Abstract

THIS ARTICLE CRITICALLY REVIEWS THE ARCHAEOLOGICAL STUDY of high- to late-medieval burials (c ad 1000–1550), examining how and why research questions have changed in recent decades. Examples are drawn from Christian mortuary practices principally from Britain, northern and central Europe, to demonstrate increasing emphasis on the social study of emotion, agency and place. The question of social ‘value’ is addressed, exploring how disciplinary research agendas respond to altering academic currents and wider public concerns regarding medieval burials. Four themes are examined that characterise key developments: (1) a shift towards the micro-scale; (2) the exploration of emotion, with particular focus on child and infant burials; (3) a pre-occupation with ‘deviancy’ (non-normative practices); and (4) ethical considerations in the public consumption of medieval burial archaeology. Recommendations for future work include the need for comparative, larger-scale analyses to map diachronic and regional patterns across medieval Europe and to counterbalance recent trends towards the local and the individual.

Résumé

Des voix émanant du cimetière : l’archéologie sociale des sépultures de la fin du Moyen-Âge par Roberta Gilchrist

Cet article pose un regard critique sur l’étude archéologique des sépultures allant du Haut Moyen-Âge jusqu’à la fin de la période médiévale (env. 1000–1550), en examinant de quelle manière les questions posées par la recherche ont évolué au cours des dernières décennies et pour quelles raisons. Des exemples sont tirés des pratiques mortuaires chrétiennes principalement en Grande-Bretagne et en Europe du Nord et centrale, pour montrer que l’on s’intéresse davantage à l’étude sociale de l’affectif, de l’action et du lieu. La question de la « valeur » sociale est abordée, pour explorer la réponse des programmes de recherche disciplinaire face à la modification des courants universitaires et plus largement aux préoccupations du public en ce qui concerne les sépultures médiévales. Les quatre thèmes examinés caractérisent les principaux développements : 1) un glissement vers une micro-échelle ; 2) l’exploration de l’affectif, en se focalisant particulièrement sur les sépultures d’enfants et de nouveau-nés ; 3) une préoccupation à l’égard de la « déviance » (pratiques échappant aux normes) ; et 4) les considérations éthiques ayant trait à la consommation publique de l’archéologie des sépultures médiévales. Des recommandations sont faites concernant de futurs travaux, notamment la nécessité d’analyses comparatives à grande.

Zusammenfassung

Stimmen des Friedhofs: Die soziale Archäologie der spätmittelalterlichen Bestattung von Roberta Gilchrist

Dieser Artikel gibt einen kritischen Überblick über die archäologische Untersuchung hoch- bis spätmittelalterlicher Bestattungen (ca. 1000-1550 n. Chr.) und beschäftigt sich damit, wie und warum sich die Forschungsfragen in den letzten Jahrzehnten verändert haben. Anhand von Beispielen christlicher Bestattungspraktiken, vor allem aus Großbritannien, Nord- und Mitteleuropa, wird die zunehmende Bedeutung der sozialen Erforschung von Emotionen, Handlungsfähigkeit und Orten aufgezeigt. Die Frage nach dem sozialen „Wert“ wird behandelt, wobei untersucht wird, wie disziplinäre Forschungsagenden auf sich verändernde akademische Strömungen und Bedenken der breiten Öffentlichkeit hinsichtlich mittelalterlicher Bestattungen reagieren. Es werden vier Themen untersucht, die wesentliche Entwicklungen darstellen: 1) eine Verlagerung auf die Mikroebene; 2) die Erforschung von Emotionen, mit besonderem Augenmerk auf Kinder- und Säuglingsbestattungen; 3) die Beschäftigung mit „Devianz“ (von der Norm abweichenden Praktiken); und 4) ethische Überlegungen bei der öffentlichen Nutzung der mittelalterlichen Bestattungsarchäologie. Zu den Empfehlungen für künftige Arbeiten gehören Vergleichsanalysen in größerem Maßstab, um diachrone und regionale Muster im gesamten mittelalterlichen Europa abzubilden und dem Trend zum Lokalen und Individuellen der letzten Jahrzehnte entgegenzuwirken.

Riassunto

Voci dal cimitero: l’archeologia sociale delle sepolture tardomedievali di Roberta Gilchrist

Questo articolo fa una revisione critica degli studi archeologici sulle sepolture, da quelle altomedievali fino a quelle tardomedievali (dal 1000 al 1550 d.C.), esaminando come e perché le questioni della ricerca siano cambiate nei decenni recenti. Gli esempi sono tratti dalle pratiche mortuarie cristiane soprattutto in Gran Bretagna e nell’Europa settentrionale e centrale per dimostrare la crescente importanza attribuita allo studio sociale di emozione, potere e luogo. Si affronta la questione del “valore” sociale, indagando su come i programmi della ricerca disciplinare rispondano alle correnti accademiche trasformatrici e alle preoccupazioni dell’opinione pubblica relative alle sepolture medievali. Si esaminano quattro temi che caratterizzano gli sviluppi chiave: 1) spostamento verso la microscala 2) indagine sulle emozioni, con attenzione speciale alle sepolture dei neonati e dei bambini 3) preoccupazione riguardo alla “devianza” (pratiche che violano le norme) e 4) considerazioni etiche sull’utilizzo pubblico dell’archeologia medievale delle sepolture. Tra le raccomandazioni riguardo al lavoro futuro figura la necessità di analisi comparative su più larga scala per rilevare le configurazioni diacroniche e regionali di tutta l’Europa medievale e controbilanciare le recenti tendenze verso la località e l’individuo.

Which deaths mattered to people in the later Middle Ages—and which medieval deaths matter today to archaeologists and the wider public?Footnote2 This article surveys trends in the archaeological study of burial in late-medieval Europe (c ad 1000–1550), drawing on case studies principally from Britain, northern and central Europe, to discern growing emphasis on the role of emotion, agency and place in shaping medieval Christian burial practices. This contrasts with previous frameworks that focused exclusively on religious identity and social status in determining medieval burial rites. While graves were formerly regarded as static reflections or symbolic statements, recent approaches re-imagine burials as ‘vitalist devices’ that continuously negotiate relations between the living and the dead.Footnote3 Responding to Fredrik Fahlander, this paper asks: what did medieval burials do? It begins by introducing the shared tradition of late-medieval Christian burial in Europe, before identifying distinctive trends in the social study of medieval burial archaeology. Three themes are considered in closer detail: a shift towards the study of individuals and the micro-scale; the special treatment of the graves of infants and children; and the ‘deviant’ dead. Finally, medieval burial is situated within the sphere of public archaeology, reflecting on the different types of ‘value’ that are accorded to medieval burials and how this shapes the research questions that we ask about medieval death. All archaeological remains have the potential to hold social value as heritage, contributing to people’s sense of identity, belonging and place, but human remains require scrupulous consideration.Footnote4 What contemporary value do we project onto late-medieval burials—emotional, religious, political, economic?

UNLEASHING HETERODOXY

The material evidence of medieval death has attracted a long tradition of scholarship: antiquaries investigated elite tombs from the late 18th century onwards, and beginning in the mid-20th century, medieval graves were routinely excavated as part of the archaeological investigation of medieval churches and monasteries.Footnote5 But social questions were directed towards medieval burials only relatively recently, in sharp contrast with other periods of archaeological study, where burial evidence has long underpinned the most vibrant research on past social lives. Both the interpretative potential of medieval burial archaeology and the diversity of funerary practices were underestimated until around 30 years ago. Medieval burials were previously characterised by historians and archaeologists as homogenous and normative, representing a narrow range of mortuary behaviour controlled by a religious elite.Footnote6

The evidence base for medieval burial has burgeoned with commercial archaeology and the excavation of large (principally urban) medieval cemeteries. Approaches to interpretation began to change in the 1990s, as the discipline of medieval archaeology matured both in terms of data collection and theoretical awareness. Large-scale studies in Denmark, France and England confirmed common trends in medieval European burial over time, such as the increasing use of coffins and the decreasing numbers of grave goods.Footnote7 In general terms, burial rites became more uniform from the 12th century onwards, perhaps coinciding with the increasing centralisation of the Church and the formalisation of the doctrine of purgatory. However, in recent decades archaeologists have identified a varied cultural repertoire of medieval Christian burial practices, including the use of grave linings and coffins, devotional objects and apotropaic materials placed with the corpse, and the systematic organisation and management of cemetery space. To what extent can we discern a coherent tradition of medieval European Christian burial practice? The graves treated most consistently were those of religious—priests, monks, nuns and ecclesiastics entered the afterlife equipped with their emblems of religious office and clothing of consecration.Footnote8

