Abstract

From the Upper Palaeolithic to the present, birds constituted a marginal motif in the extensive corpus of human artistic expression. Only one episode of human history stands out as an exception: the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A of the Near East (c. 9800–8700 BC). During this time, numerous bird representations occur at many sites across the region: Gilgal, Jerf el Ahmar, Mureybet, Nemrik 9, Tell ‘Abr 3, Körtik Tepe and Karahan Tepe. At least four categories of bird imagery are notable: bird figurines, bird statues, miniature bird depictions and monumental bird depictions. Reviewing the available evidence, we suggest that this is related to the momentous transitions from a mobile hunter-gatherer way of life to a sedentary, and ultimately agricultural, economy. As humans moved to permanent settlements, they relinquished much of their mobility and began developing a calendrical agricultural economy. Birds were relevant in both respects. First, their capacity for flight echoed the relinquished mobile mode of living. Second, massive seasonal bird migrations signified the need to keep farming tasks on schedule and closely correlated with the annual cycle.

Introduction

Birds have probably always attracted the attention of humans. First, they are a source of food, providing meat and eggs. Second, they have the capacity to fly, a human desire that has only recently become a reality with air-balloons and aeroplanes. In the Near East, in particular, the spectacular sight of nearly half a billion migrating birds travelling between Europe on the one hand, and the southern Levant and Africa on the other, was a regular biannual event.

In a recent paper Greet (Citation2020) discussed the representation of birds in Chalcolithic art, making a case for their prominent spiritual role during that time. While Greet lays out a number of convincing arguments for Chalcolithic avian representations as ritualistic depictions, we are unpersuaded about birds’ presumed meaningful part in Chalcolithic spiritual life. Greet mentions less than 20 bird depictions, which is negligible given the plethora of other animal portrayals, mostly horned quadrupeds, as he himself noted (Greet Citation2020: 63): zoomorphic vessels of sheep and cattle have been found in the temples of ‘En Gedi and Gilat (Garfinkel Citation1999: photos 151–2) and elsewhere (Epstein Citation1985; Garfinkel Citation1999: fig. 164:4); images of horns and horned animals have been found on ossuaries and other symbolically imbued artifacts in burial caves (van den Brink Citation2005: fig. 4.9; Milevski Citation2002: 138–40, fig 10:a–d; Perrot and Ladiray Citation1980: figs 103–6, 109:1–2, 119:5–10, 121:1, 141), on Golanian pottery vessels and basalt statues (Epstein Citation1998: 168–69, pls XXIII–XXIV), and on copper artifacts from the Cave of the Treasure and Giv‘at ha-Oranim (Bar-Adon Citation1980: items 7–8, 10, 17–19, 150; Scheftelowitz and Oren Citation2004: figs 5.1:16–17, 5.2:1). While bird imagery is a fascinating research topic, its spiritual significance during the Late Chalcolithic period seems to have been marginal at best.

By no means is this peculiar to the southern Levantine Late Chalcolithic. Rather, this seems to have been the rule in many periods. In Upper Palaeolithic Europe, bird depictions are a rare motif in an otherwise diverse and rich corpus of artistic expressions dominated by bison, cattle and horses (see Ortega et al. Citation2015: supplementary table II). In the Epi-Palaeolithic Near East, a bird was depicted on a stone plaque at ‘Ein Qashish South (Yaroshevich et al. Citation2016: fig. 10), but none were represented in the relatively rich artistic assemblage of the Natufian culture, c. 13,000–9800 BC, the first culture in the region to produce a considerable volume of artistic expression. Similarly, fowl were hardly depicted in Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and Pottery Neolithic art objects. At Çatalhöyük, only a few birds were recognized in an assemblage of 2154 zoomorphic figurines (Martin and Meskell Citation2012: 403); none were found in the rich artistic assemblage of Sha‘ar Hagolan (Garfinkel et al. Citation2010), and in the Halafian culture of northern Mesopotamia (c. 6200–5500 BC), birds were sometimes depicted on pottery vessels (Le Mière and Nieuwenhuyse Citation1996: fig. 3.39:6–7; Von Oppenheim Citation1943: pl. LVIII:10) but did not amount to a prominent motif.

In the Near East, one notable exception to this persistent rule is the earliest phase of the Neolithic period, the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA), c. 9800–8700 BC (Bar-Yosef and Belfer-Cohen Citation1989). The PPNA was first identified by Kenyon at Jericho and subsequently recognized at other sites throughout the region. Among other things, it features the earliest large-scale permanent villages, consisting of round dwellings and sizeable round public structures, at sites like Jericho, Mureybet, Jerf el Ahmar, Tell ‘Abr 3, Wadi Faynan 16 and Göbekli Tepe (Kenyon Citation1981; Mithen et al. Citation2011; Schmidt Citation2006; Citation2010; Citation2011; Stordeur et al. Citation2000; Yartah Citation2004). In this article, we emphasize and explain birds’ substantial but overlooked significance in this era’s worldview.

To date, bird imagery in PPNA assemblages has been mentioned and briefly discussed in site reports (Helmer et al. Citation2004; Hershman and Belfer-Cohen Citation2010: 193; Kozlowski Citation1989; Rollefson Citation2008; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 17; White et al. Citation2021: 1031), but little attention has been devoted to its importance within the zoomorphic iconography of this era. To facilitate this discussion, a four-category classification of bird depictions according to their medium and size is suggested:

Bird figurines — these are relatively small three-dimensional objects, 5–8 cm across, usually consisting of carved stone. They were found throughout the Near East.

Bird statues — these are relatively large, stone-carved items.

Miniature bird depictions — this category refers to two-dimensional representations of birds on small portable objects, often in combination with various geometric signs.

Monumental bird depictions — this category comprises bird portrayals on monumental pillars at Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe. These pillars are 4–5 m high and weigh 4–5 tons. They were placed in large circular buildings, at least 15 m in diameter, and decorated with rich zoomorphic engravings, including birds, foxes, cattle, boars, snakes and crabs. Birds constitute a large portion of the animals depicted on these pillars.

The data

In this section, we present the relevant data for each of the four categories mentioned above, 78 bird depictions in total (, ).

Table 1 The distribution of PPNA bird representations in the Near East, according to site and category (A. Bird Figurines; B. Bird Statues; C. Miniature Depictions of Birds; D. Monumental Depictions of Birds)

Bird figurines

Bird figurines have been reported from six sites:

