ABSTRACT

This paper seeks to challenge the notion of the invisible slave in the archaeological record and investigates the way in which material culture may reflect the movements and practices of enslaved labourers on the East African Swahili coast. Archaeological approaches to enslavement have revealed the nuanced and complex experiences of a group of people often under-represented or absent in historical records, while also grappling with the challenges presented by the ambiguity of the material evidence. This paper presents a case study from the fifteenth-century Swahili site of Songo Mnara in Tanzania, an architecturally and materially wealthy stone town in the Kilwa archipelago. It focuses on the context, use, and spread of beads across the site, and considers the possibility of interpreting some classes — such as locally made terracotta beads — as proxies for the underclass and enslaved in an otherwise wealthy settlement. It presents a key study towards the aim of building a highly necessary methodology for the archaeology of slavery in East Africa and beyond, and suggests that certain types of material culture might be used to explore the activities of enslaved and/or underclass individuals.

RÉSUMÉ

Cet article vise à remettre en question la notion de l'esclave invisible dans les données archéologiques, examinant la façon dont la culture matérielle peut refléter les mouvements et les pratiques des travailleurs asservis sur la côte swahilie d’Afrique de l'Est. Les recherches archéologiques sur le thème de l'asservissement ont révélé les expériences nuancées et complexes d'un groupe de personnes souvent sous-représenté ou absent dans les archives historiques. Ces recherches ont également dû faire face aux défis qui se posent dû à l'ambiguïté des preuves matérielles. Cet article présente une étude de cas, constituée par le site swahili de Songo Mnara, située dans l'archipel de Kilwa (Tanzanie). Songo Mnara est une ville de pierre datant du quinzième siècle qui fut riche architecturalement et matériellement parlant. La présente étude se concentre sur le contexte, l'utilisation et la propagation des perles à travers le site, et considère la possibilité que certains types — par exemple les perles en terre cuite fabriquées localement — pourraient être interprétés comme un identifiant de membres asservis, ou faisant partie d’une sous-classe, au sein d’une communauté autrement affluente. Cet article présente une étude clé dans le but d’élaborer une méthodologie, très nécessaire, pour l'archéologie de l'esclavage en Afrique de l'Est et au-delà. Il est proposé que certains types de culture matérielle pourraient être employés pour explorer les activités des personnes réduites en esclavage et/ou appartenant à une sous-classe.

KEYWORDS:

Introduction

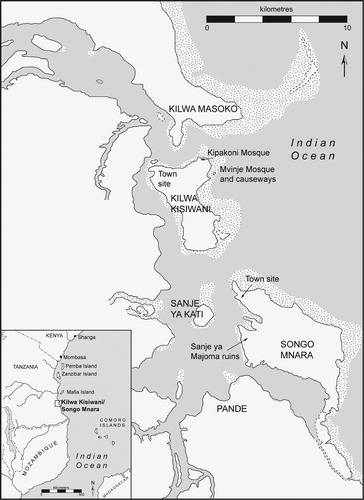

One of the great challenges of an archaeology of slavery is to identify the material signature of the activities of enslaved people, especially where they were living in and among the population that enslaved them. This paper offers an approach to such investigations by acknowledging the likely presence of enslaved people at the fifteenth-century Swahili site of Songo Mnara () and investigating the distribution of beads there as a possible indicator of their activities and movement across an urban setting. This approach offers a way of beginning to investigate the role of enslaved people at pre-colonial Swahili sites in the absence of written records. A lack of written records has often been cited as the main obstacle to recognising slavery in pre-colonial Africa, with material evidence deemed too ambiguous without the support of written sources. Nonetheless, we believe that the ubiquity of slavery and enslaved persons was intimately bound up into all social practices, enabling forms of wealth and power as well as structuring the most humble social interactions (cf. Almeida Citation2020). Thus, slavery ‘can be considered a “total social fact”, part and parcel of the social, political and economic landscapes that produced the material traces we recover from archaeological sites’ (Stahl Citation2008: 38). In societies known to have practised slavery, we should see all evidence as potential for slavery studies, rather than dismissing it as an avenue of archaeological study due to a presumed lack of evidence.

Songo Mnara was a small town on an island off the coast of southern Tanzania, just south of the historically better-known city of Kilwa Kisiwani. The site has been extensively excavated over four field seasons (2009–2016) by the Songo Mnara Urban Landscape Project, revealing a rich material record associated with extensive stone and earthen architecture. In recent centuries, urban populations on the Swahili coast were actively involved in the Indian Ocean slave trade and also kept enslaved domestic workers themselves. Documents indicate a long history of slaving, extending back to the first millennium AD (Vernet Citation2009: 39). Yet neither the slave trade nor the keeping of enslaved people locally before the nineteenth century have been well explored archaeologically. Archaeology holds great potential for investigating different labour roles and the display of wealth within Swahili society, allowing us to move beyond binary notions of élites and non-élites and to question socio-economic identities in the past (Pawlowicz Citation2019), as well as to explore the social, cultural and economic rôles of enslaved individuals.

Archaeological approaches to enslavement

The urban character of Songo Mnara shapes our approach towards the study of its enslaved and underclass population. It permits a focus on more intimate forms of slavery, such as domestic slavery, within an urban setting rather than as part of a plantation economy. This resonates with Ellis and Ginsburg’s (Citation2017) volume tackling urban slavery in antebellum North America, which highlights the role of the material and built world in shaping the experiences and opportunities of the enslaved. Particularly instructive is Ellis’ (Citation2017) assessment of the populations of Annapolis, an urban settlement in Maryland, in which the architectural features of the town are used to assess the daily freedom of movement and access to spaces afforded to enslaved inhabitants. The urban environment provided a different kind of life and freedom of movement for the enslaved compared to rural plantation sites. This study is assessed along with the material culture recovered through archaeological excavations by Yentsch (Citation1994a), which called attention to an artefact assemblage with African-American associations. Beads in particular were highlighted as reflecting the African roots of the enslaved, as well as their successful attempt to maintain a separate identity (Ellis Citation2017). The importance of beads has long been recognised in North American archaeology for creating and maintaining African-American identities (Stine et al. Citation1996), highlighting the role of enslaved women (Yentsch Citation1994b) and understanding access and production among the enslaved (Orser Citation1990; Samford Citation1996).

