ABSTRACT

In this article I explore the organisation of practices of vernacular cosmopolitanism in the city of Buenos Aires. The starting point is a series of festivals and activities organised by the city government to promote and celebrate its cosmopolitanism. I then explore the spaces where they take place, and the monuments built by immigrant communities that populate the urban landscape. I read these in relationship to the ideological making of the Argentine nation and state, showing that the vernacular cosmopolitanism being promoted is exclusionary in character, and Eurocentric in orientation. Furthermore, I suggest that this form of exclusionary cosmopolitanism has an ideological affinity and shared genealogy with the settler colonialism that underpins Argentine nation building and its territorial state consolidation. I also show that in these celebrations of diversity, the government of the city of Buenos Aires strategically uses immigrant institutions and their networks, subsuming their particularity and multiplicity to that of the city and the nation.

Cosmopolitanism and Its Limits

It is the 6th of September 2014, the ‘Festival of collectivities’ is organised to celebrate national immigrants’ day (on September 4th). A stage has been set up as the centrepiece of attention at one end of Plaza Facundo Quiroga. The backdrop states ‘Buenos Aires Celebrates’ and the flags of the city and of Argentina permanently flank the stage. There is a full day programme of music, dance, and stage performances. It includes a dance/martial arts performance from Japan, a Falun Dafa display from China, flying Lithuanians, Brazilian samba, nimble footed Basques, variations on the orientalist belly dance theme, elegant and delicate moving Panamanians, and Italian tarantella among many others. A variety of traditional costumes, headwear and hair styling can be seen not just on stage, but amongst the audience too.

A perimeter has been built with the tents allocated to the different collectivities. From them, typical food is sold by volunteers wearing traditional costumes. Hungarians offer goulash, the Dutch poffertjes and croquettes, Austrians display a picture of Arnold Schwarzenegger, a placard of the movie ‘The sound of music’ and sell pork sandwiches and cakes, the Spaniards paella, while the Greeks, Mexicans, Nigerians, Lebanese, Syrians, and the Arab League offer variations of meat cooked on a rotating spindle. Haitians sell fruit smoothies, Paraguayans chipa, while the Jewish collectivity offers leikaj, right next to the Volga Germans who are roasting pork legs and trotters. The Irish display a poster of the Irish-born founder of the Argentine Navy, Guillermo Brown, and sell green leprechaun hats and ties while the Scots offer a variety of sweets. The English are nowhere to be seen as they usually abstain from the ‘collectivities’ paradigm and these type of activities, preferring to define themselves as ‘expats’. The atmosphere is jovial and people seem to be enjoying a good time trying different dishes, and entertained with the performances.

These types of practices are usually taken as expressions of vernacular cosmopolitanism (Werbner Citation2006) or the ‘happy face’ of cultural cosmopolitanism (Hannerz Citation2006, 14), highlighting the various ways in which the openness to the ‘other’ can take form, and praising the coexistence, hybridity, creativity and tolerance they display and contribute to build. This expression of cosmopolitanism is also the intended outcome that the government of the city of Buenos Aires, which organises and facilitates this festival, as well as a broad range of celebrations of immigrant diversity. For many of the participants, it presents an opportunity to showcase and feel proud of their cultural ancestry, coexisting simultaneously with their ‘Argentinian’ or ‘Porteño’Footnote1 sense of identity. However, as Craig Calhoun warns ‘contemporary cosmopolitanism commonly reflects the experience and perspective of elites and obscures the social foundations on which that experience and perspective rests’ (Citation2008, 441). This article is concerned with shedding light on these obscured social foundations of vernacular cosmopolitanisms.

Pnina Werbner rightly argues for the need to recognise, understand and theorise the ‘dialectics of tolerance and intolerance, of conviviality and hospitality towards strangers or anti-immigrant, racist and ethnicist aggression’ (Citation2015, 584). Similarly, ‘anti-cosmopolitan’ dynamics (Werbner Citation2015, 576), the ‘worried face’ of political cosmopolitanisms (Hannerz Citation2006, 14) or in the extreme, provide the cultural aggregations that facilitate genocide (Rapport Citation2019) are usually attributed to different actors and their ethical stances rather than to those of cosmopolitans (Werbner Citation2015, 571), thus externalising intolerance, and by definition excluding the exclusionary dynamics from analysis. Here I internalise the exclusionary dynamics by focusing on the extension and limits to the openness to others. Looking only at those celebrated runs the risk of selection bias. The challenge is then to move beyond the celebratory and focus on the limits of concrete vernacular cosmopolitanism, searching for those that have not been included in the paradigm to be celebrated. I use the term exclusionary cosmopolitanism to capture the tension of this janus-faced phenomenon, to act as a reminder that the self-congratulatory mantle of cosmopolitanism is predicated on an original exclusion that needs to be examined.

What concrete, vernacular cosmopolitanisms must deal with that idealist, philosophical and universalist cosmopolitan projects like Immanuel Kant’s do not, is with the limits to the openness to the other. Openness and closure are oriented towards particular others, but which kind of others cannot be assumed. Indeed, not doing so might create a misleading picture where the celebration of immigrant diversity is automatically identified as an unproblematic expression of cosmopolitanism, and this is particularly so under conditions of settler colonialism.

I therefore delve into the genesis of the social classifications that manage the openness and closure to different others, part of Calhoun’s ‘obscured social foundations’ (Citation2008, 441). States are powerful generators of these classifications, and particularly so through nation-building processes (the openness and closure depend on the simultaneous ‘imagined’ and ‘limited’ qualities of nations, Anderson Citation1990). These classifications also determine the relations and attitudes to be had towards the different others, providing the necessary building blocks and the hierarchies between them, upon which vernacular cosmopolitanism can simultaneously celebrate and exclude. These are then maintained through everyday practices and representations achieving part of the taken for granted fabric of social life (Billig Citation1995). In addition, in settler colonialist societies there is a triangular articulation of relations of agencies: colonised indigenous populations, colonising settlers, and exogenous others (Veracini Citation2011b, 1). Access to territoritory being the main motivation, ‘settler colonialism destroys to replace’ (Wolfe Citation2006, 388) one population with another. This is accompanied by suitable ideological apparatus (usually consolidated in nationalist self-image) that legitimises this social structure and allows it to continue in time. Therefore, Argentine vernacular cosmopolitanism as expressed in Buenos Aires, should be seen in relationship with this settler colonialist matrix.

