ABSTRACT

In Indonesia, Islamic ‘counter-terror culture’ contests Islamic ‘radicalization’. Indonesia’s largest Muslim organization, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), takes a leading role in initiating counter-terror culture. Central to their initiatives are ideas about ‘Islam Nusantara’ (Islam of the Archipelago). This article analyzes two NU initiatives: (1) the documentary Rahmat Islam Nusantara (2015), which challenges how ‘radical’ groups interpret the Quran, and (2) the ‘cyber warrior initiative’ in which volunteers contest ‘radicalism’ on social media. The article explores how these initiatives construct ‘counternarratives’ that frame Islam Nusantara as antidote against ‘radicalism’ and analyzes how, in doing so, these initiatives negotiate the binary frame between ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ Islam. The article proposes that Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyber warriors uphold this binary frame and that meanwhile, these initiatives are marked by an aesthetics of authority, which constructs traditional figures of Islamic authority as role models who can help protect the country against radicalism.

Counter-terror culture in Indonesia

In 2014, Nahdlatul Ulama (NU; Revival/Awakening of Ulama), Indonesia’s largest independent Islamic organization launched a global anti-extremism campaign. NU’s stated goal is ‘to spread messages about a tolerant Islam (Islam toleran) to curb radicalism, extremism and terrorism’, which, it claims, ‘often spring from a misinterpretation of Islamic teachings’ (Varagur Citation2015). ‘Tolerant Islam’ here refers to Islam Nusantara (‘Islam of the Archipelago’), a syncretic Javanese form of Islam. To curb ‘radical’ Islam (Islam radikal) and to promote Islam Nusantara, NU has embraced media. Two media initiatives form a prominent part of NU’s anti-extremism campaign: the documentary film Rahmat Islam Nusantara (2015)Footnote1 and the so-called ‘cyber warrior’ initiative.

The 90-minute documentary film Rahmat Islam Nusantara was produced by NU and explores the development of Islam in Indonesia. It includes interviews with Indonesian Islamic scholars, who systematically criticize ISIS’ interpretations of the Qur’an and the hadith. The ‘cyber warrior’ initiative aims to counter ‘radicalism’ online. Cyber warriors are volunteers who are trained by NU to contest terrorist organizations online with memes, comics, and videos. In a news article, Krithika Varagur (Citation2016) explains that these volunteers call themselves ‘cyber warriors’, a play on ‘the Muslim Cyber Army’ (both groups use English names). The Muslim Cyber Army is a self-proclaimed Indonesian cyber-jihadist network, which uses hacking, fake news, and hate speech to impact government politics and push Indonesia in a more conservative direction (Juniarto Citation2018). Cyber warriors are often young Indonesians who spend hours a day promoting Islam Nusantara and challenging terrorist organizations (Varagur Citation2016). The content created by cyber warriors often features NU kyai (religious teachers in Islamic boarding schools) and ulama (religious scholars respected for their knowledge of Islam) in prominent roles.

Critics (Cochrane Citation2015; Varagur Citation2016) have praised Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyber warrior initiative for their potential to challenge ‘radical’ thought by constructing ‘counternarratives’. Tuck and Silverman (Citation2016) define counternarratives as stories ‘that offer a positive alternative to extremist propaganda, or alternatively aim to deconstruct or delegitimize extremist narratives’ (2). In this article I ask: How does NU try to counter Islamic ‘radicalism’ and promote Islam Nusantara by means of the documentary film Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyber warrior initiative? And related to this main question, I ask: What kinds of narratives can be distinguished, what do these narratives tell about Islam, and how do these narratives construct ‘radical’ Islam in opposition to Islam Nusantara?

This article explores these questions by conducting a visual and narrative analysis of Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyber warrior initiative. I propose that these two initiatives are marked by what I call an aesthetics of authority. An aesthetics of authority is a specific aesthetic mode, which constructs and legitimizes a chain of religious authority. This chain forms the basis for the construction of counternarratives in which saints, kyai, and ulama feature as exceptionally inspirational authoritative figures, to which one needs to listen in troubling times as they become an antidote to extremist thought. This aesthetics, which comprises both (audio)visual and written elements, can be seen as underpinning an intervention of NU in the debate about the fragmentation of religious authority. A number of scholars (Hoesterey Citation2007, Citation2012; Turner Citation2007) have shown that there is a fragmentation of religious authority. In comparison to the end of the 19th century, religious authority is no longer the sole domain of the ulama (Kaptein Citation2004, 128). In Indonesia, new voices have recently entered religious debates, and they often differ from the formally trained religious authorities. These new figures of piety are largely self-trained, independent, and charismatic (Schmidt Citation2018a, 62). This means that people – including would-be-‘radicals’ – can now find their own information, for instance online, thereby bypassing traditional figures of authority. This article shows how through an aesthetics of authority, the initiatives (re)claim religious authority and restore the saints, kyai, and ulama as the most important sources of knowledge.

In studies of counternarratives, scholars have mostly focused on narratives that are aimed at deradicalization and are targeted at already ‘radicalized’ individuals (Grossman Citation2014). At the same time, (counter) terrorism researchers such as Christina Nemr (Citation2016) and Cristina Archetti (Citation2013) critically addressed that targeting ‘radicalized individuals with the right message is a waste of time’ (231). As Archetti explains:

The reason why ‘our’ narrative is not having any effect on the extremist mind-set is that ‘our message’ is filtered through a very different personal narrative, grounded in a specific constellation of relationships. In this perspective, communication, counter-intuitively, is most effective not directed at the terrorists or violent extremists, but around them (Citation2013, 231, emphasis in original).

Islam Nusantara and NU

Almost 90% of Indonesia’s 250 million inhabitants identifies as Muslim. This community is often understood in terms of two orientations of Islam – traditionalist and modernist Islam – that are in a dialogical relationship (Schmidt Citation2018b, 9). ‘Traditionalist Islam’, also known as ‘Islam Nusantara’, ‘Javanese Islam’ is a Sufi-inspired orientation and is often generalized in NU discourse as ‘Indonesian Islam’, thereby ignoring the subtle differences between them. It is a hybrid form of Islam developed particularly on Java, since the 16th century, where it gradually mixed with adat (customary law), Hinduism, Buddhism, and Javanese mystical practices (Weintraub Citation2011, 3–4). Although it is often seen as exclusively ‘locally’ developed Islam, it is part of the global, through flows of information, people, and cultural forms. Already in the second half of the 19th century many Javanese went on the pilgrimage to Mecca, studied Islam abroad, and brought new ideas back to the archipelago (Kruithof Citation2014, 50).

Alongside traditionalist Islam, ‘modernist Islam’ developed. This version of Islam, sometimes also called ‘scripturalist Islam’ strives for literal interpretations. Modernists aim to purify their faith and desire an Islam that is free from cultural accretions. The organizations associated with these orientations of Islam (NU for traditionalists and Muhammadiyah for modernists) are the most influential Islamic forces in Indonesia. NU is, with an estimated 45 million members, the largest Sunni Islamic organization (Muhammadiyah has an estimated 29 million members). NU was founded in 1926 by Islamic theologians, who claimed to be the heirs of the Walisongo, the nine Sufi saints who are believed to have introduced Islam to Java.

