ABSTRACT

The core argument of this paper is that English-language scholarly understandings of socialism in Laos have been hampered by implicit ethnocentrism and denial of coevalness. Lingering but pervasive legacies of the Cold War include an equation of ‘true’ socialism with models of socialism that were practised in Europe, and a triumphalist tone that equates socialism with the past, the fake and the crumbling, even when it is (as with Laos) so evidently a tangible part of the lived present and the imagined future. Better understanding of socialism in Laos requires the kind of work that was done by an earlier generation of scholars on power in Southeast Asia, where concepts were translated across difference by rooting them in local terminology, contextualisations and usage. Following this inspiration, I approach socialism in Laos through the example of how the problem of water supply was addressed in a resettled, ethnic Kantu village in Sekong Province, Lao PDR. Why was the village resettled? Why was water a problem? What strategies did people use to obtain safe water? Answering these questions reveals some of what socialism means in lives as lived in this self-identified socialist state.

The Post-socialist Paradigm in Lao StudiesFootnote1

In a 1995 publication, Grant Evans dramatically announced ‘Socialism has come and gone in Laos. … Socialism in Laos lasted barely fifteen years. The roots it sunk were shallow and they were easily uprooted’ (Citation1995, xi). While he provided no evidence that the values and concepts of socialism had been repudiated by the ruling party (and indeed he gave evidence to the contrary), he felt confident enough to write, ‘No doubt history today is working behind the backs of the communist parties of Asia and we will finally see their downfall by the forces of capitalism they have unshackled’ (Citation1995, xiv). Three years later, Evans doubled-down on these dramatic statements: this, despite the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party, which had come to power in 1975 on the promise of creating a new society along Marxist-Leninist lines, remaining solidly in power. ‘We live in a new era’ he asserted (Evans Citation1998, 1). While still not able to point to any definitive evidence of an era-making break in Laos, he did point to the Soviet Union collapse. Citing his earlier publication (Evans Citation1995), he wrote, ‘“socialism” no longer represents an economic program, or a program of social and cultural transformation’ (Citation1998, 2). If socialism nevertheless continued to appear in the public discourse and imagery of the Lao state, he asserted that this was only as a cynical attempt to hold on to power through empty rhetoric.

This idea was so widely taken up and so hegemonic when I did my first fieldwork in a rural village in Laos 2002–2003 that I only asked about socialism in the past tense, especially in terms of memories of the collectivisation of agriculture. However, there was no sharp break evident in the replies people gave me. Yes, collectivisation had been short lived and phay het phay man (L: each to their own) rice production returned (to general relief, but not without some regret and nostalgia for the sheer fun of working together) (High Citation2005). But when people spoke to me of labop may (L: the new system), they clearly meant the socialist regime right up to the present day, not a ‘new’ system that came when socialism was relinquished. When they spoke about khaw or pheun (L: them), aay eauay (L: the brothers and the sisters) and phak lad (the Party State), it was obvious that they were speaking not only of the fervent cadre who had come to teach them collectivised agriculture in those early days, but also the people who remain in power today.

This went beyond the kind of continuity Evans intimated, where everything changed except the ruling party and their rhetoric, a rhetoric which according to him did change only by becoming more and more emptied out of any genuine socialist values. By contrast, what I saw was that the values and ethics of socialism were alive in day-to-day life. Not expecting to find myself in a socialist state, I was bewildered by the urgings to cooperate, act with solidarity, and help one’s ‘comrades’ that were ubiquitous in the daily life that I recorded. These were so repetitive that I could only conclude they were aimed at something more than practical outcomes (High Citation2006). This was all the more striking given the particular experiences of this particular village; on the continuum of political views in Laos, this village leans decidedly to the right. Sentiments seemed to lie generally more to the west, with relatives and work opportunities in Thailand, and a certain wistfulness that Laos was not more like Thailand, than with Vientiane, the Party or doctrinal socialism. Still, even in this village, collectivist impulses were so evident, troubled and compulsive that I ultimately wrote about them as a sort of ‘delirium’ (High Citation2014).

My PhD thesis took the form of an ethnographic critique of the concept of the village (High Citation2005). At the time, I was partly taking aim at a somewhat romantic notion of community floating around in Western stereotypes of the non-West (an angle also taken by Evans Citation1990). I showed that the village in Laos is actually an administrative body, constantly called into being through subtle or overt state pressure in what I eventually called ‘village formation processes’ (High Citation2006). I was trying to destabilise the idea of an enduring, pre-given village. But what I didn’t see at the time – blinded as I was by the post-socialist orthodoxy in the English-language literature – was that village formation processes are congruent with the ‘creative’ approach to socialism taken up by Laos and a key method of implanting socialism in the countryside (Phomvihane Citation1981). Because I was guided by an orthodoxy that held that Laos was post-socialist, I did not see my study for what it really was: a study of what socialism looks like from the vantage of a very sceptical, but still engaged, grassroots populace.

It is helpful to pause here and give a minimal definition of socialism. Newman (Citation2005, 18) warns against being either too pragmatic (equating socialism with whatever it is that self-proclaimed socialists do) or too dogmatic (insisting that one form of socialism is the true essence while all others are false). While acknowledging that many definitions of socialism do tend to one or both of these pitfalls, he argues that a minimal definition of socialism can act as a guideline for comparative discussions. He suggests four elements. First, socialists aim to create structural conditions that will enable equality. Second, they aim to do so through acts of ‘solidarity and cooperation’ (Citation2005, 18). Third, this faith in cooperation is based on a rather optimistic view of humans as prone to harmony, even unity. For some socialists, this results in the notion that humans are best when left to self-govern (and here there are affinities with communitarian anarchists). For others, hierarchical parties and states (a ‘vanguard’) are thought necessary to enable socialism (and here, socialisms can tend towards authoritarianism). However, socialists of all stripes have

always rejected views that stress individual self-interest and competition as the sole motivating factors of human behaviour in all societies at all times. The have regarded this perspective as the product of a particular kind of society, rather than an ineradicable fact about human beings. (Newman Citation2005, 19)

