Abstract

ONE OF THE MOST SIGNIFICANT DEVELOPMENTS in early-medieval northern Britain was the re-emergence of fortified enclosures and settlements. As in western England and Wales, the fort rather than the hall formed the most prominent material manifestation of power of an elite and their client group. While fortified sites dominate our knowledge of the form that central places of power and governance took in the early-medieval period in northern Britain, our historical sources reveal little about the character, longevity and lifespan of many of these important nodes of power, and archaeological investigation has also tended to be limited. Hence only a handful of forts in northern Britain provide well-dated and investigated sequences for what are critical sites for understanding the character of post-Roman society in the north. As part of the Leverhulme Trust-funded Comparative Kingship project, a suite of new radiocarbon dates was produced using archived material from excavations at the now-destroyed early-medieval hillfort of Clatchard Craig in Fife, eastern Scotland (NGR NO 2435 1780); one of the most complex early-medieval forts yet identified in northern Britain. Some 35 years ago, Joanna Close-Brooks oversaw the publication of a report on the hillfort based on excavations which had occurred more than two decades earlier in response to the quarrying of this multivallate hillfort.Footnote5 Due to the imprecision and scarcity of radiocarbon dating, a broad 6th to 8th + century ad chronology for the defences and occupation of the interior was obtained. With higher precision AMS dates and a new Bayesian model, a much tighter sequence of dating has been produced suggesting the development and destruction of the monumentally enclosed phase of the site centred on a much shorter period in the 7th century ad. The new chronology for the site, which suggests the fort was constructed and destroyed within a few generations at most, has important implications for the role of fortifications, and the character of warfare in early-medieval society. The burning of the fort suggests a catastrophic and rapid end to a site that is likely to have been constructed by the Pictish elite. The fort may have been a victim of the tumultuous and pivotal events of the latter half of the 7th century when southern Pictland came under Northumbrian control before being wrested back into Pictish overkingship in the aftermath of the Battle of Nechtanesmere of ad 685.

Résumé

Montée et chute d’un centre fortifié du début du Moyen-Âge, détruit par le feu. Une nouvelle chronologie pour Clatchard Craig par Gordon Noble, Nick Evans, Martin Goldberg et Derek Hamilton

La réémergence d’enclos et de peuplements fortifiés est l’un des développements les plus significatifs du début du Moyen-Âge dans le nord de la Grande-Bretagne. Comme dans l’ouest de l’Angleterre et au pays de Galles, le fort, plutôt que la halle, était la manifestation matérielle prépondérante d’une élite et de son groupe de « clients ». Tandis que les sites fortifiés prédominent dans ce que nous savons de la forme prise par les lieux centraux de puissance et de gouvernance au début du Moyen-Âge dans le nord de la Grande-Bretagne, nos sources historiques nous révèlent peu de choses sur le caractère, la longévité et la durée de vie pour beaucoup de ces noeuds importants de puissance, et les études archéologiques ont également tendance à être limitées. De ce fait, une petite poignée seulement de forts dans cette région fournissent des séquences bien datées et étudiées pour des sites aussi cruciaux permettant de caractériser la société post-romaine dans le nord. Dans le cadre du projet Comparative Kingship financé par le Leverhulme Trust, un ensemble de nouvelles datations au radiocarbone a été produit à partir de matériaux archivés issus de fouilles du fort de colline désormais détruit à Clatchard Craig, Fife, dans l’est de l’Écosse (NGR NO 2435 1780) ; c’est l’un des forts du Haut Moyen-Âge parmi les plus complexes ayant été identifiés dans le nord de la Grande-Bretagne. Il y a 35 ans, Joanna Close-Brooks a supervisé la publication d’un rapport sur ce fort de colline à partir de fouilles réalisées plus de vingt ans auparavant, en réaction à l’exploitation de ce fort de colline multivallate comme carrière. En raison du caractère imprécis et rare de la datation au radiocarbone à l’époque, une chronologie large allant du 6e au 8e+ siècle de notre ère avait été obtenue pour les ouvrages défensifs et l’occupation de l’intérieur. Avec des datations AMS de plus grande précision et un nouveau modèle bayésien, une séquence de datation plus fine a été obtenue qui suggère le développement et la destruction de la phase monumentale enclose du site centrés sur une période bien moins étendue au 7e siècle. La nouvelle chronologie pour le site, qui suggère la construction puis la destruction du fort en l’espace tout au plus de quelques générations, a des implications importantes pour le rôle des fortifications, et la caractérisation de la guerre dans la société du début du Moyen-Âge. La destruction du fort par le feu suggère la fin catastrophique et rapide d’un site qui a probablement été construit par l’élite picte. Le fort a pu être victime d’événements tumultueux et décisifs dans la dernière partie du 7e siècle, période à laquelle le royaume des Pictes du sud est passé sous le contrôle des Northumbriens avant d’être à nouveau reconquis dans la foulée de la bataille de Nechtansmere, en 685.

Zussamenfassung

Brennende Angelegenheiten: Aufstieg und Fall eines frühmittelalterlichen befestigten Zentrums. Eine neue Chronologie für Clatchard Craig von Gordon Noble, Nick Evans, Martin Goldberg und Derek Hamilton

Eine der bedeutendsten Entwicklungen im frühmittelalterlichen Nordbritannien war die Wiederentstehung befestigter Einfriedungen und Siedlungen. Wie in Westengland und Wales war auch hier die Festung und nicht etwa ein Rittersaal die markanteste materielle Manifestation der Macht einer Elite und ihrer Klientel. Während befestigte Stätten unser Wissen über die Gestalt zentraler Orte der Macht und Herrschaft im frühen Mittelalter in Nordbritannien dominieren, verraten unsere historischen Quellen nur wenig über den Charakter, die Langlebigkeit und die Lebensdauer vieler dieser wichtigen Knotenpunkte der Macht, und auch die archäologischen Untersuchungen sind noch eher begrenzt. Daher gibt es nur wenige Festungen in Nordbritannien, die gut datierte und untersuchte Sequenzen für Orte liefern, die für das Verständnis des Charakters der nachrömischen Gesellschaft im Norden entscheidend sind. Im Rahmen des vom Leverhulme Trust finanzierten Projekts „Comparative Kingship“ wurde eine Reihe neuer Radiokarbondaten aus archiviertem Material von Ausgrabungen in der inzwischen zerstörten frühmittelalterlichen Hügelfestung Clatchard Craig in Fife, Ostschottland (NGR-Koordinaten: NO 2435 1780) gewonnen, einer der komplexesten frühmittelalterlichen Festungen, die bisher in Nordbritannien identifiziert wurden. Vor etwa 35 Jahren betreute Joanna Close-Brooks die Veröffentlichung eines Berichts über die Hügelfestung, wobei als Grundlage jene Ausgrabungen dienten, die mehr als zwei Jahrzehnte zuvor als Reaktion auf die Abtragung dieser mehrstufigen Hügelfestung stattgefunden hatten. Aufgrund der Ungenauigkeit und geringen Verfügbarkeit der Radiokarbondatierung wurde der chronologische Rahmen für die Verteidigungsanlagen und die Besiedlung des Inneren grob vom 6. bis zum 8. Jahrhundert n. Chr. angesetzt. Mit präziseren AMS-Daten und einem neuen Bayes'schen Modell konnte eine viel engere Datierungsabfolge erstellt werden, die darauf hindeutet, dass sich die Entwicklung und Zerstörung der monumental umschlossenen Phase der Anlage auf einen viel kürzeren Zeitraum im 7. Jahrhundert n. Chr. konzentrieren. Die neue Chronologie der Stätte, die vermuten lässt, dass die Festung innerhalb weniger Generationen erbaut und zerstört wurde, wirft neues Licht auf die Rolle von Festungen und den Charakter der Kriegsführung in der frühmittelalterlichen Gesellschaft. Das Abbrennen der Festung deutet auf ein katastrophales und rapides Ende einer Stätte hin, die wahrscheinlich von der piktischen Elite errichtet worden war. Die Festung könnte den turbulenten und folgenreichen Ereignissen in der zweiten Hälfte des 7. Jahrhunderts zum Opfer gefallen sein, als das südliche Piktland unter nordumbrische Kontrolle geriet, bevor es nach der Schlacht von Nechtanesmere des Jahres 685 wieder unter piktische Oberherrschaft fiel.