Since 2015, NU has promoted Islam Nusantara as an alternative form of a ‘global Islam’, which according to NU, is dominated by Arabic or Middle Eastern perspectives. NU has started to promote Islam Nusantara as ‘moderate Islam’ (wasathiyyah Islam, ‘middle way’ Islam), which they see as having the potential to counter Islamic ‘radicalism’. The term ‘Islam Nusantara’ has been in circulation for decades, and has been used by NU and Muhammadiyah, but NU has given the concept a far more specific focus, using it to extol the virtues of a culturally sensitive and predominantly Javanese Islamization and to reject what it sees as Arabized forms of Islam, such as Salafism and Muslim Brotherhood-style Islamism.

It should be noted here that the terms ‘radical’ and ‘moderate’ are contested terms. ‘Radicalism’ is usually seen as a threat to the multi-religious, multi-ethnic Indonesian nation (Cochrane Citation2015). The words ‘radical’ and ‘moderate’ rather loosely refer to a number of practices. One does not have to be involved in violent practices to be called ‘radical’. In public discourse, the degree of Indonesia’s Islamic moderatism is frequently determined by the ways in which Muslims approach the Qur’an and the hadith. Those who rely heavily on context in understanding the texts have been referred to as ‘moderate’ Muslims. On the other side, those who employ a literal or hardline approach can in public discourse be considered ‘radical’ (Hilmy Citation2013, 34). Both ‘radical’ and ‘moderate’ Islam thus have multiple, shifting meanings.

At its 2015 annual congress, NU officially adopted Islam Nusantara as a conceptual pillar, both domestically and internationally (Fealy Citation2018). To aid Islam Nusantara’s global promotion, NU has created a hub for international activities in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. NU has also established branches in Germany, France, the UK, Belgium, Russia, and Spain and works with the University of Vienna, which collects and analyses ISIS propaganda, to prepare responses to those messages (Cochrane Citation2015).

NU’s endeavor to promote ‘moderate Islam’ as an alternative to a perceived foreign threats Islam is not new, and must be positioned in a longer history. During the colonial era, the Dutch feared that pan-Islamic sentiments would fuel resistance (Burhanudin Citation2014, 30). The Dutch aimed their policies at restraining Muslim ‘fanaticism’ and sought to maintain order by emphasizing local beliefs (Kruithof Citation2014). ‘Moderate Islam’ has been an important part of foreign diplomacy for almost two decades. Hoesterey (Citation2020) observes that although ‘Indonesia is not an Islamic state, its politicians and religious civil society leaders have nonetheless incorporated religion into its foreign policy and public diplomacy agenda’ (194). ‘Moderate’ Islam here becomes part of a soft power approach to foreign policy (Nye Citation1990), which refers to coercing others through cultural exchange and shared political values to shape their attitudes (Hoesterey Citation2020, 194). The role ‘moderate’ Islam plays in foreign policy is influenced by each political regime, international politics, and the agendas of domestic Islamic non-state actors – like NU – whose role in influencing foreign policy was made possible by democratization after the fall of the Suharto regime in 1998 (Umar Citation2016, 399). In this sense, the state is thus not the only actor to determine the image of ‘moderate’ Islam that is domestically and internationally communicated.

While under the administrations of Sukarno (1957–1966) and Suharto (1966–1998), Islam played a minor role (Umar Citation2016, 402), ‘moderate’ Islam, played a significant role in Indonesia’s foreign policy after 9/11. The global war on terror divided the world in an ‘us’ versus ‘them’, in allies and enemies of the US, and in ‘good’ Muslims and ‘bad’ Muslims (Mamdani Citation2002). This division between ‘good’ Muslims and ‘bad’ Muslims significantly transformed Indonesia’s foreign policy. Umar (Citation2016) points out that after 9/11, Indonesia ‘as a country on the path to democracy […] attempted to sell its moderate and democratic image of Islam to gain external support’ (401–402). The domestic and international promotion of ‘moderate’ Islam began after the 2002 Bali bombings (Umar Citation2016, 402). Following these attacks, then-president Megawati signed defence agreements with the US government, making Indonesia part of the US-led war on terror (Umar Citation2016, 419). She also started to promote ‘moderate’ Islam as the ‘official face of Indonesian Muslims’ (419). Under president Yudhoyono (2004–2014), the promotion of ‘moderate Islam’ as the main image of Indonesian Islam became top priority (402). During both presidencies, ‘moderate Islam’ was politicized: it was inserted into in a liberal democracy discourse, which reproduced notions of ‘good’ Muslims, those who fit in liberal democracy discourse, and ‘bad’ Muslims those who are against liberal democracy (402).

Indonesian Islamic organizations, like NU, also influenced foreign policy and thus the ways in which ‘moderate’ Islam became part of Islamic soft power. Hence, ‘moderate’ Islam was inflicted with local meanings as well. Umar (Citation2016) observes that ‘even though the driving factor did not solely come from the “internal” discourse of Indonesian Islam, the growing expectation to articulate and promote moderate Islam has given momentum for some Islamic groups to involve themselves in the campaign’ (421). Hoesterey (Citation2020) writes that Indonesian ‘moderate’ Islam is both championed for domestic consumption within Indonesia, ‘often as a reminder of the pride that Indonesians should feel about their everyday commitment to leading virtuous noble lives’, while at the same time it is ‘part of a broader diplomatic campaign that reflects Indonesia’s own geopolitical aspirations on the global stage’ (Hoesterey Citation2020, 198). The project of promoting ‘moderate’ Islam has thus been shaped by local agendas and international politics.

The current president Joko Widodo (2014-present) supports NU and Islam Nusantara. Although NU is an independent organization, it has strong ties to the government. As Greg Fealy (Citation2018) explains,

NU has a record number of members in cabinet while it enjoys close relations with the president […] NU receives money from the state. In a move to buttress his support within the Muslim community the president has assiduously cultivated NU. (Fealy Citation2018)

(Counter)narratives about ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ Islam

Before analyzing what kinds of counternarratives are constructed in Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyber warrior initiative, it is important to look more closely at the term (counter)narrative itself.

Media scholar Jonathan Bignell (Citation2004) points out that narratives are usually understood as stories. In the realm of media, a narrative is ‘an ordered sequence of images and sound that tells a fictional or factual story’ (86). As the term ‘counternarrative’ already reveals, this specific kind of narrative only make sense in relation to something else, namely to the things it is countering. Counter-terrorism scholars Tuck and Silverman (Citation2016) define counternarratives as stories ‘that offer a positive alternative to extremist propaganda, or alternatively aim to deconstruct or delegitimize extremist narratives’ (2). Although this definition has normative connotations that I do not uncritically adopt, I argue that the term ‘counternarratives’ is useful to shed light on how the two initiatives imagine solutions, and to analyze the reactive nature of these narratives.

