ABSTRACT

Aims

To compare the retention by New Zealand dairy cows kept at pasture in a lame cow group, of three hoof block products commonly used in the remediation of lameness.

Methods

Sixty-seven farmer-presented Friesian and Friesian x Jersey dairy cows from a single herd in the Manawatū region (New Zealand) suffering from unilateral hind limb lameness attributable to a claw horn lesion (CHL) were randomly allocated to one of three treatments: foam block (FB), plastic shoe (PS) and a standard wooden block (WB). Blocks were applied to the contralateral healthy claw and checked daily by the farm staff (present/not present) and date of loss was recorded. Blocks were reassessed on Day 14 and Day 28 and then removed unless further elevation was indicated. Daily walking distances were calculated using a farm map and measurement software. Statistical analyses included a linear marginal model for distance walked until block loss and a Cox regression model for the relative hazard of a block being lost.

Results

Random allocation meant that differences between products in proportion used on left or right hind foot or lateral or medial claw were small. Mean distance walked/cow/day on farm tracks whilst the block was present was 0.32 (min 0.12, max 0.45) km/day; no biologically important difference between products in the mean distance walked was identified. Compared to PS, cows in the WB group were five times more likely to lose the block (HR = 4.8 (95% CI = 1.8–12.4)), while cows in the FB group were 9.5 times more likely to lose the block (HR = 9.5 (95% CI = 3.6–24.4)).

Conclusions

In this study, PS were retained for much longer than either FB or WB. As cows were managed in a lame cow group for the study duration, walking distances were low and did not impact on the risk of block loss. More data are needed to define ideal block retention time.

Clinical relevance

In cows with CHL the choice of block could be based on the type of lesion present and the expected re-epithelisation times.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

Claw horn lesions (CHL) are an important cause of lameness in dairy cattle (Chesterton et al. Citation2008). They produce an alteration in gait by causing pain, especially when the affected claw is bearing weight while the cow is walking. Relieving pressure on the affected claw has thus long been a key focus of treatment of cows with CHL, and this is achieved by a combination of corrective trimming and elevation of the affected claw with a block placed on the contralateral claw (Toussaint-Raven Citation2003; Shearer et al. Citation2015).

Claw horn lesions heal through re-epithelialisation of the damaged horn or, if the basement membrane of the hoof epithelium has been damaged, through a combination of granulation and re-epithelialisation (Shearer et al. Citation2015). Elevation of the claw through the use of hoof blocks, alongside corrective trimming, assists this process by reducing the risk of further damage to the affected claw, and by limiting contact with contaminated surfaces, especially surfaces contaminated with slurry. In order to achieve these effects, once attached, blocks need to persist for long enough for re-epithelisation to become established and not be compromised by the affected claw bearing weight.

The time taken for re-epithelialisation is dependent on lesion severity, with Lischer et al. (Citation2001) reporting that in uncomplicated sole ulcers healing time depended on the degree of corium damage. Lesions with only minimal corium damage took 25 days to re-epithelialise, while lesions with moderate corium damage took 33 days and those with severe damage, 42 days. Van Amstel et al. (Citation2003) reported that severe damage to the corium that led to the production of excessive granulation tissue could significantly delay re-epithelialisation, so that it took up to 60 days after treatment. These and other similar studies (Shearer et al. Citation2015; Klawitter et al. Citation2019) reported healing times in cows with sole ulcer, rather than white line disease which is the most common form of lameness in NZ dairy cows (Chesterton et al. Citation2008). Data on healing times for white line disease are not available, but the consensus seems to be that they are likely to be similar (Shearer and van Amstel Citation2017).

