948.Footnote16 The UK Health Security Agency reported that young people between 15 and 24 were both risk groups and significant contributors to this increase.Footnote17 Historicising young people and sexual health provides a lens through which to discuss and highlight previous failures at tackling the rising rates. The goal, therefore, is to showcase responses to HIV/AIDS and reactions to sexual health awareness of young people in the past, so that we can grasp the best ways to move forward today.

The article offers an original case study of a much more national and international situation, a contribution to a hopefully widening scholarship that reframes HIV/AIDS within universities and repositions students in the historiography. It tells the story of a Midland university to shed light on a previously unexplored topic in the study of HIV/AIDS. The article begins with an introduction to the University of Warwick’s Gay Society, who were instrumental in shaping and distributing early HIV/AIDS information on campus in the mid-1980s. The article then moves to exploring the university’s first AIDS Awareness Week in 1987, which constituted the year of peak interest in HIV/AIDS and discussions of sexual health, before then looking into the various fundraising activities aimed at promoting safer sex. The final section uses sex surveys conducted by The Boar to quantify whether sexual health promotion on campus led to any changes in sexual behaviour during the epidemic and the role of student societies in their attempts to regulate sexuality on campus.

The University of Warwick’s Gay Society

The study of homosexuality and universities in the twentieth century offers an interesting dynamic in understanding the difficulties of navigating policies of sex on campus. This was due to the Sexual Offences Act in 1967 which partially legalised homosexuality in private for consenting adults over the age of 21 in England and Wales. Given that the average age of those entering universities such as Warwick was below 21, homosexual acts remained illegal for the majority of students.Footnote18 Even so, gay students at Warwick, and nationally, found ways to support one another through establishing Gay Societies at university known as Gaysoc’s.Footnote19 These Societies were influenced by The Gay Liberation Front (GLF) which was founded in 1970 at the London School of Economics.Footnote20 The origins of Warwick’s Gaysoc can be traced to 1971, when a student expressed his appeal in The Boar for establishing a society to ‘exist for homosexual people to meet and get to know each other, if only to alleviate the dreadful loneliness that University life can mean to one who is never able to be himself ’.Footnote21 Historian and sociologist Jeffrey Weeks has argued that with these Societies at university ‘it became a little easier and more pleasurable to be openly gay’.Footnote22

In 1981, Warwick’s SU passed a motion committing to campaign for gay rights and liberation. The motion also made assurances of non-discrimination for gay staff and students.Footnote23Across the 1980s, the Gay and later Lesbian Society – which had split from Gaysoc in 1985 and then rejoined two years later – were one of the few SU groups who connected with the local community in the form of Bridge Nights.Footnote24 These nights were a series of discos and events designed to ‘promote realistic awareness of gay people, to break down the barriers between gay and straight people and essentially to provide a good night’s entertainment’.Footnote25 The first of these nights took place in January 1985. Members of the gay community from both within the university and the surrounding area in the Midlands were invited to come together in a safe and comfortable space to meet, socialise, and dance. These societies were active in the politics of gay life, which meant that when HIV/AIDS emerged in Britain in the early 1980s, the university had connections to information about the virus that could be filtered down to the student cohort quickly. It was for this reason that between its first mention in March 1984 until January 1987, discussions on HIV/AIDS in The Boar were led by Warwick’s Gaysoc and Lesbian Society who sought to dispel the prejudices and myths that the British press were creating.Footnote26 It was also the reason why in an executive meeting held by the SU in November 1986, it was reported that a drafted safer sex leaflet, that was due to be distributed the following January, was ‘in the hands of the Gay and Lesbian Executives’.Footnote27 These executives were clearly regarded to have some level of expertise that stemmed from their HIV/AIDS networks across the Midlands.

While it is beyond the scope of this article to draw comparisons with other universities, it is worth noting that the culture of knowledge surrounding HIV/AIDS at Warwick was distinct when compared to universities which had a medical school.Footnote28 The cultural dynamics and the health-related discussions over HIV/AIDS at universities such as Newcastle, which had a medical school, were more medically informed. At Warwick, by contrast, students needed to rely on external and more informal sources for information, such as through Bridge Nights, and thus approached health-related discussions from various disciplinary angles. Understanding these cultural differences offers valuable insights into the varying approaches universities took in addressing HIV/AIDS.

Warwick’s Wartime Response

By 1986, there had been 610 confirmed cases of AIDS in Britain.Footnote29 In a report of positive HIV cases between November 1984 and May 1987, it was found that the West Midlands had the largest number of positive results in England outside of the Greater London area.Footnote30 It was further reported that 57% of the cases in the West Midlands were from haemophiliacs, while homosexuals only represented 35%. After an emergency debate in the House of Commons in November 1986 to discuss the arrangements for a more direct and national campaign on HIV/AIDS, Norman Fowler, the Secretary of State for Health and Social Security, announced the provision of £20 million for a public health campaign, under the title of ‘Don’t Die of Ignorance’. This included a leaflet drop to twenty-three million households and a televised message in early 1987.Footnote31 For the Chief Medical Officer, Donald Acheson, this campaign was essential to ‘reduce unnecessary fears by dispelling myths and by providing accurate information’.Footnote32

Warwick quickly reacted to the government’s response and established the first AIDS Awareness Week, which took place in January 1987. The week featured lunchtime stalls, educational videos, a leaflet, and a comprehensive two-page feature on AIDS published in The Boar. The week was led by the SU’s Education and Welfare officer, T.D, who was not one to shy away from criticising the status quo and who wanted to provide students with information about HIV/AIDS in a ‘clear and unhysterical manner’.Footnote33 T.D argued that few illnesses had ever been reported with such inaccuracies, sensationalism, and lack of empathy as HIV/AIDS had. He criticised the moralistic mindsets of the government and the exaggerative attitudes of the press, pointing to the paradoxical nature of the British newspapers which aimed at reducing sexual immorality but continued to publish pornographic material on page three of their papers.