Distinctive rites were practised in multiple regions of Europe, suggesting the mobility of people and/or the transmission of religious ideas about the afterlife. These include the ‘funeral pots’ containing charcoal that were commonly placed on coffins in France and Denmark; timber rods or staves deposited in graves in England and Scandinavia; papal bullae interred with the dead, especially in France and England; and scallop shells associated with burials particularly in Germany and Scandinavia.Footnote9 However, regional studies also demonstrate significant differences arising from specific cultural contexts and conversion histories; for example, Estonia’s forced conversion in the 13th century led to the persistence of pre-Christian burial rites into the 16th century, including cremation rites in remote areas, and food and other offerings placed in inhumation burials.Footnote10 In northern Finland, the extended process of Christianisation prompted locally distinctive traditions, including hybrid burial practices and the continuation of cremation alongside Christian rites in the 13th–14th centuries.Footnote11 The regional nuances and chronological variations of the shared tradition of medieval European burial have yet to be mapped, but local differences are apparent between cemeteries even in the same region. While burial practices drew largely upon a common vocabulary of Christian mortuary rites, individual cemeteries demonstrate idiosyncratic preferences in traits including positioning of the body, the shape of the grave, the prevalence of ‘multiple burials’ (ie the interment of more than one individual in a single burial plot), the frequency of clothed burial, or the selection of specific objects and materials placed with the dead. Archaeology is a persuasive rejoinder to contemporary textual sources detailing medieval burial practices, such as the 13th-century liturgist, William Durand of Mende.Footnote12 Religious authors present a picture of strictly controlled orthodoxy, but they had little insight into lived religion in ordinary communities, for example the agency of women and the family in funerary rites. Archaeologists place increasing emphasis on the social role of funerary landscapes in creating a sense of place, a collective local identity that connected the communities of the living and the dead.Footnote13

Medieval Christian burial rites differed significantly from contemporary Jewish and Muslim traditions. Perhaps the most striking contrast is the greater emphasis in Islam and Judaism on bodily integrity after death, resulting in the protection of burials from subsequent disturbance. In contrast, Christian cemeteries routinely reused cemetery space, resulting in the intercutting of graves and the disturbance of bones that were collected as charnel. For example, the excavation and analysis of Jewbury, the medieval Jewish cemetery in York (c 1177–1290), confirmed there was very little intercutting of graves (12%) in comparison with Christian cemeteries in medieval York.Footnote14 There was greater uniformity in burial practice within the Jewish cemetery: 70% were in the same burial position, supine and fully extended, and there were no personal objects included with the dead. However, Jewbury also demonstrated that normative Jewish burial rites were modified in diaspora contexts, resulting in variations in grave orientation and the use of iron coffin nails (rather than the wooden dowels specified in Orthodox practice). Local variations are also becoming apparent in the study of Muslim burial practices in Sicily and Al-Andalus (the medieval Iberian Peninsula). The expectation was for Muslim corpses to be wrapped in shrouds and placed in the grave on their right side, oriented towards Mecca; the use of grave markers and grave goods was discouraged, and single-occupancy graves were the norm. However, Sarah Inskip has noted considerable variations in Al-Andalus in the positioning of the body in the grave, and the placing of personal grave goods in around 2% of burials.Footnote15

SPIRITUAL STRATEGIES: MEDIEVAL MOURNING, MATERIALITY AND MARGINALITY

Over the past decade, research in medieval burial archaeology has largely rejected previous assumptions of orthodoxy and normativity in medieval death rituals. A unique archaeological contribution has revealed funerary rites that were never documented in religious texts, highlighting the agency of mourners and the role of families and communities, particularly women.Footnote16 This is glimpsed especially through objects placed in intimate contact with the corpse during the preparation of the body for burial. These were often modest objects such as beads and coins, or devotional items, including papal bullae; these artefacts are exceptional in terms of their rarity and survival, represented in perhaps 2–3% of excavated high- to late-medieval graves.Footnote17 Recent research pays more explicit attention to mourning, grief and loss, especially in relation to the graves of infants and children. A strong interest has emerged in how diverse social groups were treated in death, including children, the disabled, and non-normative, ‘deviant’ categories such as executed criminals.Footnote18 To what extent do these trends coincide with the wider field of burial archaeology and with the historical study of medieval death? What is distinctive about medieval burial archaeology?

Recent historical study of medieval death examines similar themes, including a strong focus on treatment of the corpse, parental grief and mourning, folk practices and the lived religion of death, and the deviant dead.Footnote19 It is therefore surprising to find so little collaborative, interdisciplinary engagement between medieval historians and archaeologists around the subject of medieval burial. Historians and art historians tend to approach burial through questions of patronage and commemoration, in contrast with the more bottom-up, ‘marginal histories’ advocated by archaeologists. The emerging archaeological focus on marginalised people also highlights racial diversity and health disparity in medieval Europe; for example, a study of London’s Black Death cemetery examined the forensic ancestry, ancient DNA and isotopes of a sample of 41 individuals, seven of whom yielded evidence for Black African ancestry or dual heritage.Footnote20 ‘Marginalised histories’ are also a characteristic feature of post-medieval burial archaeology,Footnote21 while the ‘materiality of death’ has come to prominence in the mortuary archaeology of all periods, emphasising treatment of the corpse and ritualised practices performed in relation to death, including deviancy and violent death.Footnote22 There has been growing interest in theorising the dead body as a material object and exploring the materiality of the grave in terms of emotional relationships between the living and the dead.Footnote23 In early medieval burial archaeology, the theme of materiality focused on the sensory performance of funerary rites to structure memory; it is argued that burials were framed as poetry or theatre for the living.Footnote24 The lens of ‘performance’ has impacted less explicitly on late-medieval burial archaeology, although graves have been analysed in terms of ritual performances and visual displays that structured active relationships between the living and the dead, such as the dressing of the corpse and the lining of the grave with highly visible materials.Footnote25 The agency of the medieval dead has been explored via the medium of saintly relics, but also through the dangerous and disruptive dead, the belief in medieval ‘revenants’ (reanimated corpses) and how this impacted on burial practices (discussed below).

Deeper reflection on materiality has stimulated innovative work on post-burial practices, including grave opening, reuse and deliberate destruction, together with the curation of human remains and grave furnishings.Footnote26 The growing literature on post-burial practices in Viking and Anglo-Saxon archaeology focuses principally on themes of memory, personhood and the commemoration of ancestors. In a late-medieval context, post-burial practices have been explored through the curation of human remains in charnel houses and practices of secondary burial (‘translation’) in churches and cemeteries.Footnote27 For example, the deliberate retention, storage and curation of crania and long-bones have been confirmed by recent study of the extant 13th-century charnel house at Rothwell (Northants) and excavations at St Peter’s, Leicester.Footnote28 The preservation of bones aimed to safeguard Christian resurrection, while the practice of collective charnelling facilitated the deliberate ‘forgetting’ of individual dead.Footnote29 Previously regarded as functional, post-depositional disturbances, medieval post-burial practices have been reframed as spiritual strategies connected with commemoration and the belief in purgatory.

Medieval burial archaeology retains a strong interest in the integral connections between mortuary practices, religion and concepts of the afterlife. In contrast, the study of prehistoric burial tends to emphasise questions about the living, and early medieval burial archaeology focuses more on memory of the dead.Footnote30 The theme of materiality has encouraged wider exploration in medieval burial archaeology of a range of spiritual beliefs beyond the formal religious doctrines of the Church. In discussing post-medieval death, Sarah Tarlow argues that burials serve as a prism for exploring parallel discourses around theology, science, folklore and society.Footnote31 This perspective is equally pertinent to medieval burial practices, which are increasingly understood as complex and sometimes contradictory spiritual strategies, ranging from the orthodoxy of ecclesiastical burials to the diversity of vernacular practices integrated with lived religion.Footnote32