I explore the organisation of practices of vernacular cosmopolitanism in the city of Buenos Aires. I show that the vernacular cosmopolitanism being promoted is exclusionary in character, and Eurocentric in orientation. This is expressed through the celebration of the immigrants (mostly European), and the invisibilization of indigeneity. I suggest that this form of exclusionary cosmopolitanism has an ideological affinity and shared genealogy with the settler colonialism that underpins Argentine nation building and its territorial state consolidation. My argument in other words, is that what appears to be a cosmopolitan attitude towards immigration, is rather the product of the positive relation between ‘colonising settlers’ and ‘exogenous others’ (who are deemed assimilable into the first), while simultaneously hiding the other significant relationship, between ‘colonising settlers’ who deterritorialize and disavow the ‘colonised indigenous populations’. I also show that while on the one hand the government of the city of Buenos Aires, appropriates and uses immigrant institutions and their networks, subsuming their particularity and multiplicity to that of the city and the nation while, on the other, the networking potential of indigeneity is negated.

This article is based on one years’ ethnographic fieldwork carried out during 2014 together with Tanja Plasil. We were interested to see what had happened to the descendants of late nineteenth and early twentieth century immigrants from the Levant to Argentina a hundred years after their arrival. We did around a hundred semi-structured inverviews with collectivity members as well as with different relevant public office-holders (including bureaucrats, law-makers, judges, and diplomats at different levels of city, provincial and national level). Having spread throughout the country, we followed the Levantine’s networks throughout the provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, San Juan, Mendoza, Tucumán, Salta, Santiago del Estero and Santa Fe. We participated with them in some of the events organised by themselves, or by the governments of the cities of Buenos Aires and Rosario. Doing so made us realise they were part of a paradigm which in Argentina is known as colectividades (collectivities). This induced the shift of focus from an individual group to the common practices and networks they are entangled in. Furthermore, the paradigm of collectivities did not exhaust the paradigm of ‘otherness’; it only included those to be celebrated. The largest of the collectives invisibilized consists of indigenous groups.Footnote2 Instead of inheriting the exclusions I incorporate them into the analysis as indicators of the limits of exclusionary cosmopolitanism. This article is also informed by cartographic and first hand observational analysis that focused on the representation or non-representation of different groups on the urban landscape. It was complemented with textual analysis of legislation, written primary and secondary sources, as well as of organigrams that allowed to track the differential treatment of collectives at different levels.

The remainder of the article is divided in four sections. The next one ‘The Argentines descend from the ships’ focuses on the genesis of the social classification of otherness in Argentina. It brings together a variety of domains, from the formation of a national ideology, law, policy and popular culture. I highlight the centrality of territory, immigration and eurocentrism in detriment of indigeneity, thus establishing the genealogical and ideological affinity with settler colonialism. I then move to examine the formation of immigrant institutions and networks in Buenos Aires, highlighting their different and changing functions, and their becoming the building blocks of cosmopolitan diversity, ready to be celebrated and subsumed to the nation.

I then focus on two registers where exclusionary cosmopolitanism manifests itself in contemporary everyday life in Buenos Aires. One on the temporally bound state-organised and promoted festivals and cultural performances which shows how the government appropriates and subsumes the immigrant networks to its own purposes, while simultaneously excluding and invisibilizing indigeneity. The other, with an apparent higher degree of temporal and historical inertia: monuments and urban toponymy which inscribe in the landscape a pre-selection of events, names, dates and places worthy of remembrance, and by implication those that do not. I also point to recent signs that indicate a shift towards a policy of recognition (hopefully leading to redress) of the foundational genocide and subsequent invisibilization of indigeneity.

‘The Argentines Descend from the Ships'

The dynamics of settler colonialism, that epitomise exclusionary cosmopolitanism in the making of Argentine, are condensed in a popular phrase ‘The Mexicans descend from the Aztecs, the Peruvians descend from the Incas, while the Argentines descend from the ships’. This phrase was repeated in June 2021, during a meeting with members of the Spanish government and potential investors, by the then Argentine president Alberto Fernandez, after explicitly stating he was an ‘Europeanist’. This phrase (with variations) has been attributed in Argentina at different times to Mexican authors Octavio Paz and Carlos Fuentes, as well as to Argentine novelist Julio Cortázar, to the Brazilian anthropologist Darcy RibeiroFootnote3, while a variation found its way into a popular song by Litto Nebbia. A strong reaction ensued in the public sphere rightly highlighting its discriminatory and invisibilizatory implications. The presidential twitter account apologised for any offenses and for ‘invisibilizing’, however, insisted on the image of the ships and continued stressing how five million immigrants lived side by side (conviviendo) with the indigenous populations, a diversity that Argentina should be proud of.

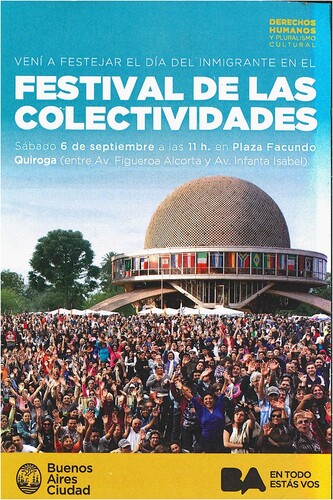

The phrase received a space-age twist in the promotional leaflet for the ‘Festival of Collectivities’ commissioned by the government of the city of Buenos Aires. The Galileo Galilei Municipal Planetarium is in the background, with its three long curved concrete legs supporting a hollow concrete ball with a horizontal glass ring that make it look like a recently landed alien spaceship. The glass ring is clad in flags, and a multitude of people in front, as if they had just come off-board. They are waving their arms, in a festive mood as if joyfully greeting the photographer. A ‘polis’ arrived from the ‘cosmos’ ().

Figure 1. Promotional leaflet to the ‘Festival of Collectivities’ Government of the City of Buenos Aires.

The phrase is the inheritor of almost two centuries of nation making, and state consolidating processes. It decouples Argentina from its Latin American context by the elimination of indigenous peoples from the body of its nation, as well as simultaneously expressing a Eurocentric orientation. It further shows what the dominant Argentine nation-making ideology tries to hide while simultaneously taking as a point of pride: the exclusion of indigeneity and non-Europeanness in the making of the nation. This is precisely what Veracini (Citation2011a, 3) indicates as one of the significant distinguishing feature of settler colonialism: attempting to self-supersede itself in contrast with colonialism that attempts to continue the colonial relation.

