Abstract

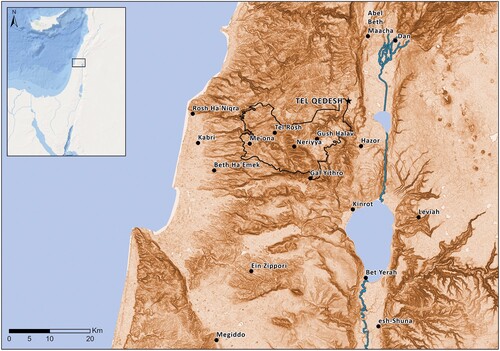

The Early Bronze Age I–II transition in the southern Levant (c. 3000 BCE) is attested by significant changes in the organization of settlement systems, and economic modes of production and distribution. This study examined settlement patterns in the mountainous Upper Galilee and adjacent regions during the Early Bronze (EB) I–II. The regional settlement history was studied using a systematic survey of archaeological sites, as well as an analysis of all available archaeological data from previous surveys and salvage excavations. This study demonstrates that, despite the complexity of surveying multi-period mountainous sites, a systematic survey can contribute to reconstructing individual site histories and the region’s history as a whole. In the Early Bronze Age, the Mountainous Upper Galilee, usually considered peripheral to the large, newly-established urban centres of the lowlands, played a significant role that has previously been overlooked. In addition, this study offers an integrative highland–lowland model for the changing settlement landscapes at this transition.

Introduction

Archaeological research in the southern Levant has tended to focus mostly on lowland regions, with upland regions attracting considerably less attention. Recent work, in Syria and Transjordan, has demonstrated the role of upland regions and other sub-optimal environments in the general trend toward rising complexity and urbanism (Bradbury et al. Citation2014; Braemer Citation2011; Lawrence Citation2012; Philip and Bradbury Citation2010; Wilkinson et al. Citation2014). Such reconstructions, however, are still rare in regard to the mountainous areas west of the Jordan (Finkelstein and Gophna Citation1993; Getzov et al. Citation2001; Joffe Citation1993; de Miroschedji Citation2013; Zertal Citation1993).

The Upper Galilee, in present-day northern Israel, is one of these mountainous regions frequently examined as a marginal periphery of the urban centres in the adjacent valleys. Located between the northern Jordan Valley to the east and the Mediterranean coast to the west, this region has been relegated to the margins of academic inquiry, and has, therefore, been the subject of little archaeological research. Consequently, this region plays a relatively marginal part in discussions on early urbanization in the Levant.

This paper discusses the results of a new regional survey, conducted by the author, in the mountainous Upper Galilee. The survey results, together with settlement data from nearby lowland regions, allows for a better understanding of the part played by the highland area of the Upper Galilee in the urbanization processes seen during the EB I–II sequence, and of the role played by this region in light of diachronic changes in settlement patterns and demography.

History of research

The Upper Galilee region is usually described as mountainous, overgrown and difficult to access (see below). These physical conditions, combined with scant and ambiguous presence in early historical sources (Aharoni Citation1957), were the basis for the hypothesis, in place until the mid-1950s, whereby the entire region was not inhabited prior to the end of the 2nd millennium BCE. Consequently, there have been very few studies on this region, and it was relegated to the margins of archaeological research in Israel (Amiran Citation1953). Nonetheless, two important regional surveys of this region were conducted, one in the 1950s by Aharoni (Citation1957), and another in the 1980s by Frankel and his colleagues (Frankel et al. Citation2001).

Aharoni’s study entailed the survey of an area covering 160 km2 at the heart of Upper Galilee. Although this was not an intensive or systematic survey, he identified 55 sites dated from the EBA to the Ottoman period (Aharoni Citation1957: 29–31), including six mounds first settled during the EBA. A much more extensive survey was conducted by Frankel et al. (Citation2001). This survey covered an area of c. 900 km2 between the Galilean coastline and the western Hula Valley, and identified 44 sites from the EBA out of a total of 400 sites from different periods. The settlement patterns that emerged from this survey were far more complex and detailed than those offered by Aharoni (Frankel et al. Citation2001: 99–101). Neither survey, however, contained systematic estimations of site sizes, nor did they provide estimates of the changes in inhabited area during different periods. Demographic trends and settlement pattern analysis were mainly based on the number of sites identified, while an individual ‘site’ was assigned to a given period based on a small number of associated potsherds. Thus, 16 sites designated as EBA (37% of the total sites dated to this period) include only one or two pottery sherds attributed to this period, while 23 sites (53%) include up to five (ibid: 73–75).

The settlement history and chronology of the coastal sites are, in contrast, better established. The survey of the Akko Plain was far more extensive (Frankel and Getzov Citation2012a; Citation2012b; Frankel et al. Citation2001: v; Peilstöcker Citation2003; see also Fig. 9 below), and most of the EBA coastal sites have been excavated, including major sites such as Kabri (Kempinski et al. Citation2002) and Bet Ha-‘Emek (Givon Citation1993), as well as small sites such as edh-Dhahab (Getzov Citation2004), and Rosh Ha-Niqra (Tadmor and Prausnitz Citation1958). Peilstöcker (Citation2003) carried out a regional study that reviewed all past surveys and excavations, and offered an updated synthesis of their data. Similarly, parts of the Hula Valley were systematically surveyed by Dayan (Citation1963), Stepansky (Citation1999; Citation2012) and Shaked (Citation2016), along with a regional study and in-depth synthesis by Greenberg (Citation2002). Likewise, major sites, such as Hazor, Dan and Tel Te’o, were also thoroughly excavated (Ben-Tor Citation1989; Citation1997; Ben-Tor et al. Citation2017; Biran et al. Citation1996; Eisenberg et al. Citation2001; Yadin et al. Citation1958; Citation1960; Citation1961). Nonetheless, the mountainous Upper Galilee, which includes a large portion of the EBA settlement system, remains less explored, with only general information available regarding EBA sites and just one published excavation, at Me‘ona (Braun Citation1996; Citation2010).

The 2014–2018 survey in the mountainous Upper Galilee

The study area and environmental background

The Upper Galilee is the highest part of Israel’s central mountain range, with a maximum elevation of 1208 m. It lies within the Mediterranean climatic zone, with an average annual precipitation of 960 mm in the highland region (Mt. Meron) and 550–600 mm in other areas. The area consists of several calcareous geological formations from the Turonian-Cenomanian, Senon and Eocene, with limestone, dolomite, chalk and chert (Levitte and Sneh Citation2013; Sneh Citation2004). The natural vegetation in most areas of the Upper Galilee is Mediterranean maquis and scrubland vegetation. Cultivated areas are mostly located at intermountain valleys and moderate chalk and basaltic plateaus (Karmon Citation1971; 178).

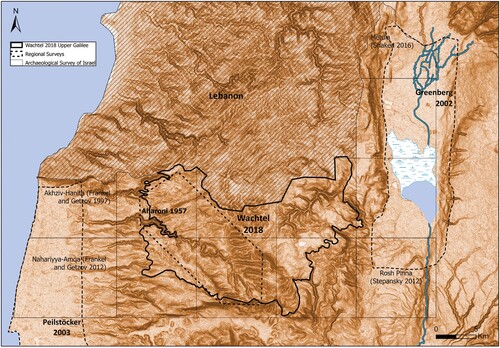

The 2014–2018 regional study revolved around the reconstruction of the settlement and demographic history of the Upper Galilee during the Bronze and Iron Ages (Wachtel Citation2018a). More than 40 settlement sites, in the heart of the mountainous Upper Galilee, dated to these periods, were subjected to a high-resolution pedestrian survey (). The modern border with Lebanon forms the northern boundary of the area. Elsewhere, the boundaries are determined by topography and landscape: the plateaus of the eastern Upper Galilee, the High Galilee (Meron–Peqi’in range) and the heights of the western Upper Galilee ().

The plateaus of the eastern Upper Galilee can be divided into several topographic sub-units, including the basalt plateaus of Dalton, Alma, Bar‘am and Yir’on. These plateaus are separated by fault lines through which the Hazor and Dishon streams drain eastward into the Hula Valley. The dominant rock formations in the plateaus of the eastern Upper Galilee are basalt from the Dalton formation, limestone of the Timrat formation, and chalk from the Menuha formation. The moderate topography of these landscape units enabled north–south transport routes, and contiguous agricultural lands. The water sources in the area — small springs — are relatively abundant and stable. According to Ottoman tax records (Hütteroth and Abdulfattah Citation1977: 175–94) and British Mandate village statistics (Hadawi Citation1970), the region’s economy was based primarily on the dry farming of grains.