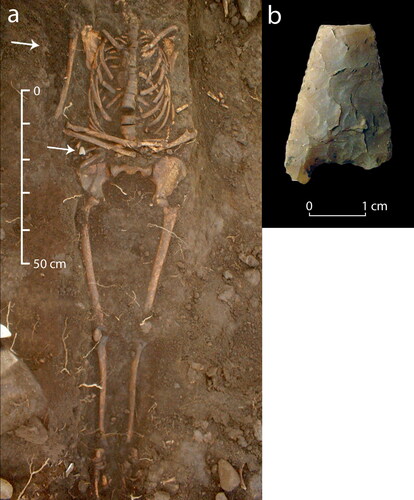

An excellent example is the Gaelic cemetery of Ballyhanna (Co Donegal, Ireland), which illustrates how a variety of spiritual strategies were compatible within a single community.Footnote33 The majority of graves date from 1200–1650: grave goods included objects commonly associated with Christian devotion and pilgrimage, including two paternosters and a scallop shell, but there were also objects associated with folklore, such as a prehistoric arrowhead buried in the hand of a young woman (). In Ireland, prehistoric lithics were associated with the Si, fairies or supernatural beings that were culturally associated with prehistoric monuments and artefacts. These objects were collected and curated from medieval to modern times, used for healing or kept in houses and farm buildings to protect humans and animals from harm.Footnote34 In this mortuary context, the prehistoric lithic can be interpreted as an apotropaic or healing object. Large numbers of white quartz pebbles were associated with the Ballyhanna dead: they occurred in association with 52 burials, and in 18 cases, were placed in the hand or near the hands, resting on the pelvis. White quartz pebbles are a medieval folk tradition associated particularly with burial in Ireland and Scotland, again regarded as healing or protective objects.Footnote35 What is striking in the case of Ballyhanna is that some burials contained both quartz pebbles and more orthodox devotional objects, including two women who were buried with a paternoster and scallop shell respectively. The Ballyhanna dead also demonstrated a broad range of body positions, including two adult women buried in a tightly flexed position, both of whom exhibited advanced tuberculosis. The flexed burial of a young adult male had his hands placed as if he were at prayer, with a quartz pebble located at his hip. Catriona McKenzie and Eileen Murphy conclude that subtle differences in burial treatment were used deliberately by families at Ballyhanna: ‘the living were personalising the burials of particular people’, possibly the most vulnerable, those with specific illnesses, or those who were especially pious.Footnote36

Fig 1 Protective objects placed in medieval graves included natural materials and curated objects such as prehistoric lithics. (a) A young adult female excavated at Ballyhanna, with a flint arrowhead lying near the left hand (not preserved). (b) Detail of the late-neolithic/early Bronze-Age arrowhead. Reproduced with permission from McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018; photos © Irish Archaeological Consultancy Ltd and Jonathan Hession; annotation by Libby Mulqueeny; Ballyhanna Research Project, National Roads Authority/Transport Infrastructure Ireland.

A QUESTION OF SCALE: FROM INDIVIDUAL LIVES TO THE GLOBAL MIDDLE AGES

The wider field of mortuary archaeology has turned towards the study of local, micro-scale traditions, prompted by methodological innovations in the scientific recording and analysis of skeletons that have increased awareness of variability in burial rites.Footnote37 The approach of archaeothanatology (anthropologie de terrain) was pioneered by the French physical anthropologist Henri Duday to examine the biological and social components of burials in combination, often revealing subtle patterning within single graveyards.Footnote38 It emphasises the taphonomy of the corpse and grave, taking factors of decay and deposition into account to reconstruct the burial context and position of the body. Applied in a medieval context, it is useful in identifying wrapping or shrouding of the body in the absence of surviving textiles or pins (evident through bilateral compression of shoulders and arms). It has also discerned localised patterns in the positioning of medieval corpses, for example in relation to their age. At Ballyhanna, neonates and infants were more likely to be placed in a non-supine position and younger children were more likely to be placed on their sides.Footnote39 This approach can also be used for close comparison of two or more cemeteries of a similar type. Eleanor Williams compared the burial customs of two monasteries of the Cluniac order, at Bermondsey Abbey (London) and Notre Dame, La Charité-sur-Loire (Burgundy); burials at Bermondsey were dated 1100–1430, while those at Notre Dame were mid-11th century to mid-13th century. Williams concluded that the French monastery was more consistent in its mortuary rites than its English counterpart, including in the placement of limbs and the wrapping of the corpse.Footnote40 Even amongst the most orthodox monastic orders, we find local variation at the micro-scale.

A shift towards the study of individual burials has been driven by advances in scientific techniques including the study of isotopes, ancient DNA and the human microbiome (coprolites and dental calculus), which allow investigation of life histories. These methods are used to reconstruct the life experience of individual medieval people. For example, the presence of exotic lapis lazuli pigment in the dental calculus of a woman from Dalheim (Germany), 45–60 years of age and dating to the 11th–12th century, has been interpreted as evidence that she was a nun involved in manuscript production.Footnote41 The study of specific individuals has also been used to inform understanding of the experience of medieval disability, disease and social relationships around dying. This trend is exemplified by the ‘bioarchaeology of care’ approach, a framework for assessing the evidence and possible health-related care of individuals with pathologies that indicate long-term disease and disability. Medieval case studies include a male skeleton excavated from the leper hospital of St James and Mary Magdalene, Chichester (West Sussex), and two women from medieval Poland, one with leprosy and the other with gigantism (all dating to the 12th–14th century).Footnote42

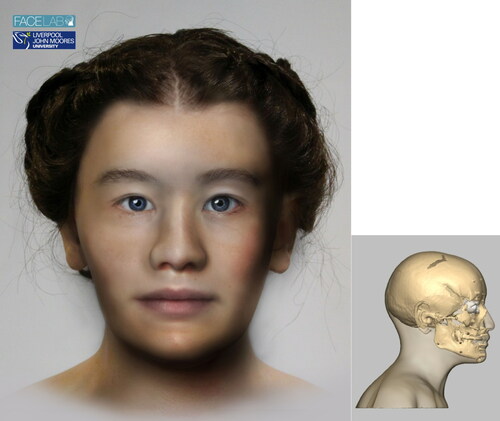

Osteobiography has emerged to complement the more quantitative approaches of osteology. It focuses on the intimate scale of the individual, and is often more qualitative and theoretically engaged, prioritising social questions alongside the study of health and disease.Footnote43 Osteobiography offers a more humanistic framework to consider how people experienced their lives, including their health, diet, geographical origins and mobility, genetics and appearance, incidents of violence and ill health, ageing and death.Footnote44 It is regarded as a distinctive genre in bioarchaeology, likened to the process of writing historical biographies or microhistory, in that proxy evidence of different types and scales is layered to achieve a narrative.Footnote45 While the starting point is the case study of a specific individual, it can also be used to inform historical understanding of a much broader range of social issues and relationships. An excellent example is the study of three burials from medieval Trondheim, Norway: three skeletons dating to the 13th century were examined to reconstruct birthplace, mobility, ancestry, pathology and physical appearance.Footnote46 The skeletons were chosen to represent ordinary people buried in the Nidaros graveyard, dated 1175–1275, all aged in their 20 s or 30 s. The evocative names given to the case studies convey their most significant stories: ‘the girl who travelled far’ (), ‘the woman of central European descent’ and ‘the man who needed surgery’. Their osteobiographies emphasise the diversity and mobility of the medieval urban population, with around 40% of Trondheim’s population originating from outside the city. Isotopic analysis and assessment of mitochondrial DNA suggests that the two women had travelled considerable distances to Norway, one potentially from north-western Russia and the other from the Alps. The man is likely to have been born in Norway but not in Trondheim; he had undergone trepanation, a highly skilled surgery, and the first case to be recognised from medieval Norway.

Fig 2 Craniofacial reconstruction of female skeleton from the Nidaros graveyard, Trondheim, representing a complex immigrant history. Analysis of oxygen isotopes suggests she was possibly born in north-western Russia, while her mitochondrial DNA indicates her mother may have been from southern or central Europe. Her cranial morphology shows Mongoloid-type traits, suggesting an Inuit or Asian influence. Image reproduced with permission from Hamre et al Citation2017; © Face Lab at Liverpool John Moores University.

Osteobiographies yield intricate narratives of ordinary medieval lives in more detail than historical sources could ever allow.Footnote47 The individual scale of analysis highlights the active agency of women, whether as craftspeople, or as economic and spiritual agents.Footnote48 The authors of the Trondheim osteobiographies explore the heterogeneity of the medieval urban population and the social and cultural barriers that migrants would have traversed, following European trade routes to the Norwegian city or attracted as pilgrims seeking healing from the local saint, Olav. Osteobiographies hold the potential to move from micro to macro-scale, offering new perspectives on the ‘global Middle Ages’—medieval connectivity and interaction on a global scale, including the mobility of people, materials, objects, ideas and diseases.Footnote49

SPECIAL DEATHS: INFANT AND CHILD BURIALS

Not long ago, children were regarded as a neglected topic in mortuary archaeology.Footnote50 Gender and feminist archaeology has prompted closer attention to family relationships, domestic life and female agency.Footnote51 These social questions also accelerated bioarchaeological research on children, while the theoretical model of the life course served as the catalyst in uniting social and bioarchaeological perspectives on ageing.Footnote52 The life course contextualises individual stages of life, such as infancy, within the broader continuum of the human lifetime, and places it within the cultural context of age cohorts, generations, and social domains including the family, household and beliefs surrounding death and the afterlife.Footnote53 The exceptional treatment of children’s graves is emerging as a common pattern across medieval Europe, despite the general under-representation of infant and child graves in medieval cemeteries.