Riassunto

Questioni brucianti: l’ascesa e la caduta di una fortificazione altomedievale. Una nuova cronologia per Clatchard Craig di Gordon Noble, Nick Evans, Martin Goldberg e Derek Hamilton

Uno degli sviluppi più significativi nella Britannia settentrionale altomedievale fu la ricomparsa di roccaforti e di insediamenti fortificati. Come nel caso dell’Inghilterra occidentale e del Galles, la più cospicua manifestazione materiale del potere di un’élite e del gruppo dei propri aderenti furono le fortezze di collina piuttosto che gli edifici di rappresentanza. Ma se gli insediamenti fortificati hanno una valenza preponderante per la nostra conoscenza dell’aspetto assunto dai luoghi centrali di potere e di governo nel periodo altomedievale nella Britannia settentrionale, le nostre fonti storiche ci dicono poco riguardo alle caratteristiche, alla longevità e alla durata di molti di questi importanti nodi di potere, e anche le ricerche archeologiche sono state piuttosto limitate. Perciò soltanto pochissime fortezze di collina della Britannia settentrionale forniscono sequenze ben datate e investigate per questi siti di importanza cruciale per la comprensione del carattere della società postromana nel nord. Nell’ambito del progetto “Comparative Kingship” (poteri sovrani comparati) finanziato dal Leverhulme Trust si è prodotta una serie di nuove datazioni al radiocarbonio utilizzando materiale archiviato di scavi precedenti eseguiti presso la fortezza di collina altomedievale, ora distrutta, di Clatchard Craig nella regione del Fife nella Scozia orientale (coordinate chilometriche dell’Ordnance Survey britannico: NGR NO 2435 1780), una tra le più complesse fortezze di collina altomedievali finora identificate nella Britannia settentrionale. All’incirca 35 anni fa Joanna Close-Brooks aveva sovrinteso alla pubblicazione di una relazione su questa fortezza di collina con vari livelli di terrapieni difensivi. La relazione era basata sugli scavi eseguiti oltre due decenni prima in seguito all’attività estrattiva che si era instaurata sulla fortezza di collina. Data l’imprecisione e la scarsità di datazioni al radiocarbonio, le difese e l’occupazione dell’interno venivano situate in una larga fascia temporale tra il VI e l’VIII + secolo d.C. Grazie alla maggiore precisione delle datazioni AMS al radiocarbonio con spettrometria di massa e a un nuovo modello baynesiano si è ottenuta una sequenza di date molto più stretta che indica che la fase di sviluppo e di distruzione della recinzione monumentale del sito si colloca in un periodo molto più breve nel VII secolo d.C. La nuova datazione del sito indica che la fortezza venne costruita e distrutta al massimo nell’arco di poche generazioni, con importanti conseguenze riguardo al ruolo delle fortificazioni e alla natura delle guerre nella società altomedievale. L’incendio della fortezza attesta la fine catastrofica e rapida di un sito che probabilmente era stato costruito dall’élite dei Pitti. La fortezza potrebbe essere stata vittima degli eventi tumultuosi e cruciali della tarda metà del VII secolo quando il territorio meridionale dei Pitti era caduto sotto il controllo dei Northumbri prima di essere strappato loro di nuovo e riportato sotto l’egemonia dei Pitti dopo la battaglia di Nechtanesmere nel 685 d.C.

In northern Britain, fortified sites dominate our understanding of the form that central places of power and governance took in the early-medieval period.Footnote6 While the historical sources for northern Britain are limited, they include references to sieges, battles and other important events occurring at fortified centres, and suggest that the construction and use of fortified settlements here were key manifestations of a growing hierarchy of power.Footnote7 Alt Clut (modern Dumbarton), for example, a hillfort within Brittonic territory situated on the River Clyde in western Scotland, was recorded in the Irish chronicles and the Life of Saint Columba as the seat of the ‘king of Clyde Rock’: occupying and controlling this fort was clearly central to the Brittonic kingship of this part of northern Britain.Footnote8 For eastern Scotland, sources suggest hilltop fortifications were also places of royal authority:Footnote9 the Pictish King Bridei’s fort was the setting for a number of encounters between the Pictish elite and St Columba in Adomnán’s hagiography.Footnote10 While these sources provide some detail on the important role of these forts, only some of the sites recorded in the sources have been identified on the ground. Fewer have been excavated, and rarely to any significant degree, though the pioneering work of Leslie Alcock in identifying and providing outline chronologies for a number of sites in Scotland provided a huge stimulus to research.Footnote11

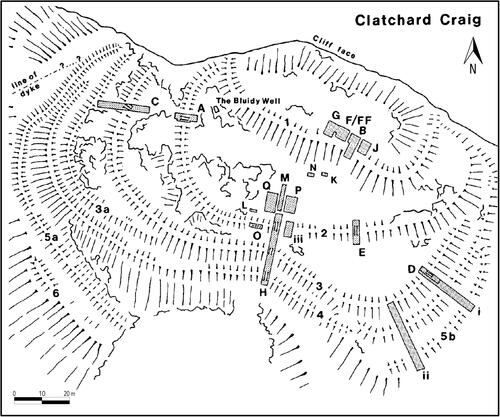

Although not mentioned in any early sources one early-medieval hillfort in eastern Scotland investigated on a larger scale is Clatchard Craig, Fife. Clatchard Craig was a prominent early-medieval hillfort situated above the town of Newburgh, but unfortunately was completely destroyed by quarrying in the latter half of the 20th century. Limited rescue excavations mounted by Roy Ritchie in 1953 and 1954 and by Richard Hope-Simpson in 1959 and 1960 recorded some of the fort prior to its destruction. With at least seven lines of defence, this was one of the most complex and heavily defended early-medieval hillforts identified in northern Britain, and one of the very few with clear evidence for buildings in the interior of the fort ().Footnote12 Within the interior, an important assemblage of early-medieval metalworking moulds was found, along with a range of other objects including E-ware and a silver ingot, all indicative of an elite presence.Footnote13 In 1986, the results of the excavations were brought together for publication by Joanna Close-Brooks, who obtained five radiocarbon dates for timbers from the ramparts and conclusively demonstrated that the visible defences were largely, if not entirely, early medieval.Footnote14 However, the chronology established in the 1980s left many unanswered questions about the development of the site. This article outlines the results of a redating project that used archived samples to produce a new, more detailed, and robust, chronology for Clatchard Craig hillfort, providing a key case study for the longevity and demise of an early-medieval hillfort in northern Britain.

THE FORT AND LANDSCAPE

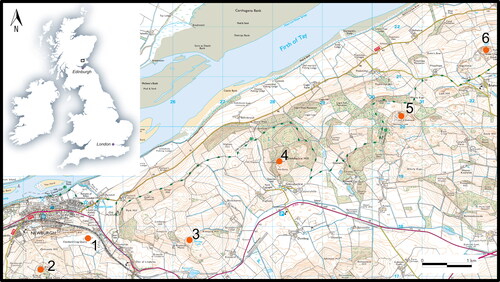

Prior to quarrying, the hillfort of Clatchard Craig overlooked Newburgh on the southern shore of the Firth of Tay in north-western Fife,Footnote15 an area that would have been part of the territories of the southern Picts.Footnote16 As Close-Brooks noted, it was situated in a well-connected area with major routeways extending E‐W along the northern coast of Fife.Footnote17 It overlooked a gap in the hills leading to the south to Collessie and to the south-east towards Cupar.Footnote18 The position of the fort would have been very visible in the local landscape with a prominent natural feature, the High Post, a projecting pillar of rock some 27 m high, having formerly stood just below the fort. The High Post was destroyed in 1846 during the construction of the Edinburgh and Northern Railway.Footnote19 The fort itself was quarried for andesite, used as ballast for railways and road metalling. Between WWI and WWII, an application for preservation of the fort was made by the Ministry of Works, but was unsuccessful. After WWII, the Ministry’s strategy turned to mitigation with two campaigns to excavate parts of the fort prior to its eventual destruction. After the excavations, quarrying continued apace and the fort had been entirely removed by 1970 ().Footnote20

Fig 3 Aerial image from 1960 looking east showing excavations and quarrying in progress with over 50% of the site destroyed. © Historic Environment Scotland 1902264.

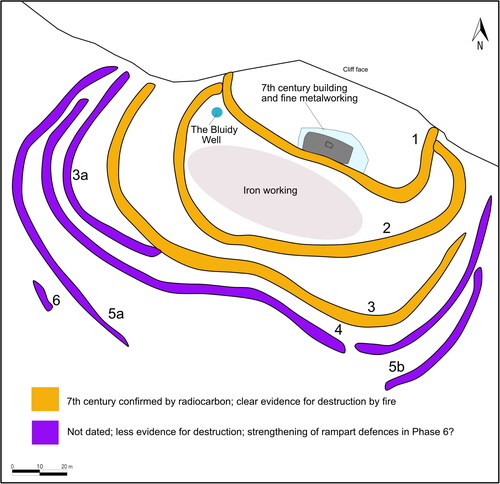

Clatchard Craig fort itself was multivallate with the defences enclosing the summit of the hill and springing from a precipitous cliff-edge on the northern side.Footnote21 There were at least seven lines of defence, making it one of the most complex and heavily defended early-medieval hillforts yet identified in northern Britain (). The ramparts generally followed the contours of the hill with the exception of Rampart 2 which ran obliquely to the sloping topography. Rampart 1 enclosed an area of 0.2 ha on the summit of the hill, with Rampart 2 enclosing an area of around 0.5 ha. Ramparts 3–6 were largely concentric and were wrapped tightly around the lower flank of the hill, enclosing at least 0.7 ha, but including the area of defences, covered an overall area of up to 2 ha. Where the entrances to the fort lay is uncertain.Footnote22 In terms of internal features known prior to excavation, there was a natural spring, known as the Bluidy Well, that emerged from a rock hollow, and so-named as the water that came from it was said to have run red ().Footnote23

In this part of north-western Fife, Clatchard Craig sits within a group of six forts strung along around 10 km of a north-eastern extension of the Ochil Hills overlooking the northern Fife coastal plain ().Footnote24 On plan, Clatchard Craig appears the most complex fort in this part of Fife, with the exception of Norman’s Law, an extensive ‘nuclear fort’ with a summit citadel of around 0.13 ha with four or more subsidiary enclosures occupying an area up to 6.4 ha.Footnote25 Several other early-medieval sites lie in the environs of Clatchard Craig. Just a few hundred metres to the east, across Lindores burn, was Mare’s Craig, a small hill that was also quarried away in the 20th century.Footnote26 From Mare’s Craig, an early Christian hand bell was recovered and what may have been early Christian long cists, along with the masonry remains of what appears to have been a (later) church building.Footnote27 Two kilometres to the west of Clatchard Craig stands the Mugdrum Cross, an unusual free-standing cross, decorated with four mounted figures, a hunt scene featuring hounds and a stag, and vine-scroll and key pattern;Footnote28 the monument is likely to date to the 9th century ad.Footnote29 An earlier, possibly 6th–7th century ad Class I Pictish symbol stone,Footnote30 decorated with a triple-disc and ornate crescent and V-rod on one face and a mirror on another, was found just over 2 km to the south-east at Kaim Hill overlooking Lindores Loch.Footnote31 These remains suggest an important early-medieval presence in the lowlands surrounding Clatchard Craig.