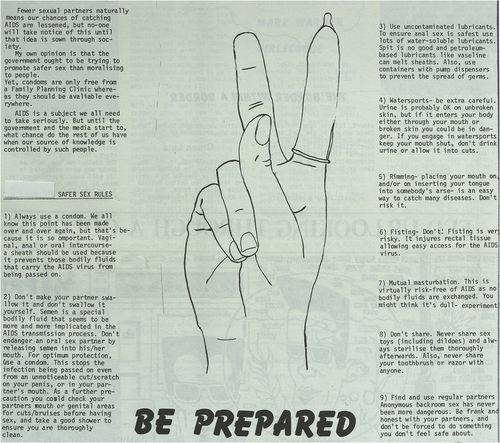

The primary objectives of the AIDS Awareness Week were to highlight that AIDS was not a gay plague and to dispel the misconception that sex was an inherently risky practice. T.D’s leaflet, titled Plain Talk, made the point that, ‘The critical factor in Aids prevention was not how many partners you had but the way a person has sex and how safely’.Footnote34 He went on to compile a nine-step list of precautionary measures for students, aptly titled his ‘Safer Sex Rules’ ().

Figure 1. Safer sex rules. Credit: The Warwick Boar. Reproduced with permission of Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick: UWA/PUB/WB/258. The name of the student has been redacted from the original image to respect privacy with no intent to misrepresent the original nature of the image.

T.D wanted to ensure that the week was taken seriously and overruled matters that he deemed insulting. For example, editors of The Boar intended on including free condoms in the issue, as had been done successfully by both Birmingham and Newcastle University.Footnote35 However, T.D rejected the idea, deeming it ‘too offensive’ and instead opted for ‘finger stools’ – protective rubber devices for cut fingers – as a supposedly light-hearted ‘gimmick’ that could effectively convey the message (illustrated in ). After The Boar refused to distribute them, T.D criticised the staff for being ‘narrow-minded, middle-class Tories’.Footnote36

While the difference between how city and campus-based universities navigated the HIV/AIDS epidemic is yet to be explored, I would suggest that due to their close proximity to the non-student population, city universities, like Birmingham and Newcastle, saw the immediate distribution of condoms as a more urgent concern. Their location exposed them to a greater risk of STIs and HIV/AIDS. In contrast, for campus universities, especially those situated in isolated areas such as Warwick, the sense of urgency was not as pronounced. Regulating sexuality and reaching the relevant audience was relatively easier when students were concentrated within a specific area, as opposed to being dispersed and entangled with the public across entire cities. The fact that Warwick was aware of other universities’ AIDS weeks was illustrative of the ways that universities connected with each other during this time. This is especially true for Warwick and Birmingham, whose close proximity made the two institutions easy allies when it came to making policies and organising events. For instance, in early November 1986, minutes from the Executive Committee stated that T.D had a ‘responsibility’ to ‘liaise with Birmingham University’ since ‘they would be running a similar week [on HIV/AIDS]’.Footnote37 The connection between the two Midland institutions offers an interesting example of the ways that universities engaged with, and were informed by, one another in their efforts to manage the epidemic.

Initially, T.D was commended for his leaflet’s blunt and crude approach. He did, as one student commented, ‘what everyone has failed to do when discussing AIDS, he made people laugh’.Footnote38 Such praise was, however, in the minority, and T.D. very quickly faced criticism on various fronts. One issue was the confusion surrounding the chosen mascot who featured on the front cover of Plain Talk - ‘The Rubber Man’ - who was a personified condom ().

Figure 2. Cover of ‘Plain Talk: AIDS’ featuring the Rubber Man (1987). Credit: The Warwick Boar. Reproduced with permission of Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick: UWA/PUB/WB/258.

One student likened the rubber man to a ‘skinned sausage’, another wrote to the paper, concerned that his penis did not have a smiling face nor any arms, and others argued that it was an attempt to ‘prove that it’s possible to pull a condom over your head’.Footnote39 Issues over the mascotisation of HIV/AIDS were not restricted to Warwick. Historian George Severs has revealed the uncertainties felt by students at the University of Birmingham towards their AIDS awareness mascot, an anthropomorphised saxophone.Footnote40 Severs argued that Birmingham’s choice pointed to how the epidemic ‘was exploited locally by those on the socially conservative right’.Footnote41 In that respect, we should assume that Warwick’s decision to present a condom was a result of their being on the more liberal left. Moreover, I would add that the decision by the University of Birmingham could have been a strategic move to avoid potential conflicts between the university’s policies and those of Birmingham City Council. In the case of Warwick, being an independent entity positioned on the border of Coventry and Warwickshire, there may have been less concern about unintentionally causing friction. Nevertheless, it is interesting that even though Warwick employed a more traditional symbol of safer sex (the condom) and Birmingham opted for an unconventional image (a saxophone), both mascots faced significant criticism from their student community.

In addition to the mascot, the content of Warwick’s leaflet was also heavily criticised. While T.D disparaged the politicisation of HIV/AIDS, the leaflet’s attack on the government led to accusations of being a ‘socialist handout’.Footnote42 Moreover, the sexual nature of the leaflet was also critiqued. One student argued that the sexual practices discussed resonated more with the homosexual community, despite the aim of presenting HIV/AIDS as everybody’s problem. As one student put it:

[T.D] tries to convince us that AIDS is not a Gay Plague, and yet his information to the majority heterosexual community is grossly inadequate. For instance his guidelines on oral sex makes no reference to cunnilingus, which is practiced far more frequently than fellatio. Are we to assume that we place condoms over our tongues?Footnote43

Interestingly then, a cause of contention at the university was not the direct supply of homosexual information but rather the absence of heterosexual information. T.D’s crude advice likely stemmed from the explicit sexual material published by organisations like the Terrence Higgins Trust (THT), who sought to appeal to the homosexual community by employing provocative language and attempting to eroticise the concept of sexual safety. In contrast, for the young heterosexual community, as historian Hannah Elizabeth has found, safe sex was emphasised as an expression of care, a manifestation of love, and as an essential aspect of pursuing monogamous relationships.Footnote44

Student Debates on the Segregation of AIDS Students

Following the mass publicization of AIDS in early 1987, discussions over the syndrome were rife on campus. One of the most contentious talks took place in February 1987 by the Warwick Law Society who debated whether ‘AIDS sufferers should be segregated from society’.Footnote45 Speaking in favour of segregation was T.P, a third-year economics student and Chairman of the Conservative and Unionist Association.Footnote46 T.P argued that since condoms were not totally effective a less voluntary method was required. For that, he proposed that ‘people afflicted with AIDS should be admitted into a separate society’ - meaning segregated from the campus.