There is also limited information on how the environment of the lame cow at pasture influences the re-epithelialisation process as most papers report studies of healing in housed cows. Only one paper by Lischer et al. (Citation2000) reported that for cows on alpine pasture the average time for formation of a closed layer of horn was 14 days, shorter than the time Lischer et al. (Citation2001) reported in housed cattle. Similar data from permanently pasture-based cattle such as those that predominate in New Zealand and most dairying areas in Australia are not available. Nevertheless, based on the published data, it seems likely that even for mild lesions we may need blocks to provide elevation for at least 14 days to optimise re-epithelialisation in the majority of cows.

Blocks to elevate the non-lame claw have been recommended as treatments for cattle with claw horn lesions since at least the early 1950s (Wiessner and Wiessner Citation1951). However, despite the length of time and the large number of products that have been used (Nuss and Tiefenthaler Citation2000), there have been only a small number of studies that have investigated how long blocks are retained after application in dairy cows, with both study design, blocks tested and results varying markedly across studies (see ).

Table 1. Summary of results from published studies evaluating the retention of orthopaedic hoof blocks (shoes) for treatment of lameness in dairy cows.

Although several of the studies reported in were undertaken in cattle at pasture (Pyman Citation1997; Wehrle et al. Citation2000; Perusia Citation2006; Ranjbar et al. Citation2021), none of these were undertaken in New Zealand. However, underfoot conditions in New Zealand are significantly different from Australia, Argentina, and alpine Switzerland, with differences such as pasture moisture, and track constituents, quality, and length all likely being important. Furthermore, no studies were undertaken in cattle kept in a “lame cow group” where cattle are kept close to the parlour and only milked once per day (which is standard practice on many dairy farms in New Zealand); indeed, Pyman (Citation1997) explicitly suggested that blocks could be an alternative to that approach in the management of lame cows. In addition, in 2013, Shoof International launched, in New Zealand, a foam block designed to be a cheaper alternative to wooden and plastic blocks/shoes (especially in early/mild lameness cases). There are very limited published data on the retention of this block (Stroe et al. Citation2015). There are several different blocks available in New Zealand differing in material, elevation height, and ease, method, and speed of block application. Hoof blocks may be used by a range of operators (farms staff, foot trimmers, veterinarians, and veterinary technicians) using differing rationale for block use and individual differences in methods of application. Under these conditions there is an absence of information on the performance of different blocks with regards to block retention and suitability for pasture-based systems in New Zealand. The aim of this study was to investigate differences in block retention between three commonly used blocks available within New Zealand under standardised conditions typical for the management of New Zealand lame dairy cows.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the Massey Animal Ethics Committee (Protocol number: MUAEC 16/66).

Animals

The study was conducted on a 600-cow, seasonal, spring-calving dairy farm in the Manawatū region of New Zealand. Sixty-seven Friesian and Friesian x Jersey dairy cows with unilateral hind limb lameness were recruited for this study during regular fortnightly lameness visits between October 2016 and March 2017, covering the New Zealand summer and early autumn period.

Study overview

Cows identified as lame by the farmer were restrained using a mobile lameness crush or tilt table (hydraulic WOPA Pro + crush; Veehof, Ashburton, NZ; hydraulic tilt table VET PRO; Rosensteiner, Waldneukirchen, Austria) for examination, diagnosis, and treatment by a veterinarian. Both restraint methods provided equivalent and effective access for block placement.

All cows meeting the study criteria for unilateral hind limb lameness with hoof block placement indicated as part of the treatment were recruited into the study (Day 0). Animals were excluded if, based on the clinical judgement of the first author (KM), a veterinarian with 11 years’ experience treating lame cows in Europe and New Zealand, both claws of the presenting limb were diseased to an extent that precluded block application to the less severely affected claw, or if they had bilateral hind limb disease that required multiple block application.

