Abstract

Thin-section petrography was used to examine 36 samples of imported Early Bronze Age Combed vessels from Giza, Egypt. The samples come from fragmentary pots found in early Old Kingdom tombs of high officials, and the workers’ settlement at Heit el-Ghurab. Most date to the 4th Dynasty; coeval with the ARCANE Early Central Levant (ECL) 4 and Early Southern Levant (ESL) 5b periods. Results reveal a primary fabric with slight variations, containing material pointing to production centres close to Cretaceous formations outcropping in Central Lebanon, from Beirut and Tripoli. No fabrics from the southern Levant were identified. The results also demonstrate that by the early Old Kingdom, supply-lines to ceramic production centres in the Central Levant, linked to the acquisition of coniferous timbers, largely supplanted the diffuse networks of the Early Dynastic period.

Introduction

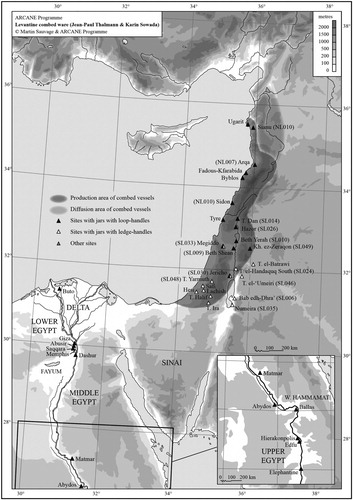

Flat-based jars, with vertical looped handles and a ‘combed’ exterior surface, are a ceramic hallmark for Early Bronze Age commodity exchange in the Levant (Marcus Citation2002: 409–11; Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014) (). A significant number are known in Egypt, yet scientific analysis of this material has been piecemeal. This paper outlines results from a programme of thin-section petrography on Levantine combed vessels found in Egypt dating to the Old Kingdom. Until now, no such data has been published for any imported pottery in Egypt for this period. The vessels in this study come from tombs at Giza, and also from the nearby workers’ settlement at Heit el-Ghurab on the Giza Plateau. The results provide important clarity as to the origin of Levantine imports to Egypt during the Old Kingdom, and have broader implications for our understanding of Egyptian-Levantine relations during the 3rd millennium.

Figure 1 Map of the eastern Mediterranean, showing the production and diffusion patterns of Combed vessels (Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: fig. 1).

The Combed jar in Egypt

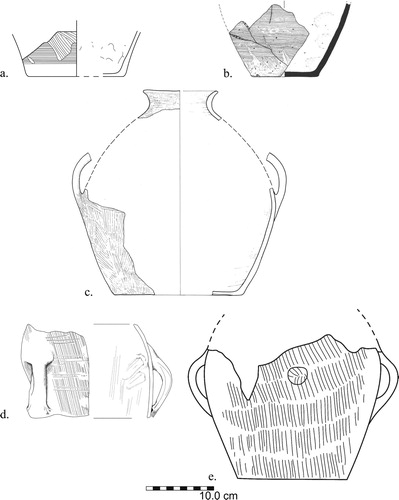

Early Combed jar forms appear in Egypt from Naqada IIIB/Dynasty 0. Examples appear at Hierakonpolis (Dynasty 0) (a) and Buto Stratum V (Dynasty 0) (b); others are known from Abydos Cemetery U and B (Hartung Citation2001: 208, fig. 457; Hartung et al. Citation2015: 305) (c).Footnote1 The type continues into the 1st Dynasty where they appear in the tomb of King Djer at Abydos (d–e). None are thus far known in the 2nd Dynasty: a small number of jugs and uncombed jars without handles come from Helwan, identified petrographically as coming from Lebanon (Köhler and Ownby Citation2011: 38–39). For imports generally, there is a gap in the archaeological record during this period, and also for the 3rd Dynasty. This may represent the accident of discovery and the failure of older excavations to retain sherds, rather than a cessation of trade (Kantor Citation1992: 20).Footnote2

Figure 2 Early Combed jars in Egypt.

a. Hierakonpolis, Locality 29A, Dynasty 0 (after Adams and Friedman Citation1992: fig. 8e).

b. Buto, Stratum V, Dynasty 0, TeF 87 T IXB 26/18 & 18a (Köhler Citation1998: pl. 68.9, 7312).

c. Abydos, Tomb U-y, early Naqada IIIB, U-y/1 (Hartung Citation2001: 208, fig. 457).

d. Tomb O (Djer), 1st Dynasty, Petrie Museum UC17388 (drawing K. Sowada).

e. Tomb O (Djer), 1st Dynasty, Ashmolean Museum E4031 (after Petrie Citation1902: pl. VIII.6).

The majority of known Combed jars from Egypt come from early 4th to late 6th Dynasty tombs belonging to members of the royal household, or high officials (Sowada Citation2009: 56–90). Indeed, during the early Old Kingdom, the titles of many high officials reveal they were related to the king, thus close to the organs of power. With Levantine expeditions state-controlled, the initial distribution of products was also managed by the administration. The presence of sherds at the Heit el-Ghurab settlement, established to house key workers during pyramid construction (Lehner Citation2007), also suggests that such vessels, once emptied of their original contents, circulated through the royal economy. As a result, Combed jars were prized for their contents and the symbolism of what they represented: access to royal grace and favour. The shape was even imitated in Egyptian clay as a form of status display (Sowada Citation2018).

Jars may have transported a variety of Levantine liquid commodities, including resins, wine, oils or mixtures of these. Textual sources and iconographic evidence identify ash-oil (cedar oil), and sefetj-oil as key products from Levantine expeditions (Gardiner Citation1969: 32; Marcolin and Espinel Citation2011: 576, 582; Sowada Citation2018: fig. 5). A Combed jar from the tomb of Djer (e) contained a vegetable oil (Serpico and White Citation1996: 134–35). Limited residue analysis has been conducted to date, with possible coniferous resin identified in one vessel, Boston MFA 47.1661 (Lucas and Harris Citation1989: 320; Sowada Citation2009: 161, 199).Footnote3

Close to 100 individual imported vessels, many intact or nearly complete, are known across Egypt from both cemeteries and settlements (Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: 371). This number includes both Combed jars and a small number of one-handled jugs. Although much debated over the years, limited scientific study has been conducted on their origins and contents. Moreover, in recent years, new material has been discovered, including a large corpus from the 6th Dynasty tomb of Weni the Elder at Abydos and other elite mastabas from the Middle Cemetery at Abydos (Knoblauch Citation2010).Footnote4 New sources include late 6th Dynasty tombs at Abusir (Bárta Citation2009: 243–55, 261, 264, 270–71, pls 32, 33.5–6, 34.12, 38.1), Saqqara (Rzeuska Citation2008: 236, fig. 5 and references), Abu Rawash, Dashur and the Elephantine town (Forstner-Müller and Raue Citation2008). None are known thus far from contexts dating to the First Intermediate Period.