Speaking against the motion, and in his appeal to maintain his image as Warwick’s ‘AIDS gladiator’, was Education and Welfare Officer T.D who highlighted what he understood as the ‘homophobic aspect of the anti-AIDS movement’.Footnote47 He produced a poster that had been circulating around Coventry’s public toilets titled Don’t Bend for a Friend as an example. The motion of segregation was defeated after only a 50-minute discussion, its short length a testament to the primarily liberal attitudes of Warwick students. The following week T.P defended himself in The Boar against allegations of homophobia, claiming that ‘he voted against the motion at the debate and only agreed to speak on the motion so that the debate could go ahead’.Footnote48 He clarified that he did not support the segregation of AIDS sufferers, but that this was only because of the ‘l[o]gistic impossibilities’. The absence of any belief that segregation was immoral was noted.

As historians have explored, ideas from the British far right to ‘outlaw homosexuality’ as a form of protection for heterosexuals were actively increasing from the late-1980s.Footnote49 These ideas stemmed from fears over the transmission risk of HIV/AIDS. Looking at universities offers an additional dimension to this discussion. The close living quarters that came with university life, such as shared bedrooms, shared kitchens, classes in small rooms, and more often than not only one SU bar, exacerbated fears and increased levels of risk over the spread of the virus. The University of Hull’s newspaper Hullfire, for example, carried a tombstone on its front page with the headline ‘AIDS OUTRAGE’, claiming that their SU had banned beer promotions due to student fears of the virus being passed on through vomit.Footnote50

Warwick eventually drafted a policy ‘before a situation [arose] in which discrimination occur[ed] without any chance of recourse’.Footnote51 The guidelines safeguarded students and staff by ensuring that HIV status would remain anonymous and ensured that a positive result would not lead to the removal of any students or staff from either the university or their accommodation. This goes a long way in explaining why no students were ever reported in The Boar as having HIV/AIDS. Whilst the absence of any student examples might suggest that the university was safe or not infectious, it instead reveals that the university and its reporting body upheld confidentiality and their safeguarding responsibilities.

Fundraising and the Big Rubber Ball

Despite minor far-right views, the university, for the most part, demonstrated a very liberal attitude to sexuality and sexual health. A prime example of this was the overwhelming support received during the Gay and Lesbian Week in March 1988. The associated disco event reached near capacity and raised over £150 (equivalent to £550 today) for the campaign against Section 28 – local government legislation which banned the promotion and/or teaching of homosexuality.Footnote52 The university also actively engaged in various efforts to promote sexual health awareness. For instance, half of the profits from the May Ball in 1987 were allocated to fund HIV/AIDS research.Footnote53

One of the most significant events was the ‘Big Rubber Ball’ which was organised by the SU during the AIDS Awareness Week in November 1987.Footnote54 Headlined by Bronski Beat and featuring speakers from the THT, the event aimed to promote safer sex and raise £5000 for the Trust. Free condoms were given out with every ticket purchased. This was a change from January 1987 which reflected a change in leadership: T.D assumed the position of President in September 1987, while a student called J.D took on the role of the new Education and Welfare Officer.

Similar to the coverage in January, the Union provided a feature in The Boar titled ‘Protect Yourself’ which emphasised the importance of the condom to combat HIV/AIDS and advocated that ‘good sex is safe sex’.Footnote55 The university wanted the stigma of condoms to be removed and promoted their consumption by having them on sale in the Union Shop as well as in the men and women’s toilets. The Union advised students not to be embarrassed to have conversations with their partners about sexual safety, advising them to tell their partner that ‘you’re not a pervert, but you prefer to play safe. Isn’t it better to be labelled as a bit different than be told after you morning coffee that your last evening’s partner is HIV positive’.

The feature demonstrated a significant shift in language and understandings of sexual risk from the Plain Talk leaflet. In January, the importance of not being scared to have sex was the main goal, while the feature in November openly promoted students to have sex, but in a safe and/or non-conventional way. The feature encouraged students to explore various aspects of sexuality, highlighting that ‘To enjoy sex you don’t need penetration’. The article offered suggestions ranging from erotic massages to food fantasies. This postmodern perspective regarded HIV/AIDS as a catalyst for positive change in attitudes and behaviours towards sexuality; a shift to ‘a responsible attitude’ as the article put it. One student reflected on the positive benefits that might emerge from the tragedy, asking what the future of sex would be in a society with HIV/AIDS. His answer was that:

hopefully a more responsible attitude to sex and sexuality will prevail with the consequential radical effect, in [hetero]sexual terms of a re- assessment of traditional male-female power relationships. For too long sex had been viewed exclusively in terms of male penetration. Now perhaps more emphasis will be placed on sexual activity that does not have penetration as its sole goal, a situation which involves, learning about your partners likes and dislikes, a sexuality that puts the needs and emotions of your partner above your own desires. This would be a sexual revolution I believe we could all benefit from.Footnote56

The Rubber Ball was illustrative of this shift in attitudes and of an increasing openness towards sexuality.Footnote57 The Rubber Ball was regarded as a success for being informative while enjoyable. The speakers from the THT were particularly memorable because of their safe sex simulation on stage using a cucumber and their advice to ‘suck, not fuck’.Footnote58 In an interview after the event, the members of the THT explained that they and other organisations ‘need to encourage safer sex and not attempt to frighten people away from any sexual contact’.Footnote59 Despite the overall success, the night just managed to break even with £1000 raised and ticket sales short by 900 of the anticipated 2200.Footnote60 The Boar also noted confusion over the THT’s advice on oral sex, which contradicted guidance from the Union.