State and nation making processes generate and depend on, a variety of symbolic forms that contribute to its imagination, and maintenace in everyday life. They in turn become normalised and taken for granted or even banalized in the sense proposed by Michael Billig (Citation1995). The guiding fictions in the invention of Argentina (Shumway Citation1991) articulate the relationship between types of populations to be incorporated and celebrated, from those to be excluded, invisibilized, or eliminated. One of the diacritics between colonial and settler colonial formations is the recurring need in the latter to ‘disavow the presence of indigenous “others”’ (Veracini Citation2011a, 2) With one hand promoting a cosmopolitan attitute to incorporate overseas strangers into the imagined body of the nation (openness and acceptance of the other is often taken as the hallmark of cosmopolitanism Hannerz Citation2010, 89). Meanwhile, with the other hand, it invisibilizes the genocides involved in both Spanish colonisation, as well the post-independence territorial consolidation of the Argentine state. This last one predicated on a variation of the terra nullius theme, and the closure towards indigenous populations, excluding them from the imagination of the Argentine nation (Briones and Delrio Citation2007; Brudney Citation2019; Delrio et al. Citation2010; Escolar Citation2007; Gordillo Citation2016, Citation2020; Gordillo and Hirsch Citation2003). We can see the interaction of the ‘imagined’ and ‘limited’ characteristics of nations (Anderson Citation1990) manifesting as an exclusionary cosmopolitanism and leading to the formation of an imagined ‘White Argentina’ (Gordillo Citation2016, Citation2020).

Chthonic metaphors are the principle symbolic forms of settler colonialism in the making of Argentina. The name Argentina derives linguistically from the Latin word for silver, and emerged from the name given by the Spanish colonisers to the river that bathes the coasts of its current capital: Río de la Plata (the river of silver). The name expressing the hope in the coloniser’s mind, while premonitorily pointing to the earth and its potential to generate metaphors that will become dominant in the future invention of the nation. The consolidation of its national state and its territorialisation went hand in hand with the construction of its own source of legitimacy.

The transformation of the Viceroyalty of the Rio de la Plata, into what today is known as Argentina was a long and not very peaceful process. With the declaration of independence in 1816 (and the wars of independence not yet over) a period of civil wars between the local warlords (caudillos) ensued (primarily about the definition of the relation between Buenos Aires and the other provinces). The local intellectuals of the post-revolution and post-civil war period, the so-called Generation of 1837 (Halperín Donghi Citation1982; Terán Citation2015), set out to prepare the guiding fictions that would realise, mostly through state institutions, Argentina and the Argentines (for an English language analysis of this process see Shumway Citation1991). As I will show, these guiding fictions were of a settler colonialist orientation, and this orientation was then translated through law, policy, and public culture.

Land and territory became central in this quest, providing a universe of earth-centred guiding ideas and metaphors that serve to legitimize a multiplicity of actions and policies. One of these guiding ideas was ‘Gobernar es poblar’ (to govern is to populate) coined by Juan Bautista Alberdi (Citation1853) in his precursor to the Argentine Constitution of 1853. Furthermore, the preamble of said constitution states three main addressees: ‘us’, ‘our posterity’, and ‘men from all over the world who wish to inhabit the Argentine soil’. This point has been maintained throughout the different amendments and is still current. The foundational text brings together the dilemma of the imagination of the ‘us’ in the nation, as well as the anticipated future immigration, together with the centrality of the ‘soil’ as the cohesive factor. The territory, ‘Argentine soil’ is available for populating, implying its emptiness. Furthermore, article 25 made explicit the preference for European immigration.

These anchored the laws and campaigns for the promotion of European immigration and colonisation (República Argentina Congreso Nacional Citation1876), thus providing the framework for the cosmopolitan openness to a particular type of ‘other’. The closure will come shortly later, as this idea also became the guiding principle of the ‘Conquista del Desierto’ (Conquest of the Desert, 1878–1884). This was aimed at the territorial consolidation through military means by the new Argentine state of territories the Spaniards had not managed to colonise in the Pampas and Patagonia, making them suitable for European colonisation. This involved different degrees of pacification, forced settlement, invisibilization, foreignizing, and genocide of the indigenous populations (Briones and Delrio Citation2007; Brudney Citation2019; Delrio et al. Citation2018; Quijada Citation2003). The name of this campaign deserves some attention. In Spanish, ‘desierto’ refers to absence of population, giving the idea of an empty territory: terra nullius. Paradoxically, a heavily armed military operation was needed to deal with the (implied as non-existing) inhabitants of said desert. The campaign name already invisibilizes the other, and by the lack of a victim, invisibilizes them once again through the violence exerted. Furthermore, read retrospectively, in its apparent success, it denotes the final extermination of the indigenous population. The Conquest of the Desert, in addition, produced a desert, invisibilizing its survivors.

The terrain was thus prepared for settlement of European immigrants, and the invention of the Argentine nation that would populate it: ‘A nation for the Argentine Desert’ as aptly put by Tulio Halperín Donghi (Citation1982). Then the land was redistributed among the oligarchy and the military in return for services paid to the nation. ‘Cultivar el suelo es servir a la patria’ (to cultivate the soil is to serve the fatherland) is the motto of the ‘Sociedad Rural Argentina’, the association of large agricultural owners, those that most benefited from the conquest. Paraphrasing Patrick Wolfe (Citation1999), the event of the military conquest and genocide was then extended to the present as a structure of continuous practices of exclusion, accompanied and supported by suitable ideologies and symbolisms.

The earthly metaphors are also manifested in the legal domain through jus solis. Argentine citizenship is obtained by virtue of being born on Argentine territory regardless of genealogy, thus those born out of immigrant parents automatically become Argentines. However, another paradox lies here as jus solis has been enforced for the facilitation of the rooting of settlers, while roots that predated the Spanish conquest had to be eradicated and invisibilized as making claims on principles of indigeneity can be construed as anti-Argentine (see Quijada Citation2003).

