ABSTRACT

Aims

To gain insight into the world of rural veterinarians during the Mycoplasma bovis incursion within southern Aotearoa New Zealand by exploring their experiences during the incursion, and to understand the consequences, positive and negative, of these experiences.

Methods

A qualitative social science research methodology, guided by the philosophical paradigm of pragmatism, was used to collect data from an information-rich sample (n = 6) of rural veterinarians from Otago and Southland. Interview and focus group techniques were used, both guided by a semi-structured interview guide. Veterinarians were asked a range of questions, including their role within the incursion; whether their involvement had any positive or negative impact for them; and their experience of conflicting demands. Analysis of the narrative data collected was guided by Braun and Clarke’s approach to reflexive thematic analysis.

Results and findings

All six participants approached agreed to participate. Analysis of the data provided an understanding of the trauma they experienced during the incursion. An overarching theme of psychological distress was underpinned by four sub-themes, with epistemic injustice and bearing witness the two sub-themes reported to be associated with the greatest experience of psychological distress. These, along with the other two identified stressors, led to the experience of moral distress, with moral residue and moral injury also experienced by some participants.

Conclusions

Eradication programmes for exotic diseases in production animals inevitably have an impact on rural veterinarians, in their role working closely with farmers. Potentially, these impacts could be positive, recognising and utilising veterinarians’ experience, skills and knowledge base. This study, however, illustrates the significant negative impacts for some rural veterinarians exposed to the recent M. bovis eradication programme in New Zealand, including experiences of moral distress and moral injury. Consequently, this eradication programme resulted in increased stress for study participants. There is a need to consider how the system addresses future exotic disease incursions to better incorporate and utilise the knowledge and skills of the expert workforce of rural veterinarians and to minimise the negative impacts on them.

Clinical relevance

To date, the experience of moral distress by rural veterinarians during exotic disease incursions has been under-reported globally and unexplored in New Zealand. The findings from this study contribute further insights to the existing limited literature and provide guidance on how to reduce the adverse experiences on rural veterinarians during future incursions.

Abbreviations

MPI: Ministry for Primary Industries; PITS: Perpetration-induced traumatic stress; PTSD: Post-traumatic stress disorder.

Introduction

Mycoplasma bovis is the most significant mycoplasma of livestock, being a principal cause of mastitis and arthritis in adult cows, and pneumonia in calves (Dudek et al. Citation2020). The disease is associated with mortality rates between 5 and 10% and morbidity rates close to 35% (Calcutt et al. Citation2018). M. bovis is transmitted via close contact and bodily fluids, particularly mucus, milk (Nicholas et al. Citation2016; Biosecurity New Zealand Citation2020) and semen (Biosecurity New Zealand Citation2019). In 2017, M. bovis was first discovered in Aotearoa New Zealand (Dudek et al. Citation2020). By January 2018 there were 23 known infected properties, and this rose to 38 by May 2018 (Biosecurity New Zealand Citation2020). The government agency responsible for biosecurity in New Zealand, the Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), was charged with managing the M. bovis outbreak. Following extensive industry consultation and in collaboration with stakeholders (DairyNZ, Federated Farmers, Beef and Lamb NZ), MPI announced in May 2018 that they would attempt to eradicate the disease from the country. This was a globally unique response to the management of this disease, making New Zealand the only country to attempt its eradication (Biosecurity New Zealand Citation2020).

Previous studies and reports exploring the impact of exotic incursions from the UK and Australia have largely focused on the management of the outbreak and its impact on farmers and farming communities (Environment and Natural Resources Committee Citation2000; Anderson Citation2001; Convery et al. Citation2008). Understanding of the experience of rural production animal veterinarians with biosecurity incursions is limited, yet their expertise is critical to the management of such incursions.

Agriculture is one of New Zealand’s primary production and export industries (Statistics New Zealand Citation2019) and rural clinical veterinarians provide vital support for the sector. This support encompasses not only animal health and welfare but also food quality, food security and biosecurity, thereby ensuring a safe, secure and nutritious food supply to consumers (Caceres Citation2012). Their position within rural communities makes veterinarians a fundamental source of support to farmers, with many veterinarians becoming the farmer’s “critical friend” (Remnant Citation2020).

Relatively “high rates of poor mental wellbeing” have been reported for veterinarians (Bartram et al. Citation2009a), strongly associated with work-related stressors. Known stressors include long working hours; concerns associated with maintenance of skills and knowledge; relationships with peers, managers and clients; lack of resources; high levels of job complexity (Bartram et al. Citation2009b); performing euthanasia of healthy animals; health; finances; career paths; constant exposure to death (of animals) (Bartram and Baldwin Citation2010); animal welfare issues (Hansen and Østerås Citation2019); grief of bereaved owners (Dow et al. Citation2019); and maintaining a work–life balance (O’Connor Citation2019). Further confounding this multitude of stressors is the complicated ethical structure veterinarians are embedded in, with responsibilities to animals, animal owners (clients), their peers and colleagues, and society as a whole (Durnberger Citation2020). This is particularly true of farm veterinarians who have to work within a very complex moral landscape due to society’s changing values and expectations – particularly the ethics of human/animal relationships, and of food production generally (Durnberger Citation2020). Despite working within such a stressful environment, veterinarians are recognised as being reluctant to seek help (Dow et al. Citation2019), perhaps because of perceived stigma associated with mental health issues in their profession (Cardwell and Lewis Citation2019), or within rural communities (Robinson et al. Citation2012). The scarcity of mental health services within rural communities does nothing to alleviate the issue (Jaye et al. Citation2022).

Morally challenging situations for farm veterinarians are associated with many factors; indeed, veterinarians tend to describe their role in a multifactorial fashion (Durnberger Citation2020), and these roles provide multiple opportunities for obligatory and/or moral conflict (Moses et al. Citation2018). If morally conflicting situations are not resolved then psychological distress is experienced, an experience known as moral distress (Durnberger Citation2020). Moral distress is, therefore, already a reality within everyday veterinary practice (Batchelor and McKeegan Citation2012; Moses et al. Citation2018; Durnberger Citation2020). The need for action to improve veterinarian wellbeing has previously been highlighted in New Zealand with a call for an evaluation of wellbeing initiatives within the veterinary profession (Moir and Van den Brink Citation2020). However, moral distress is currently poorly recognised and understood within the veterinary profession.

The following section provides an overview of moral distress as an explanatory framework, before examining moral distress within the veterinary profession. The provision of this theoretical information in the Introduction provides the reader with an articulated signpost or lens for how the researchers began to understand the narratives of the veterinary participants.