The High Galilee is an elevated mountainous block consisting of two elongated ridges (Mt Meron and Mt Peqi’in) running from the south-east to the north-west. It consists of hard rocky limestone (Sakhnin formation) and hard limestone alternating with chalk (Deir Hanna formation). Due to the nature of the region’s geology, most of the water seeps underground and drains away from the area, emerging as springs along its edges. The water sources in this block are small and unstable, and most dry out during the summer. There are scant agricultural lands, scattered in small plots of shallow arable soil. A number of more continuous agricultural areas exist in the relatively extensive karst valleys in the Sasa and Hurfeish area, which are suitable for a combination of dryland farming with the cultivation of olive and fruit trees. Both in the early Ottoman period and during the British Mandate, the economy of the High Galilee was based on the dry farming of grains and fruit orchards, with a ratio of 75:25 respectively (Hadawi Citation1970; Hütteroth and Abdulfattah Citation1977; Wachtel Citation2018a: 20–29).

The western Upper Galilee consists of moderate mountain plateaus and intermountain valleys located between the high mountain region and the elongated spurs of the Western Galilee. This area encompasses the Peqi’in Valley and the height of Mi‘ilya to the south, Fassuta in the centre, and Shomera in the north. The dominant rock formations at these heights are limestone (Bina formation) and chalk (Menuha formation). The chalk areas create continuous areas of cultivatable land, with deep soil that allows for diverse agricultural activities, including dryland farming and orchards. The primary water sources in this region are cisterns in the chalk areas, and stable springs that flow in the areas where the limestone and chalk meet. The three western heights, together with the fertile Peqi’in Valley, are well-suited to transportation and agricultural cultivation. The Ottoman tax records reveal that the local economy was based equally on grain and orchards. The ratio of grain agriculture to orchards was 50:50 at the end of the 16th century and 74:26 during the British Mandate (Wachtel Citation2018a: 20–27).

The research framework

The development of new systematic field-survey methods enables better understanding of site-sizes, ancient demography and diachronic processes of ancient societies (Cherry et al. Citation1991; Drennan et al. Citation2003; Kantner Citation2008; Kowalewski Citation2008). Systematic surveys have flourished around the world in recent years (Allen et al. Citation1990; Drennan and Peterson Citation2005; Given and Knapp Citation2003; Shelach-Lavi et al. Citation2016) but have rarely been applied to Levantine archaeology (Sharon and Zionit Citation2011). A systematic, high-resolution survey, conducted in recent years at individual Levantine mound sites (Faust and Katz Citation2012; Uziel and Maeir Citation2005; Uziel and Shai Citation2010) has made a significant contribution to the understanding of local, site-specific histories, but to date, such methods have rarely been applied at the regional level in the southern Levant (Davidovich Citation2014; Sabar Citation2017; Wachtel Citation2018a; Wachtel et al. Citation2017).

The 2014–2018 regional survey of the mountainous Upper Galilee included several complementary stages. In the first stage, all available data (published and non-published) from past studies (i.e., Aharoni Citation1957; Frankel et al. Citation2001) and salvage excavations were digitized into a unified GIS database. The pottery assemblages of past surveys, now stored in the archives of the Israel Antiquities Authority, were also examined. Then, all sites previously identified in the region were visited to assess their current preservation, accessibility and surface visibility. Based on this early evaluation, a systematic survey, based on the ability to undertake effective fieldwork and provide additional meaningful information, was conducted at selected sites (see below). Given the rapid development of this region in the last decades, some EBA sites reported by previous surveys are now invisible or inaccessible: of the 62 Bronze and Iron Ages sites previously recorded in the study area, 13 are now destroyed or covered by modern villages, and four are inaccessible or covered by dense vegetation. At those sites, only a general (unsystematic) survey was conducted, together with the analysis of finds from past surveys. As noted, some EBA sites are now covered by modern constructions (i.e., Gush Halav (al-Jish) Meron, Me‘ona, Fassuta), however, multiple salvage excavations conducted at these sites provide ‘windows’ which enable analysis of the sites’ settlement histories and formation processes (Wachtel et al. Citation2017).

Survey Methods

Most Upper Galilee sites are multi-period settlements; only a few were developed into mounds (Aharoni Citation1957; Aharoni and Amiran Citation1953; Albright Citation1925). The sites include pottery scatters that can be dated, alongside remains that cannot be dated without excavation (Frankel et al. Citation2001). Pottery scatters are, therefore, primary variables for dating settlement sites and analyzing settlement dynamics (Leibner Citation2014). The main methodological problem for such reconstructions involves the estimation of both the size of the site and the changes in the size of the site’s inhabited area during different periods. This is due to continuous occupation, as well as additional processes such as erosion and diffusion of artifacts, and the partial destruction of earlier occupations during later periods. These obstacles obscure a site’s history and the broader analysis of regional settlement patterns and demographic trends (Wachtel Citationin press; Wachtel et al. Citation2017). These problems are not unique to the Upper Galilee. Various scholars have argued that a ‘site’ constitutes a problematic unit of analysis in regional studies (Dunnell and Dancey Citation1983; Gallant Citation1986; Orton Citation2000: 6; Shelach-Lavi et al. Citation2016). As a result, recent survey methods gradually shifted to quantitative and measurable spatial collection units (points or polygons) rather than using sites count alone (Drennan et al. Citation2015). The methodology developed in the current survey allows for comparing additional indicators, such as the number of collection units (polygons), their area and the quantity of pottery (rims and sherds) systematically collected. This method ensures uniformity in fieldwork and analysis, thereby eliminating some of the ambiguities that existed in earlier surveys, and adds a new dimension with regard to settlement intensity per period. The collection of survey data was based on a fixed protocol, in which each site identified in previous surveys and excavations was divided into multiple topographic units (polygons) based on structural and topographical affinities. The survey method included coverage of each polygon using transects at regular intervals of 10–15 m between surveyors, while trying to identify ancient remains on the surface. In cases where artifacts were found (pottery sherds or flint items) at a minimum threshold of three items over a 50-m stretch (minimum 3 sherds per 0.25 ha), a ‘collection unit’ was defined and systematically surveyed. The size of collection unit varied between 0.1 and 0.5 ha, depending on the characteristics of the area and the distribution of finds. Each collection unit was marked on an aerial photograph at a scale of 1:2500, and its boundaries were measured precisely using a portable GPS device. For each collection unit, a survey form was filled out, including the unit’s name, terrain features, surface visibility (high/moderate/low), number of surveyors and the time spent on artifact collection. Thus, the basic unit of analysis in this survey is not only the ‘site’, but rather a ‘collection unit’. A ‘site’ can be comprised of one or several collection units, depending on the distribution of the artifacts on the surface (Wachtel Citation2018a; Wachtel and Davidovich Citation2021; Wachtel et al. Citation2017). Each collection unit was surveyed for 20 to 40 minutes, was mapped using GPS, and received a unique code for cataloguing the artifacts collected. Pottery sherds and other artefacts were collected systematically from the surface of each polygon in order to enable a comparative spatial analysis of the overall density and quantities of pottery sherds, as well as chronological analysis of the different parts of the site. The survey of each site concluded when a considerable area surrounding continuous collections units (min. 50 m from each side) was found to be below the aforementioned threshold value. The sherds collected in the survey were scrutinized and dated using well-established regional typological schemes (e.g., Frankel et al. Citation2001; Greenberg Citation2002; Wachtel Citation2018a). The results were then plotted using ArcGIS software.

This method enabled the re-evaluation of the size estimates of most EBA sites in the mountainous Galilee. In short, the size of each site was evaluated for each period separately, based on the continuousness of collection units with datable materials from that period, in tandem with an informed estimation of the possible effects of post-depositional processes on sherd distribution (Faust and Katz Citation2012; Wachtel Citation2018a; also, Uziel and Maeir Citation2005; Shelach-Lavi et al. Citation2016). Thus, for example, the site of Tel Qedesh, previously estimated to be 10 hectares in size (Frankel et al. Citation2001: 44, site 369), turned out to be a minimum 50-hectare site, one of the largest EB II sites in the entire Levant (Wachtel and Davidovich Citation2021). On the other hand, Tell Gush Halav, which has long been considered one of the Upper Galilee’s key settlements (5 hectares according to Frankel et al. Citation2001: 41, site 340), did not exceed 2 hectares during the EBA (Wachtel et al. Citation2017).

