ABSTRACT

Marin Sanudo’s finances, family relationships, and choice of written vernacular are the three focal points of the present study. These hitherto only partially explored issues are addressed via a little known primary source. Sanudo’s handwritten submission for the Venetian redecima tax survey initiated in May 1514 is offered here in a philological first edition, with translation and contextualisation. His tax return discloses precise information about his housing interests, retail outlets, and overall income. It adds to our knowledge of the living arrangements in Ca’ Sanudo at S. Giacomo dell’Orio and suggests both tensions and collaboration within the Sanudo clan. Linguistically the document is intriguing. Cross comparison confirms that Sanudo’s written vernacular is not the linguistic impasto familiar from his historical works. His prose is revealed as less hybrid here than anywhere else in his output, with spelling, phonology, morphology, and lexis leaning strongly towards Venetian, and with Tuscan traits unobtrusive.

Introduction

The Diaries of Marin Sanudo, written between 1496 (when Sanudo was 30) and 1533 (less than three years before his death), are probably the most detailed daily record of events compiled by a single individual in early modern Europe and, together with Samuel Pepys’s shorter, private, and intensely personal diary, the most significant.Footnote1 In conjunction with his other historical and documentary writings, unpublished like the Diarii until the modern period, they have become the indispensable source for any serious study of Renaissance Venice: from diplomacy to public spectacle, from politics to institutional practice, from the councils of state to the state of public opinion, from mainland possessions to overseas territories, from law-and-order to war, from the fabric and sights of the city to the lives of individuals, and from religious life to fashion, prices, weather, and entertainment.Footnote2 The qualities of his best work, particularly the Diaries and the De origine, situ et magistratibus urbis Venetae, make Sanudo the pre-eminent Venetian historian of his generation.Footnote3

That Sanudo’s redecima tax return has never been fully published can at first glance seem no more than a minor symptom of the centuries-long neglect of his more important writings. As is by now well known, the halting path to publication and appreciation of his histories, diaries, and documentary accounts began as late as the first half of the nineteenth century,Footnote4 accompanied by an even slower build-up of studies on his biography, books, and language that has only reached critical mass in recent decades.Footnote5 However, like much in Sanudo’s paradoxical life and work this assumption needs to be nuanced. In reality his tax declaration came close to being the first discrete item of his prodigious written legacy to be transcribed directly from the archives by a major scholar and published in one of the volumes that initiated Sanudo criticism.

The existence of the declaration was revealed as early as 1837 thanks to the enthusiasm and pioneering archival work of Rawdon Brown (1806–1883), an eccentric Englishmen who had made Venice his home in the early nineteenth century, allied to the scholarship of his friend Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna, the outstanding Venetian antiquarian and bibliophile of his day.Footnote6 Together they excavated the Sanudo manuscripts, some of which both Brown and Cicogna owned, revealing for the first time their untapped riches.Footnote7 Cicogna’s monumental œuvre on Venetian inscriptions is filled with historical information about the city’s families, including Sanudo’s, and he quotes extensively on aspects of individuals and events from the Diarii without Italianising their distinctive vernacular.Footnote8 Brown had the foresight to appreciate Sanudo’s cultural importance and the energy to publicise it in the three volumes of his modestly titled Ragguagli, with extensive commented extracts copied from the Diaries and an admirable endeavour to contextualise his life and work supported by copious footnotes and helpful indices.Footnote9 Together they devised and had installed the handsome inscribed and crenellated plaque commemorating Sanudo that still adorns the outer wall of the family house at S. Croce no. 1758.Footnote10

It was Cicogna who provided Brown with a handwritten transcription, carried out from the original, of Sanudo’s tax return.Footnote11 However, Brown only went on to publish part of it (the first four of the eleven paragraphs of the document) in his Ragguagli, in a footnote about the Sanudo house. Even a cursory comparison with the edition offered in the present study reveals the strengths and limitations of the Cicogna-Brown fragment.Footnote12 Most of the essential information is conveyed and there is a genuine attempt to reproduce Sanudo’s layout and spellings. Cicogna’s interpretative transcription opens up Sanudo’s abbreviations but with sometimes mixed results. The rendering of Conseio d’i Pregadi (1, l. 1) ‘Senate’ as Consiglio de Pregadi is plausible but philologically misleading, and mio ‘my’ in place of the abbreviated nostro ‘our’ (2, l. 4) is an unfortunate slip. There are other sporadic misreadings of the original, such as che s’habia dar instead of the original ch’el se habia dar ‘that one should give’ (1, l. 1), luogo ‘place’ for fuogo ‘hearth, household’ (1, l. 2), et ancora ‘and again’ for e Andrea ‘and Andrea’ (1, l. 4), figlio di ‘son of’ for fo di ‘of the late’ (1, l. 4) and che ‘that’ for ch’è ‘that is’ (4, l. 3). Finally, Cicogna mistook Sanudo’s quirky <ch> nexus for <g>, leading him to transcribe chiesia ‘church’ (4, l. 1) as the more dialectal gesia. The passage from Sanudo’s will that Cicogna also transcribed for Brown is more surefooted but still has errors.Footnote13 In Cicogna’s defence Sanudo’s handwriting is not always straightforward. His tax return in particular, with his characteristically dense mercantesca script less neat than usual, is tricky to decipher in places and Cicogna did not have our technological aids at his disposal. The remainder of his transcription of the return has not been located and, as far as I am aware, no other edition has ever been attempted.

As one of only two surviving official declarations by Sanudo his tax return is self-evidently of historical interest. In particular it is a rich and unexplored source of information about Sanudo’s financial and family circumstances at the moment of Venice’s fundamental revision of tax policy during the war of the League of Cambrai, a process which he himself had just recorded and commented on. It also opens up a surprising perspective on Sanudo’s written vernacular. In the present study I therefore mine this newly edited document to generate considerations of fiscality, family, and language that are largely new to Sanudo studies. The contextual section on tax introduces the redecima process itself, against the background of Venice’s traditional fiscal arrangements and of its wartime contingencies. The following section on form and fiscality scrutinises the manuscript and layout of the historian’s tax return, his assets as they are listed in the document, and how his bill owed to the state was calculated by tax officials at the Rialto. It raises the question of why such a well-informed and patriotic observer as Sanudo should have delayed declaring his rather modest taxable income for many months after the due date. The chapter on family matters then considers the exceptional number of relatives evoked in the document and the partitioning of the Sanudo casa da statio at S. Giacomo dell’Orio implied in it. It points out that the wording of Sanudo’s return is suspiciously similar in parts to that of the redecima declarations of other members of the household. It concludes that underlying the historian’s apparently anodyne submission are complex family dynamics, involving living arrangements, co-ordination of tax declarations and financial mismanagement, which have never hitherto been investigated. It also suggests that the murky aspects of Sanudo’s finances, disclosed in passages of his Diaries and above all in his will, have been carefully papered over in his declaration. The edition itself, with the explicit criteria employed in its transcription and a full translation, follows these analytical chapters. I go on to use the information provided by the edition to undertake a close reading of Sanudo’s language in the document, with his Diaries and will as comparative textual sources and the declarations of the other taxpayers in S. Giacomo dell’Orio as corroboration. This reading confirms that the familiar hybridity of Sanudo’s prose, with its notoriously inextricable mix of Venetian, Tuscan, and Latin, is attenuated here. The historian’s vernacular emerges, instead, as closer to the largely unmixed written venexian used by all other taxpayers in his district, including his own half-brother Antonio and cousin Anzolo. My conclusion brings together the interlocking strands of the study.

The Tax Return

Context

In the terminology employed by Sanudo himself the document under scrutiny is the official declaration (MidV, nota), by household (MidV, rispeto al fuogo), of his personal circumstances (MidV, condition).Footnote14 Imposed by decree (MidV, parte) of the Senate, such declarations would enable the authorities to accurately evaluate individual taxable income. With this information they would levy, at the rate of 10%, the decima Tenth tax (MidV, dexima) within the framework of the new Venetian fiscal survey, the so-called redecima of 1514. The decima was a property tax, calculated and levied on the assessed rental value of immovables owned by Venetians (resident in the city or Dogado) and on the value of declared produce grown on any landholdings (MidV, possession) owned by them on the Terraferma.Footnote15 The decima could be raised one or more times per year by Senate decree.

Until 1463 Venetian receipts were derived essentially from indirect taxation in the form of duties on goods and transactions, reinforced in emergencies by forced loans repayable with interest. These loans were calculated on a percentage (usually 1%) of the taxable real estate of the wealthier part of the population and were based on individual returns checked by a committee of Savi. It was the huge pressure on state expenditure of the hostilities with the Ottomans (1463–1478) and the increasing delays in loan interest repayments that led the authorities to resort, reluctantly but with increasing regularity, to direct taxation from 1463.Footnote16 This took the form of the non-reimbursable Tenth tax (MidV, dexima persa). It was based in principle on regular full declarations by individual Venetians of their circumstances, updated as and when these altered and validated by revised parish estimi. In reality, the redecima of 1514 was the first comprehensive survey carried out since 1463.Footnote17 After half a century of the fiscal status quo, the authorities were finally concerned to systematically revise their picture of the taxable immovables and land held by Venetian residents (essentially patricians, citizens, and better-off artisans), with exact details of location, legal standing, and rateable value. For the root-and-branch 1514 review handwritten returns were to be deposited by individuals within three months at the official tax office, the X Savi sopra le Decime, situated on the Riva del Vin just at the foot of the Rialto bridge.Footnote18 Two scribes (EV/MidV, scrivani) in the office then officially acknowledged receipt of the document, signing and countersigning it. The taxpayer, or their named representative, proceeded to guarantee the accuracy of the document by legal oath (in Sanudo’s case he himself swore before the scribes). The Tenth tax to be applied to Sanudo and others was then calculated by a tax official on the basis of the new data supplied, with calculations, total taxable income after deductions and final decima amount recorded on the return itself. The trustworthiness of the declarations was to be cross-checked against a vast valuation exercise of property ownership in Venice and the Terraferma, with fines imposable on those underdeclaring. The returns were filed away in folders by date and ward of residence (EV/MidV, confin or contrà).

