ABSTRACT

Aims:

To develop a structured process for a transparent, efficient, high-level review of a low-resource biosecurity system (limited by physical infrastructure, financial, and human resources), in order to identify and prioritise key areas for future focus which could then lead to interventions, tailored by country, to improve the system. A key requirement was that the approach developed was culturally sensitive and respectful to Pasifika people within the country.

Methods:

Animal health and biosecurity systems need to be urgently strengthened by Pacific Island countries and territories (PICTs) if they are to respond to current and future threats. Understanding where additional resources should be allocated to maximise benefit and ensuring buy-in from PICT stakeholders are critical for uptake of any recommendations made. However, there is little available literature on reviewing biosecurity systems, particularly where there is a need for efficiency, simplicity, and cultural sensitivity. A framework was developed through initial in-person consultation between four New Zealand experts who had experience working in international animal health development and support programmes. This was followed by input from informal discussions with selected heads of agriculture in PICTs and included their experiences with previous system reviews, as well as general advice from experts in Pasifika culture. Foundational objectives included simplicity, local inclusivity, and a structured approach, which could be undertaken over a relatively short period of time.

A rapid evidence assessment methodology was used to search the available literature (published and grey, search terms biosecurity, system, Pacific, animal, framework, and review used in AND/OR combinations), to establish an evidence base for other methods of biosecurity system review. The developed framework for review of biosecurity systems in low-resource PICTs was based on elements from expert elicitation frameworks, the SurF surveillance evaluation framework and the Performance of Veterinary Services tool from The World Organisation for Animal Health.

Results:

The developed framework involved bringing stakeholders together in a workshop environment and comprised up to 10 steps including mapping the PICT biosecurity system and exploring attributes of component activities. Understanding the system at a high level enables stakeholders to make informed recommendations on improvements to address future needs. Using the Delphi method, recommendations were then prioritised by stakeholders.

Conclusions and clinical relevance:

A distinctive difference flowing from the use of the needs analysis described in this process was the empowerment of PICT stakeholders to determine their own needs and priorities, rather than have these developed by external parties.

Introduction

Most Pacific Island countries and territories (PICTs) have a shortage of veterinarians and limited resources associated with animal health and biosecurity (Brioudes and Gummow Citation2015, Citation2016; Tukana et al. Citation2016, Citation2018). This shortage has been recognised for some time (Williams Citation2008). More recent analysis by the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO; P. Thornber, pers. comm.Footnote1), determined that in many PICTs there were no government (and/or private) veterinarians. Our own experiences in six Pacific countries (Cook Islands, Tonga, Samoa, Niue, Vanuatu, Fiji) where our programme of support (Animal Biosecurity Pacific Partnership Programme – Ministry for Primary Industries (MPI), NZ) was focused, was that the absence of a veterinary presence was most likely to occur in the smaller Polynesian PICTs (McFadden Citation2023). If there was a veterinary presence, it tended to be associated with short-term missions focused on desexing dogs. No government veterinarians were present in four of the countries listed above. Over the last two decades, there has been either limited or no veterinary presence in these countries; although short-term placements from organisations such as Volunteer Services Abroad (Wellington, NZ) have occurred in some. Thus, in low-resource biosecurity systems such as these (limited by physical infrastructure, financial and human resources), there is limited ability for PICTs to investigate significant animal disease events thoroughly and detect new incursions. In addition, many PICTs have limited in-country diagnostic capability to determine the aetiology of a new animal disease event and thus exclude transboundary animal disease (TAD) and zoonotic or significant production-limiting diseases.

The lack of capability highlights potential risks for managing TAD incursions. Consequently, animal health and biosecurity systems need to be strengthened if PICTs are to respond effectively to current and future threats. However, the dilemma is determining where any additional resources should be allocated within a low-resource biosecurity system to ensure maximum benefit and functionality.