The discrepancies over advice and the failing attendance at sexual health events would only get worse as the 1990s approached. This was not helped by the retirement of the university’s Chief Medical Officer of the Health Centre, Dr Dann, in December 1987. Despite the importance of health and student sexual health, the departure of Dr Dann meant that, unlike at other universities, there was no full-time Medical Officer responsible for 24-hour house calls or for undertaking medical assessments.Footnote61 Student patients of Dr Dann were advised to register with a local General Practitioner, or with the practice itself (though the Health Centre was already at its maximum capacity). With only one full-time secretary and two part-time clerical workers, Dr Dann’s absence forced the Health Centre to close over lunchtime due to the backlog of administrative work in January 1988.Footnote62 J.D criticised the university, calling their attitude towards the Health Centre staffing ‘disgusting’ and criticising their failure to intervene to help the situation.

Apparently, students had not been helping the situation at the Health Centre either. According to one nurse, ‘the students are much more demanding this year, expecting to see their doctor “here and now” without making appointments’.Footnote63 Whether the educational campaigns and initiatives that took place the previous year had led to a change in student agency towards their health is difficult to say. Nevertheless, the fact that nurses in the Health Centre noted a change in student behaviour is indicative of the fact that the year 1987 constituted a significant shift in student health.Footnote64

Students – an Apathetic Community

As the work of Virginia Berridge has identified, the immediate crisis that HIV/AIDS presented began to pass after 1988.Footnote65 From a Western perspective, HIV/AIDS was no longer distinct, but instead ‘normalised’ as a preventable chronic disease. Evidence from The Boar reflects this transition, which saw numerous articles, campaigns, and events on sexual health between 1986–1988 diminish as the 1990s approached.

Campaigns around HIV/AIDS, and sexual health more broadly, appeared to fade into the background, giving way to more topical items such as the threat to abortion rights from 1988–1990 and the safety of female students on campus from 1990.Footnote66 Despite the THT reporting that HIV/AIDS was set to be the major health problem of the 1990s, it failed to garner significant attention at Warwick. One factor that may have contributed to this shift was the formation of the AIDS Awareness Society in the first term of 1988. Their presence may have unintentionally led to the belief that HIV/AIDS and sexual health promotion was no longer an issue for the SU. To them, the formation of the society was a form of action. The lack of SU support might explain why the AIDS Awareness Week in December 1989 failed so much. The organiser of the week noted ‘a considerable lack of attendance’ and could not explain why students were so disinterested. She asked:

Is it that students are not interested in AIDS? Do they believe that they aren’t at risk? […] What I want to know, however, is what will it take to convince all students that AIDS is a threat to them.Footnote67

This disinterest highlights the challenges of sustaining the attention of the student body within the context of shifting priorities at a university.

Conflicting ideas might also explain the lack of interest. In November 1989, The Boar published a distinctly different approach to addressing safer sex, one that contrasted significantly with the Plain Talk leaflet two years earlier. According to the student journalist, the basic rule to safer sex was to avoid ‘anything that may allow one partner’s blood or semen entering the other’s blood stream’ and to remember that penetrative sex without a condom was very dangerous.Footnote68 The journalist went on to advise that ‘perfectly safe’ activities were:

mutual masturbation, hugging, kissing, fisting, using food stuffs (cream, jam etc), water sports (using urine and faeces in sex), S&M, oral sex, using sex toys (as long as they are kept clean and not shared)

Within the span of two years, what had once been described to students as definitively risky sexual practices, were now being sold as ‘perfectly safe’. The article was also highly ambiguous. While it noted that fisting did not involve the exchange of bodily fluids, it failed to discuss the potential risks such as tears and wounds or to mention the use of any type of lubricant. Further, it lacked details on what oral sex meant (i.e. oro-genital, oro-anal) and provided no guidance as to the safety of ejaculation (which T.D in 1987 previously advised against). The confusion over the messaging around safe sex may help to explain the lack of interest in these topics.

Warwick’s Sex Survey’s

This lack of interest begs the question as to whether students at Warwick perceived any risk towards HIV/AIDS. This section will reconstruct student sexual behaviour to examine whether the university’s sexual health campaigns were effective and whether they led to any tangible shifts in student sexuality during and after the peak interest of HIV/AIDS in 1987. As Berridge noted when describing policy during the epidemic, ‘Changes achieved under the impact of war often do not survive the arrival of peace’.Footnote69 Whether student sex was dramatically altered after the peak awareness surrounding HIV/AIDS in 1987 will be investigated through the use of sex surveys on campus conducted by The Boar.

Student surveys on campus were not unique to the HIV/AIDS epidemic. From as early as 1966, the student newspaper released questionnaires to find out more information about the student community.Footnote70 Across the 1980s, surveys were conducted regarding politics, education, alcohol, and sexual harassment. The latter was a particularly pertinent topic across the decade, and arose from conferences at Leeds on ‘Sexual Violence against Women’ in 1980, the establishment of the Women’s Committee to give female SU members a voice, and allegations of ‘improper conduct’ between a drama student and her lecturer in 1985.Footnote71

A specific survey on the sexual nature of Warwick students was conducted just three years before the ‘AIDS Survey’ of 1987. Its purpose was to find out whether the media’s image of the ‘liberated’ student was consistent with student sexuality.Footnote72 While its findings were not published in the newspaper (circulated separately around campus instead) it did receive some reluctance from SU officials because it was printed on Union facilities. The President of the SU was said to have a ‘Thou shalt not print attitude to the sex survey’, later stressing that he had ‘no personal objections’ but was merely cautious over rumours that The Boar intended to sell its findings to the tabloids. The reluctance to print a sex survey was not necessarily due to conservative values, but to concerns over the reputation of Warwick. The survey led to allegations of constitutional misconduct and fears over who actually had power over the student newspaper: the students or the Union executives.Footnote73 By all accounts, however, the survey was eventually printed.Footnote74