The practical problem in 1514 and in the preceding decades had been that the previous comprehensive survey of 1463 was obviously outdated and necessarily incomplete, even allowing for the fact that taxpayers were obliged to update their circumstances and that a vast paper trail had therefore been amassed over the years. In the context of five consecutive years of the war of the League of Cambrai, with its urban and rural devastation and huge government outlays in cash, exceptional levels of direct taxation were urgently required. The new review, backed by an independent register of rateable values (EV/MidV/ModV, catastico < Gk. κατάστιχον ‘business register’, literally ‘(register) by line’), had therefore become imperative for the state’s finances. The much-delayed redecima was finally triggered by the huge fire that swept through the Rialto area on the night of 10 January 1514, wiping out the old tax documentation: a fire described by Sanudo in an astonishing piece of eyewitness reportage to rival Pepys’s great fire of London narrative.Footnote19 His normal curiosity was sharpened because his own property interests were at risk. He was anxious in particular about the crucial money-spinning ostaria di la Campana (‘the Bell Inn’), sited in a narrow calle off the Pescaria, that he would go on to declare in his tax return.Footnote20 The inn was saved, but the blaze devastated the offices of the X Savi.Footnote21 While it is true that the authorities still had access to the amounts Venetians had paid in previous decima rounds, they had now lost the records legally detailing their property and landholdings.Footnote22 It became imperative to remedy this situation immediately in order to prevent loss of revenue. The Senate decree of 23 May 1514 spelled out the new measures:

Che per auctorità di questo Consejo, tutti quelli che per virtù di le leze nostre sono obligati pagar dexime fra termine de mexi tre proximi, siano tenuti dar in nota a l’oficio predito di X savii con suo sacramento la condition sua, videlicet tutte sue case et altri beni in questa terra et possesion et altri beni di fuora ubligati pagar decime, et li acrescimenti per lor fati, o per compride, o per altro, et dove sono i beni et quello i scuodeno de cadauno in suo nome proprio particular, et distintamente senza alcuna diminution né fraude.Footnote23

On 28 May 1514, the decree was publicised in all Venetian churches:

Fo publicato per le chiexie di questa terra la parte presa in Pregadi, di dar in nota ai X savii cadaun la sua condition, per esser brusado i libri, in termine di tre mexi, sub poena.Footnote24

Oddly enough, for a highly-informed patriot and stickler for protocol who had followed the legal process closely and reported on it, Sanudo only submitted his circumstances eight months later. The first taxpayer of his district to declare did so on 6 June 1514.

Form and Fiscality

The manuscript of Sanudo’s tax return is in the Archivio di Stato di Venezia (ASV), Dieci Savi sopra le decime a Rialto, Condizioni di decima, busta 33 (S. Giacomo dell’Orio), filza 56/67. It is one of around 80 submissions in the folder, of which some 70 were handed in during the period immediately following the announcement of the 1514 redecima.Footnote25 The remainder are updates submitted from 1517 to 1524. File 56/67 consists of two sheets of paper, c. 40 cm × c. 29 cm, designated a, b and c, d, respectively at the bottom by a scribe at the X Savi. Side c is blank while d displays the name of the relevant ward (S. Iaco de Lorio, Sanudo’s local parish) and underneath it the file number (no. 56, no. 67). Almost all of side a is taken up by Sanudo’s return, written in black ink, irregularly bleached but still legible (). Both pages have largish rips in the middle. These jagged tears, found on all submissions, are perforations caused by the desk pins that the declarations were stuck on by staff at the X Savi. They impede the reading of afito ‘rent’ (7, l. 1) and ut supra ‘as above’ (7, l. 2) but the context allows the lacunae to be confidently reconstructed. At the foot of the page are the two statements of receipt by the scribes (from patrician families), Tomado Michiel and Pandolfo Moroxini, the former confirming that Sanudo himself swore the oath (zurada per el dito): 1514. Adì 26 zener apresentada a io [sic] Tomado Michiel aj X Savij e zurada p(er) el dito. Pandolfo Morox(ini) aj X Savij s(oto)s(crivo). Side b displays the calculations of the tax official, first for Sanudo then for his brother Lunardo. The calculations are identical:

P(er) Mari(n) p(er) Xa de cond(ition) per la ½: duc(at)j 56 d(enari)j 4. Vie(n) £p(arvorum) 11 d(enar)j 2 p(izol)i 26 // Paga in fia v(echi)a p(er) l(a) ½ 857 = £p(arvorum) 11 d(enar)j 3 p(izoli) 20 // Cala p(er) p(izoli) 26.

P(er) L(unar)do Sanudo p(er) Xa de cond(ition): £p(arvorum) 11 d(enar)j 2 p(izoli) 26 // Paga in fia v(echi)a p(er) l(a) ½ 857 = £p(arvorum) 11 d(enar)j 3 p(izoli) 20 // Cala p(er) p(izoli) 26.

They show, first, a taxable income of 56 ducats, 4 denari,Footnote26 for each of the two brothers, yielding a decima payment each of £11 3d. 26p. in lire di piccoli (EV/MidV, lire de pizoli). Beneath this is recorded what they paid under the old system, again identical for both at £11 3d. 20p. The official then recorded the drop between the two (cala per pizoli 26). One notes that Lunardo Sanudo’s name has been written in full while Sanudo himself is simply called, almost familiarly, Marin.

Family Values

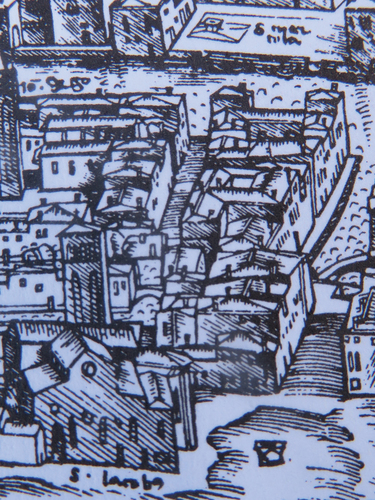

The prominence of family in Sanudo’s will is normal.Footnote27 In his tax return, it is quite remarkable. The Sanudo clan of S. Giacomo dell’Orio are revealed as occupying and sharing ownership of three different living quarters within the family palazzo. This domus magna straddles the southern area between the two main arteries radiating down from either side of the Fondaco dei Turchi at the approaches to the Ponte del Megio (). The magnificent Fondaco structure on the Grand Canal in northern S. Croce, known at the time as the residence of the Marquis of Ferrara, gave its name to the two streets bounding the Sanudo dwelling and cited in the return: the fondamenta del Marchese (di Ferara) (2, l. 1; 3, l. 1) and the salizà dil Marchexe (9, l. 1). Sanudo himself occupied one of the two discrete groups of apartments facing the fondamenta and canal (3, ll. 1–2), the Renaissance exterior of which is still in situ on what is now the Fondamenta del Megio ().Footnote28 According to both his return and will, he also owned the freehold (stabile libero) on half of the caxa facing the salizà, occupied by his half-brother Antonio (9) and later by Antonio’s son Hieronimo.Footnote29 It is not without significance that the separate living areas of the family members cited are specified as houses (caxa: 2, l. 1; 3, l. 1; 9, l. 1). These self-contained quarters or town houses within a domus magna, common across the city, were known as caxe da statio.Footnote30 The splitting and sharing of Ca’ Sanudo is reflected in the repeated use of the verb divider (2, l. 1; 3, l. 1; 9, l. 2). The restructuring of the building in the summer of 1506 which produced the tripartite layout was a traumatic process that caused friction between the Sanudi and a fracas in the Collegio involving the Doge himself and his chief steward. The tone of Sanudo’s eyewitness report of the incident suggests that he himself was relaxed about the outcome.Footnote31

The property portfolio shared by Sanudo and relatives is, to judge by the information in the return, rather modest although the estimated annual rental value of Ca’ Sanudo itself was a very respectable 125 ducats. The portfolio is local and stretches across the sestiere from S. Simion Grando (san Simion Propheta: 10, l. 2) in the west (rental value 20 ducats), via S. Giacomo dell’Orio (san Jacomo di Lorio: 4, l. 1) worth 134 ducats, to the Rialto outlets in the contiguous sestiere of S. Polo in the east (5, 6, 7, 8) yielding 262 ducats.Footnote32 It is noteworthy that Marin and Lunardo declare no property or land on the Terraferma. Few Venetians of their standing were without a smallholding in the Padovano or Trevisano at this time.

Sanudo’s relatives appear in nine of the eleven paragraphs of the document.Footnote33 Aside from resident siblings, cousins, and a nephew one notes the following. The prestigious name of his father Lunardo, whom he venerated and who died in Rome on a mission as Venetian ambassador (orator) when Sanudo was 10 years old, frames the return at the start (1, l. 2) and, very unusually for a tax declaration, at the finish (11, l. 1).Footnote34 A cluster of what feel like affectionate references stand out. They include his beloved sister Sanu(d)a (10, l. 6),Footnote35 his mother,Footnote36 and his mother’s brother Alexandro Venier (10, ll. 2–3),Footnote37 lord of Sanguinetto (Sanudo usually employs the dialect forms Sanguanè, Sanguanedo) in the Veronese, with whom Sanudo spent some of his teenage years and whose son, Marcantonio, was viewed by the diarist as the male heir he never had.Footnote38 We learn (10, ll. 1–5) that Venier bequeathed to Marin and Lunardo the group of three houses in the S. Simion Propheta parish, in the upper storey of one of which Lunardo would eventually reside.Footnote39 Discreetly present in the declaration is Lunardo himself, nine years Sanudo’s junior and joint submitter, although it is clear whose is the guiding hand.Footnote40 Curiously, Lunardo’s actual place of residence is left ambiguous in the submission, although the assumption must be that he resided with his brother. One wonders if Lunardo already occupied his eventual dwelling at S. Simion Propheta, previously notified to the tax authorities. In the return it is vaguely classified by Sanudo as a ‘caxa, pagava de fito duc(at)j 15, è <hora> meza ruinada e parte inhabitabile’ (10, ll. 3–4). If deemed habitable its rental value would undoubtedly have increased. Does the embarrassment over this ambiguity, which might prove fiscally beneficial to his younger brother, explain the historian’s reticence to submit? One notices that Sanudo’s handwriting in the return is less assured than normal and that when describing the house in question he stumbles uncharacteristically over his wording, as he does in his final tortuous statement (11, ll. 2–3).