Such studies from the colonial Atlantic world have to some degree inspired research in East Africa. Through Croucher’s (Citation2015) work on Zanzibar and studies by Seetah (Citation2015) and Haines (Citation2018, Citation2020) on Mauritius, the plantation systems of East Africa are becoming integrated into the archaeology of colonial-era slavery, adding important new insights to this understudied region. In addition, Kusimba (Citation2004) has taken a landscape approach to exploring the responses of inland communities in Tsavo Hills, Kenya, to increased slave raids associated with the growing demand in the Indian and Atlantic Ocean worlds, an approach also successfully used by scholars working in West Africa (MacEachern Citation1993; Soumonni Citation2003; Kankpeyeng Citation2009).

Common to all these studies is the availability of textual sources, which help archaeologists situate their work in time and space. Such textual data are not available for the East African coast before the sixteenth century and archaeological studies of slavery in text-less societies offer unique challenges and are necessarily speculative (see, for example, Ames Citation2001 and Raffield Citation2019). Additional challenges are offered by the unique cultural contexts in which slavery existed in East Africa: slavery within African contexts has often been between populations that share ethnic and/or social ties and obligations or that are geographically proximate (Hartwig Citation1977; Perbi Citation2004). Forms of enslavement and dependency were also more diverse. Nevertheless, comparative case studies such as those mentioned above offer crucial insights into the archaeologies of the enslaved and into how material culture has been created and used by enslaved people in their negotiation of everyday life and forced displacement. For the purpose of this study, they help underline the importance of things where texts are inadequate.

Slavery on the East African coast

Discussions of slavery on the East African coast have often dwelt on the trade in enslaved people that passed through coastal towns on their route into the western Indian Ocean. Sparse documentary references () testify to this trade from at least the ninth century, when the ‘Zanj revolt’ in present-day Iraq brought into focus the presence of a population of East African slaves in the region (Popović Citation1999; cf. Talhami Citation1977; Vernet Citation2009). Yet despite this early and probably prolonged commerce in enslaved Africans, there is almost no archaeological trace of it through East African ports that were probably also the settings for forms of domestic slavery. Both would have fallen within the world of Islamic slavery, which has a different character to the chattel slavery of the Atlantic trade. Here, we discuss the evidence for them before focusing on enslaved populations within Swahili towns, of whom almost nothing is known.

Table 1. Textual references to slavery in East Africa.

The Islamic trade in enslaved people

Although independent of the Islamic caliphates of the Middle East and North Africa, the settlements and towns of East Africa were part of the larger Islamic and Indian Ocean worlds (as well as of wider eastern and southern African social and economic landscapes) that increasingly also included trade in enslaved people (Fisher and Fisher Citation1970; Abir Citation1985; Campbell Citation2003). The demand for enslaved people was particularly high in the second millennium AD, peaking in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, a demand increasingly filled by people from Sub-Saharan Africa as other supplies diminished. Although much scholarly focus has been given to the trans-Saharan trade with influential West African and central Sudanic states (Haour Citation2011), a number of enslaved people would have originated in the East African interior and been traded through Swahili towns.

Very little is known about the extent of this trade and its impact on East African communities, both in the interior and on the coast, before the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, when historical texts became more abundant and foreign powers in Europe and Oman controlled parts of the coast (Vernet Citation2009: 39–41). There can be little doubt that enslaved people were traded out of East Africa from as early as the ninth century AD. However, no archaeological trace of this trade has yet been found at late first millennium or early second millennium Swahili sites. In fact, little is known about Swahili market places in general. The only exception may be two building complexes at Kilwa Kisiwani known as Husuni Kubwa and Husuni Ndogo that are proposed to have been built as both marketplaces and storage facilities, with the latter also suggested to have been a possible holding area for enslaved individuals (Shepherd Citation1982), probably due to its unusual architecture and high walls and to comparisons with caravanserais/khans elsewhere in the Islamic world.

Internal slavery in East Africa

It is likely that the first Muslim merchants arriving in East Africa witnessed societies in which slave trading and enslaved individuals were already present. Various forms and levels of servitude were common aspects of society in many areas of Africa (Kopytoff and Miers Citation1977; Robertshaw and Duncan Citation2008), just as they were in the rest of the world. To what extent this constituted what we now call slavery has been widely debated, due to difficulties with definitions, local understandings of kinship, servitude, and enslavement, historical and linguistic processes and colonial encounters (Miers Citation2003). After conversion to Islam in coastal East Africa, slavery was probably practised in a way that mixed local and Islamic customs. Enslaved people may have been signifiers of wealth and status, allowing their enslavers to live a certain lifestyle associated with élite consumption and behaviour, such as enabling a greater degree of female seclusion in some households. Enslaved domestic workers may have been common in East Africa as they were in other areas of the Muslim world (Hunwick Citation1992: 14–15; Campbell Citation2003: xx), at least for the wealthier inhabitants of towns and villages. Here, they would have carried out every-day tasks such as cooking, cleaning and child-minding, as well as labours including spinning and weaving. Due to the association of Muslim households with women, we might assume that most such domestic workers were also women. Enslaved women would have been able to move around the house more freely than a man, accessing the more private and secluded spaces intended for family and female life. This is a situation described for nineteenth-century Lamu, with enslaved female domestic workers in Swahili households and male field workers on mainland plantations (Ylvisaker Citation1979: 11; Vernet Citation2005). This is a cautious proposition, however, as we do not wish to impose recent customs onto the Swahili household or to extrapolate backwards from the very different Omani-dominated society of the nineteenth century. We do not therefore propose that enslaved domestic workers could not have been male, although the nature of the work in which enslaved people engaged implies that female workers are more likely. Some may also have become concubines to the head of the household, a practice common throughout the Islamic world. The use of enslaved domestic workers in urban Islamic communities is well-known through historical accounts (Campbell Citation2003; Miller Citation2008) and, although we know less about the role of enslaved people in rural areas, we might suppose that enslaved agricultural workers were also present. Ibn Battuta (Freeman-Grenville Citation1975: 32) writes of enslaved people working in Kilwa during his visit there in 1331, but does not mention what their various labour roles may have included. As this example shows, textual evidence is elusive on the topic of internal slavery on the Swahili coast. There is thus a crucial role for archaeology in exploring slavery in pre-sixteenth-century Swahili societies.