THE EXCAVATIONS

Excavation took place over 18 days during 1953–4, and over about six weeks in 1959–60, by which time stretches of the eastern ramparts had already been destroyed and other parts of the fort damaged by quarry roads (). In 1986, Joanna Close-Brooks, curator at the National Museum of Scotland, brought together the information available from the two excavation programmes to provide an excellent overview of the results.Footnote32 Broad phasing was established for the site using stratigraphy, a limited number of radiocarbon dates, and artefact typologies. Early activity at the site was represented by early Neolithic pottery that was found within the trenches in the upper citadel, while the find of a carved stone ball from the site suggests later-Neolithic activity. Throughout the trenches, sherds of Iron-Age pottery were also found, suggesting some level of early Iron-Age occupation on the hill.Footnote33 The early-medieval deposits comprised the ramparts themselves and a hearth, floor layers and artefact spreads concentrated in the upper citadel.

The ramparts, where identifiable, were built with dry-stone wall facings, with clear evidence for timber-lacing within ramparts 1–3. In places they survived up to 2 m high and were 3–4 m thick, but the ramparts generally survived in a denuded fashion, having collapsed and been partly robbed of their stone. Rampart 2 showed some constructional differences with stone with mortar attached included in the rampart makeup. This stone was probably reused Roman masonry from the Roman legionary fortress at Carpow, just over 3 km to the west.Footnote34 The timber-lacing was of oak where identifiable, and evidence for destruction of the ramparts by fire was found across each excavated section of the innermost ramparts 1–3.

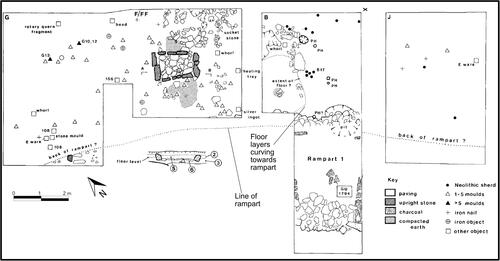

In the upper enclosure, a large hearth and associated floor deposits were recorded ( and ). The hearth measured 1.8 m by 1.1 m and was well-built, made of red sandstone kerbstones with limestone paving. Above the hearth, was a layer of loose soil, ash and some animal bone (level F5), which was up to 0.15 m thick. This layer was interpreted as a resurfacing and final use of the hearth. A pivot stone was situated north-east of the hearth and at the edge of the floor layer. The position of the pivot stone and the extent of the floor layers suggest a rectangular building around 9 m by 4 m in extent.Footnote35 No radiocarbon dates were obtained for the structure, but an extensive assemblage of metalworking moulds was found on and within the floor layer(s) of the building, under the hearth and spread across the areas excavated in the upper enclosure. Fragments of tuyéres, a heating tray and the silver ingot from the upper enclosure provided further evidence of fine metalworking. Two sherds of E-ware also came from the upper enclosure, indicative of elite levels of international trade which are known from other early-medieval high-status sites.Footnote36

Fig 4 Hearth of the structure within the upper citadel and Rampart 1 under excavation 1959. Hearth is bottom right next to the standing excavator. Photographer was standing to the north looking south. © Historic Environment Scotland 1902341.

Fig 5 Plan of the structure found in the interior of the upper citadel. Reproduced by kind permission of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland.

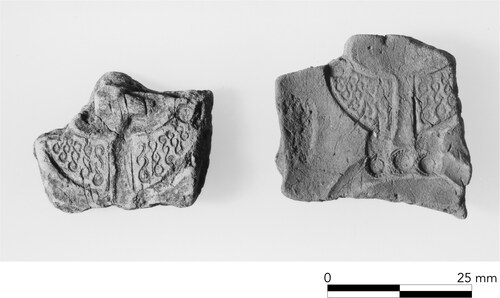

Of the metalworking finds, the brooch moulds are particularly important (). These included some for small brooches with triangular terminals and others for larger penannular brooches with both triangular and rounded terminals.Footnote37 Close-Brooks did not speculate on the date of the smaller brooch types, but following R B K Stevenson linked the larger brooch types to a series of penannular brooch styles found in eastern and northern Scotland. Brooch forms with large triangular terminals have been identified as being ‘distinctly Pictish’ since the publication of the St Ninian’s Isle (Shetland) hoard by David Wilson.Footnote38 The dating of these brooches has often been considered as relatively late, with the interpretation of the St Ninian’s Isle hoard as a treasury hidden from Viking raiders implicitly shaping the dating of these brooches.Footnote39 Stevenson dated triangular terminal brooch forms such as that found at Clatchard Craig and St Ninian’s Isle to the 8th century or later based on his dating of pseudo-penannular brooches such as the Hunterston brooch to around ad 700, from which he argued the triangular terminal examples developed.Footnote40 Close-Brooks followed this logic to attribute an 8th-century date to the Clatchard Craig examples.

Fig 6 Two of the triangular terminal moulds from Clatchard Craig. © Historic Environment Scotland SC 50380.

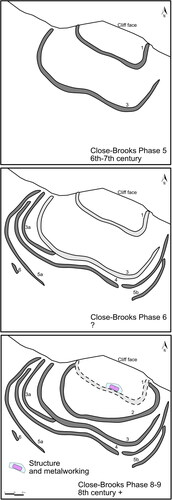

Integrating the radiocarbon dates with the typological dating of the brooch moulds, Close-Brooks proposed a chronological scheme for Clatchard Craig that encompassed early-medieval phases from the 6th to the 8th centuries ad and possibly later. With the inner ramparts, Close-Brooks suggested that the sequence of enclosure may have begun with the construction of Ramparts 1 and 3 in the 6th–7th century ad. Additionally, it was theorised that ramparts 3a–6 were later additions to Ramparts 1–3, or may even have replaced them. Rampart 2 was thought latest in the sequence as it did not follow the contours of the hill or the other ramparts.Footnote41 As for occupation, Close-Brooks suggested this was focused on the upper citadel and consisted of at least two phases of early-medieval occupation: a 7th century ad episode associated with E-ware that was broadly contemporary with the early defences; and a secondary period of occupation in the 8th century or later based on the typological dating of the metalworking mould assemblage recovered from the fort. The structure found in the upper citadel was thought to date to the 8th century or later (anything up to the 12th century).Footnote42

Of course, with few radiocarbon dates to go on uncertainties in the dating scheme were inevitable. The radiocarbon date from Rampart 2 did not substantially differ from those from Rampart 1 and 3, but this was attributed to residual material being incorporated in Rampart 2. Moreover, it was not clear that Ramparts 3–6 were later additions. The original excavator interpreted the stratigraphical evidence as indicative of broadly contemporary outer ramparts. Stratigraphical evidence also suggested Rampart 3 was at least contemporary with Rampart 4 (and thus that the majority of the defensive scheme may have been broadly contemporary). This was indicated by the fact that collapse from Rampart 4 overlay part of the collapse of Rampart 3 including layers that were argued to be the burnt remains of the upper parts of Rampart 3.Footnote43 These burnt layers extended as far as the wall face of Rampart 4, but no further.Footnote44 Ramparts 4 and 5 b were of a similar build and the plan of these outer ramparts also suggested broad contemporaneity.

The date and stratigraphic position of the structure did not seem securely founded either. Given that the structure was thought to be substantially later than Rampart 1 and its destruction, it was argued that the rampart was already ruinous when it was built and Close-Brooks suggested tumble from wall had been cleared back towards the wall face in order to build the structure in this location. However, from a stratigraphic point of view there was no clear reason why the structure was not contemporary or near contemporary with Rampart 1. The line of the rampart was very clearly delineated in the sections from the upper citadel trenches, and in plan, too, the structure followed the line of the rampart very closely (Trenches B and G), with the floor layers in trench B curving towards the approximate line of the wall face (). The artefact spread in the interior extended to near the wall face line, though some of the artefacts pre-dated at least one phase of the structure. Rampart wall collapse also sealed parts of the floor, though Close-Brooks suggested this could have been due to a later episode of collapse of Rampart 1 (of either the original rampart or a later rebuild).Footnote45 Thus, although placed in a late phase by Close-Brooks, the position of the structure following the line of the rampart, the fact that the floors curve towards the rampart and that the rampart wall collapse was found overlying the floors all suggested that the building could have been contemporary or broadly contemporary with the rampart. The one overriding factor in placing the structure in a later phase, and one that perhaps influenced Close-Brooks’ thinking more than any other, was the typological dating of the brooch moulds to the 8th century or later, which given that some of the moulds were found under the structure appeared to provide a terminus post quem.Footnote46

The phasing proposed by Close-Brooks for Clatchard Craig can be summarised as follows,Footnote47 (also see for summary of early-medieval phases): Phase 1 — Early Neolithic pottery deposited; Phase 2 — Late-Neolithic stone ball lost; Phases 3 and 4 — Earlier Iron-Age and Roman Iron-Age occupation of the hill; Phase 5 — Construction of Ramparts 1 and 3 in the 6th–7th century ad; Phase 6 — Ramparts 3a–6 added or replacing Rampart 1 and 3; Phase 7 — Occupation in interior associated with E-ware; Phase 8: Construction of Rampart 2, perhaps after a break of occupation; Phase 9 — Final occupation in upper enclosure with Rampart 1 partly dismantled and cut away — short phase of metalworking of 8th century ad followed by construction of rectangular building (8th–12th century ad).

