ABSTRACT

The article explores the cybernetic utopian ideals of transhumanism and posthumanism, focusing particularly on the concept of the singularity, which incorporates both scientific and religious dimensions. This investigation subsequently leads to an in-depth examination of temporal concepts within the broader discourse surrounding the disenchantment thesis in secular modernity. Drawing on the framework of multiple temporalities proposed by Lorenz Trein and Helge Jordheim, the article suggests a perspective that enables an understanding of diverse interpretations of history and the future as a dynamic interplay that transcends the binary opposition between (secular) science and religion.

Introduction

Every technological innovation invites a thorough examination of its practical implications. This involves a careful evaluation of the advantages and disadvantages of its applications in conjunction with associated costs. Concurrently, a societal and cultural discourse unfolds, delving into the merits, impacts, and prospects of the new technology. This is particularly the case when it comes to the relationship between humans and computers. In the context of posthumanism and transhumanism, digital media emerges as a pivotal component of a comprehensive utopian vision encompassing all life on Earth. Transhumanists envision the boundless augmentation of human capabilities through cybertechnologies, while posthumanists foresee computers offering a pathway to digital immortality. Anticipation of a future artificial intelligence (AI) resolving all of humanity’s challenges – and even those of the entire universe, upon realizing the singularity – is also prevalent. However, it is essential to recognize that this current of technophilia did not emerge in a cultural vacuum; rather, it originated within the specific framework of American progress philosophy and its distinctive interpretation of European Enlightenment ideals.

Although posthumanists and transhumanists explicitly identify as materialist thinkers and often adopt a critical stance towards religion, Christian ideas, motifs, and historical concepts are discernible in their cybernetic utopian ideologies. These religious references manifest primarily on two levels: firstly, in the depictions of an immortal existence characterized by omnipotence and omniscience, and secondly, in their teleological interpretation of history. While the former aspect may appear somewhat banal in certain respects (Krüger Citation2021, 263–276), the historical dimension offers an avenue for connecting the discourse on transhumanism and posthumanism to broader sociological inquiries concerning religion, science, secularism, and the concept of disenchantment.

Following a concise introduction to the realms of posthumanism and transhumanism, I delve into the core temporal concept held by posthumanists, namely the singularity, and situate it in its historical context. Against this background, I explore the various narratives that characterize the relationship between religion and science, which can range from entanglement to opposition, and draw relations between these narratives and the broader discourse surrounding disenchantment in secular modernity. This approach aligns with recent trends in the study of religion that emphasize relational perspectives, as articulated in works such as those by Krech (Citation2020), Krüger (Citation2022), and Rota (in this special issue). To conclude, I introduce the concept of multiple temporalities. The period that I am examining already encompasses half a century, starting with the cryonic and early transhumanist visions of the 1960s. With this in mind, I understand the history of posthumanist utopias as a history of ideas, or more precisely: a history of the future (Hölscher Citation2018).

Posthumanism and transhumanism

Among the diverse range of thinkers advocating the overcoming of humanity with the help of new technologies, many are often called transhumanists. Yet despite this increasingly frequent usage, there is a need to differentiate between technological posthumanism and transhumanism. Not only does the term posthumanism, which is commonly used in art and cultural studies research, itself need to be clarified, but noticeable differences can in fact be found between the purposes, contents, and origins of transhumanism and those of technological posthumanism.Footnote1

Transhumanism primarily originated in California during the 1960s and was decisively influenced by the futurist Fereidoun M. Esfandiary (a.k.a. FM-2030); Timothy Leary, the pioneer of the psychedelic movement; and the cryonics expert Robert Ettinger (for the parallels with the psychedelic movement, see Rota in this special issue). In the late 1980s, this movement gave rise to the Extropians around Max More and, as European involvement increased, the World Transhumanist Association founded by Nick Bostrom, David Pearce, James Hughes, Anders Sandberg, and others in 1998.

Technological posthumanism, on the other hand, unites a number of authors who have been propagating the total replacement of humans by artificial intelligences since the mid-1980s. Its four main proponents – Hans Moravec, Frank Tipler, Marvin Minsky, and Ray Kurzweil – argue on the basis of cybernetic theory. Before the early 2000s, these authors did not refer to the transhumanist movement and its themes in any way.

The second argument for distinguishing between posthumanism and transhumanism centers on their divergent emphases in terms of content. The concept of transhumanism encompasses an array of highly varied ideas and practices. Transhumanists engage directly with practical concerns related to extending human life and enhancing mental and physical capabilities. This can involve endeavors such as the use of smart drugs, adopting life-extending diets, pursuing bodybuilding regimens, advancements in prosthetic technology, the exploration of potential forms of eugenics, and even the prospects of cryonics. Conversely, these specific applications are infrequently discussed in posthumanist literature. In transhumanism, the focus revolves around the development of humankind and the potential transformations of human beings through technological upgrades and enhancements. By contrast, within the framework of posthumanism, the agents of future evolution and progress are envisioned as robots, computers, and artificial intelligences.

The roboticist Hans Moravec (born 1948) was the first author to share this vision of a postbiological and supernatural future for humankind in his work Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence (Citation1988). As a student he already published a first draft of these ideas in a science fiction magazine (Moravec Citation1979). The preface of his seminal book reads like a preamble to posthumanism:

Engaged for billions of years in a relentless, spiraling arms race with one another, our genes have finally outsmarted themselves […] What awaits us is not oblivion but rather a future which, from our present vantage point, is best described by the words ‘postbiological’ or even ‘supernatural’. (Moravec Citation1988, 1)

The IT entrepreneur Ray Kurzweil (born 1948), the most prominent posthumanist alive today, follows Moravec’s path to the future but introduces more concrete detail and radical perspectives. According to his early book The Age of Spiritual Machines (Citation1999), humans and machines will have merged by the year 2099, and humankind will have overcome its biological condition (Citation1999, 277–280). In his more recent work, The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology (Citation2005), the prospect of salvation history is accelerated by half a century to the year 2045, when he considers the singularity will have been materialized and all of humanity’s problems will be solved.

The position of physicist Frank J. Tipler (born 1947) differs from that of other posthumanists in many regards – whether in terms of his emphasis on cosmology, his euphoric images of virtual paradise, or his scientific inclusivism, which does not seek to overcome religion but rather to integrate it into physics. He became famous for his 1994 book The Physics of Immortality: Modern Cosmology, God and the Resurrection of the Dead. According to Tipler, when the sun has burned all of its fuel, in many billions of years, the only chance of survival for humans will be a virtual existence in gigantic computers. Tipler conceives of the goal of these cosmological developments as the Omega Point, which he identifies with God (Tipler Citation1995).

What unifies all posthumanist authors is their shared vision of a future virtual habitat where humans achieve immortality, a prospect that arises as a byproduct of the self-directed progress of artificially intelligent posthuman entities. In this context, posthumanism can be seen as an expansive media utopia, underpinned by two interconnected elements: the overcoming of humanity and the overcoming of mortality. Without the promise of human immortality, advocating for an era dominated by artificial intelligence and the demise of humanity would indeed appear absurd. However, when viewed through the lens of this promise, the attainment of immortality, omniscience, beauty, and physical potency all seem within reach, contingent solely upon the will of humans.