The Argentine state openness to settlers was manifested in a variety of measures taken to secure immigrants. Echoing Kantian eurocentrism (but not its universalist cosmopolitanism), Argentina would be built of immigration, preferably of white, northern Europeans who were seen as the only ones able to ‘civilise’ the country (Alberdi Citation1853; Halperín Donghi Citation1982; Shumway Citation1991). From the mid nineteenth century the state machinery was put in motion to secure those immigrants – with varying degrees of efficacy – (and started to give shape to a particular vernacular cosmopolitanism) casting a network throughout Europe. Recruiting agents were sent to Europe, passages paid, immigrant hotels built and offered free of charge, as was transport to the provinces, where settlement in agricultural colonies was preferred by the government. Although northern European stock was repeatedly voiced as a preference by the different authorities and politicians, they had to make do with Italians, Spaniards, and the different persecuted populations of the Russian and Ottoman empires (Alberdi Citation1853; Alsina Citation1900, Citation1910; Shumway Citation1991). Rates of acceptance at the port were high, full citizenship offered within two years of residence, or less if recommended by an authority. The 1895 census showed that over 25% of the population was foreign born, by 1914 this number would climb to 30%. Due to jus solis, the descendants of immigrants became Argentine citizens, and the state machinery through public education and military services attempted to transform them into Argentine nationals. The openness of the network towards European settlers was therefore cast, and the descendants of this catch were turned into Argentine citizens via jus solis, and national identity inculcated through state institutions, primarily through the schooling system.

Settler colonialism underpins different guiding fictions of Argentina, informing a variety of concrete cultural, legal and policy practices as well as expressing in a variety of chthonic metaphors in popular culture. In its exclusion of indigeneity, while simultaneously privileging immigrant settlers as suitable others to be incorporated into the territory and the body of the nation, it provides the two basic divergent orientations that form the limit of the Argentine vernacular exclusionary cosmopolitanism.

Collectivities and Their Networks

What could be called the paradigm of collectivities results from articulating the different networks of each individual collectivity. In Argentina a colectividad (collectivity) is used to refer to any kind of group (national, regional, religious, etc) that organises itself to maintain their culture or to promote their interests (although being descendent of immigrants is often implicit). Most collectivities have a variety of institutions that interact on a multiplicity of spheres, a collection of networks, where each club, union or cultural or association of origin can be seen as a node or subnode that articulates the linkages between their members and between different nodes in the network at local, national and trans-statal levels.

These associations and networks were formed by the immigrant themselves for providing mutual help and to overcome the inadequacies of state institutions. These were both the product and enabler of what Granovetter (Citation1973) called ‘weak ties’ facilitating newly arrived immigrants with socialisation, job finding, and other services, including establishing formal links with the different local authorities as well as their home governments. They cooperated and established relationships with different local governmental levels to establish themselves as legal entities, or for official recognition of the study programmes of their schools. Sometimes being the host of ‘honorary consuls’ if they were lacking in the area, or even proto-embassies like the Casa Libanesa in Buenos Aires. As local immigrant communities became more established and grew some managed to build their own schools, hospitals, temples, and maintained their own sections in cemeteries. They became central nodes for social life as well as linking with places of origin.

However, these associations changed in character as their members became assimilated into society and some of their original functions became obsolete or covered by the national and provincial states or labour unions (like health, education, pension and cemeteries). Their focus is now on the transmission of culture and traditions of origin (usually through food, dance, clothing, language and religion) to the next generations, the relation with their homelands, and to manage the public image of their constituency in the public sphere (Cañás Bottos and Plasil Citation2017, Citation2021, Citation2022, Citation2023). For example the lobbying of the provincial or national legislature for the recognition of a particular date to celebrate some aspect of their ancestry (like the Day of Arab Culture in the province of Tucuman, or the National Day of the Lebanese immigrant) or to mark their public presence in the naming of a park, street or avenue, or the building of a monument, like the recent erection of a bust of Khalil Ghibran (the Lebanese poet an painter) in Buenos Aires. In short, these networks of institutions shifted from being grassroots mutual help associations, concerned with helping newly arrived immigrants in a new country, to becoming public actors in the reproduction and display in the public sphere of their ancestral home cultures. In this way, the paradigm of collectivities provides a ready-made palette of organised immigrant cultural diversity, a multiplicity of others ready to be celebrated and mobilised. What different governmental organisations like the city of Buenos Aires do, is the co-ordination and articulation of the networks of different degrees of formalisation and institutionalisation to then subsume their diversity to enrich that of the imagined Argentine nation.

Celebrating Immigrants

The government of major cities with cosmopolitan aspirations in Argentina showcase their cultural diversity through a variety of actions, including festivals, publications, and memorialisation in the public space. For the different festivals, the municipality provides the space, promotion, stage, sound, tents for the stands, and general logistics. Their organisation requires the articulation of the multiple dispersed networks that each immigrant association is a node of.

Different events are organised by the government of the city of Buenos Aires to celebrate the different collectivities. Yearly events like ‘Festival of collectivities’ (on the weekend next to the ‘National Immigrants Day’), ‘Beauty Pageant of collectivities’, ‘Cooking competition of the collectivities’ and the ‘Fatherland Festival’. There is also a festival series which is run almost every weekend ‘Buenos Aires Celebrates … ’. followed by the name of the relevant collectivity. The list of collectivities that were celebrated in Buenos Aires at the time of fieldwork included sixteen currently existing independent nation statesFootnote4; four sub/supra-nation-state entities (Basque Country, Scotland, Calabria and Galicia); three celebrations acting as mediating references for their groups (St. Patricks – Ireland, Kosher – Jews, Fiesta de la Luna-China and Taiwan) and one collective aggregate like ‘Comunidad Afro’. This shows that the paradigm of collectivities subsumes different types of groupings; what they all have in common is origins beyond the territorial boundaries of Argentina.

The city provides a series of heterogeneous spaces with different meanings as potential stages for public celebrations and performances. Most of the festivals mentioned take place in Avenida de Mayo, which links the Presidential Palace with the National Congress. It is a main public stage of the city, used for demonstrations as well as official parades. An elegant boulevard (originally named ‘De los Españoles’) displaying the finest architecture at the time of the golden days of Buenos Aires. Celebrations at the Avenida de Mayo follow a common pattern: the street is closed for traffic and lined with tents along the pavements. Flags and banners decorate the luminaries, and a main stage is built with its back to the presidential palace and facing congress. In short, for the celebration of immigrant diversity, the city makes available the country’s most important and visible urban stage.