In parish church cemeteries in Britain, infant and child graves were selected most often for the inclusion of grave goods including dress accessories, domestic objects and amulets for healing and protection, such as beads and crosses, and apotropaic materials such quartz, jet and animal teeth.Footnote54 At St Clemens in Copenhagen (dated c 1000–1536), small polished stones were found placed on the chest or arms of children, interpreted as amulets placed as emotional acts or ‘special signs of affection’.Footnote55 Distinctive containers were sometimes used for perinatal infants, including objects associated with the household, such as baskets, chests or even roof tiles, in northern Italy, recalling pre-Christian Roman rites.Footnote56 Children’s graves were often distinguished spatially: in Scandinavia, they were buried close to the walls of the church or in the western part of the cemetery; similarly, in Britain they clustered near the porch or near the font within the church, or around particular features in the cemetery.Footnote57 At the village of Wharram Percy (N Yorkshire), an area to the north of the church was reserved for pre-term infants, neonates and infants aged up to one year, interpreted as a special zone for those not yet weaned.Footnote58 There were also nuances in the positioning of child corpses in the grave: a comparative study of skeletal remains from Taunton Priory (Somerset), St Oswald (Gloucester), and St Gregory (Canterbury, Kent), concluded that non-adults were placed most commonly in a supine position with arms at their sides, in contrast with adults, who were generally arranged with their arms across their stomachs.Footnote59 Infants were sometimes placed on their sides in a flexed position, interpreted as a natural sleeping posture; for example, a 14th–15th-century burial at Poulton (Cheshire) and numerous examples at St Rombout’s, in the city of Mechelen, Flanders (Belgium).Footnote60

The singular treatment of infant and child graves is often interpreted as an expression of parental grief. Aubrey Cannon and Katherine Cook have challenged this assumption, arguing that material evidence may reflect ‘coping strategies’ in response to infant death rather than grief.Footnote61 They suggest that the segregation of infant burials was a way of reducing encounters with their graves, a means of ‘moving on’ emotionally, rather than prolonging grief. In a late-medieval context, archaeologists have the benefit of historical sources to contextualise understanding of parental responses to infant death, in particular the miracle stories associated with saints’ tombs.Footnote62 Ideas about the afterlife affected burial location: infant and child graves were often placed prominently to benefit from more frequent intercessory prayers. Nevertheless, we should perhaps evaluate the special treatment of infant and child burials more critically. Does emotion fully explain the range of distinctive funerary treatments? How did beliefs about the afterlife affect behaviour towards the child corpse and grave? Could there be other factors in play, such as cultural ideas about the ontological status of the infant body? In other words, what did infant and child burials do?

This question is pertinent to understanding multiple burials, which in medieval cemeteries of all types feature a high proportion of children and infants. For example, the eight double burials at Wharram Percy all involved children. At St Clemens, Copenhagen, 23 of 25 multiple burials involved children, comprising either two to three children buried together, or an adult buried with a child placed close to their chest or neck. A survey of multiple burials in medieval Irish cemeteries confirmed that 50% of examples comprised juveniles interred with adults.Footnote63 Two different processes can be discerned in multiple burials: 1) simultaneous interments, with two or more children interred together (), or one or more adults buried with children; and 2) burials separated in time but reusing the same plot, often involving infants or young children superimposed on the earlier grave of an adult. What motivated mourners’ selection of this burial rite for children—what did multiple burials do? Were they linked to ideas about the afterlife, perhaps the belief that children needed adult protection and guidance when entering the terrifying realm of purgatory? This may have been particularly pertinent in cases where the child had died before they were able to walk unaided, given strong belief in the material continuity of the body in purgatory.Footnote64 Some insight to cultural beliefs about death may be found in medieval ghost stories: where children occur, they are represented as innocent souls seeking assistance in purgatory.Footnote65 The adults included in these multiple burials may have been intended to protect children in the afterlife. Conversely, was burial with children regarded as efficacious to adults? In a late-medieval context, children aged under two were regarded as ‘holy innocents’ and may have served as mutually protective companions to adults journeying through purgatory.Footnote66 We are familiar with medieval belief in the healing and protective power of saints’ bones and relics; is it possible that other categories of the medieval dead, particularly infants, were sometimes perceived to carry positive agency?Footnote67

Fig 3 Multiple burial of two children in the cemetery west of the priory at St Gregory, Canterbury. Both children were approximately two years old at death and the grave dates to the 12th century. © Canterbury Archaeological Trust; reproduced with permission.

The Church taught that prior to baptism, infants were regarded as liminal beings that carried the taint of Original Sin. It was believed that the souls of unbaptised foetuses were confined to Limbo and their corpses were prohibited from burial in consecrated ground, recorded by Durand of Mende (c 1286), among others.Footnote68 However, archaeological evidence confirms that local communities sometimes defied canon law by burying unbaptised infants in consecrated ground. This is confirmed by the identification of burials of women who died in childbirth with the foetus buried in utero, and possible clandestine burials of perinatal infants located on the margins of cemeteries, with archaeological examples of both practices recorded in Britain, Ireland and Italy.Footnote69 The Irish cilliní, vernacular burial grounds reserved principally for unbaptised infants, are now understood to be post-medieval in date: they proliferated during the Irish Counter-Reformation movement.Footnote70 Local practices varied, with unbaptised infants permitted burial in consecrated ground in some regional and social contexts, whereas in others, dedicated burial grounds were established. By the 13th century, it was common to baptise infants within a few days of birth and emergency baptism could be undertaken by a layperson if the child was at risk; however, the church prohibited baptism of miscarried or stillborn infants. Miracle stories reveal that stillborn infants were taken to medieval shrines in large numbers to be temporarily revived for ‘emergency’ baptism, prompting the development of several hundred sanctuaries for miracle baptism in France, Belgium, Switzerland, southern Germany, Austria and northern Italy. Folk practices were employed to verify life; for example, the tiny corpses were warmed over hot coals and brought into the (cold) church, where a small goose feather was placed on the lips. By means of thermal lift, the feather moved briefly upward and was regarded as a sign of life. The infant could then be baptised and buried in consecrated ground—reassuring distraught parents that its soul would not languish in Limbo. One of the most popular sanctuaries was the shrine of the Holy Virgin in Oberbüren (Switzerland), where 250 late-medieval infant burials have been excavated, most premature and likely the recipients of miracle baptism, tightly packed together in burial rows or pits.Footnote71

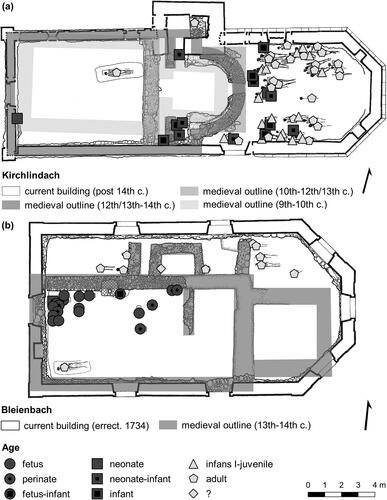

Barbara Hausmair highlights the importance of contextual understanding of social attitudes towards the unbaptised dead. The location of infant graves was influenced by the sacred topography of the cemetery, ideas about the afterlife and the value placed on young children by specific communities. She shows significant variations between three cemeteries in Switzerland and Austria, demonstrating local differences in what was perceived to be the most efficacious space for salvation and in the age groups of infants that were permitted burial inside churches (). An infant cemetery was excavated at St George on Mount Göttweig (Austria), consisting almost entirely of premature and neonate children. It was sited prominently on the mountain’s highest elevation and Hausmair concludes that the choice of site reflects the ambivalence with which unbaptised infants were perceived. The cemetery was highly visible, but also secluded and contained: its elevated position brought these infants closer to heaven, while maintaining physical distance from the Christian community and its dead, perhaps a compromise between spiritual intercession and emotional closure.Footnote72

Fig 4 Contrasting treatment of infant age groups buried in Swiss churches. Bottom: At Bleienbach, (unbaptised?) foetuses and perinates were present and clustered towards the north-western corner of the nave. Top: At Kirchlindach, only older infants were present inside the church, clustered towards the chancel. Unbaptised infants were excluded from the church and baptised infants were buried in a privileged position near the high altar. Reproduced with permission from Hausmair Citation2017. Distribution map: Barbara Hausmair, background: © Archäologischer Dienst des Kantons Bern.