The term ‘postsocialism’ was popularised in anthropology after the dramatic end of socialist societies in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union (1989–1991). This entailed a rapid increase in the possibilities for ethnographic fieldwork in the region, and these scholars coalesced in the study of everyday life under conditions of massive change (Dunn, Rogers, and Verdery Citation2018). Elizabeth Dunn et al. clarify that the term ‘postsocialism’ is reserved for that analytical stance that examines the continuing relevance of the socialist experience for what comes after, while ‘post-socialism’ (the term ultimately adopted by Evans) is used for that stance that argues that socialism is irrelevant for current forms (2018). Since Evans’s early adoption of this term to describe Laos, it has remained popular among scholars. Sarinda Singh, for instance, calls Laos ‘post-socialist’ and echoes Evans when stating:

the commonly displayed flag of the Party – the yellow hammer and sickle crossed over a red background – seems more an assertion of the Party's authority over the Lao nation than a commitment to Communist doctrine. (Singh Citation2012, 6)

By contrast, some recent scholarship in Lao studies has moved away from the terms ‘postsocialist’ and ‘post-socialist’. In an article co-authored with Pierre Petit (High and Petit Citation2013), I suggested the term ‘pre-socialist’ instead, as a means of acknowledging that socialism persists as a goal in official pronouncements. Norihiko Yamada recently questioned the postsocialist paradigm by pointing out that the motto that Evans took to be a key indicator of the end of socalism, chitanakan mai (new thinking), was actually only a short-lived slogan calling for reform rather than a radical break (Citation2018). An earlier formulation of a similar position is presented by Bunsang Khamkeo, who with patience and directness, explained that it was only from ‘within a socialist framework’ that the ‘government has adopted a market-oriented economy and has opened the country to private enterprise and foreign trade’ (Citation2006, 420). An example of the continuing importance of a socialist framework is the motto of the 11th Central Party Committee, which was released in May 2021. The motto reads:

Raise high the leadership ability of the Party, increase unity and solidarity of the people in the nation, surely guarantee stability on the political front, disseminate and expand the new path of change profoundly, build transformations in socio-economic development towards new qualities that are strong, raise the living standards of people, continue to guide the nation out of underdevelopment and advance towards the goal of socialism! (Own Translation)

While it is common for ‘postsocialist’ literature to assert that the Cold War is now over, it demonstrably lingers on in the kinds of things I have described above: the way socialism is described, the emotions the very word stirs, the way overt claims made by socialist regimes – about solidarity, unity and equality, for instance – are so cynically, summarily and routinely dismissed, and the way the word is taken to be tantamount to authoritarianism. Writing about architecture in Poland, Michał Murawski offers a compelling critique of such over-determinations, ingrained discursive forms, and outright errors, arguing that they are introduced to scholarly literature by ‘a remarkably persistent remnant of a Cold War-rooted ideology, which cast socialist modernity as a perverted version of modernity proper, failure-bound from the beginning’ (Citation2018, 909). He argues that ‘failure-centrism’ pervades literature on the built socialisms he studies, which is a puzzle given that many buildings and public spaces created by socialist regimes in fact continue to be cherished by users (Citation2018). He describes a Stalinist skyscraper, a ‘Palace of Culture’ built in Warsaw, that continues to be used by most citizens and successfully serve socialist ends, even when surrounded by the poverty and gentrification produced by more recent capitalism (Citation2020).

Thinking in terms inspired by Murawski, it is possible to see that English-language Lao studies literature does tend towards a failure-centrism in discussions of socialism. My own efforts notwithstanding, there is rarely any mention of socialism’s successes, or the appeal and sincerity that accompany many of the values propagated under socialism, much less a consideration of socialism as a possible future in Laos or indeed for the rest of the world, let alone – heaven forbid – a suggestion that we could learn from Lao socialism instead of just about it as a distant and receding object.

As an anthropologist, I find this problematic for two main reasons. First, there is a potent denial of coevality implied in casting socialism always in the past tense. Johannes Fabian (Citation1983) influentially argued that early evolutionary and colonial era anthropology had cast the object of anthropological enquiry into the past as a means of putting distance, even if only figuratively, between the observer and the observed. The closed culture gardens of relativism and static models of structuralism, too, he interpreted as essentially emotionally motivated defences that create a reassuring, but false, sense of distance between researcher and subject. The problem with such studies is that the distance thus produced is merely a projection. Furthermore, this defence diminishes the conditions for true intersubjectivity, and thus transformative learning and effective fieldwork.

Second, it is ethnocentric. Ethnocentrism, according to Tzvetan Todorov, is ‘the unwarranted establishing of the specific values of one’s own society as universal values’ (1993, 1, cited in Falen Citation2020). Grant Evans (Citation1995), in his original argument that Laos did not meet any of the criteria for being classified as a socialist state based his arguments entirely on economic considerations. However, even a cursory glance at Lao socialist writings, such as the oeuvre of Kaysone Phomvihane, reveals that socialism was never proposed as a purely economic platform. While Evans does seem to recognise this in, for instance, his mention of the socialist ambition of ‘changing people’s heads’ (Evans Citation1995, 1), when economic reforms were introduced, he chose, dramatically, to see policy change in the economic sector as the end of socialism. A more plausible interpretation, and the one that is evident in official Lao publications on the topic, is that market reforms were introduced within a socialist framework, as yet another adaptation of socialism ‘correctly and creatively’ to the unique conditions presented in Laos (Phomvihane Citation1981, 10).