Combined with its control of public space, permits and resources, the municipality becomes a central node of coordination and management of a network of immigrant associations. The process of governmental recognition and selection of which associations are considered the representative is delicate, and demands constant negotiation due to the multiple entities involved, and not rarely results in disputes to be the one articulating with the state. The bottom line for the collectivities to participate in the celebrations is to have formal juridical existence (usually as a non-profit NGO). In the festivals where an individual collective is celebrated at a time there is a wider availability of stands to distribute, which makes it possible for multiple institutions of the same collectivity to take part, thus allowing to show their internal diversity.

A very significant celebration, the ‘Festival of the Fatherland’ takes place on the 25th of May, the anniversary of the 1810 May Revolution. The collectivities are congregated to celebrate the fatherland (note the singular). However, that celebrated fatherland is Argentina. They thus cease to represent national entities on the global scenario and become subsumed units providing cultural diversity to the Argentine Nation.

As part of the same programme of promotion of diversity, the Municipality of Buenos Aires has published a series of books on (and with the collaboration of) the different colelctivities. On its website, it portrays locally produced books on the Shoa, Armenian Genocide, and Holodomor (Ukrainian Genocide) as the foundational conditions of migratory flows and portraying the city of Buenos Aires (and Argentina) as a haven from those atrocities. However, there is total silence regarding the foundational genocide of indigenous peoples during the Spanish colonisation and ensuing Argentine territorial consolidation.

The limits of the concrete, vernacular cosmopolitanism is reflected in both, policies and the bureaucratic organisation of the municipality. On a question about the place of indigenous peoples in the celebrations of the city to the director of the area responsible he answered ‘For us to invite them would be a lack of respect towards them as we would be implying that they are foreign’. Whereas at the beginning of the interview the foreignness of collectivities was downplayed to highlight their contribution to the diversity of Buenos Aires, making them worthy of celebration for producing a cosmopolitan city ‘only comparable to New York’, the diversity provided by the indigenous populations would not be celebrated because it was not foreign. A few public actions of support for indigenous peoples were mentioned, like providing portable toilets for some of their demonstrations and contributing with the printing of leaflets, but it was considered extraneous to the area of inference of his office. He then pointed to the relevant office that at the time dealt with indigenous peoples, but no celebrations were organised by them. The organigram of the government of the city of Buenos Aires at the time of fieldwork showed that under the vice chief of government is the ‘Human Rights and Cultural Pluralism’ section. Directly under it are the ‘Collectivities’ and ‘Coexistence in Diversity’ sub-sections. Indigenous populations appear subsumed under the latter (on a lower hierarchical level than ‘Collectivities’), together with other target groups in need of assistance next to sexual diversity, work placement assistance for transgendered persons, and a program for rehabilitation of former prisoners. Indigenous communities were not to be celebrated and actions were not oriented towards collectives but individuals. Although this doing away with collective categories resembles in form individualist approaches to cosmopolitanism (Rapport Citation2012, Citation2015, Citation2019) having instead invisibilizatory and exclusionary (and therefore anti-cosmopolitan) consequences.

We have here an ideology that operates on the social classification and hierarchization of social groups as well as being translated into the principles of governmental organisation and action. First, indigenous cultures and traditions do not deserve to be celebrated by the city as collectives contributing to its cultural diversity. Second, that actions are targeted at individuals, and not at groups, conceals the fact that belonging to a particular social classification is the original cause for need of assistance as well as stigmatising indigeneity when used as reason for requiring said assistance. Although cultural belonging is a source of discrimination, it cannot be claimed for purposes of restoration. This is continuation in the present of what Mónica Quijada (Citation2003) identified as the solution found to the indigenous dilemma in nineteenth century Argentina; the incorporation of indigenous peoples into the citizenry was to be done as individuals, not as practitioners of indigenous cultures. Only in the 2001 a question about indigenous belonging was included in the National Census. Becoming Argentine citizens meant incorporation into the citizenry without distinction (also highlighting how in settler colonialist societies the conquest is not an event but becomes a structure). In terms of this special issue (see Cañás Bottos, Simonsen, Chen Citation2024), we could say that the networking potential of indigeneity is denied while that of immigrant populations is empowered and celebrated (although also appropriated and subsumed).

The practice of this vernacular exclusionary cosmopolitanism through the celebrations of immigrant diversity are made possible via a double capture: classificatory and organisational. Classificatory, by appropriating and assimilating cultural differences worthy of celebration and subsuming them to the Argentine nation. The ‘national’ symbols espoused by the members of the collectivity thus cease to be on the ‘international’ stage but belonging on the paradigm of collectivities, subsumed to that of the Argentine nation.Footnote5 Organisational, the government of the city taps and mobilises pre-existing networks to organise the different celebrations. This classificatory and organisational capture then allows the celebration of the Argentine fatherland.

The limits of exclusionary cosmopolitanism have been clearly delineated and enacted. First by excluding indigeneity, second by subsuming and displaying immigrant diversity. Exclusion, subsumption, and celebration are all carried out simultaneously, through the same bundle of actions and by the same actors.

Inscribing Cosmopolitanism on the Urban Landscape

The urban landscape is another register where the exclusionary cosmopolitanism is manifested, and in doing so, contributing to perpetuate a particular self-representation. Toponimy, monuments and memorials inscribe in public consciousness a selection of events, individuals, peoples, places, etc. What is worthy of inscription, implies also entities to be excluded, without the exclusion having to be made explicit.

The urban landscape is another stage where cosmopolitanism can be displayed, often becoming a battleground where different forces vie with each other for what is worthy of celebrating or memorialising and what not (cf Huyssen Citation2003). Different state and non-state actors like the collectivities are engaged in this process. Their materiality requires a considerable articulation and mobilisation of networks and resources (material, political, symbolic). Counterintuitively, despite their higher degree of temporal inertia the urban landscape is in constant change, and it mirrors changes in the limits of vernacular cosmopolitanism.

The ‘Festival of Collectivities’ takes place in a significant location: Plaza Facundo Quiroga, within the 3 de Febrero park complex. Comprising 360-hectares, the park is today a green, recreational buffer zone between the now densely populated neighbourhoods of Palermo and Belgrano and the city airport. Through its design, monuments, and toponymy this park complex condenses and expresses the victory of a Eurocentric civilizational model over barbarism in Argentina as well as its exclusionary cosmopolitanism.