The biosecurity system is defined, in simple terms, as a number of interconnected components that are used to reduce the risk of entry and establishment of exotic diseases. In a broad sense, the biosecurity system can include food safety, animal, plant, environmental, aquatic/marine, and human health (Quinlan et al. Citation2016). Within these categories, it consists of a variable number of components located pre-border, at the border and post-border (including on-farm biosecurity). These components are a series of risk management activities aimed at reducing, but not preventing all incursions (i.e. entry of hazards such as TAD infectious agents). Thus, because risk is never completely eliminated, hazards will continue to enter a country despite the mitigation steps applied. Residual risk is evidenced by incursions and interceptions occurring in countries where a highly functional and robust biosecurity system is in place e.g. the Mycoplasma bovis incursion in New Zealand (MPI Citation2017). Additionally, some risks associated with the introduction of new diseases cannot be eliminated or reduced, e.g. the introduction of highly pathogenic avian influenza associated with wild bird migrations.

A biosecurity system is influenced by both national and international pressures, particularly around trade requirements. Understanding these pressures helps to create an effective and adaptable biosecurity framework. When incursions or events occur, rapid and effective communication between the different components enables early alerts and adjustment of the system towards these threats. Regular system audits, scenario enactments, and a long-term strategic awareness of the likely impact of environmental, climate and social change are all important (Jay et al. Citation2003).

In the PICT context, the biosecurity system, in most cases, is less about enabling exports and more about resilience of smallholders in terms of their general livelihoods and food security (“food sovereignty”). Thus, while the drivers are different, a highly functional, fit-for-purpose system is no less important for PICTs. In the PICTs, impacts on social, economic, cultural, and environmental values are extremely important and while inclusion of these values is implied, it is not explicitly stated.

A tool commonly used to assess biosecurity competence in animal health at the international level is the World Organisation for Animal Health evaluation of the Performance of Veterinary Services (PVS; WOAH Citation2020). The PVS review focuses on critical competencies (including tools and resources) that are necessary for a fully functioning system. However, because it is focused on veterinary services it does not necessarily indicate what other components are present, their relative importance to the country, and where resources could be targeted to have the most benefit based on cultural factors and influences that may be outside the veterinary remit. This is especially relevant for many of the PICTs, as often there is no veterinarian within the relevant government department.

Biosecurity systems are complex and can be difficult and expensive to assess and improve. Here we present a practical and effective structured approach bringing together a range of stakeholders to initially conduct an open, high-level review of the key components and purposes of the PICTs’ biosecurity systems with a view to identifying key areas where intervention and change would be most locally appropriate and effective. The review process we developed had two intended outcomes: to best allocate resources from our programme of support and to identify priorities for PICTs to communicate with other donor and support programmes.

Materials and methods

The framework for system evaluation (presented in the Results section) was put together by four New Zealand experts (“the design team” made up of members of the programme team and other experts) who each had 10 or more years’ experience working in international animal health development and support programmes. Input was received from informal discussions with selected heads of agriculture in PICTs and from their experiences with previous system reviews. Our objective was to develop a simple and efficient structured framework for biosecurity system review that engaged and empowered PICT biosecurity stakeholders to determine their own priorities. The goal was therefore that expert elicitation was focused locally, and external experts did not dictate requirements but facilitated PICT stakeholders to develop recommendations for future support.

A rapid evidence assessment methodology was used to search the available literature (published and grey), in order to establish an evidence base for other methods of biosecurity system review (Khangura et al. Citation2014; Featherstone et al. Citation2015). Databases hosted by CAB Abstracts OVIDSP, ProQuest and Google Scholar were searched using, but not limited to, the terms: biosecurity, system, Pacific, animal, framework, and review, combined using Boolean operators AND, OR. The outputs of the rapid evidence assessment were used by the design team as the foundation for developing the framework presented in the Results section. We identified the PVS as the only current substantive method available for the review of biosecurity systems, although other relevant and allied frameworks can be useful, including the surveillance evaluation framework (SurF) methodology designed for review of surveillance systems (Muellner et al. Citation2018) and the more broad-based structured approach of expert elicitation (Burgman et al. Citation2011; Hemming et al. Citation2017). In developing the review we describe here, foundational objectives included simplicity, local inclusivity, and a structured approach, which could be undertaken over a relatively short period of time.

The main requirement was that the framework that was developed and delivered was culturally sensitive and respectful to Pasifika people within the PICT in question. This was informed by advice from local Pasifika people, experiences of those who had worked with Pasifika people (although not necessarily from the animal health and biosecurity sector) (Tiatia Citation2018; SPC Citation2020) and from our own experiences gained initially in the Cook Islands, but subsequently in several other PICTs.