‘DEVIANCY’: THE RISE OF THE RESTLESS DEAD

The study of medieval burial has recently emphasised violent death, ritualised treatments of the corpse and all aspects of deviant death.Footnote73 The term ‘deviancy’ is inherently problematic, given its pejorative connotations in contemporary usage, often suggesting sexual perversion. It signals negative value and subjective judgement, implying that non-normative rites of burial were deliberately selected to stigmatise the dead.Footnote74 Nevertheless, the term is used by archaeologists to refer both to social categories of individuals that received alternative burials rites (such as executed criminals and unbaptised infants) and to graves that are non-normative in terms of location, construction, or positioning of the body. More rigorous consideration of cultural context and terminology has been called for, to distinguish ‘minority’ and ‘atypical’ burial rites from practices that may be regarded as truly deviant within a medieval Christian context;Footnote75 in other words, funerary treatments that may have been intended to convey disrespect, punishment, or humiliation of the dead. It is also essential to evaluate archaeological context and grave taphonomy when interrogating specific non-normative practices such as prone burials.Footnote76

What precisely do we mean by ‘deviancy’ in a late-medieval burial context? The widest definition encompasses all burial rites outside those prescribed by the Church, including non-normative practices within consecrated spaces, such as prone or staked burials and post-burial practices, including translated burials. However, it may be useful to exclude ‘atypical’ rites: those that occur relatively frequently within consecrated ground, such as oddly positioned or misaligned burials and multiple burials, together with rarer rites such as heart burials, practised by an elite minority. Mass burials of famine and plague victims in consecrated ground could also be excluded, for example those excavated at the hospital of St Mary Spital (London) and Thornton Abbey (Lincolnshire).Footnote77 Burial customs associated with judicial execution may also be regarded as ‘atypical’ rather than deviant in a late-medieval context. From the 12th century onwards, executed criminals in England were buried in consecrated ground within hospitals, monasteries and parish churches. At St Margaret in Combusto (Norwich), a documented place of burial for hanged felons (12th–15th century), excavations revealed that 40% of interments were part of multiple burials that included prone individuals, dumped in the grave face down.Footnote78 These non-normative burial rites were expedient measures tolerated within consecrated ground.

A recent study of prone burials in Germany, Austria and Switzerland examined 95 examples from 60 sites.Footnote79 Multiple correspondence analysis identified common patterns, including the over-representation of males and the predominance of adults, particularly young adults; the only examples of prone child burials occurred in the context of multiple burial with adults. A significant difference was observed in the spatial context of prone burials dating to the high medieval period (c 1000–1250) versus those of late-medieval and post-medieval date. High medieval, prone male burials were often located in the most prestigious holy spaces; for example, a prone male was interred close to the portal of St Peter’s church on the Kleiner Madron near Flintsbach (Bavaria), accompanied by four coins, polished stones and a Mithraic gem. The authors conclude that in central Europe during the High Middle Ages, prone burial may have been intended as a pious expression of religious humility, whereas prone burials dating to the late-medieval and post-medieval periods were more likely to be sited in marginal spaces, and therefore may have conferred disrespect.

In a late-medieval Christian context, a tighter definition of deviancy might focus on burials outside consecrated ground. This includes the mass graves of the battle dead, such as Towton (Yorkshire, 1461), Visby (Gotland, Sweden, 1361) and Aljubarrota (Portugal, 1385).Footnote80 However, efforts were made to move the battle dead to consecrated ground: some of the dead from Towton were exhumed 20 years after the battle, while those from Bosworth Field (1485) were moved to Dadlington Church in 1511.Footnote81 These translations demonstrate the high social value placed on the battle dead and the spiritual imperative of resting in consecrated ground. In what circumstances were individuals deliberately interred outside consecrated ground? The most common practice is infant burial in domestic or settlement contexts, occurring across Europe and typically interpreted as evidence for infanticide or the hasty disposal of the unbaptised. Relatively common in central Europe are infant burials interred in clay pots within houses, generally interpreted as a form of surreptitious disposal.Footnote82 In England, domestic burials of infants are more often found dug into the exterior walls of houses and covered with subsequent floor deposits, confirming that the buildings were still occupied. These infants ranged from birth age, to 3–6 months, and some at least would have been baptised. What did domestic infant burials do, in a medieval Christian context? Burial of an infant within a domestic dwelling may have been a deliberate ritual act, one possibly connected with women’s rites of fertility and the protection of future unborn children.Footnote83 Such burials may have carried positive agency, valued by mothers for their emotional resonance and magico-religious power.

Archaeologists are becoming more alert to medieval burials in un-consecrated ground, recently discussed in relation to central Europe, Croatia and Ireland.Footnote84 By the 12th century, burial outside the hallowed ground of the churchyard was limited to mortal sinners and non-persons (ie those outside the Church). It was regarded as a punishment more serious than execution, because it prevented the completion of a ‘good death’ and rendered the dead a spiritual outcast for eternity.Footnote85 How then, might we account for such burials? Were these heretics, social outcasts, victims of violence or famine, or those too poor to pay the burial fee? In some cases, might this unorthodox practice represent a form of religious dissent? Several late-medieval burial grounds have been excavated in Ireland that were not associated with churches, including Athboy (Co Meath) and Mullagh (Co Longford). These burials followed Christian conventions: they were aligned E/W, often shrouded and arranged in formal rows. The remains of three adult females and an infant were discovered in a 13th-century midden at Swords (Co Dublin). One was aligned E/W and the head was marked by pillow stones, confirming a degree of care in placing the corpse.Footnote86 In England, one disturbing example shows casual or disrespectful disposal of human remains, or possibly even racially motivated murder. In 2004, the remains of six adults and 11 children were discovered in a well shaft in Norwich, located next to the precinct boundary of the College of St Mary in the Fields. Dating by radiocarbon and pottery placed the burials in the 12th–13th century and two-thirds of the group were aged under 20 years at death, including one adolescent, two children aged 10–15 years, and five children below the age of five.Footnote87 This highly unusual burial context may represent the disposal of victims of famine or disease, or potentially violence against the Jewish population of Norwich. Ancient DNA analysis carried out for a BBC documentary in 2011 suggested they could be Jewish, and in 2013, the remains were given Jewish burial.Footnote88

Even graves identified as possible ‘revenants’ are found in consecrated ground: revenants were believed to be re-animated corpses that returned from the grave with malicious intent.Footnote89 Documented stories of corporeal zombies are relatively rare in medieval western Europe, perhaps a few dozen and all from northern regions (England, Iceland, Germany), in contrast to thousands of tales from across Europe of incorporeal ghosts.Footnote90 Recorded remedies for revenants included decapitating or burning the corpse, or binding the coffin with locks and chains. Medieval graves that contained padlocks, manacles, detached skulls, or charred materials have been discussed as potential candidates for revenants.Footnote91 However, stories of revenants in northern Europe were documented during a discrete period, c 1130–1230, coinciding with a time of significant change in theological and medical attitudes towards the corpse. Winston Black has argued that belief in revenants peaked when scholastics were most anxious about the fate of the human body after death, and declined as the doctrine of purgatory crystallised, providing explanation for how the body and soul would be re-united.Footnote92 In eastern Europe, vampire stories emerged in the 11th to 13th centuries, impacting on burial practices during the transition to Christianity and the change from cremation to inhumation rites. Some prone burials excavated in eastern Germany, Poland, the Czech Republic and Slovakia exhibit preventative measures including decapitation, staking, nailing and interment with a sickle across the throat, possibly indicative of belief in vampires.Footnote93

Burials that were deliberately dismembered and disposed of outside consecrated ground are the most persuasive candidates for deviancy, ie they were subjected to mortuary treatments that conveyed stigma or punishment within the context of medieval Christian beliefs. Such examples are usually interpreted by archaeologists as the victims of murder or massacre, such as a human torso found in a ditch at Jedburgh Abbey (Scottish Borders). The articulated rib cage was deposited together with several high-quality objects: a small comb and a seal or pendant, both of walrus ivory, a horn buckle and a whetstone. The ditch was then infilled in a single event, dated by a coin of Henry II to the late 12th century.Footnote94 Dismembered human remains were found deliberately deposited in several contexts (outside churchyards) in the extensively excavated Hungarian village of Kána, located in the 11th district of Budapest. The most curious was a pit dug into an external oven, in which various body parts were interred and then immediately backfilled.Footnote95 The presence of three skulls allowed the identification of the remains as female. Some of the body parts were still articulated at the time of burial, including a torso, indicating interment before full decomposition had occurred.