Songo Mnara: a fifteenth-century Swahili stone town

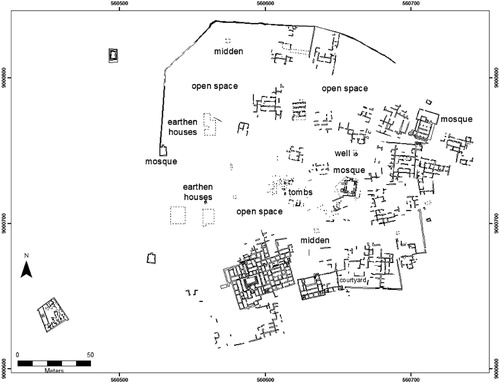

Songo Mnara is a small coral island belonging to the Kilwa archipelago off the coast of Tanzania, the latter being home to several Swahili sites dating from the ninth century AD, of which Kilwa Kisiwani is the most widely recognised and longstanding. The site of Songo Mnara comprises a remarkably well-preserved stone town with dozens of extant houses built from coral rag and lime mortar (). It was recorded and preliminarily studied by Dorman (Citation1938), Mathew (Citation1959), Chittick (Citation1961), Garlake (Citation1966), Pradines and Blanchard (Citation2005) and Rüther et al. (Citation2012), but has only received significant archaeological attention through the Songo Mnara Urban Landscape Project, directed by Wynne-Jones and Fleisher between 2009 and 2016. Songo Mnara was occupied for a short time between the late fourteenth and early sixteenth centuries AD. Extensive surveys and excavations have revealed complex urban and rural landscapes across the island with a presumably large and affluent élite presence and connections to Indian Ocean trade networks.

The Songo Mnara Urban Landscape Project has conducted archaeological investigations of many kinds across the buildings and spaces of the site. Several of the site’s stone houses have been excavated either completely or in part as a way of understanding how domestic space was structured (Wynne-Jones Citation2013). In addition, survey, systematic shovel testing and excavations have explored the public spaces of the site (Fleisher Citation2014). In the process, a series of wattle and daub houses recovered in the western open area of Songo Mnara have likewise been excavated and sampled. This means that data are available from both stone and earthen forms of housing across the site, as well as from outdoor spaces and activity areas such as the wells and tombs around which people would have moved in their daily journeys. It is not the case, however, that the wattle and daub houses can be regarded as simple non-élite residences since they contained comparable quantities of imported goods, coins and general material wealth to the stone houses. They seem instead to have been spaces with particular functions, apparently related to craft-working or domestic activities for the stone house populations. Here, then, we do not discuss wattle and daub houses as a different population, but instead as part of an overall townscape, through which both élite and lower-status groups would have moved.

Various productive activities took place within the houses and open spaces of the town and in its hinterland, including spinning, metal production, fishing and agriculture (Wynne-Jones Citation2013; Fleisher Citation2014; Fleisher and Sulas Citation2015; Pawlowicz Citationn.d.). The type and level of research carried out at Songo Mnara makes it an excellent site for studying domestic slavery, as it allows new perspectives and methods to be utilised with existing data. It is also a settlement in which enslaved people are likely to have lived, as it housed a substantial élite population as evidenced by the large number of stone houses at the site. Its proximity to the larger prominent town Kilwa Kisiwani is also significant since, as noted above, this is one of the few places for which we have written historical evidence of enslaved people as a result of Ibn Battuta’s fourteenth-century account of his travels through East Africa (Freeman-Grenville Citation1975: 27–32).

Aim of research

The aim of the research detailed below is to identify activities pursued by different parts of Songo Mnara’s population, on the assumption that this will have included enslaved and servile groups. This is a first step towards developing a methodology for investigating urban domestic slavery through archaeology. This study looks specifically at beads as objects of personal adornment worn (and lost) predominantly by women. In particular, we explore the spatial distribution of terracotta and shell beads, which are artefacts that have not received much attention compared to imported glass beads. Differences in distribution between terracotta, shell and glass beads may be informative with respect to different women’s access to material goods and movement around the town.

There are strong precedents for linking glass beads to élite women. Archaeologies and ethnographies of recent centuries have both made this link explicit (Donley-Reid Citation1990; although see Marshall Citation2018 for further discussion). Men use only prayer beads, which are generally larger than most of the glass beads found at Songo Mnara (Wood Citation2009: 221). Glass beads were important in cargoes of imported goods from the seventh century onwards and at Kilwa became common from the eleventh century and were worn on a large scale within the town, as well as being traded inland. The owners and wearers of glass beads might thus be conflated with an élite, whose presence is indicated by the grand stone houses at the site. Traditionally, earthen houses have been seen as belonging to non-élite households (Allen Citation1993; Fleisher and LaViolette Citation1999). At Songo Mnara, however, this may not be the case as the entire settlement seems to have had similar access to material wealth. Yet, the presence of grand houses, rich material culture and craft production indicates the presence of a diverse population, which must have included labourers, builders and artisans, as well as enslaved domestic workers. Despite a number of efforts to broaden the scope of research to emphasise the more socio-economically complex populations of pre-colonial Swahili towns and villages (Pawlowicz Citation2012, Citation2019; LaViolette and Fleisher Citation2018; Wynne-Jones Citation2018), these populations remain difficult to identify in the archaeological record in the absence of distinct houses and settlements. Here, we explore the distribution of non-glass beads alongside the glass ones, including those made of shell (cone shells ground into discs) and terracotta, on the assumption that these were more likely to have been worn by those non-élite members of society. Beads are employed as a proxy for differential access to wealth to trace the movements of different groups that we assume would have included domestic labourers.