The singularity is near

The idea of the dawning of a new age of artificial intelligence has gained recognition far beyond the transhumanist milieu, primarily through Ray Kurzweil’s book The Singularity Is Near (Citation2005) and the founding of Singularity University in 2008. Strictly speaking, it is not a university at all, and in fact has nothing to do with the singularity but offers workshops, conferences, and consulting for business leaders, start-up founders, and even some idealists promoting ‘disruptive’ innovations.

The concept of the singularity encompasses scientific concepts within mathematical function and system theory, geometry, solid-state physics, cosmology, and cybernetics. The last two areas in particular hold special significance for posthumanism; even when merely scratching the surface of the history of ideas, it quickly becomes clear that they are closely interwoven. Both fields have numerous references in common, especially to the work of Jesuit philosopher and palaeontologist Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1881–1955) and his concept of the Omega Point (Teilhard de Chardin Citation1976).

We will approach the concept of singularity in three steps. The first two sections on cosmological and technological singularity, respectively, precede a cultural-historical contextualization of the concept itself.

Black holes, God, and cosmological singularities

The term ‘singularity’ has been widely used in English since the 1970s, as well as being creatively applied in literature and television series for mass audiences. According to cosmologists Stephen Hawking and Roger Penrose, singularities (in the plural) denote special conditions of space and time, such as those created by black holes. The beginning of the universe – the Big Bang – was marked by a singularity (Hawking and Penrose Citation1970).

Together with fellow cosmologist John D. Barrow, Frank Tipler steered the concept of cosmological singularities into philosophical realms that encompass questions of life and humanity’s place in the universe. The two cosmologists have reflected on both the initial and the final singularity, that is, the beginning and the end of the universe. Here, Barrow and Tipler identify analogies with Teilhard de Chardin’s work and equate the final singularity with the divine Omega Point (Barrow and Tipler Citation1986, 201–204, 470–471). In his later works, Physics of Immortality (Citation1995) and Physics of Christianity (Citation2007), Tipler builds on these considerations and embeds the cosmological singularities in a theological framework, that is, not only that God is the final goal of the universe, but that God is also its original cause.

According to Tipler, the earth’s biosphere is beginning to expand into space in our present age in order to save the universe via colonization. In a 2013 interview with ‘Socrates’ from the Singularity Blog, he describes the properties of the final cosmological singularity as follows:

The singularity is outside the natural world, it is beyond the natural world, and it is transcendent to the natural world. So, approaching the singularity […] the amount of information, the amount of knowledge is approaching infinity as you are going into the final state. The processing rate is increasing to infinity. So, the total amount of information processing will be infinite. (Tipler Citation2013)

Assuming that humanity is the only intelligent life form in the cosmos (which is mathematically proven, according to Tipler), earthly life forms must find a new vehicle: ‘Namely, that eventually human meat, rational beings will be replaced by human downloads and our artificial intelligence of reason at least at the human level’ (Tipler Citation2013).

The technological singularity

Post – and transhumanists identify a remark in the 1950s by the mathematician and cyberneticist John von Neumann as the origin of the concept of technological singularity (Krüger Citation2021, 196–198). A quarter of a century later, American mathematician and science fiction author Vernor Vinge explicitly bridged the gap between the cosmological and technological concepts of singularity for the first time: ‘We will soon create intelligences greater than our own. When this happens, human history will have reached a kind of singularity, an intellectual transition as impenetrable as the knotted space–time at the center of a black hole, and the world will pass far beyond our understanding’ (Vinge Citation1983, 10). Vinge expects nothing less than superhumanity from this breakthrough (Vinge Citation2013, 366). However, everything that will occur after the singularity is completely unknowable as in the case of the space–time beyond the event horizon of black holes in astrophysics (Vinge Citation2013, 367).

Eliezer Yudkowsky was the first thinker to transform the idea of technological singularity into a far-reaching philosophical concept through the formulation of the Singularitarian Principles in 1999. He served as cofounder of the Singularity Institute for Artificial Intelligence (today MIRI), which propelled the singularity debate through its Singularity Summits in the late 2000s. His large and often rambling document contains many ambitious statements on ‘ultra-technology,’ globalization, the deification of humans (apotheosis), and solidarity, as well as some minor aspects. Singularitarians are in his view ‘partisans’ who consider technological singularity as superhuman intelligence to be a highly desirable goal towards which to work. The young Yudkowsky was characterized by a messianic optimism: ‘I’m working to save everyone, heal the planet, solve all the problems of the world’ (Yudkowsky Citation2000).

Ray Kurzweil’s three key books – The Age of Intelligent Machines (Citation1990), The Age of Spiritual Machines (Citation1999), and The Singularity Is Near (Citation2005) – offer a dramatic development with a steady increase in futuristic statements. As his trilogy concludes, however, he crosses the boundary between technical prophecy and a spiritual philosophy that is more akin to Christianity or New Age beliefs. Kurzweil identifies five stages in the history of evolution leading up to the realization of the singularity: (1) the origin of matter, (2) the origin of life, (3) the origin of brains/mind, (4) the origin of technology, and (5) the fusion of human and machine intelligence. In a sixth phase, superhuman intelligence will begin to colonize the entire universe (Kurzweil Citation2005, 14–111). Although Kurzweil does not disclose the origin of his ideas, the first three stages and the last one correspond to Teilhard de Chardin’s metaphysical concept of evolution, which proceeds through cosmogenesis (matter), biogenesis (life), and noogenesis (mind) to the final convergence of all life in Omega (Teilhard de Chardin Citation1976).

The singularity, which, like the Big Bang, entails creating the entire cosmos anew, marks the absolute climax of this technological prophecy. Kurzweil only defines this concept briefly: ‘It’s a future period during which the pace of technological change will be so rapid, its impact so deep, that human life will be irreversibly transformed’ (Citation2005, 7). A more precise description is not possible for humans: ‘So how do we contemplate the Singularity? As with the sun, it’s hard to look at directly; it’s better to squint at it out of the corner of our eyes’ (Citation2005, 371). Diane Proudfoot points out that this metaphor echoes the doctrine of God’s indescribability, which was common in Christian mysticism. Anselm of Canterbury proclaimed in the 11th century, ‘I cannot look directly into [the light in which God dwells], it is too great for me […] It is too bright […] The eye of my soul cannot bear to turn towards it for too long’ (Proudfoot Citation2012, 368).

Kurzweil accentuates the prophetic meaning of his statements by giving the exact date of the singularity as the year 2045 (Kurzweil Citation2005, 136). While his criteria for constituting the realization of the singularity remain rather vague, the promised prospects are boundless. Kurzweil announces that all the magic described in the Harry Potter novels together with the promise of immortality will soon be available (Kurzweil Citation2005, 4–9).

In addition to these individual aspirations of self-perfection, the posthumanist utopia also encompasses a crucial collective dimension. All posthumanist authors consider transferring the human mind into a computer to merely be an intermediate step on the path towards a planetary or even cosmic consciousness. While humans will survive the ages as perfect simulations within computers, robots and AI shall master the challenges of the real world. Robot probes would then colonize the solar system, the galaxy, and ultimately the entire universe, transforming it into a single thinking entity. Once artificial beings have gained initial control, they can go on to master entire galaxies in the interest of humankind and the cosmos (Kurzweil Citation2005, 342–365; Moravec Citation1999, 87, 164–168; Tipler Citation1995, 55–65). If the goal of evolution is the preservation of life in the universe, as Tipler argues, then perfecting humans or their descendants by maximizing knowledge is necessarily a part of this plan. Life would therefore attain omnipresence, omnipotence, and omniscience (Tipler Citation1995, 153–154). Like Tipler, Kurzweil thus deduces the earth’s special significance, and the future creation of the ‘ultimate computer’, when all individuals will have merged into one single and universal consciousness. Tipler and Kurzweil equate this emerging being with God (Kurzweil Citation2005, 375; Tipler Citation1995, 55–65).

