Abstract

The object presented here was found in August 2018, in a layer of Crusader-period fill inside the cistern of the winery discovered at Miʿilyā – Castellum Regis. It is the first and only one of its type and style found to date. Given the object’s resemblance to a seal, it seems likely that it is, in some way, connected to the world of seals: that connection will be discussed, briefly, below. What follows aims to identify the object and its owner, and make suggestions regarding its use.

History of Miʿilyā during the Frankish period

The archaeological remains from Miʿilyā indicate that the site was settled from, at least, the Pre-Pottery Neolithic (Khamisy Citation2018: 919; Citation2023). Archaeological excavations carried out by the author and small-scale excavations by the Israel Antiquities Authority have unearthed almost continuous occupation from the Middle Bronze Age until the present day (Abu-‘Uqsa Citation2005; Khamisy Citation2022a; Porat Citation2009). The name appears for the first time in a Frankish document dated 28 January 1160 AD (Mayer Citation2010, 1: 460–2 no. 253; Röhricht Citation1893: 89 no. 341; RRR no. 640; Strehlke Citation1869: 2–3 no. 2). The history of Castellum Regis and the seigneury of Joscelin III have been studied in detail by several historians (Khamisy Citation2013: 13–14, n. 1). The first mention of the castle of Miʿilyā (Mhalia) appears, together with nine inhabited villages, in a royal grant made to John of Haifa in 1160 (Mayer Citation2010, 1: 460–62 no. 253; Röhricht Citation1893: 89 no. 341; RRR no. 640; Strehlke Citation1869: 2–3 no. 2). This document indicates that by that time it was already serving as an administrative centre in western Upper Galilee, administered directly by the king.

In 1179 it was mentioned, for the first time, by the name Castellum Regis, when Joscelin III, titular count of Edessa, bought vineyards and houses there (Mayer Citation2010, 2: 706–07 no. 413; Röhricht Citation1893: 156 no. 587; RRR no. 1041; Strehlke Citation1869: 11–12 no. 11). On 24 February 1182, Joscelin received the castle and its appurtenances from his nephew King Baldwin IV (Mayer Citation2010, 2: 730–33 no. 430; Röhricht Citation1893: 162–63 no. 614; RRR no. 1096; Strehlke Citation1869: 13–14 no. 14). Castellum Regis fell to Saladin in 1187 following the Battle of Ḥaṭṭīn (al-Iṣfahānī Citation1995, 13: 5845, 5914; trans Massé 1972: 37, 99; Khamisy Citation2013: 14–15 n. 5).

