Abstract

THE GREAT HALL complex represents one of the most distinctive and evocative expressions of the Anglo-Saxon settlement record, and is widely cited as a metaphor for the emergence of kingship in early medieval England. Yet interpretation of these sites remains underdeveloped and heavily weighted towards the excavated findings from the well-known site of Yeavering in Northumberland. Inspired by the results of recent excavations at Lyminge, Kent, this paper undertakes a detailed comparative interrogation of three great hall complexes in Kent, and exploits this new regional perspective to advance our understanding of the agency and embodied meanings of these settlements as ‘theatres of power’. Explored through the thematic prisms of place, social memory and monumental hybridity, this examination leads to a new appreciation of the involvement of great hall sites in the genealogical strategies of 7th-century royal dynasties and a fresh perspective on how this remarkable, yet short-lived, monumental idiom was adapted to harness the symbolic capital of Romanitas.

INTRODUCTION

Defined by monumental timber halls arranged in highly formalised spatial configurations, the class of settlement known as the ‘great hall complex’ has occupied a prominent position in Anglo-Saxon studies since the iconic excavations at Yeavering in the 1950s.Footnote2 In the intervening years a great deal of illustrative weight has been placed on the shoulders of this rare category of site, crystallising its status as a defining metaphor for the emergence of kingship and elite authority in Anglo-Saxon England. Regularly cited across a wide spectrum of historical, literary and archaeological studies, the phenomenon has proved to be remarkably malleable and adaptable, in the process accumulating a series of meanings and associations drawn from different disciplinary traditions. Through comparison with literary sources, pre-eminently Beowulf’s vivid descriptions of Heorot, it has become conceptually bound with the rituals and preoccupations of early medieval kings and their mobile warbands — hospitality, formalised gift-exchange, and ritualised feastingFootnote3 — and, at a deeper level, with the idea of the hall as a unifying ideological construct across early medieval Germanic societies.Footnote4 Meanwhile, correlation with historical labels pertaining to places of royal authority transmitted through Bede and other textual sources has encouraged the phenomenon to be closely identified with the royal vill/tun, and its wider place in the extractive mechanisms of ‘extensive lordship’, including royal iteration and the consumption of royal tribute (OE ‘feorm’).Footnote5

In light of the powerful influence that this category of site has, and continues to exercise over Anglo-Saxon scholarship, it is important to emphasise that there are significant weaknesses in our understanding of the great hall complex as an archaeological phenomenon. Sites in this category first received comparative attention in the 1980s and 1990s as part of successive attempts to characterise and periodise the architectural forms brought to light by a rapidly expanding corpus of excavated Anglo-Saxon rural settlements.Footnote6 These examinations demonstrated that sites like Yeavering, while exceptional in terms of the scale and formality of their architecture, formed part of a much more extensive Anglo-Saxon ‘building tradition’ which had seemingly been adapted to create a distinctive class of elite residence current during the later 6th and 7th centuries ad. While these studies provided an important foundation for further research, they projected an over-generalised image of these sites and offered little in the way of interpretation beyond brief comments on their social and ethnic significance, the latter being subsumed within a broader debate concerning the cultural origins of the Anglo-Saxon house.Footnote7

Subsequent studies have begun to encourage deeper conceptual engagement with these sites, not simply as the social apex of broader Anglo-Saxon building tradition, but as ‘theatres of power’ — highly manipulated settings which provided emergent elites with an extravagant new outlet, or stage, for enacting the rituals of rulership and political authority.Footnote8 Under the influence of theoretical and socially informed perspectives, emphasis has shifted towards understanding the social agency and lived experience of these sites and decoding the complex symbolic messages which they were designed to convey as settings where sacral and ideological claims to political authority were actively channelled and animated. This shift has brought previously neglected dimensions of the phenomenon to the forefront of the research agenda — prehistoric monument reuse, the ritualised configuration of space, special deposits, and the strategic exploitation of wider landscape settingsFootnote9 — while encouraging comparisons with related expressions of early medieval hall-culture from other parts of the early medieval North Sea world, in particular a burgeoning of central-place complexes from Scandinavia.Footnote10

While these studies have placed the field on a more sophisticated footing, much of the discussion has been framed around the site of Yeavering, which has had a disproportionate influence on the way in which great hall complexes have been conceptualised. This is partly a reflection of the deeply provocative and arresting qualities of Yeavering itself, laid bare in stunning detail by Hope-Taylor’s excavations and subsequent monograph.Footnote11 But it is also a product of the fact that the majority of the great hall complexes recognised today represent poorly understood cropmark sites susceptible, at most, to fairly superficial examinations of plan form.Footnote12 This has ultimately deflected attention back on to Yeavering and, to a lesser extent, Cowdery’s Down (Hampshire) as ‘type-sites’, while at the same time entrenching the homogenised view of later 6th-/7th-century elite residences portrayed by early syntheses of Anglo-Saxon rural settlements.

The simplistic application of monolithic categories of the ‘great hall complex’ type has been recognised as one of the key obstacles standing in the way of more complex and socially nuanced understandings of the medieval past. In a critique that could be applied to any number of sub-fields of medieval archaeology, but which is particularly pertinent to the current context, Kate Giles has recently observed,

buildings must be understood as the result of intimate, local negotiations and interpreted in the context, not of global, national, cultural models or ‘types’, but rather the lived lives of men and women inhabiting particular buildings, at particular times [and places] in the past.Footnote13

The topic of Anglo-Saxon hall complexes is ripe for re-evaluation of this kind. Recent years have seen a significant growth in the corpus of sites and relevant datasets encapsulating systematic excavation of hall arrays on a scale comparable to Yeavering and Cowdery’s Down (Lyminge, Kent),Footnote18 targeted investigation aimed at improving understanding of cropmark sites (Sutton Courtenay, Oxfordshire),Footnote19 detailed survey and reconnaissance work offering a landscape-scale perspective on the evolution of documented royal centres (Rendlesham, Suffolk),Footnote20 and the recognition of new sites through the re-evaluation of old and neglected datasets (Benson, Oxfordshire).Footnote21 The point has been reached where it is possible to delineate patterns of similarity and difference across multiple parameters of the great hall complex tradition — spatial and monumental properties, landscape settings, life histories etc — both as a prerequisite for attaining a more holistic and nuanced appreciation of the phenomenon itself, and as a spur for informing a wider set of intersecting debates concerning the changing material expression of kingship, power and social complexity in early medieval England.Footnote22

This article develops this research agenda by opening up a new regional perspective on great hall complex phenomenon grounded in the rich context of Anglo-Saxon Kent. It has its origins in a decade-long programme of excavation and research directed by the author at Lyminge, where the remains of a 7th-century great hall complex were systematically excavated between 2012 and 2015. While ruminating on these results I became convinced that Anglo-Saxon discoveries made during the urban redevelopment of Dover in the 1970s offered crucial parallels and context for the Lyminge halls, in spite of being published, in the most definitive of terms, as the remains of an Anglo-Saxon monastery.Footnote23 This realisation was soon followed by reports of the unearthing of yet another Kentish great hall site at Eynsford, in the west of the county. Within the space of a few years Kent — a region long maligned for its dearth of Anglo-Saxon settlement archaeology — had emerged with one of the richest excavated datasets pertaining to the theme of pre-Viking royal residence in the country. Brought together here for detailed comparative examination, this paper harnesses the collective interpretative potential offered by the three sites by combining fine-grained interrogation of salient archaeological and architectural details, with theoretical approaches to access deeper realms of significance and meaning. In pursuing this agenda, advantage is taken of the foundational importance of Kentish historical sources for the study of Anglo-Saxon kingship: sources that provide an unusually detailed, multi-faceted portrayal of the ascendency and hegemony of the native royal bloodline, the Oiscingas dynasty.Footnote24

The paper begins by appraising the contextual and archaeological evidence for the three Kentish sites, commencing with the most fully understood — Lyminge — to establish the parameters for subsequent comparison. This prompts a systematic re-evaluation of the published site sequence for Dover, bringing to the fore a number of shared architectural tendencies with Lyminge, permitting its identity as a 7th-century great hall complex to be appreciated fully for the first time. The second part of the article draws out comparative strands from the analysis as a basis for building new and enriched interpretations oriented by and through the local Kentish context. Drawing upon recent archaeological approaches to social memory, it is argued that these settlements were heavily implicated in the genealogical strategies of royal dynasties and that this role is directly manifested in their temporal rhythms and life histories. Meaning is also sought in the distinctive repertoire of architectural features and tendencies shared by the Kentish halls themselves. The argument is advanced that these constructions deserve to be regarded as hybrid monuments which fused traditional elements of the Anglo-Saxon hall with classicising idioms drawn from the architectural programme of the Augustinian mission, most strikingly, sophisticated opus signinum flooring of a type more familiarly associated with pre-Viking churches. In presenting evidence that both churches and elite residences in Anglo-Saxon Kent drew upon the symbolic capital of Romanitas, this study challenges long-standing dichotomies in early medieval scholarship that have emphasised distinctions between secular halls and ecclesiastical buildings on the one hand, and between timber and masonry architectural traditions on the other.