This cosmic super-consciousness as posthumanists’ final evolutionary goal is the result of a complex process of reception and reinterpretation in a long intellectual lineage. It primarily originates in Teilhard de Chardin’s teleological theory of evolution, and the adoption of that theory by Marshall McLuhan in media theory. Thus, when Frank Tipler reintroduced Teilhard’s Omega Point, or Hans Moravec and Ray Kurzweil shared their visions of transforming the entire cosmos into one thinking entity, they are merely manifesting the latest iteration of a long tradition that had already been present in New Age philosophy for many decades (Krüger Citation2015).

At the same time, as Randy Connolly (Citation2001, 317–364) has shown, this utopian vision of total community is not novel but part of a recurring pattern in interpreting innovative media technologies over the past centuries. Technologies ranging from the telegraph to the radio have similarly been heralded by certain commentators as the dawn of a new, liberal age in which humanity would grow together into a harmonious global community.

The cultural context of the singularity idea

Social, psychological, and cultural factors play a central role in the proclamation of a coming technological revolution. Nick Bostrom acknowledges that, since the 1940s, the prognoses for the realization of a universal AI have been postponed year after year, usually remaining about twenty years away (Bostrom Citation2014, 4). If a technological event is generally expected to occur in about two decades, regardless of when or by whom this prognosis was made, then it becomes important to consider the social dynamics and cultural dimension of this futurology more closely (Armstrong and Sotala Citation2012).

What elements constitute the singularity as a temporal concept? First, the singularity is justified by laws of progress and acceleration. Furthermore, the singularity obviously constructs a threshold or boundary – which echoes the idea of the frontier that is so central in American cultural history (including its adaptations in the science fiction genre). Posthumanists usually do not justify the appearance of the singularity – or of AI generally – by revelations or prophecies, but rather by a mathematical theory of progress (e.g., Moore’s Law). A general doctrine of progress was already formulated during the late Enlightenment by French positivists and English utilitarians such as Condorcet or Jeremy Bentham, for whom the progress of the human race and the individual was attributed to the law of nature. At the same time, the view became widespread that the progress of past ages not only ensured future progress but would also gradually accelerate. According to Francis Bacon, Adam Smith, Edward Gibbon, Immanuel Kant, and many other thinkers of that time, the fact of accelerating progress was undeniable for technical and scientific fields. In this way, they deduced the law of progress from both the observation of the past and their hopes for the future (Krüger Citation2021, 153–192).

The inclusion of a utopian perspective to legitimize the incessant acceleration of progress is a characteristic feature of every such ideology. Two centuries before Kurzweil, the assumption of a momentous future acceleration of progress already served two crucial purposes. It not only promised benefits that would manifest within one’s lifetime, but also assured those who were wholeheartedly invested in the process that their efforts would bear fruit.

In addition to this idea of increasing acceleration, another crucial allusion to American cultural history is found in the understanding of the singularity as the final frontier. Since Puritans settled Massachusetts in the 17th century, the ‘frontier’ has marked the border of the civilized and moral world against the wilderness. The Christian-colonial sense of missionary purpose was further reinforced in the 1840s, when expansionist tendencies in American politics were merged with the project of spreading freedom and democracy. American Christians believed that the ‘manifest destiny’ of God’s chosen American people was to sow progress, civilization, and freedom in the wild and untamed vastness of the continent (Torr Citation2002, 69–77).

As conceptualized by Vinge, Yudkowsky, and Kurzweil, the singularity is based on this important metaphor of the endless frontier. The singularity in the sense of a black hole’s event horizon remains impenetrable and insurmountable for humans. But for AI, the singularity would be the beginning of an unlimited expansion into the universe in which humans are allowed to participate. As indicated, this perception of singularity as the ultimate boundary to be overcome has already been popularized by numerous adaptations in science fiction stories and films (as, e.g., in the 1989 movie Star Trek V, in which God is said to be found behind The Final Frontier).

There is also no question that the temporal moment of the singularity is influenced by the Christian end of days. The overcoming of old age, illness, and death corresponds to the Christian expectation of salvation. However, in the Christian and Jewish traditions, salvation is dependent on God’s judgment of one’s moral conduct, available only for those who qualify. According to all posthumanist authors, the singularity makes immortality available to every living human being; Tipler even expects the resurrection of all past humans.

What is remarkable in this posthumanist singularity utopia is its own singularity or uniqueness: The authors expect the emergence of one single breakthrough that creates one superintelligence that will solve all of humanity’s problems. In this regard, first Vinge (Citation1993; Citation2013, 366–367) and later many other authors (Bostrom Citation2014, 4; Kurzweil Citation2005, 22–23) refer to British mathematician Irving John Good’s Citation1965 essay ‘Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine’ as the originator of the idea of this kind of superintelligence. Good was not only convinced that this machine was the last invention that humans need ever make, but that it would govern all humankind and will ultimately convert the world’s population into a single ultra-intelligent community under the slogan: ‘Oracles of the world unite!’ (Good Citation1962, 195).

It is increasingly probable that the anticipation of a singular AI entity will soon be recognized as a historical relic of early AI discourse. As large language model-based chatbots and deep learning algorithms gain widespread popularity, it becomes evident that a diverse array of applications will emerge, driven by various enterprises or governmental entities (as seen in China), each tailoring these technologies to meet their distinct commercial or political requirements. The notion of a singular, universal AI does not align with the actual trajectory of development. Nonetheless, it’s important to note that a linear concept of time, often linked to singular revolutionary events, remains a fundamental condition for many eschatological prophecies.

Science and religion entangled

It is clear that the prophecy of the singularity is strongly influenced by cultural and religious ideas. The assumption that there are universally valid laws of progress, as well as the claim of a universal, steady acceleration of progress throughout human history both can be traced back to the Enlightenment’s quest for perfection. What is new in the singularity idea is the introduction, by Vinge and Kurzweil, of the idea of an absolute and impenetrable limit to this progress: the singularity as the ‘final frontier’. The term echoes the language of black hole physics, as well as the popularized representations of that cosmic phenomenon in literature and film. Even more astonishing is that the concept of singularity allows a religious teleology which fifteen years ago was dismissed as exotic to creep into contemporary post – and transhumanism. This occurs first structurally, with the entire history of earthly life being seen as heading towards a moment of salvation. Then it also happens in substantive terms, when Ray Kurzweil bluntly adopts Frank Tipler’s notion of the complete colonization of the universe, culminating in the realization of God.

Upon closer examination, we can speculate about the inclusion of religious elements in posthumanist futurology. At transhumanist conventions around the turn of the millennium, there was a prevailing optimism that all of humanity’s challenges could be expeditiously resolved. However, by the end of the first decade of the 21st century, a sense of disillusionment had set in as it became increasingly apparent that technologies for the immortality of the human mind were not realistically attainable in the near future, as indicated by a study conducted by Bostrom and Sandberg (Citation2008). The concept of the singularity, characterized by its enigmatic nature and imprecise attributes, provided a kind of relief from the necessity of formulating concrete solutions, as it posited that an omniscient superintelligence would eventually overcome all obstacles.