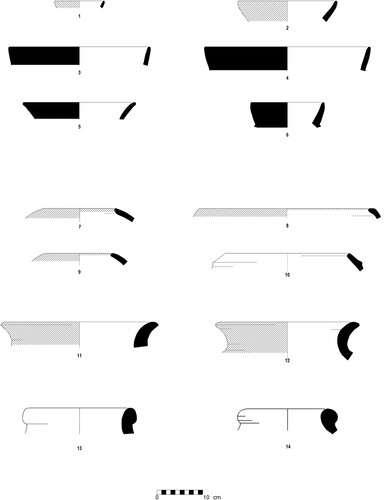

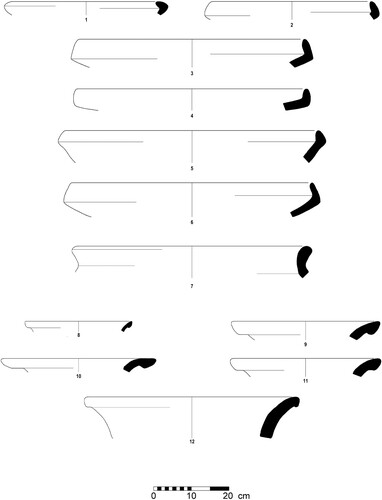

In general, more than 400 collection units were recorded during the survey, with 413 diagnostic rim fragments and an additional 631 indicative potsherds dated to the EB I–II. The EB I pottery collected in the survey is characterized by a course matrix with a high density of grits and surface slip in shades of red, brown, grey and black. In most surface collections where EB I sherds were visible, the typo-chronological range incorporates shapes, decorative elements and surface treatment typical of both EB IA and EB IB (). Early EB I (EB IA) pottery assemblages included potsherds associated with knobbed Gray Burnished Ware (GBW) bowls (Goren and Zuckerman Citation2000) and holemouth jars with ridged rims; both constitute typical ceramic components in EB IA excavated sites (e.g., Tel Te’o in the Hula Valley: Eisenberg Citation2001). Typical EB IB pottery collections in the survey are represented by painted grain-wash vessels and rail rim pithoi (Getzov Citation2004), tea-pot spouts and small loop handles of juglets or amphoriskoi. These types are well known from numerous sites in the Central Jordan and Jezreel Valleys (e.g., Braun Citation1985; Eisenberg and Rotem Citation2016; Getzov Citation2006; Joffe Citation2000; Rotem Citation2012; Citation2015; Rotem et. al. Citation2019). In cases where these types were absent in a site collection, a general EB I date was recorded.

EB II pottery is associated with the South Levantine Metallic Ware forms (SLMW), well known from the northern regions of the southern Levant (; Greenberg Citation2002; Citation2019: 70–89; Greenberg and Iserlis Citation2014; Greenberg and Porat Citation1996). In previous regional studies, this industry was allocated a wide chronological range (i.e., EB II–III). Now, however, it is clear that SLMW is primarily an EB II phenomenon, while its EB III derivatives can, in most cases, be distinguished based on comparable stratified sequences (e.g., Bet Yerah), (Getzov et al. Citation2001). Pottery typical of EB III is almost entirely absent from the record (including previous surveys and excavations) and was found at only four sites: Tel Qedesh, Tel Rosh (er-Ruweis), Tel Iqrit and Me‘ona (Aharoni Citation1957: plate VI: see also Frankel et al. Citation2001: 101; Getzov Citation2017).

The upper mountainous Galilee during the Early Bronze Age I–II

The Early Bronze Age I

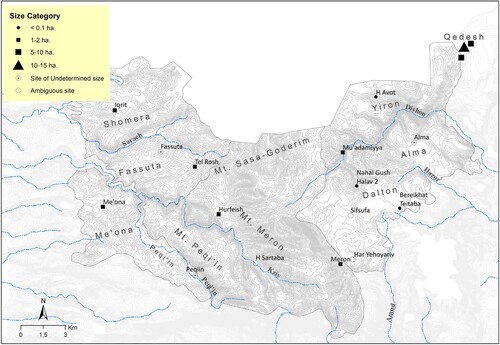

The 2014–2018 survey results show that the EB I settlement landscape included mostly small villages. A total of 15 sites are dated to the EB I; three more are inconclusive (). Most of the sites were first settled during this period, while five were also occupied during the Late Chalcolithic. Their sizes (excluding Tel Qedesh) do not exceed 2 ha (). Five sites are mounds, first settled during the EB I or earlier (Qedesh, Qedesh East, Tel Iqrit, Tel Rosh, Me‘ona). Excavations conducted at Qedesh (Aharoni Citation1957), Qedesh west (Wachtel and Davidovich Citation2021), Avot (Braun Citation2015) and Me‘ona (Braun Citation1996), exposed stratified EB I remains. Examination of the pottery types collected during the survey, in combination with information from previous studies, demonstrates the considerable difficulty in determining an overall continuity between EB IA and EB IB occupations. Eight sites include small quantities of both EB IA and EB IB indicative potsherds. At the other sites identification is to general EB I only (). The limited quantity of EB I pottery recorded (as compared with EB II below) is not related to identification difficulties: in other words, the small quantity of EB I pottery found, implies less intense settlement activity compared to EB II. More importantly, recent studies have shown that the EB I in the southern Levant lasted for c. 700 years (3700–3050/3000 BCE), while the EB II lasted for only 100–150 years (3050/3000–2900 BCE; Regev et al. Citation2012; Citation2014; Citation2019). Hence, the exceptional length of the EB I period should be considered in conjunction with the number of sites, pottery sherds and collection units recorded in the systematic survey. The evidence may hint at intermittent occupation or utilization of the same locations/niches during several phases, rather than overall continuity. To overcome the disparity in duration between the two periods, the length of each period can be converted into a 100-years index (or ‘time-block’; e.g., Drennan et al. Citation2015: 36–40; Wilkinson et al. Citation2014). Such indexing suggests an average of only 2.5 EB I sites per century ().

Figure 5 EB I settlements within the study area, according to general size categories. Empty circle = sites with ‘undetermined size’; question mark = ambiguous site.

Table 1 List of EB I and EB II sites in the study area

Table 2 A summary of the survey results: collection units and pottery count for EB I and EB II

The distribution of settlements across the different topographical units is uneven. Nine sites are located in the eastern part of the research area, near or within the basalt plateaus west of Qedesh (H. Avot, Alma, Mu’adamiyya, Bereikhat Teitaba), or at the foot of Har Meron (Nahal Gush Halav, Meron). Five sites are known from the western Upper Galilee, associated with the deep soil of intermountain valleys and calcareous plateaus (Tel Iqrit, Tel Rosh, Me‘ona, Peqi’in). The High Galilee (Mt. Meron and Mt. Peqi’in) remained almost empty of permanent settlements during EB I, with only one site, H. Hurfeish, at the northern fertile foothill of Mt. Meron. Geographically, the EB I sites are associated with deep arable land in intermountain valleys and heights, with stable water sources. These substantial areas, suitable for Mediterranean agriculture, were first settled during the EB I and then re-settled over multiple periods, over time some developed into mounds.

Tel Qedesh, in the eastern part of the research area, is one of the most significant sites surveyed in this project. The survey results from Qedesh clearly illustrate the contribution of systematic survey to the reconstruction of site histories and regional demographic fluctuations over time (Wachtel and Davidovich Citation2021). Pottery sherds typical for both EB IA and EB IB were collected from different areas around the perimeter of the mound (20 hectares), as well as at Qedesh East and at Qedesh West. Although the size of Qedesh during the EB I is, as yet, unclear, it significantly exceeds all other sites surveyed. A total of 69 collection units contained EB I pottery: 38 at Tel Qedesh and its surroundings (Qedesh East and Qedesh West) and 31 at the other 9 sites systematically surveyed. Likewise, a total of 45 rims and 183 body sherds were collected in the survey, with 29 rims and 131 typical body sherds collected at Qedesh alone ().