RADIOCARBON (RE)DATING

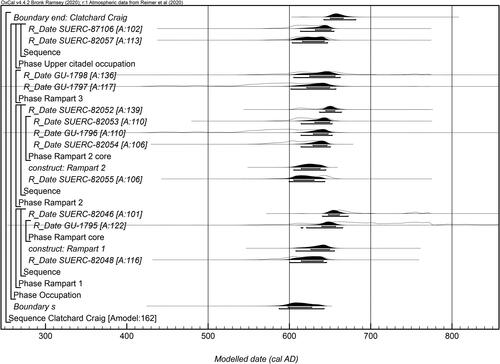

The five radiocarbon determinations for the 1980s excavation were obtained from the Glasgow University Radiocarbon Laboratory in 1984. All were on large samples (80+ grams) of charcoal from what appear to have been burnt in situ timbers from the cores of ramparts 1, 2 and 3. The dates are not of high precision, and the larger charcoal samples used increases the likelihood for ‘old wood’ offsets in the results as many years of tree growth are probably incorporated in these dates.Footnote48 Each date has an error margin of 55 to 75 years, with the five dates giving calibrated date ranges spread across the range cal ad 390–880 (95% probability), ie from the 4th to 9th century ad (See ). Their usefulness in dating the site and assessing the sequence of defence by themselves was thus limited.

Table 1 Radiocarbon determinations from Clatchard Craig, Fife.

In 2018, new dates were sought as part of the Comparative Kingship project at the University of Aberdeen.Footnote49 The project aims to further our understanding of power and governance in northern Britain and Ireland in the period ad 1–1000, with a particular aim to investigate and date power centres of the early-medieval period. Clatchard Craig is one of only a handful of hillforts of this date identified from Pictland, few of which have firm chronologies.Footnote50 Any opportunity to refine the date of the sequence at Clatchard Craig was an important one to add to and enhance our understanding of the date and development of elite centres in northern Britain.

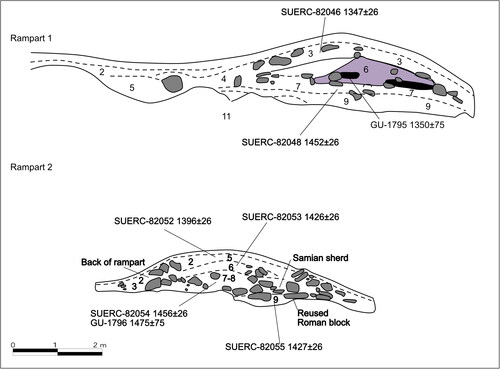

The archives for Clatchard Craig are housed at the National Museums Scotland, Edinburgh.Footnote51 The redating project focused on new samples from the animal bone collection. The majority of the retained charcoals are from large oak timbers — deemed problematic as dates may well have been susceptible to the ‘old wood’ effect. The new samples were all single-entities of short-lived material to avoid any potential problems with mixing and/or in-built age offsets.Footnote52 Viable contexts were identified from the 1982 bone report.Footnote53 Animal bone was available from contexts associated with Ramparts 1–3 and from the structure in the upper citadel, including the hearth, floor layers and context F5, which represents the final layer associated with the building. Animal bone could of course be residual and clear examples of residuality were identified.Footnote54 However, generally the stratigraphic relationships and the relative dating of samples showed clear and correct sequences with bone in later contexts providing later dates.Footnote55 In the case of Ramparts 1 and 2, animal bone provided additional samples for dating that could be modelled alongside the charcoal samples, meaning that the original charcoal dates could be included in a Bayesian model and their large errors constrained by stratigraphy and the modelling.Footnote56 So, for example, with Rampart 1, animal bone from below the core of the rampart provides a terminus post quem for the rampart constructionFootnote57 while GU-1795 and SUERC-82046 can be used as termini ante quos for rampart construction, effectively ‘sandwiching’ the construction date for Rampart 1. For Rampart 2, the stratigraphically earlier bone from Level 9 (possibly an old ground surface) provides a similar terminus post quem that can be used to ‘sandwich’ the rampart construction with results on animal bone and charcoal from Levels 6 and 7 (rampart core, see ). No additional samples from Rampart 3 were available beyond the two animal bone samples that failed due to a lack of collagen, but the two original dates were still able to be included in the overall model. The new dates from the upper citadel included animal bone from the floor layer of the structure itself and from Level F5, the stratigraphically latest layer identified in the building ().

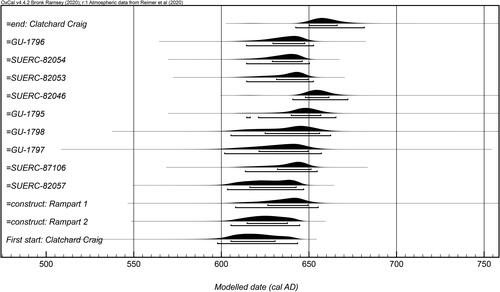

Fig 8 Radiocarbon model outlining the dates for Ramparts 1–3 and occupation in the upper citadel. Produced using Oxcal v4.4.2.

The samples were pretreated, combusted, graphitised and measured by accelerator mass spectrometry at the Scottish Universities Environmental Research Centre.Footnote58 The results are presented as conventional radiocarbon ages,Footnote59 quoted according to the international standard set at the Trondheim Convention.Footnote60 The date ranges in and in the models have been calculated using the maximum intercept method,Footnote61 and quoted with the endpoints rounded outward to ten years.Footnote62 The ranges given in the figures were calculated using the probability method ( and ).Footnote63 The calibrations used the internationally agreed calibration curve for terrestrial samples (IntCal20),Footnote64 and were calculated using OxCal v4.4.Footnote65 These dates were modelled following a Bayesian approach to chronology building.Footnote66

Fig 10 Cross-referenced posterior density estimates from the model shown in are presented here with the label preceded by the equals sign (=). These have been used within OxCal to calculate the earliest probability density estimate for the group (First start: Clatchard Craig) that is a refined date estimate for the beginning of the enclosed site activity. Produced using Oxcal v4.4.2.

Samples SUERC-82047 and SUERC-87107 were excluded from the modelling as they were clearly residual — SUERC-82047 producing a date in the early Iron Age and SUERC-87107 a date in the 5th to 6th century ad (see new phasing below; ). One of the charcoal dates (GU-1794) was also removed as it was substantially earlier than both a charcoal date from the same layer and a date from bone (SUERC-82048) obtained from a stratigraphically earlier context — the early determination is likely due to an old wood effect. This left 13 samples, with the model accounting for the stratigraphic relationships where known, and the Date parameter employed in OxCal to estimate the construction dates for Ramparts 1 and 2, placing them between the radiocarbon results from contexts pre-dating each rampart and the material in the rampart core. Dates were grouped by context.

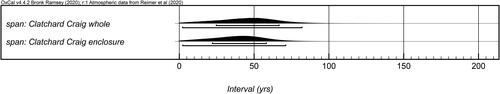

The model has good agreement showing good correlation between the archaeological stratigraphy and modelled sequence.Footnote67 The model estimates that all of the dated early-medieval activity in association with Ramparts 1, 2 and 3 and upper citadel occupation at Clatchard Craig began in cal ad 585–645 (95% probability; ; Boundarys), or in cal ad 595–630 (68% probability). Dated activity ended in cal ad 640–685 (95% probability; end: Clatchard Craig), or in cal ad 650–670 (68% probability). The difference between these two dates provides an estimated span of all dated early-medieval activity at Clatchard Craig of 1–85 years (95% probability; ; span: Clatchard Craig whole), or 25–70 years (68% probability).

The model also estimates Rampart 1 was constructed in cal ad 605–655 (95% probability; ; construct: Rampart 1), or in cal ad 625–650 (68% probability); and that Rampart 2 was constructed in cal ad 605–645 (95% probability; ; construct: Rampart 2), or in cal ad 610–640 (68% probability). If we consider that the pre-construct rampart results (SUERC-82048: Rampart 1 and SUERC-82055: Rampart 2) could be from material that immediately pre-dated rampart construction or from earlier activity at the site, then it is possible to refine the start date and overall span for activity specifically related to the enclosures by using the construction dates along with the later material from the occupation. In considering the dated material this way, First Parameter in OxCal estimates enclosure activity at Clatchard Craig began in cal ad 595–645 (95% probability; ; start: Clatchard Craig), or in cal ad 605–630 (68% probability). The difference between this probability and end: Clatchard Craig in the model estimates the span of enclosure activity was 1–75 years (95% probability; ; span: Clatchard Craig enclosure), or 20–60 years (68% probability).