Although I acknowledge that both a denial of coevality and ethnocentrism typically evoke moral repugnance in anthropologists, at least in the English-speaking world (High Citation2021, see also Falen Citation2020), such moralism is not the intention behind the argument made here. Rather, my intention is to draw attention to the fact that both these stances are methodologically problematic. Fabian (Citation1983, 42) argues that coevality is a precondition for communication: without it, ethnographic intersubjectivity is simply an impossibility. Likewise, recognising and critiquing one’s own ethnocentrisms is an important element of any genuinely ethnographic encounter. Ideally, the ethnographer should produce at least two sets of data: one about the people she is studying, and the other about her own implicit values that have been revealed in the (often-jarring) process of fieldwork (Devereux Citation1967; Davies and Spencer Citation2010). This is not to suggest an unmoored relativism, but rather a clear-eyed view of what ethnographic fieldwork entails: one needs an ability to recognise, if only momentarily, one’s own presuppositions and how these differ from those held by others.

Among the many examples that demonstrate the effectiveness of such methods not only for enabling us to better understand others, but also to better understand ourselves and imagine yet other possibilities, stand the now-classic analyses of power in Southeast Asia returned to in this special issue. For instance, Benedict Anderson (Citation1990) offered a systemic analysis of traditional Javanese concepts of power as a means, in part, of showing how the assumptions made in political science about the nature of power could not be taken as universals. Rather, political science orthodoxy at best forms only one ‘lens’ among many for viewing a political landscape.Footnote2 Likewise, Lucien Hanks's delineation of Thai concepts of efficacy and power, rooted firmly in local terminology and examples from everyday life, drew on a comparison with and differentiation from assumptions he astutely anticipated his readers might bring to the text, such as those about personhood (Hanks Citation1962). In contrast to liberal concepts of the person as ideally a stable and authentic identity (‘to thine own self be true’), Hanks describes much more fluid and transient social roles built on an understanding of the self as impermanent and as passing through different positions in hierarchy and merit that ‘transform the person’ (Hanks Citation1962, 1252).

While these texts might be read today as inexcusably generalising and ‘Othering’ of the Javanese and the Thai, I prefer to read them like inspiring pieces of science fiction. What if power were conceived of as a material, limited, homogenous across contexts and antecedent of questions of good and evil? What if something so taken-for-granted as the individual self could not be taken-for-granted after all? What would politics, economy, and family look like if these essential pieces of the puzzle were shaped so differently? These classic texts are invitations to the imagination. Hanks and Anderson offered portraits that somehow continue to ring true, even after all these years, and even after so much change in the region. And these portraits can also act as portals, offering a way for readers to begin to doubt their own basic presuppositions about the nature of the world. As David Graeber (Citation2007) has so eloquently argued, anthropology at its best opens up possibilities. One of my concerns with the postsocialist paradigm in Lao studies is that it forecloses possibilities. One is more likely to come away from these texts feeling that socialism had indeed been a deluded and dangerous failure from the start (confirmed! We knew it all along!) than to come away feeling the ground of one’s orientation to the world had subtly shifted.

Lao Socialism: A Creative Endeavour

What would an analysis of Lao socialism inspired by the classic ethnographic approaches of Hanks and Anderson look like? Minimally, it would require analysis of how socialism has become part of an open-ended and not always coherent ‘patchwork of borrowings’ (O’Connor Citation2022, this issue), as expressed in local terminology, common usage and everyday life. In short, it would require ethnography. In a curious and convoluted recent argument, Simon Creak and Keith Barney have exclaimed that ‘it is ironic that in Laos itself recent years have seen many more anthropologists considering questions of politics and power than political scientists’ (Creak and Barney Citation2018, 704). They pick a quarrel with the dominance of anthropology in this arena. First, they say, ethnographic studies are necessarily rooted in specific times and places (what they call the ‘local-level’ rather than ‘the centre’). Second, they assert that anthropological work has generated ‘an impression that authoritarian power is manifested primarily at the local level’ (they do not specify who holds this impression) (Creak and Barney Citation2018, 704). Observing wistfully that ‘Laos has rarely (if ever) been used as an empirical basis for understanding comparative politics’ (Citation2018, 694), they hanker after something more general, more central, more … masculinized in outlook. It was an early insight of feminist interventions into science (including social science) that under patriarchy ‘the male way of thinking is said to be rational, impersonal, and objective, while the female way of thinking is said to be emotional, personal and subjective’ (Fee Citation1981, 84). As science itself was thought of as a rightly masculine endeavour, this split hampered twentieth century thought on many levels, including by fostering a sense that any study that deals with emotion, meaning or subjective views offers by default a lesser kind of knowledge than ‘true’ science. Writing of the scholarship of Laos, for example, Roy Huijsmans (Citation2018) has observed that, despite recent influential calls for attention to the very real ways that emotions influence policy, research on this has been impaired due to a ‘“gender politics of research” in which “detachment, objectivity and rationality” are valued and implicitly masculinised while “engagement, subjectivity, passion and desire” are frequently feminised and seen as clouding vision and impairing judgement’ (Huijsmans Citation2018, 629, citing Anderson and Smith 2001). In my reading, a similar gender politics of research can be discerned in Creak and Barney’s decrying of the prominence of anthropology in the analysis of politics in Laos to date, which they associate in a quite unfounded way with analysis that is ‘local’, anomalous, specific, and limited in scope: all tropes identified with the feminine and denigrated in patriarchal approaches to science.