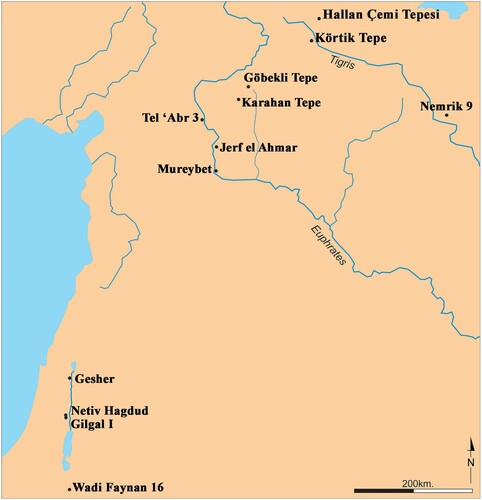

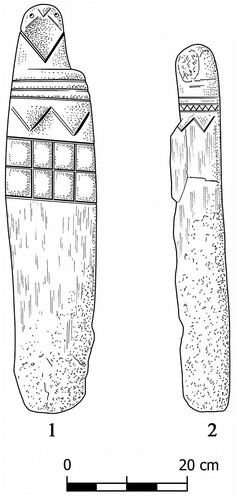

Gilgal I is located in the lower Jordan Valley, north of the Dead Sea (Bar-Yosef et al. Citation2010; Yizraeli Noy Citation1989). Excavations at the site uncovered round houses, impressive lithic and faunal assemblages, and a few dozen symbolic artifacts, including engraved plaques, anthropomorphic figurines and one bird figurine. This avian figurine was unearthed in House 11 with other anthropomorphic figurines, presumably constituting a cultic assemblage (Hershman and Belfer-Cohen Citation2010: 205–06, table 11.1; Yizraeli Noy Citation1989). It is c. 6 cm long and carved from soft limestone; it has a flat-topped head and no eyes. The beak, tail and legs are short and rounded. The wings look folded and have engraved lines symbolizing feathers (:1; Hershman and Belfer-Cohen, Citation2010: 193, fig. 11.7:1; Yizraeli Noy Citation1989: fig. 5:1).

Figure 2 Bird figurines from Gilgal (Hershman and Belfer-Cohen Citation2010: fig. 11.7:1), Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 17:2), Mureybet (Stordeur and Lebreton Citation2008: fig. 1), and Göbekli Tepe (Schmidt Citation2011: fig. 16).

Jerf el Ahmar is located on the east bank of the Euphrates River in northern Syria, east of Aleppo. It was excavated between 1995 and 2000 and has, since then, been submerged by the Tishrine dam. Over 60 buildings were uncovered, including five large, presumably communal, buildings. One schematic avian figurine was published (:2; Gourichon Citation2002: fig. 9; Helmer et al. Citation2004: fig. 4:C; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 17:2; Stordeur et al. Citation2000). It is 3 cm long and carved in stone. Small round depressions depict the eyes, and the beak is large and rounded. No wings or tail are portrayed.

Mureybet is located in the Euphrates Valley, in modern-day Syria. The site produced a few anthropomorphic figurines and one representing an owl (:3; Pichon Citation1985a; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 17:1; Stordeur and Lebreton Citation2008: 619–21, fig. 1). The figurine is oval, c. 12 × 6 × 3 cm, and made of limestone. It features big, round, owl-like eyes and an emphasized round beak. A deep horizontal line on the sides and back separates the head from the body, and two deep vertical grooves on the front, running down the chest, may represent wings. There are also shallow vertical grooves on the figurine’s body. No legs or tail are presented.

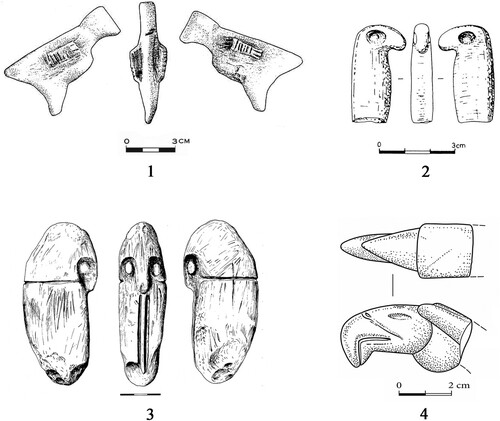

Nemrik 9 is located in the Tigris Valley, northern Iraq. It is a village site with round dwellings (Kozlowski Citation1989). An outstandingly rich assemblage of stone-carved avian figurines was unearthed here. Four constitute detailed naturalistic depictions of identifiable species, while eight more are schematic (; Kozlowski Citation1989: figs 8–9; Mazurowski Citation1997: pls XXXVII–LXVIII). The naturalistic depictions are long (up to 4 cm), cylindrical, have a conspicuous neck and round depressions indicating the eyes. Their gaze is directed upward or forward, and their prominent curved beak indicates birds of the Accipitridae family, which includes the eagle and the vulture. These birds are carnivorous; some are birds of prey, while others are scavengers. Notably, one of the figurines is of remarkable artistic quality, conveying a sense of viciousness and arousing fear (:1). Other figurines bear the same outline but are schematic and lack details; two are presented here (:3–4; Mazurowski Citation1997: pl. LXVIII).

Figure 3 Cylindrical bird figurines from Nemriq 9 (Kozlowski Citation1989; Mazurowski Citation1997).

Körtik Tepe is located in eastern Turkey, near Diyarbakır. This village site is characterized by rounded dwellings and an assemblage very rich in artistic expression. At this site a number of elongated cylindrical figurines were decorated with a bird head on their upper part (Õzkaya Citation2009: fig. 9; Özkaya et al. Citation2013: 67). There are at least six such objects, five of them are presented here (). The excavators interpreted this category of objects as pestles, however, from an iconograpic point of view they are similar to the birds reported from Nemriq 9 ().

Figure 4 Cylindrical bird figurines from Körtik Tepe (Õzkaya Citation2009: fig. 9; Özkaya et al. Citation2013: 67).

Göbekli Tepe is located in south-east Turkey, and is well-known for its monumental round buildings and tall T-shaped stone pillars (Dietrich et al. Citation2012; Schmidt Citation2006; Citation2010; Citation2011; Citation2012). One bird figurine engraved on red limestone was found here. It is 3 cm long and includes an elongated head, a bent beak and a portion of the upper body. It looks like a bird of prey and was identified by the expedition as a vulture (:4; Peters and Schmidt Citation2004: fig. 23; Schmidt Citation1997–98: fig. 10; Citation2011: fig. 16; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 17:6). Another similar bird figurine can be found online, on a commercial website (Slingstone Travel Citation2021). It is a photograph taken at the Şanliurfa Museum. Unfortunately, since no scientific publication of this item could be found, it has not been included in the figures or .

Significantly, these instances occur against the nearly complete absence of zoomorphic figurines in the PPNA. Around the Dead Sea, for example, numerous PPNA sites have been excavated — Jericho, Netiv Hagdud, Ain Darat, El Khiam, Dhra, Zahrat edh-Dhra 2 and Gilgal — but only one zoomorphic figurine was reported: the bird figurine from Gilgal I mentioned above. Similarly, no zoomorphic figurines were found in PPNA sites elsewhere in Israel (e.g., Nahal Oren, Hatula, Gesher). However, it is worth noting that Wadi Faynan 16, in Jordan, produced the head of a zoomorphic, non-avian figurine (Mithen et al. Citation2011: fig. 11).

This scarcity of PPNA zoomorphic imagery contrasts sharply with the rest of the Neolithic era. Over a thousand zoomorphic figurines were found throughout the Near East from the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) onwards, mostly depicting horned quadrupeds (e.g., Broman Morales Citation1983; Citation1990; Garfinkel Citation1995; Garfinkel et al. Citation2010; Martin and Meskell Citation2012; Rollefson Citation2008; Schmandt-Besserat Citation1997). Thus, although few in number, the bird figurines of the PPNA are outstanding in two critical respects. First, they were practically exclusive; other categories of zoomorphic figurines were nearly absent. Second, bird figurines hardly occur either before and after this period.