Theories of moral distress, and moral distress in the veterinary profession

The concept of moral distress was first described in 1984 (Jameton Citation1984) and was defined as occurring when a nurse felt constrained from behaving in a way that aligned with their moral values in the course of their work. Feelings of frustration and anger are frequently associated with moral distress (Epstein and Delgado Citation2010), as is a sense of feeling belittled, impotent, unimportant, or unintelligent (Epstein and Delgado Citation2010; Arbe Montoya et al. Citation2019).

Since this original attempt to articulate the concept there have been multiple redefinitions. Recently, Morley and colleagues (Citation2019) determined which conditions were necessary and sufficient for moral distress to occur. They concluded that the necessary and sufficient conditions were the combination of a moral event occurring, the feeling of psychological distress, and a direct causal relation between these two conditions (Morley et al. Citation2019). Ultimately, moral distress results from feelings of powerlessness and loss of agency when individuals have seriously compromised themselves or allowed themselves to be compromised (Bennett and Chamberlin Citation2013).

Morally distressing events can take many guises; however, when a person’s knowledge is ignored or belittled, they are exposed to an epistemic injustice. Epistemic injustice is recognised as having the potential to result in a morally distressing experience (Morley et al. Citation2019). Frequently, the individual has not been part of a decision-making process but has to convey and perform decisions made by others, losing their ability to act as an independent moral agent (Morley et al. Citation2019).

Fricker (Citation2007) argues the case for two forms of epistemic injustice: testimonial and hermeneutical. Prejudices about a speaker associated with their gender, ethnicity, social background, accent, or job can result in more or less credibility given to a statement they make, resulting in testimonial injustice (Fricker Citation2007). Hermeneutical injustice can follow on from testimonial injustice when what is included in a shared pool of knowledge is influenced by testimonial injustices. Consequently, experiencing testimonial and hermeneutical injustice leaves an individual unable to make sense of their experiences (Byskov Citation2021).

Byskov (Citation2021) identified five conditions that make an epistemic injustice an injustice, with the first two, disadvantage and prejudice, evolving from Fricker’s (Citation2007) arguments. The remaining three conditions, stakeholder, epistemic and social justice, were distinguished by Byskov. The first of these contends that for someone to be unjustifiably discriminated against as a knower, they must in some way be affected by the decisions they were excluded from influencing. The second, epistemic, requires that the knower possesses relevant knowledge about the subject being discussed, but is excluded. Finally, the social justice condition relates to wider structural injustices, such as racism.

Veterinarians can experience epistemic injustice on multiple levels through being at a disadvantage due to their gender, ethnicity or subordinate position, and as such can be exposed to epistemic injustice in the sometimes hierarchical nature of veterinary businesses (Kwok Citation2020). Veterinarians, however, can also find themselves in a disadvantaged position in relation to the state. In a study examining the history of control of bovine tuberculosis in New Zealand, Enticott (Citation2016) noted the authoritarian attitude of the Department of Agriculture, regarding the use of the caudal fold test to detect bovine tuberculosis. This insight was highlighted in the report by Anderson (Citation2001) into the foot and mouth disease outbreak in the UK, which noted that the government failed to realise its inability to defeat an outbreak of an animal disease in isolation. Anderson’s list of major lessons learned included two which were also included in a briefing paper presented recently by the authors of this article to the New Zealand Minister of Agriculture in May 2021: be prepared, and respect local knowledge (Doolan-Noble et al. Citation2021).

Exposure to morally conflicting experiences can have short- and long-term negative consequences on mental health. Short-term consequences include emotional distress (e.g. anger and frustration), with repeated exposure to morally distressing conditions having the potential to ultimately lead to a person being burdened by moral residue. Moral residue as a construct is distinct from, yet related to, moral distress and is a consequence of lingering distress (Epstein and Delgado Citation2010).

Along with the potential for moral residue, repeated exposure to morally distressing situations can lead to moral injury. Moral injuries, however, are thought of as an existential rather than a psychological problem (Jinkerson Citation2016). For example, moral injury can occur when individuals bear witness to or fail to prevent an act that transgresses their deeply held moral beliefs (Dean et al. Citation2019) and is frequently associated with a sense of betrayal due to organisational or leadership mismanagement (Riedel et al. Citation2022). The negative consequences of moral injury over the longer term include withdrawal of self, unsafe or poor quality of care, decreasing job satisfaction and job attrition (Pauly et al. Citation2012).

Most studies exploring the consequences of exposure to morally distressing experiences have looked at the impact on armed forces personnel and nurses (Williamson et al. Citation2018). One systematic review and meta-analysis (Williamson et al. Citation2018) did include a paper on veterinarians (Crane et al. Citation2015). This showed a significant relationship between a morally injurious experience and anxiety, and a significant negative association between a morally injurious experience and resilience, with a corresponding positive association with self-reported symptoms of stress (Crane et al. Citation2015).

The phrase perpetration-induced traumatic stress (PITS) is less familiar than post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). PITS, however, has been identified in those who participate in the killing of healthy animals, for example during a cull (Whiting and Marion Citation2011). The causal facets of PITS in veterinary work differ from classical PTSD. While the life of the veterinarian is not directly threatened by the killing of animals, their professional identity and morality is (Whiting and Marion Citation2011; Dean et al. Citation2019). Ultimately, moral injury does not reflect a broken individual; the source of distress resides within a broken system (Čartolovni et al. Citation2021). Potential solutions, therefore, should not focus on promoting resilience or mindfulness within clinicians but in creating a system that acknowledges and values the knowledge, skills and understanding that veterinarians possess (Dean et al. Citation2019).

A recent UK study by Batchelor and colleagues (Citation2015) identified that practising veterinarians may not gain the moral reasoning skills required to meet the demands of such an ethically challenging job during their professional education. Unlike human medicine, where clinical ethics support services have long been established and medical ethics taught within medical curricula, veterinary medical ethics committees or veterinary medical ethicists to support veterinarians navigate the complexities of everyday practice are uncommon (Long et al. Citation2021).

The opportunities for production animal veterinarians to have morally distressing experiences has already been outlined. Furthermore, the wider project from which the present study stems has already found moral distress to be associated with the M. bovis outbreak and its management (Boyce et al. Citation2021; Jaye et al. Citation2021).

Consequently, this study explores the experiences of rural clinical veterinarians impacted by the management of the M. bovis incursion in southern New Zealand, with a specific focus on the challenges of their involvement and the emotional and social consequences of the experience.