What is important is that narratives are social constructions. Sociologist and media scholar Stuart Hall (Citation1997) explains that we produce ‘meaning’ through language. This means that we make sense of our identity, of who we are, through language (Hall Citation1997, 3–4). ‘Meaning is constantly being produced and exchanged in every personal and social interaction in which we take part’ (Hall Citation1997, 3). Media, as social and discursive expressions and constructions also produce meanings, which people can ‘consume or appropriate to give them value or significance’ (Hall Citation1997, 3–4). In Critical Approaches to Television (Citation2004), Leah Vande Berg stresses: ‘human beings construct their understandings of themselves and their lives, their immediate environments, and even worlds outside their direct experience, through stories’ (198). By using narratives, people construct coherence in the world and guides for living within it. And since narratives are central to how we understand the world, ourselves, and others, they are according to Vande Berg: ‘important avenues toward understanding a society’s culture – how it sees itself valuatively and characterologically, where it sees itself coming from and tending toward’ (Citation2004, 198). Narratives thus give insight into the ways in which a society envisions itself and others – and therefore merit critical study. Counternarratives not only provide insight into the ways a society envisions itself and others, but also how the communicator (NU), envisions solutions to the things the narratives are countering.

Narratives, in being human (re)constructions of the world, can never be objective or neutral, but are always ideologically charged. Like any other narrative, a counternarrative should be seen and analyzed as a specific subjective (re)construction of the world, its inhabitants, its cultures and religions. This is what I aim to do here when analyzing how in Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyber warrior initiative counternarratives are constructed through (audio)visual and textual techniques – such as sound, cinematography, commentary, and editing – I will pay attention to how Islam features in their counternarratives.

I suggest that Rahmat Islam Nusantara constructs a counternarrative by setting ‘local’ ‘moderate’ Islam Nusantara apart from a perceived ‘foreign’ ‘radical’ Wahhabi Islam, thereby upholding a binary frame of ‘radical’ versus ‘moderate’ Islam. One of the differences between Islam Nusantara and ‘foreign’ Islam according to Rahmat Islam Nusantara is self-knowledge and self-discipline. The documentary frames these as important teachings of Islam Nusantara. It suggests that self-discipline and self-knowledge make someone a ‘good Muslim’ and that these qualities prevent violence. Rahmat Islam Nusantara however does not elaborate on how to exactly know/discipline oneself. I suggest that the cyber warrior initiative does do so by advising followers to work on themselves – to be(come) ‘good’ Muslims. By distinguishing between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Islam, I suggest that the initiatives do what Mamdani (Citation2002) has warned against: ‘differentiating good Muslims from bad Muslims, rather than terrorists from civilians’ (766), which turns religious experiences into political categories. As I will propose, religious experience becomes the basis on which Islam Nusantara-supporting kyai, ulama, and Muslims themselves are made responsible for protecting a ‘peaceful’ practice of Islam.

Rahmat Islam Nusantara: saints and sinners

The documentary film Rahmat Islam Nusantara, produced by NU, explores the history of Islam in Indonesia. The film shows how Indonesian Muslims today remember the so-called Walisongo (nine saints) movement, which is believed to have precipitated the development of Islam in the archipelago. In the film, Indonesian Islamic scholars, particularly those affiliated with NU, explain how the teachings of these nine saints are central to Islam Nusantara, which according to the documentary stands for peace and tolerance (Siswo Citation2015). As these scholars explain the theology and origins of Islam Nusantara, they also denounce Islamic State and Wahhabi fundamentalism by explaining why their interpretations of religious texts are wrong. The film was well received in Indonesia and has gained international critical acclaim from cultural critics of The New York Times (Cochrane Citation2015), The Australian (Alford Citation2015) and The Huffington Post (Varagur Citation2015) and has been praised as ‘a Muslim challenge to the ideology of the Islamic State’ (Cochrane Citation2015).

I propose that Rahmat Islam Nusantara is marked by an aesthetics of authority. I suggest through its narrative and visual practices, the documentary constructs a binary opposition between ‘local’ Indonesian Islam and ‘foreign’ Wahhabi Islam. This binary opposition works to create a counternarrative in which Islam Nusantara is seen as an antidote to ‘radicalism’, and in which there are two aspects of Islam Nusantara that specifically challenge ‘radicalism’. These are: Islam Nusantara’s presumed adaptability to local circumstances and its emphasis on self-knowledge and discipline. Rahmat Islam Nusantara connects these aspects to the legacy of the Walisongo and creates a chain of religious authority. It constructs the ulama as authoritative figures who can pass on the legacy and knowledge of the Walisongo. Viewers are encouraged by ulama to adopt the Walisongo as their role models and work on themselves to improve their self-knowledge as the documentary suggests that self-discipline makes one a ‘good Muslim’ and prevents violence. In this way, not only ulama are held responsible for the practice of peaceful Islam, but also viewers themselves.

Rahmat Islam Nusantara constructs an opposition between ‘local’ Indonesian Islam and ‘foreign’ Wahhabi Islam on two narrative levels, first on the level of its overarching narrative, and second, on the level of the different segments within that larger narrative. On the level of the overarching narrative, the documentary uses wayang to tell and structure its story. Wayang is classical Javanese puppet theater. Like a wayang narrative, the documentary narrative consists of different segments. Every segment in the documentary is introduced through displaying wayang puppets. In these introductions, the documentary uses puppets from the Mahabharata, a Sanskrit epic of ancient India. The core story of the Mahabharata is a war story, a dynastic struggle between two families (the Kaurava and the Pandava) for the throne of the kingdom. The Mahabharata characters themselves symbolize the battle between the opposites of good and evil, and between Godly and demon-like behavior. In its introductions, Rahmat Islam Nusantara consistently links good and evil Mahabharata wayang characters to different interpretations of Islam. The power-hungry Duryodhana is for instance linked to Wahhabi Islam, whereas the Pandavas are linked to Islam Nusantara. By basing its main narrative structure on the Mahabharata wayang story, a story of good and evil, Rahmat Islam Nusantara makes this binary opposition central to the very way it is telling its story. The documentary thereby sets up a dramatic and schematic framing of local Islam Nusantara and foreign (Wahhabi) Islam, even before explaining what these entail.

This binary opposition is also constructed on the level of the individual segments. In what follows, I suggest that Rahmat Islam Nusantara constructs two discourses. First, a discourse is constructed in which ‘foreign’ Islam is seen as a colonizing force, which threatens ‘local’ cultures, while Islam Nusantara adapts to ‘local’ cultures. This discourse frames Islam Nusantara’s alleged adaptability as a key to challenging what the documentary sees as ‘radical’ Islam, and ultimately holds ulama responsible for further adapting Islam to contemporary times.