The Early Bronze Age II

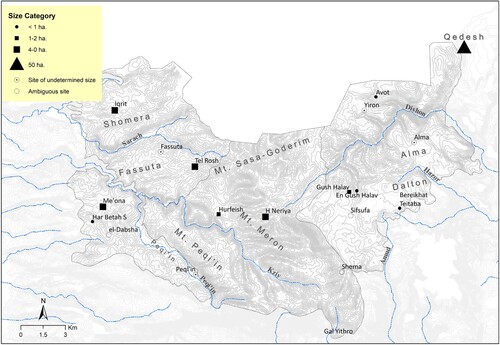

The EB II shows significant demographic growth. There are 17 definitive settlements of various sizes, located in differing environments, and four more questionable () Although the number of sites has not changed dramatically, the number of collection units and diagnostic pottery sherds clearly indicate demographic increase ( and see below). EB I pottery sherds were observed at 12 of the EB II sites. Of the sites first settled during EB II, three were located on high ground (Yiron, Gush Halav and H. Neriyya), while one was located near the Gush Halav Creek (Wachtel et al. Citation2017). The demographic peak between the periods is not well reflected by the number of sites, but is significant when considering the length of EB II. Dividing the number of sites into the 100–150 years of this period, clearly shows the intensity of EB II settlement activity compared with the EB I ().

Figure 6 EB II settlements within the study area, according to general sizes categories. empty circle = sites with ‘undetermined size’; question mark = ambiguous site.

The most significant site was Tel Qedesh, which reached its zenith during the EB II. The sheer size of the site (minimum 50 hectares) and its complex fortification system, in tandem with the preliminary evidence of intra-site division and planning, indicate a regional centre located within the upland region (Wachtel and Davidovich Citation2021). Other sites in the Eastern Heights are much smaller, with an estimated area of 1–2 hectares (Gush Halav, Alma) or less (Avot, Bereikhat Teitaba).

Evidence of the regional demographic increase becomes much more pronounced when analysing different data variables derived from the systematic survey, thereby illustrating the contribution of such a survey to the reconstruction of demographic trends. EB II SLMW pottery is very easy to recognize. To reduce possible bias between different types of pottery and wares, both body sherds and indicative rims were collected; these were counted and analyzed separately after washing. A comparison of the number of rims, body sherds and collection units () shows similar demographic trends which are much more reliable than the number of sites alone (Drennan et al. Citation2015). One hundred and thirty collection units include EB II pottery, twice as many as EB I. The count of indicative rim fragments and body sherds is even more significant, at 368 and 448 respectively, compared with only 45 and 183 for EB I (). Sixty-eight collection units from Qedesh alone, with 179 rim fragments and 251 typical body sherds collected across different parts of the site.

In the High Galilee, a large enclosed (fortified?) settlement of 4–5 hectares, was first settled during the EB II at H. Neriyya on Mt. Meron (11 collection units with 65 EB II rim fragments). The site’s layout and characteristics resemble the EB II enclosed/fortified settlements known from the Golan, the Lower Galilee and Samaria (Gal Citation1988; Paz Citation2018; Wachtel Citation2018b; Zertal Citation1993). As the site of H. Neriyya was resettled during the Middle Bronze, Iron Age, Persian and Byzantine periods, its fortifications cannot be dated to the EB II without excavation. Another fortified site with similar characteristics was recorded at Ein Yanai, south of Safed, which is outside the current area of research; this fortified site was first settled during EB II and is estimated to be 3 hectares in size (Frankel et al. Citation2001: 37, site 296).

In the western part of the study area the settlement locations that characterized EB I continued; the settled areas of the sites saw general growth. Tel Iqrit is estimated to have been 4 hectares during the EB II, while Me‘ona and Tel Rosh are both estimated at 6 hectares. The Me‘ona site, west of Mt. Meron, includes 12 collection units with 74 rim fragments. Excavations by Braun in 1989 revealed both EB I and EB II occupations, with a massive EB II fortification, including a semi-circular tower (Braun Citation1996). The recent survey results, supplemented by the plotting of seven subsequent salvage excavations conducted between 1989 and 2017, support Braun’s results regarding site size and layout — an upper mound and a lower inhabited area (; ).

Table 3 Me‘ona site (Horvat Rashim): salvage excavations between 1989 and 2017 in

Tel Rosh, another multi-layered site in the central Upper Galilee, about 7 km north-east of Me‘ona, is known from previous work as a major Early Bronze Age site (Amiran Citation1953). The current survey showed that it was first settled during the EB I (1–2 hectares), reaching its zenith during EB II (5–6 hectares; ). Both Amiran and Aharoni previously estimated the site to be 2.5 hectares (Aharoni Citation1957: 14; Amiran Citation1953); while Frankel et al. (Citation2001: 35, site 131) estimated it at c. 9 hectares. This discrepancy in estimated size clearly demonstrates the challenge of determining the size and occupational history of multi-period mountainous sites, and the importance of a quantified systematic field survey to help clarify the discrepancies. Additional sites were recorded at Fassuta and Peqi’in, but their area could not be determined due to coverage by modern settlements.

Integrative upland–lowland model

The EB I–II sequence in the mountainous Upper Galilee shows a substantial demographic increase during EB II. This process was accompanied by the creation of a settlement hierarchy, the emergence of fortified centres, and evidence of a specialized system of production and distribution associated with the SLMW industry (Greenberg Citation2019: 77–92). The emergence of Qedesh as a highland mega-site suggests that it might have played an important role in the SLMW trade system, extending to a large territory beyond the Galilean mountainous region (Wachtel and Davidovich Citation2021). Consequently, an integrative upland–lowland model is required to expand the view to the nearby valleys of northern Israel. Several trajectories of settlement dynamics have been proposed for the EB I–EB II transition in this region, indicating the diverse nature and pace of urbanization resulting from the different environmental and social conditions that characterized different areas (Greenberg Citation2003).

In the Western Galilee, a linear evolutionary model of increasing complexity has been described (Frankel et al. Citation2001: 100–01; Peilstöcker Citation2003: 388–414), while in the Hula Valley to the east, a settlement gap of hundreds of years during the EB IB phase, followed by rapid colonization in the EB II, has been reported (Greenberg Citation1996; Citation2002). In the mountainous Lower Galilee, the majority of EB IB sites were abandoned and only a few persisted into the EB II (Gal Citation1992; Portugali and Gophna Citation1993). The mountainous Upper Galilee, located between these sub-regions, allows for an inter-regional examination and upland–lowland model of settlement dynamics.

Inter-regional settlement database

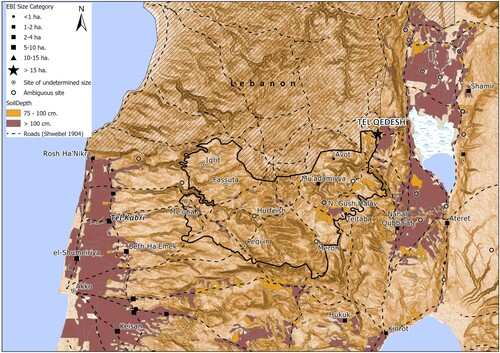

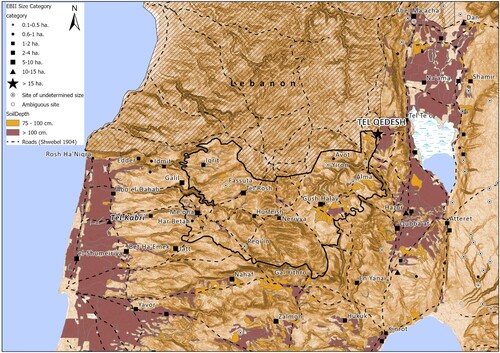

One hundred and three EBA sites have been recorded, by various studies, between the Hula Valley and the Galilean coastline (). These studies include 100 km2 map surveys conducted as part of the Israel Survey (Aviam and Shalem Citation2020; Frankel and Getzov Citation2012a; Citation2012b; Shaked Citation2016; Stepansky Citation2012), as well as regional studies of the Hula Valley (Greenberg Citation2002; Stepansky Citation1999) and the Akko plain (Peilstöcker Citation2003). The surveys vary greatly in scope, intensity and resolution, and their site size estimates usually reflect general assessments by the surveyors. However, presenting this settlement data from different phases at an inter-regional scale significantly contributes to identifying diachronic changes and supra-regional trajectories. In order to combine the data from different surveys, the sites were digitized to a unified Geo-database (Using ArcGIS PRO by ESRI), classified by general size categories and displayed accordingly in periodic maps ().

