ABSTRACT

This paper presents an analysis of the politico-economic and ethnic-social basis of difference, paying special attention to the anti-difference violence suffered by indigenous peoples and the concrete experience of the Gurani-Kaiowa in Brazil. Ethnic-social differences and commonalities are here examined through a social sciences reinterpretation of Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. In this magistral book, Hegel problematises and gradually resolves many questions about human perception, the shortcomings of reason, and the incremental evolution of reason that can only happen through mediation and interaction. The unique features of each social group can consequently expand into ethnoclass commonalities shared with other, unique populations. That is particularly relevant to understand the many pressures to reduce the Guarani-Kaiowa to an indeterminate proletarian condition (generic members of the working class or the peasantry), which has nonetheless revitalised their sense of indigeneity. The Guarani-Kaiowa are different from other segments of the working class, but the more they see, and are seen, as different, the more immersed they become in the subalternity of the rest of the dispossessed population. The identification of the indigenous population as both members of the working class and of unique ethnical groups has major political consequences (the negation of the negation) in terms of poor-poor alliances that can challenge politico-economic trends and, particularly, the illegitimate concessions to agribusiness farmers.

Difference, Conflicts and Differentiation

Current global socio-political trends, in the first decades of the new millennium, are characterised by an increasing complexity that regularly defy most interpretations and analytical approaches. It is often the case that many important features are unnoticed or omitted, whilst questions of secondary importance become a top priority for public and private policy-making. In that context, crucial differences are ignored by academics and political leaders, at the same time that grassroots demands and basic needs may go unnoticed. Still, the contemporary configuration of a great part of the world, following the Western model of consumption, rent-seeking and waste, is extolled as the best possible socio-economic and ethical order. Liberal institutions and representative democracy are considered the culmination of a process of change initiated with the French Revolution and all other alternatives were proven to be significantly worse (e.g. the influential argument of Fukuyama Citation1992). Nonetheless, this is nothing else than a triumphant argument that emanates from the top, coming from those who reject other social experiences that don’t observe the Western canon. According to the dominant political and economic institutions, differences between and within social groups are advantageous as long as these can be quantified, profited from and politically sanitised. Higher levels of labour exploitation and social degradation are therefore rationalised by the stifling of most differences and by the tacit control of those treated with indifference because considered to be too different. This strange reality, as revealed by Bauman (Citation2017), is so distressing that, for the marginalised majority (low-income workers and subordinate social groups), the dream is not in the future; only the past seems to hold any hope. What has already happened is more easily registered by each individual, whilst the future is nebulous and disturbingly contingent on what the rest of society chooses to do or not to do.

This paper offers an analysis of the politico-economic and ethnic-social basis of difference, making use of the striking example of anti-difference violence suffered by indigenous peoples under the hegemony of financial-rentier capitalism (Bresser-Pereira Citation2017). Its departure point, informed by a reinterpretation of Hegel’s dialectical and ontological system (Rockmore Citation1992), is that, rather than a descriptor (the predicate of a subject), difference is a mediator of relations and a facilitator of connections or disjuncture. Difference is, by definition, a relationship between more than one thing, but it is also a reflexive return to the one, as something that either reinforces a presumed contrast with the other, or helps to mitigate the distance that seemed to separate them. How people respond to difference is central to how they see themselves, who they want to become, and what they try to avoid. Differences are mediated and realised through manifold social interactions. There is, thus, an existential tension between being something and not wanting to be something else. Differences cannot be taken as static or above social relations, but as catalysts either for approximation or distancing in relation to what is being differentiated against. The world contains great diversity and major contrasts, but attitudes towards difference reflect how each nation, social class and individual deals with their perceived and represented condition. For all these reasons, socially constructed patterns of differentiation have great political relevance, but they have frequently been clouded by the conceptual and operational difficulty in dealing with other perspectives on life, economy and society. The desire to protect unique features and rejecting others represents lived proof of the immanence of difference in the world.

A striking sense of the biased treatment of difference can be grasped by standing near a fence that divides an indigenous reservation from surrounding agribusiness farms, a relatively easy exercise to undertake in many parts of the American continent nowadays. On one side of the fence are artificial pastures and fields with almost homogenous crops (which are more and more transgenic) cultivated on soils prepared with the use of heavy machinery, fossil fuels and high doses of agrochemicals (fertilisers and pesticides). On the other, a much more complex ecosystem with bushes, grasses and trees (the actual composition depending on the actual of the land) and a diversity of animals and microorganisms that is several orders of magnitude greater. In addition, the landscape managed by native communities holds diverse knowledges, experiences and practices cherished and maintained for several generations by people with distinctive features and languages, even though their socio-economic condition is stereotypically compared with the material destitution of poor peasant communities and urban homeless populations. Contemporary agribusiness farmlands are homogenised spaces where a huge amount of capital circulates (funded by bank loans and foreign investment) but very little is left behind for local communities, apart from socio-ecological impacts (typically treated as economic externalities, without any deeper consideration of the multidimensionality of socio-ecological problems). Most technical operations are developed and tested in agronomic research centres located thousands of kilometres away, by foreign scientists who have never heard of the region where agribusiness farms are located. Agribusiness is fundamentally predicated upon estrangement and subsequent indifference to the discriminatory differences created in the course of agrarian development.

Ranches and agribusiness farms in South America, a main source of agricultural commodities to Europe and Asia, and enthusiastically celebrated by politicians, economists, urban elites and the dominant mass media, are in effect monuments of indifference to the socio-ecological differences that ultimately sustain them, and which have been viciously appropriated to satisfy exogenous demands. According to Žižek (Citation2013), the organised indifference for the condition of subaltern groups is the fundamental form of violence inflicted systemically and anonymously by mainstream forms of governance. Replicating elements of the old ideologies brought by the Iberian conquerors in the sixteenth century, the material misery of the native population was always blamed on them and presented as their own fault (in the history of the Americas, victims are always considered guilty of causing their own fate, as in the case of sexual ethic-related violence today). According to this narrative, the only viable alternative would be for indigenous people to surrender their domestic and professional lives to market-based relations, as championed by businesspeople and large-scale landowners. It is less common to find references to the fact that this reasoning only benefits a small minority of the non-indigenous population, and is based on increasing social and ecological degradation. Against powerful pressures for homogenisation and the disregard for the condition of subaltern social groups, difference is not an epiphenomenon of socio-spatial relations, but a genuine worldmaking driving-force, provided that it is the handling of difference that paves the way to specific interactions that end up shaping society and, ultimately, the reality of the world. There exists not merely ‘a world of difference’ but a world because, and out of, differences. People understand and react to those deemed different or not different in ways that either reinforce or challenges the shared reality of the world.