This discourse is specifically constructed when Rahmat Islam Nusantara discusses the (early) spread of Islam, and when it discusses how Muslims should approach formal worship. When comparing the spread of Islam in the Arab Middle East and in Indonesia, Islam Nusantara is constructed as a naturally tolerant form of Islam. Significantly, the scene that explains the spread of Islam begins with a shot of a sign that reads ‘Selamat Datang’ (welcome) – suggesting that Indonesia is open and welcoming. Subsequently, we see Yahya Cholil Staquf, a kyai, talking about the arrival of Islam in Indonesia. He explains:

The arrival of Islam did not evoke resistance among the inhabitants of the East Indies Archipelago, because the Nusantara civilization was already long accustomed to foreign cultures and religions. When something new arrived from afar, people would study it – adopting what they liked […]. Muslim proselytizers could relax and engage in dialogue with the reality of Nusantara society.Footnote3

I say this by way of comparing Islam Nusantara with the Islamic civilization that emerged in the Arab Middle East and its various offspring […] Military conquest invariably preceded the introduction of Islam itself. […] Islam burst forth as a military and political overlord and it was precisely in the name of Islam that Arab tribes justified their rule.

Subsequently, the documentary uses these two different kinds of histories to further set the practices of Islam Nusantara apart from practices of ‘foreign’ Islam. This becomes apparent when the documentary discusses how the Walisongo introduced Islam to Indonesia. This is discussed by Mustofa Bisri, who appears often in the film. Bisri, commonly known as Gus Mus, is a famous kyai, and the head of Pondok Pesantren Raudlatuth Thalibin, an Islamic school in Rembang, Central Java. He is a prominent NU member and was asked by former Indonesian president Wahid (1999–2001) to run for NU chairman, which he declined. Gus Mus discusses the arrival of Islam in Indonesia as follows:

The Walisongo […] dove right into the midst of society and [embraced] local cultures and infused them with even greater wisdom. […] [They] conveyed the essence of Islamic teachings, never thinking that religion should be confined to the rules of Islamic law or formal worship while abandoning moral and ethical integrity.

What justifies their [ISIS’] behavior? According to the rules of fiqh [Islamic jurisprudence], their imam has the right to choose: he may execute, he may ransom, he may enslave prisoners. This provision exists within fiqh. […] we may implement this provision and butcher people, according to the rules of fiqh that still exist today. This is a problem.

NU authorized the development of new systems of thought, just as the classical ulama developed their own methodologies in accord with the conditions […] of their times. […] Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi, the ISIS caliph, suddenly proclaimed that: ‘as caliph and imam, I’m restoring the classical Islamic laws that govern slavery’. […] They now enslave women […]. The rationale for Baghdadi’s actions still exists within our own fiqh. This is a heavy responsibility for NU ulama. What exactly does it mean that we need to rethink fiqh within the context of our contemporary world?

In the following, I suggest that another discourse is constructed in Rahmat Islam Nusantara. Central to this discourse is a binary opposition between destruction and preservation of Islamic heritage. The documentary constructs Wahhabi Islam as a destructive force, while it constructs Islam Nusantara as respectful. I also propose that the documentary makes Muslims responsible for protecting a peaceful practice of Islam.

When introducing Islam Nusantara and ‘foreign’ Islam, Rahmat Islam Nusantara shows the wayang character King Whelgeduwelbeh and his Vizier. Below the wayang character, a text appears that states that these figures ‘symbolize that confused thought leads to destructive behavior that violates religious teachings and rips apart the fabric of a humane social order’. In the subsequent scene, it becomes clear that ‘confused thought’ here refers to Wahhabi Islam. The scene shows NU ulama Habib Luthfi bin Yahya. Habib Luthfi, as he is commonly known, is the chairman of MUI (Indonesia’s top Muslim clerical body) Central Java, the national chairman of the Association of Recognized Sufi Orders, and a prominent and respected figure within NU. He was even listed among the top 50 in the 2017 publication of The 500 Most Influential Muslims, a report published by The Royal Islamic Strategic Studies Centre in Jordan which ranks the most influential Muslims in the world. In this scene, he says:

I cannot lie about the profound concern I feel when historical sites associated with our beloved Prophet […] historical sites where he himself walked and lived, as did his companions, have nearly vanished from the face of the earth. The question arises: what authentic data will future generations of Muslims have about Islam’s early history […]?

These scenes differ strongly from the documentary’s portrayals of contemporary Islam Nusantara practices. One practice that is particularly singled out is ziarah. Ziarah is popular among NU followers and refers to the practice of visiting graves and tombs of important people, whether religious/political figures or family members. It is believed that a visit to a grave puts the visitor in a relationship with the power of the deceased, which lingers there (Fox Citation2002, 165). Rahmat Islam Nusantara particularly zooms in on visits to tombs of the Walisongo saints.

The documentary shows a keeper of a shrine, who explains that Walisongo shrines are visited by thousands every day. We see shots of the shrines being maintained by professionals, shots of people putting flowers on the graves, and shots of people kissing the sites. Islam Nusantara and its followers are thus framed as utterly respectful to religious heritage, which stands in strong contrast with the Wahhabi destruction of religious sites. Although it is impossible to make claims about the intentions of the makers or about the ‘effects’ that this kind of editing may have without conducting a solid production or audience analysis, the sharp contrast between utter destruction and utter respect for holy sites seems to appeal to emotions.

The documentary creates a binary between ‘foreign’, ‘bad’ Islam and a ‘good’, ‘local’ Islam Nusantara, it constructs Islam Nusantara’s saints, the Walisongo as the ultimate role models for ‘good Muslims’. As Gus Mus says:

Saints are consistent in their virtuous behavior […] Through saints we may approach God, by loving the saints, and adopting them as our role models and only then engaging in the struggle (jihad) on God’s path (guided by their example), so that we may attain a state of true happiness.

What is most conspicuous about the teachings we’ve inherited from the saints is their great wisdom regarding ‘the development of the soul’. […] Saints have achieved a remarkable degree of self-knowledge, or intrapersonal intelligence.

People were taught, first and foremost, to be fully human, and thus humane. This differs from most contemporary da’wa, which encourages people to embrace religion before they’ve become fully human. When inhumane people practice religion, they bring their personal defects to the practice of religion itself.

Rahmat Islam Nusantara thus creates a binary opposition between ‘local’ Indonesian Islam and ‘foreign’ Wahhabi Islam and between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslims. While doing so, the film visualizes and implicitly constructs and legitimizes the chain of religious authority. The documentary first shows references to the Prophet and his family, then to the Walisongo, and subsequently to contemporary Indonesian ulama. And since the Walisongo are constructed as role models for people, it is here not just ulama who are held responsible for the practice of peaceful Islam, but also Muslims themselves. They are encouraged by ulama to adopt the Walisongo as their role models, learn from their teachings, and work on themselves to improve their self-knowledge as the documentary suggests that self-discipline makes one a ‘good Muslim’ and prevents violence. Rahmat Islam Nusantara however does not elaborate on how to exactly work on oneself. I suggest that the cyber warrior initiative does do so by advising followers to work on themselves.