Initial visit

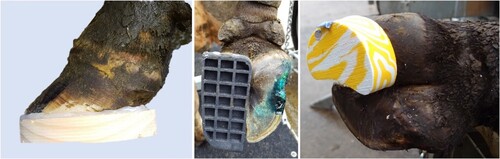

Recruited cows were evaluated and treated on an individual basis. Lesion type, procedure(s) performed, and any treatments given (non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or antibiotics) were recorded as well as body condition score (BCS). At the end of the therapeutic trimming process, enrolled cows were randomly allocated to one of three block treatments using a random allocation table created using Microsoft Excel (Redmond, WA, USA). Three hoof block products, all of which are commonly used in New Zealand, were selected for this study (): (1) wooden block (WB) in one size and made from New Zealand plantation pine (Pinus radiata) with Bovi-Bond urethane adhesive (Shoof International, Cambridge, NZ); (2) plastic shoe (PS) with methyl methacrylate glue (CowSlip, regular and plus size; Giltspur Scientific Ltd, Ballyclare, Ireland); and (3) foam block (FB) with cyanoacrylate glue (Walkease (three sizes); Shoof International).

Figure 1. Hoof blocks used in a study of the retention of hoof blocks used for the treatment of lame dairy cows at pasture, from left to right: wooden block with Bovi-Bond adhesive (Shoof International, Cambridge, NZ), CowSlip (Giltspur Scientific Ltd, Ballyclare, Ireland), Walkease, medium size (Shoof International).

The allocated product was fitted by KM with attention to optimal claw preparation, sizing, and placement in line with the manufacturer’s instructions for each product (see Supplementary Material). If different sizes were available for an allocated product, size was selected according to the size of the claw following the rule that blocks should be long enough to extend to at least half of the heel length (“half-heel rule”; Nuss et al. Citation1998, Citation2000) to ensure optimal fit. Cows were enrolled for the study until at least 20 cows had received each product and presented for a follow-up visit 14 days later.

Cow management

Following placement, a brightly coloured leg band was fitted to help the farmer to identify and observe cows with orthopaedic blocks between visits. Recruited cows were kept together with all other lame cows in a single group (lame group), grazed on paddocks close to the milking parlour and milked once a day in the morning. Farm staff observed the treated animals daily at milking and recorded the date of loss if a block was absent. Cows were kept in the lame group and were followed through until they were determined as no longer lame by the attending veterinarian and had either lost their block or had it removed on Day 28.

Follow-up visits

Cows were re-examined on Day 14. The lame foot was lifted, clinical progress of the claw horn lesion noted and further paring of the horn performed if required. If the block had been lost, it was replaced by KM if continued elevation was likely to be beneficial. No further data were collected for those cows that received a second block on re-examination. Cows that had lost blocks before Day 14 but were thought to be unsound by farm staff could be re-examined earlier, and a block re-applied, but again no further data were collected for these cows. No blocks were actively removed on Day 14 if they still fitted well, regardless of the healing stage of the CHL.

Cows received a second re-examination on Day 28. If the hoof block was still in place on Day 28, it was removed using a pair of pliers unless, in the opinion of KM, the cow would benefit from the continued use of a block and there was no evidence of pain on testing the blocked claw with hoof testers. The ease of block removal was recorded by KM using a subjective score of easy, normal, or hard.

For all cows, the interval between application and loss of the block was recorded. In most cases this was the date recorded by the farm staff; however, if the block was observed to be lost on the examination on Day 14 or Day 28 and had not been recorded as lost by farm staff, it was recorded as being lost on the day of examination. For cases where the date of block loss was unknown, interviews with farm staff were able to identify on which day the blocks were lost. The data from all cows were censored at Day 28 if the block was still present at that examination, even if the block was kept in place.

Walking distances

A farm map and measurement software (https://nz.mapometer.com; accessed 10 April 2017) were used to estimate the daily distance travelled by the lame cow group from the paddock they were in prior to milking to the milking parlour and from the parlour to the paddock they were allocated to after milking. For each cow, the estimated mean distance walked per day on the farm tracks whilst the block was present (or Day 28, whichever was shorter) was calculated.