Nonetheless, as it will be discussed below, things are more complicated than the balance between difference and no difference, especially because existence, following Hegel, is first and foremost dialectical: something is and is not at the same time. This ontological tension is integral for the advance of self-consciousness and, likewise, depends on the meaningful engagement of various segments of society. Consequently, it is necessary to consider the whole, always unfinished, historical process that produces, and is the product of, differences. The manifestation and actualisation of difference take place at the interconnected trajectory between the parts and the whole, which underpins the immanence of its transgression and transformation (because of immanence, the future is immanently what it must be). When emphasising the importance of the whole, Hegel (Citation1977, 79) is not thinking of a static reality; he claims that truth is realised in its process of unfolding. Hegel certainly set himself the ambitious task of eventually organising all possible thoughts about the world, from mechanics to anthropology and politics. This was a sizeable target, even for the most formidable thinker of European modernity, regarded by Nancy (Citation2018, 11) as ‘the inaugural thinker of the contemporary world.’ Hegelian philosophy, centred around reciprocity, self-consciousness and collective action, constitutes a very insightful approach to investigate and understand the dynamics of difference in the lived world and across the various scales of reality. Perhaps surprisingly, all that is relevant to examine indigenous ethnoclass differences and commonalities.

Today’s Relevance of the Hegelian Approach to Difference

In the final part his most influential books, the Phenomenology of Spirit, Hegel (Citation1977, 485) presents a refined association between the ‘complete and true content of the Self’ and the realisation of reason in actuality, that is, in the conscious engagement with the world. Through the differentiation of the person (the ‘I’) from itself – its pure negativity or the dividing of itself – the individual becomes a pure being-for-self of self-consciousness. As further argued by Hegel (Citation1977, 486), the Concept (or Notion, basically a metonym for human reason) is realised in its objectivity and through mediation with others. Through a long and arduous intellectual journey over the pages of the Phenomenology, Hegel problematises and gradually resolves many questions about human perception, the shortcomings of reason, and the incremental evolution of reason through mediation and interaction. The ‘I’ (an individual with his or her uniqueness) is transmuted into a superseded universal, but still remains unique and distinctive. In that sense, Hegel (Citation1977, 287) proposes that to be different is to act, and action leads to both recognition and consciousness, because ‘individuality and action constitute the principle of individuality as such.’ Action is already inserted in individuality, which itself results from action. Difference is what presupposes such interaction and creates a space to advance human consciousness of itself and the world. The trajectory of reason (as also a nexus of agency) is a collective project, never fully realised and fraught with possibilities because of the interaction between self-conscious agents. The reality of the world turns out to be not just the sum of its constituent parts, but rather the productive interaction between individual, differentiated elements of an interdependent totality (the whole that exists, shapes and is shaped by the parts).

For Hegel, the generic is dynamically contained in the specific, but the dialectic continues in the constitution of the universal by the particulars. Each moment of the dialectic is an interminable, non-teleological play of oppositions without resting places (Jameson Citation2017). A social group living in a remote location, for example, with highly unique practices and traditions, is a specific, but it is a constitutive element of other totalities (e.g. the entire national or global population) that contain and realise (i.e. produce) this same social group. As Badiou (Citation2012, 85) further asserts, indefatigably in dialogue with Hegel, that ‘a world is a regime of relations of identities and differences.’ Difference is an ontological priority, given that to be alive is to be different in tandem with various levels of proximity and sameness. The interaction between different beings will necessarily be contradictory, because it will naturally reflect multiple, dynamic identities and differences. An additional important Hegelian insight – contrasting with the Unitarianism of Spinoza and the non-contradictory, aprioristic rationalism of Kant – is that the individual himself or herself is contradictory, but that is an integral element of her or his existence. The contradiction is an inescapable feature of individual and social life, and the main element of self-awareness. For Hegel (Citation1977, 142-143), difference ‘is a plurality of categories’ and ‘in their plurality they possess otherness in contrast to the pure category.’ It constitutes a ‘negative unity of the differences … that excludes from itself both the differences as such, as well as that first immediate pure unity as such.’ The singular individual is a transition to an external reality, and consciousness is able to apprehend that it is a unity that is ‘referred to an ‘other’, which in being, has vanished, and in vanishing also comes into being again.’

The being, for Hegel, is contradictory and must deal with this inherent contradiction through the search for higher levels of reason (McGowan Citation2019). Difference entails contradiction, but it starts with the individual and expands into the contradictory interaction with other individuals, which both constitutes the individual and shapes the universal. Hegel’s ontology (and his idiosyncratic phenomenology) not only stabilises contradictions like this, but places contradiction at the centre of the comprehension of and action upon the world. Croce (Citation1915, 19) identifies a seminal insight in the solution offered by Hegel to the problem of oppositional difference, namely: ‘the opposites are opposed to one another, but they are not opposed to unity.’ This unity is a synthesis, a movement and a space for further development, considering that ‘becoming’ for Hegel is a synthesis of opposites, not of identities (although Croce also considers the Hegelian equivalence between the ‘theory of opposites’ and the ‘theory of distincts’ to be an ‘essential error’, because the dialectical method cannot be applied to those parts of reality that do not have an antagonistic character; however, Croce minimises the fact that Hegel never denied the existence of relations of diversity, but simply considered opposition to be deeper than diversity, as observed by Abazari Citation2020).