Methods

This study sits within a broader research project that sought to gain an understanding of the psychosocial impact of the M. bovis incursion across a variety of populations within rural communities, not just veterinarians. We also interviewed farmers and their families, incursion support workers and representatives from key rural organisations. The overall timeframe for the study was January 2019–October 2021. In addition, a content analysis of media coverage, national and rural, of the incursion between 25 July 2017 and 31 July 2019 was completed to gain an understanding of the distributed knowledge associated with the incursion (Boyce et al. Citation2021).

The study was guided by the philosophical paradigm of pragmatism. Pragmatist epistemology embraces the view that knowledge is always based on experiences, making this philosophical approach ideally suited to the present research, with its aim of capturing the experiences of rural clinical veterinarians who were involved in the incursion (Goldkuhl Citation2012).

The qualitative social science methodological approach used was compatible with this paradigm. A full description of the project’s methodology, including the establishment and membership of a stakeholder panel and governance group has been reported elsewhere (Jaye et al. Citation2021). The opportunity to work with stakeholders and governance group members in relation to the study design, participant recruitment and resolution of associated study challenges, are features that characterise a pragmatic approach (Biesta Citation2010).

For the veterinarian component of the study, a generic purposive sampling frame was used. Purposive sampling is an extensively used sampling strategy in qualitative research, enabling the identification and selection of information-rich cases (individuals) related to the phenomenon of interest (Palinkas et al. Citation2015). Veterinarian participants were identified through the regional veterinarian representative on the stakeholder panel. The size of the sample required to inform the study aim was not determined a priori as this is recognised as inherently problematic in qualitative research (Sim et al. Citation2018). To be included in the study, veterinarians were required to fulfil the following criteria: have been impacted by the M. bovis incursion in terms of having clients affected directly; be working in a practice in southern New Zealand; be working as either a farm or mixed animal veterinarian in a clinical practice setting; and to be able to understand and answer questions in English. It should be noted that veterinarians were not eligible to participate if they had worked with farmers but did not have a primarily clinical role or farmers as commercial clients. No incentives were offered to veterinarians to participate in this study.

Pragmatism is a permissive approach, encouraging researchers to use theoretical and explanatory tools, and research designs best suited to answering their specific research questions. In this study, qualitative techniques, namely semi-structured interviews and focus groups were used (Green and Thorogood Citation2014). This design was consistent with the interpretivist (Guba and Lincoln Citation1994) framing of the project and our overarching aim to understand participants’ perspectives and reflections on their experiences of the M. bovis incursion.

Both the interviews and the focus group took place during November and December 2019 and were guided by a schedule of open-ended questions that formed part of a questionnaire manual developed to guide the study interviews and focus groups. The questionnaire manual was a collaborative effort between the research team, the stakeholder panel and governance group (Jaye et al. Citation2021). Questions were used flexibly, enabling participants to freely share their experiences, with the interviewer using prompts if required (see Supplementary Information 1). Interviews and the focus group were facilitated by authors FD-N and GN, neither of whom had any relationship with participants. Both interviews and the focus group were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Participants were offered the opportunity to validate their transcripts. All transcripts were cleaned of identifying data by GN prior to data analysis.

Data collection ceased when the researchers considered that the data collected provided conceptual depth to the phenomenon being explored (Braun and Clarke Citation2021). The exploration of the data was guided by Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2020) approach to reflexive thematic analysis, comprising six phases: familiarisation with the data; generation of initial codes; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes; and producing the report. In this study the research team members individually acquainted themselves with the anonymised narratives, examining the data and developing codes, which were further consolidated prior to the first of a series of team meetings used to deliberate each researcher’s codes. The team’s ability to meet frequently, either in person or online, and reflect on their understanding of the narrative data, resulted in further refinement of their comprehension of the narratives collected (Braun and Clarke Citation2020). Furthermore, this enabled them to move beyond a superficial understanding of the data to being able to construct themes that were meaning-based and interpret the stories within the data narratives (Braun and Clarke Citation2022).

Ethical permission for this study was provided by the Human Research Ethics Committee at the University of Otago, Dunedin, Aotearoa New Zealand (HE19/004), and the authors declare no competing interests in relation to this study.

Results

All the veterinarians approached by the veterinary representative on the stakeholder panel to be part of this purposive sample agreed to participate. In total, two individual interviews and a four-person focus group took place face-to-face, as all were conducted prior to Covid-19 restrictions. provides an overview of some of the associated characteristics of the participants.

Table 1. Characteristics of participants in a qualitative study carried out during November and December 2019, of the experiences of rural veterinarians with the outbreak of Mycoplasma bovis in southern Aotearoa New Zealand.

Findings

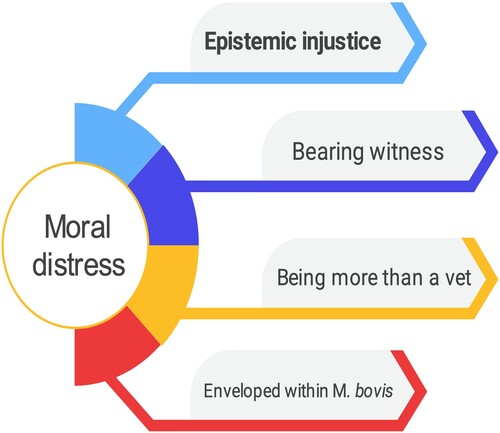

This section introduces the researchers’ understanding of veterinary participants’ experiences, derived from the analysis of the narrative data. The overarching theme, moral distress, with four related sub-themes, encapsulated the synthesis of the experiences of participating veterinarians (). The sub-themes all relate to psychological stressors, and all contributed to the overall theme of moral distress. The most significant psychological stressors were epistemic injustice and bearing witness. Along with another two identified stressors, these led to the experience of moral distress in participating veterinarians.

Figure 1. Overview of over-arching theme: moral distress and associated psychological stressors identified within the collected narratives of veterinarians (n = 6) involved in the outbreak of Mycoplasma bovis in Aotearoa New Zealand that commenced in 2017 and is ongoing at time of publication.

For participating veterinarians, psychological stress associated with the M. bovis incursion resulted from having their knowledge either considered irrelevant or, potentially, ignored; having to witness the adverse treatment of both their human clients and their animal patients; or having to expand their roles and experiencing the ingress of their roles into other aspects of their lives. Ultimately, the effect of these stressors was manifest in the ways these veterinarians articulated and demonstrated the impact on themselves. In the next section each of the psychological stressors is described and illustrated by excerpts from the veterinarians’ accounts.