That the relations between the historian and his younger brother were complex is suggested by three disturbing extracts from the Diaries. On 19 December 1516, less than two years after submitting the redecima return, Sanudo spent a night in custody, an irate patrician Zuan Soranzo having made a citizen’s arrest on him for an allegedly unpaid debt.Footnote41 It is unlikely to be a coincidence that in April 1516 Lunardo had put Sanudo’s name up for an elected post that the diarist expressly considered too minor for him. Rather than accept, Sanudo had rashly promised to pay an unaffordable loan of 400 ducats to the Signoria.Footnote42 On 6 August 1516 he donated 500 ducats, via the Pisani bank, and was elected to the Senate with full voting rights.Footnote43 A subsequent speech of his to the Senate, in the presence of the Doge, makes clear that the gesture had bled him dry.Footnote44

However, it is Sanudo’s will – a mixture of self-justification, resentment, economic messiness, and generosity – that lays bare the choppy financial undercurrents of the diarist’s life. This murkiness involves Marin and the rather shadowy figure of Lunardo in particular but also draws in Sanudo’s more politically and financially successful half-brothers, Alvise and Antonio, and his apparently opportunistic nephew Andrea.Footnote45 The testament discloses that soon after his tax submission Sanudo’s chronic money problems led him to take the drastic measure of selling off Lunardo’s share of the Bell Inn and nearby shops in order to cover his own debts. The share was bought up by Antonio and Andrea (son of the half-brother Alvise who years before had almost ruined Marin’s and Lunardo’s legacy) at a generous 8% interest. According to Sanudo, Lunardo himself went on to use 100 ducats of the cash realised from the sell-off to settle some debts of his own. To compensate for liquidating his younger sibling’s assets Sanudo thenceforth took it upon himself to pay Lunardo’s decima bills and cede his personal rental revenue to him. In a further complication, Sanudo’s own share of one of the three shops somehow fell into Andrea’s hands because of what is described as a ‘mix-up’ (impiastro) at the Cazude debt offices.Footnote46 Finally, Sanudo planned in his will to leave his one-year-old nephew Marin, son of Lunardo, some of his most precious manuscript books upon the child’s coming of age. However, the legacy was conditional on his brother not contesting the will.Footnote47 In the end the plan came to nothing as Sanudo had to sell off his study to pay creditors.Footnote48

In the busta for S. Giacomo dell’Orio there are cases where members of a family list their declaration on the same form (nos. 3–4, 9, 18, 24, 35–38, 39, 73–74). Sanudo went further. Not only did he submit jointly with his younger brother. He also appears to have been involved in the drafting of the submission of Antonio and Andrea. One’s suspicion, aroused by a glancing remark in his return (1, ll. 3–4), is endorsed by the strikingly identical wording of parts of Antonio’s and Andrea’s own declaration ([no. 68], 28 September 1514). The sums declared are, of course, identical. It is noticeable, too, that the detail and order of retail outlets declared by his cousin Anzolo Sanudo and brothers (no. 33, 21 August 1514) again replicate his. On that same day Sanudo authenticated by oath the declaration (no. 32) of Anzolo’s 21-year-old son Francesco. In the light of this family co-ordination, of the turmoil that lay just below the surface of his financial affairs, and of a tardy submission, Sanudo’s laconic tax return looks a little less transparent.

The Text

Editorial Criteria

As in his Diaries and other writings Sanudo makes heavy use of abbreviations. I open these out within round brackets. Frequent are the following signs. Diagonal stroke on <m> misier ‘Mr, Esqu(ire)’ (except for two cases where it stands for the following <ar> on marchese/marchexe ‘marquis’). Diagonal stroke on <s> sier ‘Mr’. Diagonal stroke on indicating following <ar> or <er>. Diagonal stroke on <d> representing following <r>. Horizontal bar on the tail of <p> per ‘for, by’, <ar> or <ra>. Swash on <p> indicating following <r> or <re>. Line above <p> representing following <re>. Squiggle above <q> standing for <ua> or <ue>. Wavy line over <s> san ‘saint’. Isolated <q> before a first name = quondam ‘the late’. Bow over <nro>, <nra>, <nri> nostro, nostra, nostri ‘our’. Ubiquitous is <n> or <m>, whether internal or final, signalled by a bow over the preceding vowel. The Tironian 9 stands for the segment <con> in Conseio d’i Pregadi (1, l. 1). The traditional Latin manuscript abbreviation <V3> on the end of the surname Venier (10, ll. 27–28) I transcribe as <um>. In a number of cases familiar names are simply shortened, with no abbreviation sign added, e.g., Franc(esc)o (2, l. 2; 3, l. 2) and S(igno)rie (11, l. 2). I have left superscript letters unaltered. Sanudo writes misier in its abbreviated form as <m> bisected by a diagonal stroke. I prefer this spelling to missier, the later form of the word in Venetian. When Sanudo was writing, the dominant variant was misier, and the diarist was nothing if not a traditionalist. In any case, on the two occasions he wrote the word in full, he used misier.Footnote49 Sanudo appears to make a careful distinction in the document between sier ‘Mr’ and the higher status misier. I have signalled the latter in the translation by placing ‘Mr’ before the name and ‘Esq.’ after it.

There are no letters missing by mistake in the original. I do not transcribe the illegible start of a word on 10, l. 4 (before Una altra caxeta) scored out by Sanudo. Words whose original position has been altered as an afterthought by Sanudo, employing a looped copy-editing sign, are placed within angle brackets. Letters or words added by Sanudo with an insertion mark are underlined and placed in angle brackets. Illegible passages are indicated conventionally by three dots within square brackets. Illegible passages that can be securely reconstructed are placed within square brackets. In most cases the distribution of upper- and lowercase letters in the original is not consistent. I follow modern practice, also regularising Sanudo’s sometimes haphazard word-separation practice. I detach preposition and article, except on del, dil ‘of the’ and al ‘at (the)’, and attach the article to compound relatives with qual ‘which’. Sanudo employs <u> for both /u/ and /v/. I distinguish them in my transcription following modern convention. Otherwise, I respect the diarist’s spelling variants and also retain final <j> = /i/. Short Latin inserts in vernacular prose came spontaneously to Venetian civil servants, notaries, and those patricians who like Sanudo had received a Humanist education. After careful consideration, I decided for the sake of clarity to italicise them here although they are not marked out in any way by Sanudo himself.

Accents are absent from Sanudo’s original. Those added to my edition follow modern Italian practice. I have also inserted apostrophes, which are never present in the original, e.g., ch’è for che ‘which is’ (2, l. 3), l’hostaria for lhostaria ‘the inn’ (5, l. 1) and pre’ for pre ‘priest’ (full form prevede) at 9, l. 1. I also add the apostrophe in d’i Pregadi and in the surname d’i Cavalieri (7, l. 1), where the partitive di in both cases was a Venetian rapid-speech variant of dei or deli. Punctuation is largely absent from the tax declaration as it is from most of Sanudo’s writings.Footnote50 The modern punctation I apply seeks to convey the rhythms of the diarist’s unadorned style. Sanudo clearly indicates his paragraphs by isolating the initial word (usually item) and by indenting the text that follows. Instead, I number each paragraph in bold and mark its end with a double slash. To further facilitate cross-referencing, lines in the edition are marked with a single slash and, unless they occur within a word, with a subscript number.

Edition and Translation

Per obedir la p(ar)te presa in el (Con)[se]io d’i P(re)gadi ch’el se habia dar in nota la sua co(n)dition 1/ rispeto al fuogo ut in ea, nui Marin e Lunardo Sanudo fo di m(isier) Lunardo 2/ <fo d(e) m(isier) Mari(n)> demo in nota in q(ue)sto modo: cadaum di nui p(er) la sua parte sicome etia(m) 3/ ha dato s(ier) Ant(oni)o Sanudo n(ost)ro fradelo e And(re)a n(ost)ro nepote fo di m(isier) Alvise. 4 //

Una caxa su la fondame(n)ta del m(ar)chese di Ferara, laq(ua)l dividesemo co(n) el q(uondam) m(isier) 1/ Anzolo Sanudo e f(rade)lj q(uondam) m(isier) Franc(esc)o, stimà duc(at)j 45 tuta di fito. A nui Mari(n) e L(unard)o 2/ tocha il 4°, ch’è duc(at)j 5 g(ros)i 15 p(er) uno de nui fradelli. E cussì fo posto a le (de)x(i)me 3/ a co(n)to di nui 4 fradeli. Habita al p(resen)te And(re)a n(ost)ro nepote. 4 //

Item. Una caxa su la fo(n)dame(n)ta dita, divisa p(er) mità con m(isier) Anzo<l>o Sanudo e f(radel)j 1/ fo di m(isier) Franc(esc)o sop(ra)scrito, in laq(ua)l habito mi Mari(n) Sanudo. Stimà duc(at)j 40. 2/ A nui fradelli tocha duc(at)j 20. Vien p(er) cadauno duc(at)j 5. 3//