Figure 10 EB I sites by size categories, soils and main routes according to a PEF map from the 1880s (Conder and Kitchener Citation1881; Schwöbel Citation1904). Empty circle = sites with ‘undetermined size’; question mark = ambiguous site.

Figure 11 EB II sites by size categories, soils and main routes according a PEF map from the 1880s (Conder and Kitchener Citation1881; Schwöbel Citation1904). Empty circle = sites with ‘undetermined size’; question mark = ambiguous site.

The EB I settlement data allows for a hypothetical division of this transect into eastern and western settlement systems, one in the Eastern Upper Galilee and the Hula Valley, and second in the coastal plain and western Galilee (). Similar settlement distribution was suggested for the Middle and Late Bronze Ages city-states of Hazor and Kabri, in which central place theory was used in a deterministic or mechanical manner to create a neat map of territorial polities (Finkelstein Citation1996; Na'aman Citation1997; Yasur-Landau et al. Citation2008). An uncritical look at a map showing EB I settlements can lead to a similar spatial setup, potentially associated with Qedesh and Kabri. However, the nature of EB I sites, the limited survey collections, in tandem with the long duration of the period, make such reconstruction difficult. More importantly, it creates clear bias with regard to the EB II, which can be balanced by the use of the 100-years index. The nine EB I sites in the eastern Upper Galilee and 19 sites in the Hula Valley (Greenberg Citation2002: 73), averaged by a 100-year index, result in an average of 2.8 sites per century: accordingly, the reconstruction of settlement clusters, or central places, seems less likely. According to Greenberg, most of the valley settlements are dated to the early or middle part of the period, following a severe drop in the number of occupations in its later part. During this time, Qedesh and the Eastern Heights continued without dramatic fluctuations. As suggested above, I tend to interpret this layout as intermittent occupation or utilization of the same locations/niches during several phases, rather than overall continuity or hiatus throughout the later part of the EB I. These niches are usually located on level ground and in small intermontane valleys of soft chalk or on basalt plateaus which contain continuous arable lands and stable water sources (). These locations are typical of Mediterranean agriculture that combines dryland farming with the cultivation of olive and fruit trees.

On the coastal plain and in the foothills of the Western Galilee, a fairly extensive settlement system was reported, with a clear hierarchical distribution of site sizes, which usually indicates a developed system that maintains integration between its various parts. Thirteen sites were recorded, and nine of them were excavated: general EB IA–IB continuity was reported from these excavations (Peilstöcker Citation2003: 389). Tel Kabri, whose area during the period was estimated at 9 hectares (Kempinski et al. Citation2002), was probably the central settlement in this region, together with nearby Bet Ha-‘Emek, estimated at 6 hectares. Other sites (Rosh Ha-Niqra, el-Shumeiriya, Abu al–Dahab and Nahariya north) were estimated at 1–2 hectares. Most of the occupations, however, were small and did not, apparently, exist continuously for 600–700 years. Given the length of this period (Regev et al. Citation2012; Citation2014; Citation2019) and the nature of the sites, the reconstruction of a hierarchical settlement system should be viewed with caution.

An overview of the settlement system, spanning from the Hula Valley to the coast during EB II, reveals significant development in the number of settlements and settlement hierarchy (). The considerable growth during this period is evidenced by the consolidation of sites in locations that were already settled in EB I and the establishment of dozens of new settlements in previously uninhabited areas.

In the Eastern Upper Galilee, there was continuity between EB I and EB II at most sites, and a number of new elevated settlements (Gush Halav, H. Neriyya, Ein Yanai) were established. The site at Qedesh, which occupied at least 50 hectares at this time, also shows rapid growth. Indeed, at this time the Qedesh site was larger than all other settlements in the mountainous Galilee combined (30 hectares), and only slightly smaller than the total settled land in the Hula Valley (60–70 hectares; Greenberg Citation1996: 154). During this period there was a burst of settlement, with dozens of new sites established along the transport routes that traversed the Hula from north to south and from east to west. Several central sites were established at key transportation nodes along these routes (Dan, Abel Beth Maacha and Hazor), and they continued to be important throughout the ensuing periods. A wide range of sizes appeared for the first time during the EB II: Tel Qedesh at 50 hectares; Dan, Abel Beth Maacha and Hazor estimated to have been 10–20 hectares in size; followed by smaller sites of 3–6 hectares in the Hula Valley (Mallaḥa, Na’ama, Shamir and Ateret) and mountainous Galilee (Ein Yanai, H. Neriyya, Tel Rosh and Me‘ona site). Other sites in the Hula and Eastern Galilee were estimated to be 2 hectares or smaller.

A fairly balanced settlement system persisted in the Western Galilee and coastal plain, with Kabri as its main central site. At the same time, there is evidence of demographic growth and an expansion of settlements toward the Western Upper Galilee mountainous areas. The number of sites in this part of the region doubled during EB II, with two-thirds of the new sites appearing in the mountainous areas of the Western Galilee. The settled area of this region is estimated to have been some 75.5 hectares (Peilstöcker Citation2003: 408). Obvious concurrent growth occurred in the size of sites established earlier, during the EB I, along the western heights, especially Tel Rosh, Tel Iqrit and Me‘ona.

Finkelstein (Citation1995) has proposed characterizing the spatial-political system of the southern Levant during this period via the ‘peer polities’ model (Renfrew Citation1986); several political entities of similar status and influence, resembling the city-states model of the 2nd millennium BCE (Finkelstein Citation1995: 60). He divided the entire region using polygons centred on the largest known sites from the period (10–20 hectares; Broshi and Gophna Citation1984), with most of the mountainous Upper Galilee falling under Qedesh’s sphere of influence (previously estimated at 10 hectares); the northern Jordan Valley was divided between Tel Dan and Tel Bet Yeracḥ, while the coastal plain and Akko Valley were assigned to Kabri’s sphere of influence.

The power of Tel Qedesh and the upland settlements as reflected in the present study, indicates that there was a far more complex settlement system in the Upper Eastern Galilee and Hula Valley than that proposed by Finkelstein. Greenberg (Citation2002) has suggested that during EB II there was a well-developed system of agriculture and trade in the Hula Valley and its environs that can be characterized as a sort of ‘embryonic state’. His suggestion was based on population density, the diverse and well-established settlement pattern, and evidence of specialization and industrialization in the production of SLMW. Greenberg’s theory is supported, I believe, by the examination of supra-regional settlement models. Tel Qedesh is the largest site and, together with the Hula Valley sites, indicates the existence of a well-developed settlement system, something characteristic of a more complex system than the ‘peer polities’ model. The specialized production of pottery and its large-scale distribution across the region, allow the identification of expansive trade ties and a high level of integration between different regions and environments.

Demographic expansion into new regions and environments is not unique to the Upper Galilee. Similar processes are familiar from various parts of the northern and southern Levant, including the settlement of mountainous, steppe and desert areas that experienced greater integration and occupation compared to the previous period (Bradbury et al. Citation2014; Braemer Citation2011; Philip and Bradbury Citation2010). These expansions, however, represent earlier phenomena and are usually interpreted as related to nomadic or semi-nomadic communities. The Upper Galilee, at the heart of the SLMW system, represents a process in which sedentary populations established new permanent sites (sometimes fortified) creating a hierarchical settlement system. This supports the theory of different timings and trajectories of expansion into different sub-optimal regions, and different pathways across different regions and environments.

In the current regional context this spatial expansion during EB II is also typical of different environments (in both highlands and lowlands). Nevertheless, they both require a relatively large investment of labour in preparing the landscape for agricultural and settlement activities.