Epistemic injustice

One major contributing component to the moral distress described by participants was epistemic injustice, their experiences of which fulfilled the stakeholder and epistemic conditions described by Byskov (Citation2021).

The stakeholder condition refers to the individual as a key potential participant in the process. Despite having the knowledge to meaningfully contribute to the management of this incursion both (particularly) locally and (occasionally) nationally, participating veterinarians described being unjustifiably marginalised as a group of knowers. A key area of exclusion related to MPI not informing clients’ own veterinarians about their animals’ disease status, or the necessary actions required in relation to the animals, or providing the information they sought about test results, as illustrated by the following quote.

Well, the vets that are involved with large animal production, it’s a really stressful period and not having answers, we are used to having answers. And the veterinary profession on the whole was, we’re really excluded from the diagnostic tree. We haven’t been involved at all. (Vet 1)

It is impossible to manage in a crisis without information, and because these veterinarians described being purposefully excluded from knowing the test results of their clients’ cattle, they felt unable to appropriately support their clients.

For the second (epistemic) condition to be met, an individual must possess knowledge that is relevant to the decision they are excluded from. Participants described experiences of this form of active marginalisation. They interpreted this as an attempt by MPI to exclude and prevent their knowledge from informing not only the incursion management process but also a greater understanding of the disease itself.

It’s been delayed and poorly planned, and we were sitting here with the resources available hoping that they’d just say, “Right. You guys go out and test all these farms for us and get that sorted. Tick off the list those and everything like that.” They didn’t, we had lots of systems in place that they haven’t utilised them as far as scheduling and farm areas and planning the day and all that kind of thing. (Vet, FG)

Vet: … so the farmer I worked with, two of his farms showed clinical mastitis … showed clinical Mycoplasma bovis mastitis and there’s only been a handful of farms in New Zealand that have showed disease. And that’s worldwide too. Just because your blood test is positive, doesn’t mean to say that you will show disease.

Interviewer: So it’s (commonly) asymptomatic?

Vet: It’s (commonly) asymptomatic yes. So, the reason why this farm was so important to New Zealand’s agriculture is that it showed disease … but MPI were not interested in clinical disease. (Vet 1)

These veterinarians reported having access to disease data processes, resources, skills and/or knowledge that could have contributed to and benefited the response to the incursion in multiple ways, thereby adding value to the national eradication programme, and to the farmers affected, but reported that their offers of help were not actioned. They described the reporting of tests on suspected infected cattle as very slow, unlike the typical reporting processes farmers were used to their veterinarians providing. In some instances, participants reported that MPI discouraged farmers from bringing their own veterinarians to meetings, yet rural veterinarians can have very strong and trusted relationships with farmers (Enticott et al. Citation2011), and they can play an important role as knowledge brokers between veterinary science and farm practice (Enticott et al. Citation2011). In addition, farmers’ own veterinarians are familiar with their herds. Therefore, it is understandable that farmers would want their veterinarian present at meetings, yet veterinarians often encountered situations where they felt that MPI deliberately attempted to shut them out.

Participants described being in a position of disadvantage and therefore unable to influence the epistemic discourse (testimonial injustice). These veterinarians experienced disadvantage at multiple levels in relation to contributing to the epistemic discourse.

On a personal level, veterinarians described their knowledge of the farming calendar and the local geography that influences the farming calendar going unheeded by the bureaucracy of state, MPI, as the following quote describes.

But a farmer that was put on [an] RP, restricted place [a notice served to an infected farm to apply controls]. And they were looking for options to winter their cows, and for this to happen they needed to put a proposal forward. And that was through the [MPI] operations team, who then had to get approval from the legal team, who had to get approval from the epidemiology team. And it would get through those processes and one team would say no, and then 3 weeks later we’d get an answer saying no. So we’d come up with a new proposal, and 3 weeks later they’d come back with an answer with no. (Vet, FG)

In Southland and Otago local veterinarians were keen to support the eradication programme by providing access to additional skilled staff, however, they failed to secure engagement from the government agency, as demonstrated in the quote below.

Vet 1: They [MPI] were in chaos and we were just in there. We … we were like, “We’ve got these technicians.” We’ve offered them to them. “We’ve got 20 people that can be doing this, this and this. And this, we can knock this out.” (Vet, FG)

Interviewer: So it wasn’t like you had a whole lot of things you had to do for them, it was just like, “We don’t want to talk to you.”

Vet 2: Basically. They didn’t say we don’t want to talk to you. They just didn’t talk to us. (Vet, FG)

At a more national level, communicating with MPI’s national office was described as stressful, as expressed below.

Emailing, communicating with MPI was the most stressful time. Because they didn’t give you any answers. Their answers, you wouldn’t want to read some of the emails. They just didn’t release information. I don’t think they have a policy around it. (Vet, 1)

Epistemic injustice was a significant component contributing to the moral distress experienced by participants. In the following section we turn to the moral distress caused by bearing witness to the suffering of both livestock and farmer clients.

Bearing witness

Participating veterinarians observed both human and animal suffering related not to the disease itself, but to the management of the incursion. In terms of human suffering, this was associated with observing the mental stress experienced by their clients who were impacted by M. bovis, as the quotes below show.

That was the most stressful thing. That was one of the most stressful things for the farmers, not being told results … And they’re used to being told the results and if you’ve got a two or three or four million (dollar) mortgage, you’d like to know what’s going on. (Vet 1)

He’s a very compassionate, motivated dairy farmer who loves cows and that was horrendously difficult for him [seeing his cows trucked out]. (Vet 1)

Particularly frustrating to participants (as for farmers: Jaye et al. Citation2021; Noller et al. Citation2022) was the difficulty in alignment between the farming calendar and practices in eradication programme processes.

… and people that had no idea of the industry, when a calf was weaned, when a cow was dried off. The gestation period of a cow. The [government] compensation guy couldn’t tell us when a calf was weaned, and all these calves were destined for slaughter. (Vet 1)

Of MPI reacting to that and then finally in April and May discovering, “Oh yeah so in first of June is when some farms change hands and stock go off. Right, we should actually have something in place.” Well, it should have been done in March. So, a lack of understanding probably. (Vet 2)

For one veterinarian, human and animal suffering combined, potentiating the magnitude of moral distress experienced, as the following excerpt describes:

So one part of MPI were asking me to write this certificate so they [heavily pregnant cows] can get (transported to be) killed. The other side of MPI, which looks at the transport certificate, I rang them and they said if a cow calves while being transported or while they are at the slaughter house, basically I will throw you under the bus; that you will be, go up to the Vet Council for incorrectly certifying an animal. Now then I was stuck between the situation of the farmer really wanted these animals to die because these cows were calving down on the grazing platform [Note: farmers were not permitted to move these cattle back to the main property] where there’s no place to milk them and so they were getting mastitis, not being fed properly, calving in really shit conditions. The welfare was horrendous for these animals, and I wanted these animals to die as soon as possible because of the welfare issues and to help the farmer out cause he didn’t know what to do with these cows. And then MPI telling me to certify them and then they’re also saying I’m going to be thrown under the bus if something goes wrong. And for something for me, which is very … well, it’s near on impossible to tell if an animal’s going to calve in the next 48 hours. I tried my best. (Vet, FG)

The above excerpt highlights the conflicts experienced by veterinarians in attempting to procure the best outcome for stock scheduled for destruction.