Item. Una altra caxa, pagemo livello duc(at)j 16 a la chiesia di s(an) Jac(om)o di Lorio, 1/ si soleva afitar duc(at)j 25 tuta – hora è divisa e la n(ost)ra p(ar)te inhabitabile – 2/ ch’è duc(at)j 9 di più dil livello si paga. Ne aspeta a nui fradelli duc(at)j 4½. Vien p(er) uno duc(at)j uno g(ros)i 3. 3//

Item. L’hostaria dila Campana, p(r)o indevisa co(n) n(ost)ri cusini sop(ra)scriti, laq(ua)l tien 1/ afito dona Balsarina osta. Paga per <t>uta duc(at)j 205. 2//

Item. 1a botega di b(ar)bier, tien m(aistr)o B(e)n(e)to da Crema e And(re)a barbieri. Afito paga 1/ a l’an(n)o duc(at)j 24 p(er) mità ut supra. 2//

Item. 1a botega di b(ar)bier, tien a[fito] m(aistr)o Za(n)e d’i Cavalieri da B(er)gamo. Paga 1/ a l’an(n)o duc(at)j 17 p(er) mità u[t supra]. 2//

Item. 1a botega di caleger, tie(n) [m(aistr)o] B(e)n(e)to Caleger e (con)p(agni). Paga duc(at)j 16 a l’an(n)o. 1/ Che sumano tuto ostaria e botege duc(at)j 262 a l’an(n)o, diqual aspetta 2/ a nui 4 fradelli duc(at)j 131. Tocha p(er) uno duc(at)j 32 g(ros)i 18. 3//

Item. Una caxa su la salizà dil m(ar)chexe laqual fo di p(re’) Nic(ol)ò B(er)nardini, stimà 1/ duc(at)j 40 a l’an(n)o, divisa tra n(ost)ri cuxini. Et nui ne tocha duc(at)j 20. 2/ Vien p(er) uno duc(at)j 5. In laq(ua)l n(ost)ra mità al presente habita s(ier) Ant(oni)o Sanudo n(ost)ro f(rade)lo. 3//

Item. Demo in nota come fesemo trar e meter a n(ost)ro conto alcune 1/ caxe poste in la co(n)trà di s(an) Sim<i>o(n) P(r)opheta, q(ua)l ne lassò el q(uondam) m(isier) Alex(andr)o Venier/u(m). Una caxa, pagava de fito duc(at)j 15, è <hora> meza ruinada e parte 3/ inhabitabile. Una altra caxeta, pagava duc(at)j 5, laq(ua)l è in una corte 4/ et è ruinata e inhabitabile. Che sum(m)avano duc(at)j 20. Dilqual fito si scuode 5/ per terzo, zoè li do terzi nui Marin e L(unar)do Sanudo e l’altro terzo Sanuda 6/ n(ost)ra sorella, moier di m(isier) Zua(n) Malip(ier)o in vita soa. Item. E una caxa da 7/ saze(n)te di soto, pagava duc(at)j 5, q(ua)l etia(m) si da p(er) amor de Dio – e cussì lassò 8/ la q(uondam) n(ost)ra madre – q(ua)l è in ruina e no(n) si afita 0. 9//

Leq(ua)l tute cosse soprascrite nui Mari(n) e L(unar)do Sanudo fo di m(isier) L(unar)do demo in nota 1/ aziò le S(igno)rie Vostre possa far debitori, p(er) quanto aspeta a la p(ar)te n(ost)ra, cadauno 2/ p(er) la sua parte come fosemo messi a l’in(sie)me, la portio(n) di cadauno a sso conto. 3//

To comply with the decree passed in the Senate that one should declare one’s circumstances as per household, we Marin and Lunardo Sanudo, sons of the late Mr Lunardo Esq. (of Mr Marin Esq.), declare in the following way: each of us by individual share, as was also done by Mr Antonio Sanudo our brother and Andrea our nephew, son of the late Mr Alvise Esq.

A house on the embankment of the Marquis of Ferrara that we split with the late Mr Anzolo Sanudo Esq. and brothers, sons of the late Mr Francesco Esq. Overall rental value reckoned at 45 ducats. We Marin and Lunardo are liable for the fourth part of this, i.e., 5 ducats 15 grossi for each of us brothers. And that is how it was rated for the Tenth tax on the account of us four brothers. At present it is occupied by our nephew Andrea.

Item. A house on the said embankment shared half-and-half with Mr Anzolo Sanudo Esq. and brothers, of the late Mr Francesco Esq. mentioned above, in which I Marin Sanudo live. Valued at 40 ducats. We brothers are liable for 20 ducats. That comes to 5 ducats each.

Item. Another house (leased for 16 ducats from the church of San Jacomo di Lorio) that used to be rented out for 25 ducats all told is now split up, with our part uninhabitable, and that is 9 ducats more than the lease paid. We brothers are liable for 4½ ducats, which comes to 1 ducat and 3 grossi each.

Item. The Bell Inn, held in common with our above-mentioned cousins and let out to Mrs Balsarina the innkeeper. It pays overall 205 ducats.

Item. A barber’s shop run by the barbers Master Beneto da Crema and Andrea. The annual rent yields 24 ducats, split in half as above.

Item. A barber’s shop run by Master Zane d’i Cavalieri from Bergamo. It yields 17 ducats annually, split in half as above.

Item. A cobbler’s shop run by Master Beneto Shoemaker and fellow workers. It yields 16 ducats a year. Altogether, inn and shops come to 262 ducats a year, of which we four brothers are entitled to 131 ducats. Each of us is liable for 32 ducats and 18 grossi.

Item. A house on the street of the Marquis, that once belonged to Father Nicolò Bernardini, valued at 40 ducats a year and shared with our cousins. We are liable for 20 ducats, which comes to 5 ducats each. At present Mr Antonio Sanudo our brother lives in our half of it.

Item. We declare that we have taken over and put on our tax account some houses located in the district of San Simion Propheta that were left to us by the late Mr Alexandro Venierum Esq. One house, that yielded 15 ducats rent, is now partly uninhabitable. Another small house, yielding 5 ducats, is in a courtyard and is derelict and uninhabitable. Altogether that comes to 20 ducats. This rent is collected in thirds, that is two thirds to us, Marin and Lunardo Sanudo, and the other third to Sanuda, our sister, wife of Mr Zuan Malipiero Esq. when he was alive. And a terraced house below which yielded 5 ducats is also let out free, for charity, as was our late mother’s wish. It is derelict and yields zero rent.

All the things itemised above we Marin and Lunardo, sons of the late Mr Lunardo Esq., do declare so that your Lordships can calculate what each of us owes – as we were jointly assessed – as per individual account.]

Language

At first glance the language of his tax return seems to stand out within Sanudo’s vast production for its surprisingly limited hybridity. It is, therefore, potentially important evidence for the nature of Sanudo’s own Venetian. In order to gauge precisely how mixed the language of his submission is, I weigh up the features in it that can be linked to the Latinising and Tuscanising components of the tripartite linguistic impasto that typifies the Diarii. I consider in parallel how prevalent such elements are among Sanudo’s fellow taxpayers in his own parish. I then isolate those features that are more consistently Venetian than in the Diaries. I conclude by assessing the Venetian lexis of the return.

The question of Sanudo’s language was long neglected. Two fine articles, the first by Gaetano Cozzi and the second by Laura Lepschy, brought the issue to the critical forefront.Footnote51 Not only did Cozzi highlight that Sanudo’s rejection of Humanist Latin, and adoption of the vernacular, had profound consequences for the way he conceived and wrote history. He also intuited that the diarist’s vernacular was essentially the written koine of Venetian officialdom, calling it the ‘volgare cancelleresco veneziano’ or ‘veneziano cancelleresco’. Lepschy refined and enriched the latter intuition, giving a broader northern Italian cultural dimension to Sanudo’s koine. Above all, she was the first to address the linguistic coherence of Sanudo’s medium and to dissect his vernacular into its variably intersecting constituent components, Venetian, Tuscan, Latin. Subsequent critical work has developed these insights.Footnote52

In Venice, the beginnings of the code-mixing trend that culminated in Sanudo are already detectable in official and high-register writing in the mid-fifteenth century. The process can be tracked in detail in the following decades through the vernacular decrees of the Ducal chancery and the statute-cum-membership books (mariegole) of the prestigious Scuola Grande confraternities in the city. At the outset Latinising elements were only sporadically visible in spelling, while Tuscan influence was generally limited to disambiguating third singular and plural verb forms (which are identical in all tenses in Venetian) and to the occasional maintenance of <t> in past participle endings as against the lenition of Venetian outcomes. The grammar of these texts remained essentially Venetian, with a high degree of predictability, and can be analysed as such.Footnote53 The heyday of textual hybridity was reached in the decades either side of 1500. It was brought to an end by the imminent and puristic codification of the vernacular by Bembo on the basis of Golden Age Tuscan models. The pressure exerted by this codification not only ousted the composite written medium that came naturally to Sanudo. It fairly rapidly restricted the use of unmarked Venetian itself in the sixteenth century to occasional, sometimes unintentional, appearances in formal documents, although venexian maintained a modest and more lasting presence in letters, inventories, technical documentation and in the inscriptions of the trade-based Scuole Piccole confraternities.