Methods

The underlying theory driving this research is the supposition that enslaved people in Swahili urban settlements would have been culturally, religiously and economically different from the main population. The lower socio-economic status of enslaved people would have kept them from accessing certain kinds of goods and spaces, while their cultural and religious background might have been retained to some degree through specific rituals, practices and activities, although various degrees of assimilation into the dominant society are to be expected. These differences may present themselves in a variety of tangible and intangible ways, including songs, dances and music, as well as clothes and personal adornment, production methods and burial customs.

Terracotta beads () were chosen as a small but promising dataset to ascertain the plausibility of this hypothesis. Despite occurring at other sites along the Swahili coast from the eleventh century onwards, including Kilwa (Chittick Citation1974: 478), Sudi Bay (Pollard and Ichumbaki Citation2017: 480), Shanga (Horton Citation1996: 333), Mahilaka (Radimilahy Citation1998: 183), Manda (Chittick Citation1984: 184) and Kilepwa (Kirkman Citation1952: 180), they rarely receive much attention. Fleisher (Citation2003: 326–237) has argued that some of these beads may, in fact, be spindle whorls, although few attempts have been made to distinguish formally between the two and separation is usually made on the basis of size, symmetry and weight (DeVos Citationn.d.). Linda Donley-Reid (Citation1990: 51) also refers to ‘orange beads made of clay’ in her ethnographic work on the Kenya coast, indicating that these were made locally by poor people unable to afford imported coral beads, while Wood (Citation2011: 3) concurs that terracotta beads were made locally. Shell beads have received more attention, particularly for earlier periods when they outnumber those made from glass, yet have normally been described as goods for export to inland African markets.

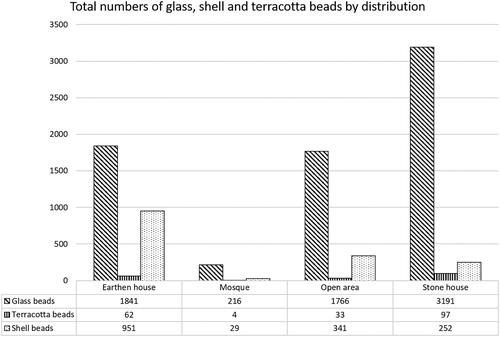

The bead assemblage from Songo Mnara includes a total of 8783 beads found through excavation and sieving of excavated deposits. The recovery of artefacts through excavation cannot be entirely comprehensive, but every care was taken to recover as many small artefacts as possible. All deposits were sieved through a 2-mm-mesh and samples were wet-sieved as part of the recovery of botanical data. The assemblage can therefore be seen as representative of the beads lost during the occupation of Songo Mnara. If there is a bias, then terracotta beads would be more likely to be over-represented compared to the much smaller glass and shell types.

Results

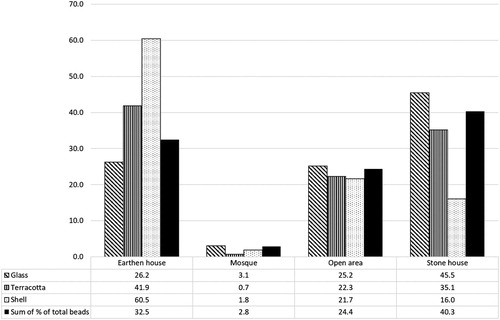

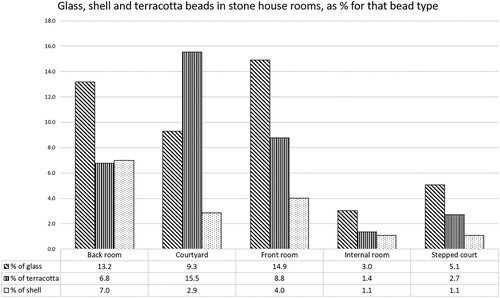

At Songo Mnara, imported beads are by far more common than locally made ones in the archaeological record, with glass beads representing almost 80% of the beads located. In contrast, shell beads comprise 18% of the total assemblage and terracotta beads 2%, totalling just 196 from all excavated trenches. The bead types are distributed across all types of space, although all bead types are most numerous in domestic contexts, both stone and earthen houses (). One way to account for the different overall quantities is by analysing the percentage of each bead type by location (). Domestic settings (both stone and earthen houses) contained large numbers of each type and were the richest category of location. In general, the proportions of bead types in these settings were comparable: 71% of the glass beads, 76% of the shell beads and 77% of the terracotta beads were found in domestic spaces. Beyond this basic similarity, however, it is notable that (as a percentage of the total found) terracotta and shell beads are more prevalent in the earthen houses, while glass beads are more prevalent in those built of stone. The prevalence of shell beads in the earthen house contexts corresponds with evidence for shell-bead manufacture in them and with the proposition that they were locations for craft production rather than simple houses. In the open areas of the site, the percentages of all three bead types are similar, with glass beads slightly more common in open spaces and mosque contexts. The unevenness of the distribution of the bead types between types of houses and spaces may point to patterns of movement and activity between differing groups of people as indicated by particular bead types. It also begins to suggest particular patterns that can be explored further.