What was different about the surveys for HIV/AIDS was not only their publication within the student newspaper, but that they revealed the successes and failures of the various student-led campaigns to combat HIV/AIDS. There were no centralised attempts from the university to gather data, so it was up to the individual safer sex advocating student to go out onto the campus and ask the questions that needed to be asked. Two surveys were conducted about HIV/AIDS at the University of Warwick in 1987. The first took place in February as a part of an opinion poll on various Union policies. The sample was a random selection of 235 students who had voted in the SU elections, representing just over one-tenth of the total number of voters.Footnote75 This was out of a student population of 6,456.Footnote76 The survey reported that only 35% of the students asked felt at risk of contracting HIV/AIDS. The surveyors took this to mean that the higher proportion of students who did not feel at risk were either ‘naive or celibate’ and questioned the overall effectiveness of the government’s campaign. One student, who was disturbed by the figure, wrote the following week that if the report:

reflects the attitude of the nation’s most academically gifted youngsters, we cannot be optimistic that the less well-educated members of society will take the disease seriously either.Footnote77

The Boar concluded that HIV/AIDS had not led to a change in the sexual habits of Warwick students. One student claimed that ‘it will all die down in a couple of years and we’ll wonder what all the fuss was about’, while another expressed a ‘well you’ve got to die sometime’ attitude.Footnote78 For one student who studied between 1989 and 1996, he noted how his behaviour was affected ‘up to a point, but then I had a lot of other concerns while studying […] My main concern was getting someone pregnant’.Footnote79

The lack of perception of risk was not restricted to young people at Warwick. At Canterbury Christ Church University, for instance, a study found that undergraduates had ‘low levels of perceived vulnerability and seriousness’ and a study of 1008 young people in Dundee found that 85% thought it unlikely that they would be diagnosed with HIV within the next five years.Footnote80 As historian Matt Cook has argued, ‘It was sometimes places rather than acts that could seem infectious’, and, in the case of HIV/AIDS, London was regarded as the epicentre of the epidemic in Britain, with HIV/AIDS often viewed as a ‘gay Londoners’ disease’.Footnote81 This might go a long way in explaining the lack of perceived risk and why a twenty-year-old from Birmingham believed, ‘I don’t think we need worry ourselves about having an epidemic’.Footnote82

A second survey on HIV/AIDS was conducted in November 1987 by the female editors of Cobwebs, a feminist publication created by students from the Women’s Journal Society which ran from 1986 to November 1987. Their findings were interesting because they revealed a clear difference between male and female students, albeit on a much smaller sample of only 66 students.Footnote83 They reported similar findings to the survey in February and concluded that the government’s campaign was largely ineffective. They also stated that only 20% of the students sampled believed that they were at risk of contracting HIV/AIDS.

The survey spoke to notions of risk specifically by asking questions over potential changes to sexual habits and the use of condoms. It revealed that over 70% were not embarrassed to buy condoms and that 74% said that they thought it sensible to carry them around (although the potential discrepancy between what people say and what they actually do is worth bearing in mind). When questioned about having condomless sex with an irregular partner, nearly a quarter said that they would. The distinction between men and women was highly enlightening to the surveyors. Women represented only 5% of those who would engage in unprotected sex, while men constituted 48%. A typical response from the men was that their sexual behaviour was dependent on circumstances such as alcohol consumption, which the surveyors noted says ‘more for the effects of alcohol than for the effectiveness of AIDS campaigns’. It was argued in the newspaper that, ‘Perhaps the men in our sample were more honest than the women; perhaps women are naturally more cautious, especially those who are not on the pill, due to fears of pregnancy’.Footnote84

It is worth noting that the high percentage of condom usage in the student community might explain why some did not feel themselves at risk of contracting HIV/AIDS. By following the guidelines they perceived themselves to be safe and not at risk. We should not, therefore, necessarily take it to mean that those who felt not at risk were practicing unsafe sex. Nevertheless, the lack of awareness around sexual risk was evident in another survey conducted by The Boar which was aimed at freshers in 1994.Footnote85 It suggested that the lessons that were taught across the late 1980s were not put into practice. Speaking to the aim of the survey, the journalist said:

We’ve bought the condom, soiled the T-shirt, and been preached at about safe sex until we’re blue in the face or balls. But when push comes to proverbial shove, how much do we really know about protecting ourselves and our partners? How much do we really care?

While the number of students involved was not disclosed (whoever was available at the Union bar), the results did reveal some concerning trends. Out of those surveyed, 60% reported being sexually active, and all of them claimed to use some form of contraception. When it came to protecting themselves from STIs however, the findings were troubling. Only two out of the 50% of women on the pill also used a condom as a safeguard against STIs, and a quarter of men relied solely on their partners to take precautionary measures, not considering it necessary to protect themselves. The survey also highlighted the gender disparities in advocating safe sex. While only 5% of women refused to advocate safe sex practices the figure for men was 40%. Even for those who said that they advocated for safe sex, however, 60% said that they did not actually practice safe sex at all times. This response was primarily put down to the influence of alcohol, as had been the case in Cobwebs in 1987. Two people said that they ‘just couldn’t be arsed’ and another complained that to ‘have to stop and get something out or have a 15-minute break breaks the rhythm’.

The survey of 1994 also revealed gaps in understandings of STIs. For example, 69% of students did not know the symptoms of gonorrhoea and 56% did not know who was at risk of Hepatitis B, despite an attempted education campaign during Freshers Week. Not only did this suggest that HIV/AIDS was no longer the primary concern, it also implies that the university had still not grasped the correct manner to translate information regarding sexual health to its students. When speaking to the students’ attitudes of sexual health history the surveyors concluded that ‘We’re such a trusting lot here at Warwick’. 40% of women were unsure about their partners sexual history, while the men were far more trusting (or reckless) about their partners’ sexual past.