A COMPARATIVE SURVEY OF GREAT HALL COMPLEXES IN KENT

lyminge

Background context

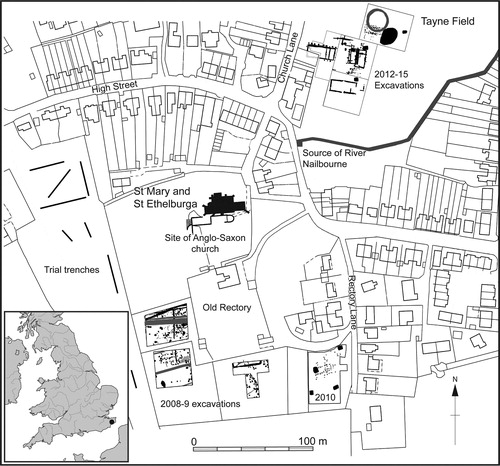

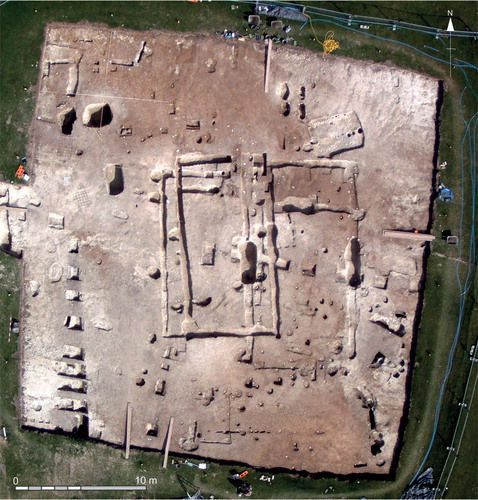

The site of the great hall complex was discovered during a major scheme of research excavation directed by the author under the auspices of the University of Reading, 2008–15. The initial target of this research was a pre-Viking monastic foundation previously investigated by the antiquarian-cleric, Canon Jenkins, who uncovered the remains of an Anglo-Saxon masonry church of ‘Kentish’ type within the limits of the churchyard.Footnote25 While early results were very much consistent with this identification, subsequent discoveries demonstrated that archaeological strata relating to an antecedent Anglo-Saxon settlement of the 5th–7th centuries ad lay preserved beneath the core of the modern-day village. Thereafter, the emphasis of the research was redirected towards understanding the character of this precursor settlement and its relationship to the monastic focus. This aim was advanced in a 3-year campaign of excavation sited within a large recreational space within the centre of the village known as ‘Tayne Field’, which brought to light the previously unattested great hall complex as part of a rich, multi-period palimpsest of past occupation and activity ().

fig 1 Location of excavations in relation to the modern-day topography of Lyminge. Illustration by Lyminge Archaeological Project. Base map © Crown Copyright/database right 2016. An Ordnance Survey/Edina Service.

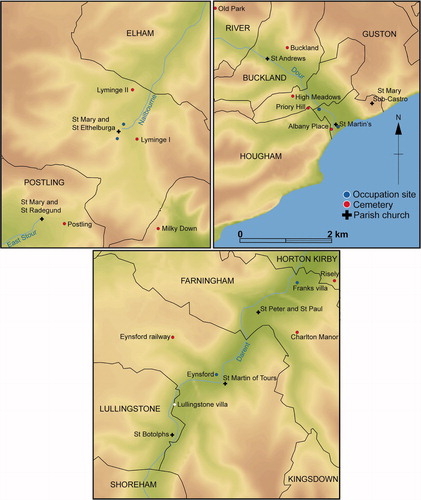

Lyminge is located 6.75 km inland of the south coast of Kent at the head of the valley of the River Nailbourne (Little Stour), — one of the most important natural corridors through the North Downs in south-eastern Kent. As well as enjoying a commanding position within this major N/S communication artery, Lyminge sits at the hub of a complex arterial network of downland routeways, those to the west offering convenient access to the Roman road of Stone Street, which connected the shore fort of Portus Lemanis with the civitas capital of Canterbury (). While somewhat overshadowed by adjacent valley ridges and promontories, the site of the great hall complex — directly overlooking the source of the River Nailbourne and surmounting a low projecting spur encircled by its headwater — offers commanding views of approaches through the Nailbourne valley, as well as direct sightlines to nearby early medieval cemeteries.Footnote26

fig 2 Topographic settings of Lyminge, Dover and Eynsford. Illustration by Matthew Austin. Base map © Crown Copyright/database right 2016. An Ordnance Survey/Edina Service.

Although not without ambiguities, the early historical documentation for Lyminge is considerably stronger than that for the other pair of sites examined in this article.Footnote27 It first enters the historical record in ad 689 in connection with a charter of King Oswine granting land formerly appurtenant to the ‘cors’ (royal vill) of Lyminge to St Augustine’s Abbey, Canterbury.Footnote28 Explicit mention of a monastic presence at Lyminge appears a decade or so later when King Wihtred granted an estate to the church (basilica) of St Mary, identifiable as a member of a closely knit family of nunneries established by the Kentish royal dynasty in the second half of the 7th century.Footnote29 The monastic endowment was enriched considerably over the course of the 8th century with a succession of detached estates located in Romney Marsh and the Weald, a period when Lyminge and its sister establishment of Minster-in-Thanet were, for a time, placed under the rule of a single abbess serving as a proxy of the Mercian royal family.Footnote30 References become much sparser in the charter record thereafter, but enough is known to indicate that a monastic community endured at Lyminge into the middle of the 9th century, before its estates and relics were finally, in a fate befalling Kent’s formerly independent royal minsters, absorbed by Canterbury.Footnote31

Lyminge’s documented status as a royal vill in the 7th century clearly derived from its long-standing significance as a regional administrative centre which, on the evidence of the place name itself and the information provided by two pre-Christian cemeteries, extended at least as far back as the 6th century.Footnote32 During this period it is appropriate to view Lyminge as operating as the head settlement of an extensive territory, or regio, broadly commensurate with the lathe of lemenwara documented in later historical sources.Footnote33

Occupation sequence

As the most comprehensive investigation of a pre-Viking royal centre in Kent, the recent excavations at Lyminge have generated a measure against which other local sites of similar status can be compared and evaluated. This capacity is underpinned by a chronologically refined occupation sequence (calibrated by an abundance of diagnostic artefact types and a suite of almost forty radiocarbon dates), allowing Lyminge’s evolution as an early medieval ‘central place’ to be charted with unusual precision over the longue durée. A distillation of this narrative now follows to inform subsequent discussion.Footnote34

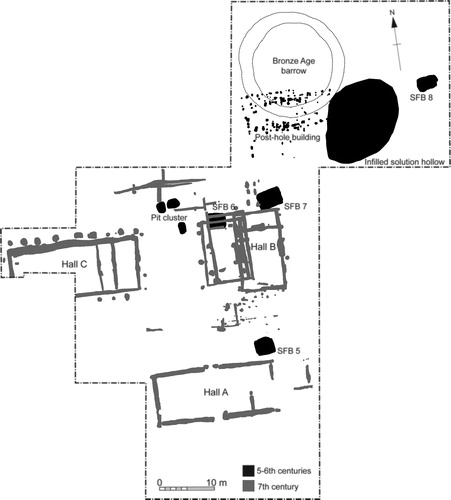

The earliest phase of Anglo-Saxon occupation identified at Lyminge, dating to the 5th–6th centuries ad, appears to have been confined to gently sloping terrain bisected by the source and headwater of the River Nailbourne (). The discovery of contemporary habitation features in a number of separate locales within the village, endorses the view that this early settlement covered a sizeable area, although not necessarily as a continuous swathe. On the evidence of the comparative intensity of occupation and a number of distinctive characteristics, the low plateau subsequently occupied by the great hall complex seems to have constituted the ancestral focus of early Anglo-Saxon Lyminge.