Francesco Crifò characterised the language of the Diarii as follows:

Nei Diarii la componente latina è tutt’altro che residuale: ogni aspetto della lingua, dalla grafia alla fonomorfologia, dalla sintassi al lessico, ne è pervasa […] La base della lingua dei Diarii consiste però in sostanza di un composto insolubile di veneziano e toscano.Footnote54

Does this description fit the language of Sanudo’s tax return? As far as Latin is concerned, it corresponds only partially. Sanudo’s trademark bureaucratic inserts do figure in the return, and more frequently so than in the other parish submissions: ut in ea (1, l. 2); etiam (1, l. 3; 10, l. 8); quondam (2, l. 1 passim); item (3, l. 1 passim); ut supra (6, l. 2; 7, l. 2). What is surprising is how little Sanudo’s spelling in the tax return is influenced by Latin when compared both to the Diarii and even to some of the other redecima submissions. Latinising <h> on habia (1, l. 1), ha (1, l. 4), habita (2, l. 4; 9, l. 3), habito (3, l. 2), inhabitabile (4, l. 2; 10, l. 4), hostaria (5, l. 1), hora (10, l. 3), and etymologising <t> on condition (l, l. 1), portion (11, l. 3), are banal and frequent across the parish declarations. More interesting is the absence in Sanudo’s submission of the Humanist-influenced etymological <ct> nexus which occurs with relatively high frequency in the Diarii and also from time to time in the tax returns:Footnote55 fito ‘rent’ (2, l. 2; 5, l. 2; 6, l. 1; 10, l. 5), afitar ‘to rent’ (4, l. 2; 10, l. 9), aspeta (4, l. 3; 11, l. 2), aspetta (8, l. 2) and not (a)ficto, afictar, or aspecta.Footnote56 The same applies to the absence of the <pt> nexus found in the Diaries and sometimes in the other tax returns: soprascrito (3, l. 2; 11, l. 1), soprascriti (5, l. 1), and not soprascripto/i. It is noticeable that the etymologising et ‘and’ which dominates Sanudo’s Diarii and will is five times less frequent than e in the tax declaration.

One’s initial impression is that the language of Sanudo’s declaration is hardly ‘un composto insolubile di veneziano e toscano’. This is borne out by closer scrutiny. Tuscan influences on Sanudo’s Venetian are light-touch compared to the Diarii and substantially in line with those affecting other S. Giacomo dell’Orio submissions. All our parish tax returns are in Venetian, with differences in tone and register conditioned by social background and education. Sanudo’s does not stand out in this respect, and this is hardly surprising. He was not writing for posterity here but for precise Venetian officials whom he may well have known and who probably knew who he was. The residual Tuscanising elements found in it are arguably carry-overs from the Diaries. There is the preferential use of di over Venetian de ‘of’ (15 times as against 4) and the corresponding partitives, especially dil (4, l. 3; 9, l. 1) rather than Venetian (and Tuscan) del (2, l. 1). Forms such as dil are, in fact, better described as pseudo- or hyper-Tuscanisms, sometimes found in northern Italian chancery practice and appearing occasionally in the writing of educated Venetians.Footnote57 Vowel raising is also present in the third-singular impersonal pronoun: si soleva (4, l. 2), si paga (4, l. 3), si scuode (10, l. 5) vs se habia (1, l. 1). Disambiguation of third-singular and third-plural verb forms is very frequent in the Diarii. This Tuscan influence appears occasionally in the return: sumano […] ostaria e botege (8, l. 2) and summavano ducatj 20 (10, l. 5) vs tocha ducatj 20 (3, l. 3; 8, l. 3) and vien […] ducatj 5 (9, l. 3). It is common across the tax submissions, occasionally producing hypercorrect forms, such as sono agreeing with a singular subject, never found in Sanudo. Finally, there are two past participle endings with <t> preserved, dato ‘given’ (1, l. 4) and ruinata ‘ruined’ (10, l. 5), against four with Venetian lenition: stimà ‘estimated’ (2, l. 2; 3, l. 2; 9, l. 1) and ruinada (10, l. 3). Tuscan past-participle types with <t> occur sporadically in those tax declarations that show strong Humanist or chancery influence in their script. Lexically, nepote ‘nephew’ (1, 2, l. 4) is a near Tuscanism that may be influenced by Latin nepotem. Nepote is also Sanudo’s preferred form in the Diarii, with the Venetian nevodo cropping up in the codicil to his will, his last recorded statement.Footnote58

A few key features are more fully Venetian in the return than in the Diarii. In spelling one is struck by the high frequency of single consonants where Tuscan requires gemination: rispeto (1, l. 2), sicome (1, l. 3), Ferara (2, l. 1), fradelj (2, l. 2; 2, l. 4; 3, l. 1), tocha (2, l. 3 passim), grosi (2, l. 3 passim), tuta (2, l. 2), fito (2, l. 2 passim), dita ‘aforementioned’ (3, l. 1), soprascrito (3, l. 2), afitar (4, l. 2), afito (6, l. 1), botega (6, l. 1; 7, l. 1; 8, l. 1), botege (8, l. 2), tuto (8, l. 2), meza ‘half’ (10, l. 3), soto (10, l. 8), aspeta (11, l. 2). Truncated infinitives are dominant in the Diarii. Here they are exclusive: obedir (1, l. 1), dar (1, l. 1), afitar (4, l. 2), trar ‘take, extract’ (10, l. 1), meter (10, l. 1), far (11, l. 2). The same applies to Venetian rules for final vowel apocope or maintenance which here are respected in full:Footnote59 condition (1, l. 1), Marin (1, l. 2), misier (1, l. 2 passim), cadaum (1, l. 3), livello (4, l. 1 passim), inhabitabile, caleger (8, l. 1), barbier (6, l. 1; 7, l. 1), laqual (9, l. 1), sier (9, l. 3), dilqual (10, l. 5), moier (10, l. 7), madre (10, l. 9), laqual (11, l. 1), portion (11, l. 3), Malipiero (10, l. 7), amor (10, l. 8). The masculine singular definite article in the return is twice Venetian el (1, l. 1; 2, l. 1), with one instance of il (2, l. 3), while the partitive in el (1, l. 1) for nel stands out.

Finally, the Venetian dimensions of Sanudo’s vocabulary – grammatical, semantic, and civilisational – catch the eye. These range from the phonologically Venetian obedir ‘to obey’ (1, l. 1), unexpectedly taking a direct object, to the verb tochar, with its preservation of the traditional <ch> nexus for /k/ and its meaning of ‘to be liable for’. Among terms for relatives one notes that fradel(l)i ‘brothers’ always manifests intervocalic T > /d/, cuxini ‘cousins’ (9, l. 2) preserves the traditional <x> = /z/ spelling (as do the ubiquitous caxa and marchexe ‘marquis’ at 9, l. 1), and moier ‘wife’ is preferred to Tuscan moglie. Zoè ‘that is’ (10, l. 6) and aziò ‘in order that’ (11, l. 2) have the Venetian voiceless affricate represented by <z> rather than the Tuscan palatal /ʧ/, while lassò, unlike Italian lasciò, has no voiceless fricative /ʃ/. Among subject pronouns ‘we’ is always the traditional nui (1, l. 2 passim), with its relic metaphonic raising of stressed /o/ > /u/. Venetian indirect object pronoun ne ‘to us’ (9, l. 2) is used rather than Tuscan ci. Somewhat unexpectedly in a formal document, Sanudo employs the innovative disjunctive variant mi ‘me’ for the first-person subject pronoun rather than the expected io found traditionally and in some other returns. Interestingly io is preferred by Sanudo in the Diarii, in those passages where he refers to himself, and also in his will. The obligatory third-singular atonic subject pronoun clitic el appears in ch’el se habia ‘that one should’ vs Tuscan che si abbia. The spelling of cosse ‘things’ ['kᴐse] (11, l. 1) reveals the unvoiced intervocalic /s/ which has persisted into ModV/CV. The verbs ruinar, sumar, and scuoder have characteristic Venetian forms compared to Italian rovinare, sommare, and scuotere, as does the noun mità ‘half’ (3, l. 1 passim).

Present and past historic tenses in the return are Venetian, with the first person plural forms demo ‘we give’ (1, l. 3), pagemo ‘we pay’ (4, l. 1) prominent among the former and dividesemo ‘we shared, split’ (2, l. 1), fesemo ‘we had, did’ (10, l. 1), fosemo ‘we were’ (11, l. 3) among the latter.Footnote60 The city, its inhabitants and its institutions are foregrounded in the submission. Very Venetian are the trade names caleger ‘cobbler, shoemaker’ (6, 7, 8, l. 1), with <g> = /g/, pronounced [kae'gɛr] in ModV/CV, barbier ‘barber’ (6, 7, l. 1), osta ‘landlady’ (5, l. 2), and maistro ‘master’ (6, 7, 8, l. 1), alongside pre’ ‘reverend, priest’ (9, l. 1) and the titles misier and sier. Sanudo records the names of the shopworkers running his shared outlets: dona Balsarina (for the inn: 5, l. 2), Beneto da Crema and his assistant Andrea (for the first barber’s shop: 6, l. 1), Zane d’i Cavalieri da Bergamo (for the second: 7, l. 1), and the master shoemaker Beneto Caleger (8, l. 1). One notices the role, here, of emigration from Venetian-occupied Lombardy. The Venetian monetary system figures with ducati and grosi ‘grossi’ (featuring Venetian voiceless single /s/ again) and institutional life with condition, livello ‘lease’, parte, fuogo, (a)fito, Conseio d’i Pregadi,Footnote61 dexime, conto ‘account’ (10, l. 1; 11, l. 3). The topography of Sanudo’s beloved Venice comes alive in contrà ‘parish, ward’ (10, l. 2),Footnote62 corte ‘courtyard’ (10, l. 4),Footnote63 caxa da sazente ‘annex or terraced house for rent’ (10, ll. 7–8),Footnote64 salizà ‘early paved street in Venice’ (9, l. 1),Footnote65 fondamenta ‘canal embankment with buildings on one side’ (2, 3, l. 1),Footnote66 and (h)ostaria ‘inn’ (5, l.1; 8, l. 2).Footnote67

Conclusion

While Sanudo’s tax submission for the redecima, edited and presented here for the first time, is arguably a minor document within his vast output, our study has shown that it is nonetheless rich in potential insights for historians, linguists, and students of Venice. It reveals the real-estate portfolio, with precise values, from which the chronicler derived his living. It provides the names of the artisans who ran his establishments. It indicates locations for his properties that can be mapped on to de’ Barbari’s contemporary view of Venice. It shows how modest Sanudo’s financial means were and, read alongside troubling passages in his will and Diaries, helps to contextualise the financial mismanagement that may, according to David Chambers,Footnote68 have hampered his public career. At the same time, it puts into perspective Sanudo’s remarkable and largely unrewarded efforts to record the events and key documentation of the crucial decades in Venetian history through which he lived. In addition, it sheds interesting light on the complex and sometimes strained dynamics of Ca’ Sanudo at S. Giacomo dell’Orio and suggests that a reappraisal of Marin’s relationship with his family, and in particular with his younger brother Lunardo, is necessary. Finally, it is unique in revealing a tantalising glimpse of Sanudo’s native Venetian, largely shorn of its Tuscan and Latin elements and similar to that of his fellow parishioners.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The c. 40,000 manuscript folio pages of Sanudo’s Diaries, bound by him at his own expense into 59 volumes, are housed in Venice’s Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana (BNM), It. VII, 228–86 (= 9215–73). The only complete edition remains the monumental, splendid but imperfect I Diarii di Marino Sanuto ed. by Rinaldo Fulin, Federico Stefani, Nicolò Barozzi, Guglielmo Berchet, and Marco Allegri, 58 vols (Venice: Visentini, 1879–1903). Henceforth DMS followed by the volume and column numbers.