The HIV and AIDS Awareness Society

There can be many reasons why people may advocate for safer sex but not actually participate in it. Small scale factors such as lack of access to protection or the role of intimacy can play a role in sexual relationships. Individuals, for instance, may prioritise emotional intimacy over safety. In the case of Warwick, however, the abundance of comments about alcohol in the surveys of both 1987 and 1994 are revealing of its effects in influencing people’s sexual decision-making abilities and perceptions of risk. It is also interesting to note that four months after the safer sex campaigns in January 1987, T.D ran a ‘Stay Low’ campaign that aimed at combatting student intoxication by demonstrating the ‘evils of drink’.Footnote86 The campaign was very similar to the HIV/AIDS initiatives that he conducted, and the language he used to describe drinking was also comparable. T.D stated, ‘My intention is not to moralise … [or] ram health information down peoples throats. The intention is to make people aware of what drinking means … ’.Footnote87 As T.D pointed out, since ‘Student life is drink orientated’ then trying to change students’ risk perception can only go so far. The close proximity between the two campaigns on alcohol and sexual health was telling of their close associations.

The lack of attention, support, and knowledge of sexual health was noted by a student who in 1993 formed the HIV and AIDS Awareness Society (HAAS) – the first university in the area to have a society dedicated to the illness.Footnote88 The lack of perception of risk in the 1990s forced the creation of the HAAS to, as Virginia Berridge would describe, ‘repoliticise’ AIDS. The Society spoke to the new way of understanding HIV/AIDS, that it was ‘not about dying’ but instead showing that ‘people with HIV and AIDS have a great deal to contribute to society’, while also promoting the adoption of safer sex (please see footnote for example of HAAS literature).Footnote89

Their primary goal was to secure a stall in the Marketplace and move the information on HIV/AIDS from the biology buildings down to the main campus for general use, ensuring accessibility of sexual health material. The Society and its members were well known around campus for carrying bags of condoms to lectures and dispersing them to as many people as possible. They were active in providing advice not just about HIV/AIDS but also any questions related to sexual health. Their creation, however, likely saw the reduction in university-led initiatives as once again in the eyes of the SU the Society constituted action.

HAAS reported poor attendance at its meetings which led to concerns that students did not care about HIV/AIDS anymore.Footnote90 The president of the Society was concerned for the implications of their downfall: as the providers of free condoms at the university their absence might ‘lead to more people having unprotected sex because they don’t have a condom laying about and this leaves them open to HIV’.Footnote91

The absence of a medical school at Warwick may have contributed to the failures of the Societies who aimed at highlighting the ongoing risk of HIV/AIDS. The participation of medical students in HIV/AIDS Societies would have added a deeper understanding of the medical aspects of the epidemic, and potentially, would have led to more proactive engagement in initiatives and campaigns. It is likely that for this reason, once again, the promotion of safe sex was not well received, and the HAAS fell victim to the apathy curse of safe sex promotion in the student community at Warwick.

Conclusion

This article has explored how the students at a particular university in the Midlands perceived, managed, and navigated the HIV/AIDS epidemic. It has contributed to the growing scholarship surrounding the impact of the HIV/AIDS epidemic and university students in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Through the lens of sexual health, the material has shed light on the sexual behaviours and practices of students at the University of Warwick during this time of crisis. By understanding how students negotiated their sexual health in the past, the article has thus historicized the ways that young people perceive and handle sexual health today. Such historicization serves not only as a reflection of the past, but also as way to guide and navigate the future.Footnote92

The analysis of the previously untold story of students at the University of Warwick has revealed much about the ways in which students took responsibility and responded to sexual health initiatives. The campaigns of Warwick students in 1987 showcased their proactive stance: first, in addressing the clear problems with how the government and the British press were handling HIV/AIDS; and second, in protecting their community from a global risk. Education and Welfare Officer, T.D and his ‘Safer Sex Rules’ went a long but controversial way in managing student sexuality. However, the production of conflicting information around sexual health at the university and the ever-present role of alcohol in the student community contributed to the diminishment of perceived risk of HIV/AIDS. The decline in risk led to a decline in interest and concern about HIV/AIDS, with the situation at Warwick in agreement with Berridge’s four stages of the epidemic.

Despite this, the presence of individuals and student organisations who advocated for sexual health and who wanted to raise awareness about the ongoing risk of HIV/AIDS persisted. The historical study of Warwick has revealed an interesting dynamic. The way that students used their initiative and formed a variety of sexual health interventions ranging from safer sex leaflets, fundraising events, lectures, talks, and societies, has demonstrated that university students have an important story to tell.

Much more exploration is needed regarding the experiences of universities and other higher education institutions with HIV/AIDS. Whilst this article has provided some examples, there is a clear need for further investigation, with many more questions to be asked. Topics such as student demography, the influence of campus versus city-based universities, and the role of medical schools are just a few avenues that this evolving scholarship can explore in the future.

Disclosure Statement

The author reports there are no competing interests to declare. There was no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Joseph Price

Joseph Price is a recent graduate from the University of Warwick where he completed his masters in the History of Medicine. Joseph previously obtained a First-Class degree in History at the University of Northampton before attending Warwick. He is interested in the histories of sexuality and sexual health, particularly amongst university students in the twentieth century. He hopes to complete a PhD that focuses on the management of student sexual health at English universities following the Second World War until the turn of the twenty-first century.

Notes

1 V. Berridge, AIDS in the UK: The Making of Policy, 1981–1994 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1996), p. 7.

2 A. Hanley, ‘Histories of “A Loathsome Disease”: Sexual Health in Modern Britain,’ History Compass, 3 (2022), 1–16, (8–9).

3 G. Severs, ‘Reticence and the Queer Past’, Oral History, 1 (2020), 45–56; D. Gould, Moving Politics: Emotion and ACT UP’s Fight against AIDS (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2009).

4 H. Elizabeth, ‘Love Carefully and Without “Over-bearing Fears”: The Persuasive Power of Authenticity in Late 1980s British AIDS Education Material for Adolescents,’ Social History of Medicine, 4 (2020), 1317–1342.

5 For a history of sex education see, J. Hampshire, ‘The Politics of School Sex Education Policy in England and Wales from the 1940s to the 1960s,’ Social History of Medicine, 1 (2005), 87–105; L. Hall, ‘In Ignorance and in Knowledge: Reflections on the History of Sex Education in Britain,’ in Shaping Sexual Knowledge: A Cultural History of Sex Education in Twentieth Century Europe, ed. by Lutz Sauerteig & Roger Davidson (New York: Routledge, 2009), pp. 19–36; H. Elizabeth, ‘Private Things Affect Other People’: Grange Hill’s critique of British sex education policy in the Age of AIDS’, Twentieth Century British History, 2 (2021), 261–284.