Results

The review method encompassed elements from expert elicitation frameworks (Burgman et al. Citation2011; Hemming et al. Citation2017), SurF (Muellner et al. Citation2018) and the PVS framework (WOAH Citation2020). The outcome was a series of steps used as the basis for discussion between a broad range of stakeholders (e.g. agricultural ministerial staff, livestock associations, representatives from the human health sector, food safety officials, quarantine staff, secondary and tertiary educators in animal health/agriculture, etc.). Discussions took place in a workshop setting, with time for field work to allow real-time insights into operations of the animal health and biosecurity system ((a)). While representation of stakeholders across the biosecurity system was important, it was not critical that every sector was represented; rather, the intention was to have some diversity, ensuring that a range of perspectives were provided. The aim was a shared outcome that set priorities and a workplan to enhance the country's biosecurity system.

Figure 1. Aspects of the facilitated self-review process used to appraise current and future biosecurity needs in the Pacific Island countries and territories (participants approved use of images). a) Field visits: these enabled an understanding of impediments to the operational aspects of the animal health and biosecurity systems, e.g. animal handling facilities. b) Cultural sensitivity: a member of the programme team plays a traditional nose flute as part of an opening ceremony to the workshop which also included a karakia (prayer) given by the local church minister. c) System mapping: participants of the facilitated self-assessment map the biosecurity system, identifying key component activities to build a picture of strengths, areas for improvements and future needs (Step 5). d) Priority setting: participants voting (anonymously if required) on priority recommendations that had been developed during the final day of workshop sessions using coloured sticky labels to indicate voting preference (Step 9).

Flexibility in the framework was important, to allow space for participants to go deeper into discussion where there was a specific area of interest (rather than being tied to a strict agenda). Inclusion of hospitality was another important cultural element (time allocated for introductions and getting to know one another, as well as provision of local food). Christian culture was also incorporated into the programme (the workshop started with a prayer and a blessing of any recommendations made at the end of the meeting). Inclusion of a musical item at the start also set the tone of the meeting, greatly assisted by having a Pasifika member of the programme team conducting the facilitation ((b)).

Another consideration was that the “review” needed to be viewed as providing encouragement to PICT stakeholders, rather than criticism, or overt negativity. A secondary goal was to create engagement and awareness of the country’s biosecurity function. We considered that stakeholders gaining an understanding of all parts of the biosecurity system was an integral part of the process. One way to facilitate and demonstrate this was to map the system and thus create a holistic view of how it could be improved. We also considered it important that in-country subject matter experts led the discussion on what was needed, rather than using a formulaic diagnostic process. Thus, outcomes produced from the workshop originated from stakeholders rather than an external consultant. The rationale for this approach was that long-term change was more likely to occur if there was motivation internally. Hence, “facilitated self-assessment” best characterises the method we describe here.

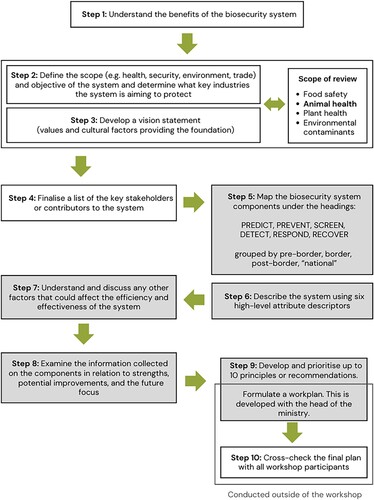

A summary of the steps used to review the PICTs’ biosecurity systems is provided below and in . While the steps are presented linearly, there were occasions, based on discussion amongst workshop participants, when there were grounds for skipping some or changing their order. At each step, information was summarised and presented back to stakeholders to ensure the discussion was widely understood and steps accurately characterised.

Figure 2. High-level working conceptualisation of the biosecurity system review method used to appraise current and future biosecurity needs in Pacific Island countries and territories. While presented linearly (Steps 1–10), the order can be varied, and all steps may not be needed in every situation. Shaded boxes indicate tasks that were carried out by individual participants, for example, using sticky notes to communicate their contributions to the wider group.