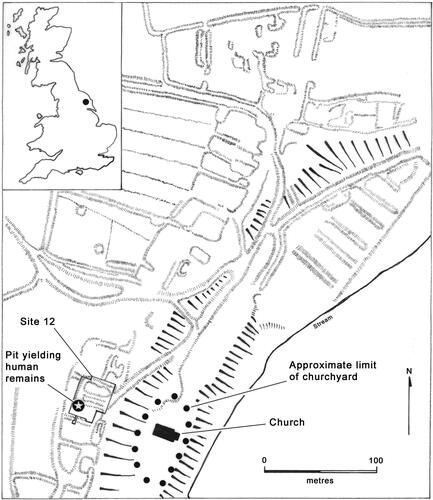

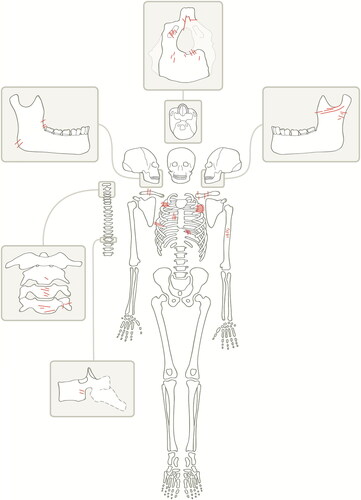

Comparison can be made with a disconcerting discovery from the Yorkshire village of Wharram Percy ().Footnote96 A pit from a domestic context produced an assemblage of 137 disarticulated human bones. The remains were considered by excavators in the 1960s to be Romano-British in date, because it was inconceivable that corpses of medieval Christians could have been treated in this way. However, new radiocarbon dating confirms that they are in fact late-medieval in date. They showed marks of sharp force trauma, including knife-marks and chop-marks, as well as signs of low-temperature burning and perimortem breakage. They represent a minimum number of ten individuals, comprising both males and females, and ranging in age from two-four years up to >50 years at death. Strontium-isotope analysis confirmed that the dead were of local origin, rather than outsiders. The radiocarbon dates confirmed that the bones represent individuals who died over an extended period, possibly a century, and focusing on the 11th–13th centuries. This macabre assemblage cannot be explained as a single gruesome episode or the aftermath of a catastrophe. The authors consider two potential interpretations based on historical context: starvation cannibalism and efforts to quell the revenant dead. Some of the long bones were split in a manner consistent with marrow extraction, and there were signs of human tooth marks, possibly indicative of cannibalism. However, the knife-marks focus principally on the head and neck region; the lack of cuts below the chest area argues against the cannibalism interpretation, based on comparison with documented cases of (modern) starvation cannibalism. The absence of animal gnawing suggests that the bones were not left exposed but were instead curated or buried elsewhere, before being redeposited in the pit. The authors conclude that the evidence supports an interpretation of laying revenants to rest.

Fig 5 Plan of the medieval village of Wharram Percy, showing location of pit complex yielding human remains, associated with the western row of buildings and separated from the church by a steep escarpment. Reproduced with permission from Mays et al Citation2017a.

Fig 6 Composite diagram showing distribution of cut marks in the human remains from Wharram Percy. The cervical vertebrae shown inset come from a single individual, and the cut marks on the occipital bone shown inset also occur in one (different) individual. Reproduced with permission from Mays et al Citation2017a.

Recent archaeological research has made atypical, minority and deviant burial practices more visible but there has been relatively little critical reflection on what they may tell us about the social relations of medieval death. Did deviant mortuary practices constitute illicit acts, carried out in secret, such as the burial of infants in homes, or the disinterment and dismembering of human corpses? What were deviant burials intended to do? First, it is essential to refine our definition of ‘deviancy’ in a medieval Christian context. As argued above, Christian burial practices encompassed a broad range of atypical and minority burial modes that carried contextual social meanings; in some circumstances, even prone burials constituted spiritual strategies to signal pious humility.Footnote97 The term deviancy should be reserved for late-medieval burials outside consecrated ground, particularly those that have been deliberately dismembered. The fragmentation and display of corpses was deployed as post-mortem punishment to exclude, segregate or marginalise, for example in relation to judicial killing in the 10th–11th centuries.Footnote98 What do these strange cases tell us about the agency and ontological status of the medieval deviant dead: were they regarded as human or less than human, treated as deceased people, objects or ritual materials? Future work should evaluate the incidence and character of Christian burial in un-consecrated ground and under what circumstances it might have occurred.

NECRO-POLITICS: MEDIEVAL BURIALS AND PUBLIC ARCHAEOLOGY

The last decade has witnessed intense self-reflection on the relationship between archaeologists and the dead—how human remains are excavated, scientifically analysed, stored, displayed, interpreted and visually reconstructed.Footnote99 The ethical challenges of burial archaeology stem from the complex relationships of graves to religion, ethnicity, colonialism and minority rights, in addition to the moral rights of the dead themselves.Footnote100 To many outside archaeology, graves possess a semi-sacred quality—the protection of human remains is widely perceived as an ethical imperative, regardless of whether the cemetery is consecrated. Conversely, graves and funerary monuments are desecrated in acts of violence or terrorism connected with religious or ethnic hatred, such as the ongoing attacks on Jewish cemeteries globally. The agency of the dead is mobilised by the diverse concerns of the living. This final section examines two current areas of ethical debate where medieval burial archaeology engages with public audiences: ‘celebrity bodies’, ie the burials of named historical individuals; and graves connected with living religions.

The public appetite for ‘celebrity bodies’ was demonstrated emphatically by the discovery of the remains of Richard III in 2012, the final Plantagenet king of England, who died at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, aged 32. Despite his notorious reputation, the discovery of Richard III prompted an outpouring of local and national pride and attracted an unprecedented audience for medieval archaeology.Footnote101 His remains were reburied in Leicester Cathedral in 2015, accompanied by international press coverage and pomp befitting a royal funeral, complete with a celebrity descendant officiating (Benedict Cumberbatch). The ‘Richard III effect’ stimulated economic growth and reputational gain for the city, its cathedral and university—and was even credited with improving the performance of the local football team.Footnote102 Public enchantment with Richard III can be contrasted with the reception of an earlier discovery: the remains of Anne Mowbray, Duchess of York (d 1481), discovered in 1964 in a vault beneath the Franciscan nunnery of the Minories in Aldgate, London.Footnote103 Anne died aged nine, and her body was well-preserved in its lead coffin, with remarkable survival of textiles, soft tissues and tresses of her auburn hair (). Her direct living descendants objected to the scientific study of her remains and demanded immediate reburial; questions were raised in Parliament and the legality and historical value of the exercise were challenged.Footnote104 The forensic investigation ceased, and Anne Mowbray’s remains were reburied reverently in Westminster Abbey, accompanied by international press coverage. The sensitivity of this case may relate to Anne’s young age and her well-preserved remains—the recognisable corpse of a child, rather than a desiccated skeleton. This factor also influenced public response to the ‘St Bees Man’, one of the best-preserved archaeological bodies ever discovered, excavated in 1981 at St Bees Priory church (Cumbria). The late 14th-century corpse was quickly reburied in its original lead wrapping, due to local sentiment that he should be returned to rest in peace.Footnote105

Fig 7 Opening the lead coffin of 9-year-old Anne Mowbray (d 1481) in 1964, in the presence of archaeologists, conservators and pathologists from the London Museum, Guy’s Hospital and Hammersmith Hospital.

© Museum of London; reproduced with permission.

In contrast, there was no public outcry raised in relation to the scientific analysis of Richard III. Since the discoveries of Anne Mowbray and the ‘St Bees Man’, public attitudes towards dead bodies have been reshaped by popular media, including factual television programmes on archaeology and procedural crime dramas focusing on forensic investigations. In fact, the ethical concerns raised around Richard III were voiced primarily by archaeologists, who were uncomfortable with their discipline being used to manufacture celebrity bodies. Archaeologists object to the idea of ‘monarch-mining’, the search for royal bodies that sensationalises the medieval dead and fails to consider the moral rights of deceased individuals to remain undisturbed. We challenge cases like Richard III as fetishizing the individual dead and divorcing them from the wider interpretative context of medieval society. As professionals, we must consider what we actually learn from the study of celebrity bodies.Footnote106 These concerns emphasise how the social ‘value’ of medieval burials is different for respective stakeholders—what do celebrity burials do? For the Richard III Society, who initiated the search, there was social value in honouring Richard III and challenging the negative stereotyping attached to his memory. The archaeologists involved saw academic value in better understanding medieval Leicester and the friary church associated with his burial.Footnote107 The wider public felt a visceral emotional connection to a long-dead king, while the local community relished their brush with medieval celebrity and appreciated its economic value. Some subsequent research on Richard III has moved beyond the aim of ‘proving’ his identity to contextualising his remains. Jo Appleby has interrogated his life course, exploring how he consumed high-status foods to negotiate his royal personhood.Footnote108 In retrospect, some significant research questions have been directed towards Richard III, but they were not articulated prior to his disinterment. Unless the preservation of celebrity bodies is threatened, archaeologists will continue to debate the ethical propriety and research value of their excavation.