The cemetery corpus (, , , and Appendix 1)

George Reisner found many imported jars, fragmentary and intact, in and around tombs of the Egyptian elite during the 1907–42 Harvard University-Boston Museum of Fine Arts Expedition on the Giza plateau (Reisner and Smith Citation1955: 73–76). Twenty-nine of these vessels, spanning the early 4th to end of the 6th Dynasty, are held in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (MFA). This is the largest single corpus outside Egypt and has long been of scientific interest (Esse and Hopke Citation1986; Helck Citation1971: 25–37; Kantor Citation1992: 19–21; Sowada Citation2009: 54–74; 154–82 and references; Stager Citation1992: 38–41).

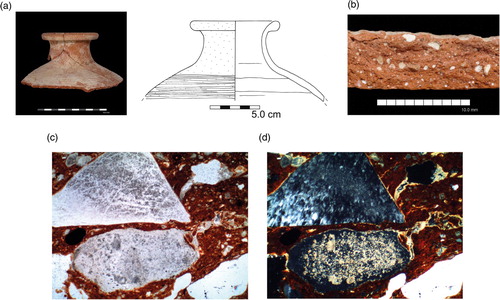

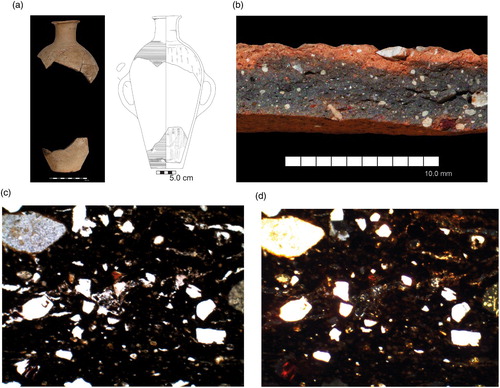

Figure 3 Imported pottery from Giza tombs: petrography Group 1 — Iron-rich, calcareous with chert, Fabric P200. Exemplar — Sample 1, Combed jar (MFA 13.5638), Tomb G 4240, early–mid 4th Dynasty.

a. MFA 13.5638 (Photo © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, photo and drawing K. Sowada).

b. Sherd fracture (photo K. Sowada).

c. Thin-section at plane-polarised light (PPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

d. Thin-section at cross-polarised light (XPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

Thin-sections show chert inclusion at top, decomposing limestone inclusion at bottom, quartz grain at lower right.

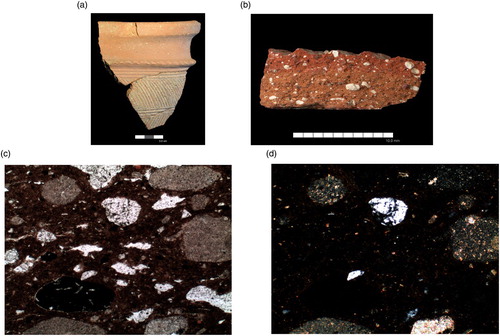

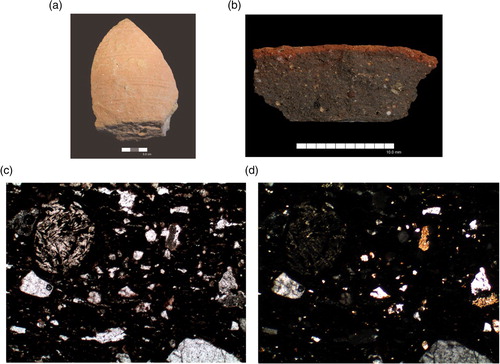

Figure 4 Imported pottery from the settlement at Heit el-Ghurab, Giza: petrography Group 1 — Iron-rich, calcareous with chert, Fabric P200. Exemplar — Sample 4, Combed krater rim (HeG Reg. 69608), square 4-E21, unit 21384, bakery, Gallery Complex, late 4th Dynasty.

a. HeG Reg. 69608 (photo A. Wodzińska).

b. Sherd fracture (photo J. Quinlan).

c. Thin-section at plane-polarized light (PPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

d. Thin-section at cross-polarized light (XPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

Thin-sections show decomposing limestone as light brown inclusions, quartz as white inclusion, shale fragment as black inclusion.

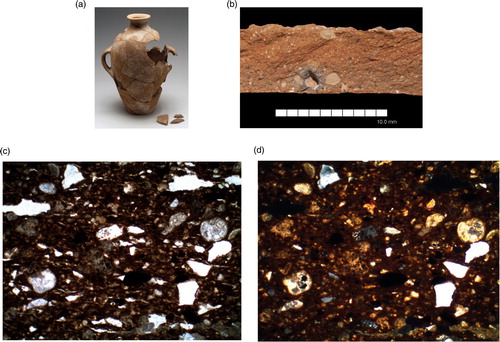

Figure 5 Imported pottery from Giza tombs: petrography Group 2 — iron-rich, less calcareous, with no chert, Fabric 201. Exemplar — Sample 2, Combed jar (MFA 13.5593), Tomb G 4340 A, 4th Dynasty.

a. MFA 13.5593 (Photo © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, photo and drawing K. Sowada).

b. Sherd fracture (photo K. Sowada).

c. Thin-section at plane-polarized light (PPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

d. Thin-section at cross-polarized light (XPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

Thin-sections show lack of sand-sized grains with a scatter of white silt-sized quartz grains.

Figure 6 Imported pottery from the settlement at Heit el-Ghurab, Giza: petrography Group 2 — iron-rich, less calcareous, with no chert, Fabric P201. Exemplar — Sample 5, Combed jar base (HeG Reg. 96251), 6-U24, unit 28608, Royal Administrative Building, late 4th Dynasty.

a. HeG Reg. 96251 (photo A. Wodzińska).

b. Sherd fracture (photo J. Quinlan).

c. Thin-section at plane-polarized light (PPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

d. Thin-section at cross-polarized light (XPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

Thin-sections show lack of sand-sized grains, large inclusion at upper left is a possible basalt fragment.

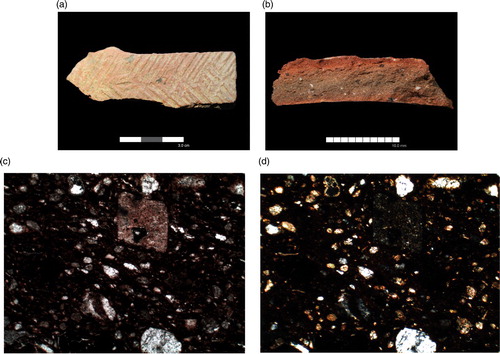

Figure 7 Imported pottery from Giza tombs: petrography Group 3 — calcareous, less iron-rich with foraminifera, Fabric P202. Exemplar — Sample 3, Combed jar (MFA 37.2729), Tomb G 5020 Annex A, early-mid 4th Dynasty.

a. MFA 37.2729 (photo © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, photo K. Sowada).

b. Sherd fracture (photo K. Sowada).

c. Thin-section at plane-polarized light (PPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

d. Thin-section at cross-polarized light (XPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

Thin-sections show lack of sand-sized grains, but silt-sized foraminifera middle at far right and lower left.

Figure 8 Imported pottery from the settlement at Heit el-Ghurab, Giza: petrography Group 3 — Calcareous, less iron-rich with foraminifera, Fabric P202. Exemplar — Sample 6, Combed jar body sherd (HeG Reg. 105925), square 4-E21, unit 22286, bakery, Gallery Complex, late 4th Dynasty.

a. HeG Reg. 105925 (photo A. Wodzińska).

b. Sherd fracture (photo J. Quinlan).

c. Thin-section at plane-polarized light (PPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

d. Thin-section at cross-polarized light (XPL), 100x magnification (micrograph M. Ownby).

