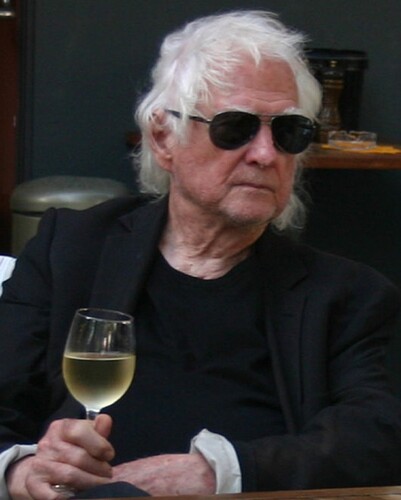

Ed Wilmsen passed away on 6 June 2023 in a hospital bed in Berlin with his loving wife, Anne Griffiths, by his side. He was 91. Ed’s parents had emigrated from Germany to the United States just before he was born and settled in Galveston, Texas. He had dual citizenship, so fortunately he could choose to live where his meagre retirement finances would best allow. Ed led a very full academic and research life, and most obituaries will explain his early doctoral research on humans of the Paleoindian Period and bison hunting at the Lindenmeier site in the Colorado foothills of the Rocky Mountains. With this beginning, it was only natural that he would decide to expand his research to the hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari, who were thought at that time to be a kind of cultural fossil preserving an ancient yet nearly undisturbed hunting and gathering life — one that had once characterised all of humankind.

Ed started what was intended to be a single season of research in northwestern Botswana in 1973, but the project grew into his life’s work, stretching over 50 years. My wife, Josie, and I left Maun in northern Botswana after four years just a few weeks before Ed arrived, so we were not there to witness his disillusionment when he found that cattle and small stock had been grazing around the supposedly pristine waterhole at /Kae/kae, probably for decades, if not longer. Also making use of the waterhole was a small population of resident Herero and Tswana agropastoralists. Clearly, the expected ‘Pleistocene window’ into our distant past that Ed had been led to expect lacked context and had suffered considerable anthropological amnesia and laundering in its translation to paper.

My intent here is not to belabour the tenets of what has become known as the ‘Kalahari Debate,’ which broadened the time depth and extent of interaction between different ethnic groups in southern Africa and its history. That can be found in the myriad of seminal books and articles that Ed produced over that half-century. I was a co-author on some of his works that focused on archaeological subjects. Instead of numbering or listing his many writings and grants, I am contributing these words because I worked closely in the Kalahari with Ed — both in the field and as a writer — for most of his working years.

I want instead to present a picture of Ed the person, as I saw and knew him. When we first met in 1979–80, of course I knew of his reputation as a former editor of the esteemed archaeological journal American Antiquity. So, I was not surprised by the depth and breadth of his anthropological knowledge and his ability to craft a sentence with just the right nuance and perfect word. What surprised me was the first time we met up with a few of his Ju/’hoan colleagues from /Kae/kae. They must have hitched a ride into Maun on a vehicle with some Herero who had also come to Maun. Their journey was long, uncomfortable and risky due to the way that San were often treated in town. But what surprised me was the manner in which they greeted Ed. Not only were they obviously delighted and overjoyed to see him, but they were so euphoric that they plucked thin sticks off the bushes on the side of the road to switch him over the backside like a small child. Obviously during his time in /Kae/kae he had not only picked up some of the language, but his outgoing personality, ability to speak the Ju/’hoan language and knowledge of the culture had made him such deep and lasting friends that they thought nothing of treating him like a naughty boy when they met. His knowledge of the Ju/’hoan language, and my knowledge of SeTswana, greatly facilitated our working collaboration.

I was more than a bit jealous of the closeness and familiarity of the greeting that his return had prompted. Not only that, but the /Kae/kae friends he made reflected the cultural diversity he found around the waterhole — not just Ju/’hoansi, but also Herero, Tswana and others. During our years working together Ed always tried to incorporate these diverse friends in our work when possible. I remember so fondly the morning laughter during the excavations at Matlapaneng on the edge of the Okavango Delta when we all tried to greet one another every day in each other’s language (Ju/’hoan, OtjiHerero, ThiMbukushu, TjiKalanga, SeTswana, English and even Afrikaans).

Ed also loved to cook, something at which he excelled, even in the bush. I will never forget the time we were given a bucket of whole milk from the cattle-post. He managed to convert the milk into cottage cheese within a couple of days by wrapping and squeezing it in one of our clean dish towels and hanging it in a tree. Some of the cottage cheese was incorporated into a delicious lasagne. Another time we made pancakes over the campfire only to realise that we had forgotten to bring syrup. No problem — Ed just caramelised some sugar. And when we threw a party to celebrate the end of our excavation, Ed organised the local women to make a large barrel of fermented khadi, a traditional alcoholic beverage made using ripened wild Grewia berries, sugar and indigenous yeasts for fermentation. True to Ed’s style, everyone for miles around was invited, whether they worked for us or not. I was amused to see that several of the vinyl records people brought from home to play on our battery-operated record player were on the green ‘Great Zimbabwe’ label with a picture of the ruins. Some guests walked to the party, some came by bicycle and many arrived by donkey or, as one man put it, ‘My 4 × 4. It never gets stuck.’

That was Ed: ingenious, hard-working, highly intelligent, widely read and a skilled and prolific writer — but also an inventive and skilled cook who enjoyed the challenge of turning simple or wild ingredients into a quasi-gourmet meal. He was also a man always willing to mingle and throw a good party. The party at Bosutswe at the end of the excavation there became a legend that people remembered for years. I expect the precious memory of Ed blowing into a whistle while laughing and dancing around the campfire with everyone — including the dog — will be long-remembered. What I saw was a true man of the people, generous with his time and, with some, his resources.

Ed Wilmsen, a whip-smart anthropologist and archaeologist working in Africa with the gift of fitting in with a society under study, is not one who will be forgotten.