This setting was distinguished by a striking juxtaposition of natural and prehistoric monumental features — a Bronze-Age barrow positioned beside a pre-existing natural solution hollow, or ‘doline’ — which very likely structured the development of the Anglo-Saxon settlement (). The site of the former was appropriated by an E/W rectangular timber building of post-hole construction which displayed an unusually complex constructional history and multiple foundation deposits hinting at a potential cultic significance. The neighbouring solution hollow was exploited variously throughout the life of the early settlement, including as a source of clay, a setting for metalworking and related high-temperature crafts, and intermittently as a receptacle for the disposal of large quantities of domestic midden material. Completing the settlement focus were four sunken-featured buildings, widely disposed across the Tayne Field plateau, and a spatially defined cluster of large pits cut with a level of care and precision, suggesting that their original purpose was connected with the storage of perishable food renders.

fig 3 Plan of Tayne Field excavations showing features relating to the two main phases of Anglo-Saxon occupation. Illustration by Lyminge Archaeological Project.

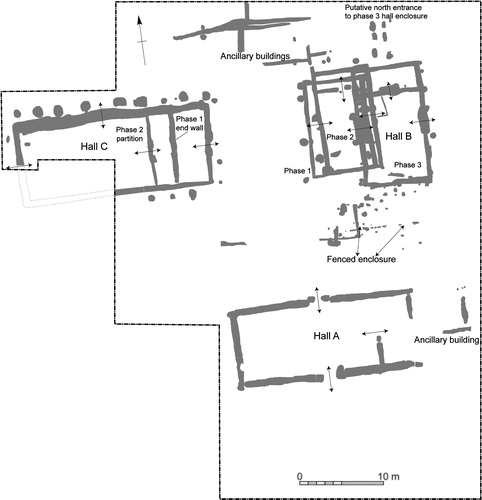

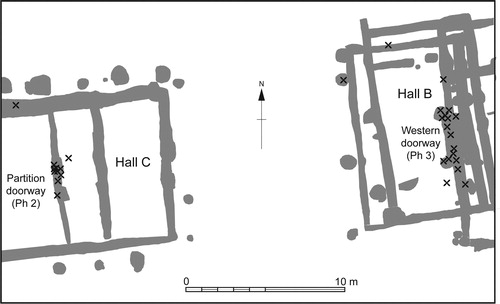

The great hall complex was constructed over a portion of the ancestral focus just described, in the process truncating a number of the sunken-featured buildings (). Radiocarbon and associative dating places the currency of the great hall complex firmly within the 7th century, and there is no indication of a hiatus between it and the earlier phase of occupation.Footnote35 In its fully developed form, the complex comprised three substantial halls with single annexes configured around a central open ‘courtyard’ (). The two halls forming the southern and western ranges of the courtyard (Halls A and C), both orientated on an E/W axis, were built on a larger scale than the hall perpendicularly aligned to the east (Hall B), the former exhibiting lengths in excess of 20 m and the latter a maximum length of around 15 m. There is good evidence that the complex was constructed to a precise and highly formalised spatial template. Firstly, it displays signs of the ‘ritual symmetry’ seen at other great hall complex sites,Footnote36 here clearly manifested in the intersection of doorways through Halls B and C (). Secondly, Lyminge has been shown to constitute a very early deployment of a standardised form of grid-planning which grew to prominence over the 8th–9th centuries in the spatial articulation of monasteries and rural settlements serving as monastic dependencies.Footnote37 As we shall come to see, this detail endorses the view that royal accommodation in 7th-century Kent evolved in close dialogue with the architectural programme of the Augustinian mission.

fig 4 Plan of the 7th-century great hall complex; arrows mark the position of entrances. Illustration by Lyminge Archaeological Project.

Constructed in the ‘post-in-trench’ technique, the halls at Lyminge display many of the constructional traits associated with the great hall tradition: rectangular timber wall posts (baulks) set in different configurations, wattle-and-daub wall panelling; the use of exterior raking posts to counteract the thrust of the roof; and diametrically opposed entrances positioned centrally within the long, and in the case of Hall C, both long and short walls ().Footnote38 Another idiom shared by Lyminge is the tendency for halls to be successively rebuilt on the same or overlapping footprints, as particularly demonstrated by Halls B and C, which each passed through three iterations, in the latter case accompanied by a change of constructional technique (). While much of this detail is familiar from previously excavated sites, the Lyminge halls also present evidence for more unusual and idiosyncratic features, most distinctive being the deployment of opus signinum flooring, detailed consideration of which is reserved for a comparative evaluation of parallel evidence from Dover.

fig 5 A view of the western doorway of Hall B (Phase 3) showing structural detail at the base of the massive retaining pit. The rectangular planks of the two door posts are clearly visible in the configuration of stone packing material. Vertical scale: 1 m. Photograph © Lyminge Archaeological Project.

fig 6 Vertical view of Hall B and its three constituent phases. Photograph by William Laing. © Lyminge Archaeological Project.

The long sequence of early medieval occupation which unfolded on the Tayne Field plateau came to an abrupt end when the hall complex was taken out of commission, an event which is unlikely to have occurred much later than ad 700 on the parameters of the available dating evidence. Without a thorough reappraisal of the remains brought to light by Canon Jenkins in the churchyard (located 180 m south-west), it is impossible to know whether there was a chronological overlap between the royal complex sited on Tayne Field and the Christian cult focus which first enters clear historical light as a royal nunnery at the turn of the 7th century.Footnote39 What can be said with certainty, however, is that within a relatively short period of time the latter had superseded the former as the monumental core and gravitational focus of the settlement: the great hall complex thus sits at the cusp of a decisive transformation in Lyminge’s monumental trajectory as a theatre of royal power.Footnote40

dover

Background context

The unearthing and excavation in the 1970s of a major sequence of post-Roman occupation within Dover has not received the attention that it deserves in Anglo-Saxon settlement studies. As we shall come to see, the reason for this neglect largely resides in deficiencies with the final publication — the third in a series of reports based on excavations by the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit in and around the Classis Britannica fort of Dubris and its late Roman-period successor.Footnote41 This should not detract from the achievements of what was, by any estimation, a vitally important series of archaeological interventions. As the report’s author makes clear, the circumstances surrounding the excavations could not have been less propitious: as was characteristic of the pioneering stages of ‘rescue archaeology’, funding was very scarce and the work had to be completed in the face of highly unsympathetic contractors and civic authorities. That such important, yet comparatively ephemeral, remains were recognised and recorded for posterity in such unfavourable conditions is testament to the persistence, fortitude and, most fundamentally, skill, of Brian Philp and his excavation team.

As made explicit in the report’s introduction, the ensuing programme of post-excavation analysis was self-financed and completed in-house by Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit volunteers. Qualitatively, The Discovery and Excavation of Anglo-Saxon Dover thus falls a long way short of most modern excavation monographs, most conspicuously in its lack of consideration of environmental remains, including animal bones, and the absence of a synthetic appraisal of the portable material culture. While some of these weaknesses can be excused as a product of various constraints both during and after excavation, it is more difficult to forgive the author’s uncritical approach to interpretation which relies heavily upon speculative inference to portray the site as a pre-Viking monastery. Given how much of this argument must be taken on trust it is impossible to recover the real meaning and significance of the underlying results without systematically dismantling the report’s interpretative edifice. Before doing so brief consideration needs to be given to the topographic setting and historical background of the site.

Dover is located 16 km east of Lyminge on the western edge of the now silted-up estuary of the River Dour where it cuts a steep-sided valley through chalk expanse of the North Downs. Offering the shortest sea crossing from England to the Continent, this natural harbour was of pre-eminent strategic importance (). The late Roman-period shore fort which provided the setting for the Anglo-Saxon hall complex was itself constructed over an earlier sequence of Roman buildings located within what had originally been the civilian focus (vicus) of the Classis Britannica fort abandoned in about ad 208.Footnote42 Most notable of these was an opulent 3rd-century mansio known as the ‘Roman Painted House’, comprising a two-storey range situated within a more extensive complex of masonry buildings.Footnote43

Several 5th-/7th-century sites are known from the town and its wider environs, according with the picture that the area of the lower reaches of the Dour valley ‘was quite extensively settled during the early Anglo-Saxon period’ ().Footnote44 Within the urban limits of Dover itself, the slopes of Priory Hill and Durham Hill provided prominent settings for two inhumation cemeteries. The former of these is likely to be twinned with a second occupational focus identified in the valley bottom on the west bank of the Dour, some 500 m north of the Roman shore fort.Footnote45

While Dover is more poorly documented in pre-Conquest sources than Lyminge, available glimpses indicate that it shared kindred status as one of the early minsters of Kent, similarly founded under royal aegis, although somewhat later, by King Wihtred at the turn of the 7th century.Footnote46 Strong royal connections are, of course, to be expected given Dover’s major strategic importance as a port, but this role only enters clear historical light in the 11th century when, as head of the confederation of Cinque Ports, its harbour was commandeered as a base for the royal fleet.Footnote47 The establishment of a mint during the reign of King Æthelstan (ad 924–39) nevertheless indicates that Dover was serving as a centre of royal administration by at least the middle of the 10th century, complementing its strategic role as a late-Saxon burgh and bulwark against seaborne Viking raiding.Footnote48