Questions about difference, as approached by Hegel, allow us to make sense of a fundamental interpretative impasse: the contrast between enabling (as concurrence and synergy) and disabling (as inequality and injustice) differences. Unfortunately, there is still today a great deal of misunderstanding and misjudgement about the profound politico-spatial implications of difference. The fragmentation of the totality of relations is, thus, associated with the disconnection between responsibilities, causes and effects, which all evolve according to the perpetuation of inequalities and indifference for widespread problems and exploitation. An appreciation of the ontological primacy of difference can in no way presuppose or imply a convergence towards the middle ground of liberal politics and ensuing public policies. On the contrary, as differences come about before and through interaction, they are a nexus of perceivance, reaction and dispute that disrupts implicit consensus. Socio-political activity, or the lack of it, is predicated upon perceptions of old and new differences. For Hegel, reason is more than mere understanding – it requires a self-conscious reflection – and social and socio-ecological interactions help to fill the gap between reason and understanding. As indicated by Heidegger (Citation1988, 122, who was himself very aware of the Hegelian system), understanding lies in the movement of the parts and is posited in the difference between space and time, which are distinguished from each other in movement. In that regard, an enormous amount can be learned from the lived and embodied experience of social groups marginalised by Western-based modernisation and capitalist development. The disturbing condition of the Guarani-Kaiowa indigenous people in Brazil, who maintain and mobilise their cherished differences to fight for the recovery of land lost to agribusiness, at the same time that form alliances with other subaltern social groups, will be examined in the next section.

Guarani-Kaiowa Ethnoclass Differences and Commonalities

This section will consider the socio-spatial trajectory of the Guarani-Kaiowa in the Brazilian State of Mato Grosso do Sul and the dishonest pressure exerted by exclusionary development forces to confine them further and further to the margins of an economy dependent on agribusiness exports. The ongoing tragedy of the Guarani-Kaiowa, the second largest indigenous population in the country and the main victims of violence perpetrated by farmers and the police, is the result of anti-difference policies that have transformed them into regular victims of the necropolitical tendencies of agribusiness production. (As of this writing, in September 2023, a 92-year-old shaman Ms Sebastiana Galton and her husband were brutally assassinated and the bodies were burned in the Indigenous Land Guasuti, municipality of Aral Moreira, cf. communiqué issued by the Indigenist Missionary Council (CIMI) on 19 Sep 2023). Almost every week it is reported the murderer of Guarani-Kaiowa people, especially political and religious leaders. They are not only victims of an enduring genocide – called Kaiowcide (Ioris Citation2021) – but their lives themselves are dictated by the genocidal imperative of agribusiness. They have been confined to the edges of vast agribusiness farms (mainly producers of soybean and sugarcane) ostensibly established in indigenous lands that were illegally and violently grabbed during territorial conquest and, particularly, the advance of conservative modernisation into the Centre-West region of Brazil in the second half of the twentieth century (Ioris Citation2017). Most Guarani-Kaiowa now live in miserable material conditions, despite the high agricultural value of their land and the lavish ecosystems found in their ancestral areas (Mura Citation2019). The annual reports on violence against the communities published by several organisations provide some grim statistics on the growing numbers of conflicts and murders (e.g. CPT Citation2023). Most of the aggressions are regularly committed by private militias and the state police acting in the name of landowners and agribusiness farmers (tacitly supported by politicians, mainstream journalists, many academics and rich, land-owning magistrates).

These attacks on Guarani-Kaiowa difference are based on the central paradox of valuing indigenous land and indigenous workforce, bringing them to the realm of the agribusiness-based economy, but despising what was socially and ecologically unique in the life and practices of the same population. At the same time, the convergence of the myriad of experiences constitutes the overall situation of the Guarani-Kaiowa and their brave confrontation with large-scale landowners and the leaders of agribusiness-based regional development, which is persistently legitimised by a combination of ideological and media strategies (Pompeia Citation2020). The clashes seem inevitable, at least from the intolerant perspective of the stronger politico-economic sectors, given that the southern part of Mato Grosso do Sul was all indigenous land and mainly occupied, for several centuries, by the ancestors of today’s Guarani-Kaiowa (Ioris Citation2020). It was a vast territory with no fixed borders and a total area around eight million hectares, where the Guarani-Kaiowa and other, relatively smaller indigenous nations, used to live and plan to return (at least to a significant part of it). Racism and spatial segregation have operated as perverse catalysts of an exploitative economic order that transformed the indigenous population into refugees in their own land. White supremacy, as in the case of settler colonialism and agribusiness-centred regional development of Mato Grosso do Sul, is essentially based on a narrative of the supposed inferiority and irreversible decadence of the Guarani-Kaiowa. They are very often depicted as degraded versions of vanished populations and forced to conform to the standard stereotypes of behaviour and success. The Guarani-Kaiowa are, thus, denied the possibility of being meaningfully different to others confined to a category of sub-humanity, characterised as belonging to a bygone age, with deficits of ‘reason’ and ‘refinement’.

Genocidal violence has deteriorated since the late 1970s when the Guarani-Kaiowa initiated a campaign to recover their ancestral, sacred areas (called tekoha in the Guarani language). Dozens of indigenous leaders, elders, youngsters and children have died and continue to die almost every week. In May 2022, for example, as a result of the mobilisation of Guarani-Kaiowa families to recover the tekoha Joparã in the municipality of Coronel Sapucaia, near the old reservation of Taquaperi (with 3,300 people living in terrible conditions and squeezed in only 1,777 hectares), Alex Vasques Lopes, 18 years old, was murdered but the authorities never bothered to investigate the crime. A month later, in an area called Guapo’y, the indigenous protesters were expelled from the land by farmers (without any judicial authorisation) and Vitor Fernandes, 42 years, was also assassinated. In the following weeks and months, other members of the Guarani-Kaiowa communities continued to be shot and killed (as Vitorino Sanches, 60 years old, also killed in Guapo’y in September 2022). Because of the aggressive racism of the newcomers and their persistent, illegal appropriation of native land, it seems impossible to imagine a compromise with agribusiness, just as it is unlikely to envisage any stable accommodation without major changes in the national balance of power (today dominated by finance and agribusiness). Current genocidal trends in the State of Mato Grosso do Sul became even more explicit after the election of the neo-fascist government of Bolsonaro in 2018, which was followed by a serious deterioration in the treatment of indigenous demands and respect of their rights. Adding insult to long-lived injury, the Bolsonaro administration (2019-2022) refused to accept the distinctive markers of difference held by numerous indigenous nations, therefore preventing them from having their areas lawfully returned and even from the most basic forms of health and food assistance (INA Citation2022).