Cyberwarriors: Islam Nusantara Kyai and Ulama as role models

In a bid to counter ‘radicalism’ online, cyber warrior volunteers are being trained by NU (Varagur Citation2016). Volunteers are taught photo and video-editing skills, and are taught how to optimize posts for social media (Schmidt Citation2018a, 34). Cyber warriors are free to create their own images – in terms of what they show. They mostly share their content on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, where they have between 100.000 and 750.000 followers. Most cyber warrior accounts publicly state their NU affiliation on their profile, while others do not claim any formal affiliation, but their content often explicitly promotes NU and Islam. Compared to the documentary, NU thus has less control over the counternarrative that is constructed.

In the following analysis, I explore the three most active (most posts and responses per day) and most followed cyberwarrior social media accounts: IslamRahmah (@ikwanrembang – 416.000 followers)Footnote4, AlaNU (@ala_nu – 701.000 followers)Footnote5, and CYBER Ansor Media (@ansor_jatim – 214.000 followers).Footnote6 These accounts are mostly popular among teenage Indonesian Muslims. The accounts state in their profile description that they are members of the ‘Cyber Troop’ network, the network of cyberwarriors. Over a five-month period (1 September 2016–1 March 2017), data were collected from these three accounts, for a total of 1814 posts.Footnote7 More than half (1309 posts) of all the posts (1814) on cyberwarrior accounts consists of memes and (digitally altered) images of Islam Nusantara kyai and ulama. Therefore, I focus on these posts. Elsewhere (Schmidt Citation2018a), I have shown how the cyber warrior initiative constructs kyai and ulama as stars and how such posts give way to a governmental politics. Here, I focus on these posts to analyze how counternarratives are constructed and how the binary between ‘good’ ‘moderate’ and ‘bad’ ‘radical’ Muslims identified in Rahmat Islam Nusantara is also produced on the selected cyber warrior accounts. I argue that through images of Islam Nusantara kyai and ulama, cyberwarriors construct a counternarrative that is marked by an aesthetics of authority. In this counternarrative, a chain of religious authority is created and legitimized. The place of the kyai/ulama in this chain frames them as authoritative role models whose legacy shields the country from ‘radicalism’, while people are encouraged to model their behavior after these figures, to be(come) ‘good’ or better Muslims, who help to protect the nation from ‘bad’ Muslims. While doing so, the cyber warrior initiative defines what kinds of behavior makes someone a ‘good’ Muslim. The aesthetics of authority is here underpinned by three types of tropes: (1) threat, (2) exceptional authority, and (3) inspiration.

Threat

The ground for construction of Islam Nusantara kyai/ulama as role models through an aesthetics of authority is laid through the trope of ‘threat’. This trope recurs on the accounts and points out who are considered to be ‘bad’ Muslims while constructing the idea that Indonesia is under threat and finds itself in a state of danger.

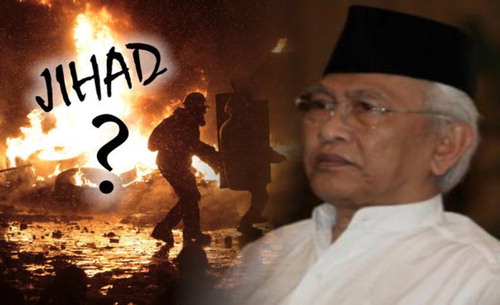

Two presumed threats are specifically singled out on the accounts of cyberwarriors: interreligious tensions and ISIS. provides an example of a post that helps construct the idea that ISIS presents a threat to Indonesia. The post shows Gus Mus, whose portrait is digitally superimposed on an image that shows burning wreckage while police officers hold up a protective shield. The word jihad is added in black. The accompanying text added by the account moderator reads (@ikhwanrembang, 16 January 2017):

The danger of ISIS … Did you know that ISIS is moving into Indonesia and the Philippines? Lately, more young Indonesians feel attracted to the form of jihad that is promoted by them. […] Keep looking around carefully; if you see anyone flirting with these ideas, you need to discuss it with them. You can protect Indonesia from such terror and suffering.

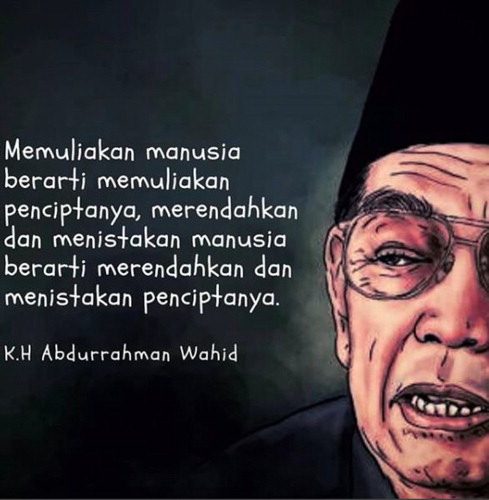

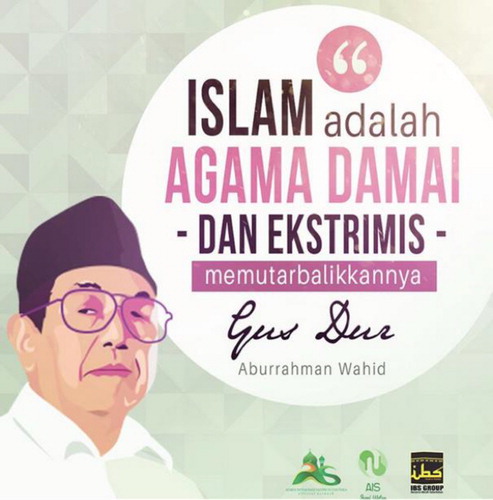

addresses interreligious tensions as a threat to a peaceful public order. These kinds of posts are often shared on cyber warrior accounts. depicts a drawing of Abdurrahman Wahid (commonly known as Gus DurFootnote8). Gus Dur, who passed away in 2009, served as Indonesian president from 1999–2001, was a kyai, and a vocal supporter of Islam Nusantara. Gus Dur’s ancestors helped to found NU, and Gus Dur himself served three terms as NU chairman. In 1999, he was the first Indonesian president to be elected through a people’s vote. The following text, a quote by Gus Dur, is added to the drawing: ‘Glorifying humanity means glorifying its creator. Dehumanizing and humiliating humanity means degrading its creator’. (@ikhwanrembang, 6 November 2016) The text that the moderator has added reads: ‘Radical Islam is degrading fellow Indonesians, honest Christians with whom we share this beautiful country. It would have made Gus so sad to see Indonesia in this state’ (@ikhwanrembang, 6 November 2016). The drawing was posted on 5 November and can be seen as referring to the Ahok demonstrationsFootnote9 in Jakarta a day earlier, which in public discourse were understood as a dispute between Chinese/Christians and Muslims.