Correlations with types of space

Interior and domestic spaces

Among the Songo Mnara data, the rooms of stone houses can be distinguished, although the earthen houses still appear as a single dataset since their room layout could not be reconstructed through excavation. The first caveat in exploring these data is that beads (and all artefacts) were found in much greater abundance in earthen floors than atop plaster floors; this presumably reflects the fact that they were more easily lost and less easily cleaned away on earthen floors. The types of space that appear to be richest in artefacts across datasets are those with earth floors — the earthen houses were particularly rich, as were courtyards (outdoor work spaces) and the back rooms of stone houses, which normally had earthen floors. In the context of Songo Mnara, the earthen houses were not impoverished in overall material goods compared to their stone-dwelling neighbours, unlike other studies that have compared urban and rural houses on the Swahili Coast (LaViolette and Fleisher Citation2018). The abundance of beads from these contexts echoes the data from imported ceramics, coins and other markers of wealth, all of which were found spread across the site. These should not therefore be seen as poor households, but might instead be different types of space associated with types of activity.

Here we explore the data from interior and domestic spaces according to a number of archaeologically defined categories:

Earthen houses, without visible interior subdivisions;

Entrance rooms of stone houses;

Stepped courts inside stone houses;

Other interior spaces in stone houses;

External courtyards and workspaces.

In the stone houses, it is possible to break the space down into clearer subdivisions. Here we discuss some of them in aggregate, following the patterning that can be seen in the bead data (). The largest percentage of terracotta beads is in the courtyard spaces. These are external, walled areas that are entered from the rear of the stone houses. The archaeology of these areas suggests that they were places for the preparation and storage of food. In some cases, they also had entrances from more than one house, suggesting that they were spaces for socialising between residents from different houses. As workspaces, it is notable that they are also the settings for some of the larger quantities of terracotta beads on the site. As a percentage of the total, shell beads were the least common of all bead types in stone house rooms, with the greatest percentages found in front and back interior rooms. Neither shell nor terracotta were common in the stepped courts, in contrast to the courtyards. Stepped courts were prominent unroofed internal spaces that had packed earth floors. They seem to have been kept quite clean overall and numbers of all artefacts are notably low. Only five terracotta beads were found in these areas, compared with 355 glass beads and 17 shell beads. This is a ratio of 1:71 terracotta to glass, compared to an overall site ratio of 1:35. They also seem to have been spaces for particular types of élite consumption, although not food preparation (Wynne-Jones Citation2013), so the lack of terracotta beads in these spaces has implications for the involvement of their wearers in those types of activity. Instead, they were more common in the other spaces of the house, where a mixture of domestic labour and habitation may be discerned.

Public and open spaces

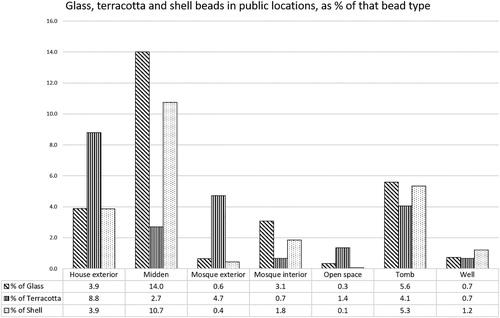

Beads were also common across the public and open spaces of the site. This includes a wide range of types of space. The open spaces were a major focus of investigation for this Songo Mnara project and it has been possible to identify areas associated with different activities (Fleisher Citation2014). Here, we present the bead data in relation to some of the most notable subdivisions (). As a percentage of the total assemblage type, glass and shell beads were most common in the midden deposits. Only four terracotta beads were found in middens, compared to 169 shell beads and 982 glass beads, a ratio of 1:245 which is more startling than their lack inside the stepped courts. This is a more difficult result to interpret, but could indicate that the middens were associated with only certain types of waste, possibly from stone houses, although preliminary studies of ceramics, fauna and botanical waste suggest that they are comparable with the broader settlement. It might also suggest, perhaps counter-intuitively, that the terracotta beads were more carefully curated and were less likely to be disposed of (presumably accidentally) along with household waste.

Figure 7. Songo Mnara: glass, terracotta and shell beads in public locations as a percentage of that bead type.

One notable pattern is the relative prevalence (as a percentage of the total type assemblage) of terracotta beads in particular outside spaces. These include the areas immediately outside houses and mosques, as well as open spaces more generally. The areas excavated outside houses include locations at the base of grand staircases, but also areas where animals may have been stored (Sulas and Madella Citation2012). Spaces exterior to mosques include the immediate area outside doorways and entrances. In spaces associated with burials and tombs, there was a much more even distribution of bead types, with approximately 5% of each type found there.

Discussion

The terracotta and shell beads at Songo Mnara may show the movement of different types of people across the site and within its houses. In every context across the site, glass beads are numerically dominant and it is clear that their wearers were responsible for a greater share of the material assemblage. Beads might be presumed to have been used by women and the terracotta beads are believed to represent a group of people doubly under-represented in the archaeological record: non-élite or servile women. Despite the numerical dominance of glass beads in the earthen houses, the proportions of different types are markedly different than in other settings. The terracotta and shell both have their highest quantities in these structures, suggesting an association between their wearers and the earthen houses. Conversely, the lowest proportions of glass beads are found in these houses.

The presence of terracotta beads within the stone houses is noteworthy, as these houses have been interpreted as spaces used by élite groups, suggesting that the wearers of the terracotta beads may have been (enslaved?) domestic workers. Houses were important arenas for social interaction, ritual performance and household production in Swahili society in the early to mid-second millennium AD (Wynne-Jones Citation2013). As such, these spaces and their material culture are ideal for studying social relationships and status performance on the small scale. The presence of terracotta beads within high activity areas, such as courtyards, suggests that domestic workers were employed in various labours, including preparation and cooking of food, spinning of cotton thread (and perhaps also cloth production) and lime production. Concentrations of these beads just outside stone houses may also point to the way in which domestic workers were associated with such houses, but only in more marginal spaces. The lack of beads in spaces associated with (élite) food consumption, such as the stepped courtyard, suggests that these domestic workers may not have been allowed to (or did not need to) access these specific areas of the house as frequently, areas that may have been generally reserved for the immediate family, guests and private affairs. There seems to be little doubt, however, that these domestic workers were a part of the household, embroiled in the daily lives and activities of the other members.