The plaza Facundo Quiroga is named after a local provincial warlord (caudillo) from the civil wars period. His life was the inspiration to Domingo Faustino Sarmiento’s Facundo (one of the foundational texts in the invention of Argentina) (Citation[1845] 1998). For Sarmiento, Argentina oscillated between the principle of ‘civilisation and barbarism’ the former with origins in reason and Europe, the latter (of which Facundo was an embodiment) in the passions and the countryside, never ending plains, a sea without water that prevented setting roots and developing a rational outlook. The book was written while Sarmiento was in Chile in exile, as a critique of Juan Manuel de Rosas, the then governor of Buenos Aires, and his authoritarian regime, and from whom he was escaping.

Meanwhile, the ‘Parque 3 de Febrero’, owes its name in memory of the date of the battle of Caseros in which General Justo Jose de Urquiza beat the forces of Juan Manuel de Rosas in 1852. The lands were the property of Rosas and were expropriated. In 1875, during the presidency of Sarmiento, the lands were transformed into a park. Meanwhile the victor is memorialised with an equestrian statue crowning a roundabout. The park was re-designed in 1891, by Charles Jules Thays, a French landscape architect, who had become the director of the city’s Parks and Walkways. He also designed most of the large parks, plazas and green areas of the growing metropolis that wanted to style itself after Paris, the chosen civilizational model. In this way the park tells the history of Argentina as the victory of the forces of (European) civilisation.

The toponymy of the rest of the park is an exercise in world geography. Further east of the equestrian statue of Urquiza lies the Galileo Galilei municipal planetarium, flanked on the south-west by the Plaza República Arabe de Egipto, to its south lie the Plaza República Islámica de Irán and then Plaza Sicilia, which contains the Jardín Japonés, and its Shigaken Lake. To the east is Plaza Alemania, and then Plaza República del Perú. To the southwest of the planetarium, lies Plaza Holanda and to the west extend a series of parks dedicated to Haití, Serbia, Ecuador, Israel, Croatia, Mexico, El Salvador, the Russian Federation and the ‘Paseo de las Americas’. We can also find the Plaza de la Shoa, and just across it on Libertador Avenue, the King Fahd Cultural Center with its two mosques, just besides the Army Barracks. The US Embassy, next to the convention center of the Sociedad Rural Argentina (the landwoners’ association), and where the latter, the former Zoo (nowadays Ecoparque) and the botanical gardens meet, a Monument to Garibaldi, the hero of Italian unification crowning the roundabout on the middle of ‘Plaza Italia’. In addition, there is an assortment of small statues and monuments usually donated or lobbied for by individual immigrant associations or embassies, thus we find memorials to Mahatma Gandhi, Confucius, Khalil Gibran, and Taras Shevchenko among others. There is even a statue of Little Red Riding Hood and the Wolf. This glorification and performance to openness and cosmopolitanism is betrayed by one absence and invisibilization: I could not find a single trace of a reference to an indigenous population or personality. If allowed the hyperbole: the whole world is inscribed in this area except for indigeneity.

The different collectivities have actively participated in this cosmopolitan landscaping. The most notable are the collective actions that led to the celebration of Argentina’s centenary in 1910. Considerable monuments were donated by different collectivities and emplaced in significant points in the city. The Spanish collectivity contributed a 25 m tall monument with fountains representing the four regions of Argentina. It crowns the roundabout at the intersection of the Avenida Sarmiento (consisting of 6 lanes) and the Avenida del Libertador (with 11 lanes).

The German collectivity donated a monument with a fountain celebrating the place of German immigrants in the making of Argentine countryside (most of them Volga Germans) while the French presented one with a bronze bas relief depicting four historical scenes in the making of France and Argentina, crowned by the statue of an angel guiding two female figures representing the two republics.

The English residents donated a clock tower popularly known as ‘La Torre de los Ingleses’ (Englishmen’s Tower) in a square in the middle of Retiro, where the railways converge (all built by the British to transport grain and meat from the countryside to the harbour).

The monument the Italian collectivity contributed to the centenary celebrations deserves some special attention. It is a 25 m tall Carrara Marble statue of Christophoro Colombo. Its central position, between the presidential palace and the harbour, was a source of pride for the collectivity. I say was, because the urban landscape has continued to be written and re-written along with shifts in the political pendulum. Since the fall of the dictatorship in the 1980s, but most pronounced during the Governments of the Kirchners in the 2000s, certain forms of previously unacceptable difference are resurging, questioning the myth of the ‘White Argentina’ (Gordillo Citation2016, Citation2020). A series of policies and measures have been implemented in towards shifting the exclusionary boundary: indigeneity and afro-descendance have been incorporated as categories in the official statistical apparatus, multilingual education and communication in indigenous languages, official recognition of traditional medical practices, and the removal of a scene commemorating the Conquest of the Desert from the 100 pesos bill to name a few. Meanwhile, anthropologists are pointing to new forms of indigeneization and ethnogenesis (Briones and Delrio Citation2007; Delrio et al. Citation2018; Escolar Citation2007; Gordillo Citation2016, Citation2020; Gordillo and Hirsch Citation2003). In 2015, after a long public debate the Columbus monument was replaced by one to Juana Azurduy, a creole female independence war military leader courtesy of the President of Bolivia, Evo Morales. The monument to Columbus was moved to the coast, next to the airport, facing towards the Europe he left behind, and with his back to the city.

Throughout this section I have shown how a Euro-oriented imagination of Argentina and its exclusionary cosmopolitanism are expressed in a fragment of the urban landscape of its capital. The monuments built by the collectivities, the product of their networking abilities and a measure of their social mobility and presence celebrate both, their promoters as well as their host; in contrast with the scarcity of those of indigenous peoples. Meanwhile, the replacement of the monument to Columbus by the one to Juana Azurduy hopefully might reflect the beginning of a shift in the limits of Buenos Aires’ exclusionary cosmopolitanism, towards more openness and recognition to indigeneity and afro-descendents who so far have been largely invisibilized.