2 For an example of the diarist’s centrality see the reconstruction of Venetian theatrical life in the early decades of the Cinquecento, based on Sanudo’s eyewitness accounts, in Ronnie Ferguson, ‘Venues and Staging in Ruzante’s Theatre: A Practitioner’s Experience’, in The Renaissance Theatre: Texts, Performance, Design, ed. by Christopher Cairns (Aldershot: Ashgate, 1999), pp. 146–59. Ironically, it is what makes Sanudo most valuable as a historical observer – unvarnished language and style, avoidance of uplift and teleology, wide net of curiosity, meticulous recording of information and documentation – that effectively debarred him in Renaissance Venice from the status of historian that he craved. For decades he even hesitated over how to title his endeavours, oscillating between assessments as downbeat as ‘il successo di le cosse’ (DMS, i, 1, 1 January 1496) and, on occasion, as pugnaciously grandiloquent as: ‘la mia vera historia’ (DMS, v, 5, 1 April 1503) or ‘la historia d’i tempi, opera grande e copiosa’ (DMS, xx, 532, 15 September 1515). By the time he was finally rewarded for his efforts by the Council of Ten with an annual pension of 150 ducats, but only on the grudging condition that he did not abandon his Diaries and that he make them available to Pietro Bembo for the latter’s history of Venice (after having initially refused to do so), he could confidently call them: ‘53 volumi di questa ystoria et diaria’ (DMS, liv, 596, 19 September 1531). Within two months his work and name were cited in the Senate by no less a personage than Alvise Mocenigo (DMS, lv, 103, 2 November 1531). At this point he appears to have considered himself, unequivocally, a historian: ‘la fama ho de historico’ (DMS, liii, 173, 27 April 1530). He was not wide of the mark when he claimed in his letter to the Ten (September 1531): ‘et questo è certissimo: niun scrittor mai farà cosa bona delle historie moderne, non vedando la mia diaria, in la qual è compreso ogni cosa seguita’. The letter is transcribed in Guglielmo Berchet, Prefazione to the 1903 volume of the DMS, pp. 114–16 (p. 115).

3 On the qualities that distinguish Sanudo as a historian, both from other Venetian diarists of the period and from official Humanist historiographers, see the fundamental observations in Gaetano Cozzi, ‘Marin Sanudo il Giovane: dalla cronaca alla storia’, in La storiografia veneziana fino al secolo XVI: aspetti e problemi, ed. by Agostino Pertusi (Florence: Olschki, 1970), pp. 333–58. They include documentary richness, accuracy and systematicity, and the relentless seeking out of primary sources to illuminate what he correctly recognised as key events and societal shifts. Robert Finlay’s sweeping judgment that ‘Sanuto’s [sic] greatest weakness as a historian was not his lack of discrimination but his inability to impose an order on his sources, to perceive a pattern in the events he recorded’ is no longer sustainable. Robert Finlay, ‘Politics in the Diaries of Marino Sanuto’, Renaissance Quarterly, 33.4 (1980), pp. 585–98 (p. 587).

4 It began with the publication by the Marciana librarian Pietro Bettio of a laudable but flawed edition of Sanudo’s first historical work, the Commentarii della Guerra di Ferrara tra li Viniziani ed il Duca Ercole d’Este nel 1482 (Venice: Picotti, 1829). This was followed by Rawdon Brown’s edition of the youthful travelogue Itinerario di Marino Sanuto per la Terraferma veneziana nel 1485 (Padua: Tipografia del Seminario, 1847), now superseded by Marin Sanudo, Itinerario per la Terraferma veneta, ed. by Gian Maria Varanini (Rome: Viella, 2014). Rinaldo Fulin, the driving force behind the project to publish the Diaries, then edited Sanudo’s account of the French invasion of Italy: La spedizione di Carlo VIII (Venice: Visentini, 1883). The period of the great publication enterprise of the Diarii by Fulin and his team (1879–1903) also saw a scholarly partial edition by Giovanni Monticolo of Sanudo’s lives of the Doges: Le vite dei Dogi di Marin Sanudo vol. 1 (Città di Castello: Lapi, 1900), now completed by Angela Caracciolo Aricò’s editions: Le vite dei Dogi (1474–1494), 2 vols (Padua: Antenore, 1989–2001) and Le vite dei Dogi (1423–1474), 2 vols (Venice: La Malcontenta, 1999–2004). Caracciolo Aricò also published Sanudo’s unique vernacular monograph on Venice: De origine, situ et magistratibus urbis Venetae ovvero La Città di Venetia (1493–1530) (Milan: Cisalpina-La Goliardica, 1980), followed by a revised edition (Venice: Centro di Studi Medievali e Rinascimentali ‘E. A. Cicogna’, 2011).

5 I confine myself to a selection of fundamental contributions. Berchet, Prefazione, pp. 8–164; Cozzi; Giorgio Padoan, ‘La raccolta di testi teatrali di Marin Sanudo’, Italia Medioevale e Umanistica, 13 (1970), pp. 181–203; David S. Chambers, ‘Marin Sanudo, camerlengo a Verona (1501–1502)’, Archivio Veneto, 108 (1977), pp. 37–66; Angela Caracciolo Aricò, ‘Marin Sanudo il Giovane precursore di Francesco Sansovino’, Lettere Italiane, 31.3 (1979), pp. 419–37; Finlay, ‘Politics in the Diaries of Marino Sanuto’; Anna Laura Lepschy, ‘La lingua dei Diarii di Sanudo’, in her Varietà linguistiche e pluralità di codici nel Rinascimento (Florence: Olschki, 1996), pp. 33–51; David. S. Chambers, ‘The Diaries of Marin Sanudo: Personal and Public Crises’, in his Individuals and Institutions in Renaissance Italy (Aldershot: Ashgate Variorum, 1998), pp. 1–33; Christiane Neerfeld, ‘Historia per forma di Diaria’. La cronachistica veneziana contemporanea a cavallo tra Quattro e Cincequento (Venice: Istituto Veneto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti, 2006); Angela Caracciolo Aricò, ‘Marin Sanudo il Giovane: le opere e lo stile’, Studi Veneziani, 55 (2008), pp. 351–90; Alfredo Buonopane, ‘Marin Sanudo e gli antiquissimi epitaphii’, in Marin Sanudo, Itinerario per la Terraferma, pp. 95–104; Illaria Morresi, ‘Una visita alla biblioteca di Marin Sanudo’, Rinascimento, 66 (2016), pp. 167–210; Francesco Crifò, I ‘Diarii’ di Marin Sanudo: sondaggi filologici e linguistici (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2016).

6 Cicogna called Brown ‘il chiarissimo e amantissimo delle venete cose inglese sir Rawdon Brown abitante in Venezia da vari anni’. From a handwritten note on the flyleaf of Cicogna’s manuscript copy of Sanudo’s De origine, now in Venice’s Biblioteca del Museo Correr (BMC), Cicogna MS 969.

7 For the Diarii themselves Cicogna and Brown actually used the fine copy made by the last official historian of the Republic Francesco Donà (1744–1815) and now held in the BNM, It. VII, 419–77 (= 10065–123). Sanudo’s original, taken to Vienna by the Austrian authorities in 1805, was only returned after 1866.

8 Emmanuele Antonio Cicogna, Delle inscrizioni veneziane, 6 vols (Venice: Orlandelli, vol. I; The Author vols II–VI, 1824–53).

9 Rawdon Brown, Ragguagli sulla vita e sulle opere di Marin Sanuto, 3 vols (Venice: Alvisopoli, 1837–1838), i, pp. 169–70, n. 2. On Brown see Alfredo Reumont, ‘Rawdon Brown’, Archivio Storico Italiano, 149 (1985), pp. 170–83; Rawdon Brown and the Anglo-Venetian Relationship, ed. by Ralph A. Griffiths and John E. Law (Stroud: Nonsuch, 2005); John E. Law, ‘Marin Sanudo: le opere, la fortuna storiografica’, in Marin Sanudo, Itinerario per la Terraferma, pp. 81–94.

10 The plaque was paid for by Brown, with Cicogna drafting the text. The inscription is in Roman monumental capitals with black infilling and mid-high interpuncts. Its language, style, and absence of abbreviation marks replicate early-sixteenth century Latin inscriptional practice in Venice, although the crenellated frame is anachronistic. It reads: marini · leonardi · f · sanuti · viri · patr / rervm · venet · ital · orbis · q · universi / fide · solertia · copia · scriptoris / aetatis · svae · praestantissimi / domvm · vixit · obiit · q · pr · n · apr · mdxxxvi / contemplare · viator (‘Passer-by: behold the house of Marin Sanudo, son of Lunardo, who died here on the 4th of April 1536. His writings on Venice, Italy and the whole world were among the most outstanding of their time for trustworthiness, intelligence and abundance’). Sanudo planned an epitaph for his own grave and laid out an inscriptional text in Latin in his will. Brown was the first scholar to publish the will, using an archivist’s copy (Brown, Ragguagli, iii, pp. 213–31), and the wording of Sanudo’s ideal epitaph influenced Cicogna’s inscription. In the end, nothing came of Sanudo’s plans to be buried unfussily in the family plot in S. Zaccaria or S. Francesco della Vigna. His final resting place is unknown.