Participating veterinarians bore witness to suffering – human or animal or both – that transgressed their moral compass, resulting in additional moral distress. Next we move to the experience of being enveloped within the M. bovis incursion.

Enveloped within the incursion

A further contributor to moral distress for participating veterinarians was that M. bovis was inescapable. Not only did the incursion demand the attention of veterinarians but they also had to meet the demands of MPI, and farmers and their livestock, as well. For veterinarians the experience was emotionally draining as their strong locus of responsibility for their clients was activated, as the following quotes demonstrate.

So, over the next 4 or 5 months, I sat through 23 MPI meetings with the farmer. I went through the whole, all the way through the whole process from day one to the day [his herd] was slaughtered. (Vet 1)

A lot of the extra work I did in my own time. The reports required, compensation queries for fights the farmers had down the line. We had the information and so it was a matter of putting a signature to various reports, and making plans, and helping them with their compensation paperwork. Yeah. Outside your normal duties. It did impact your work and out of work. (Vet, FG)

Participants described how M. bovis took over their lives, with certain times causing additional stress, such as the announcement of the incursion in July 2017 and the notice of the intent to eradicate it in mid-2018.

Critically, local veterinarians were being used by farmers as “knowers,” as sources of knowledge; and veterinarians were providing knowledge and support as best they could. However, meeting these needs added to participants’ already heavy clinical workload. Attending to the needs of MPI, farmers and stock took an enormous toll on their personal lives. Feeling they were unable to satisfy the needs of all the actors adequately, because of the magnitude of the outbreak and what was at stake (livelihoods, personal and professional relationships, and animal lives), all contributed to participants’ experiencing moral distress. For example:

So that was to the ICP [incident control point] manager who got in touch with his manager, but then even they didn’t know who to take it to. There was a lot of knowledge, a gap of knowledge of the people. “Oh, I don’t know what to do in this situation.” And a lot of the time it was just left at that. And we’re going, Well, okay. What do we do? (Vet, FG)

The strong locus of responsibility participants had for their farmers and their stock, leads to the fourth critical theme, “being much more than a vet.”

Being much more than a vet

During the incursion, veterinarians found themselves more frequently undertaking roles and functions well beyond their veterinarian role. Participants spoke of assisting farmers with form filling and report writing; lending themselves as a sympathetic ear and being a support person; a knowledge-gap “filler,” as well as a counsellor. While participants recognised their clients’ needs and acted in this brokering role, meeting these needs was another major contributor to moral distress. The following excerpts illustrate the supplementary roles undertaken by participants.

I spent nights out with them because they had to fill out forms and reports and some of the information, I could give them straight away from the records we had here. (Vet 1)

And yeah, I guess probably a lot of it is counselling services for the farm that was affected. (Vet, FG)

The culmination of these experiences amplified feelings of moral distress and left veterinarians with lingering feelings of anxiety about the future.

And the long-lasting impact on, at the time, not being able to do as much as we wanted. They’ll [colleagues] worry about that in the future as well, some of our team members. Like the clients and their animals, and I guess just the what if it was to happen again? And that’s changed now because we’ve been through one incursion. They’ll be concerned, a long-lasting concern about that in the future. (Vet, FG)

Participating veterinarians experienced a variety of psychological stressors, over and above those associated with the day-to-day work of veterinary practice. The experience of epistemic injustice was keenly felt and while veterinarians often witness suffering in their normal roles, the occurrence and intensity of human and animal hardship witnessed during this incursion response was difficult to bear. Furthermore, the M. bovis incursion and its impacts were demanding, invading all aspects of their lives. The additional roles veterinarians consider they have outside of their traditional professional role, such as counsellor, became more apparent and onerous during this time. Within the narratives, the presence of moral distress was evident through the outward expression of frustration, vulnerability, uncertainty, constraint, marginalisation and exclusion. In addition, moral distress was demonstrated physically during interviews and the focus group through some participants’ emotional responses (e.g. weeping). Moral distress resulted in expressions of anxiety, with its links to both personal and professional negative consequences.

Discussion

To our knowledge this study is the first from New Zealand to report the experiences of rural clinical veterinarians impacted by an exotic disease incursion (M. bovis) response. Furthermore, we believe this is the first study to highlight how the detrimental experiences of these veterinarians contributed significantly to their experiences of moral distress, moral residue and injury. It is possible that the negative impact on veterinarians exposed to the incursion and its management will remain, with the potential to be damaging to the veterinarian and their career, especially if they continue to be exposed to morally distressing episodes (Epstein and Delgado Citation2010). The potential for further moral distress is important to recognise as MPI works to engage and develop capability for further incursions with rural veterinarians, as proposed by the three independent reviews (Paskin Citation2019; Office of the Chief Science Adviser Citation2019; Shadbolt et al. Citation2021).

For these veterinarians the experience of epistemic injustice was arguably as important in their lives as was the incursion. The conditions that underpinned these experiences related to participants being excluded and discriminated against in their position as “knower” as described by Fricker (Citation2007) and Byskov (Citation2021). Their disadvantaged situation was driven by two factors. Firstly, they were geographically distant and thus peripheral to the decision-making at the bureaucratic hub (Wellington). Secondly, their situated and professional expertise was not recognised by decision-makers.

Despite potentially being key stakeholders in supporting the management of the incursion response, through their local relationships, understanding and resources, participating veterinarians were excluded both from being informed about their clients’ situation and from the decision-making processes. Left feeling disempowered and inconsequential, they were still required to meet government directives when asked. As a result, they ceased to be independent moral agents (Morley et al. Citation2019). Enticott (Citation2016) has previously highlighted this paternalistic manner of the state in relation to disease control and the epistemic injustice dispensed by the former Department of Agriculture to veterinarians and farmers. In their approach to the management of the M. bovis incursion, MPI’s response reflects the earlier strategy of the former Department, resulting in limited engagement with local participating veterinarians. MPI’s failure to engage with local veterinarians in affected regions, however, is not a new finding, having been described in earlier reports examining MPI’s performance in managing the eradication programme (Paskin Citation2019; Office of the Chief Science Adviser Citation2019; Shadbolt et al. Citation2021).