The published occupation sequence

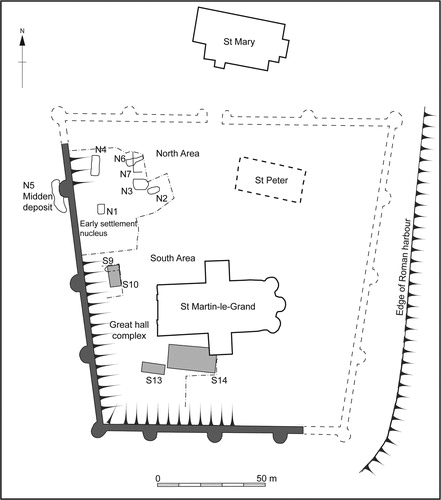

Philp divides the Anglo-Saxon occupation sequence identified within the south-western sector of the late Roman-period shore fort into two chronologically consecutive phases which he terms ‘early Saxon’ and ‘late-Saxon’, accorded date ranges of 6th–8th centuries and 9th–11th centuries ad respectively ().Footnote49 Activity attributed to the ‘early Saxon’ phase was mainly concentrated in what the report refers to as the ‘North Area’, defined on the west by the perimeter wall of the late Roman-period shore fort and the underlying structures associated with the ‘Roman Painted House’, and to the south by the remains of a substantial 2nd-century bath-house attached to the Classis Britannica fort. The occupation in question comprised a tightly disposed cluster of four sunken-featured buildings (N1-4), together with a modest ground-level timber building of two structural phases (N6 and N7). These buildings were accompanied by an extensive midden deposit (N5) dumped into a declivity formed by the partly silted exterior ditch of the late Roman-period shore fort, against the wall of one of its projecting bastions.

fig 7 Plan of excavated Anglo-Saxon features within the late Roman-period fort at Dover. Redrawn from Philp Citation2003, fig 1, with additions by author.

Further Anglo-Saxon buildings and occupational features were encountered in the shadow of the medieval church of St Martin-le-Grand – what the report defines as the ‘South Area’. The largest and most imposing were two substantial timber structures of post-in-trench construction, S14 and S10 (). These were spaced some 30 m apart in a broadly perpendicular disposition, the former being partially overlain by the southern transept of St Martin-le-Grand, and the latter situated hard up against the internal rampart of the late Roman fort’s western perimeter wall. Of these two structures, the report devotes most attention to S14, a building with a highly complex constructional history, unearthed in a series of separate interventions over a 5-year period between 1974 and 9 (). On the basis of its perceived longevity and spatial proximity to the overlying Norman edifice of St Martin-le-Grand, S14 is argued to represent the minster church and cult focus of the documented 7th-century monastic community of St Martin’s. Neighbouring buildings (including S10), as well as those in the North Area are duly attributed to the hypothesised monastic enceinte ‘for use by the canons for domestic or industrial purposes’.Footnote50

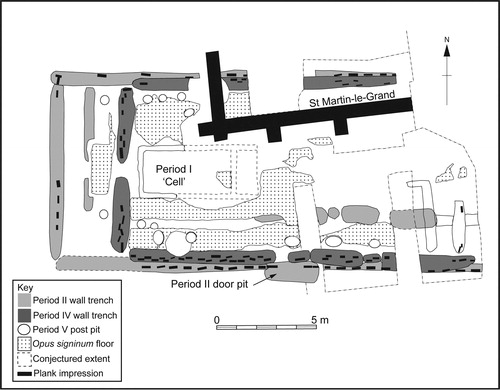

fig 8 Plan of Dover building S14. Redrawn from Philp Citation2003, fig 34, with additions by author.

On Philp’s reading S14 originated as a diminutive single-celled structure measuring 5 m × 2.7 m with a putative altar base at the eastern end (Period 1).Footnote51 After modest enlarging and remodelling, this primary core was subsequently encased by a substantial post-in-trench building (Period 2), itself rebuilt on three subsequent occasions over the 8th to the 10th centuries (Periods 3–5). In lieu of direct dating evidence, Philp tethers each end of the structural sequence on to two notional historical hooks — the foundation of the Anglo-Saxon monastic community of St Martin’s, and the Norman construction date of St Martin-le-Grand — to conjure a continuous sequence of building activity spanning the 7th to the 11th centuries.Footnote52

The other post-in-trench structure, S10, was the more fragmentary of the two buildings, with only portions of its southern and western walls exposed during excavation. If the author’s conjectured minimum width of 7.80 m is accepted, then this would have been a substantial building with a length in the region of 20 m.Footnote53 Three structural phases for the building are identified, only the second of which presented clear evidence for wall foundations in the form of shallow U-shaped trenches measuring 350–500 mm in width. The fill of the wall trenches displayed a continuous internal gulley, which Philp suggests held a horizontal wall plate; on analogy with other great halls, however, this feature more likely represents a non-structural feature associated with the occupation or dismantling of the building.Footnote54 This structure appears to have been built on the footprint of an earlier building represented by what the report describes as a ‘stone and mortar’ floor preserved in several discontinuous patches extending over an area of some 6 m × 5 m. The floor of this earlier building appears to have been partially reused by its successor (accompanied by a new compressed clay floor in the northern portion of the interior) with evidence for a subsequent repair constituting Period 3 of the hypothesised structural sequence.

Accompanying these focal buildings was a smaller and more lightly constructed clay-floored structure (S8), axially aligned with S14 and projecting just beyond its south-western corner. While later structural activity is present in this part of the site, this structure has strong claim to be contemporary with S14 on the grounds of its spatial alignment and affinities with ancillary structures recovered from Lyminge.Footnote55

Dover re-evaluated: the architecture of the great halls

Since it is the lynchpin of the author’s interpretation, it is appropriate to commence the present reappraisal with the putative church, S14. Before examining the details of the argument, it is worth emphasising at the outset that this building is completely out of character with the masonry apsidal churches associated with early monastic centres in Anglo-Saxon Kent, and bears little association with possible timber expressions of the same ecclesiastical building tradition which have been tentatively identified at certain 7th-century royal residences.Footnote56 One of the principal arguments proffered in support of S14 being a church is its supposed temporal endurance. Here the author takes his precedent from premier monastic sites such as St Augustine’s (Canterbury), Old Minster (Winchester) and Glastonbury, the monumental cores of which expanded incrementally over many centuries fuelled by the desire to enshrine saintly founders’ tombs and their translated remains.Footnote57

While there is no doubt that S14 was successively rebuilt on the same footprint, this analogy fails to stand up to critical scrutiny. Firstly, the longevity of each of S14’s structural phases (estimated in round centuries spanning the 7th to the 11th centuries ad) is unrealistically generous. Informed assessments of building life, based on scientific dating and experimental archaeology, suggest that Anglo-Saxon earthfast structures are unlikely to have endured much more than 40 years without major structural repair and rebuilding.Footnote58 Such estimates should also allow for the fact that the life of early medieval timber buildings was frequently cut short by conflagration (whether deliberate or accidental), and here it may be duly noted that S14 suffered precisely this fate in the third of its identified phases.Footnote59 With these considerations in mind, an overall duration of 100–120 years for S14 and its various iterations — rather than the proposed 400 — seems inherently more likely. Accepting that its initial construction date lies somewhere in the first half of the 7th century, there is no reason to believe that S14 endured much beyond ad 700, and a terminus within one or two decades either side of this date is entirely in accord with informed expectations.

A second problematic aspect of the structural sequence is the theory that the primary internal cell with its hypothesised eastern altar base was encased, relic-like, within the walls of the much larger post-in-trench building in the process creating lofty flanking aisles. It is very difficult to see how this arrangement would have worked in practical terms, particularly in respect of the structural mechanics of supporting the roof, given the significant variance between the very lightly built walls of the internal cell (constructed of flimsy stakes set in a shallow gulley) and the, by comparison, substantially founded external walls represented by the Period 2 and later wall trenches.Footnote60 It is admittedly difficult to appraise this aspect of the author’s interpretation given the extreme rarity of aisled buildings at this early period. Yet the instances that do exist, all from Yeavering (Halls A2 and A4), merely serve to cast further doubt on the interpretation by demonstrating that, in contradistinction to Dover, the internal roof supports of such buildings were both substantial and carefully positioned to articulate with other load-bearing components of the superstructure.Footnote61

Revealingly, no stratigraphic proof is presented in the report for the Period 1 cell being primary; indeed, a close inspection of the relevant plans and sections suggests that the relationship may have been very difficult (if not impossible) to discern stratigraphically during excavation.Footnote62 On the basis of the evidence presented, other scenarios are equally plausible. For example, the internal cell could have been a later insertion rather than a primary core, resulting (as appears to be shown on the relevant plan) in the truncation of the central portion of the opus signinum floor extending across the interior of the Period 3 hall. Alternatively, if the interior traces do indeed represent a contemporaneous element of a larger post-in-trench building, then the character of the evidence is more consistent with a free-standing screened antechamber of some kind, rather than a substantial, structurally enduring core around which the exterior walls were configured.