11 ‘Ecco la carta favoritaci dal Cicogna (Copia) 1514, 26 gennaro (m.v.)’. Brown, Ragguagli, i, p. 169.

12 In this comparison as in my own edition, examples are referenced to the original, with paragraph numbers (in bold) followed by the relevant line number.

13 Brown, Ragguagli, i, p. 183.

14 The chronological framework of Venetian underlying the present essay is: Early Venetian [EV] c. 1200 – c. 1500, Middle Venetian [MidV] c. 1500 – c. 1800, Modern Venetian [ModV] c. 1800 – c. 1950, Contemporary Venetian [CV] c. 1950 – the present. Each boundary marks a watershed moment where societal or cultural events with linguistic repercussions altered the status and/or structure of Venetian. 1200 conventionally represents the appearance of venexian in written texts. Around 1500 Tuscan was achieving consensus status among Italy’s elites and interfering with unmarked written Venetian. The grammatical codification of Tuscan → Italian that introduced writing-speech bilingualism to Venice was also imminent at that point.

15 Taxpayers’ returns had to specify the annual yields of what was grown on their holdings. The calculations of the tax officials show that they operated with a conversion chart allowing them to assign monetary value to yields by produce. The most lucrative emerge clearly as wine and wheat.

16 On Venetian fiscal policy in our period see Giuseppe Del Torre, Venezia e la terraferma dopo la guerra di Cambrai. Fiscalità e amministrazione (1515–1530) (Milan: Franco Angeli, 1986); Luciano Pezzolo, Il fisco dei Veneziani. Finanza pubblica ed economia tra XV e XVII secolo (Verona: Cierre, 2003).

17 The third redecima only took place in 1537.

18 The election, powers and procedures of the X Savi are outlined by Sanudo himself. See Caracciolo Aricò, De origine (2011), p. 110.

19 DMS, xvii, 458–64.

20 ‘Era un grandissimo fuogo e grandissimo vento de griego e tramontana con un fredo intollerabile. Et fu sonato campanò a Rialto dove tutti concorseno, sì quelli aveano volte e magazeni con mercadantie come li botegieri e altri aveano stabele a Rialto, tra li qual io Marin Sanudo fo di missier Lunardo vi corsi per aver parte in l’ostaria di la Campana, di la qual trazo el viver mio et paga di fitto ducati 205 oltra le botege da basso’ (DMS, xvii, 459). The bricked-up front of the inn on the first floor, and the fronts of the shops beneath, can still be detected in the Calle de l’Ostaria de la Campana at the Rialto off the Campo de la Pescaria. The inn, first recorded in the 1340s, survived until the nineteenth century. Bartolomeo Cecchetti, ‘La vita dei veneziani nel 1300. Parte II: il vitto’, Archivio Veneto, 30.2 (1885), pp. 278–334 (p. 332); Giuseppe Tassini, Curiosità veneziane (Venice: Filippi, 1970), pp. 468–69.

21 ‘Essendo brusate tutte le scriture di l’ofizio d’i Diexe savii sora le decime, el qual è de l’importantia ben nota a questo Consejo, se die trovar via et modo, con meno strepito sii possible, de reformar quelle et far li catastici, ch’è il fondamento di le decime, aziò ogniun pagi el dover suo per subvenir la terra in queste importantissime occurentie’. From the Senate decree of 23 May 1514 (DMS, xviii, 214–15).

22 Scrutiny of tax returns for 1514 and immediately succeeding years confirms that the authorities had access to the levy that individual Venetians had paid under the old tax regime (MidV, in fia vechia) and also to the outstanding debt register (MidV, fia d’i resti). This information certainly came from the surviving records of the Governadori dell’Intrade who collected tax receipts and those of the Cazude who sold off the assets of debtors. See Caracciolo Aricò, De origine (2011), pp. 101, 275 for Sanudo’s description of these offices.

23 DMS, xviii, 214–15.

24 DMS, xviii, 227.

25 I give approximate figures because a few items are missing and submissions are occasionally clumped.

26 For comparison, Polo Antonio Miani in his long and highly complex submission (no. 13) declared 171 ducats, while Pandolfo Ferigo Moroxini (no. 3) declared an astonishing 376 ducats worth of assets. Sanudo’s return is around average for the ward. However, it is important to bear in mind that the 56 ducats, 4 denari reported by him is not all real income, some of it simply being the notional value of his share of a property portfolio. His annual income boiled down to the rent due to him from the Campana inn (‘di la qual trazo el viver mio’: DMS, xvii, 459, 10 January 1514) and the three shops below it, cited in the return as 32 ducats, 18 grossi. At that point in time Sanudo apparently had no income from government posts or business investments.

27 The autograph will of 4 September 1533 is in the ASV, Sezione notarile, Testamenti in atti di Girolamo Canal, no. 546 (busta 191), while the dictated codicil of 4 April 1536 is in the ASV, Sezione notarile, Testamenti, Notaio Diotisalvi Benzon, no. 470 (busta 97). I cite them as Testament and Codicil, giving folio and paragraph numbers for the former and paragraph number for the latter.

28 For a contemporary description of the inside of Sanudo’s house see Morresi, ‘Una visita alla biblioteca’.

29 Testament, fol. 3r, 4.

30 Caxa da statio (or stacio) can also refer to a large residential house, usually in owner-occupation.

31 ‘Da poi disnar fo consejo di X. Et si comenzò a far li muri in la caxa, divisa tra nui li Sanudi, per via di sora gastaldi, di comandamento dil principe, col suo gastaldo’. The following morning ‘fossemo in Colegio a dolersi di Sanudi con Nicolò Brevio, gastaldo dil doxe. Et seguì gran parole; e il principe li admonì assai, e comandò la executione di la sententia e division, e cussì fu fata’ (DMS, vi, 376, 15–16 July 1506).

32 In the De origine (Caracciolo Aricò (2011), p. 27) Sanudo quotes different rental figures for inn and shops: ‘in Rialto […] el stabele qui è molto caro, testè siamo noi Sanuti, che in Pescharia nova habiamo un’hostaria chiamata “Della Campana”, sotto tutto botteghe – ed è picciol luogo – e tamen di quel coverto si cava più di ducati 800 di fitto ogni anno – ch’è cossa maravigliosa dil grande fitto è questo – e per esser in bono sito l’hostaria vero paga ducati 250, che paga più ch’el primo pallazzo della Terra, et questo – dirò cussì – è il primo stabile de Venetia per tanto coverto’. Sanudo is keen to make a point here, but the rent of 250 ducats certainly refers to a later date than that of the tax return, and the 800 probably applies to all the shops beneath the inn, not just those belonging to the Sanudi.

33 On Sanudo and his relatives see Berchet, Prefazione; Matteo Melchiorre, ‘Sanudo, Marino (il Giovane)’, in Dizionario Biografico degl Italiani (Rome: Istituto dell’Enciclopedia Italiana Treccani, 2017), xc, s.v. Sanudo’s late wife Cecilia d’i Prioli and two illegitimate daughters, Candiana and Bianca, do not figure in the return, although the daughters are in his will (Testament, fol. 2r, 2) and Cecilia’s death is recorded in DMS, vii, 672, 27 November 1508: ‘A dì 27. A nona morite la mia carissima consorte Cecilia, stata zorni 49 amalata. Idio li doni requie et riposso’. His older half-brother Alvise, who initially compromised Marin’s and Lunardo’s legacy by using it to finance his sister’s dowry, before fleeing to Syria, is mentioned here (1, l. 4). In a reference to the Syria escapade in his will (Testament, fol 3v, 6) Sanudo claims compensation from Alvise’s son and heir Andrea who is cited in the return at 1, l. 4; 2, l. 4. Sanudo’s eminent and benevolent paternal uncle Francesco, who steadied the situation and secured the young Marin’s future, appears in 2, l. 2; 3, l. 2. On Francesco see Cicogna, Delle inscrizioni, ii, pp. 112–13.

34 Anyone frequenting Sanudo is familiar with his trademark self-designation: io Marin Sanudo fo di (or de) m(isier) Lunardo. On headings and ex libris it becomes: Marini Sanuti Leonardi filii (patricii veneti).

35 ‘A dì 27, la matina. A hora di terza morite la mia carissima e dolcissima unica sorella uterina Sanua, moglie di sier Zuan Malipiero qu. sier Polo di Santa Maria Formosa, di una malatia fastidiosa, di laqual è stata la poverina martire in leto dal zorno di san Matia’ (DMS, xxiii, 534, 27 January 1517).

36 Sanudo calls his mother ‘chiarissima et excelentissima Madolina Letizia mia madre’ (DMS, xxiii, 534, 27 January 1517). One wonders what to make of Sanudo’s remarks in his will about her issuing exhorbitant IOUs on him – when, as a young man strapped for cash, he asked for relatively small amounts from her – and also taking for herself his rent from the Bell Inn (Testament, fol. 4r, 2). Was her behaviour disproportionate or was she already aware of profligate tendencies in her son that would lead him to live beyond his means? In this context David Chambers’s tentative suggestion that Sanudo’s later political career may have been hampered by rumours of financial extravagance during his one important posting, as camerlengo in Verona (1502–1503), may not be wide of the mark. Chambers, ‘Marin Sanudo, camerlengo’. Not long after submitting his tax return he admitted having spent the astonishing sum of 2,800 ducats on his book collection, then numbering over 2,000 volumes (DMS, xxii, 172, 28 April 1516). The magnificent library of some 6,500 manuscript and printed books that he eventually amassed (Testament, fol. 2r, 4) undoubtedly contributed to his straightened circumstances, as did his all-consuming commitment to his Diaries: ‘diventato vechio, infermo et povero, et più che povero, per non haver alcuna intrata, et è più de anni 30 che nulla ho guadagnato de officij, lassato di far li fatti mei, et atteso solo a scriver. Et si non fusse qualche mio parente che mi adiuta al viver, non haria mai potuto sustentar la mia vita’. Letter to the Council of Ten (September 1531) in Berchet, Prefazione, p.114.