Statistics

All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 25 (IBM; Seattle, WA, USA). Descriptive statistics for foot and claw for each of the products were visually compared to assess whether randomisation had produced equivalent distributions. Average daily distances walked until block loss or Day 28 for each of the three treatment groups were compared using a linear marginal model with distance walked as the output and product as the predictor variable. A Cox regression model was then used to estimate the effect of product applied on the relative hazard of a block being lost. This model included product, foot, and claw as the predictor variables. Kaplan–Meier and log–log plots were used to assess whether the proportional hazards requirement was met.

Results

Overall, 27 blocks were applied to lateral claws and 40 blocks to medial claws. Random allocation meant that the differences between products in proportion used on left or right hind foot or lateral or medial claw were small. The distribution of the three different products over the claws in the hind limbs is summarised in .

Table 2. Distribution of three hoof block products applied to hind feet of cows (n = 67) enrolled in a study of retention of hoof blocks used to treat lame dairy cows at pasture.

Distance walked

The mean estimated distance walked on farm tracks per cow per day whilst the block was present (up to Day 28) was 0.32 (min 0.12, max 0.45) km/day. There was no biologically important difference between products in the mean distance walked (largest mean difference between product groups 0.025 (95% CI = −0.015–0.065) km/day; p = 0.35) (see ). The data for mean distance walked up to block loss for Day 0 to Day 14 and between Day 14 and Day 28 are also shown in (the former figure includes all cows, whereas the latter only includes cows that retained their blocks for >14 days).

Table 3. Mean (95% CI) track distances walked (km/day) up to block loss (or Day 28, whichever was later) by cows (n = 67) enrolled in a study of retention of three different hoof blocks for the treatment of lame cows at pasture.

Block survival

In 11 cows, farm staff had not reported block loss prior to veterinary examination on Day 14/28. In three cases (all on Day 14), the cows had just lost their blocks, in all the other eight cases (two PS and six FB) discussions with farm staff were able to identify on which day the blocks had been first observed as lost (using morning milking as the reference point). Overall, 25 blocks were still in place at Day 28 (six WB, two FB and 17 PS); 7 of these blocks (28%) were left on for an extra 1–2 weeks for medical reasons as the lesion on the contralateral claw was not fully healed. Block removal at 28 days was scored as “easy” for 100% of the remaining FB, 80% of WB and 64% of PS. The removal of those FB and PS not scored as easy was scored as “normal” with no blocks being considered “hard” to remove.

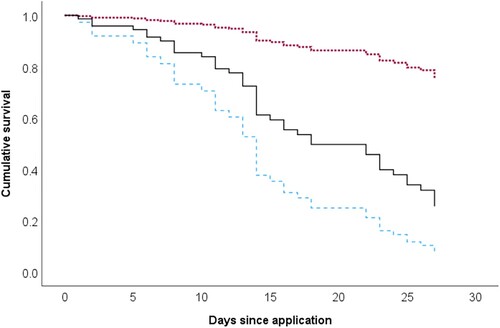

The HR of losing a block on the right hind foot was 1.69 (95% CI = 0.88–2.99) times that of the left hind foot, while for a cow lame on the medial claw the HR of losing a block was 1.42 (95% CI = 0.7–2.67) times that of a cow that was lame on the lateral claw. Thus, although we identified no clear effect of either foot or claw on the hazard of losing a block, our data do not exclude a biologically important effect of either foot or claw, i.e. although the CI of our calculated HR included one (indicating that our data were compatible with no effect) they also included much higher HR consistent with a biologically important difference between claws/feet. However, there was a clear difference between products in the hazard of losing a block. Compared to PS the HR for WB was 4.8 (95% CI = 1.8–12.4) while that for FB was 9.5 (95% CI = 3.6–24.4). This means that at any time point during the study, cows in the WB group were about five times more likely to lose them than PS cows, while for FB the equivalent figure was about 9.5 times.