It is important to emphasise that it is inaccurate to suggest that anthropology is limited in focus to the ‘local level’ in the sense that Creak and Barney use the term ‘local’ (that is, as the opposite of ‘central’). My above summary of the post-socialist paradigm in Lao studies confirms that anthropologists are indeed dominant in this field. The prominence of anthropologists (and, in many cases, women anthropologists to boot!) in leading this debate is not an ‘anomaly’, as Creak and Barney suggest (Citation2018, 704). Rather, it is a consequence of the efficacy and importance of our method. While I have critiqued the paradigm of post-socialism in Laos, this is offered as part of my acknowledgement of and contribution to a lively debate in which anthropologists have made significant contributions to understanding not only day-to-day life in out-of-the-way places in Laos, but also to the understanding of broad and overarching political values and concepts motivating politics in that country. To name but a few highlights, Grant Evans’s (Citation1990) attention to the concept of the ‘natural economy’, Sarinda Singh’s account of forests and local concepts of ‘potency’ (Citation2012), Leah Zani’s attention to parallelisms in rhetoric (Citation2019), and my own attention to the compulsive return to the concept of ‘mutual aid’ as it ramifies across multiple scales in Lao political culture (High Citation2014). Indeed, it is attention to values and concepts that is most glaringly absent from Creak and Barney’s analysis of Lao politics: they only mention values twice, both times in summary of others’ work, and they only use ‘concepts’ in the sense of academic concepts that might be applied to studies about Lao politics, rather than Lao political concepts. Their main argument is that more scholarly attention needs to be paid to structural elements like ‘the party-state system’ and ‘administrative-bureaucratic capacity’ (Citation2018, 699, 700). While these are worthy topics for consideration, understanding them will not get far without taking local political concepts and values seriously.

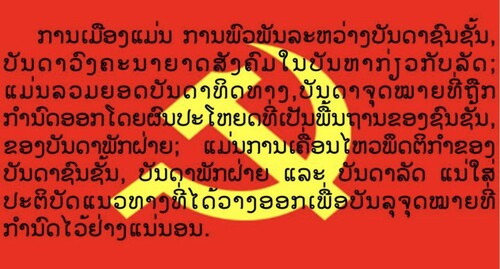

One approach to identifying influential political concepts and values, an approach used by Anderson (Citation1990) and Hanks (Citation1962) but also many others, is careful readings of local language sources. In Lao studies, important contributions along these lines have been made by historians Vatthana Pholsena (Citation2006) on the revolutionary’s concept of ‘entering the people’, Olivier Tappe (Citation2013) on the importance on the concept of ‘struggle’, and Bruce Lockhart on the narrative of a ‘heroic nation fighting to preserve its independence and unity’ (Citation2006, 372). In Fields of Desire (High Citation2014) I analysed several policy documents as well as a public seminar presented in response to a reactionary border incursion, and in Projectland (Citation2021) I again analysed policy documents as well as a book-length history of Sekong Province. To give a further example of the value of this kind of work and the kinds of questions it raises, below I offer a much shorter example: a meme that was circulated on Facebook in 2020 () in a series titled ‘What is Politics?’ Overlaid across the LPRP’s flag, the text reads:

Politics is relationships between the various social classes and social circles regarding the questions of State. It includes balancing various directions and goals, determined in such a way as to create beneficial results on the basis of the social classes of the various parties. It is shifting activities among various classes, parties, and states, surely realizing the directions laid down, in order to successfully attain the set objectives quickly and surely. (Own translation)

This meme was shared by a man I know in Sekong Province: a smallholder in his thirties, married with two children, he grows food for his household and makes some money by hiring out agricultural equipment. His promotion of this and other socialist-inspired memes on social media suggests that politics in Laos is still conceptualised, at least in some quarters, in Marxist-Leninist terms. A key concept deployed in this meme is social class, reflecting the particular conceptualisation of society animating the Leninism that the LPRP adopted. The emphasis on striking a balance between competing goals echoes Kaysone Phomvihane’s characterisation of socialism in Laos as by necessity both ‘creative’ and ‘correct’, always adapting to the demands of the local conditions but also firmly under the guidance of the vanguard who reserve the right to determine the overall goals. The final sentence suggests that politics is not only about relationships, but about ‘shifting’ these: an example of the optimism often held by socialists in the possibilities for transforming people and their social conditions. Stepping back from the individual words used, there is also the overall impression of this meme: despite the apparent intention to explain once and for all what politics really is, the meme in fact comes across as a dry, almost incomprehensible, string of platitudes that is arguably more likely to shut readers out than draw them in. I have argued elsewhere that this is a characteristic of Lao vanguardism: socialism often appears in Laos as an aspirational doctrine. Entering and then advancing in the party requires the aspirant to engage in continual self-criticism and improvement, as well as intensive education that allows her to become fluent in a doctrinal language that is otherwise quite alienating. Vanguardism thus creates this sense of being inside and/or outside the knowing group (High Citation2021).

This small example illustrates the importance of Lao-language documents for any English-language analysis of politics in Laos (N.B. Creak and Barney (Citation2018) make no use of Lao language documents in their article, and the only Lao scholars cited are those included in pieces co-authored with foreign researchers). This example also demonstrates the fact that reading local sources alone cannot substitute for ethnography. Based on examples like the above, it is too easy to insinuate, or even boldly argue, that if socialism indeed persists in Laos, it is on paper only and does not touch how things ‘really happen’ in daily life. Indeed, such an argument has been common in postsocialist studies of Laos to date. But this reasoning is unsatisfactory. If rhetoric like this meme serves to shore up the legitimacy of the ruling party, then it must have appeal. Speaking personally, I can’t imagine many in Australia would find this meme appealing, even with the English translation. Why does a meme like this have any appeal in Laos? Who is it appealing to? And how? What wider values or concepts does it tap into? Sustained ethnographic fieldwork and writing is the best, and perhaps only, method for answering fundamental questions like these. Ethnography can show how values and concepts connect with how things ‘really happen’.

Living Socialism

In addition to local language documents, political concepts and values can also be effectively illuminated through attention to the way they are used, either implicitly or explicitly, in the work and chatter of daily life. Below, I will provide a short example drawn from my ethnographic fieldwork, which took place in an ethnic KantuFootnote3 village of about 1,000 people in Sekong Province for a total of 12 months between 2009 and 2018. Originally inhabiting lands at the headwaters of the Sekong River in Kalerm District, the village relocated to an area in the foothills of the Bolaven Plateau, Tha Teeng District, in 1997.