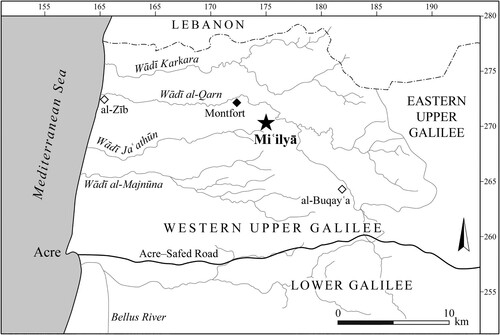

On 30/31 May 1220, Beatrice, Joscelin’s elder daughter, and her husband, Otto of Henneberg, sold Castellum Regis to the Teutonic Order (Mayer Citation2010, 3: 1041–52 no. 639; Röhricht Citation1893: 248 no. 934; RRR no. 1845; Strehlke Citation1869: 43–44 no. 53).Footnote1 By this time it is clear that the castle was an administrative centre for a much larger area, which Joscelin had attached to the original fief of Castellum Regis (for discussion see Frankel Citation1988: 262–70; Khamisy Citation2013; Mayer Citation1980). However, in two later documents, dating from April 1229, James of Mandalé, the son of Joscelin’s younger daughter Agnes, claimed a share with the Teutonic Order over his part of the inheritance, including Castellum Regis: the Teutonic Order paid him again for his properties (Mayer Citation2010, 3: 1124–27, 1356–57 nos 667, 778; Röhricht Citation1893: 263, 265 nos 1002, 1011; RRR no. 2108; Strehlke Citation1869: 51–53, 53–55 nos 63, 65, 66). In 1257 Castellum Regis was mentioned for the last time in the Frankish charters (Strehlke Citation1869: 91–94 no. 112). In 1283, Burchard of Mount Sion refers to it as a former Teutonic castle, which, at the time of his visit, was in the possession of the Saracens (Burchardus de Monte Sion Citation1978–Citation84, 4: 143; trans. Bartlett 2019: 40–41).Footnote2 It seems likely that the Mamlūks had occupied Miʿilyā and made use of its castle directly after its conquest by Baybars in May 1266. Accounts from this period clearly indicate the high regard in which the Mamlūks held the region of Miʿilyā. The continued existence of the castle and its use as the residence of a judge signifies the strategic importance it held for the Mamlūks; as it had for the Franks (for Frankish Miʿilyā see Ellenblum Citation1996; Citation1998: 41–53; Khamisy Citation2013; Citation2021; Pringle Citation1993–Citation2009, 2: 30–31. For the mention of the judge in 1372 text see, Lewis Citation1953: 480, 484). Its location in the centre of the western Upper Galilee () with a commanding view, in comparatively easy topography, near to copious springs and perennial streams, are direct indications as to its strategic importance. The settlement was abandoned during the early Ottoman period and re-established in the 1740s during the time of Ẓāhir al-ʿUmar (Khamisy Citation2018).

The archaeological context

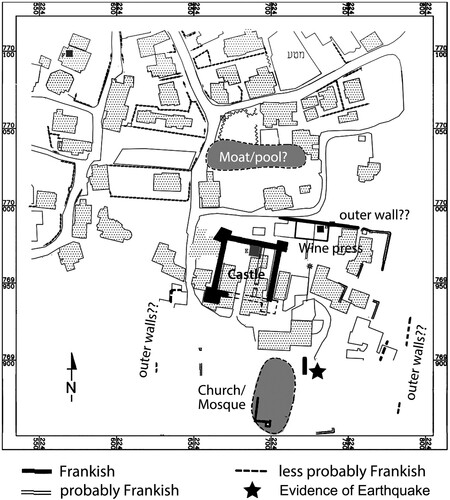

In July–October 2017, August 2018 and March 2019, archaeological excavations were conducted in Miʿilyā, 10–30 metres north-east of the castle, where a winery was uncovered () (Khamisy Citation2021: 205–16; Citation2022b). The archaeological context shows that the winery was established during the 12th century AD, most possibly during Baldwin III’s reign (Khamisy Citation2021: 208), but was expanded and perhaps returned to use after the agreement of 1229 between the Franks and the Ayyubids (Syon and Khamisy Citation2022). The winery contained an old cistern that the Franks converted into an underground room, mainly used for fermentation (Khamisy Citation2021).

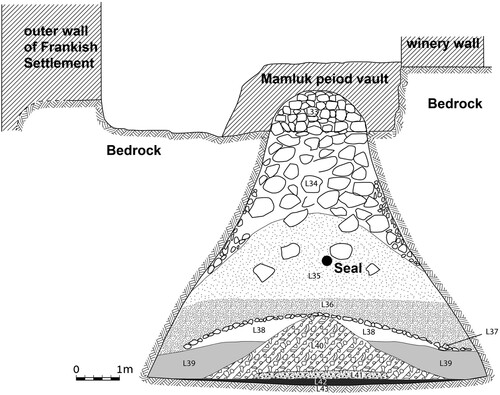

Two great piles of fill were found above the Crusader floor (locus 036): locus 035 which, according to the coins and pottery finds, can be securely dated to the 12th–early 13th century, and represents Frankish-period destruction; and locus 034 above it, which formed the systematic Mamlūk-period fill (), which, according to pottery finds and coins, is dated to the late 14th or early 15th century. The object under discussion was found in locus 035, along with hundreds of pottery sherds securely dated to the 12th and early 13th centuries, mainly glazed Beirut tableware, but also with a coin of John of Brienne, dated c.1219, and two cons of Amaury, dated 1163–1171, more than a metre below the Mamlūk fill of locus 034. This suggests that the dating of the object most probably corresponds closely with that of the layer in which it was found.