6 G. Severs, Radical Acts: HIV/AIDS Activism in Late Twentieth-Century England (London: Bloomsbury, 2024); G. Severs, ‘HIV/AIDS Activism in England, c. 1982–1997’ (PhD diss, University of Cambridge, 2021), pp. 99–137.

7 Ibid., p. 137.

8 J. Burkett, ‘Introduction: Universities and Students in Twentieth-Century Britain and Ireland,’ in Students in Twentieth-Century Britian and Ireland, ed. by Jodi Burkett (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), pp. 1–12, (p. 7).

9 J. O’Neill, “Education not Fornication?’ Sexual Morality Among Students in Scotland, 1955–1975,’ in Students in Twentieth-Century Britian and Ireland, ed. by Jodi Burkett, pp. 77–98, (pp. 83–84).

10 For a brief point in 1988, The Boar was temporarily named Mercury but it reverted back by the end of the year.

11 Modern Records Centre, University of Warwick (MRC), UWA/PUB/WB/207/1,‘Silk Purse’, The Warwick Boar, 31, March 14, 1984, p. 14.

12 An individual had died in late 1981 of pneumocystis carinii pneumonia (PCP) in Brompton Hospital in west London, but this was before the term AIDS had been coined by the US Centre for Disease Control (CDC); see R. M. DuBois, M.A. Branthwaite, & others, ‘Primary Pneumocystis Carinii and Cytomegalovirus Infections,’ Lancet, 2 (1981), 1339.

13 The close proximity to both industry and a city played a significant role in the university’s origins. The work of Josh Patel has enlightened the relationship between Midland industrialists and the business community with the founding of the university. See, J. Patel, ‘Midlands Industrialists, Liberal Education and the Founding of the University of Warwick,’ Midland History, 2 (2023), 1–18.

14 In its book form see, A. Davies, A Very Peculiar Practice (London: Methuen, 1986).

15 Despite its uncanny likeness to Warwick, through both the buildings falling tiles and the poor reputation of the Centre’s Medical Officer in the 1970s and 1980s, Davies has continued to press that the show was not based on Warwick. See, Andrew Davies Interview at the University of Warwick, conducted by Katherine Angel (2009), <https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/arts/history/chm/outreach/shaw/info/events/davies/interview> [accessed July 25, 2023].

16 UK Health Security Agency, ‘Sexually transmitted infections and screening for chlamydia in England: 2022 report’ (June 2023) <https://www.gov.uk/government/statistics/sexually-transmitted-infections-stis-annual-data-tables/sexually-transmitted-infections-and-screening-for-chlamydia-in-england-2022-report#ref1> [accessed June 25, 2023].

17 Between 2021 and 2022, the number of new STI diagnoses in that group increased by 26.5%.

18 In 1994, the age of consent for homosexuality dropped to 18, and then to 16 in 2000.

19 The University of Essex was the first to have a branch on campus.

20 D. Malcolm, ‘A curious courage: the origins of gay rights campaigning in the National Union of Students,’ History of Education, 1 (2018), 73–86, (pp. 78–79).

21 MRC, UWA/PUB/C/5/89; ‘Gay Liberation,’ Campus, 5 November 1971, p. 3.

22 J. Weeks, Coming Out: Homosexual Politics in Britain from the Nineteenth Century to the Present (London: Quartet Books, 1990), p. 217.

23 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/167, ‘Anti-Sex,’ The Warwick Boar, 10 February 1982, p. 4.

24 The Lesbian Society comprised of around 25 members, consisting of lesbians, bisexuals, and supportive allies.

25 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/218, ‘Gay Soc,’ The Warwick Boar, 16 January 1985, p. 10.

26 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/241, an exception was ‘AIDS: Common Myths,’ The Warwick Boar, 5 February 1986, p. 7.

27 Warwick Student Union Executive Committee Minutes, 3 November 1986, Item 5:78.17.

28 The current medical school at Warwick was established in 2000.

29 Berridge, p. 1.

30 Representing 281 cases out of 4,848. See S. Winn, ‘The Developing Geography of AIDS: A Case Study of the West Midlands,’ The Royal Geographical Society, 1 (1988), 61–7, (p. 62).

31 Berridge, AIDS in the UK, p. 107.

32 E. D. Acheson, ‘AIDS: A Challenge for The Public Health,’ The Lancet, (1986), 662–6, (664).

33 Note: This article uses the initials of students to respect the privacy of those referenced in the text. MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/258, ‘A.I.D.S,’ The Warwick Boar, 21 January 1987, p. 2.

34 Ibid.

35 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/2/4/259, ‘Condoms Free,’ The Warwick Boar, 28 January 1987, p. 16.

36 Ibid.

37 The University of Warwick, Executive Committee Minutes, November 10, 1986, Item 7: 108. 8.

38 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/259, ‘Skinned Sausages?,’ The Warwick Boar, January 28, 1987, p. 6.

39 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/259, ‘Being a Rubber,’ The Warwick Boar, January 28 , 1987, p. 6.

40 Severs, ‘HIV/AIDS Activism in England,’ pp. 116–19.

41 Ibid., p. 118.

42 Phillips, ‘Skinned Sausages?’.

43 Ibid.

44 Elizabeth, ‘Love Carefully and Without ‘Over-bearing Fears,’ p. 1334.

45 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/2/4/261, ‘AIDS Segregation,’ The Warwick Boar, February 18, 1987, p. 2.

46 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/2/4/261, ‘Election Build-Up,’ The Warwick Boar, February 18, 1987, p. 10.

47 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/258, for ‘AIDS gladiator’ see, ‘Public Eye,’ The Warwick Boar, January 21, 1987, p. 3.

48 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/262, ‘Talk Back,’ The Warwick Boar, February 25, 1987, p. 2.