A second, even more fundamental question, which cannot be addressed solely through the framework of the laws of progress, pertains to the rationale behind the felt necessity for the replacement of humanity and the lack of accepted alternatives to this posthuman future. This scenario rests on the assumption that it is the destiny of either humanity or its posthuman descendants to save the universe and achieve the realization of God, provided that humanity is the sole intelligent life form in the universe, as proposed by Tipler and Kurzweil.

It is interesting to note that this opening to religious ideas in posthumanism parallels developments in science fiction literature, movies, and computer games. Literary scholar Elaine Graham points out that more recent science fiction is increasingly blatant in dissolving the boundary between religion and science, the secular and the sacred, humans and God, and faith and knowledge. These all appear increasingly less as polar opposites, but rather now merge and blur in a postsecular era. Dystopian visions no longer propagate the overcoming of religious superstition by a rationalist technoculture, but rather now celebrate the fusion of these two spheres (Graham Citation2015, 362).

This observation in turn reflects developments in the field of religion and spirituality that have been visible since the late 19th century (Mohn Citation2022, 42) and are particularly prominent in New Age philosophy. Hanegraaff (Citation1996, 62–76) pioneered this field and explored the broad reception of modern science in this alternative milieu. Stuckrad (Citation2014) paints an even wider picture in his study, The Scientification of Religion, examining discursive changes in fields such as astronomy and evolution from the year 1800–2000. He concludes,

In a closely related dynamic […] natural scientists adopted religious and metaphysical claims and integrated these in their work, resulting in a new discursive knot of RELIGION and SCIENCE – often combined with a reverence for nature – that gained much influence in the twentieth century. (Citation2014, 180)

Opposing science and religion

The evidence of the close entanglement presented above is contested by both transhumanist actors and Christian theologians. Therefore, to better understand this complex ‘knot’ we need to further explore the dynamic relations of secular and religious interpretations of the posthumanist utopia. In fact, post – and transhumanists approach the question of religion from many angles. Frank Tipler claims that his insights are based on scientific facts alone, although his understanding builds upon the long tradition of natural theology as well as on the physico-theology of the 18th century Protestant theologian William Paley and his contemporaries. Ray Kurzweil and transhumanist activist Martine Rothblatt even expect new spiritual dimensions to rise, complementing the expansion of human abilities in virtual existence. Most other post – and transhumanist authors, such as Marvin Minsky, Hans Moravec, Max More, Eliezer Yudkowsky, and Nick Bostrom, consider religion to instead be an obstacle, or even an enemy, of the technological overcoming of the biological human being and its immortalization (Krüger Citation2021, 61–103).

The heterogeneity within the transhumanist movement is manifest in the internal debates surrounding its precise definition. James Hughes and Nick Bostrom, in their scholarly work, have constructed a genealogical perspective of this movement, underscoring the significance of certain thinkers who harbored critical stances towards religion. Notably, French philosophers Condorcet and La Mettrie, as well as prominent Cambridge intellectuals J. B. S. Haldane, John D. Bernal, and Julian Huxley, have been identified as precursors to transhumanism within this lineage, despite the absence of concrete factual evidence to substantiate this claim. Instead, this lineage emerges as a product of constructed tradition, a concept elucidated by Hobsbawm (Citation2000). Simultaneously, it is worth noting that the influence exerted by theological authors such as Teilhard de Chardin has been systematically disregarded within this discourse, as documented by Hughes (Citation2004:, 156–159) and Bostrom (Citation2005:, 2–6).

The attempt to portray transhumanism as exclusively rooted in scientific futurology is particularly conspicuous in the discourse surrounding the concept of the singularity. Bostrom (Citation2014, 2) vehemently advocates for the avoidance of the term ‘singularity’ due to its association with what he describes as the ‘unholy alliance of techno-utopias with religious-eschatological elements’. More (Citation2013, 407) provides a forthright critique, denouncing the ‘orgiastic blend of technological utopias with Christian apocalypticism’. Finally, the transhumanist author Broderick (Citation2013, 398) takes a more satirical stance, characterizing the singularity as ‘crypto-mystical’ and ‘pseudo-religious’.

Many discussions just close with, ‘But we cannot predict anything about the post singularity world!’ ending all further inquiry just as Christians and other religious believers do with, ‘It is the Will of God.’ And it is all too easy to give the Transcension eschatological overtones, seeing it as Destiny. This also promotes a feeling of helplessness in many, who see it as all-powerful and inevitable. (Broderick Citation2013, 398)

At this juncture, it is not my intention to delve into its substantive argument. Instead, my objective is to elucidate the manner in which it employs a dichotomous separation of transhumanism and Christianity. For instance, Dürr overlooks the diffuse religious allusions made by Kurzweil and omits Tipler’s work from his comprehensive analysis of transhumanist thought. This omission results in the neglect of Tipler’s reception of Teilhard de Chardin. Dürr’s approach is distinct in that he characterizes the history of transhumanism through a strictly secular genealogical lens, with Julian Huxley, FM-2030, and Max More as key figures (Dürr Citation2021, 82–104). By referencing their criticism of religion and drawing parallels to Nietzsche, Dürr constructs a portrayal of transhumanism as a secular, bio-political, and this-worldly quasi-religion aimed at overcoming traditional religions and faith in God (similarly: Bishop Citation2018; Dürr Citation2021, 124–136). According to Dürr, the transhumanist utopia is characterized by ‘surrogates’ of ‘pseudo-mysterium’, ‘pseudo-sacramental logics’, ‘pseudo-transcendence’, and ‘pseudo-eschatology’ (Dürr Citation2021, 120, 279, 313, 343, 416, 493).

However, it is imperative to contextualize these constructions of both secular and theological ‘purity’ not only in light of the religious elements in posthumanist thought as delineated previously but also with respect to the broader framework of a diverse theological discourse. Other positions acknowledge, for example, a general compatibility of transhumanism with liberal Christian theology (Cole-Turner Citation2011; Mercer and Trothen Citation2021) or advocate for the incorporation of Christian values into transhumanism (Burdett Citation2015). This is not to mention the movements of Christian, Mormon, or Buddhist transhumanists (Borrmann Citation2023; Krüger Citation2021, 87–89).

Even from these preliminary observations, it is evident that both secular transhumanists and traditional theologians employ similar criteria and emphases in shaping their conceptions of transhumanist utopia and religion, framing them as opposing forces. As reciprocal antipodes, they rely on each other to validate their normative definitions of transhumanism and theology or religion, respectively. Accordingly, all possible gradations between their binary positions are simply brushed aside, dismissed, and forcefully excluded from the purview of the ‘true doctrine’. It is equally apparent from this analysis that, despite the extensive body of academic research on post – and transhumanism, it runs counter to the interests of stakeholders to acknowledge this complex entanglement of religion and science. Thus, actors defending opposing views share an ‘apologetic’ attitude aimed at maintaining clear boundaries between secular and religious perspectives.