The object from Miʿilyā ()

The object is of lead, weighing 7.75 g, and is slightly cut in all sides, with a 26 mm diameter as found. If restored to a rounded shape it would reach almost 30 mm and 11 or 12 g in weight.

On the obverse there is an ecclesiastical figure, evidently a bishop, enthroned and wearing a mitre. He holds a spiralled staff in his left hand, while giving a sign of blessing with his right. Clearly the object belonged to an ecclesiastical figure, Frederick of La Roche, as will be demonstrated below. The inscription surrounding the figure, although well preserved in part, unfortunately lacks the name of the bishop; however, the preserved part, reading ‘ … VS ACONENSIS EPS’ (, 5), clearly indicates that the object belonged to one of the bishops of Acre.

On the reverse side of the object there is a patriarchal cross (, 5), surrounded by an inscription; now completely vanished, except for the faint trace of six letters in the top right and another in the bottom left. These letters most probably read: ‘hOC SIG … … I … ..’ ().

Although very similar to a seal, the object is probably not a seal, mainly because it is lacking a channel for a string to attach it to a document. It is possible that it is either: a sample showing how the design of a seal should be; or an attachment to a document, potentially via a ring holding the string. Maybe it should be identified as a ‘medallion’. Whatever the case, the object is unique and the first of its kind to be discovered. In view of its larger size and the close similarity of its design to that of seals, it seems unlikely that it was ever intended as a token (for the tokens, see Kool Citation2013). Among dozens of published tokens, the larger ones, found at Atlit, reach 25 mm in diameter and weigh 6.96 g (Kool Citation2013: 320). Such finds are very rare and, moreover, token design is completely different from the object discussed here.

As there is no doubt that the object from Miʿilyā belonged to one of the bishops of Acre, it seems logical to try and identify which bishop. It is possible that this can be done through comparison with surviving seals, and consideration of the archaeological and historical contexts in which the object was lost/found.

The bishops’ relationship with Miʿilyā and identification of the object

Being an important administrative centre during the Crusader period, located in the heart of a very fertile region near Acre, and containing a castle, it has been established that Miʿilyā was a town inhabited by Franks (Ellenblum Citation1996; Citation1998; Khamisy Citation2013; Citation2021). Among important figures who owned properties in Miʿilyā were the Archbishop of Nazareth and the Bishop of Acre. In document number 128 of Strehlke’s edition of the Teutonic Order’s Archive, there are references to the archbishop of Nazareth owning a house (or even more) and vineyards. In contrast, there are two mentions of a ‘bishop’, but without any indication of his see; however, a later mention from 1257 (see below) indicates that he was the Bishop of Acre. In transaction number 6 of document number 128, the Teutonic Order bought a vineyard near the vineyard of the bishop, and in transaction 12, the Order bought many properties from Henry, the representative of the bishop in Miʿilyā (Strehlke Citation1869: 120–21 no. 128. See also, Ellenblum Citation1996; Citation1998). Ellenblum has dated the first 21 transactions, which deal with Castellum Regis, to between 1220 and 1229 (Ellenblum Citation1996: 115–16).

During the settlement of a dispute between the Teutonic Order and Bishop Florence in 1257, the bishop asked the order to pay him taxes for very large areas in western Upper Galilee, and for the taxes to be transported to his house in Miʿilyā (Strehlke Citation1869: 91–94 no. 112). This is a very clear indication for the continuous use of the settlement as a prestigious administrative centre in the region of Acre. No doubt the bishop’s properties would have passed from one bishop to the next.