Posts such as thus suggest that Indonesia is under threat from several forces, most notably interreligious tensions and foreign ‘radicalism’. ISIS (in ) and Ahok demonstrators (in ) are collapsed into one category and are here particularly constructed as ‘bad’ Muslims. The trope of threat identified in these posts legitimizes the existence of the cyber warrior accounts and makes way for the trope of ‘exceptional authority’, which construct Islam Nusantara kyai/ulama as the only true sources of religious authority in dangerous times and as ‘good’ Muslims, ‘saviors’ of a divided Indonesia under threat.

Exceptional authority

The notion that Islam Nusantara kyai/ulama are the only true sources of Islamic authority is on the accounts constructed through the image of them having died. On the accounts of cyber warriors, the trope of ‘exceptional authority’ often constructs Islam Nusantara ulama as possessing a unique talent. I propose that such images show key aspects of the aesthetics of authority and show how the idea of kyai/ulama as the only true religious sources of Islamic authority is produced on the social media accounts of cyber warriors.

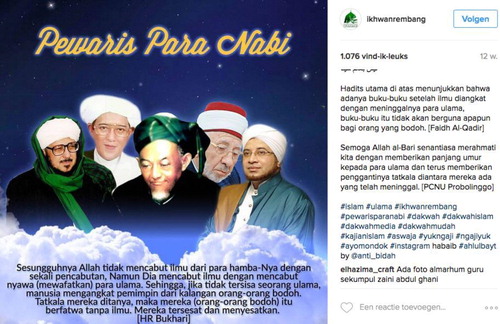

shows the workings of an aesthetic of authority. It shows how written text and visual elements work together to construct a chain of religious authority in which ulama become (like in Rahmat Islam Nusantara) ‘inheritors’ of Allah’s and the Prophet’s knowledge. While in Rahmat Islam Nusantara the Walisongo formed the link in the chain between the Prophet and the ulama, here the ulama are constructed as the direct inheritors of such wisdom. shows a digitally altered picture in which five ulama who have died, are placed on a cloud that is drifting in a starry universe. This visual construction underlines that the ulama are no longer among us and suggests that they are in paradise. The deceased ulama in the picture are all well-known ulama in Indonesia: from left to right, As-Sayyid Muhammad bin Alawi Al-Maliki (1946–2003), Muhammad Zaini Abdul Ghani (1942–2005), Hasyim Asy’ari (1875–1947), Muhammad Said Ramadhan al-Buthi (1929–2013), and Munzir Al-Musawa (1973–2013). Above their heads, the words ‘Inheritors of the Prophet’ are written, and below a quotation from the hadith interpreted by Imam Bukhari (a well-known hadith expert)Footnote10 is added, which reads (@ikhwanrembang, 31 October 2016):

Allah does not leave his followers without ilmu [an all-embracing term covering Islamic theory, action, and education], but calls upon ulama to convey His knowledge. Thus if there are no longer ulama left, people will find their leader among the dumb people. They will be led without ilmu, will get lost and will be misled. HR Bukhari.

The death of ulama is a big disaster, because along with their departure, knowledge [ilmu] disappears from the earth. Without it, mankind will behave like animals. The stack of books will no longer bring us any benefit, because books cannot replace the function of the clergy. […] May Allah always bless us to give long life to ulama and give us a successor when they pass away.

Inspiration

The trope of exceptional authority thus constructs kyai/ulama as the true sources of religious authority – thereby making them into figures to admire. How is this construction a counternarrative? I suggest that cyberwarriors try to encourage people to model themselves after the kyai/ulama and be(come) ‘good’ ‘moderate’ Muslims, who can counter ‘bad’ ‘radical’ Muslims. A recurring trope of ‘inspiration’ is identified in posts of cyberwarriors. This trope works in a threefold way. First, posts ascribe assumed personality traits to kyai/ulama. Second, by doing so, they make them agents of tolerance, diversity, and moderation – aspects for which Islam Nusantara is often praised. Posts do so in a way that responds to the problems – ‘radicalism’ and interreligious tensions – that were constructed by the trope of threat. Third, posts encourage users to model themselves after Islam Nusantara kyai/ulama by offering followers advice on how to behave and be(come) ‘good’ or ‘better’ Muslims, who are self-confident, tolerant, open-minded, and who learn from interactions with fellow Indonesians.

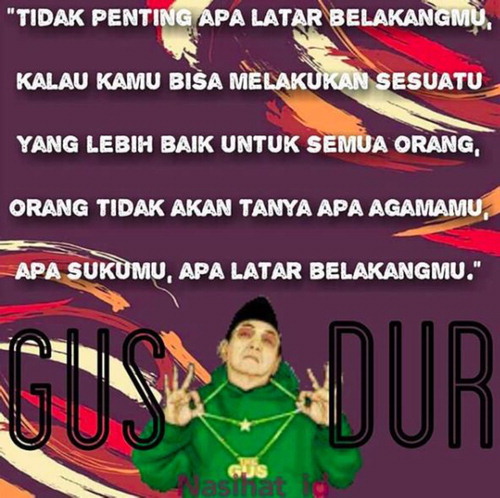

provide examples. The post in shows Gus Dur as a ‘cool guy’, wearing gold chains, of which one states that he is ‘THE GUS’. He is recognizably dressed as an Indonesian Muslim, wearing a green – the color of Islam – hoodie and a peci, a Muslim cap, which in Indonesia also has secular nationalist connotations. The text in the image is a quote by Gus Dur and reads: ‘It doesn't matter what your background is, if you can do something good for other people, people will not ask what your religion is, what your ethnicity is, what your background is’ (@ikhwanrembang, 27 November 2016). The caption that accompanies this image reads (@ikhwanrembang, 27 November 2016):

In this moment, when different groups in society seem to clash, we need to remember what Gus once said: ‘Pluralism must be accepted without differences’. Gus embraced people of other religions. He stressed that religion, ethnicity, and class do not matter. We can carry on in Gus’ spirit. Invite people of other backgrounds and religions into your house, share a meal, get to know them, offer a helping hand. Your life will be better for it.

In addition to tolerance, ‘religious moderation’ becomes part of Gus Dur’s online representation. Here, ‘religious moderation’ – although it remains unclear what moderation entails – is specifically framed as a solution to ‘extremist’ Islam and is thus not only constructed as ‘good’ Islam, but also as a practice is imagined to counter ‘radical’ Islam. , posted on Facebook, also shows Gus Dur, this time with a quotation that reads: ‘Islam is a peaceful religion, and extremists twist it’. The post is accompanied by the following text, in which, followers are encouraged to counter ‘radical’ thought themselves (@ikhwan_rembang, 22 December 2016):

Gus had a moderate interpretation of Islam, he knew that it is peace, good Islam is love. Be on the right side here. Let a correct interpretation of Islam fight radical thought, and let it oppose the violence we have seen in the past year [referring the Ahok demonstrations]. Correct others if they have wrong ideas, they could ruin our religion.