Not a single indigenous piece of land was titled by the ultra-right-wing administration of Bolsonaro and the services provided to indigenous communities were seriously undermined, particularly during the Covid-19 pandemic when the federal agency (Funai) avoided vaccinating indigenous people in urban areas or in indigenous lands still without full recognition. Such grim reality can only be properly interpreted, in the words of Žižek (Citation2013), as ‘less than nothing’, where a lot has to improve in order to achieve the level of nothingness. The agribusiness sector has been an embarrassing charade, as it repeatedly tried to conceal that it produces huge amounts of tradable commodities, but very little of ‘real’ food. It is basically a massive production of ‘less than nothing’. It cultivates and harvests its own nothingness, only disguised as ‘regional development’, leaving behind permanent environmental and social impacts (Ioris Citation2018). Agribusiness is less than nothing also because it is based on the perpetuation of indifference through the instrumentalisation of socio-spatial difference. It reflects a well-orchestrated effort to conceal this deeply genocidal pillars of the agribusiness-based development that greatly define contemporary Brazilian macroeconomics. The denial of the Guarani-Kaiowa as rights bearing people and the simultaneous ideological conversion of into unspecified peasants or urban-industrial workers is an implicit strategy to demoralise and demobilise the communities. The pathological drive towards indifference is clear indication of the unhappy consciousness of agribusiness, as the duplication of self-consciousness within itself, its projection into something else that does not allow it to perceive its own internal fragility. For Hegel (Citation1977, 126), the ‘Unhappy Consciousness is the consciousness of self as a dual-natured, merely contradictory being.’

Memories of the brutality suffered during the aggressive advance of the agricultural frontier are illustrated in the following interviews (collected by the author during several research projects in recent years, working with and for the indigenous communities, and later translated from the Guarani language):

‘I remember the stories that my father used to tell us when I was five. He told us that the ‘whites’ [non-indigenous] entered our land, they had to run, abandon their houses and go. Later they [the invaders] returned, again forced them to flee, leave the plants, the house, all became empty. This happened several other times. My uncle tried to make our settlement safer, but it was never safe. The indigenous families were too few, only a small number of people. (…) It was only much later, after a long process, that the land was demarcated.’ Woman, Indigenous name Kunha Uruku, 53 years, Pirajuí indigenous reservation, municipality of Paranhos

‘My name is Ava Vera Vera Rendyju, but people also call me Xxxxx and the majority know me as Cachi. I am 62 and I live near [the city of] Amambai. I have lots of memories and I am happy to recall them, as I understand, because we have seen so many changes, [the world] is no longer how it used to be. To be born and to transmit knowledge today, it is very different. That is why I meet many people, many folks, who live poorly in our community, who bring what is wrong for us; I no longer have a true happiness, but I am already scared, there are many things that we can’t defeat and that most [people] are not able to overcome.’ Man, Amambai indigenous reservation, municipality of Amambai

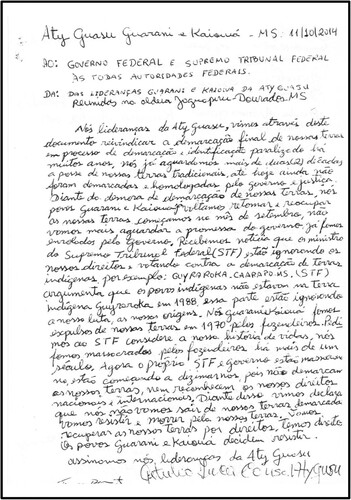

Figure 1. Letter of Protest Against the Brazilian Government Signed by Indigenous Leaders at the Great Assembly (Aty Guassu) on 11 October 2014.

The Guarani-Kaiowa have lost almost everything (in material and monetary terms) after centuries of attacks, displacement, oppression and exploitation, but have not abandoned their resolve to be a recognised as a self-referential nation (Chamorro Citation2015). They have understood that it is impossible to evade regular interactions with non-indigenous (and indigenous) groups and public authorities, but they are fully aware that those other segments of society are unable to reach the core of their differences. Mariátegui (Citation2011, 149) rightly affirmed, a century ago, that ‘the solution to the problem of the Indian [land grabbing and miserable working exploitation in South America] must be a social solution. It must be worked out by the Indians themselves.’ The most important and highly effective reaction by the Guarani-Kaiowa nation against the oppressive indifference of the agribusiness-based economy is the grassroots mobilisation, which is networked support across families and communities, to reinstate difference and recreated ethnic spaces. There is a perennial struggle to return to their own lands, confronting the agribusiness opponents and putting pressure on the perverse bureaucracy. The initiative to recover what always belonged to them are called retomadas [retakings], which involves the reoccupation of the area lost to land grabbers by the displaced community. The retomada is fundamentally a process of Aufhebung, a socio-spatial resurrection out of the apparent absence created by successive indigenous genocides. As pointed out by Gibson-Graham (Citation2020) the past is both a prelude and a potential for radical transformation, but it depends on ‘reading for difference’, that is, attending to the great variety of non-capitalist or ‘more-than-capitalist’ economic activities, including sharing and reciprocity practiced by indigenous peoples.

Against the self-destructiveness and ruin caused by agribusiness, the Guarani-Kaiowa maintain the determination to ‘be there’ that derives from the genocidal coercion ‘not to be anywhere.’ The attack on their distinctive differences has further politicised the interaction between indigenous communities and families, strengthened their resolve to react against land grabbing and facilitated the alliance with other (indigenous and non-indigenous) socio-political movements. Collective mobilisation departs from what they have as unique in the Guarani-Kaiowa society, but also from what is shared with other subaltern segments of the national society, increasingly improving the realisation of the importance of specific and common political agendas. Hegel (Citation1977, 488) states that ‘so far as Spirit is necessarily this immanent differentiation [i.e. transformation from consciousness into self-consciousness through the experience in the world], its intuited whole appears over against its simple self-consciousness, and since, then, the former is what is differentiated, it is differentiated into its intuited pure Notion, into Time, and into the content or into the in-itself.’ Political alliances across families and with other subdivisions of the working class have represented the main hope for the thousands of destitute Guarani-Kaiowa families living in the overcrowded reservations and in precarious road encampments, who summon family attachments, memories and knowledge of the tekoha [ethnic territories of extended families] against the generic forms of socio-ecological interaction introduced by commercial farmers (Brand Citation2004). It is a movement that Hegel (Citation1977, 488) describes as Substance charged as Subject and ‘exhibiting itself as Spirit’ [conscience developed into self-conscience, the Notion or the Self that knows itself]. The ancestral land is the most powerful reference of both identity and socio-political self-consciousness. As stated in the declaration of the 2011 Aty Guassu:

For the Guarani their territory is the place where their ancestors used to life and where biodiversity, culture and spirituality come together. The territory and all that exists there are fundamental rights, and the Guarani nation does not and will never renounce to them, because it is part of our existence, identity, material life, culture and religion. In view of that, the communities demand that the public authorities fulfil their obligations in relation to our lands. We don’t want to receive only scraps, while national and international groups, as those in the soybean and sugarcane industries, continue to occupy and accumulate wealth from our lands.