Thin-sections show lack of sand-sized grains, brown chert inclusion at upper middle, and foraminifera at upper left.

Figure 9 Applied potmarks from Egypt and the central Levant.

a. MFA 37.1319 (Sample 11), Tomb G 7330, mid-late 4th Dynasty. Petrography Group 1, Fabric P200 (Photo © 2019 Museum of Fine Arts, Boston).

b. Detail of potmark on MFA 37.1319.

c. Applied ‘ram’s head’ potmark from Tell Fadous-Kfarabida (Genz Citation2014: fig. 12).

Two archaeometric studies have been conducted on the MFA material. In the mid-1980s, Doug Esse and Phil Hopke (Citation1986) published a hierarchical cluster analysis based on a Neutron Activation Analysis (NAA) study of 21 samples. One early to mid-4th Dynasty vessel, MFA 37.1319 (, Sample 11 in the present study) (a, App. 1, Fig. E), clustered closely with a sample from Byblos (Esse and Hopke Citation1986: 335, Gi EP07; annotated in Sowada Citation2009: 177).Footnote5 The primary elemental data, unpublished and presumed lost, was recently re-discovered in the MFA archives. The data is now of limited worth owing to the narrow set of rare earth elemental values in the 35-year-old results, and the greater precision that can be obtained from current NAA, XRF, and ICP-MS techniques.

Table 1 Summary of all samples included in the petrographic analysis

A second study using the PIXE-PIGME technique was conducted in the late 1990s (Grave, in Sowada Citation2009: app. II.1–II.8). Eight Giza samples, ranging in date from the early 4th to the early 5th Dynasty, were analyzed. These vessels were not included in the Hopke and Esse study. The results identified two main groups: one was silica rich, reflecting the presence of quartz sand and geode quartz, while the second had overall lower silica with more clay elements of iron and aluminium (Grave, in Sowada Citation2009: app. II.6–II.7). It is of interest that these groups clustered either side of samples taken from Byblos but belong to the same general group.

At the time, the MFA material was also visually examined, including section fractures under a 10x hand lens where possible. Of the Combed jars, several ware and fabric variations were observed, with a coarse and fine version of one dominant fabric type designated ‘Group IV’ (Sowada Citation2009: 169–72). This was the silica rich group noted above.

Over the years, at least 25 jars have been found associated with 4th Dynasty Giza tombs; likely the number is closer to 30+ given the uncertain dating of various contexts (Sowada Citation2009: 55–69; Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: 371, table 3). In 2017 and 2018, ten fragmentary Combed jars, nine of which are at the MFA, were sampled for thin-section petrography (Samples 1–3, 7–13). This number represents close to one third of known jars from the cemetery. Other MFA jars are intact or completely mended and thus not available for sampling. Six samples came from the same vessels used in the PIXE-PIGME study (Grave in Sowada Citation2009: 178, table 10) and four were also sampled by Esse and Hopke. Nine vessels date to the 4th Dynasty (Samples 1–3, 7–11, 13) with a further example dating to the early to mid 5th Dynasty (Sample 12). With the permission of project directors, a jar from the tomb of Khafre-ankh found during Russian excavations at Giza was included (Kormysheva Citation1999: 37, pl. IIb; Malykh Citation2011: 187, 192, 202, fig. 9) (Sample 13).Footnote6

The Heit el-Ghurab settlement corpus (, , and Appendix 2)

The settlement at Heit el-Ghurab lies 400 m south of the Sphinx. First examined in 1988, the excavated area now spreads over 250 × 400 m, exposing a large settlement that includes a planned community to house workers retained for building the royal monuments. Sealings of kings Khafre and Menkaure — builders of the second and third pyramids — along with coeval ceramic assemblages, place the date of the town from the mid to late 4th Dynasty, c. 2558–2503 BC (Lehner and Hawass Citation2017: 354–401).Footnote7

Twenty-six imported sherds from the settlement were examined petrographically (Samples 4–6, 14–36). It is likely that some sherds come from the same jar (especially Samples 4, 29–35) although such relationships could not be determined on physical examination. The imported material represents a tiny proportion of the over 300,000 diagnostic sherds of local origin found at the site. The group included two rim sherds, five bases, three handles and 16 body sherds. The material originated from three of the five town quarters identified at the site: the Gallery Complex and the so-called Royal Administrative Building; one sherd was found in the area called Standing Wall Island located to the south of the Western Town. None were found in the Eastern or Western Towns (Lehner Citation2007: esp. 43–46; Wodzińska and Ownby Citation2011: 291). Recently two more sherds were identified, in the context of debris left after excavations conducted by Karl Kromer (Witsell Citation2018).

Not all of these are associated with the elite housing and certainly represent re-use of the vessels. As a settlement established by royal prerogative, this close relationship likely resulted in imported jars being re-used for storage once emptied of their original contents. Examination under a hand lens in the field originally grouped the mostly Combed jar fragments into five fabric groups; all were dated to the late 4th Dynasty (Wodzińska and Ownby Citation2011: 287–90, 292). Preliminary study suggested that most were made with similar raw materials that were Levantine, possibly Lebanese, in character (Wodzińska and Ownby Citation2011: 293).

It is noteworthy that two combed vessel types were found at Heit el-Ghurab: a two-handled transport jar and large krater without handles. Seventeen sherds from two-handled jars (Samples 5–6, 14–25, 27–28, 36) were identified, along with nine sherds from two probable kraters (Samples 4, 26, 29–35). The latter is especially interesting since no other jars of this kind are known, so far, in Egypt (Wodzińska and Ownby Citation2011: 292–93). How many individual vessels the sherds represented is unknown, but given the size of the sherds and the number of diagnostics, less than five are likely.

Analytical method

Petrographic study of the 36 samples from the tombs and the settlement followed standard procedures and was conducted at 100x magnification using a LEICA DM 2500P polarizing microscope (see Bourriau and Nicholson Citation1992: 33–35; Ownby Citation2010; Whitbread Citation1995). For each section its colour in plane (PPL) and cross-polarised (XPL) light was noted; an estimate was made for the frequency of inclusions relative to clay matrix; and the sorting of the inclusions was specified. The minerals identified in the thin section were listed by those that represent the main inclusions, and those that are less common. For the inclusions, both their general shape and size range were noted. Finally, comments were made on the relationship between samples, technology of production and potential provenance. All of the provenance assignments are postulated, as the thin sections were not compared to ceramic raw materials or kiln material from known sites. Geological maps and some soil maps were consulted to arrive at the postulated provenance (Bartov Citation1994; Beydoun Citation1977; El Shazly Citation1977).

Fabric classification framework

In addition to petrographic groups, new fabric designations were developed to facilitate research by archaeologists and ceramicists working with imported material in Egypt. The Vienna System is the primary fabric classification scheme used for local and imported ceramics in Egypt (Bourriau and Arnold Citation1993: 162–86). However, the Vienna System does not extensively classify 3rd millennium BC material, focusing rather on ceramics of the 2nd and early 1st millennia BC. Even with further scientific refinement, the creation of new imported fabric groups within the Vienna System could not, for historical reasons, be accommodated for this project. Other localized schemes exist but these are often site or period specific.