Step 1. Understand the benefits of the biosecurity system

Initial discussions were around defining what an effective biosecurity system is. We recognised that biosecurity is a relatively new term and is often used to refer to farm-level measures and biosecurity practices carried out to mitigate pathogen entry at the border, e.g. customs checking, rather than a holistic country-level system that includes many different components (at the border as well as those from pre- and post-border).

Participants were asked to consider the relative value of biosecurity in relation to other competing country-level needs and how improvements in the system could change livelihoods and the health status of people. This step was designed to ensure that any changes reflected the aims and needs of the participants rather than the external programme team.

Step 2. Define the scope (e.g. animal health) and objective of the system and determine what key industries the system is aiming to protect

Among the wide range of activities covered by “biosecurity”, this section of the workshop was designed to help participants identify the key areas they wanted to focus on for their country. Generally, the scope was limited to animal health; however, the workshop session aimed to draw out the connection between animal, human, and plant health, food safety and the environment. For emergent systems, a narrow focus removes the complexity of trying to understand the robustness required in a system designed to deal with such diverse threats as food safety and environmental contaminants.

Step 3. Develop a “vision statement”

In this early stage of the workshop, participants were asked to share some of the personal values that were important to them, e.g. a respect for all viewpoints, listening, sharing honestly, perseverance when progress is slow. These values helped guide facilitators through the workshop, but also beyond, during the delivery phase when a workplan had been developed. Based on discussions around the benefits of biosecurity and discussion of what aspects of the system the PICT stakeholders were “most proud of”, a vision statement was developed for the biosecurity system. An example of a vision statement that was developed by one of the PICTs was: “A connected and skilled biosecurity service that is trusted and engages with Island communities to protect their health and livelihoods”. Developing a vision statement assisted participants to reach an agreement on the purpose of the system they were part of.

Step 4. Finalise a list of the key stakeholders or contributors to the system

By understanding contributors to the system, e.g. primary, secondary, and tertiary educators, farming associations, welfare organisations, members of the human health sector, regional agencies such as the FAO, Secretariat for the Pacific Community, etc., any parts of the biosecurity system not represented at the workshop could be identified.

Step 5. Map the biosecurity system

Participants were called upon to describe the system, including a stocktake of its constituent parts and how they fit together (including government and non-government components) (c). These components were grouped under the categories pre-border, border, post-border (Dodd et al. Citation2020), and an additional descriptor “national”. The “national” group provides a general perspective of the biosecurity system that does not fit into risk management activities located in relation to the border. It incorporates supportive functions such as the overarching vision, cohesion, and connectivity between components. It also includes legislation and how it is enforced, and whether there are other factors (e.g. cultural) that influence its enforcement. The mapping was conducted with poster-size paper (A0). Stakeholders then identified component activities and provided a brief description of each using sticky notes. While we provide some examples of component activities, there are many others not listed that are used in biosecurity systems.

Predict (pre-border): anticipate something happening in the future, e.g. risk assessments, risk pathway analysis (MPI Citation2017).

Prevent (pre-border): stop introduction of disease/pests, e.g. import health standards, trade agreements, biosecurity intelligence, trade, and bilateral agreements.

Screen (border): check that there is no risk, e.g. quarantine and transitional facilities.

Detect (post-border): look for disease/pests, e.g. surveillance programmes, diagnostic capability.

Respond (post-border): control disease if there are outbreaks, e.g. preparedness and response systems.

Recover (post-border): recovery needs after an outbreak, long-term disease control programmes (e.g. bovine tuberculosis or brucellosis eradication programmes).

Step 6. Describe the system using six high-level system attribute descriptors

This is an additional step that can be useful for assessment of certain key components and is conducted in parallel with Step 5 above. The system is described at either the component level, e.g. animal disease surveillance, or at the group level (e.g. border, post-border, etc.). The use of the attribute descriptors (see below) enables the component to be described and understood in a systematic way and helps to determine its value to the overall biosecurity system. We chose to adopt and modify some of the high-level attributes, used in the review method developed for the assessment of a surveillance system (SurF; Muellner et al. Citation2018). In brief, the attribute descriptors used were:

Organisation and management: how biosecurity is organised and managed within the component, e.g. through an organisational diagram.

Resources: critical resources present that enable the processes within the component to function, including infrastructure; tools and equipment; financial resources; field capability; access to essential resources (not necessarily located in the country).