Serious doubt has been cast over the existence of a Period 1 cell and the idea that it was subsequently encased within the footprint of a much larger aisled building. When this and the other central pillar of the church thesis — the unfeasibly long structural history — are taken out of the equation, then it is possible to interpret S14 in a very different light. Writing before the advent of the recent Lyminge excavations, and relying more on instinct than a systematic appraisal of the evidence, Martin Welch recast the Dover site as a complex of grand halls ‘maintained by a royal official for periodic visits by the king’s itinerant court to his royal castellum in Dover’.Footnote63 The idea that the Dover occupation indeed represents the nucleus of a 7th-century villa regius can now be systematically tested through comparison with Lyminge, set against the wider backdrop of excavated great hall complex sites in England.Footnote64

As we have seen, Lyminge’s 7th-century occupation was focused on a planned arrangement of monumental timber halls of plank-in-trench construction, the two largest of which (A and C) compare very favourably in scale with S14 at Dover. Both sites display examples of halls that were sequentially rebuilt on the same, or overlapping, footprints. The constructional life histories of Dover S14 and Lyminge Hall C offer a particularly striking parallel. One of the peculiarities of these two halls is each phase of rebuilding was accompanied by an alteration in constructional technique: in the former case progressing from single rows of planks (Period 2) to double rows in a staggered disposition (Period 4), through to individual post pits (Period 5); and in the latter case from single planks (with exterior raking posts), through to double planks (set in parallel, not staggered, disposition), culminating in the same constructional shift from continuous foundation trenches to substantial posts set in individual pits.Footnote65

Comparison between Dover S14 (Period 2) and the third iteration of Lyminge Hall B brings yet another shared constructional idiom into focus: the treatment of the doorposts forming the principal long-wall entrances. In the majority of Anglo-Saxon timber buildings of post-in-trench construction, the principal entrances are marked by an interruption in the wall foundations with the doorjambs being positioned at the terminals of the adjacent lengths of trench, sometimes within deeper pits. In this particular case, however, the doorposts were accommodated within separately defined pits of substantial elongated proportions, in the case of Dover slightly offset from the main wall alignment (). While not necessarily unique to Anglo-Saxon Kent,Footnote66 this distinctive and unusual treatment adds credence to the idea that the Lyminge and Dover halls drew upon the same, locally propagated reservoir of architectural knowledge. From shared idiosyncrasies in the construction of doorways, we finally arrive at the most arresting and distinctive constructional affinity of all: the use, in certain of the identified hall phases, of sophisticated opus signinum flooring. To substantiate this observation and appreciate its full significance, it is necessary to undertake a detailed comparison of the excavated evidence.

Halls of timber, halls of stone: the use of opus signinum flooring

Taken in combination, the evidence presented from the two sites for the employment of this style of flooring is complementary and mutually supporting. Dover is crucial because the flooring was preserved in situ as part of deep urban stratification; whereas at Lyminge, in spite of being recovered in ex situ contexts, there are no underlying Roman structural levels capable of being confused with Anglo-Saxon buildings. The latter point is more pertinent than may first appear, because Welch has previously argued that Philp’s identification of S14 as a church was partly based upon such a stratigraphic conflation.Footnote67 This view can be, however, firmly rejected on two counts. Firstly, it is very difficult to reconcile with the technical competence of Brian Philp and his highly skilled excavation team who, by the point of the relevant interventions, had grown highly adept at reading the nuances of Dover’s complex urban stratigraphy.Footnote68 Secondly, and more fundamentally, neither S10 and S14 (contra Welch) were cut directly through Roman buildings: a close inspection of the report reveals that the former was constructed over the tail of the rampart bank of the late Roman-period shore fort formed from a 1.5 m deep accumulation of soil dumped over the walled yard of the earlier Classis Britannica bath-house; similarly, the foundations of the latter were cut through Roman period ‘deposits’, but not in situ masonry buildings ().

If the association between opus signinum floors and timber buildings at Dover can indeed be trusted, how closely comparable is the evidence from Lyminge? To answer this question it is necessary to examine the character and constituents of the flooring material represented at the two sites in greater detail. The floor in Dover S10 is described as comprising a base of rolled flints 100–120 mm in size, ‘laid in a compact bed across the building covered in a coarse cream concrete mortar containing small pebbles, varying in depth from 1 to 5 cm’.Footnote69 The floor in S14 (Period 3) was very similar in overall composition (a basal layer of flints capped by a compact white mortar with small pebbles) and thickness (120–130 mm), although it displayed the notable distinction of having a surface of opus signinum comprising ‘a thin skin of crushed tile and dust, barely 1 mm in thickness, that fused with the white mortar and provided a polished pink-red surface, perhaps in imitation of marble’.Footnote70 While the flooring in these two buildings thus appears to have been finished somewhat differently, the technical and aesthetic background is clearly one and the same.

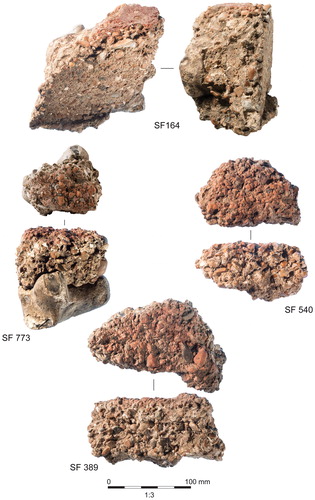

At Lyminge the relevant evidence was present in two related forms. The first was consolidated lumps of flooring recycled as packing material in the foundations (trenches and post pits) of stratigraphically superimposed halls, a treatment precisely paralleled at S14 Dover ( and Supplementary Material).Footnote71 These pieces were confined to the structural foundations of Halls B and C, the majority deriving from the western doorpost of the former and the partition doorway of the latter ().Footnote72 Sharing the same general distribution was evidence of a more indirect form: concentrations of flint gravel matching the aggregate used in the lime concrete constituent of the flooring.Footnote73 Two possible derivations account for this material: either it represents the decomposed raw constituents of further broken up fragments or, alternatively, on the reasonable assumption that the flooring was prepared in close proximity to the halls themselves, a by-product of spillages associated with the initial production process.

fig 9 Distribution of opus signinum flooring from Lyminge. Fragments are denoted by crosses. Illustration by Lyminge Archaeological Project.

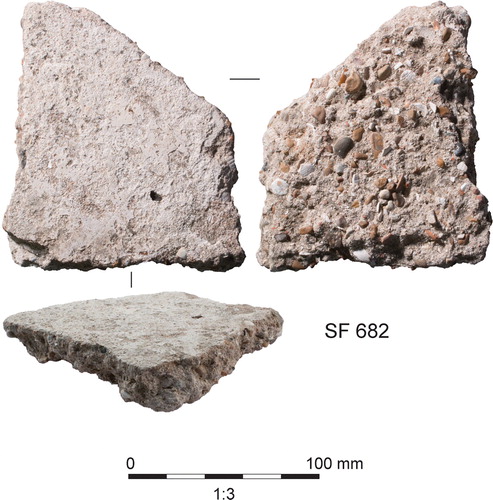

The five best-preserved fragments from Lyminge exhibit the same general composition as the Dover S14 floor, namely a basal layer of coarse flints over which has been poured a substantial layer of lime concrete finished with a surface skim (). In four of the five cases, the latter was prepared from crushed Roman brick or tile, but the results of detailed analysis indicate that the treatment was not uniform (Supplementary Material). One of the pieces (SF 164) displays a fine surface skim above the crushed terracotta layer with a darker red colouration compositionally related to red ochre ( and Supplementary Material for compositional analysis, ).Footnote74 Yet further diversity is introduced into the equation in the form of a fifth fragment (SF 682), of more slender proportions bearing a limewashed surface ().Footnote75 It is difficult to draw firm conclusions given the fragmentary, decontextualised nature of the evidence, but these results raise the distinct possibility that the floors concerned were variegated both in colour and texture, perhaps to emphasise and delineate certain parts of the hall’s interior.

fig 10 Fragments of opus signinum flooring from Lyminge. Photographs by Sarah Lambert-Gates. © Lyminge Archaeological Project.

fig 11 Fragment of opus signinum flooring, or possible internal walling, from Lyminge. Photographs by Sarah Lambert-Gates. © Lyminge Archaeological Project.