Archaeologists have also raised ethical concerns about craniofacial reconstructions based on excavated skulls, arguing that such depictions may constitute voyeuristic intrusions on past lives.Footnote109 Advocates of osteobiography acknowledge that there are ethical risks in the selection of individuals who effectively deputise for an entire place or time- period. On what basis should subjects be chosen—to be typical, alternative, familiar or challenging?Footnote110 The osteobiography of a medieval Dutch boy has been criticised for failing to consider how archaeological narratives intersect with political issues such as national identity. The ten-year old boy’s grave was excavated at the church of St Catherina, Eindhoven, and dated to the 13th century. A silver Venetian groat was found on his chest, possibly a pilgrim sign for Saint Mark’s, Venice. The boy’s DNA suggests possible links to Mediterranean and north-western European population groups and his palaeopathology confirms that he suffered chronic ill health during his short life. But the visual reconstruction of ‘Marcus’ shows a white, golden-haired boy glowing with health: ‘a personification of Dutch-ness’.Footnote111 Archaeological ethics include the need for critical awareness of the political value of medieval burials, for instance in relation to discourses around ethnicity and migration. Non-specialists may not fully understand that craniofacial reconstructions do not constitute historical realities; they are interpretative narratives that inevitably reflect the assumptions of those who created them. Nor can we hope to resurrect the essence of an individual personality, in the case of medieval celebrity bodies. For example, one might doubt the claim that the reconstruction of the face of Robert the Bruce (d 1329), based on a skull from Dunfermline Abbey (Fife), is key to understanding the ‘status, power and resilience as a leader’ of ‘the warrior-king and man beneath the armour’.Footnote112

The study of medieval burials frequently brings archaeologists into dialogue with living religions. In England, the excavation of medieval graves located on ecclesiastical land (ie churches still used for worship), comes under the jurisdiction of ecclesiastical rather than secular law. The Church of England can withhold permission or place restrictions on archaeological access; for instance, permission was given to excavate burials at a medieval leprosarium (leper hospital) in Oxford but stipulated that recording and sampling of articulated skeletons must be carried out in situ. Removal of disarticulated skeletal remains was allowed for scientific study and they were subsequently re-interred, accompanied by a Christian service.Footnote113 Heritage organisations collaborated with the Church of England in 2017 to make recommendations for best practice in dealing with human remains excavated from Christian burial grounds, stating that a balance should be achieved between ‘ethical considerations derived from Christian theology against the recognised legitimacy of scientific study of human burials, whilst being aware of public opinion regarding disturbance of, and scientific work on, human remains’.Footnote114

The excavation and scientific study of medieval Jewish burials have brought archaeologists into conflict with Orthodox Jewish beliefs. In the 1980s and ‘90 s, excavations took place at medieval Jewish cemeteries without understanding the ethical implications of the Halacha, the Jewish law that prohibits disturbance or physical examination of the dead. In Spain, excavations were halted by protestors and skeletal remains were re-interred without study.Footnote115 Similar tensions occurred at Jewbury in York in the early 1980s, when the Home Office eventually agreed to the Chief Rabbi’s demands for the reburial of excavated skeletons before they were fully studied.Footnote116 An ethical approach to medieval burial archaeology requires the beliefs of descendent communities to be prioritised over the research objectives of secular heritage. Here, lessons may be learned from ethical methodologies developed for the study of Holocaust sites, where appreciation of Jewish Halacha Law and the profound, ongoing sensitivities surrounding such sites, has led to an emphasis on non-intrusive archaeological methodologies.Footnote117

It is vital for research designs to incorporate an ‘ethical epistemology’,Footnote118 to reflect carefully on ethical questions concerning the dead before study begins, including appropriate engagement with descendent and local communities, beyond the emphasis on ‘living family members’ that is stipulated in current guidelines.Footnote119 Medieval burials and funerary landscapes continue to inform perceptions of place and local identity today, embodying a sense of collective memory and immortality, regardless of family connections or religious beliefs.Footnote120 There is potential for ethical complexity or conflict in dealing with medieval burials associated with any living religion or descendent community. This includes world religions, neo-paganism and local ‘heritage communities’, who feel a particular emotional connection to burials in their locality (eg ‘St Bees Man’).

CONCLUSIONS: THE MIRROR OF THE MEDIEVAL PAST

Medieval burial archaeology has experienced a paradigm shift: whereas medieval graves were previously characterised as static reflections of the social order, they are now perceived as an active, complex and participative part of communities. Mortuary analysis has moved to the small-scale, with social and scientific approaches working holistically to reveal variation and specificity at the level of the individual person and the local community. While acknowledging the importance of the local and the micro-scale, it is essential that medieval burial archaeology also keeps sight of the ‘bigger picture’, making comparisons across space, time, and disciplinary boundaries. Large-scale comparative studies are urgently needed to map diachronic and regional patterns across medieval Europe and to identify the range and frequency of normative and non-normative rites.Footnote121 Interdisciplinary and comparative perspectives offer untapped potential to yield new insights into medieval death, such as the connectivity of the global Middle Ages and contestation in world religions. Local variations can be situated within this broader canvas of mortuary practices, to better understand how ‘deathscapes’ constructed a sense of place and negotiated relationships between communities of the living and the dead.Footnote122

Recent approaches have revealed the agency of the family in subtly differentiating individuals and age groups (particularly infants and children) through the location and construction of the grave, positioning of the body and the placement of apotropaic objects. The agency of the dead, especially the deviant dead, is now a question of acute importance to archaeologists, together with the potential of their graves to be socially active, to do something. The medieval corpse was perceived to hold either positive or negative agency, determining whether those preparing the burial aimed to assist or hinder the dead in their transition to the afterlife. So, ‘what did medieval burials do’? The examples examined here can be understood as ‘spiritual strategies’, whether to convey the piety or memory of the Christian dead, to enable their healing or transformation in purgatory, or to ensure their salvation and resurrection. Conversely, practices such as dismemberment or burial in un-consecrated ground were strategies intended to obliterate and exclude the dangerous or marginalised dead from the Christian community for eternity. Infant graves served as emotional expressions and coping strategies for grief, but their common occurrence in domestic contexts and multiple burials may suggest that they held protective as well as affective power. Burial practices were informed by multiple discourses on the medieval body and engaged with Christian theology, lived religion, regional folklore and scholastic medicine.Footnote123

Archaeologists currently place highest research ‘value’ on the deaths of the marginal and the subaltern in medieval life, prioritising the study of infants, children, the diseased and impaired, and all aspects of the non-normative. Would medieval people have identified these same deaths—and death rituals—as the most significant to them? To what extent are these trends in archaeological interpretation a projection onto the past of our own contemporary cultural concerns? An ethical epistemology requires us to understand how we construct archaeological knowledge about the medieval dead and how it changes according to the questions that we ask. Feminist and gender scholarship drew attention to women and children, prioritising themes such as diversity, equality, care-giving, healing and parenting.Footnote124 Post-processual archaeologies highlighted the body and materiality, prompting innovative approaches to post-burial practices and the ontological status of the corpse.Footnote125 The persistent allure of revenants is part of the wider fascination with zombies and the walking dead in contemporary popular culture, a theme which is said to emerge in times of social upheaval and collective anxiety in relation to disease, war and fear of ‘the other’.Footnote126

The growing emphasis on biographical narratives in burial archaeology also reflects contemporary social concerns. Melanie Giles and Howard Williams observe that biographies are a vehicle for archaeologists to negotiate their own identities in relation to the dead. The medieval dead become a mirror for our own time and our own life histories, a means to explore gender and personhood, ageing and disease, grief and generational relationships. They also remind us that mortuary archaeology is a form of public archaeology: archaeologists are mediators who construct narratives about the medieval dead for consumption by the living.Footnote127 The model of ‘burial archaeology as public archaeology’ promotes reflexive collaboration with stakeholder communities who may be motivated by different questions and beliefs about the medieval dead than those held by archaeologists. To fully engage with public audiences and to represent the entirety of medieval society, medieval burial archaeology will need to reconsider the place of the orthodox and privileged dead in our scholarship. The social archaeology of medieval burial is shaped by what we value and the questions that we ask: the voices from the cemetery are as much our own, as those of the medieval dead.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Sarah Semple for inviting me to reflect on recent developments for a keynote to the Society for Medieval Archaeology conference in 2018; Karen Dempsey and Mary Lewis for their helpful comments on the draft text; three anonymous reviewers for their insightful feedback; and Barbara Hausmair, Eileen Murphy and Bruce Watson for help in obtaining images.

Notes

2 Klevnäs Citation2016a.

3 Fahlander Citation2020.

4 Jones Citation2017; Stutz Citation2016, 29.

5 Gerrard Citation2003.

6 Ariès Citation1981; Binski Citation1996; Rodwell Citation1996; Daniell Citation1997; O’Sullivan 2013.

7 Kieffer-Olsen Citation1993; Alexandre-Bidon Citation1998; Daniell Citation1997; Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005.