The limited disenchantment of the world

How can we possibly conceive of a history of the future that contains the entirety of post – and transhumanist utopia? It is crucial to recognize that the relationship between transhumanism and religion is not accidental but a subject of ongoing contention among various actors within the futurist movement, theological circles, and academia. The effort towards a clear classification aligns with the prevailing narrative of secularization and modernity. From the perspective of its secular proponents, transhumanism signifies liberation, particularly from religious constraints. Conversely, traditional theology views transhumanism as a formidable threat to both Christian and humanist conceptions of humanity, even characterizing it as a ‘nightmare’ (Dürr Citation2023). These binary classifications of religion and non-religion are emblematic of the ‘myth of secularization’ (Luckmann Citation1969; Storm Citation2017, 270–287), which played a pivotal role in shaping the identity of ‘modern’ societies during the 19th and 20th centuries (Joas Citation2021, 10–30; Mohn Citation2022, 41–44; Trein Citation2020, 71–78).

For scholars of religion, posthumanism presents both a challenge and an opportunity to reevaluate fundamental concepts such as history, temporality, and modernity. As the latest evolution of Enlightenment philosophy of progress, posthumanism is intricately intertwined with the ongoing discourse surrounding secularization (Mohn Citation2022, 51–65). Central to this discourse is the pivotal question of whether the idea of secular progress and its associated objectives should be viewed as a secularized manifestation of Christian salvation history or as an independent, secular outcome stemming from the principles of the Enlightenment.

In this context, it could be beneficial to invoke Max Weber’s renowned concept of the ‘disenchantment of the world’ (Entzauberung der Welt). Given that Max Weber did not extensively expound upon this concept and only a limited number of passages in his work explicitly address it (Storm Citation2017, 270–287), surveying the multitude of interpretations in the current academic landscape presents a daunting challenge (Joas Citation2021, 110–133).

For my purposes, I would like to single out three aspects that are relatively undisputed among experts on Max Weber (as summarized, e.g., by Endreß Citation2020). Firstly, disenchantment refers to social processes pertaining to the legitimation of social action and social structure; these are no longer legitimized primarily by magic, but by a range of rational plausibilities. Secondly, it is important to recognize that this rational thought itself is a product of religion (in the West), where it can be traced back to the rational way of life espoused in puritanism. Thirdly, the disenchantment of the world does not mean the end of religion. Instead, it signifies that religion is no longer the predominant factor in legitimizing social action and social structure. As the world increasingly undergoes rationalization, religion itself takes on characteristics that are increasingly antirational and irrational, revolving around transcendent powers (Tyrell Citation1993).

The idea of progress

Max Weber’s rationalization thesis played a pivotal role in an ongoing discourse that spanned the whole 20th century and addresses the nuanced relationship between Christian theology and secular philosophies of progress. This research has given rise to two contrasting approaches. On one side, we find figures such as the English historian John B. Bury, the Protestant theologian Rudolf Bultmann, and the philosopher Karl Löwith, who heavily draw upon Weber’s ideas. At the opposite end of the spectrum, philosopher Hans Blumenberg occupies a distinctive position in this debate.

In 1920, Bury’s The Idea of Progress. An Inquiry into its Origin and Growth laid the groundwork for the first comprehensive account of modern theories of progress. In stark contrast to a religious history of salvation and the ultimate anticipated moment of divine providence, Bury defines the term progress as an ‘outcome of the physical and social nature of man’ that does not rely any more on the mercy of any external will (Bury Citation1955, 5). According to his interpretation, the idea of progress is understood in both France and England as the liberation of reason and rationality from the narrow confines of theological traditions:

The otherworldly dreams of theologians, which had ruled so long lost their power, and men’s earthly home again insinuated itself into their affections, but with the new hope of its becoming a place fit for reasonable beings to live in. (Bury Citation1955, 349)

Bury, Löwith, and Bultmann legitimize their theses by predominantly referring to the thoroughly anticlerical French progress philosophers of the 18th century, such as Fontenelle, Abbé de Saint-Pierre, Voltaire, Turgot, and Condorcet, as well as to Pierre Joseph Proudhon and Auguste Comte in the 19th century. Bultmann regards the European Enlightenment as the secularization of all human life and thought. Just as Christian teleology once promised transcendent salvation, the secular belief in progress now propagates human mastery of nature as a means to attain worldly happiness. Both the idea of this-worldly progress and the Christian notion of other-worldly salvation through providence remain ultimately incompatible with Löwith’s and Bultmann’s conceptions, just as they were with Bury’s (See Bultmann Citation1957, 56–73; Löwith Citation1949, 60–103).

The next generation of scholars, such as historian Reinhart Koselleck and philosopher Friedrich Rapp, continued down this path. They assume that, in modernity, the divine plan of salvation is now fulfilled by the philosophy of history, while secular theories of progress are satisfied by the open horizon of the future. This is reflected terminologically in the conceptual change from the spiritual profectus to the secular progressus. According to Koselleck, the temporalization of the goal of perfectio marks a decisive change in the doctrine of perfection. Once found only in God and the associated perfectio seu consummatio salutis, this salvation has now become an earthly goal to strive for. During the 19th century, the notion of progress evolved into a form of secular religion; today, it serves as a political, economic, and cultural catchword (See Koselleck Citation1975, 371–377, 411; Rapp Citation1992, 58–59, 187–190).

The philosopher Hans Blumenberg has fundamentally criticized the popular thesis of the secularization of Christian salvation. He is adamantly opposed to the overuse of the term ‘secularization’ in historical research. Blumenberg invokes the category of historical illegitimacy, as he considers the general and infinitely strained thesis of secularization to be permeated by theological implications. For this whole dimension of hidden meaning would always ascribe a subliminal theological implication to secular philosophy, politics, science, and culture. For Blumenberg, this is especially problematic for the idea of progress, and he defends the thesis of an independent development of secular, enlightened philosophy in open contrast to theological thought (Blumenberg Citation1986, 27–76).

Bury, Bultmann, Löwith, Koselleck, Rapp and Blumenberg developed concepts presupposing a strong demarcation, or even incompatibility, between theological and secular understandings of history, where the latter is seen as emerging from the former or – in the case of Blumenberg – in contrast to the former. Irrespective of its English and French particularities, progress was assumed to be a constant, secular, and enlightened concept. While the philosophical approaches of Bury and others are in line with the general narration of secularization, the lack of empirical evidence gives rise to constant criticism.

Numerous historians have identified weaknesses in the thesis of the incompatibility between the ideas of worldly progress and divine providence. John Baillie, Arthur Ekirch, and especially David Spadafora have all emphasized that, despite the undisputed influence of the French philosophes, the English and American ideas of progress have produced a unique synthesis of this-worldly progress and Christian salvation history. The vast majority of British or American 18th-century philosophers – including well-established thinkers such as Joseph Priestley, David Hartley, Adam Ferguson, and Richard Price – regarded progress as a divine program moving in step with humanity’s maturity. The full amount of bliss and happiness would only unfold for humankind at the end of time. The complexity, beauty, and well-documented historical development of the world forced them to conclude that the Earth, and humankind with it, cannot be an accidental phenomenon and therefore must be based on a divine plan. According to Priestley, humanity is now responsible for following this path to create a better world, and to use its God-given abilities and powers for the benefit of all. Secular and religious progress are thus merely different sides of one and the same historical process. While English philosophers were no less euphoric than the French in advocating for the secular aspects of progress in politics, education, medicine, technology, and science, the semantic context of this concept remained in most cases explicitly Christian. The necessity of scientific discoveries was interpreted as strengthening religion and defending it against the irreligious tendencies of the natural sciences (Baillie Citation1950, 146–154; Ekirch Citation1944, 41–130; Spadafora Citation1990, 85–132, 248).