Terracotta and shell beads recovered from open (public) spaces across the town, suggest a significant degree of freedom of movement for their wearers, which matched that of the élite population. One exception to this is the mosque: although terracotta beads were recovered beneath its floor and outside it, none were found above the floor inside the building. This is not surprising, as enslaved workers are not thought to have been Muslim, or at least not initially. Although we currently have no knowledge of the origins of enslaved workers within Swahili towns, and therefore cannot assume their religious or cultural background, it seems likely that they were considered outsiders in some ways. Even those enslaved persons who converted to Islam, a practice well-known elsewhere in the Islamic world (Salau Citation2009: 95), would probably not have had access to important religious spaces such as mosques. The presence of glass beads inside the mosque is informative as well, as it might suggest that élite women were praying there, contrary to religious practice on the coast from the eighteenth century onward. Ethnographic work from recent centuries highlights mosques as spaces used and frequented by men, while women prayed at home, in keeping with the more limited movement and seclusion of élite women (Donley Citation1987: 186). This practice may have been introduced following Omani expansion and colonisation on the East African coast from the eighteenth century, rather than reflecting earlier Swahili religious practices. The data from Songo Mnara may thus suggest that women, including those presumed to have been domestic labourers, enjoyed more freedom of movement in general and that élite women may also have prayed in the mosques.

A significant aspect of the artefact data from the site is the presence of rich material culture assemblages underneath the floors of several houses. These under-floor fills have not been included in the data presented above. They are only noticeable in those rooms with a plaster floor, but add another layer to our interpretation. The presence of terracotta beads beneath the floors allows us to develop ideas about the role of enslaved labourers outside the domestic sphere. If enslaved workers were a feature of some of the wealthy Swahili towns, we can assume that they were employed in a variety of professions, including building. Construction of stone houses would have required strength, skill and time, with work probably carried out by both men and women, enslaved and free. Using enslaved rather than free labour would have allowed for an extra element of control in the construction of domestic structures, however, and may have been seen as a long-term investment.

Concluding remarks

This study argues that the presence, movement and activities of enslaved people can be understood through certain types of material culture and their distribution. Certain artefacts may stand out in a general assemblage by reason of their aesthetic form, use or distribution. Locally made terracotta and shell beads at the site of Songo Mnara provide an example of such material culture that may serve as a possible proxy for enslaved labourers at this urban site. The location of the beads within production areas of wealthy households strengthens the hypothesis that terracotta beads were made and used by lower-class and enslaved individuals, some of whom seem to have been employed in the service of wealthier inhabitants. Enslaved workers were ubiquitous in many past societies worldwide and central to the development of these societies through their productive labours and cultural and religious influence. Our study has shown the potential that exists for highlighting the role of enslaved workers through archaeology and allows us to build a framework in which to make these previously invisible people visible.

Acknowledgements

The work was conducted in collaboration with the Antiquities Division of the Ministry of Natural Resources and Tourism, Tanzania, under COSTECH permit number 2013-219-NA-2009-46. The authors have followed the terminological guidelines of Foreman Citationet al. in writing this paper. We are grateful to Peter Robertshaw for his comments on the draft of this paper and to two anonymous reviewers for their comments and suggestions.

Notes on contributors

Henriette Rødland is a PhD student in the Department of Archaeology and Ancient History at Uppsala University, Sweden. Her work focuses on material expressions of social inequality, slavery and socio-economic identities in pre-colonial Swahili societies.

Stephanie Wynne-Jones is Senior Lecturer in Archaeology at the University of York, core group member of the DNRF Centre of Excellence for Urban Network Evolutions (Aarhus) and Honorary fellow at the University of South Africa. She works on the historical archaeology of eastern Africa with a particular focus on the Swahili coast. Her work explores themes of urbanism, material culture, value and identity.

Marilee Wood is an independent researcher specialising in the study of glass beads in Africa in the pre-European period. She obtained her MA degree from the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg and her PhD from Uppsala University.

Jeffrey Fleisher is a Professor of Anthropology at Rice University, Houston. His research on the eastern African coast focuses on urban settlement patterns, rural and non-élite residents and the use of open and public space. His current research in south-central Africa focuses on issues of mobility and rootedness.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abir, M. 1985. “The Ethiopian slave trade and its relation to the Islamic world.” In Slaves and Slavery in Muslim Africa: Volume 2 — The Servile Estate, edited by J.R. Willis, 123–136. London: Frank Cass.

- Almeida, M.L. de. 2020. “Slave sacrifices in the Upemba Depression? Reinterpreting Classic Kisalian graves in the light of new linguistic evidence.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 55: 421–438.

- Allen, J. de V. 1993. Swahili Origins: Swahili Culture and the Shungwaya Phenomenon. London: James Currey.

- Ames, K.M. 2001. “Slaves, chiefs and labour on the northern Northwest Coast.” World Archaeology 33: 1–17.

- Campbell, G. 2003. “Introduction: slavery and other forms of unfree labour in the Indian Ocean World.” Slavery & Abolition 24(2): ix–xxxii.

- Chittick, H.N. 1961. “Excavations at Songo Mnara: annual report of the Department of Antiquities.” Dar es Salaam: Tanganyika Department of Antiquities.

- Chittick, H.N. 1974. Kilwa: An Islamic Trading City on the East African Coast. Nairobi: British Institute in Eastern Africa.