8 Ibid; O’Sullivan 2013.

9 Prigent Citation1996; Jonsson Citation2009; Dabrowska Citation2005; Haasis-Berner Citation1999; Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005; Højmark Søvsø and Knudsen Citation2018.

10 Valk Citation2001.

11 Ikäheimo et al Citation2020.

12 Thibodeau Citation2007.

13 Semple and Brookes Citation2020.

14 Lilley et al Citation1994.

15 Inskip Citation2018; Citation2016.

16 Eg Gilchrist Citation2008; Citation2012; Murphy Citation2011; Citation2017; Chapman Citation2016; Jensen Citation2017; Cootes et al Citation2021.

17 Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005.

18 eg Murphy and Le Roy 2008; Reynolds Citation2009; Dawson Citation2016.

19 Eg Schmitz-Esser Citation2020; Korpiola and Lahtinen Citation2015; Rollo-Koster Citation2016.

20 Redfern and Hefner Citation2019.

21 Renshaw and Powers Citation2016.

22 Fahlander and Oestigaard Citation2008; Stutz and Tarlow Citation2013a; Stutz Citation2016.

23 Robb and Harris Citation2013; Stutz and Tarlow Citation2013b; Renshaw and Powers Citation2016.

24 Williams Citation2006.

25 Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005; Jonsson Citation2009; Inall and Lillie Citation2020.

26 Fahlander Citation2021; Klevnäs Citation2016b.

27 Craig-Aitkins et al 2019; Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005, 194–99.

28 Crangle Citation2016; Craig-Aitkins et al 2019; Gnanaratnam 2009.

29 Farrow Citation2021.

30 Stutz Citation2016; Klevnäs Citation2016a.

31 Tarlow Citation2013.

32 Gilchrist Citation2020.

33 McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018; McKenzie et al Citation2015.

34 Dowd Citation2018.

35 Gilchrist Citation2020; Tarlow Citation2013.

36 McKenzie and Murphy Citation2018, 70.

37 Fahlander and Oestigaard Citation2008.

38 Duday Citation2009.

39 Murphy Citation2017.

40 Williams Citation2018.

41 Radini et al Citation2019.

42 Tilley Citation2017; Roberts Citation2017; Matczak and Kozlowski 2017.

43 Hosek and Robb Citation2019.

44 Eg Knüsel et al Citation2010.

45 Hosek Citation2019; Robb et al Citation2019.

46 Hamre et al Citation2017.

47 Robb et al Citation2019.

48 Radini et al Citation2019; Hamre et al Citation2017.

49 Holmes and Standen Citation2018.

50 Fahlander and Oestigaard Citation2008.

51 Eg the journal Childhood in the Past, est 2009; Murphy and Le Roy Citation2017.

52 Mays et al Citation2017b.

53 Gilchrist Citation2012.

54 Gilchrist Citation2020; Chapman Citation2016.

55 Jensen Citation2017, 207.

56 Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005, 77; Cootes et al Citation2021; Crow et al Citation2020.

57 Jonsson Citation2009, 153; Gilchrist Citation2012, 206–8.

58 Mays Citation2007, 86.

59 Dawson Citation2016.

60 Gilchrist and Sloane Citation2005, 155–6; Cootes et al Citation2021; Van de Vijver et al Citation2018: 271.

61 Cannon and Cook Citation2015.

62 Eg Aldrin Citation2015; Crow et al Citation2020.

63 Mays Citation2007, 85; Jensen Citation2017, 205; Murphy and Donnelly Citation2019.

64 Bynum Citation1995; Gilchrist Citation2012, 209.

65 Mays Citation2016.

66 Gilchrist Citation2012, 207–9.

67 Schmitz-Esser Citation2020, 615–33

68 Thibodeau Citation2007, bk I, ch 5.

69 Gilchrist Citation2012, 209; Crow et al Citation2020; Cootes et al Citation2021; Murphy Citation2021.

70 Ibid 2011.

71 Gutscher Citation2017.

72 Hausmair Citation2017; Citation2018.

73 Eg Murphy Citation2008; Gardeła and Kajkowski Citation2013; Damman and Leggett Citation2018; Betsinger et al Citation2019; Alterauge et al Citation2020.

74 Aspöck Citation2008.

75 Gardeła Citation2017; Vargha Citation2017.

76 Moilanen Citation2018.

77 Connell et al Citation2012; Willmott et al Citation2020.

78 Reynolds Citation2009, 233; Stirland Citation2009.

79 Alterauge et al Citation2020.

80 Knüsel Citation2014.

81 Curry and Foard Citation2016.

82 Gardeła and Duma Citation2013.

83 Gilchrist Citation2012, 219–23.

84 Alterauge et al Citation2020; Krznar and Tkalčec Citation2017; Shine and Travers 2012.

85 Bynum Citation1995, 204; Davis Citation2016; Schmitz-Esser Citation2020, 484.

86 Shine and Travers 2012; Brady and Kelleher Citation2000.

87 Emery Citation2010.

88 BBC News Citation2011, Citation2013; Sophie Cabot, pers comm.

89 Caciola Citation1996; Watkins Citation2010; Schmitz-Esser Citation2020.

90 Black Citation2016; Schmitt Citation1998.

91 Gilchrist Citation2012, 194–6; Gordon Citation2014.

92 Black Citation2016; Bynum Citation1995.

93 Alterauge et al Citation2020; Betsinger and Scott Citation2014.

94 Lewis and Ewart Citation1995.

95 Vargha Citation2017.

96 Mays et al Citation2017a.

97 Alterauge et al Citation2020.

98 Semple and Brookes Citation2020; Reynolds Citation2009.

99 Giles and Williams Citation2016.

100 Tarlow 2006; Sayer Citation2010; Stutz Citation2016.

101 Buckley et al Citation2013; Pitts Citation2014.

102 Shellard Citation2016.

103 Watson and White Citation2016.

104 Sayer Citation2010, 49–54.

105 Knüsel et al Citation2010, 272.

106 Klevnäs Citation2016a; Giles and Williams Citation2016; Hosek and Robb Citation2019.

107 Pitts Citation2014, 184–93.

108 Appleby 2019.

109 Renshaw and Powers Citation2016.

110 Hosek and Robb Citation2019.

111 Arts Citation2003; M'charek Citation2011.

112 Wilkinson et al Citation2019.

113 Griffiths and Harrison Citation2020, 45-6, 127.

114 Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Human Burials in England Citation2017, 3.

115 Colomer Citation2014.

116 Lilley et al Citation1994.

117 Sturdy Colls Citation2015.

118 Blakey Citation2008; Sturdy Colls Citation2015.

119 Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Human Burials in England Citation2017, 1.

120 Badone Citation2015.

121 eg Alterauge et al Citation2020.

122 Maddrell and Sidaway Citation2010.

123 Bynum Citation1995; Black Citation2016; Robb and Harris Citation2013; Gilchrist Citation2012; Citation2020.

124 eg Murphy Citation2011; Mays et al Citation2017b; Tilley Citation2017.

125 Fahlander 2016; Citation2020; Klevnäs Citation2016b.

126 Black Citation2016, 71.

127 Giles and Williams Citation2016.

Bibliography

- Advisory Panel on the Archaeology of Human Burials in England 2017, Guidance for Best Practice for the Treatment of Human Remains Excavated from Christian Burial Grounds in England, 2nd edn. Swindon: English Heritage and Church of England. Available online at: <www.archaeologyuk.org/apabe/pdf/APABE_ToHREfCBG_FINAL_WEB.pdf> [accessed 22 August 2021].

- Aldrin, V 2015, ‘Parental grief and prayer in the Middle Ages: religious coping in Swedish miracle stories’, in Korpiola and Lahtinen 82–102.

- Alexandre-Bidon, D 1998, La Mort au Moyen Âge. XIIIe-XVIe Siècle, Paris: Hachette Littératures.

- Alterauge, A, Meier, T, Jungklaus, B et al 2020, ‘Between belief and fear - Reinterpreting prone burials during the Middle Ages and early modern period in German-speaking Europe Europe’, PLoS One 15:8, e0238439. Available online at: <doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0238439> [accessed 22 August 2021].

- Ariès, P 1981, The Hour of Our Death, Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Arts, N 2003, Marcus of Eindhoven: An Archaeological Biography of a Medieval Child, Utrecht: Matrijs.

- Aspöck, E 2008, ‘What actually is a ‘deviant burial’?”: Comparing German-language and Anglophone research on ‘deviant burials, in Murphy, Deviant burial in the archaeological record, 17–34.