Bird statues

Bird statues have been reported at two sites so far:

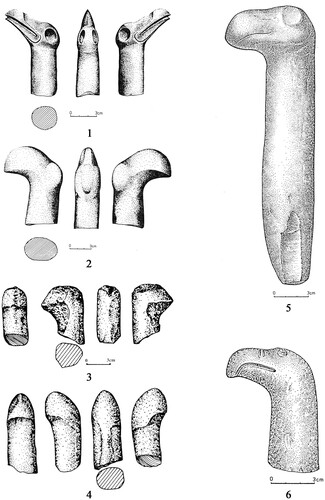

At Jerf el Ahmar two specimens were found in the same public building (Stordeur et al. Citation2000: fig. 11). They were described together as ‘ … two pillars in limestone which were part of what is interpreted as a collective building. Although they were damaged, certain characters strongly suggest that these stones were carved into the form of a large Accipitrid’ (Gourichon Citation2002: 149). The more impressive of the two stands nearly 1 m tall. It depicts a large, forward-gazing bird with three parallel horizontal lines under the head, two large triangles below them and a geometric pattern on the chest (:1; Gourichon Citation2002: fig. 10; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: figs 5, 17:4; Stordeur et al. Citation2000: fig. 11, right). The other statue is similar to the first (:2; Stordeur et al. Citation2000: fig. 11, left). It is slightly narrower, also representing a large, forward-looking bird. Two parallel horizontal lines were engraved under the head, and below them, another horizontal band with a complex pattern crowned two large triangles; the rest of the figure was eroded away. The triangles depicted on both statues may represent feathers or schematically folded wings. Alternatively, they may represent breasts and thus, as suggested for later Neolithic figurines, may depict hybrid female-bird figures (Orrelle and Horwitz Citation2021). In the absence of any explicit human attributes, we consider the first interpretation preferable.

Figure 5 Bird statues from Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur et al. Citation2000: fig. 11).

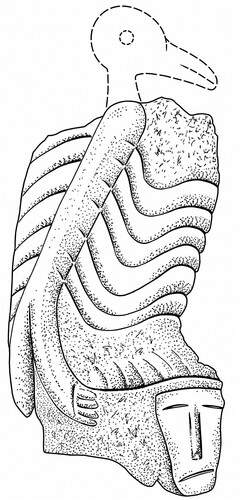

From Göbekli Tepe a fragment of a sculpture depicting a large bird, with a more than life-size human head in its talons, has been published (; Dietrich et al. Citation2014: 15, fig. 9; Fagan Citation2017: fig. 3). The top of the bird’s head is missing, as is the lower part of the human figure. The preserved part is c. 25 cm tall and includes the body, feathers and the leg of the bird. At Nevali Çori a statue with the same motif was found; a bird of prey standing on top of two human heads (Köksal-Schmidt and Schmidt Citation2010: fig. 2).

Figure 6 A bird statue from Göbekli Tepe (Dietrich et al. Citation2014: fig. 9).

Notably, these are the only instance of large PPNA bird statues. At Göbekli Tepe, sizeable zoomorphic statues are primarily of predators (Schmidt Citation2010: fig. 25; Citation2011: figs 19, 24) but no horned quadruped.

Miniature bird depictions

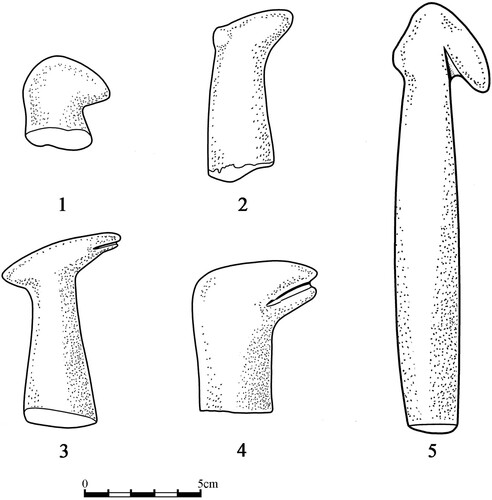

Small portable objects depicting birds were found at four sites.

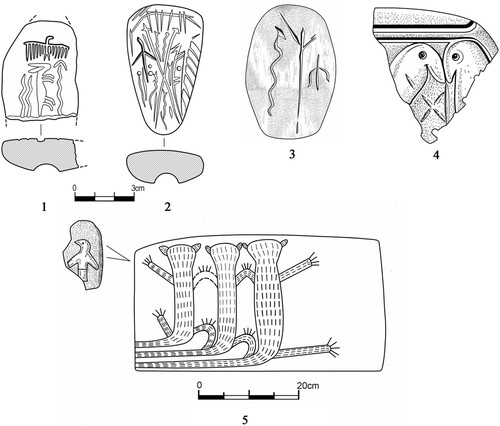

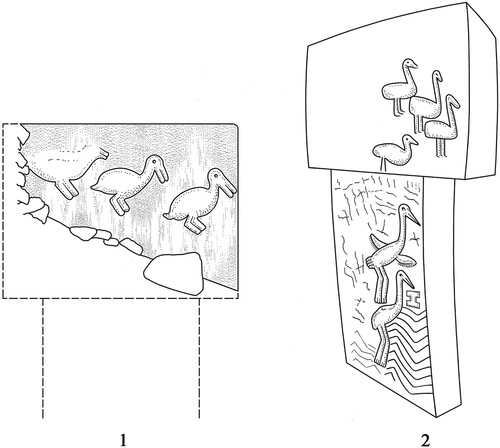

Jerf el Ahmar produced a number of small grooved stone plaques depicting various animals or geometric motifs. One such plaque presents a bird, a fox and a few snakes (:1; Gourichon Citation2002: fig. 8; Helmer et al. Citation2004: fig. 6:A; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 16:3; Stordeur et al. Citation1997a). The bird looks like a bird of prey, including a conspicuous beak, extended wings with six feather-lines each, and a split tail. On another small stone object, of the type commonly called ‘shaft straightener’, a schematic bird is depicted together with a fox, snakes and various geometric motifs (:2; Helmer et al. Citation2004: fig. 6:B; Stordeur et al. Citation1997a: fig. 2:b). The bird is presented in flight position, with extended wings. A similar bird depiction, on a small plaque, is known from Göbekli Tepe (:3).

Figure 7 Birds depicted on small plaques from Jerf el Ahmar (Stordeur et al. Citation1997a: fig. 2:a–b; Stordeur and Abbès Citation2002: fig. 16:3), Göbekli Tepe (Schmidt Citation2011: fig. 12) and Tell ‘Abr 3 (Yartah Citation2004: fig. 12).

At Göbekli Tepe, one small round stone plaque was engraved with three signs. A line crossing the middle of the plaque divides the surface in two. A snake is portrayed on the left side and a bird on the right. Although schematic, the bird is clearly in flight with extended wings (:3; Costello Citation2011: 252, fig. 3; Dietrich et al. Citation2012: fig. 9:6; Schmidt Citation2011: fig. 12).

A small fragment, of an engraved stone plaque from the site, was discovered in the deep sounding in trench K10-13. It was interpreted as presenting two snake heads and below them a netlike depiction of interwoven snake bodies, very similar to the imagery on Pillar 1 from Enclosure A (:4; Dietrich et al. Citation2014: 16, fig. 12). This identification can be questioned. First, the figures are not identical to each other; when a group of snakes was depicted, the creatures were identical to each other. Second, two deep holes in each head seem to indicate the eyes. However, the holes are not identical and only one hole in each head seems to be the result of intentional drilling. Third, the lower part of the left snake was understood as a net pattern, known on Pillar 1 of the site (Dietrich et al. Citation2014: 16). Why was a net pattern not depicted on the other snake? Birds with a net pattern are known from Pillar 12 in Enclosure B (:2). We interpret this image as two birds facing each other.