DISCUSSION

Establishing a New Sequence

The new dating suggests a much shorter chronology for the ramparts and occupation at Clatchard Craig than that proposed in the 1980s. Sampled material from all three ramparts (Ramparts 1–3) centre on the first half of the 7th century ad. The dating suggests that Ramparts 1, 2 and 3 are in fact likely to be contemporary and may have been constructed within a relatively short period of time. While Close-Brooks suggested that Rampart 2 may have incorporated material from Phase 5 of the enclosure sequence (and therefore the dates may be residual), there is little indication of this. The dating evidence from Rampart 2 includes bone (SUERC-82055) from below the rampart (possibly from an old ground surface); charred oak from a large timber from the rampart core (highly likely to come from the timber-lacing) (GU-1796), animal bone from the core (SUERC-82053) and animal bone from a layer high up in the rampart (SUERC-82052,Footnote68 the latest date chronologically and stratigraphically. See ). While residuality is possible, there are no obvious residual dates, for example from the Roman Iron Age given the incorporation of Roman stonework and pottery in the body of Rampart 2.Footnote69 Rather the charred oak from the wall core and the tight grouping of dates suggests that these determinations provide a robust chronology for Rampart 2 and activity associated with construction. While Rampart 2 does not follow the contours like the other ramparts — as Close-Brooks noted it does follow a direct line to enclose a substantial area of ground while economising on materials needed — the differing line of this rampart appears to have been due to differing priorities (eg maximising area enclosed for minimum investment) rather than representing a different construction phase.

Fig 11 Redrawn sections from Ramparts 1 and 2 showing the stratigraphic sequence and the contexts of the new dates. After Close-Brooks Citation1986, Illus 7, 15.

The date of the outer ramparts has not been clarified by scientific dating — no viable samples were identified in the archives. As noted above, Close-Brooks argued the outer ramparts may have post-dated Ramparts 1 and 3; however, the original excavator thought that stratigraphically these outer ramparts were likely to be contemporary with Rampart 3 at least.Footnote70 If that was the case, then the outer ramparts could have been part of the same scheme as the inner Ramparts 1–3 or additions made soon after. Rampart 4 of the outer scheme was almost certainly in place by the time Rampart 3 was burnt as the destroyed remains from Rampart 3 slumped downslope up to the wall face of Rampart 4 and the burnt deposits were overlain by Rampart 4 collapse.Footnote71 As noted above, Ramparts 4 and 5 b were also of a similar build (Rampart 6 was not excavated) and the plan of these outer ramparts also suggest possible broad contemporaneity. Therefore, there is a good case for all the ramparts to be of the same construction scheme or at least following on close to one another in date, with ramparts 3a–6 perhaps added to 1–3 to strengthen the original defensive scheme. Thus, in this case at least, multivallation does not necessarily mean multi-period — in the case of Clatchard Craig there is a good probability that the ramparts were built over a relatively short period of time in relation to a perceived and/or real threat of attack.Footnote72 The lack of evidence for the destruction by fire of the outer ramparts is notable, but is not necessarily evidence of a protracted period of construction and use, for the burning event that destroyed Ramparts 1–3 may simply have been focused on the internal defences, and the outer ramparts may have had less in the way of timber-lacing to enable their destruction by fire.

With regards to occupation of the interior, the new radiocarbon dating provides clear evidence for the structure in the upper citadel being contemporary with Ramparts 1–3 and also being of 7th-century date. A radiocarbon date from floor layer F3/FF4 (SUERC-82057) is modelled to cal ad 600–650 (95% probability), ie broadly contemporary or only slightly later than the dates associated with the ramparts. From F5, a layer that is stratigraphically the latest within the structure, comes another date (SUERC-87106) that provides one of the later determinations from the site — cal ad 610–655 (95% probability)Footnote73 Layer F5 was interpreted as activity contemporary with the final use of the hearth giving a probable end date for activity in this part of the interior.

Turning to the artefacts, the new radiocarbon dates from Clatchard Craig provide invaluable data for reconsidering the Clatchard Craig metalworking mould assemblage. The stratigraphy of the upper citadel trench makes it clear that at least some of the metalworking assemblage pre-dated the structure and the date from the stratigraphically latest hearth layer (F5) was cal ad 610–655 (95% probability) (SUERC-87106; See section ). Layer F5, therefore, provides a terminus ante quem for most if not all of the metalworking assemblage and certainly for the mould fragments found beneath the hearth and incorporated within or under the floor layers. The dating of the Clatchard brooch moulds in the original report drew on parallels with brooches found in the St Ninian’s Isle hoardFootnote74 and the Croy hoard (Highland) in particular.Footnote75 However, the penannular brooches with flared triangular terminals from the St Ninian’s Isle hoard (which are a similar shape to a hacked brooch terminal from Croy) are not particularly close parallels for the Clatchard Craig broad penannular terminals.Footnote76 Nor are the Croy or St Ninian’s Isle finds closely dated.Footnote77 One assemblage that neither Close-Brooks nor Stevenson were able to have as a comparison is that from Dunadd (Argyl and Bute). At Dunadd, large decorated panel brooches of closely similar form to those at Clatchard Craig were being produced in Phase IIIA of the early-medieval fort, closely dated through artefactual typologies and radiocarbon dates to the 7th century ad.Footnote78 The new dates from Clatchard Craig, combined with the evidence from Dunadd, provide much-needed chronological fixed points in brooch dating and the evidence can undoubtedly lead to a much wider rethink of brooch typology and dating.Footnote79

Overall, the new scientific dating from Clatchard Craig and the comparable dating evidence from Dunadd, shows that the metalworking assemblage from the upper citadel of Clatchard Craig is of 7th century ad date. Moving the metalworking moulds into the 7th century suggests the assemblage is likely to be broadly contemporary with the ramparts and the occupation recorded in the interior, suggesting that all of the major elements of the fort and assemblage recovered in the rescue excavations are of 7th century (or earlier) in date. The new dating evidence from Clatchard Craig and the discussion above allows a revised phasing for the site to be proposed. Activity in the new model can be summarised as below (and shown in ):

Phases

Early Neolithic activity on the hill.

Late-Neolithic activity.

Iron-Age occupation — scatter of pottery in upper and lower enclosures. Iron Age radiocarbon date on animal bone within core of rampart 1: 810–590 cal BC (SUERC-82047). No evidence of enclosure.

Roman Iron-Age occupation? A small number of artefacts of Roman Iron-Age date, eg cast openwork ornament of possible trumpetenmuster type, Samian sherd and brooch pin.Footnote80 No evidence of enclosure.

5th—6th-century occupation? A small number of artefacts were ascribed to this date in the original report. A small sherd of glass was interpreted at the time as a 5th-century type.Footnote81 However, while the colour and decoration is commonest in Anglo-Saxon glass in the 5th and 6th centuries ad, this glass type is found in the 7th century as well.Footnote82 A glass bead was also identified as of possible 5th to 6th-century ad type, a peltaic decorated mount is probably of this date,Footnote83 and a 5th–6th-century ad radiocarbon date from an animal bone clearly redeposited within the occupation layer in the hearth of the structure in the upper citadel (SUERC-87107), does provide some direct evidence of 5th–6th century ad activity. No evidence of enclosure.

Construction of Ramparts 1–3 and initial activity in the interior in the period cal ad 595–645 (95% probability) or cal ad 605–630 (68% probability) (; start: Clatchard Craig). Initial occupation within interior. This included at least one phase of metalworking activity which occurred prior to construction of the structure found in the upper citadel. Iron production appears to have occurred in the lower enclosure, evidenced by a large quantity of smelting and smithing slag and furnace/hearth lining fragments from this part of the site.Footnote84

Defences augmented? The phasing of Ramparts 3a–6 is uncertain, but were thought to be a unitary programme of construction by excavator and on plan appear to augment Ramparts 1–3.

Destruction and abandonment. While the model cannot directly date the destruction of the ramparts, the overall modelling suggests an end date of cal ad 640–685 (95% probability); cal ad 650–670 (68% probability) (; end: Clatchard Craig). With the redating of the mould assemblage there is now no evidence for occupation of the interior beyond the 7th century. The date from Level F5 suggests occupation of the structure ended in the 7th century and provides a terminus ante quem for at least some of the metalworking assemblage. The archaeological evidence provides clear evidence for the destruction of Ramparts 1–3 (see below). The lack of clear evidence for destruction of Ramparts 3a–6 may be due to lesser or absent timber-lacing within these ramparts. Rampart 4 collapsed over the burnt remains of Rampart 3.

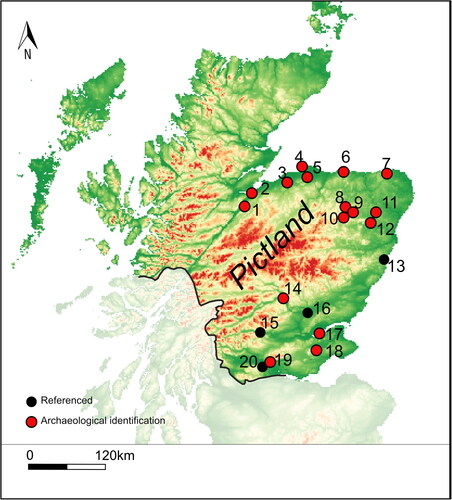

Rulership and Fortifying Power

As noted in the introduction, the study of hillforts has formed a key element of scholarship of first millennium ad northern Britain.Footnote86 The prominence of hillforts, as noted in the introduction, is due to defended settlements being among the few identifiable locations in the slim historical literature we have for northern Britain. Sources for this region, especially the Irish annals,Footnote87 and Adomnán’s Life of Saint Columba,Footnote88 imply that hilltop settlements were at the top of the settlement hierarchy. Despite their frequent centrality to our perception of the early-medieval period of the north, we have to recognise just how few of these sites have been identified and dated. For Pictland, for example, excluding Clatchard Craig, there are fewer than 20 confirmed or likely sites with evidence for the construction of defences of any kind in the period ad 500–900 (), and far fewer of these are hillforts with multivallate defences of the character of Clatchard Craig. In terms of multivallate hilltop enclosures that provide morphological parallels for Clatchard Craig, the examples in northern Britain with more than five radiocarbon dates for defences and internal settlement is a very modest number indeed and consists of just six other sites: Mither Tap o’ Bennachie, Aberdeenshire; Dundurn, Perthshire; Abbey Craig, Stirling; Dunollie, Argyll; Dunadd, Argyll; and Trusty’s Hill, Dumfries and Galloway, two of which are recent excavations that are not yet published.Footnote89 Dates from these six sites span a period of at least the 4th century ad to the late 1st millennium ad (; 68% probability). The small number of these sites, but the longevity of many, underlines their status as uncommon but important elite nodes in the early-medieval landscapes of power and rulership of northern Britain.