The median survival times for WB and FB were 22 and 14 days, respectively. No median figure could be calculated for PS as 18/23 were still present > 25 days after application. The effect of product on survival time as estimated by the Cox model is illustrated in . Calculation of 95% confidence bands that adequately take into account the correlation between serial time points is a non-trivial exercise for the predictions from a Cox model (Sachs et al. Citation2022). The HR clearly indicates overall there is a greater hazard of block loss for FB and WB compared to PS. In this study, we are more interested in an overall summary of the difference in the hazard of block loss, rather than a time-point by time-point comparison, and we do not believe that presentation of confidence bands will add to this interpretation.

Figure 2. Survival curve from Cox regression model showing comparison between three hoof block products in time between application and loss (accounting for limb and claw to which block was applied, i.e. right vs. left hind limb and medial vs. lateral claw). Data are right censored at 28 days. The HR showed a clear difference between products in the hazard of losing a block. Compared to the plastic shoe (PS; - - -) the HR for the wooden block (WB; ———) was 4.8 (95% CI = 1.8–12.4) while the HR for the foam block (FB; – – – –) was 9.5 (95% CI = 3.6–24.4).

Discussion

Although block use is strongly recommended in lame cows in New Zealand (Laven et al. Citation2008; Mason et al. Citation2023), this is the first study under New Zealand conditions to examine block retention in lame cows. There were significant differences between blocks in retention with PS being retained for much longer than either of the other two blocks, with, on any given day, the hazard of loss being 5 and 9.5 times higher for the wooden and foam blocks, respectively.

This was a small-scale study on a single farm over one spring to autumn period, and blocks were applied by a single operator. Therefore, care is needed before generalising the results of this study to farms across New Zealand. Management of these cows matched standard practice in New Zealand, with cows being managed in a lame cow group within 200 m of the parlour and milked once-a-day (Mason et al. Citation2023). However, it is likely that cows were kept longer in the lame cow group than is normal (especially those in the PS group) as on most farms cows are returned to the main milking herd once they are no longer observably lame (with recent estimates suggesting that the median time from lameness treatment to normal gait on New Zealand farms is 18 days; Mason et al. Citation2023). Thus, cows which retained their blocks for more than 17 days (20/23 cows in the PS group, 13/21 in the WB group and 6/23 in the FB group) are likely to have walked significantly less per day in the present study than they would have done if they had been returned to the main herd once they were not observably lame. However, it is unclear whether walking distance does have a major impact on the risk of losing a block. If we compare our results to the two Australian studies that allowed cattle with blocks on, to walk as far as their normal, non-blocked herd mates (i.e. Pyman Citation1997; Ranjbar et al. Citation2021), we can estimate the potential effect of walking restriction on the relative risk of a WB being lost in the first 14 days after application. Compared to Pyman (Citation1997), the relative risk of a WB being lost in the first 14 days in the current study was 0.78 (95% CI = 0.41–1.47), while compared to the low-density wooden blocksFootnote1 used by Ranjbar et al. (Citation2021), the equivalent relative risk was 0.57 (95% CI = 0.29–1.12). Clearly, distance walked was not the only difference between the studies, but the CI of these relative risk estimates show that although our data are consistent with reduced walking distance increasing block retention, they are also consistent with cows being able to walk longer distances without increasing the risk of loss. More research on the impact of walking distance on block retention is required, with a particular need for direct comparison studies.

This finding highlights our lack of understanding of the factors that affect block retention. Most studies that have included comparative data have, like this study, looked solely at the effect of block type. Our data are consistent with the widely held opinion (e.g. Shearer and van Amstel Citation2017) that wooden blocks (of which our WB are one variant) are retained for shorter periods of time than plastic shoes (of which the PS (CowSlips) we used are one variant), perhaps because of the shape of the shoe, which means that both the claw sole and claw wall are attached to the shoe whereas only the sole is attached to the wooden block. However, comparative studies have not consistently shown better retention of PS, such as CowSlips, than wooden blocks (see ) and it is not clear why this is the case.