Figure 9 Birds depicted on monumental Pillars A2, B12, and D18, Göbekli Tepe (Schmidt Citation2011: figs 14, 8, 34; Citation2013: fig. 2).

Tell ‘Abr 3 is located in the Euphrates Valley, Syria. The excavations uncovered a large round public structure (Yartah Citation2004; Citation2005) and a few engraved objects bearing geometric and zoomorphic motifs, including at least six leopards (Yartah Citation2004: figs 11–13). One specimen comprised a plaque decorated with three leopards on one side and a bird on the other (:5; Yartah Citation2004: fig. 12).

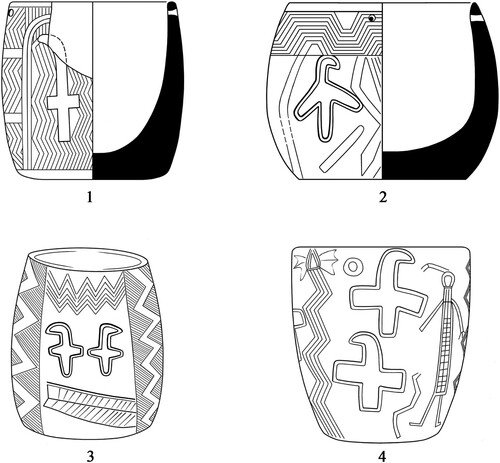

Körtik Tepe produced a large number of stone containers that were decorated with incised patterns, including human figures, animals and geometric motifs (Özkaya et al. Citation2013). The animals depicted include horned animals (Özkaya et al. Citation2013: 6), snakes (Özkaya et al. Citation2013: 40) and birds (Özkaya et al. Citation2013: 54–56, 61). There are at least four vessels decorated with seven birds (): this number includes only the birds visible on the photographed side of the rounded vessel, additional birds probably appeared on the opposite side of some of the vessels. As far as we are aware, this is the only site with decorative birds depicted on stone containers.

Figure 8 Birds depicted on stone vessels from Körtik Tepe (Özkaya et al. Citation2013: 54–56, 61).

The engraving on grooved stones, or plaques — depicting various animal and abstract signs (Mithen et al. Citation2011: fig. 8; Stordeur et al. Citation1997a: fig. 2; Citation1997b) — requires research beyond the scope of the present paper.

Monumental bird depictions

Only two sites feature monumental pillars with avian motifs: Göbekli Tepe and Karahan Tepe. For Karahan Tepe, only one brief mention is presently available — ‘one bird-shaped relief’ — and no accompanying image (Çelik Citation2011: 243; for further information on the site, see Karul Citation2021). Göbekli Tepe is better documented, albeit unsystematically and preliminarily (Schmidt Citation2006; Citation2010; Citation2011). Only recently was a good summary published (Busacca Citation2017: tables 2–4). The stone pillars at the site are components of the monumental architecture, comprising several round enclosures, 10–20 m in diameter. The typical pillar is 4–5 m high and T-shaped. Various animals, including birds, were depicted on both the pillar’s vertical and horizontal parts (Dietrich et al. Citation2012; Schmidt Citation2006; Citation2010; Citation2011; Citation2012). Below, is presented a brief review of the pillars with bird depictions.

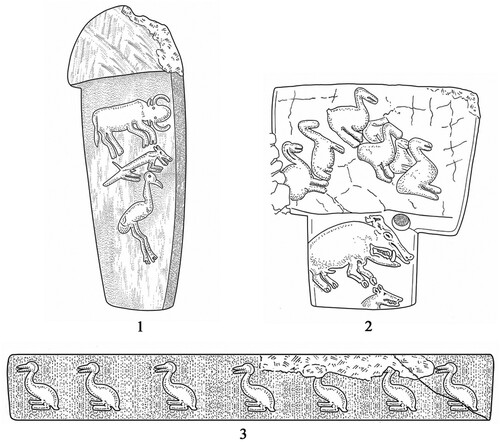

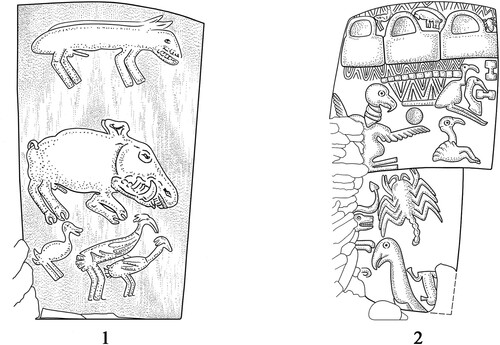

Pillar 2 in Enclosure A (:1; Schmidt Citation2011: fig. 14) presents three animals, one below the other: a bull; a fox; and a crane. This waterfowl is depicted standing and in profile; among the details portrayed are an eye, a beak, a long neck and two long legs.

Pillar 12 in Enclosure B (:2; Schmidt Citation2011: fig. 8) features seven birds on the pillar’s wide horizontal top. Five birds are immediately noticeable, but look closely and two small birds can be seen, engraved between the bigger birds on the right side of the pillar. All seven birds are schematically portrayed, including rounded beaks and two rounded legs, but no eyes or other fine details. Crossed lines behind the birds seem to indicate a net. When first published, this depiction was described as ‘animals in landscape’ (Peters and Schmidt Citation2004: 195, caption to fig. 13). Only later was the scene identified as ‘a number of birds (probably ducks) and a net’ (Schmidt Citation2011: 64, fig. 8).

Pillar 18 in Enclosure D (:3; Schmidt Citation2013: fig. 2) has, on its base, seven ducks in a row. The birds face the left; their distinguishing attributes include a beak, a relatively long neck and legs.

Pillar 23 in Enclosure C (:1; Busacca Citation2017: fig. 2:C) depicts three schematic birds on its wide horizontal top. They have relatively large beaks and short legs, apparently ducks.

Figure 10 Birds depicted on monumental Pillars C23 and D33, Göbekli Tepe (Busacca Citation2017: fig. 2:C; Schmidt Citation2003: fig. 10).

Pillar 33 in Enclosure D (:2; Schmidt Citation2003: fig. 10) features six cranes: four on the wide horizontal top and two on the vertical lower part. All are depicted similarly: the head and beak combined, a long neck and long legs. The two lower birds seem a little taller and their legs are slightly bent.

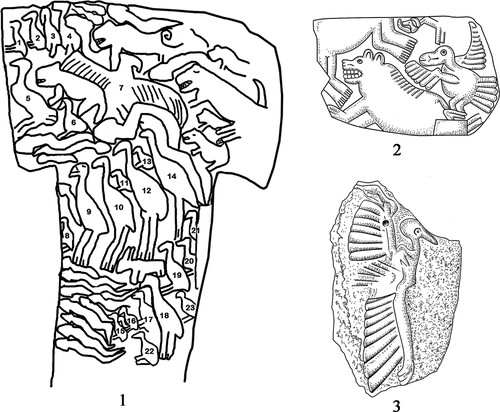

Pillar 38 in Enclosure D (:1; Schmidt Citation2003: fig. 8) presents three birds near the base. They face the same direction and are positioned below a fox(?) and a boar. The birds are probably cranes: they have long necks and long legs. Two of the birds have bent legs.