- Chittick, H.N. 1984. Manda: Excavations at an Island Port on the Kenya Coast. Nairobi: British Institute in Eastern Africa.

- Croucher, S.K. 2015. Capitalism and Cloves: An Archaeology of Plantation Life on Nineteenth-Century Zanzibar. New York: Springer.

- DeVos, P. n.d. “Spindle whorls at Songo Mnara.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Donley, L.W. 1987. “Life in the Swahili town house reveals the symbolic meaning of spaces and artefact assemblages.” African Archaeological Review 5: 181–192.

- Donley-Reid, L.W. 1990. “Power of Swahili porcelain, beads and pottery.” Archaeological Papers of the American Anthropological Association 2: 47–59.

- Dorman, M.H. 1938. “The Kilwa civilization and the Kilwa Ruins.” Tanganyika Notes and Records 6: 61–71.

- Ellis, C. 2017. “Close quarters: master and slave space in eighteenth-century Annapolis.” In Slavery in the City: Architecture and Landscapes of Urban Slavery in North America, edited by C. Ellis and R. Ginsburg, 69–86. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Ellis, C. and Ginsburg, R. (eds). 2017. Slavery in the City: Architecture and Landscapes of Urban Slavery in North America. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press.

- Fisher, A.G.B. and Fisher, H.J. 1970. Slavery and Muslim Society in Africa: The Institution in Saharan and Sudanic Africa, and the Trans-Saharan Trade. London: C. Hurst.

- Fleisher, J.B. 2003. “Viewing stonetowns from the countryside: an archaeological approach to Swahili regional systems, AD 800–1500.” PhD diss., University of Virginia.

- Fleisher, J.B. 2014. “The complexity of public space at the Swahili town of Songo Mnara, Tanzania.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 35: 1–22.

- Fleisher, J.B. and LaViolette, A. 1999. “Elusive wattle-and-daub: finding the hidden majority in the archaeology of the Swahili.” Azania 34: 87–108.

- Fleisher, J.B. and Sulas, F. 2015. “Deciphering public spaces in urban contexts: geophysical survey, multi-element soil analysis, and artefact distributions at the 15th-16th-century AD Swahili settlement of Songo Mnara, Tanzania.” Journal of Archaeological Science 55: 55–70.

- Foreman, P.G. et al. “Writing about slavery/teaching about slavery: this might help.” Community-sourced document https://docs.google.com/document/d/1A4TEdDgYslX-hlKezLodMIM71My3KTN0zxRv0IQTOQs/mobilebasic Site accessed 2 July 2020.

- Freeman-Grenville, G.S.P. 1975. The East African Coast: Select Documents from the First to the Earlier Nineteenth Century. London: Collins.

- Garlake, P.S. 1966. The Early Islamic Architecture of the East African Coast. Nairobi: Oxford University Press.

- Haines, J.J. 2018. “Landscape transformation under slavery, indenture, and imperial projects in Bras d’Eau National Park, Mauritius.” Journal of African Diaspora Archaeology and Heritage 7: 131–164.

- Haines, J.J. 2020. “Mauritian indentured labour and plantation household archaeology.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 55: 509–527.

- Haour, A. 2011. “The early medieval slave trade of the central Sahel: archaeological and historical considerations.” In Slavery in Africa: Archaeology and Memory, edited by P.J. Lane and K.C. MacDonald, 61–78. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Hartwig, G. 1977. “Changing forms of servitude among the Kerebe of Tanzania.” In Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives, edited by I. Kopytoff and S. Miers, 261–286. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Hirth, F. and Rockhill, W.W. 1911. Chau Ju-kua, Chu-fan-chi [His Work on the Chinese and Arab Trade in the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries]. St Petersburg: Printing Office of the Imperial Academy of Sciences.

- Horton, M.C. 1996. Shanga: The Archaeology of a Muslim Trading Community on the Coast of East Africa. London: British Institute in Eastern Africa.

- Hunwick, J.O. 1992. “Black slaves in the Mediterranean World: introduction to a neglected aspect of the African diaspora.” Slavery & Abolition 13: 5–38.

- Jaubert, P.A. 1975. La Géographie d’Edrisi, Amsterdam: Philo Press.

- Kankpeyeng, B.W. 2009. “The slave trade in northern Ghana: landmarks, legacies and connections.” Slavery & Abolition 30: 209–221.

- Kirkman, J.S. 1952. “The excavations at Kilepwa: an introduction to the medieval archaeology of the Kenya Coast.” Antiquaries Journal 32: 168–184.

- Kopytoff, I. and Miers, S. 1977. “Introduction: African ‘slavery’ as an institution of marginality.” In Slavery in Africa: Historical and Anthropological Perspectives, edited by S. Miers and I. Kopytoff, 3–84. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.

- Kusimba, C.M. 2004. “Archaeology of slavery in East Africa.” African Archaeological Review 21: 59–88.

- LaViolette, A. and Fleisher, J.B. 2018. “Developments in rural life on the Eastern African coast, AD 700–1500.” Journal of Field Archaeology 43: 380–398.

- MacEachern, S. 1993. “Selling the iron for their shackles: Wandala Montagnard interactions in northern Cameroon.” Journal of African History 34: 247–270.

- Marshall, L.W. 2018. “Consumer choice and beads in fugitive slave villages in nineteenth-century Kenya.” International Journal of Historical Archaeology 23: 103–138.

- Mathew, G. 1959. “Songo Mnara.” Tanganyika Notes and Records 53: 154–160.

- Miers, S. 2003. “Slavery: a question of definition.” Slavery & Abolition 24(2): 1–16.

- Miller, J.C. 2008. “Women as slaves and owners of slaves: experiences from Africa, the Indian Ocean World, and the Early Atlantic.” In Women and Slavery, Volume 1: Africa, the Indian Ocean World, and the Medieval North Atlantic, edited by G. Campbell, S. Miers and J.C. Miller, 1–40. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Orser, C.E. 1990. “Archaeological approaches to New World plantation slavery.” Archaeological Method and Theory 2: 111–154.