Technical/people: matching of available skills with minimum requirements needed for the component to function effectively.

Information management and processes: the use and documentation of data/information collection, management, verification of data, storage, and analysis.

Outputs: the outputs from components and how these were measured.

Impacts/outcomes: the benefits from activities associated with the component. These benefits could be monetary, non-monetary, direct, or indirect.

Step 7. Understand and discuss any other factors that could affect the efficiency and effectiveness of the system

Understanding these factors, e.g. disconnects between government staff and farmers/villagers, or political sensitivities influencing application of activities within the system, requires some sensitivity and only comes about through development of relationships. Hence, participants were asked to provide this information outside a set session and not necessarily publicly, to all participants. The values of respect and trust (and other values participants identified as being important) are a key part of participants feeling sufficiently comfortable to share this type of information. Thus, sharing may only occur in the later stages of the workshop or even after it has concluded.

Step 8. Examine the information collected on the components in relation to strengths, potential improvements, and the future focus

The strengths of the biosecurity system included some cultural aspects that could influence high-level performance in certain areas. Potential improvements (or weaknesses, although we preferred not to use this term) were areas where additional focus could improve performance. We were mindful that it may not be feasible to improve some of “weaknesses” with the available resources and that it can be a more efficient use of these resources to focus on improving strengths. Alternatively, stakeholders were given the option to consider whether any areas for potential improvement could be addressed at a regional Pacific level. Future focus incorporated horizon scanning, adaptability, and the flexibility of the system to respond to future needs.

Step 9. Develop and prioritise up to 10 principles or recommendations

Information on the strengths, areas of potential improvement and future needs of components was used by stakeholder participants to develop and rank recommendations ((d)). Ranking followed a Delphi process (Dalkey and Helmer Citation1963) involving two rounds of voting by participants. The second round of voting gave individuals an opportunity to change their votes after observing how other participants had voted. Natural separation of rank scores could be used to identify immediate priorities and 3–4 recommendations that could be used to focus future biosecurity enhancement activities and inputs for the programme (see McFadden et al. Citation2016). Based on the recommendations, a workplan was developed with the head of the PICT ministry and their key advisors (outside the workshop) that mapped out some of the activities to be undertaken. This step was about turning the recommendations into specific actions.

Step 10. Cross-checking the final plan with all workshop participants

The final step was about ensuring that workshop outputs and priorities for any future activities were relevant and appropriate internally, could be operationalised and were sustainable. This step was carried out independently by PICT stakeholders.

Discussion

Drawing influences from Pasifika culture and a number of recognised frameworks, we have described a simple, stepwise, and efficient method of reviewing a complex system. The framework (and the series of steps outlined) brought PICT stakeholders to a common understanding of their own system so that they were empowered to make informed recommendations on future priorities. Managing the review in this way removed bias from external experts and ensured that there was ownership of the recommendations made.

Our focus on ensuring that the way the review was conducted fitted with Pasifika culture was an important part of the framework. In low-resource countries with emergent biosecurity systems, comprehensive reviews that make comparisons with international standards will always highlight gaps that cannot be filled with the available resources (either sourced within the country or from external donors). Hence, the country-specific context and feasibility of what can be achieved has to be considered. While at an academic level, we may externally assess a need, if the cultural perspectives and other country-specific aspects of the need (e.g. logistics associated with widely dispersed island nations) are not accounted for, the improvement may not necessarily be valued or practically achievable and therefore not sustained in the long term. We were also mindful of how many resources are necessary to conduct a review, as these can be considerable and, paradoxically, lessen the resources available for system improvements.

For a biosecurity system to be functional, a base set of component activities was considered essential. However, the philosophy was that not all components that are part of a sophisticated system are required when resources are limited. The concept was to work with the biosecurity components already present in the country, rather than to introduce or create new ones that are not necessarily fully supported by other system components, for example, provision of a laboratory without the necessary resources to equip it to run effectively. Generally, the presence of a veterinarian or animal health laboratory is considered to be a minimum requirement in sophisticated biosecurity systems, but within the PICTs this requirement needs to be addressed in other ways, for example via real-time or online veterinary support and provision of diagnostic testing for critical and high-impact agents in another country.