Thus, rather than create a new, separate nomenclature, the 3rd millennium BC imported material was incorporated into the well-known Memphis/Saqqara scheme (Bourriau and Eriksson Citation2010: 17–32).Footnote8 The classification framework defines ‘fabric’ as ‘the raw material of pottery making as collected, processed and fired by the potter’ (Bourriau and Eriksson Citation2010: 17). The term stands in contrast to the oft-used phrase ‘ware’, a broader expression which defines ‘the recurrent association, in a group of ceramic artefacts, of a complex set of traits or attributes such as fabric, tempering materials, mode of manufacture, firing, surface treatment and decoration, morphological or functional features, or any combination of these’ (Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: 355). In the study of ceramics in Egypt, ‘ware’ is more simply defined as the combination of fabric, surface treatment and firing (Bourriau and Nicholson Citation1992: 30). For the purposes of this paper, characterizing Combed jar fabrics found in Egypt is a step in further defining the nuances of ‘Combed Ware’ in ceramic production during the Levantine Early Bronze Age (Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: 356).

Based on the petrography, macro description and chemical profile, new numbers in the Memphis/Saqqara ‘P’ fabric sequence from ‘P200’ onward were allocated to the material presented here.Footnote9 This nomenclature can be applied and further developed for all Old Kingdom imports, based on the defining parameters of inclusions, particle size, raw material and firing. The designators will be refined with chemical data in due course.

Petrographic results and fabric designations

The results of the petrographic analysis are presented in . The analysis revealed that the samples were produced with a related set of raw materials. Subtle differences divided the samples into three petrographic groups. Exemplars for each group are illustrated in – in this paper, with all additional material included in the Supplementary Appendices 1 and 2.

Group 1: iron-rich and calcareous with chert

This is by far the largest group, comprising 29 of 36 samples. They are very similar with an iron-rich and calcareous clay that could be rendzina; a soil developed in the Levant on limestone formations (Wieder and Adan-Bayewitz Citation2002). The main inclusions are medium- to coarse-sized quartz, micritic limestone and chert. These grains may represent sand temper, but it is difficult to know how the secondary clay deposits from the erosion of limestone, iron-rich outcrops and sandstone could form. Also present are fragments of chalcedony, geode quartz, iron-rich shale (argillaceous rock fragments [ARF]), clay pellets (Terra Rossa) and fine-sized dolomite (often with limonite). A few samples have rare inclusions of sparry limestone, phosphate, calcite, microfossils, glauconite and iddingsite. This may indicate a related but distinct source of raw materials for these samples, but the technological approach with possible sand temper is the same.

Description of Fabric P200

Structure/hardness is medium with sporadic sub-rounded and elongated pores, poorly sorted inclusions (2), and medium porosity. Firing colour in section is red (10R 5/8) to light reddish brown (5YR 6/4) to yellowish red (5YR 6/6) with no zones.

Inclusions: sporadic very coarse sub-angular to sub-rounded yellow to grey-white limestone <1.5 mm [5] visible to the naked eye; sporadic coarse angular light grey to white quartz or calcite 500 μm–1.0 mm [6]; sporadic coarse angular brown/grey chert granules <2.0 mm [5] visible to the naked eye; plentiful fine sub-rounded translucent red/light brown/light grey quartz sand <250 μm [8]; plentiful fine to very fine limestone 60–250 μm [9]–[8]; plentiful coarse Fe pieces <500 μm [7]; sporadic very fine sub-rounded grey-black stone 60–250 μm [9]–[8].

Group 2: iron-rich, less calcareous with no chert

Three samples were similar but with a more iron-rich likely rendzina clay and almost no chert fragments. The inclusions are fine to medium in size and are mostly calcite, microfossils, ARF, chalcedony, geode quartz, pyroxene, glauconite, sandstone (iron-matrix), iddingsite and possibly eroded volcanic rock fragments. The iron-rich nodules and ARF are common in the paste, while dolomite is absent. There is no indication that these inclusions represent sand temper and they are likely natural to the clay deposit. The overall paste appearance relates these samples to Group 1 suggesting a similar area of production.

Description of Fabric P201

Dense silty paste, structure/hardness is hard with sporadic fine rounded and larger elongated pores, sorting of inclusions is fair, porosity is medium to dense. Fired in two zones, dark grey (7.5YR 4/1) and red (2.5YR 6/8) close to exterior. Overall fewer inclusions and of smaller size.

Inclusions: sporadic coarse to medium textured, sub-rounded to rounded yellow-white limestone 250 μm–1.0 mm [7]–[6]; sporadic very coarse angular white/light grey quartz <2.0 mm visible to the naked eye [5]; sporadic coarse rounded iron ooliths <1.0 mm [6]; plentiful coarse to fine sub-angular Fe pieces <1.0 mm [6] visible to the naked eye; sporadic fine rounded light brown/grey quartz sand <250 μm [8]; medium textured sub-rounded black stone <500 μm [7].

Group 3: calcareous, less iron-rich with foraminifera

The three samples in Group 3 have a very fine clay, more calcareous and with notable foraminifera (a type of single shell organism). Again the clay could be rendzina, with natural inclusions, probably fired between 800°C and 850°C. Chert is less common but its presence, along with quartz, micritic limestone, sparry limestone, calcite, geode quartz, Terra Rossa, ARF and chalcedony, suggests a connection to the previous samples. These inclusions appear natural to the clay deposit. Most of the foraminifera are too indistinct to identify their species, but in Sample 12 some are suggested to be Globigerinidae sp., Globorotalia sp., and Orbulinoides sp. or Orbulina sp. that date to the Paleogene period, while a possible Lenticulina sp. dates to the Upper Cretaceous. Additional information on the species of foraminifera may help to date the clay deposits.

The vessel from the tomb of Khafre-ankh (Sample 13) has a more iron-rich clay with foraminifera; this is similar to Groups 2 and 3. Other inclusions were chert, geode quartz, chalcedony, calcite, micritic and sparry limestone, iron-rich clay pellets, volcanic rock fragments (weathered) and glauconite. These appeared natural to the clay and the overall characteristics suggest a similar source to the other samples from Giza.

Description of Fabric P202

Structure/hardness is medium, sorting is fair to good, porosity medium. Silty groundmass, well-prepared and well-mixed paste, evenly fired red (10R 5/6) in section with no zones.

Inclusions: plentiful very fine rounded quartz sand <60 μm [10]; very sporadic larger grey/white quartz <1.25 mm [5]; very sporadic coarse limestone <1.0 mm [6]; plentiful very fine limestone <125 μm [9]. Very fine grey-black stone <125 μm.