Figure 11 Birds depicted on monumental Pillars D38 and D43, Göbekli Tepe (Schmidt Citation2003: fig. 8; Citation2011: fig. 29).

Pillar 43 in Enclosure D (:2; Fagan Citation2017: fig. 2; Schmidt Citation2011: fig. 29) displays four birds in unique styles, unparalleled elsewhere at the site. Three birds are depicted on the pillar’s wide horizontal top: one on the left and two on the right. On the left, a large dominant bird is depicted facing the viewer. It has a round head, two dots for the eyes, a bent beak, a line crossing the neck and a triangle at the neck’s base. Its wings are spread out, with a series of lines depicting feathers; the legs are bent sharply to the right, as if in a sitting position. The two birds on the right side have long necks and bent legs. The legs of the upper bird are particularly long. The fourth bird is located at the bottom of the pillar and was only partially unearthed. The exposed part includes a large head, an eye, a pointed beak and a long neck. Interestingly, while all the other birds face right, this bird faces left.

Pillar 56 in Enclosure H (:1; Fagan Citation2017: fig. 8; Schmidt Citation2013: fig. 7) presents an exceptionally dense scene with 55 animals, mainly birds and snakes. Altogether 23 birds are depicted. Most of them are cranes or ducks, schematically portrayed and facing left. One large bird in the centre was depicted with extended wings and feathers, facing right.

Figure 12 Birds depicted on monumental Pillar H56, pillar fragment from enclosure D and pillar fragment from Trench L9-65, Göbekli Tepe (Dietrich et al. Citation2014: fig. 10; Schmidt Citation2010: fig. 11; Citation2013: fig. 7).

A pillar fragment in Enclosure D (:2; Schmidt Citation2010: fig. 11) carries, on its left side, a depiction of a large left-facing beast, probably a bear. Two birds are located to its right, one above the other. One is large and exceptionally rich in detail: it faces left, has a rounded head, an eye, a bent beak, a neck, and extended wings with several lines crossing each, depicting feathers. A tail is also depicted, with several lines that emphasize the feathers, and two small legs. The head of another bird is depicted on top.

A pillar fragment from Trench L9-65 (:3). This fragment is not associated with any specific construction. It was unearthed in the 2012 excavation season and was described as another depiction of a bird, this time a vulture in low relief. The bird, its wings outstretched, is shown in surprising detail (Dietrich et al. Citation2014: 15, fig. 10).

Altogether, 57 monumentally depicted birds were recorded at Göbekli Tepe, usually three to six specimens per pillar. Most appear to be cranes and ducks; some may be vultures as they are depicted with extended wings (:1, :2, :2–3). They occur alongside various other species: fox, boar, wild ass, gazelle, snakes, ram, reptiles, insects, spiders, scorpions and felids (Busacca Citation2017: tables 2–4). Unfortunately, precise quantitative data is still wanting — not all pillars have been published, and zoological identification is sometimes indeterminate — meaning that a rigorous estimation of the place of birds in this remarkable scene is hard to ascertain. Nevertheless, it is evident from the above that they fulfill a significant ritualistic role at Göbekli Tepe.

Birds in faunal assemblages

Birds were exploited for food by Epi-Palaeolithic and Neolithic communities, the PPNA included (Gourichon Citation2004: 127–11; Tchernov Citation1993; White et al. Citation2021; Yeomans and Richter Citation2018). Accordingly, it could be argued that the depiction of birds was a function of their economic importance as a food source. In order to consider this hypothesis, we will review the faunal reports available for PPNA sites, regardless of whether or not they produced depictions of birds. They are discussed in geographical order from north to south.

Hallan Çemi Tepesi is located in the Zagros mountains in Turkey. Birds of all sizes were noted, small, medium, large and very large (Starkovich and Stiner Citation2009: table 2).

Zawi Çemi is located in the Zagros mountains in Iraq (Solecki Citation1981). It yielded an interesting faunal sample, including evidence of feasting. It consisted of a large concentration of animal bones, including 15–20 sheep and goat skulls, and wing bones of several large raptors. The bird remains were interpreted as ritual paraphernalia (Solecki Citation1981: 53–54; Solecki and McGovern Citation1980; Zeder and Spitzer Citation2016).

Körtik Tepe fauna was presented in a detailed article. Of 1269 identified bones 145 were of birds. The calculation of the biomass indicate that the birds constitute 1.4% of the total animals (Arbuckle and Özkaya Citation2006: 126, table 2).

Göbekli Tepe. A report on the bird bones uncovered in the 1996–2003 seasons presents 605 specimens, 290 of which were classified into 38 taxa (Peters et al. Citation2005: table 1). The common crane, frequently depicted on the monumental pillars, was also common in the bone assemblage, and cut marks indicate they were consumed. For comparative purposes, a report on the 1996–2001 seasons at the site mentions 38,704 mammal bones (Peters and Schmidt Citation2004: table 1). While existing publications report different seasons and, therefore, are not fully comparable, it seems that birds constitute only c. 1%–2% of the fauna at Göbekli Tepe, a surprisingly low percentage considering their prominence in the site’s iconography.

Jerf el Ahmar. An article dedicated to the bird remains at Jerf el Ahmar reports an assemblage of 1554 items, attributed to nearly 50 different taxa (Gourichon Citation2002; Citation2004: 295–306). Geese, cranes, black francolin and diurnal birds of prey are the most frequent. Among the birds of prey, a griffon vulture was noted; according to the report, it was not valued for its meat but for other resources, such as skin, feathers, claws and raw bone material, perhaps underlying a ritualistic function. However, without data on other fauna present at the site, the relative significance of birds remains indeterminate.

Mureybet. Altogether, 78 bird bones were recovered from PPNA Mureyebet (Phases IB–III; Gourichon Citation2004: 251–76; Pichon Citation1985b: table 1). Presently, little more can be said.

Gesher, in the central Jordan Valley, produced a small assemblage of animal bones (n = 141), including three unidentified bird bones (Horwitz and Garfinkel Citation1991; table 1).

Netiv Hagdud is a village site in the lower Jordan Valley, near Gilgal. The fauna has been published in detail (Tchernov Citation1994: 13–40), and birds are estimated to have constituted approximately one-third of the meat consumed at the site (Tchernov Citation1994: fig. 26). They comprise a wide spectrum of species and sizes, reflecting a mosaic of habitats around the site.

Gilgal I and II produced a faunal assemblage of 1329 identified bones, of which 737 are birds (55%; Horwitz et al. Citation2010: table 18.1), mostly waterfowl. While their absolute number is outstanding, it is notable that in terms of biomass, their contribution is lower than that of the mammals.

Wadi Faynan 16. The extensive excavations at this village site in south Jordan produced an enormous assemblage of 17,700 bird bones, of which 7808 were identified to family level or further. Altogether, 63 bird taxa of 18 families were identified, representing a mix of resident and migratory birds (White et al. Citation2021). However, Accipitridae constitute 89.3% of the assemblage, underscoring the prominence of hooked-beak birds like eagles and vultures. Notwithstanding, other components of the faunal assemblage are yet to be published, rendering the evaluation of birds’ place in the diet indeterminate. Considering the impressive amount of bird bones at the site, the absence of bird imagery is surprising.