Florence was the last Bishop of Acre and served until 1263, three years before the fall of Miʿilyā. As mentioned above, the main context of the layer in which the object was found (locus 035) is dated to the 12th–early 13th century; this does not fit with the period during which Florence was bishop. A more likely candidate to identify as the owner of the object from Miʿilyā is Frederick, who served as bishop of Acre, possibly from 1148 AD and more certainly from 1153–1164 AD.

The seals of the bishops of Acre had a specific design, which makes their identification very simple. On the obverse there is always the figure of a bishop, standing or sitting, with a mitre on his head and holding a spiralled staff in his left hand, while raising his right hand in blessing. The figure is always surrounded by the name of the bishop followed by that of his office (Bishop of Acre). On the reverse there is always a two-armed patriarchal cross, or cross of Lorraine, surrounded by the inscription ‘+ HOC SIGNV(m) CRVCIS ERIT I(n) CELO’ (sometimes with minor changes).Footnote3 The patriarchal cross, on seals of bishops and archbishops, and appearing alone in the centre of the seal, appeared only and systematically on the seals of the bishops of Acre. The same is true of the inscription surrounding the cross. These indications help to identify seals of the bishops of Acre, even when the bishop’s name is missing.

The names of 15 Latin bishops of Acre are known from the 12th and 13th centuries, seven of whom have left seals, it is clear that one of them, Frederick of La Roche, was the owner of the object under study. The inscription around the figure on his seal is ‘+ FREDERICVS ACONENSIS EPS’, and around the cross is ‘hOC SIGNV CRVCIS ERIT IN CELo’, which fully appeared in the photo of the seal presented by Berlière (Citation1908). However, all scholars, including Berlière, misconstrued the word ‘CRVCIS’ (Berlière Citation1906; Citation1908: 68; de Sandoli Citation1974: 322 no. 427; Schlumberger et al. Citation1943: 102 no. 78). Bishop Frederick of La Roche’s seal was the first to carry the new design, a design that was to become, apart from Florence, the characteristic seal design of the bishops of Acre. Frederick’s seal, however, is the only one to end with the word ‘EPS’, instead of ‘EPI’ which appears on all the other seals (see Supplemental Material). This corresponds very well with the object under study (). In addition, his name on the seal is quite long ‘FREDERICVS’ and is the only name to end with the two letters ‘VS’; exactly like the object under study and in the same location on the seal. Such a long name would easily fill half the circle of the seal, which is the case here. In addition, Frederick’s seal has a diameter of 30 mm, almost the same as the restored diameter of the newly discovered object (see above).

Summary

The object, found in the winery of Miʿilyā/Castellum Regis, is the only one of its type uncovered to date. It certainly belonged to Frederick of La Roche, bishop of Acre between 1148/53 until 1164. The object is made of lead and similar to a seal, but, unlike a seal, has no string channel. It is possible that it was attached to a document using a hanging ring, and, if this were the case, it would be unique amongst seals.

The evidence, however, suggests that the object is not a seal, although, given the similarities, it is probably related to the world of seals. It is possible that the object was held as a sample/copy for the design of the seals of the bishop to whom it relates, and, accordingly, several seals were produced and used by the bishop and/or his representative in Miʿilyā when issuing or confirming documents about different activities, inter alia, collecting taxes. Another option is that the object was a medallion, perhaps held by the bishop’s representative to confirm that he was working under the bishop.

How then did the object arrive in its place of discovery; an authentic and tragic layer of destruction. The answer could be that the object was held here when the destruction occurred; that the building and the winery were owned by the bishop. As the 1257 document reveals, taxes from the Teutonic Order were sent to the bishop’s house in Miʿilyā, it is likely that taxes from other inhabitants in the region were sent to the same house. The levelled floor in the cistern (locus 036) included early 12th-century pottery and two coins of Baldwin III, while the destruction context containing the object (Locus 035), included, inter alia, two coins of Amaury (baskets 123b–c) and one coin of John of Breinne (1219) (basket 123a): suggesting that the construction date of the winery is very probably during the reign of Baldwin III. The object’s date fits very well with the history of the place and the settlement. Even if the destruction occurred in the early 13th century, for example during the 1202 earthquake, or for any other reason, this does not eliminate the possibility that an earlier object was kept in the building by the owner.