, posted on Facebook, uses a similar tactic. The image shows Islam Nusantara ulama Habib Luthfi with his fist in the air. The aesthetics portray him as a strong, powerful, and confident figure: because of the low-angle perspective, one looks up to him, and he literally shines bright. In the top-right corner is the logo of Banser (Barisan Ansor Serbaguna Nahdlatul Ulama), the autonomous NU body that is engaged in humanitarian and security missions across the archipelago. The accompanying text reads (@ikhwan_ rembang, 29 October 2016):

Do not be proud if you are part of those who call for jihad. [T]ake advice from Habib Luthfi bin Yahya, who said: ‘If the jihad is being led by a sense of revenge, it is not Jihad li i'la'i kalimatillah [elevate the word of Allah], but nothing more than just hate. He knows the difference. Make sure you know what you are talking about […] ask a respected teacher, so that you can be confident in your convictions too. When you feel angry, never engage in hate, make yourself useful, for instance by keeping the country safe.

Through memes and other digitally altered images of Islam Nusantara kyai and ulama, cyberwarriors create a counternarrative to Islamic ‘radicalism’. This counternarrative favors Islam Nusantara and promotes what its adherents often call its key characteristics – tolerance, diversity, moderation, although it never becomes clear what moderation exactly entails. The counternarrative that is constructed imagines ‘good’ Muslims as self-confident, tolerant – another term that is not further clarified – open-minded and social people, who are themselves seen as responsible for countering ‘bad’ ‘radical’ Muslims.

Discussion

The two NU initiatives, Rahmat Islam Nusantara and the cyberwarriors, are marked by an aesthetics of authority, which constructs and legitimizes a specific chain of religious authority. This forms the basis for the construction of counternarratives in which Walisongo saints, kyai, and ulama are constructed as inspirational role models, to which one needs to listen in troubling times, and who become an antidote to extremist thought. People are encouraged to model themselves after the saints, kyai and ulama to counter the assumed threats of ‘radicalism’.

Narratives, in being human (re)constructions of the world, are never neutral, but are always ideologically charged. The counternarratives constructed here too show specific subjective (re)constructions of the world, represent specific practices as ‘good’ or ‘bad’, and define who has (or should have) religious authority, and who is responsible for countering ‘radicalism’.

The counternarratives constructed here take a stance on the issue of religious authority. In the context of the earlier-discussed fragmentation of religious authority, the counternarratives (re)claim religious authority and restore the saints, kyai, and ulama as the most important sources of knowledge. The initiatives also hold kyai, and ulama responsible for what they see as the necessary practice of adapting Islam to a contemporary world. In the case of the cyber warriors, social media also allows for corrosion of religious authority. The cyber warrior accounts are not managed by kyai and ulama, but instead by volunteers who cut and paste (assumed) quotations of kyai and ulama, capture their ideas in short messages. Religious authority can in this way be corroded (Schmidt Citation2018a, 63).

While reflecting on religious authority, the counternarratives create an opposition between different interpretations of Islam, which they frame as ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Islam, and which are practiced by ‘good’ and ‘bad’ Muslims. They uphold a binary between ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ Islam as they frame ‘foreign’ Islam as ‘bad radical Islam’, and Islam Nusantara as ‘good moderate Islam’ – without detailing what ‘moderation’ entails. Posts by cyberwarriors encourage people to adopt Islam Nusantara’s constructed values – such as tolerance and open-mindedness – and be(come) ‘good’ ‘moderate’ Muslims who help counter ‘bad’ ‘radical’ Islam. An imagined shared religious identity grounded in Islam Nusantara support here thus becomes the basis on which Muslim citizens are collectively held responsible for protecting a peaceful practice of Islam. In this sense, the initiatives articulate the global war on terror discourse that has played a role in defining ‘moderate’ Islam in Indonesia. But we can also understand the upholding of a ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ binary from a local context, and should see it in the context of the challenges that the current Islamic landscape in the archipelago and recent developments in Indonesian Islam are posing to NU. The fall of the Suharto regime and its restrictions on freedom of expression have led to the emergence of new Islamic organizations that challenge both NU and Muhammadiyah. Simultaneously internal divisions have in recent years emerged within NU. These internal divisions have meant that Indonesia’s largest Muslim organizations present at times conflicting or unclear positions on issues such as the rights of followers of local or traditional faiths, LGBTQ Indonesians, and the rights of minorities within Islam (Syarif Citation2019).

Disagreement is part of managing large, democratic organizations. ‘NU […] however achieved [its] status and influence through efficient internal consolidation and by presenting a coherent narrative to the public’ (Syarif Citation2019). Here the constructed counternarratives and the binary between ‘moderate’ and ‘radical’ Islam serve different interests. First, the social media promotion of Islam Nusantara helps to communicate a clear coherent narrative to the public about what NU stands for today. Second, the promotion of ‘moderate’ Islam Nusantara not only helps NU to set itself apart from (‘new’) competing (Islamist) organizations, but it also (implicitly) associates these organizations with terrorism and (the foreign threat of) ISIS. Associating these organizations with terrorism and the foreign threat of Islamic radicalism (such as ISIS) consolidates ‘moderate’ Islam Nusantara as having a long-standing tradition of ‘safeguarding’ Indonesia’s independence and stable democracy – both locally and internationally – against alleged threats of Islamic ‘radicalism’.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Leonie Schmidt

Leonie Schmidt is Associate Professor in Media Studies in the Media Studies Department at the University of Amsterdam. She is the author of Islamic Modernities in Southeast Asia: Exploring Indonesian Popular and Visual Culture (Rowman & Littlefield, 2018).

Notes

1 English title: The Divine Grace of East Indies Islam, produced by NU, al-Ma’had al-Dawali lil’ Dirasaat al-Qur’aniyya, Majima Buhuts an-Nahdliyyah, Perhimpunan Pemangku Makam Auliya’, and Gerakan Pemuda Ansor NU.

2 The terms santri and abangan are useful to identify fractions of the Muslim population in Java […]. Santri, originally the students in religious schools (pesantren), now encompasses the wider category of the pious Muslims, whereas abangan refers to nominal Muslims’ (Ali Citation2007, 33).

3 The quotes in this article follow the English subtitles.

4 See https://www.instagram.com/ikhwanrembang/ and https://www.facebook.com/ikhwanrbg/ (accessed 1 August 2018).

5 See https://www.instagram.com/ala_nu/ (accessed 1 August 2018).

6 See https://twitter.com/ansor_jatim?lang=nl/ (accessed 2 August 2018).

7 Data was collected using the Instagram Hashtag Explorer, Twitter Capture, and Netvizz tools.

8 The nickname Gus Dur is derived from ‘Gus’, a common honorific for a son of kyai, and from short-form of bagus (meaning both ‘good’ in Bahasa Indonesia and 'handsome lad' in Javanese).

9 In October and November 2016 an estimated 50.000–200.000 people took to the streets of Jakarta to protest against the then governor of the capital Basuki ‘Ahok’ Tjahaja Purnama. The protesters accused the Chinese Christian governor of blasphemy and demanded his imprisonment. The November protest descended into violence as night fell with demonstrators hurling missiles at security forces, who responded with tear gas and water cannons.