In the American context, we cannot maintain that the Christian concept of providence has simply been replaced by the prospect of a this-worldly improvement in living conditions. In the United States, the Christian history of salvation is thus not overwritten by modern ideas of progress but is rather their major driving force. Millenarianism became increasingly popular thanks to its ability to create order in an age of rapid and diverse innovation. Indeed, it offered an explanation not only of why such advancement should occur, but also why we should actively strive for it (Benz Citation1965, 157–181; Spadafora Citation1990, 105–131).

Against this background, it becomes clear why the singularity and the cosmic divine destination of the Omega Point were integrated into posthumanism. Although secular transhumanists, such as Bostrom, Yudkowsky, and More, are visibly uncomfortable with this techno-religious synthesis, the discussion has clearly shifted since the turn of the millennium. While at that time I could describe Frank Tipler’s Omega Theory as exotic, its core elements now form the heart of post – and transhumanism. Alongside Ray Kurzweil’s interpretation of singularity, a teleology of salvation history has developed that is specifically designed to transform the cosmos into a thinking universe. The goal of this process is the realization of God. Posthumanism thus finds itself continuing the tradition of the English moral philosophers of the 18th century, for whom final perfection can only be achieved via a union with God. This also blurs the boundaries between the cosmological and the technological concepts of singularity. The human endeavor is now characterized by regaining the Paradise Lost – which John Milton so strongly established as the mission of the New World – in union with God and all humanity.

Relating multiple temporalities

In a recent discussion of the narratives of secularization, Trein (Citation2020) introduced the concept of multiple temporalities of the Norwegian historian Jordheim (Citation2014). Temporalities are social concepts of historicized experiences, such as progress, secularization, or disenchantment, and are often linked to historical models of periodization. Trein questions the validity of these temporalities as historically modes of presentation and suggests that they should rather be understood as a specifically modern form of historical self-description (Trein Citation2020, 71–73). This insight is relevant not only to contextualize contemporary interpretations of history but also to rethink and retheorize the temporal framings we apply as scholars of religion.

For example, Trein shows how certain theological interpretations of historical evolution were influential on the formation of Weber’s disenchantment thesis. In other words, Weber’s approach could only emerge in relation to the theological diagnoses of his time; for many theologians and philosophers the temporal framing of secular modernity implies the idea of religious inheritances in a disenchanted world (Trein Citation2020, 80–84).

Drawing on ideas from Löwith and Koselleck, Trein challenges the linear narration of secularization, according to which a religious past has been replaced by a secular modernity or is seen as the continuity of this bygone religious past. He aims to overcome this binary logic that requires the choice between continuity and discontinuity. His strategy consists in emphasizing the complex temporal relations in which the continuities, ruptures, and recurrences are constantly taking shape, and are contested and rearranged (Trein Citation2020, 71–77).

So far, Trein has limited his perspective to historical genealogies of secular modernity, but as we have seen above, narratives of the past and the future are closely related and mutually legitimize the future prognosis and the selective reading of the past to form a strong teleological narrative. Including the future (or the histories of future) in the multiple temporalities approach is a necessity to comprehend the dynamic interplay of these entangled religious and secular temporalities – especially if we acknowledge that the relationship between ideas of secular progress and divine providence is at the heart of most secularization debates.

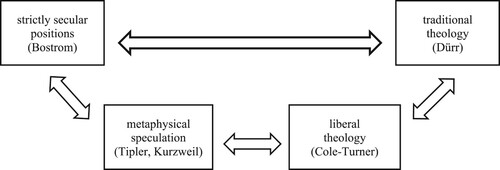

With this in mind, the various positions on transhumanist futurology emerge as a broad spectrum, ranging from strictly secular legitimations, as with Bostrom, to those that rest on metaphysical assumptions, as with Tipler and Kurzweil, and liberal theologies, as with Cole-Turner, to complete rejection in the name of traditional theologies, as with Dürr. It is important to note that the various interpretations of progress rely on and react more or less explicitly to each other, defining the ‘purity’ of a secular/scientific or Christian interpretation of the future correspondingly. All can thus be said to follow the secularization narrative. Alternative positions vary widely but contain a common understanding that progress ultimately is providence, so that transhumanist, Christian, or spiritual positions may prove compatible in principle ().

The persistence of multiple temporalities

At the latest with the emergence of Deism in the 18th century, we can observe a tripolar structure that complements the opposing secular and traditional religious interpretations of history and the future with heterogeneous positions that reconcile science and religion. The historical evidence confirms that these three poles are persistent (even a quasi ‘medieval eschatology’ that today interprets, e.g., catastrophes as signs of Christ’s second coming is enduring). The persistence of this basic structure, however, is not founded on the immutability of these positions but, on the contrary, on the dynamics of their mutual relations. The relations bring forth the relata in an endless loop of negotiations and reconfigurations.

With regard to posthumanism, we have seen how this dynamic relation proves to be a major force to constantly contest and at the same time reaffirm the elements in this triangle, thereby providing a meaningful universal framework. The future never dies – its contingency always allows and even demands new interpretations of the fate of humanity, the world and the individual. Thus, highly speculative assumptions surrounding the singularity thesis do not generally weaken posthumanist futurology but make it more compelling for many of its advocates. Even for those who disagree with the religious connotations, the debate provides an opportunity to emphasize their ‘purely scientific’ position.

To return to Weber’s thesis of disenchantment, he clearly rejects the thesis of a universal rationalization and points out that certain segments of society react differently to this process. However, he does not develop a genuine thesis of plurality (Endreß Citation2020, 436; Weber Citation2005, 37–38). Moreover, according to Weber, religion becomes an irrational antagonist in the increasingly rationalized modern age, opposing the progress of science and technology, as we saw above.

In fact, it was Weber’s younger brother Alfred, who produced a more nuanced answer to this problem. In his sociology of culture, Weber (Citation1951, 488–498) distinguishes between the steady and cumulative progress of science and technology and the movement of culture which generates ever-new interpretations of the world, of history, of society and of individual existence. His former student, the sociologist Karl Mannheim, adopts this idea in his seminal 1929 work Ideologie und Utopie, while demonstrating how the ‘utopian consciousness’ came into being in the early 16th century as a fusion of otherworldly Christian ideals and social revolutionary goals (Mannheim Citation1995, 184–203).

More recently, Taylor (Citation2007, 423–538) and Joas (Citation2021, 88–152) reject linear or dialectic historical interpretations of modernity, both disenchantment and its inverse, the re-enchantment thesis. They understand modernity as ‘a complex and unpredictable plethora’ of non-linear historical processes (Joas Citation2021, 249) which are in fact ‘incredibly complicated, with wide variations between different countries, regions, classes, milieux’ (Taylor Citation2007, 424).Footnote2 Although Taylor and Joas – just as Alfred Weber before them – agree in dismissing a general thesis of disenchantment and its more recent derivations, they all aim to establish new universal narratives of modernity that overcome the shortcomings of earlier ones. Within this framework, sociological approaches that maintain the ‘binary taxonomy’ of a super-historical, functional differentiation between religion and secularity (Kleine and Wohlrab–Sahr Citation2021, 48–62) are nothing more than one of many possible narratives of modernity (Daniel Citation2016, 121–127). And yet, in his epilogue to A Secular Age, Taylor at least acknowledges that there are possibly many other stories of ‘Western secularization’ (Citation2007, 773–776).