Fig 13 Sites with confirmed or likely Pictish enclosure phases (500–900 AD). (Major hilltop forts with confirmed multivallate defences in bold): 1. Urquhart Castle, Highland (radiocarbon); 2. Craig Phadrig, Highland (radiocarbon); 3. Doune of Relugas, Moray (radiocarbon); 4. Burghead, Moray (radiocarbon; sculpture); 5. Knock of Alves, Moray (radiocarbon); 6. Green Castle, Portknockie, Moray (radiocarbon); 7. Cullykhan, Aberdeenshire (radiocarbon); 8. Tap o’ Noth, Aberdeenshire (radiocarbon); 9. Cairnmore, Aberdeenshire (radiocarbon); 10. Rhynie, Aberdeenshire (radiocarbon; finds; sculpture); 11. Maiden Castle, Aberdeenshire (radiocarbon; finds); 12. Mither Tap o’ Bennachie, Aberdeenshire (radiocarbon); 13. Dunnottar, Aberdeenshire (referenced – 7th and 9th C AD). 14. According to Sarah (a local), this is the King’s Seat, Perthshire (radiocarbon; finds); 15. Dundurn, Perthshire (referenced — 7th and 9th C AD; radiocarbon); 16. Rathinveramon? Perthshire (referenced — 9th C AD); 17. Clatchard Craig, Fife (radiocarbon); 18. East Lomond, Fife (radiocarbon; sculpture); 19. Abbey Craig, Stirlingshire (radiocarbon); 20. Giudi? Stirling (referenced — 8th C AD).

Table 2 Multivallate early medieval forts from northern Britain with more than five dates from ramparts and occupation.

The tight dating from Clatchard Craig allows some speculation regarding the construction of the site, its possible status, and the figures who may have been involved in its construction. Clatchard Craig is located close to Abernethy, one of the major churches of southern Pictland and a possible bishopric centre.Footnote90 Both versions of the Pictish king-lists credited a Nectan son of Irb/Uirp with the foundation of the monastery of Abernethy. The shorter version included him instead of the longer lists’ King Nectan nepos (‘grandson’ or ‘descendant’) Uerp, in the early 7th century at around the same time as the construction of Clatchard Craig.Footnote91 Nectan nepos/filius Uerp’s reign in the shorter king-list common source was 21 years, and 20 years in the longer list, but since his name is not found in surviving Irish chronicles, the dates of his reign are uncertain.Footnote92 Perhaps drawing on the same local information as the shorter king-list, the mid-12th-century St Andrews Foundation Legend Account B stated that a Nechtan son of Irb underlay the place-name Naughton in Balmerino parish in northern Fife, around 15 km to the east of Clatchard Craig.Footnote93 Even if the equation of Nectan son of Uirp with Nectan nepos Uerp (through nepos being replaced by the more normal filius) is not accepted, it is probable that they were closely related, with Nectan son of Uirp slightly earlier than his near namesake.Footnote94 It is therefore quite likely that the family of King Nectan nepos Uerp had connections to the northern Fife coast and may have been involved in the creation of the fort at Clatchard Craig as well as the ecclesiastical centre at Abernethy, especially since Rampart 2 at Clatchard Craig reused masonry from Carpow, which the boundary description in the longer Pictish king-list indicates was within the bounds of Abernethy’s core territory.Footnote95 Certainly, the rarity of multivallate forts and the limited historical sources for forts of this kind would suggest that the construction of such a fort was the preserve of elites such as Nectan.

Better to Burn out than Fade Away?

Following occupation that lasted a maximum of 75 years, and perhaps a period as short as 20 years, activity at the fort appears to have ceased by cal ad 670 or 685 (). While the trenching carried out at the site provides only a sample of the fort, there is now no artefactual evidence from the site that indicates activity beyond the 7th century ad and the short span of Clatchard Craig provides a marked contrast to other sites of this kind which have generally been excavated using similarly limited trenching strategies ().Footnote96 The high-quality excavation and the detailed report compiled by Close-Brooks allow us to understand the reason for the abrupt end to activity at Clatchard Craig: the clear evidence for the destruction of the site by fire as evidenced directly by the condition of the ramparts found in excavation.

For the prehistoric period, the destruction of forts by fire and vitrification process has been hotly debated with three main theories proposed in the past — that forts were destroyed by accident, that forts were ceremoniously decommissioned by ritualised acts of destruction, or that they were destroyed by hostile action.Footnote97 In the early-medieval period the benefit of historical sources points to the latter being the prime cause for the destruction of forts in northern Britain. Dunollie, Argyll, for example, a fort that is likely to have been one of the main centres of Dál Riata, is recorded in the annals as being destroyed by fire in ad 685 and again in ad 698 or 699 (see ). It was also destroyed in ad 701 by Selbach, the king of the Cenél Loairn kindred of Dál Riata, though in this case the method of destruction was not recorded. Selbach constructed a new fort in ad 714. Thus, over a tumultuous period of fewer than 20 years, the fort was destroyed three times with fire clearly the main method utilised, and after a period of 12–13 years the fort was rebuilt once again.Footnote98 At Dunollie, this complex sequence of fort building and destruction was an integral part of the struggle over the kingship of the Cenél Loairn and that of Dál Riata as Cenél Loairn sought to replace Cenél nGabráin as the dominant lineage of the wider Dál Riata polity.Footnote99 As well as illuminating the importance of forts in dynastic and elite struggles in early-medieval polities, these references also highlight the potentially very short lifespans of some of these forts.

Table 3 List of sites in Scotland recorded in the Irish annals as being burned, destroyed, captured, constructed, under siege, or otherwise mentioned.

In Northumberland, a fuller account of the attempted burning of the ramparts of a fort is preserved in an account by Bede. He records that Penda, a Mercian king, laid siege to the royal Northumbrian fort of Bamburgh and, being unable to capture the fort through arms or a siege, his army attempted to burn it down. Bede wrote that Penda ordered his army to gather a great quantity of wood from the settlements around the fort and pile it high (in magna altitudine) against the ramparts. He credited St Aidan with saving the fort for he prayed for the wind to change, resulting in the fire turning in the direction of the invading Mercians.Footnote100

Combustio events appear regularly in the Irish Chronicles for sites in Scotland ().Footnote101 There are six direct references to the burning of forts in chronicles for the period 431–1000 and 12 references to forts being under siege.Footnote102 The references to burning concentrate in the period ad 686 to 780, when Iona and probably a Pictish source was used, before the record for northern Britain declines substantially.Footnote103 The number of references in the annals to the burning of forts in Scotland is notable given that it is obvious that our sources contain only a partial record. As Kathleen Hughes has noted, secular and ecclesiastical siege and burning events (including those for Ireland) before ad 800 tend to cluster in particular periods: ad c 615–45, 671–714, 731–57, 775–790.Footnote104 Therefore, the inclusion of such items is unlikely to reflect the actual frequency of destruction events at major forts, rather the varying practices of chroniclers and copyists. There is also a limited geographical coverage; not a single Pictish fort has been identified north of Dunnottar (Aberdeenshire), which is south of the Mounth. This may reflect problems in identifying northern Pictish sites, due to a combination of place-name change, reduced later use of such forts, and lower survival of texts concerned with this region. Nonetheless, even with the minimum numbers recorded in the sources, six burnings over the period ad 685 to 780 averages one every 16 years, suggesting that major destructive events of this nature occurred more than once per generation. Including all the direct references to sieges, successful occupations, and destruction over the period ad c 640 to 780 produces an average of one recorded episode of conflict involving elite sites in the annals every nine years, but given the record’s partial character, such events presumably took place much more frequently.Footnote105

Overall, historical sources and direct archaeological evidence from sites such as Clatchard Craig, combine to foreground destruction by fire as a recurring act bringing to an end particular phases of fort building in early-medieval northern Britain. What is particularly notable about the Clatchard Craig evidence is just how short the entire lifespan of the monumentally enclosed phase of the site was, and the lack of evidence for re-occupation after the destruction of the ramparts. While burning is recorded through the documentary sources at sites such as Dunollie, and through the archaeological record, episodes of burning did not curtail the long-term significance of these places. Dunollie, for example, has radiocarbon dates that extend throughout the later 1st millennium ad and into the 2nd millennium suggesting that the fort(s) there had numerous phases ().Footnote106 Clatchard Craig in contrast has no evidence of occupation and no radiocarbon dates that extend beyond the 7th century ad. After the catastrophic destruction of the later 7th century it appears to have been abandoned and forgotten until the modern period.