Finally, given the absence of documents relating to the activities of the Bishop of Acre in the fief of Castellum Regis during the 12th century, this object, along with the construction of nearby Castellum Regis, provides some of the only clues regarding potential activities during the second-half of the 12th century. Being found in the area of the winery may indicate that the house of the bishop was located in that area, or even, that the bishop owned the winery: churches were among the main and pioneering bodies to lead and develop wine production during the Frankish period (Khamisy Citation2021: 203; Prawer Citation1980: 132–35).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (38.2 KB)Acknowledgments

My great thanks are to the Zinman Institute of Archaeology for cleaning and preserving all the metal finds from the excavations, including the object. I also would like to thank Mr Shai Halevi (Israel Antiquities Authority – Museum of Israel) for photographing the seal using the Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI), which makes the designs and inscriptions on the seal much clearer, and to my friend Mr Shihab Farran for working on figures 4 and 5. Finally I would like to address my great thanks to professor Denys Pringle (Cardiff University) for his excellent comments. My great thanks are also extended to Mrs Salma Assaf and her family, the owners of the property in which the winery is located. Without their passion and amazing interest in antiquities, all the huge excavation and preservation project of the winery would not be done in the first place.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplemental material

Supplemental material for this article can be accessed here: https://doi.org/10.1080/00758914.2024.2355794.

Notes

1 This was confirmed in January 1226 (Mayer Citation2010, 3: 1079–93 no. 654; RRR no. 2024; Strehlke Citation1869: 47–8 no. 58).

2 For other documents and a short discussion of the mentions from the Mamlūk period see Khamisy (Citation2013: 15–16 and nn. 11–17).

3 These words come from the responses sung during the Offices for the feasts of the Finding of the Cross (Inventio Crucis) and Raising of the Cross (Exaltatio Crucis): Hoc signum crucis erit in coelo, cum Dominus ad judicandum venerit; tunc manifesta erunt abscondita cordis nostri, alleluia, alleluia. V/ Cum sederint Filius hominis in sede majestatis suae, et coeperit judicare saeculum per ignem (Hesbert Citation1970: 213 no. 6845).

References

- Abu-‘Uqsa, H. 2005. Mi’ilya. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 117. Available at: Volume 117 Year 2005 Mi‘ilya (hadashot-esi.org.il).

- Berlière, U. 1906. Frédéric de Laroche, évêque d’Acre et archevêque de Tyr. Envoi de reliques à l’abbaye de Florennes (1153–1164). Revue Bénédictine 23: 501–13.

- Berlière, U. 1908. Frédéric de Laroche, évêque d’Acre et archevêque de Tyr. Envoi de reliques à l’abbaye de Florennes (1153–1161). Annales del’Institut archéologique de Luxembourg 43: 67–79.

- Burchardus de Monte Sion, 1978–84. Descriptio Terrae Sanctae, in de Sandoli, S (ed.). Itinera Hierosolymitana Crucesignatorum (saec. XII–XIII), Studium Biblicum Franciscanum, Collectio Maior, 24. 4 Vols. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press. [Or Burchard of Mount Sion, (2019). In, Bartlett, J. R. (ed. and trans.) Descriptio Terrae Sanctae, 25 (4.1), Oxford Medieval Texts, Oxford, 40–41].

- Ellenblum, R. 1996. Colonization activities in the Frankish East: the example of Castellum Regis (Mi’ilya). The English Historical Review 111: 104–22.

- Ellenblum, R. 1998. Frankish Rural Settlement in the Latin Kingdom of Jerusalem. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Frankel, R. 1988. Topographical notes on the territory of Acre in the Crusader period. Israel Exploration Journal 38: 249–72.