The faunal reports discussed above indicate that birds are well-represented in PPNA faunal assemblages. Unfortunately, the rest of the fauna did not always receive the same attention, which precludes an understanding of the position occupied by fowl in the PPNA diet and animal-based economy. In any case, birds are unlikely to have constituted a substantial part of the diet; compared to mammals like gazelle and boar, the amount of meat they provide is meager. This observation supports the notion that birds were of greater symbolic than economic value.

Discussion

From the Upper Palaeolithic and onward, birds constituted a peripheral motif in Europe and the Near East. Only in the PPNA of the Near East (c. 9800–8700 BC) did birds acquire relative symbolic prominence and were represented frequently enough to justify a four-fold classification: bird figurines; bird statues; miniature bird depictions; and monumental bird depictions. These have been uncovered at sites spanning the Levant and Mesopotamia: Göbekli Tepe (61 birds), Körtik Tepe (13 birds), Nemrik 9 (12 birds), Jerf el Ahmar (5 birds), Gilgal I (1 bird), Mureybet (1 bird), Tell ‘Abr 3 (1 bird) and Karahan Tepe (1 bird). This is in sharp contrast to the absence of quadrat zoomorphic figurines at these sites, or to the thousands of quadrat zoomorphic figurines which were unearthed at countless sites of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B and the Pottery Neolithic periods.

No animal was depicted so widely in the PPNA as the bird: it was the most widely distributed, diversified and numerous. On the monumental pillars of Göbekli Tepe, birds are depicted on 10 decorated pillars or pillar fragments, and are the most frequently occurring animal after the 71 depictions of snakes. Notably, snakes’ popularity at Göbekli Tepe is exceptional — they are hardly depicted at other PPNA sites. We are aware of only one other PPNA site with depictions of snakes; the site of Jerf el Ahmar, where 12 snakes can be counted on four small stone plaques (Stordeur et al. Citation1997a: fig. 2:a–d: 3, 5, 1 and 3 snakes respectably). When considering the PPNA in its entirety, bird depictions are more widespread than snakes.

Schematic bird representations tend to impede the precise taxonomic classification of many portrayals. Nevertheless, the more naturalistic representations seem to indicate cranes, ducks, an owl and vultures. As indicated by the archeozoological reports, fowl is unlikely to have constituted a significant part of the diet. Nevertheless, the avian component in the faunal assemblages seems to coincide with the depicted taxa.

Thus, as various scholars have suggested, the representation of birds mainly reflects symbolic and ritualistic concerns (Martin et al. Citation2013; Mithen Citation2022). In a similar way, crane remains from the later Neolithic site of Çatalhöyük were associated with dance accessories (Russell Citation2019; Russell and McGowan Citation2003). The prominence of large birds (vultures and cranes) might be attributed to their striking visual impact, which probably also fed into their selection for ritual activities (Solecki Citation1981: 53–54; Solecki and McGovern Citation1980; Zeder and Spitzer Citation2016). The contexts within which bird depictions have been found also suggests their participation in ritual activities. Thus, the bird figurine from Gilgal I was found together with other figurines in one building, the engraved plaque from Tell ‘Abr 3 and the two bird statues from Jerf el Ahmar were recovered from communal buildings, and the numerous bird depictions at Göbekli Tepe are all derived from monumental cult buildings.

Having established their cultic significance, we may now ask, ‘why birds’? As summarized by Russell (Citation2019: 377), ‘Birds have attracted human attention around the world because they combine human traits, such as bipedalism, interactivity, song, and dance, with capabilities out of our reach, notably flight. Thanks to this combination, and particularly their ability to ascend into the heavens, people have often seen birds as embodied spirits or messengers from the gods or the otherworld. Bird behaviour, then, takes on special meaning as humans try to understand and communicate with spirit birds’.

Another aspect that needs clarification is ‘why now’? As noted, from the Upper Palaeolithic to the present, birds were a marginal motif in human artistic expressions. What, then, happened in the PPNA of the Near East that suddenly directed human symbolic attention to birds? We suggest two reasons.

Firstly, the conspicuous migratory behaviour of many birds underscored the mobile way of living that was recently abandoned for a more residential existence. The transition from seasonal camps, with temporal huts built from perishable materials, to permanent mud and stone dwellings with attached fields for cultivation was dramatic and possibly traumatic. People stopped moving between seasonal sites, and the mass migration of birds set this development in sharp relief. In this capacity, birds symbolized mobility and helped keep the memory, longing and desire for a way of life that had vanished and passed away.

Secondly, birds are a seasonal marker, repeatedly arriving at the same time of the year (Schmidt Citation2012: 182–84). As the people of the PPNA were transitioning to agriculture, they must have acquired a new sensitivity to seasonal matters. To successfully practice agriculture, one must sow the land and harvest the crops at the right time. This was the context in which calendrical rituals were introduced, facilitating the co-ordination of economic activities (Garfinkel Citation2003; Citation2018). The seasonal mass migration of birds must have fed into this development.

Conclusions

As indicated in the introduction, human interest in birds may be attributable to three major features: their role as a means of sustenance; their capacity to fly; and their function as a seasonal marker. As humans abandoned the nomadic way of life and moved to permanent settlements, they relinquished the mobile element in their lives. At this stage, a calendrical economy was being established, and the correlation of agricultural activities with the annual cycle was being consolidated. Thus, birds’ seasonal migrations coincide with the need to keep a tight schedule of farming tasks. These two aspects are probably why birds became a major motif in the symbolic expression of the earliest Neolithic communities of the Near East.

References

- Arbuckle, B. S. and Özkaya, V. 2006. Animal exploitation at Körtik Tepe: an early Aceramic Neolithic site in southeastern Turkey. Paléorient 32(2): 113–36.

- Bar-Adon, P. 1980. The Cave of the Treasure: The Finds from the Caves in Nahal Mishmar. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Bar-Yosef, O. and Belfer-Cohen, A. 1989. The origin of sedentism and farming communities in the Levant. Journal of World Prehistory 3: 447–98.

- Bar-Yosef, O., Goring-Morris, A. N. and Gopher, A. (eds) 2010. Gilgal—Early Neolithic Occupations in the Lower Jordan Valley (The Excavations of Tamar Noy). Oxford: Oxbow.

- Brink, E. C. M. van den 2005. The ceramic ossuaries. In, van den Brink, E. C. M. and Gophna, R. (eds), Shoham (North): Late Chalcolithic in the Lod Valley, Israel: 27–46. IAA Reports 27. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Broman Morales, V. 1983. Jarmo figurines and other clay objects. In, Braidwood, L. S., Braidwood, R. J., Howe, B., Reed, C. A. and Watson, P. J. (eds), Prehistoric Archaeology Along the Zagros Flanks: 369–423. Oriental Institute Publications 105. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Broman Morales, V. 1990. Figurines and Other Clay Objects from Sarab and Cayonu. Oriental Institute Communications 25. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Busacca, G. 2017. Places of encounter: relational ontologies, animal depiction and ritual performance at Göbekli Tepe. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 27(2): 313–30.

- Çelik, B. 2011. Karahan Tepe: a new cultural centre in the Urfa area in Turkey. Documenta Praehistorica 38: 239–56.