Conclusions

This article has taken the lead from Pnina Werbner, in concretely exploring the ‘anti-cosmopolitan’ dynamics. Instead of taking the ‘happy face’ expressions of vernacular cosmopolitanism in Buenos Aires at face value, I have focused on shedding light on the usually obscured social foundations that enable them. The exploration of different manifestations of the vernacular cosmopolitanism in a variety of registers has evidenced its simultaneously celebratory and exclusionary character. In this way showing that anti-cosmopolitan dynamics are part and parcel of vernacular cosmopolitanisms, and not external to them. The term exclusionary cosmopolitanism was put forward to capture this dynamic.

I have also shown how this exclusionary cosmopolitanism has structural and genealogical affinities with settler colonialism. The particular classificatory configuration that orients openness and closure, which emerges from the Argentine nation-making processes, inspired by Eurocentric civilizational models, establishes the limits of cosmopolitanism on the boundary between immigration and indigeneity.

This limit is reflected in the divergent attitudes taken by the government towards the networking capacities of different collectives. Whereas the networks of those to be celebrated were recognised and empowered (although at the price of subsumption), the others were denied actualising their networking potential. These limits, moreover, are not carved in stone. The recent shift of monuments as the visible tip of other policies of recognition might indicate the beginning of a process of change towards an expansion of the cosmopolitan attitude towards indigeneity.

The limits of exclusionary cosmopolitanism, separating immigration and indigeneity are also replicated in the anthropology of settler societies: immigration and indigeneity are rarely considered together in the anthropology of Argentina (cf Hage Citation1998, 24 for a similar diagnosis in Australia). On the one hand, this may be a consequence of methodological ethnicism, with anthropologists usually specialising in individual groups as well as the high level of investment required to learn new field languages as well as differing conditions. On the other, an inter-disciplinary division of academic labour that has meant that, at least in the foundation and establishment of sociology and anthropology in Argentina, the former focused on issues of modernisation and nation building, while the latter focused on those left outside those processes: indigenous peoples (Guber and Visacovsky Citation2000). There is therefore an alignment between how the settler state defines and relates to these two classes of others, and that of the division of academic labour (this is not unique to Argentina, see Wolfe, Citation1999). Recognising, acknowledging, and subjecting to critique the exclusion inherited in the definition of our objects of study are necessary steps towards a cosmopolitan anthropology. In an era characterised by the weakening of vernacular Euro-North American cosmopolitanisms (Knight, Citation2023), it becomes all the more urgent to identify the fragile achievements of cosmopolitans (Werbner Citation2015) together with their limits, exclusions, as well as their capacities to change.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks the anonymous reviewers for constructive suggestions.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Literally ‘from the harbour’, emic term used to refer to the inhabitants of Buenos Aires.

2 Another and much smaller invisibilized group consists of the descendants of enslaved Africans brought during colonial times and until the closure of the slave trade in 1813 (Andrews Citation1980; Frigerio Citation2008). The 2010 national census showed that 955.037 self-identified as indigenous nationally and 61.876 in the city of Buenos Aires. Meanwhile Afro-descendants counted for 149.493 nationally and 15.764 in the city of Buenos Aires.

3 There is a parallelism between the nations mentioned in the phrase, and Ribeiro’s typology of the peopling of America after colonization: ‘witness peoples’ descendents of ancient civilizations, ‘new peoples’ from the intermixing, and ‘transplanted peoples’ which is the equivalent of settler colonialism (Ribeiro Citation1975, 167–169).

4 These are Mexico, Paraguay, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Austria, Italy, Croatia, Greece, Poland, Lebanon, Rusia, Spain, and Syria.

5 This subsumption cannot be assumed to be accepted unproblematically. The tension between being a collectivity in Argentina or a global diaspora connected to the motherland is an issue observed firsthand in relationship to the Lebanese during own fieldwork as well as in the case of the Basques in Argentina observed by Julieta Gastañaga, personal communication (see also Gastañaga Citation2016).

References

- Alberdi, Juan Bautista. 1853. Bases y puntos de partida para la organización política de la República Argentina: Derivados de la ley que preside el desarrollo de la civilización en la America del Sud, y del Tratado Litoral de 4 de Enero de 1851. Buenos Aires: Imprenta Argentina.

- Alsina, Juan A. 1900. La Inmigración Europea en la República Argentina. Buenos Aires: Imprenta, México.

- Alsina, Juan A. 1910. La inmigracion en el primer siglo de la independencia. Buenos Aires: Alsina.

- Anderson, Benedict. 1990. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London: Verso.

- Andrews, George Reid. 1980. The Afro-Argentines of Buenos Aires, 1800–1900. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Billig, Michael. 1995. Banal Nationalism. London: Sage.

- Briones, Claudia, and Walter Delrio. 2007. “La “Conquista del Desierto” desde perspectivas hegemónicas y subalternas.” Runa. Archivo para las Ciencias del Hombre XXVII: 23–48.

- Brudney, Edward. 2019. “Manifest Destiny, the Frontier, and “El Indio” in Argentina's Conquista del Desierto.” Journal of Global South Studies 36 (1): 116–144. https://doi.org/10.1353/gss.2019.0006.

- Calhoun, Craig. 2008. “Cosmopolitanism and Nationalism.” Nations and Nationalism 14 (3): 427–448. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-8129.2008.00359.x.

- Cañás Bottos, Lorenzo, and Tanja Plasil. 2017. “Den arabiske maten til levantiske innvandrere til Argentina: Autentisitet og standardisering av folk og mat.” In Trangen til å telle: Objektivering, måling og standardisering som samfunnspraksis, edited by Tord Larsen and Emil Røyrvik, 215–236. Oslo: Scandinavian Academic Press.

- Cañás Bottos, Lorenzo, and Tanja Plasil. 2021. “From Grandmother’s Kitchen to Festivals and Professional Chef: The Standardization and Ritualization of Arab Food in Argentina.” In Objectification and Standardization on the Limits and Effects of Ritually Fixing and Measuring Life, edited by Tord Larsen, Michael Blim, Theodore M. Porter, Kalpana Ram, and Nigel Rapport, 151–172. Durham: Carolina University Press.

- Cañás Bottos, Lorenzo, and Tanja Plasil. 2022. “De “turcos” a Argentinos, y de Argentinos a Libaneses. Ciudadanía Extraterritorial de la Diáspora Libanesa en Argentina.” Antropología y Derecho (10): 47–69.