37 The unexpected spelling Venierum in the return is the Latinisation of Veniero, the Veronese form of the Venetian patrician name.

38 When making him an executor Sanudo called him ‘misier Marco Antonio Venier, signor di Sanguanè, qual sempre ho reputà per fiol, et li ho infinite obligation’ (Testament, fol. 1v, 3).

39 Testament, fol. 3r, 5. Alexandro Venier died in November 1498 (DMS, ii, 101).

40 It emerges from a remark in the will that Marin and Lunardo had collaborated financially in the past by forming a fraterna company. Testament, fol. 4r, 2. Their complicity was vividly exemplified on 1 February 1499 (more veneto) when Sanudo, then Savio ai Ordeni, used insider information about the imminent crash of the Garzoni bank to instruct Lunardo to withdraw, in the nick of time, the 500 ducats left to his mother in the bank by the executors of the estate of his recently deceased uncle Alexandro Venier. DMS, ii, 391.

41 ‘La matina seguì l’oribel caso etc. che credendo io andar a San Marco justa il solito, fui de quel traditor di Zuan Soranzo fo di sier Marco, con el qual ho lite zà anni 6 con lui, et è segurissimo di più de ducati 100, et per resto di do sententie ducati 47 pareva dovesse aver per conti vechii, et per farmi oltrazo, a San Cassan mi fece retenir, et andai a Santo Marco da Zuaneto Dandolo […] Hor el dì drio uscii fuora, e questa vendeta non lasserò ad altri’. DMS, xxiii, 343, 18 December 1516.

42 DMS, xxii, 156–57, 23 April 1516.

43 DMS, xxii, 409.

44 ‘Son stà contento intrar questo anno d’i Pregadi con prestar a la Signoria tanto che ’l sento più de le forze mie’. DMS, xxiv, 328, 3 June 1517.

45 On Antonio, Alvise and Andrea Sanudo, their political careers, and the donations they gave to further them, see Cicogna, Delle inscrizioni, ii, p. 133. Unlike Sanudo, his two half-brothers were buried in S. Zaccaria with inscribed tombs. Sanudo’s report of Antonio’s death, aged 71, is in DMS, lv, 209–10, 1 December 1531.

46 ‘L’hostaria dila Campana, la mia parte dila qual Lunardo scuode i fitti, et do botege dabasso, e ave una sier Andrea Sanudo per certo impiastro a le Cazude […] La mia parte di l’hostaria di la Campana, Lunardo ha scosso tanti anni el fitto in locho dila soa parte fo venduta per mi, et mai è stà translatà dil mio nome […] L’è vero che la soa parte di l’hostaria di la Campana et tre botege da basso, soe, fo vendute per mia causa per un debito havia con sier Zuan Soranzo. Et dita parte la comprò sier Antonio Sanudo e sier Andrea a raxon di 8 per 100, che li stabili di Rialto val 3 per 100, et di questi danari ditto sier Lunardo tolse ducati 100 per pagar diversi officij dove l’era debitor […] Et è da saper sempre io ho pagà le dexime, e Lunardo scodeva li fitti, come apar alle Cazude et ali Governadori’. Testament, fol. 3r, 6–7; fol. 4r, 2.

47 Testament, fol. 4r, 3.

48 Codicil, IV.

49 In his De origine (Caracciolo Aricò (2011), p. 22), he admits (or deplores) that ‘al presente tempo […] a tutti si dà del misier’. In the Diarii he once uses misier in its figurative sense of ‘father-in-law’ (DMS, ii, 778).

50 To mark a pause Sanudo appears to use a mid-high period after ea and nota (1, l. 3) and similarly after moier and soa (10, l. 7). He employs the emphatic slash at paragraph end only twice (2, 9).

51 Cozzi; Lepschy, ‘La lingua dei Diarii di Sanudo’.

52 See Ivano Paccagnella, ‘La formazione del veneziano illustre’, in Varietà e continuità nella storia linguistica del Veneto (Rome: Il Calamo, 1997), pp. 179–203; Lorenzo Tomasin, Il volgare e la legge: storia linguistica del diritto veneziano (secoli. XIII-XVIII) (Padua: Esedra, 2001), pp. 57–123; Ronnie Ferguson, A Linguistic History of Venice (Florence: Olschki, 2007), pp. 188–211; Ronnie Ferguson, Saggi di lingua e cultura veneta (Padua: Cleup, 2013), pp. 58–61; Crifò.

53 A typical example is the decree of the Council of Ten (19 May 1451), concerning the Scuole Grandi, which was immediately copied into the mariegola of the Scuola Grande di S. Giovanni Evangelista. See ASV, Scuola Grande di S. Giovanni Evangelista, reg. 8, fol. 33v. The contemporary vernacular captions on Fra Mauro’s splendid mappa mundi are Venetian with a similarly light Tuscan patina. Ronnie Ferguson, Venetian Inscriptions: Vernacular Writing for Public Display in Medieval and Renaissance Venice (Cambridge: Legenda, 2021), pp. 282–90 [Corpus Inscriptions 62–66].

54 Crifò, p. 234.

55 For example, Ieronimo da(l)i Solimadi (submission nos 1 and 64) uses dicto ‘aforementioned’ and ficto ‘rent’.

56 See Crifò, pp. 251–52.

57 Both di and dil are used by the elite patricians Antonio Iustignan (submission no. 22) and Lodovico Venier, doctor (sub. no. 31). Dil and variants are also occasionally present in the diaries of Sanudo’s near contemporary Hieronomo d’i Prioli. See I Diarii di Girolamo Priuli [AA. 1499–1512], ed. by Roberto Cessi (Bologna: Zanichelli, 1912–41). For the occurrence of dil in Milanese chancery writing see Maurizio Vitale, La lingua volgare della cancelleria visconteo-sforzesca nel Quattrocento (Cisalpino: Varese, 1953), p. 87.

58 Codicil, II.

59 On singular nouns and adjectives, it deleted, and continues to delete, final /e/ and /o/ after the sonorants /n/ and /l/ on original paroxytones, but not on derivatives of original geminates.

60 The Italian equivalents of these present and past historic forms are diamo, paghiamo and dividemmo, facemmo, fummo.

61 Sanudo’s spelling of the Venetian title of the Senate is quite common in his fellow taxpayers’ submissions. One notes his maintenance of the traditional outcome of L + yod > /j/ in Conseio (also replicated in moier ‘wife’ at 10, l. 7). Lenition of T in Pregadi has gone no further than /d/, at least in writing, and the clipped form of de(l)i as d’i appears. However, there is evidence of considerable variation in these features in the returns, with outcomes such as Conseio de Pregai (Domenego Garuffa, sub. no. 17) where de replaces d’i and the degree of lenition on Pregai is complete. Like a few others, the patricians Alvixe Loredan (sub. no. 19) and Lodovico Venier (sub. no. 31) prefer Consegio de Pregadi and Consegio d’i Pregadi respectively, with L + yod > /ʤ/, the palatalised variant that would soon dominate in Venetian and become almost (but not quite) universal in ModV/CV.

62 Apocopated form of contrada ‘ward, district’. Not recorded until 1535 according to M. Cortelazzo, Dizionario veneziano della lingua e della cultura popolare nel XVI secolo (Bologna: La Linea, 2007). However, the process of lenition leading to it (contrata → contrada → contradha → contraa) is already documented in the thirteenth century.

63 From Med. Lat. curtis ‘yard, enclosure’, it is the equivalent of Tuscan/Italian cortile.

64 Caxa da/de/a sazente is literally a ‘tenant’s house’. From EV se(r)çente, se(r)zente, sa(r)çente, sa(r)zente ‘attendant, servant, scribe, tenant’ < Old French serge(a)nt, serjent ‘servant, vassal, liege, man-at-arms’, itself from serviens ‘servant’. The term was borrowed into EV from the feudal tenure system of serjeanty for commoners in the Frankish Levant. Initially employed by the Venetians for land tenants in their overseas possessions, particularly Crete, it was subsequently applied to houses for rent in Venice itself, whether caxete attached to, or in the courtyard of, a caxa da statio or else purpose-built rows of dwellings to let. The hesitation over the presence of /r/ is the result of contamination with a Latin-influenced parallel tradition of designating a tenant as segente or sigente ‘sitting’ (EV seço, seça, seçia ‘seat’).

65 From MidV saliz(z)o ‘flint(stone)’, this is the earliest example of salizà that I know of. The term is not attested before 1548 in Cortelazzo, Dizionario veneziano, s.v. In ModV/CV it is saliz(z)ada, with the truncated (originally past participle) ending restored. It is still applied in street signs to a range of thoroughfares in the city such as the busy Salizada S. Lio.

66 A characteristically Venetian term, from the neuter pl. fundāmenta of fundāmentum ‘foundation’ treated as a feminine noun.

67 Compared to Ital. osteria, (h)ostaria shows typical Veneto raising of /er/ > /ar/. Ostarie in Venice clustered around the Rialto and S. Marco in the medieval and Renaissance periods. That the (h)ostaria di la Campana, owned by the Sanudi, was unusual in being run by a landlady (dona Balsarina) is evident from the surviving records: Cecchetti, ‘La vita dei veneziani’, pp. 329–33.

68 See above note 36.