The epistemological pitfall of these approaches is rooted in the paradoxical tension between sociological observers and their social objects. Mannheim (Citation1980, 54), as one of the early proponents of the sociology of knowledge, emphasized that all sociological descriptions and analyses of the world are at the same time also objects for research. Later, Berger and Luckmann (Citation1991, 25) turned this problem into the famous metaphor of ‘trying to push a bus in which one is riding’. In our context ‘[…] narratives of disenchantment and secularization presuppose and conflate both historical self-descriptions and theoretical assumptions about the historical.’ (Trein Citation2020, 85)

The multiple temporality approach allows us to integrate sociological and philosophical theories within the plurality of possible interpretations of history and the future. This means overcoming the claims of a homogeneous narration of modernity:

It seems far more likely to assume that modernity consists of various historical times interfering with each other and existing simultaneously in complex layers of synchrony. (Trein Citation2020, 72)

As a first consequence of this perspective, it is possible to capture the reciprocal relations of the different narrations, as they are dependent on each other (McCutcheon Citation2007, 179). Second, it reveals the constructive character of the key terms in these narratives, such as ‘secular,’ ‘modern,’ ‘religion,’ and so on. The boundaries of this bipolar modern universe are thereby blurred, and the field is opened up to reveal all the complexities and contradictions in the narrations of history and future (as have already been present in cyberpunk literature for many decades). Here, the utopia of the singularity is nothing else than ‘[…] a load of religious junk. Christian mystic rapture recycled for atheist nerds.’ (Stross Citation2005, 184)

Acknowledgments

The Author thanks the editors, Anja Kirsch and Andrea Rota, for their energy and perseverance, which extend all the way back to the EASR conference in Pisa.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Oliver Krüger

Oliver Krüger After holding academic posts in Bonn, Heidelberg and Princeton, Oliver Krüger has been Professor of the Study of Religions at the University of Fribourg (Switzerland) since 2007. His research covers the fields of religion and media, posthumanism and transhumanism, as well as the theory of religion. His most recent publication is Virtual Immortality. God, Evolution, and the Singularity in Post – and Transhumanism. Bielefeld: transcript 2021.

Notes

1 This type of posthumanism must be distinguished from philosophical or critical posthumanism, which has also emerged in the past three decades. Here, thinkers like Rosi Braidotti, Karen Barad, and Cary Wolfe have incorporated approaches from post-structuralist literary studies and adapted them to criticize Eurocentric and androcentric humanism (Herbrechter Citation2013).

2 There is no space here to discuss the many assumptions in their works, such as the ‘axial age’ (Weber, Taylor, Joas), self-sacralization (Joas), the decline of religious nationalism (Taylor) and the overall turn to religious experience (Taylor, Joas).

References

- Armstrong, Stuart, and Kaj Sotala. 2012. “How We’re Predicting AI – or Failing To.” In Beyond AI: Artificial Dreams, edited by Jan Romportl, Pavel Ircing, Eva Zackova, Michal Polak, and Radek Schuster, 52–75. Pilsen: University of West Bohemia.

- Baillie, John. 1950. The Belief in Progress. London: Oxford University Press.

- Barrow, John D., and Frank J. Tipler. 1986. The Anthropic Cosmological Principle. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Benz, Ernst. 1965. Schöpfungsglaube und Endzeiterwartung. Antwort auf Teilhard de Chardins Theologie der Evolution. München: Nymphenburger.

- Berger, Peter L., and Thomas Luckmann. (1966) 1991. The Social Construction of Reality. A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge. London: Penguin.

- Bishop, Jeffrey P. 2018. “Nietzsche’s Power Ontology and Transhumanism: Or Why Christians Cannot Be Transhumanists.” In Christian Perspectives on Transhumanism and the Church, edited by Steve Donaldson, and Ron Cole–Turner, 117–135. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Blumenberg, Hans. (1966) 1986. The Legitimacy of the Modern Age, translated by Robert M. Wallace. Cambridge: MIT Press.

- Borrmann, Vera. 2023. “Reflections on Perspectives of Transhumanism, Buddhist Transhumanism, and Buddhist Modernism on the Self.” Nanoethics 17 (13): 1–6.

- Bostrom, Nick. 2005. “A History of Transhumanist Thought.” Journal of Evolution and Technology 14 (1): 1–25.

- Bostrom, Nick. 2014. Superintelligence. Paths, Dangers, Strategies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bostrom, Nick, and Anders Sandberg. 2008. Whole Brain Emulation. A Roadmap. Technical Report #2008-3. Oxford: Future of Humanity Institute.

- Broderick, Damien. (2000) 2013. “A Critical Discussion of Vinge’s Singularity Concept.” In The Transhumanist Reader, edited by Max More, and Natasha Vita-More, 397–399. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Bultmann, Rudolf. 1957. History and Eschatology. The Gifford Lectures 1955. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Burdett, Michael S. 2015. Eschatology and the Technological Future. New York: Routledge.

- Bury, John B. (1920) 1955. The Idea of Progress. An Inquiry Into Its Origin and Growth. New York: Dover.

- Cole-Turner, Ron. 2011. Transhumanism and Transcendence: Christian Hope in an Age of Technological Transcendence. Washington D.C.: Georgetown University Press.

- Cole–Turner, Ron, and Steve Donaldson, eds. 2018. Christian Perspectives on Transhumanism and the Church: Chips in the Brain, Immortality, and the World of Tomorrow. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Connolly, Randy. 2001. “The Rise and Persistence of the Technological Community Ideal.” In Online Communities. Commerce, Community Action and the Virtual University, edited by Chris Werry, and Miranda Mowbray, 317–364. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall PTR.

- Daniel, Anna. 2016. Die Grenzen des Religionsbegriffs. Eine postkoloniale Konfrontation des religionssoziologischen Diskurses. Bielefeld: Transcript.

- Dürr, Oliver. 2021. Homo Novus. Vollendlichkeit im Zeitalter des Transhumanismus. Beiträge zu einer Techniktheologie. Münster: Aschendorff.

- Dürr, Oliver. 2023. Transhumanismus – Traum oder Alptraum? Freiburg: Herder.

- Ekirch, Arthur A. 1944. The Idea of Progress in America, 1815–1860. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Endreß, Martin. 2020. “Renaissance der Religion: Was wird aus Max Webers Entzauberungs- und Säkularisierungsthese?” In Max Weber Handbuch. Leben – Werk – Wirkung, edited by Hans-Peter Müller, and Steffen Sigmund, 435–442. Heidelberg: Metzler.

- Good, Irving J. 1962. “The Social Implications of Artificial Intelligence.” In The Scientist Speculates: An Anthology of Partly-Baked Ideas, edited by Irving J. Good, 192–198. London: Basic Books.

- Good, Irving J. 1965. “Speculations Concerning the First Ultraintelligent Machine.” Advances in Computers 6: 31–88.

- Graham, Elaine L. 2015. “The Final Frontier? Religion and Posthumanism in Film and Television.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Posthumanism in Film and Television, edited by Michael Hauskeller, Thomas D. Philbeck, and Curtis Carbonell, 361–370. New York: Palgrave.

- Hanegraaff, Wouter J. 1996. New Age Religion and Western Culture. Esotericism in the Mirror of Secular Thought. Leiden: Brill.

- Hawking, Stephen, and Roger Penrose. 1970. “The Singularities of Gravitational Collapse and Cosmology.” Proceedings of the Royal Society 314: 529–548.