Another important variable is the glue that was used. Multiple different glues, with varying properties, have been used to attach blocks to soles (Mohamaddoust et al. Citation2021). However, despite the claims of efficacy from manufacturers (e.g. Anonymous Citation2022), as far as the authors are aware, there are no peer-reviewed published studies of the effect of different glues on block retention. In a study using PS (CowSlips) as the block, Wehrle et al. (Citation2000) reported that changing the glue from the standard CowSlip glue (based on polymethyl methacrylate and benzoyl peroxide) to the glue supplied for wooden blocks (based on 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate and methacrylic acid amide) improved retention. However, the comparison was not contemporaneous, and the authors further modified the CowSlips to improve durability in the alpine environment of that study. Their results are in complete contrast to the findings of our study and that of Blowey et al. (Citation1999), with both those studies using the standard PS (CowSlip) glue. More research is needed in this area as, despite the plethora of different glues available on the market (many of which are simply variants of epoxy, urethane, or methacrylate glues; Mohamaddoust et al. Citation2021), the best published peer-reviewed “comparative” study is that by Wehrle et al. (Citation2000).

Other factors not tested in the studies reported in that could potentially affect block retention include environmental humidity and temperature (especially at the time of block application), floor surfaces (especially in housed cows), applicator experience with particular blocks, method of hoof preparation (e.g. methylated spirits vs. towel drying vs. hot air gun), cow breed/weight and hoof size, affected limb (front vs. hind) and standing time (especially on hard surfaces). All of these factors (and others) need further research so we can optimise retention of blocks.

The other area where we lack information is how to define optimal retention time and how time to recovery from a CHL should be defined. Is it time to re-epithelialisation of the lesion, time to non-response of hoof testers, time to normal gait or time to non-lame status (locomotion score < 2, in a 0–3 scoring system)? As discussed earlier, even for mild lesions, if we want the block to provide elevation until the re-epithelialisation of the damaged horn is complete, we may need blocks to persist for at least 14 days. For all three block types tested in this study, this target was achieved by 50% or more blocks. Thus, irrespective of the block used, most cattle treated using a block will have elevation of the affected claw for at least 14 days. In cows with CHL, the choice of block could be based on the expected time to recovery of that lesion.

Optimum time for block persistence probably varies between cows, farms, seasons, and lesions. Mason et al. (Citation2023) found that 50% of treated lame cows (85% of which had a wooden block applied) were sound (lameness score = 0 or 1, based on current 4-point (0–3) DairyNZ industry standard locomotion scoring system) 7 days after treatment. We thus need more data on how block retention affects healing of claw horn lesions and how often blocks will need replacing if they are lost.

Increased block retention may not be solely a beneficial effect. Although Blowey et al. (Citation1999) reported that PS (CowSlips) could be retained for up to 224 days without detected problems, Fiedler (Citation2011) reported that after 35 days, retention of wooden blocks was associated with poor quality horn, sole haemorrhages and, in some cases, solar ulceration on the previously healthy blocked claw. The consensus view appears to be to assess blocks for removal after 28 days. Further research on the need to remove blocks if they persist for 28 days is needed, especially under New Zealand conditions.

We did not measure the response in terms of lameness score in this study. This was a deliberate decision, as to get accurate times to lameness scores of 0 or 1 would have required frequent lameness scoring (e.g. twice a week; Mason et al. Citation2023). Although blocks have been shown to reduce lameness score immediately after application (Plüss et al. Citation2021), the current study enrolled a low number of cows and, like other studies of a similar size (Laven et al. Citation2008; Thomas et al. Citation2015; Mason et al. Citation2022), lacked the power to detect a difference in lameness score between treatment groups.