49 G. Severs, ‘The “obnoxious mobilised minority”: homophobia and homohysteria in the British National Party, 1982–1999,’ Gender and Education, 2 (2017), 165–81, (174–5).

50 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/261, ‘The Week According to Charters Babcock,’ The Warwick Boar, February 18,1987, p. 11.

51 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/274, ‘Protect Yourself,’ The Warwick Boar, November 26, 1987, p. 9.

52 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/283, ‘Breaking Barriers,’ The Warwick Boar, March 10, 1988, p. 9.

53 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/266, for May Ball, see ‘May Ball Anger’, The Warwick Boar¸ May 6, 1987, p. 3.

54 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/274, ‘Let’s Burn Rubber,’ The Warwick Boar, November 26, 1987, p. 2.

55 ‘Protect Yourself’.

56 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/2/4/266, ‘Condom Culture,’ The Warwick Boar, May 6, 1987, p.8.

57 Rosalind Petchesky, Sonia Corrêa, and Richard Parker were correct to argue that ‘one of the strange ironies of the HIV pandemic [is] that it has created a space for more open talk about sexuality, sexual behaviour and erotic pleasure,’ see R. Petchesky, S. Corrêa, & R. Parker, ‘Reaffirming Pleasures in a World of Dangers,’ in Routledge Handbook of Sexuality, Health, and Rights, ed. by Peter Aggleton & Richard Parker (London: Routledge, 2010), pp. 401–11, (p. 403).

58 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/275, ‘The Joy of Sex,’ The Warwick Boar, December 3, 1987, p. 3.

59 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/275, ‘The Safe Sex Theme,’ The Warwick Boar, December 3, 1987, p. 12.

60 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/276, ‘BOING,’ The Warwick Boar, December 10,1987, p. 2.

61 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/269, ‘Bye Bye Dr Dann!,’ The Warwick Boar, October 22, 1987, p. 3.

62 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/279, ‘Closure Crisis – Health Centre Shutdown,’ Mercury, January 27, 1988, p. 5.

63 Ibid.

64 The death of a student from Meningitis can also be linked to increasing concerns over health. See, ‘Meningitis Death,’ Mercury, January 20, 1988, p. 3.

65 Berridge, p. 5.

66 The Liberal MP for Liverpool, David Alton, introduced an Abortion Amendment Bill that wanted to limit the time a woman could have an abortion from 28 weeks to 18 weeks. The Bill coincided with the anniversary of the Abortion Act 1967; Safety for women students was stirred after the rape of a student outside of Tocil accommodation in the first term of 1990. MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/320, ‘Security alert,’ The Warwick Boar, October 30, 1990, p. 3.

67 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/303, ‘AIDS Awareness Week,’ The Warwick Boar, December 6, 1989, p. 5.

68 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/324, ‘Dying of Ignorance,’ The Warwick Boar, November 27, 1989, p. 12.

69 Berridge, p. 85.

70 MRC, UWA/PUB/GL/17, ‘The Giblet Survey,’ Giblet, April 27, 1966, p. 5.

71 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/139, ‘Violent Sex,’ The Warwick Boar, November 26, 1980, p. 4; MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/190; ‘Women’s Committee,’ The Warwick Boar, May 5, 1983, p. 16; MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/226, ‘Uproar as lecturer sacked over improper conduct’, The Warwick Boar, March 13, 1985, p. 1.

72 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/213, ‘Dare we print?,’ The Warwick Boar, November 14, 1984, p. 4.

73 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/213, ‘Warwick Boar Editorial,’ The Warwick Boar, November 14, 1984, p. 2.

74 Unfortunately, the survey was unrecoverable, and no discussions of it were made in the subsequent issues.

75 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/263. ‘What Students Say,’ The Warwick Boar, March 4, 1987, p. 10.

76 MRC, UWA/PUB/11/1/17, The University of Warwick, Academic Database 1986/87 (Incorporating Statement of Student Statistics), November 1986, p. 11.

77 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/264, ‘Homophobic Attitudes,’ The Warwick Boar, March 11, 1987, p. 7.

78 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/265, ‘AIDS: threat?,’ The Warwick Boar, March 18, 1987, p. 1.

79 ‘Warwick Alumni Survey Responses: Sexual Health Awareness Week’.

80 A. Memon, ‘Young People’s Knowledge, Beliefs and Attitudes about HIV/AIDS: A Review of Research,’ Health Education Research, 3 (1990), 327–35, (330).

81 M. Cook, ‘London, AIDS and the 1980s,’ in Sex, Time and Place: Queer Histories of London, c. 1850 to the Present, ed. by Simon Avery & Katherine Graham (London: Bloomsbury, 2016), pp. 49–64, (p. 52).

82 Cited in Cook, ‘London, AIDS and the 1980s,’ p. 52.

83 MRC, UWA/PUB/COB/6, ‘AIDS Survey,’ Cobwebs, November 1987, p. 5.

84 Ibid.

85 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/394, ‘Dress to impress,’ The Warwick Boar, October 18, 1994, p. 16.

86 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/266, ‘Drink Up!,’ The Warwick Boar, May 6, 1987, p. 2.

87 Ibid.

88 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/369, ‘AIDS awareness ‘not enough,’ The Warwick Boar, March 2, 1993, p. 4.

89 Warwick University Students’ Union HIV & AIDS Awareness Society. Image Credit: Wellcome Collection. < https://wellcomecollection.org/works/bkeh6c84 > [accessed August 2, 2023].

90 MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/383, ‘HIV: The Forgotten Threat?,’ The Warwick Boar, January 25, 1994, p. 9.

91 The Gaysoc (LesBiGay Society), who were the largest societies on campus, were also distributers of free condoms and did so at the LesBiGay Society Awareness Week in March 1994. See, MRC, UWA/PUB/WB/389.

92 The University of Warwick was ranked 18/24 in the Russell Group universities in a Sexual Health Report in 2015. See, ‘Warwick given “third” for sexual health,’ The Boar (February 2013) <https://theboar.org/2013/02/warwick-given-third-sexual-health/> [accessed August 29th, 2023].