The retomada invariably involves strong religiosity and requires great courage because it will be inevitably resisted by the farmers currently using the land, who will recruit armed militias and the police force to expel the indigenous contingent (Benites Citation2014). The indigenous movement finds existential reference and encouragement in the trajectory of ancestors and elders, who are the main holders of knowledge and memories. Despite all the difficulties and the organised indifference of the Brazilian State, the retomadas are the more vivid proof of the importance of indigenous difference and its profound political implications. It is the reaffirmation of what they have always been and where to indefinitely remain. If peasants are entitled to a piece of land, the natives have ancestral rights to the piece of land of their ancestors. They have never really abandoned their lands lost to agribusiness and, through time, understood the knowledge of the other (i.e. agribusiness) as the other of their knowledge, culminating in self-knowledge now put in place to articulate the retomada of the land that has always belonged to them. As commonly mentioned by the Guarani-Kaiowa, ‘we are the land, and the land is us.’ The rationality of the retomadas is much deeper than the logic of agrarian reform (which is nonetheless strongly rejected by the agribusiness sector and by most politicians), but it is guided by the solid conviction that, because they are on the right side of decency and have godly support, their way of life will prevail. Socio-spatial differences cultivated over countless generations are being mobilised as a powerful tool and a prefiguration of a future that would bring them back to the beginning of everything.

Considering the widespread material poverty of the Guarani-Kaiowa and the asymmetric power of the agribusiness enemies, ‘space certainty’ may seem foolish, but the geographical experience demonstrates surprising willingness to resist and confront the most difficult institutional and political obstacles trying to reclaim difference on their own terms (Ioris Citation2022). The Guarani-Kaiowa have more than hope, but the strong certainty that, one day, things will change and they will be able to return to the land of their forefathers. If Hegel is right to say that only the whole is the truth, this whole has multiple constitutive forces and places, every single particular is also holder and producer of a constantly reshaped commonalities. Hegel (Citation1977, 3) explains his analytical method by arguing that ‘To judge a thing that has substance and solid worth is quite easy, to comprehend it is much harder, and to blend judgement and comprehension in a definitive description is the hardest thing of all.’ Hegel’s comment is even more pertinent considering that there is no single Guarani-Kaiowa trajectory, but each community and extended family, living in separate locations and facing specific enemies, has their own history and geography, but these are part of a much larger totality of ethnoclass struggles and achievements.

Ethnicity, Class, Ethnoclass

The organised attempt of the Guarani-Kaiowa to have their unique features and ancestral lands properly recognised helps to demonstrate that difference is not a static attribute to measure social distances, but an intrinsically relational phenomenon and a dynamic force that fosters either an association or separation depending on the self-consciousness of those involved. Because difference starts in the actuality of the individuals’ outer and inner features that flourish vi-à-vis other people and social groups, Hegelian dialectic can be invaluable for interrogating the complex reality of the world shaped by the perennial interplay between differences and those who are, deserve and want to be different. The being exists amidst a spiral of interacting processes pulling in various directions and its existence is constantly reshaped through an interplay with the other and with itself. Pure, isolated difference is a myth, a figment of the imagination, hence the importance of Hegelian tension between consciousness and self-consciousness, and his systematic insistence on non-binary positions and on ontological openness. Difference, according to Hegel, is consequence of self-estrangement and externalisation of the self, not because of self-serving interests but exactly because of the self’s incompleteness and the need to be actualised in the other, who is also incomplete and searching for completeness. A main remaining challenge, for both academics and non-academics alike, is certainly to mobilise Hegelian theory to confront the shortcomings of late modernity and the prevailing a mass cultural mentality. What dominates today is a web of relationships that are supposedly inclusive, but in effect indifferent to the condition of peoples and places. Most politics nowadays is typically circumscribed to formal rights and to difference as purely personal attributes, at the expense of communal experiences and collective consciousness.

Denying differences can considerably facilitate political controls, whilst the manipulation of differences can equally lead to subordination and repression (such as segregation because of ethnic, spatial or religious identities). That constitutes an attempt to instrumentalise difference according to the most powerful interests, as an imposition of difference in itself against the prospect of reclaiming of difference for us (i.e. on the terms of the majority whose differences were instrumentalised). Instrumentalisation aims at transforming differences into something politically inconsequential. Informed by Hegelian dialectics and taking the Guarani-Kaiowa socio-political dilemmas into account it should be possible to draw some general conclusions about the metabolism of difference and the contestation of indifference. A first observation is that relations of difference are configured and evolve according to collectively lived and shared experiences in specific places and spaces. Social interaction produces socio-spatial settings that result from this interaction and likewise affect social life. If for Hegel human existence is consolidated then reason and for Marx the totality of human existence is given by labour relations, those totalities can be really comprehended as contingent relations of difference. Lefebvre (Citation1991) argues that space is immanent in politicised social relations and, consequently, differences in and through space are also manifested across places and scales (according to the Hegel logic, any particular is also a universal and only exists as part of the universal). This process of change is never neutral, but enfolds according to the balance of power and hegemonic ideologies. At the same time, according to Hegel, the gap between essence and appearance is never completed, and in this case space is never fully itself, but always open to challenge and transformation. That is even more the case considering that people (as indigenous nations) are creative agents, who grasp and simultaneously disidentify (get distance) from the existing order to project an alternative future that brings elements of the past.