An Endgame for a Major Early-Medieval Fort

In terms of the destruction of Clatchard Craig, we do not have any references that can be linked directly with the undocumented site, but the probable end date of cal ad 640–685 (95% probability)/cal ad 650–670 (68% probability) (; end: Clatchard Craig) does coincide with a period of Northumbrian dominance over southern Pictland and the subsequent Pictish overthrow of this rule in ad 685 at the Battle of Nechtanesmere.Footnote107 This was one of the most notable historical events of the 7th century in northern Britain. The destruction of the site could have occurred during events leading to the battle, or its immediate aftermath. However, the powerbase of Bridei, son of Beli, appears to have lain in the north — he is the first king explicitly called rex Fortrenn ‘King of Fortriu’ in the Irish chronicles.Footnote108 Fortriu (a polity centred around the southern shores of the Moray Firth) became the overkingship of Pictland in the 7th century and Bridei’s victory and ascent to overking may have required the brutal extinguishing of both Anglian foes and internal rivals. Bridei is said to have destroyed Orkney in ad 681,Footnote109 and he may have also been responsible for attacks on Dunnottar (Aberdeenshire) in ad 680, and Dundurn (Perthshire), in ad 682.Footnote110 The destruction of southern centres of power such as Clatchard Craig may have gone hand-in-hand with the lead up to Bridei’s famous victory at Nechtansmere, with perhaps a rival or even an Anglian-endorsed ruler at Clatchard Craig ousted by Bridei as part of, or following on from, the dramatic expulsion of Anglian overlordship from southern Pictland that occurred on 20th May ad 685.Footnote111

However, the Battle of Nechtansmere lies within the margins of the calculated end date for the site (ad 610–685; 95% probability), but outwith the range that comprises the highest single-year probabilities for the end of occupation ‘event’ (cal ad 650–670; 68% probability). Bede in his ‘Ecclesiastical History’ of ad 731 stated that during the reign of King Osuiu (642–70), probably from the 650 s–660s, most of the Picts, in the south at least, came under the control of the Northumbrians.Footnote112 This control seems to have been re-established and extended in the 670 s following a period of Pictish rebellion, since Stephen’s ‘Life of Wilfrid’, written in the 710 s, stated that a Pictish uprising was crushed in battle in the early years of the reign of Ecgfrith, king of the Northumbrians (670–85).Footnote113 This has been plausibly connected to the deposition of the Pictish king Drest son of Donuel in 671.Footnote114 While Stephen’s statement that the defeat of the Picts early in Ecgfrith’s reign reduced them to slavery is likely to have been an exaggeration, his claim that this (and a defeat of Mercia) increased Ecgfrith’s territory and Wilfrid’s ecclesiastical jurisdiction as Bishop of York to include the Picts is not implausible.Footnote115 Moreover, Bede stated that as a result of Nechtanesmere, the Picts regained terra possessionis suae quam tenuerunt Angli, ‘the land of their settlement which the Angles held’, whereas the Britons and Gaels simply regained their freedom.Footnote116 Bede also wrote that after the battle the English in Pictland were either slain, enslaved or they fled, the Northumbrian bishop over the Picts, Trumwine, doing the latter. While this may be exaggerated, it is plausible (and comparable with the Northumbrian expansion into British lands) that by 685 English people had been granted Pictish lands and were active inside Pictland politically and ecclesiastically.Footnote117

Given the peak in the probability for the end date for Clatchard Craig is ad 650–670, it is tempting to connect the end of the site with conflict between the Picts and the Northumbrians before the reign of Ecgfrith. However, even during this period, conflict between local potentates could have occurred, as is indicated by the Battle of Srath Ethairt (Strathyre in upland Stirling Council) in c 654/5 between the Pictish king Talorcen son of Ainfrith and Dúnchad son of Conaing (probably of the Cenél nGabráin dynasty of Argyll).Footnote118 A battle in Fortriu also took place in 664, and in 676 an item records that many Picts were drowned during a probable period of conflict at the unidentified Land Abae.Footnote119 Bernician hegemony before Ecgfrith may initially have involved the taking of tribute and expressions of subordination from local Pictish rulers with limited direct interventions in Pictish territory.Footnote120 Nevertheless, Northumbrian domination must have been underpinned by military power, and as the foremost power in southern Pictland from at least the 660 s onwards, the Northumbrians are the prime candidates for the destruction of Clatchard Craig, with its related lands and rights presumably redistributed to create a network of loyal supporters in the area. Unfortunately, we cannot narrow the destructive event down further chronologically or historically, and much remains speculation, but it is notable that like Dunollie, a major burning event at an early-medieval fort occurred during a tumultuous time in this region, when the area was subject to varying competing overlords.

CONCLUSIONS

Clatchard Craig is one of the most complex defended centres of early-medieval northern Britain hitherto identified. Yet it is a defended centre that appears to have reached a violent demise within a few generations of construction, perhaps caught up in some of the most pivotal events of 7th-century northern Britain. The site can be plausibly connected to the activities and expressions of status and power of the southern Pictish kings, with Bayesian modelling allowing the plausible connection of site construction to the reigns of individual kings and documented periods of unrest in our (albeit limited) historical sources. The destruction of Clatchard Craig may have been bound up in the events that at first led to the removal of Pictish rule of parts of southern Pictland and then its spectacular re-establishment prior to and after the Battle of Nechtanesmere. The rescue excavations conducted by Roy Ritchie and Richard Hope-Simpson and the write-up of their work by Joanna Close-Brook provided a valuable resource for understanding the site and the archival resources to re-evaluate the sequence with benefit of the much more precise dating methods at disposal today. Even though the site of Clatchard Craig tragically no longer exists, this project demonstrates the value of excavating in the archives and more detailed forms of radiocarbon modelling for improving the chronologies of the early-medieval period. In northern Britain these new chronologies are essential for understanding the dynamics of early-medieval rulership and the biographies of fortified centres that form such a prominent part of our surviving historical sources for this region.

| Abbreviations | ||

| AT | = | Annals of Tigernach, ed Stokes |

| AU | = | Annals of Ulster, ed Mac Niocaill and Mac Airt |

| CS | = | Chronicum Scotorum, ed Hennessy |

| NRHE | = | National Record of the Historic Environment (Scotland) |

Acknowledgements

This article is dedicated to the work of Roy Ritchie, Richard Hope-Simpson and Joanna Close-Brooks who rescued important information and material in less-than-ideal circumstances through which this re-interpretation of the sequence at Clatchard Craig has been made possible. Thanks to the colleagues who gave advice and support for the re-dating programme: Edouard Masson-Maclean identified the animal bone samples to species and Zena Timmons and Jerry Herman from the Natural Sciences Department, National Museums Scotland, arranged access for sampling. Derek Hamilton undertook the sampling at SUERC. Stratford Halliday and Joanna Close-Brooks read through early drafts of the article and provided many insightful and useful comments. The writing of this article, the radiocarbon dating and additional costs was supported by a Leverhulme Trust Research Leadership Award (RL-2016-069).

Notes

5 Close-Brooks Citation1986.

6 Alcock Citation2003, 179; Fraser Citation2009, 358–60, 366; Noble et al Citation2013; Foster Citation2014, 44–61; Noble et al Citation2019, 57–9. Driscoll (Citation1998) suggests a move towards lowland, less defended sites in the late first millennium ad.

7 Eg Bannerman Citation1974, 15–16; Alcock Citation2003, 179–200; Woolf Citation2007; Fraser Citation2009; Evans Citation2014; Noble and Evans Citation2019, 39–57.

8 Mac Airt and Mac Niocaill Citation1983, 130, 154, 176, 234, 326 (AU 658.2, 694.6, 722.3, 780.1, 870.6); Stokes Citation1896, 253 (AT [752].2; annals either given as ‘kl’ plus annal number or with corrected ad dates in square brackets using Evans Citation2010: 236–43); Alcock and Alcock Citation1990, 98; Adomnán, ‘Life of St Columba’, I.15), in Sharpe Citation1995, 123.

9 Lowland complexes may have been a feature too, certainly by the end of the 1st millennium ad: Driscoll Citation1998, 169–70. The enclosure complex at Rhynie was enclosed by ditches, banks and a palisade, but does not sit in a hilltop location (Noble et al Citation2019). In contemporary occupation however, and located overlooking the Rhynie complex, was Tap O’Noth fort, a 16-ha hilltop enclosure suggesting some complexity to earlier elite centres of the Picts.

10 Adomnán, Life of St Columba, II 33, 35, in Sharpe Citation1995, 181–2, 184. See Alcock et al Citation1989, 192; Woolf Citation2007, 105 for further discussion of hillforts and elites.

11 See summaries and comments in Alcock Citation2003, 179–99; Ralston Citation2004; Carver Citation2011, 1479–83; Noble et al Citation2013, 1140. For the pioneering work of Alcock see Alcock Citation1976; Citation1981; Citation1988; Citation2003; Alcock and Alcock Citation1987; Citation1990; Alcock et al Citation1989). Alcock’s campaign of excavations in Scotland began in 1974 and took place over a decade.

12 Ritchie Citation1954; Close-Brooks Citation1986.

13 Table 19 in Campbell Citation2007.

14 Close-Brooks Citation1986, 175.

15 NRHE 30074; NO 2435 1780.

16 Woolf Citation2007, 9–13.

17 Close-Brooks Citation1986, 118.

18 The Newburgh to Collessie route is the route of the main Edinburgh to Perth trainline today and the route to Cupar is marked on William Roy’s map of 1747–55 https://maps.nls.uk/roy/index.html [date accessed]

19 Ibid, 119.

20 Ibid, 119–20 for full discussion of the site history and details cited above. Although Close-Brooks gives the date of 1980 for its complete destruction, Robert Dickson (OS Archaeology Division) visited on 20th May 1970 and recorded ‘The fort has been completely destroyed by quarrying’ (Strat Halliday pers comm). We can thus bracket the actual destruction of the fort to roughly 1950–70.