Conclusions

This study has shown that under New Zealand conditions, with cows milked once a day and kept within approximately 200 m of the milking parlour, block retention was significantly longer for a PS (CowSlip) than a WB (BoviBond) or a FB (Walkease). Potentially, block choice could be directed by the anticipated time to recovery, although a better understanding is required of a suitable endpoint for recovery and the impact that premature loss of support for the contralaterally affected claw may have.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (161.5 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the farmer and the farm staff for their support with this study and the BVScIV SPINE group (2017) for their work on mapping the tracks and creating distance data.

Notes

1 The wooden blocks in the current study were compared to the low-density blocks used by Ranjbar et al. (Citation2021) as the density of Pinus radiata, the main plantation pine in New Zealand, is 380 to 450 kg/m3 (Kimberley et al. Citation2015), lower than the density of the Eucalyptus grandis wood (547 kg/m3) used in the low-density blocks by Ranjbar et al. (Citation2021).

References

- *Anonymous. Hoof-Tite Max-Mix (220 mL) Adhesive Glue Cartridge https://cowcare.eu/product/hoof-tite-max-mix-200-ml-adhesive-glue-cartridge/ (accessed 13 December 2022). CowCare, Valmiera, Croatia, 2022

- Blowey R, Girdler C, Thomas C. Persistence of foot blocks used in the treatment of lame cows. Veterinary Record 144, 642–3, 1999. https://doi.org/10.1136/vr.144.23.642

- Chesterton RN, Lawrence KE, Laven RA. A descriptive analysis of the foot lesions identified during veterinary treatment for lameness on dairy farms in north Taranaki. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 56, 130–8, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2008.36821

- Fiedler A. Klötze kleben – neue Ergebnisse aus der Praxis [Applying blocks – new results from practice]. Abstracts of Modulfortbildung “Funktionelle Klauenpflege und Kontrolle der Klauengesundheit in Milchviehherden.” Pp 12–14. Vetmeduni, Vienna, Austria, 2011

- Kimberley MO, Cown DJ, McKinley RB, Moore JR, Dowling LJ. Modelling variation in wood density within and among trees in stands of New Zealand-grown radiata pine. New Zealand Journal of Forestry Science 45, 22, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40490-015-0053-8

- Klawitter M, Braden TB, Müller KE. Randomized clinical trial evaluating the effect of bandaging on the healing of sole ulcers in dairy cattle. Veterinary and Animal Science 8, 100070, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.vas.2019.100070

- Laven RA, Lawrence KE, Weston JF, Dowson KR, Stafford KJ. Assessment of the duration of the pain response associated with lameness in dairy cows and the influence of treatment. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 56, 210–7, 2008. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2008.36835

- Lischer CJ, Wehrle M, Geyer H, Lutz B, Ossent P. Heilungsverlauf von Klauenläsionen bei Milchkühen unter Alpbedingungen [Healing process of claw lesions in dairy cows in alpine mountain pastures]. Deutsche Tierärztliche Wochenschrift 107, 255–61, 2000

- Lischer CJ, Dietrich-Hunkeler A, Geyer H, Schulze J, Ossent P. Heilungsverlauf von unkomplizierten Sohlengeschwüren bei Milchkühen in Anbindehaltung: Klinische Beschreibung und blutchemische Untersuchungen [Healing process of uncomplicated sole ulcers in tethered dairy cows: clinical description and blood chemistry tests]. Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde 143, 125–33, 2001

- Mason WA, Cuttance EL, Müller KR, Huxley JN, Laven RA. A systematic review on the associations between nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug use at the time of diagnosis and treatment of claw horn lameness in dairy cattle and lameness scores, algometer readings, and lying times. Journal of Dairy Science 105, 9021–37, 2022. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2022-22127

- Mason W, Laven LJ, Cooper M, Laven RA. Lameness recovery rates following treatment of dairy cattle with claw horn lameness in the Waikato region of New Zealand. New Zealand Veterinary Journal 71, 226–35, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2023.2219227