- Costello, S. K. 2011. Image, memory and ritual: re-viewing the antecedents of writing. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 21: 247–62.

- Dietrich, O., Heun, M., Notroff, J., Schmidt, K. and Zarnkow, M. 2012. The role of cult and feasting in the emergence of Neolithic communities: new evidence from Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey. Antiquity 86(333): 674–95.

- Dietrich, O., Köksal-Schmidt, Ç., Notroff, J., Kürkçüoğlu, C. and Schmidt, K. 2014. Göbekli Tepe: preliminary report on the 2012 and 2013 excavation seasons. Neo-Lithics 1/14(1): 11–17.

- Epstein, C. 1985. Laden animal figurines from the Chalcolithic period in Palestine. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 258(1): 53–62.

- Epstein, C. 1998. The Chalcolithic Culture of the Golan. IAA Reports 4. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Fagan, A. 2017. Hungry architecture: spaces of consumption and predation at Göbekli Tepe. World Archaeology 49(3): 318–37.

- Garfinkel, Y. 1995. Human and Animal Figurines of Munhata, Israel. Paris: Association Paléorient.

- Garfinkel, Y. 1999. Neolithic and Chalcolithic Pottery of the Southern Levant. Qedem 39. Jerusalem: Institute of Archaeology, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Garfinkel, Y. 2003. Dance at the Dawn of Agriculture. Austin: Texas University Press.

- Garfinkel, Y. 2018. The evolution of human dance: courtship, rites of passage, trance, calendrical ceremonies, and the professional dancer. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 28: 283–98.

- Garfinkel, Y., Ben-Shlomo, D. and Korn, N. 2010. Sha‘ar Hagolan Vol. 3: Symbolic Dimensions of the Yarmukian Culture: Canonization in Neolithic Art. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Gourichon, L. 2002. Bird remains from Jerf El Ahmar: a PPNA site in northern Syria with special reference to the griffon vulture (Gyps fulvus). In, Buitenhuis, H., Choyke, A. M., Mashkour, M. and Al-Shiyab, A. H. (eds), Archaeozoology of the Near East, Proceedings of the 5th International Symposium on the Archaeozoology of Southwestern Asia and Adjacent Areas (Amman, June 2000): 138–52. Groningen: ARC-Publicaties.

- Gourichon, L. 2004. Faune et saisonnalité: l'organisation temporelle des activités de subsistance dans l'Épipaléolithique et le Néolithique précéramique du Levant nord (Syrie). PhD. Université Lumière-Lyon II.

- Greet, B. 2020. The role of birds in the Chalcolithic: the avian material culture from the late fifth millennium BCE in the Southern Levant. Quaternary International 626–627: 62–70.

- Helmer, D., Gourichon, L. and Stordeur, D. 2004. À l’aube de la domestication animale. Imaginaire et symbolisme animal dans les premières sociétés néolithiques du nord du Proche-Orient. Anthropozoologica 39(1): 143–63.

- Hershman, D. and Belfer-Cohen, A. 2010. ‘It’s Magic!’: artistic and symbolic material manifestations from the Gilgal sites. In, Bar-Yosef, O., Goring-Morris, A. N. and Gopher, A. (eds), Gilgal—Early Neolithic Occupations in the Lower Jordan Valley (The Excavations of Tamar Noy): 185–216. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Horwitz, L. K. and Garfinkel, Y. 1991. Animal remains from the site of Gesher, central Jordan Valley. Mitekufat Haeven (Journal of the Israel Prehistoric Society) 24: 64–76.

- Horwitz, L. K., Simmons, T., lernau, O. and Tchernov, E. 2010. Fauna from sites of Gilgal I, II, and III. In, Bar-Yosef, O., Goring-Morris, A. N. and Gopher, A. (eds), Gilgal—Early Neolithic Occupations in the Lower Jordan Valley (The Excavations of Tamar Noy): 263–95. Oxford: Oxbow Books.

- Karul, N. 2021. Buried buildings at Pre-Pottery Neolithic Karahantepe. Türk Arkeoloji ve Etnografya Dergisi 82: 21–31.

- Kenyon, K. M. 1981. Excavations at Jericho: The Architecture and Stratigraphy of the Tell. Vol. III. London: The British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem.

- Köksal-Schmidt, Ç and Schmidt, K. 2010. The Göbekli Tepe ‘totem pole’. A first discussion of an autumn 2010 discovery (PPN, Southeastern Turkey). Neo-Lithics 1/10: 74–76.

- Kozlowski S. K. 1989. Nemrik 9, a PPN Neolithic site in northern Iraq. Paléorient 15(1): 25–31.

- Le Mière, M. and Nieuwenhuyse, O. 1996. The prehistoric pottery. In, Akkermans, P. M. M. G. (ed.), Tell Sabi Abyad: Late Neolithic Settlement. Report on the Excavations of the University of Amsterdam (1988) and the National Museum of Antiquities Leiden (1991–1993) in Syria: 119–284. Leiden: Nederlands Historisch-Archaeologisch Instituut te Istanbul.

- Martin, L. and Meskell, L. 2012. Animal figurines from Neolithic Çatalhöyük: figural and faunal perspectives. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 22: 401–19.

- Martin, L., Edwards, Y. and Garrard, A. 2013. Broad spectrum or specialised activity? Birds and tortoises at the Epipalaeolithic site of Wadi Jilat 22 in the eastern Jordan steppe. Antiquity 87(337): 649–65.

- Mazurowski, R. F. 1997. Ground and Pecked Stone Industry in the Pre-Pottery Neolithic of Northern Iraq. Warsaw: Wydawnictwa Instytutu Archeologii.

- Milevski, I. 2002. A new fertility figurine and new animal motifs from the Chalcolithic in the southern Levant: finds from cave K-1 at Quleh, Israel. Paléorient 28(2): 133–41.

- Mithen, S. 2022. Shamanism at the transition from foraging to farming in Southwest Asia: sacra, ritual, and performance at Neolithic WF16 (southern Jordan). Levant 54(2): 158–89.

- Mithen, S., Finlayson, B., Smith, S., Jenkins, E., Najjar, M. and Maričević, D. 2011. An 11,600-year-old communal structure from the Neolithic of southern Jordan. Antiquity 85(328): 350–64.

- Orrelle, E. and Horwitz, K. L. 2021. Investigating hybridity: Neolithic human-bird figurines from the southern Levant. Journal of Anthropological ad Archaeological Sciences 5(4): 650–56.

- Ortega, I., Rios-Garaizar, J., Maidagan, D. G., Arizaga, J. and Bourguignon, L. 2015. A naturalistic bird representation from the Aurignacian layer at the Cantalouette II open-air site in southwestern France and its relevance to the origins of figurative art in Europe. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 4: 201–09.

- Õ֑zkaya, V. 2009. Excavations at Körtik Tepe. A new pre-pottery Neolithic a site in southeastern Anatolia. Neo-Lithics 2/09: 3–8.

- Özkaya, V., Coşkun, A. and Soyukaya, N. 2013. Körtik Tepe: First Traces of Civilization in Diyarbakır. Istanbul: Arkeoloji ve Sanat Yayınları.

- Perrot, J. and Ladiray, D. 1980. Tombes à ossuaires de la région côtière palestinienne au IV millénaire avant l'ère chrétienne. Mémoires et Travaux du Centre de Recherches Préhistoriques Français de Jérusalem Jérusalem 1. Paris: Association Paléorient.