In terms of extant archaeological survivals, the Kentish halls find their closest affinities in the pseudo opus signinum flooring characterising the earliest generation of churches and monastic buildings from Anglo-Saxon England. These are represented locally at St Augustine’s and Reculver,Footnote76 and further afield at Wearmouth-Jarrow (Tyne and Wear) and Glastonbury (Somerset).Footnote77 The dominant type of opus signinum used in Kent (as represented in both great hall and ecclesiastical contexts) conforms to Wearmouth/Jarrow Type 3, where the use of the terracotta constituent is confined to a surface skim rather than being, in the classic Roman manner, more widely distributed through the matrix of the underlying lime concrete.Footnote78 Taken in conjunction, Dover and Lyminge provide compelling evidence that opus signinum floors formed part of the architectural vocabulary of some 7th-century Kentish great halls serving as royal accommodation. The significance of this observation will be explored in greater depth at a later juncture, but here it is worth briefly considering the implications of this archaeological discovery for Beowulf scholarship, for it does introduce a significant new context for interpreting the lexicography of the poem. The term in question, ‘fagne flor’, used in descriptive evocations of Heorot, has attracted considerable interest as a possible reference to a stone or tessellated floor but, as with many of the elliptical references within the poem, not without considerable uncertainty as to its authenticity.Footnote79 While it is impossible to know the exact precedents that shaped the poem’s imagery, the Kentish evidence assembled here at the very least suggests that fagne flor could have been inspired by the realities of mead-hall culture (whether contemporary or remembered), rather than representing mere artistic invention.

Dover re-evaluated: the occupation sequence

Having reconsidered the architecture of Dover’s great halls and their interpretive implications, it is now possible to offer a new narrative for the site’s evolution informed by comparisons with the Lyminge sequence. The natural starting point for this is the ‘early Saxon’ activity encountered in the North Area of the site. As we have seen, Philp assigns this activity to his notional monastic phase, in spite of an obvious contradiction posed by the early (ie pre-Christian) dating of some of the sunken-featured buildings (eg N3). A more informed reading would see this 6th-/7th-century occupation as a portion of an early settlement nucleus offering strong analogies with the ancestral focus identified at Lyminge. The parallels extend to a very similar repertoire of settlement components (a sprinkling of sunken-featured buildings in combination with evidence for contemporary ground-level buildings (N6) and an extensive midden deposit (N5), the latter offering a good parallel for the treatment of the solution hollow at Lyminge) and shared cultural signatures reflecting similar levels of material prosperity and specialist activities, such as fine metalworking.Footnote80

At some point during the 7th century the settlement was reconfigured around a newly constructed complex of great halls, with S10 and S14 (accompanied by its ancillary, S13) disposed in either a co-axial or centralised layout.Footnote81 On analogy with Lyminge, further halls might be expected to lie beyond the excavated area: a site to the north of St Martin-le-Grand being a distinct possibility. The layout of Dover lacks the orthogonal precision and symmetry of Lyminge and other great hall complexes, but here one must take into account the structuring influence of the Roman backdrop, not least the imposing defensive walls which may well have stood to full height during the Anglo-Saxon period.Footnote82

Although not a primary concern of the current discussion, the Dover site clearly experienced a significant afterlife, represented by glimpses of late-Saxon occupation within the Roman defences.Footnote83 It is very difficult to attribute meaning to such fragmentary remains, but on analogy with the Lyminge sequence, and given the propensity for pre-Viking religious communities to be established within former Roman forts, it is tempting to associate this occupation with the monasticisation of Dover as a formerly royal centre.Footnote84

Eynsford

The site of Eynsford provides the third of our trio of Kentish great hall sites. Excavated by the Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit and Bromley and West Kent Archaeological Group in two campaigns — again under the direction of Philp — it is the most incompletely sampled of the three sites and for this reason can be considered fairly briefly.Footnote85

Background context

The site of the great hall occupies a low terrace on the north side of the River Darent, some 200 m north-west of the parish church of St Martin, in an enclosed parcel of meadow within the built-up core of the modern-day settlement. This portion of the Darent valley (some 10 km from the River Thames at Dartford) features one of the densest concentrations of Romano-British settlement anywhere in Kent, including several opulent villa complexes, the most well-known being the site of Lullingstone, located some 1 km to the south-west of Eynsford (). The same tract of landscape also holds an impressive cluster of early Anglo-Saxon settlements and cemeteries, a significant proportion of the former being sited on, or in close proximity to villa sites.Footnote86 Eynsford exemplifies this continuity for the Anglo-Saxon occupation recently identified within the village lies a short distance away from a substantial Romano-British mortared stone building, very likely to represent part of a more extensive villa complex.Footnote87

Eynsford is located beyond the western frontier of the historic heartland of the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of Kent, marked by the River Medway, and for this reason is poorly documented in comparison to Lyminge and Dover. Notwithstanding this lacunae in historical sources, Alan Everitt has advanced the plausible theory that Eynsford formed one of a series of early river estates strung along the axis of the Darent valley, which had coalesced into a royally administered core territory, or regio, before the 7th century.Footnote88 Eynsford’s trajectory cannot be traced with the same level of confidence as Darenth, the eponymous caput of the Darent regio, which remained in the king’s hands until the 10th century, but Everitt argues that it may have originally held jurisdiction over the neighbouring parishes of Farmingham, Lullingstone and parts of Chelsfield ().

Occupation sequence

The Anglo-Saxon occupation described in the Eynsford report was initially encountered during trial trenching in 1991, prompting the excavation of a 12 m by 6 m window in the southern sector of the site. This uncovered a single sunken-featured building, together with the partial ground plan of one, or possibly more, ground-level earthfast buildings represented by external alignments of post holes. These structural components were accompanied by an intact occupation horizon (L-4), rich in domestic midden material, sealed beneath a metre of topsoil and overburden. A 6th-/7th-century date can be ascribed to this occupational focus on the basis of the sizeable assemblage of cultural material recovered which included over 500 sherds of Anglo-Saxon pottery, annular loomweights and other weaving equipment.Footnote89

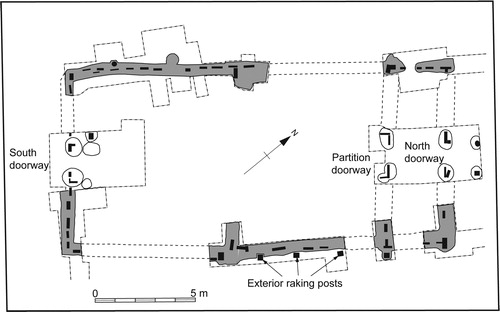

Excavated between 2009 and 2012, the site of the great hall was identified some 50 m north-east of the occupation just described. Rather than being exposed in full, the structure was targeted by a series of small trenches on a piecemeal basis, meaning that certain parts of the published ground plan remain conjectural (). Notwithstanding the highly fragmentary nature of the excavations, a reasonably coherent impression of the hall has emerged supported by, in places, very revealing structural detail. The building was laid out on the NE/SW axis and measured 20 m by 10 m with an internal partition set 3 m inside the north-eastern end wall. The external walls of the building were represented by continuous foundation trenches measuring some 500–600 mm wide and 600 mm deep, each containing the impressions of rectangular posts set in a single row towards the exterior edge of the trench, and flanked by alignments of regularly spaced post holes representing external raking timbers of sturdy proportions.

fig 12 Plan of great hall from Eynsford. Redrawn from Philp Citation2014, fig 5.

The building appears to have been provided with two opposing pairs of external doorways, those on the long axis of the hall being aligned with a further doorway pierced through the internal partition. In each case the doorjambs comprised adjoining planks arranged in an L-shaped configuration set in substantial pits packed with flint and gravel; the widths of the five doorways was relatively consistent ranging from 1.06 m to 1.15 m. Additional structural detail was provided by copious quantities of walling material recovered from the hall’s foundations, described in the report as a form of ‘plaster’ comprising ‘a weak white mortar, perhaps in at least two different fabrics, sometimes showing a thin external added layer and sometimes a painted white surface’.Footnote90 The foundations of the hall produced a scarcity of datable artefacts, the only items of note being two fragments of vessel glass, one amber in colour and the other pale green with applied ribbing, which could as easily derive from the adjacent 6th-/7th-century occupation as from that of the hall itself.

As a postscript it may be noted that, as far as can be gleaned from the results of these excavations and other strands of evidence, the settlement appears to have shifted to a new site following the abandonment of the Eynsford hall. As at Lyminge, the use of the hall complex presages a major episode of restructuring in the location and spatial configuration of the settlement.