Empirical research on veterinarians’ experiences of moral distress within normal clinical practice is limited but growing (Fawcett and Mullan Citation2018; Moses et al. Citation2018; Durnberger Citation2020). This study draws attention to the potential for veterinarians in New Zealand to experience additional morally injurious experiences when involved with the management of an exotic disease incursion. The narratives of these participating veterinarians contained frequent references to emotions associated with moral distress (Morley et al. Citation2022; Simonovich et al. Citation2022): frustration regarding the lack of knowledge of decision makers about the farming calendar and animal husbandry; stress when trying to engage with authorities; uncertainty regarding multiple aspects of the management process, such as blood test results; and long-lasting concern about future events (anxiety).

Professionally, veterinarians are recognised as being at elevated risk for behavioural health issues when they are involved with disaster responses, including animal disease disaster management involving depopulation (Vroegindewey and Kertis Citation2021). The impact of an additional stressor on rural clinical veterinarians, such as animal disease disaster management, needs to be better understood, so that disaster management decisions do not exacerbate the already compromised poor mental health of many in the sector (Vroegindewey and Kertis Citation2021).

This study had a range of strengths, not least methodologically, with the establishment of a stakeholder panel with broad representation of all the various sectors involved in or impacted by the incursion, including MPI. This group was regularly consulted and had active input into various aspects of the study (see Acknowledgements for further details), while also acting as a sounding board for the researchers on several occasions. This panel also allowed the research team to remain removed from participants until data collection commenced, as participants were identified by the representative of their sector on the stakeholder panel. Moreover, the forming of a governance group provided the research team with a source of sagacious advice when needed. The transdisciplinary nature of the research team also proved to be a key strength, allowing a multiplicity of lenses to be applied to the study design and the process of data analysis, thereby coming to a comprehensive understanding of the experiences of these veterinarians. Finally, having an experienced animal health care professional and veterinary epidemiologist (MB) embedded within the Southland rural farming sector as part of the research team was a significant asset. Ultimately, this study meets Stenfors and colleagues’ (Citation2020) markers of trustworthy qualitative research as presented in the Supplementary Material.

Nonetheless, this research focused on the regions of Otago and Southland in the lower South Island of New Zealand; consequently, findings may not be consistently applicable to the experience of veterinarians in other regions of the country. Southland, however, was considered “ground zero” for this incursion and hence the decision was made to focus the study on this region and its neighbour, Otago.

Focus groups are not without their challenges. It cannot be presumed that individuals in a focus group are expressing their own definitive individual point of view. They are talking about their experiences within a specific context and within a specific culture; therefore, they may be reticent to discuss views which challenge the dominant narrative (Gibbs Citation1997). The focus group schedule largely focused on asking participants about the impacts of their involvement in the incursion. The dominant narrative was embedded within a trauma lens, so as a consequence, positive experiences may have been less commented upon. Within focus groups, conversations can be dominated by one or two participants or, conversely, a reticent speaker may not feel able to express their views, and these challenges cannot be underestimated (Bryman Citation2012). However, these challenges can be managed by the use of experienced moderators (Gibbs Citation1997), as was the case in this study. While participant numbers were small, the decision not to interview any additional veterinarians or invite others to participate in a focus group was the result of the narratives providing the researchers with a conceptual depth of understanding of the experiences of the participants. It is recognised that studies using empirical data can provide this conceptual understanding with small numbers of participants, especially when the study population is homogeneous (Hennink et al. Citation2019). While the narratives from these study participants are clearly supported by other contemporary independent research referred to in this article, it also needs to be acknowledged that further data collection may have added different insights (Low Citation2019).

Conclusion

This study identified that the lifeworld (lived experience in a particular place) of the study participants who were rural clinical veterinarians during the M. bovis incursion eradication programme had been negatively impacted. The pervasive nature of the epistemic injustice that participants suffered, and the frequency with which they had to bear witness to the suffering of their clients and their clients’ animals resulted in significant moral distress, as evidenced by the emotional content of their narratives at a time distant from their experiences. In the future it is hoped that the situated knowledge and skills of veterinarians will be better used to the benefit of all.

As New Zealand prepares for the next exotic incursion, it is incumbent upon decision-making stakeholders that they understand the significant impact the M. bovis incursion had on some rural veterinarians. Recognising this will facilitate more meaningful engagement with this key stakeholder group, who are vital to disease recognition, control and eradication, and will provide an improved and less challenging response.

Further research is needed to understand the factors that drive moral distress in veterinarians, who is most at risk, and how best to support veterinarians in rural practices involved in management of exotic disease incursions. Finally, there is a need to develop specific tools to understand the severity of moral distress that veterinarians (and their associated allied veterinary workforce) are experiencing, in order to develop interventions to help them understand their experiences and develop useful coping strategies.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (152.7 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors wish to sincerely acknowledge the participants for the time taken to share their experiences, which for some brought to mind traumatic events that remained deeply impactful. Without their commitment this research would never have happened. We also acknowledge the Stakeholder Panel for their knowledge and expertise of all matters farming and rural, that contributed to the development of the project’s methodology, as well as their networking and linkages into the southern rural community and incursion response networks. Additionally, we wish to acknowledge the wisdom and guidance of the Governance Group, who facilitated our navigation through at times delicate discussions with the wider community connected with the research project. The funder was Lottery Health Research LHR-2019-102211. In acknowledging the Stakeholder Panel we note that while the project was not a co-design study, stakeholder panelists contributed to the study design, data collection methods, the questionnaire manual and the recruitment of participants from the sector they represented. This does not imply responsibility of stakeholders for data interpretation and the write-up. The agency for the study resided with the researchers. Sectors represented on the stakeholder panel and the associated representatives are named below or the organisation represented is stated. Farmers –Southland Lloyd and Kathy MacCallum, Broadlands and Green Meadows farms; Small businesses – Sheree Cary, CEO, Southland Chamber of Commerce; Southland and Otago Agribusinesses – Luke MacPherson, Area Manager, Agribusiness, Southland Rabobank; Southland and Otago Rural Organisations – Katrina Thomas, Dairy Women’s Network, Southland and Otago Veterinarians – Rebecca Morley, Veterinarian; two representatives from Ministry for Primary Industries. Members of the Governance Group: Professor Peter Crampton (Centre for Hauora Māori), Ian Handcock (Farmstrong/Founder Fit4farming; retired farmer), Dr Mike King (Bioethics, Otago University), Lisa Te Raki (Ngai Tahu; Kaiwhakaako – Hauora Māori/Teaching Fellow – Māori Health), John Maclachlan (Veterinarian advisor).