When I first arrived in the village, a common sight was women and girls fetching water from water pumps at various sites in the village. Working the pumps’ giant arms, they would splash water into old petrol caddies, blue tinted water cooler bottles, or buckets, which were then hewed on bamboo poles balanced over the shoulder. Bathing in those days involved crouching at a water pump and coyly splashing water over myself while wrapped in a cloth and surrounded by dozens of curious onlookers. I heard that this was an improvement: when they had first arrived from the mountains, villagers had drunk water from the local river (the Sedon), boiled. Anthropologist Futoshi Nishimoto (Citation2010), who was present in Kandon for the first three years after the resettlement in 1997, reports that the settlement was plagued by cholera due to contaminated water supply.

By the time I finished my fieldwork in 2018, the sight of girls and women carting water in the village was no longer common. Instead, water was piped to each house: in my case it came through thin blue PVC tubes. One faucet discharged in my kitchen and the other in an outdoor, fenced area where I could bathe in more privacy. I tested the water for lead, and found alarming levels in my own water supply. I had to conclude that this was from the blue pipes because none of the other tests (I tested a selection of household outlets and each of the reservoirs) indicated lead. My tests showed, instead, that most people in Kandon were enjoying safe water piped to their houses.

This relative success had been achieved only after multiple failures and disappointments. I heard about these frequently from the Village Chief, Wiphat Sengmany. He told me how the Sekong Province Rural Development Fund had tried, but failed, three times to strike a groundwater bore for the settlers. Then, in 1999, Vientiane Red Cross sponsored a pipe connecting the village to a natural spring near Palay (a neighbouring village). In 2006, a Vietnamese rubber company was given a concession of 208 acres of Kandon land and an even greater area of Palay. In establishing this plantation, workers broke the pipe. The company determined that it would not be suitable to have a pipe running through the plantation, anyway. Villagers, too, were concerned that the chemicals used on the plantation would contaminate what had been pure spring water. Therefore, Kandon villagers sanoe (L: put in an application) to the Sekong Health Office, who responded by installing a water pipe from a spring near another village, Cakam. This water was filtered first through a tank of sand and pebbles before being piped to a reservoir, and from there to the six hand pumps in the village. This was the system that I saw in operation during my earliest field trips to this village and that watered the village from 2008 to 2012.

However, intensification of land use in the area led villagers to be concerned, again, about contamination of their water supply from the chemicals used in agricultural production. The villagers again prepared a sanoe to the Sekong Health Office and were offered a bore powered by an electric pump. This bore was successful in striking groundwater, but there was not enough to supply all the handpumps in the village, leaving some parts of the village to receive water only at 11pm or so at night. And, to make matters worse, the electricity needed to run the bore cost the village 7–8 million kip a month (900–1120 AUD). In 2014, the village again lodged an application to the Sekong Health Office. The response was a second groundwater pump. This, too, ran on electricity. There was now plenty of water for the whole village, but the electricity bill climbed to 9–10 million kip (1120–1243 AUD) a month. Many households could not pay their share, and the village was forced to draw on its Village Development Fund.

In 2016, the village determined that they would take the water issue into their own hands. A water committee was formed, and each head of a household committed to contribute 50,000 kip (6 AUD) and seven days of labour. Water rising from a natural spring close to the village was channelled into a concrete tank filled with charcoal, sand and pebbles that would filter the water before piping it to a reservoir tank in the village. From there the water was piped to each of the houses in the lower end of the village. In 2017, the committee arranged a second spring water reservoir, which was piped to the remaining houses. The village purchased the land containing this second spring from Cakam via a second contribution of 500,000 (6 AUD) per household. Apart from the few extra pipes required to reach this spring, this construction mainly used existing infrastructure, including piping and a reservoir tank from the electric pump groundwater episode. This new spring water source required some electricity to pump to the reservoir, but much less than drawing the water from underground. The two springs also require regular maintenance. This is carried out by village labour requisitioned and organised each year by a village-level water committee. In the dry season, a work team digs out sediment, pumps out accrued water, and replaces the stones at the base, covering these liberally with charcoal, which is then weighed down with a rubber sheet. Rocks and pebbles scattered on the sheet down hold it down while allowing the water to rise up through the charcoal, filtering as it rises.

The water committee is composed of three volunteers, all men aged in their 30s. When I lived in the village in 2018, one came to my house monthly to issue my water bill. The revenues raised from monthly user fees were used to buy consumables required to maintain the water infrastructure. In addition, each household was required to donate labour for maintenance. Those that could not supply labour were given the option to instead pay a fee. During the initial set-up, households were not connected to the water supply until they had paid and donated labour. Wiphat, the Village Chief, acknowledged that, initially, many people had considered holding back to see if the spring water plan would work before joining the group: evidently their village-level ‘solidarity’ could not be taken for granted. Those who did not contribute to the initial set up were only able to join at a later point by paying a considerably inflated fee of 2,000,000 kip (248 AUD): four families joined the scheme in this way.

In summarising this series of events for me, the Village Chief said, ‘First the water was from the government, then the water was from the Province, and third was from the health office, and the fourth was from ourselves!’ And the solution that worked, ultimately, was the solution the people themselves had initiated, carried out and maintained. ‘Bo pen lathabaan het, het eng’ (L: It was not the government that did it, it was us!), he said, smiling broadly.Footnote4

Water in Kandon

If one wants to know how things ‘really happen’, then it does not get much more real than the question of how people access potable water. The shortest answer as to how Kandon villagers eventually established a secure supply of drinking water is that they did so by self-organising so that each household had adequate access to water and broadly equal responsibilities for maintaining the infrastructure. The Lao words used for these activities and moral reasonings about infrastructure were in line with Marxist-Leninism: solidarity, equality, and unity. Even the ‘try and try again’ approach evident in the villager’s multiple efforts to secure clean water (and the way these were so proudly repeated to me by the Village Chief) can be understood in terms of socialist principles: Phomvihane argued long ago that Marxist-Leninism needed to be ‘creative and correct’ in its striving to find appropriate applications in the unique conditions presented by Laos (e.g. 1981). He did not envisage a one-size-fits-all approach to development, but rather a continuous process of experimentation based on critical reflection and revision. While the ‘democratic centralism’ enshrined in the Lao constitution has been associated with authoritarianism and lack of freedom of speech by foreign scholars, it has also been described to me by Lao citizens as the aspiration to include as many voices as possible in decision-making. This often manifests in the policy realm in a kind of recursiveness (what I have called elsewhere an ‘experimental consensus’ (High Citation2013)) where development efforts are implemented, but at the same time critiqued and revised in light of results on the ground. I have come to understand this as a feature of Lao socialism. Lao socialism foregrounds a modernist commitment to change, science and technology. It values subjects who are informed, educated and agentive, and who are engaged in projects aimed at deliberately altering the world (often glossed in Phomvihane’s writing as being ‘cultured’). Such a subject was envisioned as a new kind of individual, in a break with the stagnant ‘natural economy’ of the peasantry.