DISCUSSION

The foregoing analysis has situated Lyminge, Dover and Eynsford firmly within the Anglo-Saxon great hall complex tradition and, in the process, identified a repertoire of family traits embodied by the three sites as a distinct regional grouping. The following interprets the meaning and significance of these patterns, both in the local context and for a wider understanding of the great hall complex phenomenon, through three complementary thematic prisms: topographic context; temporality and social memory; and monumental hybridity.

at the water’s edge: the topographic context of royal residence

One of the most obvious similarities displayed by the three sites is their proximity to rivers, the distances involved being as little as 50 m for Lyminge, 80 m for Eynsford and about 100 m for Dover (). The intimacy of this association is very much underlined by the fact the sites concerned occupy locally prominent settings within valley bottoms — river terraces and minor spurs — rather than the much more visually dominant and defensible positions offered by neighbouring ridgetops and promontories. In each of the three cases the watercourse concerned would have been directly visible from its adjacent hall complex and doubtless exerted a powerful influence on how the site was perceived and experienced.Footnote91

It is worth pausing to reflect on the significance of this correspondence in light of the distinctive role of the sites concerned as places of royal residence. Part of the attraction of a riverine locale must have lain in a ready supply of fresh water — an essential requirement for the gatherings of humans and animals that characterised the life at royal vills as places of periodic assembly — and ease of transportation. Yet it would be wrong to explain the association in such narrowly deterministic terms. As prime arenas for promulgating royal ideology, places of pre-Viking royal residence were contrived to harness sources of sacral and supernatural authority embedded in particular landscape settings. Rivers held a special place in Anglo-Saxon communities’ perceptions of, and interactions with, the numinous world, particularly as a traditional setting for the ritual-laden sphere of public assembly.Footnote92 There is good reason to believe that this association was taken to theatrical extremes in the context of the earliest sites of royal residence, as illustrated by the 36-day mass baptism orchestrated by Bishop Paulinus in the River Glen at the villa regia of Yeavering. Footnote93 This tantalising reference, combined with the trajectory of royal vills such as Lyminge which were subsequently ‘monasticised’, serves as an important reminder that contemporary sites of kingly residence were deeply entangled in narratives of conversion and the contingent process of resacralising the landscape. While difficult to visualise directly through the archaeological record, the ritual affordances of a riverside setting can only have enhanced pre-Viking royal residences’ efficacy as a prime locus for negotiating the process of Christianisation.Footnote94

the social memory of royal landscapes: hall building as a genealogical strategy

The antecedent life of the three great hall complex sites can also be shown to be crucial in structuring their river-valley locations. Indeed, the appropriation of pre-existing settlements and the ancestral authority which such appropriation conferred, arguably constitutes the overriding factor in determining their placement within the landscape. All three sites occur within river valleys which, as can be adduced from a convergence of archaeological and place-name evidence, constitute some of the earliest concentrations of recognisably ‘Anglo-Saxon’ occupation in Kent. These ‘valley estates’, to give them the name adopted by Everitt, feature an unusually high density of 5th-/7th-century sites, displaying a characteristic spatial disposition with settlements typically confined to the floor of the valley and overlooked by cemeteries occupying adjacent flanks at fairly regular intervals of 1–3 km.Footnote95

Tom Williamson has argued that river territories of the kind exemplified by the Darent, Dour and Nailbourne in Kent were highly significant in structuring patterns of contact and connectivity between early medieval communities and, as such, can be regarded as essential building blocks in the formation of social identities in early Anglo-Saxon England.Footnote96 This national perspective can be grounded in insights drawn from localised examinations of Anglo-Saxon mortuary landscapes in southern England, including in Kent itself. Research conducted at this detailed analytical scale has elucidated the important role played by cemeteries in the visual, mnemonic and symbolic articulation of these territorial ‘heartlands’, taking advantage of the fact that they were traversed by major routeways responsible for channelling movement through the landscape.Footnote97

It is thus clear that the three Kentish great hall sites were established within what might be thought of as core territories or ‘heartlands’, representing core zones of early medieval habitation within their respective localities. This relationship takes on heightened significance when we examine the spatial and temporal trajectory of the sites concerned at a more fine-grained level. While Eynsford is more equivocal, the great hall complexes at Lyminge and Dover were both superimposed on pre-existing settlements that were long established by the turn of the 7th century. Moreover, both sites demonstrate clear evidence for a central-place role in the 6th century, adducible archaeologically by shared evidence for conspicuous consumption, social display, and skilled crafting.

The pattern of appropriation seen in the group of Kentish sites, no less apparent in the lengthy sequence of high-status activity recently brought to light at Rendlesham (Suffolk), has importance for a wider understanding of the mnemonic strategies focused on places of royal residence in conversion-period England.Footnote98 Understandably, previous commentators have been attracted by the very explicit cases of prehistoric monument reuse presented by the corpus of English great hall sites taken to the theatrical extreme at Yeavering, where the axes of the main hall array were fixed in relation to a pair of Bronze-Age funerary monuments.Footnote99 Yet while the manipulation of the distant past undoubtedly represents an important characteristic of these sites, however, it has arguably drawn attention away from temporal interplay between great hall complexes and their immediate antecedent phases. The monumental core of Yeavering evinces this interplay very clearly in sequences of hall construction initiated by, and focused on, lightly built structures dating back to the embryonic (6th-century) phase of the settlement, and the same tendency finds expression in the excavated sequence from Cowdery’s Down.Footnote100 Granted, the Kentish evidence is more consistent with general locational rather than precise structural continuity, but the underlying motivation and rationale is very likely to have been the same: monumentalising places of dynastic importance as a strategy for legitimating and reifying royal authority.Footnote101

One has to turn to the climactic 7th-century phases of the Kentish sites to find more emphatic reflections on the theme of sequential rebuilding: in the case of Dover, S14 was rebuilt on at least three, and quite possibly more, occasions on the same site and S10 at least twice, whereas at Lyminge Halls B and C passed through three iterations on the same or on narrowly diverging footprints (). In the case of the latter, there is clear evidence that these cycles of reconstruction involved structural as well as locational continuity, reflected in the fact that foundation trenches were sometimes reused from one phase to the next.Footnote102 Helena Hamerow has previously drawn attention to the significance of this general practice, remarking that:

it is thus at [these sites] that we first see an interest in extending the longevity of important buildings’, as means to ‘embody and evoke links with ancestors’, further observing that ‘it was entirely possible that there was a connection between this desire to create long-term relationships with a place and the growing importance of landholding and inheritance.Footnote103

This perspective can be developed further by considering how the biographies of the halls themselves, embodied in cycles of construction, use and destruction, may have evoked notions of permanence, ancestry and dynastic memory. As is well known, Kent enjoys a richer survival of origin legends and royal genealogies than any other Anglo-Saxon kingdom, and for this reason it offers a very instructive context for situating great hall sites within a wider body of mnemonic traditions which rapidly proliferated in conversion-period England.Footnote104 As with their peers in other regions of Anglo-Saxon England, the Kentish royal house displayed an intense interest in the art of dynastic manipulation. At an early stage in what was likely a drawn-out process of elaboration, ‘Oiscingas’ had emerged as the dynastic family name for rulers of Kent.Footnote105 This name was derived from the eponymous figure, Oisc, one of a cast of mythic characters through which the kings of Kent traced ultimate descent and legitimacy from Woden — progenitor par excellence for Anglo-Saxon royal houses.Footnote106 Moreover, genealogical fabrication of this type was not only confined to the male members of the Kentish royal line. As research on the body of related texts known as the ‘Mildreth Legend’ has shown, dynastic memory, and the authority this conferred over property and landed resources, was also transmitted through origin myths woven around female members of the Kentish royal house in their capacity as abbesses and proprietors of substantial monastic endowments.Footnote107

Returning to the archaeological evidence itself, the idea that the cyclical rhythm of hall building witnessed at excavated sites of royal residence may have been synchronised with the ebb and flow of dynastic power is hardly novel: such a conception forms the crux of Brian Hope-Taylor’s (ultimately flawed) chronological interpretation of Yeavering as the villa regia for a documented succession of Bernician kings.Footnote108 Beowulf of course provides a famous and highly suggestive literary precedent wherein the construction of Heorot serves to inaugurate Hrothgar’s ascendancy to the Danish throne as the supreme personification of his kingship, power and right to rule.Footnote109 Similar conceptions, drawing upon a wider body of literary allusions supplied by Icelandic sagas, have also been applied to the interpretation of Scandinavian magnate residences of the migration and Viking periods, characterised by lengthy sequences of hall reconstruction in some cases spanning hundreds of years.Footnote110 In the case of this particular sphere, the foundation deposits commonly discovered on hall sites provide added witness to the significance of hall construction as an intensely political act immersed in the rituals of inauguration and sacral legitimation.Footnote111