High-profile concerns such as the risk of African swine fever entering the region in March 2020, or the foot and mouth disease outbreak in Indonesia in March 2022, although highly relevant as case examples, can draw a lot of focus, distracting animal health authorities from foundational needs to improve generic system components. The review framework described here focuses on developing key priorities for the immediate period within an adaptable framework that can change as the programme is rolled out and skills developed.

Brioudes et al. (Citation2015) identified that priorities may not align between experts such as animal health officers and farmers, pointing to the need for wide engagement from multiple stakeholders when developing a prioritisation framework. We are mindful that there is a potential weakness through reliance on stakeholders who attend the workshop, and of social or work hierarchies that may exist or develop within a group dynamic, potentially biasing the final recommendations reached. The approach described here encouraged wide participation and brought cultural awareness to the forefront, to develop a shared outcome, within an environment where all contributions were valued. Using open questions, facilitated whiteboard sessions, small group exercises and feedback sessions, we aimed to limit an individual’s or group’s dominance. We are also aware that we will not have addressed all cultural considerations. In this respect, a good illustration of this occurred in the Kingdom of Tonga where we were fortunate enough to have the assistance of a Tongan veterinarian as a facilitator. This provided tremendous extra value as we were able to include within the programme team a member who understood and was part of the local context and was aware of the cultural sensitivities within the country under review.

A multidisciplinary approach to biosecurity has been advocated, with co-operation across stakeholders from government agencies, industry, the community, education, and science (Lott and Rose Citation2016). The process whereby individuals all contributed equally, irrespective of their level of education, years of service, etc., created a voice for each attendee, helping to eliminate peer-pressure and individual dominance when it came to setting priorities for future work.

A key part of the method we describe is efficiency; however, more comprehensive and systematic methods may uncover nuances where focus should be applied that this method may not detect. As with all reviews, a key outcome is actions resulting from the review that are carried out, as well as evidence that the biosecurity system has improved following recommended changes. Future analysis would be of value in examining these factors, both for this review method and for others that might be used currently.

Over and above the process we describe, it is important to develop connections as the basis for future support in the form of a partnership model, thus providing a seamless transition from needs analysis to delivery of support. Both informal and formal (survey questionnaire) feedback from the heads of agriculture in our country partners has been extremely positive and we encourage others to adopt this style of system review in working with developing countries in other contexts.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr. Petra Muellner (Epi-Interactive) and Dr. Sarah Rosanowski for guidance and comments provided to the authors. In addition, our many Pasifika advisors, including Dr. Tasa Havea (Professor of Pacific Studies, Massey University), Heads of PICT Agricultural Ministries (particularly Mrs. Temarama Anguna-Kamana, Cook Islands; and Mrs. Ana Pifeleti, Tonga), and MPI staff who have had a long history of working with Pasifika people (Melaia Lousi, Julia Umaga, Disna Gunawardana, Lalith Kumarasinghe and the late Ryan Donavon) – we have benefited greatly from their input into this piece of work and the programme as a whole. The authors also acknowledge funding for the Pacific Partnership Programme for Animal Biosecurity provided by the New Zealand Ministry for Foreign Affairs and Trade (MFAT).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 P Thornber, Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, Canberra, Australia, 2020

References

- Brioudes A, Gummow B. Field application of a combined pig and poultry market chain and risk pathway analysis within the Pacific Islands region as a tool for targeted disease surveillance and biosecurity. Preventive Veterinary Medicine 129, 13–22, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.prevetmed.2016.05.004

- Brioudes A, Gummow B. Understanding pig and poultry trade networks and farming practices within the Pacific Islands as a basis for surveillance. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 64, 284–99, 2017. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12370

- Brioudes A, Warner J, Hedlefs R, Gummow B. Diseases of livestock in the Pacific Islands region: setting priorities for food animal biosecurity. Acta Tropica 143, 66–76, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.actatropica.2014.12.012

- Burgman MA, McBride M, Ashton R, Speirs-Bridge A, Flander L, Wintle B, Fidler F, Rumpff L, Twardy C. Expert status and performance. PLoS One 6, e22998, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0022998

- Dalkey N, Helmer O. An experimental application of the DELPHI method to the use of experts. Management Science 9, 458–67, 1963. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.9.3.458