10 Hadith are reports describing the life and actions of the Prophet.

References

- Alford, Peter. 2015. “Nahdlatul Ulama: Indonesia’s Antidote to Islamism’s Feral Fringe.” The Australian, December 11. https://www.theaustralian.com.au/news/world/nahdlatul-ulama-indonesias-antidote-to-islamisms-feral-fringe/newsstory/f6f2bba635a1883a0e38d0d6c0d961c8.

- Ali, Muhamad. 2007. “Categorizing Muslims in Postcolonial Indonesia.” Moussons. Recherche en Sciences Humaines sur L’Asie du Sud-Est 11: 33–62.

- Archetti, Cristina. 2013. “Narrative Wars: Understanding Terrorism in the Era of Global Interconnectedness.” In Forging the World: Strategic Narratives and International Relations, edited by Alistair Miskimmon, Ben O’Loughlin, and Laura Roselle, 218–245. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Arifianto, Alexander Raymond. 2016. “Islam Nusantara: NU’s Bid to Promote ‘Moderate Indonesian Islam’.” RSIS Commentary, May 17. https://www.rsis.edu.sg/rsis-publication/rsis/co16114-islam-nusantara-nus-bid-to-promote-moderate-indonesian-islam/#.XAUZgieNyu5.

- Bignell, Jonathan. 2004. An Introduction to Television Studies. London and New York: Routledge.

- Burhanudin, Jajat. 2014. “The Dutch Colonial Policy on Islam: Reading the Intellectual Journey of Snouck Hurgronje.” Al-Jāmi‘ah: Journal of Islamic Studies 52: 25–58.

- Cochrane, Joe. 2015. “From Indonesia, a Muslim Challenge to the Ideology of The Islamic State.” The New York Times, November 25. https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/27/world/asia/indonesia-islam-nahdlatul-ulama.html.

- Fealy, Greg. 2018. “Nahdlatul Ulama and the Politics Trap.” ANU, July 18. http://asiapacific.anu.edu.au/news-events/all-stories/nahdlatul-ulama-and-politics-trap.

- Fox, James. 2002. “Interpreting the Historical Significance of Tombs and Chronicles in Contemporary Java.” In The Potent Dead: Ancestors, Saints and Heroes in Contemporary Indonesia, edited by Henri Chambert-Loir, and Anthony Reid, 103–116. Honolulu: University of Hawaìi Press.

- Grossman, Michele. 2014. “Disenchantments: Counterterror Narratives and Conviviality.” Critical Studies on Terrorism 7 (3): 319–335.

- Hall, Stuart. 1997. Representation: Cultural Representation and Signifying Practices. London: The Open University and Sage Publications.

- Hilmy, Masdar. 2013. “Whither Indonesia’s Islamic Moderatism? A Reexamination on the Moderate Vision of Muhammadiyah and NU.” Journal of Indonesian Islam 7: 24–48.

- Hoesterey, James B. 2007. “The Rise, Fall, and Re-Branding of a Celebrity Preacher.” Inside Indonesia, 90 (Oct.-Dec.). http://www.insideindonesia.org/weekly-articles-90-oct-dec-2007/aa-gym-02121580/.

- Hoesterey, James B. 2012. “Prophetic Cosmopolitanism: Islam, Pop Psychology, and Civic Virtue in Indonesia.” City & Society 24: 38–61.

- Hoesterey, James B. 2020. “Islamic Soft Power in the Age of Trump: Public Diplomacy and Indonesian Mosque Communities in America.” Islam and Christian-Muslim Relations 31: 191–214.

- Huda, Ahmad Nuril. 2012. “Negotiating Islam with Cinema: A Theoretical Discussion on Indonesian Islamic Films.” Wacana 14: 1–16.

- Juniarto, Damar. 2018. “The Muslim Cyber Army: What Is It and What does it Want?” Indonesia at Melbourne, March 10. http://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/the-muslim-cyber-army-what-is-it-and-what-does-it-want/.

- Kaptein, Nico J. 2004. “The Voice of the Ulamâ: Fatwas and Religious Authority in Indonesia.” Archives de Sciences Sociales des Religions 125: 115–130.

- Kruithof, Maryse. 2014. “Shouting in a Desert. Dutch Missionary Encounters with Javanese Islam, 1850-1910.” PhD diss., Erasmus University Rotterdam.

- Mamdani, Mahmood. 2002. “Good Muslim, Bad Muslim: A Political Perspective on Culture and Terrorism.” American anthropologist 104 (3): 766–775.

- Nemr, Christina. 2016. “Strategies to Counter-Terrorist Narratives Are More Confused Than Ever.” War on the Rocks, March 15. http://warontherocks.com/2016/03/strategies-to-counter-terrorist-narratives-are-more-confused-than-ever/.

- Nye, Joseph S. 1990. “Soft Power.” Foreign Policy 80: 153–171.

- Schmidt, Leonie. 2018a. “Cyber Warriors and Counter-Stars: Contesting Religious Radicalism and Violence on Indonesian Social Media.” Asiascape: Digital Asia 5: 32–67.

- Schmidt, Leonie. 2018b. Islamic Modernities in Southeast Asia: Exploring Indonesian Popular and Visual Culture. London: Rowman & Littlefield.

- Siswo, Sujadi. 2015. “Indonesia’s Largest Muslim Group Joins Battle Against Radical Islam.” Channel NewsAsia, December 10. https://www.libforall.org/lfa/media/2015/channelnewsasia_Indonesias-largest-Muslim-group-joins-battle-against-radical-Islam_12-10-15.pdf.

- Syarif, Ahmad. 2019. “The politics of fighting intolerance”. Indonesia at Melbourne, March 12. https://indonesiaatmelbourne.unimelb.edu.au/the-politics-of-fighting-intolerance/.

- Tuck, Henry, and Tanya Silverman. 2016. The Counter-Narrative Handbook. London: Institute for Strategic Dialogue.

- Turner, Bryan S. 2007. “Religious Authority and the New Media.” Theory, Culture & Society 24 (2): 117–134.

- Umar, Ahmad Rizky Mardhatillah. 2016. “A Genealogy of Moderate Islam: Governmentality and Discourses of Islam in Indonesia’s Foreign Policy.” Studia Islamika 23 (3): 399–433.

- Vande Berg, Leah, et al. 2004. Critical Approaches to Television. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company.

- Varagur, Krithika. 2015. “World’s Largest Islamic Organization Tells Isis to Get Lost.” The Huffington Post, December 2. https://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/indonesian-muslims-counter-isis_us_565c737ae4b072e9d1c26bda?guccounter=1.

- Varagur, Krithika. 2016. “Indonesia’s Cyber Warriors Battle ISIS with Memes, Tweets, and Whatsapp.” The Huffington Post, September 6. http://www.huffingtonpost.com/entry/Indonesia isiscyberwarriors_us_57507 79ae4b0eb20fa0d2684/.

- Weintraub, Andrew. 2011. Islam and Popular Culture in Indonesia and Malaysia. London & New York: Routledge.