Discussion

The results provide important clarity on the raw materials utilized for the production of imported vessels from Giza. All the vessels were manufactured in a similar area, with the clay and inclusions indicative of the Lower Cretaceous formation, likely along the Lebanese coast (; Dubertret Citation1945; Citation1962; Badreshany et al. Citation2019: fig. 11). In this region, the Lower Cretaceous deposits are iron-rich and sandy, but Upper Cretaceous calcareous formations are present as well (Beydoun Citation1977: 322–35). In particular, the prevalent sub-rounded and medium-sized quartz may indicate a source near the Lower Cretaceous Chouf Sandstone Formation. The Upper Cretaceous Cenomanian-Turonian outcrops in Lebanon contain limestone, chert and geode quartz (Beydoun Citation1977: 322, 329, 332–33). The Paleogene foraminifera in Sample 12 may relate to the Chekka marls in this area, which is also suggested by the presence of chalcedony and geode quartz in the paste. The Lenticulina sp. is Upper Cretaceous in date. Although rendzina is common in the general region (Ilaiwi Citation1985), the Lower Cretaceous unit is located closest to the coast in the area between Beirut and Byblos.

Lower Cretaceous deposits are also present around the Sea of Galilee, but these often have rare, fine basalt fragments; these are not present in the Lower Cretaceous deposits along the Lebanese coast (Greenberg and Porat Citation1996: 16–17). No basalt fragments were seen in the thin sections, but chalcedony and geode quartz that are known for Lebanese Upper Cretaceous deposits were noted. The paste appearance of the main group of Giza Combed sherds, (Petrographic Group 1 — Fabric P200), is similar to fabrics identified at the northern coastal Lebanese sites of Tell Fadous-Kfarabida, Byblos and Koubba II, particularly Fabric 2A (Badreshany and Genz Citation2009; Badreshany et al. Citation2019). There may also be some connection to the Fabric 2 samples from Sidon as characterized by Griffiths (Citation2006). The petrographic analysis of EBA material from Tell Arqa (see Jean Citation2019) provides further comparative data, but none of the Giza samples examined in the current study are similar in fabric to those from Tell Arqa.

The petrography of the Giza imports aligns with other aspects of the vessels pointing to an origin in the Central Levant. Features include the combing style (Sowada Citation2018: fig. 4; Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: 367, figs 4–5) and various potmarks.Footnote10 The latter requires more detailed study but, by way of example, the parallel of an applied-clay ‘ram’s head’ on Sample 11, with near identical potmarks from Tell Fadous-Kfarabida, Byblos and Sidon, is undeniable () (Genz Citation2010: 108, fig. 15; 2014: 72, fig. 12; Mazzoni Citation1985; Sowada Citation2009: 59, fig. 8 [14], pl. 8; Sowada and Ownby Citationforthcoming). It is also striking that two kraters with a distinctive herring-bone pattern of combed decoration from Heit el-Ghurab find the best parallels at Tell Arqa (Thalmann Citation2000: 233–35), Fadous-Kfarabida (Badreshany et al. Citation2005: 74–75) and Sidon (Doumet-Serhal Citation2006: 254).Footnote11

The petrographic results reveal the continuation of earlier traditions of imported vessels from Lebanon, produced with Lower Cretaceous material, that goes back to Tomb U-j at Abydos (Hartung et al. Citation2015: 322–24). By the Early Dynastic Period, a range of different imported ceramic shapes, wares and fabrics appear in Egypt, concomitant with a variety of procurement networks across the southern and central Levant (Adams and Porat Citation1996; Amiran Citation1974; Genz Citation1993; Hartung et al. Citation2015; Helck Citation1971: 28–34; Hendrickx and Bavay Citation2002: 70–72; Iserlis et al. Citation2019; Sowada Citation2009: 39–48; Stager Citation1992: 37–39). The situation for the 2nd and 3rd Dynasties is less clear; evidence from Helwan suggests the maintenance of links with the Lebanese coast (Köhler and Ownby Citation2011: 38–39).Footnote12

Most of the material in this study dates to the great Pyramid Age of the 4th Dynasty. This era is coeval with the EB IIIB of the southern Levant (ARCANE ESL 5b) and the central Levant EB III (ARCANE mid–late ECL 4) (Lebeau and de Miroschedji Citation2014: ix; Sowada Citationforthcoming: fig. 3). By the 4th Dynasty, archaeological and fragmentary textual data reveal large-scale maritime imports of coniferous timbers and other products such as oils/resins, silver and lapis lazuli (Urk I: 236.4–5; Sowada Citation2009: 248–51; Strudwick Citation2005: 66 [trans.]). The ‘Byblos run’ to the central Levant is the geographical focus of early Old Kingdom maritime trade; the location of conifer forests and production centres for liquid commodities sought by the Egyptian state (Marcus Citation2002: 407–12; Stager Citation1992: 40–41).

Petrography of the Combed jars from early Old Kingdom Giza confirms this connection. While further work on pottery imports from Egypt is needed, all the material from 4th Dynasty Giza available for study derives from the central Levant. At this point no material found in Egypt originates south of the Jezreel Valley (contra Eliyahu-Behar et al. Citation2016; Esse and Hopke Citation1986: 334; Sowada Citation2009: 174–75). The petrography results point to a major shift in Egyptian commodity acquisition networks: the geographical scope of Early Dynastic exchange routes dissipates in favour of a focus by the Egyptian state on the region between Beirut to Tripoli. Moreover, the variety of shapes and wares so evident in the Early Dynastic period largely vanishes by this time. With a handful of early exceptions, the Combed jar becomes the main imported vessel type right up to the end of the 6th Dynasty (Marcus Citation2002: 409–11; Sowada Citation2009: 55–80, 155–58; Thalmann and Sowada Citation2014: 371, table 3). The Egyptian need for efficient transport mechanisms and procurement networks fuelled these changes, with Byblos as the likely key supply node. That said, the very incomplete nature of the Old Kingdom textual and archaeological record means that Egyptian regional and international engagement was likely more nuanced than these fragmentary data suggest (e.g. Adams Citation2017; Arnold et al. Citation2016; Redford Citation1986; Sowada Citation2009: 245–55; CitationForthcoming).

The biographical inscription of Iny reveals the longue durée of maritime relations with the central Levant. He served 6th Dynasty kings Pepy I, Merenre and Pepy II, a period coeval with the EB IV period in the central and southern Levant (ARCANE ESL6 and ECL6) (Sowada Citationforthcoming: fig. 3). Iny mentions multiple locations — including Byblos — visited as a leader of sea-going royal expeditions for the acquisition of lapis lazuli, silver, tin/lead, ‘Byblos ships’, men and women, and sefetj-oil (Marcolin and Espinel Citation2011: 574, 576, 581–82, 607). Imported pottery fabrics from the late Old Kingdom remain to be clarified; research currently underway on the large corpus from 6th Dynasty Abusir and Abydos (Knoblauch Citation2010) will provide a comparative dataset for foreign engagement at the end of the 3rd millennium BC. By this time, Egypt’s relationships focused on a handful of highly functional economic entities of the central and northern Levant — such as Byblos and Ebla — as the urban complexes of the southern Levant had long collapsed and other parts of the region faced further challenges (Sowada Citationforthcoming).Footnote13

Conclusion

Thin-section petrography of Combed jars establishes the central Levant as a source of Combed jars during the early Old Kingdom. The variations of paste recipes may point to different local production areas, but further research is required on this point. Notable is the consistent paste for the majority of vessels from the early Old Kingdom — 80% of the samples belonged to the same petrographic group (Group 1 — Fabric P200) — suggesting specialized production of the jars. What is emerging from the thin section and elemental data (see Grave in Sowada Citation2009: app II.1–8), however, is that while Byblos was likely the primary port of call for Egyptian expeditions, the wider region participated in this exchange activity, either directly or indirectly. Absent are ceramics from the southern Levant. This indicates a major shift in procurement networks for container-based products by the 4th Dynasty, from multiple locations in favour of a single, efficient maritime-based supply line directly to Byblos and environs. The question of Egypt’s impact over such a long period on the commodity producing communities of the central Levant, and the role of the southern Levant, remains to be fully understood.