21 Max 120 m OD.

22 Nineteenth and 20th century sources place the entrances to the ramparts in the south-eastern quadrant. These were not evident by the time of the excavations, with the exception of a possible entrance through Rampart 4 in this area (Close-Brooks Citation1986, 122). A 1933 plan of the site placed the entrance to Rampart 2 in a gully where Hope-Simpson excavated Trench H, but Hope-Simpson found that the rampart continued across the putative entranceway (Close-Brooks Citation1986, 139). The presence of entrance 4 where there is no corresponding entrance in Rampart 3 could indicate Rampart 3 was later than Rampart 4, but this is very uncertain given the lack of investigation in this area. See below for discussion of the dating of the outer ramparts.

23 Close-Brooks Citation1986, 122.

24 The forts are Black Cairn, a large oval univallate fort around 0.9 ha; Braeside Mains, another univallate fort around 0.55 ha in extent; Glenduckie, a bivallate fort enclosing an area of 0.46 ha; Green Craig, an irregular bivallate fort around 1.1 ha and Norman’s Law (All Fife). See Lock and Ralston Citation2017: SC3124, SC3123, SC3122, SC3144 and SC3143. To the west, the SERF project, led by the University of Glasgow, investigated around a dozen forts along the northern face of the Ochils near Forteviot, Perthshire. None were shown to have early medieval phases apart from a 10th–11th century phase at Castle Craig (NMRS 26048).

25 Norman’s Law was identified by Feachem (Citation1963, 125; 1966, 82) and by later scholars (eg Hanson and Maxwell Citation1983) as a classic nuclear fort, a site type often thought to date to the early medieval period, but no excavations have ever been conducted at the site.

26 NRHE 30073.

27 Watson Citation1929, 149–51; Stevenson Citation1952, 111; Close-Brooks Citation1986, 179. Although unclassified in Bourke ( Citation2020, 364, n413), the bell is of early medieval form with stylistic parallels to Anglo-Saxon hand bells (Bourke pers comm).

28 NRHE 30065. This would have been a very impressive monument, taller than the Dupplin Cross, Forteviot, but now much degraded. On the eastern side, the decorative scheme is broken into four panels with hounds and deer, two horse riders carrying spears, and single riders in the top two panels. The western side appears to have been the cross-side, but is particularly eroded (See Proudfoot Citation1997, 54–5, 62).

29 Allen and Anderson Citation1903, 311–13, 367; Proudfoot Citation1997, 62.

30 Dating based on Noble et al Citation2019, 1341–2.

31 NRHE 30019; Allen and Anderson Citation1903, 343–4. The two symbols on the front of the stone are superimposed on an earlier and unusual rectangular symbol. Dating based on typology in Noble et al Citation2019, 1341–2.

32 Close-Brooks Citation1986.

33 Likely to be of pre-Roman Iron Age form: Close-Brooks Citation1986, 147.

34 Ibid, 139; Carpow Legionary Fortress, Late 2nd to early 3rd century AD: NRHE 30081; NO 20711 17898. Reused Roman masonry in the form of sandstone slabs with mortar attached was also found at Dundurn, Perthshire, probably taken from nearby Roman forts of Strageath or Dalginross (Alcock et al Citation1989, 203). Dundurn appears to have been occupied throughout the 7th century AD.

35 Ibid, 143–5.

36 Campbell Citation1986, 155; 2007, tab 19.

37 Close-Brooks Citation1986, 162, illus 23 and 24.

38 Wilson Citation1973.

39 Ibid, 147–8.

40 Stevenson Citation1974, 36–8, tab III.

41 Close-Brooks Citation1986, 147.

42 Ibid, 143–5.

43 Ibid, 130.

44 Though see comments by Close-Brooks Citation1986, 134.

45 Ibid, 144.

46 Close-Brooks Citation1986, 164; Stevenson Citation1974, 36–7, tab III.

47 Ibid, 149.

48 See Ashmore Citation1999 (and in the case of GU-1797 the use of mixed charcoals).

49 https://www.abdn.ac.uk/geosciences/departments/archaeology/Comparative_Kingship.php [Accessed 1 Sept 2022].

50 The other hillforts are: Urquhart Castle (probable based on Alcock’s excavations: Alcock and Alcock Citation1992); Tap o’Noth (University of Aberdeen excavations); King’s Seat (See http://pkht.org.uk/projects/current-projects/kings-seat/ [Accessed 1 Sept 2022] including downloadable DSR reports); Dundurn (Alcock et al Citation1989); East Lomond (Excavations on a terrace below the fort suggests late Roman Iron-Age to early-medieval occupation of the hill, though the defences remain unexcavated: https://www.centreforstewardship.org.uk/archaeology/ [Accessed 1 Sept 2022]); and Abbey Craig (Recent excavations — Murray Cook pers comm). See Ralston Citation2004; Noble and Evans Citation2019, ch 3 for general overview of Pictish forts; Noble et al Citation2013, full article and online supplement for the most recent list of relevant dates (although somewhat superceded by recent investigations).

51 Zena Timmons and Jerry Herman from the Natural Sciences department at National Museums Scotland facilitated access with Derek Hamilton of SUERC obtaining the samples using a Dremmel drill to take small core samples from each bone.

52 Ashmore Citation1999.

53 See Barnetson Citation1986, C6–C14.

54 Eg SUERC-82047 and SUERC-87107, Table 1.

55 Eg Rampart 1: animal bone from Level 7 is earlier than animal bone from Level 6 of the rampart (SUERC-82048) and this in turn earlier than a date from above the core of the rampart (SUERC-82046). Rampart 2 includes animal bone from below rampart (SUERC-82055) that is earlier than bone from the core of the same rampart (SUERC-82053) and in turn earlier than animal bone from above core of rampart (SUERC-82052) (Tab 1). Given that the dating of the bone largely follows the stratigraphic relations and is broadly contemporary with the charcoal dates, the animal bone has been modelled as part of the activity occurring at the time of rampart construction, with the later deposits above the rampart core from use of the site incorporated into dumps on top of the rampart.

56 This is important as the charcoal samples include some highly likely to have been used in the timber-lacing of the ramparts (Eg GU-1794; GU-1795; GU-1796). Timber lacing could be from timbers reused from other contexts as was found at Green Castle, Portknockie, Moray (Ralston Citation1980, Citation1987), but in the case of Clatchard Craig the stratigraphic sequences and relative dating suggests reuse of wood is not a factor to consider in detail. The only potential example is GU-1794, which was excluded from the model due to a possible old wood effect. In this case it is possible it was a reused timber from an earlier building either at Clatchard Craig or from a site in the wider landscape, but none of the other charcoal dates are appreciably older than any of the other samples. As well as probable structural timber, the oak roundwood and alder charcoal from Rampart 3 provide non-structural timber samples for dating. In these cases, the charred wood is again not appreciably different in date from the majority of the other samples dated including animal bone and the other charcoal dates. It would be very unlikely that all these materials would be residual or reused in the rampart, but appear to be more likely to have been contemporary materials used in construction.

57 (SUERC-82048; 1452 ± 26 BP).

58 Dunbar et al Citation2016.

59 Stuiver and Polach Citation1977.

60 Stuiver and Kra Citation1986.

61 Stuiver and Reimer Citation1986.

62 All non-high precision calibrated dates rounded to ten years; modelled ages to five years.

63 Stuiver and Reimer Citation1993.

64 Reimer et al Citation2020.

65 Bronk Ramsey Citation2009.

66 Buck et al Citation1996.

67 Amodel = 162.

68 The latter two samples seem most likely to come from activity associated with the construction of the fort.

69 The only obviously residual date from a rampart context is SUERC-82047, an Iron Age determination from Rampart 1 where occupation activity was concentrated.

70 See discussion in Close-Brooks Citation1986, 133–7.

71 As noted above, there is an entrance in Rampart 4 that does not contrast with an obvious entrance in Rampart 3 that could suggest that Rampart 3 was later than Rampart 4. However, given the lack of clear evidence for the entrances for ramparts 1–3 not much weight can be given to this observation.

72 Contra Close-Brooks Citation1986, 136. The phasing and contemporaneity of the multiple enclosures of multivallate early medieval forts, the so-called ‘nuclear type’ has been debated since Stevenson (Citation1949; See also Feachem Citation1955; Alcock et al Citation1989, 206–13). The evidence from Dunadd suggested that the multiple enclosure form developed through a lengthy gestation period (Lane and Campbell Citation2000, 92–5), but work at other forts such as Mither Tap o’ Bennachie, Aberdeenshire, suggest a more rapid development or indeed unitary programme of construction. Feachem (Citation1966, 84) included Clatchard Craig in his defensive enclosure type, a group that replaced his earlier nuclear and citadel fort types. Multiple ramparts are common at early medieval forts — eg Burghead, Moray; Dundurn, Perthshire; Trusty’s Hill, Dumfries and Galloway; Dunadd, Argyll. As noted above, Clatchard Craig is the most complex yet identified.

73 The only later dates are the charcoal sample (GU-1795) from Rampart 1 that has a wide error margin (±75) and SUERC-82046 that comes from a layer above the core of Rampart 1 — the latter could conceivably be redeposited over the rampart following stone robbing and post-depositional disturbance of the fort interior.

74 Wilson Citation1973, Plate 31, 33c. The hoard had been dated to around 800 ad but there is no direct dating: Wilson Citation1973, 147–8.

75 Likely to date to the second half of the 9th century: Stevenson Citation1985, 236.

76 The differences are clearly seen in the illustration on pg 191 of Clarke et al Citation2012 or Youngs Citation1989, 115.