Settlement in the mountainous areas during EB I is associated with environments typical of Mediterranean agriculture — combining grain and orchards (as evident in data from the most recent centuries). The mountainous sites that were first settled during EB II (such as Neriyya, Ein Yanai and others) are located in sub-optimal environments with poorer soil and water resources. Settlement of these areas required intensive labour to prepare the land for cultivation, including clearing the existing forest, removing stones and possibly constructing terraces (Philip Citation2003). The Hula Valley, in contrast, is very rich in land and water resources, but intensive settlement in the valley required considerable investment in draining swamplands and constructing irrigation systems. In sum, extensive settlement of these regions requires a significant initial investment. Thus, it appears that the primary motive for the expansion of settlements into these areas was demographic and economic, but also linked to the emergence of political entities with organizational and management capabilities.

This demographic growth and development of settlements is not characteristic of the entire northern part of the southern Levant. A gap or decline in settlements during the transition to EB II has been observed for the coastal plain (Faust and Ashkenazy Citation2007), the western part of the Jezreel Valley (Finkelstein et al. Citation2006), the middle Jordan Valley and the eastern Lower Galilee (Greenberg Citation2019: 75). It is possible, as proposed by Greenberg, that the rapid demographic growth in the Upper Galilee is related to migration from the middle Jordan Valley or other neighbouring regions. This growth may also be linked to the development of a new agricultural-economic system based, among others, on a combination of a Mediterranean agricultural economy and the production and distribution of pottery products. The identification of the locus of production of SLMW and the fact that it was widely distributed across an extensive region, assist in understanding the system of economic ties between the Hula Valley (and/or southern Lebanese Beqaa Valley), the coastal plain, the Lower Galilee and the Jezreel and Beit She’an valleys. The central site of Qedesh and secondary centres in the Hula Valley and mountainous Galilee may have served as a bridge connecting these industries with consumers in the highlands and along the coast (; see Iserlis et al. Citation2019). The location and centrality of Qedesh, in proximity to the SLMW pottery production site in the northern Hula Valley, while straddling a major transport route to the Upper Galilee and the coast (Schwöbel Citation1904), indicate that the site played a key role in this system. Additional sites established along transport routes that traverse the Upper Galilee (Neriyya, Tel Rosh and Me‘ona site) suggest that the Mt. Meron area was, potentially, a cultural and commercial bridge between the pottery production centre and consumers in the Western Galilee and along the coast. This formation, however, did not last long. The contraction of Qedesh and its associated settlement system before the transition to EB III is an overt testimony to the experimental nature of early Levantine urbanization, and to the fragility and vulnerability of newly formed urban structures.

Acknowledgements

I wish to thank Roi Sabar for his co-directorship of the field survey at Qedesh and Gush Halav, and to Uri Davidovich for co-directorship of the Hebrew University Expedition to Tel Qedesh (https://sites.google.com/view/huqedesh/home). Also, I wish to thank the team members and volunteers of the Upper Galilee Survey 2014–2018. This study was supported by the Israel Science Foundation (Grant 1534/18) and several funds at the Hebrew University: The Ruth Amiran Fund and the Hecht Fund of the Institute of Archaeology; the Mandel School Grant for Research Initiative for advance studies in the humanities, and the Martin Buber Society of Fellows in the Humanities and Social Sciences.

References

- Aharoni, Y. 1957. The Settlement of the Israelite Tribes in Upper Galilee. Jerusalem: Magnes (Hebrew).

- Aharoni, Y. and Amiran, R. 1953. Researches in Upper Galilee. Bulletin of the Israel Exploration Society 17: 126–37 (Hebrew).

- Albright, W. F. 1925. Bronze Age mounds of northern Palestine and the Hauran: the spring trip of the School in Jerusalem. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 19: 5–19. doi: 10.2307/1355306

- Allen, K. M. S., Green, S. W. and Zubrow, E. 1990. Interpreting Space: GIS and Archaeology. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Amiran, R. 1953. Khirbet Tell er-Ruweisa in the Upper Galilee. Eretz-Israel 2: 117–26 (Hebrew).

- Aviam, M. and Shalem, D. 2020. Land of lost villages: Map of Shomera (3), (Land of Galilee 6). Tzemach: Kinneret Academic College, Ostracon.

- Ben-Tor, A. (ed.) 1989. Hazor III–IV: An Account of the Third and Fourth Seasons of Excavations, 1957–1958 (Text). Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society.

- Ben-Tor, A. (ed.) 1997. Hazor V: An Account of the Fifth Season of Excavations, 1968. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society.

- Ben-Tor, A., Zuckerman, S., Bechar, S. and Sandhaus, D. (eds) (2017) Hazor VII: the 1990–2012 Excavations — The Bronze Age. Jerusalem: The Israel Exploration Society.

- Biran, A., Ilan, D. and Greenberg, R. 1996. Dan I: A Chronicle of the Excavations, the Pottery Neolithic, the Early Bronze Age and the Middle Bronze Age Tombs. Jerusalem: Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion.

- Bradbury, J., Braemer, F. and Sala, M. 2014. Fitting upland, steppe, and desert into a ‘big picture’ perspective: a case study from northern Jordan. Levant 46: 206–29. doi: 10.1179/0075891414Z.00000000042

- Braemer, F. 2011. Badia and maamoura, the Jawlan/Hawran regions during the Bronze Age: landscapes and hypothetical territories. Syria. Archéologie, Art et Histoire 88: 31–46.

- Braun, E. 1985. En Shadud: Salvage Excavations at a Farming Community in the Jezreel Valley, Israel. BAR International Series 249. Oxford: BAR.

- Braun, E. 1996. Salvage excavations at the Early Bronze Age site of Me‘ona: final report. ‘Atiqot 28: 1–30.

- Braun, E. 2010. The Early Bronze Age site of Me‘ona in the western Galilee. ‘Atiqot 62: 1–15.

- Braun, E. 2012. The Early Bronze Age site of Me‘ona in the western Galilee. ‘Atiqot 60: 1–15.

- Braun, E. 2015. Two seasons of rescue and exploratory excavations at Horbat ‘Avot, Upper Galilee. ‘Atiqot 83: 1–67.

- Broshi, M. and Gophna, R. 1984. The settlement and population of Palestine in the Early Bronze Age II–III. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 253: 41–53. doi: 10.2307/1356938

- Cherry, J. F., Davis, J. L. and Mantzourani, E. 1991. Landscape Archaeology as Long-Term History: Northern Keos in the Cycladic Islands. Monumenta Archaeologica. Los Angeles: University of California.

- Conder, C. R. and Kitchener, H. H. 1881. The Survey of Western Palestine I: Galilee. London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Davidovich, U. 2014. The Judean Desert during the Chalcolithic, Bronze and Iron Ages (Sixth–First Millennia BCE): Desert and Sown Relations in light of Activity Patterns in a Defined Desert Environment. PhD. The Hebrew University, Jerusalem (Hebrew, English Abstract).

- Dayan, Y. 1963. Archaeological Survey at the Hula Valley. Kibbutz Dan: Bet Ussishkin (Hebrew).

- Drennan, R. D. and Peterson, C. E. 2005. Communities, settlements, sites, and surveys: regional-scale analysis of prehistoric human interaction. American Antiquity 70(1): 5–30. doi: 10.2307/40035266

- Drennan, R. D., Peterson, C. E., Indrisano, G., Mingyu, T., Shelach, G., Yanping, Z. and Zhizhong, G. 2003. Approaches to regional demographic reconstruction. In, Regional Archaeology in Eastern Inner Mongolia: A Methodological Exploration: 152–65. Pittsburgh: Center for Comparative Archaeology.

- Drennan, R. D., Berrey, C. A. and Peterson, C. E. 2015. Regional Settlement Demography in Archaeology. New York: Eliot Werner Publications.

- Dunnell, R. C. and Dancey, W. S. 1983. The siteless survey: a regional scale data collection strategy. Advances in Archaeological Method and Theory 6: 267–87. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-003106-1.50012-2

- Eisenberg, E. 2001. Pottery of strata V–IV, the Early Bronze Age I. In, Eisenberg, E. Gopher, A. and Greenberg, R. (eds), Tel Te’o: A Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Early Bronze Age Site in the Hula Valley: 117–31. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 13. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Eisenberg, E., Gopher, A and Greenberg, R. 2001. Tel Te’o: A Neolithic, Chalcolithic, and Early Bronze Age Site in the Hula Valley. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 13. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Eisenberg, E. and Rotem, Y. 2016. The Early Bronze Age IB pottery assemblage from Tel Kitan, Central Jordan Valley. Israel Exploration Journal 66(1): 1–33.