- Peters, J. and Schmidt, K. 2004. Animals in the symbolic world of Pre-Pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, south-eastern Turkey: a preliminary assessment. Anthropozoologica 39(1): 179–218.

- Peters, J., von den Driesch, A., Pollath, N. and Schmidt, K. 2005. Birds in the megalithic art of pre-pottery Neolithic Göbekli Tepe, southeast Turkey. In, Grupe, G. and Peters, J. (eds), Feathers, Grit and Symbolism: Birds and Humans in the Ancient Old and New Worlds: 223–34. Documenta Archaeobiologiae 3. Rahden: Verlag Marie Leidort.

- Pichon, J. 1985a. A propos d’une figurine aviare a Mureybet (phase III A) 8000–7700 avant J. C. Cahiers de l’Euphrate 4: 261–64.

- Pichon, J. 1985b. Les rapaces du Tell Mureybet, Syrie, Fouilles J. Cauvin 1971–1974. Cahiers de l’Euphrate 4: 229–59.

- Russell, N. 2019. Spirit birds at Neolithic Çatalhöyük. Environmental Archaeology 24(4): 377–86.

- Russell, N. and McGowan, K. J. 2003. Dance of the cranes: crane symbolism at Çatalhöyük and beyond. Antiquity 77(297): 445–55.

- Rollefson, G. O. 2008. Charming lives: human and animal figurines in the late Epipaleolithic and early Neolithic periods in the greater Levant and eastern Anatolia. In, Bocquet-Appel, J.-P. and Bar-Yosef, O. (eds), The Neolithic Demographic Transition and Its Consequences: 387–416. New York: Springer.

- Scheftelowitz, N. and Oren, R. 2004. Giv‘at ha-Oranim: A Chalcolithic Site. Salvage Excavations Reports No. 1. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology.

- Schmandt-Besserat, D. 1997. Animal symbols at ‘Ain Ghazal. Expedition 39: 48–58.

- Schmidt, K. 1997–98. Stier, Fuchs und Kranich. Der Göbekli Tepe bei Sanhurfa und die Bilderwelt des obermesopotamischen Frühneo lithikums. Archäologie 14: 155–70.

- Schmidt, K. 2003. The 2003 campaign at Göbekli Tepe (southeastern Turkey). Neo-Lithics 2/03: 3–8.

- Schmidt, K. 2006. Sie bauten die ersten Tempel: das ratselhafte Heiligtum der Steinzeitjager. Die archaologische Entdeckung am Gobekli Tepe. München: C. H. Beck.

- Schmidt, K. 2010. Göbekli Tepe—the Stone Age Sanctuaries. New results of ongoing excavations with a special focus on sculptures and high reliefs. Documenta Praehistorica 37: 239–56.

- Schmidt, K. 2011. Göbekli Tepe. In, Ozdoğan, M., Başgelen, N. and Kuniholm, P. I. (eds), The Neolithic in Turkey: New Excavations & New Research—The Euphrates Basin: 41–83. Istanbul: Archaeology & Art Publications.

- Schmidt, K. 2012. Göbekli Tepe: A Stone Age Sancuary in South-Eastern Anatolia. Berlin: Ex oriente.

- Schmidt, K. 2013. Göbekli Tepe 2011 Yılı Raporu. Kazı Sonuçları Toplantısı 34: 79–91.

- Slingstone Travel. 2021. Visiting Göbekli Tepe: The Site that Reshaped History. Available at: https://sailingstonetravel.com/visiting-gobekli-tepe/.

- Solecki, R. L. 1981. An Early Village Site at Zawi Chemi Shanidar. Malibu, CA: Undena Publications.

- Solecki, R. L. and McGovern, T. 1980. Predatory birds and prehistoric man. In, Diamond, S. (ed.), Theory and Practice: Essays Presented to Gene Weltfish: 79–95. The Hague: Mouton.

- Starkovich, B. M. and Stiner, M. C. 2009. Hallan Çemi Tepesi: high-ranked game exploitation alongside intensive seed processing at the Epipaleolithic-Neolithic transition in southeastern Turkey. Anthropozoologica 44(1): 41–61.

- Stordeur, D. and Abbès, F. 2002. Du PPNA au PPNB: mise en lumière d'une phase de transition à Jerf el Ahmar (Syrie). Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 99(3): 563–95.

- Stordeur, D. and Lebreton, M. 2008. Figurines, pierres à rainures, «petits objets divers» et manches de Mureybet. In, Ibáñez, J. J. (ed.), Le site néolithique de Tell Mureybet (Syrie du Nord): 619–43. BAR International Series 1843. Oxford: British Achaeological Reports.

- Stordeur, D., Brenet, M., Der Aprahamian, G. and Roux, J.-C. 2000. Les bâtiments communautaires de Jerf el Ahmar et Mureybet horizon PPNA (Syrie). Paléorient 26(1): 29–44.

- Stordeur, D., Helmer, D. and Willcox, G. 1997a. Jerf el Ahmar: un nouveau site de l’horizon PPNA sur le moyen Euphrate syrien. Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française 94(2): 282–85.

- Stordeur, D. and Jammous, B. and Roux, M. 1997b. D’énigmatiques plaquettes gravées néolithiques. Archeologia 332: 36–41.

- Tchernov, E. 1993. Exploitation of birds during the Natufian and early Neolithic of the southern Levant. Archaeofauna 2: 121–43.

- Tchernov, R. 1994. An Early Neolithic Village in the Jordan Valley Part II: The Fauna of Netiv Hagdud. Cambridge: Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University.

- Von Oppenheim, M. F. 1943. Tell Halaf 1: Die Praehistorischen Funde. Berlin: W. de Gruyter.

- White, J., Finlayson, B., Makarewicz, C., Khoury F., Greet, B. and Mithen, S. 2021. The bird remains from WF16, an early Neolithic settlement in southern Jordan: Assemblage composition, chronology and spatial distribution. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 31(6): 1030–45.

- Yaroshevich, A., Bar-Yosef, O., Boaretto, E., Caracuta, V., Greenbaum, N., Porat, N. and Roskin, J. 2016. A unique assemblage of engraved plaquettes from Ein Qashish South, Jezreel Valley, Israel: figurative and non-figurative symbols of Late Pleistocene hunters-gatherers in the Levant. PloS ONE 11(8): e0160687.

- Yartah, T. 2004. Tell ‘Abr 3, un village du néolithique précéramique (PPNA) sur le Moyen Euphrate. Première approche. Paléorient 30(2): 141–58.

- Yartah, T. 2005. Les bâtiments communautaires de Tell ‘Abr 3 (PPNA, Syrie). Neo-lithics 1/05: 3–9.

- Yeomans, L. and Richter, T. 2018. Exploitation of a seasonal resource: bird hunting during the Late Natufian at Shubayqa 1. International Journal of Osteoarchaeology 28(2): 95–108.

- Yizraeli Noy, T. 1989. Gilgal I—A Pre-Pottery Neolithic site, Israel—The 1985–1987 seasons. Paléorient 15(1): 11–18.

- Zeder, M. A. and Spitzer, M. D. 2016. New insights into broad spectrum communities of the Early Holocene near east: the birds of Hallan Çemi. Quaternary Science Reviews 151: 140–59.