It leads to the second observation that patterns and practices of difference are maintained and renovated primarily following the exercise of power and the influence of the stronger segments of society. Relations of difference really endure because of a contingency of encounters in which advantages and disadvantages are challenged or reinforced according to power imbalances historically and spatially grounded. Politics certainly plays a key role in the organisation and maintenance of spatialised social practices, but it is also nurtured by the configuration of social action according to the most powerful interests. Mainstream development nowadays is indeed a very selective phenomenon, given that the evolution of socio-spatial relationships associated with the modernisation of the world has only included a fraction of society, what normally increases hierarchies and stratification (Luhmann Citation1982). This has to do with ideas about consent and purity imposed from those in control, even if only implicitly. The main sources of politico-economic power and the key producer of difference continue evidently to be the capitalist relations of domination, alienation and exploitation. The circulation of capital and the expansion of capitalist relations work through the destabilisation and regulation of multiple identities and practices. As indicated by Katz (Citation2009, 243), ‘capitalist accumulation works in and through the production of difference (…) at different scales.’ Yet, one of the main secrets of capitalist modernisation is precisely its capacity to conceal the importance of socio-spatial differences behind the abstract universality of market transactions. Difference becomes, then, more than a locus of dispute but the basis of private asset ownership and of the circulation and accumulation of capital. The hyper-modern, capitalist world is basically predicated on certain differences, mobilised to pave the way for equalised economic basis that are required in order to promote value extraction and unrestricted trade. According to Qian and Wei (Citation2020, 251), capitalist development depends exactly on the absorption and appropriation of local specificities, which assembles and reorders ‘existing registers of differences – local practices, relations, values and norms, but also differentiations in economy, education, health, social and human capital, etc.’ As also pertinently recommended by Katz (Citation2009), social theory needs to account for class differences and the uneven capitalist development in direct connection with the specific circumstances of gender, sexuality, racism, patriarchy, etc. The interrogation of difference is directly related to the rationality and the internal contradictions of capitalist relations of production and reproduction.

Our third inference is that circumstances fraught with political antagonisms increasingly impact multiple relations of difference, although the resulting tensions will accumulate over time and eventually trigger manifold reactions, which will be manifested through actions taken by those dissatisfied with the treatment of their differences or willing to reclaim what has been denied by other social groups. The interruption of the prevailing order, as in the case of strikes, uprisings, mobilisation or elections, are interventions that express spatial presuppositions and aspirations for the future. The configuration of the political into the engine of contestation is consequence of the autonomous realisation (self-consciousness) of deep political connotation of differences. The reassertion of differences can result in opportunities to challenge a given state of affairs, in particular the exclusionary and oppressive hegemony of capitalist relations. Capitalist modernity is founded on the careful instrumentalisation of socio-spatial differences, which are exacerbated and reinforced, or minimised and circumscribed when is required. However, despite the ideological imperative to convert everything to the undifferentiated grammar of money and political control (including human health, ecological processes and even the atmosphere, vis-à-vis carbon markets), there is always a surplus or excess of difference (autonomous differences cherished and preserved by marginalised social groups) that is not fully incorporated in the homogenising flows of commodification and exploitation. This ‘excess’ of difference is the politicisation of the residual differences mentioned above, which are acted upon and pave the way to multiple forms of contestation at various scales. Reality is dynamic, unpredictable, but it is also subject to contingent laws and forces, which are themselves unsteady and subject to change.

Not only differences are manifested in and through socio-spatial interactions, but the set of relations that produce space leads to a necessity of difference in the lived reality of the world. According to Hegel (Citation2010, 222), necessity is ‘in itself the one essence, identical with itself but full of content.’ This necessarily happens through ‘an other’ that is the medium of the activity, something that is both contingent and also a condition. What is necessary comes back to itself mediated by the other, it is an unqualified, unconditional return affected by the circle of circumstances (effectually, the concrete socio-spatial setting). Necessity is something merely posited through the other, but with unhindered outcomes; for Hegel (Citation2010, 230), ‘the truth of necessity is thus freedom.’ Differences influence and condition socio-spatial relations, not in any predeterminate way, but according to developments mediated by the relation with the (economic or otherwise) other. In other words, class-based differences mediate, and are mediated, by other differences beyond the economic domain, and vice versa (Jonsson Citation2022). There is no antagonism between class and more-than-class differences, but these are all markers of identification instrumentalised by spatialised capitalist relations and reclaimed back by individuals and social groups who were negatively impacted. As argued by Thompson (Citation1966, 9), ‘‘working classes’ is a descriptive term, which evades as much as it defines. It ties together a bundle of discrete phenomena … unifying a number of disparate and seemingly unconnected events, both in the raw material of experience and in consciousness.’ People can experience, and claim, many forms of non-economic differentiation, such as gender, religion, age, level of education, sexual orientation and place of origin, but class and ethnicity are certainly two main nexuses of difference.

Those main pillars of socio-spatial difference co-determine each other and eventually result in ethnoclass differences held by all humans and according to their specific and general circumstances. All people, even if unaware of those, belong to a social class and have an ethnic ancestry, which jointly affect their life and actions. Rather than a separation between those two equally important categories, in reality everybody belonging to a class also has an ethnic identification, although sometimes some markers of differentiation may be left implicit. The synergies between class and ethnicity need to be treated as dynamic, constantly unfolding networks of interaction. As proposed by Pulido (Citation2002, 762), questions around race and class are ‘hardly new – but how to build explicit anti-racist organisations rooted in either class or anti-capitalist [class-based] politics is quite challenging.’ Class is necessarily realised in a spatial setting (both the working environment, the residential areas of labourers, managers and businesspersons, and the chains of input supply and trade), as much as personal and collective differentiation are expressed in space (in areas to live and celebrate difference, to mobilise and protest, and to shield from unwelcome homogenisation). The systematic attacks on their right to be different and the exercise of indifference have corroded the possibility for indigenous peoples to have equal or equivalent economic and social opportunities (let alone compensation for past violence). In a world shaped by neo-colonialism and severe exploitation of society and of the rest of nature, to be and remain indigenous depends on a fight to remain different in order to be treated fairly and compensate for violence accumulated over many generations. The thousands of contemporary indigenous groups are mainly descendants of peoples who suffered unimaginable forms of aggression, disruption and displacement, generally associated with land grabbing, resource extraction and labour exploitation. Yet, to be indigenous is not a genetic or racial condition, but a relational operation that is both different and replicates other economic and socio-spatial asymmetries, as seen in the painful but rich trajectory of the Guarani-Kaiowa.