- Faust, A. and Ashkenazy, Y. 2007. Excess in precipitation as a cause for settlement decline along the Israeli coastal plain during the third millennium BC. Quaternary Research 68(1): 37–44. doi: 10.1016/j.yqres.2007.02.003

- Faust, A. and Katz, H. 2012. Survey, shovel tests and excavations at Tel ‘Eton: on methodology and site history. Tel Aviv 39: 158–85. doi: 10.1179/033443512X13424449373740

- Finkelstein, I. 1995. Two notes on Early Bronze Age urbanization and urbanism. Tel Aviv 22: 47–69. doi: 10.1179/tav.1995.1995.1.47

- Finkelstein, I. 1996. The territorial-political system of Canaan in the Late Bronze Age. Ugarit-Forschungen 28: 221–55.

- Finkelstein, I. and Gophna, R. 1993. Settlement, demographic, and economic patterns in the highlands of Palestine in the Chalcolithic and Early Bronze periods and the beginning of urbanism. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 289(1): 1–22. doi: 10.2307/1357359

- Finkelstein, I., Halpern, B., Lehmann, G. and Niemann, H. M. 2006. The Megiddo Hinterland Project. In, Finkelstein, I., Ussishkin, D. and Halpern, B. (eds), Megiddo IV: The 1998–2002 Seasons: 705–76. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

- Frankel, R. and Getzov, N. 2012a. Map of Akhziv (1), Map of Ḥanita (2). Archaeological Survey of Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority. Available at: http://www.antiquities.org.il/survey/new/default_en.aspx.

- Frankel, R. and Getzov, N. 2012b. Map of ‘Amqa (5). Archaeological Survey of Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority. Available at: http://www.antiquities.org.il/survey/new/default_en.aspx.

- Frankel, R., Getzov, N., Avi’am, M. and Degani. A. 2001. Settlement Dynamics and Regional Diversity in Ancient Upper Galilee: Archaeological Survey of Upper Galilee. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 14. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Gal, Z. 1988. Ḥ. Shaḥal Taḥtit and the ‘early enclosures’. Israel Exploration Journal 38: 1–5.

- Gal, Z. 1992. Lower Galilee during the Iron Age. American Schools of Oriental Research Dissertation Series 8. Winona Lake: Eisenbrauns.

- Gallant, T. W. 1986. Background noise and site definition: a contribution to survey methodology. Journal of Field Archaeology 13: 404–18.

- Getzov, N. 2004. Notes on the material culture of western Galilee in the Early Bronze Age IB in light of the Abu edh-Dhahab excavations. ‘Atiqot 48: 35–50.

- Getzov, N. 2006. The Tel Bet Yerah Excavations 1994–1995. IAA reports 28. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Getzov, N. 2017. Horbat Rashim. Hadashot Arkheologiyot. Excavations and Surveys in Israel 129. Available at: http://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=25274.

- Getzov, N., Paz, Y. and Gophna, R. 2001. Shifting Urban Landscapes During the Early Bronze Age in the Land of Israel. Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing.

- Given, M. and Knapp, A. B. 2003. The Sydney Cyprus Survey Project: Social Approaches to Regional Archaeological Survey. Monumenta Archaeologica Vol. 21. Los Angeles, CA: Cotsen Institute of Archaeology, University of California.

- Givon, S. 1993. The Excavation at Beit Ha‘Emek 1973. Tel Aviv: Ramot Publishing (Hebrew).

- Goren, Y. and Zuckerman, S. 2000. An overview of the typology, provenance and technology of the Early Bronze I Gray Burnished Ware. In, Philip, G. and Baird, D. (eds), Ceramics and Change in the Early Bronze Age of the Southern Levant: 165–82. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Greenberg, R. 1996. The Early Bronze Age levels. In, Biran, A., Ilan, D. and Greenberg, R. (eds), Dan I: A Chronicle of the Excavations, the Pottery Neolithic, the Early Bronze Age and the Middle Bronze Age Tombs: 83–160. Jerusalem: Hebrew Union College.

- Greenberg, R. 2002. Early Urbanizations in the Levant: A Regional Narrative. London: Leicester University Press.

- Greenberg, R. 2003. Early Bronze Age Megiddo and Bet Shean: discontinuous settlement in sociopolitical context. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16: 17–32. doi: 10.1558/jmea.v16i1.17

- Greenberg, R. 2019. The Archaeology of the Bronze Age Levant: from Urban Origins to the Demise of City-States, 3700–1000 BC. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Greenberg, R. and Iserlis, M. 2014. The Early Bronze Age pottery industries. In, Greenberg, R. (ed.), Bet Yerah, The Early Bronze Age Mound, Volume II: Urban Structure and Material Culture, 1933–1986 Excavations: 53–150. Israel Antiquities Authority Reports 54. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority.

- Greenberg, R. and Porat, N. 1996. A third millennium Levantine pottery production center: typology, petrography, and provenance of the Metallic Ware of northern Israel and adjacent regions. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 301: 5–24. doi: 10.2307/1357293

- Hadawi, S. 1970. Village Statistics, 1945: A Classification of Land and Area Ownership in Palestine, with Explanatory Notes (No. 34). Beirut: Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- Hütteroth, W. D. and Abdulfattah, K. 1977. Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late Century. Erlangen: Fränkische Geographischeges.

- Iserlis, M., Steiniger, D. and Greenberg, R. 2019. Contact between first dynasty Egypt and specific sites in the Levant: new evidence from ceramic analysis. Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 24: 1023–40.

- Jaffe, B. G. 2010. Khirbat ‘Alya. Hadashot Arkheologiyot — Excavations and Surveys in Israel 122 Available at: https://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=1583&mag_id=117.

- Joffe, A. H. 1993. Settlement and Society in the Early Bronze age I and II, Southern Levant: Complementarity and Contradiction in a Small-scale Complex Society. Sheffield: Sheffield Academic Press.

- Joffe, A. H. 2000. The Early Bronze Age Pottery from Area J. In, Finkelstein, I., Ussishkin, D. and Halpern, B. (eds), Megiddo III: The 1992—1996 Seasons: 161–85. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 18. Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology, Tel Aviv University.

- Kantner, J. 2008. The archaeology of regions: from discrete analytical toolkits to ubiquitous spatial perspective. Journal of Archaeological Research 16: 37–81. doi: 10.1007/s10814-007-9017-8

- Karmon, Y. 1971. Israel: Regional Geography. London: Wiley Interscience.

- Kempinski, A., Scheftelowitz, N. and Oren, R. 2002. Tel Kabri: The 1986–1993 Excavation Seasons. Monograph Series of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 20. Tel Aviv: Emery and Claire Yass Publications in Archaeology.

- Kowalewski, S. A. 2008. Regional settlement pattern studies. Journal of Archaeological Research 16: 225–85. doi: 10.1007/s10814-008-9020-8

- Lawrence, D. 2012. Early Urbanism in the Northern Fertile Crescent: A Comparison of Regional Settlement Trajectories and Millennial Landscape Change. PhD. University of Durham.

- Leibner, U. 2014. Determining the settlement history of Hellenistic, Roman, and Byzantine sites in the Galilee, Israel: comparing surface, subsurface, and stratified artifact assemblages. Journal of Field Archaeology 39(4): 387–400. doi: 10.1179/0093469014Z.00000000088

- Lerer, Y. 2006. Khirbat ‘Alya. Hadashot Arkheologiyot. Excavations and Surveys in Israel 118. Available at: https://www.hadashot-esi.org.il/Report_Detail_Eng.aspx?id=305&mag_id=111.

- Levitte, D. and Sneh, A. 2013. Zefat, Geological Map of Israel, 1:50000. Jerusalem: Geological Survey.

- de Miroschedji, P. 2013. The southern Levant (Cisjordan) during the Early Bronze Age. In, Steiner, M. L. and Killebrew, A. E. (eds), The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of the Levant c. 8000–332 BC: 307–29. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Na'aman, N. 1997. The network of Canaanite Late Bronze kingdoms and the city of Ashdod. Ugarit-Forschungen 29: 599–626.