More than simply broadcasting new rulership, however, the sequential rebuilding characteristic of the Kentish and other English great hall sites suggests that there was a strong retrospective and commemorative element to hall building — a conscious attempt to proclaim genealogical links with the past through the manipulation of monumental space.Footnote112 This behaviour bears comparison with Howard Williams reading of the elite funerary landscape of Sutton Hoo as a monumental genealogy where ‘a chain of monumental episodes’ was composed to ‘create social memories and relations between past and present’ in relation to origin myths and genealogies.Footnote113 The clear difference in the examined context is that genealogical memory was transmitted through cycles of (re-)construction in a single locale rather than through a series of spatially discrete monuments which referenced each other as enduring elements of the landscape. Here the destruction and/or disassembly of halls and its natural corollary — the reuse and re-incorporation of building materials from earlier phases into new phases of construction — can be conceived as an active part of the embodied and communally enacted practices through which dynastic memories were recalled and transmitted.Footnote114

A final dimension on the mnemonics of such sites is provided by ritual deposits. Although often treated as a self-contained category in examinations of the great hall complex phenomenon, this aspect deserves to be considered as an integral part of creating memory and genealogy, since they can often be shown to be biographically entwined with the construction, use and abandonment of halls.Footnote115 As Hamerow and more recently Clifford Sofield have shown, English great hall sites manifest such practices more subtly and rather differently than early medieval magnate residences in Scandinavia, which attracted a rich panoply of ritual deposits, especially, as we have seen previously, in connection with the inauguration of halls.Footnote116 As will be shown presently, Kent very much conforms to the English picture and the relevant signals need to be interpreted at this level of sensitivity.

At Lyminge, three items of metalwork classifiable as intentional closure deposits — an annular brooch, dress-pin and an elaborate horse-harness fitting — were recovered from halls spanning both the antecedent and climatic phases of the complex.Footnote117 This complements a rather more spectacular case of ritual closure in the form of a plough coulter concealed in the abandoned shell of a 7th-century sunken-featured building associated with a peripheral portion of the settlement.Footnote118 Dover presents further compelling evidence for such behaviour, most notably a 7th-century glass bell beaker recovered from the Period 2 foundations of hall S14.Footnote119 Quite remarkably given its fragility, this vessel was recovered substantially intact as if it had been recovered from a grave, which speaks eloquently of the care and reverence invested in its concealment.

A useful way of pulling the various strands of the foregoing discussion together is by thinking of great hall complexes as nexuses where genealogical memory was manufactured through a convergence of mutually reinforcing practices. Seen in this light, these sites can be argued to embody an interface between the internal theatre of the mead-hall on the one hand — stage-sets where the highly stratified origin myths portrayed in royal genealogies were literally acted out as choreographed showpiecesFootnote120 — and the monumental affordances of the structures themselves which provided a powerful vehicle for evoking and manipulating genealogical memory.

hybridity and the genesis of a monumental tradition

This concluding thematic excursus begins with the premise that the great hall complex phenomenon needs to be understood and interpreted in the context of its own time (ie the 7th century), and accordingly that previous attempts to understand its significance in terms of the fusion of ethnic traits are flawed and limiting.Footnote121 As previous studies have shown, there were fundamental differences between the age of the great hall complex and the preceding two centuries in relation to the dynamics of the ethnogenesis process, with the 7th–8th centuries recognised as a period of accelerating acculturation associated with new, highly politicised, expressions of ethnic affiliation.Footnote122

Attention instead needs to be shifted towards understanding the phenomenon as the product of particular, historically contingent circumstances which shaped how elite groups in 7th-century England chose to articulate and represent their power. Progress towards this aim can be made by engaging with recent studies which have explored the distinctive material strategies employed in the assertion of 7th-century kingship and elite authority. A unifying theme brought to attention by this work is the highly assimilative character of these strategies: the inventive fusion of traditional practices with external influences to generate new ways of articulating power that had meaning and resonance in local contexts — a process which was accelerated and given intensified expression by the conversion of the Anglo-Saxon aristocracy.Footnote123 It is very much in this vein that royal hall culture in Kent needs to be explained and interpreted.

The study speaks directly to this theme by divulging how great hall architecture in Kent followed a distinct, classicising path under the radiating influence of Canterbury as the epicentre of the Augustinian mission. In the case of Lyminge this influence can be detected in the site’s precise grid-planning, a Romanising idiom first deployed in England in relation to the early churches at St Augustine’s, Canterbury.Footnote124 However, it is in the distinctive vocabulary of architectural flourishes displayed by the trio of Kentish sites that this theme finds unified expression. In their different ways the great halls of Kent embody a reverence for Romanitas as a key plank in the legitimating ideology of the newly converted Kentish court: Eynsford with its white plaster cladding, and Dover and Lyminge with their elaborate opus signinum floors technologically identical to the flooring used in near contemporary ecclesiastical buildings. Of course, what makes these latter constructions particularly arresting as embodiments of the assimilative character of 7th-century hall culture, is that that they cut directly across the timber/stone dichotomy lying at the heart of Anglo-Saxon architectural studies.Footnote125

This is not the first time that a dialogue between timber great hall complexes and early masonry churches has been observed. The similarities between Yeavering and ecclesiastical buildings in Northumbria have attracted repeated attention over the years, especially with regards to dimensions and axial plan-forms, although opinion is divided on the extent to which the former may have served as direct models for the latter.Footnote126 While an interplay of sorts is unquestionably embodied in the monumental landscape of Northumbria, what we see here is more akin to translation or transposition from one context to another, a process eloquently expressed in Eric Fernie’s assessment of Escomb church (Co Durham) as a ‘bridge between two very different traditions, using the layout of one, the Germanic, and the masonry techniques of the other, the Roman’.Footnote127

By contrast, the great halls of east Kent featuring opus signinum floors can be regarded as genuine architectural hybridisations which in their novelty and ingenuity are every bit as redolent of the ‘powerfully creative interaction of Mediterranean and indigenous traditions’ as are the manuscript art and stone sculpture of conversion-period England.Footnote128 This insight can be developed further by thinking through the likely mechanisms that lay behind the appearance of these hybrid constructions. A natural question which emerges in this context is the extent to which the floors in question were directly inspired by Roman buildings given that Kent enjoyed a particularly strong Imperial inheritance.Footnote129 While there is no reason to believe that these relic monuments exercised less of an influence on the cultural practices and imagination of early medieval communities of Kent than those in other parts of Anglo-Saxon England, indeed, quite the contrary,Footnote130 it is important to remember that the construction of such a floor would have depended upon the mastery of a spectrum of techniques executed in a precise sequence of stages constituting a complex chaîne opératoire.Footnote131 The evidence presented by these halls fits much better in the context of a contemporary revival of antique traditions achieved through and in relation to the imported technologies of the Roman Church than local experiments in aping the Roman past. An acceptance of this argument leads to an arresting implication: that the Frankish and Italian stone masons enlisted to build the earliest churches in Kent were also deployed in the aggrandisement of contemporary royal accommodation.Footnote132

CONCLUSION

By harnessing the collective interpretive potential offered by the great hall complexes of Lyminge, Dover and Eynsford, this article has opened a new archaeological perspective on royal hegemony in 7th-century Kent, and in the process enriched its status as a fundamental context for the study of kingship in early medieval England. The insights generated by this comparative study demonstrate that great hall complexes played a key role in the assertion of royal authority during the period of independent Kentish supremacy, and that the monumental idiom was adapted and given fresh expression under the influence of the Romanising programme of the Augustinian mission.

Integration of the rich material perspectives offered by the trio of Kentish sites with contextual sources and theoretical approaches has revealed new insights into how great hall complexes operated as arenas for asserting power, lineage, and authority in an age of rapidly accelerating political centralisation. Their efficacy as ‘theatres of power’ was grounded in the strategic exploitation of meaningful and highly resonant settings that held deep ancestral and dynastic significance, while at the same time fulfilling the practical and ritual requirements of royal assembly. The distinctive temporal qualities and rhythms of these sites, combining relatively transient and episodic monumental life histories on the one hand with longer-term and more persistent ‘central-place’ trajectories on the other, have been argued to offer a crucial perspective on pre-Viking royal landscapes as reservoirs of social memory. As has been argued in relation to contemporary elite mortuary landscapes, these places were deeply implicated in the genealogical practices of 7th-century royal dynasties, offering multiple, mutually re-inforcing outlets for channelling dynastic memory. These were mediated through the interior theatre of the mead-hall as a prime locus for the creation and manipulation of origin myths and through sustained, cyclical programmes of monumental investment on an unprecedentedly lavish scale.