References

- *Anderson I. Foot and Mouth Disease 2001: Lessons to be Learned Inquiry Report. The Stationery Office, London, UK, 2001

- Arbe Montoya A, Hazel S, Matthew S, McArthur M. Moral distress in veterinarians. Veterinary Record 185, 631, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.105289

- Bartram DJ, Baldwin DS. Veterinary surgeons and suicide: a structured review of possible influences on increased risk. Veterinary Record 166, 388–97, 2010. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.b4794

- Bartram DJ, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DS. A cross-sectional study of mental health and well-being and their associations in the UK veterinary profession. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44, 1075–85, 2009a. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-009-0030-8

- Bartram DJ, Yadegarfar G, Baldwin DS. Psychosocial working conditions and work-related stressors among UK veterinary surgeons. Occupational Medicine 59, 334–41, 2009b. https://doi.org/10.1093/occmed/kqp072

- Batchelor C, McKeegan D. Survey of the frequency and perceived stressfulness of ethical dilemmas encountered in UK veterinary practice. Veterinary Record 170, 19, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.100262

- Batchelor C, Creed A, McKeegan D. A preliminary investigation into the moral reasoning abilities of UK veterinarians. Veterinary Record 177, 124, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.102775

- Bennett A, Chamberlin S. Resisting moral residue. Pastoral Psychology 62, 151–62, 2013. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11089-012-0458-8

- *Biesta G. Pragmatism and the philosophical foundations of mixed methods research. In: Tashakkori A, Teddlie C (eds). Handbook of Mixed Methods in Social and Behavioural Research. 2nd Edtn. Pp 95–117. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2010. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335193.n4

- *Biosecurity New Zealand. Rapid Risk Assessment: Mycoplasma bovis in Bovine Semen. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/34179-mycoplasma-bovis-in-bovine-semen-rapid-risk-assessment (accessed 12 December 2022). Ministry for Primary Industries, Wellington, NZ, 2019

- *Biosecurity New Zealand. Timeline: Mycoplasma bovis in New Zealand. https://www.mbovis.govt.nz/assets/Uploads/RESOURCES-M-bovis-timeline-web.pdf (accessed 30 July 2022). Ministry for Primary Industries, Wellington, NZ, 2020

- Boyce C, Jaye C, Noller G, Bryan M, Doolan-Noble F. Mycoplasma bovis in New Zealand: a content analysis of media reporting. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online 16, 335–55, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/1177083X.2021.1879180

- Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology 18, 328–52, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 13, 201–16, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1704846

- Braun V, Clarke V. Toward good practice in thematic analysis: avoiding common problems and be(com)ing a knowing researcher. International Journal of Transgender Health, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/26895269.2022.2129597

- *Bryman A. Sampling in qualitative research. In: Bryman A (eds). Social Research Methods. 4th Edtn. Pp 415–29. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2012

- Byskov M. What makes epistemic injustice an “injustice”? Journal of Social Philosophy 52, 116–33, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/josp.12348

- Caceres S. The roles of veterinarians in meeting the challenges of health and welfare of livestock and global food security. Veterinary Research Forum 3, 155–7, 2012

- Calcutt M, Lysnyansky I, Sachse K, Fox L, Nicholas A, Ayling R. Gap analysis of Mycoplasma bovis disease, diagnosis and control: an aid to identify future development requirements. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 65, 91–109, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12860

- Cardwell J, Lewis E. Stigma: coping, stress and distress in the veterinary profession – the importance of evidence-based discourse. Veterinary Record 184, 706–8, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.l3139

- Čartolovni A, Stolt M, Scott PA, Suhonen R. Moral injury in healthcare professionals: a scoping review and discussion. Nursing Ethics 28, 590–602, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733020966776

- *Convery I, Mort M, Baxter J, Bailey C. Animal Disease and Human Trauma: Emotional Geographies of Disease. Palgrave MacMillan, London, UK, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230227613

- Crane MF, Phillips JK, Karin E. Trait perfectionism strengthens the negative effects of moral stressors occurring in veterinary practice. Australian Veterinary Journal 93, 354–60, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12366

- Dean W, Talbot S, Dean A. Reframing clinician distress: moral injury not burnout. Federal Practitioner 36, 400–2, 2019

- *Doolan-Noble F, Bryan M, Noller G, Jaye C. A Summary of the Preliminary Findings of the Two Year Project: The Psychosocial Impact of Mycoplasma bovis on Rural Communities in Southern New Zealand. Ministerial Briefing: The Hon. Damien O’Connor, Minister of Agriculture. University of Otago, Dunedin, NZ, 2021

- Dow M, Chur-Hansen A, Hamood W, Edwards S. Impact of dealing with bereaved clients on the psychological wellbeing of veterinarians. Australian Veterinary Journal 97, 382–9, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/avj.12842

- Dudek K, Nicholas RAJ, Szacawa E, Bednarek D. Mycoplasma bovis infections – occurrence, diagnosis and control. Pathogens 9, 640, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3390/pathogens9080640

- Durnberger C. Am I actually a veterinarian or an economist? Understanding the moral challenges for farm veterinarians in Germany on the basis of a qualitative online survey. Research in Veterinary Science 133, 246–50, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rvsc.2020.09.029

- Enticott G. Navigating the veterinary borderlands: ‘heiferlumps’, epidemiological boundaries and the control of animal disease in New Zealand. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 42, 153–65, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12155

- Enticott G, Donaldson A, Lowe P, Power M, Proctor A, Wilkinson K. The changing role of veterinary expertise in the food chain. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 366, 1955–65, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2010.0408

- *Environment and Natural Resources Committee. Enviroment and Natural Resources Committee Inquiry Into the Control of Ovine Johne’s Disease in Victoria. Parliament of Victoria, Melbourne, Australia, 2000

- Epstein E, Delgado S. Understanding and addressing moral distress. The Online Journal of Issues in Nursing 15, 1, 2010. https://doi.org/10.3912/OJIN.Vol15No03Man01

- Fawcett A, Mullan S. Managing moral distress in practice. In Practice 40, 34–6, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1136/inp.j5124

- *Fricker M. Epistemic Injustice: Power and the Ethics of Knowing. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK, 2007. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198237907.001.0001

- *Gibbs A. Focus groups. Social Research Update 19, University of Surrey, Guildford, UK, 1997

- Goldkuhl G. Pragmatism v interpretivism in qualitative information systems research. European Journal of Information Systems 21, 135–46, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/ejis.2011.54

- *Green J, Thorogood N. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. 3rd Edtn. Pp 95–150. Sage, London, UK, 2014.