- Hesbert, R.-J. (ed.) 1970. Corpus Antiphonalius Officii, 4: Responsa, versus, hymni et varia, Rerum Ecclesiasticarum Documenta, series maior, Fontes 10. Rome: Herder.

- al-Iṣfahānī ʿImād al-Dīn. 1995. al-Fatḥ al-qussī fī al-fatḥ al-qudsī, in Zakkār, S. (ed.), al-Mawsūʿa al-shāmiyya fī taʾrīkh al-ḥurūb al-ṣalībiyya. 40 Vols. Dār al-Fikir, Damascus, Vol. 13. In Massé, H. (trans.) (1972) Conquête de la Syrie et de la Palestine par Saladin. Documents relatifs à l’histoire des croisades 10. Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner: Paris.

- Khamisy, R. G. 2013. The history and architectural design of Castellum Regis and some other finds in the Village of Miʿilya. Crusades 12: 13–51.

- Khamisy, R. G. 2018. The ʿAssāf family of Miʿilya: an example of a Greek Catholic family in the Western Upper Galilee, eighteenth–twenty-first centuries. Middle Eastern Studies 54(6): 917–35.

- Khamisy, R. G. 2021. Frankish viticulture, wine-presses and wine production in the Levant: new evidence from Castellum Regis (Miʿilyā). Palestine Exploration Quarterly 153(3): 191–221.

- Khamisy, R. G. 2022a. Mi’ilya (A). Hadashot Arkheologiyot 134. Available at: Volume 134 Year 2022 Mi‘ilya (A) (hadashot-esi.org.il).

- Khamisy, R. G. 2022b. Mi’ilya (B). Hadashot Arkheologiyot 134. Available at: Volume 134 Year 2022 Mi‘ilya (B) (hadashot-esi.org.il).

- Khamisy, R. G, 2023. Western Upper Galilee, Survey. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 135. Available at: Volume 135 Year 2023 Western Upper Galilee, Survey (hadashot-esi.org.il).

- Kool, R. 2013. Lead token money in the Kingdom of Jerusalem. The Numismatic Chronical 173: 293–339, plates 49–54.

- Lewis, B. 1953. An Arabic account of the Province of Safed. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies 15: 477–88.

- Mayer, H. E. 1980. Die Seigneurie de Joscelin und der Deutsche Orden. In, Fleckenstein, J. and Manfred, H. (eds), Die geistlichen Ritterorden Europas, Vorträge und Forschungen 26: 171–216. Sigmaringen: Jan Thorbecke Verlag KG.

- Mayer, H. E. 2010. Die Urkunden der Lateinischen Könige von Jerusalem. 4 Vols. Hannover: Hahnsche Buchhandlung.

- Porat, L. 2009. Mi’ilya, the Church Square. Hadashot Arkheologiyot 121. Available at: Volume 121 Year 2009 Mi‘ilya, the Church Square (hadashot-esi.org.il).

- Prawer, J. 1980. Crusader Institutions. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Pringle, D. 1993–2009. The Churches of the Crusader Kingdom of Jerusalem. 4 Vols. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Röhricht, R. (ed.) 1893. Regesta Regni Hierosolymitani (MXCVII–MCCXCI). Innsbruck: Libraria Academica Wagneriana.

- Revised Regesta Regni Hierosolymitani (RRR). Available at: http://crusades-regesta.com.

- de Sandoli, S. 1974. Corpus Inscriptionum Crucesignatorum Terrae Sanctae (1099–1291), Testo, traduzione e annotazioni. Jerusalem: Franciscan Printing Press.

- Schlumberger, G., Chalandon, F. and A. Blanchet. 1943. Sigillographie de l’Orient latin. Bibliothèque archéologique et historique 37. Paris: Librairie Orientaliste Paul Geuthner.

- Syon, D. and Khamisy, R. G. 2022. A medieval Austrian penny from Israel. Numismatische Zeitschrift 127: 475–76.

- Strehlke, E. (ed.) 1869. Tabulae Ordinis Theutonici. Berlin: Apud Weidmannos.