- Mohamaddoust M, Kohansal F, Sangtarash R, Mohamadnia A. به†کارگیری†تخته†های†سم†در†گاوهای†شیری،†اصول†وروش†ها [Hoof blocks in dairy cows: fundamentals and techniques of application]. Eltiam 8, 112–25, 2021

- Nuss K, Tiefenthaler I. Eigenschaften und klinische Anwendung gebräuchlicher Klauenkothurne [Design and clinical applicability of different claw blocks]. Tierärztliche Praxis 28(G), 125–32, 2000

- *Nuss K, Tiefenthaler I, Schäfer R. Design and clinical applicability of different claw blocks. Proceedings of 10th International Symposium on Lameness in Ruminants. Pp 303–4, 1998

- *Perusia OR. Stay on time of orthopedic wooden blocks on cows in extensive feeding system. Proceedings of 14th International Symposium and 6th Conference on Lameness in Ruminants. P142, 2006

- Plüss J, Steiner A, Alsaaod M. Claw block application improves locomotion and weight-bearing characteristics in cattle with foot diseases. Journal of Dairy Science 104, 2302–7, 2021. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2020-19135

- Pyman MF. Comparison of bandaging and elevation of the claw for the treatment of foot lameness in dairy cows. Australian Veterinary Journal 75, 132–5, 1997. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-0813.1997.tb14173.x

- Ranjbar S, Rabiee AR, Reynolds MW, Mohler VL, House JK. Wooden hoof blocks: are we using the right wood? New Zealand Veterinary Journal 69, 158–64, 2021. https://doi.org/10.1080/00480169.2020.1850368

- Sachs MC, Brand A, Gabriel EE. Confidence bands in survival analysis. British Journal of Cancer 127, 1636–41, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41416-022-01920-5

- Sala A, Igna C, Schuszler L. Comparative aspect of pododermatitis circumscripta (sole ulcer) treatment in dairy cow. Bulletin UASVM, Veterinary Medicine 65, 207–11, 2008

- Shearer JK, van Amstel SR. Pathogenesis and treatment of sole ulcers and white line disease. Veterinary Clinics of North America: Food Animal Practice 33, 283–300, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cvfa.2017.03.001

- Shearer JK, Plummer PJ, Schleining JA. Perspectives on the treatment of claw lesions in cattle. Veterinary Medicine: Research and Reports 6, 273–92, 2015. https://doi.org/10.2147/VMRR.S62071

- Stroe TF, Muste A, Beteg F, Dirlea I, Hodis L, Varga R. Observation regarding hoof blocks use in dairy cows. Bulletin UASVM Veterinary Medicine 72, 98–101, 2015. https://doi.org/10.15835/buasvmcn-vm:10961

- Thomas HJ, Miguel-Pacheco GG, Bollard NJ, Archer SC, Bell NJ, Mason C, Maxwell OJR, Remnant JG, Sleeman P, Whay HR, et al. Evaluation of treatments for claw horn lesions in dairy cows in a randomized controlled trial. Journal of Dairy Science 98, 4477–86, 2015. https://doi.org/10.3168/jds.2014-8982

- *Toussaint-Raven ET. Cattle Footcare and Claw Trimming. 3rd Edtn. Pp 75–106. Crowood Press, Marlborough, UK, 2003

- Van Amstel SR, Palin FL, Rorhbach BW, Shearer JK. Ultrasound measurement of sole horn thickness in trimmed claws of dairy cows. Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 223, 492–4, 2003. https://doi.org/10.2460/javma.2003.223.492

- Wehrle M, Lischer CJ, Geyer H, Landerer R, Räber M. Drei Behandlungsmethoden zur Entlastung erkrankter Klauen im Vergleich [Three different techniques of elevating an affected claw in comparison]. Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde 142, 507–11, 2000

- Wiessner F, Wiessner W. Ein orthopädischer Klauenbeschlag beim Rind [An orthopedic claw shoe in cattle]. Wiener Tierärztliche Monatsschrift 38, 251–3, 1951

- *Non-peer-reviewed