- Pawlowicz, M. n.d. “Regional survey of Songo Mnara Island.” Unpublished manuscript.

- Pawlowicz, M. 2012. “Modelling the Swahili past: the archaeology of Mikindani in southern coastal Tanzania.” Azania: Archaeological Research in Africa 47: 488–508.

- Pawlowicz, M. 2019. “Beyond commoner and elite in Swahili society: re-examination of archaeological materials from Gede, Kenya.” African Archaeological Review 36: 213–248.

- Perbi, A. A. 2004. A History of Indigenous Slavery in Ghana: from the 15th to the 19th Century. Accra: Sub-Saharan Publishers.

- Pollard, E. and Ichumbaki, E.B. 2017. “Why land here? Ports and harbours in southeast Tanzania in the early second millennium AD.” Journal of Island and Coastal Archaeology 12: 459–489.

- Popović, A. 1999. The Revolt of African Slaves in Iraq in the 3rd/9th Century. Princeton: Markus Wiener.

- Pouwels, R.L. 2002. “Eastern Africa and the Indian Ocean to 1800: reviewing relations in historical perspective.” International Journal of African Historical Studies 35: 385–425.

- Pradines, S. and Blanchard, P. 2005. “Kilwa al-mulûk. Premier bilan des travaux de conservation-restauration et des fouilles archéologiques dans la baie de Kilwa, Tanzanie.” Annales Islamologiques 39: 25–80.

- Radimilahy, C. 1998. “Mahilaka: an archaeological investigation of an early town in northwestern Madagascar.” PhD diss., Uppsala University.

- Raffield, B. 2019. “The slave markets of the Viking world: comparative perspectives on an ‘invisible archaeology’.” Slavery & Abolition 40: 682–705.

- Robertshaw, P.T. and Duncan, W. 2008. “African slavery: archaeology and decentralized societies.” In Invisible Citizens: Captives and Their Consequences, edited by C. Cameron, 57–79. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Rüther, H., Held, C., Bhurtha, R., Schroeder, R. and Wessels, S. 2012. “From point cloud to textured model, the Zamani laser scanning pipeline in heritage documentation.” South African Journal of Geomatics 1: 44–59.

- Sachau, E.G. 1964 Alberuni's India: An Account of the Religion, Philosophy, Literature, Geography, Chronology, Astronomy, Customs, Laws and Astrology of India about A.D. 1030. Lahore: S. Chand & Co.

- Salau, M.B. 2009. “Slaves in a Muslim city: a survey of slavery in nineteenth century Kano.” In Slavery, Islam and Diaspora, edited by B. Mirzai, I.M. Montana and P.E. Lovejoy, 91–102. Trenton: Africa World Press.

- Samford, P. 1996. “The archaeology of African-American slavery and material culture.” William and Mary Quarterly 53: 87–114.

- Seetah, K. 2015. “The archaeology of Mauritius”. Antiquity 89: 922–939.

- Shepherd, G. 1982. “The making of the Swahili: a view from the southern end of the East African coast.” Paideuma 28: 129–147.

- Soumonni, E.A. 2003. “Lacustrine villages in south Benin as refuges from the slave trade.” In Fighting the Slave Trade: West African Strategies, edited by S.A. Diouf, 3–14. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Stahl, A.B. 2008. “The slave trade as practice and memory. What are the issues for archaeologists?” In Invisible Citizens: Captives and Their Consequences, edited by C. Cameron, 25–56. Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press.

- Stine, L.F., Cabak, M.A. and Groover, M.D. 1996. “Blue beads as African-American cultural symbols.” Historical Archaeology 30: 49–75.

- Sulas, F. and Madella, M. 2012. “Archaeology at the micro-scale: micromorphology and phytoliths at a Swahili stonetown.” Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 4: 145–159.

- Talhami, G.H. 1977. “The Zanj rebellion reconsidered.” International Journal of African Historical Studies 10: 443–461.

- Trimingham, S. 1976. “The Arab geographers and the East African coast.” In East Africa and the Orient: Cultural Syntheses in Pre-Colonial Times, edited by H.N. Chittick and R. Rotberg, 115–146. London: Africana Publishing Company.

- Vernet, T. 2005. “Les cités-États Swahili de l’archipel de Lamu, 1585–1810: dynamiques endogènes, dynamiques exogènes” PhD diss., Université de Paris.

- Vernet, T. 2009. “Slave trade and slavery on the Swahili coast (1500–1750).” In Slavery, Islam and Diaspora, edited by B. Mirzai, I.M. Montana and P.E. Lovejoy, 37–76. Trenton: Africa World Press.

- Wood, M. 2009 “The glass beads from Hlamba Mlonga, Zimbabwe: classification, context, and interpretation.” Journal of African Archaeology 7: 219–238.

- Wood, M. 2011. “Report on beads and glass finds for the 2011 excavations at Songo Mnara.” Unpublished report.

- Wynne-Jones, S. 2013. “The public life of the Swahili stonehouse, 14th–15th centuries AD.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 32: 759–773.

- Wynne-Jones, S. 2018. “The social composition of Swahili society.” In The Swahili World, edited by Stephanie Wynne-Jones and Adria LaViolette, 293-305. New York: Routledge.

- Yentsch, A.E. 1994a. A Chesapeake Family and Their Slaves: A Study in Historical Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Yentsch, A.E. 1994b. “Beads as silent witnesses of an African-American past: social identity and the artifacts of slavery in Annapolis, Maryland.” Kroeber Anthropological Society Papers 79: 44–60.

- Ylvisaker, M. 1979. Lamu in the Nineteenth Century: Land, Trade, and Politics. Boston: Boston University Press.