- *Dodd A, Stoeckl N, Baumgartner J, Kompas T. Key Result Summary: Valuing Australia's Biosecurity System. https://cebra.unimelb.edu.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/3535013/CEBRA_Value_Docs_KeyResultSummary_v0.6_Endorsed.pdf (accessed 10 September 2020). Centre of Excellence for Biosecurity Risk Analysis, Melbourne, Australia, 2020

- Featherstone RM, Dryden DM, Foisy M, Guise J, Mitchell MD, Paynter RA, Robinson KA, Umscheid CA, Hartling L. Advancing knowledge of rapid reviews: an analysis of results, conclusions and recommendations from published review articles examining rapid reviews. Systematic Reviews 4, 50–58, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0040-4

- Hemming V, Burgman MA, Hanea AM, McBride MF, Wintle BC. A practical guide to structured expert elicitation using the IDEA protocol. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 9, 169–80, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/2041-210X.12857

- Khangura S, Polisena J, Clifford TJ, Farrah K, Kamel C. Rapid review: an emerging approach to evidence synthesis in health technology assessment. International Journal of Technology Assessment in Health Care 30, 20–27, 2014. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0266462313000664

- Lott MJ, Rose K. Emerging threats to biosecurity in Australasia: the need for an integrated management strategy. Pacific Conservation Biology 22, 182–8, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1071/PC15040

- Jay M, Morad M, Bell A. Biosecurity, a policy dilemma for New Zealand. Land Use Policy 20, 121–9, 2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0264-8377(03)00008-5

- *McFadden AMJ. Pacific partnership programme in animal health and biosecurity. Surveillance 50, (3), 91–94, 2023

- McFadden AMJ, Muellner P, Baljinnyam Z, Vink D, Wilson N. Use of multicriteria risk ranking of zoonotic diseases in a developing country: case study of Mongolia. Zoonoses and Public Health 63, 138–51, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1111/zph.12214

- Muellner P, Watts J, Bingham P, Bullians M, Gould B, Pande A, Riding T, Stevens P, Vink D, Stärk K. SurF: an innovative framework in biosecurity and animal health surveillance evaluation. Transboundary and Emerging Diseases 65, 1545–52, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1111/tbed.12898

- *MPI. Analysis of Risk Pathways for the Introduction of Mycoplasma bovis into New Zealand. https://www.mpi.govt.nz/dmsdocument/28050/send (accessed 1 November 2023). Ministry for Primary Industries, Wellington, NZ, 2017

- *Quinlan M, Alden J, Lutz Habbel F, Murphy R. The Biosecurity Approach – A Review and Evaluation of its Application by FAO, Internationally and in Various Countries. https://www.ippc.int/static/media/files/irss/2016/09/09/Review_of_biosecurity_approaches_FINAL_report.pdf (accessed 1 September 2020). The International Plant Protection Convention, Rome, Italy, 2016

- *SPC. Cultural Etiquette in the Pacific: Guidelines for Staff Working in Pacific Communities. https://hrsd.spc.int/sites/default/files/2021-07/Cultural_Etiquette_in_the_Pacific_Islands_0.pdf (accessed 21 June 2021). Secretariat for the Pacific Community, Noumea, New Caledonia, 2020

- *Tiatia J. Pacific Cultural Competencies: A Literature Review. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/documents/publications/pacific-cultural-competencies-may08-2.pdf (accessed 1 September 2020). Ministry of Health, Wellington, NZ, 2018

- Tukana A, Hedlefs R, Gummow B. Brucella abortus surveillance of cattle in Fiji, Papua New Guinea, Vanuatu, the Solomon Islands and a case for active disease surveillance as a training tool. Tropical Animal Health and Production 48, 1471–81, 2016. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-016-1120-8

- Tukana A, Hedlefs R, Gummow B. The impact of national policies on animal disease reporting within selected Pacific Island Countries and Territories (PICTs). Tropical Animal Health and Production 50, 1547–58, 2018. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11250-018-1594-7

- *WOAH. OIE Tool for the Evaluation of Performance of Veterinary Services. https://www.woah.org/app/uploads/2021/03/2019-pvs-tool-final.pdf (accessed 14 September 2020). World Organisation for Animal Health, Paris, France, 2019

- *Williams V. Critical veterinary shortage in Pacific Islands. MAF Biosecurity NZ 84, 14, 2008

- *Non-peer-reviewed