Supplemental Material - Appendix 1: Samples from the Giza Cemetery

Download PDF (2 MB)Supplemental Material - Appendix 2: Samples from the Settlement at Heit el-Ghurab

Download PDF (3.9 MB)Acknowledgements

Research for this paper was funded by the Australian Research Council as part of the first author’s ARC Future Fellowship Project (FT170100288). Thank you to the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, for permission to study and sample the vessels in this paper. In particular, the Head of the Department of Ancient Art, Dr Rita Freed; Curator, Dr Denise Doxey; Research Associate, Dr Susan Allen; Head of Conservation, Dr Richard Newman; and 2018 MFA Intern Ms Inȇs Torres, provided every support for the on-site work. We are indebted to Dr Mark Lehner (Ancient Egypt Research Associates) for enabling inclusion of the Heit el-Ghurab material, and Dr Elena Kormysheva (Institute of Oriental Studies, Moscow) for permission to include the Khafre-ankh jar. Dr Sylvie Marchand, Dr Jane Smythe, Dr Anita Quiles and Nadine Mounir of the Institut français d'archéologie orientale in Cairo kindly facilitated access to the material and the IFAO laboratory. Special thanks are due to Dr Barbara Aston, Dr David Aston (Austrian Academy of Sciences) and Dr Carla Galorini (University of Birmingham, UK) for discussions about the fabric nomenclature and agreement to include the material in the Memphis/Saqqara scheme. Professor Peter der Manuelian (Harvard University) assisted with access to the Peabody Museum collection and with matters concerning the Giza Archive (www.gizapyramids.org). Thanks are also due to Prof. Hermann Genz for permission to reproduce the potmark in , Prof. Christiana Köhler for permission to use the image in b, Dr Uli Hartung for c, and to Dr Kamal Badreshany (University of Durham) and Dr Stephen Bourke (University of Sydney) for helpful comments during the production of this paper. Dr Melissa Kennedy, Dr Aaron De Souza, Dr Alice McClymont and Anthony Dakhoul provided additional support in preparing the text and illustrations. Mahmoud el-Shafai (Egyptian Ministry of Antiquities) kindly provided information about material from Heit el-Ghurab between 2013 and 2018.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data for this article can be accessed here https://doi.org/10.1080/00758914.2019.1664197.

Notes

1 A Combed jar from Cemetery B at Abydos, Dynasty 0 to early 1st Dynasty, was made of a silty shale Lower Cretaceous clay suggested to be from Lebanon (Hartung et al. Citation2015: 305–06, 319–22). Fragments from Naqada IIIA1 Tomb U-y were surface finds (Hartung et al. Citation2015; pers. com. 28/9/18) but had a similar petrographic origin.

2 As previously observed in Hartung et al. (Citation2015: 326), the absence of any published foreign vessels from the tomb of 2nd Dynasty King Nynetjer at Saqqara is curious (see Lacher-Raschdorff Citation2014: 87–89). Such vessels would be expected in a royal tomb.

3 A programme of residue analysis by Margaret Serpico and Richard Newman on Combed jars from Giza tombs in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, is currently underway.

4 The material is currently the subject of study by the authors and Christian Knoblauch (University of Swansea).

5 MFA 37.1319 will be comprehensively published in Sowada and Ownby (Citationforthcoming).

6 Now in the Institut français d'archéologie orientale (IFAO) in Cairo. Fragments of a second imported jar were also found during the excavations but not published (Kormysheva Citation1999: 37); sherds from the latter were not at the IFAO.

7 Dates used are those outlined in Shaw (Citation2003: 482–83). For further extensive information and publications of the Heit el-Ghurab settlement, see the website of Ancient Egypt Research Associates, URL aeraweb.org (accessed 13 August 2019).

8 In this respect we owe thanks to Dr Barbara Aston and Dr Carla Galorini for their opinion and helpful discussion.

9 The macro description was observed under a 10x hand lens on a fresh break oriented parallel to the rim, then checked under an optical microscope at low magnification. For the terminology and definition of size fractions, see Bourriau and Eriksson (Citation2010: 17–21).

10 The surface finish — that is, the presence of a slip or wash — as diagnostic of origin is not a settled matter. For a summary of opinions in the literature, see Sowada (Citation2009: 157) and the contribution by Eliyahu-Behar et al. (Citation2016). On the Combed jar found in Egypt with a cylinder seal impression, MFA 37.2724, see the recent contribution by Tumolo (Citation2018).

11 The vessels will be published shortly by A. Wodzińska.

12 The Helwan analysis was conducted before petrographic data was available on EBA material from Tell Arqa (see Jean Citation2019). The original suggestion of a source in that area may need to be revised, however, the attribution of the Helwan samples to areas in the central Levant remains accurate at this time.

13 For recent debate on these questions, see Höflmayer (Citation2017).

References

- Adams, B. and Friedman, R. F. 1992. Imports and influences in the Predynastic and Protodynastic settlement and funerary assemblages at Hierakonpolis. In, van den Brink, E. C. M. (ed.), The Nile Delta in Transition: 4th–3rd Millennium BC. Proceedings of the Seminar held in Cairo, 21–24 October 1990, at the Netherlands Institute of Archaeology and Arabic Studies: 317–38. Tel Aviv: E. C. M. van den Brink.

- Adams, B. and Porat, N. 1996. Imported pottery with potmarks from Abydos. In, Spencer, A. J. (ed.), Aspects of Early Egypt: 98–107. London: British Museum Press.

- Adams, M. J. 2017. The Egyptianized pottery cache from Megiddo’s Area J: a foundation deposit for Temple 4040. Tel Aviv 44(2): 141–64. DOI:10.1080/03344355.2017.1357272 doi: 10.1080/03344355.2017.1357272

- Amiran, R. 1974. The painted pottery style of the Early Bronze II period in Palestine. Levant 6: 65–73. doi: 10.1179/lev.1974.6.1.65

- Arnold, E. R., Hartmann, G., Greenfield, H. J., Shai, I., Babcock, L. E. and Maeir, A. M. 2016. Isotopic evidence for early trade in animals between Old Kingdom Egypt and Canaan. PLoS One 11(6): e0157650. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0157650 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0157650

- Badreshany, K. and Genz, H. 2009. Pottery production on the northern Lebanese coast during the Early Bronze Age II–III: the petrographic analysis of the ceramics from Tell Fadous-Kfarabida. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 355: 1–33. doi: 10.1086/BASOR25609334

- Badreshany, K., Genz, H. and Sader, H. 2005. An Early Bronze Age site on the Lebanese coast. Tell Fadous-Kfarabida 2004 and 2005: Final report. Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises 9: 5–115.