Conclusion: Struggling in, for and Through Difference

The Guarani-Kaiowa, just like many other indigenous peoples facing similar challenges, have become increasingly and unwillingly involved in agrarian capitalist relations that, first, expelled them from their ancestral areas and then confined to the fringes of the regional society, forced to live in rural or urban peripheries, seen as degenerate relics of themselves. The hegemony of contemporary agribusiness permeates not only crop and animal production, but strongly reconfigured consumption patterns, social values, the rule of law and, ultimately, the sanctimony of large private properties (regardless of their illegal genesis and exclusionary effects). However, to be indigenous is to exist politically in space and in relation to antagonist forces and processes that constantly reinstate their ethnoclass condition. The Guarani-Kaiowa have to negotiate, on a daily basis, their subsumption under prevalent socio-economic relations and their concurrent attempt to escape from the same experience. The Guarani-Kaiowa population is inside the agribusiness-based economy because it has demanded their land and labour, and it is outside because of the antagonistic (anti-difference) attitudes of farmers and authorities. This hybrid indigenous is supposed to be increasingly less indigenous and more and more inserted in the generic working class (whose mixed ethnic configuration is despised by the members of the regional landed class, who themselves claim to be whiter and more righteous than they really are). Through resistance and the ability to handle ethnogenesis on their own terms, the Guarani-Kaiowa have been able to mediate difference among themselves and in relation to the non-indigenous population, despite all the misery and death inflicted by agrarian capitalism.

The collective of any society contains an internal plurality of parts that are beings-for-self that, following the expression of internal qualities through the movement of the force, become beings-for-another. Each part is in itself a unity that, because of the evolution of understanding, is expressed and reconciled in the whole. Difference is actualised in the movement of force and the connection with the other (for Hegel Citation1977, 82, ‘difference is nothing else than being-for-another’), which is exactly what agrarian capitalism corrupts once it tries to impose a static and indifferent space. The multiple associations and potential ethnoclass synergies between indigenous and non-indigenous workers are a perennial menace to the tenuous politico-spatial order. Making use of an anti-essentialist class analysis, as proposed by Gibson-Graham (Citation2020), it can be identified an ethnoclass boundary that separates subordinate social groups from the hegemonic agro-industrial class and those in control of regional development. The conversion of socio-spatial difference into a nexus of consciousness and trigger of political agency does not only follow the accumulation of knowledge and ethnoclass experiences. Against all the appearances, geographical agency of the Guarani-Kaiowa is more active and creative than that of agribusiness farmers, given that the latter basically replicate techno-economic protocols conceived elsewhere. There is nothing given a priori in terms of the intensity and the actual features of those antagonisms, but it depends on the actual engagement and the balance of power between farmers, non-indigenous workers and indigenous communities.

On the one hand, the dialectics of universals and particulars in the tense context of agribusiness intensification is connected with wider politico-economic pressures for the equalisation of the conditions of exploitation required to organise inequalities of a capitalist society. On the other, there is a diversity of attitudes among agribusiness farmers and one must avoid a reductivist interpretation that depicts the whole sector as an ‘undifferentiated evil’, which ends up creating a strawman to be blindly attacked without noticing the subtlety of concrete measures. This is even more relevant considering that the main instrument deployed by farmers and authorities is not direct confrontation, but lasting indifference, which cannot be counteracted with more indifference from grassroots organisations. The more the differences are preyed upon, there is a mirage of growing sameness, despite abject injustices and inequalities. Hegel (Citation2010, 179) argues that ‘negation is at the same time relation, difference, positedness, being-mediated.’ Difference is thus far from static or given in advance, but has to be reconciled with what seems to be the same (identity). The ontological sequence is being in itself, then the sphere of difference, and finally the return from difference to a relation with the self through the other ultimately, each is ‘the other’s own other’ (183). This movement entails the passage into another and the re-entering into the self as the same that is different. More than anything else, the trajectory of indigenous peoples demonstrates the deep cluster of forces within difference; they epitomise the maximum individuality because of their ethnicity and existential attachments to particular places, and at the same time embody the long-term elements of survival and survivability amidst capitalist disruption. The unique struggle of each indigenous society is the embodied proof of the limits and mounting insufficiencies of totalising socio-economic institutions. Indigenous peoples are holders of acute differences who need to remain different in order to be part of, and unsettle, the universal that insists on discriminating against them. In the words of Hegel (Citation1977, 182), Spirit (as the development of reason, the unity of being and thought) ‘behaves negatively towards itself as an individuality’ but also acts ‘negatively towards itself as a universal being.’

The coordinate endeavour to reduce the Guarani-Kaiowa to an indeterminate proletarian condition (that is, treated as generic members of the working class or the peasantry) has, among other consequences, the dialectical revitalisation of their sense of indigeneity. Despite the ideologised normalisation of difference by agribusiness, imposed socio-economic relations never managed to completely erase the strong self-identification markers accumulated and reworked over many centuries. The Guarani-Kaiowa are different from other segments of the working class, but the more they see, and are seen, as different, the more immersed they become in the subalternity of the rest of the dispossessed population. By the same token, the identification of indigenous populations as both members of the vast working class and of unique ethnic groups has major political consequences (another part of the negation of the negation) in terms of poor-poor alliances that, if properly carried out, can fiercely challenge politico-economic trends and the property claims of agribusiness farmers. The indigenous question is, first of all, a profound ethnoclass issue and the way out depends on recognising what is unique and what is common in indigenous lives and demands. The ethnoclass features of the Guarani-Kaiowa have been pursued and instrumentalised by the state according to the interests of conquerors and setters, on the other hand, however, it is what has allowed them to resist and mobilise forces against sustained socio-spatial aggression. Unique controversies in the centre of South America are also fundamentally associated with the search for more inclusive and democratic paths for national and global societies.