The resettlement of Kandon village itself, which triggered the water crisis described here, can also be read in terms of the salience of socialist-informed values and concepts in lives as lived in Laos. Wiphat said that, when the village was in the highlands and requesting help from the government to develop, the District Chief had replied ‘If you stay in the mountains, we cannot help you.’ In 1993, the District Chief personally hiked to Kandon village (at that time, a three-day walk) to speak directly with the villagers about the central government’s resettlement support schemes. According to Wiphat, the council of elders that led the village at that time were not interested in the District Chief’s offer: ‘They said, “We have always lived here, and we are fine – there are people here who are eighty years old. We know how to live here.” They were not worried about the children's future, they thought only of themselves.' Disturbed by this response, it was Wiphat who secretly wrote to the District Chief. Wiphat’s letter reportedly said, ‘We are poor, we are short of food, so … I suggest you organise a resettlement for us. We want a flat area – in a plateau or valley. We don’t want to live in this place anymore.’ The District Chief sent this request to the central government. Almost a year later, Wiphat received news that his request had been approved. There is evidence in Wiphat’s self-presentation here of the kind of commitment to ambitious projects aimed at creating a new society that Newman identifies in his minimal definition of socialism (acknowledging this characteristic is shared with many other modernist ideologies). Radical modernist change was framed as a means of his confronting what were perceived as the structural causes of inequality and also the stagnation of traditional ways of thinking and older generations.

The state contributed to the material needs of the villagers during the first and most difficult year of the resettlement. Wiphat meticulously kept a record: 92,042 tons of rice; 2571 sheets of iron; 400 nails; 441 pounds of rice seed; one ploughing machine; 381 machetes; 254 hoes; 254 shovels; 2996 yards of cloth; 254 blankets; 254 mosquito nets; and 765 items of used clothing. This assistance left much for the villagers to do on their own, including, in the end, establishing a stable, safe and sufficient water supply. This echoes a nuance that Phomvihane identified: that just as the state needed to avoid overreach by lapsing into authoritarianism, so too the people should retain a sense of responsibility while investing and trusting in the collective:

Any signs of authoritarianism, abuse of power, cult of the personality, or lack of respect for the collective must be suppressed, while any tendency to shift all responsibility onto the collective, evade responsibility or deny the necessity to take decisions on matters within one’s own jurisdiction must be firmly countered. (Citation1981, 242)

In explaining some of the difficulties first encountered on resettling, Wiphat once told me that his people, in the past and in the mountains, had drunk only pure mountain water, so he was not surprised when people fell ill upon moving to these comparatively crowded foothills (High Citation2021, Chapter Two). Despite the severity of the illnesses and deaths that resulted from bad water (such as those mentioned by Nishimoto, and also reported by other villagers, see High Citation2022, this issue). Wiphat seemed bent on emphasising the considerable success the village had had in terms of ultimately supplying its own water supply. In his telling, it seemed that the villagers had met challenge after challenge but, ultimately, had devised and implemented a solution of their own that truly worked. In short, the Wiphat seemed proud.

The bones of the story of Kandon’s water – that a poor and remote people who had formerly relied on pure mountain water now had to provide their own supply, after cholera and pollution had poisoned their previous sources – could be perceived as adding up to quite a miserable, even tragic, series of events. They would certainly appear so if interpreted through a storyline of a lost remote isolation and domination in a state-nonstate binary (the storyline critiqued by Hjorleifur Jonsson in this issue). Importantly, Wiphat did not adopt that storyline. Rather, his presentation on this topic, which he raised with me often, emphasised a kind of mutualism between the state and the local. Both shared a common interest: resettlement for the betterment of future generations, and securing a clean water supply once there. The villagers had sanoe (L: requested, petitioned) government authorities repeatedly for a water supply, indicating a hierarchical relationship based on an apparently assumed social contract between authorities and locals. Wiphat presented himself and the village as agentive and canny in this hierarchical relationship: they followed government policy, but not passively. His story depicted desired change as brought about via grit, inventiveness, judicious appeals to outside authorities and, ultimately, the successful achievement of unity of purpose and cooperation among villagers themselves. In sum, attention to how Wiphat discussed the water supply in Kandon reveals a permeation of some quite classic socialist ideals to the pragmatics of daily life in rural Laos. More specifically, it reveals that socialist concepts form an important part of the ‘game’ of politics as played in Laos, and that Wiphat was presenting himself as a skilful player in that game.

Graeber has argued that:

political action is action meant to influence others who are not physically present when the action is being done … it is action that is meant to be recounted, narrated, or in some other way represented to other people afterward; or anyway, it is political in so far as it is. (Graeber Citation2007, 130; see also Graeber Citation2015, 103)

This was only one kind of political story circulating in Kandon. I also heard stories about the ‘necessities’ that meant people very often could not or would not adhere to socialist ideals, even from Wiphat himself. Projectland: Life in a Lao Socialist Model Village (Citation2021) gives substantial attention to these as well as women’s stories. Here, I have focussed on Wiphat’s story of the water because it is a suitable example for demonstrating one of my main critiques of how socialism has hitherto been discussed under the postsocialist paradigm in Lao studies. Kandon’s water supply, and the stories of success that were told about it, show that socialism is not just a lofty rhetoric that only serves to confirm LPRP power. It is not just empty words that are totally disconnected from how things ‘really happen’. Even the most practical of concerns in a rural village can be perceived, responded to and talked about through the prism of socialist concepts and values.