- Badreshany, K., Philip, G. and Kennedy, M. 2019. The development of integrated regional economies in the Early Bronze Age Levant: new evidence from ‘Combed-Ware’ jars. Levant. DOI:10.1080/00758914.2019.1641009

- Bárta, M. 2009. Abusir XIII: Abusir South 2. Tomb Complex of the Vizier Qar, his Sons Qar Junior and Senedjemib, and Iykai. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague.

- Bartov, Y. 1994. Geological Photomap of Israel and Adjacent Areas. 2nd ed. Jerusalem: The Geological Survey.

- Beydoun, Z. R. 1977. The Levantine countries: The geology of Syria and Lebanon (maritime regions). In, Nairn, A. E. M., Kanes, W. H. and Stehli, F. G. (eds), The Ocean Basins and Margins, Volume 4A: The Eastern Mediterranean: 319–53. New York and London: Plenum Press. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4684-3036-3_8

- Bourriau, J. D. and Arnold, D. 1993. An Introduction to Ancient Egyptian Pottery, Fasc. 1. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Bourriau, J. D. and Eriksson, K. 2010. The Survey of Memphis IV. Kom Rabia: The New Kingdom Pottery. Egypt Exploration Society, Excavation Memoir 93. London: Egypt Exploration Society.

- Bourriau, J. and Nicholson, P. 1992. Marl clay pottery fabrics of the New Kingdom from Memphis, Saqqara and Amarna. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 78: 29–91. DOI:10.2307/3822066 doi: 10.1177/030751339207800105

- Dubertret, L. 1945. Carte Géologique au 50.000e. Feuille de Beyrouth. Beirut: Ministére des Travaux Publics, République Libanaise.

- Dubertret, L. 1962. Carte Geologique Liban, Syrie et Bordure des Pays Voisins. Paris: Muséum d’histoire naturelle/Institut géographique national.

- Doumet-Serhal, C. 2006. The Early Bronze Age in Sidon: ‘College Site’ Excavations (1998–2000–2001). Bibliothèque Archéologique et Historique 178. Beirut: Institut Français du Proche-Orient.

- Eliyahu-Behar, A., Shai, I., Regev, L., Ben-Shlomo, D., Albaz, S., Maeir, A. M. and Greenfield, H. J. 2016. Early Bronze Age pottery covered with lime-plaster: technological observations. Tel Aviv 43(1): 27–42. DOI:10.1080/03344355.2016.1161373 doi: 10.1080/03344355.2016.1161373

- El Shazly, E. M. 1977. The geology of the Egyptian region. In, Nairn, A. E. M., Kanes, W. H. and Stehli, F. G. (eds), The Ocean Basins and Margins, Volume 4A: The Eastern Mediterranean: 379–444. New York and London: Plenum Press. DOI:10.1007/978-1-4684-3036-3_10

- Esse, D. and Hopke, P. 1986. Levantine trade in the Early Bronze Age: from pots to people. In, Olin, J. S. and Blackman, M. J. (eds), Proceedings of the 24th International Archaeometry Symposium: 327–39. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

- Forstner-Müller, I. and Raue, D. 2008. Elephantine and the Levant. In, Engel, E. M., Müller, V. and Hartung, U. (eds), Zeichen aus dem Sand: Streiflichter aus Ägyptens Geschichte zu Ehren von Günter Dreyer: 127–48. Menes 5. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Gardiner, A. H. 1969. The Admonitions of an Egyptian Sage from a Hieratic Papyrus in Leiden (Pap. Leiden 344 recto). Hildesheim: Georg Olms Verlag.

- Genz, H. 1993. Zur bemalten keramik der Frübronzezeit II–III in Palastina. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 109: 1–19.

- Genz, H. 2010. Recent excavations at Tell Fadous-Kfarabida. Near Eastern Archaeology 73(2–3): 102–13. DOI:10.1086/NEA25754040 doi: 10.1086/NEA25754040

- Genz, H. 2014. Excavations at Tell Fadous-Kfarabida 2004–2011: an Early and Middle Bronze Age site on the Lebanese coast. In, Höflmayer, F. and Eichmann, R. (eds), Egypt and the Southern Levant in the Early Bronze Age: 69–91. Orient-Archäologie 31. Rahden/Westf: Marie Leidorf.

- Greenberg, R. and Porat, N. 1996. A third millennium Levantine pottery production center: typology, petrography, and provenance of the Metallic Ware of northern Israel and adjacent regions. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 301: 5–24. DOI:10.2307/1357293 doi: 10.2307/1357293

- Griffiths, D. 2006. The petrography. In, C. Doument-Serhal (ed.), The Early Bronze Age in Sidon: ‘College Site’ Excavations (1998–2000–2001): 279–89. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 178. Beirut: Institut français du Proche-Orient.

- Hartung, U. 2001. Umm el-Qaab II. Importkeramik aus dem Friedhof U in Abydos (Umm el-Qaab) und die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 4. Jahrtausend v. Chr. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 92. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Hartung, U., Köhler, E. C., Müller, V. and Ownby, M. 2015. Imported pottery from Abydos: a new petrographic perspective. Ägypten und Levante 25: 293–333. DOI:10.1553/AEundL25s295

- Helck, W. 1971. Die Beziehungen Ägyptens zu Vorderasien im 3. und 2. Jahrtausend v. Chr. 2nd rev. ed. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen 5. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Hendrickx, S. and Bavay, L. 2002. The relative chronological position of Egyptian Predynastic and Early Dynastic tombs with objects imported from the Near East and the nature of interregional contacts. In, van Brink, E. C. M. and Levy, T. E. (eds), Egypt and the Levant. Interrelations from the 4th through the Early 3rd Millennium B.C.E.: 58–80. London/New York: Equinox.

- Höflmayer, F. 2017. The Late Third Millennium in the Ancient Near East: Chronology, C14, and Climate Change. Oriental Institute Seminars 11. Chicago: The Oriental Institute of the University of Chicago.

- Ilaiwi, M. 1985. Soil Map of Arab Countries. Soil Map of Syria and Lebanon. Damascus: The Arab Center for the Studies of Arid Zones and Dry Lands, Soil Sciences Division.

- Iserlis, M., Greenberg, R., Steiniger, D. 2019. Contact between First Dynasty Egypt and specific sites in the Levant: new evidence from ceramic analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science 24: 1023–40. DOI:10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.03.021 doi: 10.1016/j.jasrep.2019.03.021

- Jean, M. 2019. Pottery production at Tell Arqa (Lebanon) during the third millennium BC: preliminary results of petrographic analysis. Levant. DOI:10.1080/00758914.2018.1454239

- Kantor, H. J. 1992. The relative chronology of Egypt and its foreign correlations before the First Intermediate Period. In, Ehrich, R. (ed.), Chronologies in Old World Archaeology: 3–21. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Knoblauch, C. 2010. Preliminary report on the Early Bronze Age III pottery from contexts of the 6th Dynasty in the Abydos Middle Cemetery. Ägypten und Levante 20: 243–61. DOI:10.1553/AEundL20s243 doi: 10.1553/AEundL20s243

- Köhler, E. C. 1998. Tell el-Fara‘în — Buto. Band III: Die Keramik von der späten Naqada-Kultur bis zum frühen Alten Reich (Schichten III bis VI). Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archaeologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 94. Mainz: Philipp von Zabern.