In the early decades of the twenty-first century, the ‘indigenous question’ in Brazil and around the world is part of the debate about the meaning of a neo—or true-communism or communitarianism, which involves not just the redistribution and collectivisation of wealth and the means of production (which are important), but overcoming the reproduction of inequality and the celebration of differences and commonalities. Their creative and ambitious mobilisation turns to be a reaction to the vicious handling of their differences towards the reappropriation of the world ‘on their own terms.’ The emblematic, and risky, choice of the Guarani-Kaiowa, in particular, has been the coordinated retaking [retomada] of their legitimate lands, bypassing spurious legal procedures that only serve to maintain farcical ‘indigenist policies.’ Nonetheless, the meaning of the retomadas is much deeper than the immediate, indispensable recovery of separated arears that were lost to agribusiness, but it is really part of the recovery of the entire Guarani-Kaiowa land (or as much as politically possible) that was grabbed by successive invading forces. Difference is their departure point and their long-term horizon. Overall, the socio-spatial experience of the Guarani-Kaiowa and of hundreds of other indigenous peoples around the planet vividly demonstrates the importance of critically and dialectically thinking about, and in relation to, multiple forms of difference.

Acknowledgement

The author acknowledges and is very grateful for the support received from the UK-Arts and Humanities Research Council (project: “Challenges and Risks Faced by Indigenous Peoples in Today's Brazil: Unpacking Vulnerability and Multiple Reactions”; grant: AH/T008644/1). Very special thanks also to the indigenous students and academics at the Federal University of the Great Dourados (UFGD) and to the members of the indigenous communities contacted during and after the research.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

References

- Abazari, A. 2020. Hegel’s Ontology of Power: The Structure of Social Domination in Capitalism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Badiou, A. 2012. Philosophy for Militants. London and New York: Verso.

- Bauman, Z. 2017. Retrotopia. Cambridge: Polity.

- Benites, T. 2014. “Recuperação dos Territórios Tradicionais Guarani-Kaiowá. Crónica das Táticas e Estratégias.” Journal de la Société des Américanistes 100 (2): 229–240. https://doi.org/10.4000/jsa.14022

- Brand, A. J. 2004. “Os Complexos Caminhos da Luta Pela Terra Entre os Kaiowá e Guarani no MS.” Tellus 6: 137–150.

- Bresser-Pereira, L. C. 2017. “After Financial-Rentier Capitalism, Structural Change in Sight?” Novos Estudos CEBRAP 36 (1): 137–152. https://doi.org/10.25091/S0101-3300201700010007

- Chamorro, G. 2015. História Kaiowá: Das Origens aos Desafios Contemporâneos. São Bernardo do Campo: Nhanduti.

- CPT. 2023. Conflitos no Campo Brasil 2022. Goiânia: Centro de Documentação Dom Tomás Balduíno/ Pastoral Land Commission. (CPT).

- Croce, B. 1915[1912]. What is Living and What is Dead of the Philosophy of Hegel. London: Macmillan and Co.

- Fukuyama, F. 1992. The End of History and the Last Man. London: Hamish Hamilton.

- Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2020. “Reading for Difference in the Archives of Tropical Geography: Imagining an(Other) Economic Geography for Beyond the Anthropocene.” Antipode 52 (1): 12–35. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12594

- Hegel, G. W. F. 1977[1807]. Phenomenology of Spirit. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hegel, G. W. F. 2010[1830]. Encyclopedia of the Philosophical Sciences in Basic Outline. Part I: Science of Logic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Heidegger, M. 1988. Hegel’s Phenomenology of Spirit. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- INA. 2022. Fundação Anti-Indígena: Um Retrato da Funai sob o Governo Bolsonaro. Brasília: INA/INESC.

- Ioris, A. A. R. 2017. “Places of Agribusiness: Displacement, Replacement, and Misplacement in Mato Grosso, Brazil.” Geographical Review 107 (3): 452–475. https://doi.org/10.1111/gere.12222

- Ioris, A. A. R. 2018. “Place-making at the Frontier of Brazilian Agribusiness.” GeoJournal 83 (1): 61–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10708-016-9754-7

- Ioris, A. A. R. 2020. “Ontological Politics and the Struggle for the Guarani-Kaiowa World.” Space and Polity 24 (3): 382–400. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562576.2020.1814727

- Ioris, A. A. R. 2021. Kaiowcide: Living Through the Guarani-Kaiowa Genocide. Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Ioris, A. A. R. 2022. “Indigenous Peoples, Land-Based Disputes and Strategies of Socio-Spatial Resistance at Agricultural Frontiers.” Ethnopolitics 21 (3): 278–298. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2020.1770463

- Jameson, F. 2017. The Hegel Variations: On the Phenomenology of Spirit. London: Verso.

- Jonsson, H. R. 2022. “Losing the Remote: Exploring the Thai Social Order with the Early and Late Hanks.” Anthropological Forum 32 (1): 76–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2022.2049698

- Katz, C. 2009. “Social Systems: Thinking About Society, Identity, Power and Resistance.” In Key Concepts in Geography, edited by N. J. Clifford, S. L. Holloway, S. P. Rice, and G. Valentine, 236–250. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Lefebvre, H. 1991. The Production of Space. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing.

- Luhmann, N. 1982. The Differentiation of Society. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mariátegui, J. C. 2011. An Anthology. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- McGowan, T. 2019. Emancipation After Hegel: Achieving a Contradictory Revolution. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Mura, F. 2019. À Procura do “Bom Viver”: Território, Tradição de Conhecimento e Ecologia Doméstica Entre os Kaiowa. Rio de Janeiro: Associação Brasileira de Antropologia.

- Nancy, J.-L. 2018[1997]. Hegel, l’Inquiétude du Négatif. Paris: Galilé.

- Pompeia, C. 2020. “‘Agro é Tudo’: Simulações no Aparato de Legitimação do Agronegócio.” Horizontes Antropológicos 26, 56: 195–224. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0104-71832020000100009

- Pulido, L. 2002. “Race, Class and Political Activism: Black, Chicana/o, and Japanese American Leftists in Southern California, 1968-1978.” Antipode 34 (4): 762–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8330.00268

- Qian, J., and L. Wei. 2020. “Development at the Edge of Difference: Rethinking Capital and Market Relations from Lugu Lake, Southwest China.” Antipode 52 (1): 246–269. https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12590

- Rockmore, T. 1992. Before and After Hegel: A Historical Introduction to Hegel’s Thought. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Thompson, E. P. 1966. The Making of the English Working Class. New York: Vintage Books.

- Žižek, S. 2013. Less Than Nothing: Hegel and the Shadow of Dialectical Materialism. London: Verso.