Conclusion

Granted, Kandon is no ordinary village. It is a model village, frequently used as an example to others of how to enact various policy directives (High Citation2021). I have argued elsewhere that this use of models and exemplars is yet another example of the ongoing influence of Lao socialism. As I completed my fieldwork, there was talk of converting Kandon into a regional hub under the Saam Sang (Three Builds) Strategy, in which case the village would host health, education, banking and administrative services for it and surrounding villages, including Palay and Cakam. In discussing this with me, the man who would eventually post the meme mentioned above proudly described the selection of Kandon under ‘Three Builds’ as yet more evidence of the village’s unique ‘strength’ compared to its neighbours. While Kandon is indeed strong in its local context, this ought not be exaggerated. In every Province of Laos, villages are being selected for ‘Three Builds’ upgrades. This is a national policy. Kandon is not a wild exception in Laos. It is representative of Laos more generally not by being average but by inhabiting a certain story of success, a success that is supposed to be open to and aspirational for any village. This story of success only makes sense if one is aware of the continued influence that socialist ideology has in the values and concepts deployed in everyday political action in Laos.

In Projectland (Citation2021), I argued that socialism remains an important part of ‘the politics of culture and the culture of politics’ in Laos (High Citation2021). There, I detailed the politics of culture (such as official definitions of culture, cultural policies, and the legacy of Engels, Marx and Leninist thinking in contemporary Lao approaches to culture). In this article, I have focused on the other side of the chiasma, the culture of politics. I have argued that socialism is a doctrine based on an optimistic view about the human capacity for solidarity and cooperation, and a commitment to conscious attempts at root and branch transformation, even revolution, typically of a kind that aims to reduce inequality. I have argued that Lao socialism is a ‘patchwork’ constructed from multiple sources, including local influences, which now operates as an important political idiom, particularly when framing stories of success. I have argued that socialism is an important part of Lao political culture, where culture is understood in Lowie’s terms: as one possible set patched together from among the ‘social potentialities’ that all people share (Lowie Citation1920, 33) (see Jonsson Citation2022a,Citationb) (this issue).

Influencing stories – how they are framed, who talks about them, who listens – is one possible definition of political action. It is only in lived experience that the grand pronouncements of doctrine, policy or academic concepts find traction (or do not). My observations of lived experience in Kandon suggested a palpable pride was taken by people such as Wiphat and the man who posted the meme: it was a pride found in identifying their village as a success story told in the idiom of Lao socialism (High Citation2021). This contrasts with my first field site, an ethnic Lao village, where observations of daily life revealed a disgruntled resignation to the rule of a Party-State neither liked nor trusted, but which nonetheless was able to capture people’s hopes and aspirations to a remarkable degree (High Citation2014). A common thread between these villages, villages that contrast in so many other ways, is the permeation of socialist ideals into the values and concepts deployed in everyday life. This evidence, coupled with the continued rule of the LPRP, has convinced me that the paradigm of ‘post-socialism’ in Lao studies obscures more than it reveals about contemporary Lao politics. Rather than imposing exonyms like this, what is needed is continued and heightened attention to the concepts and values animating politics as lived in Laos. Drawing on a long tradition of studies of power in Southeast Asia, ethnographers and anthropologists are particularly well-equipped to continue to provide such leadership in the study of Lao politics.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 This research was supported by an Australian Research Council Discovery Early Career Research Award DE120100503.

2 In a later piece of writing, however, it appears that Anderson, too, had embraced the view that Asian socialisms were somehow not real. He wrote:

To be sure, ‘communist’ regimes and political parties still exist in Asia: China, the Korean peninsula, Japan, the Philippines, Vietnam, Laos, India, and Nepal, but they speak a frozen language that has little bearing on their policies. Everywhere one sees nationalism trumping socialism. (Anderson Citation2014, 96)

3 The ethnicity of the village is discussed in more detail in High (Citation2021, Chapter Two).

4 Further ethnographic detail of Kandon Village can be found in a full-length ethnography of the village, Projectland (High Citation2021).

References

- Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 1990. Language and Power: Exploring Political Cultures in Indonesia. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Anderson, Benedict R. O’G. 2014. Exploration and Irony in Studies of Siam Over Forty Years. Ithaca, NY: Cornell Southeast Asia Program.

- Baird, Ian G. 2018. “Party, State and the Control of Information in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic: Secrecy, Falsification and Denial.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (5): 739–760.

- Bouté, Vanina, and Vatthana Pholsena. 2017. Changing Lives in Laos: Society, Politics, and Culture in a Post-Socialist State. Singapore: NUS Press.

- Cohen, Paul T. 2013. “Symbolic Dimensions of the Anti-Opium Campaign in Laos.” The Australian Journal of Anthropology 24: 177–192.

- Creak, Simon, and Keith Barney. 2018. “Conceptualising Party-State Governance and Rule in Laos.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (5): 693–716.

- Davies, James, and Dimitrina Spencer. 2010. Emotions in the Field: The Anthropology of Fieldwork Experience. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

- Devereux, George. 1967. From Anxiety to Method in the Behavioral Sciences. Vol. 3, New Babylon Studies in the Behavioral Sciences. The Hague: Mouton & Co.

- Dunn, Elizabeth Cullen, Douglas Rogers, and Katherine Verdery. 2018. “Postsocialism.” In The International Encyclopedia of Anthropology, edited by Hilary Callan, 1p. London: Wiley.

- Evans, Grant. 1990. Lao Peasants Under Socialism. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Evans, Grant. 1995. Lao Peasants Under Socialism and Post-Socialism. Chaingmai, Thailand: Silkworm Press.