- Cañás Bottos, Lorenzo, and Tanja Plasil. 2023. “When Heritage Becomes Horizon: The Acquisition of Extra-Territorial Citizenship among Lebanese in Argentina.” Revue Européenne des Migrations Internationales 39 (2-3): 43–63. https://doi.org/10.4000/remi.22910.

- Cañás Bottos, Lorenzo, Jan Ketil Simonsen, and Shuhua Chen. 2024. “Cosmopolitan Networks – Networking Cosmopolitans: Between Anyone, the Other and the Making of Sociality.” Anthropological Forum, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2024.2304750.

- Delrio, Walter, Diego Escolar, Diana Lenton, and Marisa Malvestitti. 2018. En el país de nomeacuerdo Archivos y memorias del genocidio del Estado argentino sobre los pueblos originarios, 1870–1950. Viedma: Editorial UNRN

- Delrio, Walter, Diana Lenton, Marcelo Musante, and Marino Nagy. 2010. “Discussing Indigenous Genocide in Argentina: Past, Present, and Consequences of Argentinean State Policies toward Native Peoples.” Genocide Studies and Prevention. An International Journal 5 (2). https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/gsp/vol5/iss2/3.

- Escolar, Diego. 2007. Los dones étnicos de la Nación: Identidades huarpe y modos de producción de soberanía en Argentina. Buenos Aires: Prometeo.

- Frigerio, Alejandro. 2008. “De la “desaparición” de los negros a la “reaparición” de los afrodescendientes: comprendiendo la política de las identidades negras, las clasificaciones raciales y de su estudio en la Argentina.” In Los estudios afroamericanos y africanos en América Latina: herencia, presencia y visiones del otro, edited by Gladis Lechini, 117–144. Cordoba: Ferreira Editor / CLACSO.

- Gastañaga, Julieta. 2016. “El derecho a decidir del pueblo vasco: iniciativas locales, acciones globales.” In Un siglo de migraciones en la Argentina contemporánea: 1914–2014, edited by Nadia De Cristóforis and Susana Novick, 69–88. Buenos Aires: Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Universidad de Buenos Aires.

- Gordillo, Gastón. 2016. “The Savage Outside of White Argentina.” In Rethinking Race in Modern Argentina, edited by Eduardo Elena and Paulina Alberto, 241–267. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gordillo, Gastón. 2020. “Se viene el malón. Las geografías afectivas del racismo argentino.” Cuadernos de Antropología Social (52):7–35. https://doi.org/10.34096/cas.i52.8899.

- Gordillo, Gastón, and Silvia M. Hirsch. 2003. “Indigenous Struggles and Contested Identities in Argentina Histories of Invisibilization and Reemergence.” Journal of Latin American Anthropology 8 (3): 4–30. https://doi.org/10.1525/jlca.2003.8.3.4.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1973. “The Strength of Weak Ties.” American Journal of Sociology 78 (6): 1360–1380. https://doi.org/10.1086/225469.

- Guber, Rosana, and Sergio Visacovsky. 2000. “La Antropologia Social en la Argentina de los ‘60 y ‘70. Nacion, Marginalidad Critica y el “Otro” Interno.” Desarrollo Económico. Revista de Ciencias Sociales 40 (158): 289–316.

- Hage, Ghassan. 1998. White Nation: Fantasies of White Supremacy in a Multicultural Society. Annandale: Pluto Press Australia.

- Halperín Donghi, Tulio. 1982. Una nación para el desierto argentino. Buenos Aires: Centro Editor de América Latina.

- Hannerz, Ulf. 2006. Two Faces of Cosmopolitanism: Culture and Politics, Dinámicas Interculturales. Barcelona: CIDOB edicions.

- Hannerz, Ulf. 2010. Anthropology's World: Life in a Twenty-First-Century Discipline. London: Pluto.

- Huyssen, Andreas. 2003. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Knight, Daniel M. 2023. “The Death of Vernacular Cosmopolitanism.” Anthropological Forum, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00664677.2023.2218583.

- Quijada, Mónica. 2003. “¿"Hijos de los barcos” o diversidad invisibilizada? La articulación de la población indígena en la construcción nacional argentina (siglo XIX).” Historia Mexicana 53 (2): 469–510.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2012. Anyone: The Cosmopolitan Subject of Anthropology. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2015. “Anthropology through Levinas.” Current Anthropology 56 (2): 256–276. https://doi.org/10.1086/680433.

- Rapport, Nigel. 2019. “Anthropology through Levinas (Further Reflections): On Humanity, Being, Culture, Violation, Sociality, and Morality.” Current Anthropology 60 (1): 70–90. https://doi.org/10.1086/701595.

- República Argentina Congreso Nacional. 1876. Ley de Inmigración y Colonización. Buenos Aires: República Argentina Congreso Nacional.

- Ribeiro, Darcy. 1975. O Processo Civilizatório. 3rd ed. Rio de Janeiro: Civilização Brasileira.

- Sarmiento, Domingo Faustino. [1845] 1998. Facundo: Or, Civilization and Barbarism. Translated by Mary Mann. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Shumway, Nicolas. 1991. The Invention of Argentina. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Terán, Oscar. 2015. Historia de las ideas en la Argentina. Diez lecciones iniciales, 1810–1910. Buenos Aires: Siglo veintiuno editores.

- Veracini, Lorenzom. 2011a. “Introducing.” Settler Colonial Studies 1 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/2201473X.2011.10648799.

- Veracini, Lorenzo. 2011b. “On Settlerness.” Borderlands 10 (1): 1–17.

- Werbner, Pnina. 2006. “Vernacular Cosmopolitanism.” Theory, Culture & Society 23 (2-3): 496–499.

- Werbner, Pnina. 2015. “The Dialectics of Urban Cosmopolitanism: Between Tolerance and Intolerance in Cities of Strangers.” Identities 22 (5): 569–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/1070289X.2014.975712.

- Wolfe, Patrick. 1999. “Settler Colonialism and the Transformation of Anthropology: The Politics and Poetics of an Ethnographic Event.” In Writing Past Colonialism, edited by Phillip Darby, Margaret Thornton, and Patrick Wolfe. London: Cassell.

- Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. “Settler Colonialism and the Elimination of the Native.” Journal of Genocide Research 8 (4): 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/14623520601056240.