- *Guba EG, Lincoln YS. Competing paradigms in qualitative research. In: Denzin NK, Lincoln YS (eds). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Pp 105–17. Sage, Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 1994

- Hansen B, Østerås O. Farmer welfare and animal welfare – exploring the relationship between farmer’s occupational well-being and stress: farm expansion and animal welfare. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 170, 9, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2019.104741

- Hennink M, Kaiser B, Weber M. What influences saturation? Estimating sample sizes in focus group research. Quality Health Research 29, 1483–96, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318821692

- *Jameton A. Nursing Practice: The Ethical Issues. Prentice-Hall, Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984

- Jaye C, Noller G, Bryan M, Doolan-Noble F. “No better or worse off”: Mycoplasma bovis, farmers and bureaucracy. The Journal of Rural Studies 88, 40–9, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2021.10.007

- Jaye C, McHugh J, Doolan-Noble F, Wood L. Wellbeing and health in a small New Zealand rural community: assets, capabilities and being rural-fit. Journal of Rural Studies 92, 284–93, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.04.005

- Jinkerson J. Defining and assessing moral injury: a syndrome perspective. Traumatology 22, 122–30, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1037/trm0000069

- Kwok C. Epistemic injustice in workplace hierarchies: power, knowledge and status. Philosopy and Social Criticism 47, 1104–31, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1177/0191453720961523

- *Long M, Springer S, Burgener I, Grimm H. Small animals, big decisions: potential of moral case deliberation for a small animal hospital on the basis of an observational study. In: Schübel H, Wallimann-Helmer I (eds). Justice and Food Security in a Changing Climate. Pp 261–6. Wageningen Academic Publishers, Wageningen, Netherlands, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3920/978-90-8686-915-2_39

- Low J. A pragmatic definition of the concept of theoretical saturation. Sociological Focus 52, 131–9, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/00380237.2018.1544514

- Moir F, Van den Brink A. Current insights in veterinarians’ psychological wellbeing. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 68, 3–12, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2019.1669504

- Morley G, Bradbury-Jones C, Ives J. The moral distress model: an empirically informed guide for moral distress interventions. Journal of Clinical Nursing 31, 1309–26, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15988

- Morley G, Ives J, Bradbury-Jones C, Irvine F. What is ‘moral distress’? A narrative synthesis of the literature. Nursing Ethics 26, 646–62, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017724354

- Moses L, Malowney M, Boyd J. Ethical conflict and moral distress in veterinary practice: a survey of North American veterinarians. Journal of Veterinary Internal Medicine 32, 2115–22, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/jvim.15315

- Nicholas R, Fox L, Lysnyansky I. Mycoplasma mastitis in cattle: to cull or not to cull. Veterinary Journal 216, 142–7, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tvjl.2016.08.001

- Noller G, Doolan-Noble F, Jaye C, Bryan M. The psychosocial impact of Mycoplasma bovis on southern New Zealand farmers: the human cost of managing an exotic animal disease incursion. Journal of Rural Studies 95, 458–66, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrurstud.2022.09.037

- O’Connor E. Sources of work stress in veterinary practice in the UK. Veterinary Record 184, 588, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.104662

- *Office of the Chief Science Adviser. Report on Mycoplasma bovis Casing and Liaison Backlog. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/35538/direct (accessed 12 December 2022). Ministry of Primary Industries, Wellington, NZ, 2019

- Palinkas LA, Horwitz SM, Green CA, Wisdom JP, Duan N, Hoagwood K. Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health 42, 533–44, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

- *Paskin R. Mycoplasma bovis in New Zealand: A Review of Case and Data Management. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/35541/direct (accessed 12 December 2022). Dairy NZ, Wellington, NZ, 2019

- Pauly B, Varcoe C, Storch J. Framing the issues: moral distress in health care. HEC Forum 24, 1–11, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10730-012-9176-y

- *Remnant J. Ensuring the Veterinary Profession Meets the Needs of Livestock Agriculture Now and in the Future. Nuffield Farming Scholarships Trust, Taunton, UK, 2020

- Riedel PL, Kreh A, Kulcar V, Lieber A, Juen B. A scoping review of moral stressors, moral distress and moral injury in healthcare workers during COVID-19. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 19, 1666, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19031666

- Robinson WD, Springer PR, Bischoff R, Geske J, Backer E, Olson M, Jarzynka K, Swinton J. Rural experiences with mental illness: through the eyes of patients and their families. Families, Systems, & Health 30, 308–21, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030171

- *Shadbolt N, Saunders C, Paskin R, Cleland T. The Mycoplasma bovis Programme: An Independent Review 2021. Ministry for Primary Industries, Wellington, NZ, 2021

- Sim J, Saunders B, Waterfield J, Kingstone T. Can sample size in qualitative research be determined a priori? International Journal of Social Research Methodology 21, 619–34, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1080/13645579.2018.1454643

- Simonovich S, Webber-Ritchey K, Spurlark R, Florczak K, Mueller Wiesemann L, Ponder T, Reid M, Shino D, Stevens B, Aquino E. Moral distress experienced by US nurses on the frontlines during the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for nursing policy and practice. Sage Open Nursing 8, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1177/23779608221091059

- *Statistics New Zealand. Which Industries Contributed to New Zealand’s GDP? https://www.stats.govt.nz/tools/which-industries-contributed-to-new-zealands-gdp/ (accessed 27th July 2022). Statistics New Zealand, Wellington, NZ, 2019

- Stenfors T, Kajamaa A, Bennett D. How to assess the quality of qualitative research. The Clinical Teacher 17, 596–9, 2020. https://doi.org/10.1111/tct.13242

- Vroegindewey GV, Kertis K. Veterinary behavioural health issues associated with disaster response. Australian Journal of Emergency Management 36, 78–84, 2021

- Whiting TL, Marion CR. Perpetration-induced traumatic stress – a risk for veterinarians involved in the destruction of healthy animals. Canadian Veterinary Journal 52, 794–6, 2011

- Williamson V, Stevelink SAM, Greenberg N. Occupational moral injury and mental health: systematic review and meta-analysis. British Journal of Psychiatry 212, 339–46, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.55

- *Non-peer-reviewed