- Hayles, N. Katherine. 1999. How We Became Posthuman: Virtual Bodies in Cybernetics, Literature and Informatics. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Herbrechter, Stefan. 2013. Posthumanism. A Critical Analysis. London: Bloomsbury.

- Hobsbawm, Eric. 2000. “Introduction: Inventing Traditions.” In The Invention of Tradition, edited by Eric Hobsbawm, and Terence Ranger, 1–14. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hölscher, Lucian. 2018. “Future Thinking – A Historical Perspective.” In The Psychology of Thinking About the Future, edited by Gabriele Oettingen, A. Simur Sevincer, and Peter M. Gollwitzer, 15–30. New York: Guildford Press.

- Hughes, James. 2004. Citizen Cyborg. Why Democratic Societies Must Respond to the Redesigned Human of the Future. Cambridge, MA: Westview Press.

- Joas, Hans. (2017) 2021. The Power of the Sacred: An Alternative to the Narrative of Disenchantment. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Jordheim, Helge. 2014. “Introduction: Multiple Times and the Work of Synchronization.” History and Theory 53 (4): 498–518.

- Kleine, Christoph, and Monika Wohlrab–Sahr. 2021. “Comparative Secularities: Tracing Social and Epistemic Structures Beyond the Modern West.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 33 (1): 43–72.

- Koselleck, Reinhart. 1975. “Fortschritt.” In Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe. Historisches Lexikon zur politisch-sozialen Sprache in Deutschland, Vol. 2, edited by Otto Brunne, Werner Couse, and Reinhart Kosselleck, 351–423. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta.

- Krech, Volkhard. 2020. “Relational Religion: Manifesto for a Synthesis in the Study of Religion.” Religion 50 (1): 97–105.

- Krüger, Oliver. 2015. “Gaia, God, and the Internet – Revisited. The History of Evolution and the Utopia of Community in Media Society.” Online – Heidelberg Journal for Religions on the Internet 8: 56–87.

- Krüger, Oliver. 2021. Virtual Immortality. God, Evolution, and the Singularity in Post– and Transhumanism, translated by Ali Jones and Paul Knight. Bielefeld: transcript.

- Krüger, Oliver. 2022. “From an Aristotelian Ordo Essendi to Relation: Shifting Paradigms in the Study of Religions in the Light of the Sociology of Knowledge.” Numen 69 (1): 61–96.

- Kurzweil, Ray. 1990. The Age of Intelligent Machines. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Kurzweil, Ray. 1999. The Age of Spiritual Machines: When Computers Exceed Human Intelligence. New York: Viking Press.

- Kurzweil, Ray. 2005. The Singularity Is Near: When Humans Transcend Biology. New York: Penguin.

- Löwith, Karl. 1949. Meaning in History. The Theological Implications of the Philosophy of History. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Luckmann, Thomas. 1969. “Secolarizzazione: Un Mito Contemporaneo.” Cultura e Politica 14: 175–182.

- Mannheim, Karl. (1922) 1980. “Über die Eigenart kultursoziologischer Erkenntnis.” In Strukturen des Denkens, edited by David Kettler, Volker Meja, and Nico Stehr, 33–154. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- Mannheim, Karl. (1929) 1995. Ideologie und Utopie. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp.

- McCutcheon, Russell T. 2007. “They Licked the Platter Clean: On the co-Dependency of the Religious and the Secular.” Method & Theory in the Study of Religion 19 (3–4): 173–199.

- Mercer, Calvin, and Tracy J. Trothen, eds. 2021. Religion and the Technological Future: An Introduction to Biohacking, Artificial Intelligence, and Transhumanism. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mohn, Jürgen. 2022. “Religionisierte Technik. Zur Religionsdiskursgeschichte des technologischen Dispositivs.” In Immanente Religion – Transzendente Technologie. Technologiediskurse und gesellschaftliche Grenzüberschreitungen, edited by Sabine Maasen, and David Atwood, 41–68. Leverkusen: Budrich.

- Moravec, Hans. 1979. “Today’s Computers, Intelligent Machines and Our Future.” Analog. Science Fiction/Science Fact 99 (February): 59–84.

- Moravec, Hans. 1988. Mind Children: The Future of Robot and Human Intelligence. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Moravec, Hans. 1999. Robot. Mere Machine to Transcendent Mind. New York: Oxford University Press USA.

- More, Max. 2013. “A Critical Discussion of Vinge’s Singularity Concept.” In The Transhumanist Reader, edited by Max More, and Natasha Vita-More, 406–409. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Proudfoot, Diane. 2012. “Software Immortals: Science or Faith?” In Singularity Hypothesis. A Scientific and Philosophical Assessment, edited by Amnon H. Eden, James H. Moor, Johnny H. Søraker, and Eric Steinhart, 367–394. Berlin: Springer.

- Rapp, Friedrich. 1992. Fortschritt. Entwicklung und Sinngehalt einer philosophischen Idee. Darmstadt: WBG.

- Spadafora, David. 1990. The Idea of Progress in Eighteenth-Century Britain. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Storm, Jason A. 2017. The Myth of Disenchantment. Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of Human Sciences. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Stross, Charles. 2005. Accelerando. London: Penguin.

- Stuckrad, Kocku von. 2014. The Scientification of Religion. An Historical Study of Discursive Change, 1800–2000. Berlin: DeGruyter.

- Taylor, Charles. 2007. A Secular Age. Cambridge, MA: Belknap.

- Teilhard de Chardin, Pierre. (1955) 1976. The Phenomenon of Man. New York: Harper & Brothers.

- Tipler, Frank J. 1995. The Physics of Immortality. Modern Cosmology, God and the Resurrection of the Dead. New York: Anchor.

- Tipler, Frank J. 2007. The Physics of Christianity. New York: Penguin.

- Tipler, Frank J. 2013. “The Laws of Physics Say: The Singularity Is Inevitable!” Interview (Video) with Socrates a.k.a. Nikola Danaylov of the Singularity Weblog, October 29, 2013. https://www.singularityweblog.com/frank-j-tipler-the-singularity-is-inevitable.

- Torr, James D. 2002. The American Frontier. San Diego: Greenhaven.

- Trein, Lorenz. 2020. “Multiple Times of Disenchantment and Secularization.” In Narratives of Disenchantment and Secularization. Critiquing Max Weber’s Idea of Modernity, edited by Robert Yelle, and Lorenz Trein, 71–86. London: Bloomsbury.

- Tyrell, Hartmann. 1993. “Potenz und Depotenzierung der Religion – Religion und Rationalisierung bei Max Weber.” Saeculum 44: 300–347.

- Vinge, Vernor. 1983. “First Word.” Omni (January), 10.

- Vinge, Vernor. 1993. “The Coming Technological Singularity. How to Survive in the Post–Human Era.” http://mindstalk.net/vinge/vinge–sing.html.

- Vinge, Vernor. (2003) 2013. “Technological Singularity.” In The Transhumanist Reader, edited by Max More, and Natasha Vita-More, 365–375. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

- Weber, Alfred. (1935) 1951. Kulturgeschichte als Kultursoziologie. Piper: München.

- Weber, Max. (1904/05) 2005. The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, translated by Talcott Parsons. London: Routledge.

- Yudkowsky, Eliezer S. 2000. Singularitarian Principles. Version 1.0.2. Extended Edition. https://museum.netstalking.ru/cyberlib/lib/critica/sing/singprinc.html.