- Orton, C. 2000. Sampling in Archaeology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Paz, Y. 2018. Leviah, an Early Bronze Age Fortified Town in the Megalithic Landscape of the Golan. Land of Galilee 4. Tzemach: Kinneret Academic College, Ostracon.

- Peilstöcker, M. 2003. The Plain of Akko from the Beginning of the Early Bronze Age to the End of the Middle Bronze Age: A Historical Geography of the Plain of Akko from 3500–1500 BC: A Spatial Analysis. PhD. University of Tel-Aviv.

- Philip, G. 2003. The Early Bronze Age of the southern Levant: a landscape approach. Journal of Mediterranean Archaeology 16: 103–32. doi: 10.1558/jmea.v16i1.103

- Philip, G. and Bradbury, J. 2010. Pre-Classical activity in the basalt landscape of the Homs region, Syria: implications for the development of ‘sub-optimal’ zones in the Levant during the Chalcolithic–Early Bronze Age. Levant 42(2): 136–69. doi: 10.1179/175638010X12797237885659

- Portugali, J. and Gophna, R. 1993. Crisis, progress and urbanization: the transition from Early Bronze I to Early Bronze II in Palestine. Tel Aviv 20(2): 164–86. doi: 10.1179/tav.1993.1993.2.164

- Regev, J., Finkelstein, I., Adams, M. J. and Boaretto, E. 2014. Wiggle-matched 14C chronology of Early Bronze Megiddo and the synchronization of Egyptian and Levantine chronologies. Egypt and the Levant 24: 243–66.

- Regev, J., de Miroschedji, P., Greenberg, R., Braun, E., Greenhut, Z. and Boaretto, E. 2012. Chronology of the Early Bronze Age in the southern Levant: new analysis for a high chronology. Radiocarbon 54: 525–66. doi: 10.1017/S003382220004724X

- Regev, J., Paz, S. Greenberg, R. and Boaretto, E. 2019. Radiocarbon chronology of the EB I–II and II–III transitions at Tel Bet Yerah, and its implications for the nature of social change in the southern Levant. Levant 51: 54–75. doi: 10.1080/00758914.2020.1727238

- Renfrew, C. 1986. Introduction: peer polity interaction and socio-political change. In, Renfrew, C., Cherry, J. F., Audouze, F., Schlanger, N., Sherratt, A., Taylor, T. and Ashmore, W. (eds), Peer Polity Interaction and Socio-political Change: 1–18. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rotem, Y. 2012. The Early Bronze Age IB pottery from strata M-3 and M-2. In, Mazar, A. (ed.), Excavations at Tel Beth-Shean, Volume IV, The Early Bronze Age: 123–235. Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society.

- Rotem, Y. 2015. The Central Jordan Valley during the Early Bronze Age I and the Transition to Early Bronze Age II: Patterns and Processes in a Complex Village Society. PhD. University of Tel Aviv. (Hebrew, English Abstract).

- Rotem, Y., Iserlis, M., Höflmayer, F. and Rowan, Y. M. 2019. Tel Yaqush—an Early Bronze Age village in the Central Jordan Valley, Israel. Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research 381: 107–44. doi: 10.1086/703393

- Sabar, R. 2017. Eastern Upper Galilee during the Hellenistic, Roman and Byzantine Periods: Settlement History of an Ethnic Border Region. MA. The Hebrew University, Jerusalem (Hebrew, English Abstract).

- Shaked, I. 2016. Map of Metula (7). Archaeological Survey of Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority. Available at: https://survey.antiquities.org.il/#/MapSurvey/1115.

- Schwöbel, V. 1904. Die Verkehrswege und Ansiedlungen Galiläas in ihrer Abhängigkeit von den natürlichen Bedingungen. Zeitschrift des Deutschen Palästina-Vereins 27: 1–151.

- Sharon, I. and Zionit, G. 2011. Geographic information systems: introduction, methodology and description of basic coverages. In, Dagan, Y. (ed.), The Ramat Bet Shemesh Regional Project: Landscapes of Settlement: From the Paleolithic to the Ottoman Periods: 63–92. IAA Reports 47. Jerusalem: Israel Antiquities Authority, Jerusalem.

- Shelach-Lavi, G., Teng, M., Goldsmith, Y., Wachtel, I., Ovadia, A., Wan, W. and Marder, O. 2016. Human adaptation and socioeconomic change in northeast China: results of the Fuxin Regional Survey. Journal of Field Archaeology 41: 467–85. doi: 10.1080/00934690.2016.1194688

- Sneh, A. 2004. Nahariyya, Geological Map of Israel, 1:50000. Jerusalem: Geological Survey.

- Stepansky, Y. 1999. The Periphery of Hazor During the Bronze Age, Iron Age and the Persian Period: A Regional – Archaeological Study. MA. University of Tel Aviv (Hebrew with English abstract).

- Stepansky, Y. 2012. Map of Rosh Pinna (18). Archaeological Survey of Israel. Israel Antiquities Authority. Available at: http://www.antiquities.org.il/survey/new/default_en.aspx.

- Tadmor, M. and Prausnitz, M. W. 1958. Rosh Ha‘Niqra. ‘Atikot 2: 65–79 (Hebrew).

- Uziel, J. and Maeir, A. M. 2005. Scratching the surface at Gath: implications of the Tell es-Safi/Gath Surface Survey. Tel Aviv 32: 50–75. doi: 10.1179/tav.2005.2005.1.50

- Uziel, J. and Shai, I. 2010. The settlement history of Tel Burna: results of the surface survey. Tel Aviv: Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 37(2): 227–45. doi: 10.1179/033443510x12760074471062

- Wachtel, I. 2018a. The Upper Galilee in the Bronze and Iron Ages: Settlement Patterns, Economy and Society. PhD. The Hebrew University, Jerusalem (Hebrew, English Abstract).

- Wachtel, I. 2018b. Monumentality in early urbanism: an Early Bronze Age south Levantine monument in context. Asian Archaeology 1(1): 75–93. doi: 10.1007/s41826-018-0003-6

- Wachtel, I. In Press. Sixty years after Aharoni: the Iron I settlements in the Upper Galilee. In, Lipschits, O., Sergi, O. and Koch, I. (eds), From Nomadism to Monarchy: A Thirty-Year Retrospective. Mosaics: Studies on Ancient Israel. Pennsylvania and Tel Aviv: Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University and Penn State University Press.

- Wachtel, I. and Davidovich, U. 2021. Qedesh in the Galilee: the emergence of an Early Bronze Age Levantine megasite. Journal of Field Archaeology 46(4): 260–74. doi: 10.1080/00934690.2021.1901025

- Wachtel, I., Sabar, R. and Davidovich, U. 2017. Tell Gush Halav during the Bronze and Iron Ages. STRATA: Bulletin of the Anglo-Israel Archaeological Society 35: 115–34.

- Wilkinson, T. J., Philip, G., Bradbury, J., Dunford, R., Donoghue, D., Galiatsatos, N., Lawrence, D., Ricci, A. and Smith, S. L. 2014. Contextualizing early urbanization: settlement cores, early states and agro-pastoral strategies in the Fertile Crescent during the fourth and third millennia BC. Journal of World Prehistory 27: 43–109. doi: 10.1007/s10963-014-9072-2

- Yadin, Y., Aharoni, Y., Amiran, R., Dothan, T. and Dunayevsky, I. 1958. Hazor I: An Account of the First Season of Excavation 1955. Jerusalem: The Israel exploration society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Yadin, Y., Aharoni, Y., Amiran, R., Dothan, T., Dunayevsky, I. and Perrot, J. 1960. Hazor II: An Account of the Second Season of Excavation 1956. Jerusalem: The Israel exploration society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Yadin, Y., Aharoni, Y., Amiran, R., Dothan, T., Dothan, M., Dunayevsky, I. and Perrot, J. 1961. Hazor III–IV: An Account of the Third and Fourth Seasons of Excavation 1957–1958. Jerusalem: The Israel exploration society and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- Yasur-Landau, A., Cline, E. H. and Pierce, G. A. 2008. Middle Bronze Age settlement patterns in the Western Galilee, Israel. Journal of Field Archaeology 33(1): 59–83. doi: 10.1179/009346908791071330

- Zertal, A. 1993. Fortified enclosures of the Early Bronze Age in the Samaria region and the beginning of urbanization. Levant 25: 113–25. doi: 10.1179/lev.1993.25.1.113