- Köhler, E. C. and Ownby, M. F. 2011. Levantine imports and their imitations from Helwan. Ägypten und Levante 21: 31–46. DOI:10.1553/AEundL21s31 doi: 10.1553/AEundL21s31

- Kormysheva, E. 1999. Report on the activity of the Russian archaeological mission at Giza, Tomb G 7948, east field, during the season 1998. Annales du Service des Antiquités l’Égypte 74: 23–37.

- Lacher-Raschdorff, C. 2014. Das Grab des Königs Ninetjer in Saqqara: Architektonische Entwicklung Frühzeitlicher Grabanlagen in Ägypten. Archäologische Veröffentlichungen, Deutsches Archäologisches Institut, Abteilung Kairo 125. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz.

- Lebeau, M. and de Miroschedji, P. 2014. Foreword. In, Lebeau, M. (ed.), ARCANE (Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean), Interregional Volume II: Ceramics: ix–xi. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Lehner, M. 2007. Introduction. In, Lehner, M. and Wetterstrom W. (eds), Giza Reports, Volume 1: Project History, Survey, Ceramics, and the Main Street and Gallery III.4. Operations: 3–50. Giza Plateau Mapping Project, Giza Reports 1. Boston: Ancient Egypt Research Associates.

- Lehner, M. and Hawass, Z. 2017. Giza and the Pyramids. Thames and Hudson: London.

- Lucas, A. and Harris, J. R. 1989. Ancient Egyptian Materials and Industries. 4th ed. London: Histories and Mysteries of Man.

- Malykh, S. 2011. Pottery from the rock-cut tomb of Khafraankh in Giza. Cahiers de la céramique égyptienne 9: 185–213.

- Marcolin, M. and Espinel, A. D. 2011. The Sixth Dynasty biographic inscriptions of Iny: more pieces to the puzzle. In, Bárta, M., Coppens, F. and Krejcí, J. (eds), Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010, Volume 2: 570–615. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague.

- Marcus, E. 2002. Early seafaring and maritime activity in the southern Levant from prehistory through the third millennium BCE. In, van den Brink, E. C. M. and Levy, T. E. (eds), Egypt and the Levant. Interrelations from the 4th through the Early 3rd Millennium B.C.E.: 403–17. London/New York: Equinox.

- Mazzoni, S. 1985. Giza ed una produzione vascolare di Biblio. In, Bondi, S. F., Pernigotti, F. Serra and Vivian, A. (eds), Studi in Onore di Edda Bresciani. 317–35. Pisa: Giardini.

- Ownby, M. F. 2010. Canaanite jars from Memphis as evidence for trade and political relationships in the Middle Bronze Age. PhD. University of Cambridge.

- Petrie, W. M. F. 1902. Abydos, Part I. Egypt Exploration Fund Memoir 22. London: Egypt Exploration Fund.

- Redford, D. 1986. Egypt and Western Asia in the Old Kingdom. Journal of the American Research Centre in Egypt 23: 125–43. doi: 10.2307/40001094

- Reisner, G. A. and Smith, W. S. 1955. A History of the Giza Necropolis, Volume II. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Rzeuska, T. 2008. Late Old Kingdom pottery from West Saqqara necropolis and its value in dating. In, Vymazalová, H. and Bárta, M. (eds), Chronology and Archaeology in Ancient Egypt (the third millennium B.C.): 223–39. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague.

- Serpico, M. and White, R. 1996. A report on the analysis of contents of a cache of jars from the Tomb of Djer. In, Spencer, J. (ed.), Aspects of Early Egypt: 128–39. London: British Museum Press.

- Shaw, I. (ed.) 2003. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. University Press: Oxford.

- Sowada, K. 2009. Egypt in the Eastern Mediterranean During the Old Kingdom. An Archaeological Perspective. Orbis Biblicus et Orientalis 237. Fribourg/Göttingen: Academic Press/Vandenhoeck and Ruprecht.

- Sowada, K. 2018. Fake it till you make it: an imitation combed jar from Old Kingdom Giza, Bulletin de liaison de la céramique égyptienne 28: 117–22.

- Sowada, K. Forthcoming. Perspectives on Egypt in the southern Levant in light of the high Early Bronze Age chronology. In, Richard, S. (ed.), New Horizons in the Study of the Early Bronze III and Early Bronze IV in the Levant. Winona Lake, IN: Eisenbrauns.

- Sowada, K. and Ownby, M. Forthcoming. The combed jar as a trade ‘brand’ of the Early Bronze Age. BAAL Studies in Memory of Jean-Paul Thalmann.

- Stager, L. 1992. The periodization of Palestine from Neolithic through Early Bronze Age times. In, Ehrich, R. (ed.), Chronologies in Old World Archaeology: 22–41. 3rd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Strudwick, N. 2005. Texts from the Pyramid Age. Atlanta, GA: Society of Biblical Literature.

- Thalmann, J.-P. 2000. Tell Arqa. Bulletin d’archéologie et d’architecture libanaises 4: 5–74.

- Thalmann, J.-P. and Sowada, K. N. 2014. Levantine ‘Combed Ware’. In, Lebeau, M. (ed.), ARCANE (Associated Regional Chronologies for the Ancient Near East and the Eastern Mediterranean), Interregional Volume II: Ceramics: 355–78. Turnhout: Brepols.

- Tumolo, V. 2018. The Levantine seal-impressed jar from the Tomb G2370 at Giza revisited. In, Vacca, M., Pizzimenti, S. and Micale M. G. (eds), A Oriente del Delta Scritti sull’Egitto ed il Vicino Oriente antico in onore di Gabriella Scandone Matthiae: 611–28. Contributi e Materiali di Archeologia Orientale XVIII. Roma: Scienze e Lettere.

- Urk. I = Sethe, K. 1932. Urkunden des Alten Reichs, Abteilung I, Band I, Heft 1–4. 2nd rev. ed. Urkunden des Ägyptischen Altertums I. Leipzig: Hinrichs.

- Whitbread, I. K. 1995. Greek Transport Amphorae: A Petrological and Archaeological Study. Fitch Laboratory Occasional Paper 4. Athens: British School at Athens. DOI:10.1002/gea.3340110509

- Wieder, M. and Adan-Bayewitz, D. 2002. Soil parent materials and the pottery of Roman Galilee: a comparative study. Geoarchaeology 17: 393–415. DOI:10.1002/gea.10019 doi: 10.1002/gea.10019

- Witsell, A. 2018. Kromer 2018: basket by basket. Aeragram 19(1): 2–9.

- Wodzińska, A. and Ownby, M. 2011. Tentative remarks on Levantine combed ware from Heit el-Ghurab, Giza. In, Mynářová, J. (ed.), Egypt and the Near East: The Crossroads. Proceedings of an International Conference on the Relations of Egypt and the Near East in the Bronze Age. Prague, September 1–3, 2010: 285–96. Prague: Czech Institute of Egyptology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University in Prague.