- Evans, Grant. 1998. The Politics of Ritual and Remembrance: Laos since 1975. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Fabian, Johannes. 1983. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes its Object. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Falen, Douglas. 2020. “Introduction: Facing the Other.” Anthropological Forum 30 (4): 321–340.

- Fee, Elizabeth. 1981. “Is Feminism a Threat to Scientific Objectivity?” Journal of College Science Teaching 11 (2): 84–92.

- Graeber, David. 2007. Lost People: Magic and the Legacy of Slavery in Madagascar. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Graeber, David. 2007. Possibilities: Essays on Hierarchy, Rebellion, and Desire. Oakland: AK Press.

- Graeber, David. 2015. The Utopia of Rules: On Technology, Stupidity, and the Secret Joys of Bureaucracy. Brooklyn: Melville House.

- Hanks, Lucien. 1962. “Merit and Power in the Thai Social Order.” American Anthropologist 64 (6): 1247–1261.

- High, Holly. 2005. “Village in Laos: An Ethnographic Account of Poverty and Policy among the Mekong's Flows.” PhD thesis, Department of Anthropology, Australian National University.

- High, Holly. 2006. “‘Join Together, Work Together, for the Common Good – Solidarity’: Village Formation Processes in the Rural South of Laos.” Sojourn (Singapore) 21 (1): 22–45.

- High, Holly. 2013. “Experimental Consensus: Negotiating with the Irrigating State in the South of Laos.” Asian Studies Review 37 (4): 491–508.

- High, Holly. 2014. Fields of Desire: Poverty and Policy in Laos. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

- High, Holly. 2021. Projectland: Life in a Lao Socialist Model Village. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press.

- High, Holly. 2022. “Living with New Gods: Power Encounters in Sekong Province, Lao PDR.” In Stone Masters: Power Encounters in Mainland Southeast Asia, edited by Holly High, 49–74. Singapore: National University of Singapore Press.

- High, Holly, and Pierre Petit. 2013. “Introduction: The Study of the State in Laos.” Asian Studies Review 37 (4): 417–432.

- Huijsmans, R. 2018. “‘Knowledge That Moves’: Emotions and Affect in Policy and Research with Young Migrants.” Children’s Geographies 16 (6): 628–641.

- Jonsson, Hjorleifur. 2022a. “Introduction: Revisiting Ideas of Power in Southeast Asia.” Anthropological Forum.

- Jonsson, Hjorleifur. 2022b. “Losing the Remote: Hybrid Identities in the Thai Social Order.” Anthropological Forum.

- Khamkeo, Bunsang. 2006. I Little Slave: A Prison Memoir from Communist Laos. Washington, DC: Eastern Washington University Press.

- Lockhart, Bruce. 2006. “Pavatsat Lao: Constructing a National History.” South East Asia Research 14 (3): 361–386.

- Lowie, Robert Harry. 1920. Primitive Society. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Murawski, Michał. 2018. “Actually-existing Success: Economics, Aesthetics, and the Specificity of (Still-)Socialist Urbanism.” Comparative Studies in Society and History 60 (4): 907–937.

- Murawski, Michał. 2020. “Palatial Socialism, or (Still-)Socialist Centrality in Warsaw.” In Re-Centring the City, edited by Jonathan Bach and Michał Murawski, 104–113. London: UCL Press.

- Newman, Michael. 2005. Socialism: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nishimoto, Futoshi. 2010b. “The Spirit of the Salt-Licking Swamp: How the Laos Mountain People Who Migrated to the Flatlands Interacted with Water [Shioname sawa no seirei: heichi ni ijuushita raosu sanchiminzoku no mizu to no tsukiaikata].” In People and Water 3: Water and Culture (Hito to mizu 3: mizu to bunka), edited by Tomoya Akimichi, Kazuhiko Komatsu, and Yasuo Nakamura, 167–196. Tokyo: Bensei Shuppan.

- O’Connor, R. A. 2022. “Revisiting Power in a Southeast Asian Landscape — Discussant’s Comments.” Anthropological Forum 32 (1): 95–107.

- Pholsena, Vatthana. 2006. “The Early Years of the Lao Revolution (1945-49): Between History, Myth and Experience.” South East Asia Research 14 (3): 403–430.

- Phomvihane, Kaysone. 1976. “Political Report Presented by Mr Kaysone Phomvihanah at the National Congress of the People's Representative in Laos.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 6 (1): 110–119.

- Phomvihane, Kaysone. 1977. “The Victory of Creative Marxism-Leninism in Laos.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 7 (3): 393–401.

- Phomvihane, Kaysone. 1978. “Report on Present Conditions in Laos.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 8 (2): 285–297.

- Phomvihane, Kaysone. 1981. Revolution in Laos: Practice and Prospects. Moscow: Progress Publishers.

- Sahlins, Marshall D., and David Graeber. 2017. On Kings. Chicago: HAU Books.

- Singh, Sarinda. 2012. Natural Potency and Political Power: Forests and State Authority in Contemporary Laos. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press.

- Spiro, Melford E. 1966. “Buddhism and Economic Action in Burma.” American Anthropologist 68 (5): 1163–1173.

- Spiro, Melford E. 1982. Buddhism and Society: A Great Tradition and Its Burmese Vicissitudes. 2nd ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Tappe, Oliver. 2013. “Faces and Facets of the kantosou kou xat – The Lao ‘National Liberation Struggle’ in State Commemoration and Historiography.” Asian Studies Review 37 (4): 433–450.

- Whitington, Jerome. 2018. Anthropogenic Rivers: The Production of Uncertainty in Lao Hydropower. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

- Yamada, Norihiko. 2018. “Legitimation of the Lao People’s Revolutionary Party: Socialism, Chintanakan Mai (New Thinking) and Reform.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 48 (5): 717–738. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00472336.2018.1439081.

- Zani, Leah. 2019. Bomb Children: Life in the Former Battlefields of Laos. Durham: Duke University Press.